Sensing/Becoming Sensitive:

Creative Fieldwork and Connection to Place in Landscape Interpretation

Masayo Simon

MLA 2022

June 10, 2022

Project Advisor

Michael Geffel, Professor of Practice

creative fieldwork and connection to place in landscape interpretation masayo simon winter + spring, 2022

thank you to my collaborators + community:

Abby Pierce

Michael Geffel

Nina Elder

Liska Chan’s Overlook students

Chris Enright

Emily Scott

My cohort Mom + Dad

Laura

Eva

Meg

Mackenzie

project overview

abstract

The Land Lab is located on land that has been through many cycles of neglect and disturbance during the anthropocene--a term that many geologists use to describe the time period that settler-colonial practices of large scale dispossession, development and extraction led to the alteration of the geologic composition of many landscapes. The Land Lab is a case study of such a place--the history of gravel mining, agriculture, flood control, and fill have largely shaped this area, but these histories are now hidden-inplain site. The transformation of land through processes of digging, dumping, covering and smoothing of a landscape is a story that prevails through urban landscapes. How do we acknowledge these unseen landscape dynamics without centering and perpetuating narratives of damage and extraction in

central explorations

post-industrial landscapes? How do we call attention to and care for the novel ecosystems that have emerged as a result of disturbance?

This project uses art and creative fieldwork to investigate emergent means of engaging intimately with postextractive landscapes across time and space. This document shows a process of investigation that includes phases of independent inquiry, collaborative research, and community action research to explore experimental methods of prompting visitors to connect with this landscape. Through centering curiosity as a research tactic, this project aims to spark relationships of long-term engagement, deep attention, and care for the places that we often pass through without a deeper look.

What are some ways that creative fieldwork could be emphasized to center personal connection, long-term engagement, and care as crucial parts of the land analysis phase?

How can foregrounding collaborative research and community action research lead to relational practices of landscape interpretation?

What methods of interpretation acknowledge the complexities of post-extraction landscapes, while creating openings for reparative connection?

project goals

-Use methods of site analysis that honor dynamisms in observed site relationships and emphasize connection to landscape.

-Create openings for creative fieldwork and emergent research

-collaborative knowledge production

-non-solutionist

-foreground connection and experiential learning

-Develop facilitation and engagement methods to share learnings

approach/method/project design

oitatilicaf n o f m e t h o d independent community research public engagement

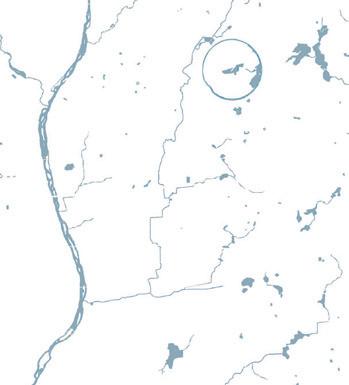

site current condition

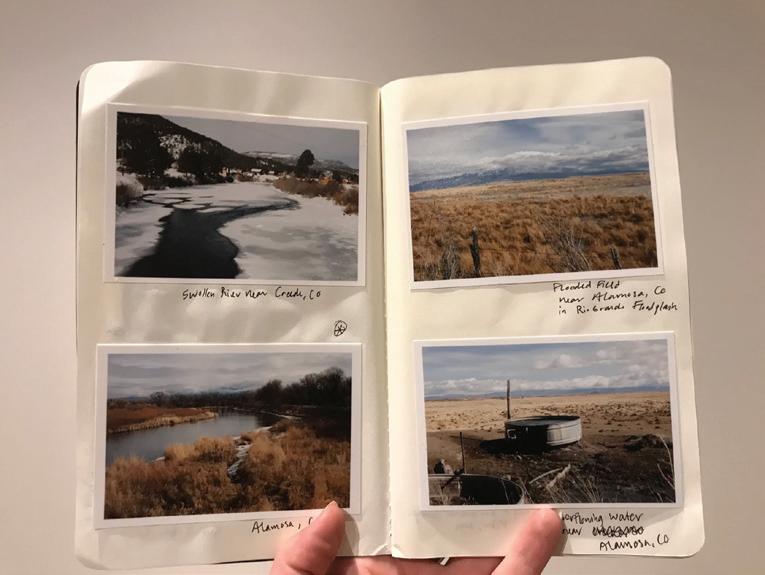

images from winter, 2022

Artist

“Oh! It’s so much more mundane than I expected. That makes me love it extra hard!!!

“Yeah I know it...I cross the river and walk on the other side.”

UO Professor

“This place is...kind of dumpy” Landscape Architecture Student

“It isn’t even really a place” Landscape Architecture Student

time + scale

what shapes this place

A simplified timeline of human + geologic influences at the North Campus Riverfront

missoula floods

18,000-15,000 years ago

Some factors that shaped this landscape prior to colonization (no particular order)

Geologic Changes:

The Missoula Floods formed the Willamette Valley and river systems. The sediment deposits that formed the gravel bedrock of the Willamette river created mineral rich soil along the bank.

0 5000 0 5000

bike path

landfill

gravel mine

Kalapuyan Land Care Practices:

Kalapuyan people maintain Willamette Valley landscapes through seasonal fire and food harvest. This relationship affected the ecology along the Willamette river bank until it was interrupted by settler occupation.

Flood & River Dynamics:

Before practices of damming and channelizing the river, this area was a flood plain. Flood disturbance maintained the balance of the riparian ecosystems. The Willamette River was a constantly changing, braided system.

beginning of settler occupation & forceful relocation of indigenous people

10000

10000

15000

15000

desig n o f p r o c e s s oitatilicaf n o f m e t h o d independent research

curious methods emergent research

“‘Emergence is the way complex systems and patterns arise out of a multiplicity of relatively simple interactions’...emergence emphasizes critical connections over critical mass, building authentic relationships, listening with all the senses of the body and the mind”

Adrienne Maree Brown, quoting Nick Obolensky, Emergent Strategy

responsive analysis curious

methods

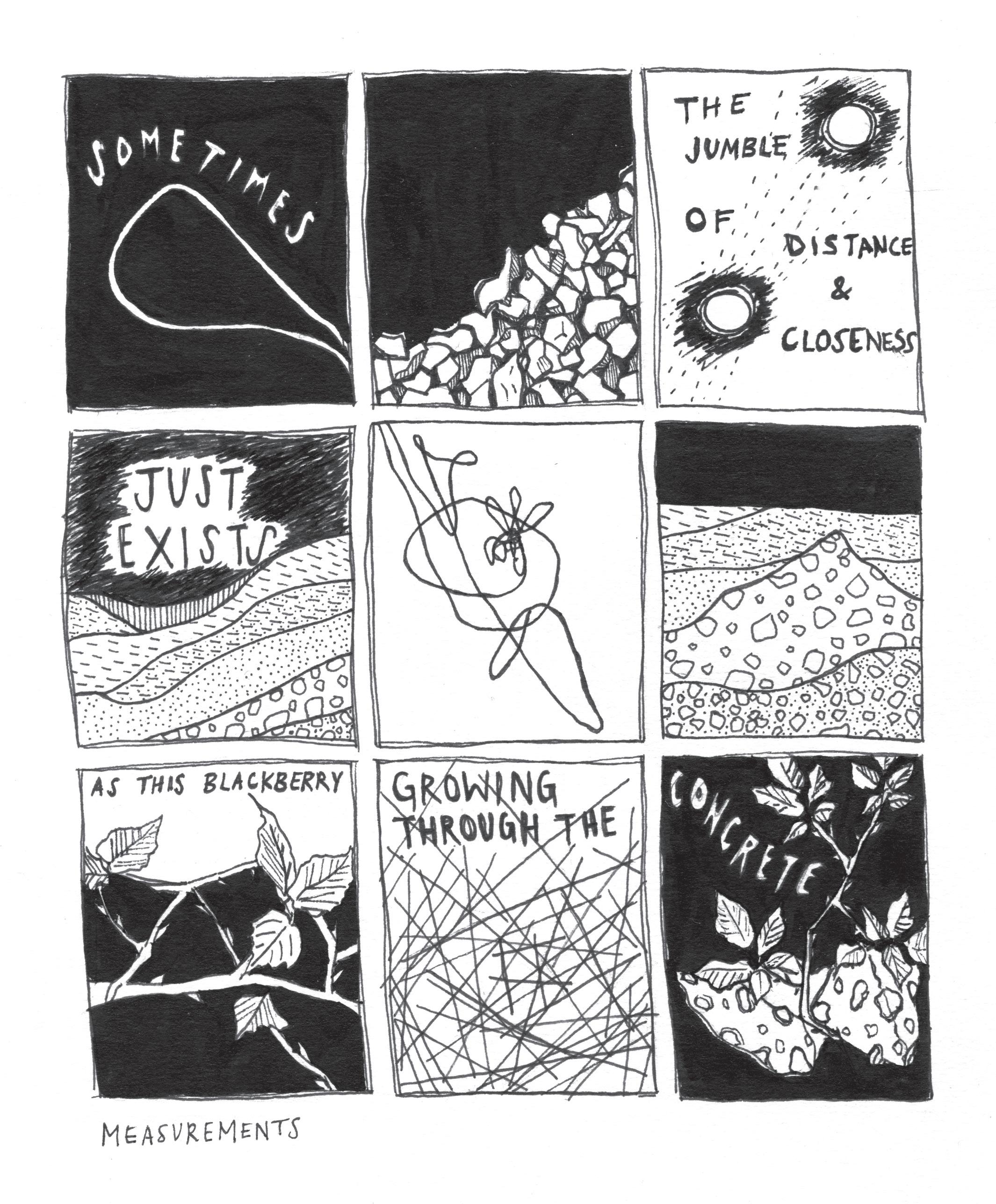

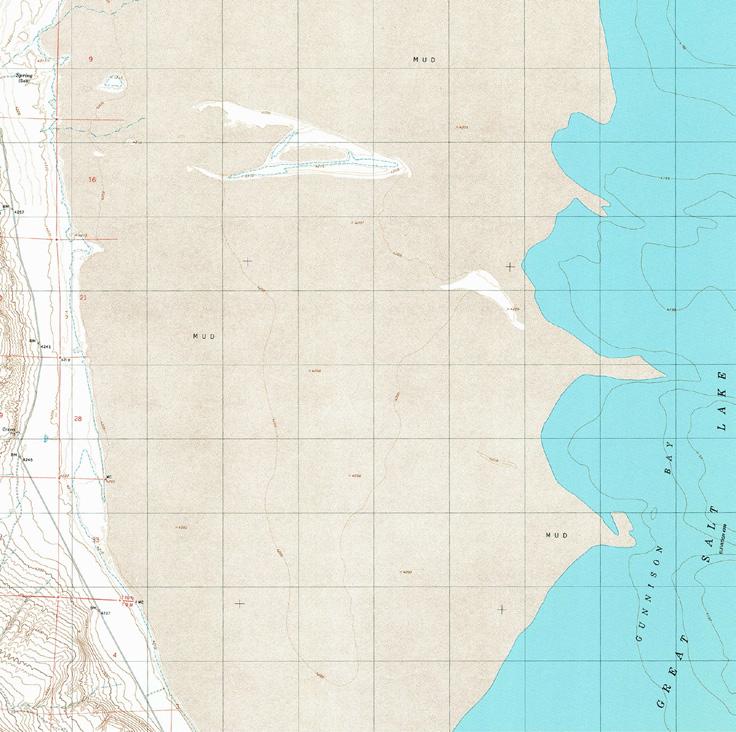

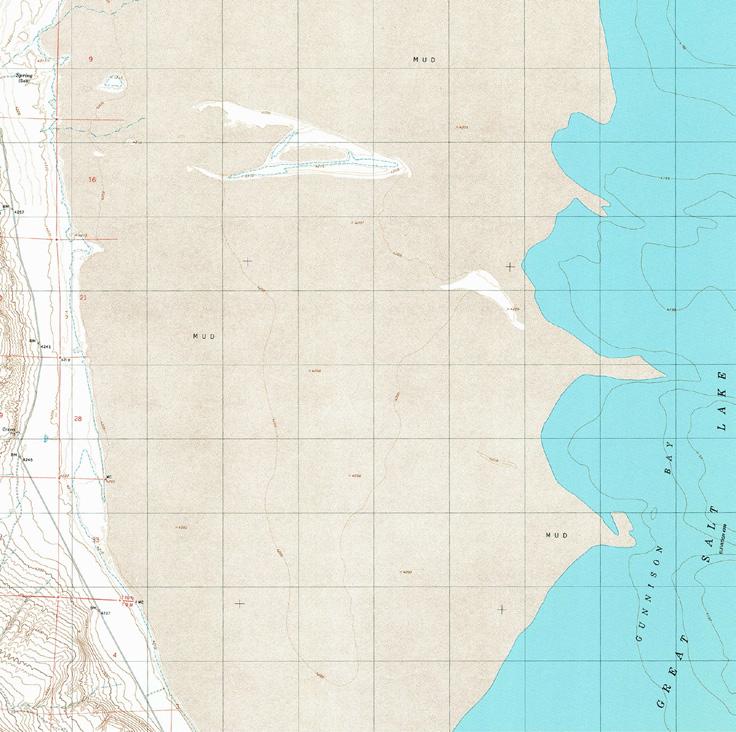

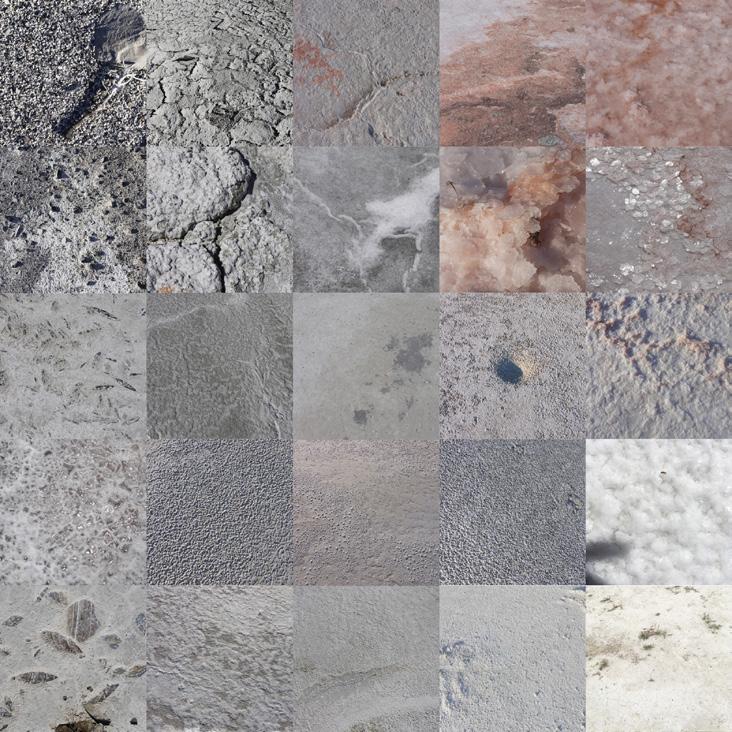

In Karen Lutsky and Sean Burkholder’s article Curious Methods, the two landscape architecture professors set out to map the gradients of material conditions of the Utah Mudflats. They realize that this task is impossible–as mud represents land in constant flux, while maps communicate stagnancy. Their method becomes a non-solutionist investigation of engaging with landscape through experience-based exercises. They are not looking to prove, but to engage with curiosity as a critical way of knowing place.

curious methods

Karen Lutsky & Shawn Burkholder

Karen Lutsky & Shawn Burkholder

a curiosity-driven research method focused on asking questions rather than finding answers.

“we seek to understand not what we see but how we interact with it, and how it is changed through the process...impressions on our senses help us see and feel changes in the landscape.

Karen Lutsky & Shawn Burkholder, Curious Methods

Karen Lutsky & Shawn Burkholder, Curious Methods

impression insight recording feedback questions inquiry

curious methods

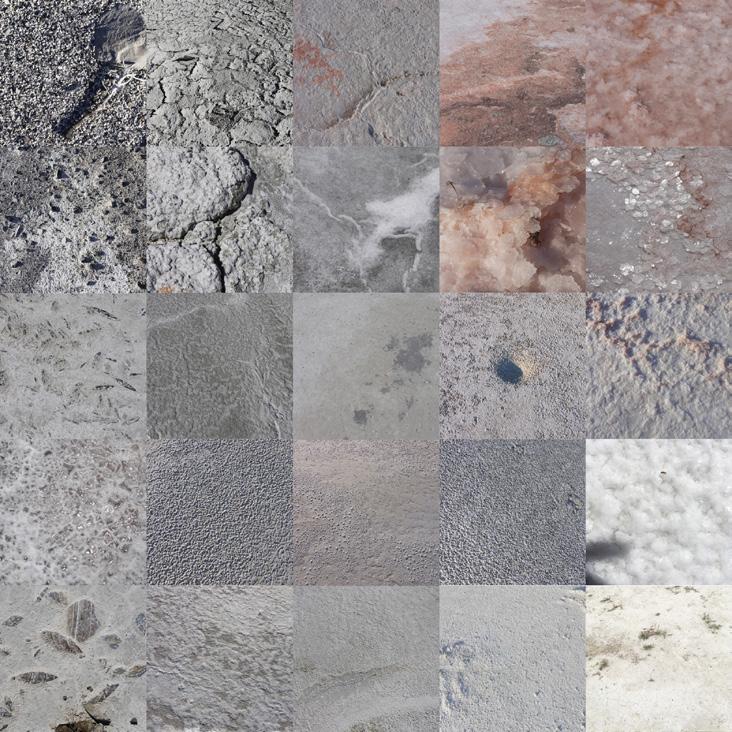

early explorations

Approach:

Weekly transect walk

Exploration:

Focus on sensory experience

Transect audio recordings

How do using other senses in research create deeper understanding of site?

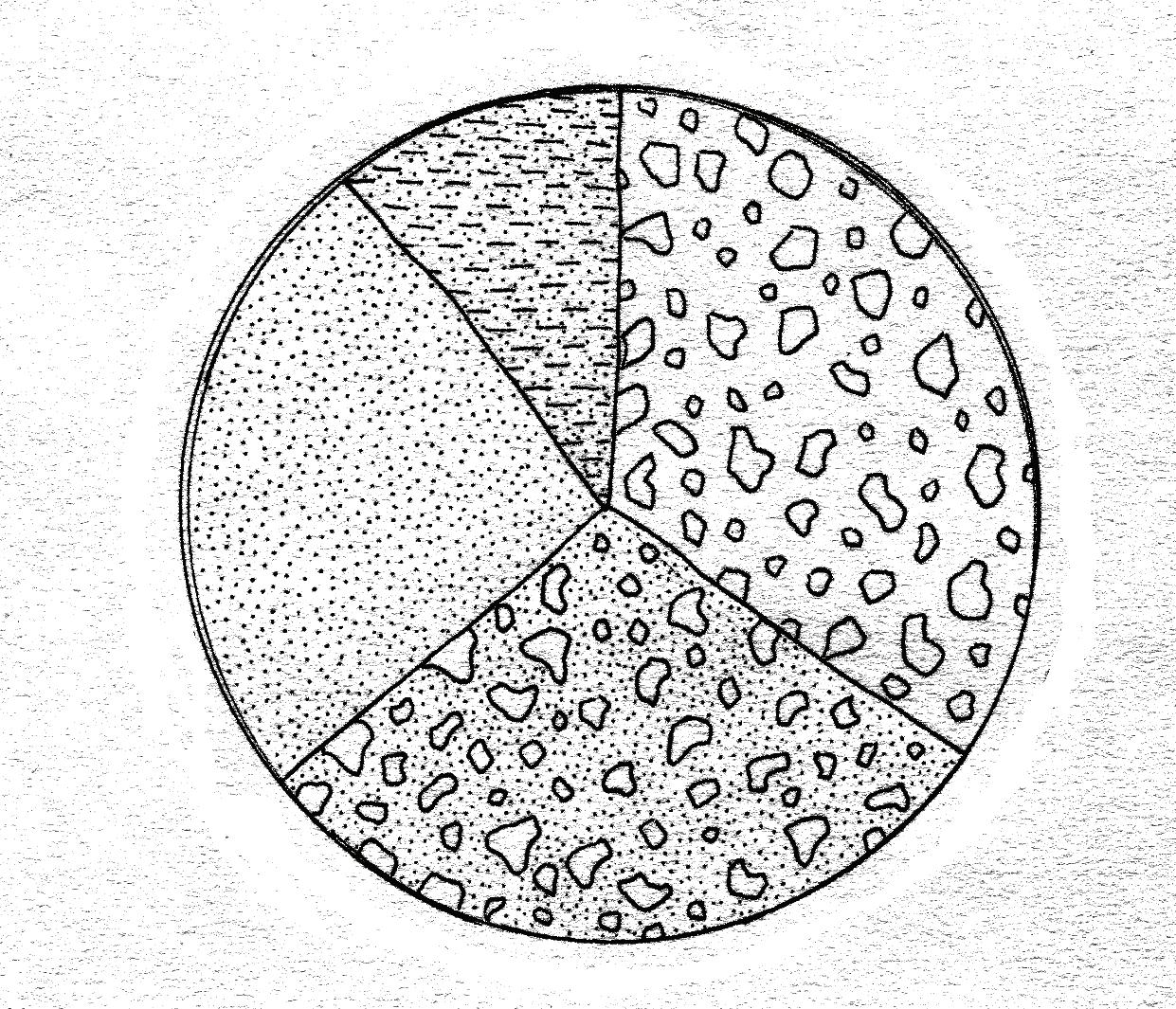

Transect ground conditions photo collages

materiality of site, inventory, material flows

Transect collection + physical collage prototype

Materiality, inventory, communication

Pile typology drawings

Inventory, site forensics, topography investigation

Ground Sensitivity Instrument prototype responsive prototype, sensory instrument, experiential tool, physical prompt

Narrative

WAIT uniform creation

Writing, synthesis

WAIT weekly work parties

Visibility of processes, labor, direct engagement with site

Care intervention, performance, physical engagement

Observations: Engagement Opportunity

Leading with attention creates deeper connection. Weekly commitment allows for feeling change.

Sound provides insight into unseen forces that make site dynamics (development, wildlife, etc.) Listening to a site lets us infer dynamics on different timescales.

Everything on this site could be considered a disturbance indicator. What does this say about this place?

The process of collecting is generative, but the display of collected items is not stand-alone informative.

How can we read site history and dynamics through its microtopography?

Could instruments be used as prompts to invite others to explore the site in new ways?

An easy way to communicate a holistic experience on site, effective exercise in reflection on all observed site dynamics up to this point. Does not translate to engagement.

Uniforms signified commitment and encouraged engagement in passerby.

People saw us working on site consistently, and often stopped to observe and ask questions.

field notes

field notes scanned objects + observations

I start at the train tracks. The piles of gravel imported from other places create the berm for a railroad build in the 1940s, when this land was a gravel mine. Sounds of steam from the physical plant behind the tracks permeate the space—when I turn my head I see a steady white pump of clouds escape the towering stacks. If I closed my eyes, what would I expect to see here?

I hear geese fly above often, they are drowned out by the sounds of industry. Which animals thrive in this soundscape?

I walk on uneven ground, I crunch through overgrown grass covering lumpy earth. The occasional blackberry tentacle snags my pants—unpredictable grabs from a plant that has been able to thrive on land that has suffered from almost two centuries of human abuse.

Somewhere under waste was put which were stacked boxes and then Glass was smashed The lines on the sites. But, like water and microbes that. They don’t neat lines.

Across the path is a grove of Black Cottonwood trees. These trees are often planted in remediated waste sites because they can grow on anything. This specific grove was not planted intentionally, the trees found their way here. They grow in what feels like a small valley, mounds all around them. What are these mounds made of? Large pieces of asphalt poke their heads out from blackberry and felled branches. English Ivy grows all the way up the trunks. Ivy is a tough plant, another one that can grows vigorously in sites of disturbance.

under my feet, chemical put into 1 gallon jars, stacked into cardboard then piled into a hole. smashed in the process. the map mark landfill memory, soil and microbes don’t work like don’t stay contained in

I am standing 15 feet above the original riverbank, a fact that I am made aware of by the acute drop-off that I am at the edge of. I look down. Huge, broken slabs of asphalt. The angle is so steep that they appear to be falling into the river. But they’ve been here for decades, moss growing on top of them, too slippery to climb down. This is the river bank. Piles.

desig n o f p r o c e s s oitatilicaf n o f m e t h o d community action research public engagement independent research collaborative research

WAIT... collaborative research

WAIT...slowscapes research collaboration

We Are Investigating Time (WAIT) is a research collaboration initiated by Abby Pierce and Masayo Simon. The research practices within this collaboration included performance, commitment, and long-term engagement with the site. Along with developing a collaborative practice of active observation, we also centered performing playful and celebratory acts of care to bring visibility to our own impact on the site.

“[avoiding the privatization of scholarship] means designing research that requires playgroups and collaborative clusters: not congeries of individuals...but rather scholarship that emerges through its collaborations.”

Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World

images: WAIT members seeding wildflowers on neglected easement, installing goose exclusion fence, (February, 2022)

WAIT wildflower seeding

WAIT project timeline

JAN

prototype design

FEB

wildflower seeding

goose exclusion fence design/ build

MAR

wildflower monitoring, fence modifications

WAIT Goose Exclusion Fence build APR

fence modification, paint and material tests

assisting each other’s projects

JUN

land lab soft launch

MAY

WAIT...slowscapes

lessons and reflection

1. Commitment, performance, and work parties were essential to community and personal engagement with site.

2. Working in collaboration encouraged fluidity in the shape of the project.

3. Uniforms brought visibility and transparency to our impact and presence on the site.

4. Centering fieldwork in the landscape research practice allowed for developing deeper ways of knowing the dynamisms present at the site.

desig n o f p r o c e s s oitatilicaf n o f m e t h o d community action research public engagement independent research collaborative research

sensing time student workshop

precedents

workshop precedents sensing time

1.

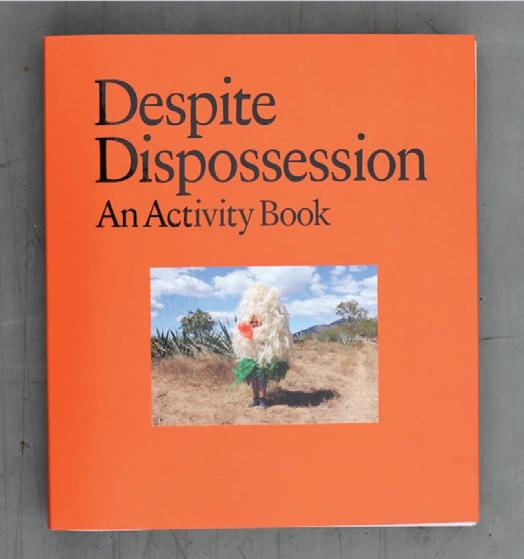

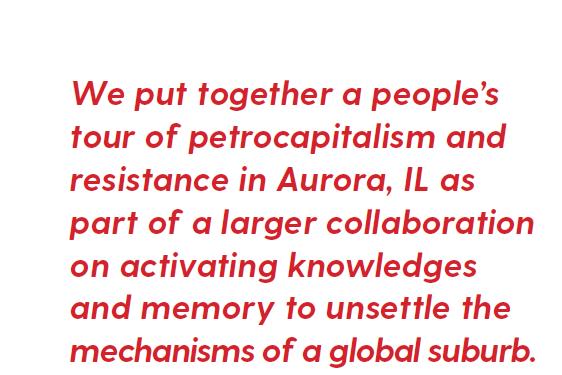

1. Rozalinda Borcilă Day-Tripping the Petrocapital 2016-ongoing

1.Rozalinda Borcilă, Day-Tripping the Petrocapital 2016-ongoing

critical tour collective knowledge production industrial site-reading

critical tour collaborative knowledge production history hidden in plain site site reading skills

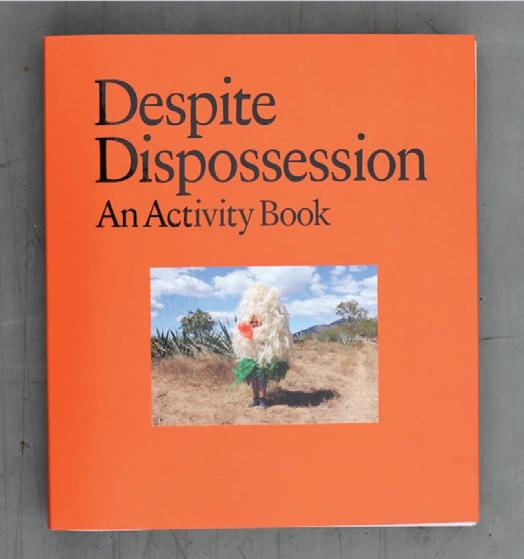

2. Sarah Kanouse Beyond Property: 2020 prompts embodied exploration field guide format “experiential curriculum”

2.Sarah Kanouse Beyond property 2020

prompts embodied exploration field guide

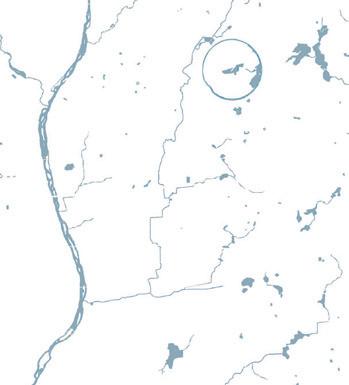

88 31 56 N Eola Rd Ferry Rd Diehl Rd 59 59 N Aurora EL JARDIN W Galena Blvd W Illinois Ave Randall Rd N Highland Ave Deerpath Rd Eola Rd Jefferson Ave Liberty St Aurora Ave E New York St Claim W Indian Trail Oak St Sullivan Rd E Trail NOrch rdRd MOUNDS WIG WAM DATA CENTER BURIAL MOUNDS ENBRIDGE PIPELINE DEVIL’S CAVE POLICE STATION ENBRIDGE PIPELINE FERMILAB MIGRATION AND EXTRACTION FOX RIVER THE BLACK SNAKE TOUR OF AURORA Petrocapitalism and Resistance in the Global Suburb High Union Farnsworth Ave N Ohio St Diehl Rd STREET We are fighting for our rights as the indigenous peoples of this land; we are fighting for our liberation, and the liberation of Unci Maka, Mother Earth. We want every last oil and gas pipe removed from her body. We want healing. We want clean water. We want to determine our own future. Ladonna Bravebull Allard DEDICATED TO ANTHONY MARTELL SANDRA BLAND AND ALL THE INDIGENOUS BLACK AND BROWN LIVES THAT HAVE BEEN SACRIFICED TO THE BLACK SNAKE. How can we profit from the blood in these markets? Casey Research

2.

3.

2021

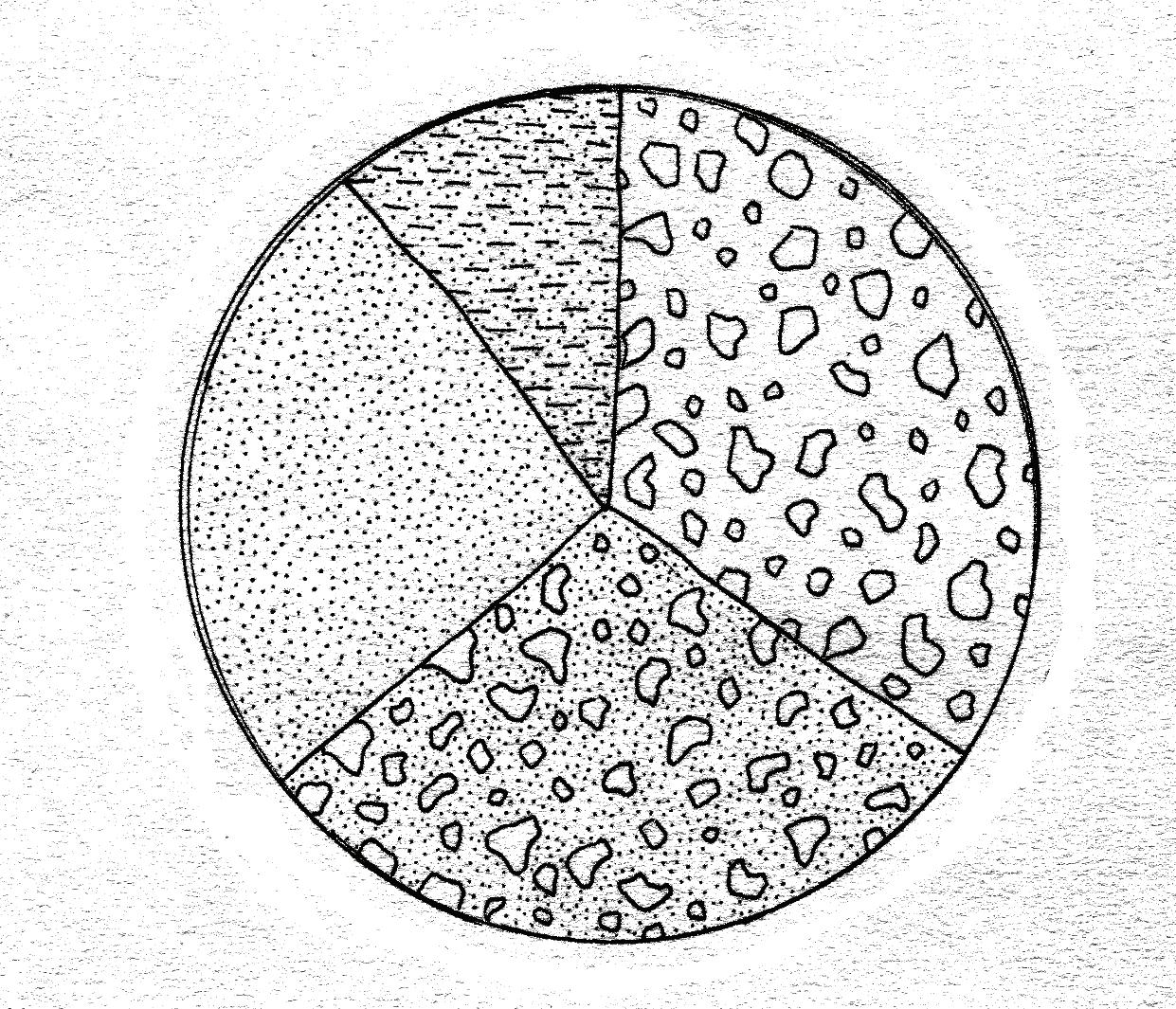

Despite Dispossession 2021

“site-sensitive engagements” sensory guide could apply to anywhere

“site-sensitive engagements” sensory guide can apply to anywhere

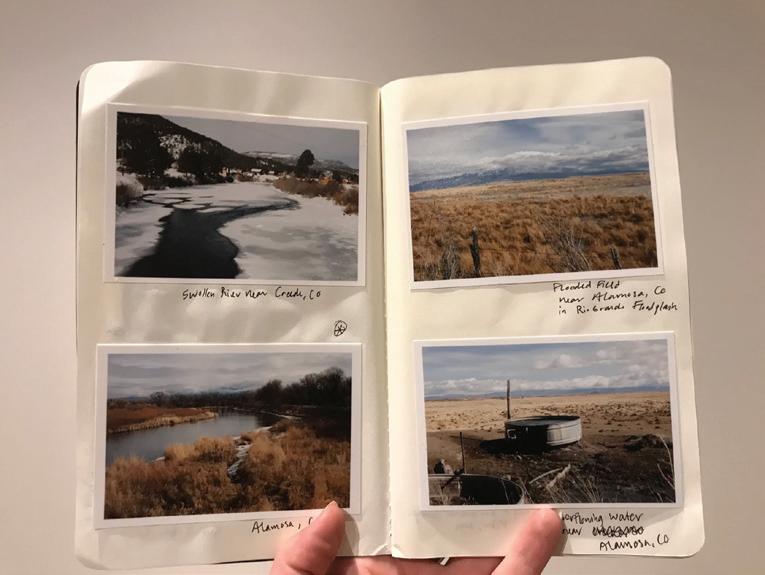

Solastalgic Archive

2019-2020

Nina Elder, Solastalgic Archive

2019-2020

collaborative memory deep-time scale object and inventory focused emotionally charged

collaborative memory deep-time scale collective inventory incorporates feeling

4.

3.Annette Baldeff, et al. Despite Dispossession

4. Nina Elder

3. Annette Baldeff, et al.

4.

3.Annette Baldeff, et al. Despite Dispossession

4. Nina Elder

3. Annette Baldeff, et al.

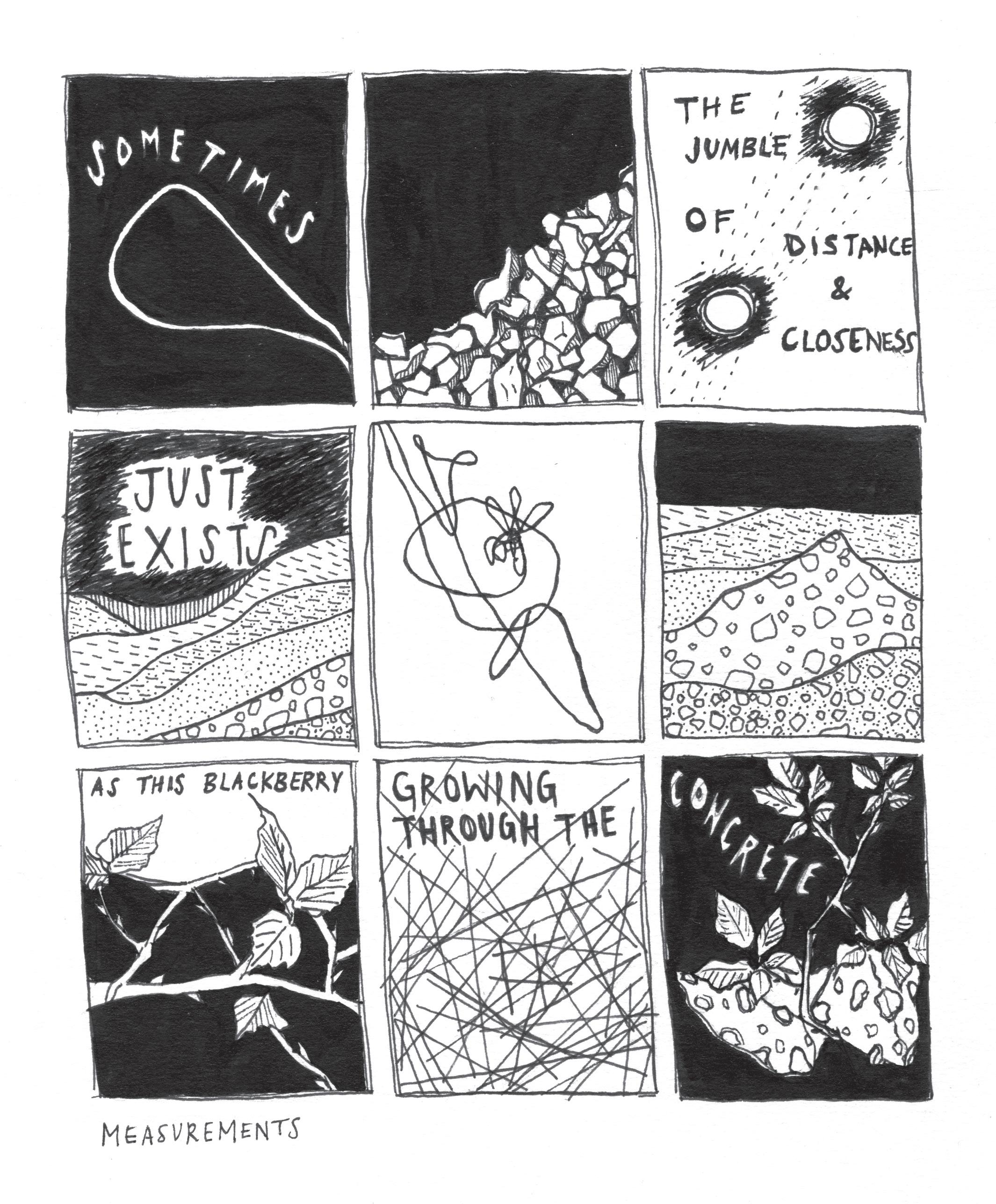

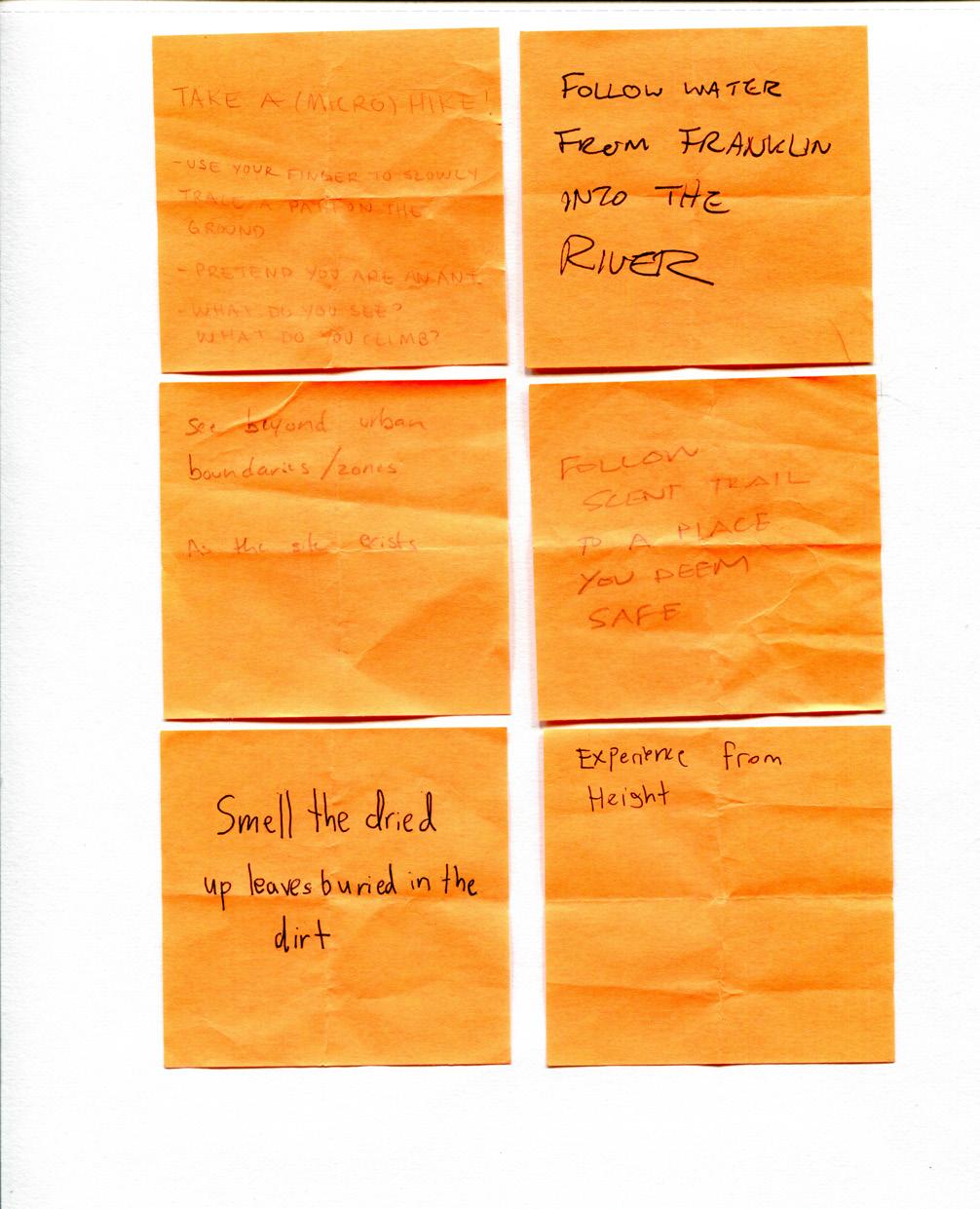

sensing time

student workshop, collaboration with Nina Elder

workshop description:

This workshop was about assessing and transforming our relationship with the North Campus River Front. How do we make sense of this place? Where do we find connections or entanglements? What is present here that could possibly cue us in to our place within this place? What does this exploration look like as a group of people rather than as individuals? How does tuning into our senses help our reading of place?

workshop goals:

• facilitate experience of collaborative investigation

• foreground exploration of embodied data

• generate zine/tour ideas

flow:

• deep time/grounding

• ways of knowing observation scavenger hunt

• make your own prompts

• perform prompts

• reflection

sensing time sensory

scavenger hunt

“Sensing is the operation that connects us to the world and the world to us...Sensing has its own politics. It will depend on how we construct, train, apply, and critically engage...”

Haus Der Kulturen Der Welt, A Curriculum for the Anthropocene

Above: worksheet recordings by year 1 MLA student, Tristan Matlock

Above: worksheet recordings by year 1 MLA student, Tristan Matlock

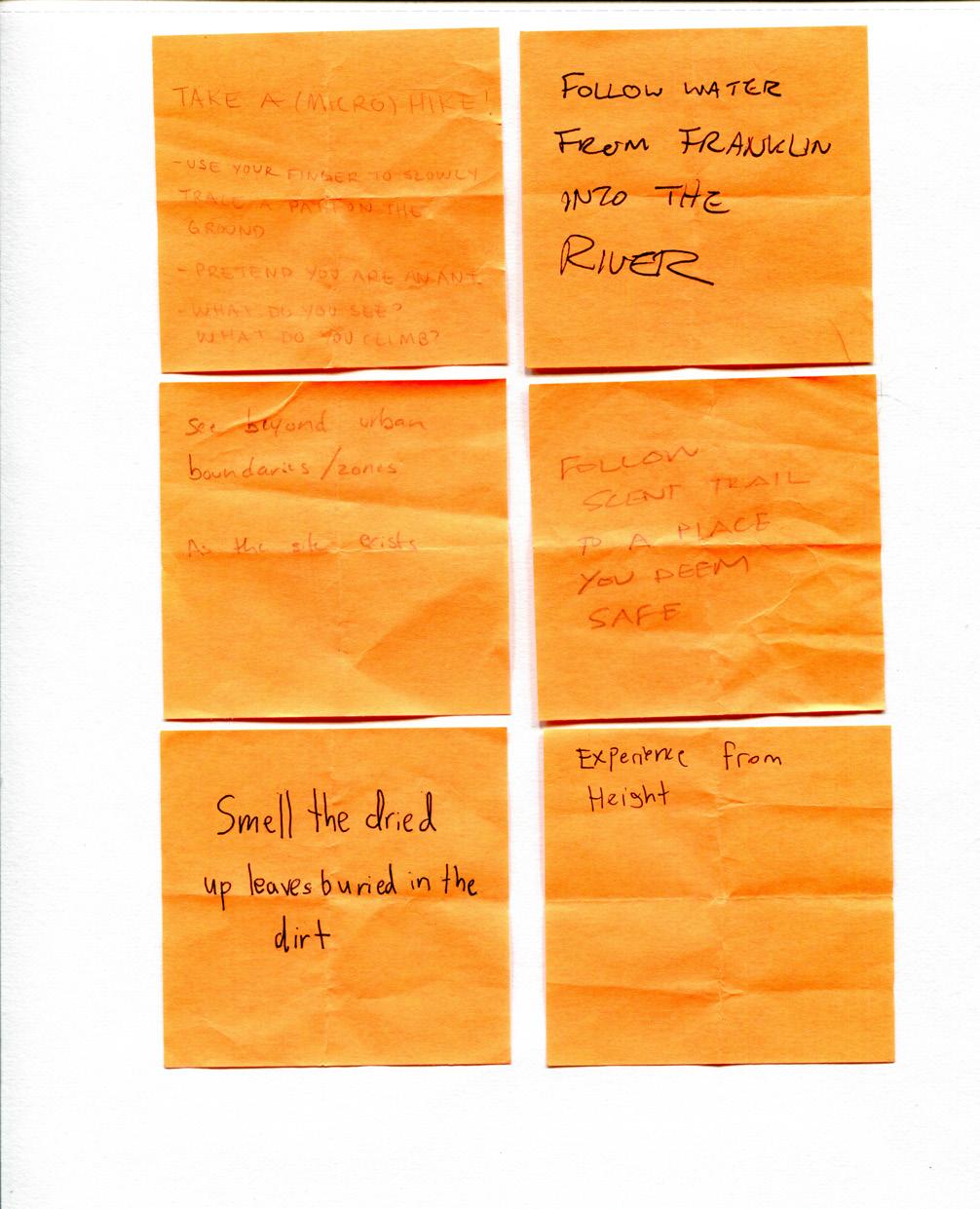

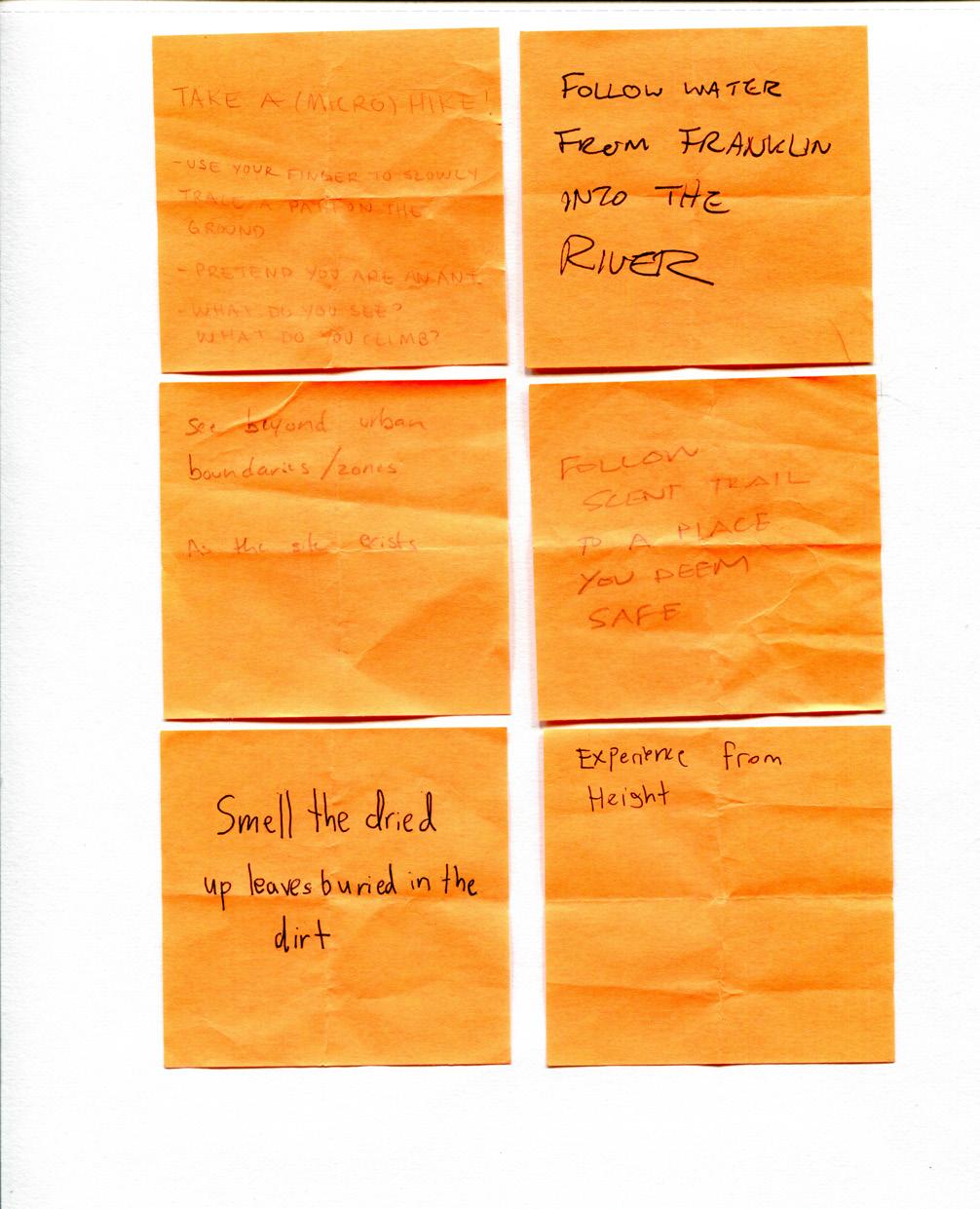

sensing time student generated prompts

“How is our presence impacting the site? How does the presence of other species impact the site, and what would it be like to be them in this place?”

Nina Elder

Above: Student generated prompts for exploring their relationship with the site

Above: Students investigate place through sensory prompts

Above: Students investigate place through sensory prompts

Left: A selection of student responses

Right: A composite of student responses

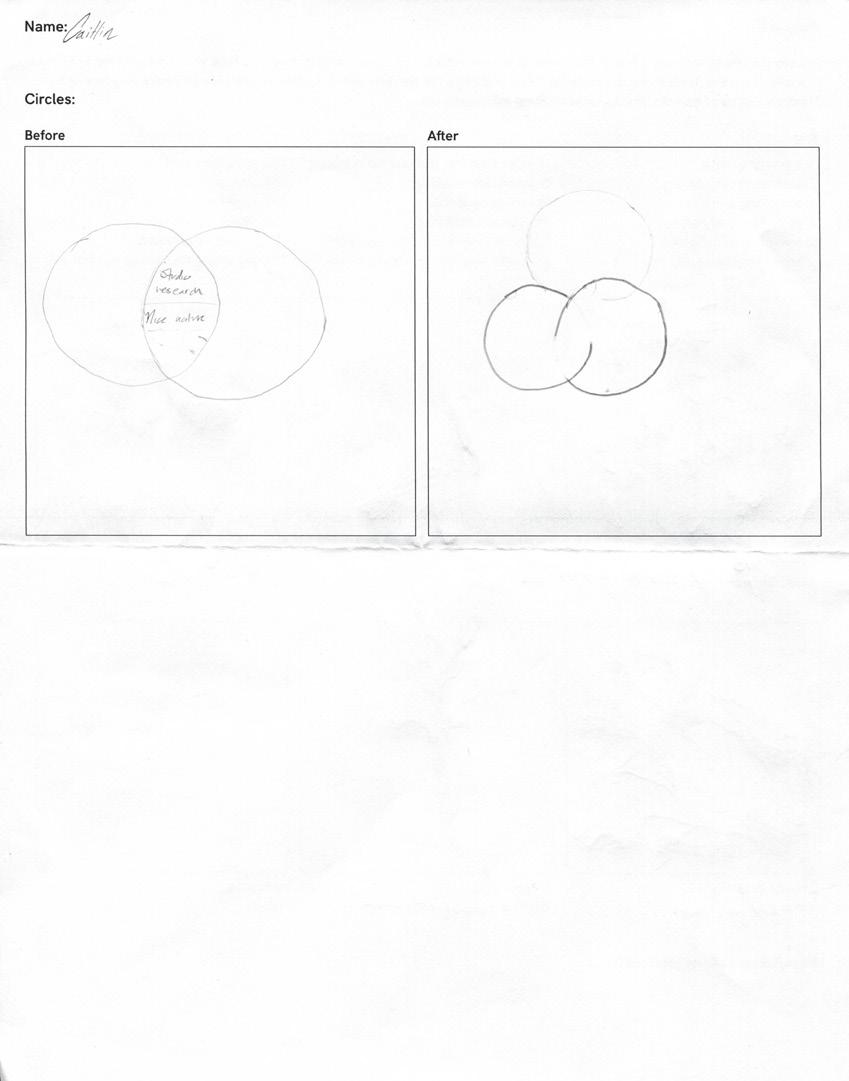

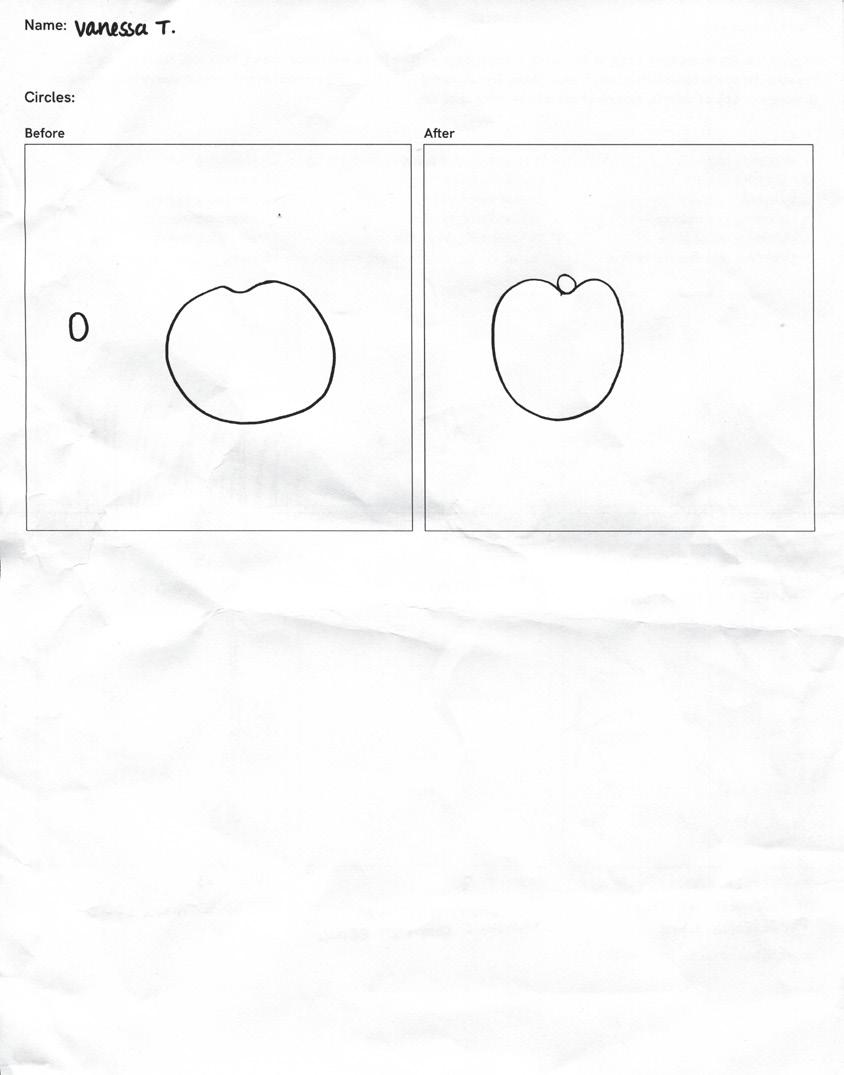

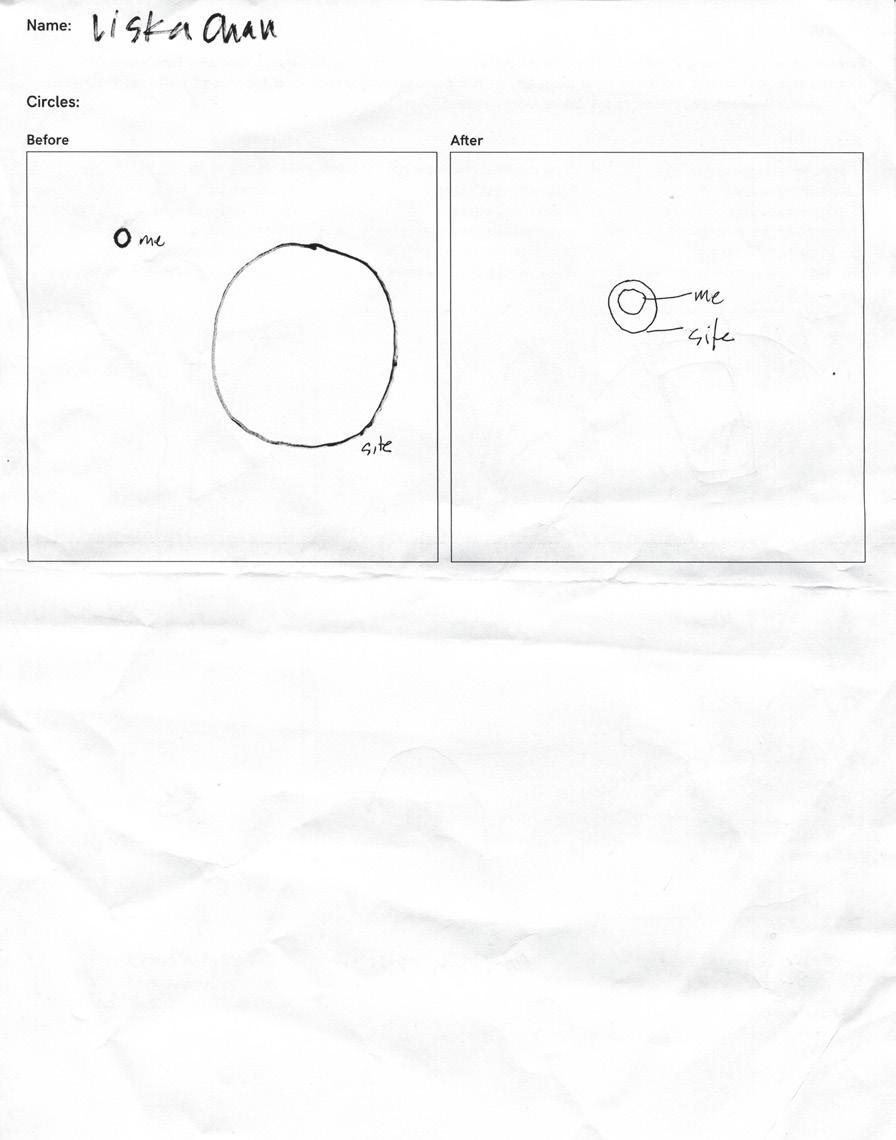

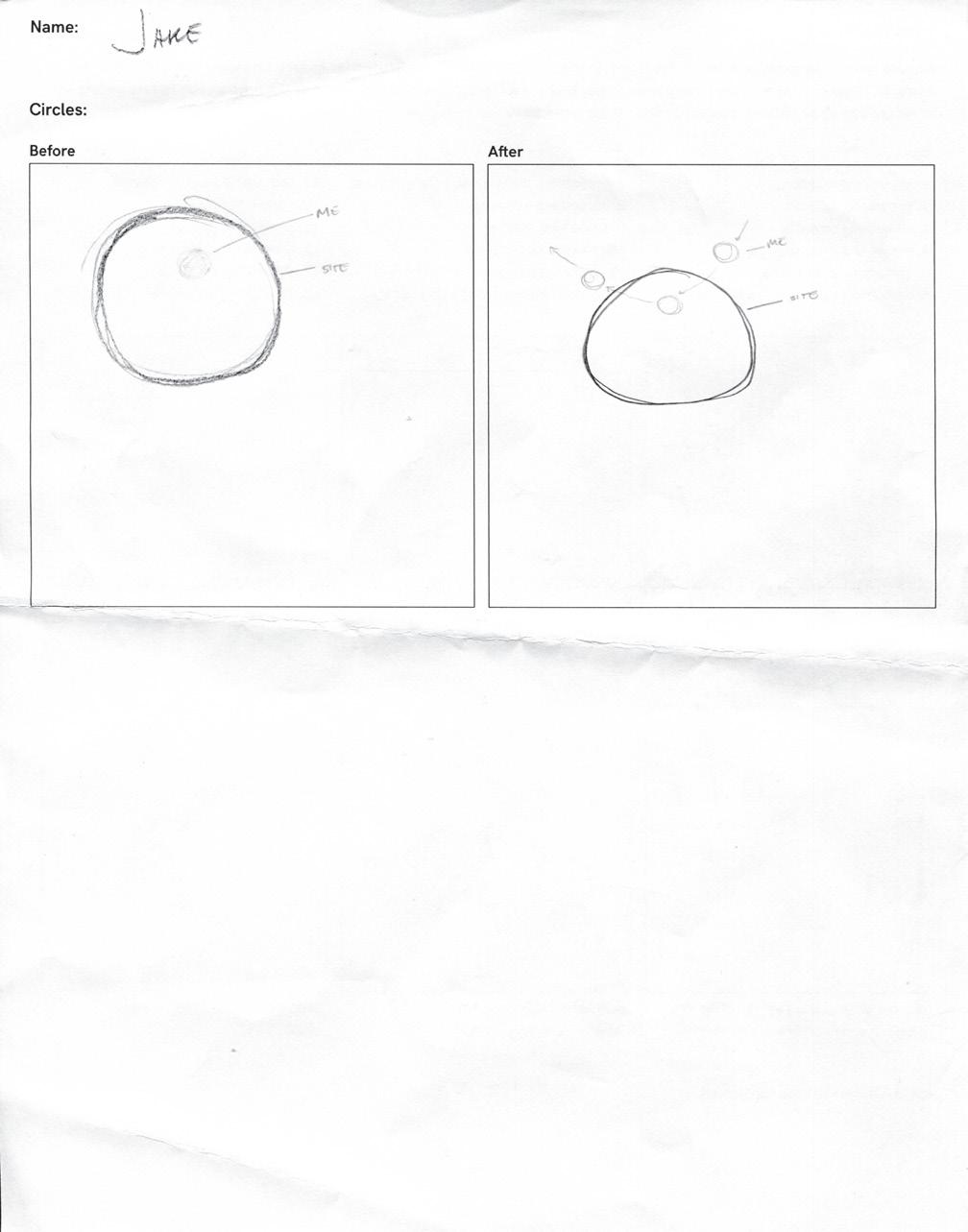

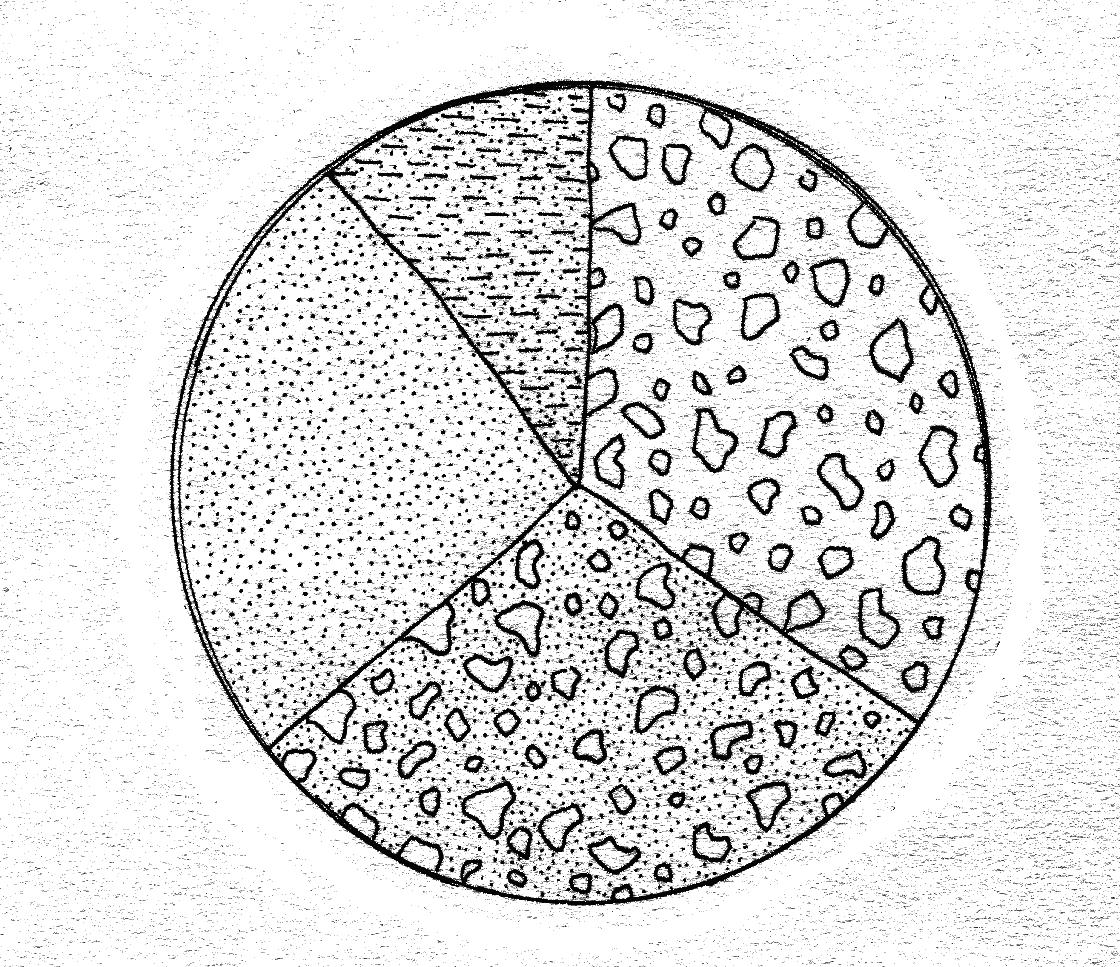

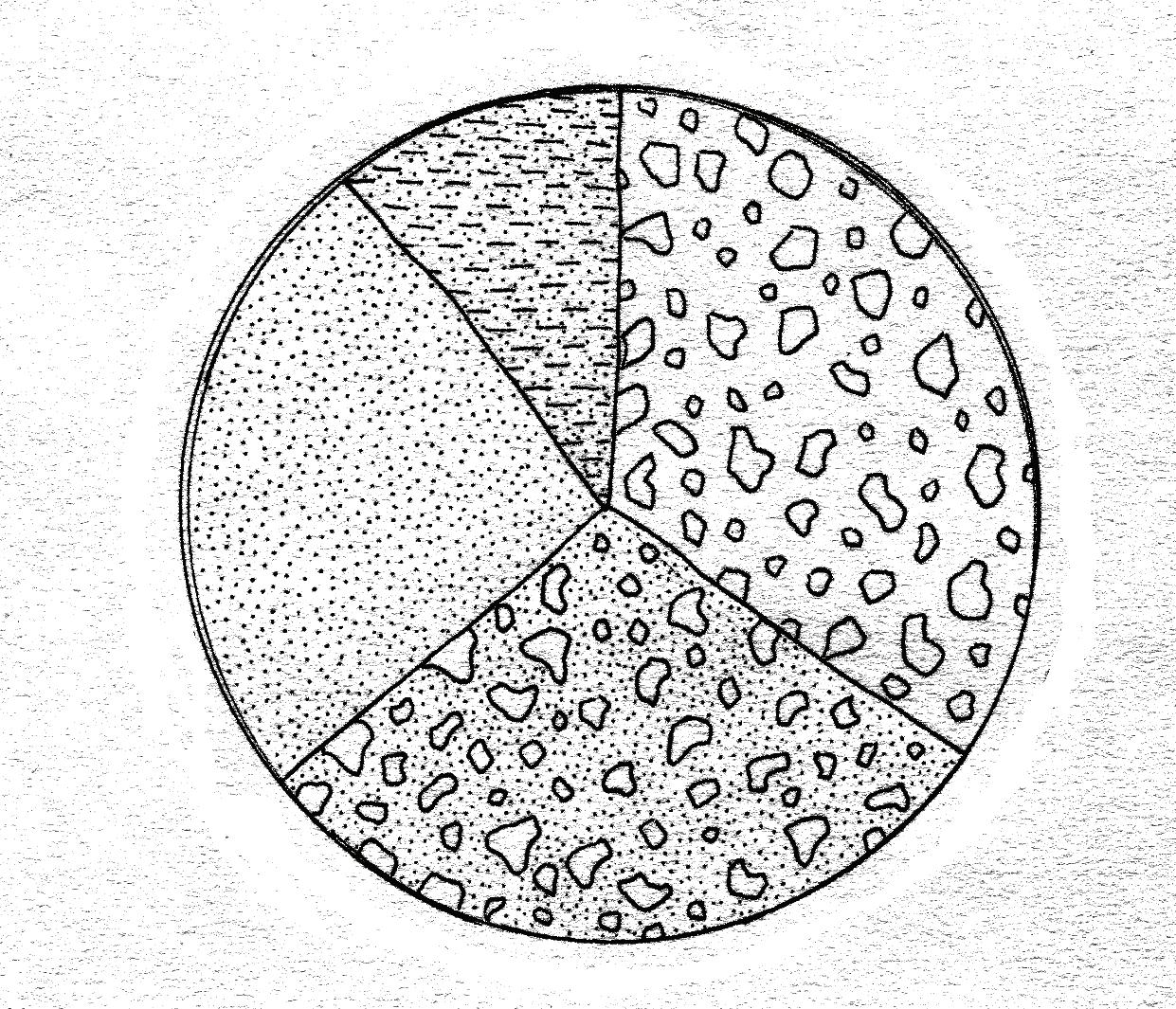

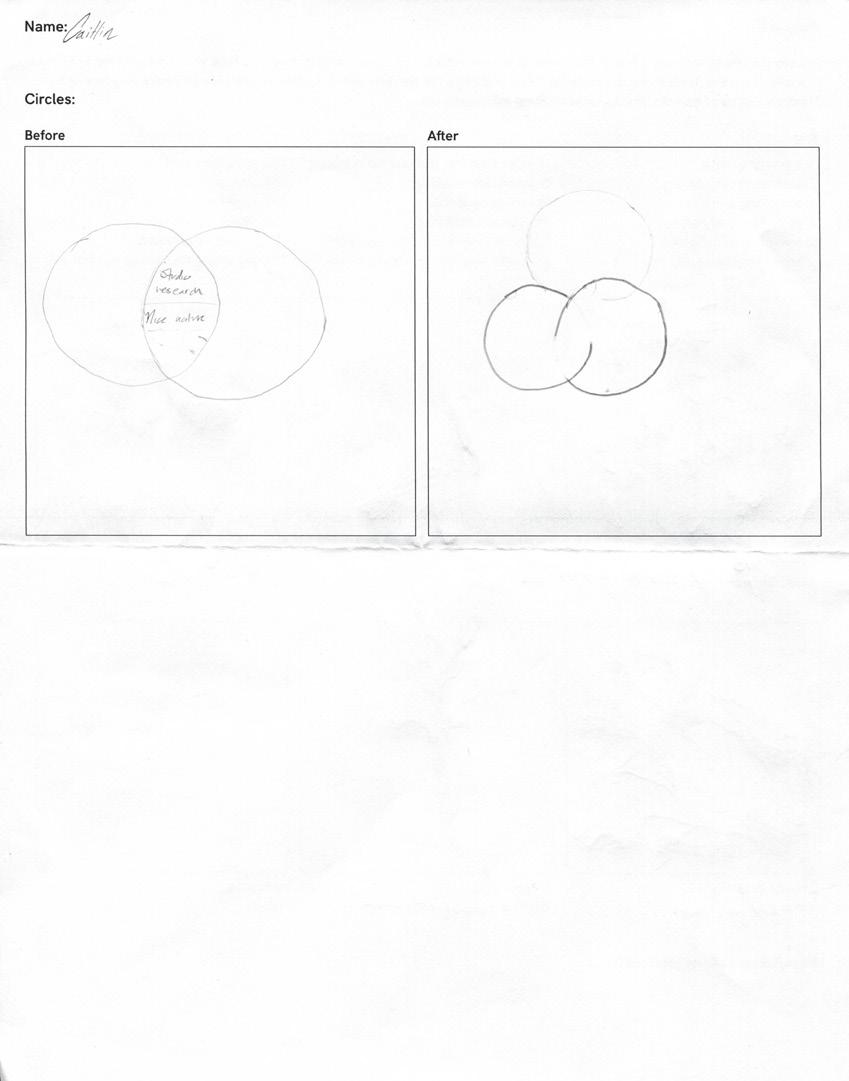

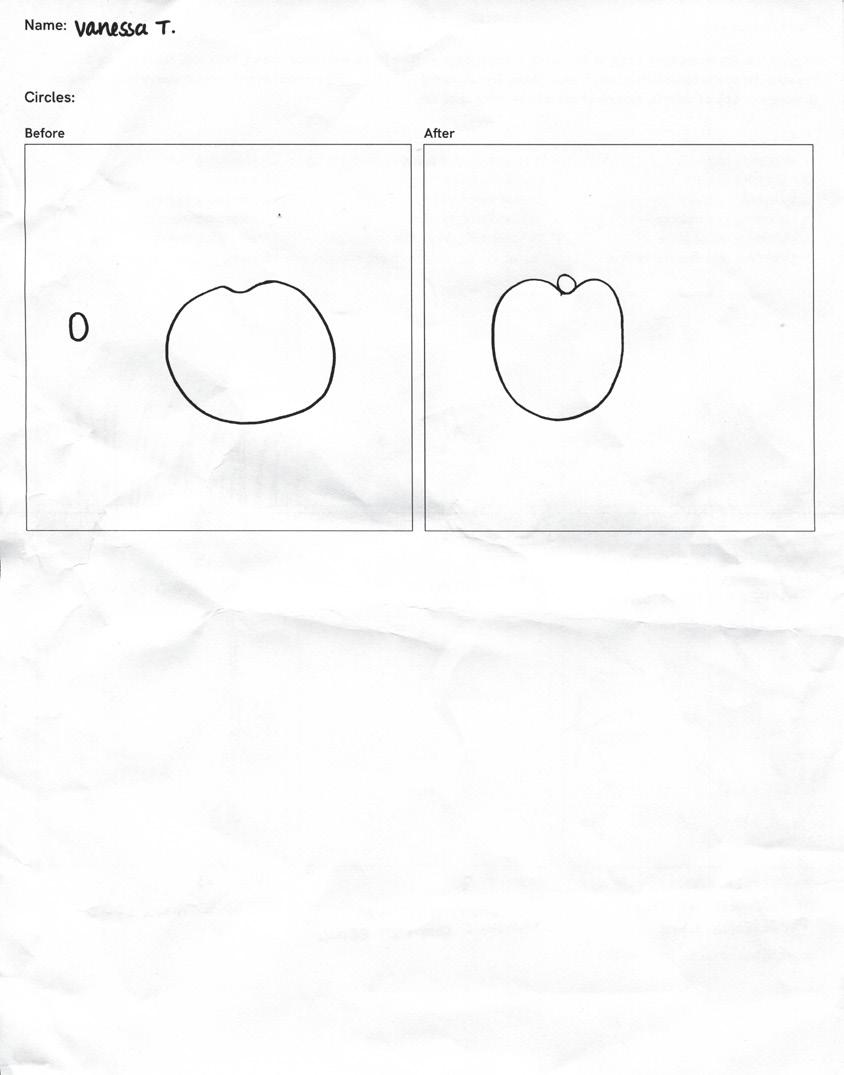

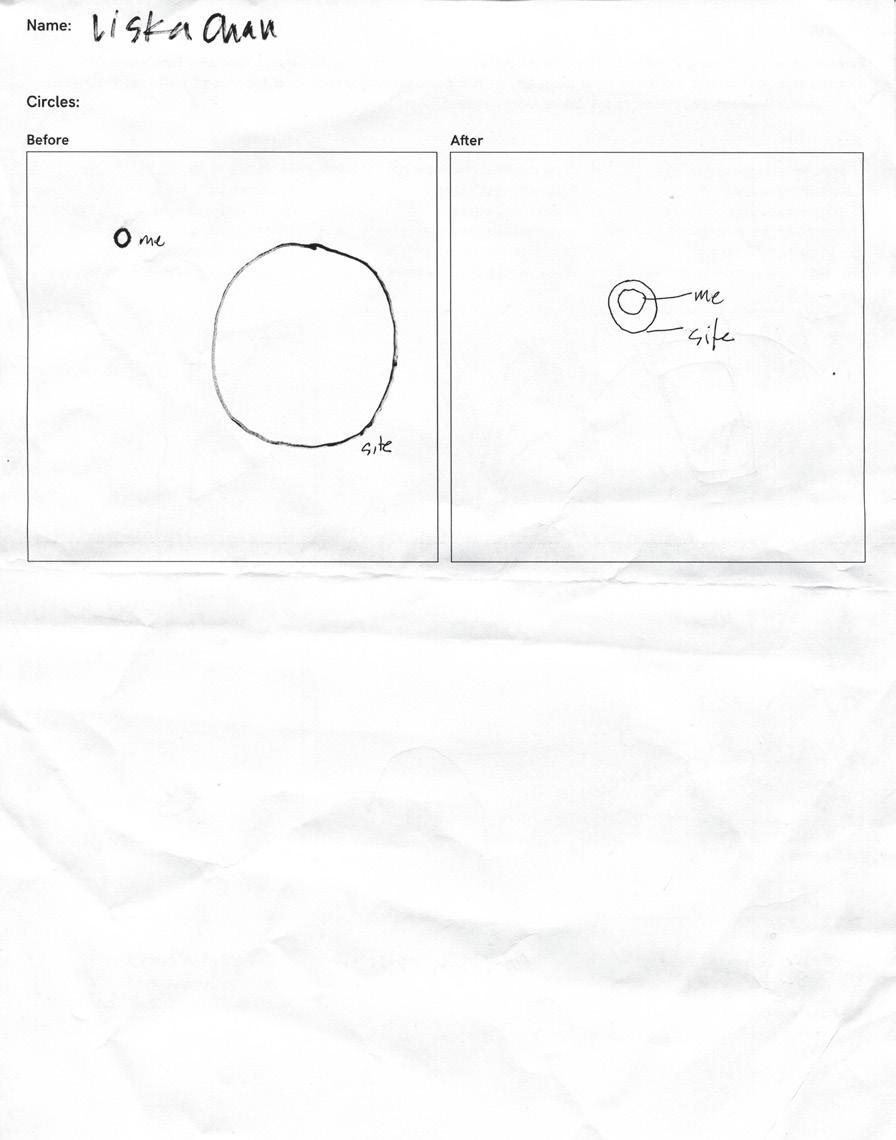

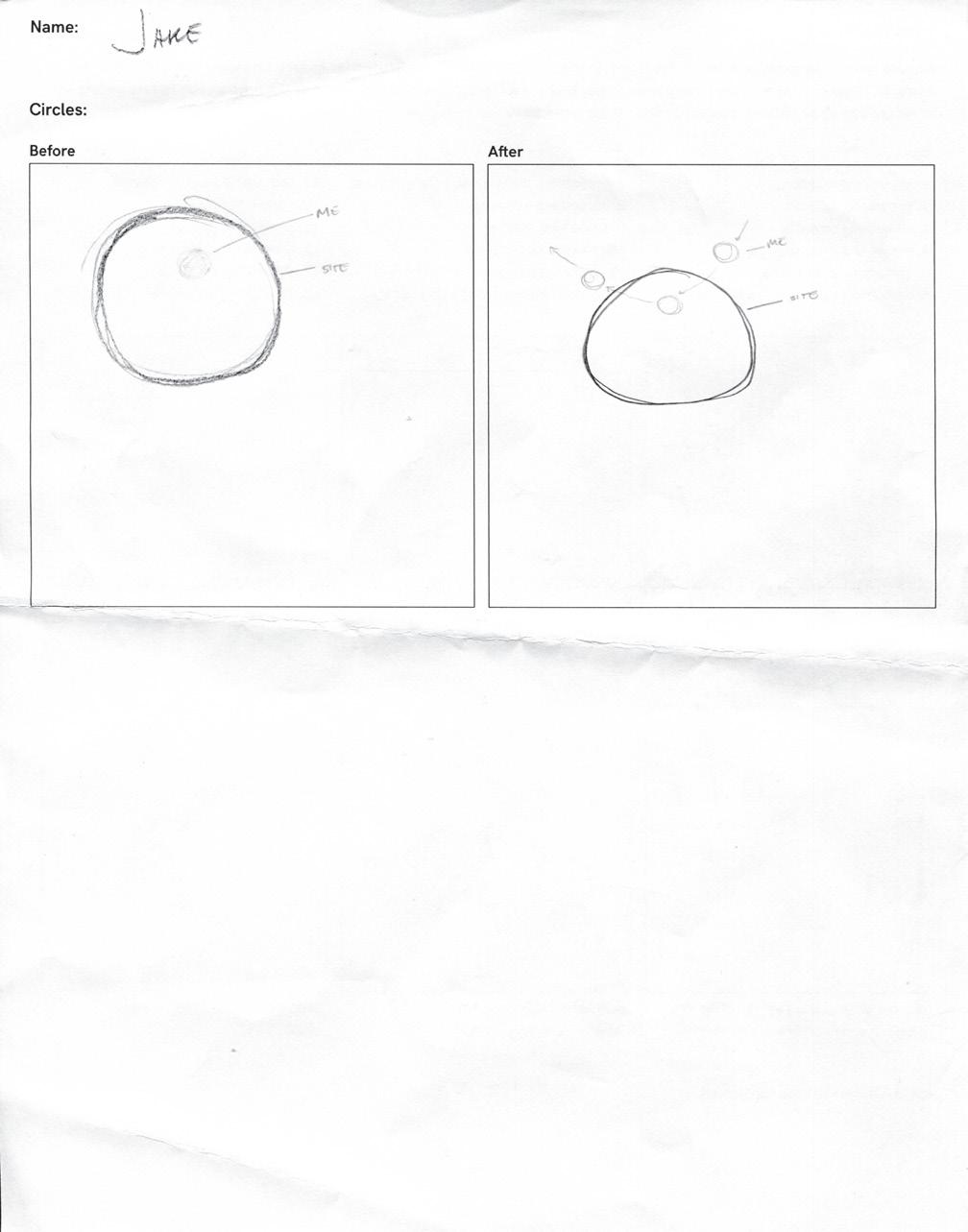

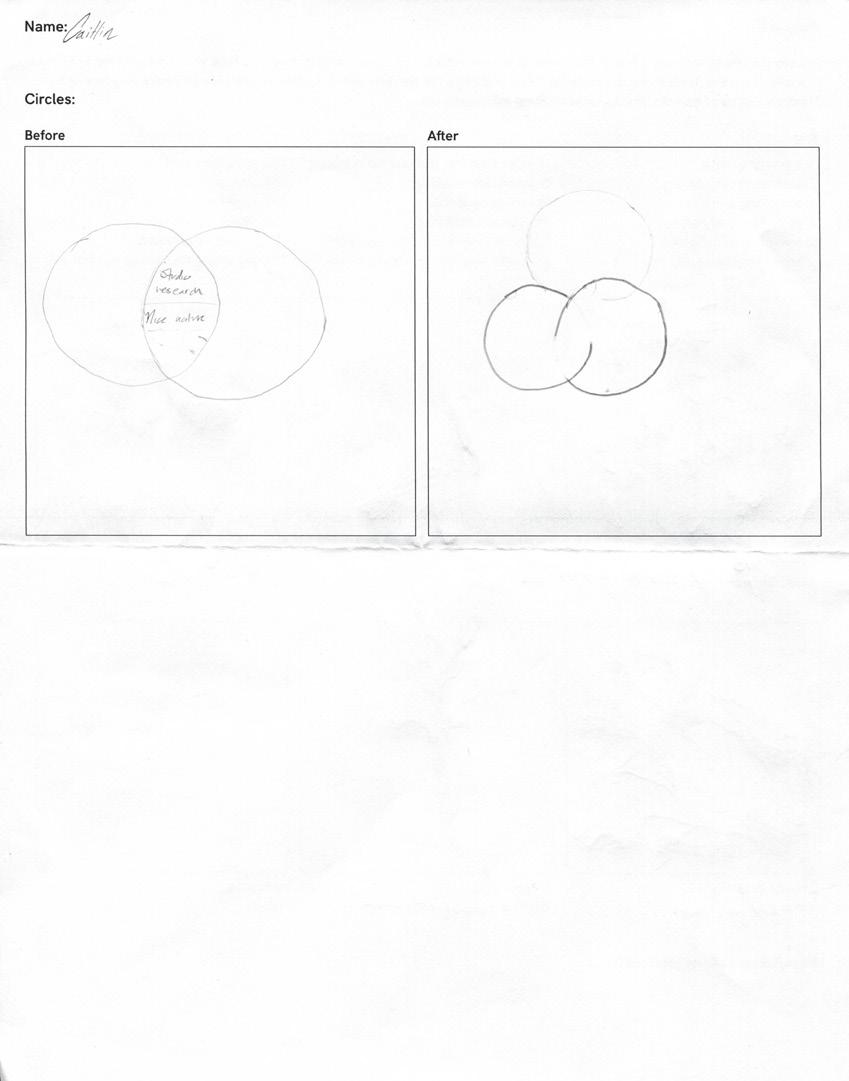

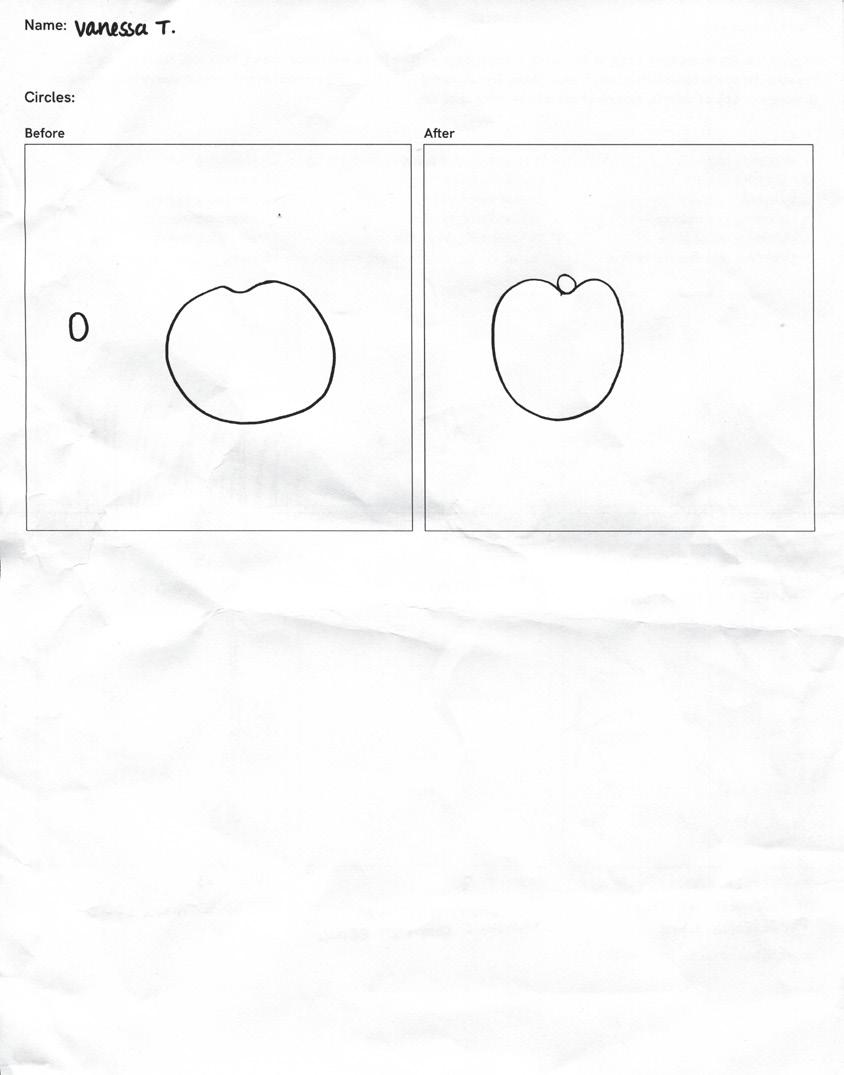

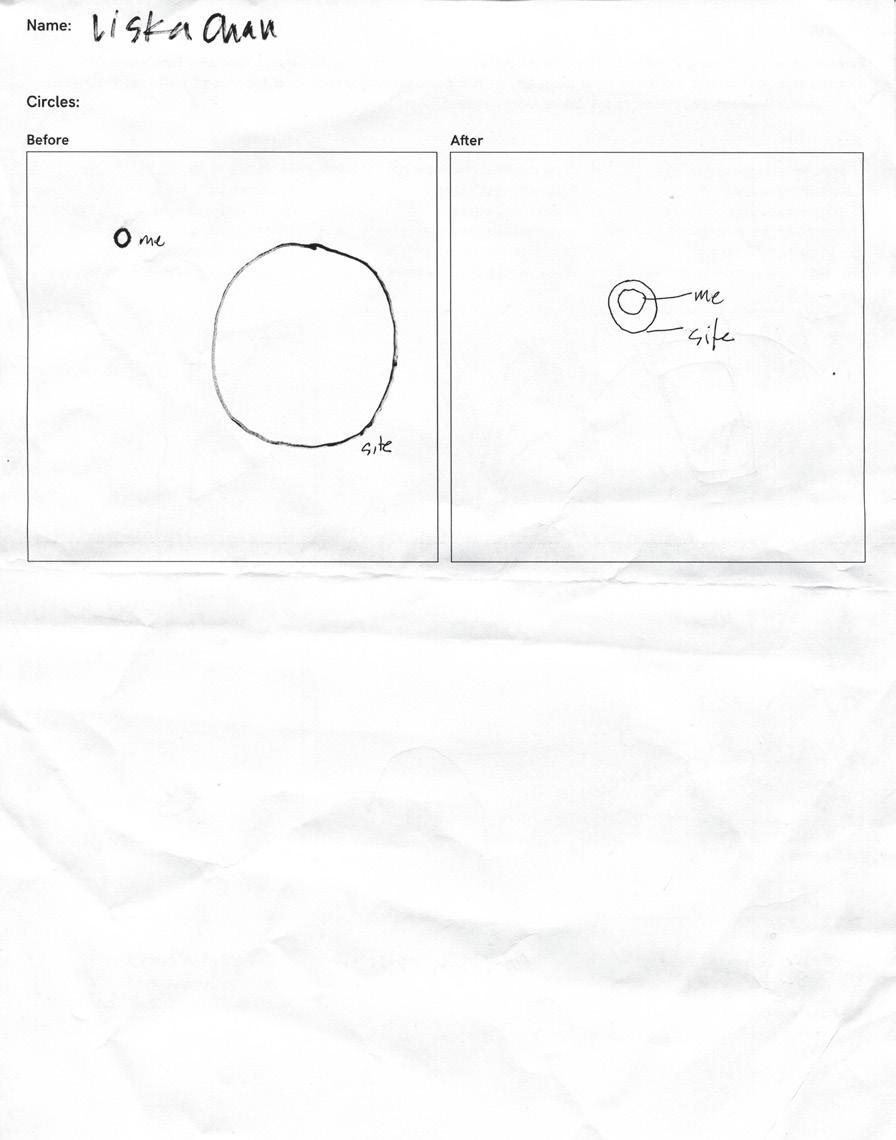

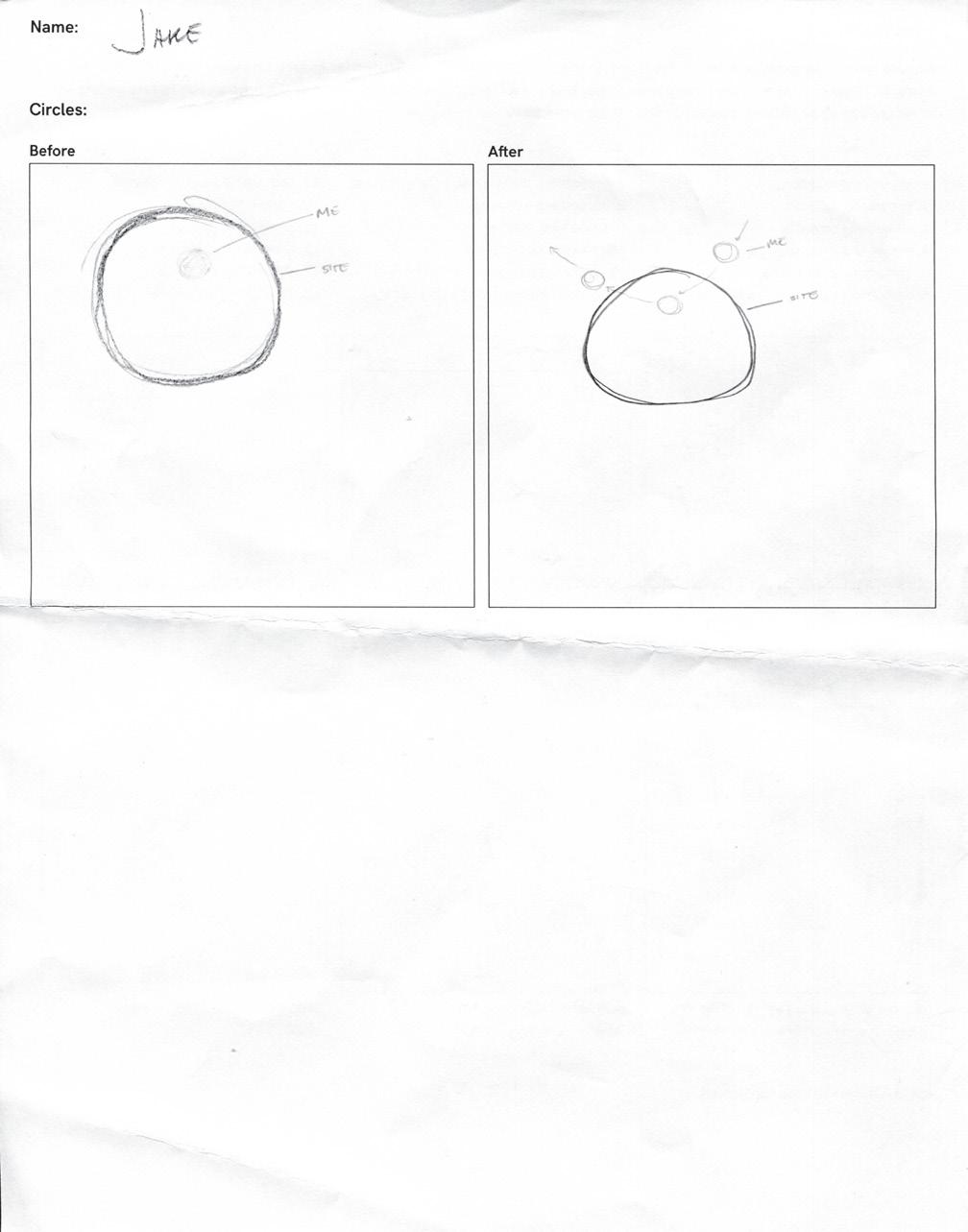

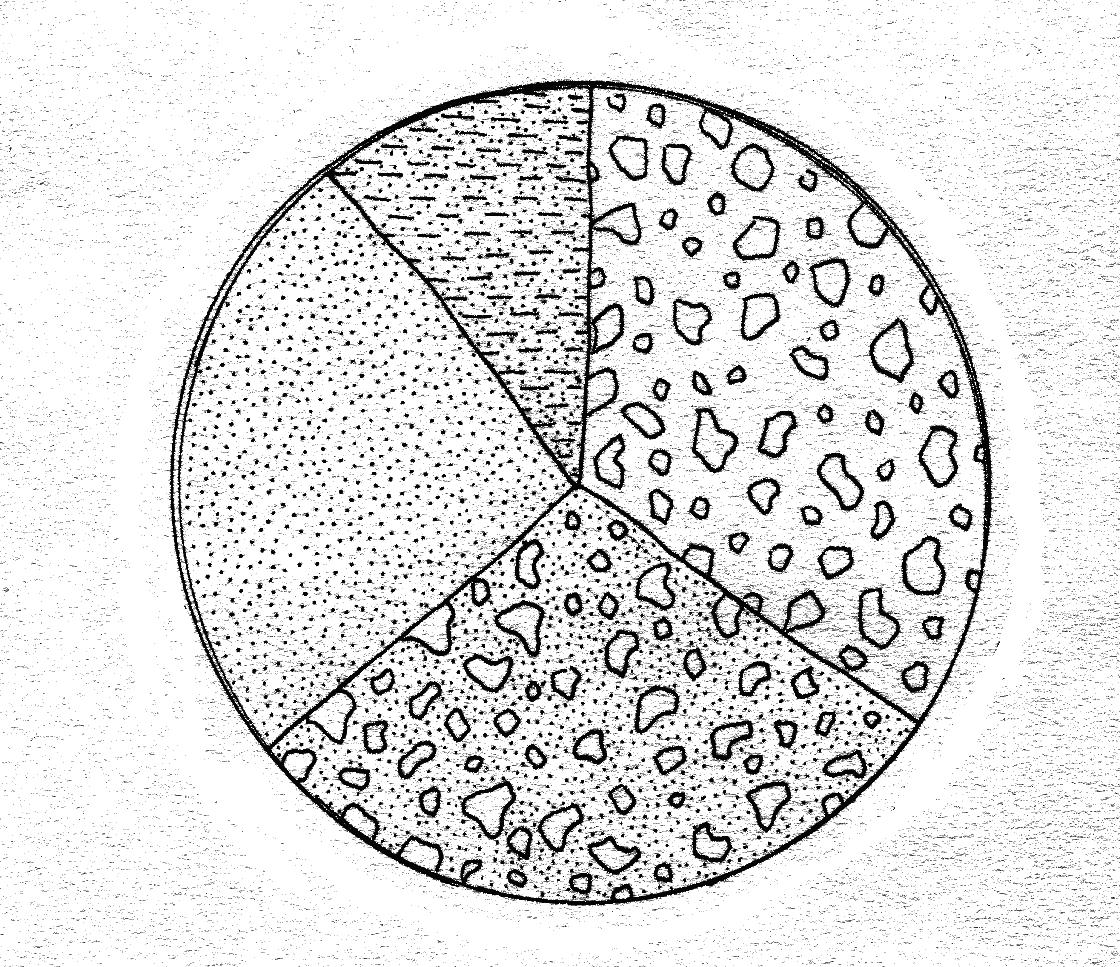

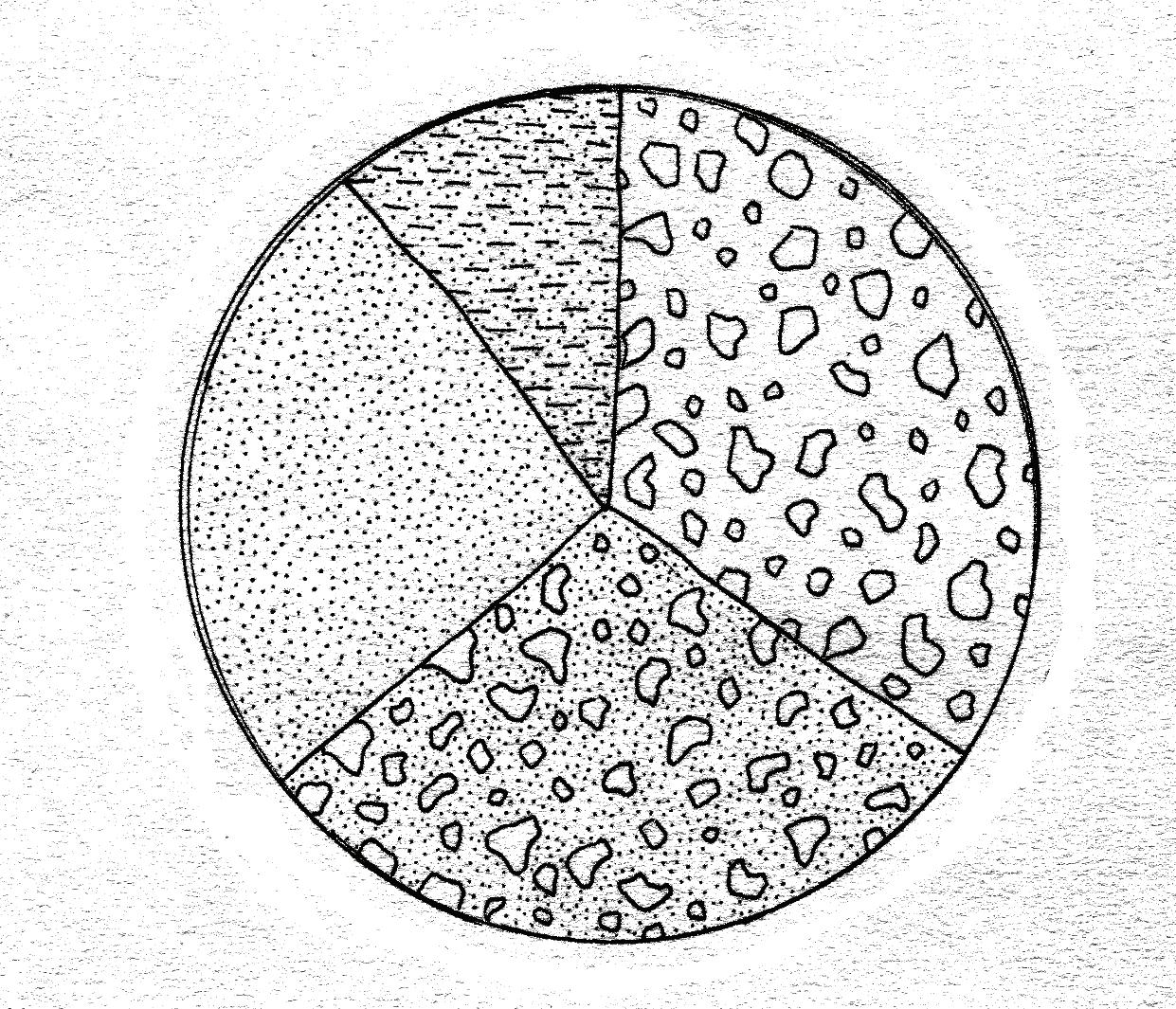

before after What is your relationship to this site?

Assessing relationship to place:

Using two circles, students were asked to visualize their relationship to the site before and after the workshop. Students reflected on a change in their connection with the site after doing exercises.

“[after the workshop], I drew the site as a large dark circle, and me as light cirlces trying to get closer to the site. the more time I spend in this place, the harder it is to know what’s in the center of the circle.”

Student

“the only thing that connects me to these complex dynamics is gravity.”

Nina Elder

“my venn diagram is the same, but the boundaries [between me and the site] are dotted instead of solid.”

Student

Activity adapted from Huiying Ng, “Re-Earthing Through Collective Study”, 2017-2018

desig n o f p r o c e s s oitatilicaf n o f m e t h o d community action research public engagement independent research collaborative research

what next? sharing with public

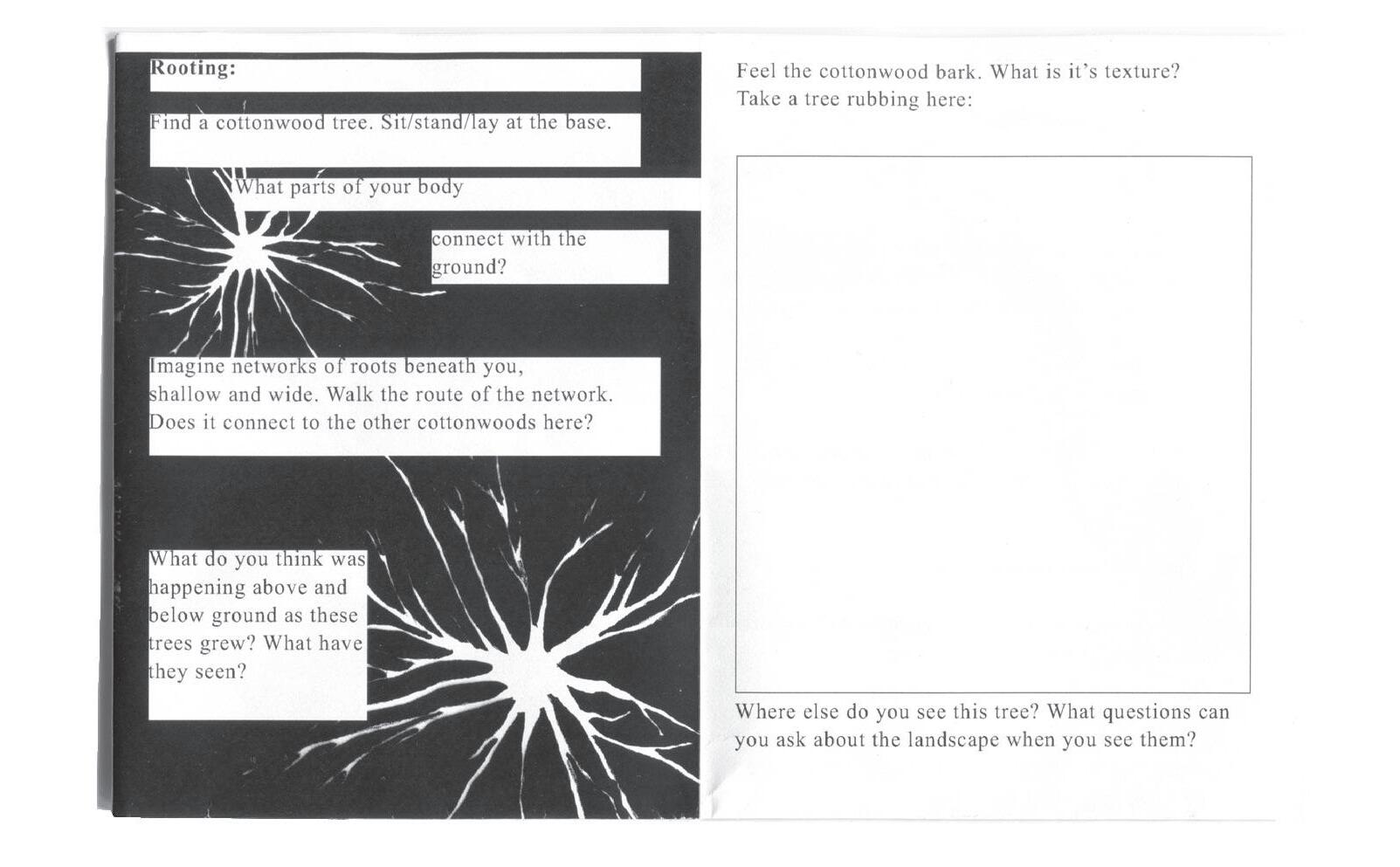

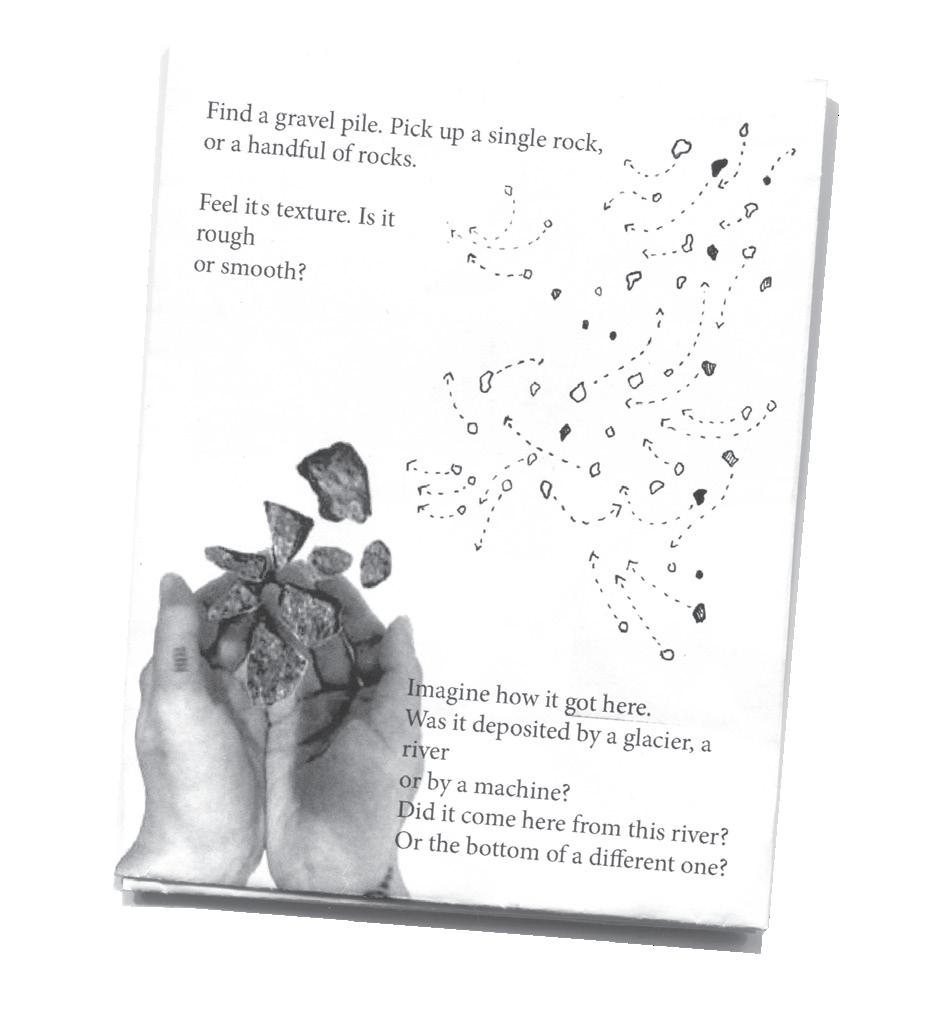

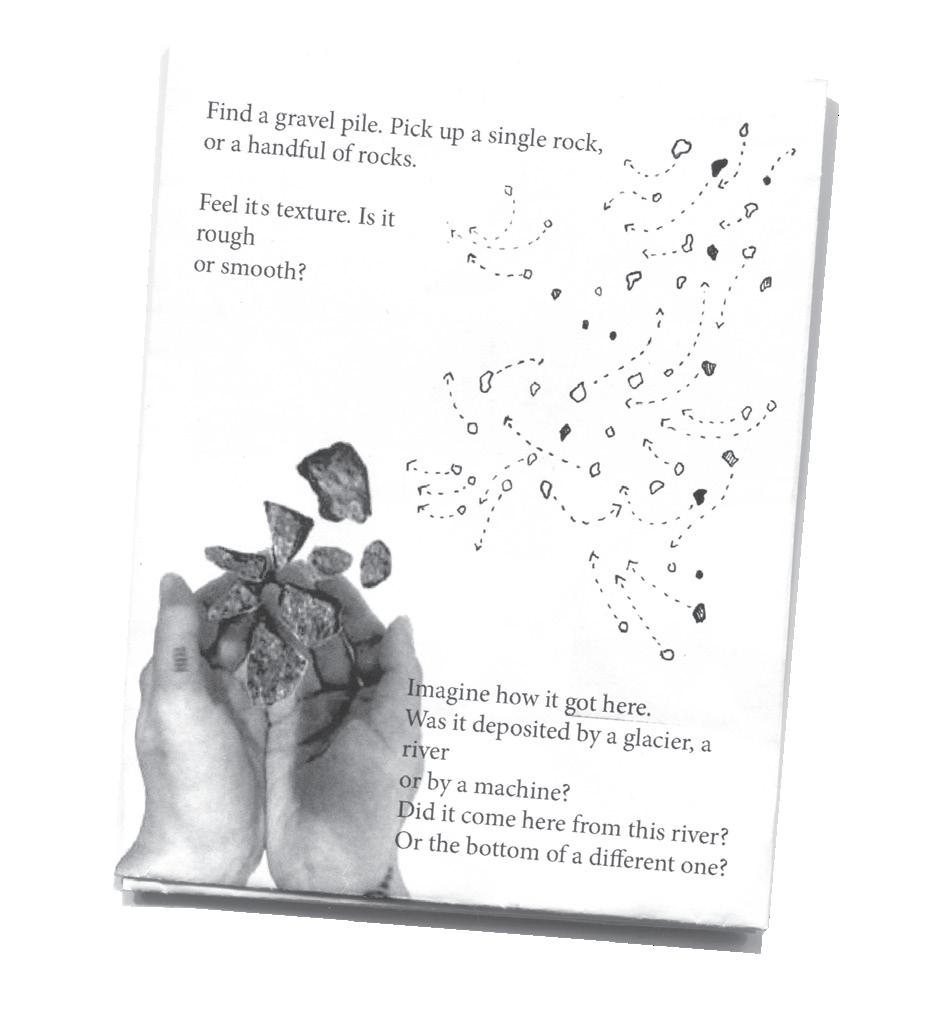

zines prompted engagement with site inspired by workshop

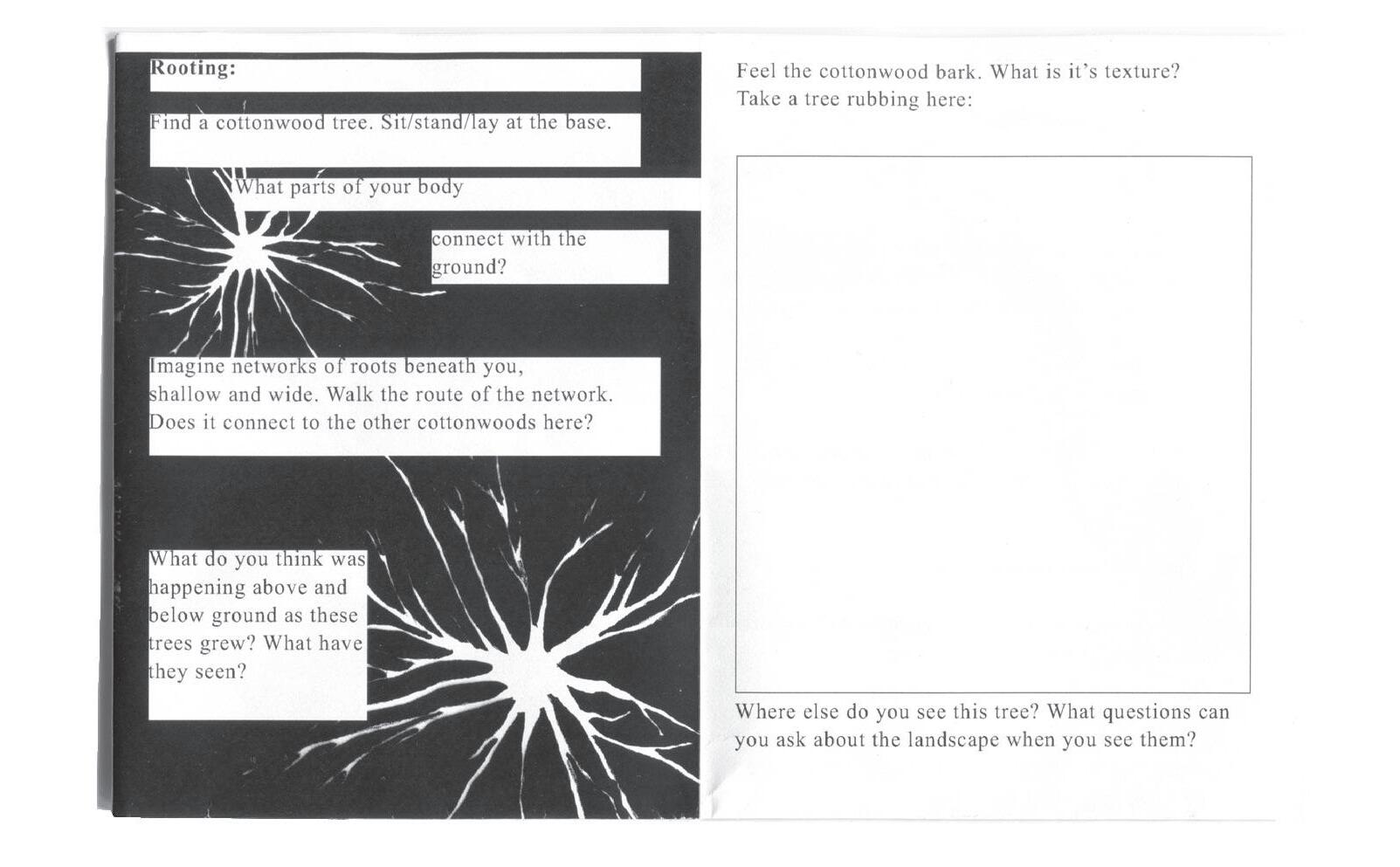

These are an example from a series of zines created out of inspiration from student-generated prompts from the workshop. Each zine contains various invitations for connecting with the site based on specific site-specific themes. The hope is that these zines will act as openings for visitors to the site to learn aspects of site dynamics while using sensory methods of investigation to modify their experiences. The intention is for each zine to be connected to temporary installations, and will change throughout the summer.

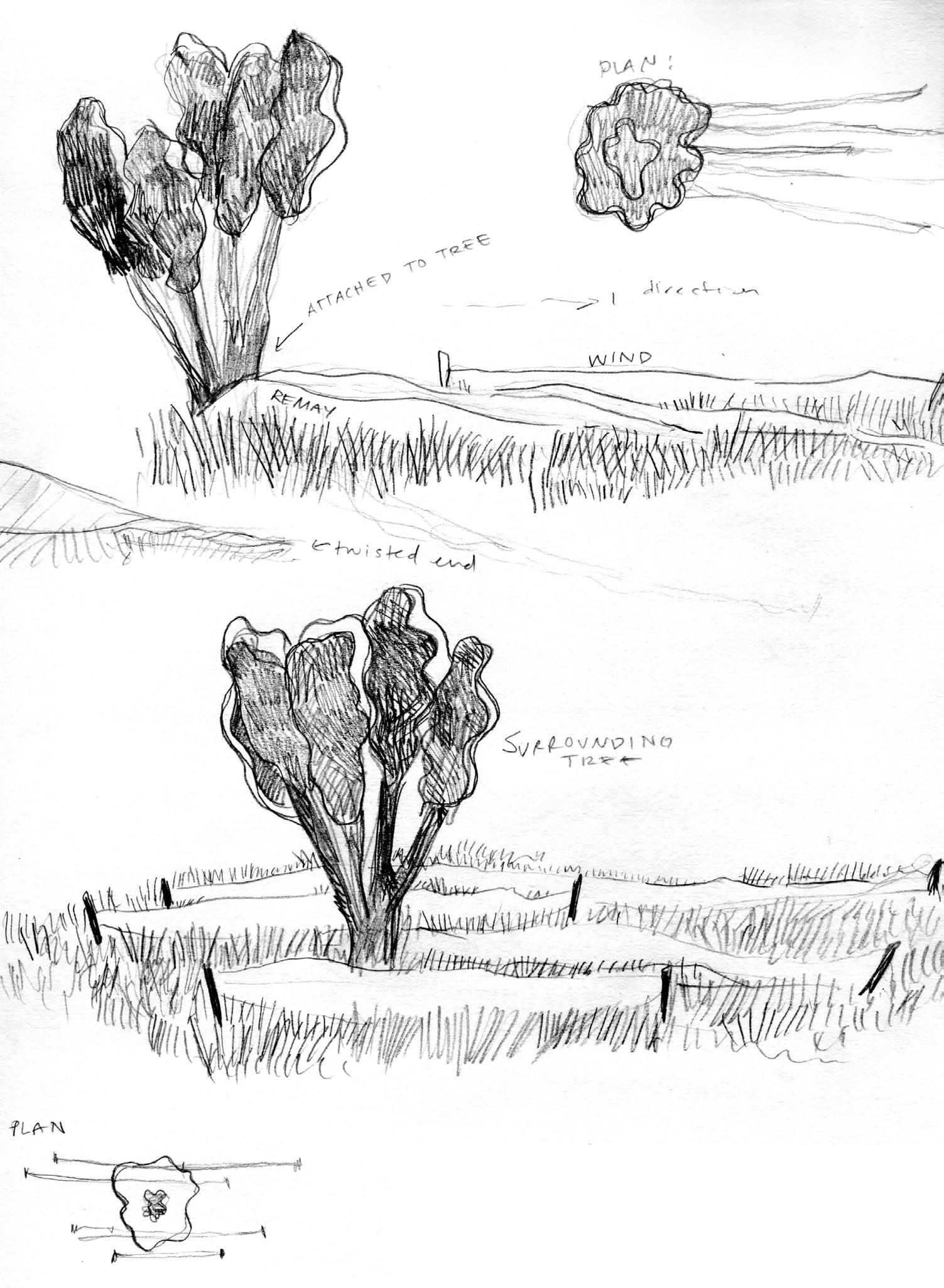

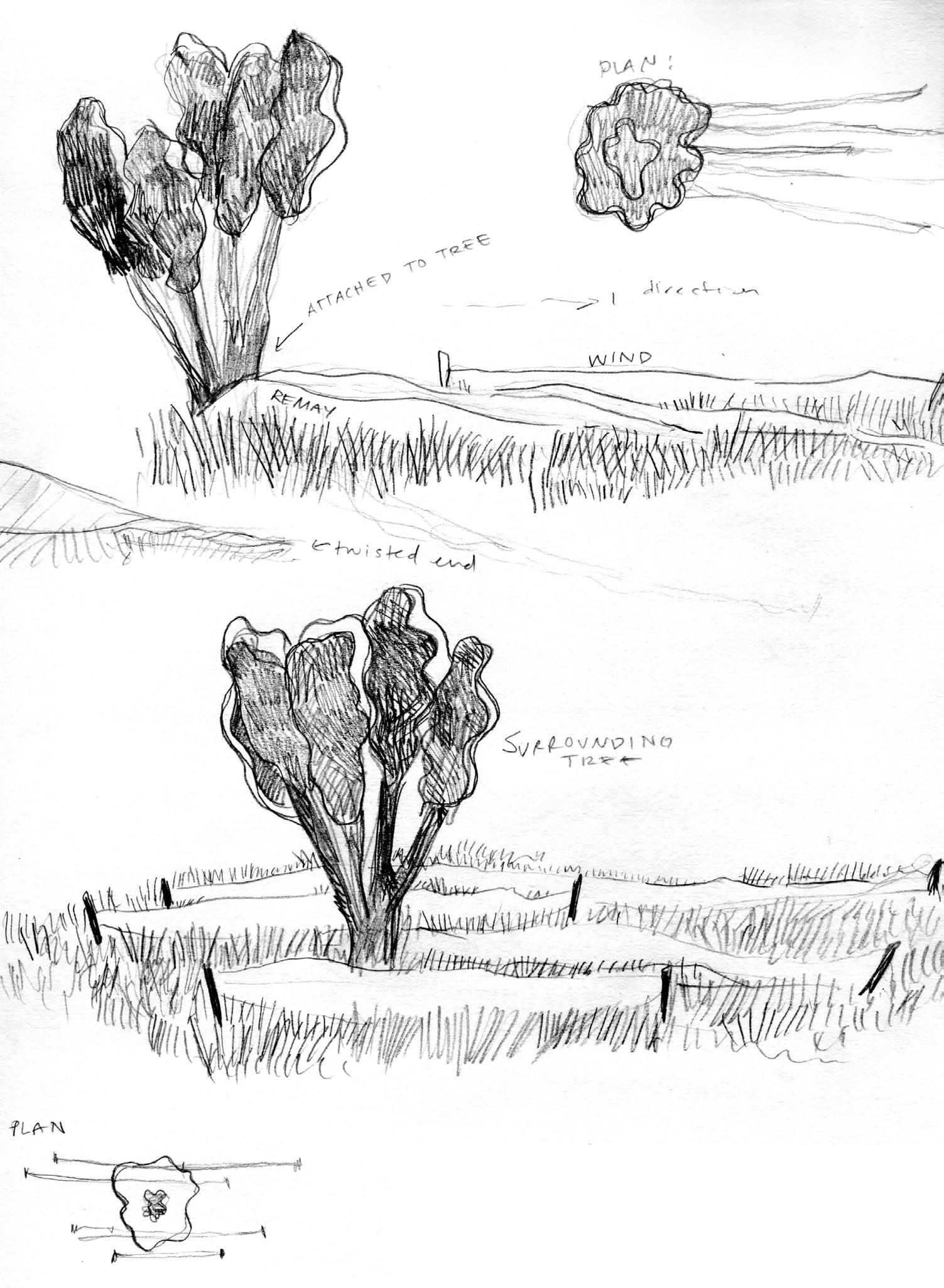

temporary installation tree ghosts

In times before extraction, development, and flood control interrupted this landscape, Black Cottonwoods would have likely rooted after major flood events changed the path of the river, providing conditions for riparian forests to follow. These cottonwoods, however, are the result of post extractive, postdumping disturbance to this landscape. Often referred to as ‘trash trees’, they indicate emergence and survival after violent disruption that prioritized resource over connection. These Cottonwoods can be looked at as past and future ghosts. Their lifespan tells stories of landscape altering events while their presence provides habitat for many species here–and will continue to do so into the future. What can we learn from the cottonwoods?

temporary installation

tree ghosts

appendix supporting works

supporting work 2021-2022

Left page:

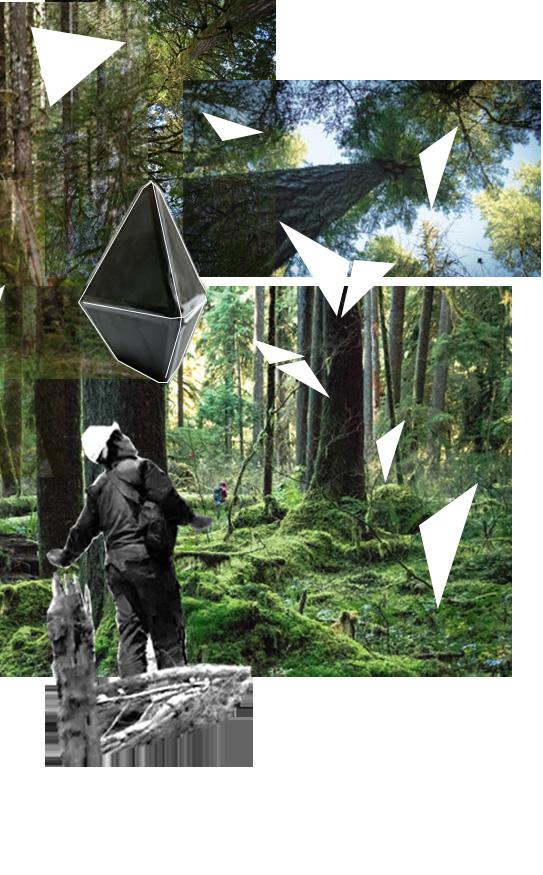

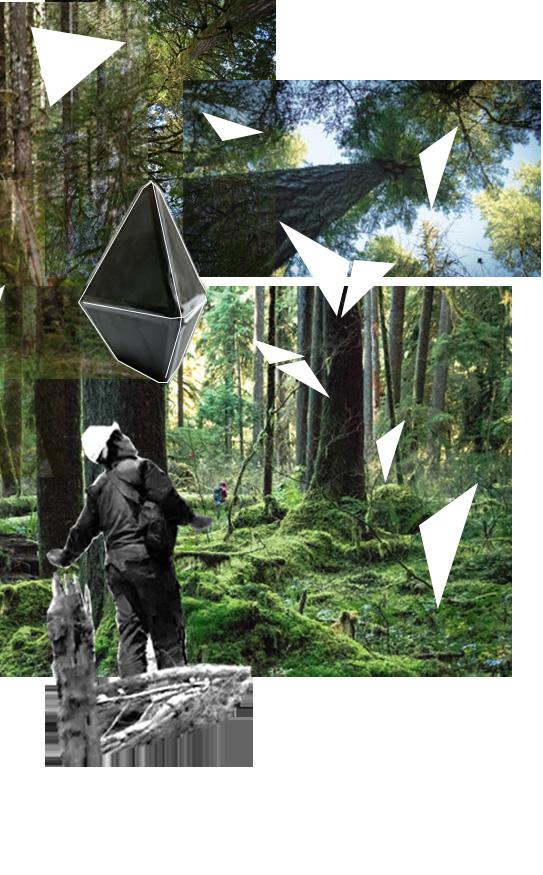

Upper left: Archetypes of Light, collab with Audrey Rycewicz, Summer 2021

Upper Right: Canopy lantern, Fall 2021

Bottom: Memory Cart, collab with Audrey Rycewicz, Fall 2021

Right page:

Hanging Camera Obscura, Fall 2021

readings + inspiration references

Borcila, Rozalinda. Day-Tripping the Petrocapital. Borcila, 2016. https://borcila. com/projects/day-tripping-the-petrocapital/

Burkholder, Sean and Karen Lutsky, “Curious Methods,” Places Journal, May 2017. Accessed Jun 1, 2021. https://doi. org/10.22269/170523.

Elder, Nina. “Non-Linear Research and Quantum Curiosity.” University of New Mexico Deep Time Lab, 2019. https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=knWAAbvdzDE

Griffis, Ryan. “After Extraction: A Partial Political Ecology of Central Illinois.” Anthropocene Curriculum, 2022. https:// www.anthropocene-curriculum.org/project/ after-extraction-a-partical-political-ecologyof-central-illinois.

Griffis, Ryan. “After Extraction: Exercises for Political Ecology Imaginaries.” Anthropocene Curriculum, 2022. https:// www.anthropocene-curriculum.org/project/ after-extraction-a-partical-political-ecologyof-central-illinois.

Holmes, Rob, “The Problem with Solutions,” Places Journal, July 2020. Accessed Sept. 10, 2021. http://doi.org/10.22269/200714

Kimmerer, Robin Wall, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions, 2013.

Lewis, David G. “Kalapuyan Eyewitnesses to the Megaflood in the Wilamette Valley,” Quartux: Journal of Critical Indigenous Anthropology, Apr. 2017. https:// ndnhistoryresearch.com/2017/04/08/ kalapuyan-eyewitnesses-to-the-megafloodin-the-willamette-valley/

Mattern, Shannon, “Methodolotry and the Art of Measure,” Places Journal, Nov.

2013. Accessed Sept. 10, 2021. https://doi. org/10.22269/131105

Mitchell, WJT. Landscape and Power. 2nd ed. University of Chicago, 2002.

Struass, Carolyn F., editor. Slow Spatial Reader: Chronicles of Radical Affection. Astrid Vorstermans & Pia Pol, 2021.

Tuck, Eve, and Ree, C. “A Glossary of Haunting,” Handbook of Autoethnography, edited by Stacey Holman Jones, et al., Left Coast Press, Inc., 2013, pp. 639-65.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt, The Mushroom at the End of the World. Princeton University Press, 2015.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt, et al. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Coolidge, Matthew and Sarah Simmons, editors. Overlook: Exploring the Internal Fringes of America with the Center for Land Use Interpretation. Bellerophon Publications, 2006.

MASAYO + ABBY:

Hi! We are Masayo and Abby, and we are WAIT… slowscapes, a place-based, process-driven research collective. WAIT stands for We Are Investigating Time, and it was created to design an ongoing practice for ourselves.

WAIT...slowscapes: Research Collaborative MASAYO:

The research practices within this collaboration include performance, commitment, and longterm engagement with complicated landscapes. Along with developing a collective practice of active observation, we also center playful and celebratory acts of care to bring visibility to our own impact on the site.

WAIT aims to expand upon the design process, asking how designers could allocate more creative resources into analysis and maintenance. To study this, we asked what would happen if we instead designed processes that centered land care by focusing on forming intimate connections with the landscape through creative fieldwork, and framing maintenance as an artistic act.

This presentation shares a series of sub-projects that emerged from the questions above. While we each investigated individual components during this project, we see each project as a smaller component that reinforces WAIT as a whole.

Shared Interests

ABBY:

We decided that our efforts would be strongest as a collaboration when we discovered that our interests overlapped. Plus, after two years of remote learning, we wanted to develop a communal practice of researching, processing findings, and designing outcomes. We also felt a need to prepare for a future practice by working with landscape, in the landscape. As we talked through our ideas, it became apparent that the

Introduction:

WAIT...slowscapes Presentation Script Collaborative presentation of projects + site walk June 4, 2020

themes we were both exploring were very similar. Those themes are:

Care Commitment Collaboration Connection Creativity

In the following projects, we will introduce our independent research interests in more detail, and how they intertwine with each other.

We decided to take this opportunity to be messy all the way through till the end. By not treating landscape as a problem to be solved with neatly packaged design ‘solutions’, we were free to let connections emerge.

Masayo’s Interests MASAYO:

Through this project, I am weaving together three topics of interest:

1. I am interested in developing a process that uses art and creative fieldwork as a means to center intimate connection with landscape as a research and design practice. This includes highlighting sensory knowledge and personal experience as critical parts of site analysis.

2. I’m looking for ways to create an inclusive practice where the research phase involves facilitating dynamic experiences for and with others.

3. I am interested in investigating methods for landscape interpretation that acknowledge the complexities of post-extraction landscapes, while creating openings for reparative connection?

My interests draw inspiration from Karen Lutsky and Sean Burkholder’s article, Curious Methods. Their process of landscape interpretation examines the lost complexities in documenting living landscapes through maps and historic surveys. They create their own non-solutionist investigation of engaging with landscape through experience-based stages that they name as inquiry, insight, and impression.

Inquiry is the process of asking questions through quick, physical interventions on the landscape.

Insight is the feedback they gain from these experiences.

Impressions are recorded quickly, with the knowledge that these will constantly change.

I used this open-ended framework as a guiding practice during my process, which led to emergent connections and many rabbit holes that allowed for constant shifts within the shape of this project.

Abby’s Interests

ABBY:

My interests involve exploring the intersection of art and landcare with an eye toward promoting greater understanding about the impacts of landscape standards on ecological function and social needs.

For this project, I was inspired by the work of the artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who has been the maintenance artist in residence with the New York Sanitation Department for 40+ years. Ukeles’ work to explore and expose the

complexity and nature of maintenance and the lived experience of the people that do maintenance work is unparalleled. As a framework for this project, four typologies of maintenance art are identified through Ukeles’ work: interaction, performance, documentation, and exhibition.

The guiding question for this project has been: How can the Ukeles model of maintenance artist in residence be applied within landscapes?

Studying land care in this way will hopefully lead to understanding its potential as a socially engaged, multi-disciplinary creative practice. A Maintenance-Artist-in-Residence can act as a living link between designer and caregiver and community, increasing visibility and respect for land care, the labor it involves, and the creative potential it holds.

So, now that we’ve given you a bit of background on our focus, we are going to move a bit further into the site.

ABBY:

We were also struck by the impressions of the site. It didn’t seem to generate a lot of interest, and was the victim of many negative impressions. The large zone of disturbance from the recent construction of the bike path and water easement did nothing to help these impressions. On these pages are some people’s responses to the site and as you can see, they are less than glowing.

Despite these impressions, the site is full of complexities and hidden histories, so we’ll zoom out a bit to give you some context before we dive into our projects.

Industrial Aftermath

ABBY:

In the last 200 years, massive changes caused by dispossession, extraction, and landfill drastically altered the landform, soil structure, and ecological relationships of this place. What we see here today looks and functions very differently from what was here prior to settler colonialism.

Site Impressions

MASAYO

We chose to work on this site for several reasons. Field work was central to our project, and it was easy to get here. There was also landcare research already happening there: Michael’s field experiments in parametric mowing. It is also a disturbed site with novel ecosystems that are representative of many highly impacted urban landscapes that are frequently undervalued and overlooked.

Time + Scale

MASAYO:

This timeline shows the relative scale of events that shaped this landscape. It’s important to note that the records that are most often available in landscape research are from the period after white settlers colonized this area, from 1850 to present-day.

ABBY:

We would be remiss not to acknowledge that the Kalapuya are the first maintainers, artists, and residents of this land. Our practices here are not new or revolutionary but rather

an attempt to develop a reciprocal relationship with place.

Additionally, there is a lot of previous scholarship and art that inspired us to look deeply into land care, slow research, and sensory connection with place. We do not have time to go into these topics in depth, but have references to check out in our individual booklets.

I was particularly looking for ways that my body and sensory ways of knowing responded to following my curiosity, and then how these ways of knowing led to an understanding of place that spans outside of the logic of maps, surveys, and historic photographs of the area. Following Curious Methods, I used different methods to record these transects; through photographs, collage, making sensory instruments, and recording sound.

Points of Entry

ABBY:

With these layers of complexity in mind, how does one person start to build a caring relationship with a place? To do this, we each had entry point actions that got us connected to the site at the start and represented the commitment we made to get to know it.

On the right side is a map of the 15 photo points I set up around the Land Lab. Starting in early January, I committed to photographing them weekly. This idea came about by combining a guide to photopoint monitoring and the Ukeles’ documentation typology. It became a weekly ritual, rain or shine (or hail), creating a structure for my commitment to this place. This ritual became something I looked forward to as a quiet practice of sensory connection. The images that were created recorded the changes over time due to ecological and maintenance processes at play here. I have an example of one set of photo point images to share.

MASAYO:

I walked the same transect weekly, starting south from the train tracks, heading north through the field, the cottonwoods, and finally the riverbank.

Through this continual investigation, I realized that the whole story of this site could be told through one transect. I began to wonder how this way of storytelling could be expanded into other elements on this site; the pieces of gravel, the blackberry, the red tail hawk.

Uniforms

ABBY:

We wanted another way of communicating that in our research process, we were changing the site and also becoming part of it. We decided to wear uniforms when on the site as a representation of our commitment to this practice and a communication device that increased the visibility of our presence and impact. We chose these white coveralls because they would show dirt and grass stains, and highlight the passage of time through the materials of the place. There is also a performance aspect – we are highly visible when wearing these and passersby are more likely to interact with us. (Of course, this also relates to the Ukeles performance typology)

Seeding + Fencing

ABBY:

Following the construction of the water easement, the area through the center was very disturbed and compacted. It had been seeded in the fall but that seeding had failed, so we adopted it. Michael chose a seed mixture of pollinator-friendly native annuals and perennials with the help of Bart Johnson and Bitty Roy, and we spread that in February of this year. We also seeded along the pathway and this section here shows some of the plants we seeded: lupines, tarweed, gilia, for example.

After seeding, we constructed the fence with the idea that it would help germination in the easement by keeping the geese from browsing. We sought to explore the creative potential and aesthetic properties of common landscape materials such as t-posts, temporary fencing and row cover fabric. The construction involved a collaborative process, and required maintenance and adaptation along the way.

Masayo’s Workshop: Sensing Time

MASAYO:

I created a short workshop in collaboration with Nina Elder, an interdisciplinary artist. Her work examines how our lives are entangled with ghosts of mines, gravel, and glaciers–appropriate for this former gravel quarry.

We worked with Liska’s transpecies design class.The main goal of the workshop was to facilitate an experience for collaborative sensory investigation grounded in our connections with the site across space and time. The workshop was divided into three sections:

• Grounding exercise

• Sensory prompt exercise

• Students create prompts, trade, and perform them.

Community Interactions

ABBY:

Throughout the time we were working out here, we had many interactions with the people, animals, and birds that are on this site. These spontaneous interactions were generative and informed our next phase of this project. In this next section, we will both share the intentional interactive projects we did.

As a debrief, students diagramed their relationship to the site before and after the exercises. The diagrams and our final discussion showed many changes in perception of the site after we had created space for deep engagement. Some felt more a part of the landscape, while others felt that the complex dynamics that emerged as they learned more about the site made them realize how much they would never know.

This experience reflected that creative fieldwork in the form of workshops creates an opportunity for inclusive, visible, and experiential forms of site analysis.

I synthesized student experiences, prompts, and reflections into categories that could create engaging site interpretation for future experiences and installations.

1. Activate imagination: imagination allows access to abstract concepts/ timescales about place

2. Foster creative forms of embodied and sensory inquiry: creating space for novel experiences helps people make new connections

3. Create open-ended invitations for attention, curiosity, and participation: deep attention to place is an opening for creating a relationship of intimacy and care.

Now we will transition to the interactions embedded in Abby’s project.

Abby’s Crew Interviews

ABBY:

Taking cues from the interaction typology, four members of the University grounds maintenance crew allowed me to ride along with them and talk about labor and land care. Through these rides they showed me the areas that they are responsible for. It should be noted that Nick is the only crew member whose area includes the waterfront, and as you can imagine that is a huge task for a single person.

Though it was my intention to let the conversation flow, I had prepared a few questions:

How would you describe your work/ what do you call your position?

What do you wish those who design landscapes knew about maintenance?

Which areas are harder or easier to maintain and why?

Do you feel your work allows you to be creative?

Recurrent themes from these conversations fell into four categories: Access, Materials, Time, and Relationship, and I think these are essential for developing a carecentered landscape practice.

Access specifically relates to the ability to get in and care for a place. Quite simply, if someone cannot readily access a space with the necessary tools, it is harder for them to care for it. But access can also relate to other barriers to care beyond just the physical: there can be political, social and cultural barriers.

Materials are the stuff of landscape: soil, plants, hardscaping, but also the temporary, intermittent things that come in from construction or installation. When these items are selected there is the hope that they would be chosen with the intention that they be long lasting and site appropriate. Unfortunately, that is not always the case, and the crews have to deal with the consequences.

Time is a constant in the landscape. Anyone who actively works within landscapes understands that they are working with and within time.

Finally, relationship: too often those who are designing landscapes have little contact with those who tend to landscapes. This is unfortunate because the people caring for landscapes have a unique and valuable perspective on the realities of a place. Collaborating with them will help to ensure that long-term thinking and reciprocal practices are honored.

Temporary Installation

Prototypes

ABBY:

We have been spending the last two weeks prototyping (materials? ideas?) for temporary installations that are the result of spending so much time getting to know this place and its inhabitants.

MASAYO:

I’m currently in the process of exploring prototypes for a sitespecific temporary installation that highlights the black cottonwoods here. I became inspired by the presence of the cottonwoods after seeing how students engaged with them during the workshop. Black Cottonwoods are dynamic, charismatic, and engaging, and are also indicators of ecosystems that emerge from disturbance. The installation is accompanied by a zine that contains prompts inspired or developed by students from Liska’s class as a way to facilitate openings for relational connections with these trees and the site.

I’m using crop protection fabric (reemay) as a part of the material palette that we developed early on in this project as a way to draw attention and curiosity to the tree to cue visitors into the narrative of the site. These cottonwoods can be looked at as past and future ghosts. Their presence tell stories of landscape altering events, while providing habitat for many species here–and will continue to do so into the future. The cottonwoods highlighted here are on their way to becoming future snags.

Prototyping this installation has acted as a research tool of site dynamics in its own right–due to weather patterns, the site has been entirely different

each day I’ve worked out here. 18 mph winds left the grasses trampled. On calm days, the fabric falls flat, on windy days it is wild.

ABBY:

Throughout our time working on the site, we would frequently see and hear killdeer. The turning point came when I almost stepped on an egg, so well camouflaged in the gravelly, scrappy soil in the easement. Those of you who know killdeer will understand that this was a perfect place for them to nest - they prefer low vegetation and can often be found nesting in low fields and even parking lots. I began paying attention to the places around the riverfront where they were most often seen and it was all the compacted gravelly spots from the construction and the construction vehicles. What is desirable to a killdeer is undesirable to humans…unless those humans were parking, or driving, or doing donuts. Even in our land care efforts, we were disturbing them by walking too close or too frequently. So, I started thinking about ways to communicate the importance of what was happening in these places, and how to add some protection for the killdeer nesting areas. After reading some studies about experiments with exclosures for ground nesting birds, I found several on plovers and one specifically on killdeer. From these, I chose three examples and decided to expand upon the forms they used to build these prototypes. The killdeer nesting season is nearly over and they have moved on to the pole yard, but I am hoping that these prototypes may inform some future action to protect ground nesting birds here.

Reflections

MASAYO + ABBY:

Even though we’ve presented these projects individually, it should be noted that we’ve helped and supported each other every step of the way–through building installations, prototyping, ideation and talking through challenges. That was a crucial part of this whole process for both of us, especially within the challenges of creating a process-driven design project. Our conversations were generative, and the affirmation that we got from them encouraged creativity and exploration.

Additionally, we found that a lot of our methods for bringing visibility to most of our processes created an inclusive structure for working with outside groups. Designing creative forms of active community engagement inspired multidisciplinary pollination that we both want to continue to work with in the future.

Most of all, what surprised us about this process is how much we both fell in love with the site. We started out ambivalent, and at some point, started to really look forward to our time together here. Leaving space for open-ended investigations of the site was what allowed for that connective relationship to occur–neither of us were looking for specific things, nor had a specific objective for approaching this place when we started out, and so we ended up developing a relationship.

As a collective, we hope that these projects will continue to inform a carecentered approach to this landscape, as well as other landscapes that we work with in the future. We hope that these processes can be inspiring for other landscape architects – to not necessarily replicate – but to look for their own openings to invite this type of long-term engagement into their practices.

4.

3.Annette Baldeff, et al. Despite Dispossession

4. Nina Elder

3. Annette Baldeff, et al.

4.

3.Annette Baldeff, et al. Despite Dispossession

4. Nina Elder

3. Annette Baldeff, et al.

Above: worksheet recordings by year 1 MLA student, Tristan Matlock

Above: worksheet recordings by year 1 MLA student, Tristan Matlock

Above: Students investigate place through sensory prompts

Above: Students investigate place through sensory prompts