THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY College of presentsMusic

A Tribute to Carlisle Floyd

Heidi Louise Williams, Piano

Tuesday, October 4, 2022 7:30 p.m. | Opperman Music Hall

2

PROGRAM

Sonata in E-flat Major, Op. 81a ‘Das Lebewohl’ Ludwig van Beethoven Adagio - Allegro (1770–1827) Andante Vivacissimamenteespressivo

Jeux d’eau Maurice (1875–1937)Ravel

Nocturne No. 6 in D-flat Major, Op. 63 Gabriel (1845–1924)Fauré Barcarolle, Op. 60 Frédéric(1810–1849)Chopin

INTERMISSION

Sonata for Piano (1957) Carlisle Floyd Allegro risoluto (1926–2021) Lento assai – Andante con moto – Con moto – Poco andante Deciso – Allegro con brio

To Ensure An Enjoyable Concert Experience For All…

Please refrain from talking, entering, or exiting during performances. Food and drink are prohibited in all concert halls. Recording or broadcasting of the concert by any means, including the use of digital cameras, cell phones, or other devices is expressly forbidden. Please deactivate all portable electronic devices including watches, cell phones, pagers, hand-held gaming devices or other electronic equipment that may distract the audience or performers.

Recording Notice: This performance may be recorded. Please note that members of the audience may at times be included in this process. By attending this performance you consent to have your image or likeness appear in any live or recorded video or other transmission or reproduction made in conjunction to the performance.

Health Reminder: The Florida Board of Governors and Florida State University expect masks to be worn by all individuals in all FSU facilities.

Florida State University provides accommodations for persons with disabilities. Please notify the College of Music at (850) 644-3424 at least five working days prior to a musical event to request accommodation for disability or alternative program format.

Praised by New York critic Harris Goldsmith for her ‘impeccable soloistic authority’ and ‘dazzling performances’, American pianist Heidi Louise Williams has appeared in solo and collaborative performances across North America and internationally. Her engagements have included recitals at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall, Weill Hall at Carnegie Hall, the Taiwan National Recital Hall in Taipei, the Kennedy Center, the Chicago Cultural Center, the Brevard Music Festival, the French Embassy in Washington D.C., and festivals in France and Italy. She has given multiple guest artist residencies in leading conservatories and universities in Taiwan and China and has presented lecture-recitals and performances at national and international conferences held by the Society of American Music, the College Music Society, and the International Clarinet Association. Her playing has been featured on WFMT Chicago, Classic 99 St. Louis, WQLN Pennsylvania, and KUAT Tucson radio stations, on WWFM Trenton, New Jersey for David Dubal’s “The Piano Matters,” and on classical stations throughout Taiwan and Canada.

Williams is actively involved in the promotion of new music and has worked with many distinguished composers. Her 2011 Albany Records solo album, Drive American, was named among the top ten classical albums of 2011 in the Philadelphia City Paper, featured in Fanfare’s 2012 Critics’ Want Lists, and has been described as ‘veritably operatic’, ‘bold yet thoughtful’, ‘unflappable’, ‘provocative and stimulating’ (Fanfare), possessing ‘…the muscularity and poetic power to bring this demanding repertory to life’ (American Record Guide). Her 2019 Albany Records solo release Beyond the Sound, featuring sonatas by Griffes, Walker, Floyd, and Barber, was selected twice for inclusion in the 2020 Fanfare Critics’ Want Lists, garnering the headline by British music critic Colin Clarke: “Brilliant programming meets performances of fire meets excellent recording meets superb documentation: this is a significant release from all angles.” An avid chamber musician, Williams has collaborated with numerous outstanding American and international artists. Other recording projects for Albany Records include her award-winning 2018 release with soprano Mary Mackenzie, Vocalisms, a 2-disc album devoted to premiere recordings of American Art Songs by Crozier, Harbison, Primosch and Rorem; and Conversa, an album of North and South American cello-piano duos including a world premiere by André Mehmari, released in December 2021 with cellist Gregory Sauer. Her playing has been published in the Modern Classical American Songbook Volume I. She has also recorded for the Naxos, Centaur and Neos labels.

Recipient of both a 2020 Undergraduate Teaching Award and a 2020 Outstanding Graduate Faculty Mentor Award from Florida State University, Williams joined the FSU College of Music in 2007. Her growing roster of graduate and undergraduate students have won prizes regionally, nationally, and internationally in both solo and collaborative contexts; they have earned awards to pursue graduate and artist diploma degrees at prestigious institutions including the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, the Eastman School of Music, and the University of Michigan among others, and they are actively gaining employment in recognized teaching and performing roles both in the U.S. and abroad. Williams completed the B.M., M.M., and D.M.A. degrees at the Peabody Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, where she studied with Ann Schein and coached chamber music with Earl Carlyss, Samuel Sanders, Stephen Kates, and Robert McDonald. She is artist-faculty for the MasterWorks Music Festival, has served as festival pianist for the Sunriver Music Festival, and has also taught and performed at the Interharmony International Music Festival and Csehy Chamberfest in Philadelphia. For more information, visit www.heidilouisewilliams.com.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

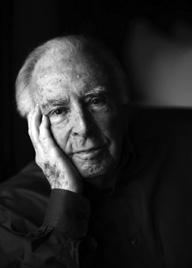

CarlisleCOMPOSERFloyd

, the “Father of American Opera,” was one of the greatest composers and librettists of opera of the last century. Born in 1926, Floyd earned B.M. and M.M. degrees in piano and composition at Syracuse University. He began his teaching career in 1947 at Florida State University, remaining there until 1976, when he accepted the prestigious M. D. Anderson Professorship at the University of Houston. In addition, he was co-founder with David Gockley of the Houston Opera Studio, jointly created by the University of Houston and Houston Grand Opera.

Floyd first achieved national prominence with the New York premiere of his opera Susannah (1953–54) by the New York City Opera in 1956. In 1957 it won the New York Music Critics’ Circle Award and subsequently was chosen to be America’s official operatic entry at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. His second opera, Wuthering Heights, premiered at Santa Fe Opera in 1958, and continues to have life decades later—a critically acclaimed recording, released by The Florentine Opera in June 2016 on Reference Recordings, was listed in Opera News’ 10 Best Opera Recordings of 2016. Based on the Steinbeck novella, Of Mice and Men (1969) is another of Floyd’s most performed works throughout the world. It was commissioned by the Ford Foundation and was given its premiere by the Seattle Opera in 1970. Bilby’s Doll (1976) and Willie Stark (1981), were both commissioned and produced by the Houston Grand Opera, the latter in association with the Kennedy Center. A televised version of the world premiere production of Willie Stark opened WNET’s Great Performances series on the PBS network in September of 1981. Cold Sassy Tree (2000), received its premiere at Houston Grand Opera in April 2000. Subsequently, it has been performed by Austin Lyric Opera, Central City Opera, Lyric Opera of Kansas City, Opera Carolina, Opera Omaha, San Diego Opera, Utah Opera, and Atlanta Opera. Floyd’s most recent opera, Prince of Players, premiered in March 2016 as a chamber opera by the Houston Grand Opera. The world premiere live recording of the opera by Florentine Opera, Milwaukee Symphony, and William Boggs on Reference Recordings was nominated for two GRAMMY Awards in 2021: Best Opera Recording and Best Contemporary Classical Composition.

His non-operatic works include the orchestral song cycle Citizen of Paradise (1984), which received its New York premiere with world-renowned mezzo-soprano Suzanne Mentzer. A Time to Dance (1993), his large-scale work for chorus, bass-baritone soloist, and orchestra, was commissioned by the American Choral Directors Association.

Among Floyd’s numerous awards and honors are a Guggenheim Fellowship (1956); Citation of Merit from the National Association of American Conductors and Composers (1957); National Opera Institute’s Award for Service to American Opera (1983); and the National Medal of Arts in a ceremony at the White House (2004). In 2008, Floyd was one of four honorees—and the only composer—to be included in the inaugural National Endowment for the Arts Opera Honors. Additionally, he served on the Music Panel of the National Endowment for the Arts from 1974–80 and was the first chairman of the Opera/Musical Theater Panel. In 2001, Floyd was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He also was inducted into the South Carolina Hall of Fame (2011) and the Florida Artist Hall of Fame (2015). He was awarded six honorary doctorates. During the 2015–16 season, Floyd partnered with Opera America to produce “Masters at Work,” a live, interactive webcast exploring the making of an opera.

Reprinted by kind permission of Boosey & Hawkes

ABOUT THE FEATURED

NOTES ON THE PROGRAM

Carlisle Floyd – Sonata for Piano

From Beyond the Sound (2019), liner notes by André Golbert

Considered the “Father of American Opera,” Carlisle Floyd (b. 1926) was a foremost opera composer and librettist in the United States. His long, fruitful career focused largely on humane subjects that transcend the regional and reach the universal, celebrating music’s ability to touch audiences across the globe. Floyd’s sensitivity toward socially unprivileged characters extends to his advocacy for women—seen both in feminist-themed operas, such as Susannah and Flower and Hawk, and in works based on novels by female authors, such as Wuthering Heights, Bilby’s Doll, and Cold Sassy Tree. Even if the piano seems less represented in the composer’s oeuvre than his operatic achievements, the instrument’s relevance in Floyd’s life was substantial. He began his career as a member of the piano faculty at Florida State University, a position he held for decades. Floyd dedicated his Sonata for Piano to his own teacher, the great Czech pianist Rudolf Firkušný.

Composed shortly after Floyd’s landmark success, Susannah, the Sonata’s robust colors and dramatic force infuse the piano with operatic grandeur. The Allegro risoluto’s ominous opening chords give way to an epic march punctuated by dotted rhythms. In contrast to the heroic bravura of the first theme, the expansive second theme enters with disarming intimacy, like a lone voice heard across a desolate landscape. The idea of human empathy, vital to Floyd’s operas, is here portrayed without words: this melody finds the company of a second voice in the following canon and is later embraced by the echoes of a richer texture. The solemn austerity of the Lento assai’s opening fugato contrasts with the middle section’s relentless ostinato, which, as Floyd conveyed in personal comments to Williams, evokes an ominous atmosphere similar to that of a murder mystery. The movement’s climax, a tortured cry which mirrors itself in extreme registers of the piano, yields to a pianissimo coda, where materials from outer and central sections are eerily juxtaposed. The rich dissonances that permeate this movement, combined with the punctuated rhythms thematic to the entire sonata, announce the final movement’s declamatory opening measures. Floyd’s savvy use of rhythm in the finale’s main theme, echoed in his ingenious reworking of the Deciso’s opening introduction as a slow, otherworldly middle section, lets its full mischief run loose in the final bars, bringing the sonata to a vigorous close.

Floyd is, of course, best known as a composer of musical theater. As I listened to your beautiful recording of his sonata, an operatic sensibility emerged, a give and take of musical phrases that suggest spoken dialogue. Am I hearing the music in the spirit as you play it?

Indeed, Floyd’s mastery of opera and large-scale dramatic narrative is legendary. I once heard my teacher, Ann Schein, declare that Chopin’s piano sonatas are like the operas he never wrote. Here, Floyd has infused this sonata with all the dramatic inspiration of his operatic voice. You can almost hear the opening section of the first movement as an overture. His innate melodic gift and his incredible use of orchestration, with its speech-like rhythms and colorful timbres that permeate his operas, fill the canvas of this sonata with the same declamatory richness. To quote a beautiful passage from André Golbert’s liner notes: “…the expansive second theme [first movement] enters with disarming intimacy, like a lone voice heard across a desolate landscape. The idea of human empathy, vital to Floyd’s operas, is here portrayed without words: this melody finds the company of a second voice in the following canon and is later embraced by the echoes of a richer texture.”

“Heidi Louise Williams, Champion of the Great American Piano Sonatas” By Peter Burwasser (excerpted from Fanfare, March/April 2020, 143-144)

An interesting backstory: It was this theme that decided the hall in which I recorded the album [Beyond the Sound]. I knew I wanted an epic-sounding live space and a New York Steinway that resonated with great richness and granitic power. Playing this theme on such a Steinway in Florida State University’s Ruby Diamond Concert Hall convinced me it had to be there. I had not even at the time made the connection that it was the very same hall that witnessed the premiere of Susannah, the opera that launched Floyd’s composing career in 1955.

I understand that you had the opportunity to play the Floyd Sonata for the composer. What a privilege! What kind of feedback did he give you?

Playing for Carlisle Floyd is an experience I will forever treasure. He is a very gracious, noble person; he communicated with precision and enthusiasm as he worked through the score with me. In both outer movements, he wanted broader tempos than the tempo markings indicate, giving a truly heroic, epic quality to the declamatory writing. In the slow movement he also advised: “Forget the metronome marks and let the music dictate.” Regarding dynamic shadings, pacing of transitions, voicing, phrasing, articulation, and rhythmic inflection, he stressed faithfulness to the score, referencing his frequent comment to singers: “You sing this beautifully, but I like it better the way I wrote it.” He admitted that this sonata is extremely difficult, one reason it is not more frequently played. He urged me to always keep going to hold the vast proportions of the structure together, yet to never become so fast that I lose the melodic intensity and intervallic clarity. The fugato section in the first movement he described as “bristling with tension.”

In the spacious second theme areas and the transitions surrounding them, he wanted layering of sonorities in an “impressionistic murmurando;” and where themes were especially lyrical, he coached me much like he might coach a singer, having me deliver whole phrases by moving into the middles of each one.

I asked him what his imaginative vision was for the dark, scary central section of the second movement, to which he responded with a grin, “This is like … a murder mystery.” The final chord of the slow movement he called “otherworldly” and insisted that the dissonance within it must cut like a knife. He said that dotted rhythms (which occur like a fingerprint in each of the three movements) must always be as taut as possible—reminding me of the opening of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata, Op. 111—to give maximum rhythmic tension. In the final movement, he encouraged directness of expression and a continually linear approach, despite the frequent non-legato articulation of the main thematic material. Of the mysterious middle section of this movement, a surreal mirroring of the opening Deciso, Floyd likened it to the “veils of Mata Hari.” He recounted how his teacher, Firkušný, gave the premiere performance of this sonata at Carnegie Hall. I asked (begged, rather!) if he had a recording of this performance, but he said he does not. How I would love to have heard Firkušný play the piece! Floyd unabashedly says that Firkušný was the inspiration behind it, much like Horowitz was to Barber’s Piano Sonata, Op. 26.