18 minute read

Teaching empathy at medical school

Spending an afternoon playing a game of ‘yes, and’ and doing mirroring exercises was not how I envisioned teaching during my second year of medical school and was a stark contrast to the three weeks of placement in a district hospital I had just completed. Do you think you understand empathy? Do you cry at RSPCA adverts? Do you give up your seat on the bus for the elderly? Do you know when to nod and make sympathetic noises at the right time duringEC tutorials?Inrecentyearsmedical education has been pushed to teach empathy right from the start of medical education. Probably because it has been frequently proven that patients who feel empathy from their medical practitioners have better health outcomes and therefore it is considered a key skill of anyone wanting to work in healthcare. However, it some aspects we see a decline in empathy throughout medical school

The research

Advertisement

As a surprisingly little researched area, there have only been a few quantitative methods devised to measure empathy These studies looked at empathy score changes over a range of time periods, but what was shown to be most significant was that empathy scores of students sharply declined between the start and end of third year, where long term placements begin on the new UK integrated course. It also was made clear that medical students with higher scores on the empathy scoring system, and therefore were considered more empathetic displayed more clinical competence, leaving us with an alarming dilemma. Why does empathy decline?

There are many theories as to why empathy declines throughout medical school, despite growing efforts to devote teaching time (much coveted in a ruthlessly paced degree) to it. The term ‘battered child syndrome’, usually in reference to victims of child abuse, has been used to describe medical graduates. Some argue that medical school does not treat students well; it dehumanises both the students as well as their patients and forces them to undergo a cynical transformation as the promise of an idealistic career and future disintegrates. This loss of faith in medicine and its practice is experienced by essentially every medical student, as they begin to realise the limitations of human intervention and the extent of institutional failures, notably in the NHS. This coupled with constant discouragement and disregard from doctors and supervisors in clinical settings such as placement leave students without good role models. An increase in apathy could also be linked to the encouragement of emotional detachment from patients, in the interest of clinical neutrality and preventing physician burnout.

Can empathy be taught at medical school?

Empathetic teaching at Bristol University begins from day 1, primarily in the form of effective consulting lectures, labs and placements but also highlighted when relevant alongside other clinical teaching. In addition to this, there are a range of oneoff specialist symposia, lectures and even creative projects developed to encourage empathetic consideration. These projects are centered around understanding patient perspectives and using various forms of art to put ourselves in the shoes of others.

On paper, this sounds great. A cohort of medical students who instead of being stressed out by details of the Krebs cycle, have been sent to paint and think about their feelings. Of course, for some students, this is a useful and reflective part of studying medicine. However, some students can find it stressful and an unnecessary addition to an already heavy workload. I spoke to severalsecond-year medicalstudents which showed mixed opinions about how they were taught empathy. One student I spoke to thought that patient contact was the best way to teach empathy, stating that “GP and academy settings help us understand a patient’s background and see them as a whole person”. Many students deemed empathy-specific lectures to be ‘useless’. Two thirds of the survey responders said that the context in which empathetic teaching is delivered to them affects the extent to which they are able to engage with it, highlighting that perhaps there is an optimum time and place for teaching empathy, that perhaps is not yet being considered. As to whether or not empathy is something that can be taught, students appear not convinced. 90% of students responders claimed to understand empathy, but only 43% agreed that medical school had improved their understanding of empathy. “I’m not sure if genuine empathy can be taught.” says a second year medical student.

Should we try something different?

During my time on the theatre and empathy project, we spent three weeks discussing and analyzing various forms of artwork, including literature and theatre. We attended several talks and workshops exploring the use of theatrical teaching techniques in a medical setting, run by BLESMA, Osaka University Hospital, and theatrical professionals. We developed our own story telling techniques, and the project culminated in a short story telling performance. Many of the techniques and exercises we did in our workshops are commonly used in theatre groups as well as in social support groups, as an exercise that promotes bonding and healing

Although I was reluctant at first, the project grew on me and I feel I have come out of it with a revolutionized understanding of empathy. The other students who participated in the project alongside me found the style of teaching refreshing and effective, agreeing it should be endorsed amongst all students. Two thirds of the medical students I surveyed agreed they wereopento tryingawork-shopbasedform of teaching, even if it required a new way of thinking.

Conclusion

The exact reason as to which empathy declines remains unclear and is likely multifactorial. One thing that becomes apparent, is that much of the research surrounding medical student empathy looks just at finding whether or not it is declining, as opposed to trying to find out why. Throughout the short period of time in which I was surveying my peers, it became clear that student perspectives on empathy and teaching are essentially never considered. I was surprised by the number of students who not only came forwards, but also wanted to be kept in the loop about this piece. Whether or not empathy does in fact decline, the way students, future doctors, interact and empathise with patients is largely influenced by the education they have received and the experiences they have gathered whilst at medical school. We cannot control individual variations based on personalities, nor can we control the changing climate of the NHS and working in a medical profession, but we can control what we teach our students. Perhaps, instead of focusing on quantitatively measuring student empathy as a marker of performance and response to teaching, we should redirect our attention to trying to give students the most appropriate resources possible. What remains clear from this is that students do appear to care about empathy, but it remains a struggle to have their voices heard.

A. Andrieu 2nd Year medical student

On junior doctors’ strikes: the perspective of a first-year medical student

As I’m writing this on a quiet Sunday evening, it occurs to me that tomorrow is the deadline for the junior doctors’ strike ballots to be received by the BMA. The outcome will determine whether or not their planned 72-hour walkout will go ahead in March. In order to be successful, over 50% of eligible BMA members must vote, and of those, the majority must be in favour. Not meeting these conditions would mean the strike action is not legal under UK law. The last time I remember discussing healthcare workers’ strikes was over a year ago, when I was preparing for my medical school interviews. We explored the ethics around striking where people’s lives are at risk. All strikes affect people’s lives to an extent – after all, that’s the whole point, right? People often don’t pay attention unless it affects them personally. However, there is a distinct difference in morality between striking as a train operator and striking as a junior doctor. One will make people late for work, and the other is withdrawing their labour from a system holding precious lives in its shaking hands.

Being a first-year medical student at this time is a little disheartening. I can only imagine how those about to graduate must feel. They’ve put in years of work, preparing to enter a profession with ever-decreasing morale. Doctors are leaving the NHS at an alarming rate, either to focus more on private work, due to better pay and working environments, or to leave medicine altogether – temporarily or permanently. Among the doctors currently working in the NHS, burnout levels are sky-high and willingness to remain in the system is rapidly declining. The disparity between the sacrifices made for the job and the respective pay and conditions is more evident than ever. I spoke to a clinical fellow who explained to me why she voted in favour of junior doctors’ strikes. In addition to the fact that junior doctors were excluded from NHS pay rises during the pandemic, the current inflation rate means that many young doctors are caught between a rock and a hard place financially. Add this onto four to six years of debt from medical school, and the situation that you find yourself in is dire. On top of this, the frequent relocation makes housing situations difficult and can prompt costly commutes to work. If they can drive instead, they are often charged for onsite parking during their 12h+ shifts.

A defining feature of junior doctors’ deteriorating working conditions is the staffing crisis. It has become the new normal to be understaffed on the hospital floor. Junior doctors often find themselves being the most senior member of staff responsible for a ward, and looking after far more patients than is manageable. The standard of care that we aspire to during training cannot be reached under these conditions, and the waiting times patients complain about will only increase. Many are pushed to their limits every shift, working more hours than they are meant to due to lack of staff to handover to. This results in more burnout, anxiety around coming into work and a greater need for time off. The vicious cycle continues. It’s no wonder doctors are quitting for jobs that are both less stressful and better-paid.

A counterargument often made against doctors’ strike action is that working in medicine is a vocational profession, therefore they should not be seeking a pay rise. Given that junior doctors’ salaries have declined by 26.1% since 2008 (BMA), the term “pay restoration” is arguably more appropriate. A FY2 doctor told the BMA that remunerating all those hours and skills, without which people would’ve died, is essential. Junior doctors must be compensated for the ever-changing working hours, the constant moving around and the nights spent wide awake with overwhelm or worry. They must be shown that the years of training amount to something besides poor treatment and burnout. We need a greater incentive to keep doctors in the NHS; otherwise, we will keep losing them.

I must admit that when I began planning this article, I was undecided on whether or not I agreed with junior doctors striking, or if I’d strike myself in this situation. Even now that I’ve come down on one side, I could still argue very much for the contrary. I imagine that even those most adamantly voting to strike worry for the impact the withdrawal of their labour will have. The moral imperative of a doctor to provide care is not easily overridden. However, given the testimonies I have heard, it is with no hesitation that I say I support those striking. The government is not acknowledging how critical the work of junior doctors is, and they cannot continue to work in such straining conditions. They have asked for their needs to be met, and the government has refused. If a 72-hour walkout is what it takes to get those in power to listen, then so be it.

Let them drink tea; a Fourth Year medical student’s perspective on the strike.

When we heard the news of the three-day junior doctors’ strike occurring in March, I must admit I was slightly overjoyed to have three days off to catch up with my Anki and visit my parents. However, I was also very keen to attend the picket line and show my support for the junior doctors.

As I was on placement at St. Michael’s in Obs and Gynae, I listened to a lot of women around me discuss the importance of the strikes. As a woman I am saddened by how our pay is consistently less than that of our male counterparts. Women who want to have children will inevitably spend longer training in medicine and therefore will remain in lowerpay gradesfor considerably longer than the men around them. I remember during my intercalation year, when university strikes occurred, I listened to a very impactful senior researcher in Public Health who explained to me why she was striking for young women to receive better contracts and pay.

However, my keen interest in showing my support was very rapidly curtailed when we received an email from the university stating that whilst we were not allowed in the hospital, we were also not allowed to join the picket. The only suggested involvement we could partake in was to “bring cups of tea to show our support” which seemed a very small amount of activism considering the junior doctors’ pay would be mine in less than two years. In any other job, if you were applying to a big firm and saw that their workers on all levels were striking, I expect one would becomeslightlywary aboutworking there. However, I know that once I graduate, in a year and a half - eeek! - that I will be working for the NHS and so it seems strange to be completely excluded from any say in our future. I want to support the individuals taking this decision in a way that exceeds providing a hot drink. Medical school itself is extremely financially draining. Most of my nonmedical university friends have graduated and have started earning. This is my fifth year of university; still living partially off my parents is becoming old. As well as financial impacts, I have heard horror stories from recent graduates about conditions. One example is from an F1 working a nightshift; the hospital was so understaffed that they were unable to get to a patient suffering a heart attack resulting in the patient’s death.

It is clear that I support the strikes. I want better pay and conditions for doctors in the same way I want better pay for nurses and rail workers. However, I think it’s important to acknowledge that doctors are at the top of the medical sector, and they receive much more financial compensation for their work than most other areas. There is a small part of me that feels the 35% increase is so utterly unachievable and, in a time where child poverty is on the rise and many people cannot feed their families, it seems strange that doctors would be at the front of the queue. I don’t come from a medical or scientific background and to me doctors have always represented a very middleclass group of individuals who most likely will eventually be in the top 20% of earners in the UK. That is not to say they do not deserve the pay but if it really came down to it perhaps nurses, HCAs and care workers should be first.

M. van der Heiden 4th Year Medical Student

IUD insertion: how can a clinician make it as minimally painful as possible?

The coil, also known as intrauterine device (IUD) or intrauterine system (IUS), is arguably the best contraceptive. More effective than the pill, more convenient and longerlasting than any alternative, the coil is vastly underutilised. Indeed, figures obtained by the Guardian show only 4.4% of women using contraception in England opt for the coil, in contrast to 28% who use the pill or mini-pill exclusively. So, why is this?

For many, it comes down to the common perception that IUD insertion is excruciatingly painful. Some describe it as ‘The most pain I’ve ever experienced’; and a few unlucky patients can even vomit or faint from the pain. It appears that nulliparous women (who have not given birth) are more likely to experience pain during the procedure. Other risk factors include a history of painful periods, greater anxiety and anticipated pain, and previous experience of painful gynaecological or obstetric procedures.

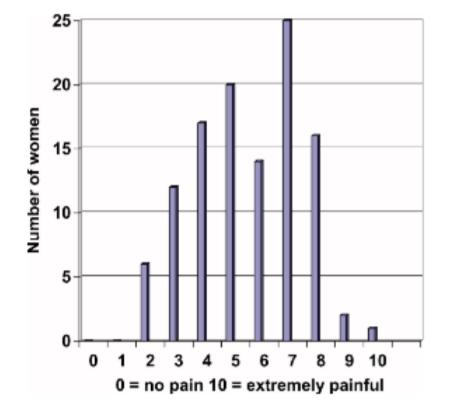

A 2005 study done in a Sexual Health Clinic in Liverpool looked at the experience of pain during IUD insertion. Out of the 113 women that took part, most described it as being similar to period pain, with around 30% describing more severe pain (see table). One woman could not endure this, and had the IUD removed 10 minutes after the procedure. The study concluded that, whilst IUDs have high long-term satisfaction rates, the widespread pain rates suggest a larger study looking at the effectiveness of local anaesthetic would be useful.

This leaves us with the question – if we were aware in 2005 that patients can experience significant levels of pain during IUD insertion, why haven’t we made greater strides in improving this?

Currently, women are not encouraged to explore their pain management options before the procedure. According to the NHS website, local anaesthetic is available on request, but it is not routinely offered. Further advice includes taking ibuprofen at least 30 minutes before the procedure, yet studies show no significant change when compared to a placebo.

Research done by the Margaret Pyke Centre (a sexual health service in London) showed that among more than 200 GPs and family planning clinics, less than a third use local injectable anaesthesia for the procedure. Many reasons were given, including that there ‘no time’ and the ‘pain doesn’t last long’. The centre then proposed that injectable local anaesthesia should be the default position for IUD fittings, favouring an ‘opt out’ system rather than the ‘opt in’ we have at present, which relies heavily on patients advocating for themselves.

Dr Roberto Leon, an OBGYN practicing in the US, proposed that pain occurs at three levels:

1. Central nervous system – due to anticipatory anxiety and fear of pain.

2. Cervical level – clamping the cervix with a tenaculum and dilating it during the passage of the IUD inserter.

3. Uterine level – mild to intense cramping once the horizontal arms of opened in the fundus.

Dr Leon then acted at all three levels to try and reduce pain and the observed difference was remarkable. To ease anxiety, he explained the procedure in detail to the patient, as well as sending them a PowerPoint they could then read at home. For his patients, this – together with ample analgesia, including prophylactic naproxen or ibuprofen, and a paracervical block – made a world of difference. Although ambitious for the UK given the time pressure on GP appointments, a detailed guide to the procedure that can be emailed or texted in advance could therefore be useful.

In an age where we have the resources and the ability to take away pain, we choose not to, furthering the constant disregard for women’s pain reflected throughout history, particularly that of non-white women. We as clinicians need to raise awareness and question spaces in medicine that are not achieving optimal pain management for women. We need to make this an open conversation with patients. In a time when information spreads incredibly quickly via social media, it is vital to avoid downplaying the pain experienced during the procedure to avoid misleading patients.

The most effective way of tackling the perceptions of the IUD insertion procedure? Tackle the pain itself and offer injectable local anaesthetic as the norm and not the exception.

Written by P. Barry 3rd Year Medical Student

How Being An Astronaut Affects Your Body

AsourlovelyEugenetaughtusinfirstyearrespiratory,humanscannotsurviveinextremeenvironments without adaptation. Much like a coastal dweller attempting to summit Everest only to experience fatigue, dizziness and nausea as a result of increasing hypoxia and hypocapnia; you can’t just make a day trip to space.

That huge, beautiful expanse above our heads is a hostile environment. Once an astronaut arrives on the ISS the first symptom of microgravity is space adaptation sickness - likened to the nausea felt on long car rides or boat trips. This is caused by the action of microgravity on our vestibular system. The vestibular apparatus, along with the cochlear and labyrinth, work to coordinate balance and spatial orientation. However, remove that constant of gravity and suddenly the vestibular system doesn’tknow what to do with itself. In most cases, these symptoms of motion sickness will last for 2-4 days before our inner ear has acclimatised.

The next symptom of living in space is a change in the fluid balance around the body. On our home planet we spend most of the day with our venous blood pooling in the legs. Any changes to this normal distribution of fluid sees issues regulating the dynamic homeostasis of our tissues and cells. For example, peripheral oedema is a sign of the heart’s insufficiency to pump blood around the systemic circulation. The fluid imbalance caused by weightlessness causes an increase in fluid retention in the face and chest, leaving you looking not dissimilar to the passengers on starship axiom in the legendary film WALL-E. If that wasn’t enough, the fluid that is now floating around our bodies has now found its way up to the head. Increased pressure on the eyes causes swelling of the optic nerve and visual problems, with some astronauts reporting blurry vision. All these issues pertaining to regulation of fluid balance can leave astronauts dehydrated and increasingly susceptible to kidney stones.

The action of microgravity on our cardiovascular system also means our heart doesn’t have to work as hard to pump blood around systemic circulation. This leads to reduced aerobic capacity and atrophy of the heart muscle as it learns to adapt to its new environment- so no, living in space won’t get you two hearts like the time-lords of Gallifrey. Similarly to this, the reduced need to fight against gravity causes atrophy of skeletal muscle and a loss of bone density of 1% per month. This predisposes our space venturers to osteoporosis and fractures. Our immune system also won’t be too pleased about being in microgravity either. Immune cells seem to be abnormally sensitive to microgravity and hence it has been reported that the immune system is one of the most severely affected systems during spaceflight. There will be an increased incidence of lymphoid dysplasia, reduced proliferation and activation of lymphocytes, inhibition of the phagocytic and oxidative properties of neutrophils and problems with the expression of cell surface molecules - and that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Another impact of space that simply cannot be ignored is the impact of solar radiation. Our atmosphere protects us from the harmful rays emitted by the sun through fusion reactions. But leave that atmosphere,andsuddenlyyou’velostthatprotection.Weallexperiencelowradiationdosesineveryday life- whether it’s from aeroplanes, X-rays or bananas. However, the doses astronauts receive onboard the ISS are much more significant. Galactic cosmic rays are especially difficult to shield against and increase the risk of cancers and degenerative diseases such as cataracts and heart disease. If it weren’t for all the physical effects, space can wreck your mind too. Many astronauts, despite being specially selected, struggle with the isolation and confinement that comes from orbiting 408 km above the earth. Many people suffer from loneliness- which can in turn trigger low mood- but the difficulties an astronaut faces when they have left their loved ones on another planet is unparalleled. In addition to this, the alternating light and dark cycles, noise, stress and confined environment impacts our circadian rhythms. This can disrupt your sleep cycle and leave you more prone to fatigue.

Despite the above, the effects of space on the body aren’t all bad. For all the oompa-loompas out there, a stint in space might actually be something you’re considering for its height increasing properties. Astronaut Scott Kelley returned from almost a year in space in 2016 to find he was 2 inches taller than when he left. A constant battle against gravity just to stand up means that over our lifetimes we will shrink as the intervertebraldiscs retain less water and become more compressed. Living in microgravity had reduced the compression on Kelley’s spine and allowed his height to increase.

If the human race wishes to expand its horizons, to explore and colonise those great mysterious depths of space, it must adapt. If the people of the Himalayas can adapt their cardiovascular and respiratory systems to allow them to live where the air is much thinner then is it so unreasonable that we could adapt to space? Yet despite these adaptations, due to the modernisation of our species, human evolution has grinded to a halt. With the technology we have, the only way to survive the harsh environment of space for extended periods of time is to accelerate human evolution.

With current gene editing technologies, there are possibilities to combat the ill effects of solar radiation on the human body. Melanized radiotrophic fungal species- such as cryptococcus neoformans- have beenfound to utilise harmful radiation in aprocess ofradiosynthesis, which actually accelerates growth. In other words they can convert radiation into chemical energy. While this sounds sci-fi, we do have technology such as CRISPR-Cas9 with the potential to edit human DNA- adding in that property of the radiotrophic fungito protectus againstthe possible complications of long term radiation exposure. That being said, we are unlikely to see space-mutant-humans in our lifetime, but it’s nice to know the possibility is there.

Our planet is huge, yet tiny in comparison to the hugeness of space. As humans we are always curious to explore more, so must be adapted to do so. In the words of the 10th doctor, from the day we arrive on the planet, and, blinking, step into the sun -there’s more to see than can ever be seen, more to do than can ever be done… wait no that’s the lion king.

C.Wood