Comparing apples to oranges: social sustainability in the Global North and Global South

GCM Pekelharing School of Geo and Spatial Sciences Unit for Environmental Sciences and Management

North-West University

Abstract

Globally, the current generation is bound to experience a social catastrophe unless social sustainability is taken seriously and context-based solutions are rapidly applied. Global North and Global South social sustainability and Planning frameworks often highlight similar themes, indicating a universal and generic application of social sustainability, worldwide. However, frameworks seldom address the practical application according to unique Global North and Global South planning contexts. This research article highlights the importance of the unique application of social sustainability and Planning themes in the Global North and Global South, due to their different, local contexts. A thematic and content analysis are qualitatively applied throughout the literature study to highlight various social sustainability and Planning themes, expressed in the form of a selective coding matrix. The empirical study undertakes a comparative case study analysis between Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and Matlwangtlwang, South Africa. Qualitative data was collected and analysed by means of a SWOT analysis that aims to highlight various similarities and differences between the two case study areas. It was found that areas within the Global North and Global South address similar social sustainability and Planning themes, yet their practical implementation differs due to their varying local, social contexts. Therefore, Planners have to understand how essential their roles are in integrating and possibly enhancing the level of social sustainability to ensure that the concept is no longer neglected and that unique, context-based solutions are applied.

Keywords: Social sustainability, Planning, Context-based, Global North, Global South.

1. Introduction

Kacowicz (2007:572) and (Basiago, 1999:146-148) stated that there is a growing need for social balance within the Global South since globalisation has increased the level of worldwide inequality and social stratification. Garcia & Rocco (2015:4) added that the increasing urban crisis within the Global South, is partly a result of social imbalance. This social imbalance, amongst other factors, may lead the current generation to a social catastrophe, unless context-based solutions are rapidly applied (Basiago, 1999:146-148).

This research paper aims to discuss the importance of the practical implementation of unique, contextbased social sustainability and Planning themes, in the Global North and Global South. Social sustainability and its related principles will also be analysed and the interface between social sustainability and Planning will be investigated.

The objectives of this research article include; (1)- investigate social sustainability and its related principles, (2)- explore social sustainability and Planning practices of the Global North and Global South, (3)-investigate the interface between social sustainability and Planning, (4)- identify and analyse a case study in both the Global North and Global South by applying social sustainability and Planning themes identified in literature, (5)- employ a comparative case study analysis in order to identify social sustainability and Planning similarities and differences between the Global North and Global South and (6)- conclude and recommend Planning solutions that will contribute to social sustainability froma Global South perspective. The literature study (section 2) and empirical analysis (section 3) of this article, aim to address the mentioned objectives by providing conclusions and recommendations in sections 4 and 5.

1

2. Literature study

The problem statement, research question and objectives that were discussed in section 1 will be unbound throughout this section. Section 1 mentioned that there is an ongoing, global, social imbalance and that Planners may address this issue through the unique practical implementation of social sustainability themes. Section 2 aims to define social sustainability, discuss the interface between social sustainability and Planning, highlight the Global North and Global South context as well as ultimately introduce a matrix that mentions various social sustainability and Planning themes

A thematic analysis will be used to identify specific terms as part of a qualitative inquiry into relevant literature (Maguire & Delahunt, 2017:3352). A content analysis will then be employed to consider the frequency of the terms (Vaismoradi et al, 2013:398). Once the terms are determined, selective coding will be performed to organise the terms into codes, categories and themes, within a matrix (Blair, 2015:18).

2.1 The affiliation between sustainability and social sustainability

Sustainability and social sustainability are two deeply intertwined terms. Section 2.1.1 discusses the connection between these two terms and section 2.1.2 analyses the concept of social sustainability.

2.1.1 Sustainability as the overlaying umbrella

Sustainability, as a policy concept, finds its origin within the 1987 Brundtland report, highlighting that action is needed to meet the needs of the current generation without limiting the needs and aspirations of future generations (WCED, 1987:16). Kuhlman & Farrington (2010:3436) state that sustainability comprises of three tiers, namely; social, economic and the natural environment.

In 2015, the United Nations constructed and implemented the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This agenda aims to build on the Millennium Development Goals with 17 newSustainable Development Goals and 169 targets that will be addressed by all the involved nations, to enhance global sustainable development (United Nations, 2015:3).

UN sustainability goal

Goal 1 End poverty in all its forms everywhere

Goal 2 End hunger, achieve food security and improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.

Goal 3 Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages

Goal 4 Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

Goal 5 Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.

Sustainability tier associated with the UN goal

Reason for the association between the tier and UN goal

Social Poverty directly links to human wellbeing.

Social Nutrition is directly connected to human wellbeing.

Social Wellbeing is an element of social sustainability.

Social Education and inclusivity are elements of social sustainability.

Social Empowerment is an essential social element.

2

Table 1 indicates the UN sustainability goals associated with the social sustainability tier

Table 1: The UN sustainability goals and their reason for being associated with the respective sustainability tiers.

UN sustainability goal

Sustainability tier associated with the UN goal

Goal 6 Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all Social

Reason for the association between the tier and UN goal

Water and sanitation management is essential for the environment and human survival.

Goal 7 Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all

Goal 8 Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

Goal 9 Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation

Goal 10 Reduce inequality within and among countries

Goal 11 Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable

Goal 12 Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns

Goal 13 Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

Goal 14 Conserve and sustainable use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development

Goal 15 Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reserve land degradation and halt biodiversity loss.

Goal 16 Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels

Goal 17 Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development

Environmental

Environmental Energy usage is directly related to the environment

Economic Employment and work are related to the economy.

Economic Innovation is necessary for economic growth.

Social Inequalities focus on social differences between people.

Social Inclusivity and resilience are social sustainability focused, and human orientated.

Economic Consumption and production are related to economic growth.

Environmental Climate change is an environmental focus point.

Environmental Marine conservation is an environmental focus point.

Environmental Biodiversity maintenance is essential for increased environmental sustainability.

Social Inclusivity of societies and institutions are directly associated with human wellbeing.

Social Global economic partnerships require cooperation between people.

Economic

Source: Own composition, 2019 (adapted from: United Nations, 2015:18).

Table 1 illustrates ten of the 17 sustainability goals that are associated with the social tier. Only four of the goals are linked to the economic tier and five to the environmental tier (United Nations, 2015:18). The significant number of goals connected to the social tier highlights the overall emphasis and

3

improvement that is needed from a global, social perspective. While there is room for improvement for all three perspectives, the ratio of economic and environment goals to social goals highlights that the attention should be drawn specifically to the social tier. It is also of interest to investigate whether the goals have a detailed enough description, if they correctly address the social issues at hand or if the goals are too ambitious.

The Economist (2015) stated that the goals are unrealistic and lack a precise focus while the Gates Foundation (2017) warned that is it unlikely that all the targets will be met since some goals are more aspirational than realistic. The application of detailed, local, context-based interventions may be a more realistic and successful approach to enhancing social sustainability levels rather than the application of an overcomplicated and vague global agenda with too many targets.

2.1.2. Disassembling social sustainability as a vital phenomenon

Defining social sustainability and its related themes is often an unclear and difficult task due to the various viewpoints and angles wherefromsustainability is theoretically analysed (Eizenberg & Jabareen, 2016:1 and Woodcraft, 2012:30). Whilst this is necessary, limited attention has been dedicated to defining social sustainability since it was first mentioned over 35 years ago (Moberg & Widen, 2016:5; Dempsey et al, 2009:1 and Rashidfarokhi et al, 2018:1269). It is essential that social sustainability is defined and understood since there is a direct linkage to people, affecting the everyday lives of almost everybody on the planet.

Woodcraft (2012:35) has attempted to define social sustainability as being about people’s quality of life in both the present as well as in the future, adding that the physical environment (infrastructure) is combined with the social and cultural life of individuals. Jeekel (2017:4299) mentioned that social sustainability focuses on education levels, housing, freedom and equity levels, amongst others. It is thus possible to say that social sustainability is an abstract concept that focuses on enhancing the everyday quality of people’s lives through access to basic services, education, health services and transportation measures, while upholding a sense of place and inclusivity within specific environments across the globe.

Reflecting on the UN development goals, it is evident that the social sustainability tier has been neglected in the past. This calls for the additional inclusion and focus on the social tier, for the development of holistic settlements (Erdiaw-Kwasie & Basson, 2018:519). The social tier may also need to be related to the economic and environment tiers (Jeekel, 2017:4299). It may therefore be concluded from the various definitions that social sustainability is of essence to the daily lives of all people.

Section 2.2 addresses the interface between social sustainability and Planning that will essentially support the reasoning behind the introduction of a social sustainability and Planning matrix.

2.2. The interface between social sustainability and Planning

Social sustainability and Planning are two closely related terms that greatly affect the entire world’s population in their everyday lives. Section 2.2.1 and 2.2.2 aim to address this connection as well as mentioning the association between social sustainability and Planning interventions, including, public participation.

2.2.1. Planners as catalysts for the enhancement of social sustainability

Multiple sources (Alexander, 2016:94; Carmon, 2013:4 and Pinson, 2007;1005) define Planning as an abstract profession that aims to improve the living standards of present and future generations, from local to international level. Amanda Burden, the 2002 to 2013, New York City Planning Commissioner, stated in her 2014 TEDx talk that cities, or human settlements, should be built for people and not for buildings (TEDx Talks, 2014). Lynch (1960:5) further elaborated by saying that cities are vivid and integrated physical phenomena that also play a social role Efroymson et al (2009:5) added that public spaces enhance human happiness and ensure civility. These statements summarise the direct essence of Planning; Planners plan sustainable human settlements through a ‘people-centred approach’ that puts people, the heart of social sustainability, first.

4

Planning follows a holistic approach, including housing, transportation measures and accessibility to various land-uses as well as practically implementing policy themes (Association of collegiate schools of planning, 2014:1). Planners are therefore in the ideal position to increase integration and enhance levels of social sustainability (Rashidfarokhi et al 2018:1270). Planners may thus be the middle-man or linkage between the government and local people within society (Carmon, 2013:5). When unbinding the integrated role of a Planner, it may be confirmed that Planners face the greatest responsibilityin ensuring that social sustainability is enhanced. This enhancement may take place through precise planning and engagement with the local community in the form of public participation.

2.2.2. Public participation as an essential social sustainability principle

Carmon (2013:5) advocated that Planning’s mission should focus on working for and with people to enhance the quality of life for all in the built environment. This statement is supported by Jane Jacobs, who once strongly argued that “cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody” (Jacobs, 1961:238) highlighting how essential the role of the everyday citizen is within Planning and social sustainability.

Eizenberg &Shilon (2016:1118) advocate thatPlanning, as a profession, should adopt a ‘people-centred approach’, applying public participation, as a theme of social sustainability, in the decision-making and implementation processes. A national survey conducted in Germany in 2018 indicated a positive correlation between community involvement projects and social sustainability (Rogge et al, 2018:12-15) highlighting the importance of the everyday citizen

The involvement of the local community, through public participation, may allow communities to voice diverse preferences, needs and desires, that should be taken into consideration and eventually be projected in the physical environment. Involving local communities ensures that the likelihood of increasing the level of social sustainability is greater than not involving the community (Beck & Crawley, 2002). Rifkin (1990:29) justifies this statement by mentioning that programs will not achieve their full potential and purpose if not all the stakeholders are involved. It has often become evident that public participation and community involvement, in projects, leads to greater personal investment, maintenance by the locals and ultimately the enhancement of social sustainability (Beck & Crawley, 2002).

Pinson (2007:1007) argues that planning is no longer only a physical or graphical representation, but requires a unity of different social interests within the Planning process. Natarajan (2017:2) discusses that the application of social justice and public participation, as components of social sustainability, are essential to the strategic spatial planning process, whilst also possibly being a powerful liberation tool This philosophical and abstract approach is often associated with politics and community activism (Laverack & Wallerstein, 2001:182) that in turn is related back to Planning.

Public participation is viewed as an essential element of, not only the planning process, but also local, context-based social sustainability. The ‘people-centred approach’ may allow implementation plans to thus be more successful and sustainable when the general public is involved.

2.3 The Global North and Global South

Section 2.2 focused on the interface between social sustainability and Planning. Section 2.3 aims to discuss the geographical differences between the Global North and Global South, following the recent ongoing debate about the usage of the Global North and Global South terms. Frameworks focusing on social sustainability implementation in the two global regions will also be mentioned.

The Royal Geographical Society (s.a.) defines the Global North and Global South as two global regions, split by a geographical line, known as the Brandt line, separating the wealthier and poorer nations, according to their Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This divide has however resulted in a recent, ongoing debate regarding the terms and frameworks associated with them that will be further explained in sections 2.3.1 and 2.3.2.

5

2.3.1 The ongoing debate surrounding Global North and Global South divide

Reunevy & Thompson (2007:557) and Thérien (1999:723-724) advocate that there are multiple differences between the Global North and Global South. They continued by stating that the Global North boasts strong economic, social and political power, while Global South countries, in theory, have weaker economic and social standards with less global political power. The Royal Geographical Society (s.a.), added that Global North countries are often wealthier and more developed countries than the poorer, less developed Global South countries.

An ongoing debate, discussed by Toshkov (2018) questions whether the usage of the terms ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’ is academically correct. Various countries including Côte d’Ivoire and the United Arab Emirates, have grown their GDP per capita higher than the global average of US$10748.71 yet they are geographically located within the Global South (The World Bank, 2017). On the contrary, a Global North country, for example, the Ukraine is still geographically located in the Global North but has a GDP per capita lower than the global average (The Royal Geographical Society, s.a.). Watson (2009:2269) amplifies the debate by advocating that the occurrence of socio-spatial and environmental problems is independent from their position on the global geographical divide. However, for the purpose of this study, the terms Global North and Global South will be used as there have not been new terms established to replace, and increase the accuracy of the terms ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’ .

2.3.2 Global North and Global South policies and frameworks

In section 2.3.1, ongoing debates regarding the Global North and Global South terms were discussed. Section 2.3.2 aims to highlight that, due to the varying local contexts, the application of unique policies and frameworks is essential to allow for the enhancement of social sustainability levels. In theory, and in practice, however, it is evident that policies and frameworks within the Global South are often based on the Global North, lacking a unique context.

Thérien (1999:725) and Thérien & Pouliot (2006:57-58) argue that the lack of global cooperation between nations requires an increased need in individual, national approaches to social sustainability and Planning practices. Van Rensburg (2017:8) added that Planners in the Global South should not copy practices in the Global North, due to their different contexts. These statements support the idea that Global North and Global South social sustainability and Planning theories and practices should apply a unique context in order to ensure successful growth and development.

Ameen & Mourshed (2019:357) discuss that social sustainability frameworks are often based on the Global North context while the Global South experiences completely different, unique social conditions (Watson, 2002:46; Watson, 2014a:229; Watson, 2014b:217; Gibb 2009:702 and Fainstein 2002:476). Social issues experienced throughout the Global South include; (1)- slum conditions or unattractive landscapes, (2)- spatial and social segregation that is often a result of colonial based models, (3)- limited access to education, healthcare or transport facilities, (4)- racial inequalities, (5)- unsuccessful governance and a lack of institutional credibility, (6)- corruption, (7)- a dominant topdown planning approach and (8)- an absence of public participation during decision-making processes (Garcia & Rocco, 2015:3-5; Rifkin, 1990:2 and Service Civil International, 2018:16)

In addition to varying social issues between the two global regions, Van Rensburg (2017:21) found that the majority of articles written on Planning themes in the Global South were written by authors who originate from the Global North. This statement highlights the lack of local, context-based writing and that a large number of articles based on the Global South are written from a Global North perspective. Van Rensburg (2017:22-23) also noted that there were, until 2017, only three articles written on topics related to social development planning in the Global South whilst there were 12 written about the Global North. This once again highlights the lack of essential, Global South focussed social sustainability and Planning research.

Even though the Global South experiences unique social issues that the Global North rarely experiences, it may be mentioned that the social sustainability themes applied in the two global regions are the same, or exceedingly similar. The selective coding matrix in section 2.4 attempts to express

6

various social sustainability and Planning codes that are present within the Global North and Global South.

2.4 A selective coding matrix: social sustainability and Planning.

Section 2.3 highlighted the current context surrounding the Global North and Global South debate and relevant framework applications. Section 2.4 indicates how Global North and Global South social sustainability and Planning codes were identified throughout various literature sources The selfconstructed selective coding matrix aims to connect the literature review’s theory to the empirical study’s practical application.

Coding is defined as an approach to qualitative data analysis (Cohen et al, 2018:668), whereby simple names or labels within texts are selected that contain similar information or ideas (Miles & Huberman, 1994:56 and Gläser & Laudel, 2013:15). Selective coding differs from other coding types, and was purposefully selected for this study, as it identifies core phenomena that are integrated and related to one another (Cohen et al, 2018:672). This ensures that all the selected codes are connected to the two main concepts; Planning and social sustainability. Cohen et al (2018:672) continued to add that once the codes were selected by constant comparisons between various points of information, categories were identified that link various codes together by their main concept. The categories were then further analysed and grouped together to identify themes, that relate back to the main concepts; social sustainability and Planning.

The 100 different codes, identified throughout various literature sources (see annexure A for detailed referencing of the various sources), were focused on social sustainability and Planning literature and case studies performed in both the Global North and Global South. Figure 1 indicates the 100 codes that were grouped into 13 categories and eventually into five themes. All 100 codes, 13 categories and five themes highlight the two main concepts; Planning and social sustainability, and will be used to form the base of the empirical study in section 3.

CODES CATEGORIES THEMES

Decent housing

Urbanity

Urban form

Mixed tenure

Compactness of physical urban form

Mixed land uses

Urban space hierarchy

Diversity of residential units

Conservation of buildings

Intelligent buildings

Harmony with surroundings

Design of spaces

Design that increases interaction in buildings

Design that increases interaction in public spaces

Design encourages interaction

Sustainable urban design

Visual quality

Diversity of transport modes

Bicycle network

Walkability

Land uses

Design and layout

Design

Transport Accessibility

7

CODES CATEGORIES THEMES

Ability to walk

Lack of walking possibility

Sustainable transport

Walkable neighbourhood

Pedestrian friendly

Traffic

Accessibility to local facilities

Accessibility to infrastructures

Street network

Infrastructure networks

Having meeting places

Attractive public realm

Project location for public access

Pubic space

Children play areas

Identity and local culture

Preservation of local features

Place attachment

Pride

Dependence to place

Participation in decision-making

Stakeholder consultation

Top-down approach

Neighbourhood involvement

Participatory design

Bottom- up approach

Participation

Sense of belonging

Supporting community groups

Social networking integration

Neighbourhood

Social interaction

Social networks

Group participation

Community stability

Involvement

Security

Vitality

Safety

Infrastructure

Public spaces

Sense of place

Identity

Decisionmaking

Public involvement

Public participation in decision-making processes

Social networking

Social cohesion and wellbeing

Safety

8

CODES CATEGORIES THEMES

Repairs

maintenance failures

social security

security by design

safety of public spaces

safe streets

safe working environments

healthy working environments

Freedom

Democracy

Justice

Cultural values

Discrimination

Reducing social abnormalities

Socio-cultural problems

Social inclusion

Sense of community

Equity

Adaption for social inclusion

Inclusive design

Education

Hygiene

Calmness

Pollution

Insecurity

Local environmental quality

Quality of life

Health

Wellbeing

Light and noise pollution

Protection from high temperatures and sunlight

Economic diversity

Employability

Encourage new investments

Amenities

Innovative urban solutions

Smart locations

Appropriate locations

Flexibility

Inclusivity

Health and education

Opportunities

9

CODES CATEGORIES

Availability

Regular organising

Figure 1: Selective coding matrix.

THEMES

Source: Own composition (2019) based on Ameen & Mourshed (2019:361); Arnett (2017:140); Dempsey et al (2009:3); Eizenberg & Jabareen (2016:1); Garcia & Rocco (2015:5); Kuhlman & Farrington (2010:3440); Olakitan Atanda (2019:238); Perovic & Folic (2012:927-931); Sanei et al (2017:249); Turel et al (2007:2035) and Woodcraft (2012:34).

The self-constructed selective coding matrix will ultimately aim to assist in the theoretical and practical application analysis of social sustainability and Planning, and how it varies between case studies in the Global North and Global South, respectively. The 5 themes identified in the selective coding matrix will form the base of the empirical study in section 3

3. Empirical study

Context-based integration strategies are essential for enhancing the level of social sustainability within an area (Ameen & Mourshed, 2019:357). While the Global North and Global South may address similar social sustainability and Planning themes, in literature, refer to figure 1, incorporating these themes in unique, local contexts may be of essence. This empirical study aims to highlight the necessity of contextbased social sustainability strategies and Planning approaches by conducting a comparative case study analysis between Global North and Global South case study areas. Furthermore, this study aims to identify similarities and differences between two case study areas through the application of social sustainability and Planning themes, derived from a selective coding matrix.

The two case study areas include, Amsterdam, The Netherlands and Matlwangtlwang, South Africa. A SWOT analysis was employed to analyse social sustainability and Planning themes, related to the two case studies. Gürel & Tat (2017:996) define the four SWOT analysis components as (1)- Strengths (giving an advantage), (2)- Weaknesses (giving a disadvantage), (3)- Opportunities (providing potential benefits) and (4)- Threats (giving off potential trouble).

In order to ensure that the case studies cover roughly similar sized areas, specific neighbourhoods within Amsterdam were selected (Oudepijp, Nieuwepijp, Ijselbuurt and Diamantbuurt) to match the spatial size of Matlwangtlwang. These four neighbourhoods equal to roughly 191Ha (Centraal bureau voor de statistiek, 2008) and will thus be compared to Matlwangtlwang that equals to roughly 192Ha in size (Frith, 2011). Prior to carrying out any empirical research, the already contradicting social climates experienced in Amsterdam and Matlwangtlwang, may indicate that the selection of these two case studies is ideal.

It may be conveyed that Amsterdam is a Global North, socio-economic, best practice example due to the long-time serving and stable social democracy within the city, as well as boasting low levels of segregation (Savini et al, 2016:103). The researcher’s high level of personal experience within the city was a reason for the selection of Amsterdam as a case study area. In addition to this, a high level of personal interest (De Vos et al, 2011: 84-85) in this vibrant city, due to its cultural diversity and outstanding Planning history, were other reasons for the selection of this case study area.

Matlwangtlwang was selected as the Global South case study as it highlights typical characteristics of a South African informal settlement. These characteristics include being spatially and racially segregated from surrounding formal areas, comprising of limited transportation and economic opportunities as well as having exceedingly limited social elements or areas that allow for ‘civic interaction’ (Findley & Ogbu, 2011). Matlwangtlwang is thus a representative of the challenges faced within South African informal settlements. In addition, access into the Matlwangtlwang community was already established, meaning that a work relationship with key informants within the area was already entrenched and permission to interview residents was obtained, prior to the commencement of this study. This allowed for an ease of access during the data collection process of the empirical analysis.

In this study, qualitative data was collected by employing various collection methods, including; (1)- semi-structured interviews, (2)- observations, (3)- a transect walk and (4)- community mapping. Semi-structured interviews are in-depth, open-ended and complex interviews with respondents to

10

understand their subjective opinion about the topics of interest (De Vos et al, 2011:353). A transect walk is, according to Omer (2017:1) classified as an interactive field activity where the researcher walks through the study area. The transect walk often goes hand-in-hand with the observations made by the researcher. The observations include the recognition of various elements related to the research, within the study area (Robergs, 2010:1). Community mapping is a spatial and subjective approach to data collection, often performed by the participant, and may occasionally be assisted by the researcher (Omer, 2017:2). The data collection methods aim to collect qualitative information that relates to the five social sustainability and Planning themes identified within the selective coding matrix presented in Figure 1

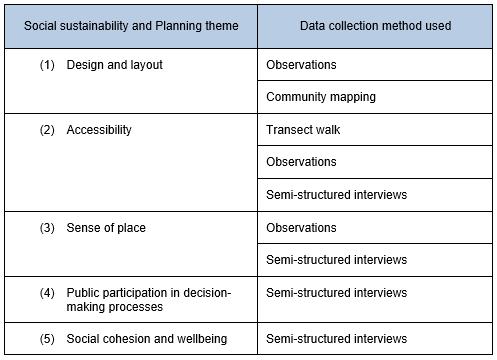

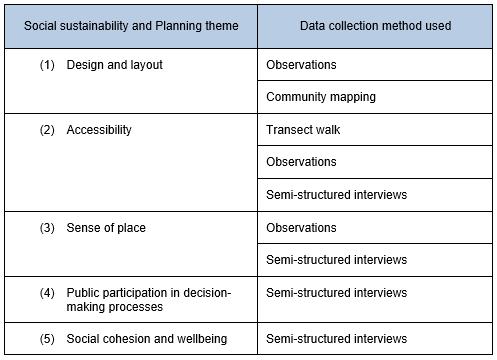

Table 2 aims to express the various data collection methods that were applied to the five social sustainability and Planning themes, established in Figure 1.

Table 2: Data collection methods associated with the five social sustainability and Planning themes.

Source: Own composition (2019)

The five themes mentioned in Table 2 will be applied to the two case study areas and assessed by a SWOT analysis, within section 3.1 and 3.2

11

3.1. Empirical study: Amsterdam

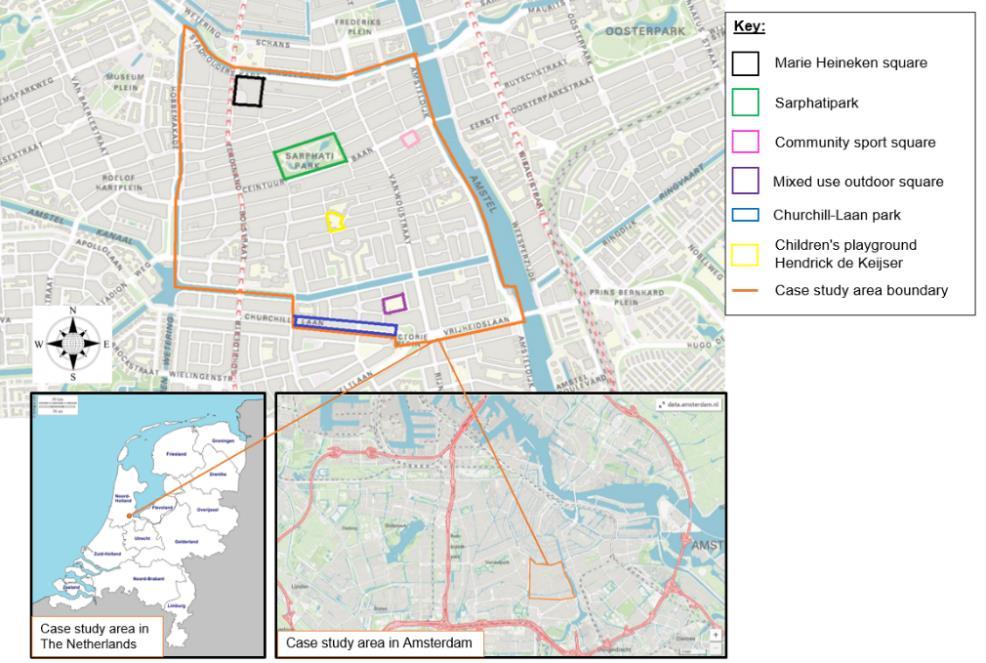

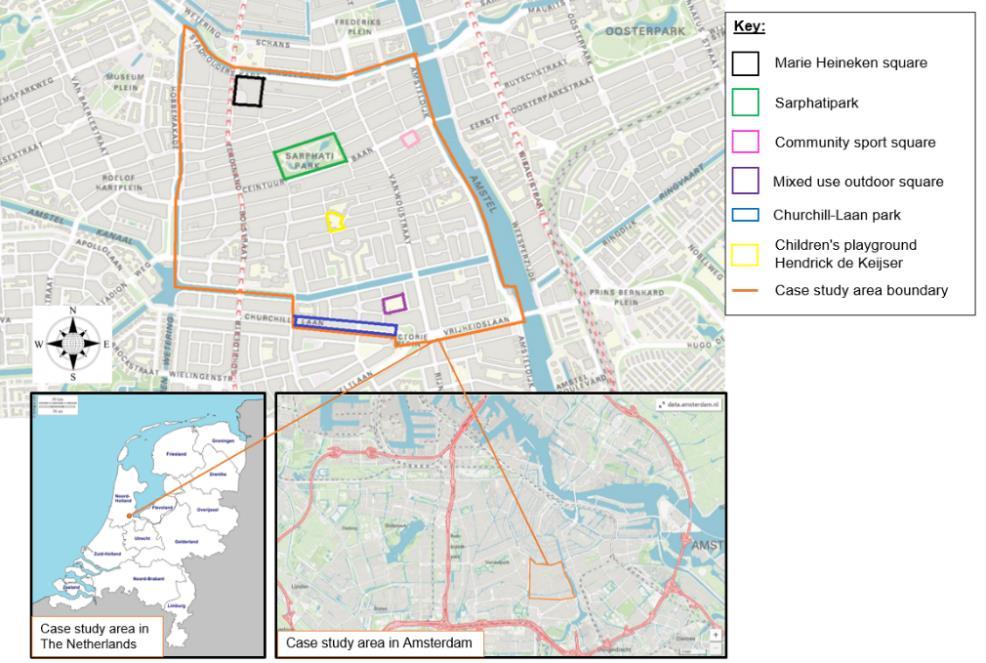

This section aims to investigate Amsterdam, as one of the two case study areas, with regards to the five social sustainability and Planning themes established within the selective coding matrix (refer to Figure 1). In addition, the results obtained from the five social sustainability and Planning themes are summarised in the form of a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis. Figure 2 indicates the locality of the selected study area within Amsterdam, a medium-high income area within the province of North-Holland, The Netherlands.

Figure 2: Map indicating the focus area within Amsterdam.

Source: Own composition, 2019 (Adapted from Gemeente Amsterdam, 2018).

Figure 2, indicates the selected focus area within Amsterdam, the Global North case study. The selected focus area consists of four neighbourhoods; the Oudepijp, Nieuwepijp, Diamantbuurt and Ijselbuurt. The reason for the selection of four neighbourhoods within Amsterdam, as opposed to Amsterdam as a whole, is to ensure that the spatial size of the two case study areas; Amsterdam and Matlwangtlwang, are roughly equal. The four selected neighbourhoods within Amsterdam are well known for being some of the city’s most popular residential areas. This residential focused area thus expresses similar characteristics as Matlwangtlwang, as this too expresses mainly residential functions. However, the four selected neighbourhoods in Amsterdam boast additional land uses, as opposed to being purely residential. Figure 2 also indicates the main public spaces within the selected case study area.

Theme 1: Design and layout

While making observations of the focus area and performing the community mapping process, it was evident that there were multiple obvious social hotspots or social facilities present within the selected focus area. Figure 3 indicates the various social amenities within the focus area, as expressed through the community mapping process.

12

Source: Own composition, 2019 (Adapted from Gemeente Amsterdam, 2018)

As indicated within Figure 3, the selected focus area within Amsterdamhighlights multiple obvious public social hotspots as well as commercial areas, investment zones and transportation nodes, in addition to the residential units throughout the entire area. The focus area highlights the integration of mixed landuse and transportation activity taking place along main roads. The main roads are highlighted by the taxi and tram routes, visible in Figure 3. The convergence of multiple transportation modes as well as transportation pick-up/drop-off zones, public spaces suitable for all age-groups, residential units as well as commercial and business units may express characteristics of an ideal functioning and socially enhanced environment.

Table 3 summarises the SWOT analysis results obtained for theme 1, according to methods highlighted in table 2.

Source: Own composition (2019).

Table 3 highlights theme 1’s results, preparing for theme 2.

13

Figure 3: Community map for the focus area within Amsterdam.

Table 3: SWOT analysis of the design and layout theme.

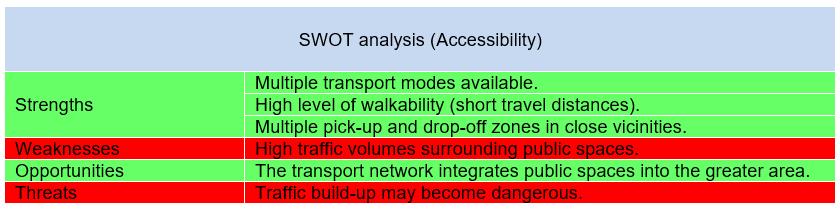

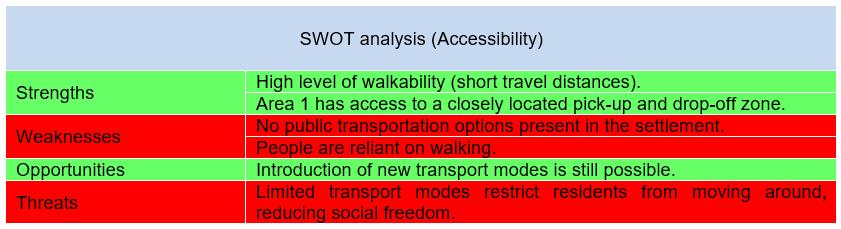

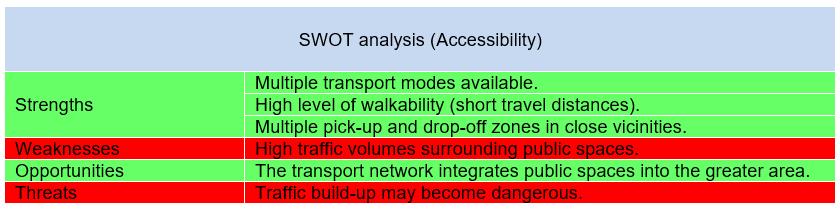

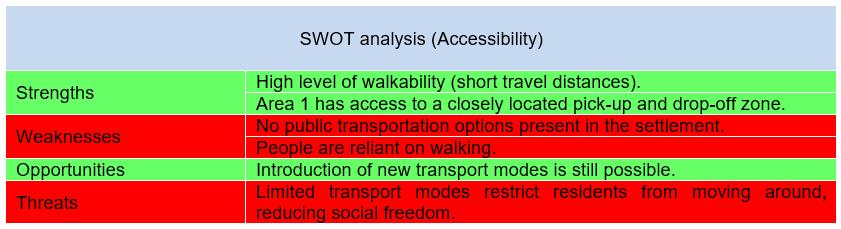

Theme 2: accessibility

Throughout the transect walk and observation made within the focus area, it was identified that the road reserves within Amsterdam consist of paved roads that allow for simultaneous movement of multiple transportation modes. Road reserves include pedestrian sidewalks, clearly stipulated cycle paths, motor vehicle lanes used by cars, taxis, busses and scooters as well as tram lines used by the advanced and well-integrated tram system. Usage of the underground metro system is also highly accessible. The segregation of various transportation modes ensures that the optimum safety level within the city is upheld.

The well-integrated transportation system allows for rapid access to various land uses throughout the city. In addition, the community map (Figure 3) clearly indicates the vast number of transportation pickup and drop-off zones. Allocation of pick-up and drop-off zones in walking vicinity to public spaces may also ensure that the level of social sustainability within these public spaces is rapidly enhanced.

Table 4 summarises the SWOT analysis results obtained for theme 2, according to methods highlighted in table 2.

Table 4: SWOT analysis of the accessibility theme.

Source: Own composition (2019).

Table 4 highlights theme 2’s results, preparing for theme 3.

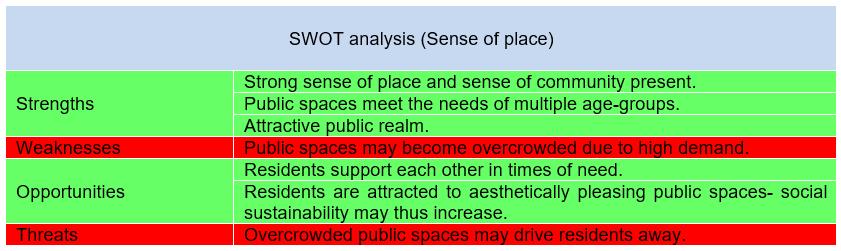

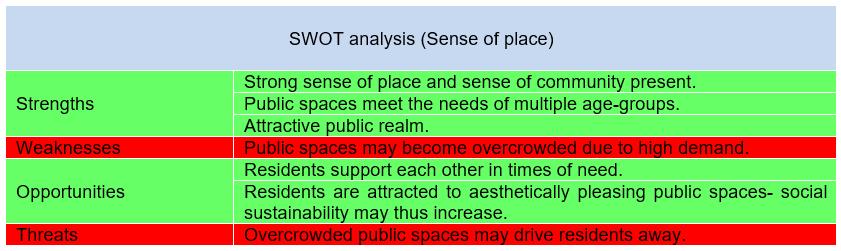

Theme 3: sense of place

The sense of place experienced at a specific location is a subjective experience and therefore tends to differ between people. The observations made in the focus area within Amsterdamare thus observations made from the viewpoint of the researcher, an outsider, who is familiar with the greater city but not specifically the focus area, and experiences the area from the viewpoint of a Planner.

Amsterdam, and specifically the focus area within Amsterdam, may be viewed as an aesthetically pleasing city that houses a diversity of cultures, races and religions amongst its residents. The high level of diversity and inclusion amongst residents gives reason to why respondents stated that the sense of community is exceptional and why they feel exceedingly connected to Amsterdam, and specifically their neighbourhood. Residentsin Amsterdamspend their spare time socialising with family and friends within their homes as well as in social hotspots including parks, squares, cafes and restaurants. Negative feedback that respondents projected was that in some instances, the level of traffic and crowdedness of public spaces may be negative to residents’ social experiences. This feedback was however not influential enough for respondents to feel unhappy. All respondents expressed that they were happy in their living environments and that they would not change anything about their surroundings or the public realm that they visit.

Table 5 summarises the SWOT analysis results obtained for theme 3, according to methods highlighted in table 2.

14

Source: Own composition (2019).

Table 4 highlights theme 3’s results, preparing for theme 4.

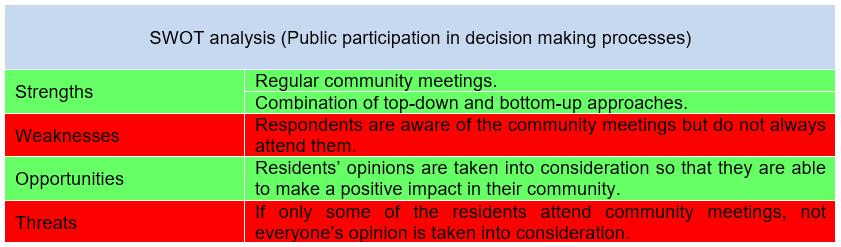

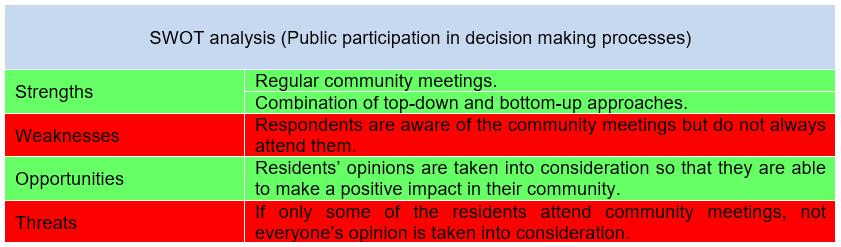

Theme 4: public participation in decision-making processes

Respondents in Amsterdam projected a unanimous state of happiness. As a result, respondents feel that it is unnecessary to attend community meetings with members of the government since they do not have any issues to discuss. However, respondents also expressed that if they were unhappy, the government would address their issues. It may thus be confirmed that there is an effective combination between the usage of a top-down and a bottom-up approach

Table 6 summarises the SWOT analysis results obtained for theme 4, according to methods highlighted in table 2.

Table 6: SWOT analysis of the public participation theme.

Source: Own composition (2019)

Table 6 highlights theme 4’s results, preparing for theme 5.

Theme 5: social cohesion and wellbeing

The feedback obtained from respondents projected an exceeding number of happy residents who would not change anything about their neighbourhood or community. Respondents stated that they experience a strong sense of community amongst the local residents as the residents support each other in times of need. In addition, residents feel safe and included within their communities.

Table 7 summarises the SWOT analysis results obtained for theme 5, according to methods highlighted in table 2.

15

Table 5: SWOT analysis of the sense of place theme.

Source: Own composition (2019).

Table 7 highlights theme 5’s results, preparing for section 3.2.

It may be concluded that respondents from the selected focus area in Amsterdam, deem their environment as highly accessible, that they experience a strong sense of community and inclusion within their neighbourhood, that they would not change anything about their environment as well as being attracted to the public realm. Section 3.2 aims to apply the same SWOT analysis to the five themes addressed in the Global South case study; Matlwangtlwang.

3.2.

In this section, it is aimed to investigate Matlwangtlwang, as one of the two case study areas, with regards to the five social sustainability and Planning themes, established in Figure 1. Subsequently, the results obtained from each of the five social sustainability and Planning themes will be summarised in the form of a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis. Figure 4 indicates the locality of Matlwangtlwang, a lowincome, rural settlement located in the Free state province of South Africa

Source: Own composition, 2019 (Adapted from Google Maps, 2019).

16

Table 7: SWOT analysis of the social cohesion and wellbeing theme.

Empirical study: Matlwangtlwang

Figure 4: Map indicating Matlwangtlwang and the two focus areas within the settlement.

Figure 4 indicates the Global South example- the lower income study area of Matlwangtlwang, adjacent to the formallyplanned, middle-higher income area of Steynsrus, but segregated spatially, and ultimately racially, by two regional roads. Measuring roughly 192 Ha in size, Matlwangtlwang highlights multiple characteristics of the average South African, Apartheid established, lower income and/or informal, settlements. As already mentioned earlier, Findley & Ogbu (2011) listed some of these characteristics, namely; (1)- spatial and racial segregation from surrounding formal areas, (2)- having limited transportation and economic opportunities as well as (3)- having very limited social elements or areas that allow for ‘civic interaction’. Referring back to the Matlwangtlwang case study area, the two focus areas within the informal settlement include the informal area (area 1) and the relocated area (area 2).

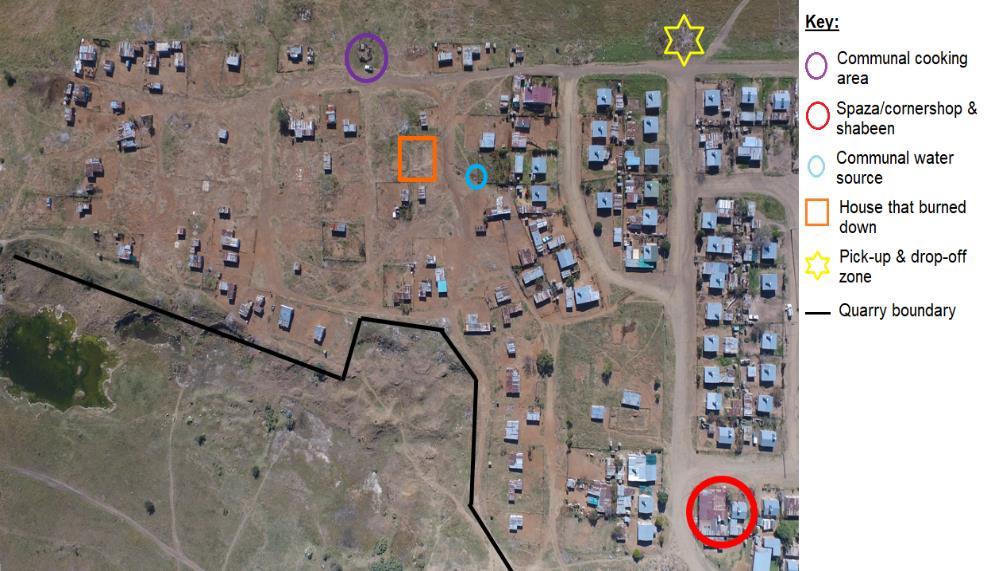

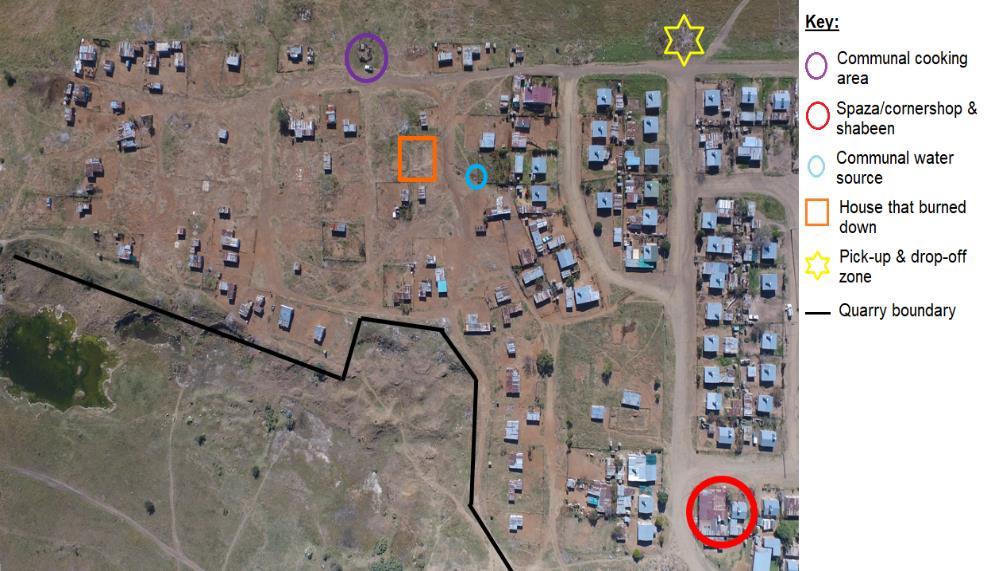

Theme 1: design and layout

While making observations of the two areas within Matlwangtlwang, and performing the community mapping process, it was clear that there were limited, to no, formal social hotspots or social facilities present within the two settlement areas. There were, however, informal social hotspots present. Figure 5 indicates the various social hotspots and interactive facilities within area 1, compiled through the community mapping process.

Source: Own composition (2019)

As illustrated in Figure 5, area 1 included a communal cooking area where the majority of the men from this area spend their day socialising and cooking. The residents that do not spend their time at the selfprovided cooking facility spend their time in the yards of their homes. Economic activity and community meetings take place at the local spaza/cornershop while residents also gather at the communal water source. The rest of the structures visible in Figure 5 are individual residential structures. Area 1 composes of an unplanned and informal block layout, adjacent to the planned area, with segregation of land uses. Figure 5 also indicates an informal mini-bus taxi pick-up and drop-off zone, a quarry adjacent to multiple houses in the informal area as well as a vacant piece of land as the house that previously stood there was burned down. This will be addressed later under the social cohesion and wellbeing theme.

17

Figure 5: Community map for area 1 in Matlwangtlwang.

Figure 6 indicates the economic facilities and community meeting zone within area 2, expressed through community mapping.

Source: Own composition (2019).

Area 2, presented in Figure 6, contains no designated or formal social amenities while this is the most recently formalised area within the Matlwangtlwang settlement. Many of the residents who previously lived within area 1, now reside in area 2, as they were relocated to this area. In addition to the four identified informal, backyard spaza/corner shops, that sell a limited number of basic items, there are no formal economic structures within this area. A proposed public park, that local residents are unaware of, is also indicated in Figure 6. The light pole simultaneously acts as the community meeting zone since no formal amenity has been provided for this purpose. Electricity lines are visible in this area but respondents complained as they do not have access to electricity in their homes. The rest of the structures visible in Figure 6 are individual residential structures. Contrary to area 1, area 2 expresses a formal block layout, but similar to area 1, the majority of the residents spend their time socialising at their homes or backyards as there are no formalised public spaces.

Table 8 summarises the SWOT analysis results obtained for theme 1, according to methods highlighted in table 2.

18

Figure 6: Community map for area 2 in Matlwangtlwang.

Source: Own composition (2019).

Table 8 highlights theme 1’s results, preparing for theme 2.

Theme 2: accessibility

As mentioned before, a transect walk and observations are generally performed simultaneously (Omer, 2017:2). During the transect walk and observations, it was observed that the road reserves within area 1 and 2 composed of dirt roads with a large amount of rubble and fist-sized rocks lying around in the road. The multi-modal road does not segregate pedestrians and other transport modes from each other.

There was limited, to no, motorised traffic within the two informal areas and there was only one resident within area 2 that owned a private motor vehicle. The rest of the residents are dependent on walking. However, in area 2, there is a mini-bus taxi that, when it does not rain, picks the children up from their homes and takes them to the crèche where they spend their day. When it rains, the mini-bus taxi is not able to access the informal houses as the roads are often covered in water or are deteriorated, making it impossible for the mini-bus taxi to drive in the settlement. Residents in area 1 indicated that there is a designated taxi drop-off and pick-up area in a close vicinity to the informal settlement. Area 2, however, does not have a designated pick-up or drop-off zone resulting in residents often hitchhiking along the adjacent regional road. Travelling distances between the various houses and social hotspots in the Matlwangtlwang settlement are within a walking distance since travelling distances average roughly between 100m and 200m, ensuring that the level of access is high.

Table 9 summarises the SWOT analysis results obtained for theme 2, according to methods highlighted in table 2.

Table 9: SWOT analysis of the accessibility theme.

Source: Own composition (2019).

Table 9 highlights theme 2’s results, preparing for theme 3.

19

Table 8: SWOT analysis of the design and layout theme.

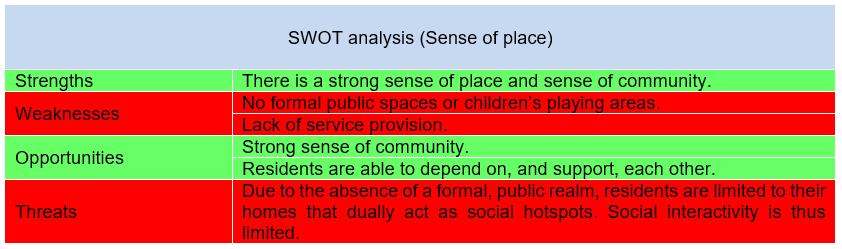

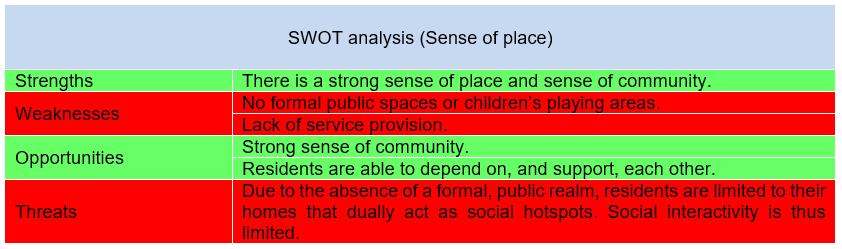

Theme 3: sense of place

The sense of place experienced is subjective. The observations made in both areas are observations made from the viewpoint of the researcher, an outsider, who does not live in Matlwangtlwang, or any other South African informal settlement, and experiences the settlement from a Planning perspective.

Matlwangtlwang may be described as having a barren landscape with inadequate quality shelters and lacking any service provision, ultimately making a description of the average South African informal settlement. However, a resident living in the settlement may approach the sense of place in a different manner and describe it as thriving with life and attaching sentimental value to the place as it is their home and their community. The respondents in Matlwangtlwang described that they are unhappy about the lack of service provision and that they would like the local government to provide them with green areas, public spaces and community facilities, in addition to basic services. However, even though the residents are upset about various issues, all of the respondents involved described themselves as being happy in their environment.

Almost all of the residents in Matlwangtlwang interact with one another in their yards and homes, that being one of the predominant points that make the residents happy. In addition, respondents also mentioned that there is a strong sense of community and interdependency amongst various residents in the settlement.

Table 10 summarises the SWOT analysis results obtained for theme 3, according to methods highlighted in table 2.

Table 10: SWOT analysis of the sense of place theme.

Source: Own composition (2019).

Table 10 highlights theme 3’s results, preparing for theme 4.

Theme 4: public participation in decision-making processes

As gathered from the respondents living within Matlwangtlwang, public participation in decision-making processes is predominantly absent since respondents feel that their opinions are often neglected. Government officials tend to address local residents once a month and listen to local requests and opinions, but contradicting to this, decision-making is done solely by the government who proceed to inform local residents of their decisions. There is thus a dominant top-down approach followed within Matlwangtlwang.

Local residents are informed about government decisions at informal meetings held within the two settlement areas; at the local spaza/cornershop in area 1 and under the large light pole in area 2. Community meetings are open to all residents from the respective areas. Respondents stated that almost all of the local concerns discussed within meetings are focused on the lack of service provision and that any topics surrounding social activities or provision of social amenities are never mentioned.

Table 11 summarises the SWOT analysis results obtained for theme 4, according to methods highlighted in table 2.

20

Source: Own composition (2019)

Table 11 highlights theme 4’s results, preparing for theme 5.

Theme 5: social cohesion and wellbeing

In addition to the general happiness and strong sense of community among residents, during the day, residents feel safe in their respective areas. At night, however, it was mentioned that the area is unsafe. ‘Safety’ related codes were so prominent that it became a category within the social sustainability and Planning matrix (see Figure 1). Focusing on safety, one of the respondents explained that some selfconstructed houses were burned down as a result of lit candles falling over during the night. In addition to this, one of the women living in area 1 had her house burned down by an unknown member of the community, for an unknown reason. The woman now resides with other family members. The quarry in area 1 also poses danger at night as residents may fall into the quarry and injure themselves. However, respondents feel that the burning incidents and danger of the quarry are not substantial enough threats to make them feel endangered.

When asked if respondents would change anything about their environment, all respondents mentioned that service provision was their main issue and that they want it to be addressed. In addition to this, a resident stated that she would like to see the development of a green park with sitting places that will boost the aesthetic appeal of the area, as well as allowing her to meet new people.

Table 12 summarises the SWOT analysis results obtained for theme 5, according to methods highlighted in table 2.

Table 12: SWOT analysis of the social cohesion and wellbeing theme.

Source: Own composition (2019).

21

Table 11: SWOT analysis of the public participation theme.

Table 12 highlights theme 5’s results, preparing for section 3.3.

Respondents within Matlwangtlwang highlighted that they experience a strong sense of place and community, that they are happy within their settlement and that they often attend local meetings to address issues. Matlwangtlwang’s informal layout and transportation modes highlights how it differs from Amsterdam. Section 3.3, the summary of findings, aims to further discuss similarities and differences between the Global North and Global South case study areas.

3.3. Summary of findings

Table 13 indicates a reflection as well as similarities and differences identified between Amsterdam and Matlwangtlwang, when analysed according to the five social sustainability and Planning themes.

Table 13: Comparing apples to oranges: a reflection of social sustainability in Amsterdam and Matlwangtlwang.

Differences between the case study areas

Social sustainability and Planning theme

(1)

Design and layout

Amsterdam Matlwangtlwang

Formally planned, well integrated, public spaces and social hotspots.

Similarities between the case study areas

Amsterdam and Matlwangtlwang

Informal public spaces with limited integration into the greater area. Application of more than one land-use within the area

Formal social amenities. Informal social amenities.

Well integrated transport system

(2)

Accessibility

Multiple transport modes

High level of traffic (high volumes, multiple transport modes and the urban location)

(3)

Sense of place

Lack of a wellintegrated transportation system.

Limited transport modes.

Low level of traffic (limited transport movement, rural location and lower income level)

Public spaces overcrowded with tourists (busy and bustling area).

Limited activity surrounding informal public spaces (Quiet areas).

High level of walkability (Short travel distances)

Reflection on the social sustainability and Planning theme

Formal Global North vs informal Global South.

Varying transport modes and traffic volumes

Strong sense of place and sense of community Social interaction in both public and private spaces. Residents support each other in times of need

(4)

Few residents attend local government meetings

Many residents attend local government meetings. Regular community meetings held

Top-down and bottom-up approaches vary, as well as the public

22

Social sustainability and Planning theme

Differences between the case study areas

Similarities between the case study areas

Amsterdam and Matlwangtlwang

Reflection on the social sustainability and Planning theme

Amsterdam Matlwangtlwang Public participation in decision-making processes

(5)

Social cohesion and wellbeing

Bottom-up and topdown approach.

Top-down approach is dominant.

Active and busy public realm (populous)

Source: Own composition (2019).

Public realm is often absent (People remain at home) Strong sense of inclusivity, safety and unity.

Varying public and private realm but similar strength in unity and inclusion.

As indicated by Table 13, Amsterdam and Matlwangtlwang experience multiple social sustainability and Planning similarities and differences. Overlaying differences between the Global North and Global South case study areas include the public realmand social hotpots within the two areas. Amsterdamexpresses multiple formal, public spaces and social hotspots (Public parks, squares, commercial areas and children’s playgrounds). Matlwangtlwang expresses a few informal, social hotspots (A communal tap, communal cooking area, spaza/corner shops, in addition to respondents’ houses dually acting as a social amenity). It may be questioned, from a Global North perspective, whether or not the informal social hotspots in Matlwangtlwang are socially sustainable. The strong sense of community and sense of place, in addition to the overall happiness of the respondents, ensures that the level of social sustainability associated with informal, social hotspots is upheld and maintained.

Conclusions and recommendations regarding the unique application of social sustainability and Planning themes in the Global North and Global South, will be made within sections 4 and 5.

4.Conclusions

The empirical study in section 3 examined two case study areas (Amsterdam and Matlwangtlwang) and established research findings based on their respective social sustainability and Planning contexts. Section 4 intends to highlight various conclusions made throughout the research article while considering the research objectives that were established in section one. Objectives 1 to 5 are discussed individually, while objective 6 is addressed by sections 4 and 5

Objective 1: investigate social sustainability and its related principles.

(1) The neglect of social sustainability

Social sustainability, being one of the three tiers of sustainability, has been a continuous global topic for the last 32 years and is a central focus point within the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals. However, the social tier has been greatly neglected when compared to the economic and environmental tiers. The economic and environmental tiers highlighted four and five UN goals, respectively, while the social sustainability tier highlighted ten of the UN goals. The substantial focus on the social tier, within the 2030 UN policy, highlights the extensive improvement that the social tier requires.

23

turnout at community

meetings.

(2) Social sustainability as an ill-defined concept

Defining social sustainability has often been an unclear and difficult task as the concept involves multiple elements, including education, housing, thelevel of freedom, access to services and the levelof equality The concept thus involves multiple focus points that are overbridged by the idea of improving the quality of life within an environment.

Objective 2: investigate the interface between social sustainability and Planning.

(3) The essential role of a Planner to enhance social sustainability

It is essential to highlight that Planners plan living environments to enhance living standards. Planners act as an intermediary between local residents and various spheres of government. The Planner therefore often acts as the representative of local residents’ opinions, throughout the planning process.

Objective 3: explore social sustainability practices in the Global North and Global South

(4) The varying social contexts of the Global North and Global South

The Global North and Global South are two geographically different regions with varying local, social contexts. However, the Global South often applies frameworks and policies written from a Global North perspective. There is therefore often a lack of application of unique, local frameworks and policies.

(5) The imprecise literature approach to social sustainability in the Global North and Global South

Literature written on social sustainability is generally limited but specifically when focusing on social sustainability literature from a Global South perspective. The majority of Global South literature is often written by Global North authors who may lack knowledge of the unique local context in the Global South.

Objective 4: identify and analyse a case study in the Global North and Global South by applying social sustainability themes identified in literature

(6) Case study areas apply the same social sustainability and Planning themes

The two case study areas include Amsterdam, The Netherlands (Global North) and Matlwangtlwang, South Africa (Global South). Both case study areas were analysed through the application of five social sustainability and Planning themes, namely; (1)- design andlayout, (2)- accessibility, (3)- sense of place, (4)- public participation in decision-making processes and (5)- social cohesion and wellbeing.

Objective 5: employ a comparative case study analysis in order to identify similarities and differences in social sustainability between the Global North and Global South

(7) The similarities and differences between the two case study areas

The Global North and Global South experience multiple similarities and differences, but both regions hold a substantial amount of unique qualities and potential to enhance the level of social sustainability Table 13 indicates various points of reflection on the five social sustainability and Planning themes. The points of reflection lead to various conclusions made regarding the social sustainability and Planning approaches in the Global North and Global South. These include:

(a) Design and layout

1- The level of social sustainability is not necessarily influenced by the level of formality or informality.

2- A predetermined Global North social sustainability benchmark may result in a biased form of analysis, favouring the Global North conditions. This may happen consciously or subconsciously.

24

(b) Accessibility

1- Global North and Global South areas make use of varying transportation modes.

2- The Global North and Global South case study areas experience different levels of urbanity and traffic volume.

(c) Sense of place

1- The sense of place is influenced by various factors, for example, the number of people accumulating in an area.

2- The sense of place within Global North and Global South public and private spaces differs.

(d) Public participation in decision-making processes

1- The Global North and Global South apply different top-down and bottom-up approaches.

2- Global North residents seldom attend community meetings while Global South residents often attend meetings. The level of trust in the local government therefore differs.

(e) Social cohesion and wellbeing

1- The level of activity within the public realm does not necessarily determine the level of social sustainability within an area.

2- A strong sense of unity and inclusion within local communities ensures a strong sense of wellbeing and social cohesion.

Section five will aim to provide recommendations to the various conclusions made throughout this section.

5.Recommendations

This section intends to present various recommendations while considering the research conclusions that were established in section 4 As stated earlier, objective 6 is discussed throughout sections 4 and 5. Recommendations are made for the following objectives and conclusions:

(1) Objective 1: investigate social sustainability and its related principles

Conclusion: the neglect of social sustainability

It may be suggested that social sustainability should receive as much attention as the economic and environmental tiers. This may be achieved by careful focus on the inclusion and enhancement of social based policies. In addition to the policies, the practical implementation of local, social based strategies and inclusion of public participation in decision-making processes may be addressed.

(2) Objective 1: investigate social sustainability and its related principles

Conclusion: social sustainability as an ill-defined concept

Providing a definition for social sustainability, and possibly including a list of all the involved concepts, including education, the level of freedom and equality, may provide clarity surrounding the concept and indirectly ensure an emphasis on the elements involved.

(3) Objective 2: investigating the interface between social sustainability and Planning

Conclusion: the essential role of a Planner to enhance social sustainability

Planners play an essential role in the potential enhancement of social sustainability. Planners should therefore realise the importance of their roles and take responsibility in ensuring that policies and frameworks highlight local issues and suggestions. It is recommended that Planners build a strong

25

connection with the local community and put local interests first, while informing various spheres of government about local needs and opinions.

(4) Objective 3: explore social sustainability and Planning practices in the Global North and Global South.

Conclusion: the varying social contexts of the Global North and Global South

It is recommended that Planners, spatial researchers, other spatial professionals and the government realise that local solutions to unique, local issues are of essence. Stakeholders may therefore need to include local residents through public participation methods to establish local needs, issues and ultimately local solutions.

(5) Objective 3: explore social sustainability and Planning practices in the Global North and Global South

Conclusion: the imprecise literature approach to social sustainability in the Global North and Global South

Global South focused social sustainability and Planning research should be generated by authors who understand and experience the Global South context. Through the enhancement of Global South based social sustainability and Planning research, the local Global South context may potentially be more accurately understood and local Global South solutions may arise.

(6) Objective 4: identify and analyse a case study in the Global North and Global South by applying social sustainability and Planning themes identified in literature.

Conclusion: case study areas apply the same social sustainability and Planning themes

It is recommended that local residents, Planners, researchers, other professionals and local government, work together to establish local solutions and methods of implementation of solutions, based on local needs and issues. By applying local solutions, the unwanted ‘copy-paste’ method will be avoided and may ensure that in the Global South, Global South solutions are applied rather than Global North ‘copy-paste’ solutions that may not solve any issues

(7) Objective 5: employ a comparative case study analysis in order to identify similarities and differences in social sustainability between the Global North and Global South

Conclusion: the similarities and differences between the two case study areas.

It has been established that the Global North and Global South experience various similarities and differences. Based on the five social sustainability and Planning themes, various recommendations are made according to the individual conclusions in section four. These include:

(a) Design and layout

1- Informal solutions for the enhancement of social sustainability should be considered just as much as formal solutions.

2- Predetermined benchmarks or biases should be avoided at all times during analysis as this may result in unwanted conscious or subconscious favouring of a specific case study area(s).

(b) Accessibility

1- Introduction of transportation modes should be determined according to the local context (travel distances, surrounding land uses and infrastructure)

2- Accessibility may be enhanced by mixed land-uses, short travel distances and promotion of walkability.

26

(c) Sense of place

1- The sense of place within an area should be carefully analysed and consider various elements, including, the level of crowdedness.

2- The sense of place should be analysed in both private and public spaces as they often differ from one another, and from person to person, in the Global North and Global South.

(d) Public participation in decision-making processes

1- The shift away from a purely top-down approach to a combination between a top-down and bottom-up approach may lead to the potential enhancement and improved understanding of social sustainability.

2- An enhancement of the level of trust between spheres of government and residents may be essential and should be improved. As trust is increased, the chance of the local residents rising up against the government may be reduced.

(e) Social cohesion and wellbeing

1- Social sustainability stretches further than the public realm. Private spaces should also be included when analysing social sustainability.

2- The level of safety and unity should be upheld to ensure a strong sense of social cohesion and wellbeing amongst residents.

Throughout the research article, it was highlighted that there are multiple social sustainability and Planning similarities and differences experienced between the two case study areas; Amsterdam (Global North) and Matlwangtlwang (Global South). It may thus be questioned whether we are comparing apples and oranges. Both case study areas apply the same social sustainability and Planning themes but the practical implementation differs, due to their unique, local contexts.

Word count: 9993

27

Reference list

Alexander, E. R. 2016. There is no planning – only planning practices: notes from spatial planning theories. Planning Theory, 15(1):91–103.

Ameen, R.F.M. & Mourshed, M. 2019. Urban sustainability assessment framework development: the ranking and weighting of sustainability indicators using analytic hierarchy process. Sustainable Cities and Society, 44(1):356–366.

Arnett, H. 2017. The challenges in quantifying social sustainability at a neighbourhood level, Cities & health, 1(2):139-140.

Association of collegiate schools of planning. 2014. Guide to undergraduate and graduate education in urban and regional planning. 20th ed.

https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.acsp.org/resource/collection/6CFCF359-2FDA-4EA0-AEFAD7901C55E19C/2014_20th_Edition_ACSP_Guide.pdf Date of access: 08 May. 2019.

Basiago, A.D. 1999. Economic, social, and environmental sustainability in development theory and urban planning practice. The environmentalist, 19(1):145-161.

Beck, A. & Crawley, C. 2002. Education, ownership and solutions: the role of community involvement in achieving grass roots sustainability. http://www.regional.org.au/au/soc/2002/5/beck.htm Date of access: 16 Apr. 2019.

Blair, E. 2015. A reflexive exploration of two qualitative data coding techniques. Journal of methods and measurement in social sciences, 6(1):14-29.

Carmon, N. 2013. The profession of urban planning and its societal mandate. (In Carmon, N. & Fainstein, S., ed Policy, planning and people: promoting justice in urban development Philadelphia: Penn Press. p. 1-21.

Centraal bureau voor de statistiek. 2008. Kerncijfers wijken en buurten 2004-2008.

https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/81903NED/table?ts=1562157331261 Date of access: 03 Jul. 2019.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. 2018. Research methods in education. 8th ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

De Vos, A.S., Strydom, H., Fouche, C.B. & Delport, C.S.L. 2011. Research at Grass Roots. 4th ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

Dempsey, N., Bramley, G., Power, S. & Brown, C. 2009. The social dimension of sustainable development: defining urban social sustainability. Sustainable Development, 19(1):289-300.

Efroymson, D., Ha, T.T.K.T. & Ha, P.T. 2009. Public spaces: how they humanize cities. 1st ed. Dhaka:Healthbridge-WBB Trust.

Eizenberg, E & Jabareen, Y. 2016. Social Sustainability: a new conceptual framework. Sustainability, 9(68):1-16.

Eizenberg, E., & Shilon, M. 2016. Pedagogy for the new planner: refining qualitative toolbox. Environment and Planning B, 43(1):1118–1135.

Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O. & Basson, M. 2018. Reimaging socio-spatial planning: towards a synthesis between sense of place and social sustainability approaches. Planning Theory, 17(4):514–532.

Fainstein, S. 2000. New directions in planning theory. Urban Affairs Review, 35(4):451-478.

28

Findley, L. & Ogbu, L. 2011. South Africa: from township to town.

https://placesjournal.org/article/south-africa-from-township-to-town/ Date of access: 02 Jul. 2019.

Frith, A. 2011. Matlwangtlwang. https://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/475007 Date of access: 03 Jul. 2019.

Garcia, L.A. & Rocco, R. 2015. Future perspectives for development in the global south: how can urban planning and design help governments be more effective in promoting/achieving fair and sustainable development in their societies?

https://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/object/uuid:c8d0d928-7a33-4782-8300989f5fba22b2/datastream/OBJ/download Date of access: 01 Mar. 2019.

Gemeente Amsterdam. 2018. City data.

https://data.amsterdam.nl/data/?modus=kaart¢er=52.3668592%2C4.8992916&lagen=tar%3A1%7 Cbgt%3A0%7Cwinkgeb%3A1%7Cbiz%3A1&zoom=9 Date of access: 30 Jun. 2019.

Gibb, R. 2009. Regional integration and Africa’s development trajectory: meta-theories, expectations and reality. Third World Quarterly, 30(4):701-721.

Gläser, J. & Laudel, G. 2013. Life with and without coding: two methods for early-stage data analysis in qualitative research aiming at causal explanations. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung, 14(2):1-38.

Google maps. 2019. Matlwangtlwang Steynsrus.

https://www.google.com/maps/place/Matlwangtlwang,+Steynsrus,+9515/@27.9463406,27.5394572,15z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m5!3m4!1s0x1e923554c8c3f747:0xf3b1afa310e7bc25! 8m2!3d-27.9432838!4d27.5510522 Date of access: 20 Jun. 2019.

Gürel, E. & Tat, M. 2017. SWOT analysis: a theoretical review. The journal of international social research, 10(51):994-1006.

Jacobs, J. 1961. The life and death of great American cities. New York: Vintage books.

Jeekel, H. 2017. Social sustainability and smart mobility: exploring the relationship. Transportation Research Procedia, 25(1):4296–4310.

Kacowicz, A.M. 2007. Globalization, poverty and the north-south divide. International studies review, 9(4):565-580.

Kuhlman, T. & Farrington, J. 2010. What is sustainability? Sustainability, 2(1):3436-3448.

Laverack, G & Wallerstein, N. 2001. Measuring community empowerment: a fresh look at organizational domains. Health promotion international, 16(2):179-185.

Lynch, K. 1960. The image of the city. 1st ed. Massachusetts:The M.I.T. Press.

Maguire, M. & Delahunt, B. 2017. Doing a thematic analysis: a practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISHE-J: The All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 9(3):3351- 3365.

Miles, M.B. & Huberman, A.M. 1994. Qualitative data analysis. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Moberg, M. & Widen, I. 2016. Integrating Social Sustainability within the design of a building: a case study of five projects at an architectural firm. Gothenburg: Chalmers university of technology. (ThesisMaster).

Natarajan, L. 2017. Socio-spatial learning: a case study of community knowledge in participatory spatial planning. Progress in Planning, 111(1):1–23.

Olakitan Atanda, J. 2019. Developing a social sustainability assessment framework. Sustainable cities and society, 44(1):237-252.

29

Omer, K. 2017. Rethinking transect walk and community mapping process. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317590701_Rethinking_Transect_Walk_and_Community_M apping_Process Date of access: 03 Jul. 2019.

Perovic, S. & Folic, K.N. 2012. Visual Perception of Public Open Spaces in Niksic. Social and Behavioural Sciences, 68(1):921-933.

Pijoos, I. 2019. Five arrested for Steynsrus unrest. https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/southafrica/2019-04-16-five-arrested-for-steynrus-unrest/ Date of access: 24 Jul. 2019.

Pinson, G. 2007. Urban and regional planning. Encyclopedia of governance, 2(1):1005-1007.

Rashidfarokhi, A , Yrjänä, L., Wallenius, M., Toivonen,S., Ekroos,A. & Viitanen, K. 2018. Social sustainability tool for assessing land use planning processes. European Planning Studies, 26(6):1269–1296.

Reuveny, R.X. & Thompson, W.R. 2007. The North-South divide and international studies: a symposium. International Studies Review, 9(1):556-564.

Rifkin, S.B. 1990. Community participation in maternal and child health/ family planning programmes: An analysis based on case study materials. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Robergs, R.A. 2010. Introduction to empirical research. http://www.unm.edu/~rrobergs/604Lecture3.pdf Date of access: 01 Sept. 2019.

Rogge, N., Theesfeld, I. & Strassner, C. 2018. Social sustainability through social interaction- a national survey on community gardens in Germany. Sustainability, 10(1085):1-18.

Sanei, M., Khodadad, M. & Ghadim, F.P. 2017. Effective instructions in design process of urban public spaces to promote sustainable development. World journal of engineering and technology, 5(1):241-253.

Savini, F., Boterman, W.R., Van Gent, W.P.C. & Majoor, S. 2016. Amsterdam in the 21st century: geography, housing, spatial development and politics. Cities, 52(1):103-113.

Service Civil International. 2018. Picturing the global south- the power behind good intentions. (In Weidinger, V. & Schallhart, T., ed. a toolkit for critical volunteering organisations and global education practitioners. Vienna: Erasmus+. p. 1-109).

TEDx Talks. 7 Apr. 2014. Amanda Burden: How public spaces make cities work. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j7fRIGphgtk&t=4s Date of access: 02 Mar. 2019