6 minute read

Trade & exchange Ensuring the

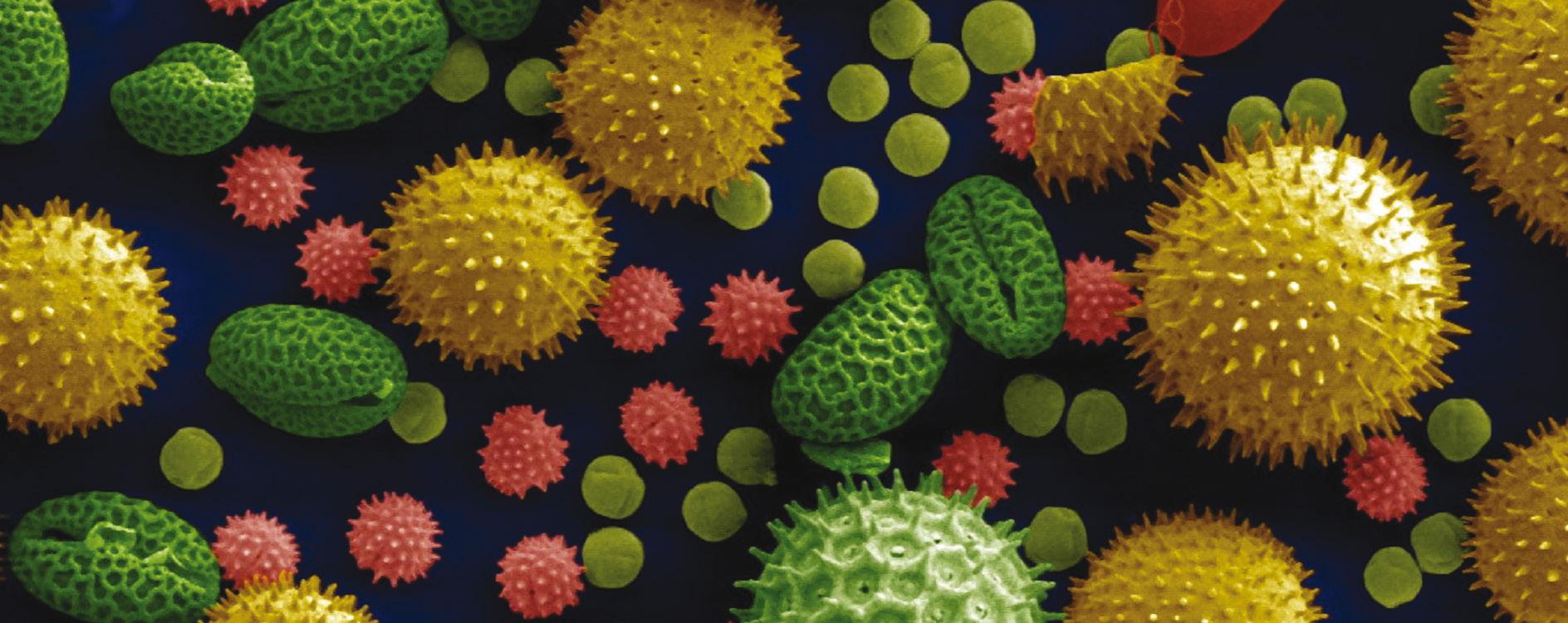

Exchanging pollen is an easy way to move male genetics around the world. Pictured: pollen from a variety of common plants - including sunflower (pink), lily (dark green), primrose (red) and hollyhock (yellow) - magnified under an electron microscope.

THE BOTANICAL WORLD’S TRADE & EXCHANGE

Advertisement

AFTER UNDERTAKING THE FIRST FULL AUDIT OF ITS ENTIRE LIVING COLLECTION, THE GARDENS IS NOW WORKING ON A STRATEGY TO ENSURE THE COLLECTION REMAINS RELEVANT AND SUSTAINABLE. DIRECTOR OF HORTICULTURE AND LIVING COLLECTIONS JOHN SIEMON REPORTS.

Living collections are priceless resources, so you might assume they are managed to specific and strict guidelines. In reality, a 2014 survey of more than 172 botanic gardens found that more than 60% had no formal written curatorial policy. Why does it matter? Because it means those institutions are not optimising outcomes for plant conservation, and more broadly they are limiting the genetic diversity of species held across the globe.

With the first ever audit of the Botanic Gardens’ living collections now almost complete (The Gardens, Spring 2022), we are now redeveloping our own curatorial Policy and Strategy. The aim is to set the overall principles and standards that govern the collection, and by doing so help our staff understand how to care, curate and manage the plants within each botanic estate.

A Policy and Strategy defines how plants (or plant parts) are added to our living collection (or transferred to other botanic gardens). We frequently get offers from the other institutions and even members of the public wishing to donate their prized specimen(s), and requests from scientists and artists for access to our genetic resources. The Policy is our decision-making tool. Whereas the Strategy outlines priorities and required actions to ensure the Trust’s living collections retain their integrity and continue to be developed in a way that ensures the organisation’s ongoing relevance and sustainability. With a clear vision, we can, for instance, address gaps in our living collection and secure the genetic diversity of plant families or species that face pressing or likely future conservation threats.

The exchange of plant material around the globe is nothing new. Some nations’ economies have been built on the trade of plants or the sale of their products – the spice trade is a great example that pre-dates the industrial, mining and tech booms. Botanic gardens have also traded specimens for hundreds of years. However, the quality of collections in some institutions is suboptimal – they might contain lots of species, for instance, but are weak when it comes to representing the genetics left in the wild. There are lots of benchmarks for collection quality, but one that stands out is the provenance of a plant specimen. In the world of art, provenance is critical to validate the story of a painting – it authenticates an artwork. In the botanic world the provenance records tell us specifically where a plant was collected (modern specimens are GPS referenced), who collected it, the altitude, surrounding ecology, soil composition and a suite of other useful pieces of information. This data is all stored in our living collections database and helps inform the cultural management of a specimen in a garden or potted setting. The more specimens in a botanic garden of known provenance the better.*

Unfortunately, it isn’t always easy to obtain provenanced stock or high genetic diversity. Sometimes we just have to take what is available. In some

instances, plants are extinct in the wild and we have little choice but to contribute to conservation initiatives by holding the only genetic diversity available on the planet from one or a handful of individuals in ex situ collections (Sophora toromiro, once widespread on Easter Island, is a good example). Even the iconic Wollemi Pine Wollemia nobilis, is represented by just a hundred or so individuals, and great effort has been made to conserve all of that genetic diversity within our three Botanic Gardens and through global conservation initiatives, while we extensively study the species.

Advances in science, however, now allow us to home in on genetic diversity and ensure we increasingly hold metacollections – specimens that represent the genetic diversity of wild populations and, through our networks, ensure that the maximum genetic diversity is distributed between multiple botanic institutions. In doing so, these metacollections will help to conserve the genetic range of species.

To build, conserve and share genetic diversity, the swapping or purchase of plant material through whole plants or seeds has been, historically, relatively easy. More recently, however, significant enhancements in Australia’s biosecurity and the introduction of global conservation programs aimed at limiting illegal trade of threatened species, such as CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), has made plant exchanges much more difficult. It is far easier to collect and store genetic diversity in the form of seed. Consequently, over the last two decades, the bulk of growth in the Gardens’ living collections has been through a concerted focus on the NSW Seed Bank and the construction of the Australian PlantBank. Ultimately this has resulted in a focus on native, mostly New South Wales flora. In the last decade alone the proportion of NSW threatened flora stored inside PlantBank’s seed vault has risen from approximately 40% to more than 70%.

Nevertheless, our conservation initiatives are much broader than NSW flora. As Marion Whitehead reports in her article in this issue (see page 22), our horticulturists are conserving genetic diversity of significant heritage value as part of global initiatives. To single out but one example, we are actively participating in Botanic Gardens Conservation International’s Global Conservation Consortium for Cycads. The Consortia’s mandate is to ensure that no wild cycad species becomes extinct. Through collaboration with our Science Education and Conservation colleagues, particularly Dr James Clugston, the Horticulture and Living Collections Branch has established a Horticultural Cycad Specialist, Scott Yates. In addition, we are establishing links to exchange Cycadaceae germplasm between botanic institutions – most recently with the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) Kirstenbosch National Botanical Gardens and Montgomery Botanical Center in Florida.

Exploring alternatives to the more traditional exchange of cutting material, whole plants, seeds or plants in tissue culture, we are also branching out and actively discussing the global exchange of pollen. Pollen is an incredibly easy way to move male genetics around the world. On arrival the pollen can be used immediately, if there is a receptive female in the collection, or stored, shortterm, in a low temperature environment (-15 to -20ºC) for perhaps three to five years, depending on the species exchanged. Once seeds are fertilised and mature, they can then be distributed to institutions. Much like zoo breeding programs, knowing who the father and mother are adds significantly to the value and known genetic diversity of global breeding and conservation programs.

Next time you are walking through one of our Botanic Gardens have a think about the journey of that plant, and the many hands it has taken for it to be sourced, transported, grown and nurtured. Botanic gardens are fundamental to the future of plant conservation.

*Across the Botanic Gardens’ estates, the percentage of known wild origin specimens is as follows: Royal Botanic Garden Sydney, 17%; Australian Botanic Garden, 87%; and Blue Mountains Botanic Garden, 40%.