13 minute read

ALL THE WORLD'S ABLAZE

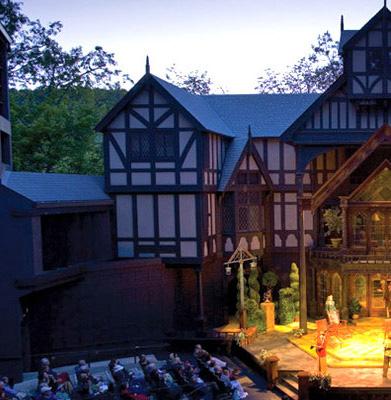

By the time my plane landed in Medford, 15 miles north of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland, the bright sun and clear skies that had followed me from Milwaukee to Portland were gone. A thick haze had reduced the sun to a pinprick; although it was only early afternoon on a lazy summer day, it felt like dusk. And that’s before I left the plane and smelled the smoke.

It was late August, 2017, and Oregon was on fire. During my ensuing five days in Ashland, I grew used to seeing people masked – not because of a pandemic still three years away, but rather because of the smoke. While trying to focus on Julius Caesar and Henry IV, I wondered whether additional shows I’d planned on seeing would be cancelled.

Advertisement

My last scheduled performance – showcasing Mary Zimmerman’s legendary adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey – was. The smoke was so bad that Oregon Shakespeare feared for the safety of actors and audience alike. Ironically, Homer’s great poem is, in part, the story of the gods’ revenge against men too busy trying to subdue and destroy the natural world to respect and love it.

During my years as a critic, I’d experienced cancellations because of rain and snow. Fog and heat. Building emergencies and medical emergencies, including Stacy Keach having a heart attack on stage while I watched, aghast (thankfully, he survived). But I’d never seen a show literally go up in smoke.

The following summer, fire would force Oregon Shakespeare to reschedule 19 shows and cancel seven; by 2019, it had moved the shows in its magnificent outdoor theater to a dreary high school auditorium. In 2018 alone, Oregon Shakespeare took a $2 million hit because of firerelated cancellations.

Oregon Shakespeare’s experience is not unique. Mike Ryan, Artistic Director of the Santa Cruz Shakespeare Festival, admitted in a recent San Francisco Chronicle interview that “in a very bizarre way, COVID actually saved our bacon this year,” given the catastrophic losses Santa Cruz would have experienced had it been staging shows during the recent California wildfires.

From Oregon to Wisconsin

Climate change has also come calling in Wisconsin, where shifts in weather have meant increasingly wet summers.

On the day I left for Oregon in August 2017, Northern Sky Theater Managing Director Dave Maier reported from Door County that Northern Sky’s two-month season had been severely affected by rain.

By the time Northern Sky’s season ended several days later – the very same day, as it happens, that I was smoked out at Oregon Shakespeare – 22 of 84 scheduled performances on Northern Sky’s Peninsula State Park stage had either been rained out or were heavily impacted by rain, resulting in a 15 percent decline in attendance.

During the 2017-19 period, Northern Sky’s weather-related events were up and its attendance was down (there was no 2020 season because of the pandemic). “This trend,” Maier made clear in a recent email to me, “was a primary motivation in the desire to secure our own indoor venue.”

Companies like Northern Sky and Door Shakespeare in Door County, SummerStage of Delafield and Optimist Theatre in southeastern Wisconsin, and American Players Theatre west of Madison all perform outside; that’s part of their appeal. Increased rainfall won’t just dampen these experiences for audiences. It will compromise such companies’ ability to continue sharing such experiences at all.

Looking back, I’m embarrassed to admit how fully my own experience in Oregon mirrored that of Odysseus sailing across the Aegean in The

Odyssey: focused on what I wanted, I cast the natural world as my enemy – a malevolent force standing in the way of my narrowly conceived desires and needs.

Never mind the trees. Never mind that satisfying my perceived needs – and leaving a carbon footprint big enough to reach an isolated theater that’s hundreds of miles from any city and thousands of miles from Milwaukee – might be part of the problem.

The trees burning in Oregon didn’t set themselves on fire. We lit the match a long time ago, and we continue to pour gasoline on the blaze.

Getting Off the Couch

When theater consistently delivers what playwright Caridad Svich calls a “couch play” – a navel-gazing, drawing-room exercise in which humans prove incapable of writing or watching anything that doesn’t place them at the center of the story – we’re going to miss this bigger picture.

“There is a story we are forgetting how to tell,” Richard Powers said in a 2019 interview about The Overstory, his magnificent novel about the forests we’re destroying in places like Oregon. “So much of who we are is wrapped into the belief that humans are independent and the rest of the world is there to serve us. We bestow a sanctity on humanity that we don’t bestow on other living creations.”

There’s a living and breathing world unfolding, beyond those theatrical black boxes into which we seek to disappear for our two hours of escapist entertainment. Why aren’t theater companies paying more attention to its looks and sounds, tastes and smells and touch? And

if we continue to ignore the larger stage that is our world, aren’t we condemning every stage on which we perform – and all the performers – to extinction?

Roughly 1 million of Earth’s remaining 8 million species of plants and animals are currently threatened with extinction. Roughly 9 million people die each year from pollution; a disproportionate number of them live in BIPOC communities. More than 3 billion people are affected by land degradation; only 15 percent of the world’s wetlands remain intact. The numbers are on the wall. Are we going to read them and act, before it’s too late?

Performance Ecology

Less than two months after returning from Oregon, I reviewed a performance in Milwaukee that gently and movingly called attention to this question. Written by Jeff Grygny and directed by Quasimondo Physical Theatre’s Brian Rott, Cooperative Performance’s season-opening show took place outside, in the modest nature preserve abutting Milwaukee’s Urban Ecology Center.

Rehearsals for Grygny’s Performance Ecology Project involved six performers – Sarah Best, JJ Gatesman, Kavon Jones, Hesper Juhnke, Jessi Miller, and Ben Yela – spending five Sundays at the Urban Ecology Center. Having first engaged in somatic exercises involving yoga, tai chi, mindfulness, dance, and theater games, they went into the woods, immersing themselves in nature by “interviewing” –

Grygny’s word – something living there. They then each journaled about what they’d experienced.

Grygny and Rott next shaped this material into a one-hour piece for audience members like me, who were led through a condensed version of what the performers themselves had experienced. That meant trying to hold yoga poses during which I buzzed like a mosquito, crouched like a squirrel, and snarled like a bear.

I cop to having felt self-conscious and silly, until suddenly I didn’t. Or as Grygny would later write of this project, it wasn’t “quite as flaky as it sounds.”

By the time I’d “warmed up” with these exercises and taken my place around a campfire on a mellow October afternoon, I was ready to watch and learn from this cast as it impersonated various living creatures, while channeling Italo Calvino to chronicle the history of the universe and

Stephan Harding to urge that we learn to better love the earth. With musician Jahmes Finlayson adding numerous twangling instruments, I truly felt what my review would later describe as the “enchantment of this magical island in the heart of urban Milwaukee.”

And while being enchanted, audience members like me were subtly being challenged to think differently, not just about the world but also about how our staged stories might make us see it in fresh ways, and with way more love.

“Environmentalists make poor progress when they just talk about how bad humans are,” wrote Grygny, reflecting later on the Performance Ecology Project. “Performance ecology tries a different tack: if we learn to care a bit more about even one little life form, we might care more about the impact our actions are having on the whole planet.”

MEET THE FUTURE OF INNOVATION

Greenturgy

Even before the 2017 fires, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival had been among those theater companies trying to both change how it uses resources and the way we think about them. A Green Task Force was formed in 2007; by 2020, solar power supplied more than half of the electrical needs of OSF’s multistory scenic and costume facility.

The company has purchased an electric rideshare vehicle. It distills its own water. It has reduced shipping costs. Most important, it has been a leader in promoting greenturgy: folding environmentally conscious practices into our thinking about plays themselves, through “green” dramaturgy that underscores the relationship between every play and its environment.

Brainchild of Alison Carey (who leads OSF’s project to commission new plays about moments of change in American history) and Amrita Ramanan (OSF’s Director of Literary Development and Dramaturgy), greenturgy draws attention to the broader environment in which a play unfolds, environmental consequences of characters’ choices, and connections between the natural worlds of play and audience.

How, for example, might Shakespeare’s transformative forests in plays like A Midsummer Night’s Dream and As You Like It make us think differently about our own green space? “Where would characters go,” Carey rhetorically asked in a recent interview, “if there were no Forest of Arden” in As You Like It? How might Titania’s plaintive monologue in Midsummer about mixed-up seasons (each dressed in another’s costume) read differently in an era of climate change and extreme temperature fluctuations?

New Plays for a New Era

So much for seeing old plays anew. Meanwhile, organizations like Climate Change Theatre Action are trying to harness such motivation to create entirely new and environmentally conscious plays. Based on a predetermined prompt involving an aspect of climate change, CCTA commissions a series of five-minute plays from around the world every two years; the plays are then made available for free readings and performances.

In 2017, the prompt was: “How can we inspire people and turn the challenges of climate change into opportunities?” In 2019, the prompt was “Give center stage to the unsung climate warriors and climate heroes who are lighting the way toward a just and sustainable future.” Anthologies of plays from both 2017 and 2019 have been published.

Running from September 15 to December 21, CCTA’s 2019 biennial involved 200 presenting collaborators and 3,000 artists in 28 countries; the 150-plus events in the United States reached all 50 states. Performances took place in theaters and schools, parks and community centers, churches and public squares and even kayaks.

Where these plays didn’t happen, excepting a lone evening during which four of them were read at Appleton’s Lawrence University in October 2019?

Wisconsin.

If theater companies are truly intent on building back better, how can they afford to ignore such materials, which not only highlight our climate change crisis but also shed light on the intersection between climate change and environmental racism?

CCTA plays might be offered as an amuse-bouche before a main production. Or, as was the case at Lawrence in 2019, several of the plays might be grouped together for an evening of readings. Perhaps they could be performed by high school, college, or community theater makers, thereby furthering every professional theater’s current focus on reaching out to the surrounding community.

Or, perhaps, Wisconsin theater companies might actually consider full productions of one or more of the growing body of distinguished plays about climate change that theater companies here have largely ignored.

It’s frankly astounding to me that so many excellent recent plays about the world’s greatest existential crisis – including Caryl Churchill’s Escaped Alone (2016), Lucy Kirkwood’s The Children (2016) and Duncan Macmillan’s Lungs (2011), to choose just three of the more glaring omissions – remain either entirely unproduced or under produced by Wisconsin’s professional theaters.

Not surprisingly, the problem extends beyond Wisconsin. A survey of 2019-20 world premieres among the 75 member companies comprising the League of Resident Theatres and the 32 core member companies of the National New Play Network concluded that not a single one of those premieres focused on the environment or climate change.

We’re fiddling, while the oceans rise and the forests burn.

I’m not suggesting that every play we see should be about deforestation or species extinction.

But consistent with the American theater community’s long overdue focus on systemic racism, I am proposing that we pay better, much closer attention to the world around us. When all the world’s ablaze, we must make all the world our stage.

While there’s still time. While we still can.

A Milwaukee-based writer and dramaturg, Mike Fischer is a member of the Advisory Company of Artists for Forward Theater Company in Madison and Third Avenue Playhouse in Sturgeon Bay. On behalf of Forward, he co-hosts a Want more arts stories like these? bimonthly podcast and writes a weekly visual arts guide. You can reach him CLICK HERE directly at mjfischer1985@gmail.com. TO SUBSCRIBE for FREE to ArtsScene Magazine!

SCRAP METAL MERMAID SCULPTURE

By Trove Arts A metal Feejee mermaid sideshow sculpture made from Milwaukee metal - Pabst Brewery electrical cables, PBR bottle caps and cans. Click Here to visit their website! Click on the video to see how this piece was made of all recycled materials!

Taking better care of yourself starts with finding the best doctors

to take care of you.

When it comes to healthcare, you shouldn’t settle for anything less than the perfect fit. You need physicians who are engaged. Who listen. Who spend time with you. We want to make a difference in your life, and the lives of your family.

INTERNAL MEDICINE

Kathleen Baugrud, M.D. John Betz, M.D. Matthew Connolly, M.D. Kevin DiNapoli, M.D. Deidre Faust, M.D. Scott Jorgensen, M.D. Unchu Ko, M.D. David Lucke, M.D.

Rachel Oosterbaan, M.D. John Sanidas, M.D. Abraham Varghese, M.D. James Volberding, M.D.

PULMONARY

Dima Adl, M.D. Jay Balachandran, M.D. Burak Gurses, M.D.

UROLOGY

Kevin Gee, M.D. Christopher Kearns, M.D. Peter Slocum, M.D.

ENDOCRINOLOGY

Amy DeGueme, M.D. Elaine Drobny, M.D. Antoni Gofron, M.D. Brent Jones, M.D. Kawaljeet Kaur, M.D.

GASTROENTEROLOGY

MILWAUKEE • MEQUON MadisonMedical.com | 414.272.8950

SURGERY

Daniel Butz, M.D. Richard Cattey, M.D. Jasna Coralic, M.D. Alysandra Lal, M.D. Joseph Regan, M.D. Craig Siverhus, M.D.

ALLERGY & IMMUNOLOGY

Anne Lent, M.D. Kristin Schroederus, M.D.

MOHS SURGERY

Carmen Balding, M.D. Manish Gharia, M.D. Camile Hexsel, M.D.

OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Jonathan Berkoff, M.D. Patricia Dolhun, M.D. Katya Frantskevich, M.D. Shireen Jayne, D.O. Jennifer Moralez, M.D.

DERMATOLOGY

Amanda Cooper, M.D. Tracy Donahue, M.D. Valerie Lyon, M.D. Jack Maloney, M.D. Jason Rosenberg, M.D. Debra Scarlett, M.D. Thorsteinn Skulason, M.D. Heather Wells, M.D.

COMPREHENSIVE EYE CARE

Visit MadisonMedical.com to learn more about our doctors and their specialties.