13 minute read

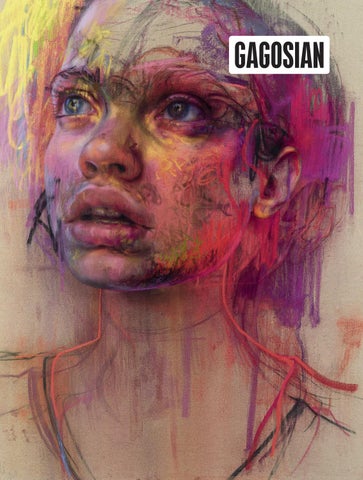

JENNY SAVILLE: PAINTING THE SELF

Jenny Saville speaks with Nicholas Cullinan, the director of the National Portrait Gallery, London, about her latest self-portrait, her studio practice, and the historical painters to whom she continually returns.

NICHOLAS CULLINAN I wanted to begin by asking you about the new self-portrait that you’ve been working on. Could you talk about that work and the process of making it?

JENNY SAVILLE It’s in the tradition of works of mine like Ruben’s Flap and Fulcrum [both 1999], where there are these different sections. The whole painting is made from a series of selfie photographs. It’s a play between the photographic and painterliness.

NC You’ve mentioned to me in the past how you like to be surrounded by your older works, and in a similar way, you have these walls of incredible image sources that have inspired you around your studio: everything from old master paintings through to graffiti to abstract art like Cy Twombly’s. How do these references serve your work?

JS As a painter, you’re constantly scanning for visual potentials you can use; I’ll stop my bike, photograph some graffiti or a blossom tree with blue sky behind or bright crimson leaves in autumn. Nature produces the most incredible light and depth. It has everything an artist needs, and it’s a cliché but it still shocks me with wonder. Since lockdown I’ve been photographing flowers. You know, I don’t paint flowers. I don’t paint burning buildings. I don’t paint landscapes. But I collect all these things in photographic form and they find their way into the work. I’m forever photographing the floor of my studio. It’s got hundreds of accidental paintings, each with an incredible gravity. I see gravity as an extra arm I can use.

NC It’s like Jackson Pollock’s studio, the barn on Long Island.

JS Exactly. Painting on the floor is good because it takes away your conventional skill and ability to see. The material itself is playing with gravity and I make marks and merge paint with a certain energy. It’s like a way to trap nature; to hold onto a sense of time. When you crash or slide colors together they are forever frozen in that moment. I find that visually thrilling. Then when you build form off that moment—like a nose, for example—it creates a visual shock. It’s a game of contradictions, of building and destroying, or of being conscious and letting go as a way to access greater reality. Sometimes building the nose destroys the paint and you lose the magic, and you have to reactivate the paint and go against the form again.

NC What’s interesting about what’s on the walls in your studio is, the selection collapses any distinction between contemporary, historic, figurative, abstract, high, low.

JS I’ve made a whole series of works based on a small ceramic bowl that my daughter made in one of those ceramic shops where kids paint teapots and things. She painted it in this sort of azure blue with brown and red spots. It held this light that was so beautiful, it felt like the sea and had movement in it, so I took the bowl to the studio and I’ve mixed a whole range of colors based on that bowl, it became the backbone for a whole group of works. I don’t value that any less than looking at a great Titian or a Velázquez portrait.

NC Color is becoming much more high-keyed in your recent work.

JS I think one of the reasons why colors come into my paintings so much is because I use pastels and oil bars as intermediaries between drawing and painting. Pastels come in the most incredible range of beautiful colors; when I work with this group of pastels, all the colors are just sitting there. With oil paint there’s a more limited range, and I mix the actual tones. If I need to distinguish the side of a cheek from the front face of a cheek, I can mix a precise tone to do that job. In pastels I can’t do that because they come in a set range, so it’s forced—at the beginning it drove me mad, I couldn’t hit that note properly. It forced my hand to come up with another way to make the tone. An artist like Degas uses slats, squiggles, and layers in different colors of pastel to create the tone he’s after. Some of these colors are electric when you identify them individually. So I started to experiment with the same technique, using stronger colors on top of each other to make the tone or to do the job of the tone itself. That’s helped my painting a lot.

NC When we were in Paris last autumn—when you could travel—we went to see the Degas show at the Musée d’Orsay, and I remember you looking really intensively at those pastels.

JS The late pastels—they just fly. I mean, Degas can be seen as this straightforward artist who painted dancers, and people see him as quite an academic artist. But if you just stand in front of those late pastels and look: that color is broken up. It’s absolutely majestic. Small sections can be like a Willem de Kooning painting. And he did that because those pastels come in incredible colors. During lockdown, this wonderful pastel shop in Paris has been sending me pastels. I bought a set that’s based on Monet’s garden. The shop is called La Maison du Pastel. It was founded by Henri Roché; I think he was the great-grandfather of the current owner, Isabelle Roché, and he made pastels for Degas. I’ve always had a romance about finding this shop, and I found it and it’s so incredible to make a head using Monet’s palette. Since then they’ve been sending more pastels. I’ve been working on raw linen and I asked if they could create a palette. So they’ve now sent me a set of pastels that are based on raw linen.

NC When you talk about someone like Degas, you think of something “pretty.” And that’s the association with pastels—the colors are kind of muted and delicate. But the way you use them, there’s a kind of toughness, almost an ugliness. I mean that in a good way, like there’s a brutality.

JS I think it’s the charged nature. I open a drawer of pastels in a shop and it’s a visual shock. The level of pigment is sensational, like staring at the light of the sun, and I started to ask myself, “How do I get this feeling into my work?”

NC In thinking about the inspiration for your current work, one of the things that’s amazing about Rembrandt’s self-portraits—and I know you chose two of them to think about, a very early one and a much later one—is his ability to depict himself at all these different stages in his life. He depicts himself as a young artist all the way through to old age with such an unflinching gaze.

JS He gave me a lot of confidence growing up. It’s a difficult thing to say, isn’t it now, to say, oh, “He paints the truth.” But Rembrandt is part of a group of artists who never go away. It’s like seeing a Francis Bacon exhibition: it just blows you away. Certain artists really hit—they don’t go in and out of fashion. I like to work in direct dialogue with a particular work, to really unlock it. I’ve found that’s

been really useful for personal growth as a painter. If I go to New York, I spend a day at the Met. The last time, I went around photographing nostrils; some artists paint great nostrils.

NC [Laughs] Go on, which ones? Can you name them? JS Yes, Velázquez wins hands down.

NC You’re thinking of the Met’s portrait of Juan de Pareja?

JS No, of María Teresa, infanta of Spain.

NC I never looked at the nostrils. I’m going to check them out now.

JS The reason is that Velázquez sees the nostril not necessarily as black. A lot of artists just do them dark, whereas he sees the light through the nostril. That’s what makes his paintings so fleshy, they have such realism because he sees the light. Rembrandt puts bright red round noses as well, or ocher. So you can see, really feel, why certain artists are so good.

NC I’ve noticed this increasingly cubistic aspect to your work—the collaging, the different viewpoints presented simultaneously—

JS I admire the way Picasso approached building form in his paintings and his attempts to harness the reality of modern life. All of his paintings, however distorted, have a structural armature to them, almost like there’s a metal bar running through every body he makes. I like that in Picasso; I like that in Michelangelo. They both have a strong central core. I automatically seek for that inner structural tension when I’m working and it’s probably why I haven’t become an abstract painter, because I like to build recognizable forms.

NC You want a reference based on reality, rooted.

JS I just automatically pull out forms. It’s an instinct I’ve got as part of my nature. I’ve found a way to work where there’s almost a fight between paint and image, and I like to work from the point of abstraction to the figure.

NC On Picasso and Cubism, there’s also his incredible, very late self-portrait from 1972, the year before he died.

JS I am mesmerized by that piece. At the moment I have that piece printed up and on the wall behind me as I’m working on my current painting [laughs]. The concentration of reality in that piece holds a lot of what Picasso was about. The heavy structural boulder mixed with the ghostly rubbing out of the colored pencils. It gives you the mystery. The way he plays with those contradictions automatically as he’s facing death. He’s terrified of death but at the same time he’s resisting it—the pure act of creation is a resistance to the end. And I appreciate that.

NC And the thing that’s extraordinary about that work on paper is that you see the skull underneath.

JS Yes, exactly.

NC It’s two things. It’s life and death together. It’s the skull and the human head.

JS I think there are late paintings of Twombly’s that operate in the same way. It’s just using that color to say, “I will keep going, I will use every force field I have in this color.” Those incredible green and yellow and red paintings, they’re almost pushing death back, aren’t they?

NC You’ve also mentioned Egon Schiele’s self-portrait. You were part of a two-person exhibition with Schiele at the Kunsthaus Zürich in 2014. What’s your relationship with his work?

JS As a teenager I was fascinated by his work. I even liked the way he looked, with his crazy hair. His work and life spoke to that teenage angst, that rite of passage when you’re unsure about yourself. But at the same time, his line was strong and confident. What a draftsman he was! One of the surest lines in art history. But then I sort of forgot about him a bit as I was learning about other artists. When the curator Oliver Wick suggested putting our work together in an exhibition, there were so many relationships that I’d forgotten: from the low-to-high viewpoint to the mother-and-child pictures. He unfortunately died from the Spanish flu, the last pandemic we had, when he was twentyeight. We hardly got to see him at all. He made this concentrated body of work that was brilliant and unusual. He was in that fertile atmosphere of Vienna with Klimt and the Vienna Secession, but there was something unique about Schiele.

NC I was recently involved with a collection of essays on Jean-Michel Basquiat’s self-portraits, which have really been overlooked. I know you have a particular interest in him and his self-portraiture. JS There’s a fluid movement in Basquiat’s work. You could argue that an awful lot of his work is self-portraiture, right? Making his use of language pictorial, from writing to drawing. I’ve been looking at him a lot recently because of the thrilling way he used oil bars—writing, drawing, crossing out. I know he loved Cy’s work and you can see that sort of physical activity with panels of flat color. I admire the life force in those pictures. He’s like Van Gogh in that he burned brightly for such a short amount of time and we’re lucky to have had him. Those pictures . . . he just let it all out. They’re like deejays working in a club, building sounds and atmosphere. He’s an example of an artist who’s so convincing and persistent in his language that he eventually moves everyone to him. He was right. When you see a great Basquiat . . . like the one with the layered-up wings called Fallen Angel [1981]. The layering of that, you feel like it’s great Greek theater, like The Furies, when the chorus is singing. I feel that catharsis looking at a great Basquiat.

NC We’ve talked about different artists and their careers, including artists who had very short careers, whether it’s Schiele or Basquiat. You mentioned turning fifty this year and that being a milestone. Looking ahead over the next few hours, days, weeks, what’s the future? What are you thinking about? What projects are you working on?

JS There are a few different projects underway. There’s an exciting project in Florence that’s happening in 2021 with the curator Sergio Risaliti. I’m showing at Casa Buonarroti, with some of the

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Self Portrait, 1984, acrylic and oilstick on paper mounted on canvas, 38 7⁄8 × 28 inches (98.7 × 71.1 cm) © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ Licensed by Artestar, New York

Michelangelo drawings they have there, and at different sites around the city. I’ve been creating drawings in relationship with the Michelangelo Pietà sculpture at Opera del Duomo, as well as paintings for other sites in Florence. It’s one of the most exciting projects of my life to be able to interact with the work of Michelangelo and the city of Florence. Recently, before the pandemic, I was going there and talking to some extraordinary men and women who are custodians of Michelangelo’s drawings, especially with Cristina Acidini, one of the greatest experts in the world of Michelangelo. I sat in a room with every book written about the artist and they brought out his drawings for me to study. It was very moving. It’s enriching to learn from these scholars about his life. I’ve been reading his letters, or maybe a shopping list, or a letter from the pope virtually begging Michelangelo to come back to Rome. The pope writes in his own hand—It’s the pope here, popes don’t live forever you know, can you come back and finish this commission! The pressure’s the same, whatever era you live in. And then I’ve got the project with you. And I’m doing a show in New York in November. I was doing a group of portraits for Hong Kong when the protest happened and the virus closed the city down. That show was called Idols. The world has changed and the work’s changed, so while the show in New York is still, broadly speaking, a group of portraits, it will be an entirely different exhibition.