SARAH GRILO

The New York Years, 1962-70

Sarah Grilo

The New York Years, 1962-70

The New York Years, 1962-70

The New York Years, 1962-70

Sarah Grilo, The New York Years 1962-70, is the first substantive presentation of Grilo’s paintings in New York in over fifty years. Curated by the art historian, Karen Grimson, the exhibition highlights a critical moment of transition in Grilo’s oeuvre as she engaged in a new country, in a new language, both visual and aural. Grilo’s move to New York in 1962 coincided with a period of intense social upheaval in the United States: the battle for Civil Rights, the war waged in Vietnam, student unrest and the rise of second-wave feminism. This disruption filtered through all aspects of culture; in Grilo’s case, the tension between disruption and necessity for assimilation transformed into a new creative energy.

Galerie Lelong has long championed the work of female artists, who are often under-represented in canonical exhibitions and collections. Since the mid-1990s, the gallery has worked with a significant group of artists from Latin America, many of them women; the Estate of Sarah Grilo is a necessary and welcome addition to this mission. In Linda Nochlin’s 1971 essay “Why have there been no great women artists,” Nochlin demonstrated that the premise on which we celebrate genius is intellectually weak, as it does not consider the social or political constructs of the time. Grilo’s work and career is a clear example of how the parameters of the 60’s and 70’s for women artists contributed to her marginalization. We hope that this exhibition will begin to redress her absence and introduce a wider audience to her achievements and vision.

Our first and greatest appreciation is to the family of Sarah Grilo, in particular Mateo, Belén, and Teresa Fernández-Muro. They have deep knowledge of Grilo’s work and shared it generously with us. It is through them that I was privileged to read Karen Grimson’s thesis, Sarah Grilo: Language, Translation, and the Experi-

ence of Difference 1962-70, that formed the initial idea for the exhibition. Her rigorous scholarship and patience in tutorials enriched all of us who have collaborated on the exhibition. Organizing a comprehensive exhibition of this scope with an abbreviated time frame required the unstinting encouragement of the entire gallery: the leadership at Galerie Lelong Paris, Jean Frémon and Patrice Cotensin, supported the idea of the exhibition and were first in seeing Grilo’s importance to the gallery’s history. In New York, Bianca Cabrera, organized shipping, conservation and framing with lightning speed. Katherine Chan was key to all aspects of the show’s organization and structure; support for archives, press and catalogue design has been graciously provided by Eve O’Brien and Rita Edwards. Jon Cancro and Paul Loughney expertly installed the exhibition. Ariel Asiks, Natacha del Valle and Christine Calvo at ISLAA assisted with archives. I am also grateful to the lenders who parted with works dear to them: Mr. George Loening, Emma Loy who facilitated the loan and Gustavo and Silvina Teller who have shared their works and their deep commitment to seeing Grilo and other Argentine artists on the world stage. We are especially honored to have a work from the collection of Estrellita B. Brodsky, not only a respected scholar for artists from Latin America, but one of the great visionaries and supporters in the field.

Lastly, I thank Sarah Grilo for her singular and tenacious vision of beauty, language and difference.

Mary Sabbatino Vice President and Partner Galerie Lelong & Co., New YorkIn the vast landscape of innumerable women artists whose careers have been neglected by myopic art historical narratives, the figure of Sarah Grilo stands out as a remarkable case. Born in Bahía Blanca, in the southwestern region of Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1917, she passed away in Madrid, Spain in 2007, at age 90.1 Between 1962 and 1970, Grilo was an immigrant woman artist living in New York City as a Spanish-speaker, a wife, and a mother of two. Over the course of her seven-decade long career, she lived in Argentina, France, United States and Spain, and produced over 1200 works that span the transition from late-modern to contemporary abstraction. An extraordinary figure in the history of Latin American painting, her trajectory is yet to receive significant curatorial and scholarly attention (as indicated by the lack of bibliography and museum exhibitions devoted exclusively to her work)2, and has hence fallen into relative obscurity beyond its regional insertion. This omission is not nearly compensated by the recent inclusion of her work in group exhibition that rightly attempt to inscribe her practice within the history of post-war abstraction.3 This exhibition provides the first in depth examination of Grilo’s practice from the 1960s a pivotal moment when she first embraced the linguistic approach that characterized her painting practice over the next four decades by situating her experience of cultural, linguistic and gender difference. Grilo’s lack of fluency in English at the time makes the case of her pro-

1 Throughout her life, Grilo preferred her biographical entries to indicate 1919 or 1920 as her birth year.

2 Only Museo Español de Arte Contemporáneo in Madrid, today the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, organized a monographic presentation of Grilo’s mature body of work in a museum setting, in 1985.

3 I am referring to the exhibitions ‘Action, Gesture, Paint – Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-1970’ (2023) at Whitechapel Gallery, London, ‘Escribir todos sus nombres - Spain’s female avant-garde from 1960 to today’ at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Helga de Alvear, Cáceres, ‘Crear Mundos’ (2020) at Fundación Proa, Buenos Aires; ‘Art_Latin_America: Against the survey’ (2019) at Davis Museum at Wellesley College, Massachussets, ‘Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction’ (2018) at MoMA, New York, ‘Imán: Nueva York’ (2010) at Fundación Proa; and ‘Past Present Future: Notions of Time in Twentieth-Century Art’ (2001) at the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin.

pulsion towards textual collage even more intriguing. During the New York years, the embrace of a foreign language in painting disguised Grilo’s linguistic alterity, not as an act of deceit, but as a form of adaptation to her contemporary milieu. Her deployment of oil transfer techniques through which to appropriate English phonemes implied a process of translation that was both formal (from print to paint) and linguistic (a bilingual exercise). The unexplored sources of Grilo’s transfers, identified now in magazine advertisements and contemporary events, provide new visual evidence on the historical contingency of her creative process, and suggest that the artist’s engagement with politics and gender discourse was fundamental in her contribution to post-war American abstract painting.4

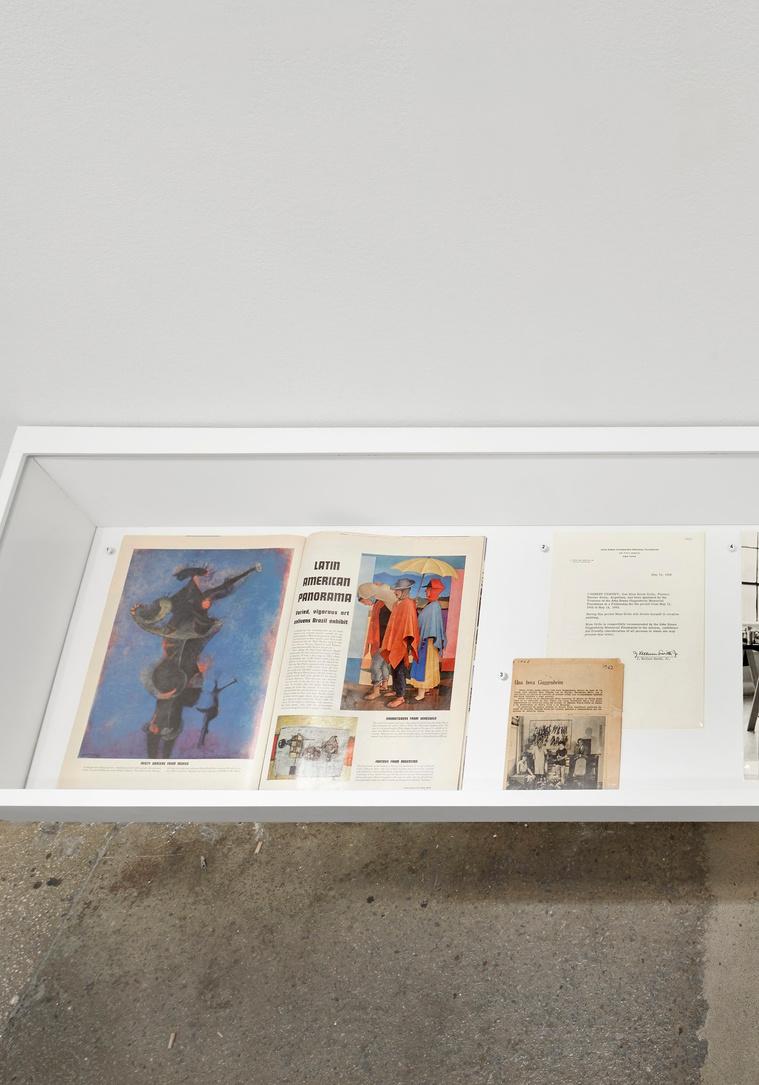

A number of exhibition catalogues from the late 1950s introduce Sarah Grilo as a self-taught artist.5 While she certainly never pursued any formal academic training, she did take lessons from the Catalan-Uruguayan painter Vicente Puig, whose Buenos Aires workshop she attended in the 1940s. It was there that she met her future husband and life-long partner, the artist José Antonio Fernández-Muro, and where she first became acquainted with other modernist Argentinean painters. Throughout the 1950s, Grilo was an active and esteemed participant in the art circles of her native Buenos Aires, and enjoyed considerable international exposure. She exhibited frequently in the city’s prominent galleries, participated in the Biennials of Venice (1956) and São Paulo (1953), and was featured in a review of the latter published in Life magazine.6 In 1952, she was invited by the critic Aldo Pellegrini to join the newly formed ‘Grupo de Artistas Modernos de la Argentina’, a coalition of the most fervent proponents of concrete art with other independent abstract artists whose intuitive approach to painting made them less inclined to the rigorous mathematical constructions of the former. Although short lived, the Group played a key role in the internationalization of Argentinean abstraction through exhibitions at Rio de Janeiro’s Museu de Arte Moderna and Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, both in 1953.7 In a series of press photographs taken of the group in 1955, Grilo appears as the only woman surrounded by a cohort of men that includes her husband, Fernández-Muro, gazing observantly at her (fig. 1). The image raises questions about the unique space occupied by women artists within avant-garde groups of

5 See Sarah Grilo and Fernández-Muro of Argentina (Washington D.C., Pan American Union, 1957), n.p; and Gran Certamen Nacional de Pintura (Mar del Plata: Dirección General de Cultura, 1958), n.p.

6 ‘Latin American Panorama,’ Life, May 31, 1954, p. 78.

7 For an in-depth study of GAMA’s role in visibilizing the country’s burgeoning abstract artists in the international arts scene, see María Amalia García, ‘Informalism between Surrealism and Concrete Art’ in New Geographies of Abstract Art in Postwar Latin America, ed. Mariola V. Álvarez and Ana M. Franco (New York: Routledge, 2019), 11–24.

the mid-Twentieth Century. In this sense, Grilo’s marriage to a male group-member appears to have functioned as a naturalizing condition, and as an implicit requirement for her membership.8 Although Grilo was one of two women originally included in the Group, the absence of Lidy Prati from this group photograph, which was taken after her divorce from Tomás Maldonado was deemed legal in 1954, suggests that the participation of women artists was conditioned by their spouses. Moreover, on the catalogue cover from the group’s inaugural exhibition, both women are identified by their first and last name, while the men appear listed by their last name alone, confirming a demotion of their status as women artists, which prevented them from being instantly recognized by their last name alone.9

Between 1954 and 1956, Grilo was the sole woman artist involved with the design collective ‘BD: Buen Diseño para la Industria’ alongside Fernández-Muro, Miguel Ocampo, and Alfredo Hlito.10 Together, they envisioned abstract fabric patterns for upholstery, sheets, dresses, and shirts that only partially reached the production stage. In 1960, she participated in the exhibition ‘Cinco pintores’ at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires, where she once again stood out as the only woman in an otherwise male troop that included Fernández-Muro, Ocampo, Clorindo Testa, and Kazuya Sakai. The exhibition likely had an impact on Thomas Messer, then Director of Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art, who included works by these five artists as representative of Argentina’s most prominent tendencies in the regional survey ‘Latin America: New Departures’, in 1961. A crucial promoter of Grilo’s work, Messer encouraged her to apply for

8 Ayelén Pagnanelli, Abstracciones disidentes: género y sexualidad en el arte (Buenos Aires, 1937-1963) (Doctoral dissertation, IDEAS, UNSAM, Buenos Aires, 2023), ps. 139-140.

9 In keeping their maiden names, both Grilo and Prati refused to adopt their husbands’ last names, indicating a resistance to phallocentric models, as well as an awareness about their differential artistic identities. See María Amalia García, ‘Lidy Prati and Her Occasion of Difference in the Unity of Concrete Art’ in Yente-Prati. (Buenos Aires: MALBA, 2009), p. 190.

10 For more on BD, see Cesarco, Alejandro, ed. Buen Diseño para la Industria. (New York: ISLAA, 2023).

a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.11 With his blessing, Grilo submitted her application the following year, and was confirmed as a recipient of the grant that would bring her to New York for the remainder of the decade.12

In May 1962, after a sixteen-day voyage on the Atlantic, the Fernández-Muro family arrived in New York and first settled in an apartment on East 52nd street. Grilo’s Guggenheim fellowship—a $400-dollar monthly stipend13— covered the costs of her living expenses in New York for a year, and had prompted the entire family’s move to the United States. This economic influx defined an exceptional circumstance wherein a woman artist’s steady income set the living conditions for the rest of the family. Grilo’s income must have positively disturbed her role vis-à-vis her husband, and set an anomaly in the traditional patriarchal model that often posed an impossibility for women to pursue artistic careers.14 In Grilo’s case, the wider context of a booming interest in exhibiting and collecting art from Latin America, which characterized the United States’ arts scene between 1959 and 1966,15 likely played in her favor. Notably, her work was included in the catalogues of the museum surveys that book-ended this propitious interval: the Art Institute of Chicago’s 1959 exhibition ‘The United States collects Pan American Art’, and the Guggenheim Museum’s 1966 exhibition ‘The Emergent Decade’. More than a mere coincidence, this contingency reveals the timeliness of her relocation for the advancement of her career.

11 Verónica Fernández -Muro, ‘Biography of José Antonio Fernández-Muro and Sarah Grilo.’ Unpublished manuscript, p. 11.

12 Following this first fellowship, Grilo petitioned for an extension and received a second Guggenheim Fellowship in 1963.

13 Verónica Fernández -Muro, ‘Biography…’ p. 11.

14 Germaine Greer, ‘Family’ in The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1979), ps. 12-35.

15 Delia Solomons, ‘Hot Styles and Cold War: Collecting Practices at MoMA and Other Museums in the Sixties’ in Edward Sullivan, ed. The Americas Revealed. Collecting Colonial and Modern Latin American Art in the United States (New York and Pennsylvania: The Frick Collection; The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018), p. 44.

Grilo and her family eventually moved into a larger penthouse on East 50th Street, which became a shared studio space for the couple and home to the entire family. The vast windows in this duplex apartment provided ample natural light, and were captured in dazzling photographs by Lisl Steiner, Henry Grossman, and Hans Namuth that portray Grilo as a mature painter, tenaciously modelling the instruments of her practice. In fact, Grilo’s arrival in New York was in no way her introduction to the North American art scene. Five years earlier, she had a two-person show alongside Fernández-Muro at the Pan American Union in Washington, D.C., which later went on view at Roland de Aenlle Gallery in midtown Manhattan, and was reviewed by Dore Ashton for the New York Times. 16 In those shows, Grilo exhibited works representative of her experiments in lyrical abstraction, heavily invested in an exploration of the chromatic and pseudo-geometric dimensions of painting. By the time of her Guggenheim Fellowship, she was looking to update her practice through a sustained and direct confrontation with the work of other contemporary artists from Europe and North America, an opportunity that she found to be only rarely available in Buenos Aires, where, as she said, international ‘contemporary art movements [could] only be experienced through the disfigured appearance imposed by the partiality of books and magazines.’17 In April 1963, following her participation in the group exhibition ‘Women in Contemporary Art’ curated by Leslie Judd Ahlander at Duke University, Grilo had a solo exhibition at the Obelisk Gallery, in Washington, D.C. In an interview published in The Evening Star, Grilo described the impact of her New York residency in terms of ‘an increased desire to work.’18 She described finding inspiration all around her: ‘The streets, looking in the windows, visiting museums, going to the shows— even the bad shows are stimulating because you see what you

16 Dore Ashton, ‘Art: Gallery Pot-Pourri’, New York Times, April 5, 1957, p. 20.

17 Sarah Grilo, ‘Plan de estudios’, 1961, author’s translation. Archives of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, New York

18 Sarah Grilo, quoted in Amelia Young, ‘Enthusiasm Is Her New Gift’, The Evening Star, April 8, 1963.

mustn’t do.’ Her experiences in, and of, the City made her ‘paint... with such enthusiasm as I never had before’19. Asked to describe her impressions of New York, Grilo explained that ‘It has given me a feeling of confidence, and consequently a craving for painting. Here, I find all the elements for my painting. Things are constantly happening that can be incorporated as abstractions… you don’t need more than to look out the window or head out to the streets. Always with an alert gaze.’20 If her previous practice had been guided by intuitive explorations of the formal and chromatic elements of painting, by 1963 the impressions of the city sparked an entirely new approach to the medium, resulting in the permeabilization of her practice to the experiences of her time.

In November 1963, Grilo’s first solo exhibition in New York opened at the influential Paul Bianchini Gallery on the Upper East Side, showcasing fourteen of her most recent paintings. A review in the New York Times described the works in the show as ‘complexly handled abstract expressionist paintings.’21 In fact, a vast majority of those works remained visibly within the stylistic vein that dominated the North American arts scene in the first years of the decade. For instance, Bandera (a work now in the collection of the Chrysler Museum of Art in Virginia) presents a surface of varied textures, some of which were achieved through subtractive methods that the artist exerted by using tools to scratch through the wet oil, revealing layered coats of paint. 22 The appearance of paint drips running in multiple directions indicate that the canvas was re-oriented multiple times in the process of its creation. These traces of the experimental ways in which Grilo manipulated the canvas align her production with the temperament championed by Abstract Expressionist artists since the 1940s. However, at least two of the works exhibited at Bianchi-

19 Young, ‘Enthusiasm Is Her New Gift’, 1963.

20 Sarah Grilo, quoted in Luis Lastra Almeida, ‘Artistas entre rascacielos’, Américas 15, no. 2 (February 1963), p. 28.

21 Stuart Preston, ‘Art: 71 Exhibit at American Academy’, New York Times, November 23, 1963, p. 24.

22 Jennifer Myers, ‘Restoring and Revealing Hidden Treasures’ in The Chrysler Magazine (Summer 2022), ps. 20-21.

ni Gallery introduced an innovation that anticipated the radical development Grilo would undertake in subsequent years. In works such as Pardo and Enero (fig. 2), scratches on the painting’s surface appear alongside legible symbols, such as x-crosses. In the latter, a painting currently lost, a commanding inscription reads ‘SAT 5,’ possibly a calendar reference to the Saturday 5th of January, 1963. Seen alongside each other, these inscriptions take on an indexical meaning, pointing towards the locality of a site, or a self, in place and time. Right below this calendar legend, the artist inscribed a horizontal pattern of continuous X-symbols, otherwise legible as a row of interwoven V’s. This iconographic reading suggests a thought-provoking connection with the work of Alberto Greco, an artist whose close friendship with Grilo may begin to explain the kind of reciprocal influence that is evident in their bodies of work.

Known for his mythic efforts to reinstate the presence of art in everyday life, Greco was in Italy at the time, developing the foundational principles of his artistic platform, Vivo-Dito Art. A series of black and white photographs taken by Claudio Abate in Rome

around 1962 portray Greco in front of a series of graffiti he inscribed with white chalk on the city streets (fig. 3). The emblem of two entwined V’s features prominently next to Greco’s name on a brick wall behind him. In a manifesto published in Genova the year before, Greco had enunciated the principles of Vivo-Dito, a movement driven by the attempt to merge art and life, which proclaimed that ‘the artist will teach to see again what happens in the street’23 by pointing his finger at the site of artistic occurrence, in direct contact with reality. Immortalized in the portrait of his chalk graffiti, Greco’s ‘VV’ likely synthesized the consonants of his slogan, ‘Viva el Arte Vivo’ (Long Live Live Art). Reiterated as a frieze in Grilo’s Enero painting, the inscription brings to the fore questions about the urgency of identifying art in everyday life. While Greco’s graffiti take the form of a clandestine form of speech operating in and from the margins of the artistic realm, Grilo takes in the vernacular symbols, forms of urban debris, into the realm of painting. By doing so, she achieved a new and unexpected configuration of what Thomas Crow best described as ‘two aesthetic orders, the high-cultural and the subcultural, (…) forced into scandalous identity.’24 Permeable to the occurrences of the outside world,

Grilo’s work radically opened up towards the realm of the quotidian, embracing inscriptions fully charged with anecdotical connotations.

For a brief period in the early 1960s, until Greco’s untimely death in October 1965, an unquestionable synergy connected the work of these two artists, who worked increasingly with lettering and writing. While their friendship dated back to the 1950’s in Buenos Aires, between January and May of 1965, approximately, they coincided in New York. During this time, Greco allegedly performed a Vivo-Dito action on Jackie Kennedy, met with Marcel Duchamp at Pierre Matisse’s Gallery, and co-organized the Artist’s Key Club, a happening at Penn Station that raffled off artworks by Greco and thirteen other artists, including Andy Warhol, Christo, Allan Kaprow, Roy Lichtenstein, Niki de Saint-Phalle, and Dieter Rot, among others.25 Driven by his eccentric character, Greco quickly bonded with mainstream artists and dealers alike. In a significant record of oral history kept in the archives of the Museo Reina Sofía, Grilo recalls the time Greco asked her to host a house party at her apartment, which gathered some of the social luminaries of the New York art world, including Leo Castelli and Chryssa. She describes Greco’s impressive ability to organize the event and gather a crowd so diverse it resembled ‘a Tower of Babel.’26 But Greco’s outgoing behaviour masked an equal share of sorrow that would lead to his suicide later that year. During the months of Greco’s stay in New York, his close friendship with Grilo provided a crucial form of emotional support, as he described in a moving letter in which he wrote: ‘I am living through an apathetic and eerie sentimental problem, and the Argentinean community tries to help me and keep me from jumping out of the

25 See Burt Chernow and Wolfgang Volz.

and Jeanne-Claude:

26 Sarah Grilo, interview with Francisco Rivas, c. 1991. Archivo Quico Rivas. Biblioteca y Centro de Documentación. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid.

first window I may find. Especially, Sarah Grillo [sic] and Martita Bontempi (…) they are my most loyal helpers.’27 Years later, Grilo confirmed this sentiment when she spoke of Greco’s ‘exquisite sensibility’ and the responsibility she felt to keep him company and occupied during his days in New York, helping him out of episodes of depression.28 The kind of aesthetic rapport evident in their works from this period should be understood in the context of their affective affinity, which primed their practices for the embrace of similar linguistic concerns.

In May 1967, twenty-five of Grilo’s most recent works went on view at Manhattan’s Byron Gallery (fig. 4), a vast majority of

27 Alberto Greco to Lila Mora y Araujo, c. 1965. Colección Centro de Estudios Espigas – Fundación Espigas. Reproduced in Paula Pellejero and Eduardo Pellejero, eds. La aventura de lo real. Escritos de Alberto Greco (Buenos Aires: Ediciones Julián Mizrahi, 2020), p. 254. Original in Spanish, author’s translation.

28 Sarah Grilo, interview with Francisco Rivas, c. 1991. Archivo Quico Rivas. Biblioteca y Centro de Documentación. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid.

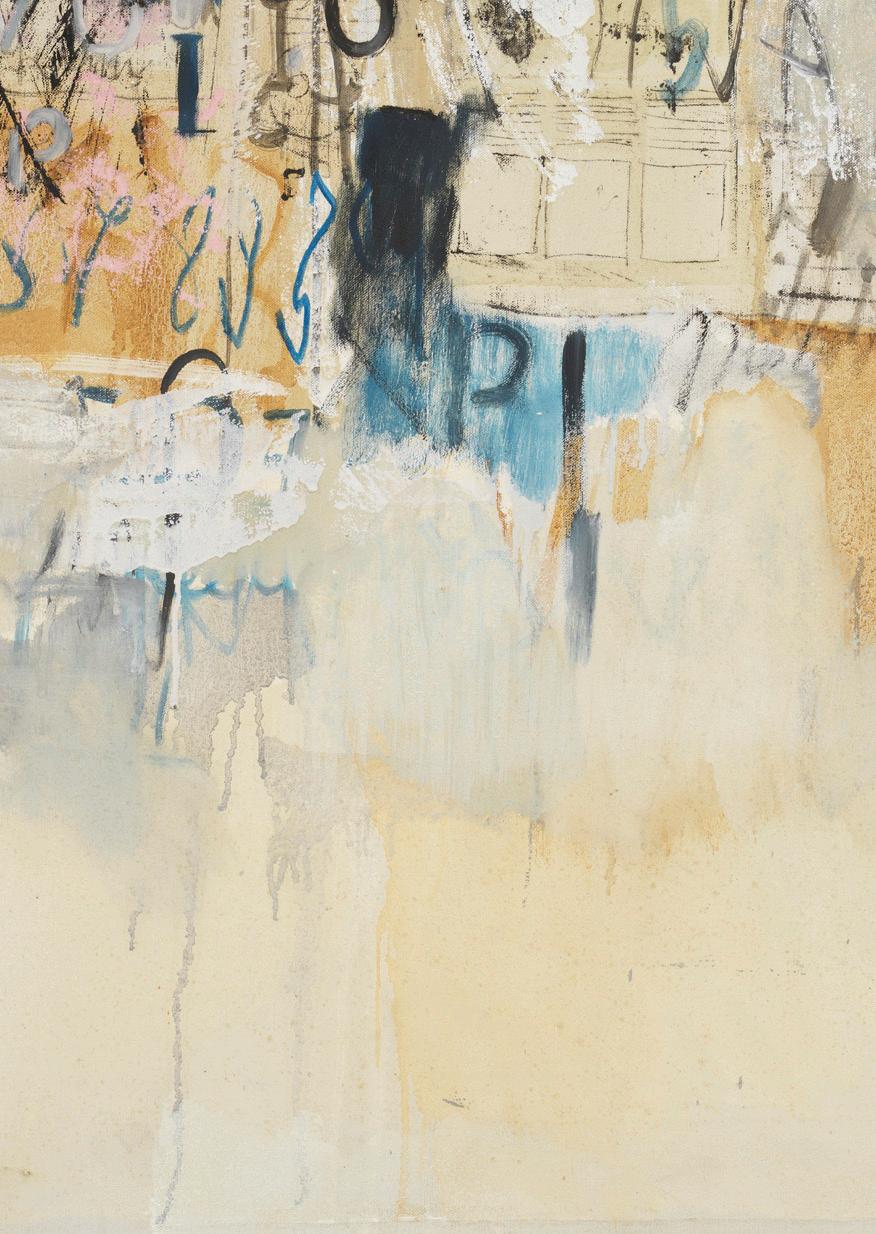

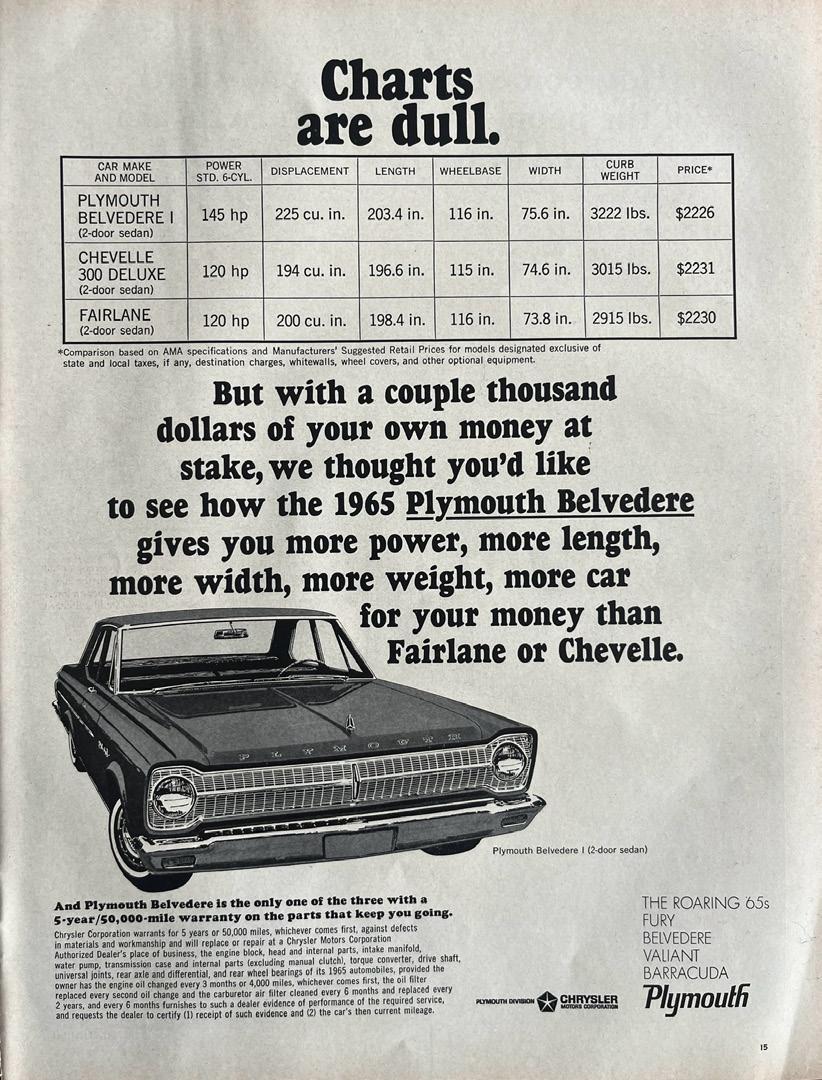

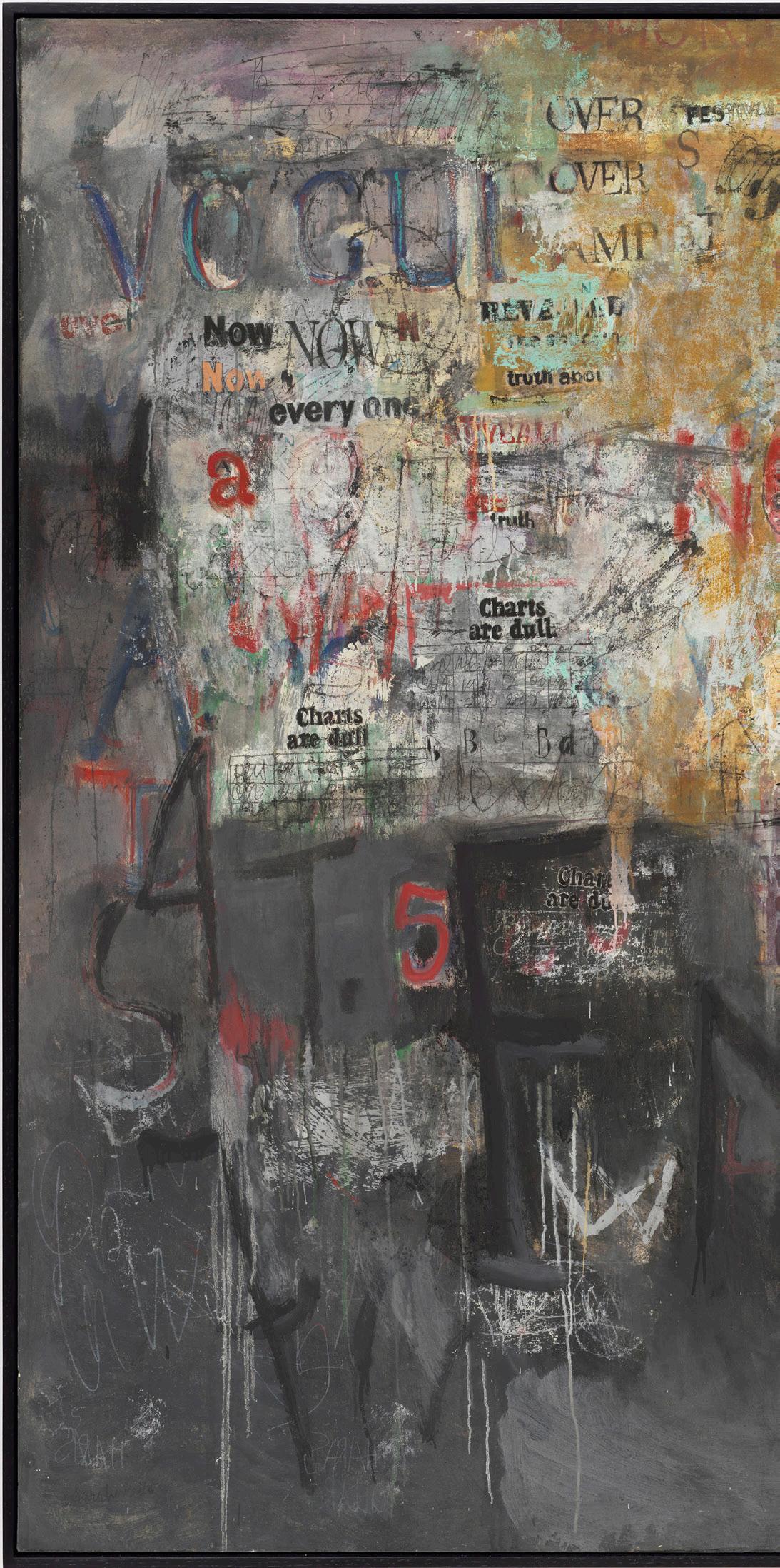

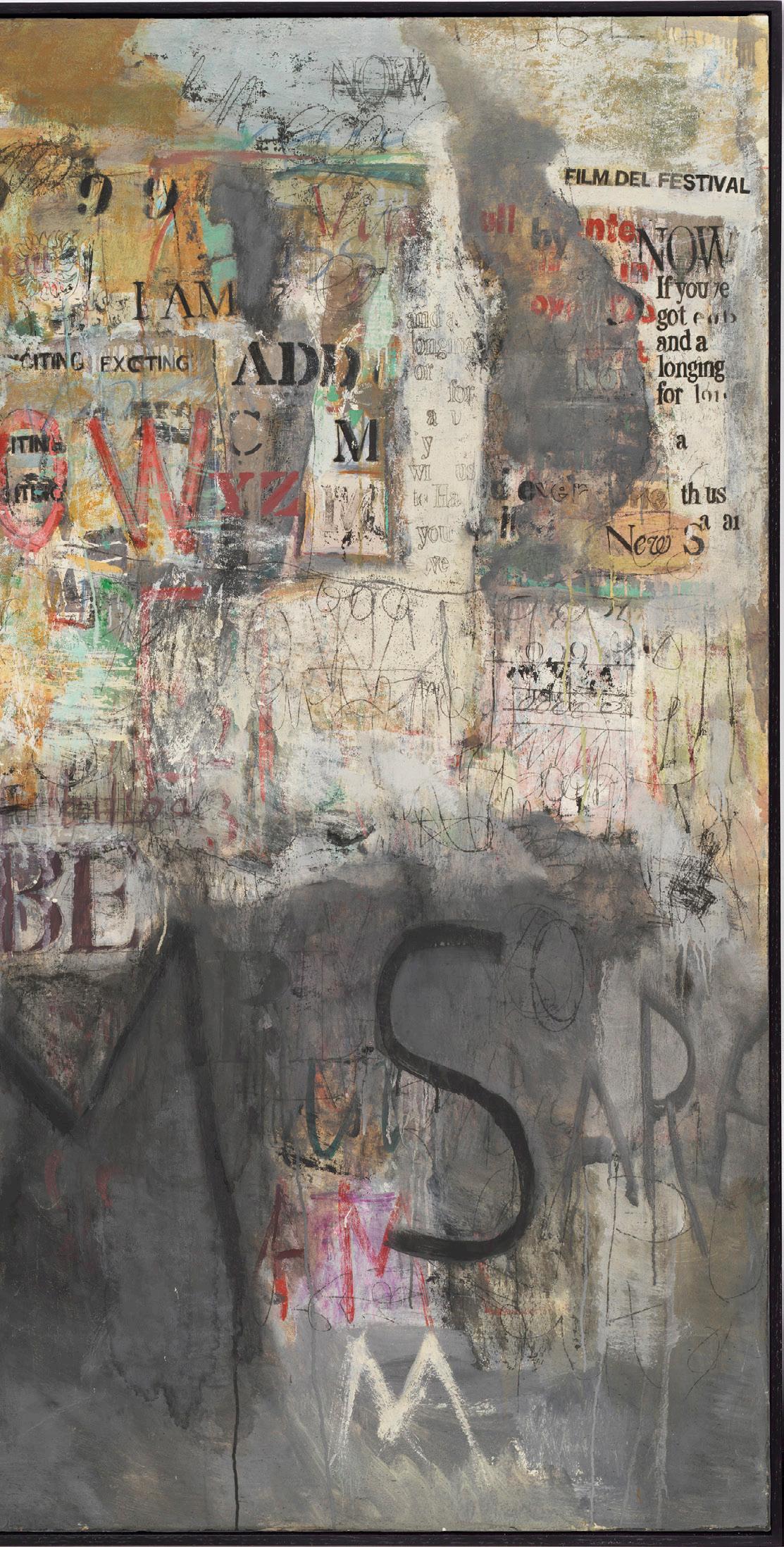

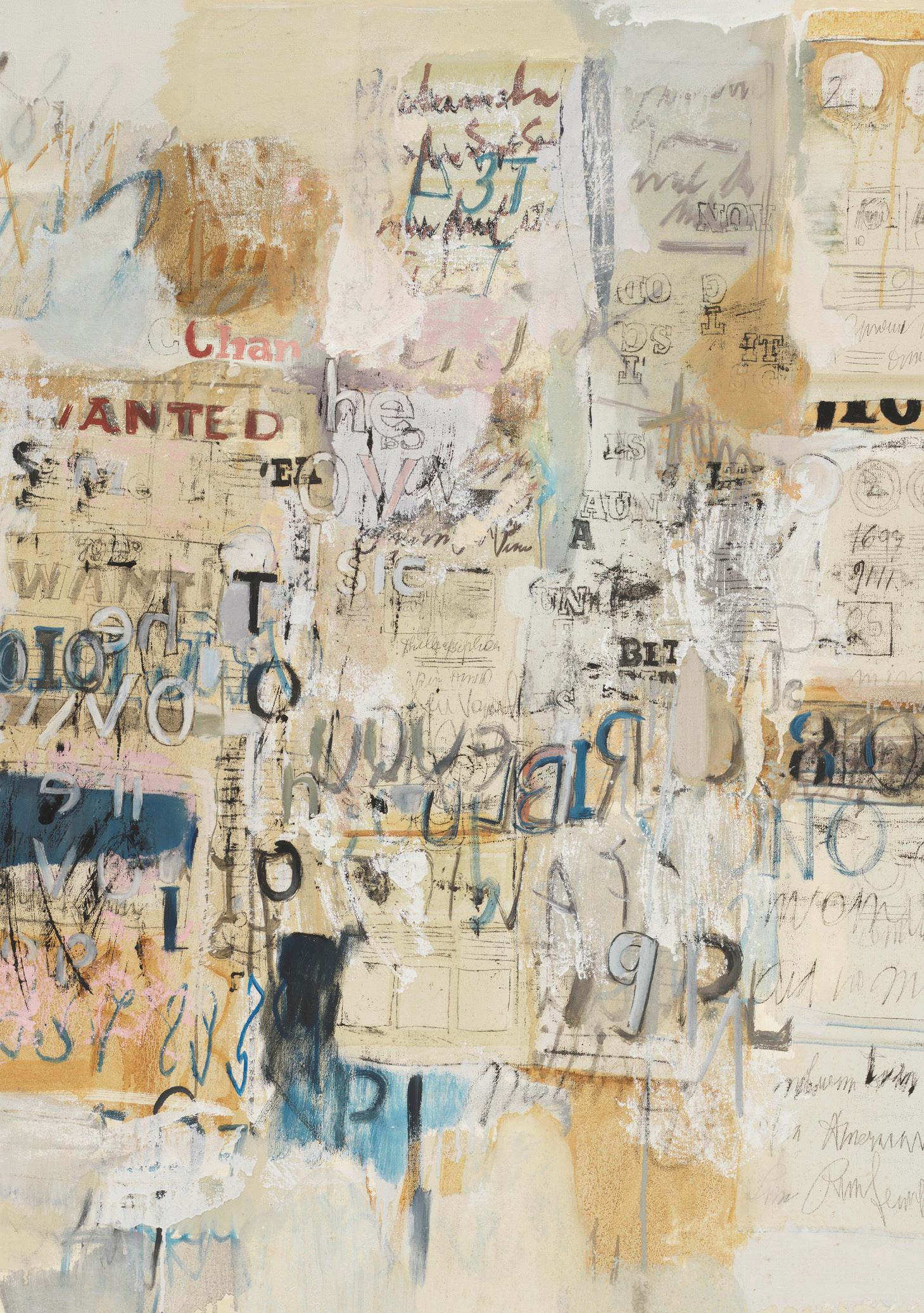

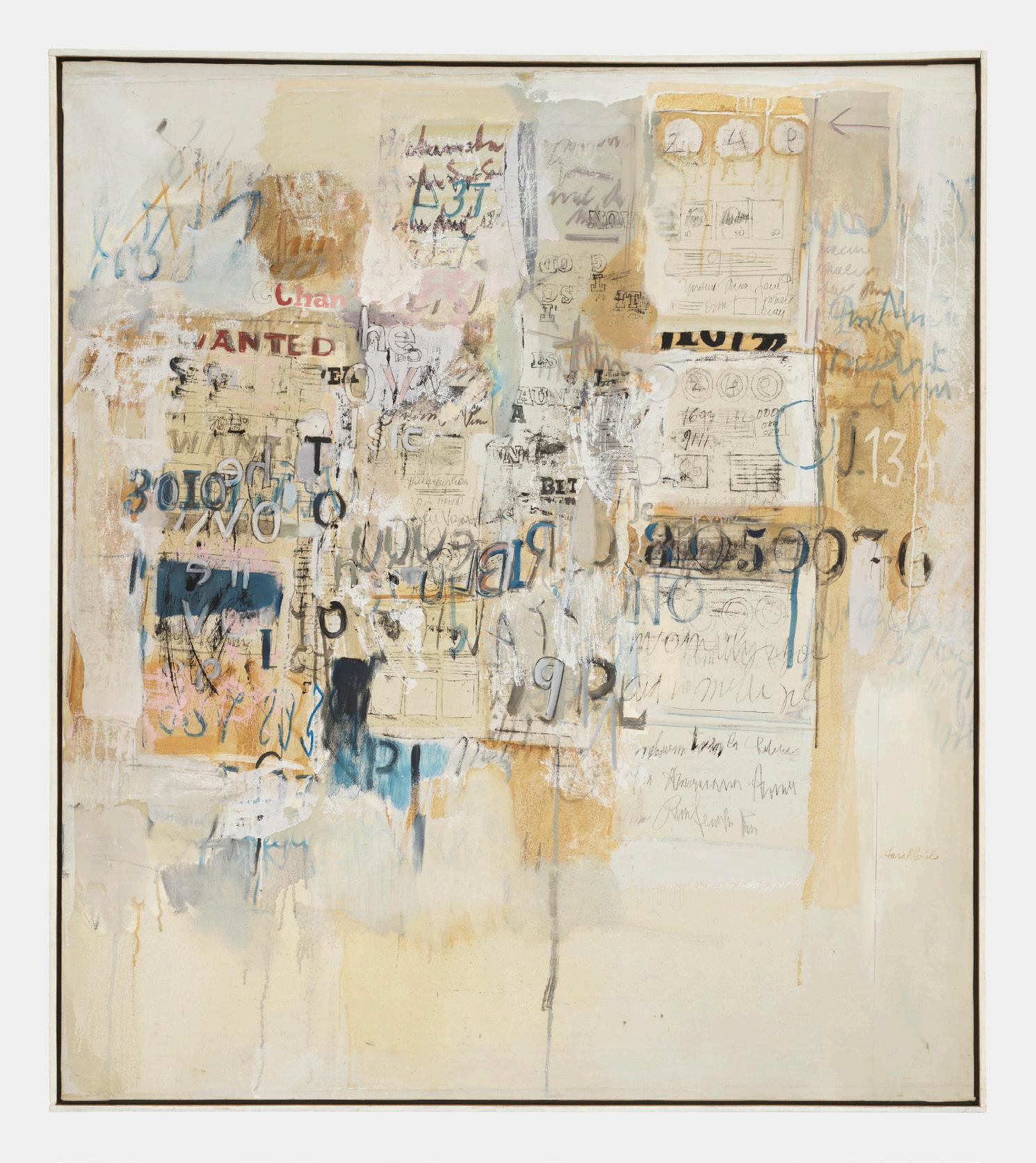

which featured legible text that resonated with contemporary events. Included in the show was her first large-scale linguistic painting, Charts are Dull, which combined easily recognizable text with other defacements of the painted surface, on a field of white, grey, ochre, and mauve paint (pp. 42-3). The work’s title, which appears thrice on the canvas in identical form, may sound like a critical commentary on the type of conceptual practices that were, at that time, incubating in the work of Hanne Darboven or Channa Horwitz; artists who used diagrams to analyse linguistic or numerical systems and visualize information. But upon closer inspection, Grilo’s choice of words is revealed to be, not an opinionated statement, but a standardized phrase taken from the world of advertisement in print media. ‘Charts are dull’ was the phrase that headlined an advertisement for a Chrysler automobile, announcing the competitiveness of its 1965 Plymouth Belvedere model. A full-page display of this advert appeared in the April 9, 1965 edition of Life magazine (fig. 5), which counted Grilo and Fernández-Muro among its loyal readers. Identified here for the first time, Grilo’s source material situates her work in the context of contemporary artistic practices that appropriated media imagery. Splintering the words from their original meaning, she disguised their reference to American commodity culture, doubling down on an act of translation: firstly, by adapting her choice of language to the foreign

English idiom; and secondly, as a form of contextual relocation (a trans-location) of the printed page. Grilo was looking at the world around her for inspiration, and soon made a habit out of sourcing printed materials from Life magazine.

The first-ever magazine to be devoted entirely to photojournalism, Life was the best-selling weekly magazine in the country by the time of Grilo’s arrival in New York.29 The Great American Magazine was published regularly between 1936 and 1972, and had translated editions printed around the world. Grilo turned towards the visually saturated pages of Life magazine and embraced words in print as objets trouvés with which to fill her canvas. Tearing out pages from the publication, she subjected these to a basic oil transfer technique, applying paint to the back of the page, then placing it on the canvas and going over the silhouettes of the print type with the aid of a pointed tool (possibly the back of her paintbrush)30, in order to transfer the shapes onto the surface of her paintings. This transfer of printed media onto the canvas suggests that Grilo was closer to strategies of Pop art than it has thus far been understood. Moreover, the specific choice of Life magazine as a source for her constructions evokes Robert Rauschenberg’s series of Illustrations for Dante’s Inferno (1958-1960) or Warhol’s Disaster Paintings (1963), in which the artists recontextualized photographic images from the same publication, and incorporated them into their work through techniques such as solvent-transfer and silkscreen, respectively. In Grilo’s case, her distinctive preference for an oil transfer technique reflects a firm grip of painting as her exclusive discipline. Thus, while her embrace of transfer and collage compositions welcomed anecdotical elements from the surrounding environment into her work, she achieved this without ever straying away from the medium of painting.

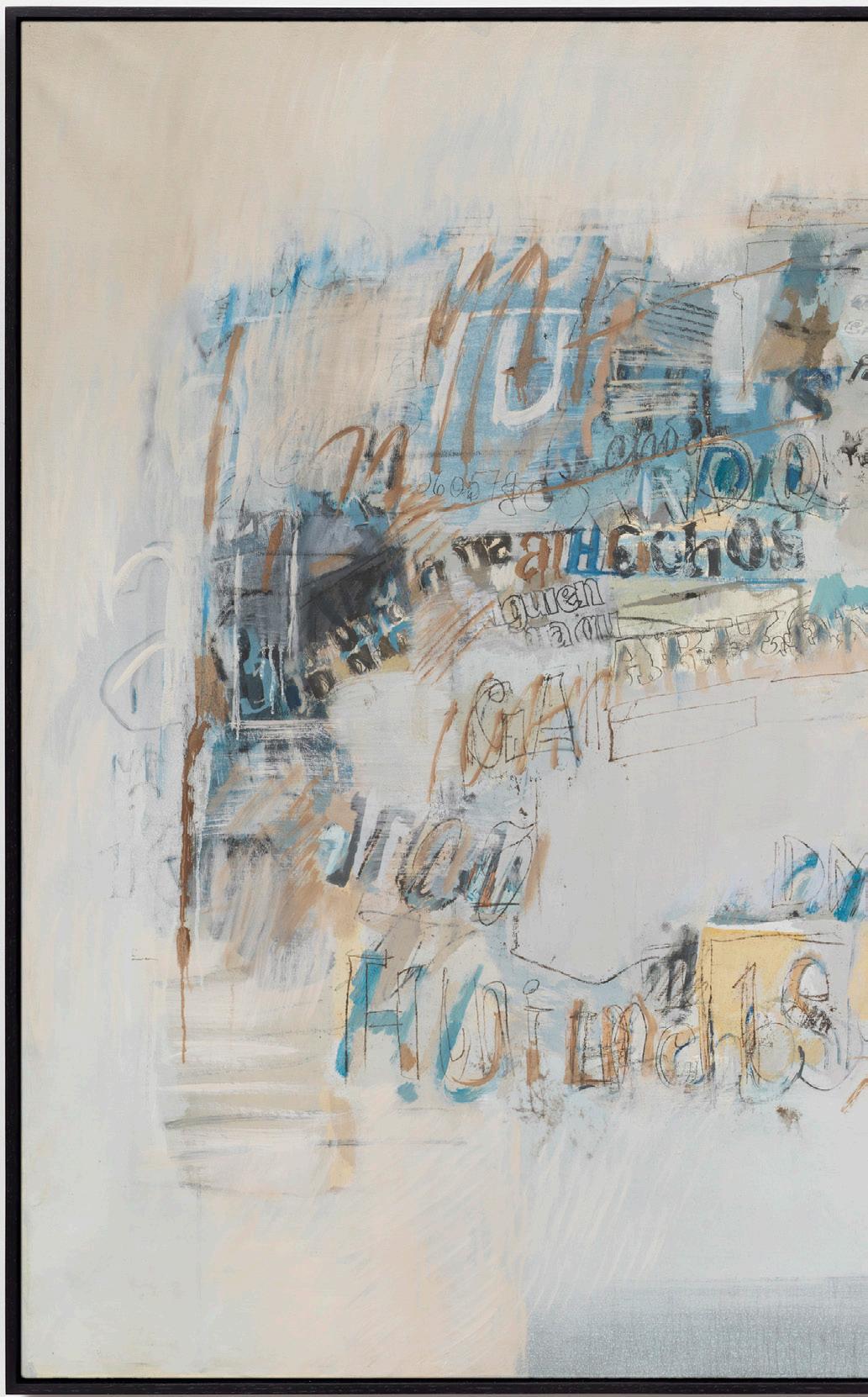

One of the most politically loaded paintings at Byron was Our Heroes (p. 48), a large canvas with a predominantly red background that gathers references drawn from contemporary events, literature, and advertisements. A detailed inspection of the painting reveals meaningful typographic transfers inscribed upside-down on the painting’s upper half. The most concise of these reads ‘Yevtushenko,’ a reference to the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, who visited the United States in November 1966. By the time Grilo had completed the painting in December of that year, Yevtushenko was coming to the end of a six-week reading tour across the country, where he had been invited by the City University of New York.31 The Soviet dissident poet, who was fascinated by the Spanish language and wrote numerous books in the idiom, had been commissioned by Life magazine to produce two literary works informed by his travels.32 Translated from the original Russian by the novelist John Updike, his new poems were published in the February 17, 1967 issue of Life, accompanied by a black and white photo-series. Yevtushenko was intent on bridging the animosity between the United States and the Soviet Union, and had recently reached global notoriety for his poem ‘Babi Yar’ 33 (1961), which denounced his country’s antisemitism and negligence towards the Jewish Holocaust. Grilo’s inclusion of Yevtushenko’s name in her pantheon of heroes is a recognition of his merits as a human rights advocate and contextualizes the painting’s crimson palette. More importantly, it stands as an undeniable expression of Grilo’s awareness of, and engagement with, contemporary politics.

To the right of Yevtushenko’s name, another typographic transfer reads ‘Was the Warren Report a Whitewash?’—a question that inserts the viewer into one of the most pressing and highly mediated debates of the decade. After President John F. Kennedy’s as-

31 Paul Hoffman, ‘Yevtushenko Arrives for 6-Week Reading Tour.’ New York Times, November 5, 1966, p. 26.

32 See ‘Yevtushenko’, Life vol. 62, no. 7, February 17, 1967, ps. 32-39.

33 Yevgeny Yevtushenko, George Ravey, tr., The Poetry of Yevgeny Yevtushenko, 1953 to 1965 (New York: October House, 1967), p. x

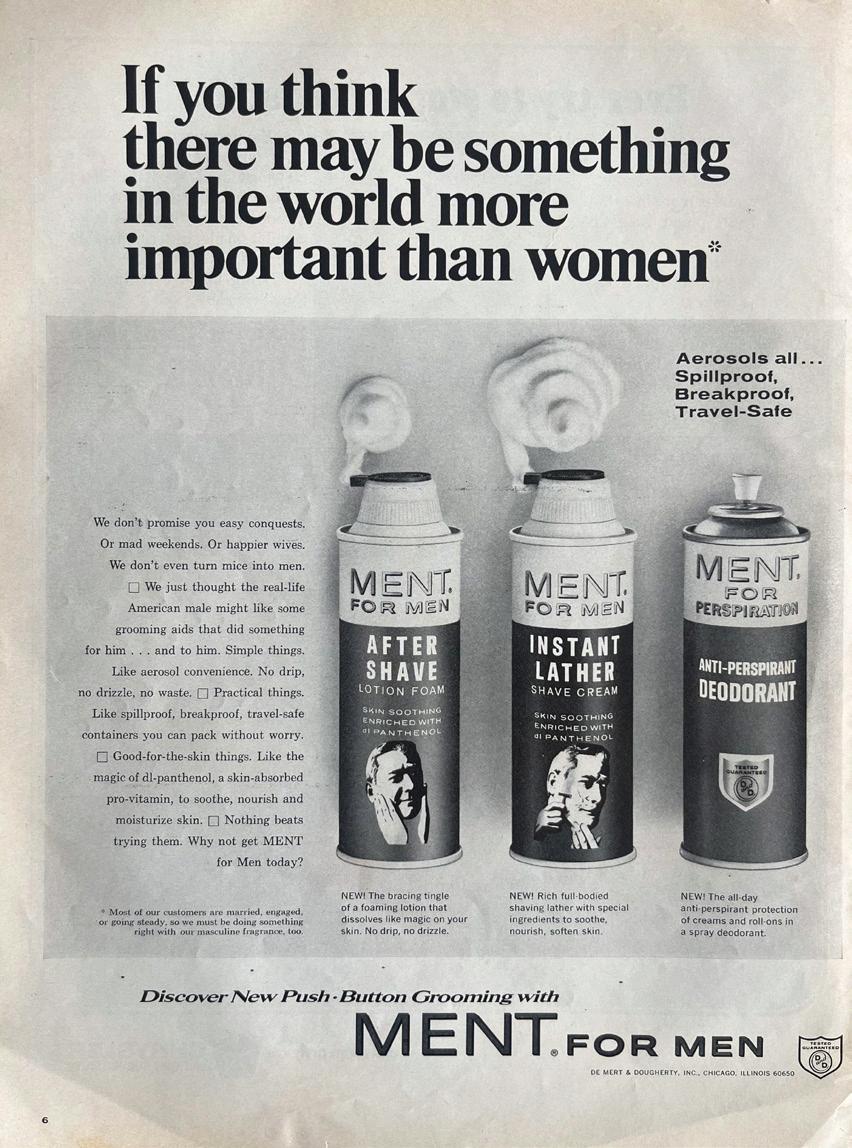

sassination was broadcasted on live television in November 1963, President Lyndon Johnson formed the Warren Commission to investigate the case. One year later, the official report concluded that Kennedy had been killed by a sole shooter, Lee Harvey Oswald, triggering public accusations of distortion and concealment of evidence by the Commission, which were summarized in Harold Weisberg’s self-published book of 1965, Whitewash: The Report on The Warren Report. Once again, Grilo choice of appropriated text underscores her interest in politics and historical revisionism. One final analysis of text included in Our Heroes provides crucial insight into Grilo’s artistic approach, and supports a new understanding that brings her work close to the discussions around gender disparity that were effervescing at the time. To the right of the canvas, another inscription reads ‘If you think there may be something in the world more important than women’—a triggering opening line taken from an advertisement for Ment, a line of fragrances and shaving cream for men that appeared in the October 21, 1966 issue of Life magazine (fig. 6). A seemingly feminist remark hijacked by the industry of male cosmetic care, Ment’s ad targeted ‘the real-life American male,’ and an asterisk at the bottom of the page states in fine print that ‘most of our customers are married’ (a guarantee of consumer satisfaction), thereby upholding heterosexual marital status as a universal value.

The representation of women in magazine advertisements has been criticized by members of the female liberation movement for the negative stereotypes it portrayed.34 Moreover, a link between the world of advertisement and women’s unease towards the standards it sustained was suggested by Betty Friedan in her introduction to the tenth anniversary edition of The Feminine Mystique, when she wrote that ‘each of us thought she was a freak ten years ago if she didn’t experience that mysterious orgastic fulfil-

6| Full-page advertisement for ‘Ment Shaving Cream’, Life magazine, October 21, 1966, p. 6.

ment the commercials promised when waxing the kitchen floor.’35 While Ment’s ad didn’t represent the interests of women, or visually reproduce any of their stereotypical images, it still managed to objectify women from a rhetorical standpoint. In fact, the wording in Ment’s commercial, while implying that women enjoy a status of insurmountable importance, attempted to force women into a graceful acceptance of their inescapable gender roles. Simultaneously targeting men as its consumer demographic, and women as an implicit subject, Ment’s ad was strategic in perpetuating the mystique of feminine fulfilment. This mechanism of positive assertion was explored by Friedan in her foundational book, where she explained how ‘the cheering words were somehow drowning

the problem in unreality.’36 Recontextualized in Grilo’s painting, the aphorism carries over an expression of the gender inequities that were being denounced by the feminist movement at the time. Painted in December 1966, only six months after the National Organization of Women was formed in Washington, D.C. by Friedan and other feminists, Our Heroes placed the ‘myth of the contented woman’37 who happily accepts her societal role, front and center. Incidentally, one of the chief tenets of the second feminist wave stated that ‘the personal is political’, meaning that what takes place in private domesticity has systemic permeability, and vice versa. Revealing the source of Grilo’s inscription in a men’s shaving cream advert allows us to interpret the artist’s gambit with linguistic transfers as an idiosyncratic strategy. Shaving, a function of cosmetic and domestic maintenance, is placed here alongside other inscriptions charged with political and humanitarian connotations, validating that the issues enshrined in private life can be homologated to experiences in the public sphere.

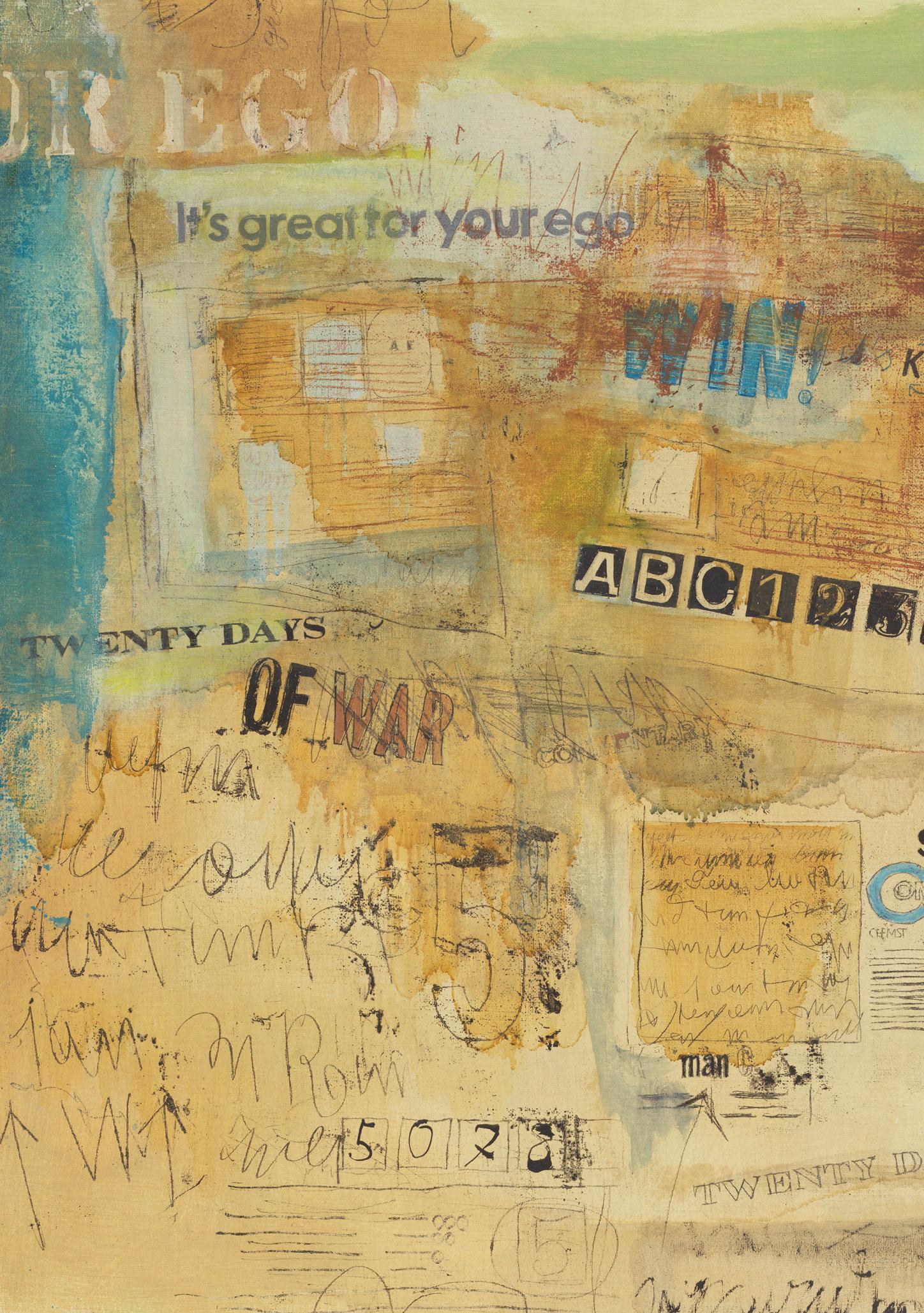

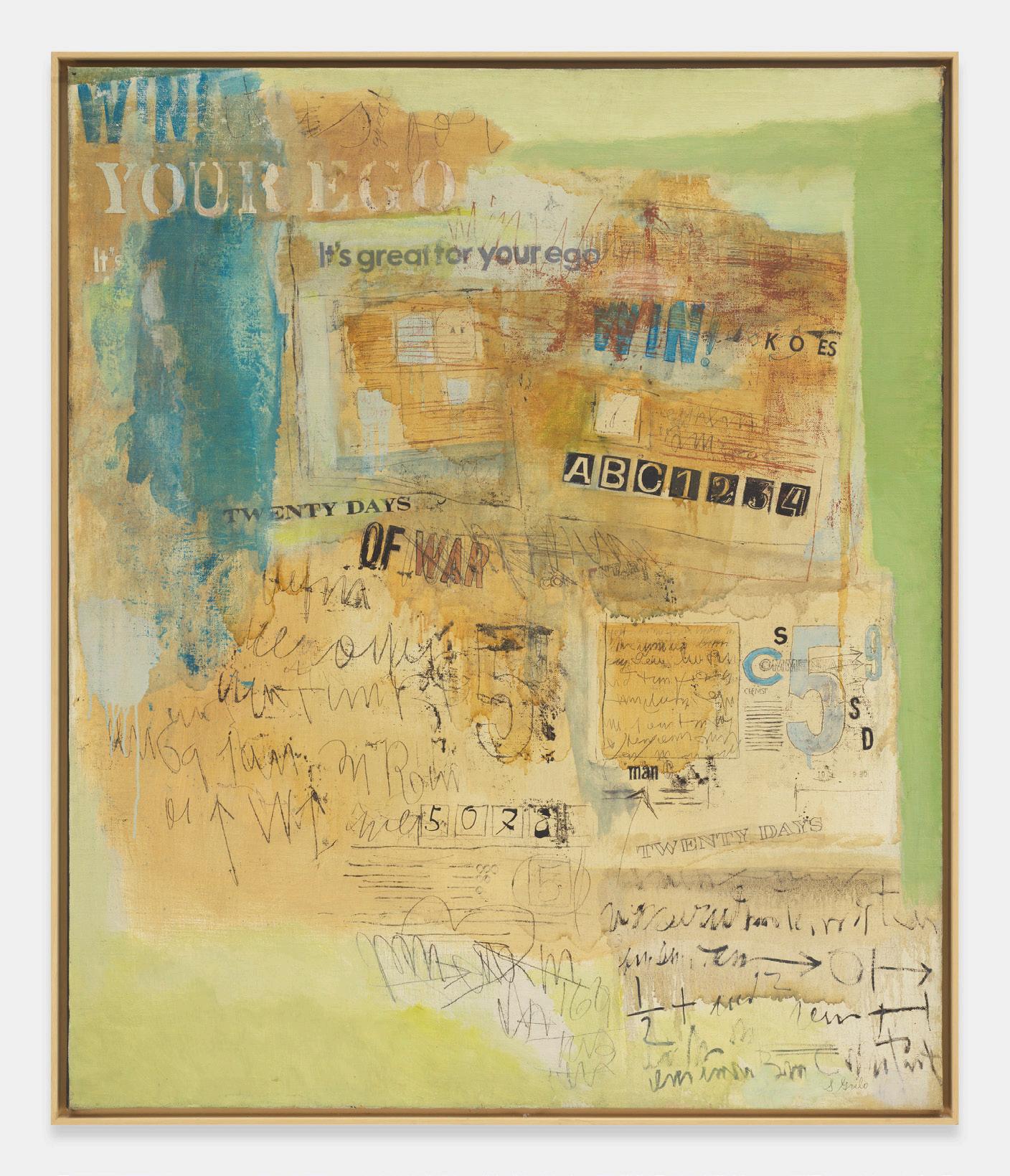

Also shown at Byron was Win, it’s great for your ego (p. 47), where the forty-nine-year-old artist and mother of a teenage boy parodies the boastful heroic rhetoric of a nation in warfare. Over a field of sandy browns and ochre tones, she concocts another instance of linguistic collage, this time using a combination of oil transfers and stencils to make up the phrase that gives the work its title. ‘It’s great for your ego’ was in fact the leading phrase of an advertisement campaign launched by Supp-hose Stockings, a company of hosiery products for women (fig. 7). In this commercial, a black and white photograph shows a young woman dressed in cocktail attire, laughing energetically as she falls back on a couch, showing off her legs—an image of domestic refinement infused with joyful sensuality. The headlining phrase, taking up the upper

36 Friedan, Feminine Mystique, p. 21.

37 Gunnar Myrdal, quoted in Martha Weinman Lear, ‘The Second Feminist Wave’ in New York Times, March 10, 1968, p. 50.

|

half of the page with its bold type, promised women wearing support hose a boost of self-esteem. One of these ads was printed in the March 1966 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal, the women’s magazine that had, in 1963, introduced readers to Friedan’s notion of a ‘feminine mystique’ before this idea was shaped into a book.38 Friedan, who was a staff writer for LHJ at the time, would be at the epicentre of a sit-in protest staged by feminist collectives in 1970, when they occupied the offices of LHJ and held its editors hostage in demand of editorial representation. In January 1966, when Grilo completed this painting, LHJ was the leading subscription-based women’s magazine in the country, and fulfilled its educational purpose by addressing the topics that had given rise to the women’s liberation movement.39 Yet, on the multiple pages reserved by the magazine for advertisements, stereotypical gender roles proliferated. By preceding the phrase transferred from the hosiery commercial with the word ‘Win’, which appears twice on the canvas, Grilo infused the tone of the original expression with a sense of irony, mocking the belligerent cries for political triumph at a moment when the US’ invasion of Vietnam was spiking. The Vietnam War saw a dramat-

ic increase of US deployment over the course of 1966, and as the conflict deepened, so did the anti-war protests.40 The coverage of the Vietnam war in the media reflected the growing hostilities, as movements largely ran by students accused the government of leading a proxy war that masked its clash with the Soviet Union. Combining found texts to inflect their original meaning, Grilo situated her painting practice at the core of the warfare issue, ridiculing the advocacy for combat. As Mignon Nixon points out, derision is a strategy firmly rooted in a feminist lineage, ever since Virginia Woolf counselled women ‘to remember, learn from, and use derision, of which they had long been objects.’41 This way, by calling out the self-glorifying implications of victory with a derisive tone, Grilo was subjugating the US anti-communist rhetoric that had initially found support in the cause for intervention in Southeast Asia. The strategy of juxtaposing texts from diverse sources reflects an awareness of the artist’s own ability to create meaning, which situates her as a discursive subject. Collage techniques have been defined as a central feminist strategy by Lucy Lippard, who ‘always claimed that the collage aesthetic—also the core image of postmodernity—is particularly feminist. Collage is about gluing and ungluing. It is an aesthetic that wilfully takes apart what is or is supposed to be and rearranges it in ways that suggest what it could be.’42 From Hannah Höch’s pioneering photomontages of the 1920’s, to contemporary takes by artists such as May Wilson, Martha Rosler and Anita Steckel, the implications of collage strategies, and the potential of the fragment as an essentially deconstructive approach, have long provided fertile grounds through which to articulate commentaries on women’s gender experiences. Grilo’s position on the Vietnam war, which she hints at through the composite nature of this work, would

Matthew

41 Virginia Woolf,

42 Lucy Lippard,

be made even more explicit a few years later, when the family left New York in order to prevent their son Juan from being drafted into the military.

A guestbook from Grilo’s exhibition at Byron Gallery collects the signatures of visitors, including art world personalities such as Kynaston McShine, then curator at the Jewish Museum, the French artist Arman, and Latin American artists Gyula Kosice, César Paternosto, Julio Alpuy, Marcelo Bonevardi and Armando Morales.43 But the exhibition wasn’t nearly as popular among press reviews. In a New York Times write-up, art columnist John Canaday enthusiastically described the ‘considerable visual appeal’ of Grilo’s work, but stopped short at welcoming the works’ new political dimension. ‘These pleasant panels are asked to carry a burden of social commentary (…) that is too heavy for them. These messages are in no way articulated with the aesthetic character of the painting, which is graceful and fluent. Take the painting, let the message go,’44 he concluded. Canaday’s statement implied a high-modernist judgement that deemed political sentiments to fall outside the realm of artistic concerns.45 Canaday, like his formalist contemporaries Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried, preferred painting to be limited to its own area of competence, remaining autonomous, self-preserved and free from social commentary.46 Although the era of high-modernist abstraction was fizzling out, some of these critics still occupied influential editorial spaces, and perceived as opinion-makers. They were vehemently opposed to art that displayed any kind of social awareness in figurative or oth-

43 Guestbook from the exhibition ‘Sarah Grilo’ at Byron Gallery, New York. May 2-27, 1967. Archives of Sarah Grilo ISLAA, n.p.

44 John Canaday, ‘Art: ‘Snapshots’ by Robert Harvey’, New York Times, May 13, 1967, p. 28.

45 Megan Kincaid, ‘An Almost Inescapable Complement’: The Archive of Sarah Grilo and José Antonio Fernández-Muro’ in Serrano Ortiz de Solórzano, Blanca, ed., Vistas 6 (New York: ISLAA), p. 12.

46 See Clement Greenberg ‘Avant-Garde and Kitsch’ (1939) in Art and Culture. Critical Essays (Boston: Beacon Press, 1965), ps. 10-44; and Michael Fried, ‘Art and Objecthood’, Artforum (Summer 1967), ps. 12-23.

erwise legible ways. The failed reception of Grilo’s political-pop paintings, which rejected the idea of abstraction as emancipated from the experience of everyday life, must be understood in the context of these commanding spirits. Moreover, this resistance towards Grilo’s work masked an inability to see and read (and therefore, deem relevant) the work of an immigrant woman artist who was operating at the crossroads of Pop art and language.

Canaday’s review in the New York Times touches upon one of the crucial issues that have sentenced Grilo’s legacy to relative obscurity: the interpretation that generalizes her deployment of linguistic symbols as a consequence of her witnessing graffiti on the walls of New York City.47 This reading only partially describes Grilo’s complex approach to painting during her New York years, while obscuring the intelligibility of her work at large. Contrary to graffiti’s spontaneity, immediacy and clandestine nature, Grilo’s mark-making process is deliberately forthright, pinned with an authorial signature, and staged within a sanctioned field of artistic agency. Neither anonymous nor clandestine, her linguistic inscriptions are often structurally and morphologically distinct from graffiti, and must be recognized as marks strictly sui generis. In Canaday’s write-up, the critic recurs in the narrative of graffiti’s ramification in Grilo’s paintings when he writes, ‘Miss Grilo concocts large paintings that resemble sections of scaling walls liberally disfigured with graffiti and the remnants of posters and broadsides.’48 One may perceivably discern a kind of hermeneutical synecdoche at work here, where the rubric of ‘graffiti’ serves a double-purpose: first, it encompasses a wide range of various inscriptions, some of which have nothing to do with free-hand spontaneity; and secondly, it resorts to a positivist perspective

47 This interpretation of Grilo’s work dates to Damián Bayón’s article ‘Cuatro pintores argentinos de Nueva York’, La Nación (December 6, 1964), and was perpetuated, among many others, by Manuel Mujica Láinez (1969), culminating in the exhibition Aesthetics of Graffiti at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1978, which legitimized this line of thought.

48 Canaday, ‘Art’

that explains a stylistic shift as a response to an environmental influence. This prevailing interpretation of Grilo as an artist inspired mainly by graffiti, which pervades in the understanding of her work to this day, can be challenged by deconstructing her mark-making process with a careful recognition of its specificities and the different sources that informed it. While her free-hand calligraphic inscriptions over patched backgrounds with visible brushstrokes may sometimes invoke the vision of a scaled wall, the reductionist likening of her canvases to graffiti oversimplifies the complexity of her work.

This dismissal of Grilo’s heterogeneous mark-making process as an all-encompassing trait of graffiti reveals an inability to achieve an integral reading of her work, perpetuating what feminist art historian Griselda Pollock coined ‘the myth of feminine indecipherability.’49 Pollock has written extensively about the incongruity between the paradigms of feminism and modernism, explaining the ways in which the modernist dogma, largely enshrined in a narrative of masculine hegemony, deemed it virtually impossible to recognize artistic merit in work that contained any trace of a differential gender perspective.50 A rectifying reading of what has hitherto been deemed illegible is imperative, and such a revisionist approach must acknowledge the various forms of difference that informed an artist’s experience. In this sense, matters of gender, language, and nationality—elements of Grilo’s experience of difference in the New York art world—must be considered if we aim to inscribe her problematic within the ‘pluralized histories of art’.51 A decade later, the subversive implications of women’s engagement with language and writing were celebrated by the feminist thinker Hélène Cixous, who encouraged women to occupy authorial spaces. Cixous called for the practice of an écriture

49 Pollock,

50 Pollock, ‘Inscriptions’, ps. 67-87.

51 Pollock, Vision and Difference. Feminism, Femininity, and the Histories of Art (New York: Routledge, 1988), p. xviii.

féminine that could invent a language for feminine desire and corporeality: ‘Woman must write her self; must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies.’52

In May of 1968, as the galvanizing winds of the cultural revolution began blowing in the urban capitals of the world, Grilo and Fernández-Muro, together with their son, began the lengthy process of relocating to Spain.53 In 1970, they definitively left behind New York City for the Spanish countryside. A letter from her friend, the German artist Mary Bauermeister, captures the spirit of her departure: ‘Dear Sara, I am sure that even if you have to spend 2 years outside of USA, it will make you happy, so dark it seems now – not to say bad things about New York, you know how much I love it, but you will like Spain.’54 In fact, Grilo’s abandonment of the scene at the turn of the decade resonated with a number of women artists and authors—the likes of Agnes Martin, Lee Lozano, Kate Millet, or Joan Didion—who were simultaneously deserting the City, owing to their disenchantment with New York’s navel-gazing institutions, the lack of opportunities, and the growing agitation in reaction to the Vietnam war. As Millet best described it in her 1974 memoir, Flying: ‘New York was making everybody sick crazy or alcoholic (…) The art world’s a tough place—”You got to be a survivor to make it.”’55 Having matured into her signature style, Grilo left America for the bucolic landscape of Marbella’s mountain range, where she envisioned the architectural plans for her family’s new home. Over the course of the next thirty years, she continued to develop a painterly practice infused with language and scribbles, often attempting monumental diptychs that resembled transportable murals. From the 1980s

52 Hélène Cixous, ‘The Laugh of the Medusa’, Signs, vol. 1, no. 4 (Summer, 1976), p. 875.

53 ‘To Spain in May ’68 – Winter in Marbella – In September we begin house in Marbella – May ‘69, we move houses – February ‘70 to New York – We stay three months in New York, return to Spain in May’. Grilo, untitled notebook, 1957-1971, n.p. Author’s translation. Archives of Sarah Grilo, ISLAA.

54 Mary Bauermeister, letter to Sarah Grilo, n.d. Archives of Sarah Grilo, ISLAA.

55 Kate Millet, Flying (New York: Ballantine Books, 1974), p. 82.

onwards, her stays alternated between Paris and Madrid, where she finally settled for the remainder of her life. Throughout her extensive career, she remained remarkably prolific and unquestionably idiosyncratic, championing a personal fusion of art and language that reverberates with agency and enunciation. Outside of America, her paintings rarely embraced English texts again. The oil transfers from the 1960s therefore retain the singularity of having enabled Grilo to embrace a foreign language, work from a space of translation, and assert her place in discourse through the embodiment of difference. In the attempt to bring Grilo’s work into legibility, this text pursued traces beyond the visible by deciphering some of her textual transfers. Further analysis on Grilo’s extensive body of work will prompt new and broader interpretations, helping her cross over the ‘threshold of institutional blindness’56 that has blurred her legacy. This first attempt at considering Grilo’s work as a site for the production of meaning was written in second language, and from the feminine, recalling Cixous’ advice that ‘it is by writing, from and toward women, and by taking up the challenge of speech which has been governed by the phallus, that women will confirm women in a place other than silence.’57 Far from the shadows, Grilo’s painterly inscriptions resonate loudly with the echoes of her unique perspective on life and art.

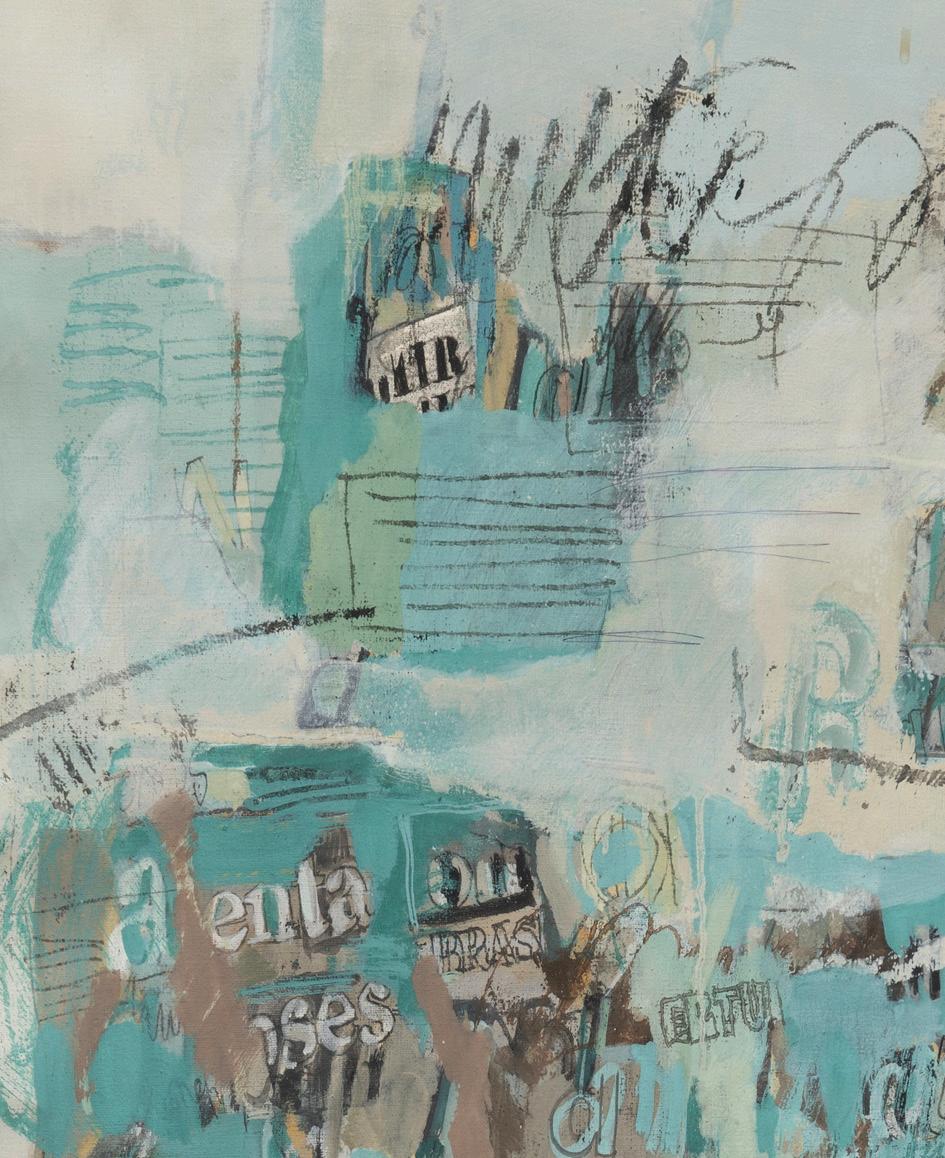

Green painting, 1963

Oil on canvas

44 x 39 ½ in (111.7 x 100.3 cm)

Green painting, 1963

Oil on canvas

44 x 39 ½ in (111.7 x 100.3 cm)

Pines, Ochres and Green, 1963

Oil on canvas

44 x 50 in (111.8 x 127 cm)

Pines, Ochres and Green, 1963

Oil on canvas

44 x 50 in (111.8 x 127 cm)

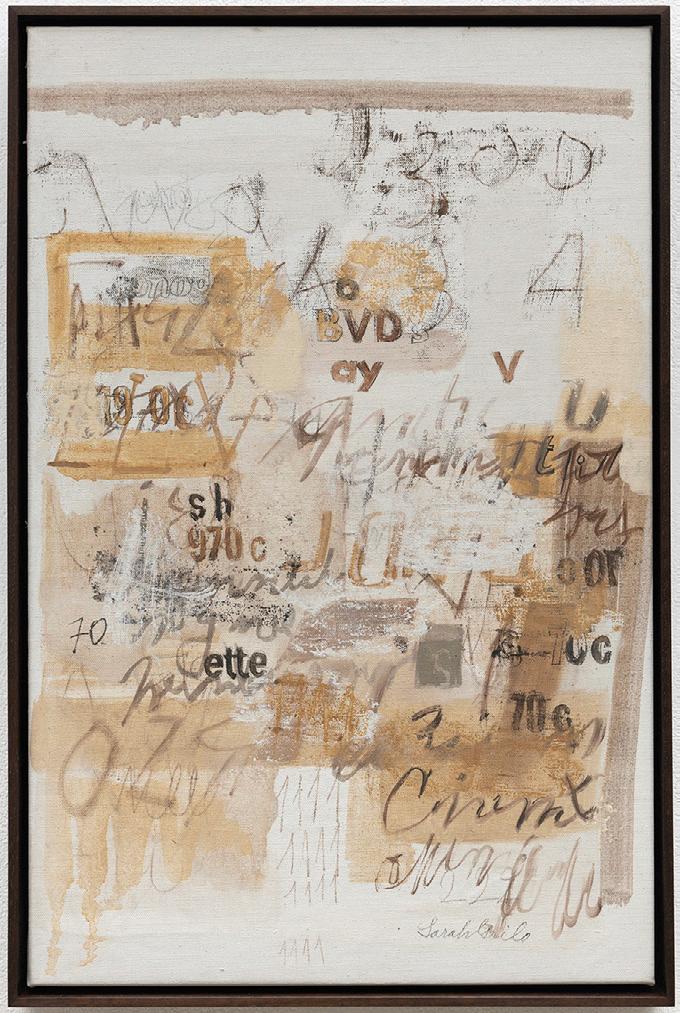

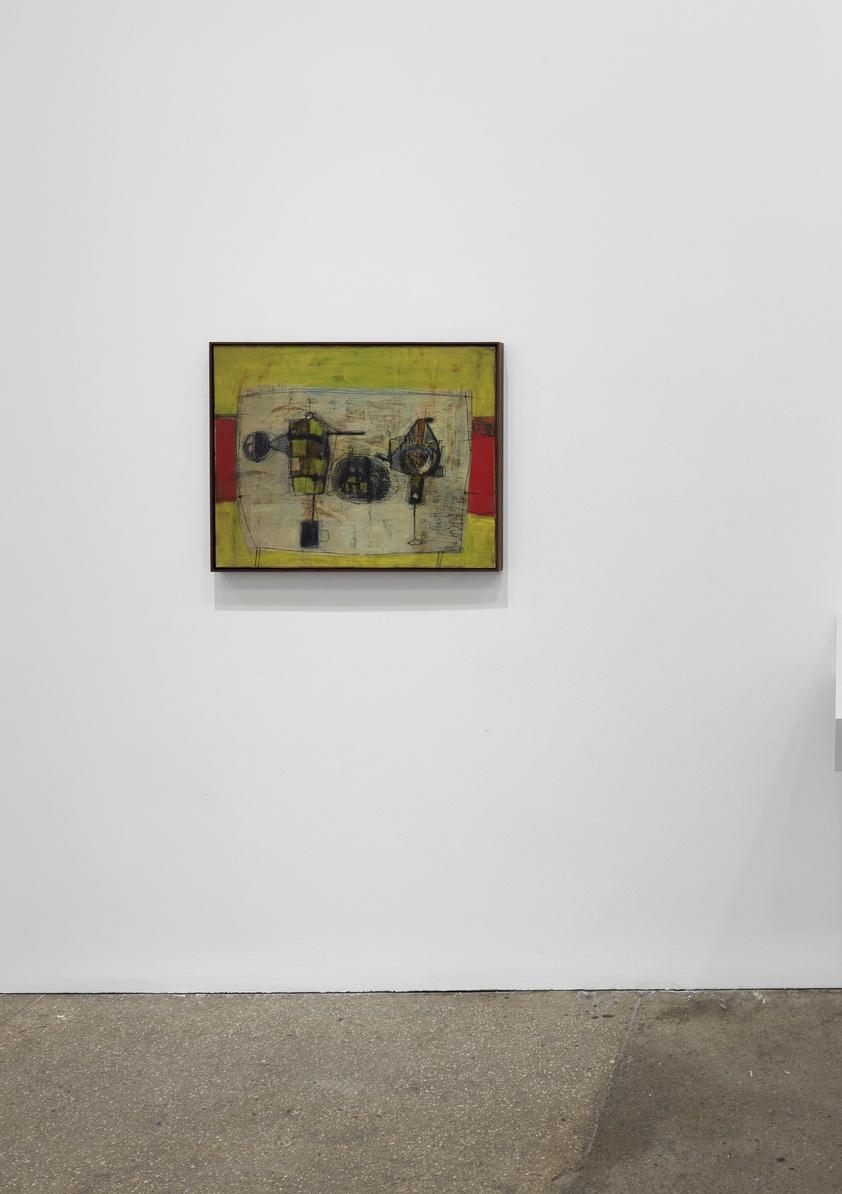

Sin título, c. 1963-67

Oil on canvas

15 ⅛ x 18 ⅛ in (38.5 x 46 cm)

Sin título, c. 1963-67

Oil on canvas

15 ⅛ x 18 ⅛ in (38.5 x 46 cm)

Charts are dull, 1965

Oil on canvas

69 x 69 in (175.3 x 175.3 cm)

Charts are dull, 1965

Oil on canvas

69 x 69 in (175.3 x 175.3 cm)

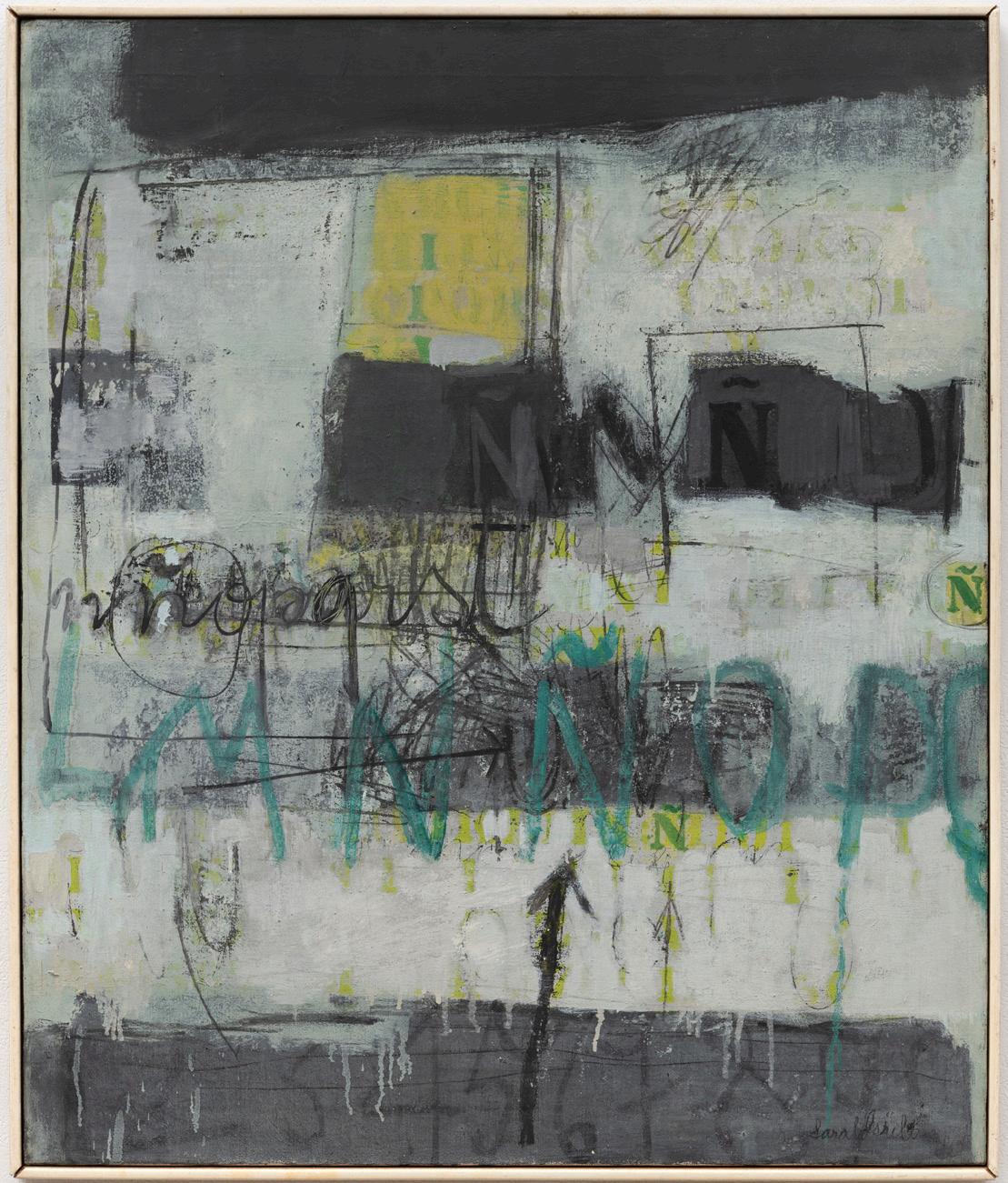

Homage to my language (letter Ñ), 1965 Oil on canvas 32 x 27 in (81.3 x 68.6 cm)

Homage to my language (letter Ñ), 1965 Oil on canvas 32 x 27 in (81.3 x 68.6 cm)

Our heroes, 1966 Oil on canvas

52 x 46 in (132 x 116.8 cm)

Our heroes, 1966 Oil on canvas

52 x 46 in (132 x 116.8 cm)

Accused Over Crisis, 1967 Oil on canvas

Accused Over Crisis, 1967 Oil on canvas

Black wall, 1967

Oil on canvas

51 ¼ x 51 ½ in (130.2 x 130.8 cm)

Black wall, 1967

Oil on canvas

51 ¼ x 51 ½ in (130.2 x 130.8 cm)

Encrucijada, c. 1970s

Oil on canvas

28 ⅝ x 28 ⅝ in (72.7 x 72.7 cm)

Encrucijada, c. 1970s

Oil on canvas

28 ⅝ x 28 ⅝ in (72.7 x 72.7 cm)

I.II.III, 1970

Oil on canvas

22 ⅞ x 15 in (58 x 38 cm)

I.II.III, 1970

Oil on canvas

22 ⅞ x 15 in (58 x 38 cm)

El mejor final, 1980

Oil on canvas

53 ½ x 66 ⅛ in (136 x 168 cm)

El mejor final, 1980

Oil on canvas

53 ½ x 66 ⅛ in (136 x 168 cm)

Born 1917, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Died 2007, Madrid, Spain

2024 The New York Years, 1962-70, Galerie Lelong & Co., New York, New York

2021 Works (1964 – 2002): First part, Maisterravalbuena, Madrid, Spain

Works (1967 – 2000): Second part, Maisterravalbuena, Madrid, Spain

Indicios, Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris, France

2018 Signos, Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris, France

Sarah Grilo and the Urban Unconscious, Cecilia de Torres, Ltd., New York, New York

2014 Cartas a Sarah, Jorge Mara la Ruche Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2000 Casa de América, Madrid, Spain

1990 Fundación San Telmo, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Galería Jacques Martínez, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Galería de Arte Contemporáneo, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1985 Museo Español de Arte Contemporáneo, Madrid, Spain

1977 Galería Art, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Galería Durban, Madrid, Spain

1976 Galería Ruiz-Castillo, Madrid, Spain

1972 Galería Juana Mordó, Madrid, Spain

1971 Galería Iolas-Velasco, Marbella, Spain

1967 Byron Gallery, New York, New York

1963 Instituto de Arte Contemporáneo, Lima, Peru

Obelisk Gallery, Washington, DC

Paul Bianchini Gallery, New York, New York

1961 Galería Bonino, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1958 Galería Bonino, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1957 Pan American Union, Washington, DC

Roland de Aenlle Gallery, New York, New York

1956 Museo Municipal, Córdoba, Argentina

1955 Galería Krayd, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1953 Galería Krayd, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1952 Galería Viau, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1950 Galería Viau, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1949 Galería Palma, Madrid, Spain

2023 Action, Gesture, Paint | Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940–70, Whitechapel Gallery, London, UK; Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Germany

In the Shadow of Dictatorship: Creating the Mu-

seum of Spanish Abstract Art, The Meadows Museum, Dallas, Texas

1966, Spain’s awakening: An artists’ museum of the future, Ludwig Museum, Koblenz, Germany

2022 To Write Down All Their Names, Palais Populaire by Deutsche Bank, Berlin, Germany; Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Helga de Alvear, Cáceres, Spain

Los caminos de la abstraccion, 1957-1978, La Pedrera, Barcelona, Spain

El paisaje invisible, Xippas, Punta del Este, Uruguay

«El pequeño museo más bello del mundo». Cuenca, 1966: una casa para el arte abstracto, Centro José Guerrero, Granada, Spain

2021 The City as Muse: Works by Lidya Buzio and Sarah Grilo, Cecilia de Torres, Ltd., New York, New York

Signografías, Galería Jorge Mara-La Ruche, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2020 Realismo mágico: una cartografía de la América Profunda. Obras de la colección del MACLA, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Latinoamericano (MACLA), Buenos Aires, Argentina

TRANSFORMACIONES - Mujeres artistas entre dos siglos, Fundación CajaCanarias, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain

Chróma, Galería Jorge Mara-La Ruche, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Crear Mundos, Fundación PROA, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2019 Art Latin America: Against the survey, Davis Museum at Wellesley College, Wellesley, Massachusetts

Grilo/Fernández-Muro: 1962-1984, Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, New York, New York

2018 Abstracting Gender, Cecilia de Torres, Ltd., New York

The Second Sex (The Estrellita B. Brodsky Collection), ANOTHER Space, New York, New York

Déjà vu, Galería Jorge Mara-La Ruche, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2017 Poéticas del Gesto, Museo de Arte Contemporaneo Latinoamericano, La Plata, Argentina 40th anniversary. Twentieth Century Art Collection. 1977-2017, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Alicante, Alicante, Spain

Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar

Abstraction, Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

2016 The Lines of the Hand, Jorge Mara la Ruche Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2015 Déjà vu, Jorge Mara la Ruche Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina

La explosión de la forma, Museo de Arte

Tigre, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Versiones De Lo Real. Obras De La Colección

Del Macla, Museo de Arte Contemporaneo Latinoamericano, La Plata, Argentina

Impulse, Reason, Sense, Conflict., CIFOCisneros Fontanals Art Foundation, Miami, Florida

The Color of Dreams / Monochrome Scenes, Jorge Mara la Ruche Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2014 Confluencias, Museo de Arte Contemporaneo Latinoamericano, La Plata, Argentina

Múltiples, Galeria Jacques Martínez, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Rojo(S), Jorge Mara la Ruche Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2012 Constellations: Constructivism, Internationalism, and the Inter-American Avant-Garde, Art Museum of the Americas, Washington, DC

Abstracción Latinoamericana - Una propuesta, Galería Artur Ramon Art, Barcelona, Spain

2010 Imán: Nueva York, Fundación PROA, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2007 José Antonio Fernández-Muro & Sarah Grilo: Obra sobre papel, Jorge Mara la Ruche Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Buenos Aires - Escenarios de Luis Seoane, Fundación Luis Seoane, A Coruña, Spain

2006 El Genaro de la A a la Z, Museo Genaro Pérez, Cordoba, Argentina

Muestra patrimonial del MACLA, Museo de Arte Contemporaneo Latinoamericano, La Plata, Argentina

Geometry and Gesture, Art Museum of the Americas, Washington, DC

2003 Fernández-Muro, Grilo, Pucciarelli, Sakai - Los que no volvieron, Fondo Nacional de Las Artes, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2001 Past Present Future - Notions of Time in Twentieth-Century Art, Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, Texas

1999 International XX Century Art, CDS Gallery, New York, New York

1994 Latin American Women Artists 1915-1995, Milwaukee Art Museum, Wisconsin; Phoenix Art Museum, Arizona; The Denver Art Museum and Museo de las Américas, Colorado; The National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.; Center for the Fine Arts, Miami, Florida

1993 Confluencias: Artistas Iberoamericanos en Europa,

Museo Camón Aznar de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain; Centro de Arte Moderno de Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain

1992 Hecho de Palabras, Galería Jorge Mara, Madrid, Spain

1991 Pinturas de los 60, Galería Jacques Martínez de Buenos Aires, Argentina

1990 Sarah Grilo / José Antonio Fernández-Muro. Pinturas 1980-1989, Fundación San Telmo, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1989 The Latin American Presence in United States, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Bronx, New York; San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego, California

1987 The Latin American Spirit: Art and Artists in the United States, 1920-1970, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Bronx, New York

1986 Más allá del Río de la Plata, Palacio de Congresos y Exposiciones, Madrid, Spain

1984 Mujeres en el Arte Español, Centro Cultural Conde Duque, Madrid, Spain

1983 100 Artistes de l’Amérique Latine, Maison de la culture à Amiens, Amiens, France

1982 Droits Socialistes de l’Homme, Grand Palais, Paris, France

1979 1ª Bienal de Arte Sheraton, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1978 The Aesthetics of Graffiti, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California

1977 Arte Actual de Iberoamérica, Instituto de Cultura Hispánica, Centro Cultural de la Villa, Madrid, Spain

1974 Mujeres Ante el Arte, Galería Iolas-Velasco, Madrid, Spain

1971 Argentinische Kunst der Gegenwart, Kunsthalle, Basel, Switzerland; Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn, Germany; Kunsthaus Hamburg, Germany

Galerie Christophe Dürr, Munich, Germany

1970 Pintura Argentina, 1923-1969, Ministerio de Cultura y Educación, Argentina

1968 Expo 68, San Antonio, Texas

I Bienal de Arte Coltejer, Medellín, Colombia

Premio Fundación Lorenzutti, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1967 Latin American Art, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

1966 Art of Latin America since Independence, Yale University Art Gallery, Connecticut; University of Texas Art Museum, Austin, Texas; San Francisco Museum of Art, California; La Jolla Museum of Art, California; Isaac Delgado Museum of Art, New Orleans, Louisiana

Women in Contemporary Art, Duke University,

Durham, North Carolina

1965 20 Pintores Argentinos, Club General Pueyrredón, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Argentina en el Mundo, Artes Visuales 2, Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture, College of Fine and Applied Arts, Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois

1964 Latin American Art Today, Trinity School, New York, New York

New Art from Argentina, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota; Akron Art Museum, Akron, Ohio; Atlanta Art Association, Atlanta, Georgia; University of Texas Art Museum, Austin, Texas

Painters resident in the USA from the Latin Americas, Institute of Contemporary Art, Washington, DC

The Emergent Decade, Museo de Bellas Artes, Caracas, Venezuela

Magnet: Nueva York, Galería Bonino, New York

1963 Adquisiciones y Donaciones de Amigos del Museo, Museo de Bellas Artes, Caracas, Venezuela

Arte de América y España, Madrid, Spain

1962 Nutida konst från Argentina, Liljevalchs

Konsthall, Stockholm, Sweden

1961 Latin America: New Departures, Time and Life Building, New York, New York; Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, Massachusetts

Premio Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, Buenos Aires, Argentina

VI Bienal de São Paulo, Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Premio Werthein de Pintura Argentina, Galería

Van Riel, Buenos Aires, Argentina

9 Painters of Argentina, Wigder Gallery, Washington D.C.

1960 Cinco Pintores, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Primera Exposición Internacional de Arte Moderno Argentina 1960, Museo de Arte Moderno de Bahía, Bahia, Brazil; Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina

30 Latin American Guest Artists, Riverside Museum, New York, New York

Permanent Collection of Contemporary Art of Latin America, Pan American Union, Washington, DC

Galería Bonino, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1959 South American Art Today, Museum of Fine Art, Dallas, Texas

The United States Collects Pan American Art, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago,

Illinois

Colección de Arte Interamericano, Museo de Bellas Artes Caracas, Caracas, Venezuela

Arte Latinoamericano Contemporáneo, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia

1958 Pintura Argentina, Instituto de Arte Contemporáneo de Lima, Lima, Peru

Pittsburgh International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Exposition Universelle, Brussels, Belgium

1957 Pintura Panamericana, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Buenos Aires, Argentina

1956 XXVIII Venice Biennale, Biennale de Venice, Venice, Italy

Fourth International Biennial of Contemporary Color Lithography, Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati, Ohio

A Century and a Half of Painting in Argentina, National Gallery, Washington, DC

1953 II Bienal de Sao Paulo, Biennale de Sao Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Grupo de Artistas Modernos, Galería Viau, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Un Siglo de Arte Argentino, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Buenos Aires, Argentina

II International Contemporary Exhibition, New Delhi, India

Primer Salón Peuser de Pintura Argentina Joven, Salón Peuser, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1952 Grupo de Artistas Modernos, Museo de Arte Moderno, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1951 15 Pintores Argentinos, Galería Bonino, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1943 Homenaje a Vicente Puig, Galería Witcomb, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Art Museum of the Americas, Washington, DC

Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, United States

Chase Manhattan Bank Art Collection, New York, New York

Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation, Miami, Florida

Colección Banco Santander, Madrid, Spain

Colección Circa XX Pilar Citoler, Madrid, Spain

Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas

Fundación Coltejer, Medellín, Colombia

Instituto de Arte Contemporáneo, Lima, Peru

Museo de Arte Abstracto de Cuenca, Cuenca, Spain

Museo de Arte de Cartagena, Cartagena, Colombia

Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Almería, Almería, Spain

Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Latinoamericano de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina

Museo de Artes Plásticas Eduardo Sívori, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Museo de Bellas Artes, Caracas, Venezuela

Museo Internacional de la Resistencia Salvador Allende, Santiago, Chile

Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

Museo Municipal de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Museo Municipal de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina

Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

p. 33

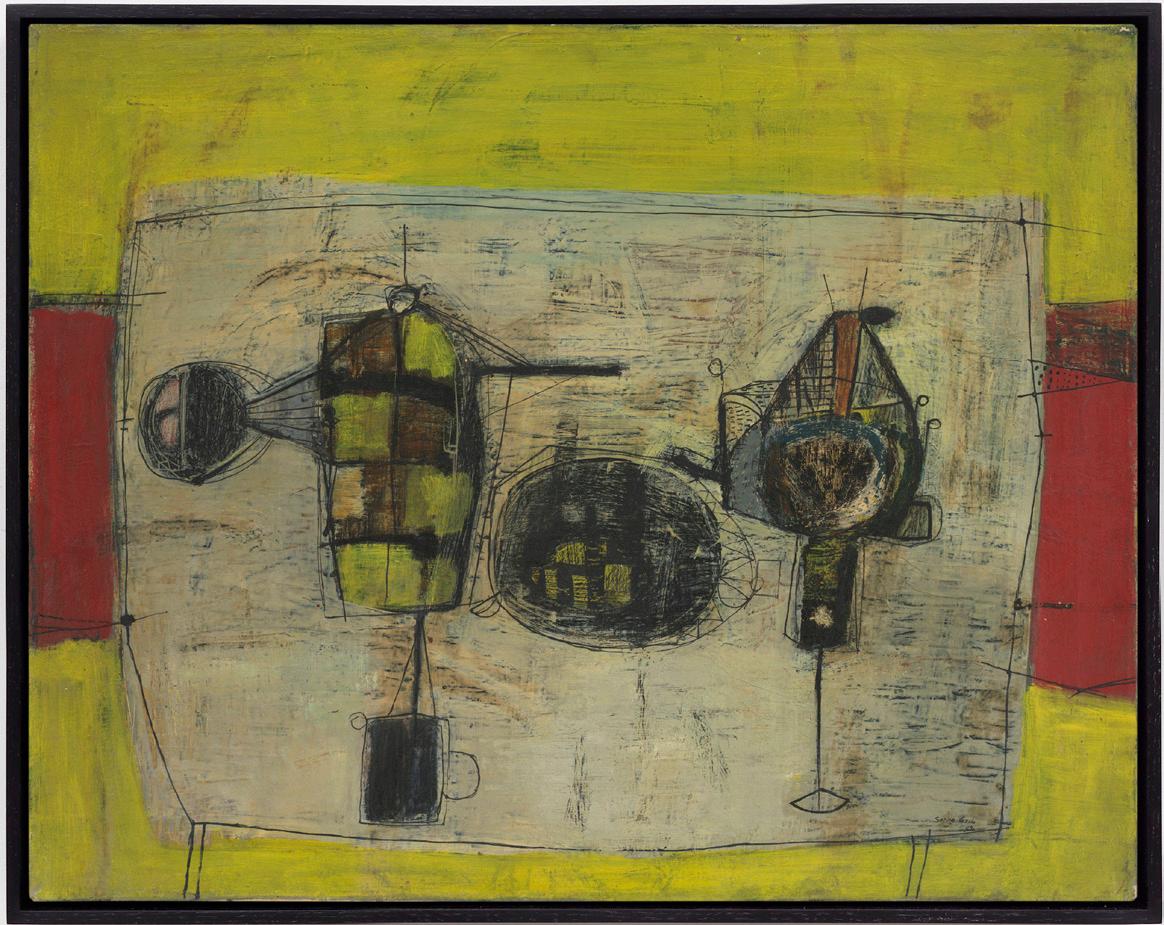

Pintura, 1953

Oil on canvas

23 ⅞ x 26 ⅜ in (60.5 x 67 cm)

p. 34

Green painting, 1963

Oil on canvas

44 x 39 ½ in (111.7 x 100.3 cm)

p. 37

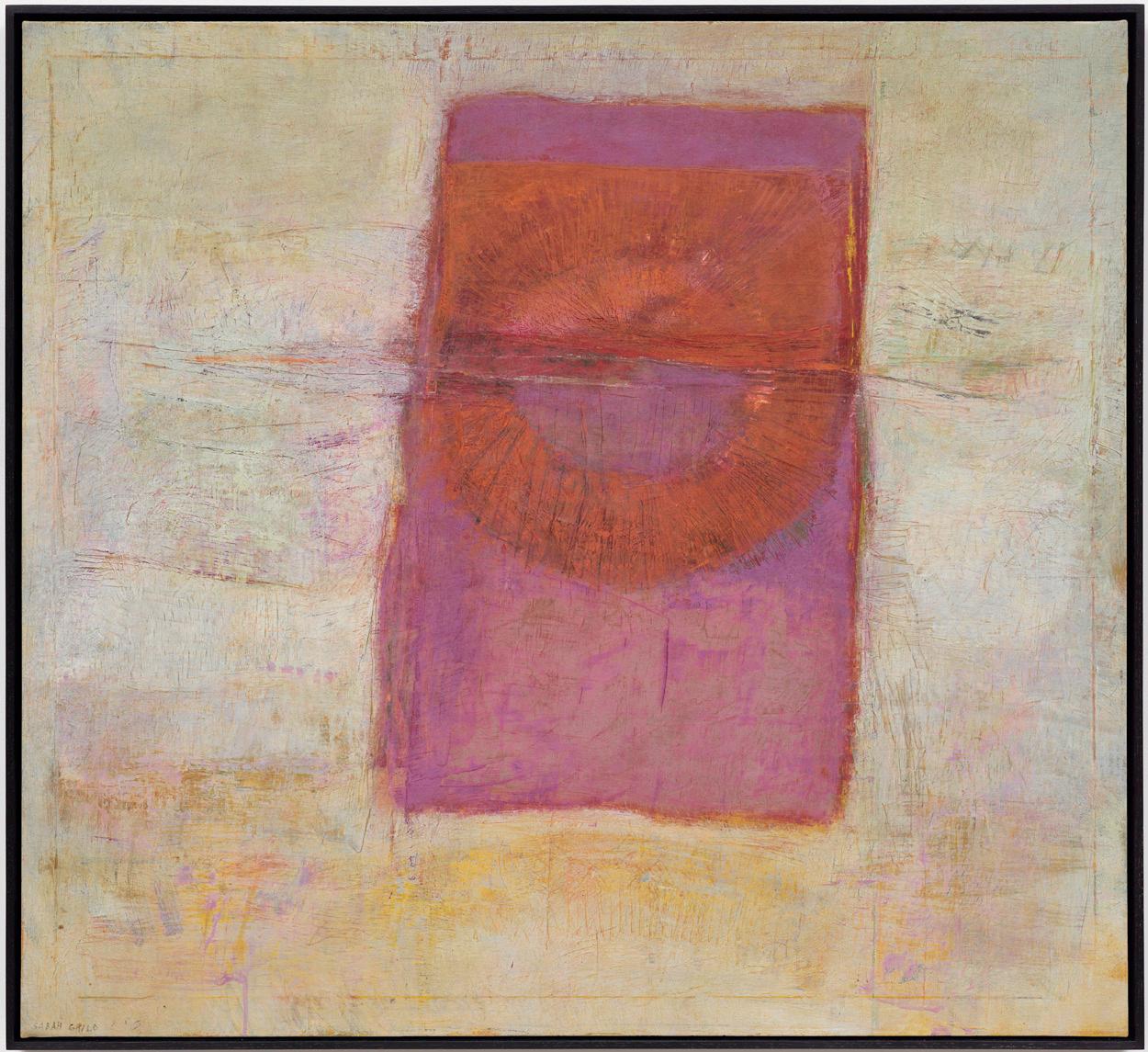

Orange and mauve, 1963

Oil on canvas

39 ⅜ x 43 ¼ in (100 x 110 cm)

p. 38

Pines, Ochres and Green, 1963

Oil on canvas

44 x 50 in (111.8 x 127 cm)

p. 40

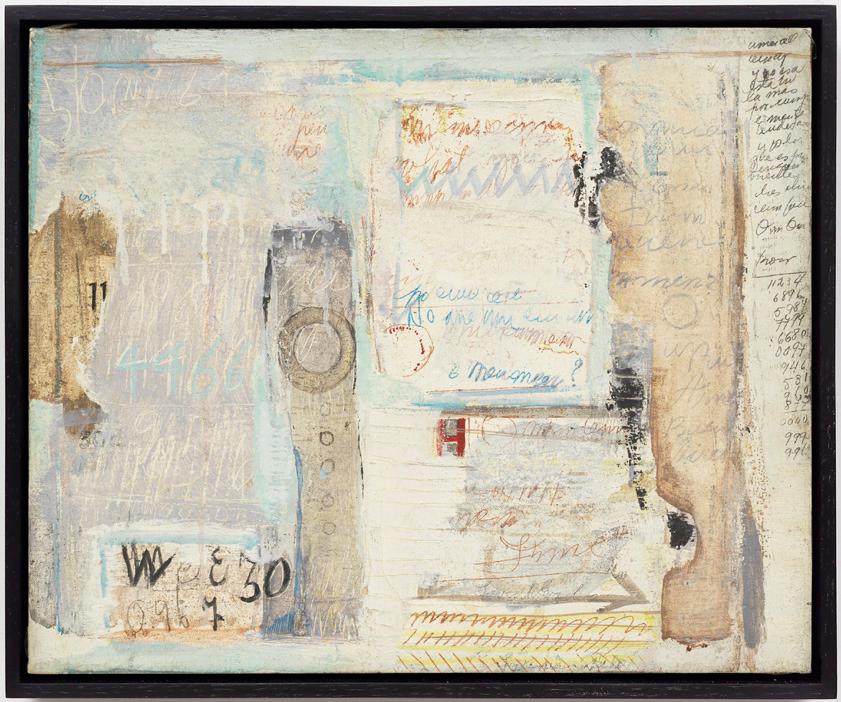

Sin título, c. 1963-67

Oil on canvas

15 ⅛ x 18 ⅛ in (38.5 x 46 cm)

p. 41

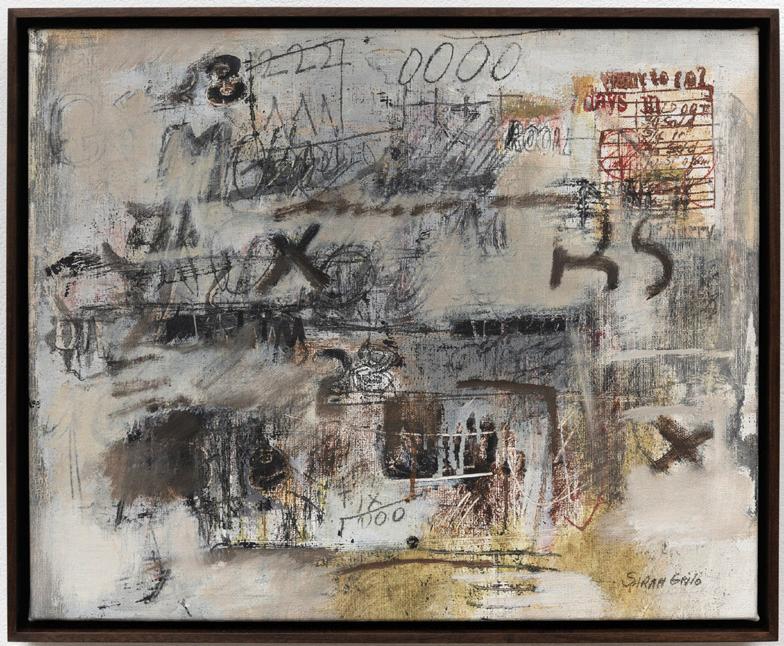

Days (Four Zeroes), 1964

Oil on canvas

14 ½ x 17 in (36.8 x 43.2 cm)

pp. 42-43

Charts are dull, 1965

Oil on canvas

69 x 69 in (175.3 x 175.3 cm)

p. 44

Homage to my language (letter Ñ), 1965

Oil on canvas

32 x 27 in (81.3 x 68.6 cm)

Estrellita B. Brodsky Collection

p. 47

Win, it’s great for your ego, c. 1965-66

Oil on canvas

49 ¾ x 41 ¾ in (126.4 x 106 cm)

p. 48

Our heroes, 1966

Oil on canvas

52 x 46 in (132 x 116.8 cm)

p. 50

Accused Over Crisis, 1967

Oil on canvas

21 ½ x 47 ¼ in (54.6 x 120 cm)

Private Collection

p. 51

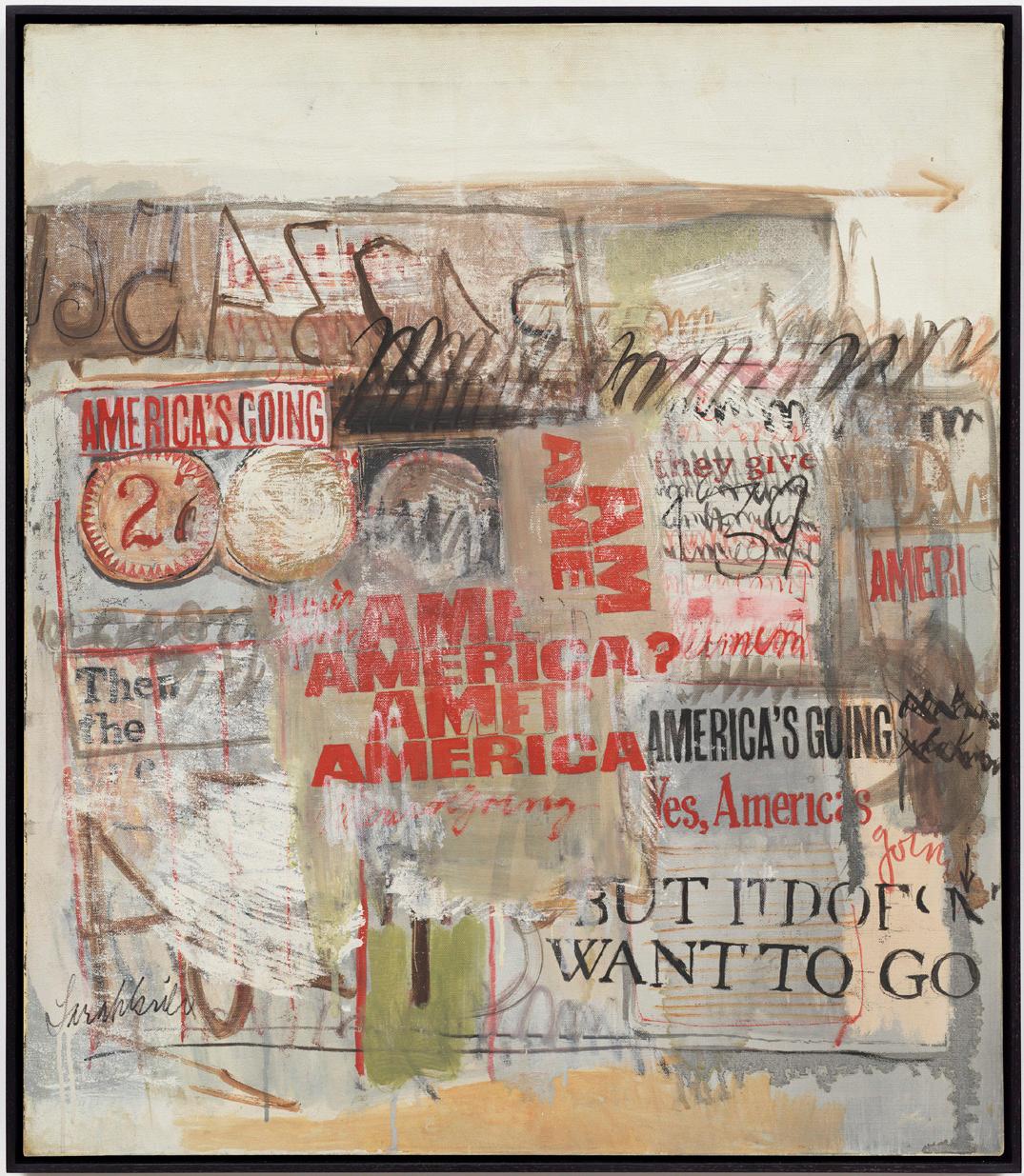

America’s going..., 1967

Oil on canvas

30 ⅛ x 26 in (76.5 x 66 cm)

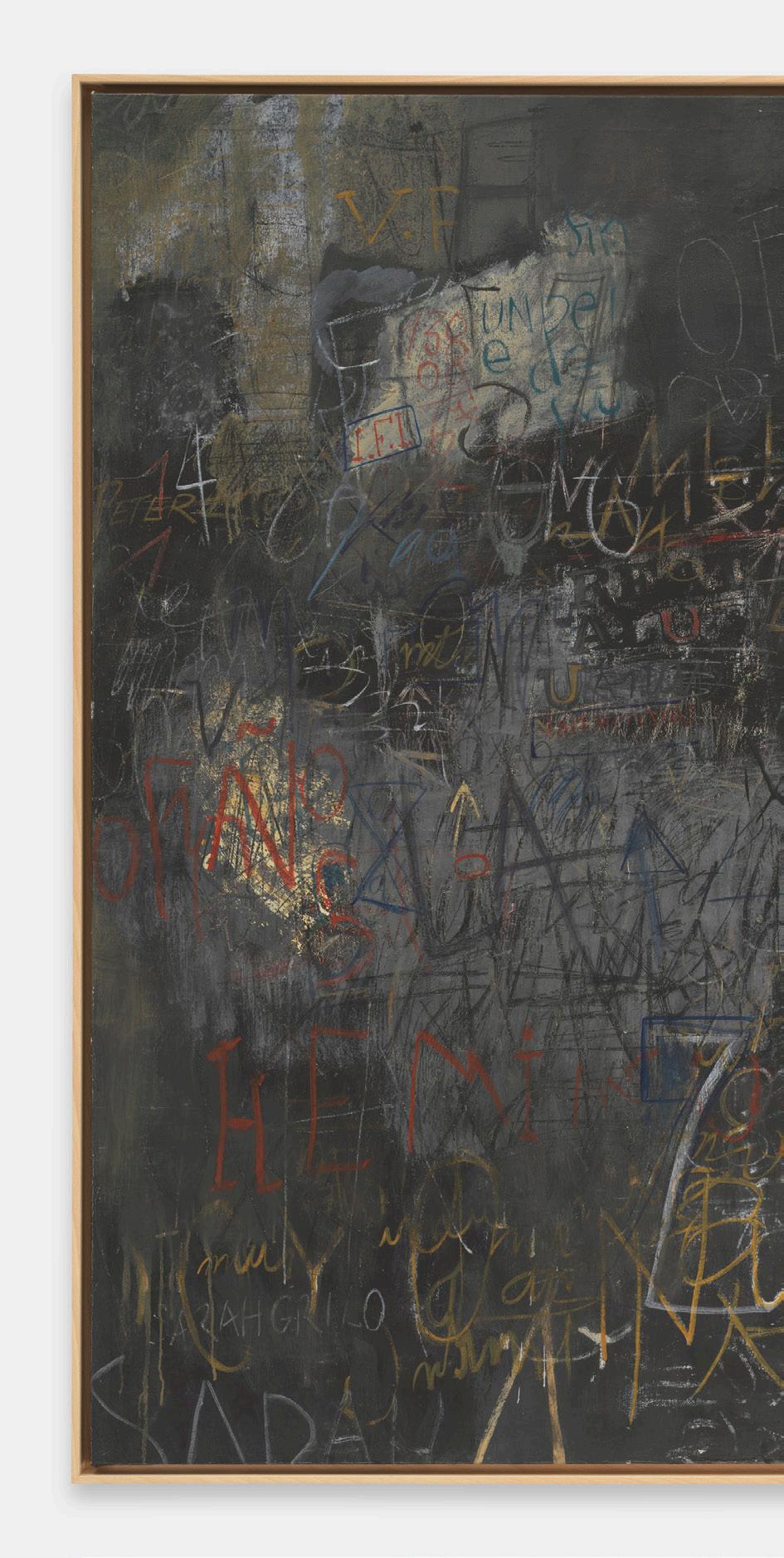

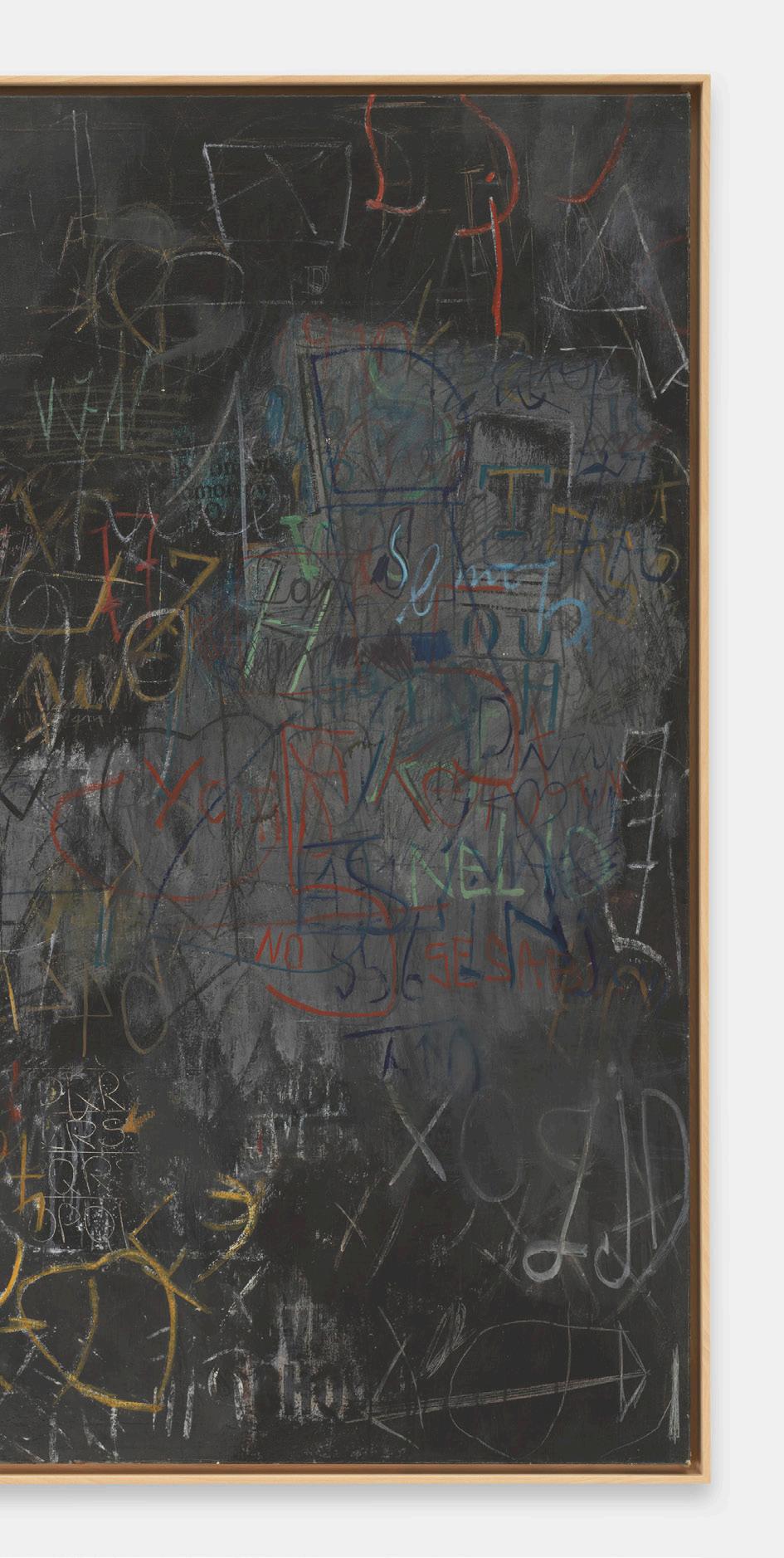

pp. 52-3

Black wall, 1967

Oil on canvas

51 ¼ x 51 ½ in (130.2 x 130.8 cm)

p. 55

Contrapunto, 1970

Oil on canvas

51 ⅛ x 44 ⅞ in (129.9 x 114 cm)

p. 56

*Encrucijada, c. 1970s

Oil on canvas

28 ⅝ x 28 ⅝ in (72.7 x 72.7 cm)

p. 57

*TME, c. 1970s

Oil on canvas

53 ½ x 54 in (136 x 137 cm)

p. 58

I.II.III, 1970

Oil on canvas

22 ⅞ x 15 in (58 x 38 cm)

p. 59

Protesta, 1973

Oil on canvas

31 ⅞ x 39 ⅜ in (81 x 100 cm)

p. 62-3

El mejor final, 1980

Oil on canvas

53 ½ x 66 ⅛ in (136 x 168 cm)

*works not exhibited in Sarah Grilo: The New York Years, 1962-70, Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

Published in conjunction with the exhibition

Sarah Grilo: The New York Years, 1962-70

Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

Published by Galerie Lelong & Co.

528 West 26th Street New York, New York 10001

+1 212 315 0470

art@galerielelong.com

www.galerielelong.com

13 rue de Téhéran

75008 Paris, France

+33 1 45 63 13 19

Design: Rita Edwards

Publication manager: Katherine Chan

© 2024 Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

All texts © the authors

All works © The Estate of Sarah Grilo, courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., unless otherwise noted

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or by any means whatsoever without written permission from the publisher.

All photos: Christopher Burke Studio, unless otherwise noted

p. 8

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy Estate of Sarah Grilo.

p. 14

Archives of Sarah Grilo, on loan at the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art, New York.

p. 15

Gelatin silver print

30 x 30 cm

© Archivio Claudio Abate.

Courtesy Galería del Infinito, Buenos Aires.

p. 17

Archives of Sarah Grilo, on loan at the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art, New York.

p. 18

Offset print on paper

26.8 cm x 17 cm.

p. 22

Offset print on paper

26.8 x 17 cm

p. 24

Offset print on paper

27 x 17 cm.

pp. 41, 44, 50, 58-9

Photos by Jon Cancro.

pp. 66-79

Photos by Thomas Muller.

p. 83

Sarah Grilo.

Photo by Lisl Steiner.

Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Grilo and the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA).