4 minute read

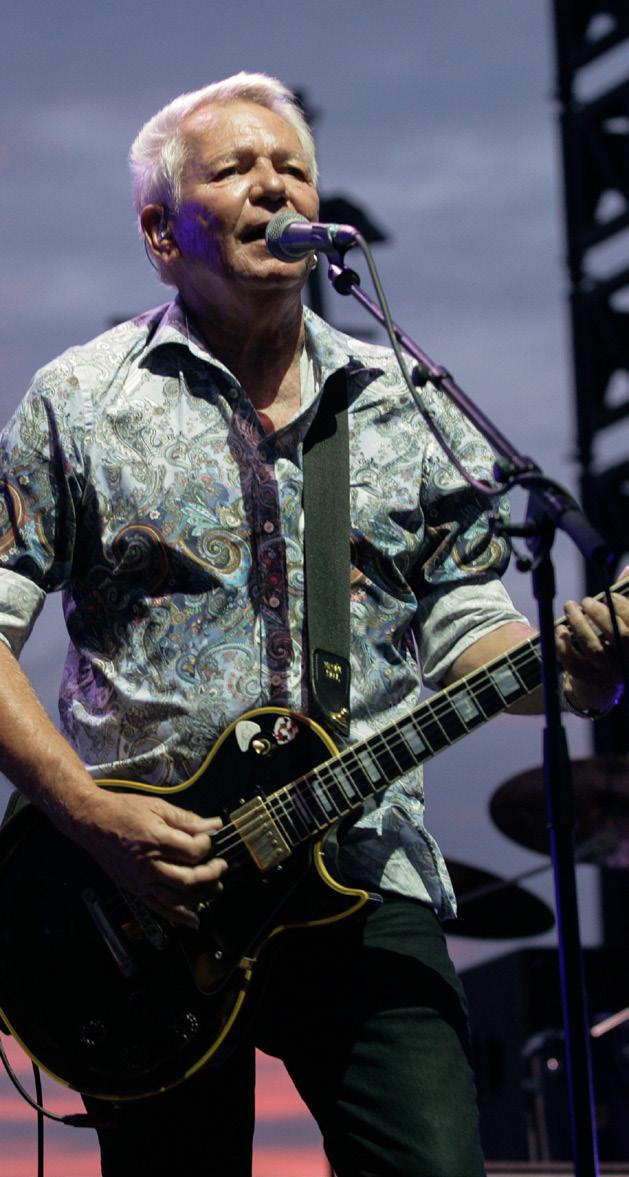

ICEHOUSE

from Beat 1704

by Furst Media

“I never understood the way people reacted to Great Southern Land and I probably still don’t – it was a kind of magic that everyone but me heard.”

Speaking from his home in Sydney’s Whale Beach, Icehouse frontman Iva Davies seems surprisingly avuncular for an Australian music legend who toured with David Bowie.

Advertisement

Icehouse is coming to Melbourne’s Sidney Myer Music Bowl on Saturday, February 11 to celebrate 40 years since the release of the single Great Southern Land; an enduring centrepiece of Australian national identity and music culture.

For Davies, the mastermind behind Icehouse, the story starts in the small New South Wales town of Wauchope, where his early musical influences saw him on a trajectory to be playing to a much different tune.

“Classical music was a complete accident at both ends – getting in and getting out,” he says. “When I was about four-years-old, there was a parade going on in town and I heard this extraordinary sound approaching. It turned out to be the local Scottish pipe band. Believe it or not, I fell in love with the bagpipes – so much so that I pestered my parents to let me learn.”

After a high school music teacher encouraged him to play something more practical, he transferred to the oboe.

“Apparently, I became very good at it because I won a scholarship to the New South Wales Conservatorium of Music and became the principal oboist of the ABC National Training Orchestra,” he says.

Although the band was fun, it wasn’t exactly profitable. Davies even debated ending the band before they struck gold with the single Can’t Help Myself.

“I made a bet with one of our record label owners that we wouldn’t get into the top 40,” says Davies. “I lost that bet.”

Upon returning from tour, Davies was under immense pressure to produce a second album. The inspiration for Great Southern Land came on Icehouse’s first international tour, inspired by homesickness and awe at having flown over Australia’s red centre enroute to London.

“I was staring out the window for a while, looking down at the outback; dried-up creek beds and not a lot to look at,” he continues. “I went to sleep and many hours later I looked out the window and it was exactly the same. It was a real light-bulb moment for me.”

In 1982, Icehouse released Great Southern Land as a lead single for their sophomore album Primitive Man.

While it didn’t enjoy the chart success as other Icehouse hits, it has a uniquely enduring quality. Having had Qantas Dreamliner’s named after it, the Australian cricket team use it as their walk-out song, and an orchestral version played at the Sydney Opera House to ring in the new millennium, the song continues to embed itself in Australia’s lifeblood.

“I played Great Southern Land to the studio as my first song of ten to show that I was getting to work and everything was underway,” he says. “The studio reacted straight away and knew we had something.”

Words by Coco Veldkamp

In a twist of fate, his oboe career would quickly dissipate after a repair gone wrong ruined his instrument. Finding himself unemployed and struggling for rent, he began working two cleaning jobs. This is how he met Keith Welsh. Welsh was the son of Davies’ manager and played bass, while Davies had been teaching himself guitar. The two co-founded the band then known as Flowers in 1977.

They bonded over a similar taste in music. During their pub circuit era, they played covers of T.Rex, David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Lou Reed and Brian Eno.

“At the start, Keith went around to pubs asking if we could play there on a Friday night,” Davies says. “Our first show was in a pub that had never had a band play before, so we just set up in the corner. It was very DIY.”

Icehouse is playing Sidney Myer Music Bowl on February 11 as part of Arts Centre Melbourne’s Live at the Bowl program. Beat is an official media partner of Live at the Bowl.

A celebration of Afro-Colombian music is the essence of picó culture as it exists in downtown neighbourhoods of cities on the Caribbean coast. But Melbourne-based picó collective El Gran Mono is proving it’s about more than just the music.

The group is creating a diverse cultural community of music-makers and selectors, hosts, dancers, artists and designers and of course fans, who become immersed in its live-show experiences. But first, what do you need to know about picós?

They are huge technicolour (often fluorescent) sound systems that are custom-built to blast out vinyl records of predominantly AfroColombian music. They are culture unto themselves, dominating the streets of Colombian cities like Barranquilla, Cartagena and Santa Marta where crowds gather around them to connect, eat, socialise and of course, dance.

Thanks to El Gran Mono founders Tom Noonan and Johnny El P, Melbourne has had its very own picó since 2018 – EL GRAN MONO – the first to be built outside Colombia. Noonan, who was living in East Africa in 2013, visited Barranquilla and connected with members of the city’s local music industry who introduced him to picó culture, which was vastly different from his experience of sound systems in Australia.

Their imposing size and sound, their art and psychedelic colours, and the atmosphere they created at Barranquilla’s picó parties captivated Noonan, and he reflects on being “completely overwhelmed” by the energy and social connections that were forged around them.

“I came back to Australia feeling really inspired to explore a similar project here; a cultural exchange between Colombia and Australia through music and other performance elements. The project was a way of reinforcing positive narratives around sound system culture,” he says.

Noonan worked closely with a picó crew he met in Barranquilla to create a Melbourne-based sound system and surrounding community that authentically reflected Colombia’s music culture. In 2018. he and Johnny El P oversaw the creation of EL GRAN MONO (which literally translates to The Great Monkey) in Melbourne, a sound system giant measuring over three metres high. Even by Columbian standards, it’s big. Picture a fierce, King Kong-like ape atop Flinders Street Station, with vinyl recordings flying through the sky and