8 minute read

Farm City USA

BY EVAN FOLDS

It’s true; our agricultural system is not focused on nourishing people. Our doctors, and eaters, and farmers are not on the same page. Doctors treat symptoms, most eaters have no idea where our food comes from, and farmers are simply unappreciated.

There is a disconnect between food, farming, and public health and a clear corporate bias exhibited in science and government. It has resulted in excessive environmental toxicity and is implicated in the epidemic levels of chronic illness currently being experienced in the United States. When it comes to painting this picture, the truth doesn’t always reach the right data point.

The conventional agricultural system is broken. The commodity farming system implemented through the USDA Farm Bill is failing corn and soy farmers, and the dairy industry that has long been subsidized is being disrupted with farms failing daily across the country. The enormous level of toxicity created by conventional agriculture has been tied directly to ecosystem failure, with glyphosate being found in all sorts of major food brands and our failing soils attributed to climate change. Conventional agriculture is being exposed for the civilizational drain that it is, and, in turn, farmers are hurting.

The silver lining is that these conditions are ripe for fundamental change in our agricultural policy. The emergence of regenerative agriculture can be seen in the campaign platforms of 2020 Presidential candidates. Both Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have released detailed and quite radical agricultural policy agendas, and the topic is regularly mentioned in several of the other candidate’s campaigns. Politicians follow; they do not lead, so this development is a positive sign for the change to come.

There is an impulse towards a revolution in farming and its place in our way of life that can be seen in places like Detroit and their urban agriculture movement, or on industrial farms transitioning to regenerative methods with the help of groups like Farmers Footprint. There is also a rise of homesteaders with movies like Big Little Farm making the rounds in mainstream movie theaters.

Planting food is part of who and what we are. Farming was the first human act and is uniquely positioned to be a regenerative therapy for human culture. From hunger to health care and jobs to climate change, if we find the political will, we can leverage agriculture in powerful ways that make progress one of the pressing issues of our time.

What we have now is a centralized agricultural system built to maximize profit for shareholders. The way our food system has been constructed, there is no subsidy for vegetable farmers, and there is no incentive for farmers to grow better food. These modern challenges demand new economic thinking and new diversified and decentralized ways of being.

It turns out that a regenerative farm is an ideal model for how to run a city. One of the lessons of Rudolf Steiner’s biodynamic agriculture is that the farm is an organism. There is no center to a farm or a human being, just a collaboration of different spheres of activity in resonance as a whole. A city works in the same way.

By choosing a different perspective to approach our challenges, we can go a long way toward developing solutions. We tend to approach dynamic problems with short-sighted linear thinking, but we can decide to implement techniques such as “true cost accounting,” “equity crowdfunding,” and “restorative justice.” We already have many of the answers; why do we continue to try the same things and expect a different result? Where do we go from here?

The first step is to realize that not all agriculture is the same. Family farms grow 70% of the world’s food, but that is not how it is done in the United States, the land of the mega-farm. In so many ways, the United States has done a world-class job of making sure no one wants to be a farmer. This has resulted in farmers getting older and farms getting larger.

Agriculture is one of the largest, if not the largest, industry in the world, so the special interests in agriculture are powerful. Big Ag holds sway over governments. They have successfully patented crop genetics that serve global markets, and they have a powerful lobby that mainly writes the rules of farming in the United States.

But Big Ag lives and dies on our buying power. In short, we are served what we eat, or as Wendell Berry put it, “Eating is an agricultural act.” As we wake up to this, we can begin to change the food landscape. But at the moment, the billions of dollars spent on marketing in agriculture is not intended to inform people, but to confuse them. And confused we are, with the average American diet consisting of 70% processed food and only 1 in 10 Americans eating enough fruits and vegetables daily.

Mega-farm that is becoming the norm in the United States

The renaissance of agriculture starts locally. Due to the litany of special interests baked into it, changing the federal Farm Bill is generational work, and most state governments are bought and paid for by lobbyists and corporate donations. In our city governments, we still can demand human-centered representation. We can be creative and organize around a healthy and equitable policy that raises all ships, and farming can be a potent tool in this work.

What would it look like for a city to champion agriculture?

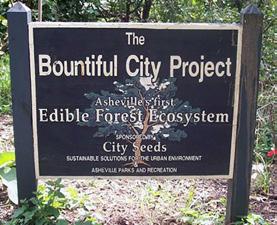

An easy place to start is by growing food crops in municipal landscaping. Boston, MA, and Asheville, NC, have impressive reputations for edible landscapes. Seattle, WA, has become a national leader in public food. They have Brandon Street Orchard, founded in 2003, and the seven-acre Beacon Food Forest is a couple of miles from downtown. Atlanta, GA, also recently announced a project to develop the largest food forest in the United States.

Example of an Edible Forest championed by the city of Asheville

Another idea is a residential “food, not lawns” initiative. Develop protocols and an incentive to grow yard farms where residents are encouraged to stop the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides and increase the organic matter of their soil. Not only would this mitigate the toxicity generated from residential lawn care, but an increase in organic matter of 1% per acre holds 25,000 gallons of water, which is a big deal to a city stormwater division.

Every city should have a dedicated urban farm where citizens can get their hands dirty. We need places where children can eat something that they planted, use the magic of cultivation for mental health and community building, and where we can teach farming as an economic development tool. The HUB Farm in Durham, NC, works this model with a significant impact through a community-supported agriculture program, high school internships, field trips, community classes, and more.

The farm could serve as an incubator that educated the public on how to develop edible urban landscapes. The eggs, honey, and crops could be collected and sold as a cooperative to local restaurants, farmers’ markets, and grocery stores. This activity is a natural cross-pollinator of energy and ideas that is sure to stimulate even more agricultural development.

Many cities are taking this a step further and adopting Directors of Urban Agriculture. The first major city was Atlanta, GA, in 2015, and, after Philadelphia in early 2019, Washington DC just announced that they would become the third major city to establish the position. Their goals include putting 20 additional acres under cultivation in the DC District by 2032, developing food-producing landscaping on five acres of public space distributed throughout all eight wards in the city, and supporting school gardens and garden-based food system education in public and charter schools. That is a big deal.

Other cities are expressing themselves in different ways. Portland, ME, recently implemented a ban on synthetic pesticides in city limits. This is no longer a radical idea, as cities across the nation learn about the dangers of pesticides to public health. People are waking up to the idea that there are alternatives, and that these alternatives are profitable toward the goal of improving public health and ending the deliberate contamination of the environment.

Composting is another act for any city that wants to take farming seriously. Arguably the top composting city in the US is San Francisco. In 2002, San Francisco set a goal of 75% diversion by 2010, and in 2003 they committed to zero waste by 2020. Hundreds of thousands of San Franciscans, as well as local restaurants and food-related establishments, contribute more than 300 tons of organic garbage each day, or more than 100,000 tons per year, to be composted and returned to the soil on local farms.

There are massive opportunities to leverage agriculture for good in our cities if we can just focus our intention. We could incentivize local farm to plate initiatives, ask hospitals to monitor the progress of real food programs, and enlist universities to study the social impacts of neighbors farming in their front yards. What if we set goals to track what percentage of food eaten in the city is actually grown there? So many ideas. What if we set goals to track what percentage of food eaten in the city is actually grown there?

What are you doing in your city?

BIO

Evan Folds is a regenerative agricultural consultant with a background across every facet of the farming and gardening spectrum. He has founded and operated many businesses over the years - including a retail hydroponics store he operated for over 14 years, a wholesale company that formulated beyond organic products and vortex-style compost tea brewers, an organic lawn care company, and a commercial organic wheatgrass growing operation.

He now works as a consultant in his new project Be Agriculture where he helps new and seasoned growers take their agronomy to the next level. What we think, we grow!