38 minute read

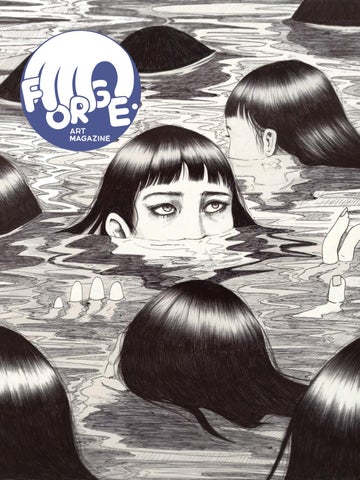

Richie Pope

by MATTHEW JAMES-WILSON

His current conviction and creative vision gradually developed out of years of experimentation, humility, and determination. Since graduating Virginia Commonwealth University’s esteemed illustration department, Richie has gone on to create vibrant and inventive illustrations for clients like the New York Times, the New Yorker, and TIME. His comics have the unique quality of being both deeply personal and inexplicably universal. Richie often draws from his own experiences to convey stories and perspectives that most readers can relate to. His most recent self-published work, That Box We Sit On, was awarded an Ignatz for “Outstanding Artist” this fall, and during his acceptance speech he reflected on the changes he hopes to be a part of within the current comics landscape.

I first came across Richie’s work through his groundbreaking short story comic Fatherson which was published as part of Youth in Decline’s Frontier series. I was totally enamored by the delicate wisdom in his writing, and his ability to find humor in complex subjects like fatherhood and race while still not sugar coating either. His masterful use of color and abstraction distinguish him even among some of the most well known illustrators working today, and his talent for visual problem solving is remarkable. Beyond that, Richie is also an artist who just makes me feel less alone in the world, and his presence in his art communities has made some many people feel more welcome. In November I had lunch with Richie while we were both in New York for Comic Arts Brooklyn and together we recorded the following conversation over Nepalese food in Ridgewood, Queens.

Where are you from and where do you live currently?

I’m originally from New Port Beach, Virginia. I went to art school in Richmond, Virginia, which is more inland. Now I live in Dallas, Texas.

What was New Port Beach like when you were growing up there?

It’s a costal city and it’s sort of like a military city too. A lot of military families live there because there’s a base there. The downtown is a shipyard. Growing up there was pretty cool because it was actually pretty diverse when I was a kid. I had that shit in school where in the hallway there was a “kids around the world!” poster where there were a bunch of kids holding hands. So that seemed really normal to me—black kids and white kids hanging out wasn’t a weird thing. I wasn’t too inland in Virginia, so I feel like my Virginia upbringing was a little different from other people in Virginia.

What was the role of art and comics in your life at the time? Were you encouraged to make art as a child?

Yeah, my mom was really encouraging all the time. She would put my drawings up on the fridge—all of the cliché shit. I would make these comics when I was 12 or 11. I didn’t know what zine culture was, but I’d be like, “I need blank paper.” and she’d give it to me and I’d improvise comics. I’d put a little logo for a fake company that I came up with on them, haha. She still has them in a shoe box somewhere. I was making them when I was in middle school before I knew what “DIY” was or anything. I just didn’t know—I was just a black kid living in city. Even before that my mom was bringing back newspaper comics. It was a lot of Sunday paper stuff, like Peanuts. She use to work at the local newspaper, so she would bring one back and I’d be like, “Oh, can I look at the comics?” and she’d give me the whole section. So I’d read Peanuts, Garfield, those weird sort of out-of-context detective stories that are always on going but you don’t know what the fuck is going on in them, haha. There were some that were local—you could always tell because they were just a little off, haha.

Around the time I was in high school was when Boondocks appeared in the Daily Press, which was the local paper in the 757 area. I think Aaron McGrunder went to a Maryland School, so I know he’s probably been around Virginia. That was really the first time I ever saw something with two black kids talking to each other. There’s gotta be a Black Bechdel test, haha. It was also the first time I had seen the n-word in a comic. I was like, “Whoa, they’re talking like me and my friends! What the hell.” It was really cool seeing that, because that inspired me to think, Oh well if he can make comics for black kids, then I can make comics for black kids. He also got a lot of hate mail which was great. A lot of local Virginia people would be like, “I’ve been a long fan of the Daily Press, and this is a race-baiting comic!”

The cape comics where something I’d get only every now and then, because we’d have to go to a comic shop to get them. There weren’t any that were super close. I kind of lived in the hood, so there weren’t really comic shops. Everything came from the paper or stuff I’d see on TV.

Was there any TV that you were watching that helped shape the way you wanted to write or make art?

I watched way too much TV. When I was a kid Sailor Moon would come on in the mornings at 6 am. They put it at a time where kids would watch it before school, so I would just watch Sailor Moon everyday. I was watching Dragon Ball Z when I was in high school. I was watching a good portion of Toonami and Adult Swim anime. Shit like Paranoia Agent and all of the weird classic stuff. But I also watched a lot of action movies. It’s not really noticeable in my work at a glance, but a lot of shit like Bloodsport, Kickboxer, all the Die Hard films, anything with Sam Jackson in it—all of that influenced me. I have a soft spot for it, so I kind of want to do very sincere action thing eventually. There were a lot of weird movies that would come on TV, and I would constantly watch weird shit. Star Trek was a big one too. I was a pretty big kid treky because my sister got me into it. I would be on the bottom bunk bed and she would be watching Star Trek, so I would turn around and watch it. She watched wrestling too so I would watch that too. So all of her weird nerd shit passed down to me. She’s not a nerd anymore, but she forged me into one.

How did you decide you wanted to study art in college and attend Virginia Commonwealth University? What work were you making on your own in high school that led to that?

It’s kind of wild actually. I almost didn’t want to become an artist anymore while I was in middle school. In middle school I had a really bad art teacher and there was this weird middle school drama where I was always clashing with them and they were mean to me. I was like 12 or something and I was like, “I don’t want to draw anymore.” So I swore off art classes. Then when I was in high school my friend was like, “I heard the teacher at the high school is actually really good.” so I was like, “I think I’ll try it again.” and he became my favorite art teacher. He went to SCAD, but he wanted to go to VCU. So I was thinking about going to SCAD and moving to Georgia, but he was like, “Think about it, but VCU is in state tuition, so you won’t have to owe a lot of money back.” So I was like, “Alright, I’ll do that.”

I didn’t really know about the whole illustration industry or the kind of jobs people do, so I was just going to art school because I wanted to be an artist. In high school in general my art was like “I’m an edgy teen.” I remember drawing anarchy symbols on the wall and shit. I didn’t know what it actually meant. I was feeling stuff like, I’m living in the shadow of my father, and stuff like that. It’s weird, it was like teen precursors to Fatherson. But I just wanted to be a general artist. I was into Andy Warhol and all of The Factory shit. Then when I got to school I was like, maybe I want to be an animator. Then I realized I was too lazy… I was like, “…That’s a lot of drawings. You have to draw 24 pictures per second?” haha. But I knew I did like to draw, so I decided to do illustration. But there were a lot of false starts with things that didn’t happen.

What was your experience like at VCU? What was their illustration program like while you were going there?

The program was pretty cool. I had one teacher named Sterling Hundley—if you don’t know about him, at the height of his career he was the most awarded illustrator. Before James Jean it was Sterling. He was winning medals every year, getting into annuals, and he was my first illustration teacher. So I really followed him and was like, “I want to do what he does.” Before I actually met him I saw his pieces and he drew a series of different musicians. He drew R. Kelly, and Dr. Dre, and Stevie Wonder, so I was like, “Yo, this black guy is really great!” because I just assumed he was a black dude. Then he walked into class and he was a normal white guy in cargo shorts. I don’t think I’ve ever told him that I thought he was black before I first met him, haha. But his work is what got me into wanting to do it. He became like a mentor in school.

The actual program was pretty decent. I was doing a lot of figure drawing. Before I didn’t really keep a sketchbook and I wasn’t doing a lot of observational shit. But those types of programs really get you in the mode of drawing things you see. I did so many sketch books through out those four years. I would constantly just wake up and be like, “Uh, let me just draw this cup.” Just the act of moving your hand around and making marks really helped.

How did your drawing practice change once you were in college?

I think it changed in school because I had real assignments. In high school I was experimenting more. I was doing collages and things that would come of off the page. In college it was a lot more specific. It was like, “Alright here is figure drawing homework, here’s an assignment where you have to design a poster for a play using this medium…” I hated actually making all of that stuff, and I felt like, This sucks! I’m not good enough yet. I didn’t feel like I was a star in the department. But at the same time I was figuring out what I wanted to do digitally. Then I started working with gauche and graphite and stuff. I kind of appreciated the assignments after the fact, but when you’re a student and you’re constantly pushed to do so many things, you realize I just want to do this one thing. Sometime it seems like they’re trying to control too much, but I definitely think teachers know what they’re doing. At the end of the day, I think your mind is just not ready to be challenged. You as a student just want to be like, “I just want to do my thing.”

What was it like graduating after four years? Were you nervous about entering into the “illustration industry” after that?

Yeah, I was super nervous. I got that shock that no one prepares you for which comes the day after graduation when you’re suddenly not a student… and you don’t know what to do, haha. I was like, “Well I’m going to get up and go get lunch on campus still?” It took a while to break that weird in between. I was actually a little depressed for a while. I had to immediately adapt to a post school culture. I didn’t have a lot of money, but I was still making work. I was picking up painting and tried to do portraits. The first ones kind of sucked, but then I got better. Then I got a caricature job because I was like, “I need some money.” and that’s how I met some of my artist friends. But I was just constantly trying to make work. I think I still hadn’t really figured out how I wanted to work yet. The first two years after school I was kind of just wavering. I worked at an art store after the caricature job, and that was cool because I got to play around with materials. That’s really when I started messing with gauche. I used that and I got a carpenter pencil and really just started experimenting with that. That’s when I started my tumblr. I was like “Hi, I’m Richie Pope. This is my first post. Enjoy my art please.” hahaha. My goal was to just make art as if I were my own art director. So I would just go to magazines, pick an article—I tried to choose different topics like business and politics and life style—and I would make pieces art directing myself. I was just like, let me make a bunch of those, put them up, and see what happens. It took a couple years, but finally I started to get into my actual work.

It seems like you really graduated at that turning point where people began relying more on internet presence than hiring agents or sending out mailers. What was your impression of the other communities making work on the internet at the time? How did that affect your attitude about doing illustration?

Yeah! It was weird. When I was in school my teachers had agents. Then it was sort of on that down turn where people were like, “You don’t really need one.” So I was a little more quasi-punk where I just thought, We don’t need anyone! We can just do it ourselves! So Tumblrs were big and BlogSpots were big. I remember James Jean’s blog was huge. Every major artist had a big blog. So I think after seeing that I was like, Alright, let me get one of those and that should at least put my stuff out there. It definitely kept me going, I think. You can get too insular, you know?

How did you start honing your digital image making skills? You’ve always been one of my favorite illustrators who works digitally because you make the work still feel very human and spontaneous. How long did it take for you to start making work in the style that you make work now?

It was a lot of trial and error. A lot of the work was based on sketchbook stuff, and I was using a lot of graphite and gauche. Everything I was trying to do digitally was still like, “Let me get a grainy pencil that’s sort of randomized, and let me get a brush that’s just a little watery.” Even my first couple pieces in that style got the reaction of, “Oh is that done traditionally?” and I was still scanning in lines.

At a certain point I was just like, “Okay, why don’t I just do it all digitally, because I’m really bad at keeping track of my physical work.” I really don’t care… haha. I have computer paper drawings, and I just throw them away. It doesn’t bother me really to just toss them. So I just started doing them digitally. A lot of the stuff at the time—even the digital work—was really textural, and it seemed like you needed texture packs and stuff. At a certain point I was like, “This feels kind of hokey. I’m just drawing and then taking a texture and slapping it on. Does the drawing actually need it?” So I just got obsessed with the idea of using a digital brush and just seeing what I could do with that brush. I just wanted to focus on that first, rather than thinking about all of the bells and whistles.

Now I do a lot of my drawings with a round pencil and I’ll shake the lines a little bit. So now I’m doing stuff where I’m still trying to purposely be inaccurate when I’m drawing. At first I was doing it more purposefully, but now it’s just like second nature. I’ll see a line and think, All these lines are too straight. I don’t want to draw too fast. I don’t want it to look like swooshes, I want it to look a little more craggy.

I think that all ties back to the carpenter pencil stuff and some of that stuff that you can’t really control. I still try to hack the way I do digital work to make it a little bit more random, and I think that helps with making it not look so stiff. Even when I’m doing flat coloring, I try to make the edges feel craggy or rough.

Where there any illustrators at the time who were influential to your approach? Was there anyone who you met who left a big impression on you?

Well Sterling was definitely a big one, because he was such a influential teacher locally. If you’re a student of his, you’re probably going to rip him off at least once. You’ll find those pieces and be like, “Oh, those are the rip-off pieces.” When I was in school the kind of young stars were Jillian Tamaki, and Sam Weber, and Josh Cochran. The fact that Josh was using pencil—that was a pretty big influence to be honest. He wasn’t trying to hide that they were drawings, which I really liked. He’s still a pretty big influence, but now we know each other. Everything really came after. Later on I got into Harlem Renaissance illustrators. I remember being like, “Damn, why didn’t I learn this is college?” There are so many of them and they’re all so talented. I think my favorite artist from then is probably Jacob Lawrence, just from the way he did his blocky sort of figures.

What were some of your earliest illustration jobs?

Well my earliest job was actually a Sterling rip-off piece, haha. It was during my senior year, and I was shocked because I got a job and I hadn’t even finished school yet. I thought, Wow, I’m a superstar already! but it was a false start, because I didn’t get another job for a few years after that, haha. But I got the job, and it was for this writer. So I did this typical Sterling rip-off of a guy at a table with a pen or something. They liked it, but when I went to go invoice them—I had never done one before—so on it I said “Invoice for Richie Pope Illustration.” But the thing with checks is, if you put something like “Richie Pope Illustration” that has to be registered as a company. So I got my check, I went to go deposit it, and the bank teller was like, “Can I see your business ID or something?” and I was like, “Uh no… I’m Richie Pope…” but she was like, “You’re not Richie Pope Illustration. That’s a company name.” and then I was “Oh, I don’t have that company.” so she was “Okay. Well then we can’t cash this check.” So then I had to awkwardly ask my art director if they could make a new check out to my name. That was my first “job” job, and then it was a couple more years before I did something for ESPN I think. Then I finally got a job through Irene Gallo at Tor.com and I started doing book cover stuff. Those were really well paying jobs, and then it kind of became a regular thing, so I started doing an illustration almost every month. That allowed me to explore different technical stuff digitally, and those jobs were probably the last time I did really textural stuff. I think I started to leave it behind there. It’s weird because, I think the sci-fi fantasy scene really loved that kind of style. But as I leaned more into comics, my work started to get more cartoony. Now I do a lot of young adult book covers and publishers pick up more on what I’m doing. Even a subtle switch up of what I’m doing can attract totally different people.

What tactics for getting your work out there did you learn in school? Which of those tactics were helpful, and what tactics did you have to figure out on your own?

Emailing was actually pretty helpful. I sent mailers—I think those did pretty well. I think I definitely sent New Yorker ones to the New York Times and vice-versa, haha. I would just be like, “Oh shit, that’s the wrong address and the wrong employee.” I think that might have worked, but I think emailing definitely worked better. One time an art director hit me up and was like “Hey Richie! I still have your email from a year ago, and I was just looking for the right project for you.” So the fact that people keep track of that shit is really cool. I know if it’s a really good email they’ll just pin it for a while and keep it on the back burner. That and the work itself kind of promotes you when you post it. I haven’t actually sent any type of mailer in a while. But the work itself starts to spread. If you work with one art director—like at the New York Times for instance—they’ll talk to another art director and be like, “Oh, I worked with Richie Pope recently.” and the other one will be like, “Oh, let me see his work!” and then maybe they’ll hire you. Once you’re in the bigger publications you can sort of spread out and work with a bunch of people.

There are all of their organic ways to do it that aren’t like, “If you send this many postcards you’ll get this much feedback.” If you just send a template email where you clearly just switched out the name like, “Hello _____, I love your publication. We should work together.” people can tell, haha. I would always just take the time to write something. I would have a general idea of what I would want to say, and to not sounds stupid I would start with a base template for an email. But for each person I would change everything and reflect on what I actually liked about the publication. I wasn’t lying either—the last thing you want is to talk about the publication and lie and then they talk to you about some shit that you don’t know anything about, haha.

In your work you have this incredible talent for incorporating both highly rendered images with stylized abstraction. You’re always really great at placing a recognizable and detailed portrait in really playful and inventive compositions. How do you find harmony with both techniques in your illustrations?

I feel like, influence-wise, that maybe came from Ren and Stimpy and weird cartoony style that incorporates the extreme close up. They use to feel a little bit separate, but now I treat my portraiture as more realistic cartooning. There’s a piece I recently did that actually came out today in the New Yorker. I kind of sketched it out first loosely, and then I rendered it, then I turned that layer down and tried to simplify it. So for likenesses especially, I try to get super accurate and then I try to just simplify it. Sometimes it’s like drawing the nose and then moving the nose up a little bit. It’s sort of the same process when I’m just generally cartooning where I’m just trying to get the lines right. But it’s a little bit more about really fine tuning the shit. With cartooning it’s a little more like, “This one is accurate, this one is not. It’s fine.” but with portraits, it’s so front and center that it must be recognizable.

Who have been some of your favorite clients to work for over the past few years?

I worked with Anshuman (Iddamsetty) who was at Hazlitt. He’s really fucking cool, because he’s one of the only art directors who get’s hyped off of my work. I would send him stuff and he would be like, “Oh man Richie, you did it!!! This is good, this is a good one!” I found out it wasn’t just me, he was generally just excited about work. So he was one of my favorites to work with. I never thought he was going to be disappointed. Irene Gallo is a big one because she put me on first. She was one of the first people who was trying to see what I was doing and gave me big book cover jobs. Pretty much everyone at the New York Times is good. They’re all super chill and they all know each other. For a long time I worked with Deanna Donegan, and now she’s at the New York Times. When she was at the New Yorker we did the New Yorker Radio Hour podcast. At first they worked with different artists, and I just did one. Then she asked me to do another one. Then I think something happened where I was just always available, so she would say “Hey are you free?” and I would be like “Yeah!” We never said it was going to be a long running thing that I was going to do, but I think it just happened that way. So I was doing them every week for about half a year. They switched it up because she left, but those were really good consistent ones. As an art director she’s just really helpful and respectful of my time—she knew when to push it and when to not demand too much.

How have you balanced doing both professional and personal work as you’ve started to get hired more. What role does each type of work play in your creative life?

It’s been kind of a struggle honestly, just because the freelancers life is often not being able to separate your time. It’s hard to say “This is my free time and this is my work time.” especially since I work from home. So sometimes I have trouble separating those, so I’m just constantly on call. If I get any email I’m like, “Oh! Did I miss a due date?!” But for me, those jobs are like, “Alright, let me pay rent.” but also “Let me put content that I want to see.” I want to feel responsible with the shit I put in there. The side stuff always involves getting into a completely different mode. That’s the stuff were I go to the coffee shop for a little bit and I kind of let loose. I try to watch stuff for inspiration. I just have more time in general so I’m completely shifting gears. The deadlines—they’re usually like show deadlines—but they’re not beholden to anyone else. It’s actually gotten a lot better, in terms of how I separate the time. that’s why I like doing short indie stuff. Some people are like, “Oh, why don’t you write some longer stuff?” but I’m always like, “Yeah, but I like being able to commit to this thing and finishing it rather than having it go on for a long time.”

When did you come up with the idea for Newdini? Was that your first proper self-published comic?

Yeah, that was actually my first self-published comic. The way it came about is completely unglamorous and irresponsible. I was sharing a table with someone who got in to a zine fair and I was like, “I need a book.” I was stressed because I had never made one, and I was like, “I don’t have anything! What am I going to do?” So I thought, I’m just going to improvise a comic. I wrote it like I was an investigative reporter, so I was drawing people and making them up as I went. It was like I was trying to figure out who they were like, Alright, who is this character? What’s their name? Maybe they’re tied to him this way. It was like investigating a crime family and using string to try to find all of the connections—that was me for that project. So I pulled an all nighter and I stayed up and printed it that morning. I was folding it myself, but I printed too many, so my friends were helping me fold them. Some of them were all out of order when I put them together. I looked at it and was like, “Cool, it’s finished!” Then I was like, “…Okay this sucks. They’re going to be disappointed. They’re going to be like ‘This is trash.’” haha. Then people were into it. I brought like 75 or 100 copies and I had like 15 left at the end of my first show. Eleanor Davis came by and got one. I was like, “You’re Eleanor Davis! Why do you want my shitty comic?” But that low barrier of entry and the fact that the last minute thing pushed me to make something made me realize, Okay, maybe I should keep coming back. It was this level of judgement that definitely is not in illustration where, if you just turn in a piece it’s whatever. But yeah, that book was my first experience doing indie comic selling or printing or anything.

As you started doing more comics, how did you approach that work differently from your illustration?

I try to do something different each time. Whether it’s the format, or the way I’m drawing, or the way I’m coloring. It seems like the first couple books were all sort of different, technique-wise. Fatherson was sort of like a weird children’s book things, and Super Itis was more like a traditional comic and the color palette just involved thinking about thanksgiving food. The most recent one I’m doing, the cover has no black on it. It’s just line and really bright grey tones. So with each one I’m approaching it in a way where I’m trying to do something different. I don’t really know if I have “my thing that I do” yet, so I just want to keep playing with it and seeing where it goes. I feel like now I’m in comics college. With illustration I know what I’m doing, but with comics I feel like I’m going back to school a little bit. Even just being at shows I feel very humbled about a lot of stuff.

What have you appreciated about the independent comics community as a whole? What has the community provided for you as an artist that other art communities haven’t?

I think we were talking about it a bit before, but it’s the flattening of distance between people. The people that I look up to who’s work I’ve been following for a couple years—after doing it for a while you just start chilling or saying “hey” whenever we see each other. Especially with the shows themselves, it’s a community that I don’t really get anywhere else, because the thing we do is not really tied as much to making a lot of money. That and the fact that the money people are making goes right back into buying other people’s stuff is great. I’m always adding to my knowledge of what other people are doing—even though I don’t get to read it all of the time because I buy too much shit, haha.

When did Ryan Sands from Youth in Decline first approach you about doing a book for the Frontier series? How did you conceptualize what you wanted to do for that project?

I think it was after my first or second SPX. We just saw each other and talked for a little bit. Then I think a couple days later he emailed me and was like, “Hey! I’m doing another Frontier. Would you like to be in the next round of it?” and I just thought, Yo what the fuck! I was like “I love Frontier! How am I now in it?!” After that I was just thinking about ideas. I wasn’t quite sure what I was going to do yet. Then I hit him with a concept and I think he was really into it. What was cool about him as an editor is that he said he could be as hands on or hands off as I needed him to be, which was good. Really at the end it was more about copy editing and him checking to see if stuff was spelled wrong or anything.

That whole experience was really really good. It was kind of like Newdini where I was working on it up until the last minute. It was also one of those things where, right when I finished it I was like, “Man, I hate this.” haha. Then afterwords I was like, “Ah, it’s pretty good!” Luckily my modes of working are a lot better now. They’re a lot healthier. I think at that time I was just working up to the wire and the experience was really stressful. I didn’t want to deal with the work. But now I kind of control my time a little bit better and I’m more comfortable putting projects to the back burner. So I actually like my work as I’m working, which is good. Like with That Box We Sit On, I actually liked it while I was drawing it. I was just like, “If I don’t have it, then I don’t have it. If I finish it, then I’ll have it for the show.” and that allowed me to step back and actually enjoy the process.

How did you conceptualize the story for Fatherson?

I think it came out of me thinking about my dad, but also thinking about my own anxieties about being a dad potentially. I was getting at the age where I was like, “Man… my friends are becoming dads…” so the idea of what a dad is suppose to be and what a young man is suppose to be started blurring. I was realizing, “Oh okay. You can just be a dad.” I was sort of going back and forth about what was going to be the concept—was it going to be a sci-fi story or more like an infomercial kind of thing—and then the title came as a term for the sort of cyclical nature of a father to son. I also really wanted to do a comic where I could put a bunch of random Virginia black dad references in there. I was like, “I haven’t really seen anyone mention Newports in an indie comic… I’ll put that in there.” haha. I was like “I don’t think I’ve seen a du-rag in an indie comic… I’ll put that in there.” It was very loving too. Some of the things are more critical, like the idea of not taking care of your health and the anxiety of taking care of someone else. It’s weird—I feel like it’s a more complicated grey thing now. When I was younger I was like ”If your dad isn’t around, then they’re just a piece of shit. You have to be around! How could you not?” But now as an adult I understand it’s still shitty, but I see why people run. It’s not like empathy, but it’s more like “Oh, I see how you could end up like that sort of person.” All of those things just got put into that one book and it became a bigger thing than a little joke about a weird pill.

How did it feel to have that work out once it was published? I remember that book really stood out to me when it first came out, and I think it was my first entry into your writing. What reception did you get from readers once it was out?

Once it got out I felt a little bit better about it. I had some distance from it once it was a book, so it felt real. People were really receptive to it. I kind of just thought, Oh it’s a part of Frontier and I’m not as big as the other artists, so if people read it it’s probably just because it’s Frontier. I was still kind of doubtful how much impact it could have on people. Then when people started telling me, “Yeah it’s one of my favorite books that I read this year. “ I was like “What???” haha. People were like, “Yeah it really moved me.” I was doing this residency, and this guy who came to interview me and document my digital work and set up the gallery—he was in his late 30s or early 40s—he had a teenage son, so he was talking about how much Fatherson really hit him. He said it made him think about his own dad, so then we were just talking about that. So then I was like, “Oh wow, I think people really like this.” My connection to it is just making it and putting it in a folder, so I never really get the actual scope of how people react to it. But now it’s actually one of my favorite things that I’ve done. Looking back at it I’m really with some of the stuff I was picking to put in the book. Also, if I become a dad one day, it’s going to be wild to see some of that, haha.

Have you ever felt pigeon-holed or pressure to make certain work because you’re one of the few black American illustrators who is being hired by these big clients in the illustration and editorial world? If that does happen, how do you go about it?

Yeah, we have a joke where every February we’re like, “Oh it’s black history month. Here come the jobs!” haha. It’s like a catch 22 where companies mean well and they’re like “This is the perfect time to hire more black artists!” haha. I mean, it’s cool but, “Can I still get the same amount of jobs every month?” So we joke about that every February. But, I think my thing was getting worried about not getting pigeon holed to draw “black art,” but drawing an idea of what diversity in art means. Sometime it can be less “Draw a real group of people.” but more “Can you make sure this group of people is all of the people.” It can be really good, or it can be like, “There are too many of ____.” At that point it’s like, “Well, now you’re like measuring.” and that can feel like an accidental reverse tokenizing. It’s sort of like, “We want it diverse, we don’t it black.” or something. No one has ever explicitly said that but, if you drew like a city scene that was all black people, they might ask you to change someone to being Asian or Latino. So I think I worry about that a little bit—being pigeon holed in the sense of “We need you for diversity stuff!” But other than that I feel pretty good with the stuff I’m doing.

I think for a lot of black artists it’s hard to tell when you’re being encouraged to make art about being black and when you’re encouraged to make art from a black perspective. How do you navigate that in your own work?

I don’t do a lot of non-fiction, but the fiction that I do is in a way non-fiction. I’m still saying something in the subtext. With Fatherson, I don’t think people see it as “a black people’s comic.” But for me, I always want to have the black guy in it, haha. That sort of Carl Winslow kind of dad type, haha. I wanted to put in the du-rag and the car stuff. With Super Itis— “the itis” is such a black cultural reference. Even with That Box We Sit On, I was really anxious about putting “nigga” in a comic. I was like, “How would I feel if white people read it and they were saying that?” and then I’m like doing the rapper thing of, “Am I okay with this?” But at this point I’m just like, “If they do, whatever. I’m not making this book for a specific group of people. But I do want the people that I grew up with to read a comic and see themselves in it.” For me that’s my most outwardly black comic. I think I fear the idea of being pigeon holed and people putting weird blackness on me, but I want to be able to take my shit and be more malleable with it. I can take it and be more explicitly like “Yo, this comic is about me being depressed about police brutality.” or it can be more in the subtext and informing some sort of a sci-fi story. That feels like a more healthy way to put that into your shit.

What progress have you witnessed take place in the illustration industry while you’ve worked within it? What progress do you still want to see happen?

I’ve seen people be more vocal about things that bother them. There can be somewhat of a generation gap. Even though we have similar values, there can be a gap in stuff like, “What do I call students nowadays. What if I say the wrong thing?” I think there’s also a love for things that may have been subversive for their time that overtime no long seem subversive. There’s a gap between young illustrators who are like, “Whoa, that’s fucked up.” and older illustrators being like, “This was legendary!” So there’s stuff like that that I think we’re still working on sometimes. But I do like the fact that we’re talking about them.

It’s happened on a couple panels. I did the “Stories Matter” panel at a show a couple years ago, and it was pretty much a diversity panel for comics and illustration. The second one I did I hosted, and that one was pretty good. It got pretty lively and people were critiquing the context of pieces in the actual place that I was doing the panel. Some of the questions were a little tense. I appreciated it because it meant that we’re not all on the same page— not that we all have to be—but the fact that we’re talking about it is good. I would actually just like that more. I think, so much of illustration is about our egos and the work we do and the awards. But I’d like for the illustration and comics scene to be a little bit more accessible and down to earth. With illustration, the work is so often for companies, so it’s not going to be devoid of “product.” But if I can find ways to make it look like the stuff I’m doing is also for them in a way, I’m at least siphoning that money to do something.

You brought up a really great point about the disconnect between past and current generations in art. Do you feel like you often have sympathy for both sides of those arguments?

There was an illustration job I did one time where the writer of the piece was writing about the Rockefeller Laws that passed in New York and how they ended up hurting the black community. Even though the black community voted for them. The article was basically saying, “If we want to talk about Black Lives Matter, then we have to talk about our own ideas of what we think about crime.” It was very much like a “Don’t protest if you don’t…” I thought, Man I hate this article. I don’t agree with this shit at all. But it was a job that I had to illustrate. It was the first time I ever talked to the art director and said, “Hey, I don’t agree with this article, and I don’t really like what it’s saying. I don’t want my illustration to support it. Can I do an opposing idea illustration?” and he was like, “…I mean, no. We can’t necessarily run an illustration that is completely jarring with the article. But you can solve the job in a way that has your own take on what he’s saying.” So the piece I ended up doing was this portrait of this old mid-century black silhouette with a suite and a tie, but the face was bars. The whole point I was saying was, “Because we wanted safety, we trusted white supremacy to give us safety, and they turned on us instead.” which is par for the course, haha. So I was fine with that, and the art director was fine with that.

It’s only happened maybe one other time recently where it was like, “You’re asking me not to draw this, but you want to be for this cause, so I’m going to draw it anyway.” and they didn’t stop me, so I was like, “Alright.” At this point now I’m confident enough that, if something were to really bother me, I’m going to say in an email, “This is weird.” and the worst they can do is cancel the job. If I’m not desperate for the money, then it’s whatever. But it’s little things like that.

How do you think artists navigate situations like that when they don’t have the financial stability to easily say no to work? Has that been a difficult situation at different points in your career?

It was more difficult in the past. I could have just said no to that job now, but back then I was like, “No, I need that money. It’s an op-ed, it’s real quick, and I can use the money.” I’m at least in a position where I can be a little bit more selective. I’m still just trying to build and save and all of that stuff. But now I’m in a better place. Really, it’s a financial privilege to say no, so I try to keep that into perspective. If I wasn’t able to say no, how would I react to these jobs? But also, so much of it is juggling your time too. I have to make sure I actually have the time to do the things I say yes to. Some of that I still struggle with at this very moment, haha. I’m like, “Did I take on too much work this month? I guess we’ll see how it goes.”

What was your experience like making your most recent book, That Box We Sit On? What was it like getting an Ignatz for that at SPX?

That book is really fun. I had the concept before I had the title. I was like, “Should I call it The Box We Sit On or That Box We Sit On? I’ll use the second one. There’s no way people will confuse that.” haha. So, so far there’s a lot of confusion around that. I actually designed the characters first. I had this instagram post where I had four panels, and they were the first ones I drew. I started with the beginning and the end, and they were both individually one page. Then in-between I was just improvising. I was like, “What do I want them to talk about? Umm… police brutality… alternate dimensions… weird John Carpenter dogs… all of that sci-fi and horror stuff I use to watch as a kid.” All of the dialog came first and I improvised it like I overheard a conversation. I would write it, then put a bubble around the words, and then was like, “Alright, this is where the people would go.” So, the reason why sometimes they’re big and small was all because of the text—rather than doing the drawings first and determining where I could put the word balloons. It was really fun because it was also about discovering these two characters through ease dropping on these imaginary characters. One would think of an idea, and the other would push back on it. Then at a certain point I was like, Man if I keep this up, then the rhythm gets a little stale. So I thought, Maybe I’ll have an intermission and then the “Aye, you want some sunflower seeds?” part come out and it’s just them quietly enjoying some food. Then it picks up again with the last bit.

That was fun, and it’s the most nostalgic book I’ve done. It reminded me of middle school and high school hang outs. Especially when you’re in Virginia where there isn’t shit to do, you just end up being like, “Let’s just sit on this thing and talk about random shit.” It was cool to draw kids who talked like how I talked when I was a teenager—or when I was 12 when I shouldn’t have, haha. Sometimes it’s awkward to have as shows because, when people get it, they really get it, and because of the cover and the colors, parents will come over with their kids. Then I’m thinking, Oh no… There’s profanity on the first page. The kid will flip through it, and I won’t stop them. But the parents will be like, “Oh, what’s this?” and they’ll see it and go “Oh, this isn’t for kids honey.” haha. Sometimes they’re like, “Oh this is really good. I thought it was for kids, but I’ll buy it for myself.” But sometimes people just don’t care. It’s been cool to see the different reactions. I made this lady cry one time. She was like, “It’s so important what you’re doing!” and I was like, “Oh thanks! I’m just making a book, but okay.”

Then the Ignatz stuff—I was just not prepared for that. I saw the other nominees and I just assumed that I was going to lose. But I thought, Let me just go to this thing. But then at that dinner before, I was like, But if I do win, I won’t have shit to say… So I took out my phone and started jotting down notes. That whole dinner we had dim sum, and while everyone was enjoying their food I was anxious. The group picture we took at the end—I was not smiling, haha. We were going right from there to the Ignatz. We got in and we were in that third row. We were sitting next to Carta Monir, Xia Gordon, and some other people. Then it ended up that Ben Passmore was doing the category and I was like, Awe damn, now if I don’t win I have to talk to Ben and be like “I tried!” haha. His introduction speech was really good, and I remember when he was reading the category he said my name and gave a little “Woo!” afterwords. Then he said “You already know who I voted for.” haha. Then when he read the winner is was funny because he was like, “And the winner is… Oh shit! Richie Pope!!!” Then that part was a blur and I was like as zombie and got up and hugged my friend and walked around while people were like “Yay Richie!” I got up on stage and he crept real low for a dap, which might have been the first dap on that stage, haha. Then I gave the speech. I was kind of anxious because I hoped I wasn’t trying too hard and I was just being super self critical of what I was saying. My mom couldn’t make it, but she’s been supportive my whole life, so I hope I can show her the audio or video soon. But the thing that I think really resonated with people during what I said was, “I made the book for people I grew up with. Hopefully these shows will open up to the point where people from where I’m from can go to these shows and feel more comfortable going to them and tabling. I want to see hood dudes making hood dude comics.” I said something about wanting to have them in the same room and have them line these walls and be in these chairs. Then everyone started clapping and I was like, “Cool, glad ya’ll agree.” haha. So that was really good, and all of the reactions past that were really good. The Ignatz is now sitting on my desk. It’s like a paper weight at this point, haha.

What are you working on at the moment that you can talk about?

I’m working on a mini comic called My Side of the Bed is Sinking. It’s inspired by the fact that, at home, my side of the bed is sinking—manly because I sleep all weird. It’s kind of about taking in too much bad news as a black person. The weight of everything makes it so that even sitting in your bed is not comfortable. It’s the complete opposite mood as That Box, and it’s serious with some dark humor in it. I’m also hopefully going to drop a Patreon soon, so that I can get some experimental color comics out there. That would just be something I would have in the background. That’s pretty much what’s coming up.

What do you feel like you still struggle with as an artist? What hurdles do you still see in front of you?

Completing a project and not being anxious about how it’s going to be perceived. I have a lot of in-progress comics and comics where I’m like, “That’s a good idea!” but I put it off to the side. I have a folder of unfinished comics. So the goal is to just finish them. So that’s what I’m trying to get a little bit better at. I also don’t want to be too critical of myself as I’m working. When you start cartooning you can be like, “Oh someone does what I’m doing so much better than how I’m doing it.” so I just have to get those voices out of my head. You should just draw because it’s fun to do it.

Are there any projects you’d like to work on that you just don’t have the time or resources to do at the moment?

I’d love to art direct or do design for an animation. Characters, backgrounds, props—something like that would be cool. I did it once for an Ohio lottery commercial, where I designed the characters and then they animated them and 3D printed them. They looked just like my drawings. I’d love to do a multi-series comic that’s recurring and full color. Pretty much anything that involves color that I can’t afford to do myself would be great, haha.