9 minute read

POLITICS

from Issue #1302

Biden’s Realism, and High Hopes in Georgia and Ukraine

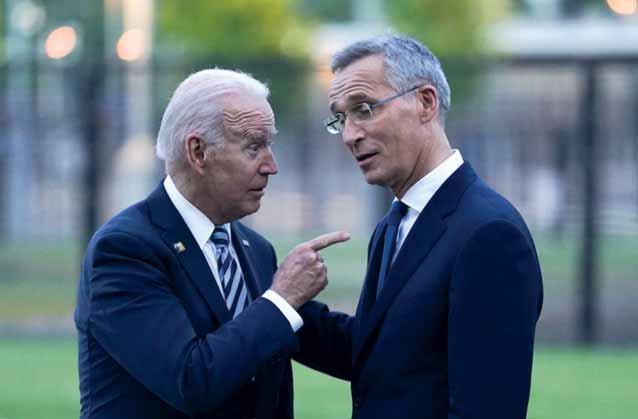

President Biden and NATO Sec-Gen Stoltenberg. The dominant perception is that Georgia is gradually being pushed out of grand strategic developments in Eastern Europe. Image source: Jam News ANALYSIS BY EMIL AVDALIANI

Advertisement

US president Joe Biden’s policy towards Eastern Europe is gradually shaping up.

First, Biden aims to restore the US credibility in the region shattered during Trump’s presidency. Doing so will be an arduous task requiring consistency not only through public statements, but also concrete political, economic and military actions. The recently held summit of the Bucharest Nine, a group of countries on the eastern edge of NATO, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovakia, joined by the president himself, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg, indicated that the Eastern European NATO states would receive far greater attention from Washington. But there are, however, uncertainties regarding Georgia and Ukraine and their bids to join NATO and the EU.

Biden is a realist. He understands that a radical increase in military support for Georgia and Ukraine would upend the regional balance of power and invite countermeasures from Russia. The timing for this is especially unfavorable, as America cannot afford to spend too much time and resources on the European front in light of growing geopolitical and geo-economic challenges posed by China in the Indo-Pacifi c region. And this is where political consistency of small but harmonious support for Eastern European states matter.

Biden is well familiar with the troubles of Poland, Ukraine and Georgia. Support for the eastern fl ank, from the Baltic to the Black Sea, is not only about defending the pure democratic and liberal ideals of those fl edgling democracies, but more so about the geopolitics of Europe and the Eurasian continent as a whole.

Further east, in Georgia, the situation is gloomier. The dominant perception is that the country is gradually being pushed out of grand strategic developments in Eastern Europe. The territorial problems Georgia has due to the Russian military presence in Abkhazia and Tskhinvali Region (the latter also known as South Ossetia) will remain a major obstacle for the country’s NATO membership. Moreover, Russian military moves in the South Caucasus, particularly in the wake of the Second Karabakh War, could serve as a major disincentive for the US and NATO overall to make a major expansion step in the region.

Biden will be more straightforward in his vision of future bilateral ties with Russia, and his administration will certainly be more principled towards Moscow. It is also clear that Biden is unlikely to seek further complications with Russia. The latter’s military presence in Georgia’s Abkhazia and Tskhinvali regions will often be invoked and criticized by the US offi cial, but it is highly unlikely that Washington is ready to push for Georgia’s NATO membership.

The Biden-Putin summit in Geneva signaled the US’ unwillingness to complicate ties with Russia amid the grand strategic shift in the US attention from the Middle East and parts of Europe to the Indo-Pacifi c region. As is the case with the Eastern Europe fl ank, this does not mean that the US foreswears its attention or obligations toward the region. But it does, however, indicate that Washington will be increasingly occupied with other problems, and raising tensions with Moscow over Ukraine and Georgia’s NATO membership might not be the foreign policy line to pursue at this time.

This also does not mean that bargaining over the fate of Georgia will be taking place. The issue of NATO membership will just be put on hold, again. But under Biden, the search for models for Georgia’s alliance membership will be proposed. The non-inclusion of Georgia’s troubled territories under NATO defense obligations, thereby extending the collective defense article solely over those territories under Tbilisi’s control, could be one of propositions. Enhanced NATO-Georgia partnership involving more regular military training, transfer of military technologies, etc. could be suggested. Under Biden, Georgia will continue to as a crucial partner in the region allowing America to infl uence the corridor leading to the Caspian Sea, and allowing Washington to penetrate deep into the middle of Eurasia. But when analyzing the American perception of the Ukraine and Georgia dilemma, one should understand that in the coming intensifi cation of rivalry with the Chinese, Washington would need a Russia which is more amenable. An amenable Russia means the latter seeing benefi ts in cooperating with America. This could take various shapes, but one of them would most likely be bringing down tensions along Russia’s southern and western borders by postponing the expansion of NATO.

The Need to Invest in the “Gray Zone”

BY MICHAEL GODWIN

Agrowing topic entering defense and military circles is a new concept on modern warfare, much of the doctrine surrounding which is still being formed. While technically not a total militarization and engagement in hot confl ict, it is becoming a far more palatable form of statecraft, particularly by larger nations. This new sphere of global security strategy is being labeled curiously as “Grey Zone Confl ict”, or simply GZC.

Since the end of the Second World War, the earth has been free of major-power wars. This length of global peace is something virtually never seen in history, despite several “smaller” confl icts since then. With the exception of these smaller operations in Africa, the Middle East, and the South Pacifi c, the concept of Total War has all but fallen from the picture. Taking its place has become a range of small confl icts, counterterrorism operations, and peacekeeping missions, all of which fall within the scope of GZC. GZC has nestled itself between the previous binary view of war and peace with the advancement of globalization and rapid development of technology.

While the defi nition is still fl uid, GZC take their position in the center, encompassing a wide range of violent and nonviolent forms of confl ict. They use military and non-military actors, and can even include private sector actors such as private security companies and defense technology fi rms. However, due to the nature of GZC, the use of military forces is highly restrictive.

As seen with the American and other coalition forces in Iraq, soldiers saw their typical role being shifted. From individual soldiers to the leaders on the ground, they were forced to move from being a warfi ghter to policing with a focus on humanitarian aid, connection with key community leaders, and training local military and police units. Compounded by the use of information operations and private military contractors, Iraq became an example of the more kinetic form of GZC.

Russian activities in Georgia and Ukraine are another example of both high and low tempo GZC. On one end, the aftermath of the invasion of the Donbas region is an example of the high tempo of GZC. Almost every day there are small raids, employment of snipers, and artillery duels, but not to a level of war. Reports come out periodically about Ukrianian service members being killed in action.

Russian continual occupation of Georgian territory is a much more low tempo part of GZC by comparison. Russia maintains a continual military presence masked as “peacekeeping,” information operations aimed at converting the populace, and the occasional raid into Tbilisi controlled territory. While not as volatile as Donbas, it still remains on the GZC spectrum of operations.

Entering into the realm of GZC does not inherently mean the entity is operating with nefarious means or intentions. It is a healthy alternative to open war indeed, but can also open the way for further de-escalation and future peace. This is ultimately up to the powers at hand, and these are usually large entities such as the United States, Russia, NATO, and China. However, it’s not uncommon for smaller players to get involved. For a smaller nation to engage in GZC, such as Georgia, it gains the ability to further mask their activity in the shadow of those larger entities.

For Georgia to enter this fi eld, it is fi rst important to develop their GZC force components. Through internal training, new departments and units being raised, and partnering with the large friendly entities already engaged, Georgia can become an effective force in the new way of conducting asymmetric confl ict operations. However, this means changing the fundamental way that confl ict is viewed, how the elements involved are deployed, and how the politicians at home manage public expectations.

This last part is interesting, as much of the general population is stuck with a Cold War view of warfare: a massive number of infantry, armor, and artillery clashing in open warfare to some climactic end and a clear victor being declared ceremoniously. For better or worse, this is simply not a reality anymore. The fundamental change to GZC should be also shared and portrayed with the public, and expectations managed.

The foundation to Georgia’s effectiveness in this is inter-agency communication and operability. While the Ministry of Defense (MoD) will play a part in GZC, they will not be the tip of the spear. Further, they must understand that it is imperative, as other organizations such as the State Security Service of Georgia (SSSG), Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA), and potentially private security companies and defense consultancy fi rms will be leading GZC operations.

However, this is not to say that the MoD will be uninvolved. While special intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets will be key to success, so will the Army’s special operations forces (SOF). Even select parts of the conventional army will be called upon to fulfi ll roles they didn’t previously have. SOF and their assistant forces will focus on training and supporting their partner forces in the GZC operations. Not dissimilar to what Georgian and their American SOF partners did in Afghanistan, training and ultimately fi ghting with the Afghan SOF.

The American Army has gone so far as to introduce an entirely new unit, unique in its role. The Security Force Assistance Brigade, or SFAB, was built to be a component of the GZC. They work with, train, advise, and eventually fi ght alongside foreign forces, usually in small confl icts and other sectors of GZC. Georgia, while they may not have the fi nancial and personnel luxuries of the United States DoD, could benefi t from implementing similar training to a sector of its light infantry or other reasonably capable and applicable military units.

This training would be designed around increasing both independence and interoperability with other Georgian and foreign forces. Language skills, cultural training, and purpose-built close relationships with foreign assets, even South Ossetian and Abkhazian forces sympathetic to Tbilisi would reap dividends for Georgia’s GZC campaign. Ultimately, this tactic can start to eat away at the glue Russia has placed over those regions and pull the proverbial wool away from the eyes of the populace to see that they are being used and abused by the Kremlin.

GZC is a sector of pseudo-warfare that is here to stay. With large powers such as NATO, the United States, the United Kingdom, and more becoming heavily invested, it is regional powers like Georgia that need to become a part of the composite GZC force. The key is combining both private and public ISR assets and Georgia’s SOF and capable units, and tie it together with the political commitment of Tbilisi to GZC’s modus operandi. This cocktail of interagency excellence puts Georgia back in control of not just the eastern Black Sea, the South Caucasus, but also the future of its national defense and international security and military image.

*Emil Avdaliani is a professor at European University and the Director of Middle East Studies at Georgian think-tank, Geocase.

Photo by Saba Shavgulidze/Imgur