© Genealogical Society of Ireland – Digital Archive – March 2013

Genealogical Society of Ireland

Féil-Scríbhinn Liam Mhic Alasdair

Essays Presented to Liam Mac Alasdair, FGSI.

December 2009

Rory J. Stanley, FGSI Editor

Cumann Geinealais na hÉireann

2

© Genealogical Society of Ireland – Digital Archive – March 2013

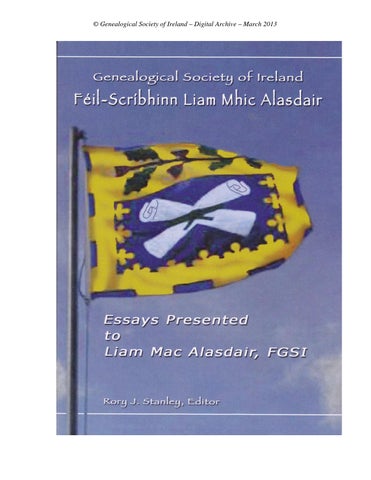

THE ARMS OF THE SOCIETY The arms, painted on vellum, were presented to the Society at an official ceremony held on July 23rd 2001 in the County Hall, Dún Laoghaire, Co. Dublin by the Chief Herald of Ireland, Brendan O’ Donoghue, who described the Arms as follows. ‘As much of the genealogist’s work involves the examination of documents of various kinds, two scrolls in saltire were selected as the principal charge, or element, in the GSI shield. The scrolls are banded vert, as green is the colour peculiarly associated with Ireland. The tinctures (or colours) azure and or, or in today’s language, blue and gold - the colours of the State - are used on the shield and there is also what the heralds describe as a bordure treffy which is reminiscent of shamrocks, another patently Irish symbol. Because the use of a tree as an emblem by genealogical societies is so common, an effort was made in this case to devise an appropriate variation. In the event, taking account of the fact that the late O Conor Don was closely associated with the Society, it was decided to include a sprig of oak on the shield as a reference to the O Conor arms. And beneath the shield, is the motto: Cuimhnigí ar ár Sinnsir (Remember Our Ancestors). In addition to the shield, the Society requested and has been granted a badge to be used by its members. The design here is a rope formed into a trefoil which, in heraldry, is known as a Hungerford knot. In this case, the rope terminates in two acorns. Finally, the letters patent include a banner (front cover) repeating the main elements of the shield. This is very much in keeping with the formula traditionally used in the grant of arms which states that the arms may be used on shield or banner.’ The Society’s heraldic badge is now called the ‘Mungovan Badge’. The work of devising the GSI arms was carried out by Micheál Ó Comáin, consultant herald at the office of the Chief Herald of Ireland after discussions with the Society’s officers, Rory Stanley, Frieda Carroll and, of course, Liam Mac Alasdair. The painting by hand of the arms and letters patent on vellum was done by Philip Mackey of Donegal, one of the herald-painters commissioned by the Chief Herald.

Contents page Introduction by the President

Rory J. Stanley

5

Eight Decades of Irish Genealogy

Tony McCarthy

9

The principles of international law governing the Sovereign authority for the creation and administration of Orders of Chivalry

Noel Cox

15

Marie Martin: An Irish Nurse in the First World War Philip Lecane

26

The Genealogies in the Irish manuscripts

Seán M. Mac Brádaigh

33

Will the Real Baron of Clonmore Please Stand Up!

Caroline McCall

40

The origins and chief locations of the O Gara sept

John Hamrock

50

Bringing back the memory

The O Morchoe

60

The name of our father

Michaël Merrigan and Katrijne Merrigan

64

Thomas St George MacCarthy

Jim Herlihy

70

The tragic incident of WW2―the Ballymanus mine explosion 1943

Róisín Lafferty

73

Polish-Irish connections are centuries old

Bartosz Kozłowski

80

The Gardiner Family, Dublin, and Mountjoy, County Tyrone

Seán J. Murphy

89

GSI Archive

Séamus O’Reilly

98

Is there a Case for Indigenous Ethnic Status in Ireland? Michael Merrigan

101

From Local District Defence Force Command Unit to Reserve Defence Force Infantry Battalion

James Scannell

116

St. Canice’s Cemetery, Barrack Lane, Finglas.

Barry O’Connor

123

Biographical Notes on the Contributors

144

Acknowledgements

151

Closing Message from An Cathaoirleach

Séamus Moriarty 3

152

4

Liam Mac Alasdair 2009

Introduction by Rory J. Stanley, FGSI President / Uachtarán

Genealogical Society of Ireland

Sláinte bhrea Mhic Alasdair or so the filí of old would have opened their praise poems to the great and good of Gaelic Ireland and it is, indeed, fitting to likewise open this Féil-Scríbhinn or Festschrift to our esteemed colleague and dear friend, Liam Mac Alasdair. When Liam and Maura Mac Alasdair attend the second Open Meeting of the Dún Laoghaire Genealogical Society back on May 14th 1991 in the Victor Hotel (now The Rochestown Lodge), nobody, least of all Liam himself, would have thought that an important chapter in the history of Irish genealogy had just opened. This chapter is one of service, innovation and facilitation and now spans nearly twenty years. The history of this Society from its foundation in October 1990 will, in time, be assessed according to its achievements and especially, its seminal role in the promotion and development of genealogical research. Never content to just replicate in an Irish context the activities and achievements of others, it constantly pushed the boundaries to open up genealogical research to the community at large. The promotion of genealogy as an open access educational leisure activity available to all in the community irrespective of status, socio-economic circumstances, prior learning or perceived ability was central to the development of the Society and it is an objective that Liam Mac Alasdair holds dearly. His deep interest in education predated his involvement in genealogy and in many ways it forms the bedrock of his commitment to his community and to this Society.

5

His experience as a long-time member of the Dún Laoghaire Borough Vocational Education Committee and its involvement in adult education, social improvement and facilitation is a deep well of knowledge, from which, this Society drew much of its inspiration and innovation. Nowhere is this more strikingly evident than in the Society’s publication programme over the past nineteen years or so. When Liam joined the Executive Committee of the Society at its meeting of June 7th 1991 he fully endorsed the report delivered to that meeting by Michael Merrigan, Hon. Secretary, on the necessity of establishing ‘an independent genealogical library and repository in Dún Laoghaire’ and stressed the need for the publication of a Journal. The meeting duly appointed Liam as the Society’s first Journal Editor and he set about the task of encouraging members to write their family histories. The first issue of the Society’s Journal was published by Liam on January 13th 1992 and presented to Members at the Open Meeting held that evening in the Victor Hotel and thus, started a journey in genealogical publishing that nurtured and launched many fine writers and researchers. Many later became authors of fine genealogical, biographical and historical works. Others went on to carve out careers in adult education or genealogical research owing much to the wonderful opportunity of having their first research or genealogical article published by Liam in the Society’s Journal. The production of the Society’s Journal, imbued with Liam’s education ethos, encouraged many Members to take up adult education and third level courses. Though Liam passed on the mantle of Journal Editor in 1999, he remained extremely committed to the publication of genealogical research data especially Memorial Inscriptions. The transcription of Memorials, like the earlier Census Project coordinated by Tony Daly, was one of the Society’s group projects which is still on-going under the direction of Barry O’Connor. Liam’s computer expertise was very generously made available to the Society as he painstakingly prepared the layout and typesetting of each of the Society’s publications. This first volume of the ‘Memorial Inscriptions of Deansgrange Cemetery’, for example, was published in August 1994 to be followed by a further four volumes between then and March 2002. In the meantime, Barry O’Connor and his team turned their attention to other cemeteries in the County of Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown and, once again, Liam was on hand to produce three volumes of the ‘Memorial Inscriptions of Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown’ between 2000 and 2005. The work continued thereafter with the ‘Memorial Inscriptions of Grangegorman Military Cemetery’ published in 2006 and, in keeping with developments in electronic publishing and in collaboration with 6

Barry O’Connor, Liam produced the Society’s first publication on CD Rom in September 2008 with the three volumes of the ‘Memorial Inscriptions of Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown’ on disc and fully searchable. This was followed in 2009 by the ‘Memorial Inscriptions of Military Personnel and Their Families’ on CD and all made available for purchase through an on-line shop created and maintained by Liam which is attached to the Society’s website. In addition to the Memorial Inscriptions, Liam’s skills were also instrumental in the publication of the GRO Users’ Groups proposal ‘The General Register Office Dublin – The Future? (1993); Godfrey F. Duffy’s ‘The Irish in Britain (1798-1916 – A Bibliography (1993); ‘An tEolaí – The Irish Family History Research Directory’ Vol. 1 (1993); ‘Dún Laoghaire Genealogical Society – Current Position and Future Aims’ (1994); Seán Magee’s ‘Weavers & Related Trades Dublin 1826 - A Genealogical Source’ (1995); the first volume of the Irish Genealogical Sources series (1995- ), the early volumes of ‘Wicklow Roots’ (1996-) on behalf of the Wicklow County Genealogical Society; the report of An Forum Oidhreachta – ‘Towards a County Heritage Policy’ (1997); and ‘Wavelink’ Vol. 1 No. 1 (2001) published on behalf of the Holyhead Dún Laoghaire Link Organisation by the Society. With his strong commitment to the development of the Society’s Archive and especially, as agreed back in June 1991, for the establishment of a permanent home for this growing facility, Liam warmly welcomed the March 1997 decision of Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council to allocate the Martello Tower at Seapoint to the Society as ‘a permanent base for its archive’. But it was nearly six years before enough funds were raised to commence the required restoration works on this historic tower which dates from 1804. Liam coordinated and directed the detailed planning that was required for the restoration works. Thankfully, many professionals within the Society and others gave of their services and advice free of charge enabling work to commence in 2003. Already in a ruinous condition with a rotten wooden floor and home to dozens of pigeons, work was going to be slow and meticulously undertaken in accordance with the specifications laid down for the protection of a heritage structure. His commitment to this enormous project was second to none and throughout the restoration works and the subsequent installation of the fixtures and fittings, especially the computers, Liam was on hand morning, noon and sometimes evening ensuring that the work was completed. The full story of the restoration of the Martello Tower at Seapoint was published by the Society in 2004 as no. 31 of the ‘Irish Genealogical Sources’ series and edited by Margaret Conroy, marking the official opening of the Society’s Archive or ‘Daonchartlann’ on September 15th 2004. However, it 7

soon became apparent that the atmospheric conditions within the building could not be adequately controlled to provide a sustainable environment suitable for the Society’s Archive. Corrective measures were considered but the ongoing funding requirements for such rendered it completely impossible for a voluntary organisation like this Society to undertake and we had to relocate the Archive to 111, Lower George’s Street, Dún Laoghaire in 2008. Thanks to Liam’s endeavours the County Council and the citizens of Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown have, in the restored Martello Tower, another heritage amenity which the County Council aims to allocate to more appropriate maritime uses at Seapoint. Liam strongly supported the change of name of the Society in 1999 to the Genealogical Society of Ireland as it more accurately reflected the activities of the Society and the interests of our Members. He was a member of the Select Committee which met with the officials at the office of the Chief Herald of Ireland to discuss the design of the Society’s coat-of-arms. Liam, it is believed, suggested the crossed scrolls and the Motto in Irish – ‘Cuimhnigí ar Ár Sinnsir’ (‘Remember Our Ancestors’). These Arms and the beautiful Heraldic Banner depicted on the front cover of this Festschrift were presented to the Society by the Chief Herald of Ireland, Brendan O’Donoghue, at an official ceremony held on July 23rd 2001 in the County Hall, Dún Laoghaire. Liam stepped down from the Board of the Genealogical Society of Ireland in March 2008 after serving as an officer of the Society since June 1991. In that time he has been a source of knowledge, advice and encouragement for many Members. His quiet unassuming manner has often masked a steely resolve to get things done – and that he did in abundance. Given his long commitment and enormous personal contribution to the development of genealogy in Ireland, including a wonderfully enduring legacy of publishing genealogical, biographical and now heraldic research with over forty titles in print, it is only fitting that Liam Mac Alasdair be presented with a Festschrift in his honour. On my own behalf, having first met Liam and his lovely Maura in 1995 and during my terms as Cathaoirleach from 1996 to 2008, I discovered and came to rely on the wisdom and strength of a hard working colleague and true friend, Liam Mac Alasdair. In conclusion, Liam, ní mόr dúinn mar sin an leabhar seo do thairiscint duit le dea-thoil agus le beannachtaí ό gach éinne againn. Iarramuid ort an FhéilScríbhinn seo do ghlacadh uainn mar chomharta ar ár m-buíochas agus ár nárdmheas. Is mise, do shean chara, Rory 8

EIGHT DECADES OF IRISH GENEALOGY Tony McCarthy When Liam MacAlasdair was born eighty years ago, most of us had no ancestors! At least, this was the view of the foremost Irish genealogist of the day. In his book A Simple Guide to Irish Genealogy, Fr Wallace Clare says of the Registry of Deeds: ‘Not only do the deeds supply information relating to the wealthy landlords, but also concerning those of humble circumstances, such as the descendants of the Irish gentry who either took to trade or farming after the Battle of the Boyne’. Now, if the descendants of the Irish gentry barely registered on the genealogical scale, small farmers, cottiers and landless labourers, from whom the bulk of the Irish people are descended, had to be beyond detection. However, later in the book Fr Clare finds a role in genealogy for the ‘Irish peasant’, not as someone with an interest in tracing his ancestry, but as a genealogical source: ‘The Irish peasant simply lives in the past, and consequently knows all about individuals who have resided in the neighbourhood during the past hundred years or more and takes special delight in imparting information concerning them’. Father Clare had helped to set up the Irish Genealogical Research Society (IGRS) in the mid-1930s. It was to be ‘a Society exclusively devoted to Irish Genealogy … which would have a wide appeal to those of Irish descent throughout the world’. However, it was also exclusive in another sense: the annual membership fee was two guineas, roughly the equivalent of a working man’s weekly wage. Rule 6 of the IGRS stated that: ‘Members under the age of 21 and all Law and Medical students…shall be admitted without entrance fee…’ Today, we are all acknowledged to have ancestors, and we do not need to join an exclusive club to access the means of researching them. We can carry out significant research from the comfort of our own homes using CD-Roms and the Internet. This transformation in genealogy is related to big changes in technology and bigger changes in society; factors such as a better standard of education, more leisure time, greater disposable income and a genuine acceptance of the fact that we are all equal. However, like any other facet of our culture, genealogy did not change simply because of social trends. It took the hard work of individuals and organisations to popularise genealogy and to provide the tools to enable people to pursue it.

9

Liam Mac Alasdair, working within the Genealogical Society of Ireland (GSI), is a man who helped to bring Irish genealogy into the modern world. It is fitting that the GSI should honour his long life of hard work by compiling this celebratory publication. As a former President of the Society, I am delighted to have been asked to contribute an article. In compliance with this request, I will briefly review some of the main developments in Irish genealogy over the eight decades of Liam’s life (to date!). The 1920s witnessed the establishment of an independent Ireland and the destruction of most of our national records. The blame for the explosion and fire in the Four Courts must be shouldered equally by the Pro- and Anti-Treaty forces. The Irregular forces who occupied the Four Courts in mid-April 1922, turned the huge Record Treasury in which most of our national records were stored, into a bomb factory. In June 1922, the Free State forces decided to dislodge the occupiers. They borrowed field guns from the British and bombarded the complex of building, setting it ablaze. Two huge bombs that had been manufactured and stored in the Record Treasury exploded. A contemporary report stated that: ‘Debris was showered far around and charred documents of national records were picked up in the streets a mile away.’ Indeed the violence of the explosion was such that documents were later found on the Hill of Howth, a distance of seven miles. This loss of heritage is sorely felt by every Irish family history researcher. The 1821, 1831, 1841 and 1851 censuses were stored in the Public Record Office in 1922. The Irish census of 1821 was the first modern census to record personal details: up to 1841, the British counterpart recorded only statistical information. Those records contained the names of every man woman and child who lived in Ireland during those four decades. Had they survived, the census returns alone would get us off to a flying start. Those of 1821 would bring our ancestry back to the eighteenth century with ease. Commenting on the destruction, Winston Churchill said: ‘better a state without documents than documents without a state.’ I wonder? On a positive note, the 1920s saw the establishment of the Irish Manuscripts Commission in 1928. Its foundation was the Free State Government’s attempt to mitigate the impact of the destruction at the Four Courts in which it had played a significant part. The Commission sought out manuscript collections in private hands, records such as estate papers, cataloguing and publishing some of them. Since 1930 it has overseen the publication of over 140 titles. It also published the journal Analecta Hibernica, which provided information on the Commission's work and in which editions of shorter manuscripts were reproduced

10

Rebuilding and salvaging genealogical resources continued during the 1930s. Despite what has already been said about Fr Wallace Clare and the Irish Genealogical Research Society, it has to be admitted that he and the organisation he helped to found played a very important role in Irish genealogy. Reading back-issues of their annual publication The Irish Genealogist, which has been reissued in CD-Rom by Eneclann, one is alternately impressed and irritated. In the first issue, there are some excellent articles that are still of value today; for example: King Henry VII’s Irish Army List’;‘Notes on an Old Irish Newspaper’; ‘Abstracts of Irish Wills’. On the other hand, the following sentence appears in the editorial of the same issue: ‘It is, therefore, the happiest of auguries that the Irish Genealogical Research Society should set forth on its career under the presidency of the Earl of Ossory, who, as we all know, is the elder son of the present Marquess (and 22nd Earl) of Ormonde, the head of that illustrious House of Butler…’ For decades after, each issue contains excellent articles and is imbued with references to class and title. Perhaps the IGRS was taking its lead from the Office of Arms in Dublin, which despite the establishment of the Free State, was still very much a British institution. Sir Neville Wilkinson, a British appointee, was in charge there under the ancient title of Ulster King of Arms. When Sir Neville died in 1940, de Valera took the opportunity to Hibernicise the office. From 1943 it became known as the Genealogical Office, and its head was given the title Chief Herald of Ireland. However, it was de Valera’s appointee to the renamed office, Edward Mac Lysaght, which made the 1940s a significant decade for Irish genealogy. Ironically, Edward Mac Lysaght started out in life almost as English as Sir Neville. He was born near Bristol and, though his father was Irish, he could not have had a more British upbringing. He attended an English public school: Rugby, and went on to study law at Oxford. He might have gone on to a successful career as a barrister or solicitor in England − and joined the IGRS as Sir Edward − but for the fact that, after sustaining a serious injury, he came to Lahinch, County Clare to recuperate and fell in love with the country, eventually relocating to County Clare. He became fluent in Irish and played a part in the War of Independence. As Chief Herald, a position he retained until 1954, Edward Mac Lysaght gave a more egalitarian and Gaelic quality to the old British institution. Despite his title, he had very little interest in heraldry. His lasting legacy to Irish genealogy is contained in his books Irish Families and More Irish Families. These very accessible histories of Irish surnames are still popular and in print today. They continue to spark an interest in Irish genealogy which often leads on to serious family history research. He also introduced the innovation of giving courtesy 11

recognition to Irish chiefs of the name. Unfortunately, the MacCarthy Mór controversy has brought this area into disrepute in recent times, but in its day, courtesy recognition put the descendants of the old Irish aristocracy on a par with their continental counterparts. The 1950s was a lean time for genealogy. It is chiefly remembered for the activities of Eoin ‘the Pope’ O’Mahony (1904-1970). His unusual nickname derived from the answer he gave to a question from one of his teachers when he was a primary school pupil: ‘what do you want to be when you grow up?’ In 1955 he organised the first O’Mahony Clan Gathering in the ancient seat of the O Mahonys at Gurranes, Templemartin, County Cork. Later, he founded the still thriving O’Mahony Society. His radio programme Meet the Clans brought him and family history to national prominence. This long running show, which spanned the fifties and sixties, gave him an opportunity to display his encyclopaedic knowledge of Irish families. One commentator remarked: ‘No other mortal brain could house the formidable assemblage of genealogical data that his did…’ The Pope O’Mahony was a larger than life character whose enthusiasm for genealogy and love of the Gaelic past was infectious. The 1960s was a quiet time for genealogy. A few new books of interest to family tree enthusiasts came on the market. The Ulster Historical Foundation, which had been set up in the mid-50s as a research agency attached to the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), began to publish source books, many on gravestone inscription. Of these it can be said that though the subject matter was rather tedious, at least the source was not confined to the upper echelons of society. Margaret Dickson Falley’s book Irish and ScotchIrish Ancestral Research was published in 1962. Of this two volume work, reviewers are usually agreed on two things: it contains a mass of invaluable information; it is virtually unreadable. Ms Falley did not organise her material in a reader-friendly way. She was in dire need of a good editor. Fortunately for the Falley-weary genealogist, the 1970s began with the publication of the very readable Handbook of Irish Genealogy by the Heraldic Artists. For the first time, a ‘how to’ book recognised that genealogy was for everyone. Perhaps that is why it became so popular it had to be reprinted eight times in the twenty years that followed. The Handbook was a very useful work that gave many people a start in genealogy. Its chief drawback was the sample research case given for illustrative purposes. It gave the impression that compiling a family tree back to the seventeenth century was a simple matter, and that every ancestor would be found in all the various types of records. With no network of societies in existence where research experiences could be shared, it was the lot of each reader of the Handbook to find out by one disappointment after another that Irish records just aren’t that good. 12

A number of circumstances in the 1980s gave birth to the Irish Genealogical Project (IGP) which has played a significant, often negative, role in Irish genealogy ever since. The 1980s was a decade of high unemployment. To alleviate this situation, various government training schemes were put in place to equip young unemployed people with skills which might enable them to get work. Computer training was an essential part of most of those schemes. It was suggested that trainees should key in church register entries as part of their keyboard skills training, thus producing a valuable by-product. The practice started in a number of localities and eventually developed into a plan to digitise, for the whole country, all church records, the 1901 and 1911 censuses, Griffith’s Valuation, tithe applotment books and civil birth, death and marriage entries. The plan was to make computerised databases of this information to facilitate genealogical research. It was a marvellous idea that could have taken much of the tedium out of research: for instance, no more trawling through endless rolls of microfilm to find baptismal entries. However, it turned out to be a huge disappointment. The crux of the matter was that facilitating genealogical research was not the objective of the IGP; its objective was making money. The amount of money expected to be generated, directly and indirectly was ambitious to say the least: in the late 1980s, one IGP appointed consultancy estimated that genealogy related tourism coming to Ireland in the mid-1990s would bring in £183,000,000 annually. The main problem with the IGP, was the lack of strong central control by a person with a keen interest and detailed knowledge of genealogy and genealogists. Right up to the present time, no national database has been compiled by the IGP. Each county retains its county records. Descendants of Irish emigrants will come to Ireland to visit the old homestead, provided they can find it. Irish-Americans have little chance of finding their homestead without the aid of a national database, because in most cases they do not know from which county their ancestor came. By holding onto their own records, county-based genealogical centres are facilitating neither genealogists nor themselves. All county databases should be amalgamated, indexed, and put on the internet to be researched free of charge. This would be a nice gesture to the descendants of Irish emigrants. It would also make more money for each country by encouraging tourism. More importantly, it would enhance Ireland’s reputation: the present practice of doling out of little bits of ancestral information for inflated prices is doing us no favours. The 1990s was the most productive decade for Irish genealogy. There were more societies founded, more books and magazines published, more 13

conferences organised, more family gatherings, more research facilities, and more of everything genealogical than all the earlier decades put together. After the great flowering of the 1990s, there was a step back during this opening decade of the third Millennium. Disappointingly, the Irish Genealogical Congress came to an end after four excellent international gatherings; some quality journals, such as The Irish at Home and Abroad, ceased publication; courtesy recognition has been withdrawn from the Chiefs of the Name; finance to the National Library and National Archives has been cut back. However, when we look over the whole period of eighty years, it is clear that genealogy is in an immeasurably improved state now compared to what it was in the 1920s. The Genealogical Society of Ireland is emblematic of the changes for the better. It is open to all; facilitates local members with both morning and evening meetings; it facilitates members who live abroad with an internet presence and with monthly and annual publications. Liam Mac Alasdair and people of like mind, who enjoy genealogy and the scope it gives them to exercise their many and varied skills, deserve our thanks for helping to bring about this revolution.

14

THE PRINCIPLES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW GOVERNING THE SOVEREIGN AUTHORITY FOR THE CREATION AND ADMINISTRATION OF ORDERS OF CHIVALRY Noel Cox I

Introduction

The International Commission for Orders of Chivalry was established at the Vth Congress of Genealogy and Heraldry at its meeting in Stockholm in August 1960, in order to look into the legitimacy of pretended Orders of chivalry. These Orders had proliferated, especially after the Second World War. The Commission reported to the VIth International Congress of Genealogy, held at Edinburgh in September 1962.1 A provisional list of authentic Orders was published in 1963, and the Register itself in 1976. In its Report, the Commission outlined what it had concluded were the principles involved in assessing the validity of Orders of chivalry. These principles were accepted by the VIth International Congress of Genealogy. In addition, it was agreed that the International Commission, composed of “high personalities of the Congress, and leading experts in the field of chivalry, nobiliary and heraldic law”,2 should become a permanent body charged with applying the principles developed in its report.3 The Commission published a new edition of the Register in 1996. This does not however differ materially from earlier editions,4 and is governed by the original principles, said to have been derived from international law. The sources of international law include written and unwritten rules, treaties, agreements, and customary law, the latter being discoverable in the writings of jurists and academics upon the behaviour of states, for states were for long the dominant – if not sole – participants in international diplomacy and law. The principles which the International Commission identified were that only states have the right to create Orders of chivalry; that these Orders cannot be abolished by republican governments, that exiled Sovereigns retain control of royal Orders, that no private individuals can create Orders, that no state or 1

International Commission for Orders of Chivalry, Register of Orders of Chivalry – Report of the International Commission for Orders of Chivalry (1978), 3. 2 One must be perpetually vigilant against claims as to the legitimacy of new “Orders of Chivalry” based on the opinions of supposed legal experts. 3 International Commission for Orders of Chivalry, Register of Orders of Chivalry – Report of the International Commission for Orders of Chivalry (1978), 3. 4 i.e. ibid. 15

supranational organisation without its own Orders can validate Orders, and that the only sovereign Order is the Order of Malta. Since 1962 these principles have been followed by the Commission. They have also been generally, though not universally, accepted by heraldists and by others. But it is more than doubtful whether they were ever legally correct, at least in their entirety. This chapter will examine the second and third principles, which would appear to suggest that the right to control honours is inalienably attached to the person of the Sovereign who instituted them, and such a right of control is unassailable by a successor government. Such a conclusion might be correct in canon law, but it is not so in international law, nor in the domestic law of most, if not all, countries. II

Ulta vires to abolish Orders

The second principle states that: The Dynastic (or Family or House) Orders belonging jure sanguinis to a Sovereign House (that is to those ruling or ex-ruling Houses whose sovereign rank was internationally recognised at the time of the Congress of Vienna in 1814 or later) retain their full historical chivalric, nobiliary and social validity, notwithstanding all political changes. It is therefore considered ultra vires of any republican State to interfere, by legislation or administrative practice, with the Princely Dynastic Family or House Orders. That they may not be officially recognised by the new government does not affect their traditional validity or their accepted status in international heraldic, chivalric and nobiliary circles.5 Several difficulties are immediately apparent. The first of these is with the nomenclature; what is meant by “Dynastic (or Family or House) Orders”? A distinction between dynastic Orders and state Orders is virtually unknown in the common law world,6 and would appear to be only applicable where there is a legal distinction between the state and the legal person of the Sovereign.7 The British approach is to be distinguished from that of most continental European countries, which have Roman law-based civil law legal systems. Archbishop 5

Ibid, 4. Though it was adopted in 1995 in the Prime Minister’s Honours Advisory Committee, The New Zealand Royal Honours System: Report of the Prime Minister’s Honours Advisory Committee (1995). 7 The Crown is the substitute for the state in realms; see Noel Cox, “The Theory of Sovereignty and the Importance of the Crown in the Realms of The Queen”, 2(2) Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal (2002): 237-255, 237. 6

16

Hyginus Eugene Cardinale has given what may be called the classic civil law definition of dynastic Orders: Dynastic Orders of Knighthood are a category of Orders belonging to the heraldic patrimony of a dynasty, often held by ancient right. They are sometimes called Family Orders, in that they are strictly related to a Royal Family or House. They differ from the early military and religious Orders and from the later Orders of Merit belonging to a particular State, having been instituted to reward personal services rendered to a dynasty or an ancient Family of princely rank.8 Thus, in this tradition the dynastic Orders are linked to the royal family, in contrast to the state Orders, which are linked to the state. The absence of a British concept of the state is, of course, is not a coincidence.9 In the British usage at least, a more meaningful distinction is between the great Orders of Christendom (such as the Golden Fleece and the Garter), the domestic, house or family Orders,10 and the (generally modern) Orders of merit.11 The Order of St Patrick, a dynastic Order in terms of the Commission’s principles, could potentially be transformed from dynastic Order to state Order, if revived by the government of the Irish republic, as some has advocated.12 This raises significant questions, not least of which is the existence of the right to preserve or to institute a new branch of the original Order, in both the United Kingdom and Ireland. This can be seen as equivalent to the division of the Order of Christ between the Holy See, Portugal and Brazil. The Commission’s own principles 8

Hyginus Eugene Cardinale, Orders of Knighthood Awards and the Holy See – A historical, juridical and practical Compendium (1983), 119. Although his work was subsequently criticised for the many errors which it contained, none of these are of relevance to the present chapter. 9 Frederic Maitland, “The Crown as a Corporation”, 17 Law Quarterly Review (1901): 131; Adams v Naylor [1946] AC 543, 555 (HL); David Cohen, “Thinking about the State: law reform and the Crown in Canada”, 24 Osgoode Hall Law Journal (1986): 379-404; Verreault v Attorney-General of Quebec [1977] 1 SCR 41, 47; Attorney-General of Quebec v Labrecque [1980] 2 SCR 1057, 1082 [Supreme Court of Canada]. 10 Such as the Royal Family Order, bestowed on female members of the Royal Family. 11 All others, such as the Order of the British Empire. 12 The Most Illustrious Order, established 1783 by King George III as King of Great Britain and Ireland, became obsolescent after the creation of the Irish Free State. Though the King was, in the 1922 Constitution, part of Parliament, “All powers of government and all authority, legislative, executive, and judicial, in Ireland are derived from the people of Ireland, and the same shall be exercised in the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) through the organisations established by or under, and in accord with, this Constitution” (Article 12). Thereafter it was difficult, if not impossible, for new appointments to be made to the Order. The last appointment was that of HRH Prince Henry Duke of Gloucester in 1934. The Order became obsolete with the death of the last knight (also the Duke of Gloucester) in 1974. 17

would appear to invalidate any revival of the Order of St Patrick by the Irish state, and it must be doubted whether this can be correct. Whilst the existence of such a thing as a dynastic Order in British law is uncertain, the principle continues with what can only be called an extraordinary contention. The claim that these Orders “belonging jure sanguinis to a Sovereign House ... retain their full historical chivalric, nobiliary and social validity, notwithstanding all political changes” is a far reaching assertion of the divine right of kings.13 Three general schools of thought on the subject have emerged.14 Many proponents of the concept of fons honorum or right to confer honours and create Orders will agree that an ex-monarch or the head of a former royal house is limited in the exercise of his regalian rights by the royal constitution which was in effect at the time of his abdication. This position has much to commend it, and appears to have been generally accepted.15 However, others insist that the privileges of fons honorum can only apply to a monarch who has actually reigned and not to the head of a former royal house who has not. Whilst a Sovereign will lose legitimacy as head of state once the new regime is established, there is no doubt that the fons honorum remains with the Sovereign and their lawful successors, subject to alteration or abolition by the new national authorities;16 assuming for the moment that the latter is legal. The third position, and most restricted, holds that the fons honorum disappears when monarchy ceases to be the form of government. This has simplicity, but little else to commend it.17 Even if one accepts that a Sovereign probably retains fons honorum even if exiled, the question becomes one of how long this will last, and what conditions (if any) it is subject to. Arguably, in the case of the Order of St Patrick, the King had ceased to be the Head of State, by 1949 at the latest, and was therefore selflimited; the revival, or even the continuation, of the Order by the King after 1943 (and possibly as early as 1922), was inappropriate, or at least politically difficult. Whether the new state could revive the Order, or take it over, was another vexed question. 13

JN Figgis, The theory of the Divine Right of Kings (1914). James Algrant, “The Fons Honorum”, formerly obtainable from <http://www.kwtelecom.com/heraldry/>. 15 Ibid. 16 Thus unless a new Grand Master is appointed, any royal grand master remains in office. 17 James Algrant, “The Fons Honorum”, formerly obtainable from <http://www.kwtelecom.com/heraldry/>. 14

18

The Constitution of the Irish Free State remained silent on the question of the royal prerogative, which was not transferred to the government of the State, but which probably preserved the royal prerogative in the hands of the King while he retained a constitutional role in the State. The royal prerogative was thus unaffected by the advent of the Irish Free State – at least until 1937 (or rather 1936), and the effective creation of an Irish republic, but it remained associated with the Crown. In the case of Byrne v Ireland18 the Supreme Court of Ireland categorically established that the Irish Republic did not inherit the royal prerogative.19 It was apparently excluded – indeed this occurred in 1922,20 rather than in 1937, or in 1949, when Ireland became officially as well as effectively a republic. However the power of the state to do revive the Order of St Patrick, or to create a new Order of merit, may exist independently of the prerogative. It is apparently not limited by Article 40.2.1 of Bunreacht na hÉireann, which prohibited the conferring of titles of nobility but not necessarily an Order of Merit.21 The Irish Government has expressed its intention to establish an Order of merit, which it may do under principle one of the Commission’s guidelines,22 though this is unlikely to include titles.23 The revival of the Order in Ireland, or the creation of a new Order of merit, would have to be by legislative means.

18 19

[1972] IR 241 [Supreme Court of Ireland].

Supported by Webb v Ireland [1988] IR 353 and Geoghegan v Institute of Chartered Accountants [1995] 3 IR 86. 20 The Constitution of Saorstát Éireann 1922. 21 However, “Article 40.2 does not appear to have ever been judicially considered”; John Kelly, “The Irish Constitution (2nd ed), 467. 22 “Every independent State has the right to create its own Orders or Decorations and lay down, at will, their particular rules. But it must be made clear that only the higher degrees of these modern State Orders can be deemed of knightly rank, provided that they are conferred by the Crown or by the ‘pro tempore’ ruler of some traditional State”. 23 The use of titular honours by those for whom permission has been granted to receive such foreign honours has also been controversial, as is the use of Irish chiefly titles. Some of the latter, like the O’Conor Don, were accorded an element of “courtesy recognition” by the Crown prior to 1943. Afterwards 15 were recognised by Edward MacLysaght, Chief Herald of Ireland and Genealogical Officer, Office of Arms 1944-45, and another 7 were recognised 1989-95, including the McCarthy Mor (later rejected), O’Doherty, O’Rourke, O’Carroll and MacDonnell. Recognition by the Crown seems to have survived even after 1943, with MajorGeneral David Nial Creagh, the O’Morchoe, a senior officer of the British Army, being commonly accorded recognition (though in the London Gazette he is described as David Nial Creagh O’Morchoe, in the Army List he was given as “O’Morchoe”). The Irish state presumably has the legal authority to recognise these titles (assuming they are recognised as chiefly or territorial titles and not titles of nobility), but the legal authority for the Genealogical Office to recognise Gaelic chiefly titles has been challenged; see the AttorneyGeneral’s advice to the Minister of Arts, Sport and Tourism in June 2002. 19

One of the first principles of Commonwealth constitutional law holds that sovereignty, that is the absolute right to command obedience, rests with Parliament.24 This principle of parliamentary supremacy, which is by no means unknown in European and other legal traditions, is completely at odds with a contention that it is “ultra vires of any republican State to interfere, by legislation or administrative practice, with the Princely Dynastic Family or House Orders”.25 Any property or legal right belonging jure sanguinis (by right of blood) to any individual can be alienated, either by action of the competent legislative authority,26 or (to a lesser extent) by action of the possessor.27 It is to be very much doubted that any Order is unalienable, and for the Commission to assert that it is “ultra vires of any republican State to interfere, by legislation or administrative practice, with the Princely Dynastic Family or House Orders” is not only unrealistic, but does not reflect the legal position.28 It is not true even in civil law that “[n]o authority can deprive [exiled Sovereigns and their heirs] of the right to confer honours, since this prerogative belongs to them as a lawful personal property iure sanguinis (by right of blood), and both its possession and exercise are inviolable”.29 Any property may be sequestrated, seized or abolished by legitimate authority – provided that this is done in accordance with the proper legal procedures. Nor must an abdicating Sovereign explicitly renounce his right to the grand mastership of an Order, it being clear that on abdication a Sovereign renounces all offices, titles and other attributes of sovereignty.30

24

See, for example, Sir Henry Wade, “The Legal Basis of Sovereignty”, Cambridge Law Journal (1955): 172. 25 International Commission for Orders of Chivalry, Register of Orders of Chivalry – Report of the International Commission for Orders of Chivalry (1978), 4. 26 Countess of Shrewsbury’s Case (1612) 12 Co Rep 106; 77 ER 1369; R v Purbeck (Viscount) (1678) Show Parl Cas 1, 5; 1 ER 1, 5; Report as to the Dignity of a Peer of the Realm (1820, 1829 Reprint), vol I p 393. 27 Once conferred, a peerage cannot in English law be renounced, although an heir, upon succeeding to a peerage, may now renounce the dignity for his lifetime, under the Peerage Act 1963 (UK). Scottish law allowed however the surrender of a peerage. 28 With the exception of natural, or divine law, any human law is amenable to change by competent political authority; generally, see Noel Cox, Church and State in the Post-Colonial Era: The Anglican Church and the Constitution in New Zealand (2008), especially 66. 29 Hyginus Eugene Cardinale, Orders of Knighthood Awards and the Holy See – A historical, juridical and practical Compendium (1983), 119. 30 This was clearly illustrated by the case of King Edward VIII. He retained, however, those offices not held as a consequence of kingship, including his military ranks. 20

The term Grand Master encompasses rather more in Continental usage than in British practice. A Sovereign is not always grand master in either tradition, and the appointment may be given to another member of the Royal Family, or even a commoner. However, the right to control an Order belongs to a Sovereign as Sovereign of an Order, rather than as Grand Master, and this status cannot survive voluntary abdication. The position of the Sovereign of an Order of chivalry, being an incorporeal hereditament or heritage, is a right in rem maintainable against anyone within the jurisdiction of creation.31 However, rights in rem, and in particular incorporeal right in rem, only exist within the legal system which created them32 and which usually protects and enforces the right. Once a right is removed from the legal system that conferred it, it ceases to have any validity under the law of the creator state.33 Once out of the jurisdiction in which an Order was created, the rights conferred by the statutes of the Order are unenforceable, unless the country to which it is taken is prepared to recognise the rights in rem created by the statutes, under the host country’s rules of private international laws.34 These rights are determined by the lex creatus,35 the law of the country of origin, rather than that of the lex situs,36 the country in which the Sovereign may now reside. Orders of chivalry are governed by the appropriate lex creatus. Claims to Orders and the rights they confer must be directed to the granting jurisdiction where the claim will be decided by the lex creatus.37 Unless the Order is 31

Sir Crispin Agnew of Lochnaw, “The Conflict of heraldic laws”, Juridical Review (1988): 61, 62-63; See GC Cheshire and PM North, Private International Law PM North ed (1979), 658; Salvesen v Administrator of Austrian Property [1927] AC 641. 32 “The characteristic of a legal right is its recognition by a legal system” in GW Paton and DP Denham (eds), Jurisprudence (1972), 284 et seq. 33 Sir Thomas Innes of Learney, Scots heraldry (1978), 8. 34 Sir Crispin Agnew of Lochnaw, “The Conflict of heraldic laws”, Juridical Review (1988): 61, 63. 35 Thus claims to Scottish peerages and baronetcies, and probably creations of Great Britain and the United Kingdom with Scottish designations, are considered in Lyon Court or before the Committee of Privileges in terms of Scots Law; Sir Crispin Agnew of Lochnaw, “Peerage and Baronetcy Claims in the Lyon Court” (n.d.); Dunbar of Kilconzie, 1986 SLT 463; Lady Ruthven of Freeland, Petitioner, 1977 SLT (Lyon Court), 2; Grant of Grant, Petitioner, 1950 SLT (Lyon Court); Sir Crispin Agnew of Lochnaw, “The Conflict of heraldic laws”, Juridical Review (1988): 61, 63. 36 See ch XVI “The Law of Immoveables” in GC Cheshire and PM North, Private International Law PM North, ed (1979); ch 17 “Immoveable Property” in AE Anton, Private International Law: A treatise from the standpoint of Scots law (1967). 37 Sir Crispin Agnew of Lochnaw, “The Conflict of heraldic laws”, Juridical Review (1988), 61, 63. 21

recognised by another state, the purported abolition must be accepted as valid. Archbishop Cardinale recognised the limitations on exiled Sovereigns when he acknowledged that “they cannot however found new Dynastic Orders”.38 But he didn’t carry this to its logical conclusion. They cannot create new Orders because the lex creatus is no longer in their hands. The only general exception is if the Order has become an independent legal person in international law, a status only enjoyed by the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.39 Any papal recognition would of course confer some legitimacy upon the Order, in so far as canon law was concerned, though this would not as such make it an Order of chivalry.40 Archbishop Cardinale identified the crux of the position however, when he wrote that “[t]his is especially true when the Orders in question have been solemnly recognised by the Supreme Authority of the Holy See. No political authority has the right to suppress this recognition, declared by highly official documents, such as Papal Bulls by a merely unilateral act of abolition. So long as the recognition is not revoked by the Holy See itself, the Order cannot be considered canonically extinct”.41 So far as canon law is concerned, the Order of chivalry remains in existence. But canon law does not overrule the municipal laws of states. Thus, whatever the position of the Papacy, any successor authority may abolish or suppress any Order of chivalry, dynastic or otherwise. According to international practice, the Holy See recognises legitimately instituted Orders of knighthood as juridical persons under public law in the various states.42 An Order still recognised by the papacy has canonical validity, even if it lacks validity in domestic law. But if it lacks validity in domestic law it will lack validity in international law also.43 38

Hyginus Eugene Cardinale, Orders of Knighthood Awards and the Holy See – A historical, juridical and practical Compendium (1983), 119. 39 Recognised by the Holy See 1113; Regesta Pontificum Romanorum P Jaffé, S Loewenfeld, F Kaltenbrunner and P Ewald eds (1956), 6341; Noel Cox, “The Continuing question of sovereignty and the Sovereign Military Order of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta”, 13, Australian International Law Journal (2006): 211-232. 40 Were the legitimacy of an Order, as an Order of Chivalry, to be recognised, then difficulties would exist for subject of The Queen, who may not accept foreign honours without Her Majesty’s permission. 41 Hyginus Eugene Cardinale, Orders of Knighthood Awards and the Holy See – A historical, juridical and practical Compendium (1983), 119. 42 Ibid 26. 43 It may have validity in the secular law of the papal states (now Vatican City State), and this would be sufficient to give it some validity in international law if it lacks validity in the locus creatus. But the Sovereign of such an Order would owe their authority to this recognition, and not to the laws of their own country. It is doubtful that the secular law of the Vatican City 22

There are several Catholic dynastic Orders of knighthood which are still being bestowed by a legitimate successor of a Sovereign in exile. Among these, the two most important are the Most Noble Order of the Golden Fleece (Austrian branch) and the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of St George of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.44 Others still bestowed, though with doubtful authority since they were suppressed by the successor authorities of the countries concerned, include the Order of the Holy Annunciation and the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, both of Italy. The Order of St Patrick remains in legal existence since its authority is derived from the Crown of the Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and is now the property of the Crown of the United Kingdom, as successor in law.45 III

Jure sanguinis and fons honorum

The third principle states that: It is generally admitted by jurists that such ex-Sovereigns who have not abdicated have positions different from that of pretenders and that in their lifetime they retain their full rights as fons honorum in respect of those Orders of which they remain Grand Masters which would be classed, otherwise, as State and Merit Orders.46 There are also some unusual aspects to this principle. Firstly, a Sovereign has control of an Order whether or not they are Grand Master, as the latter is merely an officer of the Order. Secondly, this is an assertion that an exiled Sovereign remains de facto if not de jure Sovereign for life. The question of loss of de facto and de jure authority has been the subject of numerous studies, and no one

State, as distinct from the canon law of the Catholic Church, has accorded any Order recognition. 44 Hyginus Eugene Cardinale, Orders of Knighthood Awards and the Holy See – A historical, juridical and practical Compendium (1983), 140. 45 Though the Crown of Ireland was distinct from the Crown of Great Britain, at least pre1800 (and the Order was established 1783), it is likely that the latter has the legal control of the Order, despite the reasoning applied in Calvin’s Case (1607) 7 Co Rep 156 16a; 77 ER 377, 396. The unity of the Crown was the prevailing concept; Noel Cox, “The Dichotomy of Legal Theory and Political Reality: The Honours Prerogative and Imperial Unity”, 14 Australian Journal of Law and Society (1998-99): 15-42. See also Noel Cox, “The British Peerage: The Legal Standing of the Peerage and Baronetage in the Overseas Realms of the Crown with Particular Reference to New Zealand”, 17(4) New Zealand Universities Law Review (1997): 379-401. 46 International Commission for Orders of Chivalry, Register of Orders of Chivalry – Report of the International Commission for Orders of Chivalry (1996), 4. 23

definitive position can be asserted.47 Whilst it is possible that an exiled Sovereign may retain de facto authority, this is by no means certain in every case. Referring to principle two, this means that whilst the Sovereign may retain the right to appoint to any prior existing Orders, that right is subject to termination by the proper successor authority. IV

Conclusion

What conclusions can be drawn from a brief examination of some of the principles under which the International Commission for Orders of Chivalry has operated for nearly fifty years? Firstly, every sovereign prince (or, subject to their respective constitutions, the president or other official in a republican state) has the right to confer honours, in accordance with the constitutional framework of the state. These honours should be accorded appropriate recognition in all other countries under the usual rules of private international law. Secondly, an exiled Sovereign retains the right to bestow honours, dynastic, state or whatever else they may be styled. This right extends to their lawful successors in title, even for several generations. Appointments may continue to be made, unless this has been expressly prohibited by the successor authorities of the state, or the Order has become obsolete. It also follows that an exiled, or former Sovereign may continue to make appointments to an Order which is also governed by the new regime, thus creating a separate, though related, Order. Whilst an exiled Sovereign may in some circumstances establish a new Order of chivalry, he or she may only do so whilst they remain generally recognised by the international community as the de jure ruler of his country. His or her successors will not have this right to create new Orders, excepting in those rare instances where the son or further issue of an exiled Sovereign has been generally recognised by the international community as the rightful ruler of their country. Only de jure Sovereigns (including their republican equivalents) may create Orders of chivalry. Thirdly, the international status of an Order of chivalry depends upon the municipal law of the country in which it was created. There can be no international Orders as such, shorn of dependence upon the municipal laws of a 47

See for example, FM Brookfield, “Some aspects of the Necessity Principle in Constitutional Law” unpublished University of Oxford DPhil thesis (1972); Jonathan Waskan, “De facto legitimacy and popular will”, 24(1) Social Theory and Practice (1988): 25-55. 24

state.48 Principles four, five and six together indicate that sovereign Orders are not generally possible, with recognition however being extended to the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.49 The Order of Malta depends upon its own unique history, and, at least in part, its recognition by the Holy See and by secular princes. Any pretended “sovereign” Order is nothing more than a voluntary society or association, and members should not wear any insignia or use any styles or titles to which they may be entitled outside the private functions of such groups.

48

Thus, the “Sovereign Order of Saint Stanislaus” created 9 June 1979 by Count Juliusz Nowina Sokolnicki, President of the Republic of Poland (in exile), is not, and never could have been, sovereign, irrespective of the regularity of Sokolnicki’s own status as titular President. 49 Noel Cox, “The Continuing question of sovereignty and the Sovereign Military Order of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta”, 13, Australian International Law Journal (2006): 211232.

25

MARIE MARTIN: AN IRISH NURSE IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR Philip Lecane Room 10, Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, Drogheda, County Louth. 27 January 1975. In the small hours of the winter morning Sister Michael Farrell transferred Mother Mary from her chair to her bed. She then gently brushed the old woman’s hair. Mother Mary took Sister Michael’s right hand in both of hers and kissed it. ‘Thank you dear’ she said. Then she closed her eyes and went to sleep. Sister Michael remained on duty at the bedside. At 2.40 a.m. Mother Mary showed signs of restlessness. Sister Michael put her hand on Mother Mary’s arm and asked if she was alright. Did she want anything? Mother Mary opened her eyes, looked at her, smiled and peacefully passed away. At the time of her death, there were four hundred and fifty sisters in the religious order founded by Mother Mary Martin. Today the Medical Missionaries of Mary are drawn from eighteen different nationalities and work in sixteen countries. Mother Mary had brought much healing, comfort and love to the world in the years since she had been born Marie Martin in 1892. **************** On 25 April 1892, Marie was the second of eleven children born to Tom and Mary Martin of Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire), Co. Dublin. The Martins were a prosperous Catholic family, as Tom Martin was a partner in the firm of T&C Martin, Timber Merchants. At the time of the older children’s births, the family lived in Glencar, a substantial red-brick house still standing on Marlborough Road, Glenageary, County Dublin. The family later moved to Mount town House on Lower Mount town Road, Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire). They finally settled in Greenbank, on Carrickbrennan Road, Monkstown. As the Martins do not appear on the 1901 census for the house, the family must have moved to Greenbank sometime after April 1901. The house stood on five acres. It had flower, fruit and vegetable gardens, a rockery, green lawns, tennis courts, a summer-house and a bamboo plantation. There were trees, a paddock, cowsheds and an acre or more of rough unused ground, with two ponds. A gardener and under-gardener were employed. The family’s idyllic life was shattered on St. Patrick’s Day 1907. A gunshot rang through the house. Tom Martin was found lying dead on the floor, a revolver in his hand. A local doctor said that the death could not have been other than accidental. Whatever the reason for Tom’s death, his wife Mary, 26

pregnant with their twelfth child, had to carry on, supported by relatives from her own and her husband’s families. The 1911 census shows Mary Martin as head of the household. Marie and five of her brothers were in the house on the night of the census, as were Marie Ernst, a governess from Bavaria and five female servants. The summer of 1914 saw the Martin family still living at Greenbank. In the meantime Marie had been educated, with her two first cousins, at a finishing school in Bonn, Germany. Upon the outbreak of war, Marie’s older brother Tommy joined the Connaught Rangers and her younger Charlie, the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. In 1910 the War Office had introduced a volunteer system to supplement army medical structures. Volunteers were drawn from the British Red Cross Society and the St. John Ambulance Brigade. They served in units called Voluntary Aid Detachments (V.A.D.s) The V.A.D.s supplied auxiliary nurses, ambulance drivers and stretcher-bearers. Two-thirds of the volunteers were female. V.A.D. was used as a collective term for the detachments and VAD as a singular term for those serving in the detachments. Having completed a year’s course in First Aid, Hygiene and Home Nursery, with the St. John Ambulance Brigade, Marie applied to serve as a VAD. She was interviewed by a selection board in early 1914. She received three months training in the Richmond Hospital, Dublin, following which she was certified as VAD nurse. (Her younger sister Ethel and her aunt, Lily Moore, later joined the VADs.) Assigned to ‘A’ Company, 5th Battalion Connaught Rangers, Marie’s older brother Tommy landed at Anzac Cove, Gallipoli on 6 August 1915. The Connaught Rangers were part of a contingent from the 10th (Irish) Division sent to reinforce the Australian and New Zealand troops who had been fighting at Anzac Cove since 25 April. On 8 August, two days after landing, Tommy was slightly wounded at Lone Pine. Two days later he was again wounded at Aghyl Dere and was subsequently evacuated. He was shipped home to Ireland, where he was hospitalised on Bere Island, Co. Cork. In the meantime Charlie Martin, with the rank of Lieutenant, was posted to 6th Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers, 10th (Irish) Division. On 7 August 1915, the battalion was put ashore at ‘C’ Beach, Suvla Bay, a few miles north of Anzac Cove, where Tommy’s battalion had landed the day before. On 9 August, the 6th Dublins took part in an attack on Chocolate Hill. Charlie was wounded during the attack. His wounds, however, were not as severe as Tommy’s, as he was not shipped home.

27

Shortly after her brothers had sailed for Gallipoli Marie was called up for service with the VADs at Malta. Her mother accompanied her to London, where they spent a week together before Marie joined the hospital ship Oxfordshire. On 22 October 1915 the ship reached Valetta harbour in Malta. As it arrived a day earlier than expected, the VADs’ postings hadn’t been finalised. The nurses explored Valetta and, according to Marie, “had tea and deadly cakes.” The next day she was assigned to a converted barracks on a peninsula overlooking St. George’s Bay on the northern shore of the island. The hospital treated the wounded and the sick from the Gallipoli campaign. In the summer of 1915 the sick included those suffering from dysentery and enteric fever. As the number of soldiers with these illnesses decreased with the onset of winter, they were replaced by those with trench-fever and frost-bite. Marie wrote to her mother on 28 October: “the work is really hard, but of course it is what we came out for.” Her free time was spent on sleep or writing letters for very ill patients. When a patient died, Marie would write to his mother with information about his final days. October brought mosquitoes and sand flies that left Marie’s face in a terrible state and her eyes swollen. Days were hot and airless. But by December it had become cold, and the VADs, going between the wards housed in various parts of the barracks, were drenched in pouring rain. The yearly salary for a VAD was twenty pounds, as well as board and uniform. Marie was very excited when she got her first ever pay packet. She sent a registered letter to her mother with one pound and five shillings saying: “I wish I could only earn more to make things easier for you.” On 26 November she wrote to Tommy who was now convalescing on Bere Island County Cork and who, on 20 September, had been promoted to Captain. She asked if there was “any sign of this terrible war ending?” Meanwhile, in late September 1915, with Bulgaria preparing to join Germany and Austo-Hungary in an attack on Serbia, the 10th (Irish) Division was ordered to leave Gallipoli and a move to Salonika in the Macedonian province of Greece. Following fighting on 8 December 1915, Captain Charles Martin, 6th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers was recorded as missing. On 18 December Marie wrote to her mother saying that one of a newly arrived group of patients told her he had seen Charlie about two weeks earlier and he had been well. Marie said she would make enquiries to see if any of Charlie’s battalion was among the wounded on the island. On 27 December she received a cable from her mother saying the War Office had notified her that Charlie had been wounded and was missing. Deeply distraught, Marie redoubled her efforts in search of news of her younger brother. On 29 December, with a heavy heart,

28

she wrote home saying that she could not find any news in Malta of Charlie’s whereabouts. Over the next few weeks Marie spoke with a number of soldiers. Each told her that he believed Charlie had been captured. An officer told her that Charlie had been slightly wounded in the arm on 6 December. In March a soldier told Marie he had seen Charlie being wounded in the leg on 8 December, following which the Bulgarians had captured Charlie’s trench and the men in it. In April a man from Charlie’s company told Marie that Charlie had been giving orders on the parapet of a trench when he was badly wounded through the shoulder. Following orders to withdraw, Charlie had accompanied his men for fifteen miles when they retreated. Then he and about thirty others were captured by the Bulgarians. Marie’s six-month contact was ending. She left Malta on Holy Thursday, which fell on 20 April 1916. The journey home, including several days spent in London, took two weeks. By the time she reached home the Easter Rising had taken place and been suppressed. After barely a month at home Marie was called up again. Now aged twentyfour, she was on her way to France. Before boarding the early morning boat train at London’s Charing Cross Station, she dropped a postcard to her mother in the mailbox. The Mail Boat to Boulogne was very crowded. Marie and the four young women with her sat on their luggage all the way. When the ship docked in France they had lunch at the Boulogne Tower Hotel before setting off again. By 7.30 p.m. Marie had arrived at the costal town of Hardelot In 1900 Hardelot, with its long sandy beaches, had been established as a seaside resort by Sir John Whitley, an Englishman who owned the local Chateau. Edwardian families spent their summer holidays in spacious villas in the forests around Hardelot. The Chateau became a clubhouse for golfers. Other holidaymakers enjoyed sailing, tennis and cricket. French families also bought property at the resort. Among them was Louis Blériot, who pioneered sand yachting on the wide flat beach – a sport that remains popular in Hardelot to this day. On 25 July 1909 Blériot became the first man to fly the English Channel, a feat that earned him the Daily Mail prize of £1000, awarded by the owner, Dublin born Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe. In Hardelot Marie was assigned to No. 25 General Hospital, located in what had previously been the Aviation Hotel. Marie described the building as “rather quaint.” Apart from the wards within the former hotel, the wounded were also treated in several large tents. Upon arrival Marie was given a brief visit to the surgical ward where she would take up duty the next day. Then she was shown 29

to a “sweet villa” where she was billeted. She would share a room with Miss Paul, a VAD with whom she had become friends while serving in Malta. June 18 was Marie’s first day on duty. Despite being tired, she sat up in bed that night writing to her mother. “I’ll give you three clues so you can puzzle out where we are: (1) The opposite of soft. (2) The fifth letter of the alphabet. (3) The man in the bible whose wife was turned into a pillar of salt.” Either because it was presumed that the Germans couldn’t possible decipher the clues, or because the person censoring Marie’s letter was kind-hearted, the letter was allowed through! On 21 June Marie wrote home again. She asked if there was “any news of poor Charlie.” As Marie wrote home that day, she could distinctly hear the gunfire from the Front, even though it was nearly one hundred kilometres east of Hardelot. Sister Makenzie, in charge of Marie’s ward, did not like VAD nurses. Fully trained State Registered Nurses (SRNs) tended to look down on VADs with their short emergency training. Marie received a letter from the mother of her boyfriend Gerald Gartland, saying that he had been recalled to the trenches. This caused Marie much anxiety. However, a half-day off duty gave her the opportunity to take a tram to Boulogne, about 10 miles away. There she was able to walk and have tea. She shared her thoughts in a letter to her widowed mother. Meanwhile, patients were being evacuated from the hospital to make way for anticipated casualties from a forthcoming battle. Marie asked her mother to send some plug tobacco for the men. On 24 June, seven days of shelling of German positions began, in preparation for a major assault. The attack began on 1 July 1916. It resulted in the British Army’s greatest ever number of casualties in a single day. Casualties were treated in First Aid Dressing stations in farmhouse basements near the front, and then transported to hospital by rail and ambulance. On 2 July the hospital at Hardelot had filled up by 5 p.m. Marie spent extra time on duty helping Sister Makenzie who, she could see, was new to military ways. Then a letter brought confirmation of what Marie had long feared. The War Office had informed her mother that Captain Charles Martin 6th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers was dead. Trying to cope with her own grief, Marie’s letter home that night tried to comfort her mother. “It is really impossible to realise that we shall never see his dear face again. How we shall all miss him!” In Malta Miss Paul had spent off-duty time accompanying Marie while she made enquiries about Charlie. Now she was on hand to support her Marie when the dreadful news had finally arrived. On 8 July Marie wrote home saying that it was a relief that Charlie had died without much suffering. The soldiers she was nursing “had such nasty wounds.” 30

Marie was now nursing men who, in addition to their original wounds, had developed gas-gangrene. This is a condition where open wounds are infected by bacteria that cause extremely painful swelling. The condition sometimes requires amputation and, if not treated quickly and carefully, can have fatal consequences. Around this time Marie received another letter from home, telling her that her boyfriend Gerald Gartland had been wounded. A short time later she received a wire telling her that he was alright and was going back to the trenches. He then wrote saying that he had only been slightly wounded, but had had a bad time in France. Her mother sent the requested tobacco, which Marie said she would keep for her “Paddys.” Convoys of wounded men continued to arrive at Hardelot. Marie was transferred from the surgical ward to the medical section, in the tented wards of the hospital. She told her mother that the tents were very nice in the sunshine, but were awful when the rains came. On 13 July she found herself on a committee of Nursing Staff and VADs who were planning a tea party for the 180 orderlies at Hardelot. She spent her day off buying the necessary provisions. Towards the end of July things slackened off for a short time at Hardelot. The tents were closed for a while, as a recent epidemic of diarrhoea was being investigated. Marie had come to know Dorothy Whitley, whose father had established the resort at Hardelot. Miss Whitley used to come to the hospital with flowers from her garden at Pré Catelan. When off-duty Marie sometimes walked through the woods to visit this lovely house that reminded her of home. By 13 August the tents were filling up with soldiers suffering from the effects of gas poisoning. For four days Marie nursed fifty-six men on stretchers, with only a single orderly to help. Then Miss Paul was sent to help her. The Medical Officer with whom Marie was working had specialised in the treatment of gas poisoning. So Marie learned a lot from him. At the end of August it began to rain. It was “beastly in the tents and so nasty for the men.” The nurses got so wet walking between the tents that Marie asked her mother to send her a sou’wester and boots. It was under these conditions that the 16th (Irish) Division went into action. In the first ten days of September the Division lost 240 of its 435 officers, and 4,090 of its 10,410 other ranks in attacks on Guillemont and Ginchy. As winter approached, Marie began to suffer very painful chilblains on her hands, shins and feet. She had bought an oil stove in Boulogne to heat the room she shared with Miss Paul. By boiling two pots of water on the stove, she could manage to get a warm bath. With “terrible gales and raindrops the size of eggs,” everyone wondered if the hospital would be kept open in such an exposed place. On 8 November Marie told the Matron that she would not be renewing her contract when her six-month term was up. She

31

had 39 days left. She began crossing them off on her calendar, looking forward more and more to getting home. Early in December, the tents were finally closed. On 8 December Marie got the chaplain to say Mass for Charlie on the first anniversary of his death. Hearing that Gerald Gartland was expected in Boulogne, Marie set out by tram to find him there, but failed to do so. Disappointed, she returned to Hardelot, telling herself that somehow it was God’s will. In early 1917 she returned home. Marie Martin’s war was over. By the time she was twenty-five she had made up her mind that marriage was not for her and she told Gerald of her decision. As Mother Mary, she went on to found the Medical Missioners of Mary nursing order. After recovering from his wounds, Tommy Martin subsequently served in Salonika, Palestine, France and Belgium. He attained the rank of Major. After the war he worked in T. & C. Martin. Charlie Martin’s body was never found. Captain Charles Andrew Martin, 6th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers was twenty years old. Awarded the Serbian Order of the White Eagle 5th Class, he is commemorated on The Doiran Memorial to the missing, which stands near Doiran Military Cemetery in northern Greece. Sources: I am very grateful to Sister Isabelle Smyth of the Medical Missionaries of Mary for information on Marie Martin and her family and for copies of her articles on Marie’s wartime service. My thanks are also due to Oliver Fallon, Secretary of the Connaught Rangers Association and Tom Burke, M.B.E., Chairperson of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association. Purcell, Mary, To Africa with Love: The Biography of Mother Mary Martin (Dublin, 1987). Smyth, Sister Isabelle, MMM and the Malta Connection in Healing and Development, Yearbook of the Medical Missionaries of Mary, 2002 edition. Smyth, Sister Isabelle, MMM and the French Connection in Healing and Development, Yearbook of the Medical Missionaries of Mary, 2003 edition. Taggart, Sister M. Anastasia and Smyth, Sister Isabelle, The Medical Missionaries of Mary in Drogheda 1939-1999 (Drogheda, 1999). 1911 Census of Kingstown, Co. Dublin.

32