28 minute read

Sylvia Townsend Warner, Lolly Willowes (1926

To celebrate our Book of the Year Award, we asked our followers on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook to name the statuette from our official 2016 seal. After sifting through hundreds of entries, a clear victor emerged: “The Lolly!” "The Lolly" is a tribute to Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner, the very first book ever selected by Book of the Month back in 1926. At the time, BOTM judges voted to decide on monthly selections. Warner's book won by a large margin, even though the author was virtually unknown.

When told that Lolly Willowes had been selected, Warner said: “Any organization daring enough to pick an unknown author would be a valuable asset to contemporary literature.”

Advertisement

bookofthemonth.com

The award of the Femina Vie Heureuse Prize has been made to Miss Radclyffe Hall for her popular novel of Soho, “Adam's Breed,” whose chief character is a waiter. The Femina prize is the only international reciprocal literary prize, and is awarded annually in France and England for the best work of fiction of the year. The final award to the English novel is made by the French Committee, and vice-versa, and both committees are composed of distinguished writers. The three novels which were selected to go up to the French Committee were “Adam's Breed;” “Lolly Willowes,” Miss Sylvia Townsend Warner’s book which raised so much discussion on witchcraft; and Liam O'Flaherty's “The Informer.”

Westminster Gazette, April 7, 1027

Roused at 8.30 by [feminist author, founder of the Women Writers' Suffrage League and legendary literary salon host] Violet Hunt ringing me up to say that the Tait Black prize had gone to Adam’s Breed. I could not feel as annoyed as I might have done because I was so amused by her officious desire to break the bad news; and yet I believe the woman likes me – I’m sure she thinks she does.

Sylvia Townsend Warner, diary, January 7, 1928

33

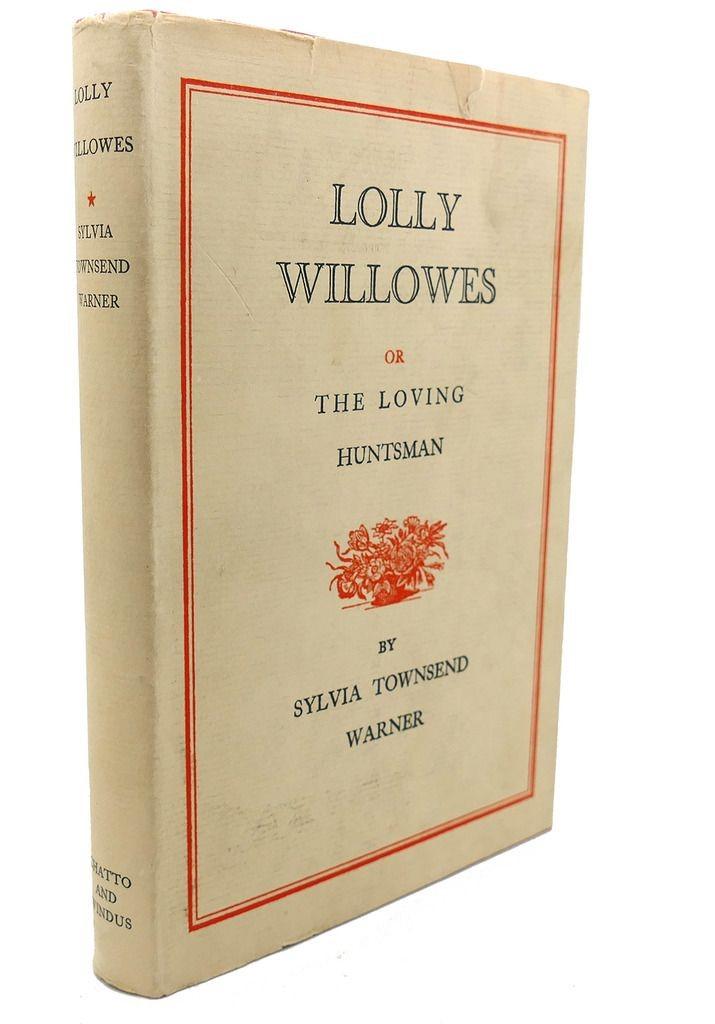

LOLLY WILLOWES, or The Loving

Huntsman. By Sylvia Townsend

Warner, 7s. net. London: Chatto &

Windus.

There is a piquant charm in this quiet chronicle of the life of an old spinster who makes a compact with the Devil, throws her relations to the winds, and asserts her right to stay out all night in the hills. If it be objected that the patient Aunt Lolly whose submissive girlhood, submissive sisterhood, and submissive aunthood are so delicately and with fine persistence pictured by the writer could never develop into such a “monstrosity” as a witch, then the objector is referred to the exquisite old lady herself, who, it is certain, will charm doubt into conviction. For does she not explain everything when she tells the “loving huntsman” of Great Mop village that “one doesn’t become a witch to run round being harmful, or to run round being helpful either, a district visitor on a broomstick? It’s to escape all that – to have a life of one’s own, not an existence doled out to you by others, charitable refuse of their thoughts, so many ounces of stale bread of life a day, the workhouse dietary so scientifically calculated to support life.” Thus is it. Aunt Lolly at last satisfies her inmost cravings to be herself: and may all overweening nieces and nephews, brothers and sisters-inlaw, take warning from this tale of an old spinster who turns. The writer, who has already made herself known by an appealing book of verse, must be congratulated for the delicious fancy and charming irony of the present prose study. It is a book to be read again with increased pleasure.

The Scotsman, February 18, 1926

Miss Sylvia Townsend Warner gives us in LOLLY WILLOWES (Chatto and Windus, 7s. net) not only a first novel of remarkable accomplishment but an object-lesson in the proper way of bringing Satan into modern fiction. She wastes no time in cold philosophical argument, in pumping up horror before and after the event, in giving away the surprise and then making it seem preposterous; instead she prepares the ground with extraordinary subtlety. Laura Willowes is the unmarried daughter of one, sister of another, and aunt of a succeeding generation of a respectable, solid, acquisitive, comfortable middle-class family. Her youth was spent at Lady Place, a house near Yeovil where her father kept the accumulated family furniture and owned the brewery; and when her father died she was unquestioningly taken in by her brother Henry and his wife Caroline to live with them, as the children’s Aunt Lolly, at the house in Apsley Terrace and in the lodgings of the summer holidays. Up to the end of part one nobody could anticipate the development. Laura’s life, all the life of all Aunt Lollys, is set down for us in

34

sentences of deft observation and concealed irony. Miss Warner’s economy of phrase is admirable.

By the time the Willowes family met at breakfast all this activity had disappeared like the tide from the smooth, garnished beach. For the rest of the day it functioned unnoticed. Bells were answered, meals were served, all that appeared was completion. Yet unseen and underground the preparation and demolition of every day went on, like the inward persistent working of a heart and entrails. Sometimes a crash, a banging door, a voice raised, would rend the veil of impersonality. And sometimes a sound of running water at unusual hours and a faint steaming hiss in the upper parts of the house betokened that one of the servants was having a bath.

Nobody would suspect the emergence of a cloven hoof from this quiet realism. Into seventy-three pages Miss Warner compasses twenty years of Laura’s life with Henry and Caroline, she and they and their offspring and their life etched with fine precision. If one is afraid of what is coming, the fear is that nothing is to come but one more study – though an unusually artistic one – of a frustrated woman’s life and death. There have been hints, it is true, but too deep for the unintuitive. At the age of forty-seven, however, the war being over, Laura is more than usually oppressed by the day-dreams that customarily invaded her during autumn in London. Something is waiting for her, she must find a clue, but the clue eludes her. An impulse seizes her in a greengrocer’s shop, it leads to the Chilterns, she buys a map and guide, and calmly startles a family dinner-party by announcing that she is going to Great Mop to live in a cottage. There is a trap for the unwary here, too. The prophetic will exclaim: “Ah, yes, the country, nice old landladies, village worthies, landscape and echoes of Henry Ryecroft; ” and they will be most deservedly confounded, for Miss Warner gives them all these things, and the real surprise on top of them. The crisis comes when nephew Titus comes to Great Mop two, to write a book on Fuseli. In depicting Laura’s dumb anguish at this invasion of her privacy and desecration of her mysterious love for her chosen country, a new note of passion suddenly breaks out. The whole family seems to be advancing upon her once again, and, alone in a solitary field, she invokes the woods for help. The answer is prompt, but we cannot bring ourselves to spoil the delightful surprise prepared for the reader and for Laura on the latter’s return to tea. It must suffice to say that Aunt Lolly realises at length to what all the omens of her life have pointed. She is – we are compelled to divulge it – a witch, a modern witch, one of thousands. Miss Warner works out her idea, witches’ Sabbath, Satan and all, so delicately and tactfully that it never becomes incongruous. Titus is bewitched into the arms of a fiancée, and Laura, having passionately breathed to her mas-

35

ter the hidden truth about witches, remains at Great Mop among her companions. It is a charming story, beautifully told, spare in outline but emotionally rich, on which we congratulate the author.

Times Literary Supplement, February 4, 1926

It is on rare and infrequent occasions that such perfected and deftly fascinating fiction as “Lolly Willowes” swims within the reviewer’s ken. David Garnett, who is remembered as something of a master of wit and shrewd observation, has remarked that this is one of the year’s witty books. However, this novel needs no such introduction. It is the cameo-like realization of the life of a quaint and subtly attractive maiden lady. It recalls the two exquisite novels of Elinor Wylie but “Lolly Willowes,” is closer to the present.

Behind the story of Lolly, but at least once removed, is the inevitable theme of the old order changing. The effect upon her life is less pronounced than usual because of her passive temperament. The Willowes are an old family of landed gentry. Lolly is heir to much accumulated tradition. Her father is a brewer, her mother is a semiinvalid. She is the youngest of the three children. Hence, she grows up in a family where the males of the house were always expected to look after her. In turn, she compared all other men in terms of her father and brothers. With complacency she looked out upon the world from their country seat, Lady Place, in Somerset. It was satisfying to her. . .

The sly and almost subdued comedy of this novel is a strong suggestion of the quality of Jane Austen. The handling of sentiment, family life and much feminine observation has the adroit fitness of the divine Jane. In the handling of the narrative, however, a different method is employed; the straightforward method of the comedy of manners could not capture the inner life of Lolly, and fill so minutely the picture of this involved family life, for all its surface commonplaceness. Beginning in the later Victorian age of gentility, the story is woven into the present restless age, without neglecting or overemphasising the war; the technical skill and compression is of a high order.

At forty-seven Lolly realises that she has had almost no life of her own. Rebellion stirs in her. To the horror of her brothers, to the surprise of their children – now grown-up – she insists upon escaping from them. This whim of hers to leave them and live in the village of Great Mop – population 227 and twelve miles from anywhere – is embarrassing because Henry has invested her money in an enterprise that just at the moment is in decline. Lolly accepts a loss and departs.

36

Once at Great Mop she begins to recapture the serenity that had made her inner life bright at Lady Place. . . .

The family hope for her return. They visit her. She has horror at the thought of returning to Apsley Terrace, London. The idea preys upon her mind and finds outlet in fantasy. Thus, James’s son, now graduated from Oxford, comes to stay with her at Great Mop. Though she thought herself very fond of him, he greatly distresses her. She starts a sprightly flirtation with the Prince of Darkness, in an effort to find that fellowship that her life has lacked. Finally, she is free of her relatives. She could at last do what she liked. . .

In the limitations of its genre, “Lolly Willowes” is an exquisite fantasy of wit. Also, in its mixture of comedy of manners and dark romanticism, there is a viable essence that is enchanting. Lolly, indeed, going her kind, lonely way, is a character that ingratiatingly sets herself in memory. Doubtless, the Willowes, with their traditions and sane conservativeness, will not be forgotten. But, in the last analysis, it is Lolly – who might be another Emily Dickinson, had she only had the medium of expression – who captivates our fancy. Her secret life is ours in the artless words of her historian.

Edwin Clark, New York Times, February 7, 1926

Perhaps it is most difficult for the general reader to find his way among the new novels, because they are a sort of forest labyrinth; only, that is one interest of travelling among them — the surprises, alarms, and rejoicings. Mr. A. C. Benson's posthumous story “The Canon,” published by Heinemann, is a sure choice if you love good writing, agreeably fresh thinking, and the fragrance of English gardens. “Lolly Willowes,” by Miss Sylvia Townsend Warner, a Chatto novel, should also find the reader who falls in love with a beautiful prose style, running along like a sunlit river, and telling a story in which there is a mystic, yet always human, touch. Should you prefer a romance which has a quite popular air, then get Mrs. Hull's new desert yarn “The Sons of the Sheik,” or Miss Rubv Ayres's tale “Spoilt Music,” with the lines from Swinburne on the wrapper:

It may be all my love went wrong, a scribe's work writ awry and blurred, Scrawled after the blind evensong, spoilt music and no perfect word.

The Graphic, February 20, 1926

37

38

WITCHES’ SABBATH

The witch, burned and persecuted throughout the centuries, was in the Bronze Age the Wise Woman. The Greeks made of her a priestess, and put on her shoulders the mantle of the goddess. She guarded fire for the Romans, and it was not till the legal fiat went forth, “thou shalt not permit a witch to live,” that mankind hunted her out, and no protest was lifted to shatter the leg-irons or douse the blazing faggots. Today witchcraft is considered a primitive form of superstition, and has indeed become so legendary that the witch has even taken unto herself a romantic form. So at least Miss Townsend Warner would have it in this clever, exquisitelywritten book, with its thin vein of underlying cynicism. One can by no means picture Lolly Willowes as a witch, even if in old age her nose would have perilously inclined towards her sharp chin. She was merely a bored spinster of middle age who had such a dull, comfortable, dependent existence and so many moments of leisure in which to think of herself that she got rather queer ideas into her head. And her mind being obsessed by such thoughts, it was not surprising that when she found a kitten, strayed into her room, she should accept it as a familiar spirit of the Devil. Incidentally, she imagines she meets the gentleman on two occasions, first at a witches’ Sabbath, at which the villagers dance hilariously, and again near a churchyard where his Satanic majesty appears as a jobbing gardener. Forthwith Lolly unburdens herself of the thought that has now become an obsession with her: –

I think you are a kind of black knight, wandering about and succouring decayed gentlewomen. . . When I think of witches, I seem to see all over England, all over Europe, women living and growing old, as common as blackberries, and as unregarded. I see them, wives and sisters of respectable men, Chapel members, and blacksmiths, and small farmers, and Puritans . . . And they think how they were young once, and they see new young women, just like what they were, and yet as surprising as if it had never happened before, like trees in spring. But they are like trees towards the end of summer, heavy and dusty, and nobody finds their leaves surprising, or notices them till they fall off.

The whole idea of the story is quaintly absurd, but Ms Warner has an inimitable sense of atmosphere and such a direct rapier-like irony that her book is a tonic for the reader by virtue of its strangeness, piquancy and originality.

Aberdeen Press and Journal, February 8, 1926

39

BACK TO WITCHCRAFT

Vicar Denounces Tendency

Strong disapproval of any tendency on the part of modern women to indulge in witchcraft was expressed to an interviewer yesterday by the Rev. G. B. Bourchier, of St. Jude’s Church, Hampstead. The interview was in answer to one with Miss Sylvia Townsend Warner, author of “Lolly Willowes,” who expressed her belief in an approaching renaissance of witchcraft. She declared that in her opinion modern women with any “talent for witchcraft” should encourage it, and become witches.

“I think witchcraft is one of the most evil things in life,” the Rev. Mr. Bourchier said to the “Daily News.” If there is any tendency on the part of modern women to practise witchcraft, it ought to be severely dealt with. Such ideas are frightfully wrong and dangerous.

“If a widespread renaissance of witchcraft is on the way, as Miss Warner says it is, more asylums will have to be built to hold the women who practise it. Women had much better occupy their time with good and helpful practices.”

Portsmouth Evening News, June 18, 1926

MODERN WITCHCRAFT

Authoress whose Belief Runs to Practice

(By an Interviewer)

Time was when many man slept ill o’nights, his skin bubbly with gooseflesh, because he feared the evil eye of the local witch. Strange, bearded old women were these witches, wise in the lore of root and herb, accompanied ever with a familiar, in the shape a black cat, and given nocturnal expeditions floating on broomstick.

They were often ducked in the village pond, these old women, and one had imagined the whole race had died out; but Miss Sylvia Townsend Warner, the authoress “Lolly Willowes, ” asserts that they still exist. She goes further than that, and declares that she is something of a witch herself.

Naturally, her pronouncement has caused great deal of discussion, especially among the clergy, who have declared with one voice against any attempt the part of modern women to dabble the craft.

“Dozens of people have written me the subject,” Miss Warner told me. They all want to know if I really intended my heroine to be witch. Of course I did. You know, I’m quite proud of being a witch myself.

“There is no reason why witchcraft should not be practised by every woman who has a talent for it, for it gives the power for which every woman

40

craves—the power to get her own way. Personally, I am convinced that we shall soon see a great revival of the old art, brought up to date, of course.

“Certainly, I not anticipate modern witches being burned at the stake. It is much more likely that they will become very honoured figures of the State, for witchcraft is not evil.

“A short stay in almost any country village will soon prove my point that witchcraft is not as dead as it’s made out to be. In some places I know the people date happenings as taking place when Mother So-an-So was the witch. There is always an heir to the throne, too. for when one dies another is found at once to take her place.

“Mind you, witchcraft is not confined to the country. It is just as rampant in London. Many a large, gloomy house in Belgravia which is closed for months in the year has a caretaker who is also a practising witch. The difference between town and country is in the nature of the charms used. Rural witches cling to the traditional herbs and dried bats, while their town cousins use red flannel and glass beads as the instruments of their art.”

I asked Miss Warner how one would set about becoming a witch.

She laughed. “You are interested already,” she said. “Well, as a preliminary, take a trip into the country, where it is quiet and still. Make friends with animals and talk to the trees. No. It doesn’t matter about the black cat; any animal will do. After that perhaps things will come."

Although, I have said, the clergy oppose the idea tooth and nail, quite a number of very prominent women are intensely interested. Miss Tennyson Jesse [early female war correspondent, criminologist and author], who has met strange beliefs in the course of her travels about the world, told me recently that she would love to know enough witchcraft to able to do unpleasant things to people she really disliked. “When was in the West Indies.” she added, “I heard bloodfreezing stories of Voodooism, ‘there are more things in heaven and earth.' you know. And Shakespeare wrote those words in connection with an eerie situation, didn't he? Shakespeare knew things.”

Portsmouth Evening News, July 27, 1926

41

WOMEN AND WITCHES

The early part of the book is the story of a daughter of an old Conservative country family, from 1874 to 1920. For twenty-eight years Laura Willowes lived very comfortably at home; had nurses and governesses, and welltrained servants to look after her, kept house for her father when her mother died, and knew neither strong feelings, deep conviction, hard work, nor any physical discomfort. On her father's death she went to live with her married brother and his family in London. There her life was much the same, except that she was not quite so important to anyone as she had been to her father. She was “Aunt Lolly” to a number of young people, who rather liked her. All her relations were kind, they were also well off. They led regular, ordered, comfortable lives, and dear Lolly was quite a help! Once there was a chance that she might marry, but she disconcerted her pretendent by an odd remark about werewolves.

This remark introduces the latter part of the book. So far it has differed from other stories of frustrated women’s lives, only by the surety of its description and the purity of its style. The last part of the book, in which Laura breaks away from her relations, and goes to live in lodgings in a Buckinghamshire village, is different.

It is possible to take it in two ways; the way in which it appeared to Laura, and the way in which the reader suspects that it may have appeared to her friends. It is told entirely from her point of view, and it is only by subtle indications that the reader is led to guess that another view is possible. Seeing through Laura's eyes it appears that the village in the beech woods was a haunt of witches, and that Laura nearly became a witch. It is possible that this is what the author intends us to believe. But I cannot help suspecting that what we have before us is really a very acute and sympathetic description of oncoming of insanity; the kind of insanity that attacks people who have had nothing in their lives. Be this as it may, the story of Laura's mind is delicately and tenderly told, and not only she herself but all those who surrounded her are presented with a vividness which has no element of caricature. From the young and modern Titus, who came to Great Mop to write his life of Fuseli, but perhaps also to look after " Aunt Lolly," to the kitten, whom she took as an emissary of Satan, but received with characteristic kindness, they are all both real and attractive. The description of the village itself, and the way in which the atmosphere of that particular bit of countryside is conveyed are so good that for those alone it would be worth reading the book. But it has several aspects, and whether it is taken as a psychological study of an individual, as a contribution to the study of witches, as an essay on the woman question, or as a finely written story, it certainly should not be missed.

I. B. O’Malley, Common Cause, February 26, 1926

42

43

AMIABLE WITCH AND AGREEABLE DEVIL

Without wishing to be rude to Messrs. Chatto and Windus I cannot help regretting that in their very laudable desire to advertise Miss Sylvia Townsend Warner’s book “Lolly Willowes” they should have chosen the particular form of “puff” advertisement that they did choose. To try to make out that this first novel sensational story of a witch who “walked with Satan’’ (all printed in large old English type to make it the more exciting) by announcing — “Everyone is asking for the witch story,” is really not the way to make this particularly charming book a success. For people expect a series of thrills or at least sensation, when they are led on in this way, and may be disappointed if they do not get them. Miss Warner’s book is not at all of the sensational or thrilling type. It is as quiet as a mouse, as quiet as “Aunt Lolly” herself; as retiring as the delicious village of Great Mop to which she withdrew to pursue her unusual calling. There is no climax in this tale. It opens quietly creating in its first chapters the whole atmosphere of Victorianism, leisurely and rather spinsterish. The arrival of the arch-fiend himself is no occasion for hysterics. He arrives, inevitably has charming manners, and the dignity of a sympathetic archangel. We always suspected Lucifer to be like this, and not the cloven hoofed devil that other authors have imagined him. Miss Warner must clearly be a witch herself to describe him so well.

“Life becomes simple if one does nothing about it,” says Miss Warner . . . and that is practically the whole philosophy of Laura Willowes. She makes very few efforts, one to get away from her relations in London, and one (in which she helped by the emissary of Satan) to remove her nephew (“such a nice young gentleman”) from Great Mop when he invades her privacy to write a book on Fuseli. Needless to say, both these efforts are successful, and perhaps the moral of this book is that success attends the efforts those who make few, rather than those whose lives are one continued, efforts.

The Witch’s Christmas

We must quote Laura Willowes’ simple reactions to Christmas, for she does not allow even that unescapable festivity to upset the even tenor of her way. It is a lesson to us all. “Laura spent a happy afternoon choosing presents at the village shop. For Henry she bought a bottle of ginger wine, a pair of leather gaiters, and some highly recommended tincture of sassafras for his winter cough. For Caroline she bought an extensive parcel — all the shop had, in fact — of variously coloured rug-wools, and a pound’s worth of assorted stamps. For Sybil she bought some tinned fruits, some sugar biscuits, and a pink knitted bed-jacket. For Fancy and Marion, respectively, she bought a Swanee flute and a box with Ely Cathedral on the lid, containing string, which Mrs. Trumpet was very glad to see the last of, as it had been forced upon her by a traveller,

44

and had not hit the taste of the village. To her great nephew and great nieces she sent postal orders for one guinea, and pink gauze stockings filled with tin toys. These she knew would please, for she had always wanted one herself.”

There is another very quotable remark. When her sister-in-law Caroline asked her if she had met any nice people in the neighbourhood — “No. There aren’t any nice people, said Laura . . . As far as she knew this was her only slip throughout the day. It was a pity.”

And it was so true, had Caroline only known it. For when all the inhabitants of a village are witches and warlocks how can there any “nice” people? Fortunate village!

Sheffield Daily Telegraph, April 9, 1926

WORLD OF WOMEN

Witches Up to Date

No one would suspect that earnest and excellent society, the Six Point Group [a feminist group founded in 1921 to lobby for changes in the law in six areas of women’s rights], of any desire to dabble in magic, or fear that they will try to secure their worthy aims by such means as the witches used. But in their list of literary lectures to be given during the next few weeks, they have included one on witchcraft, by Miss Sylvia Townsend Warner, who will undoubtedly try to bring them to her belief that “Witchcraft would make an excellent pursuit for the modern woman.”

The heroine of her very original first novel, “Lolly Willowes.” Is a cultured middle-aged woman who seeks refuge from her possessive family and a chance to enjoy herself in a leisurely fashion in a Buckinghamshire village, and ultimately becomes a witch, secure in the protection of the Devil. Miss Townsend Warner did not convince all her readers that the lady could not have saved herself by a little pluck without resorting to such drastic means, or that there was much fun in being a witch. Since then she has hinted that she is herself a witch. She declares that there are many other witches in the country, and that she expects to see a renascence of witchcraft – amusing nonsense that some critics have taken seriously.

Illustrated London News, January 29, 1927

45

WITCHES INITIATION

A Six Years’ Contract with the Devil

Miss Sylvia Townsend Warner, who, as the author of “Lolly Willowes.” is regarded something of an expert on the subject, yesterday delivered a lecture on “Witchcraft” to the Six Point Group. She described the initiation of witch as follows:

The Devil, always adopting different guise, called on the witch-to-be and endeavoured to persuade her to join his cult. He could not force her to his will; it was a purely voluntary proceeding. The woman was then compelled to renounce the Christian religion, and was branded to the service of the Devil. A contract of about six years’ duration was then entered into during which the initiate was given supernatural powers. At the end of the contract time it was obscure what happened, some believing that the contract could be renewed, while others held the opinion that the Devil “did her in.”

The confessions of witches at their trials were often said be merely the products of their own imaginations, yet it was an established fact that these confessions agreed when witches were tried as far apart as Sweden and the Pyrenees. The “guilty” women were to be found in all social grades. Witchcraft still existed in certain parts, and in some villages there was always a witch.

The witch cult was like a pyramid with the Devil at the top. In each district there were covens composed of thirteen of the principal witches with an officer at its head who represented the Devil. This officer could either man or woman. There were more women witches than men.

Portsmouth Evening News, March 25, 1927

46

47

A REAL LIVE WITCH!

A friend of mine went to hear Miss Sylvia Townsend Warner, the authoress of “Lolly Willowes,” lecture on witchcraft to the Six Point Group this afternoon. She tells me that, after having listened to her for an hour and a half, there is absolutely no doubt in her mind that Ms Warner is a witch herself!

‘The Round of the Day,’ Westminster Gazette, March 25, 1927

WITCHCRAFT IN THE BALKANS

Witchcraft has quite taken the place of spiritualism as a popular topic of conversation.

The other day I told you of the amazing lecture on the habits of witches ancient and modern that Miss Sylvia Townsend Warner gave to the Six Point Group, and now she has just taken the chair at a meeting of the Near and Middle East Association, when Mrs. Hasluck told a thrilled audience all about witchcraft in the Balkans.

Miss Townsend Warner is the author of “Lolly Willowes, ” the story of a middle-aged woman who became a witch, and she tells me that there is still a village in Dorset where a company of witches are said to hold their Koven (meeting) once a week. As it is the 20th century, nobody says them nay. Tudor Music

Her new book, about an imaginary missionary who converts one small boy on an imaginary South Pacific island, and then discovers that the small boy only pretended to be converted out of loving-kindness (this is her description, not mine), will be out at the end of this month. In the meantime she is busy collecting, arranging, and editing a collection of Tudor music with Sir Henry Hadow. Witches do not take all her time, it seems, and she is really by profession a musician. Apparently there are hoards upon hoards of Tudor music, typically English, that no one has bothered to revive before.

‘The Round of the Day,’ Westminster Gazette, April 11, 1927

48

For nearly fifty years she was a woman as other women are: an affectionate daughter, a not unaffectionate sister, a meek sister-in-law, a popular maiden aunt. And then, suddenly, she determined not to be any of these things, but a woman who would live alone, unquestioned, and sleep, if she found such a proceeding convenient, without fear, in a ditch. this is one of those rare books that are not only works of genius, but also works of art.

Sylvia Lynd, Time and Tide, March 19, 1926

Mirror Cookery Book

OLD FASHIONED VINEGAR

Stillrooms are obsolete in modern homes, but ever since I read Sylvia Townsend Warner's amazing book “Lolly Willowes” I've been bitten by the desire to try my hand at cordials. The result has been loganberry vinegar—made on the principle of the raspberry vinegar beloved by the Victorians. You want two quarts of loganberries and two quarts of white wine vinegar and a pound of loaf sugar to each pint of the liquid. Put the fruit in a wide-necked bottle—or an unglazed jar will do—pour over the vinegar, cover and allow to stand for ten days, giving it a stir each morning. Next strain and measure the vinegar, allowing a pound of sugar to each pint. When the sugar is dissolved put the whole into a jar; place in a saucepan of boiling water and keep simmering for one-and-a-quarter hours, skimming occasionally. After it is cold it can be bottled for use—old wine bottles are excellent for this. About a couple of tablespoonfuls of the vinegar to a tumbler of water, soda water or halfand-half makes a delicious summer drink.

Daily Mirror, July 15, 1926

49

50