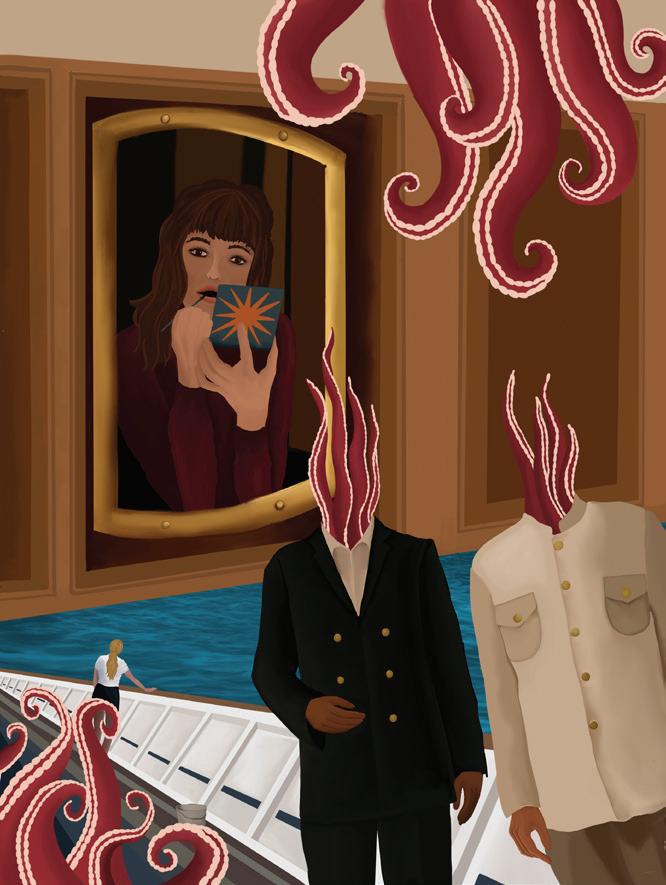

TRIANGLE OF SADNESS IS A PARABLE ABOUT BEAUTY AND EXCESS

EDUCATOR EXODUS: INSIDE D.C.’S TEACHER TURNOVER CRISIS

By Sarah Craig

OCTOBER 21, 2022

AS D.C. NEARS SUFFRAGE FOR UNDOCUMENTED IMMIGRANTS, ACTIVISTS HOPE FOR PROPER FOLLOW-THROUGH By Graham Krewinghaus

By Chetan Dokku

editorials

D.C.’s new migrant services bill is antiimmigrant and dangerous

EDITORIAL BOARD

5 newsAs D.C. nears suffrage for undocumented immigrants, activists hope for proper followthrough

GRAHAM KREWINGHAUS

6voices

I’m a ‘Type 1 diabetic,’ not a ‘person with Type 1 diabetes’: Rejecting person-first language

MARGARET HARTIGAN

7 newsLack of university support undercuts LGBTQ+ Resource Center during “OUTober”

JUPITER HUANG

"Teachers have to have their cups filled to be able to pour into our students. There's no conflict between educator wellness and student wellness—they require each other."

halftime leisure

Warping the mirror: Five haunting literary monsters LUCY COOK

contact us editor@georgetownvoice.com Leavey 424 Box 571066 Georgetown University 3700 O St. NW Washington, DC 20057

features

Educator exodus: Inside D.C.’s teacher turnover crisis

SARAH CRAIG

news Georgetown Explained: Georgetown’s application process

YIHAN DENG

on the cover

halftime sports

All my friends are NFL head coaches

SAM LYNCH, BRADSHAW CATE, TIM TAN

Editor-In-Chief Max Zhang

Managing Editor Annabella Hoge

internal resources

Executive Editor for Resources, Diversity, and Inclusion

Andrea Ho

Editor for Sexual Violence Coverage Paul James Service Chair Devyn Alexander Social Chair Sarah Watson news

Executive Editor Jupiter Huang Features Editor Margaret Hartigan News Editor Nora Scully

Assistant News Editors Anthony Bonavita, Joanna Li, Franziska Wild opinion

Executive Editor Sarah Craig Voices Editor Kulsum Gulamhusein

Assistant Voices Editors Ella Bruno, Lou Jacquin, Aminah Malik

Editorial Board Chair Annette Hasnas

Editorial Board William Hammond, Annabella Hoge, Jupiter Huang, Paul James, Allison O'Donnell, Sarah Watson, Alec Weiker, Max Zhang leisure

Executive Editor Lucy Cook Leisure Editor Chetan Dokku

Assistant Editors Pierson Cohen, Maya Kominsky, Isabel Shepherd Halftime Editor Adora Adeyemi

Assistant Halftime Editors Ajani Jones, Francesca Theofilou, Hailey Wharram sports

Executive Editor Carlos Rueda Sports Editor Tim Tan

leisure

Triangle of Sadness is a parable about beauty and excess CHETAN DOKKU

Assistant Editors Andrew Arnold, Thomas Fischbeck, Nicholas Riccio

Halftime Editor Lucie Peyrebrune

Assistant Halftime Editors Jo Stephens design

Executive Editor Connor Martin Spread Editors Dane Tedder, Graham Krewinghaus

Cover Editor Sabrina Shaffer

Assistant Design Editors Alex Giorno, Cecilia Cassidy, Deborah Han, Ryan Samway copy

halftime leisure

The definitive Arctic Monkeys guide in preparation for The Car

ANNETTE HASNAS

Copy Chief Maanasi Chintamani

Assistant Copy Editors Devyn Alexander, Donovan Barnes, Jenn Guo

multimedia

Podcast Editor Jillian Seitz

Assistant Podcast Editor Alexes Merritt Photo Editor Jina Zhao online Website Editor Tyler Salensky

Assistant Website Editor Drew Lent Social Media Editor Allison DeRose business

General Manager Megan O’Malley

leisure

Demi Lovato’s return to the stage will leave you saying “Holy Fvck” MAYA KOMINSKY

Assistant Manager of Accounts & Sales Akshadha Lagisetti

Assistant Manager of Alumni & Outreach Gokul Sivakumar

support

Contributing Editors Sophie Tafazzoli

The opinions expressed in The Georgetown Voice do not necessarily represent the views of the administration, faculty, or students of Georgetown University, unless specifically stated. Columns, advertisements, cartoons, and opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the views of the Editorial Board or the General Board of The Georgetown Voice. The university subscribes to the principle of responsible freedom of expression of its student editors. All materials copyright

The Georgetown Voice, unless otherwise indicated.

Staff Contributors Nathan Barber, Nicholas Budler, Romita Chattaraj, Leon Chung, Elin Choe, Erin Ducharme, James Garrow, Christine Ji, Julia Kelly, Lily Kissinger, Ashley Kulberg, Olivia Li, David McDaniels, Amelia Myre, Anna Sofia Neil, Grace Nuri, Natalia Porras, Owen Posnett, Omar Rahim, Brett Rauch, Caroline Samoluk, Michelle Serban, Amelia Shotwell, Isabelle Stratta, Amelia Wanamaker

2 THE GEORGETOWN VOICE Contents

October 21, 2022 Volume 55 | Issue 5 4

8

10

11

12

13

15

design by madeleine ott

“octopi”

SABRINA SHAFFER

14

PG. 9

HAPPY HALLOWEEN

What to do during Halloweekend:

GOSSIP RAT

An eclectic collection of jokes, puns, doodles, playlists, and news clips from the collective mind of the Voice staff.

→ SPOOKY SEASON

Boo! —the Voice

Did you ever have someone kiss you in a clammy sewer?

I have. Or I used to. But now I lie awake in vermin and disease, in sweat and in heat. I stare at ICC walls until they speak back. I twist in my burrow and pray that I’m not—right this minute—about to make some fateful relationship mistake. If this is what love feels like, I don’t want it.

If I have to wallow in my pain, so do all of you. I’m very proud to announce my latest studio album, Midday This is a collection of shrieks made in the middle of the day, a journey through Leo’s and frat houses. The floors I pace and the humans I face. For all of us who have swagged and slayed and decided to keep the rat loins lit and go searching—hoping that just maybe, when Healy strikes noon, we’ll smash on Vittles’ shelves.

Meet me at Midday—and say goodbye to your Marriage Pact lovers.

xoxo,

Gossip Rat

until

get a

→ GRAHAM'S CROSSWORD

Across

Study location from which one might come back a changed person

Frankenstein's workplace

Noblest gas (abbr.)

opposite

U.S.'s biggest shopping center

First ever to have a lightbulb moment

Slogan of a presidential hopeful who once told his audience to “please clap”

Down

Uncrustables flavor (abbr.)

What a wizard ponders upon

Is candy corn good?

engine's excited

→ KULSUM'S PUMPKIN AND ANNIE'S ANGRY GHOST

3OCTOBER 21, 2022 Page 3

crossword

by graham

krewinghaus; "i c thru u"

by

dane tedder; pumpkin

by kulsum gulamhusein; angry ghost by annabella hoge

1. Ginuwine hit 5.

7.

8.

9. Off

10.

11.

13.

1.

2.

3.

4. Search

logo 5. House plant with soothing innards 6. Title of a p. 10 interview subject 10. Georgetown's spookiest school 12. “In other words” in letters →

1. Go out in only your underwear and say you’re a swimmer 2. Knock on your neighbor's door, screaming "WHERE’S MY CANDY ?????" >:-) 3. Homework 4. Eat a soft pretzel (what happened to them?) 5. Cast a spell 6. Fall in love 7. Sleep with your peanut butter toast 8. Carve a pumpkin 9. Scare your friends! 10. Dress up as a Jesuit and ride a golf cart

→

→ MERCH HAUL Support the Voice by getting some official Voice merch! Orders are open

Oct. 30; everyone is welcome to

sweatshirt, a cap, a tote bag, and/or some stickers. Scan the QR code to purchase:

D.C.’s new migrant services bill is anti-immigrant and dangerous

BY THE EDITORIAL BOARD

I

I

f D.C. is to call itself a sanctuary city, its government must take bold steps to actually protect its immigrants.

Municipal responses to migrant busing have been woefully inadequate, locking some of the District’s most vulnerable residents out of guaranteed access to legal support, employment and education trainings, fixed shelter, medical care, and food provision. It also endangers the ability of many immigrants—including those who are long-term D.C. residents—to access D.C.’s services for homelessness entirely. The D.C. Council must adopt legislation correcting these failures.

Since the spring, thousands of immigrants have been bussed to Northern “sanctuary cities” from the southern border by Republican governors, a ploy to inflame national tensions about migration. Used as political pawns, some 10,000 immigrants, mostly asylum seekers awaiting immigration court dates, have been bussed to D.C. alone from Texas and Arizona.

The actual execution of bussing has been uncoordinated and inhumane; receiving cities are rarely notified in advance of immigrant arrivals, complicating the resettlement process. Doubts have been raised about whether this bussing is even consensual: D.C. Attorney General Karl Racine told the press on Oct. 14 he was investigating whether Southern states misled migrants.

Bussing calculus aside, the receiving sanctuary cities—D.C., chiefly—have failed to protect immigrants in the center of this maelstrom, providing little municipal support as immigrants attempt to get settled. D.C. must take responsibility and provide sanctuary for the asylum seekers within its borders.

Mayor Bowser and D.C. City Council’s response thus far has been to declare a public health emergency and establish the Office of Migrant Services (OMS) through temporary legislation on Sept. 20. Under the Migrant Services and Supports Emergency Amendment Act of 2022, the OMS will provide “time-limited” services to recent immigrants to the United States that include food, clothing, temporary shelter, and medical and relocation services. Eligibility for OMS services is unilaterally determined by the mayor; the bill provides no clear definition of what “recent” entails.

The emergency bill is riddled with antiimmigrant policies. Notably, Title II of the bill amends the Homeless Services Reform Act (HRSA) of 2005 to define

THE GEORGETOWN VOICE

THE GEORGETOWN VOICE

individuals with active immigration proceedings as temporary nonresidents of D.C. As Councilwoman Brooke Pinto noted in a failed proposed amendment, people with active immigration cases—which can last years due to immigration court backlog—are rendered ineligible for services for people experiencing homelessness under HRSA. These provisions affect nearly all asylum seekers and countless other immigrants.

Immigrants who do not fall into the category of “recent” lack guaranteed access to OMS services—meaning they may go unprotected entirely. Either way, the new bill gatekeeps critical services for vulnerable people—many of whom lack permanent housing arrangements by virtue of their immigration status. This may become life-threatening as hypothermia risk mounts in the coming months.

The bifurcation of immigrants and “legitimate” residents by city political leaders is dangerous: If immigrants are considered temporary visitors, merely passing through, why bother with cost-heavy policy solutions? The result of this outlook is an unwillingness to establish effective legislation that can facilitate meaningful immigrant settlement. Immigrants are thus regarded as short-term burdens, a hassle to the government’s grander concerns. There’s no reason, either, why immigrants shouldn’t be sent elsewhere rather than be settled here.

The new bill also specifically harms immigrant families. Rather than being accommodated in family shelter systems, migrant families have been placed in hotels retrofitted for COVID-19 quarantine purposes, in which they’ve experienced discriminatory treatment from security and stringent movement restrictions. As a result, volunteer organizations have had to manage many familial cases themselves, directing funding to move these migrants into more traditional shelter programs and to rehabilitate stable family dynamics.

Additionally, the bill permits congregate shelter settings for recent migrants, raising concerns about the safety of children in these environments. Legally, all other families experiencing homelessness must be housed in private rooms; why are migrant families any less deserving of this right?

D.C.’s resettlement efforts have also been stymied by declined requests for National Guard assistance; Bowser cannot herself order a deployment because D.C. lacks statehood. Though National Guard presence further militarizes

immigrant resettlement, it at least constitutes leveraging of federal resources.

While the city response crystallizes, a net of mutual aid organizations and volunteer groups have rushed to pick up the slack left by municipal neglect. These groups have offered vital shelter, medical care, food, community, and more. Informed by theories of reciprocal community care and solidarity, mutual aid organizers like Sanctuary DMV are still actively fundraising and accepting volunteers to support their operations. As D.C. residents, Georgetown community members should plug into these initiatives, as well as mount resistance to the ongoing anti-immigrant framework. Immigrants are integral members of Georgetown’s student body, staff, and faculty. Protecting immigrants new and old in D.C. is imperative.

D.C. needs to take funding immigrant resettlement more seriously. The $10 million allocated for the District’s plan seems insignificant when held relative to the whole D.C. budget. A look at D.C.’s economic stance in previous fiscal years reveals the city is underfunding immigrant settlement efforts with nearly 600 million dollars in surplus budget. Such surplus finances should be put towards the city’s most pressing issues—namely, the current migration disservice.

Amidst resettlement turmoil, policymakers need to institutionalize policies that ensure all immigrants can access quality District services. Only then can we go beyond basic necessities and instead be geared toward longterm integration in society, such as providing child care, healthcare, public transportation, and education.

With D.C.’s migrant services falling woefully short, minor changes aren’t enough; D.C. needs to shift its entire approach. Though the idea that migrants are societal burdens begins with border state bussing policies, D.C.’s insistence on treating immigrants as short-term residents en route to other cities clearly reinforces that perception. All immigrants deserve to be treated as human beings, not political pawns; D.C. should walk the walk of supporting immigrants and provide them with real, effective, and longterm assistance. G

EDITORIALS

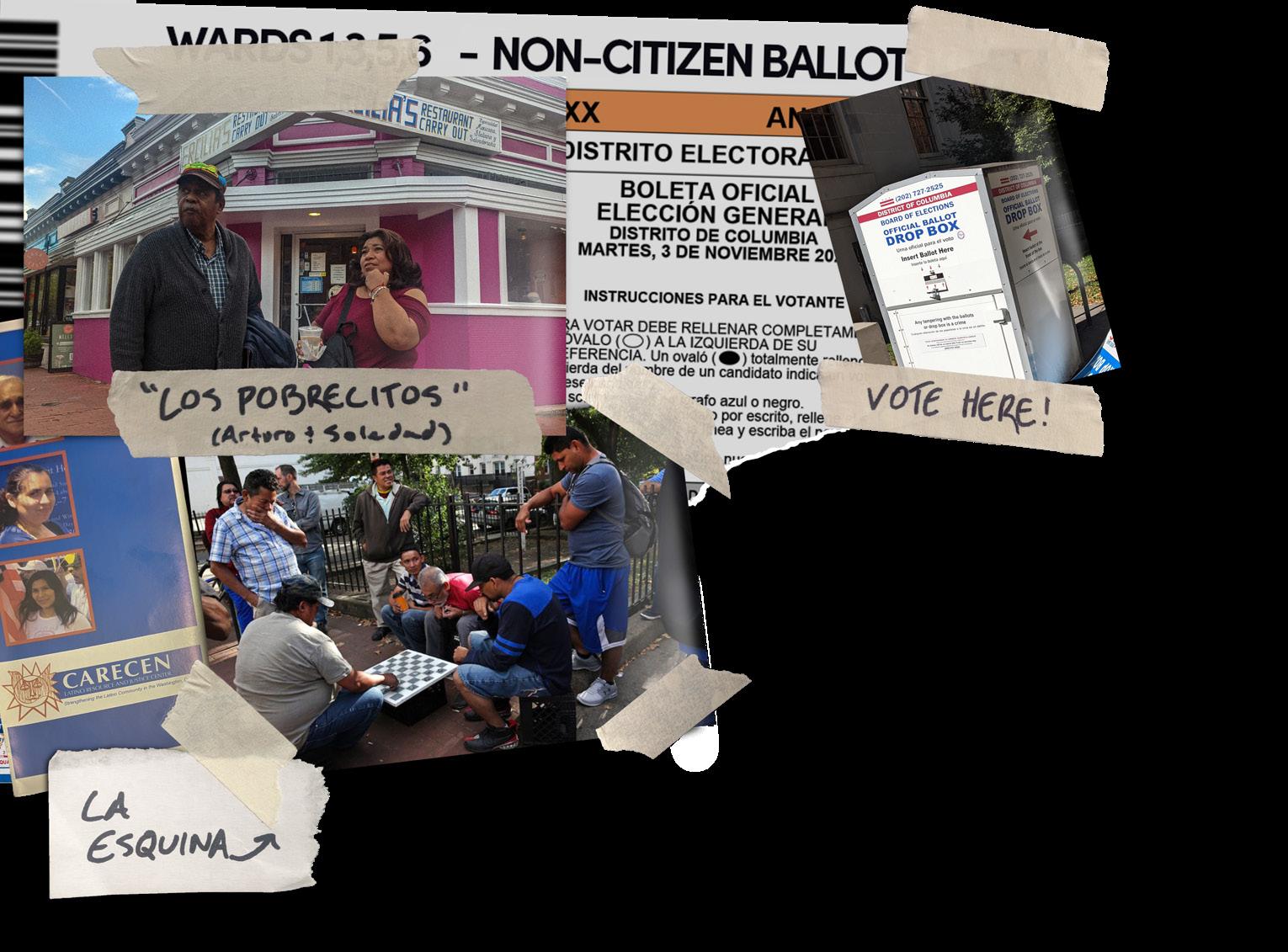

photos

courtesy of sarah watson; adam fagan (cc By nc sa 2.0); airBus777 (cc By 2.0)

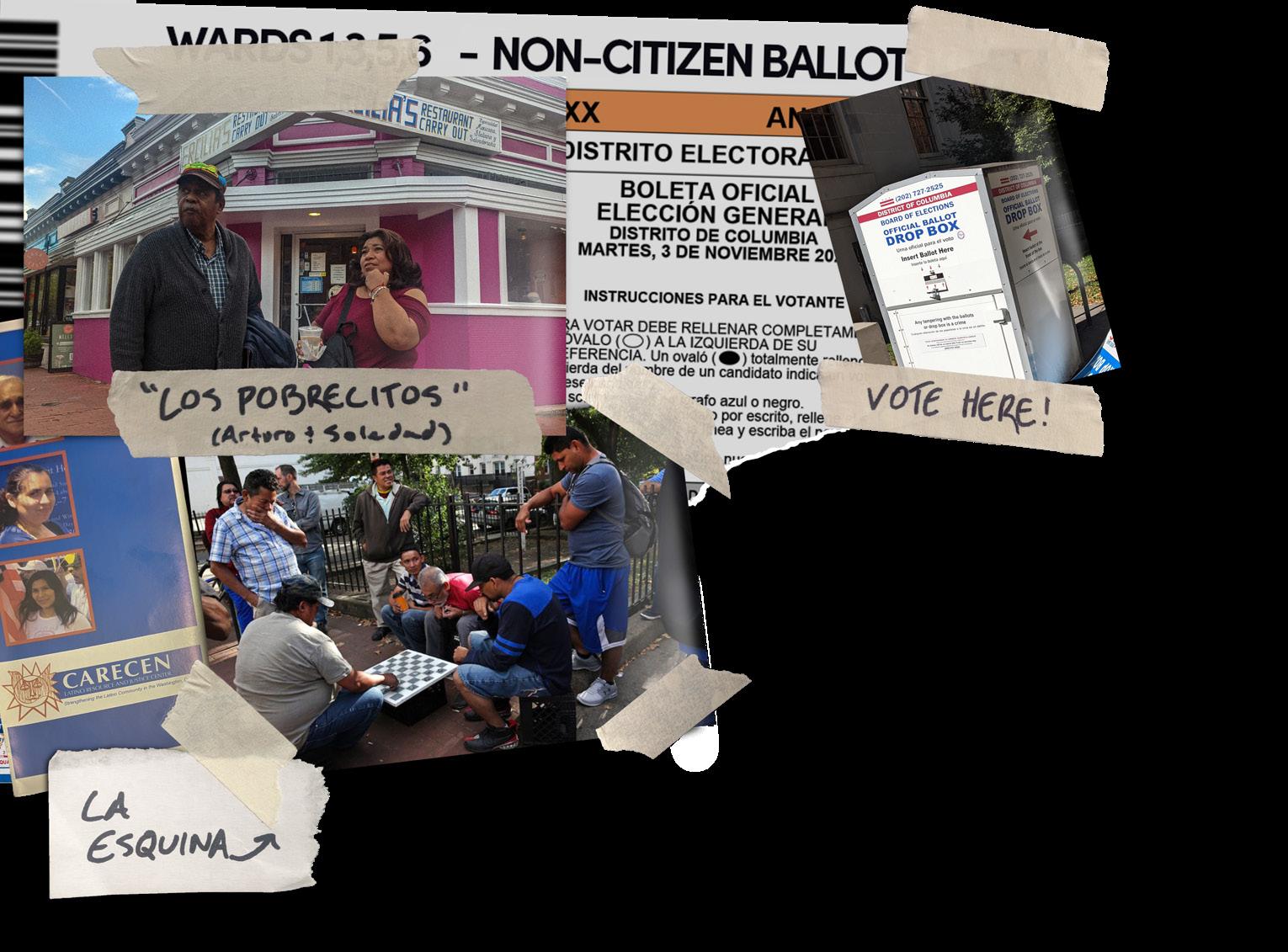

Located at the intersection of Mt. Pleasant Street and Kenyon Street, “La Esquina” is always full of laughter, Spanish, and 7/11 coffee. For over 30 years, Salvadoran day laborers, nicknamed esquineros (men of the corner), have flocked to this vacant corner lot to play checkers with bottle caps and catch up about life.

As Mount Pleasant gentrified, the future of their paved oasis seemed uncertain. They didn’t have as much of a say as the new residents—most could not even vote, as non-citizens—but they feared development coming to the corner and pushing them away. So last October, community advocate Arturo Griffiths and Ward 1 Councilmember Brianne Nadeau got the corner lot officially designated as Amigos Park. It was a small win, but a meaningful one.

Now, Griffiths and Nadeau are part of an effort to give the whole immigrant community something much larger: a path to the ballot box. The Local Resident Voting Rights Act of 2021 would allow D.C.’s non-citizens—including undocumented immigrants—to vote in local elections. After almost a decade of discussion, it looks set to become a reality. But one question about the bill remains: Will the city invest what it takes to minimize potential dangers?

The idea was first proposed to the council in 2013 by Mayor Muriel Bowser when she was a Ward 4 councilmember. None of the previous versions of the bill passed committee, making last month’s unanimous approval a groundbreaking step nine years in the making.

Just one week later, on Oct. 4, the whole council voted on the bill, passing it 12-1. On Oct. 18, the bill passed the council a second time, unanimously, and as of the time of publication, it awaits Bowser’s signature to officially pass. Congress then gets 30 days to veto before it takes effect—one such veto bill has already been introduced in the House, but is unlikely to pass.

International students with F and J visas do not meet the residency requirement unless they’ve been in the country for more than five years. However, the bill would apply to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Temporary Protected Status (TPS) recipients. TPS applies

As D.C. nears suffrage for undocumented immigrants, activists hope for proper follow-through

BY GRAHAM KREWINGHAUS

to immigrants from countries like El Salvador, with 30,000 in the region, and Venezuela, one of the main countries from which the immigrants recently bused to D.C. came.

Griffiths, who coordinates the DC Immigrant Voting Rights Coalition, brought his friend Soledad Miranda when we met for our interview, just half a block from Amigos Park. We sat down at a window table at Ercilia’s, a Salvadoran restaurant where they seemed to know everyone. After I assured Miranda that sí, hablo español, she told me that her first job when she made it to D.C. was at Georgetown. “I was a cleaner,” she said between sips of horchata, “at the bookstore.”

Miranda’s been in Columbia Heights for nearly 29 years, longer than the Metro stop or the shopping mall that have reshaped—and gentrified—the neighborhood. Because she came here from El Salvador without documentation, though, she’s never been able to vote.

“In all this time I’ve been here, I’ve been learning that we the immigrants, the politicians just use us. Solo promete. Prome, prome, prome. Y not doing nothing,” Miranda said. She’s tired of these empty promises and eager to have her voice heard at the polls.

With the vote, non-citizens can finally shape the issues that matter to them, like housing, and can elect people who represent and stick up for them. “They’re not going to be dormant anymore,” Griffiths said. He knew the feeling well: Having immigrated from Panama in 1964, Griffiths only gained citizenship—and a vote—10 years later.

“I remember when I first stepped into the ballot box, I couldn’t speak that much English. So I had problems,” Griffiths said, laughing. “They weren't giving Spanish ballots. I didn’t know exactly who to vote for, but I didn’t see anybody that represents me running for office.”

“But it was a great experience. I kept learning and kept voting, and I've voted ever since.”

If the city doesn’t ensure these first-time voters are well-informed, though, the very act of voting presents a risk. Since D.C. is a federal enclave, local elections and federal elections happen on the same day and ballot. For an undocumented immigrant, attempting to vote federally is seen as misrepresenting your citizenship status—a deportable offense.

Abel Nuñez, the executive director of Central American Resources Center (CARECEN), opposes the bill because of the possibility that these new

voters will make a dangerous mistake on their ballots. He said he raised this concern in a committee hearing in July.

“If even one person makes a mistake, it’s one too many,” Nuñez said. “I don’t believe the benefit of voting outweighs the dangers.”

A Board of Elections representative said at the hearing that they plan to implement a new system in which voters identify themselves and are given either a citizen or non-citizen ballot. Still, Nuñez said he didn’t feel comfortable with the risk of error.

Nuñez also said he didn't want to add fuel to the right-wing, anti-immigrant fire responsible for sending buses full of migrants to the District, especially if the bill might only be progressive posturing, without risk-prevention measures to make it safe.

“Is this a vote to make us feel better that we’re giving people the right to vote? Or is it a true benefit, and we’re going to invest in educating people," he said.

Many in the Georgetown community would be affected by this bill, from workers to students to staff, like Juan Belmán, who works at the Kalmanovitz Initiative and on the university’s Undocumented Student Advocacy Coalition. Belmán is a DACA recipient, and said he’d be excited to vote.

“But I would also be very careful, like study everything legally to make sure I wasn’t, you know, breaking any laws in terms of federal voting,” Belmán said.

Jenny Park (COL ’24), the programming director for Hoyas for Immigrant Rights (HFIR), said the bill has HFIR’s full support. She noted that many undocumented Hoyas already study or organize around immigration rights.

“Being able to act on that by voting is going to be really empowering,” Park said. “It’ll help highlight those voices in the community.”

Miranda said she sees the bill as a win. However, she doesn’t think it’s going to erase the gap between native-born citizens and undocumented immigrants like herself and many of her friends.

“You will have your choice of where to live, what to do, and we do not have that opportunity. So, we will still have to come and cook, and clean, while the university students are in the office on the computer,” she said, pretending to type on our table in Ercilia’s. “It’s different.”

Griffiths swallowed his food and cut in, reaching out as if to pat me on the back reassuringly.

“It’s okay! We still like you guys.” G

OCTOBER 21, 2022design

by graham krewinghaus; photo courtesy of rick reinhart

NEWS

A s a Type 1 diabetic, I’ve been taking insulin for almost 10 years. A few years ago, I decided to explore why my medications cost so much. I started researching, and emailed the leader of a prominent diabetes advocacy organization. But instead of answering my questions, she told me that the way that I was referring to myself—I called myself a “Type 1 diabetic” in the email—was wrong.

She told me I need to use person-first language (PFL) rather than use identity-first language (IFL). In other words, she wanted me to say that I am a “person with Type 1 diabetes,” rather than a “Type 1 diabetic.”

At the time, I didn’t know what PFL was, and felt confused and embarrassed. How was the way that I referred to myself—and the way all the other Type 1 diabetics in my life referred to themselves—wrong?

PFL proponents argue that because it places the person before their disability in sentence structure, PFL emphasizes disabled peoples’ personhood instead of their diagnosis. But what person-first language fails to recognize is that disability is an essential part of identity for many disabled people, and it’s one that they shouldn’t have to minimize or separate from their personhood.

Person-first language has origins in the People First movement of the late ’60s and early ’70s, but it gained more momentum in 1992 when the American Psychological Association endorsed PFL (they later adapted their guidelines). Since then, PFL has been institutionalized as a linguistic norm in academic, healthcare, and political settings—including within powerful organizations like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In fact, as of 2006, official D.C. laws, regulations, articles, and publications are required to use person-first language.

Yet PFL is a norm that many non-disabled people have attempted to universalize, regardless of personal linguistic preferences within the disabled community. While some disabled people are fine with PFL, many prefer IFL, especially in recent years. As a disabled person myself, I have personal motivations for preferring IFL.

I was diagnosed at 11 years old with Type 1 diabetes (T1D), a chronic autoimmune condition for which there is no cure. For me and all other Type 1 diabetics, our disability is a major part of our daily lives. There are treatments: daily insulin injections (or continuous insulin infusion through a pump) and constant monitoring of blood sugar levels,

BY MARGARET HARTIGAN

but managing T1D is a 24/7 responsibility. With no possible prevention measures or cures, I will be a Type 1 diabetic for the rest of my life.

To de-emphasize that fact by suggesting I position it as a grammatical afterthought is to diminish just how important my T1D is.

Not only that, but person-first language also further stigmatizes many already-stigmatized conditions by suggesting that personhood is distant from and incompatible with disability. T1D, for example, is already a heavily stigmatized illness. In a country that values thinness so highly, just the word “diabetes” can feel controversial (the more common Type 2 diabetes is correlated with obesity and a sedentary lifestyle). With a host of visible medical devices on my body at all times, it’s impossible to hide from this stigma.

PFL takes away my agency to accept my T1D as a part of who I am. It just adds to this ever-present stigma and makes it seem as though my T1D is something to be distanced from or ashamed of.

For me, using identity-first language is a sign of solidarity. I’m not afraid to identify first as a member of a marginalized community. Other disabled people and activists agree, pointing out how being disabled is an essential part of their identities.

The Deaf community in particular has embraced this idea. The capitalized “Deaf” refers to people in the Deaf community with a shared culture and language, while the lowercase “deaf” refers to people who do not hear, but may not share the culture of the Deaf community. Here, too, identity-first language signals community membership: To call a Deaf person a “person experiencing deafness” not only separates a Deaf person from this community, but also reduces that culture.

And there are bigger problems facing the disabled community than whether to call someone a “diabetic” or “a person with diabetes.” Disabled people—especially those without insurance—face enormous medical bills, a lack of accommodations, and other barriers to full equality. These issues tend to be far more important to the disabled community than linguistic details.

Practically, person-first language is more convoluted than identity-first language; it focuses on semantics, rather than producing meaningful change. It can often take on a tone of performativity. What does it matter if you refer to me as a “person with diabetes” or a “diabetic,” if either way, I still can’t afford my insulin?

Some activists argue that IFL reduces people to their disability. They say that using PFL to say that they “have a” disability gives them power over it—as opposed to suggesting that a disability “has” them, as IFL might suggest.

For me, saying, “I’m a Type 1 diabetic” doesn’t make it feel like I’m only my identity, but that it’s important to my identity. It’s like saying, “I’m a Georgetown student,” “I’m a redhead,” or “I’m a writer”—which doesn’t reduce personhood, but rather emphasizes an important component of identity.

We shouldn’t shy away from the direct discussions of disability that happen through IFL. Especially in regards to healthcare, medical leave, and other politically relevant topics, viewing disabled people as a group with an inherent, shared interest—rather than people who simply “have” something—is a first step.

Neither the use of person-first nor identityfirst language should be mandated or policed: Rather, they should be used when specific contexts call for them (like if someone specifically requests that you use one or the other, or it just makes sense grammatically). The people who decide how language is used to describe this community should be disabled people, not nondisabled people.

Outside of discourse around disability, there are contexts where person-first language should be used. Certain communities, like people experiencing incarceration, utilize PFL, and we should adhere to their linguistic preferences. Those communities, however, reflect temporary conditions; for many disabled people, their identity is chronic and lifelong. So for many within the disabled community, using IFL is just as acceptable as PFL—if not more.

All disabled people should be able to choose how they would like to be referred. I have no shame in having T1D—in fact, I feel proud to be part of a community that has overcome extreme stigma, expensive (and rising) medical costs, the challenges of balancing blood sugar levels, and more. The nondisabled community should focus less on regulating language around disability and more on productively supporting the disabled community, advocating for accommodations and affordable healthcare.

So you can call me a Type 1 diabetic, or you can call me a person with T1D. But when I talk about myself, I’m going to continue to put my disabled identity first: I’m a Type 1 diabetic. G

6 THE GEORGETOWN VOICE VOICES design by connor martin

Lack of university support undercuts LGBTQ+ Resource Center during "OUTober"

BY JUPITER HUANG

Since 2009, LGBTQ+ members of Georgetown have celebrated “OUTober” as a way of building community, showing pride, and holding dialogue about gender and sexuality. This OUTober, however, the LGBTQ+ community at Georgetown faces a glaring and continual problem: Since the beginning of the fall semester, the LGBTQ+ Resource Center has been operating without any full-time, professional staff members.

Two years after the departure of the center’s longtime director, Sivagami “Shiva” Subbaraman, the university has still failed to hire a replacement, leaving the associate director, Amena Johnson, to run the center by herself. Johnson, who started working at the center in 2019, alerted the university of her departure on Aug. 15—now, months later, the process of finding a replacement has only just begun.

“It shows you where the priorities of the university lie, and it is clear that LGBTQ+ issues are not in the university’s priority list,” Ulises Olea Tapia (SFS ’25), who worked at the Resource Center for two semesters last year, said.

The LGBTQ+ Resource Center provides students with a variety of crucial services, from serving as a resource for students questioning their identities, community building, semiconfidential reporting for Title IX, and helping gender-nonconforming students change their names and pronouns in the university record system and apply for housing. Its centrality makes the lack of a permanent staff member particularly concerning.

In an email response sent to The Hoya and the Voice, Johnson explained her departure. “It was clear that I was not going to be promoted to director after over a year of acting in that role without the title or pay of that role. Although I received a raise, the pay at Georgetown was not enough,” Johnson wrote. “As a Black woman, I experienced many macro and microaggressions at Georgetown,” she added.

Johnson’s departure highlights a broader issue faced by campus centers dedicated to serving marginalized students. The university has kept several of these essential centers— including the Disability Cultural Initiative and Women’s Center—as single-person offices, running the risk of completely losing center functions if the sole professional staff member maintaining its operations leaves.

Claire Alarid (SFS ’24), the only returning student worker at the LGBTQ+ center, noted the impact of the university’s inaction. “I am, for all intents and purposes, the most senior person at the LGBTQ+ Center. That’s not a good thing. I’m a student worker,” Alarid said. “There won’t be a staff person in the office if students want

to talk. There won’t be those resources at a professional level of support that Georgetown should be providing.”

Upon visiting the center on Sept. 29, Voice journalists solely encountered one member of the Military and Veterans’ Resource Center staff who volunteered to cover the shift in Leavey 325 that afternoon.

Georgetown has stated that it is attempting to guarantee the same level of support for LGBTQ+ students despite staffing problems. “While there have been staff departures, we are working to ensure that there are no disruptions to the services provided to students on campus,” a university spokesperson wrote in an email to the Voice. “We appreciate the staff who are supporting students in the Center currently.”

Despite Georgetown’s assurances, the LGBTQ+

ability to train its four new student workers. “I will be training them, and the Women’s Center director will be training them, which is obviously not ideal,” she said. “What’s going to happen is that some of [the responsibilities] are going to fall to the Women’s Center’s [Associate] Director, who is already underpaid and overworked.”

Many of the responsibilities of organizing programming for LGBTQ+ students have also been passed on. “I am also coordinating publicity for OUTober and facilitating Hidden Mercy, an event with journalist Michael O'Loughlin [on the actions of Catholics during the AIDS crisis],” Selak wrote in an email to the Voice .

Georgetown initially refused to recognize LGBTQ+ student groups, but eventually changed its position after a coalition of undergraduate and law students sued the university in 1981 for violating a clause of the D.C. Human Rights Act. Due to continued student advocacy over the next 20 years, President John DeGioia finally agreed to the creation of the LGBTQ+ Resource Center in 2008, making Georgetown the first Catholic university to establish such a center.

“I think it is very important to stress that LGBT struggles at Georgetown have advanced not because of the kindness of the administration, but because of the advocacy of the people at Georgetown,” Tapia said. “We cannot slide back to 2007. We cannot slide back the work that took so much work, so much effort, from so many people.”

Resource Center relies heavily on the work of student affairs staff from other understaffed campus centers, adding a significant workload to those who volunteer. This has fallen most heavily on the Women’s Center, located just next door.

Founded in 1990, the Women’s Center was established as “a space for women—faculty, staff, and students—to build community and thrive on the Hilltop.” With the departure of its director, Laura Kovach, in 2018, the Women’s Center also came under the directorship of Subbaraman. With her retirement, the Women’s Center was also left with only an associate director, Annie Selak. The university has since placed both centers under the Office of Student Equity and Inclusion (OSEI), reporting to the associate vice president for student equity and inclusion, Dr. Adanna Johnson.

Alarid noted that recent under-resourcing has especially affected the LGBTQ+ Resource Center’s

Tapia also emphasized the particular importance of the LGBTQ+ Resource Center in the current political landscape, noting a nationwide surge of anti-LGBTQ+ bills filed in state legislatures and fears among some legal experts that the Supreme Court may overturn pro-LGBTQ+ rulings. “The existence of the center is essential for the development of the students,” he said.

For Alarid, the university’s failure to properly staff the center paints a deceptive image for new students hoping to find a community here—especially given that standard Blue & Gray tours explicitly advertise spaces like the LGBTQ+ Resource Center as key student resources. “Georgetown is probably one of the only Catholic universities in the country that has an LGBTQ+ Center. It should be proud of that,” she said.

“But if it’s going to show that off to new students and tell students that they have all these resources, then they need to adequately fund that, they need to actually back it. It can’t just be an empty promise.” G

7OCTOBER 21, 2022 NEWS

design by cecilia cassidy

Educator exodus: Inside D.C.’s teacher turnover crisis

BY SARAH CRAIG

After 20 years of teaching, Jessica Salute is beginning to hit her breaking point.

“I’m having a tough year,” she said. “For the first time I’m really thinking like, ‘I don’t know if I can keep doing it.’”

Salute, a second-grade teacher in Ward 8, has spent this academic year feeling overwhelmed by long hours, intense evaluations, and a lack of administrative support. Her conclusion mirrors that of many other teachers in the country: It’s all too much.

“The stress feels like so much. And it’s making me a worse teacher; that’s what scares me, what I haven’t felt before,” Salute said. “I am not able to be my best for the kids because of the challenges and the pressure.”

Though teacher turnover has long been a nationwide issue, attrition rates have only risen since the beginning of the pandemic. The national average for turnover in urban schools falls between 16 and 19 percent, with around 54 percent of teachers reporting they were either “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to leave the profession in the next two years, according to a 2021 survey.

It’s an alarming high, especially here in the District. D.C. currently has the highest urban turnover rate in the entire country. Between the 2020-21 and 2o21-22 academic years, D.C. saw a city-wide turnover rate of 26 percent, with Wards 4, 6, 7, and 8 averaging 30 percent.

So, what’s behind this revolving door of teachers in the District?

For many teachers in D.C. Public Schools (DCPS), one culprit immediately comes to mind: the internal evaluation system IMPACT.

Introduced by DCPS in 2009, IMPACT is meant to optimize teacher performance. The evaluation scores teachers in five categories: student achievement, instructional expertise, instructional culture, community collaboration, and professionalism.

Yet the system was rated the highest driver of turnover in the 2020 Teacher Attrition Survey. The following year, the D.C. State Board of Education (SBOE) found that only 31.6 percent of teachers in DCPS believed their IMPACT evaluation would be fair and credible.

IMPACT “creates this fear that every time [teachers] step into the classroom, it’s for the purpose of evaluation,” Scott Goldstein, Founder and Executive Director of EmpowerED, an

educator advocacy non-profit, said. “It makes it very hard to have really open communication and a culture where everybody's growing.”

Evaluations are conducted by school administrators, sometimes unannounced. Many teachers feel that the evaluations are subjective, relying too heavily on their existing relationships with administrators. Some also argue that IMPACT facilitates a simple system of reward and punishment, rather than nuanced growth: Teachers who are rated “highly effective” are given a $2,000 bonus, while teachers who are rated anything less than “effective” run the risk of losing their jobs.

IMPACT was actually what once attracted Salute to working in DCPS, because she thought that the tool’s rigor would make her a better teacher. After nine years of teaching in the district, however, her opinion could not have changed more.

“It’s so stressful and so anxiety-provoking, and I think there’s so much energy put into it with very little benefit,” she said. “It will definitely be one of the reasons if and when I leave DCPS.”

For some teachers, IMPACT is nowhere near as stressful as other evaluation systems.

“I can understand why people hate it,” Rian Reed, a Ward 8 middle school teacher, said. Reed’s previous school district utilized the highly-criticized Danielson evaluation model. “But I’m coming from an experience that was worse, in my opinion.”

Some teachers have questioned whether IMPACT is equitable. In 2020, the American University School of Education conducted a study—commissioned by DCPS—that found IMPACT to be racially biased. Finding that Black and Latinx teachers consistently scored lower on their evaluations than white, Asian, and Native American teachers, the study identified a “potential bias in the rubric or observations in which Black teachers are stereotypically perceived as more culturally competent or nurturing but not recognized for their contributions to academics.”

One teacher participating in the study said that the creation of IMPACT didn’t just force teachers of color out: “It was that they replaced them with younger white teachers who were not from the area, who did not understand the culture of these students, and it was okay, and so because of its origins, it’s always going to be problematic.”

Another study participant corroborated this view: “It’s very prejudicial, and it didn’t help that the people who created it were not people of color, but they came and slammed this down

into communities where students and families were already suffering.”

Turnover rates are likely to be higher at schools with a higher number of students categorized as “at-risk”—schools that are typically in Wards 7 and 8, exacerbating other systemic inequities between wards.

This correlation does not exist because atrisk students are harder to work with—that’s

8 THE GEORGETOWN VOICE FEATURES

Education, Inquiry, and Justice Department, said. “Most teachers know [testing] is not what's in their students’ best interest, and it’s really hard to do a job that’s already super demanding when you know you’re not doing what you should be doing.”

In some cases, turnover extends to entire schools. Laura Fuchs, a high school teacher in Ward 7 and a leader in the Washington Teachers Union (WTU), recalls ward-wide closures during the late 2000s.

“I would have kids who would be in middle school, and their elementary school got closed. By the time they got to high school, their middle school had been closed behind them,’” she told the Voice, pointing out the loss of community that happens when schools close.

While teacher turnover and school closures

means that extracurricular activities are interrupted, something that Fuchs has seen first-hand.

“People start clubs—well-meaning new teachers, maybe not new to teaching, but new to the system—and then they go ‘Oh, I’ll do debate,’ but they’re gone the next year. So who’s doing debate next year?” she said.

Fuchs described how her school has not been able to retain a music teacher—nor a band program—in several years. “Everything is always turning, so you can’t really build much. It’s hard to hold onto traditions,” she said.

As extracurricular activities often help support student well-being, this disruption poses significant challenges to fostering a culture of wellness.

For Goldstein, creating this culture begins with making sure teachers feel adequately supported.

“Education is fundamentally a human enterprise,” Goldstein said. “Teachers have to have their cups filled to be able to pour into our students. There's no conflict between educator wellness and student wellness—they require each other.”

Unsurprisingly, the D.C. SBOE found that a lack of support for teacher wellness was a major contributing factor to high turnover rates; it’s a struggle that Salute knows all too well.

“I am not able to be my best for the kids because of the challenges and the pressure. I want to do everything I can—I’m in therapy, I’m doing exercise—I’m doing all of the things and I still feel like it’s impossible, what [DCPS is] asking me to do,” she said.

For Gasoi, supporting the wellness of educators “comes down to acknowledging the stress and trauma that educators have been going through over [the pandemic], and acknowledging it by actually making their work situation more manageable.”

In a joint study with WTU, EmpowerED found that strategies to make educators’ work situations more feasible—and to prevent turnover—include providing flexible scheduling options, higher pay, increased support, and more professional autonomy. According to Goldstein, flexible scheduling is an alternative to the current “industrial revolution-era bell schedule” in schools, providing teachers more time for planning and students more opportunities for experiential-based education.

Reed, who teaches at a school where flexible scheduling is used, is very familiar with its benefits.

“On Mondays, the kids are dismissed at 1:30 to attend extracurricular activities with different community partners, or they can leave the campus in order to go home to handle family needs and such. And then that gives teachers the opportunity for additional co-planning and co-collaboration through team meetings. So it’s a win-win for the kids and the adults,” she said.

Reed described the retention rate at her school as “abnormally high,” in part because of the culture created by the administrators.

At Reed’s school, teachers have ample opportunity for leadership roles. “My

supporting teachers with high D.C. housing costs.

“Something needs to be done so that more people can actually live in the city where they work,” Quezada said. “I shouldn't have to live in a whole other state just to work in DCPS. I actually don’t—I'm able to live here [now], but I know it’s only a matter of time before my rent will be too expensive.”

While DCPS does have a program that supports teachers through the process of home ownership, these benefits do not currently extend to rental assistance (unlike benefits for D.C. police officers, which offer temporary housing and rental assistance in addition to the homeownership assistance program).

For Quezada, housing assistance is also related to securing a fair contract. “First, we need a contract. I think that would be very helpful because we’re working with the salaries of 2019. So that’s nearly four years of no cost of living adjustment, and considering that D.C. is one of the country’s most expensive cities, that takes a toll on people.”

While many schools have their own contracts with teachers, the last DCPS-wide contract expired in 2019. DCPS is still operating under the agreed terms of this contract, though the WTU is still fighting for a renewed contract, one that includes a wage increase.

Part of the picture also means negotiating better work-life balance. EmpowerED found that turnover is higher for teachers between the ages of 29 and 39, something they attribute to the difficulty of balancing teaching and parenting.

For Salute, this balance is a salient concern. “I can’t work until 9 p.m. and wake up at 4:30 a.m. or 5:00 a.m. for the rest of my life and maybe be a mom at some point, too,” Salute said. “How would I ever be a mom?”

As systemic support for D.C. teachers remains stagnant, teachers are left without answers to hard questions. “I don’t think I can actually work any more hours, so what can I do now?” Salute asks. “Is it fair for the kids? Is there someone who could be doing this better?” G

9OCTOBER 21, 2022

Georgetown Explained: Georgetown’s application process

BY YIHAN DENG

The Georgetown admission process is an oddity.

Alongside MIT, Georgetown is one of the two top private universities that refuses to use the Common Application. This decision has stirred controversy, since some argue that Georgetown’s separate application hampers accessibility and subjects applicants to additional stress. With students preparing for Georgetown’s Jan. 10 regular decision deadline, debate over the university’s application has returned to the forefront.

Charles Deacon (COL ’64), dean of Georgetown undergraduate admissions since 1972, believes that the university’s application advances a “student-centered” approach, facilitating close student-university relationships. Its idiosyncrasies include four supplemental essays with page rather than word limits, a shorter extracurricular profile than the Common App, and alumni interviews for every applicant.

“We feel like the application for admission is the beginning of your relationship with the school,” Deacon said. “It gives you an opportunity to tell your story without being limited by a three hundred-word essay.”

Sophia Lu (COL ’26) is among those who believe Georgetown’s application encourages rather than deters applicants. “In that extra effort I had to put in, it made me think more about why exactly I wanted to apply to Georgetown,” she said.

In Deacon’s opinion, the Common App can’t provide the same kind of intimacy. “We always felt that the Common App depersonalizes to some degree,” he said.

He also sees the Common App as a tool colleges use to grow their applicant pool and therefore deflate their acceptance rates, rather than evaluate applicants accurately.

“We think there’s an admissions process in institutions across the country that’s business-

oriented,” he said. Deacon noted that acceptance rates only affect lay prestige. “It’s all about manufacturing data that will enhance your reputation,” he added.

Deacon explained that Georgetown is not interested in bumping up numbers for the sake of image. Instead, he wants to prioritize recruiting exceptional students who truly fit the community, and he believes Georgetown’s specific application is critical to that aim.

According to Deacon, the separate application is itself an indicator of “demonstrated interest.”

“We get a great student body because they end up choosing us,” he said.

Frederick Mwansa (SFS ’26), an international student from Zambia, found that the separate application didn’t deter him much from applying. “The name of the school itself is very out there. If someone from Zambia can find that the school exists and get here, I think anyone can find it,” he said.

Other students aren’t convinced that Georgetown’s application benefits applicants or the university. To Aaron Chan (SFS ’26), the application makes the process more confusing without improving the quality of the student body. “The Common App’s user interface is a lot easier to navigate and a lot more direct than Georgetown’s,” Chan said. “Georgetown’s looks like it was made in the 2000s and never updated.”

However, because admissions staunchly believes in the efficacy of their application, it’s unlikely Georgetown will change its interface or its admissions process any time soon.

Once students submit their applications, four admissions officers each assign an application a score on a 10-point scale, adding up to 40 points. Applicants who receive eights or higher across the board stand a high chance of being admitted. After all applications have been scored, the officers begin admitting the highest scorers until no spots are left.

According to Georgetown’s Common Data Set (CDS), a yearly report on the university’s admissions trends and policies, academic performance is given the most weight when scoring an application. Extracurriculars and the interview follow close behind, while factors such as first-generation status, legacy affiliation, and ethnicity fall into the lowest-weight category.

While Georgetown’s admission standards are consistent with most peer institutions, the university has been previously criticized for not making more progress with equitable admissions. According to the CDS, only about 7 percent of the non-international undergraduate student

body is Black and 8 percent is Latino, far less than national proportions. Students routinely argue that Georgetown’s admissions give an unfair advantage to wealthy, predominantly white students via mechanisms like legacy admission.

“[Georgetown is] not as diverse as it should be,” Deacon said. But he’s more concerned about income disparities than ethnic diversity, since wealthy students occupy an outsized share of the university’s seats. “Disproportionately, students coming here are higher-income,” he added.

While the university has the funds to offer lowincome students full financial aid, middle-income students often face the greatest financial barriers, since their aid is often not enough to offset Georgetown’s hefty tuition of almost $60,000 a year. According to Deacon, many comparable institutions with larger endowments do not face this problem. Georgetown has a notoriously low endowment, especially among private institutions.

In fact, endowment size is so important that the admissions office insists on maintaining legacy admissions partly to improve access to aid.

“They want to be here, the record is good, the family contributes to the university,” Deacon said about legacy students. “26 percent of your tuition dollar goes to support financial aid, so they’re underfunded. Legacies help.”

He emphasized that legacy status only impacts admission when a student straddles the line between acceptance and rejection. “We feel it is legitimate, and we feel we do it in the right way,” Deacon added.

Critics of legacy preference point out that legacy admissions do not necessarily increase alumni giving by a statistically significant amount. They also argue that prioritizing profits over fair admissions compromises the university’s values.

Besides legacy preference, Georgetown has room for progress in other areas of equitable admissions as well. Moving forward, the admissions office has set specific goals for diversity and inclusion. According to Deacon, admissions hopes that at least 10 percent of the student body is composed of Black students in future admissions cycles. How the university plans to tangibly accomplish this goal remains to be seen.

As for the application itself, Georgetown’s distinctive, if cumbersome, process seems here to stay.

“It means [students] have to do more work,” Deacon said. And even if Hoya hopefuls must slog through the outdated user interface and additional application requirements, in the eyes of admissions, it’s worth it. G

NEWS design by grace nuri

All my friends are NFL head coaches

BY SAM LYNCH, BRADSHAW CATE, AND TIM TAN

Thirty-two NFL teams play every season, but according to ESPN, there are 40 million head coaches keeping an eye on their teams every week. Fantasy football has been taking over the country, and Georgetown students are not immune. At Georgetown, fantasy leagues provide a means to make new friends and maintain existing friend networks through all the changes of college life. Three of our Sportz writers looked at the ways fantasy football has impacted their social life on the Hilltop.

Building community on the Hilltop Fantasy football and I go way back. My dad has played fantasy football for years, ever since legends like Marshall Faulk and Marvin Harrison graced the top of the scoring charts. Throughout elementary school, I would track my dad’s fantasy success, follow player stats, and help him with roster decisions.

When my uncle invited me to join his league almost 10 years ago, I jumped at the chance. As a sixth grader, I finished the regular season 11-2 (still my best record ever), swept through the playoffs, and won my first championship. Although that league folded, I competed in a different league each fall through my senior year of high school.

While those high school leagues were fun, a sense of community was missing. Players would lose interest, making winning easy, and computerized drafts made everything feel distant even when I attended school with the other participants.

When I left for college without a league, I had to start from scratch. I wanted to hold a live draft (draft board and player stickers included) with snacks, drinks, music, and fellowship—the whole shebang. The goal: to gather together a group of freshmen with the common interests of fantasy football and meeting new people. Before I even got to campus, I got to building a league. In the end, I gathered a group of around 40 people, but was faced with the complicated logistics of dividing into teams and managing the league.

Settled into New South 121 and undeterred, I taped a signup sheet for a floor-wide league to the common room wall, assembled a 12-team league, and scheduled a draft.

The draft was a resounding success. Everyone attended, we picked random cards from a deck to determine our draft order, and we stickered every draft pick onto the wall. Whenever I ran into my league-mates around campus throughout the fall, we would talk about football.

In the end, I won our first league championship, but the league meant far more than a simple win. I knew I had to run it back. I had to find six new members this summer, but we eventually filled out the league and held another draft (live, of course) the day before the season began. No matter what happens, I look forward to our league continuing to carve out a sense of community among fantasy football fanatical Hoyas like me. —Sam Lynch “Home” field advantage: How fantasy connects friends thousands of miles apart

The beginning of my senior year in high school, I was on a mission to start a fantasy football league. Amongst my friends, I was the only one who watched the NFL. When I pitched starting a know-nothing league, I thought no one would be interested. Instead, my friends were all for it.

We bought into every stereotype we knew about fantasy football—including hosting a draft at a Buffalo Wild Wings. Afterwards, we ate some wings, debated our draft picks, and teased each other’s terrible mistakes—like not taking a kicker as a first-round pick. We had no idea what we were doing, but we were having fun.

The league quickly became a central part of my senior year. Depending on how well my players did each week, I either dreaded Monday mornings or couldn’t wait to get through the doors. Comparative Politics turned into Comparative Fantasy Football. We exchanged snooty comments during class, but always had a blast talking about our teams.

With the community we had built, leaving for college felt like a gut punch. We committed to colleges across the country, and staying in touch with eight to 10 people has been challenging. College life is overwhelming—the Jesuit education is no lie—and not conducive to running a football team.

But the worst thing about going to college is that we could no longer meet at a Buffalo Wild Wings.

Thankfully, we found fantasy football to be a beacon. There’s always something to talk about. Not

only that, we all share a common experience, even thousands of miles apart. I hope my home league continues throughout college because it brings me closer to the friends I love.

What started out as a joke evolved into something more: a way to stay connected as we break out from our “home huddle” to our spots across the country. —Bradshaw Cate

Fantasy football for senior year and beyond I’m currently in a fantasy football league made up of a friend group that started out in freshman year. Our league membership runs the full spectrum of Georgetown—we have students from every undergraduate school on campus and almost every religion represented in Campus Ministry. Our homes are all over the country and we, or our parents, immigrated to the U.S. from all over the world. But no matter where we come from, we all share in the excitement of football and the camaraderie of friendly competition.

But fantasy football serves a broader purpose as well—to create a community whose boundaries reach beyond the college campus. “As a senior, it’s been really cool to participate in a league this year with a few students who have graduated and stay connected with them,” Divjot Bawa (SFS ’23), one participant in my league, said. “As a diehard football fan who will probably continue to sacrifice an hour or two every Sunday, I can’t imagine myself not carrying on this tradition.”

As a group of seniors who have been through a bizarre, pandemic-stamped college life, fantasy football has brought the participants in my league together through the ups and downs of the last four years. As we look ahead to graduation, fantasy football serves another purpose—forming the roots for a community that will hopefully last well beyond our departure from the Hilltop.

Regardless of where we go after college, we’ll all be able to look forward to the thrill of fantasy football and enjoy the strength of the friendships we’ve built through this pastime.

—Tim Tan G

illustration by elin choe; layout by dane tedder

11OCTOBER 21, 2022 HALFTIME SPORTS

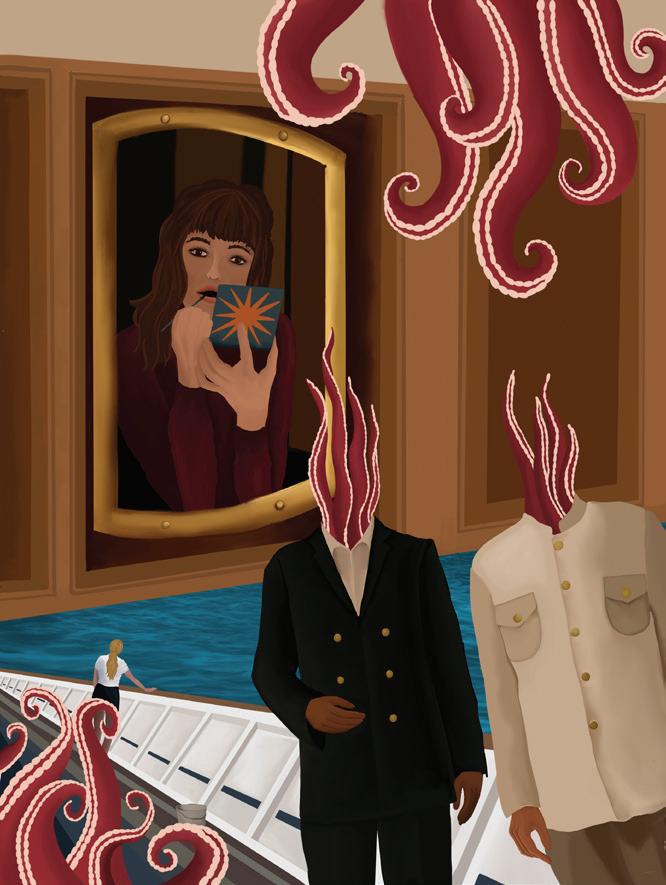

Triangle of Sadness is a parable about beauty and excess

BY CHETAN DOKKU

There’s a scene in this year’s Cannes Palme d’Or winner Triangle of Sadness (2022) in which a millionaire shipwrecked on an island stones a donkey to death, its final groans echoing through the jungle. It’s an excessively disturbing experience for everyone involved: the millionaire, the other castaways, and the audience.

This provocative approach to inflicting agony on his subjects tracks throughout Swedish filmmaker Ruben Östlund’s latest movie. It’s a blunt, effective, and at times tough-to-watch satire of the ultra-rich and the fashionable, two easy targets for Östlund’s particular brand of wit. But the film truly shines when dissecting the economic value of beauty as it exists today with Instagram influencers and their ilk.

Triangle of Sadness follows a model couple, Carl (Harris Dickinson) and Yaya (Charlbi Dean Kriek, in her last role before her tragic death this past August), as they navigate the troubled intersections of excessive money and high fashion. Carl has insecurities about his career and their relationship that are only compounded by Yaya’s manipulative behavior. Early in the film, the two have a standoff at a restaurant over who will foot the bill—Yaya gets paid three times as much as Carl, but expects Carl to pay for dinner and doesn’t like to talk about money. The fight escalates into an elevator screaming match before cooling into an honest conversation about gender roles, highlighting how money complicates their relationship.

In an interview at Cannes, Östlund acknowledged that Triangle of Sadness and his two previous films, fellow Palme d’Orwinner The Square (2017) and Force Majeure (2014), form “a loosely-connected trilogy exploring masculinity in modern times.” Carl struggles to reconcile his financial status in relation to Yaya, and Dickinson impressively portrays these complexities; Carl whimpers as Yaya’s Instagram boyfriend, bumbles into her rhetorical traps, and occasionally lashes out before being put back in his place.

The couple embarks on an all-expensespaid luxury cruise, courtesy of Yaya’s influencer side hustle. The whole cruise experience has been meticulously planned by head steward Paula (Vicki Berlin), who has instructed the crew to follow every passenger order in the hopes of a hefty tip at the end of the trip. The ship is captained by a feckless, alcoholic Marxist (Woody Harrelson), and the couple joins a group of obnoxiously wealthy passengers—oligarchs, arms dealers, tech mavens—that quickly starts

to fall apart. The toxic relationship between the out-of-touch passengers and obsequious crew leaves a bitter taste from the get-go.

One day, some of the passengers cruelly demand the entire crew go for a swim while they’re preparing the elaborate captain’s dinner for that evening. When a storm hits, unsettling a boatful of stomachs lavished with spoiled seafood and champagne, a torturously graphic extended sequence follows of retching, belching, and shitting: a sensory overload of bodily fluids made even worse by the back-and-forth rocking of the camera with the storm waves. Östlund lays the critique on heavy as the captain (who conveniently orders a burger) and Russian oligarch Dimitriy (Zlatko Burić), the self-styled king of shit, drunkenly argue over the ship’s intercom about Marxism and capitalism, trading Reagan, Thatcher, and Lenin quotes while the passengers lay defeated in the ship, now without power and inundated with toilet water.

The cruise ends prematurely—it’s attacked by pirates and blown to bits by grenades produced by the sweet, elderly British arms dealer couple, Winston (Oliver Ford Davies) and Clementine (Amanda Walker), whose names are a clear nod to the Churchills—but some of the passengers and crew survive and swim to a deserted island with only the limited provisions stored in the lifeboat. The castaways soon realize how ill-equipped they are for survival in a world where their money is no longer currency, paving the way for Abigail (Dolly De Leon), the ship’s former toilet manager and the only person who can fish, cook, or start a fire, to become the new leader.

Dimitriy, a former Reagan-loving Russian capitalist, quotes Marx—“from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”—

trying to make the situation more equitable, but the freshly-minted socialist’s pleas are left unanswered. They need Abigail far more than she needs them, and she relishes in the power this imbalance creates.

De Leon steals the third act as the nononsense autocrat, demanding deference, meting out food and punishments, and trading sexual favors from “pretty boy” Carl for extra rations of pretzels. The tables turn for Carl, who finally finds himself in a relationship with a woman who provides for him, and for Yaya, whose beauty no longer carries any cachet. Her descent on the island is one of the comedic highlights of the film, as her Instagram-worthy tresses are reduced to a frazzled mess full of pretzel crumbs.

Much of the discourse surrounding Triangle of Sadness has centered on its showpiece vomiting sequence and its skewering of the ultra-rich but glosses over its treatment of beauty, the film’s most incisive and exciting critique, and Östlund’s starting point for the movie as a whole. In an interview with the LA Times, the filmmaker notes that “I knew from the beginning that I wanted the film to be about beauty as a currency.” Carl and Yaya’s contrasting experiences with the monetization of their attractiveness in the world, flipped when stranded on the island, encapsulate the problems of an economy built on valorizing beauty. Carl’s attractiveness is not a skill that helps the group survive, and yet he is rewarded for it. And the issues it causes for the couple—anger, jealousy, insecurity—only add to Östlund’s point and make the film even more hilarious.

Triangle of Sadness succeeds in satirizing excess and artifice, as expected from a filmmaker like Östlund. Its chaotic structure further lends itself to the outrageousness of its characters. But the film’s critique of beauty as currency elevates it and makes the film truly exceptional. We seem to take for granted that beauty engenders privilege, but the sheer absurdity of this notion— like Yaya posing as if she’s about to eat a forkful of pasta for a promotional Instagram post before setting it aside (she’s gluten intolerant)—is often willfully ignored. Triangle of Sadness delivers this message throughout the film’s 149-minute runtime, one entertaining, potentially vomitinducing forkful at a time. G

12 THE GEORGETOWN

VOICE

LEISURE

layout by alex giorno and max zhang; photo courtesy of neon

The definitive guide in preparation for The Car

BY ANNETTE HASNAS

On Oct. 21, Arctic Monkeys are releasing The Car, their seventh studio album, making this fall the perfect time to get into the staple alternative rock band. Here’s everything you need to know about their previous albums if you want to become a certified fan of my favorite little band from Sheffield.

WhateverPeopleSayIAm,That’sWhatI’mNot (2006)

The one you probably know: “I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor”

The second on the album, this song’s focus on dancing and club culture expertly taps into the 2000s teen zeitgeist that characterizes this whole album. It’s no wonder I still see people wearing T-shirts with reference to its lyrics at Arctic Monkeys concerts over a decade after the album’s release. Song to start with: “When the Sun Goes Down”

This track is a perfect entry point into Arctic Monkeys’ special brand of grimy garage rock. After a slow, pared-back beginning, the song catapults into an energetic drum beat similar to others across the album. The musicality and lyricism on display familiarize you with what sort of world you’re going to be dealing with for the next 13 songs—it’s grungy, it’s raw, and it’s “all not quite legitimate.”

Overlooked gem: “You Probably Couldn’t See for the Lights But You Were Staring Straight at Me”

Instantly relatable to anyone who’s tried (and failed) to flirt at a loud party or club, the lyrics are refreshingly innocent. The youthful awkwardness described here by a freshly 20-year-old Alex Turner can’t help but seem sweet, especially when compared to the hardened exterior of the rest of the album.

AM (2013) The one you probably know: “Do I Wanna Know?”

I don’t need to explain this one. You’ve heard it, you love it, you get the idea. Song to start with: “Why’d You Only Call Me When You’re High?”

Though not as popular as “Do I Wanna Know?,” this song is also well-known even outside of the band’s fan base, and for good reason. Catchy and with easily recalled lyrics, it’s an easy entrypoint even if other Arctic Monkeys songs aren’t your speed, but with just the right amount of retro-style sleaziness to match the vibe of the album. Overlooked gem: “Fireside”

It is a crime that this is one of their least streamed tracks. Despite treading the worn ground of breakup songs, the song invokes careful imagery on display here, leaving the track fresh. It’s relatable to people who have had their hearts broken without bringing down the tone musically (I love it despite being a noted Slow Song Hater). Additionally, I love this song’s foray into rockabilly stylings with its little “shoowops”; every time I hear it, I wind up singing it all day.

Favourite Worst Nightmare (2007) The one you probably know: “Fluorescent Adolescent”

It’s the most recognizable song off the album (though, interestingly, not Spotify’s most popular—that’s “505”), and for good reason. Fast-paced with an addictive beat, the song bears punchy lyrics that roll off the tongue with just the right amount of Britishisms for the Sheffield band (it’s one of the few songs I know with an earnest use of the word “daft”). Song to start with: “Do Me a Favour”

“Do Me a Favour” perfectly taps into the almost paradoxical nature of Favourite Worst Nightmare , an album simultaneously more aggressive yet more relaxed than Arctic Monkeys’ debut, which was much more tied to their garage rock sound and less emotionally varied. This song mirrors this natural but noticeable shift beautifully. This selection proves that the band didn’t have to drop their iconic aggressive energy you’ve come to know and love to fit in with the more mature sound of FWN Overlooked gem: “The Bad Thing”

This song might not have anything too deep to say, but that doesn’t make it any less of a banger. It’s a fun snapshot of a moment in which the singer is propositioned by a taken woman, with some general thoughts on infidelity sprinkled in for good measure. This song sounds great—intense and rock-y to its core. Lyrics that move at a breakneck speed make singing along a challenge, but you’ll undoubtedly be proud of yourself the first time you’re able to get through all two and a half minutes without missing a word.

Tranquility Base's lead single, “Four Out of Five” is a lot of people’s (read: my) favorite song on the album. Taking inspiration more from glam rock than some of the other ’70s influences on the LP, it offers a bridge to existing Arctic Monkeys fans who came and stayed for the rock, while still following Tranquility Base’s stylistic divergence. Song to start with: “Star Treatment”

Coming back after a five-year break (which felt even longer considering their previous rapid-fire album-release rate), Tranquility Base changed a lot about the band’s style—and “Star Treatment” is a great gateway. Its very first lines, “I just wanted to be one of The Strokes / Now look at the mess you made me make,” tell you exactly what kind of rock-star stylings you’re in for. It’s a song narrated by the washed-up ’70s rockstar character, which perfectly sets you up for the sauve-to-thepoint-of-sleaze ’70s influence throughout the whole album. Overlooked gem: “One Point Perspective”

Look, I will be honest: I’m not a huge fan of this album, but even I have a begrudging respect for this song. Any fan of Turner’s lyrical style has plenty to work with here; his ambiguity and poetry are turned up to 11. It also has a noticeable instance of Yorkshire slang that calls to mind a similar moment on “Do I Wanna Know?” and reminds listeners that, though Turner has been living in LA for many years now, Arctic Monkeys haven’t forgotten their roots as the teenage British rock band behind Whatever People Say I Am . G

13OCTOBER 21, 2022design by lou jacquin and joanna li

TranquilityBaseHotel&Casino (2018) The one you probably know: “Four Out of Five”

WARPING THE MIRROR: FIVE HAUNTING LITERARY MONSTERS

BY LUCY COOK

For as long as humans have told stories, we have told of monsters. The Bible spawned the Devil and the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. The first true English-language epic, "Beowulf", is a tale of the monstrous Grendel, his mother, and one fateful dragon. What different cultures and societies across time have defined as monstrous offers an anthropological and philosophical perspective on what they both fear and desire. From mindless zombies to omniscient gods, literary monsters reflect and distort humankind.

As Halloween and mainstream seasonal acceptance of the monstrous approaches, here are five novels featuring monsters that served as effective mirrors for human nature.

A note: The monsters on this list are purposefully inhuman, as the term “monster” applied to human or humanoid subjects becomes much trickier and more subjective.

The Creature—Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818)

As the first true science fiction novel, Frankenstein was one of the earliest works to sympathetically approach monstrosity from the perspective of the inhuman itself. The Creature gets an enormously bad rap for what is essentially an ugly baby forced into the world, seeking acceptance and understanding in the wake of abandonment. That’s all of us; we are all the Creature. Such a depiction of the monstrous offers questions about humanity, how we define it, and whether that definition means anything at all. Over time, the portrayal of the Creature has evolved from an intelligent and sensitive creature seeking happiness to a mindless lump of electrocuted green meat, erasing all of Mary Shelley’s nuance and thoroughly disrespecting our boy. If anyone was a monster here, it was Victor Frankenstein, deadbeat dad and deranged college student with a god complex. Justice for the Creature.

Uprooted features a monster without a physical body. Instead, it is the corrupted Wood that plagues protagonist Agnieszka and her community, poisoning the minds and bodies of anyone venturing too near. The victims of the Wood lose their grasp on reality, their bodies calcifying into wood. Forests are timeworn fantasy and horror settings, often tied to an “uncivilized” unknown and, in Christian contexts, paganism and the Devil. This is not so in Uprooted; Novik’s Wood is simply misunderstood. Once, it was home to an ancient race of forest-dwelling people who, when met with humankind’s fire and axes, turned themselves into trees in a misguided effort for self-preservation. Since this slaughter, the Wood Queen’s spirit has been seeking vengeance upon the nearby remaining humans. While not as overt in its political messaging as Ring Shout (2020), Uprooted offers a highly folkloric look at imperialism and environmental devastation. Novik’s language is lush and vital, weaving an ecological fantasy from green and gold sentences. Her Wood teems with life and pain, both heartbreaking and terrifying.

The Ku Kluxes— (2020)

In a barely fantastical 1915, the notorious white supremacist film upon the United States. As a result, the Ku Klux Klan has transformed into multi-mouthed, quadrupedal, carnivorous demons masquerading as average white Americans—and the “Ku Kluxes” are multiplying, particularly in Georgia, the home of our intrepid heroine Maryse. Clark’s Ku Kluxes are an exercise in the grotesque, body horror at its most horrific—their lashing tongues are ridged with teeth, their many maws gaping. Part of what makes the Ku Kluxes so effective is their foundation in the physical, reflecting the real and tangible violence that the Klan has inflicted for generations upon Black Americans. By portraying the Klan as literally monstrous and physically grotesque, Clark exposes how the process of dehumanization causes the oppressor to lose their own humanity. Ring Shout is an excellent novella blending the fantastic with the historical to create a portrait of America at once familiar and uniquely horrific. Elements of Gullah root magic and resilient community offer a form of resistance and power for our heroes, bringing Ring Shout beyond the realm of simple allegory to become a fully fleshed out story of Black history and folk tradition in the American South.

Humankind discovers they can exploit the labor of a dexterous species of Newt for more efficient pearl diving. Over time, these Newts evolve into a highly intelligent and physically able species, and humans become ever more dependent on Newtlabor. Thus spawns the Newt-Human conflicts, ultimately resulting in a proletarian revolution and all-out class warfare. When the Newts claim dominance, it is clear they will seek to wipe out humanity, sparing a few for labor. They will ultimately divide amongst themselves and self-destruct, committing the same errors as their human overlords. Written in 1930s Czechoslovakia, Čapek’s satirical novel offers a scathing critique of capitalism, unethical labor practices, militarism, and imperialism. As always, the monstrous provides a warped funhouse mirror for humanity, examining the ways in which we hurt ourselves and the world around us to devastating effects. Yet still, a good monster story always expresses the nuance of human pain and destruction—in every Newt warlord there was once a gentle pearl-diver.