THE HIGH WATER MARK

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE FLOODPLAIN MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATION

The Newsletter of the Floodplain Management Association

Mission: To promote the common interest in reducing flood losses and to encourage the protection and enhancement of natural floodplain values. May 2024 - Volume 34, Issue 2

Chair

Brent Siemer City of Simi Valley 805.583.6805

Vice Chair

Vince Geronimo Geronimo Engineering (916) 993-4606

Treasurer Megan LeRoy California DWR (279) 386-8112

Secretary Millicent Cowley-Crawford Woodard & Curran 415-321-3421

Past Chair

Michael C. Nowlan Wood Rodgers, Inc. 916.326.5277

Director

Abigail Mayrena

Clark County RFCD 702-685-0000

Director John Moynier Parsons Corporation 626-440-2389

Director Brian Brown California DWR

Director Darren Suen

Central Valley Flood Protection Board 916.574.0609

Director Wendy Wang

Central Valley Flood Protection Board 916-501-1482

Director Hilal El Haddad

Riverside County Flood Control and Water Conservation District (951) 955-1265

Director Roger Leventhal Marin County DPW (415) 473-3249

Director David Smith WEST Consultants, Inc. 858.487.9378

Director Kayla Kelly-Slatten KKS Strategies, LLC.

Director Remi Candaele Q3 Consulting rcandaele@q3consulting.net

Director Carly Narlesky MBK Engineers 916-456-4400

Brent Siemer

Grasping the Opportunity, Continued

This letter continues my thoughts on what is the value of an association membership? Last time, I offered 10 ways FMA offers value to career enhancement and growth in our profession. Of those ten, networking has been the most valuable to me over the past 10+ years. I had no experience in floodplain management, when like many of us I was thrown in the deep end and had to learn to swim real quick like. If it were not for the many federal, state and local FMA members who invested their time and expertise in me I would certainly not be where I am now.

What has been your greatest career enhancement and professional growth benefit from FMA membership? If you need to refer back to the last letter, here is the link: https://issuu.com/fmanews/docs/fma_newsletter_ february2024-issuu

The second type of benefit of FMA membership is the increased value to our employer as we grow in our productivity. What does FMA offer?

1. Professional Development: FMA offers affordable access to seminars, workshops, and conferences where Members can enhance their skills and knowledge, ultimately benefiting their work performance and contributing to their organization’s success

2. Networking Opportunities: FMA facilitates connections with professionals in the same industry or field, enabling Members to build relationships, exchange ideas, and potentially find mentors or collaborators who can support their growth and their organization’s objectives.

3. Industry Insights: Through publications and networking, FMA keeps its Members informed about the trends, developments, and best practices within floodplain management, enabling Members to stay ahead of the curve and make informed decisions for their organization.

4. Advocacy and Representation: Associations often advocate for the interests of their members at the governmental, regulatory, and industry levels, ensuring that their concerns are heard and addressed. This advocacy by FMA Members can ultimately benefit an organization’s operations and competitiveness.

5. Access to Resources: Membership in FMA provides access to a wealth of resources which can aid Members in problem-solving, decision-making, and staying updated on relevant information.

6. Professional Recognition: Active participation by their employees in FMA can enhance a company’s visibility and credibility within the profession or industry, leading to opportunities for recognition, awards, and professional certifications, which can reflect positively on the organization’s reputation

7. Recruitment and Talent Development: Employers can leverage association with FMA to attract top talent who value professional development and networking opportunities. Additionally, FMA offers resources through its committee and Board positions to Members for talent development, helping organizations nurture and retain skilled employees.

8. Brand Visibility and Reputation: Affiliation with reputable associations like FMA can enhance an organization’s brand image and credibility in the eyes of clients, partners, and stakeholders. It signals a commitment to excellence, industry standards, and continuous improvement

9. Access to Benchmarking and Best Practices: Associations like FMA provide benchmarks and best practices derived from industry research and Member experiences, enabling organizations to assess their performance, identify areas for improvement, and adopt strategies that have proven successful elsewhere.

10. Voice in Industry Discussions: FMA grants Members and their employers a platform to contribute to industry dialogues, share insights, and shape the direction of their field through participation in committees and the Board, thus influencing industry standards, policies, and innovations.

Membership in the Floodplain Management Association offers great value to our Member’s employers as we grow in our productivity making it a valuable investment for agencies and companies committed to excelling in the field of floodplain management.

Next time, I will end my string of thoughts with the value to the communities that we serve, or that our work products enhance.

I hope that I have inspired you to greater investment in the value of FMA membership.

Brent Siemer

Chairman, Floodplain Management Association

Deputy Public Works Director (Development Services) Department of Public Works City of Simi Valley bsiemer@simivalley.org

Tel: 805.583.6805

California Extreme Precipitation Symposium

July 11, 2024

UC Davis, Davis California

Draft Theme: Anticipating and Planning for California Floods – Past and Future

Floodplain Management Association

Annual Conference

September 3-6, 2024

Westin Lake Las Vegas – Clark County, NV

Visit – www.floodplain.org

For an update of the latest disaster declarations: CLICK HERE

For information on Flood Insurance Reform – Rates and Refunds: CLICK HERE

• Individuals in San Diego County are eligible for federal assistance with damages suffered during flooding between January 21 and 23. Heavy rains resulted in extensive flood damage with numerous homes damaged. FEMA, the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services and other partners have taken a whole community effort to support recovery. San Diego County residents have until April 19, 2024, to apply for FEMA assistance. California was granted a second Presidential Major Disaster Declaration this year for February storm recovery. The counties receiving aid include Butte, Glenn, Los Angeles, Monterey, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Santa Cruz, Sutter and Ventura.

• FEMA received another record-setting request for mitigation funding this year. Nearly $8 billion in applications through the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) and Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) were received before the application period closed in February. A total of $1.8 billion is available this fiscal cycle for these programs. FEMA anticipates releasing later this year an update of the applications received.

• A new tool to implement the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard (FFRMS) helps agencies implement the newer standard. The Federal Flood Standard Support Tool uses both the freeboard value approach (FVA) and climate-informed science approach (CISA) to determine if a federally funded project is in a FFRMS floodplain. The Science and Technology Policy office is accepting comments on the functionality of the support tool by May 28, 2024.

• The updated edition of the National Flood Insurance Program’s Insurance Manual is effective April 1, 2024. The update keeps flood insurance coverage the same as the terms and conditions of the Standard Flood Insurance Policy.

• April 1, 2024, also marked the 45th anniversary of FEMA. The agency continues to evolve and adapt and remains committed to serving people before, during and after disasters.

• FEMA is currently funded, and the National Flood Insurance Program authorized, through September 30, 2024.

• Floodplain Studies

• Hydrology

• Hydraulics

• Flood Forecasting/ Warning

• Dam Safety

• Sediment & Scour

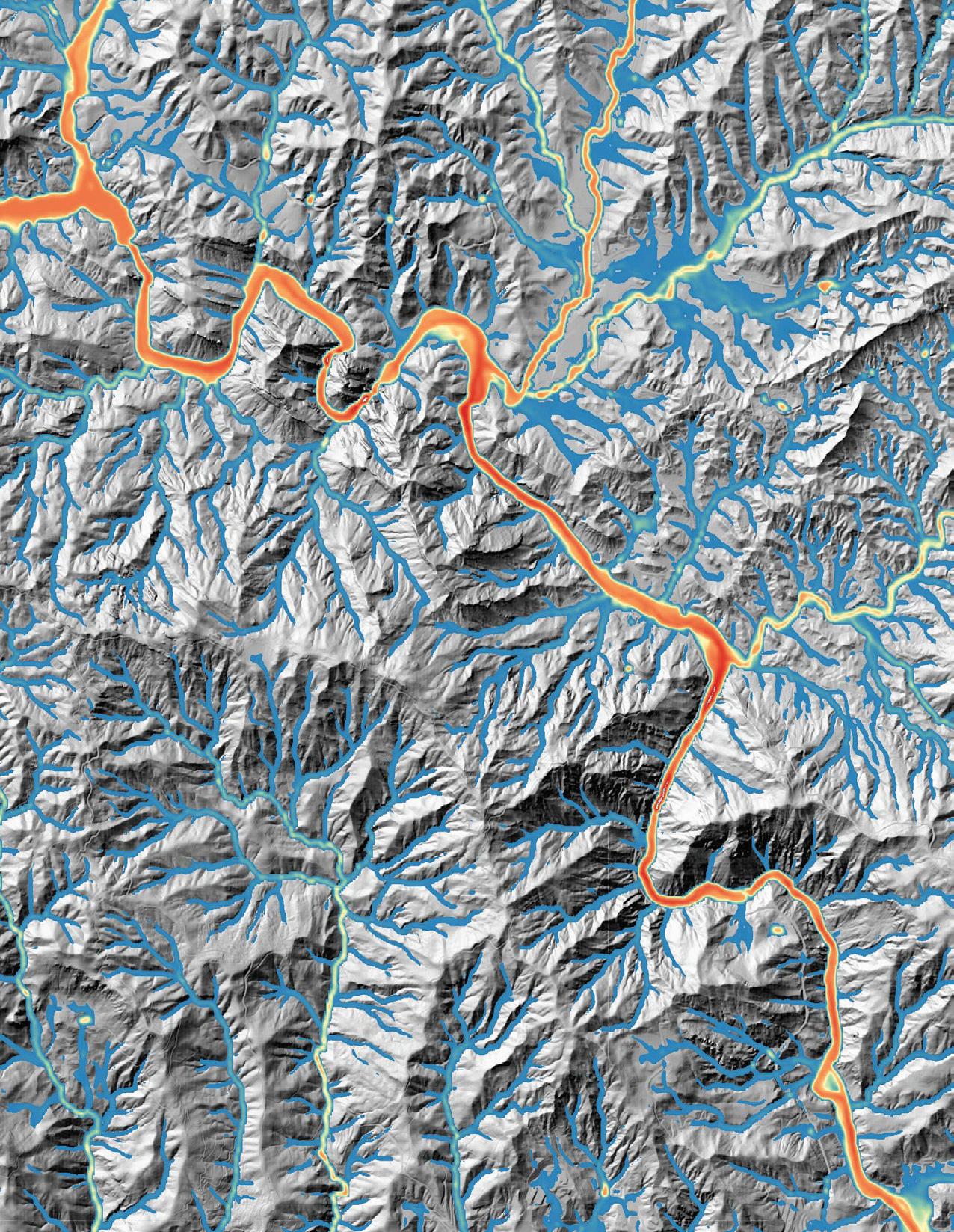

First-of-its-Kind Watershed Study Highlights How Innovative Tools Help Build Climate Resilience in the San Joaquin Valley

April 18, 2024

California’s changing climate brings new challenges each year for water managers as they navigate extreme shifts from drought to flood while working to ensure safe, reliable water supplies for California’s 39 million residents.

More information

California Financing Coordinating Committee

Funding Fair - May 29, 2024

The California Financing Coordinating Committee (CFCC) conducts free funding fairs statewide each year to educate the public and offer potential customers the opportunity to meet with financial representatives from each agency to learn more about their available funding. CFCC members facilitate and expedite the completion of various types of infrastructure projects by helping customers combine the resources of different agencies. Project information is shared between members so additional resources can be identified. Presentations will be held from 9 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. and participants can visit virtual booths from 11:00 a.m. to 12 p.m. to meet with representatives.

More information

Current Conditions

For a current overview of the daily hydrologic, precipitation, reservoir and snowpack conditions in California, visit:

More information

Two in a Row: April Snow Survey Shows Above Average Snowpack for Second Straight Season

The Department of Water Resources (DWR) conducted the all-important April snow survey, the fourth measurement of the season at Phillips Station. The manual survey recorded 64 inches of snow depth and a snow water equivalent of 27.5 inches, which is 113 percent of average for this location. The snow water equivalent measures the amount of water contained in the snowpack and is a key component of DWR’s water supply forecast. The April measurement is critical for water managers as it’s considered the peak snowpack for the season and marks the transition to spring snowmelt into the state’s rivers and reservoirs.

DWR’s electronic readings from 130 stations placed throughout the state indicate that the statewide snowpack’s snow water equivalent is 28.6 inches, or 110 percent of the April 1 average, a significant improvement from just 28 percent of average on January 1.

More information

DWR Releases California Water Plan Update 2023: A Roadmap to Water Management and Infrastructure for a Water Resilient Future

The California Department of Water Resources (DWR) has released the final version of California Water Plan Update 2023. This plan is a critical planning tool and can now be used by water managers, such as water districts, cities and counties, and Tribal communities, to inform and guide the use and development of water resources in the state.

California Water Plan Update 2023 began with the vision: “All Californians benefit from water resources that are sustainable, resilient to climate change, and managed to achieve shared values and connections to our communities and the environment.” To tackle this ambitious vision, California Water Plan Update 2023 focuses on three intersecting themes: addressing climate urgency, strengthening watershed resilience, and achieving equity in water management.

More information

Continued on next page

As California experiences more weather extremes due to climate change, planning for the future will be critical for the resilience of the state’s water supply. To help guide those efforts, DWR has released a new State Water Project (SWP) Risk-Informed Strategic Plan to ensure a reliable, sustainable, and resilient water supply through 2028 and beyond.

The plan, known as Elevate to ‘28, furthers the implementation of DWR’s department-wide strategic plan. Elevate to ‘28 contains organization-wide perspectives including the mission, vision, and purpose of the SWP while integrating risk management to be better equipped to serve the water needs of California.

Read the plan: https://water.ca.gov/Programs/StateWater-Project/SWP-Strategic-Plan

On March 3-8, 2024, Garret Tam Sing and Ricardo Pineda from DWR participated in the Association of State Floodplain Managers’ (ASFPM) Flood and Resilience Dialogue Expedition (FREDx) in Puerto Rico (PR) to explore and discuss several topics, including PR’s current flood risk profile, ongoing mitigation and adaptation efforts, and collaboration between ASFPM Headquarters and the PR’s Planning Board. Participants included officials, scientists, the private sector, and academic institutions. This visit explored the progress made in PR since Hurricane Maria in 2017. One primary focus was intended to compare the policies and

practices in PR with those in mainland US, and to produce an executive report summarizing the findings. In addition, technical field visits were conducted in San Juan and the eastern part of the territory. PR intends to become more proficient in administering the rules and regulations of the NFIP to reduce flood losses, in addition, PR is targeting the certification of 60 Certified Floodplain Managers (CFMs) this year.

On March 11-14, 2024, Garret Tam Sing from DWR participated in the ASFPM’s Certification Board of Regents (CBOR) meeting in Salt Lake City, Utah. Items of discussions included the CFM retention study, offering the CFM exam in Spanish, a briefing on the ASFPM Puerto Rico Delegation, ASFPM online courses, and the CBOR booth at the 2024 ASFPM Conference.

FEMA’s Technical Mapping Advisory Council

Salomon Miranda from DWR participated as a subject matter expert in the FEMA’s Technical Mapping Advisory Council (TMAC) efforts towards the TMAC’s 2023 annual report, which included addressing the use of 2D floodplain mapping, communicating complex data to communities, Special Flood Hazard Area definition changes, and addressing placing fill in the floodplain. When posted, the report can be downloaded from the following link: https://www.fema.gov/flood-maps/guidance-reports/ technical-mapping-advisory-council/reports

Questions?

Nikki Blomquist, Advisor

California Department of Water Resources

Nikki.Blomquist@water.ca.gov (916) 820-7749

Salomon Miranda, Advisor

California Department of Water Resources

Salomon.Miranda@water.ca.gov (818) 549-2347

See the latest news stories relating to Hawaii’s floodplain management issues. For the transformed flood information platform from Hawaii visit their exciting weekly blog at https://waihalana.hawaii.gov/

Some of the latest articles relate to the DLNR Listening Sessions, the new NFIP Coordinator, and various Hawaii floodplain topics, provided by the DLNR Engineering Division.

For archived Wai Halana Newsletters (prior to 2018) https://dlnreng.hawaii.gov/nfip/wai-halana/

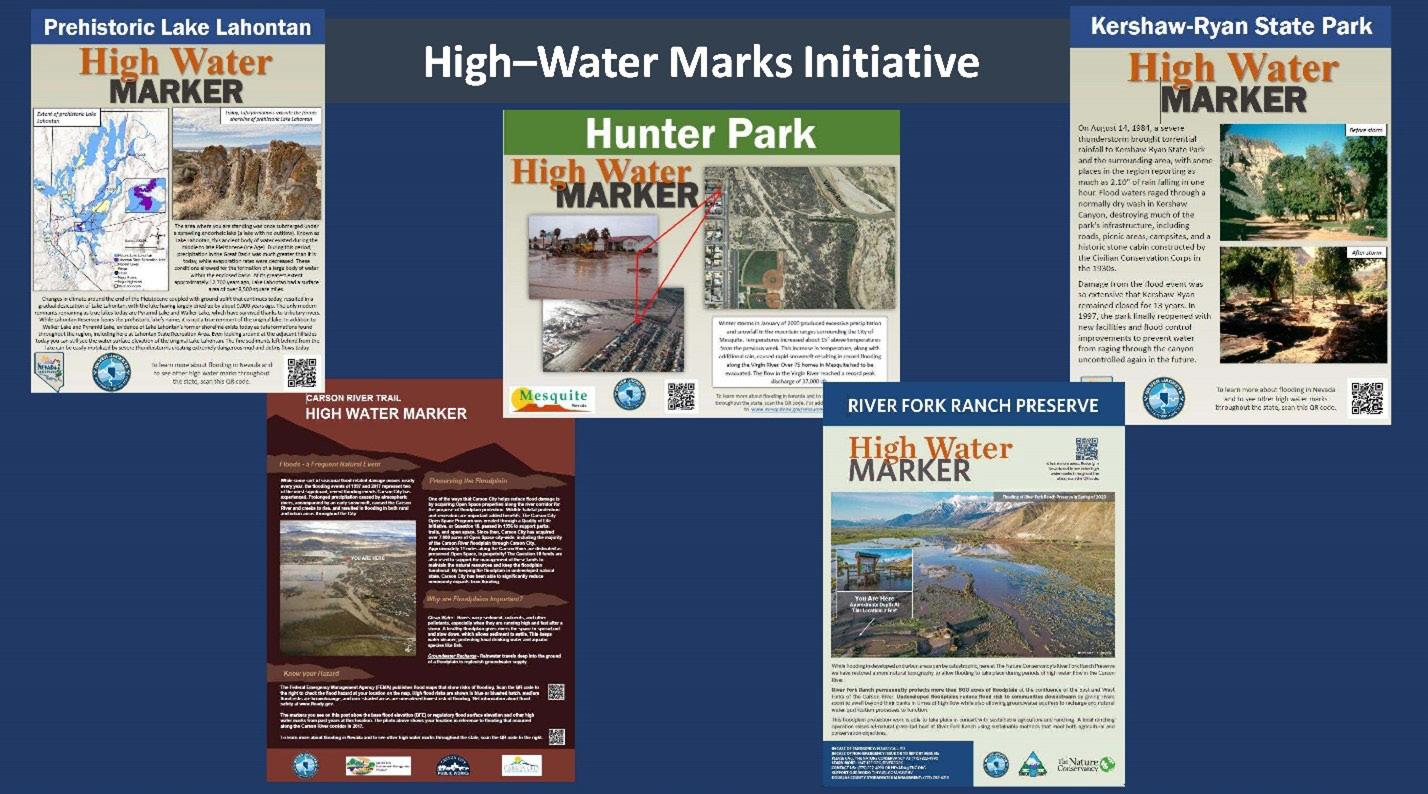

Nevada Floodplain Management Program Updates:

The first training for the 2024 Nevada Watershed University series was Floodplain Management Insights for Success! hosted by the Nevada Silver Jackets on Wednesday, March 13, 2024. The topics for this virtual training included:

• Water Year Recap & Panel Discussion: What was learned from the 2023 events and actionable takeaways.

• Community Rating System: Achievements & Challenges

Riverside County Flood Control and Water Conservation District is pleased to launch its inaugural Hydraulic Design Manual, a comprehensive resource aimed at providing engineers with essential criteria and guidance for the design of stormwater management facilities in Riverside County. The chapters include: 1-Introduction, 2-Submittal Requirements, 3-Hydrology, 4-Hydraulics of Gravity Flow Systems, 5-Street Drainage, 6-Underground Storm Drains, 7-Culverts and Bridges, 8-Open Channels, 9-Hydraulic Control structures, 10-Detention Basins, and 11-Debris Barriers/Basins. The District’s Hydraulic Design Manual is on the District’s website: Hydraulic Design Manual.

The Nevada Silver Jackets team is planning the next virtual training for the series in June 2024 on the topic of Engineering with Nature. For future training, the Nevada Silver Jackets team is tentatively planning one in July 2024 on the topic of Mitigation Funding for Rural Communities and one in August 2024 on the topic of Unhoused Populations

Stay tuned for more information about the next, and future, virtual and in-person training opportunities on the NevadaFloods.org website on the Professionals page.

Mike Nowlan

Nominations for serving on the Board of Directors of FMA are now OPEN! Like all great endeavors it takes commitment, patience, and courage to speak your voice and allow others to speak theirs, and trust that progress will ultimately occur.

Last year I put out the call to all of you in the newsletter, and the time has come once again, as we have elections every year. Our wonderful association will only continue to be as good as the combined contributions of all of its members. Part of those contributions must include some of you stepping up into a leadership role to ensure the health and stability of FMA, and provide vision for the long term.

FMA is facing many challenges and pressures to meet not only the networking and educational needs of its members/attendees, but to also listen and thoughtfully respond to the social issues affecting floodplain management. To be honest, one of the greatest challenges may be to keep the focus on floodplain management. This will not effectively happen if our membership, and particularly our emerging professionals, do not speak up substantively. I do not pretend that this is an easy ask, and it can include some modicum of self-promotion. But, I will be frank. Leadership can sometimes feel like iron sharpening iron, and small amounts of “friction” may be generated in the process of sharpening our collective focus.

None of this is intended to dissuade you from the challenge, but it is a challenge. Nothing that is worthwhile is easy in this world. But I know that there are a great number of capable, caring individuals out there that are willing to do what is hard and what is right for our often under-appreciated profession and constituencies. Much of what we do is noble in trying to keep people and property from being harmed/ damaged by flooding. We do not always succeed perfectly, but that should not prevent us from trying to do the most good possible, even in the face of adversity or intransigency.

The following list is the complete list of positions that will be voted on this election cycle; Board Chair, Board Vice-Chair, Board Treasurer, Board Secretary, Northern Private, Southern Public, At-Large 4 Nevada, At-Large 2, and At-Large 5.

The four Executive Board positions (Chair, Vice-Chair, Treasurer, and Board Secretary) are elected from someone who has already served on the Board, so it is not an entirely open nomination process for these four positions. As described in last year’s article, these positions require experience on the Board, to understand how FMA and the Board operates before being asked to lead it. The five remaining open positions are open for anyone fitting the minimum qualifications. The Northern Private position is for a private-sector floodplain professional in northern California/Nevada. The Southern Public position is for a public-sector floodplain professional in southern California/Nevada. While the At-Large 4 Nevada position is limited to Nevada floodplain professionals, the At-Large 2 and At-Large 5 positions are for any floodplain professional anywhere in the FMA region. The election of qualified nominations will occur prior to the next conference.

I want to encourage you to nominate others or yourself by contacting our Executive Director George Booth at fmaed@floodplain.org, or me at mnowlan@ woodrodgers.com, or anyone on the Board that you know or are comfortable with, by July 1, 2024. The list of FMA Board members is at the beginning of this newsletter. I may be contacting some of you directly to help this process, using every option available to secure a healthy number of nominations. Please do not assume that we’ve got it covered already and this is just a formality! We want everyone interested to tell us so we can hear all voices.

The FMA Newsletter welcomes the input of its members and now our extended family of readership to contribute to the conversation! Keep the great articles coming! We need to hear from all of you. There’s always room for more to join the ranks of published authors. Showcase your programs, projects, tools, policies, regulations or ideas to hundreds of floodplain management professionals throughout the U.S.! Articles must be submitted in Word format to fmaed@floodplain. org and may contain 2-3 small pictures. Preferred length is less than 850 words.

For more details, call (916) 847-3778.

Contributed by Eric Simmons

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) plays a major role in floodplain management by underwriting homeownership with mortgage insurance and establishing minimum standards for buildings constructed under a HUD program. On April 23, 2024, HUD published its Federal Register final rule to better protect communities and taxpayer-funded investments from flood damage. HUD updated existing floodplain regulations to require a greater level of flood protection for new construction and substantial rehabilitation projects. Building to this standard reduces flood loss to human life and property and minimizes the direct impact of flood damage on households across the country.

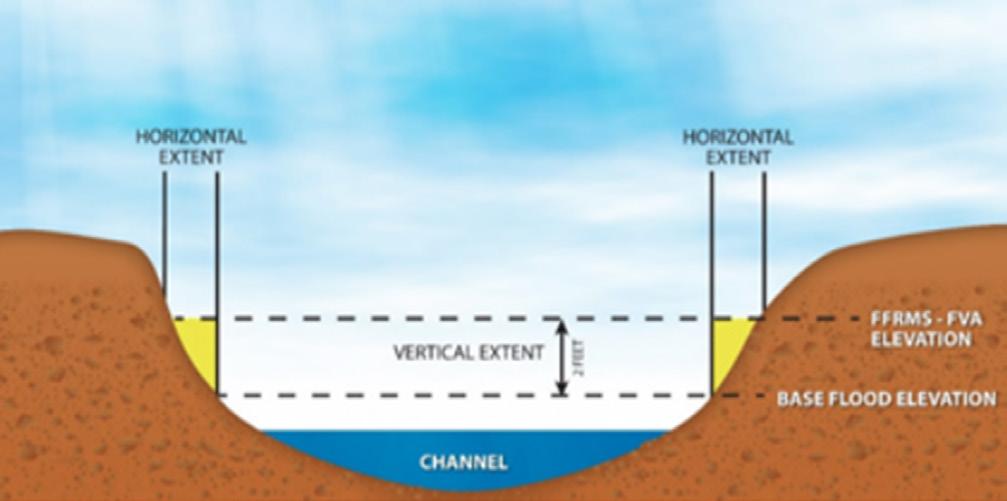

This rule expands the floodplain of concern from the 100-year (1% annual chance or base) floodplain to a newly defined “FFRMS floodplain.” The Federal Flood Risk Management Standard, or FFRMS, floodplain is an expanded area both horizontally and vertically (example shown below) from the 1% annual chance (base) flood elevation. The rule requires HUD-funded projects that newly construct or substantially improve structures within this newly defined floodplain be elevated or floodproofed to this higher FFRMS floodplain elevation.

This rule establishes a preference for (but does not require) use of a Climate Informed Science Approach (CISA) to determine the floodplain of concern for HUDfunded projects. The floodplain identified using CISA provides the elevation and flood hazard area based on best-available, actionable hydrologic and hydraulic data. CISA maps provide more forward-looking information than existing Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs published by FEMA), many of which have not been updated in decades. When CISA maps are not available for a particular HUD-funded project, the rule provides multiple alternate approaches to identify the FFRMS floodplain. This means with or without available

CISA mapping, there is a predictable option for compliance with the improved floodplain management standard.

HUD-funded projects within the FFRMS floodplain are required to complete the 8-step process unless excepted or permitted to complete an abbreviated 5-step process. The 8-step process is used to ensure HUD and responsible entities consider how their actions affect floodplains or wetlands and the people that depend on these important areas. The rule also allows public notices required for environmental reviews to be published online on appropriate government websites.

The final rule also updates HUD’s minimum property standards for one- to four-unit family housing under the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) mortgage insurance program and low-rent public housing programs. FHA is the part of HUD that provides mortgage insurance on property loans that meet certain requirements. The new rule requires that the lowest floor in newly constructed structures be built at least two feet above the base (1% annual chance) flood elevation. The rule does not, however, require consideration of the horizontally expanded FFRMS floodplain under these minimum property standards.

FAQs as well as more information on these strengthened floodplain management standards is on HUD’s website

Contributed by Eric Simmons

Our August 2023 newsletter introduced American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) Flood Supplement 722. This article introduces FEMA’s new Building Designer’s Guide and provides an update on ASCE’s new minimum design standards, which were developed by hundreds of volunteers from public and private sectors, regulators, practitioners, academics, and design professionals.

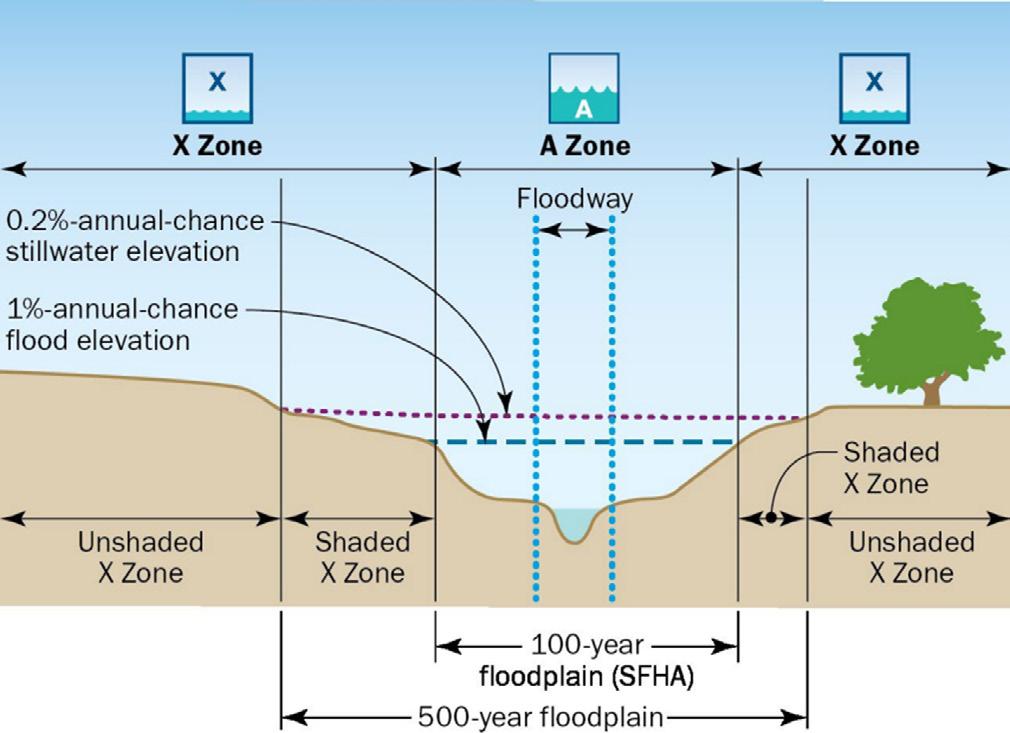

In April 2024, FEMA released the Designer’s Guide (figure from P-2345 above showing typical flood zones from riverine flood source) to using the ASCE Supplement, which is available in the ASCE library. The Guide is a considerable 175 pages and serves as a companion document to ASCE 722. It’s a supporting document for ASCE’s new standard that includes flood load combinations using mean recurrence intervals and helps designer’s calculate flood loads on a proposed structure. The Guide provides design examples for riverine and coastal scenarios; it points to helpful resources and available data sources.

The successful development of the new flood standard is due to the data, studies, and expertise of multiple agencies as well as their partners. ASCE 7-22 realizes a safer basis for development than the outdated 100-year (1% annual chance) standard is needed for resilience and wise development outside the highest-hazard areas of a floodplain.

The standards in ASCE 7-22 are being incorporated into ASCE 24, Flood Design and Construction, this year (ASCE 24-24). The current version of ASCE 24 was last revised in 2014 (ASCE 24-14). ASCE 24 is a referenced standard in the International Code Series (I-Codes) and the National Fire Protection Association 5000 code. In the International Building Code (IBC), flood provisions are included by reference to ASCE 24.

Please contact John.Ingargiola@fema.dhs.gov or Mariam.Yousuf@fema.dhs.gov if you are interested in learning more about the new standard or receiving a presentation on flood-resilient design. FEMA looks forward to discussing the important shift to improve the performance of structures subject to flood events at the annual conference in September. The cover of FEMA’s new Designer’s Guide is below.

Solving the most pressing water-related issues to improve our region’s built and natural environments

Water Resources Planning

Program Management

Environmental

Geotechnical

Civil Design

Construction Management

Information Management

Grant Writing

Marisa Perez-Reyes, with Lisa Beutler

Reprinted from AWRA’s IMPACT magazine

Much has been written about the influence of landuse changes on flood risk. Human actions such as deforestation, urbanization, and agricultural practices have all increased the occurrence and intensity of floods, and climate change is accelerating their frequency and intensity. Traditional flood protection measures such as dikes and dams are not sufficient to manage a supercharged system. Nature-based solutions (wetlands, widened floodplains, etc.) can claim more land than traditional flood control methods, making it less attractive, particularly when solutions rely on the use of privately owned working landscapes. Asking landowners to cede their property for flood management often requires compensation or incentives, resolution of property rights issues, public subsidies, and engagement of stakeholders in new ways. Even publicly owned property is typically set aside for dedicated uses, which don’t include the addition of new flood features that may interfere with that use.

In all these scenarios, flood is a land management problem, but what if it wasn’t? What if flood was a benefit? For the past five years, a group of Californians who work for the state, local public agencies, universities, nonprofits, federal agencies, and businesses and who manage private and public land have worked together to answer that question. They believe that using floodwaters for managed aquifer recharge (called Flood-MAR) is a climate adaptation. By using one land management challenge—flood events— it solves another challenge—groundwater overdraft.

Flood-MAR has transformed from a concept held and practiced by a few to the organizing principle of a California governor’s executive order on groundwater recharge. And the story of this shift involves managing complexity and working together. It also demonstrates best practices for overcoming interconnected physical, social, and policy challenges.

While Flood-MAR isn’t an option everywhere, it is in California. Historically, the state’s winter snowpack, paired with human and nature-based conveyance infrastructure, faithfully delivered spring and summer snow melt to the many people that wanted it, when they wanted it. This system allowed people to live and work in places that otherwise could not sustain them. When nature didn’t cooperate and generated massive volumes

of water, the flood management system worked to tame it. When there was too little water, groundwater basins filled the gap. In a typical year, about 40% of the state’s total water supply comes from groundwater, but in dry years, groundwater has contributed up to 60% (or more) of the state’s total supply.

With climate change, what was once perceived as a somewhat predictable weather cycle has instead delivered wild swings, resulting in extended droughts punctuated with drenching from extreme storms. Concurrently, warming temperatures have put snow melt into a system not designed to manage the increased volumes. And further, extended droughts and continued alteration in land-use patterns have caused groundwater basins to become overtaxed, in some cases beyond repair. This untenable situation has led to the implementation of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). This law requires sustainable management of California’s aquifer supplies and has significantly altered what had been the go-to strategy of just pumping more groundwater in extended droughts.

The consequences of the altered climate and landuse decisions have been extreme. Entire California communities lack access to safe and affordable drinking water while facing increased risks from flood inundation. The scale of the crisis advanced conversations about the use of Flood-MAR. Initial investigations by the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) indicated that Flood-MAR offered promise in helping to mitigate the impacts of wild weather swings.

Recognizing the potential of Flood-MAR, DWR convened a Research Advisory Committee (RAC). The RAC, made up of 40 professionals across multiple disciplines, explored the highest priority steps needed to advance Flood-MAR projects. This entailed considering 13 different themes, including changes in water governance, management, infrastructure, water rights, and water and land-use practices. After deliberations, the RAC members advanced a comprehensive list of recommendations and priorities, culminating in the development of the Flood-MAR Research and Data Development Plan (R&DD Plan).

As is often the case with bodies of this type, in addition to the specific recommendations generated, the RAC members recognized the value of the coordination and partnerships they had cultivated. Specifically, the RAC recognized collaboration as critical to achieving most of the research and data sharing activities proposed for strengthening Flood-MAR implementation (for more on this, see Addressing Complex Problems Together: A Network Story, the January 2023 DWR-sponsored white paper from which this article was adapted). From this point, a dialogue began about a network amplifying the value of informal engagement, collective thinking beyond disciplinary silos, and sharing different perspectives. Soon, a recommendation emerged to create a collaborative Flood-MAR Network.

To expand on the concepts being forwarded by the RAC an October 2019 forum considered and acted upon the recommendations in the R&DD Plan, including discussing how, and in what form, a Flood-MAR Network could be established. These conversations confirmed that more than physical infrastructure would be needed to achieve Flood- MAR’s goals. New institutional structures and practices would be required. And they would need to facilitate a shared purpose “among people who each have something to give and something to get as they work alongside each other.”

Attendees listen to presenters during the 2023 Flood-MAR public forum, held at California State University of Sacramento on November 7, 2023. Source: Marisa Perez-Reyes, Stantec

As described in the January 2023 paper on this topic, “a network is defined as an intentional gathering of people and organizations, focused on addressing one or several complex and shared challenges or opportunities, undertaking shared efforts to strengthen each of its members while advancing shared interests.”

Networks allow individual action and organizational autonomy. In their 2011 book, Networks That Work: A Practitioner’s Guide to Managing Networked Action, Paul Vandeventer and Myrna Mandell explain that networks have been found to “bring greater scale and focus, more productive kinds of working relationships, and more lasting effectiveness when addressing public problems.”

In the Flood-MAR network, potential members identified five key activities consistent with their areas of expertise and that aligned with the proposed learning/ coordinating collaborative:

1. Identify and fill knowledge gaps.

2. Share Flood-MAR body of knowledge.

3. Communicate with Flood-MAR-interested parties on work to add to and build up collective knowledge to inform future work in an efficient and effective way.

4. Educate and engage on how to get things done.

5. Support Flood-MAR implementation efforts.

Continued on next page

A shared agenda was forged by identifying broad objectives, brainstorming specific projects, and outlining initiatives that can help meet those objectives. Ultimately networks are only sustainable when based on a member’s interest and ability to follow up on projects, although participation may occur to varying degrees if it advances network initiatives.

Like all formal networks, Flood-MAR requires some organizing principles and structure to facilitate its shared efforts. In the case of Flood-MAR, a leadership team helps to inform network activities. This is not a directive role, instead it is a supportive one, helping with the development of working agendas and support for implementation of the agendas adopted by the network. As described in the January 2023 paper, some best practices include:

1. Memorialize expectations in a network memorandum of understanding (MOU) or charter. As the network is a living, learning entity, it should continually revisit its purpose, to affirm that activities are meeting the desired objectives. The charter should include principles of engagement, as well as expectations for meeting frequency and format.

2. Identify resources and opportunities for integration with other programs. This step will help ensure the network gains credibility and traction, maintains relevance, and operates efficiently.

3. Design communication mechanisms and messaging based on the role the network plays in sharing its work internally among members and with a wider external audience.

Since it first convened in December 2020, members have met at quarterly workshops to brainstorm and refine the initiatives. In addition to the quarterly workshops, a small planning team composed of DWR staff and consultants meets regularly with network members to advance the ideas expressed during workshops. Learning groups encourage the flow of information among network members as well as with outside groups and interested parties.

The primary intent of the Flood-MAR groups is to focus on information exchange; however, their work has led to coordinated actions. The Forecast-Informed Reservoir Operation (FIRO) Group was originally convened with the goal of engaging experts in recharge and flood management to fill knowledge gaps and explore integration opportunities, but it has expanded its collaboration into shared initiatives. Other initiatives or action teams have also advanced specific actions that support the network’s purpose, one example being the volunteers that manage a group website. At the time of this publication, there have been 26 Lunch-MAR webinars, 11 learning circle meetings, six action teams, nine Network workshops, and four forums, the most recent in November 2023.

As found in the January 2023 white paper, the interdependencies inherent in the way that people, land, and water interact suggest a broader role for the use networks. The intentional development of networks uncovers shared purpose, builds rapport and trust, improves understanding of complex issues, and supports more efficient or effective water and land management at different scales and in different contexts.

Flood-MAR is one of many strategies that can be used, including many where coordination and integration across a wide variety of administrative and infrastructural systems is needed to pursue better outcomes. This reality creates a significant opportunity to improve the integration of land, surface, and groundwater management to create sustainable practices and provide benefits to meet local, regional, and statewide needs.

As summarized in the December 2023 paper Celebrating Five Years of Flood-MAR, “the pace at which the practice of Flood-MAR has advanced in California is testament to the power of collaborative action, and how innovation and opportunity can drive rapid transformation.” It is also a quintessential example of the broad-spectrum climate adaptation needed in California and elsewhere.

The “New” Normal California’s historic flood and drought cycles are well documented. In The Watering of California’s Central Valley, Daniel Grant documents how just after gaining statehood, California settlers grappled with extreme weather events. First came extensive flooding over the winter of 1861-62, and then, the worst drought in over a decade. He writes, “Settlers had to constantly assess their situation: were they living through a particularly turbulent couple of years, or were these water fluctuations the new ‘normal’ that they had to adjust to?” The rise of irrigated agriculture in the 1870s gave an impression of water abundance and consistency in an otherwise erratic climate, obscuring the urgency of disaster adaptation during uneventful years, thus creating the illusion of “normal” climatic variation. Today, climate change has simply upped the “normal” response, with increasing numbers of weather events at intensities exceeding existing infrastructure capacities.

This article was adapted from the white paper, Addressing Complex Problems Together: A Network Story, by Orit Kalman, Mike Antos, Marisa Perez-Reyes, and Jenny Marr, published by the California Department of Water Resources in January 2023.

Marisa Perez-Reyes (marisa.perez-reyes@stantec.com) convenes multiparty working groups, coordinates complex projects, and guides clients through publicly engaged water resources planning efforts. They have worked extensively across California to improve water planning and governance to better engage communities in decision making. At Stantec, Marisa provides facilitation support to groundwater subbasins under SGMA and other local public agencies.

Santa Clara, San Francisco, Santa Rosa, Salinas, and Truckee

schaafandwheeler.com

Ricardo Aguirre

Reprinted from AWRA’s IMPACT magazine

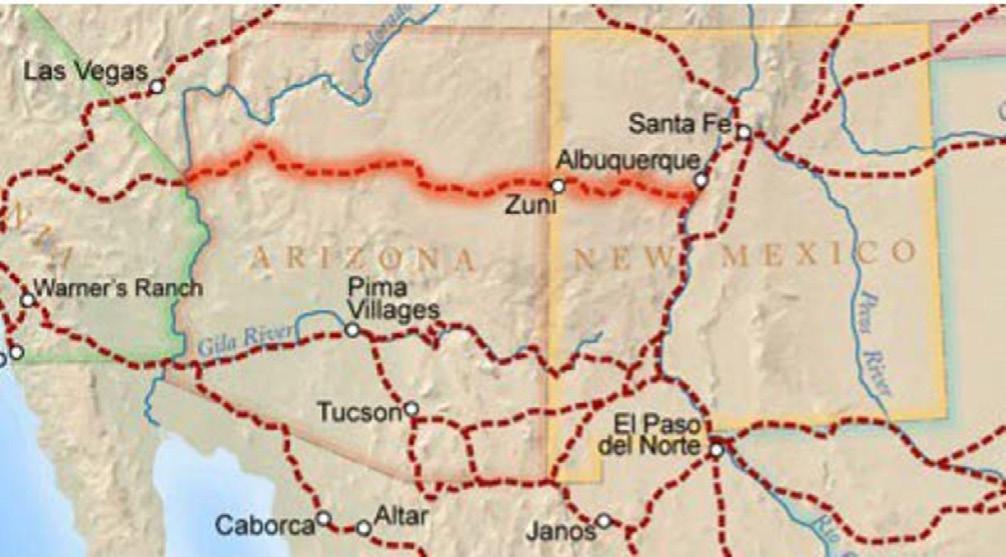

Pioneers headed to California faced many barriers, including a lack of water along the southwestern route for wagon trains. In 1855, Army Major Henry C. Wayne seized on a unique solution. He had 33 camels delivered to Texas. Two years later the camels were put to the test by wartime hero Edward Beale. Beale, famous for bringing the first gold nugget from California to Washington, D.C. was to survey the desert for a wagon trail from New Mexico to California (Figure 1) and bring along 25 camels to test.

The presence of the exotic beasts created a buzz and Beale’s journey was well documented. Today Beale’s route is Interstate 40 and according to Along the Beale Trail, his frequent journal entries described continually flowing streams and large expanses of tall nutrientrich green grasses that often impeded his progress. In promoting his new trail route, Beale proclaimed that his route offered water sources a minimum of every 20 miles.

Others recorded similar landscapes. In 1875, William Hornaday, an American zoologist, conducted expeditions throughout the Western states, where he observed massive bison herds, some so large that it took them five days to cross. The bison were a part of a vast diverse network of grazers and predators that included antelope, horses, elk, deer, wolves, coyotes, wildcats, and bears.

Research chronicled by Dan Flores in American Serengeti reveals that the grazers and predators that Hornaday observed coevolved with the grasses observed by Beale. According to Flores, the landscape that supported the

volume of wildlife during the mid-1800s was a “complex ecology at least 20,000 years old” . . . “far from the empty ‘flyover country’ of recent times.”

The camel experiment eventually ended. While Beale came to appreciate them, the camels scared the horses and mules, and most soldiers refused to learn to ride them. The herd was sold at auction or turned loose into the desert, and reports of feral camels continued into the early 1900s.

But what happened to the landscapes described by Beale and others?

The decline of watershed health parallels the application of industrial revolution ideas (mechanization, technology, and efficiency) onto the natural landscape. Overgrazing, the federal native species killing program, industrial agriculture, and civil infrastructure such as highways, railroads, dams, canals, and cities, took their toll on unique Western landscapes and their ecology. This human intervention eradicated the migratory patterns established by the native grazers and their predators, which were supported by and had coevolved with the Western grasslands. This accelerated decline led to the 1930s Dust Bowl and today’s desertification.

Industrial approaches influenced how humans see the world and created a belief that technology can resolve environmental problems. Such technology has delivered numerous modern miracles, but agriculture, health, erosion, wildlife, rangelands, forests, and chief among them water security are not only failing but even appear to be accelerating the existential threats to humanity.

These shortcomings can often be seen when a mechanical development is overlayed onto nonmechanical organic systems. Civil infrastructure is routinely a culprit, especially the infrastructure that affects drainage (e.g., roads, bridges, culverts, railroads). Because civil engineering projects are land-connected projects, practically all civil infrastructure affects how water drains over a landscape. Industrial Farming Practices Reduce Soil Water-Holding Capacity The industrial farming practices of tilling and applying pesticides and fertilizers have had similar effects on how

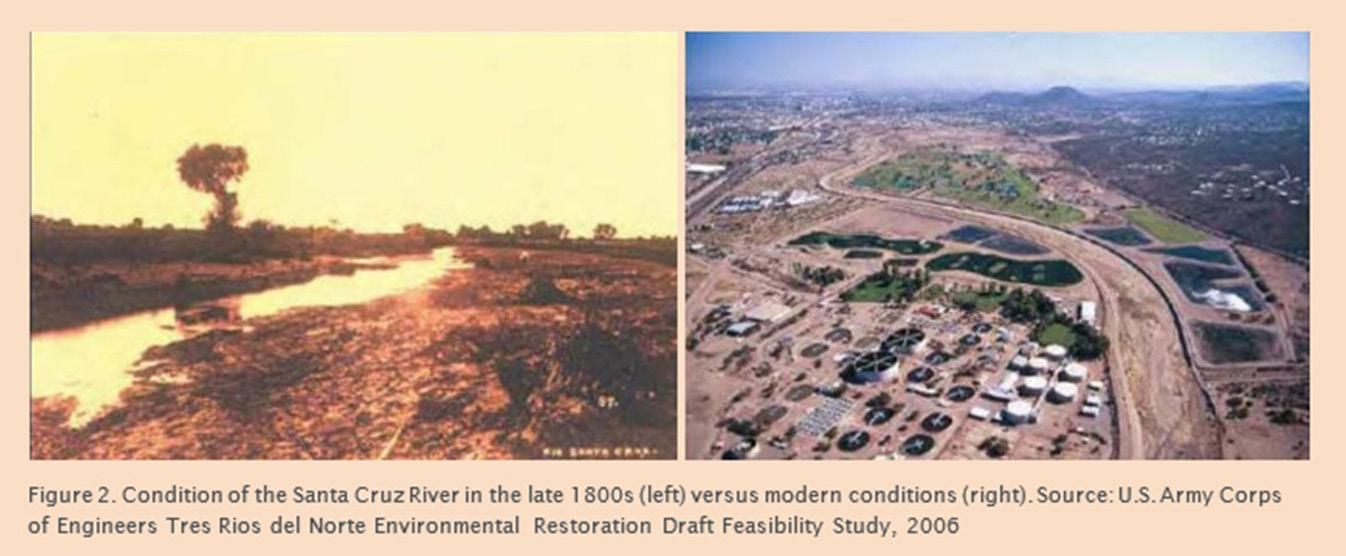

Case Study: The Santa Cruz River

In the late 1800s the Santa Cruz River, north of Tucson, Arizona, was a perennial watercourse meandering through a widespread mesquite bosque consisting of diverse wildlife with groundwater at or near the surface in the surrounding are (figure2). Today the Santa Cruz River is a straigtened and channelized dry riverbed. With no upstream dams and concrete fortified embankments that allow development to encroach onto the floodplain, the river is prone to cause flooding, especially during the more intense monsoonal episodes that follow long drought periods. The altered river and surrounding hardscapes, with dead compacted soils, can no longer infiltrate stormwater. These realities, as well as pumping, have led to groundwater depths in the area now exceeding 100 feet.

and whether land stores water. These practices reduce soil organic matter—i.e., soil carbon—which leads to soil compaction at the plow depth and a direct reduction of soil water-holding capacity. It is this relationship that shows land is a credible and important medium for storing water. Exploring the sequential effects of applying nitrogen fertilizer alone, as warned by Albert Howard in the 1940s and University of Illinois researcher Richard Mulvaney today, shows how it proliferates soil organisms that feed on organic matter. This practice was initially thought to be good, but new evidence demonstrates that it causes an eventual collapse to the soil structure after the soil organic matter has been consumed and soil organisms die. The result again is compaction and increased runoff and erosion.

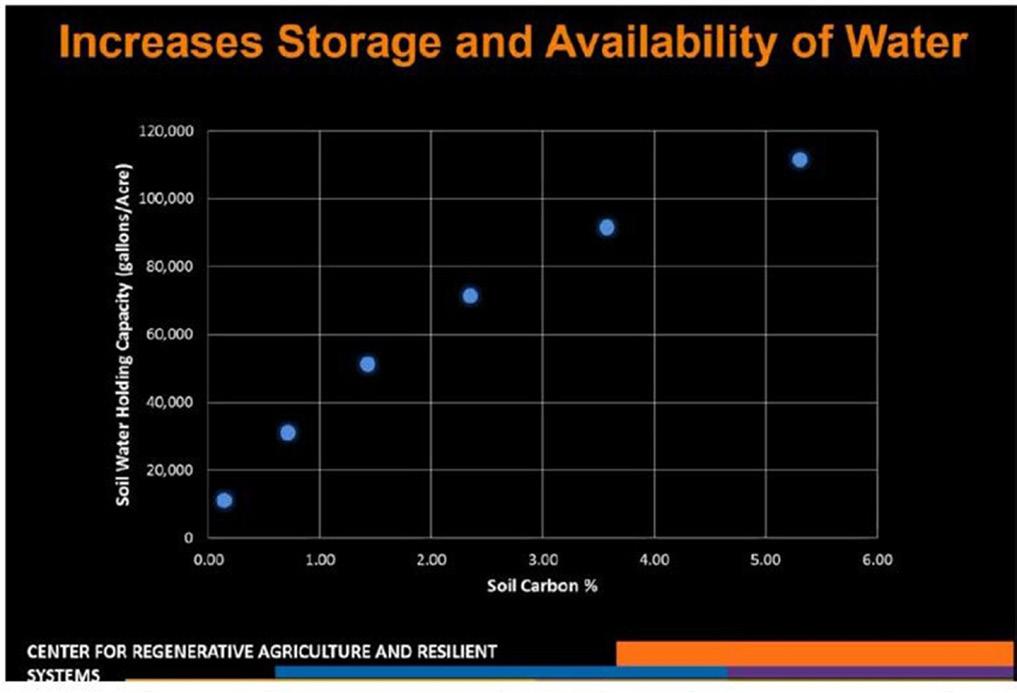

In Cows Save the Planet, Judith Schwartz explains that for every 1% of increased soil carbon the land can retain up to an additional 60,000 gallons of water per acre. David Johnson’s research (Figure 3) equates 1% to 40,000 gallons of water per acre—still quite significant. According to Elaine Ingham, however, soil organic matter (soil carbon makes up 58% of soil organic matter)

must be at a minimum of 3% to start prompting an effective water and nutrient cycle (soil types and other factors may cause variations). Unfortunately, most arid soils in the Southwest have degraded to below 3% soil organic matter.

Because mainstream farming practices kill soil life and dead soil cannot hold water, farmers are compelled to increase their irrigation rates, which continues the cycle of adverse effects on long-term water security. Water infiltration is a function of compaction and surface soil salinity, indicators of the level of soil organic matter.

The inability of dead soil to infiltrate water will lead to evaporation, causing salts to be left behind, furthering the soil’s inability to infiltrate water. This gives rise to the need for yet more irrigation, according to Pillar of Sand author Sandra Postel.

The megafauna observed and documented around 150 years ago offer clues for proper land management, but relatively few ranchers have been willing to change

Continued on next page

their livestock management practices. Those who have attempted mimicking natural conditions have had differing levels of success. Regardless of their level of success, they have often been derided by those with biases vilifying livestock, especially cattle. Unfortunately, these biases often show up purporting to be science, in scientific studies that have been misapplied, poorly performed, ill-conceived, and often misunderstood. For example, research by Oldeman and Engelen in 1991 suggested that livestock overgrazing had caused as much as 20% of the world’s pasture and range to lose productivity and that the global grass-eating livestock herd, in 1991 numbered about 3.3 billion, was unlikely to increase much, if at all. Assuming the research was sound, one could reason that it provided both sufficient evidence and a cause for concern that the degraded grasslands were caused by overgrazing. However, an issue with overgrazing does not necessarily mean that the simple presence of livestock was to blame. And yet, many projected their unfounded biases about how the degradation happened to criticize the livestock rather than livestock managers. In fact, the management of livestock and not the livestock themselves is key.

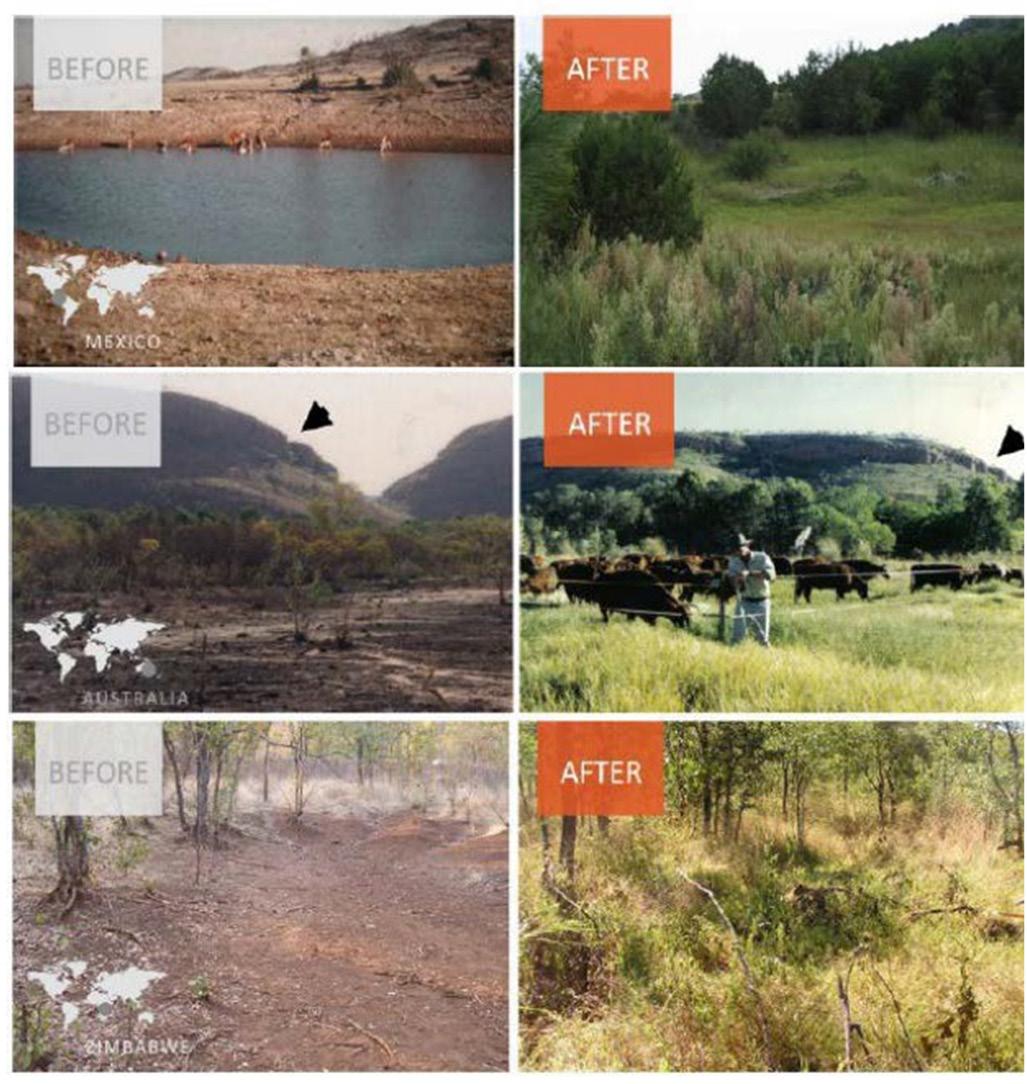

Land managers can use a concept called animal impact and herd effect to increase the carrying capacity of the land, improve watershed health, and provide long-term water security for future generations. Land management practitioners from varying climates and soil conditions around the world (see Figure 4), including the Southwest, have demonstrated that properly mimicking the predatorprey relationship induces the conditions of animal impact and herd effect. In these cases, animal impact consists of dunging, urinating, salivating, and trampling, and herd effect consists of a behavioral change that affects soils and plants when many animals are bunched closely together to protect themselves from predation.

High stock density, or many animals in small areas for short periods of time with longer rest periods, has proven to mimic the animal impact and herd effect that evolved with the soils and vegetation to create watershed health in erratic rainfall environments like the Southwest. This is the key that makes possible the restoration of grasslands on healthy high-water-holding capacity soils.

Soil Water Holding Capacity vs. Soil Carbon. Source: Center for Regenerative Agriculture and Resilient Systems

Can humans achieve this outcome on a large enough scale to make an impact? Doing so would require a practical and disciplined approach to land management that vigilantly looks for signals to adjust willingly and without delay. Practitioners willing to dedicate themselves to the level of discipline required to properly mimic nature must also remain focused despite detractors that only read or do science from an intellectual perspective rather than conduct practical experiments and adjust based on nature’s feedback.

Broadly speaking the combined research of Schwartz, Johnson, and Ingham indicates that 80,000 gallons of water or approximately three inches of rainfall per acre is retained when the soil organic matter is above that crucial 3% level necessary to prompt watershed function. The largest storms in the Southwest during the year are monsoonal and can have up to three inches of rainfall in a very short period, so in an area that, on average, receives 12 inches per year, practically all the rainfall throughout the year could be retained. The volume of water stored by that 1 acre of land alone would be approximately 326,000 gallons of water and with a per capita demand of 100 gallons per day, that acre could support approximately nine people per year. Scaling up to the volume of water for large watersheds, consisting of hundreds of square miles, reveals the potential of land as a credible medium for storing water.

Demonstration of properly mimicked predator-prey relationships over three different continents in countries with low rainfall conditions: Mexico (top), Australia (middle), Zimbabwe (bottom).

The lessons of the past inform the reasons natural methods to store runoff are critically needed and are even superior to technological methods when considering how to address the already occurring water scarcity in much of the world. This reality affirms Lindy’s Law, which says that the longer something has been around the longer it will be around, and alternatively the less time something has been around, the more vulnerable it is to extinction. This offers food for thought when comparing the results of a four-billion-year-old perfected natural system to the results of 150 years of science and technology-based industrial practices.

Ricardo Aguirre (raguirre@westconsultants.com) is the director of land management and water security with WEST Consultants. He is also the executive director of Drylands Alliance for Addressing Water Needs (DAAWN). He has a BS in Civil Engineering from the University of Arizona and an MS in Civil Engineering from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

At Forgen, we leave the planet better than we found it. Our geotechnical and specialty civil construction capabilities are applied each day to restore and strengthen our nation’s levee system for generations to come.

Stream, Channel, River, and Basin

Coastal Zone Restoration and Tidal Estuary Enhancements

Stormwater, Erosion Control, and Underseepage Improvements

Tetra Tech’s innovative, sustainable solutions help our clients reach their goals for water, environment, infrastructure, resource management, energy, and international development projects.

Grace

Rogers

Reprinted from AWRA’s IMPACT magazine

In the next 30 years, researchers etimate over four million acres of U.S. land will be increasingly threatened by climate change induced flooding. Nearly 42% of the U.S. population lives in coastal areas, and without cost-effective adaptation measures, these areas could experience cumulative climate-driven damages as high as $3.6 trillion by 2100.

Louisiana, impacted by effects from hurricanes, climate change, management of the Mississippi River, and other human activities, experiences the fastest rate of coastal land loss in the country. The Bayou State has already lost nearly 2,000 square miles of land since the 1930s. In the face of this loss, nearly half of Louisiana’s population, approximately 2 million people, still call the coastal lands home, including numerous Native Americans with centuries of ties to the land, along with the settlers that later established place-based cultural ties and multigenerational family histories. Coastal dependent industries, including oil or natural gas drilling, commercial fishing, shipping through ports of the Mississippi River waterways, and tourism in New Orleans and other communities contribute significantly to the state’s economy. With so much at stake, Louisiana is pairing the most comprehensive coastal planning in the nation with massive investments for restoration and resilience that exceed $1 billion in annual spending. Investments in the 2023 Coastal Master Plan are estimated to save

between $10.7 to 14.5 billion in avoided damages while also contributing to 11,000 jobs. Yet, even with state and federal infrastructure projects to mitigate land loss and flood risk, individuals in flood-prone areas may still need precautionary actions to avoid ongoing damage to personal property or the permanent loss of land. Such actions range in difficulty and cost to execute. Ultimately, the people that live and work in shrinking places will need to consider their own capacity and tolerance for risks and then decide whether to stay and adapt or go. To be effective, planners and policy makers must understand individual and community behavior and the factors that inform decisions to act. Understanding the unique motivations that spur individual and community action improves planning and allows for more equitable allocation of resources.

Many factors can influence the actions people can or are willing to take, whether switching jobs, voting for climate policies, flood-proofing a home or business, or choosing to relocate. From 2019 to 2020, Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) partnered with Cornell University to study what drives individual choices to stay or go. Together, with partners at the Restore the Mississippi River Delta coalition, they launched a two-part social science study, “Responding to Flood Risk in Louisiana: The Roles of Place Attachment, Emotions, and Location,”

to examine Louisiana residents’ risk perceptions related to coastal land loss and climate change.

The study considered the factors that influence Louisiana residents’ decisions to respond to flood risk by measuring their place attachment, negative emotions about flood risks and the elements of a concept called protection motivation theory (PMT). PMT can be used to help predict and encourage protective behaviors and explain the thought processes used when individuals evaluate threats and potential coping responses.

The study team convened six focus groups to gather information that allowed them to develop a telephone survey focused on the willingness and perceived ability of residents to change their behavior to avoid or adapt to increased flood risk, coastal land loss and other climate impacts. Using this information they then surveyed over 800 Louisiana residents living across southeastern Louisiana and representing flood-prone parishes, as well as an inland parish that would be likely to receive climate migrants in the coming years, and a range of demographic profiles (age, ethnicity, income, etc.).

Throughout these discussions, participants indicated a strong connection to Louisiana’s ecosystems and cultural

history, emphasizing how deeply their roots are planted in the coastal landscape. At the same time, they felt they had little control over coastal land loss and their associated climate risks. Participants also noted a history of mistrust in public institutions and felt both state and federal governments could do more to build resilience for coastal communities.

The study found that the people attached to their communities were less likely to relocate, change jobs, or engage in other life-changing behaviors, even as their perceptions of flood risk increased. At the same time, strong attachment increased the likelihood of taking actions to enhance community resilience, like voting.

for new policies, especially as perceptions of flood risk increased. Participants with negative emotions, like anger or anxiety about land loss, were more willing to take life- changing actions to avoid flood risks, such as moving or changing jobs.

Altogether over one-fifth of participants were likely or very likely to change jobs (21%) or move within state (23.3%) or out of state (20.7%) as a response to their perceived risk. Yet, even when participants were willing to take on life-changing behaviors, the barriers to taking this action were often found to be incredibly difficult to overcome.

Since 2006, WES has committed to restoring sensitive and degraded ecosystems, including floodplains. California’s floodplains are essential for controlling large inundation events and fight climate change protecting communities and species habitats.

Holly Callahan

The FMA Emerging Professional (EP) group holds multiple events throughout the year to promote socialization between EPs and provide networking opportunities. In March 2024, Wood Rogers hosted the EP Mentorship Program for a lunchtime social event in Sacramento. Participants enjoyed a catered lunch of delicious tacos and had the opportunity to get to know each other through “Mentorship Bingo”.

In addition to the events with the Mentorship Program in Sacramento, the EP Committee hosted two social events in the Bay Area and in Orange County. Bay Area EP members met at Happy Hour at First Edition in Oakland to get to know each other in March, while the Orange County members met for a hike in the San Juan Creek watershed. During the event, members hiked down to San Juan Creek where due to the recent storms flow was observed over the falls leading down to the creek.

Activities included volunteering at the El Dorado Nature Center in Los Angeles on May 4, 2024, and Flood and Equity and the Impacts of Redlining, a walking tour in Sacramento on May 10, 2024. Visit the EP Eventbrite website to find upcoming events and we look forward to seeing you there!

The Newsletter of the Floodplain Management Association