18 minute read

SUMMER SURVIVAL SERIES:

As spring edges closer to summer, the warmer weather and longer days bring plans of sun and surf at the beach, lakeside camping trips, canoes and kayaks sluicing along the currents, or just swimming laps in the pool. But fun in the water can turn into a tragic affair if safety is taken for granted. Even if you or others in your group or family are familiar with a destination, even if everyone is a competent swimmer or seasoned watersport enthusiast, there are preparations and precautions that should always be part of the trip planning.

No matter your destination, whether a community pool, the lake by a friend’s cabin, or the same coastal retreat you’ve been visiting on vacations throughout childhood, the most current information should be thoroughly reviewed beforehand. This will let you know of any changes, water conditions, environmental hazards, and the like.

Advertisement

The General And Swimming Pools

In general, for all bodies of water, always employ situational awareness. Know the weather report, but don’t rely solely on it; watch for changing conditions signaled by a shift in wind direction or speed, an abrupt or extreme fluctuation in temperature, gathering or darkening clouds. Weather, even at its most benign, has a major impact on all bodies of water, the most obvious being storms.

At the first occurrence of thunder or lightning, GET OUT OF THE WATER and take shelter. This might seem an obvious directive, but there are those who delay taking action, thinking the storm will pass quickly or go around them. You can get a rough estimate for the distance of a storm by counting the seconds between a flash of lightning and the subsequent sound of thunder; divide that by five and you’ll get the distance in miles (five seconds equals approximately one mile, fifteen seconds equals approximately three miles, and so on). But keep in mind that if you can hear thunder, you ARE within striking distance. Lightning can strike from out of nowhere, even when it seems far off. As the CDC advises: When thunder roars, go indoors!

If an enclosed shelter is not close by, avoid open areas or tall, isolated trees, and anything metallic. Also, stay away from anything that conducts electricity and do not touch electrical objects or devices. Find the lowest spot you can, but do not lie flat on the ground. It is recommended that you wait thirty minutes after the last clap of thunder or flash of lightning before going back outside and returning to the water.

Weather can affect water in other ways. Extended periods of rain and drought will factor in not only water levels, but also in the balance of natural elements that make the water safe to swim or even wade through. Above- or below-average temperatures can affect that composition, which is another reason why it’s important to be wellinformed about the most current conditions, physically and environmentally.

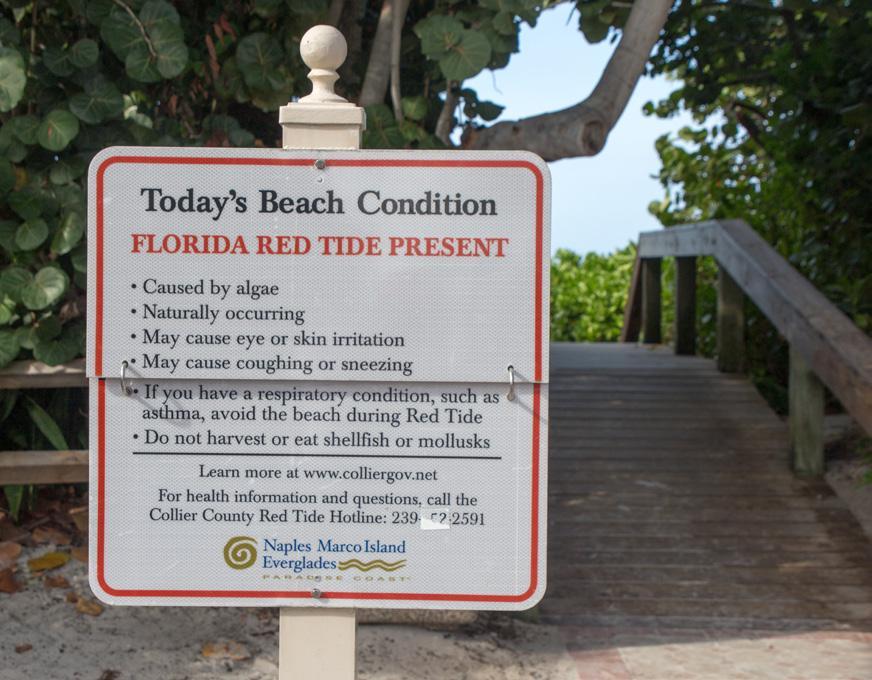

While checking the weather forecast and destination information, find out if there have been any insect infestations in the area or an outbreak of invasive species of flora or fauna; increasingly, there have been recurring instances of unhealthy biological events, such as algae blooms and red tide.

These are the kinds of things of which we have little, if any, control. But as with any survival situation, being well-informed is your best defense. This brings us to what we can control or, at least, risks we can minimize.

There are over three thousand drownings in the U.S. every year, and they can happen in a backyard kiddie pool or a bathtub, let alone an Olympic-size pool or vast, open water. The best prevention against such a catastrophe is to be constantly vigilant. Even if there is a lifeguard present, his or her eyes can only be looking in one direction at a time and, in a crowd, that monitoring is even more limited. Children should be watched by parents and supervising adults at all times in and around water and, in the case of older youth and adults, a buddy system should be in place. Someone in the group should know CPR, but if not, at the very minimum find out if there is a lifeguard or pool monitor on duty and determine their first aid capabilities. Is there a first aid kit? A defibrillator? Are there rescue aids, such as a life ring or extension pole? Know where these things are.

When reviewing the latest information about the pool you will be attending, make sure you review its Inspection Report, which should be clearly posted. Check the date of the inspection to make sure it is recent and current. These are legally required, and the absence of one, or one that is outdated, should turn you away.

For your own pool or one that is privately owned, the CDC recommends a pH of 7.2 to 7.8 with free chlorine concentration of at least 1 ppm and free bromine concentration of at least 3 ppm.

If you are watching children in water, keep your phone handy but stay off the screen! It takes mere seconds for one to go under and not many more to drown. And drowning does not just happen to the young and inexperienced; skilled or expert swimmers can drown as a result of a variety of occurrences, such as a sudden health emergency, an accident or injury, a loss of consciousness.

Even in shallow water, young, inexperienced swimmers should wear life vests—not to be confused with air-filled or foam toys, such as water wings, noodles, or inner tubes which, while helpful as teaching aids, are inadequate in preventing submersion. Know where the pool drains are and keep clear of them, as these are suction hazards and can snag hair, limbs, and clothing. Also take extra care near ladders and rope dividers.

For older kids, adults, and experienced swimmers, a warm-up stretch before going into the water is recommended to help prevent cramps and strains. For all, wear sunscreen that is at least SPF 30, reapplying every time you get out of the water; water does not protect against the sun’s rays, which are actually refracted and often amplified. Stay hydrated, drinking more water than you might normally; swimming can affect the body’s ability to regulate temperature, causing heatstroke.

Anyone who is not feeling well should obviously not go in the water, but don’t take for granted that others will follow this protocol or that the chemicals in the pool water will prevent germs and bacteria and illness from transmitting. Wear a swim cap, which will protect the hair from chemicals and also from being caught in anything and causing possible injury.

SWIMMER’S EAR

Swimmer’s Ear comes from a bacterial infection often caused by water that remains in the outer ear for a prolonged amount of time. Though anyone can get it, it is most often seen in children. Symptoms include pain, itchiness, drainage, redness, and swelling. Keeping ears dry and wearing a swim cap are preventative measures, also tilting the head back and forth while pulling the earlobe to allow water to drain. A hair dryer on the lowest settings, held several inches from the ear, can also help. Don’t put anything in the ears, including Q-Tips, as this could not only cause damage but push the water further in.

Lakes

With lakes, a good percentage of accidents and injuries occur from being uninformed or from paying little heed to the geography. Diving is especially dangerous with the variable—and often unknown—depths and uneven bottom surfaces. Always check the area you will be wading or swimming for depth and for sharp, jagged, or slippery sections. Be aware and mindful of high or low water levels; higher levels that could be due to runoff from extended rainy periods or from contaminated sources, and lower levels from drought. Posted signs may warn of contaminations, but do your own study to check for cloudy, oily, or stagnant water which could be indicative of environmental hazards.

Again, research before going, and know the specifics, including lake species you are likely to encounter, such as leeches, snakes, and fish. With fresh water, bacteria is also a concern. Aeromonas, or flesh-eating—and antibiotic-resistant—bacteria, can be life-threatening. If you jump or dive into the water, hold your nose or wear a clip, because naegleria, or “brain-eating amoeba” are also real thing and invade through the sinus cavities.

With these perils in mind, it’s a good idea to check with the CDC for the most up-to-date information on outbreaks of recreational water illnesses (RWI).

When swimming in lakes, knowing that you won’t have ropes or barriers or sides to keep you from straying, make sure you identify and use landmarks as a guide to maintain your bearings. Consider swimming parallel to the banks instead of out into the middle.

Finally, particularly for lakes, it should go without saying, avoid areas with a high density of boats and jet skis. Their operators may not see you until it’s too late, or perhaps not at all, especially if navigating at high speeds.

Streams And Rivers

These bodies of water are particularly subject to changing conditions, often rapidly, as they are affected by seasonal fluctuations and the evolution of their flow. They will swell from rainy periods and the runoff of snow and ice melt, causing tumultuous currents. Rocks and vegetation tend to be treacherously slippery from the constant stream of water and, in some cases, moss-covered surfaces.

Before setting out, let someone know where you are going, your expected time of return, and who/where to call if you don’t.

When crossing on foot, unstrap backpacks and other gear to prevent their weight from pulling you under in case of a fall, and do not tie yourself in safety ropes as they can become tangled and cause drowning. If you lose your footing or fall in fastmoving water, do not try to stand up; the water’s force will most likely take you down. There will be a great risk of getting caught on a rock or limb, so the best chance at recovery is to lay on your back, feet pointing downstream, watching for obstacles. Do not swim against the current, and to do so will sap you of energy. Wearing a personal floatation device (PFD) is especially recommended when navigating streams and rivers.

Hypothermia is a commonly overlooked peril in cooler weather, and it is important to wear protective footwear and proper clothing. Avoid all cotton materials and look for quick-drying apparel, which is typically made with synthetic fabrics or wool. If you plan on spending extended time in this environment and know you will be wet for much of it, particularly in cooler weather, consider wearing a wetsuit and booties. Layering clothing with a lightweight, waterproof windbreaker jacket and pants is ideal.

Likewise, heat exhaustion and dehydration is a risk in warmer weather. Symptoms of hypothermia include shivering, slurred speech, slow and shallow breathing, lethargy, confusion, and skin redness; for heat exhaustion, symptoms include dizziness, headache, nausea, and muscle cramps. Alcohol consumption can be a contributing factor, so it should be avoided or, at the very least, carefully moderated.

A set of dry clothing and footwear should be carried in a waterproof bag, along with a bag for wet clothes. With the uneven terrain along and within streams and rivers, water shoes are a good option. When choosing the best for your activities, look for shoes that have a sticky grip, are flexible, and made of breathable, quick-drying material. Some of the brands that make top-rated ones are Nike, Adidas, Hoka, Astral, and Xero.

Whitewater Rafting

Whitewater rafting can be an invigorating and exciting activity, but it should be approached with a realistic assessment of skills and safety precautions.

Always wear PFCs and helmets along with the proper protective clothing. When possible, take advantage of a local guide or outfitter to get an orientation of the particular river you are rafting. We could do another whole article on all aspects of rafting, but here we will just cover the different levels. You should absolutely know the full course of the river you will be rafting; in many cases, there are multiple different classes of rapids along the same river.

Class 1: Easy, with minimal risks or obstructions. Shallow, lightly moving water.

Class 2: Novice, some obstacles but easily navigable. Fun splashing.

Class 3: Beginner to Intermediate, moderately stronger currents and whitecaps. Skill starts to become more key.

Class 4: Advanced, more boisterous and churning whitewater with more restrictions, requiring faster and more strategic moves.

Class 5: Expert, for experienced and solidly skilled rafters. Currents are wild and turbulent, unrelenting and sustained. Major obstacles that are more difficult to avoid. Knowledge of the course, proper equipment, and rescue skills are a prerequisite.

Class 6: Daredevil. Need more be said?

WATERFALLS

Waterfalls are a natural wonder in nature and extraordinarily beautiful, but in recreation can be exceedingly dangerous. They are the cause of severe injuries and deaths when used as spontaneous springboards. As with all other bodies of water, they should be well researched and carefully navigated. Even the most experienced hikers can lose control and fall, and often this happens with a false sense of security by wearing ropes and safety harnesses, which do not always prevent such occurrences. Waterfalls and their basins should never be used as plunge pools for a variety of reasons, some of which include the sudden impact of cold water that can cause temporary paralysis and hypothermia, a debilitating injury from impact, broken bones from hitting rocks, being swept away by strong currents, and drowning.

Calamities and fatalities also happen when hikers venture too close to take photographs. Resist the urge to take that selfie at the top of a waterfall! It’s not worth the risk…you won’t be able to share or enjoy that image if you’re dead.

Oceans And Beaches

Oceans and seas share most of the same practicalities and precautions, but also have a whole other set of the precarious. With tides and waves and ever-changing currents, there are also drop-offs and mud flats, sandbars and breakwaters, seawalls and caverns. Then there are the very dangerous rip currents, also known as rip tides.

Even after reviewing the latest information about the beach and ocean you will be going to, always take some time to read any posted signs and flags.

A double red flag (red over red): Area is closed, no swimming.

Red flag: High hazard, rough conditions such as strong surf and/or currents are present. Swimming is strongly discouraged.

Yellow flag: Medium hazard. Moderate surf and/or currents. Inexperienced or weak swimmers are discouraged from entering the water. For others, extra care and caution should be exercised.

Purple flag: Dangerous marine life has been observed.

Green flag: Low hazard, calm conditions.

Black-and-white checkered flag: Set up along the beach, usually in pairs, to indicate separate sections to safely space swimmers and surfers in the water.

Dangerous Marine Life

Jellyfish cause injury and pain to more beach-goers than any other species of sea life. Their tentacles can be painful on contact even after the creature is dead. They are encountered both in the water, alive, and washed up on the shore. The most common types in North America are the Portuguese man-of-war and the sea nettle. Symptoms of a toxic sting include abdominal and/or chest pain, chills, headache, muscle spasms, numbness and weakness, limb pain, redness and swelling at the contact spot, rash, sweating, difficulty swallowing. A lifeguard, first responder, or 911 should be called immediately, but in the interim the sting can be rinsed with ocean water.

Sea urchins are spiny creatures related to starfish and sand dollars, often mistaken for rocks or shells. Their spines are a powerful defense mechanism and can cause extremely painful wounds. While their punctures and stings may cause an allergic reaction, most of the time the residual damage is limited to the discomfort. The spikes should be removed with care; soaking with vinegar beforehand is advised (if you have it, also good for jellyfish stings). If soaking does not loosen or dislodge them, try plucking with a pair of tweezers.

Kite-shaped stingrays are prevalent throughout North American oceans, often close to shore, and typically lie on the seabed covered by or blending with the sand. As they are not typically aggressive, most people are stung by accidentally stepping on them or getting too close. Their tails have barbs that contain a toxic venom. Stings from these creatures are treated in much the same way as those of jellyfish and sea urchins; soak the wound in sea water and remove the pieces. And, as with any stings incurred at the beach, seek the aid of a lifeguard or first aid provider as soon as possible. Some may recall that world-renown naturalist Steve Irwin was killed by the barb of a stingray that pierced his heart.

Sharks are, without a doubt, the most feared marine danger, and with good reason. Attacks while rare for the most part, can happen anywhere, even very close to shore. Contrary to popular belief, most sharks are not predatory of humans by nature, but often mistake human presence, mannerisms in the water, and apparatus (such as surfboards) as prey. The best practice to avoid becoming one of the statistics is to swim in groups, stay out of the water at dawn and dusk—when sharks are most active—and do not go in the water if you have a bleeding wound. What you’ve heard about a shark’s extraordinary ability to detect blood in the water is true; they can smell it from hundreds of meters away, at a ratio of somewhere between one part per 25 million and 10 billion parts water. If you think you see a shark, leave the water as quickly and calmly as you can and notify other beach-goers and a lifeguard.

Shells, while not considered marine life (unless they are housing a species of mollusks), can be every bit as hazardous if you step on them and cut your feet. Wounds should be promptly cleaned, treated with antiseptic, and dressed with a bandage or sterile gauze.

Sea turtles are not part of this dangerous marine life category but warrant a mention, as they are found on many beaches. It is illegal to harm or interfere with them, their nests, eggs, or hatchlings, so kindly steer clear. If any appear to be in distress, notify a lifeguard.

Red Tide And Algae Blooms

With climate change, these invasions are occurring with increasing frequency and toxicity to marine life, birds, plants, and even humans; the harvesting of fish and shellfish in affected areas causes sickness from handling and consumption. Harmful algae blooms (HABs) occur when algae—photosynthetic organisms that live in the sea and fresh water—grow uncontrollably. These events can last for weeks and are found in all U.S. waters. When checking the latest environmental conditions, if red tide or algae bloom is in effect, invariably beaches will be closed. But if you should happen to be strolling a shoreline during these conditions, by all means do not come in contact with water, ground, vegetation, or any creatures; take likewise care with your pets.

RIP CURRENTS/TIDES

These are widely misunderstood and all too often very much under respected for the extreme hazard they pose. To understand why they are so dangerous, even to the most expert swimmers and/or experienced surfers, you should learn what causes them and what they comprise of.

The tide actually has little to do with rip currents and, to debunk a common misconception, they do not pull you under but instead, pull you out beyond breaking waves. They are formed by a convergence of water surging to shore. The mass of water creates a channel back to the sea, forming a swift water stream that gushes away from shore at speeds of up to seven miles per hour or more than eight feet per second, which is faster than the speed of an Olympic swimmer. While a single rip current may be only tens of feet in width, there may be many of them spaced along the shore.

A rip current is made up of three parts: the feeder current, the neck, and the head. The feeder current runs parallel to the beach. If you’re in a feeder current, it will be imperative to take note of landmarks on the beach to maintain orientation; it is very possible you could quickly find yourself a hundred feet farther than your starting point. The neck starts at the front of the channel, which can even be in knee-deep water. You may be able to touch bottom but will feel the current pulling you out. If possible, walk/wade parallel to the beach, jumping forward with each wave. You may need to do this sideways to maintain your balance against the force of the waves, but keep moving until you’re out of the current. If you can’t touch the bottom or lose contact with it, try to float on your back. Remain as calm as possible and allow the neck to pull you out to the head where the current diminishes. When you’re in smoother waters, swim back to the beach at a 45-degree angle, going around the neck to avoid being pulled back in. At this point, the waves should ride you all the way back.

There are a number of myths about rip currents, and it’s important to know what is fact and what is not, as it could be the difference between escaping and drowning. As already mentioned, even the strongest swimmers cannot outswim a rip current. Assembling a human chain in a rescue effort is a bad idea and may very well pull multiple additional victims in. Contrary to what you might think, these currents do not come from bad weather; they can occur during any season, rain or shine, and in any depth of water. Appealingly moderate waves of two to three feet on sunny days can, in fact, generate especially strong rip currents. It is commonly believed that rip currents are visible and therefore easy to spot and avoid. This is not true and, in fact, rip currents can be difficult to identify. Some elements that indicate their presence include: a channel of churning or choppy water, an area of water that is noticeably different in coloration from the waters around it, a line of foam, bubbles, or debris moving steadily away from shore, and a break in the pattern of incoming waves.

Undertows are not the same as rip currents. Breaking waves on the beach rush in and are followed by a backwash of water and sand, the mixture of which is drawn into the next breaking wave. For waders and swimmer, this generates a feeling of being pulled down or, in deeper water, further underneath. Typically, an undertow is only dangerous to children or inexperienced swimmers, but is something to be aware of.

BEACH-RELATED ILLNESSES

Though signs and/or lifeguards will alert beachgoers of specific hazards or off-limit areas in the water and on shore, if you go somewhere private or a place that is not designated as a public beach, there may not be such warnings. Be sure to thoroughly scout the location, looking for exposed pipes or runoffs or sewage, injured or dead birds and/or fish and marine life, excessive amounts of debris, algae, and any foul smells.

As obvious as it might sound, avoid swallowing sea water; for one thing, the salt in sea water is greater than what can be safely processed by humans. Also, waterborne pathogens and chemicals from boat fuel and other pollutants can definitely make you sick. As previously stated, stay out of the water if you have open or healing wounds. Wash your hands after handling sand, which has been linked to the risk of gastrointestinal illnesses.

Wear sunscreen, selecting one with UVA and UVB protection of SPF 30 or higher, but also know that higher SPF is not necessarily better; choosing a broad-spectrum sunscreen is the key. Repeated applications should be done no less than every two hours, more often for sprays. Needless to say, if you are in and out of the water or sweating, it will need to be frequently reapplied. If at all possible, apply sunscreen thirty minutes before sun exposure to allow time to be well absorbed into the skin. For whole-body coverage, think of an amount the size of a golf ball. Make sure not to skip ears, feet, and the back of the neck. For added protection from the sun, apply an SPF 30 lip balm, wear head coverings (ideally a wide-brimmed hat), shield eyes with wraparound sunglasses with UV protection and, if you will be in the sun for prolonged periods, it’s a good idea to wear a dark, long-sleeved shirt or clothing rated for sun protection.

If sunburn occurs, cool down with a cool bath or shower. Apply a cold compress to affected areas. Drink plenty of water to rehydrate. Apply a moisturizer, perhaps hydrocortisone cream, but do not use products such as benzocaine, which may irritate the skin. Aspirin or ibuprofen can help relieve pain and reduce swelling.

For heat exhaustion, as previously mentioned, a person will feel sick, faint, fatigued, and sweat heavily. They should be directed to a cool place out of the sun and drink plenty of water. If recognized quickly and not too severe, they should feel better within thirty minutes or so.

Heat stroke is a much more serious condition, occurring when the body’s temperature spikes dangerously high. Children, the elderly, and individuals with chronic illnesses or disease are especially at risk. Symptoms include dizziness, dry skin, confusion, headache, thirst, nausea, hyperventilation, and cramping. Heat stroke should always be considered an emergency with first responder authorities being summoned. Before their arrival, the affected person should be sheltered, cooled in any way possible, and given water.

Finally And In Summary

In all water activity, stay liberally hydrated with water and/or beverages infused with electrolytes. While much-desired and enjoyed in the hot sun, ice-cold soda and beer, wine, lemonade, sweet tea, coffee and energy drinks are not good choices, some for their dehydrating effect, others for their sugar content.

Research your destination, familiar or not, ahead of time; maintain situational awareness of changing conditions; adhere to the rules of signs, guides, and lifeguards; make sure friends or family know your plans and timeline for return; use the buddy system; have adequate supplies, including a stocked first aid kit. Hydrate and stay hydrated!

Have fun but be safe!

Kim Martin, Survival Homes and Gardens magazine Editor-in-Chief, is co-author of the Jake Tyler thriller book series with Mykel Hawke.

martinandhawke.com