20 minute read

Route 66

FLYING ADVENTURE

Leonardo Correa Luna takes his Cessna 170 on a trip back in time – and finds his kicks on Route 66…

Advertisement

If you wanted to prove that ‘the good old days’ were better, then there is no better time for that than 2020! After being notified by my airline that I would get an ‘extended leave’, courtesy of Covid-19, I decided that I had had enough of 2020 and needed my time machine to travel back and find a better time… A quick online search, a ticket to San Francisco, an Uber ride to Livermore airport (KLVK), and there I was opening the hangar doors of my particular time machine – my 1952 Cessna 170B.

I had this urge to disconnect, fly without too much of a plan, just barnstorm some of the country following the winds and discovering new places. There was just one definite plan, to visit friends in Minnesota, and as a part of the trip I wanted to follow an incredible piece of Americana, and a link to the past, Route 66.

Why are people from all over the world attracted to an old two-lane route with no fancy resorts, no big attractions, just an old road that goes through small towns, the countryside, and the desert from Chicago to L.A.? For most, it is the chance to travel back in time to a period of history when life was simpler, a time before America became a ‘franchise’. Following Route 66 is a way to return to the way America and the world used to be, and the Cessna would be a perfect way to admire it in it’s full splendour.

Dirt tracks…

In the early 1920s, the USA was connected by a collection of disorganised and roads of poor quality – usually, just a dirt path that was good enough for horses or wagons.

With the increasing popularity of the car, the need to create a new road system became evident. Under the pressure of the public, as well as businessmen like Cyrus Avery (doubted the Father of Route 66), the first road legislation was created in 1916, and in 1925 the Federal Highway System Act was passed by Congress. The numerical designation 66 was assigned to the Chicago to Los Angeles route in the summer of 1926. From the outset, the planners designed U.S. 66 connecting the main streets of rural and urban communities. Until that point, most small towns didn’t have prior access to the main national roads. In this way, travellers connected with the small-town people of America across eight states, three time zones, and three-quarters of the country.

By 1930 almost the entire highway got paved just in time for the great depression. Over 200,000 people migrated, escaping the Dust Bowl and bank foreclosures to head for California – travelling 2,400 miles taking their families and all their belongings in old Ford Model Ts. For them, Route 66 was a road of hope, famously noted in the The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck. In the novel, Steinbeck baptised Route 66 as ‘The Mother Road’.

During WWII, the West was designated as an ideal training area, isolated and with dry weather during most of the year. Several training airfields were created along the 66, and some of them remain operational. After the war, many of the soldiers that trained in the West decided to abandon colder states and head to the California sun. These were good times, Americans were hitting the roads for pleasure and finally enjoying them. Route 66 was again helping with a new kind of migration, this time a happy one. One of them, Marine Captain, songwriter Bobby Troup, hit the road in the direction of Hollywood inspiring the lyrics of the famous song, (Get Your Kicks on) Route 66. One week later, after his arrival to LA, his song was a hit on the radio recorded by Nat King Cole.

There is little escape from the modern Interstate system

Holbrook’s more modern building notes its Route 66 heritage

Grants Airport is home of the Western New Mexico Aviation Heritage Museum dedicated to the U.S. Postal Service pilots, spot some of the giant arrows and beacons used to guide mail aviators across the country

Old FBO building at Holbrook airport

Mexico’s beautiful Mesa Buttes, made famous in Disney’s Cars movie

From the early beginning, store owners along the route recognised the need for fuel, food, and a place to sleep. Restaurants and motels started to pop up all along the road with bright neon signs trying toattract clients. One of the advantages of the 66 over modern highways lies in it being a two-lane route all at street level. See something that catches your eye as you drive, then just turn off the road, which is a stark contrast to the modern US freeway highway system where you are trapped inside until you hit the next exit, giving a certain irony to the ‘free’ part of the name…

However, 1956 was the beginning of the end for U.S. 66. President Eisenhower signed the Federal Aid Highway Act to create a 40,000 mile-long interstate highway system making routes like the 66 obsolete. During 1977, the last sign of U.S. 66 was taken down, and on 26 June, 1979, the designation Route 66 was officially eliminated. Interstate I-40 took over 66 from Oklahoma City through Texas, New Mexico, northern Arizona to Barstow, California.

Ghosts towns

Like many petrol heads, I’m a fan of American cars from the 1940s-1960s, and often thought I would drive Route 66, but I never thought about flying it. That was until I saw some amazing photos from my friend Dustin Mosher of a fly-in he organised in Amboy, California, one of the old abandoned towns on Route 66. Dustin is a bit of an aviation ‘Indiana Jones’ character in the Mojave area. Officially an engineer at Virgin Galactic, he spends most of his free time flying around the Mojave Desert in his Cessna 120 or Boeing Stearman in search of abandoned runways and ghost towns.

Amboy was once a thriving little town, in existence since the late 1800s, which by the late1940s, had three petrol stations, two cafés, a motel, a school, and a runway! It then became a ghost town as just one more casualty of the interstate system… until recently when a fellow called Albert Okura bought the town and started to restore it to its former glory. Phase one, was to tackle Roy’s Café, and its huge, famous neon sign.

Dustin and a friend had previously landed in Amboy and took the opportunity to taxi beyond the fence to get a photo with the colossal 50ft high neon sign. Surprised by the appearance of aircraft, the manager, Manny, came out for a chat and an idea struck. “What if we brought a whole bunch of aircraft here?” The Great Amboy Fly-In was born, with the first one held in January 2019, when more than 30 aircraft showed up for the two-day event. At that time, the Okura family was working hard, and the iconic sign was close to completion, so what better way to celebrate than with another fly-in! The Great Amboy Fly-In, Part II (still 2019) was born. Another success, with visiting aircraft coming in from across the country, and that night after decades of sitting in disrepair, the neon sign was switched back on!

For that reason, The Roy’s Café neon sign became the beacon for my trip. California was on fire, and temperatures in the desert were over 100°.

Between the smoke and the heat, I decided it would be a much better idea to hit the 66 on my return flight to California after spending a few weeks in Minnesota. My navigation wasn’t going to include the entirety of Route 66. First, I needed to visit some Colorado friends. KFLY, Springfield, Colorado, home of the Air Force Academy, became my departure point heading south to intercept U.S. 66.

Above Welcome to Arizona! Winslow Airport, to the right the ‘Iron Road’ and bottom right corner, what was originally Route 66

Grand Cavern Canyons. Taxi in from the left to the end of the taxiway with one lone hangar

Spitfire! Unfortunately, not the kind that flies

The gravel runway could use some TLC

Good morning U.S. 66!

Plenty of visitor info…

Your first challenge, whichever you choose to follow the 66, is to find it. Nearly all of the route still exists, but is not entirely on the maps. Your primary reference is the new highway system, starting with I-55 in Chicago, then I-44, I-40, I-15, and I-10 to Santa Monica. But the interstate system only connects main cities in the shortest possible way, sometimes following the old Route 66 closely, sometimes not. One of the tricks to finding the 66 is to follow the old iron road along the interstate system and the airports built before 1956!

La Veta Pass

I departed early in the morning from KFLY, heading south to intercept I-40, and then headed off to find the 66. I then crossed the mountains through La Veta Pass (07V if you’re keeping notes) and soon left Colorado – and said ‘hello’ to New Mexico! A quick stop for fuel in Taos (KSKX), and I was minutes away from finally reaching Route 66. Leaving Albuquerque, soon I was following I-40. Sometimes it’s easy to figure what should be the 66, sometimes not. In certain areas, the historic 66 is on the maps. In others, you can only make your best guess. If it’s close to the railroad and connecting small towns, you have a high chance that it is the 66. As I overflew, I couldn’t help remembering the line in the song, ‘You’ll see Amarillo, Gallup, New Mexico, Flagstaff, Arizona…’

Needing fuel, Holbrook Municipal was ahead and was a perfect choice as Route 66 had passed through town since 1926, and luckily the town wasn’t bypassed by I-40. Still a vibrant city with 5,000 inhabitants and home of one of the two remaining Wigwam Motels on the 66. With rooms shaped to resemble American Indian teepees, these motels were the inspiration for The Cozy Cone Motel from the Disney movie Cars, a great overnight stop if you are traveling with kids, I only wish my daughter Jade had been with me.

There is not much at the airport, some hangars, a new fuel pump, and a pilots’ lounge. The old FBO wooden building remains, but it’s closed and looks abandoned. Tanks full, legs stretched, it was time to hit the road again. I wanted to reach Amboy before sunset, but mother nature had other plans. As usually happens in the desert, things started to warm up and get bumpy, and some annoying non-stop turbulence began. I passed another ‘song’ city, Flagstaff. The current airport was built in 1948 and is a modern airport, Class D airspace with airline operations, which was not what I was looking for, so I stayed outside the D while my seatbelt did its best to keep me in the seat. Eventually, I decided I’d had enough turbulence for a day. This was meant to be fun after all. Remembering a tip from Dustin to visit Grand Canyon Caverns, a few taps on my iPad and Foreflight pointed me in the right direction to L37.

It was easy to spot the 5,100ft gravel runway as L37 is in the middle of nowhere. The windsock looked like it had been there since the 1960s and was no longer operational. A low pass to check for cattle and wind direction and I decided to try Runway 05. The runway was in good condition except for some high weeds, I rolled out and taxied carefully to the end. Reaching the taxiway the sign welcoming pilots asks you to check-in at the motel front desk. Things were getting interesting! A lonely T hangar with no doors looks like potential shelter, but as I looked I decided it had seen better times. Wishing to have a good night of sleep without nightmares of the hangar collapsing on my 170, I tied down outside on a small apron area.

Walking around looking for the motel front desk, I first found a petrol station that looked like it was another Cars movie set. A closer look found a treasure trove of classic cars with all kinds of car-related memorabilia, and some giant dinosaurs… yes, I was in Route 66 heaven! Finally, finding the front desk I asked about a room. The receptionist asked me about my car registration, replying that I flew in and parked out the back, made her look at me as if I was messing with her. Just as I began with, “No, I really did fly in…”, her colleague began to laugh and said, “You didn’t know that we have a runway?” Turned out it was her first day at the job!

The motel was lovely, nothing fancy, but clean and well preserved. I later learned it used to be possible to taxi and park outside your room in the past and that it wasn’t unusual for Hollywood stars to hide out here with their lovers. It was easy to imagine how a polished Beech 18 might have rattled to a stop, the door opening to reveal a big name…

Besides the motel, there’s a souvenir shop, restaurant and of course the Caverns! The restaurant is uphill, about a mile from the motel. I hitched a ride, and arriving at the restaurant, which is also where the Caverns tour starts, I was told that the kitchen would close soon and that the Caverns’ last tour was beginning. Tough choice, eat and drink a beer or visit the Caverns? I was starving, so the burger won!

The Caverns were discovered by accident in 1927 by a young man called Walter Peck. Initially, thinking there might be gold in them he invested all his savings to buy the property. When it turned out there was no gold, he did the next best thing and created the Cavern tours, attracting the passing drivers in true Route 66 style! The current owners are also following the trend of bringing back Route 66 to better times, and they told me that pilots are more than welcome!

My suggestion to get a radio to monitor the frequency, trim the weeds and a couple of courtesy cars were taken on board. Who knows, maybe next time I’ll be able to taxi to my room…

I slept like a baby, waking up early to depart before the temperature began to climb. Having all day to reach Amboy, being just a couple of hours away, allowed me to do some extra exploring. It was easy to decide on the next destination – Kingman!

The most basic of hangars, but keeps the searing sun at bay…

Kingman Army Air Field (KAAF) was built next to Route 66 in 1942. An aerial gunnery training base, primary gunners for the B-17, Flying Fortress. After training 35,000 gunners and with the war over, it was declared surplus on 15 November, 1945. But that started what is probably the most interesting period of its history. With its vast open fields, dry weather, and long runways, Kingman became Storage Depot No. 41 for some of the 150,000 surplus aircraft left from the war. Soon 150 machines per day were landing and being stored in Kingman, with an estimated 5,400 in total between 1945 and 1946.

The Wunderlich Contracting Company reduced those 5,400 aircraft to aluminium ingots, including hundreds with just delivery hours on them. Fuel was drained and sold (usually for more than what was paid for the aircraft), engines and accessories removed, and what was left then sliced and melted. The contract was completed in July of 1948, when Kingman became a municipal airport.

No escape from reality

While I knew of Kingman’s WWII history, what I didn’t realise is that part of its history was repeating itself. When I was approaching the airport, I could see the shapes of hundreds of airliners parked around and in between the runways. For a moment, I was amazed by the number of airliners parked one next to the other, but at the same time, it was a reminder of the reality I was trying to escape from.

While the photographer in me wanted to take some photos, my airline pilot side felt incredibly sad. I decided to land and get breakfast, I wasn’t ready for this.

I parked by the airport café, which was connected to a small museum with memories from the war. The café itself is full of aviation memorabilia, and the food is tasty. After several cups of coffee, I was ready for a walk around the Boneyard.

‘Overwhelming’ was probably the word, hundreds of airliners parked one next to the other, most of the CRJ type, Bombardier and Embraer, with the occasional odd bird, a bare-bones Beech 18 here, a C-119 Flying Boxcar there. Most of the airliners had been placed in storage, but not all were that lucky, with some at the end of the line being scrapped. It was so quiet, it definitely felt like a graveyard. As the shadows grew long, I realised that time was getting away from me and it was time to get going. With just an hour flying to Amboy, I made a few orbits over Kingman documenting the Boneyard. In the end, it is part of the history we are living, even if it is rather sad.

Seat with a view, Airport Café, Kingman

Just two lanes, the original Route 66 snakes across the land

Far left Kingman’s WWII tower is restored to perfection

Kingman Airport, and all its stored airliners really evoked mixed emotions

Memories from the past of the thousands of aircraft that made their final flight here

Below The final destination for many…

Amboy, with its two runways, petrol station, motel, and post office on the opposite side of the road

Departing Kingman you can follow the old 66 as it passes through the town and then merges with I-40 to later disappear from the map and resurface in another section. This happens on and off in different areas now that it’s partially back in the maps as ‘Historic U.S. 66’ and makes it very interesting to compare the old route with the path followed by the new highway. En route, I made a quick detour for cheap fuel to A20 Sun Valley Airport. I’m always amazed at some of these small airports, they look totally dormant, but some local guy will usually show up even before you’ve shut down the engine. This particular guy was Tim, who helped me refuel plus a lift to the shop to get some drinks and good fried chicken for dinner!

With just 40 minutes before I would be landing in Amboy, I felt relaxed. I was flying low, following the 66, which is mostly closed in this area. In 2009 severe seasonal flooding (yes, in the Mojave Desert) damaged more than 40 bridges, including many of the old bridges on the 66. You can see that repairs are almost complete, and that section of the road may reopen soon. For the moment is an excellent section to land if you develop carburettor ice…

Amboy crept slowly into sight, and after a couple of 360s to capture some photos, a low pass down the runway to check its condition was followed by an uneventful landing on the dirt runway. Taxying to the end revealed a lonely hangar and windsock, both surprisingly in decent shape! I continued through the fence and turned left, passing by the petrol station and parked under the neon sign.

As I hopped out I was struck by the moment and just stood there, contemplating the scene as the sun lowered gradually in the sky. It was a perfect 1950s postcard moment, precisely as I imagined it. For a few minutes, my time machine had worked – I wasn’t in 2020 anymore…

After some exploring I found the café and souvenir shop, plus I got a look at the old motel rooms, still very much in original condition awaiting restoration, but surprisingly not a bad one. Besides that, there is not much to see. For many, Amboy is about ‘that’ sign. There is a constant non-stop flow of travellers stopping to take a photo with it, and for a while, my 170 seemed to add to this Route 66 attraction. With the runway out of sight behind the petrol station , plenty of people asked if I had landed on the road. I had some fun for a while, and with a smile, I added, ‘just maybe…’

Once the last of the stream of visitors had headed off into the darkness, I decided it was time to call it a day. One last push of the 170 into a corner next to the petrol station, and then I popped my tent up under the wing. Finding the provisions, I opened a bottle of red wine and enjoyed a perfect fried chicken dinner under the Mojave Desert stars.

Taxi to the end and turn left to the café! Welcome to Amboy!

Roy’s neon sign restored to its former glory

The following morning’s sunrise woke me, and it was a case of packing my tent and making the day’s plans. A yellow Carbon Cub appeared overhead, and a few minutes later was taxying in beside the 170. My friend James, his wife Sarah and their dog Gizmo had found me, so we shared a coffee, before getting airborne.

Following Route 66 in this area makes you happy to have an aeroplane, as there’s just desert… followed by more desert down there. I cannot imagine how it was to cross these areas in a Ford T back in the 1930s, or before that, in a wagon pulled by horses.

Frozen in time

The final airport on my trail was KDAG, BarstowDagget, built in 1933 as an FAA beacon site to help pilots navigate, and it later became a base for A-20s Havocs, and P-38s during WWII. A whole village was built to provide living quarters for the 350 Douglas Aircraft workers and aircrews. Like so much of ‘old America’ out here, those houses still exist, just frozen in time and are just a quick five minute walk from the airport. Another peculiarity of this airport is the tall rustic redwood hangars. If I had to guess, I’d say at least 50ft tall.

Top left you can spot the town that used to be the Douglas workers’ home during WWII

Unusually tall redwood open hangars at Barstow-Daggett Below

Get your kicks on Route 66!

So many airliners of the world in one photo

Need a 737 Max? Available in multiple liveries and registrations…

Knowing there were many new wildfires in Northern California, it’s not surprising the distant horizon of where I was heading was beginning tolook a little smoky. It was time to fill the tanks and re-evaluate the situation. KAPV Apple Valley was just 30 miles ahead and with the promise of cheaper fuel than Barstow-Dagget, was an easy choice. With the tanks full and a new flight plan I was back in the air heading to El Tejon Pass, elevation 4,239ft, before turning to follow I-15 back to Livermore.

Heading west, I decided to take one last look to one of the old airports by the 66. KVCV, home of Southern California Logistics and long-term parking area of most of Southwest 737 MAX fleet and many of the airliners grounded due to Covid-19, including the whole fleet of Qantas A380s.

I could only hope that in the same way that Route 66 is getting a second chance, all these airliners will be back to the air soon. Bidding farewell to the 66, I focused on staying VFR through the smoky skies of Northern California.

Luckily conditions improved and four long hours later, and 86 hours since I had started the trip, I was safely on the ground in Livermore and back to 2020. The journey was over, or was it? Route 66 didn’t disappoint. I got a small taste of huge neon signs, classic cars, motels, larger-thanlife roadside attractions, museums, diners, and colourful characters. Route 66 is still alive and kicking. One day I’ll head back for more…

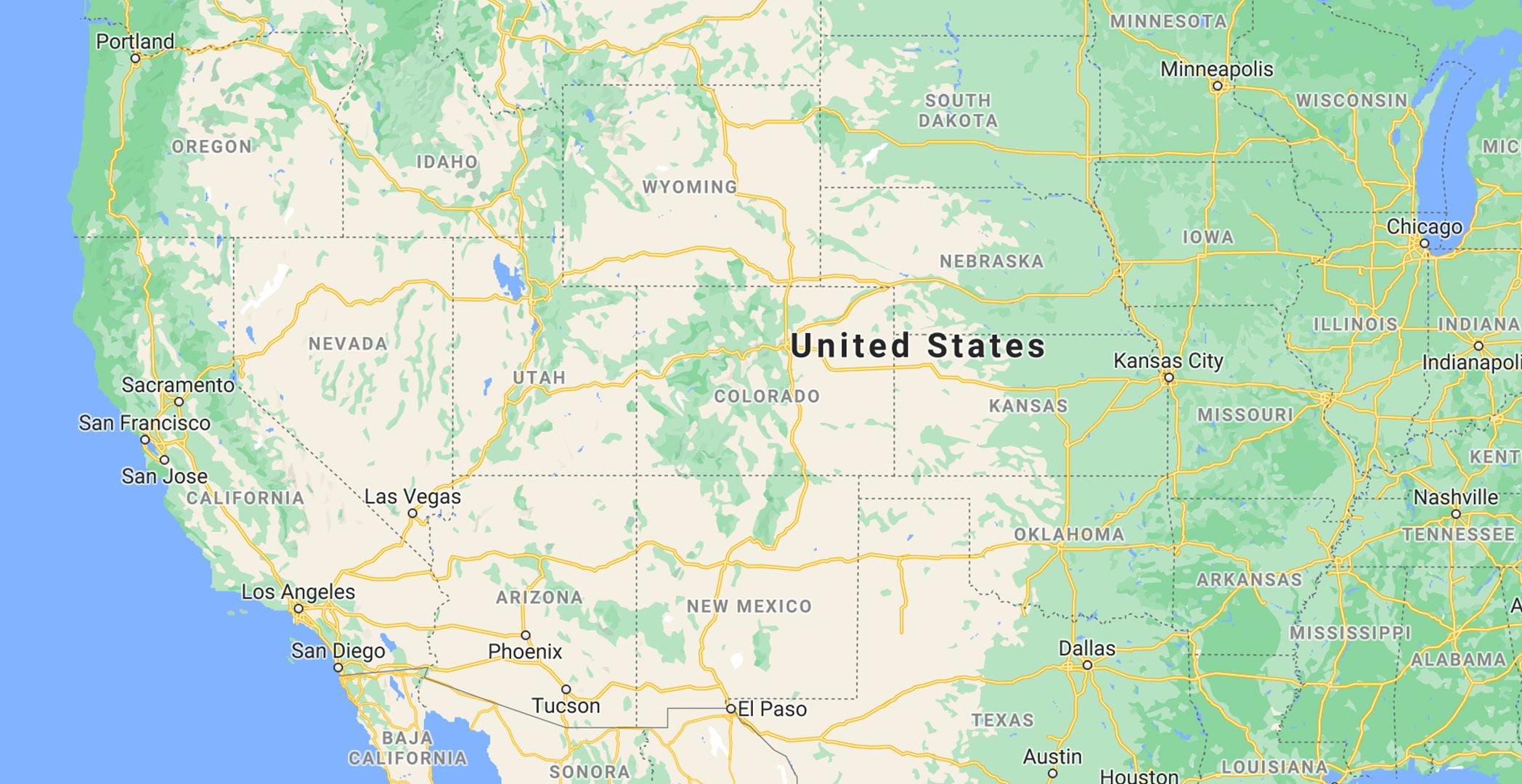

Route Map

1 Springfield 2 Taos 3 Holbrook 4 Grand Canyon 5 Kingman 6 Sun Valley 7 Amboy 8 Barstow-Daggett 9 Victorville 10 Livermore

Just like ‘The Good Old Days’… welcome to the 1950s!