7 minute read

Nairobi & Finesse

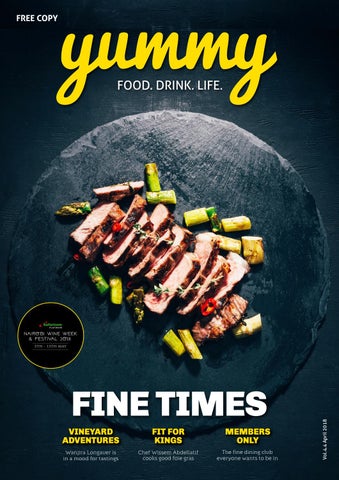

As across the world the concept of fine dining gets turned on its head, how is Nairobi faring in comparison, wonders Katy Fentress as she samples some of the best meals our city’s chefs have to offer.

I pull up a stool at the tall kitchen bar style counter, to either side, shiny black butcher shop-style tiles are plastered on the walls. A waiter shaves heads of foam from pints of craft beer and across the countertop, the Chef frowns in concentration as he adds the final touches to my Wagyu steak tartare. The small kitchen brigade darts back and forth, readying themselves before the evening throng, the savoury smell of grilling meat hangs in the air.

Advertisement

To some, the restaurant Sierra Burger and Wine and its charming founder and Chef, Alan Murungi, might seem like an unlikely flag bearer for the new phase of Kenya’s fine dining revolution. Fine dining should be about stiff formalities, small fussy plating, expensive chandeliers and endless amounts of cutlery. Sitting up close and personal to the inner workings of the beast as I am now, courtesy of Chef Alan’s weekly Kitchen Table, should not qualify as fine dining. At least not in the traditional sense of the term.

REVOLUTIONARY ORIGINS

We have the French Revolution to thank for the advent of fine dining. Before beheading aristocrats was a thing in France, the only commercial places for people to get a bite was in taverns and family-run establishments that served a basic fare offering little in the way of choice. Meanwhile, the upper classes in their gilded palaces, indulged in multi-course meat bonanzas, feasting on elaborate dishes prepared by highly trained chefs.

As the bloody revolution drew to a close, many of the chefs that had been in the service of the now headless or escaped aristocrats, found themselves without a job. Before long, these displaced culinary maestros began to open their own eating establishments, introducing the concept of dining to the solvent middle classes.

This new approach to eating out brought with it all the trappings of its high origins: delicate china, complicated silverware, white starched linen tablecloths and a long list of etiquette prescriptions.

For the longest time then, French dining was defined by complicated dishes cooked for hours on end which glorified butter, fat and decadent bechamel-style sauces. All this, however, was turned on its head in the 1960s with the invention of nouvelle cuisine, a style of cooking that focussed on simple minimalist dishes creatively plated with the aim of extracting the essential flavours of ingredients.

Restaurant at the Norfolk Fairmont Hotel and Sierra Burger and Wine

Much of the rest of the world soon caught on. In the space of a few decades nouvelle cuisine, with its rejection of hearty, home cooking, was wholly embraced by the global elites. So it was that for the better part of two centuries French cuisine, old and new, symbolised all that was fine and sophisticated about food.

Experiential Eating

We walk through the old colonial “Exchange Bar”, the short-lived Nairobi stock exchange, past the statues of the Buddha in Thai Chi restaurant and on, into the bowels of the Sarova Stanley hotel main kitchen. After pausing to observe Chef Godfrey Ouda as he delicately lays out strips of honey-infused bacon on a platter, we are ushered up some industrial stairs, into a tiny room with a table set for a luxurious feast and a big glass window through which to admire the kitchen proceedings down below.

When it comes to Chef’s Tables Paolo Marro, the General Manager at the Sarova Stanley, does not pull any punches. Earlier in the week my colleagues and I were surprised by a car full of butlers who drove to our office in order to ceremoniously hand deliver four embossed invitation cards. The Sarova management even offered to arrange to pick us up on the day - an offer that, much to the dismay of my colleagues, I politely declined.

Marro, who has managed hotels in all corners of the world, explains that at the Sarova Stanley no Chef’s Table ever resembles another. He lovingly details the process the team goes through to conceive and execute the menu and for the umpteenth time, apologises for insisting on needing a whole week in order to organise the kitchen staff around the preparation of the meal.

The menu is bespoke, the service impeccable, the wine well paired and the care with which Chef Godfrey presents each new course, obviously the fruit of an intense labour of love. Marro confesses that he is so keen to nail the evening’s menu, he will go as far as googling his more famous guests in order to get a feel for what kind of food they might get a thrill from. With his insistence on curating every single aspect of the diner’s experience, Marro has tapped into one of the essential aspects of modern fine dining. When people expect to part with large sums of money for a meal, they want to leave the place feeling their cash bought them something exquisitely personalised, in this case a “behind the scenes” first hand experience of the chef working their art to the nth degree.

FINE DINING IS DEAD

Fine Dining is dead and we have the likes of David Chang to blame for it. Or so stated the food writer Alan Richman after dining at the New York Momofuku restaurant in 2016. David Chang, a Korean American restaurateur and culinary innovator, was the first person to turn sitting at a bar on a hard stool an elevated experience worthy of a hefty price tag.

When we consider that Noma, in Copenhagen, one of the best restaurants in the world, encourages guests to “come as you feel comfortable” and offers the option of eating at a communal table, we begin to realise how much things have changed over the course of the last couple decades. Jay Rayner, an influential British restaurant critic, joined the “anti-fine dining” choir when in 2015 he penned an article for the Guardian newspaper in which he argued that people were turning against fine dining in favour of casual dining establishments which deliver the good stuff with a minimum of fuss.

Chang, who trained as a French chef but then went on to found the famous Momofuku restaurant empire, has led the charge against the fine dining approach. His disruption of the high end cooking scene has had such a noticeable impact, that he recently wrote an article grieving the demise of the traditional fine dining French restaurant. The cheek.

In the last episode of his recent documentary series “Ugly Delicious”, Chang sums up his views on fine dining today by saying: “Traditionally fine dining was white tablecloths, linens, flowers, people with penguin suits and for many years that was where the best food lived. It’s something I think I’ve historically tried to push the buttons of, stripping away the nonsense and just getting to the food”.

Italian superstar Chef Massimo Bottura echoes Chang, when he underlines that the important element of a dining experience is reflected by the ingredients themselves. Fine dining, he says, is a process by which chefs search for culinary perfection and emotion. The focus, then, is on the food itself rather than the rarified experience of eating in an elegant establishment inspired by antiquated French aesthetics.

LONG LIVE DINING ON FINE FOOD

Formality is out the window in favour of experiential eating, an obsession with emotion and the provenance of ingredients. This last aspect is what Chef Aris Athanasiou, who runs the kitchen at Tatu Restaurant at Fairmont The Norfolk hotel, has set his sights on.

We are seated at the last of our three Chef’s Tables and Chef Aris is half way through presenting a thorough history of the Angus steaks we will soon sink our teeth into. The vegetables too are worthy of mention, he tells us with pride, as they are grown on an organic farm in the Mara especially for use in the Tatu kitchen. As he talks, I inhale the aromas of a glass of ouzo he paired with our scallop and jamon Serrano dish and reach the conclusion that here in Nairobi, where fine dining is often the preserve of its iconic hotels, the dining experience becomes a fusion of the chef’s personality with that of the hotel.

Obituaries aside though, we live in a city where any traditional interpretation of the word fine dining is steeped in a history of colonialism. Which might go a long way towards explaining why the city’s more classic style fine dining restaurants rarely operate at maximum capacity while gourmet burger joints and high-end Asian eateries seem to enjoy a more robust crowd.

When it comes to sizing up to the fine dining global trends, Nairobi might still be a bit behind but we are witnessing glimmers of innovation that are worthy of mention. The Sarova Chef’s Table, by far the most elaborate of the ones we tried, had a dish which included a tender lamb’s tongue served on a bed of pureed truffled peas with a creamy ugali side. Alan Murungi rears at least three different breeds of cows in his Nanyuki ranch and proudly brews his own brand of Sierra craft beer and Aris Athanasiou injects echoes of his native Greek cuisine into his culinary offerings at Tatu.

Nairobians might shy away from the pomp and circumstance but they are fully on board with the experiential, curated and intimate experience that something like a chef’s table can create.

So basically, if you want a fine dining experience in Nairobi you can go two ways: either search out a restaurant that throws tradition to the wind and focuses exclusively on bringing you excellent food made with the best ingredients in a curated but not overly formal setting, or go all out and book yourself an intimate evening in one of the restaurants where our city’s best chefs make it their business to open up their kitchens so they can demonstrate their culinary prowess to discerning foodies with some cash to spend.

Katy Fentress and Josiah Kahiu were guests at the Chef’s Tables of the Sarova Stanley Hotel, Tatu

Restaurant at the Norfolk Fairmont Hotel and Sierra Burger and Wine