DAVID SHICK AND THE FORGOTTEN

LEGACY OF GEORGETOWN DAY

By Yana Gitelman

SEASON TWO OF ABBOTT

ELEMENTARY IS A MASTERCLASS IN COMMUNITY STORYTELLING

By Sagun Shrestha

By Sagun Shrestha

WORK, WISDOM, AND COMMUNITY: THE ETHOS OF THE HILL BOYS

By Nicholas Riccio

2023

APRIL 28,

BACK COVER BY GRAHAM KREWINGHAUS

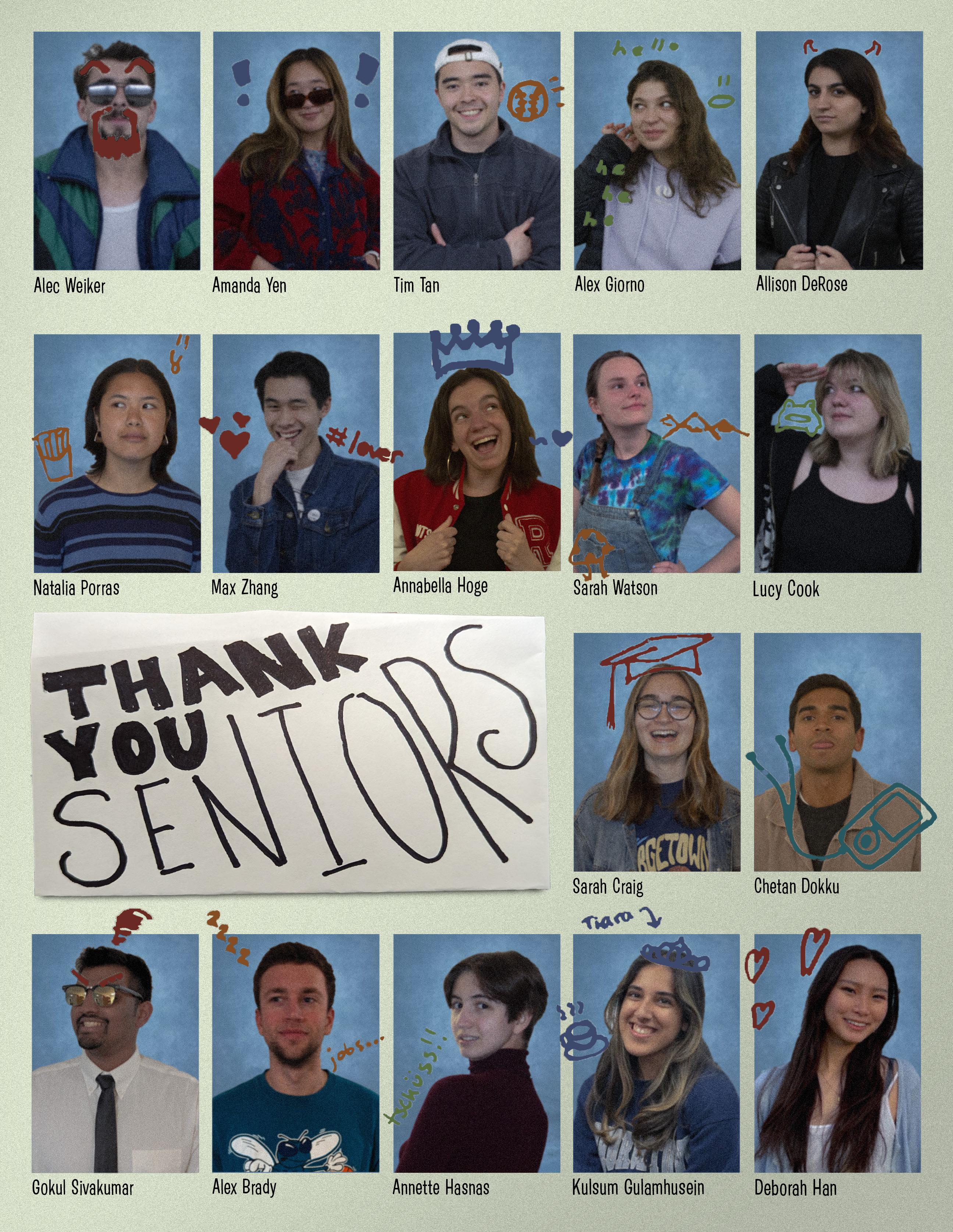

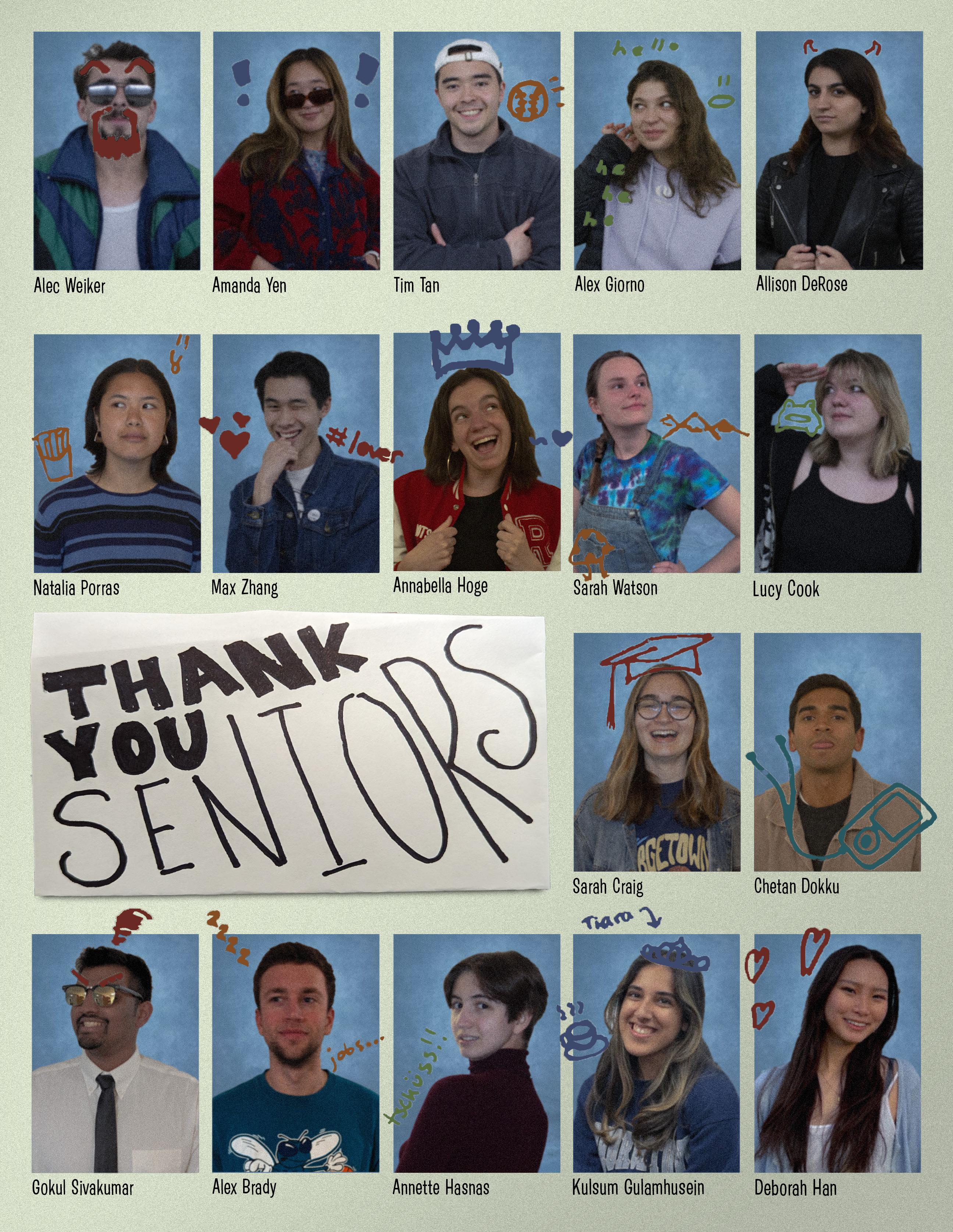

Editor-In-Chief Annabella Hoge

Managing Editor Nora Scully

internal resources

Executive Editor for Resources, Diversity, and Inclusion Ajani Jones

Editor for Sexual Violence

Advocacy, Prevention, and Coverage Sarah Craig

Service Chair Aminah Malik

Social Chair Connor Martin

news

Executive Editor Joanna Li

Features Editor Franziska Wild

News Editor Graham Krewinghaus

Assistant News Editors Yihan Deng, Alex Deramo, Amber Xie

opinion

Executive Editor Kulsum Gulamhusein

Voices Editor Lou Jacquin

Assistant Voices Editors Barrett Ahn, Ella Bruno, Andrea Ho

Editorial Board Chair Alec Weiker

Editorial Board William Hammond, Annette Hasnas, Andrea Ho, Annabella Hoge, Jupiter Huang, Paul James, Connor Martin, Allison O'Donnell, Sarah Watson, Max Zhang

leisure

Executive Editor Adora Adeyemi

Leisure Editor Maya Kominsky

Assistant Editors Pierson Cohen, Cole Kindiger, Hailey Wharram

Halftime Editor Francesca Theofilou

Assistant Halftime Editors Eileen Chen, Caroline Samoluk, Zachary Warren

sports

Executive Editor Nicholas Riccio

Sports Editor Lucie Peyrebrune

Assistant Editors Andrew Arnold, Thomas Fischbeck, Ben Jakabcsin

Halftime Editor Jo Stephens

Assistant Halftime Editors Bradshaw Cate, Sam Lynch, Henry Skarecky

design

Executive Editor Dane Tedder Design Editor Connor Martin Spread Editors Olivia Li, Sabrina Shaffer

Cover Editor Grace Nuri

Assistant Design Editors Cecilia Cassidy, Madeleine Ott copy

Copy Chiefs Donovan Barnes, Maanasi Chintamani

Assistant Copy Editors Chetan Dokku, Shajaka Shelton

multimedia

Podcast Executive Producer Jillian Seitz

Podcast Editor Livia de Queiroz Brito

Assistant Podcast Editor Romy Abu-Fadel

Photo Editor Jina Zhao

online

Website Editor Tyler Salensky

Social Media Editor Allison DeRose

Assistant Social Media Editor Ninabella Arlis

business

General Manager Megan O’Malley

Assistant Manager of Accounts and Sales Rovi Yu

Assistant Manager of Alumni and Outreach Horace Wong

support

Contributing Editors Lucy Cook, Deborah Han, Annette Hasnas, Margaret Hartigan, Tim Tan, Sarah Watson, Max Zhang

Staff Contributors Meriam Ahmad, Rhea Banerjee, Angelena Bougiamas, Elyza Bruce, Nicholas Budler, Romita Chattaraj, Leon Cheung, Elin Choe, Erin Ducharme, Nikki Farnham, Alex Giorno, Ethan Greer, Paul James, Christine Ji, Julia Kelly, Sofia Kemeny, Ashley Kulberg, David McDaniels, Insha Momin, Mia Murillo, Amelia Myre, Natalia Porras, Owen Posnett, Daniel Rankin, Carlos Rueda, Ryan Samway, Michelle Serban, Elizabeth Short, Sagun Shrestha, Lukas Soloman, Isabelle Stratta, Sophie Tafazzoli, Amelia Wanamaker, Andrew Swank, Fallon Wolfley, Amanda Yen, Nadine Zakheim

2 THE GEORGETOWN VOICE Contents contact us editor@georgetownvoice.com Leavey 424 Box 571066 Georgetown University 3700 O St. NW Washington, DC 20057 The opinions expressed in The Georgetown Voice do not necessarily represent the views of the administration, faculty, or students of Georgetown University, unless specifically stated. Columns, advertisements, cartoons, and opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the views of the Editorial Board or the General Board of The Georgetown Voice. The university subscribes to the principle of responsible freedom of expression of its student editors. All materials copyright The Georgetown Voice, unless otherwise indicated. April 28, 2023 Volume 55 | Issue 14 4 features David Shick and the forgotten legacy of Georgetown Day YANA GITELMAN 6 voices I am my father’s daughter JO STEPHENS 7 halftime sports How the NCAA is attempting to rein in the chaos of the transfer portal HENRY SKARECKY 10 news Autobots, don't roll out: Georgetown community defends Transformers sculptures ALEX DERAMO 11 halftime leisure Season two of Abbott Elementary is a masterclass in community storytelling SAGUN SHRESTHA 12 leisure “Queer chaos” returns to Georgetown with The Rocky Horror Picture Show CONNOR MARTIN 13 halftime leisure A case for the classics: But I'm A Cheerleader ZACHARY WARREN 14 leisure (no) pressure showcases Georgetown’s Asian American community and talent KRISTY LI 15 voices What happened to the movie theater intermission—and could we please bring it back? EILEEN MILLER design by deborah han; layout by connor martin

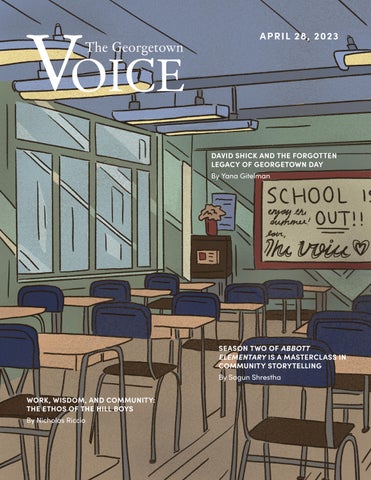

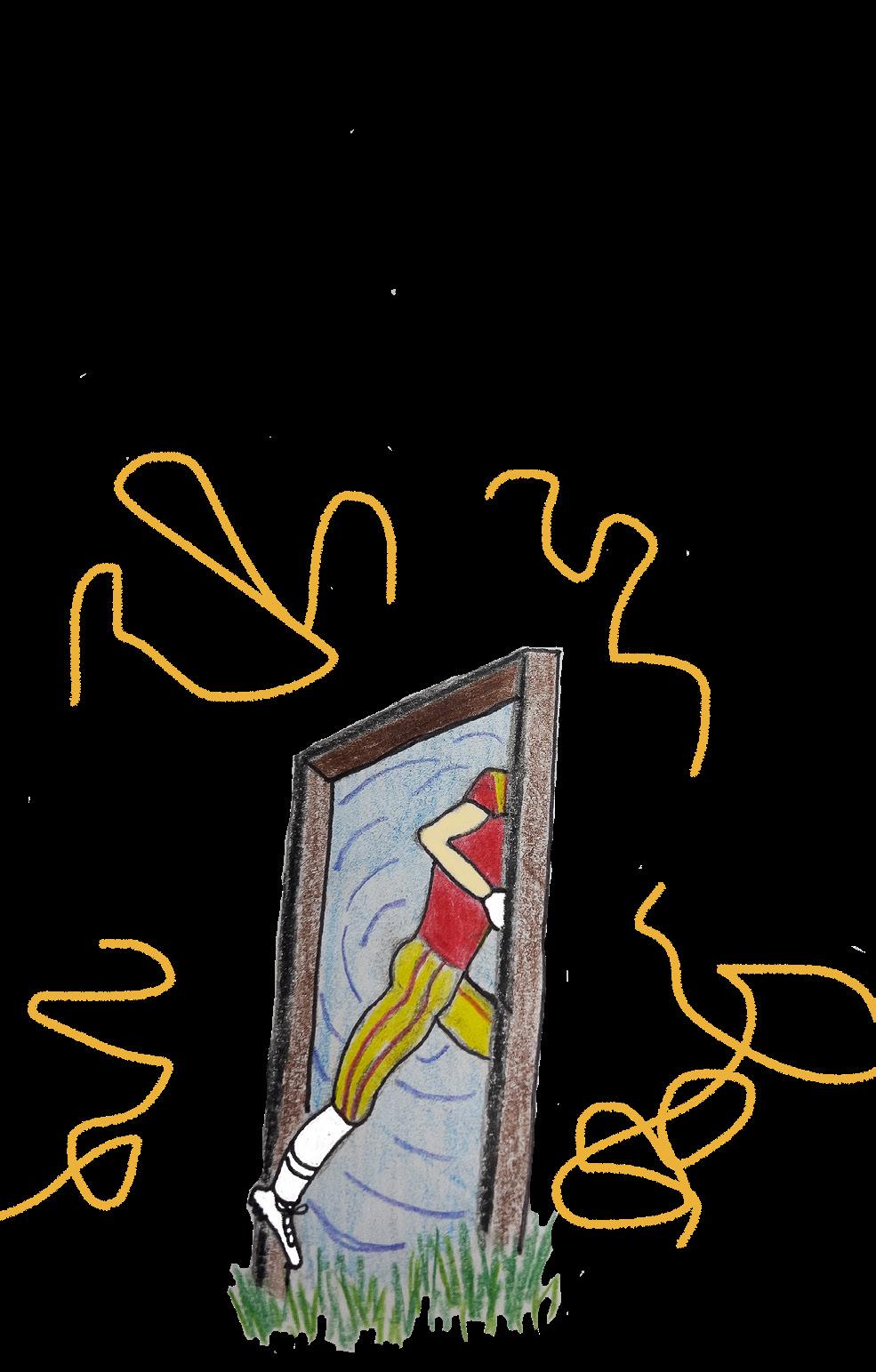

on the cover

8

“school's out” GRACE NURI

Work,

halftime sports

wisdom, and community: The ethos of the Hill Boys NICHOLAS RICCIO

PG.

"Nobody talks about grieving for someone who’s still here. Nobody teaches you how to grieve for yourself."

6

Page 3

→ LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Dear Voice readers,

I’ve spent so much time trying to do and be my best for the Voice that I actually haven’t thought much about what it’s meant to me. It’s strange, but we often don’t reflect on the places we call home until we have to leave them. The Voice has been a haven for me at Georgetown: It’s where I’ve produced my proudest work as both a writer and leader, and it has fundamentally changed how I see myself in a world where I seek to find and grow community. It has picked me up in my lowest moments, and challenged me to create a space I could be proud of.

But the Voice really matters because it means something to our community—there

→ GOSSIP

An eclectic collection of jokes, puns, doodles, playlists, and news clips from the collective mind of the Voice staff.

are people who trust us, and that means something.

Thrust upon the Class of 2023—the last class to have attended Georgetown before the pandemic—has been an ongoing conversation of institutional memory and the longevity of our work after we’re gone. On my way out, I can’t help but weigh our organization's potential to continually create an image of what Georgetown is, and can be, for each other. We tell messy stories about struggle and growth, and how we reckon with a picture of Georgetown we don’t want to look too closely at. We have the potential to build a common language among readers and writers and introduce ourselves to each other.

Most of all, we have the potential to be brave. Brave in what we ask of the people we interview, brave in our storytelling, brave in what we demand from our institution and each other, brave in allowing ourselves to feel joy alongside all of it.

In the spirit of what the Voice can be, and what we can be as a community, I suggest we all be brave. Brave in taking risks for what matters, brave in making mistakes, and brave in moving on and allowing what comes next to flourish without us. I, for one, can’t wait for what’s next for the Voice

To what’s still ahead,

Annabella Hoge Editor-in-Chief, Spring 2023

RAT → TIME IS RUNNING OUT

As you all crowd into your Vil A frat parties, your bodies swaying and thrusting this Georgetown Day, I’ll be below, watching, and sucking on the borgs leaking through the roofs and into my thirsty and gaping mouth <3 (Happy Georgetown Day from the Voice!). xoxo, Gossip Rat

Across

1. Gold medalist

5. With 1 Across, what comes after an outline

10. Hearing organ

11. Mathematician who defined e

12. Get up

14. Follow, as in law

15. Christmas dairy drink, for short

16. Long, sometimes electric fish

17. “Don’t ___ stranger” (2 words)

18. NBA’s “Beam Team”

20. Archaic word for “between”

22. Romantic interest

26. Rising mass of small bubbles

30. Sharp knock or music genre

31. Capitals great, briefly

32. Abbr. for Cape Town country

33. State in NE India

35. Left-leaning political party

37. Carrell, Austin, or Harvey

38. Bulls city, for short

39. Opposite of a lover

40. Travel with: “___ a ride”

Down

1. Honest

2. Rule, as in of royals

3. Club behind Rangila, abbr.

4. What the Lorax spoke for

5. Distributed cards

6. Magic lamp action

7. Legal excuse

8. Transport company and Commanders Field

9. What good dogs get

13. Return on investment, abbr.

19. Car fuel

21. Make love, not this

22. Collision

23. Member of Jamaican religious group

24. Underdog win

25. Simpsons donut lover

26. Hogwarts caretaker

27. Planetary path

28. General with chicken dish

29. Rough or jarring

34. Broad st.

36. Type of tuna

3 APRIL 28, 2023

"frank-n-fucker" by dane tedder; crossword by nicholas romero; clocks by shajaka shelton, ajani jones, margaret hartigan, and olivia li

→

NICK'S CROSSWORD

David Shick and the forgotten

Friday, April 28, marks the 22nd Georgetown Day. Today, Georgetown Day is characterized by daytime parties and programming to celebrate the end of classes—but underneath the revelry, the day has a tragic past most Hoyas don’t know about. Each year, university officials attempt to remind students that the day is more than the festivities it has become: It began “in 2000 as a response to a year with several painful hate crimes and the tragic death of a student involving drinking,” according to an email Georgetown Student Affairs sent to the community on April 19.

The tragic death refers to the loss of David Shick (MSB ’01) in February 2000. The incident is mythicized in the Georgetown community, with rumors attributing Shick’s death to alcohol poisoning or a bad fall down the Lauinger Library steps. Moments recalling his death, like the April 19 email, do not often mention violence. The history of Shick’s death, the nontransparent university response, and the disinformation that ensued are all important for reckoning with the meaning of Georgetown Day over two decades later.

“It was not alcohol that killed David, but a senseless act of violence,” Shick’s family wrote in a letter to the Hoya on April 26, 2000.

Shick was from New Jersey, and had friends and a girlfriend who loved—and still love—him deeply. On Friday, Feb. 18, 2000, Shick and his friends were returning to campus from a sports bar, Champions, at 2:30 a.m. They ran into a group of men’s soccer players in the library

parking lot, and a physical altercation broke out after Shick and one of the athletes bumped into each other.

“There was just an exchange of hubris, you know, ego, like what the heck? Swears being thrown around: ‘Why'd you bump me?’” Erin Flynn (MSB ’01), Shick’s girlfriend, said. “The first punch came from [the perpetrator], as an uppercut to Dave. So, like, knocked him back off his stability and he fell back and hit his head, like the base of his head on a curb that was in the parking lot.”

Witnesses quoted in Hoya articles from the time describe a horrific scene in which Shick was abandoned by his attackers. “A lot of people took off,” an anonymous witness recounted to the Hoya GUPD then arrived at the scene minutes after a 911 call placed by a passing pizza delivery driver. Shick was sent to MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, where he passed away four days later, on February 22, 2000.

“I didn’t think he was going to die,” Flynn said. “He was taken from us far too soon and he was a person with so much promise. Where would his life have gone? Would he and I have gotten married?”

The two students who assaulted Shick—one who threw the first punch and another who was involved in the altercation—leading to his death received no legal repercussions and nearly no sanctions on campus. In the end, the main perpetrator only had to write a short reflection paper. Their names were never publicized thanks to the university’s privacy policy.

Shick’s cousin, Tiffanie Benfer, who then worked at Georgetown as judicial coordinator and assistant director of student conduct, recounted that within minutes of Shick’s death, one of her coworkers in the hospital began asking questions about who threw the first punch.

“Basically saying he had a role in his own death,” Benfer recounted.

“A person lost his life. A family will never be the same. Two parents lost their child. A brother and a sister lost their brother. All these people who loved Dave lost a loved one. That got lost,” Flynn said. “Instead, it became all about covering up and protecting the reputation of the university and of the two students who were responsible.”

What ensued was a lack of university communication about the true nature of the incident, leading to a series of misconceptions about Shick’s death—among them that he was a frequent heavy drinker. “There was then this whole slandering that went along with that of character witnesses painting him out to be a drunken, belligerent, bar-going type of guy who was predisposed to this type of behavior. And that just simply wasn’t true,” Flynn said.

These misconceptions and gaps of knowledge around Shick’s death led student media outlets to fill in these gaps in a way that highlighted a passive narrative—focusing on his fall—rather than an active one that retained culpability.

“A Georgetown junior died Tuesday afternoon after sustaining a head wound from a fall in the Lauinger library parking lot,” a Hoya article from 2000 wrote, noting that “alcohol was involved.” Furthermore, while articles from the time mention that Shick “sustained injuries,” none explicitly wrote that such injuries were the direct result of another student.

The coverage of Shick’s death in the Voice was even more limited than in the Hoya; while the Voice wrote several substantive articles about the university’s response in 2002, the publication failed to substantively cover David’s death in 2000.

Two years later, after a similar violent incident brought comparisons to Shick’s case in student publications, former professor Colin Campbell wrote a letter to the Hoya alleging that the GUPD officers at the scene allowed remaining witnesses to disperse without taking names or statements and immediately declared the event an accident.

design by dane tedder

4 FEATURES THE GEORGETOWN VOICE

forgotten legacy of Georgetown Day

BY YANA GITELMAN

In an attempt to investigate Campbell’s claims this year, the Voice reached out to GUPD for information.

“This happened 23 years ago,” Frank Rosenberg, a current GUPD detective, told the Voice. “We don’t have any records and they haven’t maintained records from that long ago.”

GUPD’s evidence retainment has remained a problem; recently, evidence was lost in the investigation of the hate crime committed against LaHannah Giles (CAS ’23) due to what GUPD and university administrators described as an “unexpected server failure.”

According to a university spokesperson, “Georgetown University complies with all relevant federal and local laws and requirements and cooperates with law enforcement on criminal matters. In this case, the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) and the U.S. Attorney’s Office conducted the criminal investigation. GUPD provided its confidential incident report to the lead investigatory agencies.”

The lack of accessible documentation makes it difficult to verify Campbell’s claims. This dearth of publicly available information from GUPD and MPD further creates misconceptions about what happened, thus misconstruing Shick’s story in the collective memory.

MPD forwarded the case to the U.S. attorney’s office, as is procedure when someone dies. After a two-week-long grand jury hearing, the D.C. prosecutor decided not to pursue prosecution. “[The prosecutor] said we can’t pursue it because of the level of alcohol that was involved, the credibility of the witnesses has been diminished,” Flynn said.

“If you’ve got alcohol involved, it makes it harder to go after cases … because you have to demonstrate intent,” Benfer said. The family has, thanks to the court proceedings, become somewhat of an expert in the field; Benfer is now a lawyer.

Although no criminal proceedings arose, Georgetown still had to settle the case internally through student disciplinary action. When a student is charged with a grave disciplinary matter, their case goes before a hearing board composed of three undergraduate students and two faculty members, which decides whether a student is responsible based on a “clear and convincing standard.” If found culpable, they are then sanctioned by the Office of Student Conduct (OSC).

The OSC initially planned to bar Shick’s parents from attending the hearing, but eventually

allowed them to sit in. They were, however, not allowed to obtain legal counsel to represent them in this process and had little to no influence over the hearing.

“That was back then, you had no say in it at all,” Benfer said. The student who was involved in Shick’s death obtained the legal defense of David Schertler, a prominent criminal defense attorney in D.C., and brought him to the campus hearing.

After the summer 2000 hearings concluded, the university used a nondisclosure policy that manifested as an ultimatum for Shick’s parents: To gain any information about the outcome of the case, they could sign a confidentiality agreement, or not sign and be left completely in the dark.

The Shicks declined to sign the agreement. “It wouldn’t let us share the information with David’s brother and sister,” Shick’s mother, Debbie Shick, said in a 2002 interview with The Daily Pennsylvanian. With Matthew Shick (CAS ’04) set to begin at Georgetown in the fall, the family balked at the prospect of him being unaware of whether his brother’s assailant would be one of his peers.

The Shicks chose not to sign the confidentiality agreement but filed a civil lawsuit against the perpetrator. It took 18 months and extensive legal fees for the family to gain basic information about the administration’s response to their son’s death. “One of the tragic things is that to get any information, we had to file a suit. As parents of the victim, we are not entitled to any information,” Jeffery Shick told the Voice in 2002.

The Shicks discovered that the OSC hearing board had found the perpetrator guilty of underage drinking, disorderly conduct, and physical assault with bodily injury. The perpetrator initially received a semester-long suspension, along with a 10-page reflection paper and an alcohol evaluation, until the assailant’s lawyer appealed the suspension. The final sanction was the reflection paper and a “suspended suspension,” meaning the perpetrator would have to serve the suspension only if he failed to write the paper.

Georgetown cited the Family Educational Rights and Protection Act (FERPA) in justifying their lack of transparency. “Protecting the confidentiality of student information not only is intrinsic to the educational mission of Georgetown’s student disciplinary system, but also is required by federal law,” the 2001 policy on OSC hearing disclosure reads. FERPA states that universities could—but were not obligated to—release information about violent crimes on campus.

The Campus Justice website, created by Mike Haynes, a childhood friend of Shick’s, breaks down this FERPA policy: “Because of the way it is worded, school officials use FERPA as justification for non-disclosure, noting that while it permits them to disclose this information it does not require them to do so.”

“The climate of secrecy surrounding disciplinary hearings combined with non-disclosure policies and confidentiality requirements allows colleges and universities to manipulate the process in order to preserve their reputation,” Debbie and Jeff Shick wrote in a released statement on Nov. 20, 2000 regarding the university hearing’s results and restriction of information.

This level of privacy, however, was not unilaterally applied to other cases at the time. Just months earlier, Michael Byrne (MSB ’02) had vandalized the Jewish Student Association’s menorah while intoxicated. Despite FERPA policy, the Hoya published Byrne’s name in several articles.

During the 2022-23 school year, discussions of Shick’s connection to Georgetown Day have resurfaced, partially because of the similarities between both the handling and timing of the hate crime that Giles survived on last year’s Georgetown Day. Her perpetrator faced no sanctions and remains unnamed. Many administrators who were at Georgetown at the time of Shick’s death are still here 23 years later.

Shick’s story raises questions about how members of the Georgetown community treat one another and what our communal response to violent incidents looks like. Shick did not die of alcohol poisoning or an alcohol-induced fall. Honoring his memory requires understanding and acknowledgement of the violence that caused his death, and a commitment to prevent and respond to violence moving forward.

“I want people to know the real story that you’re telling. I want people to know who Dave really was, not who he was painted out to be,” Flynn added. “I want the university to know that I love Georgetown for so many things. But they did us a disservice. They picked the wrong path in this, in this scenario, and I hope that they don't do it again.” G

This article is based on research conducted by Yana Gitelman and Max Paley (CAS ’23) for the podcast Hidden Truth: The Death and Legacy of David Shick.

5 APRIL 28, 2023

I am my father's daughter

BY JO STEPHENS

W hen I was a sophomore in high school, I misspelled my name on the PSAT. I didn’t notice until my proctor pointed it out. I had left the “a” off the end of my name, calling myself “Joann” instead of “Joanna.” My mom and dad laughed when I told them about it that night. My mom called me silly.

I don’t think about that moment often, but when I let myself dwell on it, I can’t help but think it might have been the beginning of the end.

***

This is a story about my dad, and about me too—but it starts with Joann, the original one. She was my paternal grandmother who died when I was a baby. I don’t have any memories of her, just a handful of stories and a passed-down name. She had dark hair. Her maiden name was Beach. She had early-onset dementia.

She didn’t know the truth of her condition in her lifetime. Nobody did. When she was about 50, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia; it wasn’t until years later, after my dad got sick, that we realized she’d never been schizophrenic. It was dementia all along. Schizophrenia runs in families, so it worried my dad, but as time went on and he stayed the same, he stopped being so scared. He thought he was in the clear.

He was wrong.

***

His symptoms began after a minor surgery when he started talking about things that weren’t there. We attributed his strange behavior to the anesthesia, believing that he would bounce back to himself after it wore off.

But he never stopped seeing those things. He believed with his whole heart that his perception was the right one and that everyone else was lying to him. He felt, I think, as if he was the only person seeing things clearly, and the rest of us were gaslighting him, when in reality the opposite was true.

It took us a while to figure out what was happening, but by the time I was a senior in high school, we had a diagnosis: early-onset dementia.

It started when he turned 50. Like mother, like son.

***

Selfishly, the thing that’s taken me the longest to reconcile is that my future very well might look the same. I am my father’s daughter, whether I want to be or not. I cannot fight biology.

I’m so much like him that it startles me sometimes. Our laughs sound alike. I love to cook just as much as he did, even though neither of us has ever been good at it. We like the same flavors of ice cream. Every Carolina football game echoes with his commentary I never understood but do now; every basketball piece I write reminds me of when he was my coach in eighth grade. He’d stay behind after

practice to let me do extra drills, or shoot free throws, or run sprints, because I wanted to be better and he didn’t have the heart to tell me that I was probably always going to be terrible. I have his father’s eyes. I have his mother’s name. One day, I might have his degenerative brain disease. I am my father’s daughter. ***

As much as I’d like to say I’ve taken this whole thing in stride, the truth is, I haven’t. I’ve taken it hard. I can’t shake the feeling that 30 years from now, my brain will start to disintegrate, and my identity will slip away until I’m some washed-out, hollow version of myself. I think about it constantly.

Nearly every decision I make, especially the big ones, is tainted by the idea that I’m running out of time. When I was in high school, I wanted to go to law school. I’ve given up on that now because spending another three years in school when I might only have 30 good ones left feels unjustifiable. Long-term plans feel like a countdown. Whenever I go home, I struggle to spend time with my dad, because every time I look at him, I feel like I’m looking at my future.

What I’ve really been doing the past few years is grieving, but it’s a peculiar kind of grief, one that stands apart from other experiences of mourning.

Nobody enjoys talking about grief—but

grieving for someone who’s dead is at least typical. It’s acceptable.

Nobody talks about grieving for someone who’s still here. Nobody teaches you how to grieve for yourself.

So that’s what I’ve been trying to do: I want to make space for these feelings without letting them suck the joy out of my life. And it’s a really challenging thing to do because it’s such an isolating existence. I’m the only college kid I know whose dad has dementia. Most of the people in my shoes are grown adults, with careers and children of their own. Their parents are older. All of my friends are lovely, but none of them understand how this feels. They can’t relate.

I’m 20. My dad is 56. Most people don’t get diagnosed with dementia until they’re 65; we’re ahead of the timeline, and that’s lonely. But I have to believe that somewhere out there, there’s someone who feels the same way I do, who walks in the same shoes as me, who can read this and know that while we might be lonely, we aren’t alone. That there’s someone who gets it.

There isn’t a lot of hope in this story. But that’s why I wrote this in the first place. Because sometimes, there is no silver lining. Sometimes, things just really fucking suck.

I’m trying my best to make peace with that. ***

My dad told me one time that his favorite thing about me was that I was fearless. For the past few years, I haven’t felt that way. I’m more terrified than anything these days, and that fear makes it hard to look in the mirror sometimes. I can’t help but wonder how different I’d be if he’d never gotten sick, or if I’d just been a few years older when he did. Maybe I’d be braver—or maybe this has made me brave, and I just can’t quite see it yet. I am my father’s daughter. I am trying to learn that there are far worse things to be.

6 THE

GEORGETOWN VOICE

VOICES

G

design by olivia li

How the NCAA is attempting to rein in the chaos of the transfer portal

BY HENRY SKARECKY

"Let’s not make a mistake: We have free agency in college football.”

Lane Kiffin, the head football coach at Ole Miss, famously uttered those words to describe the massive shift that the transfer portal has brought to the world of college sports. The transfer portal—a database that streamlines the transfer process for college athletes—has transformed the offseason from a time originally focused on recruiting high schoolers to a chaotic battle between schools trying to woo some of college sports’ most established athletes.

Currently, around 1,400 men’s basketball players, 1,000 women’s basketball players, and 2,000 football players have entered the transfer portal this offseason in Division I, representing over 20 percent of scholarship athletes in each respective sport. A decade ago, the percentage of athletes transferring was in the single digits. In the modern era of college sports, student athletes regularly transfer to find better playing opportunities or to follow a coach to a new

Ewing’s tenure, with the entire roster, save for two scholarship players, transferring after the 2021-22 season. The women’s team has not been unscathed by the portal, either, with BIG EAST Freshman of the Year Kennedy Fauntleroy announcing that she intends to transfer.

Coaches, university administrators, and NCAA officials are beginning to criticize the new normal of frequent roster changes brought in by the portal. Research conducted by the NCAA reveals that athletes who transfer schools are less likely to earn a degree. In addition to recruiting athletes out of high school, coaches and scouts now have to pay attention to a larger volume of collegiate players, stretching recruiting resources thin. Student athletes who enter the portal but do not find a new school are at risk of losing their original scholarships. As such, the NCAA is now trying to retroactively diminish the chaos.

How did we get here?

The current chaos is the product of a halfdecade’s worth of changes by the NCAA to make transferring between institutions less of a headache. Before the transfer portal, athletes wishing to transfer would have to seek permission from their coach before contacting other schools— and no coach wants to lose a star player. Once a student athlete finally transferred, they would be forced to sit out for an entire season or to request that the NCAA grant a waiver allowing them to be immediately eligible to play.

The transfer process was forever changed in 2018 with the introduction of the NCAA Transfer Portal, which has come with its own set of rules. Student athletes no longer need their coach’s permission to transfer, and in 2021, the NCAA enacted its most powerful portal-related legislation yet when it decided to allow immediate eligibility for a student athlete’s first transfer without having to request a waiver. In addition to immediate eligibility being universally granted to all first-time transfers, it also became the norm for the NCAA to grant waivers to players who transfer more than once.

A well-known example is Rice University quarterback J.T. Daniels, a senior who will start for the Owls this fall. Rice will be the fourth school Daniels has played for in his collegiate career, having previously started for Southern California, Georgia, and West Virginia. Athletes like Daniels are increasingly common in this era, as the NCAA’s easing of transfer rules has created opportunities for players to jump between multiple institutions in search of more playing time.

released new guidelines in March restricting the reasons for approving a waiver for an undergraduate student athlete transferring for the second (and third and fourth) time. The new legislation explains that the NCAA will only grant a second-time transfer waiver for physical and mental health reasons. It also explicitly states that changes in playing time, as well as coaching changes, are no longer valid grounds to grant an eligibility waiver.

Furthermore, the NCAA has enacted strict transfer portal windows when the transfer process must take place, in order to ensure the offseason is not solely dedicated to recruiting transfer talent.

These measures are already in effect for athletes playing in the 2023-24 competition year, but the effects of these changes are yet to be seen. This is partly attributable to coaches and the media not believing that the NCAA will strictly enforce the new restrictions. If, however, the NCAA does begin to regularly deny immediate eligibility for two-time transfers, the number of players in the portal should decrease as student athletes will have to decide between staying at their current school or giving up a year of eligibility if they transfer.

The debate over the freedom to transfer has been heated on social media, with many arguing players should be allowed to follow their coaches to new programs as well as pointing out that non-student athletes face little to no restrictions when transferring schools.

The NCAA transfer portal is more of an art than a science. Its rules change multiple times a year, and the final say on a player’s transfer eligibility is left to a committee that evaluates waiver requests on a case-by-case basis. Despite the NCAA’s recent attempts to curtail the chaos wrought by transferring athletes, the transfer portal is here to stay and is likely doomed to continue being a topic of heavy debate for years to come.G

7 APRIL 28, 2023 HALFTIME SPORTS

design by cecilia cassidy

Work, wisdom, and community: The ethos of the Hill Boys

BY NICHOLAS RICCIO

It was October of 2020, and the world was still eerily quiet: a silent summer broken only by the two-minute serenade of pots and pans for the frontline workers at 7 p.m., with everyone stuck at home in their COVID-19 “pods” filling up the days with whatever they could. Marquis Grissom Jr. and his friends were no different.

“I mean, we were like everyone else,” he said. “Just trying to find something to do while we waited for the world.”

Marquis was 18 at the time, and the COVID-19 pandemic had delayed his matriculation to Georgia Tech, where he would excel as a pitcher and eventually become a Washington Nationals draft pick in 2022. But that was all in the future. For now, he was part of a group of eight up-andcoming baseball players from the metro Atlanta area that, with the help of Grissom’s father, had come to Fayetteville, Ga., to train. They were the inaugural “Hill Boys,” who, along with their three coaches, created a space for Black players with an ethos built on three tenets: hard work, imparting generational wisdom, and community.

From the very beginning, they would see just how much work they would need to put in. At the start of the first practice session, they were faced with a hill—literally. The hill wasn’t particularly steep, so craning your neck to see the top wasn’t

necessary. But it was big: the size of an entire baseball field featuring a solid incline. One lap around the hill routinely left a myriad of Hill Boys splayed out on the grass, clutching their stomachs.

For the players, this was their first time getting acquainted with the hill, a spot that became their training ground for their pre-spring training workouts. But Marquis Grissom Sr. was deeply familiar with the hill, and the image is just as striking as when he first saw it years before.

The 17-year MLB veteran knew he found his piece of heaven in 35 acres of land in Fayetteville in 2004. But he also knew his family would want to live somewhere busier, so he turned it into a training facility, nicknaming it “The Hill.” The name pulls double duty. It describes the literal hill that defines the workout sessions, but it has also become a place of refuge for the next generation of Black baseball players, a group shepherded along by the older generation: three former MLB players—Marquis Grissom Sr., Marvin Freeman, and Lou Collier—with immense wisdom to share.

The Hill treats everyone the same way. Freeman, who played college baseball at Jackson State, knows plenty about exercising on hills; his university’s most famous alumni, Walter Payton,

State Tigers, so when Freeman describes players languishing on The Hill, this is his area of expertise. The Hill leaves people drenched in sweat, fumbling for water, trying to catch a quick break, every time. Seriously, every time. But, as Freeman told the Voice , “If you ain’t bent over, gasping for air, with a cramp in your side, saying you can’t go anymore, then you’re not putting the work in that’s necessary to make the kind of advancements that we’re looking for you to make.” These are the expectations when you’re a Hill Boy.

While Grissom Sr. and Collier work with the position players, Freeman works with the pitchers. The trio of veterans are passing along their knowledge at a unique point in baseball history: This is an era dominated more by numbers than anything else, but Freeman does not believe that numbers should be the only method for training.

THE GEORGETOWN VOICE design by deborah han; layout by olivia li HALFTIME SPORTS

His signifier is not numbers on a device. It’s his baseball eye.

“I have the eye to recognize if a slider is flat versus one that has got some bite on it,” Freeman said. “So I don’t need to look at the iPad after every pitch. Just having veteran pro players overseeing these up-and-comers with the ability to give on-the-spot, instantaneous advice that they can apply immediately is rare. You don’t see it anymore.”

“Now you got guys saying they’ll break down the analytics and meet in a day or two,” he added.

For a teacher like Freeman, that lost time is unacceptable. When you have four to six weeks in the lead-up to spring training, every minute counts. If he notices a flaw, he wants to fix it. Immediately.

This is all part of the “tried-and-true” method of teaching that constitutes the Hill Boys ethos. These aren’t old-school tactics, according to Freeman. “Baseball has been the same for 130 years. As long as a pitcher’s job is still to get outs, as long as the mound is 60 feet, six inches from the plate, it’s the same,” he said. So why not use the methods that have already worked?

Freeman points to his pre-spring training regimens as a member of the Atlanta Braves as a catalyst for success. When he was traded to Atlanta in 1990, pitchers were strongly encouraged—"It’s not mandatory, but you better be there”—to attend a three-week pre-spring throwing program with legendary pitching coach Joe Mazzone. Freeman’s career took off after he began annually participating in this program that would have him throwing at his top speed with full control by the time spring training began. This extra effort would help him set a club record for the Colorado Rockies with a 2.80 ERA in 1994, a record that stands today. Freeman believes that some of his success stemmed from being fully ramped up for spring training, and he’s brought that mentality to the Hill Boys.

This, like just about every other tale of the Hill Boys, is steeped in personal history.

Three years in, the teaching trio of Grissom Sr., Freeman, and Collier have already put the Boys on the path to success. Take Michael Harris II, for example. The self-described “tried-andtrue” coaching style turned Harris into one of the most exciting young players in the MLB and last year’s NL Rookie of the Year. He plays for the Braves, carrying on the legacy of both Grissom Sr. and Freeman. His impact on the team, from his excellent hitting to his absurd catches in the outfield to his expressive headbands, all showcasing his particular showmanship and ability, makes him one of the most entertaining athletes in baseball. He credits his on-field success to the Hill Boys.

Jaylen Nowlin, another Hill Boy who currently pitches in the Minnesota Twins organization, recounts Grissom Sr. talking up Harris before he even debuted, declaring he would be dominating the bigs in no time. Grissom Jr. remembers this moment as well. “My dad, during COVID, said that Mike would take over the Braves outfield

in two years. We all looked at him like he was crazy,” Grissom Jr. recalled. “Fast forward two years and he’s winning Rookie of the Year.”

To succeed at this level, this community hinges on love.

The Hill Boys love the hard work, the history they share, and, mostly, the game they play. The Hill Boys are rooted in classic Little League traditions: old teams, plastic trophies, dirt fields, and early wake-up times, building lasting, unbreakable friendships.

Grissom Jr. met Harris II and up-andcoming A’s prospect Lawrence Butler when he was eight years old at Sandtown Little League, and has known Nowlin since birth. The rest of the original eight met each other through travel ball. As kids, they all had dreams of the big leagues, and it's already becoming reality. The guys can see the brass ring, now they just have to reach for it.

of the importance of developing a safe space for Black kids to train and excel at baseball.

The original group of eight Hill Boys is just the first of many generations of Hill Boys to come. As more and more Black players join the fold (including big names like Chandler Simpson, Tink Hence, Jordan Walker, and Marc Church), the community continues to grow. But not just anyone gets the opportunity to work with the Hill Boys. “It’s something that’s voted on by all the guys that are there, the guys that understand how someone’s personality is,” Freeman explains. “If you’re coming here to work, they’ll give you that opportunity.”

The expansion continues to inspire Nowlin’s work ethic. “We’re competing against each other in drills just to see who can get done fastest. So the more people that want to work the better,” he said. Grissom Jr. used almost identical verbiage to describe his Hill Boys experience. As the group has expanded its talent pool, it’s also expanded its efforts in the community. This past November, the Hill Boys hosted their first Thanksgiving camp through Grissom Sr.’s baseball association. Kids who saw Harris II win Rookie of the Year got to listen to him—along with the rest of the Hill Boys and coaches—give instruction on the game they all love.

The kids may just be having fun, but Freeman sees the deeper impact, too: the influence of the Hill Boys on the next generation of ballplayers.

“Just having this group, with Mike leading us off, he’s going insane,” Grissom Jr. said of his best friends. “And he’s right here with us everyday, so we all know it’s possible to get to where we want to be.”

When a tree is uprooted, it dies. The same goes for human beings: We need roots. That’s what makes a strong community important. That’s what makes the Hill Boys important. In a sport dominated by analytics, statistics, and numbers, it is easy to forget the human element of baseball. The hours of practice, the importance of chemistry—these are people that have friendships over a decade old, from all across the state, with bonds created through countless hours in the dugout. Even when they spread out across the country when the season begins, the roots fostered on The Hill keep the Boys together.

It’s been only six months since the conclusion of a World Series that embarrassed Major League Baseball. For the first time in 72 years, it was played without a single American-born Black player. The participation of Black players in the MLB is at its lowest since the 1990s, and those involved with the Hill Boys are all cognizant

“I was talking to a kid a couple years ago about Ken Griffey Jr. getting elected to the Hall of Fame,” Freeman recalls. “The kid said, ‘Who’s Ken Griffey Jr.?’ That helped make me realize the importance of getting these kids into baseball and bridging the gap.” And that’s what the Hill Boys are doing. “The Hill Boys are the next generation, and we introduce them to the kids to show that these are the guys that are doing what you want to do, where you want to be. They will bridge the gap, and then down the road the next generation of Hill Boys can bridge the gap.”

He would love nothing more than to see a huge influx of Black participation in the major leagues—players with the same passion, hunger, and desire as the current crop of Hill Boys. But he thinks it may not happen in his lifetime. So instead, he focuses on the macro view: getting kids involved at a grassroots level. Nowlin and the rest of the Hill Boys share Freeman’s desire to give back. “Me and the original eight, we’ve already had discussions about our dreams of just coming back, and everybody setting up shop, but all of us working together,” he said. Through the Hill Boys, more Black kids are getting the opportunity to play and excel at baseball. That’s the vision.

At that point, when those kids decide to pursue the dream of making it to the show, they’ll be like many of the current Hill Boys. “We all have the same goal, we all want to get to the same place,” Grissom Jr. said. Where they’re trying to get to is the majors, the pinnacle of baseball. Some have already made it to the top of that hill, and the rest are raring to go. G

APRIL 28, 2023 9

"The Hill Boys are rooted in classic Little League traditions: old teams, plastic trophies, dirt fields, and early wake-up times, building lasting, unbreakable friendships."

Autobots, don't roll out: Georgetown community defends Transformer sculptures

BY ALEX DERAMO

The towering Transformers sculptures on Prospect Street, NW, are facing an old foe from 2021—a three-person federal board determined to get rid of them. The Old Georgetown Board voted (again) on April 6 to remove the Transformers after having granted them a six-month reprieve due to public interest, citing them as incompatible with Georgetown’s historic character.

The decision has been wildly unpopular with Georgetown students and community members, many of whom have offered an outpouring of support in the form of flowers and letters left in front of the sculptures, as like them and be drawn to them.

And I said to myself, ‘Why don’t I take some of them and put them outside?’”

Despite the overwhelming community support and appreciation for the sculptures, some disgruntled neighbors view the sculptures as a nuisance and a magnet for unwanted crowds and tourists. Howard expressed his frustration with these objections, which seem to have taken priority over the feelings of the rest of the community.

“Our basic core values should be about welcoming people, not rejecting neighbors, visitors from outside of town and from outside of our neighborhoods. And we don’t want to show we don’t want them around and they’re really disturbing us,” Howard said. “It’s alarming that I live next to neighbors who

The Transformers first faced opposition two years ago from the Old Georgetown Board, a federal board led by a three-person panel of architects. According to their website records, the board primarily reviews concepts and permits for buildings, additions, or renovations to determine if they preserve and protect the purported historical character of the District.

In 2021, the board reviewed the sculptures after they were installed without a permit and found the Transformers to violate their criteria, according to a statement from the secretary of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts,

“In terms of guidelines, the Old Georgetown Act is extremely vague, and it describes the purpose for the review as being authorized ‘in order to promote the general welfare and to preserve and protect the places and areas of historic interest, exterior architectural features, and examples of the type of architecture used in the National Capital in its initial years,’”

But to Howard, these guidelines are insufficient to merit the Transformers’ removal. “[The Old Georgetown Board] doesn’t have any guidelines or anything published or otherwise available,” Howard said. “To me it’s just an opinion of a group of people that don’t even know what the heck

Jenkins expressed that the overwhelming community support for the statues she’s seen through the petition alone should play a greater role in deciding the Transformers’ fate.

“I think it’s pretty unfair that three people kind of get to have a say when obviously there’s hundreds of people who are in support of the Transformers,” Jenkins said. “So hopefully they’ll just be more willing to listen to people

in the neighborhood who are saying like, ‘We actually really do love these and we would hate to see them taken down.’”

To Jenkins, the sculptures bring the neighborhood an element of originality that should be encouraged instead of blocked.

“This is a really traditional, historic kind of neighborhood. But I think when someone comes in and wants to bring that diversity, that different sort of art, I think that’s something that should be welcomed, especially if they’re doing it in a way that is safe and that’s not dangerous or risky to anybody else,” she said.

The sculptures represent a piece of art that

worthwhile.”G

10 THE GEORGETOWN VOICE design by madeleine ott

NEWS

Season two of Abbott Elementary is a masterclass in community storytelling

BY SAGUN SHRESTHA

Season two of Abbott Elementary does not disappoint. Everything that garnered praise for the first season has held true for the second as it retains all the charm and humor that made it so popular in the first place—and deserving of all 46 (46!) awards it has won in its less than two-year run.

The hit sitcom, hailed as revolutionary, broke barriers not only in terms of casting but also the story it chose to tell. A diverse cast composed primarily of leading ladies and dynamic Black characters tells the tale of a public school and all its woes without sugarcoating the tangible issues they routinely face, including underfunding, poor accessibility, broken facilities, and a general lack of necessary resources.

In real life, these problems are nothing new. Quinta Brunson, the creator of Abbott Elementary who plays second grade teacher Janine Teagues, said in an interview that the show was partially born out of seeing her own mother’s experience as a schoolteacher, and the authenticity of the narrative shines through.

“My mom was a teacher for 40 years in the Philadelphia school district. I was a Philadelphia public school student for most of my, you know, years,” Brunson told ABC Audio. “I rode to school with her in the morning. I stayed with her after school.” From her mom, Brunson heard about every detail of every decision being made “that was going to make her job a little bit harder that year.”

Barbara Howard (Sheryl Lee Ralph), the show’s kindergarten teacher, was modeled after Brunson’s mother. And the students in the show reflect an actual Philadelphia classroom both in terms of their diversity and use of Philly slang. The audience is brought right into Abbott Elementary, aided through the mockumentary style of filming.

Season two of Abbott Elementary starts off with a peek into Janine’s apartment as she tries to get over her breakup with her rapper exboyfriend Tariq (Zack Fox). It’s a new start for both Janine and the show as the first season was primarily confined to school grounds. Now the camera follows Janine at home and driving to school, alluding to how much more personal the rest of the season is going to be. The workplace mockumentary has transformed into something more as it begins to capture scenes of home life and family drama.

The inclusion of after-school hours doesn’t detract from the show’s original storytelling goals. Yes, it’s about a school first and foremost, but now the characters are more fleshed out and relatable, leading to a greater understanding of

the people that make up this institution. What truly is a school without its teachers and staff?

The expanded perspective allows the show to dive deeper into its main cast, expanding from the more two-dimensional traits from the previous season. Whereas season one establishes the vague caricatures the characters are based off of—Janine, the bubbly rookie teacher whose enthusiasm knows no bounds; Barbara, the wise, matronly veteran teacher; Melissa Schemmenti (Lisa Ann Walter), the hot-headed, outspoken teacher; Gregory Eddie (Tyler James Williams) who puts discipline and order above all else; Jacob Hill, (Chris Perfetti) a classic woke white millennial; and Ava Coleman (Janelle James) whose side hustles and internet stardom prevent her from performing her job as principal— season two takes a dive into their backstories, establishing the parts of them that they may not show while at school.

It turns out that Janine can crash and fall after her breakup, shattering the optimistic and overly positive face she tried so hard to cultivate. Her complicated family issues are revealed when her sister Ayesha (Ayo Edebiri) comes to visit, and an argument unfolds about Janine feeling left behind when Ayesha moved to Denver. Janine also is able to say no to her exuberant mother, who had only come to ask for money. In the end, she learns to be a little selfish, most notably with Gregory whom she rejects in the season finale, despite their ongoing “will-theywon’t-they?” throughout the entire show.

Janine and Gregory’s relationship was highly anticipated, with much of the show’s media coverage exclusively focused on the potential romance. However, boiling down the second season of Abbott Elementary to just their romantic attraction completely disregards the heart and soul of the show: the community itself. Despite how various media outlets portray it, romance is not at the center of this show; it’s a masterfully crafted subplot at best, and only serves its purpose to demonstrate the aforementioned character development. It’s not the romantic relationship itself that matters, but rather the other relationships it fosters, either through friendships formed under the pretense of gossiping about it (like Ava and Melissa who mock the two “lovebirds”) or the friendships necessary to talk through it (such as Gregory and his confidant Jacob).

In some ways, Janine may be considered the primary star of the show, but the key to her growth lies in everyone around her, from the students to the rest of the teachers. It truly takes a village. Even though the episodes feel somewhat formulaic in that there is almost always some issue with Janine (or a younger teacher like Gregory or Jacob) that gets solved after a deep conversation with one of the older teachers (Barbara or Melissa), there is still instant gratification when a conflict gets wrapped up in 25 minutes every week—it is the nature of the sitcom genre, after all. This structure also lends further authenticity to the show and helps humanize the veteran characters, who are later shown messing up, too. It’s what makes Abbott Elementary so special, because just watching the show feels like being in the school itself, learning life lessons right alongside the students and teachers.

If I had to give the second season of Abbott Elementary a grade, it’d be an A from me. G

HALFTIME LEISURE

design by tina solki

APRIL 28, 2023 11

The ICC auditorium is many things— including my final resting place after attending government department trivia— but rarely is this venue described as anything resembling “sexy.” All that changed, however, on the evenings of Friday, April 14 and Sunday, April 16 as the auditorium seats filled with spectators eagerly awaiting the annual shadow cast production of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. As the movie plays behind them, the live cast lip-synchs and dances simultaneously, asking the audience to embrace the bizarre revelry of Transsexual, Transylvania. On these two nights, the ICC became a haven for a halfnaked rendition of the cult classic, rounded off by audience participation throughout the twohour-long performance.

“I think it really is about queer chaos, but it's also about joy and resistance,” Leah Miller (CAS ’23), the show’s producer, told the Voice. “There’s something so silly and so beautiful, but also really powerful, about watching someone shake around a pitchfork with three dildos on it in the ICC auditorium.”

Rocky Horror is a 1973 horror-comedy musical written by Richard O’Brien, and the screenplay for

to Georgetown with The Rocky Horror Picture Show

the 1975 film adaptation was co-written by O’Brien and director Jim Sharman. Rocky Horror become a cult icon, and the show’s prominent themes of sexual liberation and expression have made it a favorite among queer communities. It has become a staple among Georgetown’s queer students since shadow casts began in fall 2018, giving the largely queer cast an opportunity to build community while expressing their sexuality.

“It’s something that I feel extremely connected to because it’s queer without apology,” Olivia Yamamoto (CAS ’24), director of this year’s production, said. “It’s just silly. There’s representations of trans and queer people, but there’s also aliens.”

Viewing and performing such an unabashedly queer film is also an act of resistance itself, especially in light of Rocky Horror’s being banned in some states. “Rocky Horror does not exist in a vacuum, but it is about queer revolution, and that revolution only means so much as long as you’re extending it into your day-to-day practice,” Miller said. In celebrating open and unreserved expressions of sexuality and freedom, Rocky Horror defies newly enacted legislation seeking to censure or erase queer expressions and identities. The show’s audacious depiction of queerness counters this by making one thing clear: Queer people are here and completely visible.

Rocky Horror begins with a newly engaged couple, Brad (Barry Bostwick) and Janet (Susan Sarandon), looking for a phone after their car breaks down. They stumble into a remote castle in Transsexual, Transylvania, and the owner Dr. Frank-N-Furter (Tim Curry) introduces himself through the song “Sweet Transvestite.” “Frank” is surrounded by fellow Transylvanians who sport tiny top hats, white lapels, and large, ridiculous sunglasses—all shadowed by Rocky Horror’s live cast in only their underwear, dancing along. After being stripped down to their underwear themselves, Brad and Janet are led into a laboratory where Frank has made a costume change into a lab coat to unveil Rocky (Peter Hinwood), a muscular man with blond hair and blue eyes, wearing only a golden brawn thong. The plot continues nonsensically from there, and my best efforts to describe it will fail to communicate the magic of seeing it performed with a live shadow cast—but that’s because the show is not about the plot.

More than anything, Rocky Horror is about self-acceptance, a sentiment immediately exposed to the audience. Upon entry, anyone who has not seen a live shadow cast performance is marked with a red “V” on their forehead to signal they are Rocky Horror virgin, and the show starts with an extensive foreplay of “virgin sacrifices” to prepare the new audience. Everyone recites the show’s pledge in unison, with one hand on their asses à la the Pledge of Allegiance, a sign of respect to the show (and to their asses). All of the show’s virgins then scream their best fake orgasm, after which Miller hoped that no one would ever again fake an orgasm, saying, “You deserve better.” The Transylvanians then randomly select audience members to participate in a twerking contest.

stage in corsets and tights and garters and fishnets definitely is a challenging thing to do, and it’s not something people are confident to do.”

Facing total visibility, however, allows people to celebrate themselves within an appreciative community, often a departure from more repressive environments like high schools and hometowns, particularly when it comes to open queerness and body image. “The environment is so friendly and welcoming, and supportive enough to make people who maybe don’t feel as good about themselves to get better and feel more confident in front of a hundred or more people,” the cast member said.

Because Rocky Horror holds so much significance at Georgetown, those involved are committed to continuing the tradition. Though usually put on close to Halloween, the show was delayed until the spring due to the lack of volunteers for the strenuous—and unpaid—role of director.

“I stepped up into the position, not because I had the time and bandwidth to do it, but because no one stepped up to do it in the fall and I didn’t want this tradition to die,” Yamamoto said. “It would be just such a loss for the Georgetown community if we lost this, admittedly, very silly show and outrageously erotic spectacle.”

Tackling this provocative show, though daunting, made the long-awaited return of Rocky Horror as hilarious and fun as it has always been. To all the show’s virgins out there, next year is your moment to take things to the next level, be it as a member of the cast, crew, or audience—in the words of Dr. Frank-N-Furter, “Give yourself over

LEISURE

design by connor martin and sabrina shaffer

“Queer chaos” returns

A Case for the Classics: But I'm a CheerleadeR

BY ZACHARY WARREN

When you think of the greatest rom-coms of the late 20th century, what do you think of? 10 Things I Hate About You (1999)? Clueless (1995)? When Harry Met Sally (1989)? What if I told you a hidden gem exists in this sea? Better yet, what if I told you that gem is a tale of two teenage girls who fall in love at, you guessed it, conversion therapy?

But I’m a Cheerleader (BIAC), the 1999 queer romantic comedy directed by Jamie Babbit, is that hidden gem. Surprised? I can’t blame you. The idea of a late-1990s lesbian rom-com likely conjures up images of the exploitation and harmful stereotypes that plagued the little queer representation that existed at the time. However, instead of being condemned to the annals of past problematic films, BIAC has garnered a cult-like following among the queer community since its release.

BIAC stood out in the ’90s because it defied heteronormativity when doing so was controversial, but its impact extends beyond its label as a film that was “ahead of its time.”

To this day, BIAC shines as a paragon of queer media that does not simply avoid stereotypes but satirizes them, illustrating the superficiality of gendered expectations imposed on anyone, queer or otherwise. BIAC manages to land with audiences both as a great rom-com and as a striking criticism of gender norms that remains relevant today.

BIAC takes place at True Directions rehabilitation camp, where Megan (Natasha Lyonne) and her friends in rehab venture on a five-step program which, if completed, will “unequivocally” make them straight. Piloting this program is Mary (Cathy Moriarty), a strict

The world of True Directions is jarring and disconcerting, our eyes immediately assaulted by the garish environment Mary has cultivated to fit her idea of straightness. Pastel pinks and blues cover every surface of the rehab house, from the campers' clothes to the cleaning supplies they use. The program’s curriculum consists of activities that endorse traditional gender expectations. Mary teaches the girls how to clean the house and put on makeup, while Mike, the male counselor (played by an out-of-drag RuPaul), teaches the boys how to fix cars and chop wood.

From the gaudy color scheme to the absurd activities, BIAC evokes queer camp aesthetics with its kitschy cinematography and heightened acting. In addition to its visual appeal, this campy style also mocks the strict gender norms that the True Directions program tries to promote. By exaggerating and occasionally sexualizing the program, the film implies the futility of any attempt to make someone straight: As Mary guides the girls’ cleaning, she sensually pushes and pulls the vacuum cleaner, much to the campers’ enjoyment. As Mike works on the underbelly of the car, the boys ogle him while he gyrates his hips. By far the most evident example of this mockery is when the campers disclose the “root” of their homosexuality. Utterly ridiculous answers like “My mom got married in pants” and “I was born in France,” play into the artificial nature of these rigid conceptions of gender and sexuality. As Megan progresses through therapy, a fatal flaw in the True Directions program becomes apparent. Even though canoodling is strictly against the rules, Mary is naive to think that cohabitating a group of gay teens will not result in funny business. While the other campers quickly pair off, Megan attracts the attention of resident troublemaker Graham (Clea DuVall). Whereas Megan hopes the program will make her straight, Graham takes pride in her sexuality, spurning any attempts to change it. See where this is going? Like fire and ice, Graham and Megan butt heads over their different perspectives, yet in the end are drawn together by the sparking chemistry

Centering a genuine romantic relationship around two girls in a ’90s film is already impressive in and

of itself, but BIAC pushes the boundaries of the genre even further by adapting traditionally heterosexual rom-com tropes to fit queer experiences. From Megan’s struggle to accept her sexuality to Graham’s fear of familial abandonment, the obstacles Megan and Graham face are intimately relatable to queer viewers. Such accurate and meaningful representation is critical for the film industry. Queer relationships face different challenges from straight ones, and BIAC does well to acknowledge that.

Nowhere is this sentiment clearer than BIAC ’s ending. After discovering Megan’s hookup with Graham, Mary gives both girls an ultimatum: Participate in “simulated sexual lifestyle training” or leave the program. Megan refuses and is expelled from camp, but Graham, fearing disownment by her parents, accepts and stays. Abandoned by her family and now Graham, Megan makes one last attempt to win over her love. She crashes True Direction’s graduation ceremony with an improvised cheer routine and asks Graham to choose her over her family. Graham does, and the two go on to live their best lesbian lives.

This is where the film ends—there’s no cheesy epilogue scene where Megan and Graham find acceptance with their families and eat a big holiday dinner together. It’s admittedly a bittersweet ending, but it’s also an incredibly authentic one. Family abandonment is an ordeal that many queer people regularly face, and when it does happen, their partners often become their only source of comfort. With Megan and Graham’s ending, that everyone’s fairy-tale ending looks different.

BIAC is not necessarily the perfect romcom. The acting at times tests the line between camp and genuinely cringey, and certain supporting characters aren’t fleshed out enough to feel like anything more than props. The film’s biggest drawback is it doesn’t do enough to portray the vast diversity of queer people that existed in the ’90s and still exists today. However, considering how the film embraced uniquely queer issues without watering them down for straight audiences, it is clear that BIAC broke the heteronormative rom-com mold in 1999. For that alone, the film deserves its spot as one of the best rom-coms of its generation. G

13 APRIL 28, 2023 HALFTIME LEISURE

showcases Georgetown’s Asian American community and talent

BY KRISTY LI

History was made at Gaston Hall last week as Georgetown University’s first-ever Asian American musical took to the stage. For two and a half hours, the audience was transported to Potomac University, where they followed a group of Asian students through a semester of friendship, love, music, and late nights at Lou 2’s Twilight Tea. The musical explores multiple dimensions of the Asian American experience through five distinct story arcs that cross over into hilarious and touching moments.

(no) pressure: an asian american musical is a momentous step toward better diversity and inclusion for Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) artists in theater. The production opened with a short documentary showing the six-month creation process of the entirely student-written and student-led production. The magnitude of this undertaking cannot be overstated, as it typically takes years for a musical to materialize from script to stage.

“[Executive Producer] Aidan [Ng] pitched this idea of writing and producing an entirely original musical in a year, which at the time I thought was absolutely crazy. A part of me still thinks so,” Ed Shen (MSB ’23), producer and co-president of Georgetown’s Asian American Student Association (AASA) said. “But I think it was just the right kind of thing that I wanted us to have.”

Ng (SFS ’25) was motivated to increase Asian representation in Georgetown theater spaces that have historically been—and continue to be—predominantly white. Much of the cast had never acted before: “They’ve always felt the urge, felt the itch, but they just never had the place to do it,” Ng said. “Because if you're an outsider, it’s jarring, it’s scary.”

By featuring five leading characters, Ng explained, (no) pressure seeks to include as many perspectives of the Asian diaspora as possible. “We encourage the leads to take the lines that they have and make them their own, because obviously our scriptwriting team can’t encompass every single part of the Asian American identity,” Ng said.

Indeed, authenticity is the show’s greatest strength. Each of the leads—Ted (Wyatt Nako, CAS ’26), Arlene (Nirvana Khan, SFS ’24), Genji (Jesse Lin, SFS ’23), Cynthia (Samhita Vellala, CAS ’25), and Lexi (Alyx Lee, CAS ’25)—feel unique and personal. Although lacking the polish of a professional production, the show is genuine and energizing, and an absolute joy to watch.

If the roaring laughter in Gaston was any indication, (no) pressure’s comedic moments were expertly executed. One

highlight was the maniacal hilarity of Griffin Seo (Harry Tang, MSB ’25), the three-time Sexiest Man Alive, multiple-Grammy winner, and Potomac alumnus. His self-importance and open disdain for the students manifests through his dramatic bouts of rap and song accompanied by dancing goons.

Carl (Jean-Paul Nguyen, CAS ’24), a student DJ who performed a 5-hour set for the Potomac Day darties, also shined. Two scenes between Carl and Genji showcased the performers’ natural comedic chemistry. While Genji narrated the woes of his relationship with Arlene, Carl delivered humorous advice that was surprisingly sage, drawing laughter from the audience. (no) pressure skillfully draws from the shared experience of life on the Hilltop to take advantage of students' inside jokes.

However, it was not all laughs, and the show struggled to find its footing in the first act. The dialogue felt unnatural at times, which was most apparent in introspective scenes where monotonous line delivery made intimate moments feel intrusive. During a congenial first date at a highbrow restaurant, Arlene’s sudden question of “Why me?” comes across as more pushy than skeptical, and Genji’s drawn-out emotional response felt out of the blue. The stilted dialogue interfered with the audience’s understanding of relationships, causing many potentially touching moments to fall flat.

While the second act picks up the pace with multiple tensions coming to a head, it continues to suffer from character relationships that feel underdeveloped with choppy, cliched dialogue. Arlene and Genji’s split was an amalgamation of almost every single breakup trope— “It’s not you, it’s me,” “I need space,” “we’re looking for different things.”

Lexi’s tension with her homophobic roommate Vivienne (Audrey Sun, CAS ’25) was boiled down to a Disney Channel-esque confrontation, culminating in the protagonist “rising above it all.” Although predictable, the actors’ emphatic line delivery and the audience’s zealous reactions made the scenes feel like verbal WWE matches, and admittedly fun to watch.

What the dialogue lacks in nuance, the songs make up for in spades. The show's ballads offer intimate deep-dives into experiences that many Asian Americans can relate to. Cynthia and Lexi’s duet, “Belonging,” highlights Vellala and Lee’s incredible vocal abilities through powerful riffs and harmonies. Both characters struggle to find a sense of “belonging”: Lexi as a new student to Potomac, and Cynthia as a third-generation Asian American who has been disconnected from her culture. Through the song, they learn to build themselves up without external validation.

The most impactful moment of the act, and of the whole show, is undoubtedly when Ted’s parents call to tell him his dad left his job. While Ted’s earlier solo, “Famous,” is the manifestation of his dreams to make it in the music industry, “Is Anybody Out There?” is about the reality of financial struggles and a responsibility many Asian Americans feel to secure a stable future. The singing is layered, both literally and figuratively; Ted belts feelings from the front of the stage, while his parents sit behind him singing backup vocals. Ted acknowledges the financial burden of his parents sending him to college in this intergenerational exchange, and expresses his persistent desire to support them, demonstrating a core tension between personal ambition and familial responsibilities. Nako’s rousing yet grounded performance communicates the emotional complexity of intertwined gratitude and guilt.

Stories like Ted’s make (no) pressure such a promising development for the AAPI community in theater, and one that creates more opportunities for AAPI performers to showcase their lived experiences on stage. It created a space for dozens of Asian creatives at Georgetown to take the leap into producing, directing, and performing.

“What I hope comes out of this show is, first of all, that it's a good show and that people, you know, enjoy it,” Shen said.

“From a broader lens, I hope this shows the community that there is Asian talent for these kinds of productions, and that you can afford to dream big and be crazy.” G

1 LEISURE

1 THE GEORGETOWN VOICE 14 design by bahar hassantash

So you’ve decided to go to the movies. (You probably haven’t, not when your streaming service of choice is readily available on your laptop, but for the sake of this thought experiment, let’s say you have.) You’re an hour and a half into the newest Marvel film, a terrible teen flick you love to hate, or the most recent Oscars-bound feature, and there’s one question that drifts into your mind, pushing aside all attempts to follow the plot.

How much time is left in this movie?

For whatever reason—bathroom break, popcorn refill, stiff legs, sheer boredom—you want to get up from your seat. But leave for five minutes and the plot presses forward, leaving you in the uncomfortable position of whispering to your friends upon your return: “What did I miss?”

What happened to the movie intermission? Where did they go, those 10-15 minute breaks in films when the lights would rise and you could (finally) debrief the first half with your friends? Today, when you watch an old film with a built-in intermission, it feels like a relic from an era when actors spoke with mid-Atlantic accents and the credits rolled at the start of the movie.

The intermission’s original purpose was practical. Back when movies were projected from reels of film, the intermission gave projectionists time to switch between reels without forcing the audience to sit in a dark, silent theater. After the switch to digital film, intermissions stuck around as a staple of the movie theater experience—unless you grew up in 21st-century America.

Intermissions gradually faded from American cinemas throughout the second half of the 20th century, with 1982’s Gandhi being the last major film to feature an intermission—without the intermission, Gandhi would have kept viewers in their seats for over three hours. In the U.S., intermissions were dropped from films because cinemas wanted to fit in more movie screenings in a day.

Although intermissions are still present in plays or operas, the rationale in those contexts makes more sense from a practical point of view, providing the performers a chance to take a break and the crew time to do a hefty scene change.

What happened to the movie theater intermission—and could we please bring it back?

BY EILEEN MILLER

Quaint. Charming. Practical.

But now they’ve vanished, replaced by the everexpanding action-packed movie length, leaving moviegoers without the built-in bathroom break or concession stand run.

When it’s so easy to stream movies from the comfort of our couches, choosing to go watch a movie on a screen tens of times larger feels like it should be a special occasion. But when we arrive, it can feel tedious, rather than rewarding. Without intermissions, moviegoers are tethered to their seats for hours, faced with a vexing dilemma: toughing it out until the end of the movie, or slipping out of the theater and missing a few (possibly crucial) minutes of the film.

But the intermission has not vanished completely. If you’ve ever been to a cinema abroad, it’s possible you’ve seen this seemingly obsolete tradition alive and well. Egypt, Iceland, Jamaica, Switzerland, and Turkey all have intermissions in their movies. In India, Bollywood filmmakers even incorporate the intermission into their film’s structure; the breaks don’t disrupt the flow of the film because they’re woven into the story. Evidently, the world has not completely moved away from the intermission. Why can’t we bring it back here? Moviegoers in intermission-friendly countries get to enjoy a break in their movies—but could bringing back the intermission have other benefits as well?

With 15-second TikToks, Instagram reels, and the infinite scroll of a dozen other social media apps, our attention spans are getting calibrated to short, quick bursts of content. As social media trims our attention spans, movies are getting paradoxically longer. Movies routinely clock in at over two hours; Business Insider found that today’s highestgrossing films are 120 percent longer than they were 30 years ago. Avatar: The Way of the Water (2022) clocked in at three hours, 12 minutes—30 minutes longer than its predecessor. We’re being presented with two extremes: a rapid, never-ending succession of

short videos that study your every click to keep you tethered to the app as long as possible, or a two-plus hour film. Where’s the chance to enjoy the moment?

Enter: The intermission, a chance to take a break and enjoy the film by reflecting on what you’ve just seen and wondering what will come next.

Just as streaming some services switched to releasing TV episodes one at a time to bring back the suspense of waiting a week for the next episode, slotting in an intermission could add suspense to the movie-watching experience. Splitting the movie-watching experience gives more time for the plot to sink in and allows viewers to better appreciate the film. During an intermission, viewers can revel in what happened during the first half and speculate about what will come next, making the experience more interactive.