10 minute read

Cowboy

The mythic West was pretty much over by 1910, when John A. Lomax published his seminal collection Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads. The big cattle drives from Texas to Fort Dodge, Kansas, had ended; the trails had been grassed over; roundups were by then confined to a few obscure valleys in southern New Mexico. “The last figure to vanish is the cowboy, the animating spirit of the vanishing era,” Lomax wrote. “He sits his horse easily as he rides through a wide valley, enclosed by mountains, clad in the hazy purple of coming night,—with his face turned steadily down the long, long road, ‘the road that the sun goes down.’” And there’s your photograph, although you couldn’t quite get those effects with a camera in 1910.

The proper cowboy picture requires a landscape, an impression of weather, a horse, and an outfit. “I see by your outfit that you are a cowboy,” says the dying cowboy to the passing buckaroo in “Streets of Laredo,” authored by the mighty Anonymous and included in Lomax’s book. What is it about that outfit? Anybody can wear a hat. Is it the jingle of his spurs? The tightness of his britches, the buttress of his chaps, the authority of his boots, the dash of his neckerchief? By 1949 the popular image of the cowboy had evolved from Diamond Dick to Frederic Remington to Tom Mix and William S. Hart and had now arrived at Gene Autry, the Singing Cowboy, with his enormous hats and elaborately embroidered suits, unlike anything ever seen anywhere near the range. It was then that a photo essay in Life, by Leonard McCombe, redefined the terms.

Clarence Hailey Long.

Photo: Leonard McCombe, courtesy the LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images

McCombe went to a ranch southeast of Amarillo, where he found some actual working cowboys. He photographed them doing cowboy things—roping, riding, branding—in a documentary style that had been the rule at Life for a decade but hadn’t yet affected motion pictures or advertising, at least in the United States. Suddenly America saw real cowboys standing in real dirt, secreting real sweat, laboring and lassoing and rolling cigarettes and reading western pulps in the bunkhouse. The text weighs the differences between them and movie cowboys, who could not be expected to ride sixteen hours a day, let alone castrate 50,000 calves and beat a thousand rattlesnakes to death over the course of their careers. The real cowboys wore standard Sears, Roebuck cowboy duds for the most part, but wore them better than anyone merely kitted up by the wardrobe department.

On the cover was Clarence Hailey Long, the star of the spread. The hat said cowboy but the rest of the package could maybe read existential, although nobody outside Paris would have known that word then. Actually, he does look weirdly French—a bit like Jean Gabin in a desert picture—with his baked skin and slitted eyes and thousand-mile stare; his roll-up and the curve it imposes on his mouth, almost but not quite a smile; and the polka dot foulard he wears around his neck, frayed at the edges, as elegant as anything you’d see on the rue de Rivoli. But if anyone was having those thoughts then, they remained private. Long and his friends personified western male authenticity, and their image made everyone in the image business take note. The feature reverberated through advertising for the next half-century and counting. To latter-day eyes it can look an awful lot like a Ralph Lauren fashion spread. Most famously, it led straight to Philip Morris’s forty-five-year campaign for its Marlboro brand (“The Big Job of Branding,” runs a section head in the Life piece), initially to reposition it from a woman’s to a man’s cigarette.

Richard Prince, Untitled (Cowboy), 2016, dye coupler print, 59 ½ × 89 ¾ inches (151.1 × 228 cm)

Lomax’s evocation is present somewhere, from the purple haze to the ring of mountains. Every scene was drawn from the common well of images also employed by western painters since the nineteenth century (filmmakers, too, although they had budgetary restrictions): roping a wild one, traversing the snowy pass, riding ’em across the stream, facing the sunset, tying up to the chuck wagon, and so on. They are a genuine artifice, meaning that every element of the picture actually existed on the physical plane at the time the photos were taken—even the cowboys were often actual cowboys, when actors couldn’t pass the realness test—but every scene constructed from those elements was staged. Even the horses were acting. The landscapes were reconfigured by long or wide lenses, the skies were enhanced in the darkroom, and who’s to say they didn’t now and then shift the moon a few degrees to the left?

Twenty-odd years into the campaign’s run, Richard Prince, then working in the morgue at Time- Life, began to photograph tearsheets of those ads, cropping them to eliminate verbiage and capitalize on their dynamic. The editorial and aesthetic aims worked together seamlessly; removing the text helped to emphasize the pure western horizontality of those scenes—or occasionally the vertical, as in tall grass or bucking bronco. Prince obviously wasn’t just making cowboy pictures; he was making pictures of cowboy pictures, or perhaps pictures of pictures of cowboy pictures. He was extracting and purifying a fixed image at large in the culture, by way of what was by then—after westerns had all but disappeared from movie houses and television—its most common and widespread vernacular representation.

There was much talk about appropriation at the time, and claims made on behalf of the artisans who had confected the Marlboro pictures—which missed the crucial point that Prince was not rephotographing the tearsheets because he wished he could have been making his own cowboy pictures. He was depicting and imposing his frame upon an object within his purview, namely an advertisement in a magazine. He might have been, say, dramatically cropping an architectural structure with his camera to emphasize some aspect of its construction, as Charles Sheeler did with his Bucks County barn. Prince was not using his camera to capture a fleeting scene in the instant before it dissolved, as was the norm for art photography then; that was a particular use of photography that had received disproportionate attention beginning in the mid-twentieth century. Instead he could be said to be harking back to the origins of photography, when William Henry Fox Talbot included a photo of a satirical print by Louis-Léopold Boilly, cropped and uncredited, in The Pencil of Nature in 1844.

Richard Prince, Untitled (original), 2009, original illustration, collage, and black cloth (bandana), 41 × 33 inches (104.1 × 83.8 cm)

The original Marlboro pictures are highly wrought objects, each one something like a cross between a western movie and a military painting, that are intended for instantaneous capture and recognition by the preoccupied eye. Every fine detail of their construction has been engineered to flick across the retina for a fraction of a second and register by way of sedimented memory. They cannot, therefore, challenge preexisting notions or impose a new way of seeing. Their job is to provide familiar comfort, to reach back to childhood and revive dormant sentiments and aspirations. The passive viewer is meant to triangulate between the cigarette brand and a primordial dream of self-reliance, effortless mastery, untrammeled masculinity, and independence from all threats to the id. All of that plus the romance of violence, since while guns are never pictured in the Marlboro ads, they are nevertheless present in every frame; the ten-gallon Stetson always brings along its friend, the bluesteel.

The transaction implicit in the ads is the true subject of Prince’s pictures—or one of them, anyway. Prince is interested in shared culture, the sort of culture that rejects the word and even the idea of “culture” while doing all the work that culture does: everything from muscle cars to fan memorabilia, from truck-tire planters to Instagram posts, from bad jokes to drugstore paperbacks. He is not engaged in a reclamation project; however he may actually feel about Trans Ams or nurse novels, he is not in the business of dusting them off and helping them out of the gutter. He is not a sentimentalist. His interest in those things begins with the fact that they have largely gone unexamined, because they lie beyond the pale of elite esteem. Like a cowboy, Prince is hog-tying wild animals, and then he drags them into the surgical light of galleries, where they can be assessed and purchased. Of course he alters them along the way—a philosophical inevitability, no matter how much he sticks with their given properties—but his interventions usually consist of helping them be more themselves, even, than they were in their original form. The bad jokes occupy the centers of large canvases as if they were commandments or epitaphs; the Instagram posts are blown up to a size commensurate with the egos that supply them; the Rastafarians are assigned the guitars the white spectator needs them to hold.

Richard Prince, Untitled (Cowboy), 2012–13, inkjet and acrylic on canvas, 59 × 36 inches (149.9 × 91.4 cm)

The cowboys were Prince’s first big project and remain his most classic subject. Most of his works involve cultural matters that first arose within his lifetime, but the cowboys go back to the beginnings of the nation. The Marlboro cowboys represent the refinement—the reification, you might say—of a national image slowly accreted over the better part of two centuries. The cowboy lurks deep in the back brain of people all over the world, including people who were never boys, never saw a cowboy movie, never saw a horse, never smoked a cigarette, never visited Texas or the continent in which it lies. And this despite the fact that cowboys have been steadily receding from the culture for fifty years. The canonical cowboy artists, Remington and Charles M. Russell, are far less likely to be included in a traveling survey of American art than they would have been decades ago. Whenever Hollywood makes a cowboy picture, pundits swarm in to declare a revival, which then fails to happen. Cigarette ads are, of course, prohibited nearly everywhere. But there is no confusion about the appeal of Lil Nas X and Sheriff Woody Pride: both in their separate ways have emerged from the cowboy’s most enduring range, the nursery. They ensure the survival of the cowboy in places where citizens—who may live in condominiums and work in offices—do not equip themselves with hat, boots, and gun to run routine errands.

Richard Prince, Untitled (original), 2006, original illustration and paperback book, 37 × 25 inches (94 × 63.5 cm)

Interior spread from Richard Prince: Cowboy, 2020. Published by Fulton Ryder and DelMonico Books | Prestel. Artwork: © Richard Prince. Editor: Robert M. Rubin

Recently Prince has rephotographed the tearsheets as tearsheets, mirrored rips along the page gutter included, but with the language digitally excised. These works represent a change in that they restore the full expanse of the originals and emphasize their source in disposable printed matter. They remind us that we are looking at highly artificial representations of a thankless agrarian task, now almost entirely obsolete, that consisted of shifting herds of animals from one place to another many miles removed, along trails replete with hazards of all kinds, in near isolation and precluding much verbal communication, in harsh weather of all sorts, for negligible pay that was frequently converted into a single weekend’s toxic pleasure at the end of the drive. And that for complicated and intertwining reasons this job became an exemplar, a dream, an aspiration, a legend, a national identity, a sales pitch, an alibi for antisocial behavior, an excuse for violence, a basis for inhumane politics, and a model for alienation. And that even in full knowledge of all that, the appeal of the cowboy still remains, primal and sexual and powerful, as if exposure to his image had first occurred in the womb.

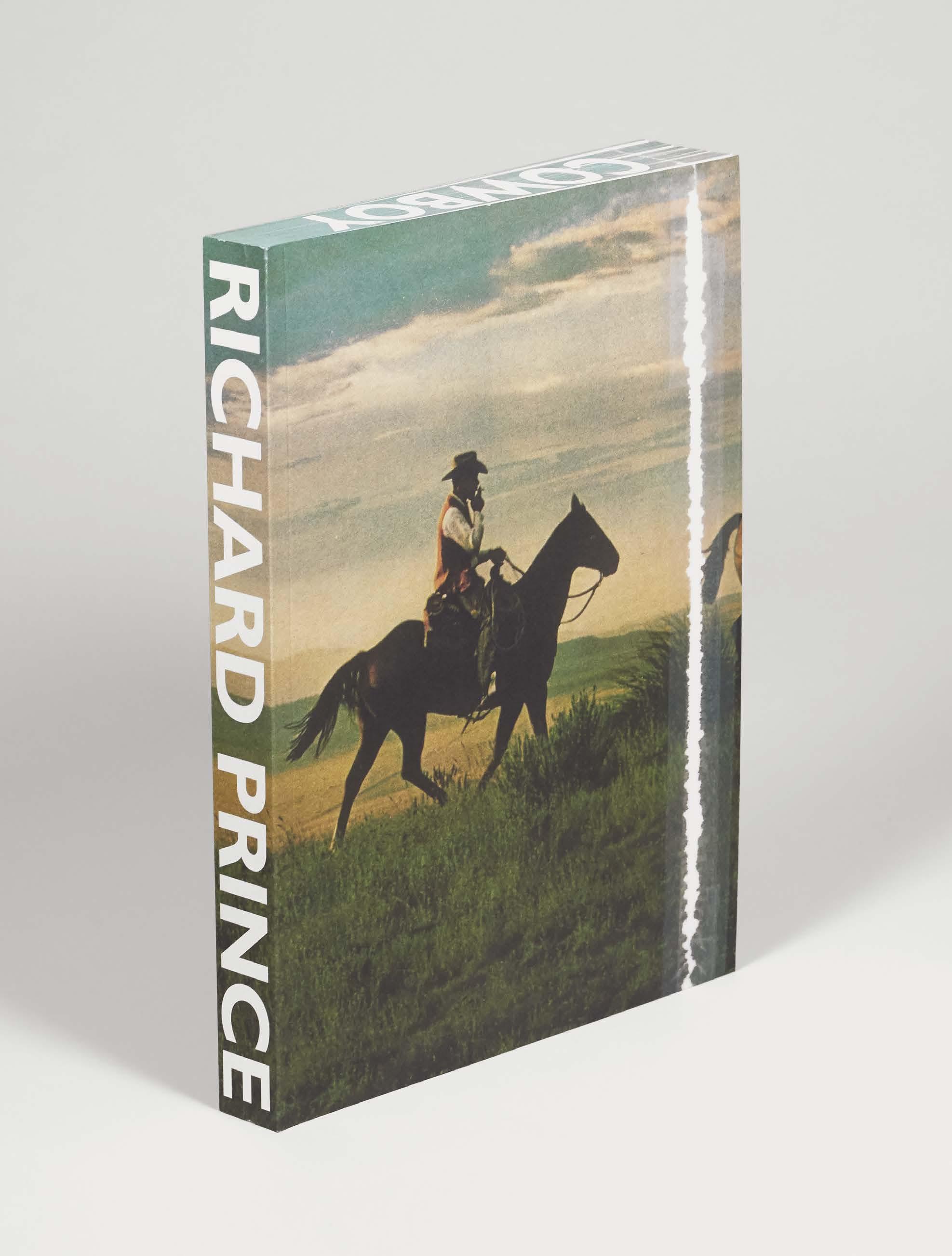

Richard Prince: Cowboy, a monograph on the artist’s series, was released in the spring of 2020. Published by Fulton Ryder and DelMonico Books | Prestel. Edited and introduced by Robert M. Rubin. Rubin is also the author of Richard Prince: American Prayer (2011), copublished by Gagosian and the Bibliothèque nationale de France on the occasion of the exhibition of the same name.