8 minute read

HEROES WORK HERE

The words “Heroes Work Here” stood defiant in the crisp October air outside Salina Regional Hospital. It’s a silent reminder to passersby of the selfsacrifice of the doctors, nurses and staff serving and protecting their community and state from the novel coronavirus.

Just through the doors, visitors checked in, one at a time, as each one was screened for high temperatures, flu-like symptoms and their recent travel history – all extra steps of care and precaution that would have been unimaginable a year ago. Waiting patiently in the strikingly empty lobby was Dr. Jeremiah Ostmeyer, one of the homegrown heroes fighting the COVID-19 pandemic in Kansas.

Despite the burden of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and distancing protocols, it was easy to feel the warmth and compassion with which Ostmeyer greeted everyone in the hallway on his way to the Emergency Care Division – “Ground Zero” in the effort to halt the spread of the virus in central Kansas.

“We get to be the first 15 minutes of every specialty,” Ostmeyer said, with excitement in his eyes. “We get to touch each person first and we have to know a little about everything. It’s that action and uncertainty that I love about emergency medicine.”

As an emergency medicine provider, Ostmeyer faces a unique challenge. Unlike a primary care physician, he doesn’t have the context and understanding of a patient’s relationships, stressors, history and health. Often rural primary care providers get to know a patient for decades and sometimes treat multiple generations in the same family. Ostmeyer and his team have mere minutes to assess a patient’s status and make the best decisions possible for his or her emergency care. This year, the challenge was made even more remarkable by the unknown and sometimes utterly invisible presence of COVID-19.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Kansas has 105 rural hospitals that serve more than 900,000 residents. These critical healthcare systems are connected to supporting hospitals, including Salina Regional Health Center, through the State Designated Rural Health Network Systems.

These hospitals are essential for overall physical, social and mental health, disease prevention, timely diagnosis and treatment of illness, preventable death and overall quality of life in rural communities. Hospitals and healthcare systems in Kansas provide approximately 93,048 wellpaying jobs and support the creation of an additional 84,413 jobs in other businesses and industries, according to the Foundation of Health Care in Kansas 2019 report.

While rural hospitals and healthcare facilities are essential to the viability of rural communities, in Kansas and throughout the nation, these organizations have struggled

over the past decade due to declining patient numbers and rising costs.

“It’s an unprecedented year in healthcare and there’s a palpable layer of stress in everyone who touches these patients,” Ostmeyer said. “Each patient requires extra time, extra equipment, and there are additional precautions for every exam. This burdens an already taxed healthcare system.”

The first case of the novel coronavirus recorded in the U.S. was Jan. 21, 2020, in Washington state, and the virus wouldn’t reach Kansas until March 7 in Johnson County. Hospitals were forced to step back and re-evaluate all facets of public healthcare as they prepared for the uncertainties of a global pandemic.

“We’re all interconnected and looking out for each other in many ways and the conversations generated as we worked to face the coronavirus together have been a good thing,” Ostmeyer said. “All the meetings and discussions and prep-work forced us to work with colleagues we normally wouldn’t. It brought about collaboration, and we embraced it for the greater good.”

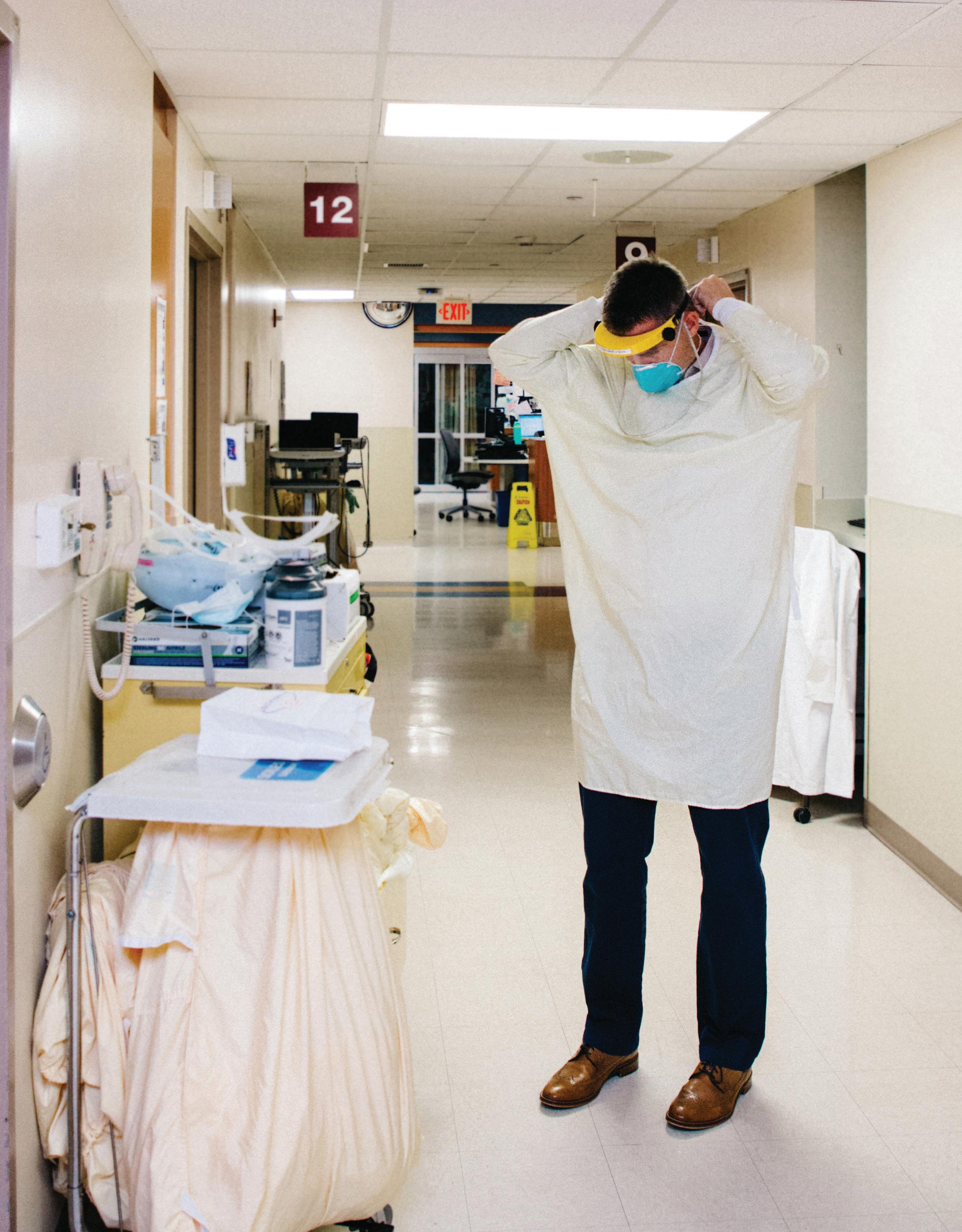

Outside the disinfected and sterile emergency rooms, Ostmeyer demonstrated the extra precautions taken by his team in the ER to protect doctors, nurses, staff and patients from the potential spread of COVID-19. He pulled on additional layers of personal protective equipment (PPE), including an extra gown, N-95 mask, face shield and gloves, applying hand sanitizer between each step. These are just a few of the new health and safety protocols that have proven critical in preventing and minimizing the spread of COVID-19. Each layer of protection does, however, cost priceless minutes for healthcare workers dealing with emergency situations when every second counts.

The addition of masks and gowns also complicates the shared understanding of body language and nonverbal communication often used to reassure patients in stressful situations. Something as simple as a comforting smile is hard to share behind a mask and face shield. Still, Ostmeyer and his team find the courage to step up to each challenge and in those moments of crisis, hold their patient’s hand reassuringly.

“I’m proud of how we handle it,” Ostmeyer said. “The fight’s not over, but we continue to prepare and adapt and change. The worldwide pandemic set us all back and forced us to reassess everything..”

Ostmeyer began his healthcare career working as a CNA in the Gove County Medical Center in Quinter, choosing one of the few available jobs in the small town for youth interested in the sciences. This early healthcare experience led to a job shadowing opportunity and laid the foundation for what would become his passion for emergency medicine.

He went on to attend Kansas Wesleyan University to play basketball. Soon, however, he realized that he was ready to commit his focus to his future in medicine. He transferred to Fort Hays State and completed a Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry.

“Hays is the economic and cultural center of western Kansas,” Ostmeyer said. “I was always drawn to Hays, and it was an easy decision to attend FHSU once I knew I was going to focus on grades and my career.”

Ostmeyer credits his experience at FHSU in the “science hall” and Forsyth Library for his readiness to take on medical school at the University of Kansas and a later clinical experience in South Carolina.

“I love where I graduated from and encourage students interested in science or pre-med to look at FHSU,” Ostmeyer said. “I’m proud of what we (FHSU Tigers) are doing out there. My degree was as strong as anyone’s and I probably had more personal attention, smaller class sizes and paid less tuition. Some places talk about those benefits, but at Fort Hays State, a quality degree and affordable tuition are just facts.”

After completing medical school, residency, and practicing for a while outside of Kansas, Ostmeyer and his wife, Melissa, found their way home to Salina, where he specializes in emergency medicine and serves as the director of Salina Regional’s Stroke program.

“We love being in central Kansas,” Ostmeyer said. “Every day, I meet people who have a tie either to my hometown of Quinter or Fort Hays State University, and it’s amazing to be so close to where we grew up. It gives me an automatic connection to patients. Since we share similar backgrounds and life experiences, I can better relate to them and that helps me take care of patients.”

Ostmeyer’s humble hometown beginnings are evident in his peaceful and calming presence and the way he embraces the challenging work, long hours, and 24-7 shift demands in emergency medicine – all while juggling a busy home life with his wife and their children. He affectionately calls them the “Three Gs” – Grace, Grant, and Gabby.

“I think this is my calling,” Ostmeyer said. “I picked a specialty I love after working and experiencing the different specialty options, and that’s what I’ll do forever – thankfully.”

The halls of many hospitals and healthcare facilities in Kansas are filled with FHSU graduates like Ostmeyer, working in nursing, radiological technology, ultrasound, pharmacy, mental health and social services. Strong ties to hometown communities are one quality that administrators prize as they look for the right healthcare workers. They want professionals who bring skill and passion to their craft and a devotion to serving in rural America that builds vibrant communities and a great quality of life to the plains of Kansas.

“On a daily basis, you’re reminded of where you’re from,” Ostmeyer said. “Many people drive hundreds of miles to see us. Salina’s a bigger town, but it has that small-town feel. The lessons you learn growing up in western Kansas stick with you and it’s prepared me and really all of us who choose to work in western Kansas for the journey in healthcare and life in general. I wouldn’t trade it.”

It’s impossible to know what will come next as the COVID-19 pandemic seems to move back and forth in waves across the country. While it’s created unimaginable challenges in healthcare, the economy and mental health, it’s essential to look for the silver lining as well.

“The level of PPE may never go away and the increased use of masks and other safety measures,” Ostmeyer said. “But this pandemic has shed light on the importance of public health. It has brought it to the forefront and made it a priority, and that’s a positive.”

The importance of accessible public healthcare in rural communities is now part of a national discussion as the late summer wave of COVID-19 spread through the Midwest. One in three Kansans live in a rural community, and it’s something that Ostmeyer has experienced firsthand, as the first COVID-19 patient he treated had to make the 150-mile journey from Ostmeyer’s hometown.

“It was a strange flood of emotions, seeing the reality of COVID-19 on a small town,” Ostmeyer said. “They knew my parents well, and I see the devastation that this virus brings to all regions. It really hit home. I’m proud to take care of people from my own home and proud of the work FHSU is doing to train students who will do the same.”