24 minute read

The Plac e You’ ve Ci rc le d the Globe to Find

Li ve on the world’s most pr ivate isla nd Estate-s ty le home s on Fisher Island ’s pr is ti ne shoreline, steps from the Spa Internaz ionale, racquet club, and aw ard-wi nning golf course. The Residences’ unprecedented amenit ie s and white-glove serv ic e set a new standa rd , wi th fi ve -star dining , re sort-s ty le po ol s, and a wa terf ront lounge . It ’s the pinnacle of coas ta l li vi ng , minutes from Mi ami bu t

In Conversation: Ruth Rogers and Marc Newson

RUTH ROGERS: Marc, you’ve been enlisted to curate a selection of features for the Gagosian Quarterly. How did you go about selecting the stories you wanted to include?

MARC NEWSON: I wanted to keep a sense of levity throughout, avoiding anything terribly heavy-handed or academic. There’s no overarching thesis per se, it’s more a compendium of topics that I’ve been thinking about. For instance, I wanted to include a piece about my favorite film—

RR: Ever?

MN: Absolutely. It’s just so fantastic. The film is Il Sorpasso [1962], by Dino Risi. It stars a young Vittorio Gassman and Jean-Louis Trintignant.

RR: Oh, I love Vittorio Gassman.

MN: If you’ve not seen the film, you must. It’s one of the first road-trip films. Gassman plays this loose cannon—a real happy-go-lucky, carefree guy on the lookout for anything that might add some excitement to life. He drives a Lancia Aurelia convertible in the film, which I love. The film starts in Rome, with Gassman driving around the city, which is absolutely empty and sleepy. He’s just cruising around looking for something to do and he eventually sees a window open in an apartment. He starts throwing stones at the window and someone comes out, and it’s Jean-Louis Trintignant. He befriends this guy and somehow coaxes him out of the apartment, dragging him away on this road trip.

RR: When did you first see the film?

MN: A friend of mine was able to get me a copy of it a long time ago, but it was in the original Italian with no English subtitles. I think you can find it now with subtitles, but I’ve only ever seen it in Italian.

RR: I love that era in Italian film.

MN: Dino Risi was a wonderful director, but he’s not that well-known outside Italy.

RR: So what else are you doing with the magazine?

MN: I’ve asked my friend Alison Castle to write an essay about the history of concept cars done by artists, architects, and others coming to the automobile world from outside that industry.

RR: I know that you’ve designed a car in the past—the Ford 021C concept car [1999]—and am I right in thinking that you’re working on another one with Ferrari?

MN: Jony [Ive] and I are partnering up with Ferrari for a series of projects. It’s going to be a longterm collaboration, part of our work with the LoveFrom collective. I’m really excited to be working again with this quintessentially Italian brand, and given that they’re so successful and publicly traded now, it’s great that they’re still producing in Italy. I’ve been working in Italy for around thirty years now.

RR: Have you?

MN: Yeah, one of my first gigs outside of Australia was in Italy. I had some early successes there and started working with a lot of those Italian brands, like Cappellini and B&B Italia.

RR: Did you live there?

MN: Never. I lived in Paris at the time. I probably should have but I had personal reasons for living in France.

RR: Italy is a place that I don’t think I’ll ever tire of. It’s incredible how, for instance, just going to a farm, you go down these really rural roads, and it’s dusty and it’s rocky and it’s got fields and whatever, and then you park the car and you walk into the kitchen where they’re making parmesan, and it’s like rocket science! They could be making a nuclear weapon—they’ve all got hairnets on, they’ve all got white aprons, everything is so orderly. It speaks to a real respect for their production process. There’s a sense of pride that you would not get in so many other places.

MN: And there’s a kind of conservatism to it. It’s like Japan in that way. The two countries really share many qualities, culturally.

RR: There’s a bit of that in France as well. I’m thinking of Laguiole, the knife producers who make these incredible pieces in the same manner as when they started, in the nineteenth century.

MN: France is a really interesting example because they’ve done an amazing job at turning their savoir faire into a marketable product. They’ve been able to engage their past in a way that is now synonymous with luxury. It’s been parlayed into a meaningful, commercial, modern thing. Whether we agree about the definition of luxury—

RR: What do you think is luxury? I was asked that the other day.

MN: Me too. What’s luxury?

RR: I said, Going to a museum that’s closed [laughter].

MN: That’s such a great answer.

RR: That is the greatest luxury.

MN: Wow. I’ve been asked that question so many times and I always say something really boring, like “quality” or something. But to go back a little bit, that’s what I was trying to say about Ferrari: they’re one of those companies that have this savoir faire. They have their thing and their way, and they’re so intrinsically linked to Italy.

RR: In that context, it’s interesting and I imagine quite tricky to balance the dictates of the past, maintaining that control while also pursuing something in the future—an ambition that’s required for business.

MN: You’re absolutely right to point that out, and it does require an incredible amount of control. For many of these brands, like Ferrari, there’s this completely new metric based on no rather than yes. I can’t recall the exact number, but Ferrari has set a finite number of cars that they produce in a year, and they won’t do more.

RR: That reminds me of a conversation I was having with Wolfgang Puck. He came in here a few months ago and I said, “Wolfgang, I want to be like you. I want to have forty restaurants.” And he said, “Ruth, I want to be like you and have one” [laughter]. And both of us are wrong: I don’t need forty, but I don’t think he does want just one. He wouldn’t have had forty otherwise.

MN: The grass is sort of always greener—

RR: Yeah, you’re always thinking—

MN: But also, there’s a wonderful elegance in the control you’re able to have at this scale. Any expansion comes at a price. I’m an advocate of the one-restaurant philosophy. RR: I agree. I’d rather have the one. Somebody told me yesterday, if you go into the supermarket you can choose between twenty different types of apples or ten types of tomatoes or whatever, and people think that’s what luxury is, having choice. But in fact you’d rather have somebody select the best tomato, stock that one tomato and simplify life a bit, right?

MN: For us, definitely. I’m not sure everyone would agree, but you and I, in our respective fields, I think we strive for simplicity. Simplicity in its best form is incredibly elegant and incredibly sophisticated. And, as you know, incredibly difficult.

RR: And difficult. I was going to say the same thing.

MN: I work like a designer sometimes and I work like an artist at other times. And these are radically different ways of working—a designer has structure, rules, parameters, while an artist has virtually none of these limitations. Many people probably assume that working like an artist is easier because you don’t have a client, you can do what you want, whenever you want, however you want. But it’s the exact opposite.

RR: Structure and restraint go a long way.

MN: Yeah, when you work within a box, you start there and you end there, and you can’t go there and you can’t—I like that structure.

RR: Yes, that applies to the restaurant as well. Obviously for the ingredients there’s the restraint of seasonality, their availability, the size and versatility of the kitchen itself—all of these things matter on a day-to-day basis. It’s challenging, but also what makes it worthwhile. On top of that, there are the clients themselves, with everybody coming at once so you have to perform. It’s quite theatrical.

MN: It’s very difficult for people to understand that in a way, it’s more about what you can’t have than what you can have. That’s a much more considered place to start.

RR: We used to take our whole family to this hotel on this little island off the coast of Tanzania. We would go there for what we didn’t get. You didn’t get music, you didn’t get Wi-Fi, you didn’t get tennis courts, you didn’t get nightlife—essentially, all you could do was walk the perimeter of the island. And taking those walks remains such a fond memory. I agree completely about the elegance of what you can’t have.

MN: It’s a healthy discipline to embrace, if you can.

A layperson developing an interest in classic cars quickly discovers that the more one learns, the less one knows. Car culture is an insular world that, while by no means closed to outsiders, can seem impenetrable to anyone who might wonder, say, how it is that a four-cylinder can be more powerful than a V8. If that poor soul doesn’t already understand how combustion engines work and what turbocharging means, the answer will quickly devolve into nonsense. By and large, car people have spent their lives absorbing everything there is to know about cars, and in an advanced connoisseur this knowledge spans history, science, engineering, restoration, design, and aesthetics and includes an encyclopedic knowledge of car models, brands, coach builders, and designers. It seems like a lot because it is. You just have to dive in.

The point of entry can be anything as long as it draws you in. For art lovers, I suggest an exploration of some of the exceptional cars that were designed by people not working in the automotive industry: artists, industrial designers, architects—people known in other fields, or even self-taught. This is a very small niche in the car world but a fascinating one, and a perfect area of study for amateurs in the creative sphere. Indeed, the crossover between cars and art has more famously been the other way around: artists making art from actual cars. Two of the most famous examples are César Baldaccini and John Chamberlain, who worked extensively with car bodies. Gabriel Orozco, Erwin Wurm, and Maurizio Cattelan have made notable use of cars. (In 2000, Cattelan, who has said he “always wanted to create a rhetorical car,” wrapped the body of an Audi sedan around a tree trunk as if the tree had sprouted right up through it.) Less known but no less impressive examples include Ichwan Noor’s VW Beetles compressed into perfect spheres and cubes, a series begun in 2011, and Marcus Bowcott’s Trans Am Totem, a public installation in Vancouver (2015). The artist and filmmaker

Matthew Barney has featured classic cars, and sculptures made from them, in many of his films. Ant Farm’s Cadillac Ranch in Amarillo, Texas (1974), features ten graffiti-tagged Cadillacs half buried in the ground, lined up like headstones or monoliths. And the list goes on.

In a more liminal space hovering between the art and the car worlds are numerous examples of commercial cars painted by artists. Over the span of her career, the French artist and textile designer Sonia Delaunay painted several cars, including a 1924 Bugatti Type 35 and a 1925 Citroën, with adaptations of her textile designs. In the mid-1960s, Judy Chicago, in the wake of her husband’s death in a car crash, enrolled in auto-body school and created a remarkable series of painted car hoods. Since 1975, BMW has commissioned oneof-a-kind cars by artists including Alexander Calder, David Hockney, Jenny Holzer, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol, but aside from the ice cocoon that Olafur Eliasson created for the BMW H2R in 2007, the artists’ interventions were limited to painting the bodies. Ironically, some of these unique works of auto art are valued at a fraction of what the artists’ work draws at auction. Car collectors tend to be interested in a car’s provenance, restoration quality, and racing history, while many art collectors habitually invest in pieces that can be displayed on a wall or a pedestal; artist-painted production cars exist in a kind of no-man’sland.

Perhaps most fascinating, though, is a third category, where automobiles collide with art and design right on the drawing board—in the hands of industry outsiders. Take, for example, the Phantom Corsair and the Norman Timbs Special, both superb examples of what self-taught amateurs can achieve. The former, created in 1938 by Rust Heinz (grandson of ketchup magnate H. J. Heinz), is a lavish riot of Art Deco drama that really cannot be described in words. I’m tempted to say it looks like a cartoon robot shark on wheels with a hippopotamus’s snout, but that doesn’t begin to do the job. The car’s swooping lines and fanciful detailing are really quite stunning. Devoid of running boards, with flush fenders, fully skirted wheels, a split front windscreen, and hidden buttons rather than door handles, the Phantom Corsair was not just ahead of its time but outside of time altogether. It also had a 190-horsepower V8 engine, automatic transmission, and advanced suspension, and despite weighing 4,600 pounds, it could reach speeds of well over 100 miles per hour. Considering that Heinz had no experience in design or business, his achievement is quite incomparable—though it likely wouldn’t have been possible without Heinz money. His plans to put the car into production, and the promise of a bright future in automotive design, ended with his death in a car crash in 1939.

The legendary French-American designer Raymond Loewy was a quintessential polymath, designing buildings, logos, Coca-Cola bottles and vending machines, locomotives, refrigerators, nasa spacecraft interiors, aircraft livery, furniture, textiles, wallpaper, watches . . . the list is ridiculous. Loewy called his design philosophy “maya”: “most advanced yet acceptable.” He had a keen instinct for the ideal balance of the familiar and the innovative, introducing accessible and realistic yet future-forward designs. During his career, he designed several cars, the most interesting of them surely the BMW 507 Custom Build of 1957. Described as “a competition sports car with Gran Turismo characteristics,” his prototype was built on the chassis of the 507 but otherwise bore no resemblance to the original, designed by Count Albrecht von Goertz. Here Loewy achieved a rare synthesis of futurism and familiarity, with novel features such as rectangular headlights, a honeycomb grille, and a swooping oval rear window. From behind, the car looks rather like a personal spaceship, but viewed from the side it looks reassuringly like a sports coupe. Loewy’s 507 wasn’t intended for production and remained a unique piece, but its influence can be seen on the Avanti that he designed for Studebaker in the early 1960s.

The Bisiluro Damolnar was a race car designed in 1955 by Carlo Mollino in collaboration with Mario Damonte and Enrico Nardi. Though best known as an architect and to a lesser extent as a furniture designer and photographer, Mollino was a true Renaissance man whose interests were remarkably catholic. His Bisiluro (Italian for “twin torpedoes”) sports a single seat, an asymmetrical form, a left-mounted engine, and an exposed frontal radiator. Some deem it a masterpiece, others the weirdest car to have raced Le Mans. It was aerodynamic, fast, and exceptionally lightweight—so much so that when it raced in the 1955 24 Hours of Le Mans, it was literally blown off the track and severely damaged as a result. It has since been restored to its original resplendent glory and now, fittingly, resides in a Milan science museum named after Leonardo da Vinci.

In fact, a number of prominent architects have tried their hands at designing cars, although in many cases these projects began and ended at the drawing board. In 1920, Frank Lloyd Wright sketched out the Cantilever Car, which shared with many of his building designs a suspended roof projected from a central pillar, which allowed for the windows to wrap around the cabin uninterrupted by posts. Adolf Loos’s inspired but somewhat clunky contribution, which he modeled for Lancia in 1923, had a third row of seating elevated above the first two rows, with its own little windshield for unobstructed views. Walter Gropius’s attempts for Adler in 1929 gained more attention than those of Loos, but they were most notable for prioritizing elegance-enhancing superficial features over aerodynamics. Even Jean Prouvé threw his hat into the ring, but alas, little is known about his concept aside from rudimentary sketches.

More interesting yet is Gio Ponti’s 1952 foray into automobile design. Intended for an Alfa Romeo 1900 chassis, his Linea Diamante bears absolutely no resemblance to an Alfa, or to any other mid-century car full stop. Ponti’s aim was to concoct an antidote to the swollen, curvaceous, small-windowed cars that were ubiquitous at the time. The Diamante is an unbearably endearing little fellow, and well ahead of its time, too. With its flat-paneled body, low hood, big square and triangular windows, and generous hatchbackstyle trunk, it foreshadowed the boxy compact cars that would come along in the 1970s and ’80s. The white line that encircles the car isn’t just for decoration: it’s a rubber bumper to help prevent dings from any angle. Ponti sought to have the car produced, but both Carrozzeria Touring and fiat turned him down, dashing his hopes to see the Diamante come to life. Sixty-five years later, fiat made a conciliatory gesture by collaborating on the creation of a 1:1 model with Domus, the architecture and design journal that Ponti founded, on the occasion of its ninetieth anniversary.

Of R. Buckminster Fuller’s many talents, architecture is probably the one for which he is most renowned, particularly thanks to his popularization of the geodesic dome. Fuller was also a great thinker, futurist, and inventor who developed a series of projects under the name “Dymaxion,” a portmanteau of the words “dynamic,” “maximum,” and “tension,” collectively referring to his goal of “maximum gain of advantage from minimal energy input.” First came a prefab house, then, in the early-to-mid-1930s, a car. Fuller’s Dymaxion work continued to evolve for decades, embracing the ambition to “make the world work, for 100% of humanity, in the shortest possible time, through spontaneous cooperation, without ecological offense or the disadvantage of anyone.” Irrespective of form or field, his projects always began with a question, and that question usually related to how humanity could best be served and advanced by an invention. True to this principle, the Dymaxion car was both democratic and progressive: it would carry eleven passengers and was intended to eventually be upgradable, thanks to its aerodynamic teardrop shape, into a flying machine by the addition of wings. With two wheels in the front and a third in the rear that steered the car, the Dymaxion could turn on a dime; Fuller imagined that once capable of flying, the car could easily extract itself from a traffic jam, take off like a bird, and sidle back onto the road at a more convenient location. Three prototypes were made, but physics and reality were the enemies of this ambitious project: the Dymaxion was dangerously unstable on its three wheels, and flying cars were, and remain, a strictly quixotic proposition.

Renzo Piano’s VSS modular concept car, commissioned by fiat in 1978, reimagined automobile construction from the ground up, with the main part of the chassis consisting of a load-bearing internal frame and interchangeable front and rear elements. The exterior panels, made of plastic, were all hung from the central chassis, allowing the same base elements to be made into an exceptionally lightweight and compact sedan, hatchback, station wagon, etc. Piano’s project, made in collaboration with I.DE.A Institute, was innovative on an efficient, economic level; it was a “concept” car in the literal sense of the term, exploring how engineering could be optimized for a utilitarian car, but above all it was genuinely conceived to be producible. A working prototype was made and tested, but although fiat didn’t end up putting the VSS into production, the concept’s hatchback version came to life in the form of the Tipo, released in 1988.

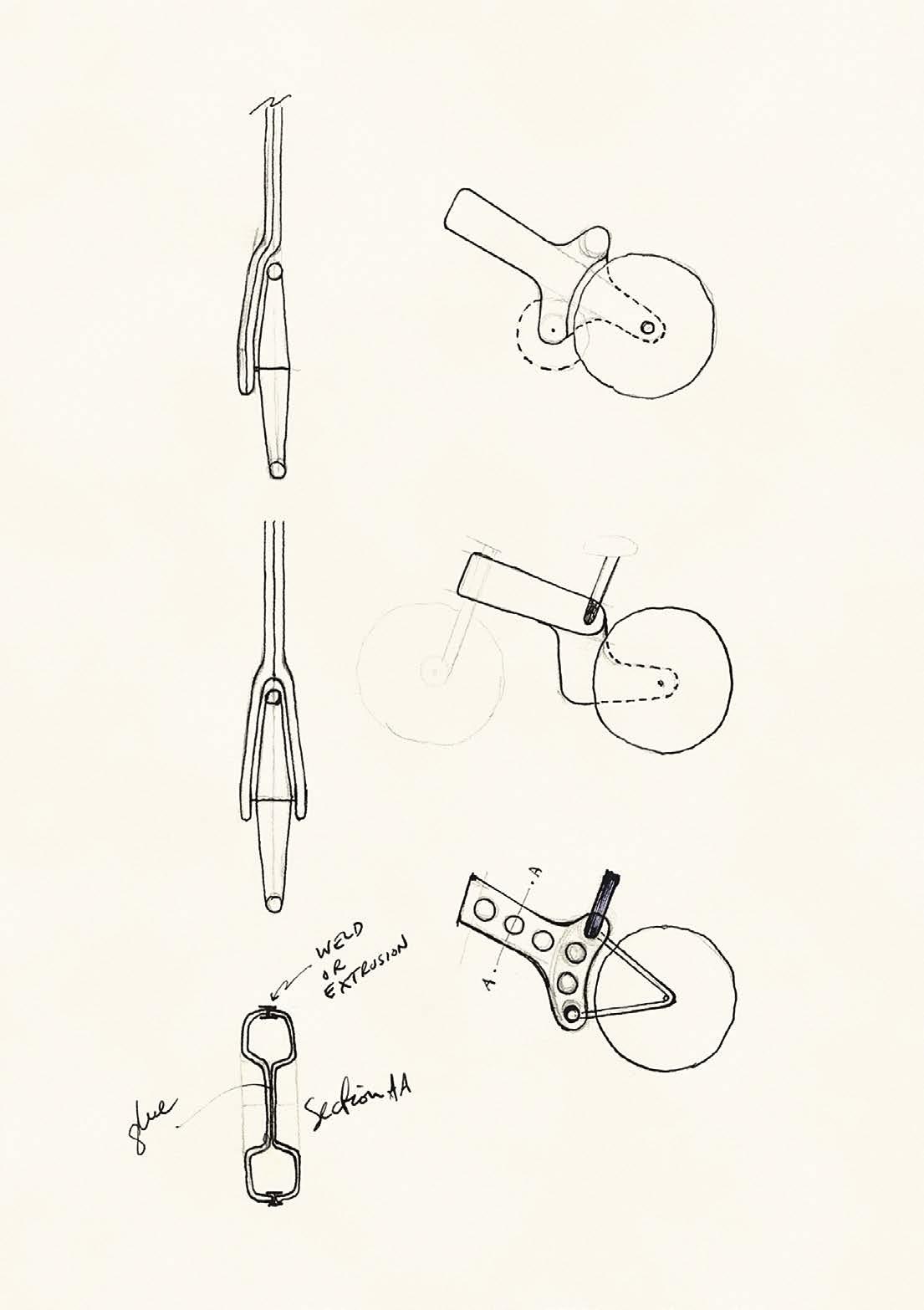

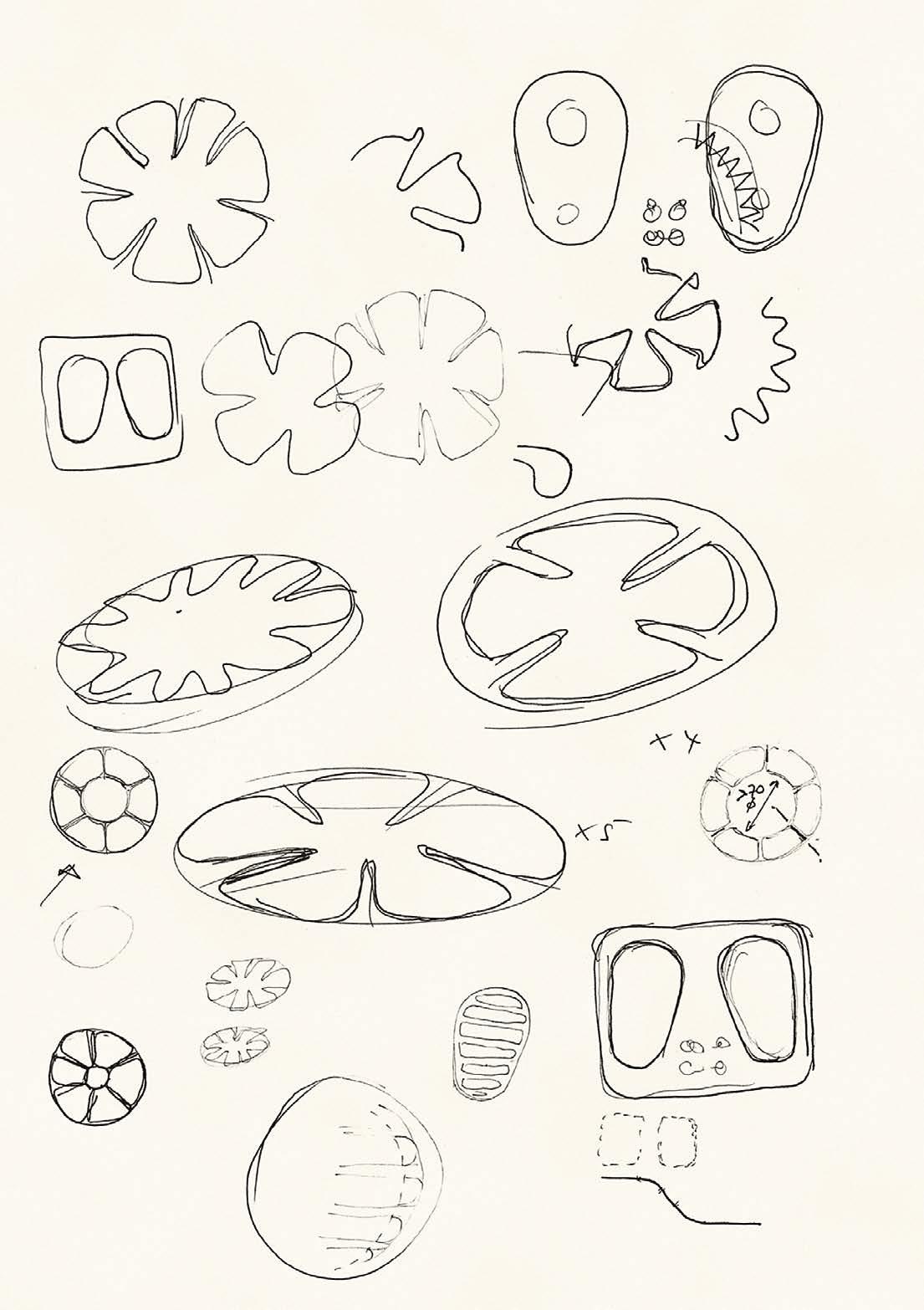

Where Piano’s fiat envisioned itself as a way to revolutionize how cars are manufactured, Marc Newson’s Ford 021C, of 1999, was an exercise in imagining how a car could profoundly elevate the user experience. A polymath in the tradition of Loewy, Newson has designed everything from a fountain pen to an airplane, with an abundance of furniture and product designs in between. When he was hired by Ford design director J Mays to create a concept car, he mostly got free reign, thanks in part to the project being kept largely out of view from executives who might not have understood its value. Newson created a full-scale clay model from computer models based on drawings, and the final working prototype was built in the legendary Carrozzeria Ghia in Turin. The car’s minimal, symmetrical form belies its innovative features, such as swivel seats, rear-hinged doors that open to a surprisingly spacious, completely pillarless interior, optical-fiber ceiling lighting, a height-adjustable dashboard, simple aluminum touch buttons for door handles, and a trunk that opens like a drawer. The analog controls recall Newson’s Ikepod watches, and indeed every detail of the car has a signature Newson touch (he even designed the custom gunmetal-colored Pirelli tires, whose treads match the pattern of the ceiling and carpet). By starting with an empty cabin and inserting only necessary elements reduced to their simplest forms, Newson created a car designed to give its passengers comfort, ease, space, and nothing superfluous. It’s a great shame that the 021C was never put into production, but such is the fate of car concepts that dare to truly rethink how a car should be.

Opening spread: Bisiluro Damolnar, 1955, designed by Carlo Mollino in collaboration with Mario Damonte and Enrico Nardi.

Photo: De Agostini/DEA/MUST/ Getty Images

Previous spread, left: Voiture Minimum, 1936, rendering based on design by Le Corbusier.

Photo: Antonio Amado

Previous spread, right: Linea Diamante, 1952, rendering based on design by Gio Ponti.

Photo: Domus, Italy

Opposite: Z-102 Cúpula, 1952, designed by Pegaso and committee of students from Spain.

Photo: courtesy Louwman Museum, the Hague, Netherlands

This page, above: Quasar-Unipower, 1967, designed by Quasar Khanh. Photo: Reg Lancaster/Express/ Hulton Archive/Getty Images

This page, below: Ford 021C Concept Car, 1999, designed by Marc Newson for Ford Motor Co. Photo: courtesy Ford Motor Company

Speaking of rethinking, the Spanish automaker Pegaso reasoned well outside the box with its Z-102 Cúpola of 1952. Though primarily a manufacturer of trucks and buses, Pegaso made some limited-production sports cars in the 1950s, and for the Cúpola it tried something truly inspired: the company asked Spanish students to submit their ideas for what the sports car of the future might look like and then brought to life what was essentially a crowdsourced car. The students clearly had rockets and flying saucers on their minds, but rather than a mash-up or a pastiche, the Cupola is an absolute breathtaker. Against all odds, the curvaceous yellow body, red-walled tires, shiny, perforated side exhausts, straight-skirted fenders, top-hinged windows, and boxy, bulbous rear windscreen come together in a kind of beautifully coherent alchemy.

Examples of imaginative cars such as these, designed by automotive outsiders, are far fewer than one would think or hope. It makes perfect sense to cast a wide net to find new ideas, but the car industry is not daring. In the project description for the VSS, Piano writes, “Why entrust this task to an architect . . . rather than one of the many successful automotive engineers fiat could count on? Probably the choice was motivated by the belief that to get real innovation you had to draw on external resources, free from the technical constraints and production limitations affecting every car.” Indeed, outsiders have created some of the most interesting car concepts in automobile history, ranging from the feasible (like many of the above), to the handmade work of art (see Serge Mouille’s retro-futuristic Panhard Le Zebre of 1953), to the outlandish (the 1967 Quasar-Unipower, by designer and engineer Quasar Khanh, is a fantastic example of an uncarlike vehicle that is still, somehow, a car). But pushing them through to production is another matter entirely. Car companies are profit driven and risk averse, which makes them poor purveyors of anything but incremental, market-tested innovation. Features cherrypicked from concept cars do get introduced, of course, and the public’s fascination with concept cars isn’t lost on automakers. But it takes a different kind of thinking entirely to imagine that a car could have its very own identity, envisioned by its creator just like a work of art.

Richard Geoffroy and I bonded over our admiration of Japanese culture, particularly the high value placed on skill and craft, and the obsession with minute detail. The process behind IWA exemplifies Richard’s unique approach: from the bottle to the brewery, he places a similarly high value on design.

The parameters were fairly defined in terms of the functionality of the bottle: we wanted it to look like a bottle and have a recognizable silhouette, and be subtle and sophisticated. We were more playing with materials and finishes to achieve a subtle elegance.

—Marc Newson

We considered history within the context of local culture. The roof directly references the traditional houses of the Gokayama region. Historically, the people and the koji yeast live together under one roof.

—Kengo Kuma

I always had a fascination for Kengo Kuma’s contribution to reviving the Japan-ness of Japan’s architecture: deeply and proudly rooted yet reaching out to the world. His philosophy has been a source of personal inspiration in creating IWA. In actual fact Kengo’s collaboration with IWA is beyond architecture; I am grateful he keeps guiding me through the arcanes of the cultures of Japan.

— Richard Geoffroy

What makes Dino Risi’s 1962 Italian road comedy Il Sorpasso such a lean, dexterous, lovely, and ultimately sad work? It’s not quite the heresy it may sound like to the Sorpasso fan (and I’d consider myself one) to say that the film is low on big laughs. Compared to the extended gags and guffawinducing situations that pile up in Pietro Germi’s Divorce Italian Style (1961) and Seduced and Abandoned (1964), or in Mario Monicelli’s Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958), the comedy in Il Sorpasso is played at a far more muted level. I find it helps to approach the film more in the vein of a Jacques Tati comedy: don’t expect outsized reactions. If they come, they come. Stay for the steady, clockwork development of character and see what happens to your body when, having gone along with a plot for as long as it can be pushed, you find yourself wondering, Well, what next? And then everything crashes down, one of the greatest 180-degree twists in cinema history unfolds, and you’re beside yourself in sudden emotion, a total shift in perspective in what you only took for a charming road jaunt.

An impulsive, swaggering drifter, Bruno (Vittorio Gassman), convinces a meek, shy law student, Roberto (JeanLouis Trintignant), to leave his books behind and set out, the two of them, on a spontaneous road trip across Italy. Most of the film involves the gradual melting of Roberto’s defenses as he comes to embrace what Bruno (for better and especially for worse) represents: “the easy life”— obligations later, live now.

It is a 105-minute film. For 104 minutes it feels like a meandering short story. Then the final minute happens and everything brutally snaps into place. It’s strange how a movie can take on such crisp shape with such a seemingly arbitrary finale, which yet, on reflection, makes the entire venture make perfect sense: Obviously this is the only logical way out. This is what happens when you play with fire, when you live life nihilistically and without aim, just go go go. Everything must stop eventually. It’s physics.

Bruno acts as the most incorrigible Don Juan to pretty women while saving his strutting alpha-male bit for threatened men who are just as cocksure as he is but lack his particular fluidity-of-gesture or solidityof-build. Meanwhile Roberto’s just along for the ride, observing Bruno overtake cars with obnoxious flourish in his Lancia Aurelia convertible while honking madly on its unforgettable Woody Woodpecker–like horn. Roberto sees that people take to Bruno with a swiftness that he, a lowly grad student, envies. After all, isn’t there something wickedly admirable in a man who, to avoid getting a parking ticket for his obviously illegally parked car (which he can easily move), takes the parking ticket off another car illegally parked nearby and puts it on his? It’s the audacity of the action, the brazenness, the seductive effrontery to basic moral codes. But Bruno’s illusion unravels: turns out he’s not a thirty-something swinger but a middle-aged near-has-been who’s been married, and glumly, since he was twenty to a quick teenage fling (Luciana Angiolillo) whom he impregnated. This resulted in a daughter (Catherine Spaak) who, now eighteen, is romancing a middle-aged tycoon despised by Bruno for class and age-gap reasons.

Gassman’s vibrant performance as Bruno was stamped into the Italian consciousness, and “sorpasso” (which literally translates as “surpassing,” i.e., what hot-headed Bruno keeps doing to cars painfully slower than his on the road) quickly became the standard term for a certain brand of Italian man: quick-tempered, bon vivant, with fatal whiffs of the pathetic and adolescent hidden beneath a busy exterior. But the path to becoming a cultural milestone was far from set when the movie first opened. Gassman was box-office poison at the time, having just starred in Roberto Rossellini’s notorious flop Anima nera (Black soul, 1962). That movie had been such a fiasco that, according to screenwriter Ettore Scola in an interview with the Criterion Collection, moviegoers initially avoided the main Roman theater where Il Sorpasso was playing in December 1962, reacting with disgust when they saw the cinema still had Anima nera posters up with Gassman’s face plastered all over them. But the word of mouth quickly spread: this was a new beast of commedia all’italiana. Within a week, Scola says, the cinema was packed with people in hysterics at the antics of the wily Gassman. Perhaps the guys identified with the blustery oaf that Gassman represented, and the girls recognized his type, or plain desired it in that clandestine movie house manner. Gassman’s Bruno is a broad-chested man’s man with insider knowledge on how to game the system of life. He’s the kind of character who would be mercilessly satirized and mocked three years later in Richard Lester’s anarchic, brilliant, complicated film The Knack . . . and How to Get It, based on a play by the English playwright Ann Jellicoe. But there’s a specificity to Italy’s codes of masculinity. Bruno’s own life is a mess, naturally, but he doesn’t talk about that. He doesn’t have time to slow down, to reflect. That’s not something a real man does, with the fast car and the big balls. No sir. Not Our Guy. His armor must remain intact.

That is, until he finally connects with his estranged daughter. Or, until he finally forges a genuine platonic connection with another man by whom he does not feel threatened, a young man whom Bruno successfully pushes outside his meek shell and teaches to appreciate life’s rush. Until he finally forges a feeling that, for the first time in his life, may be love.

Maybe, it seems, he is maturing.

Then, continuing to play his dumb little road games in the last minutes of the movie, Bruno recklessly crashes his car off a rocky cliffside, killing Roberto, while he himself survives with a small cut on his face.

Who was the dead man?

Poor Roberto. He was played by the great Trintignant, who specialized in these weak-willed, shaky-limbed, yet secretly perverse boys, as any glance at his performances in Éric Rohmer’s My Night at Maud’s (1969) or Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970) will attest. He’s another kind of man: shy, romantic to a nauseating degree, afraid of saying something out of line. The love of his life is a neighbor named Valeria who lives across the street from him, but with whom he has never had a single conversation. He barely knows what she looks like; the locket photo he keeps in his wallet is blurry, taken of her in her apartment from a creepy Rear Window–y distance. It takes Bruno to shake Trintignant up and make him take some kind of action. And so he does. The joke: once he does call Valeria, she’s nowhere near the phone that she’s always hovering near; she’s at the beach, and can’t pick up. That’s okay, says Roberto to himself. He’ll just try once he’s back in Rome.

And now, that ending. Having Bruno be the one killed would make too much perfect neat sense. It would be unforgivably puritanical. Moral punishment would be meted out to the hell-raiser, and his meek buddy would think twice before calling that girl on the phone. And if both of them were killed . . . well, there’d be delicious irony, but that would fall on the side of the patly nihilistic. It would be too down. But having the hell-raiser survive? While his barely nascent charge goes fatally careening off the side of a cliff, stuck in the passenger seat? Now that’s cinema, which is to say: edging life. One life had ended just moments before: a life of safety, collusion, and conformity, a life that pledged faith to the institution of postwar Italian neocapitalism ushered in by the famous Italian “boom.” That was Roberto before the phone call, Roberto before Bruno. And another life had just been born: one of hard-won freedom, a life of damn-what-society-says, a life led purely by instinct and personal pleasure. But in that crash, all comes crashing down on Bruno, the seemingly chill, seemingly masterful teacher. Life is chancy. Life is savage. Life does not care if you’re planning to call your sweetie tomorrow. If you gamble, them’s the risks. That’s the nature of chance. Fuck around, find out, and don’t be surprised if the dice don’t come out in your favor—maybe next time, with a new Roberto, they will.

It’s a perfect tag to the story. It’s the only tag possible.

And now I’d like to know: while these two-days-that-feellike-a-week were unfolding, what was Valeria doing? What’s Valeria’s story? What was Valeria’s week of wonders?

Throughout: Stills from Il Sorpasso (1962), directed by Dino Risi. Photos, opening spread and previous spread: Fair Film/ Album/Alamy Stock Photo; photo, this spread, left: Picture Lux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy Stock Photo; photo, this spread, right: Mondadori Portfolio/ Bridgeman Images