ROYAL HOSPITAL FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE, DEPARTMENT OF CLINICAL NEUROSCIENCES AND CHILD & ADOLESCENT MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES, EDINBURGH

Publication Authors: Gill and Chris Fremantle with Tom Littlewood

Published By:

NHS Lothian Core Team:

Ginkgo Projects Ltd on behalf of NHS Lothian

Janice MacKenzie, Project Clinical Director, NHS Lothian

Sorrel Cosens, Capital Planning Project Manager, NHS Lothian

Mary Murchie, Charge Nurse, DCN Outpatient Department

Margaret McEwan, Play Services Co-ordinator, Play Specialists and Play Assistants Manager

CONTENTS

3 FOREWORD 11 THE WAY THROUGH 63 I AM NOT A NUMBER 119 WONDER 183 TIME & SPACE 233 A FUNDER’S PERSPECTIVEEDINBURGH CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL CHARITY 241 A FUNDER - PROGRAMMER’S PERSPECTIVE - EDINBURGH & LOTHIANS HEALTH FOUNDATION 1

3

New hospital buildings are once in a lifetime opportunities. We build them to enable better services, incorporate new technologies and new thinking about what it means to care for patients and their families and carers.

NHS Lothian’s Royal Hospital for Children and Young People (RHCYP), the Department of Clinical Neurosciences (DCN), and Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) all have significant histories and, in moving to a new shared building, the ambition has been to create a new chapter.

The integration of art and therapeutic design supporting patients in their pathway through healthcare is an important aspect of NHS Lothian’s expectation for many prospective building projects. This ambition is shared with two key funders of the Beyond Walls programme, Edinburgh and NHS Lothian Charity and Edinburgh Children’s Hospital Charity (ECHC).

Beyond Walls curator and producer Tom Littlewood of Ginkgo Projects Ltd formed a programme that focussed on supporting the patient journey through enhancing wayfinding, designing for dignity, personalisation and distraction.

The programme also provided time and space for artists to work through a fellowship and residency programme.

The sections in this publication explore the ways that the art and therapeutic design has been developed from the perspective of NHS clinical, nursing and allied health professional staff together with the perspective of the artists and designers. We hope that the combination of voices provides a rounded understanding of this ambitious and innovative project.

In addition, there are two essays articulating the perspectives of the key stakeholders, Susan Grant on behalf of Edinburgh and Lothians Health Foundation, and Roslyn Neely for Edinburgh Children’s Hospital Charity. These highlight why art and therapeutic design are considered important elements of healthcare.

More than 40 individuals and teams – graphic, textile, furniture and lighting designers, artists, sculptors, illustrators, printmakers, writers, composers, film makers, animators, theatre directors and digital programmers – have contributed to 26 projects to create Beyond Walls for the new NHS Lothian Hospital forming one of the largest art in healthcare programmes in the UK.

5

The New Building

The major new building at Little France is shared by two distinct acute services, the Department of Clinical Neuroscience (DCN) and the Royal Hospital for Children and Young People (RHCYP). In addition, it also includes a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) with its own unique needs. All three services have strong identities and proud stories. Maintaining the sense of individuality whilst ensuring efficient use of shared services is central to the design of the building.

The new building supports modern up to date healthcare across all three services, and brings physical and mental healthcare together within the building.

There are common themes relevant to the building for all patients:

• patients are at the centre of the new hospital and all the processes within it

• the building design suppor ts families as they care for their children/young people and adults in the healing process

• physical and mental health facilities are on the same site

• each service within the building has its own identity within an integrated clinical facility, providing appropriate and discrete environments for all patients: children; young people; and adult patients, each with their own clear visual and spatial identity

• patient pathways for both patient groups are separate wherever possible

• 60% of the 233 beds are ensuite single rooms providing both privacy and supporting infection control

• the building is spacious, light, colourful and comforting and does not feel like an institution

The Art and Therapeutic Design programme, Beyond Walls, was founded on support for promoting the experience of patients as they navigate the physical and emotional experience of arrival, waiting, treatment and staying in hospital. Susan Grant commented, “It’s a fantastic showcase in terms of the physical outcomes, but also in reflecting what’s possible with very generous funding support and a commitment from genuinely engaged staff members.”

6

Key Stakeholders

NHS Lothian Charity has an ongoing commitment to the use of art and therapeutic design through its Tonic Arts programme, to achieve its overarching aim, ‘longer lives, better lived.’ Edinburgh Children’s Hospital Charity (ECHC) - aims to put the child first: Roslyn Neely comments, “We exist to transform the experiences of children in hospital so they can be a child first and a patient second.”

NHS Lothian, in committing to the role of art and therapeutic design to support the patient pathway, recognised the importance of integration within the building from the outset. Janice MacKenzie, NHS Lothian Project Team Clinical Director, and Sorrel Cosens NHS Project Team Project Manager provided the core vision and support to enable the formation and delivery of Beyond Walls.

Janice MacKenzie said of NHS Lothian’s ambitions, “We were clear we didn’t want the building to just be like any other hospital and we were very clear that we didn’t want the art to just be for the Children’s Hospital. Everyone on the team could see the benefit of the art work in all its different guises in the existing hospital and we wanted it not to be the same but better.”

Our Approach

Ginkgo Projects worked for both NHS Lothian and for the main building contractor, Multiplex Construction Europe Ltd to curate and develop the Beyond Walls programme. Each project went through a staged approval process overseen by a multi-disciplinary Steering Group. The programme was directly procured through Ginkgo which allowed for space within the commissioning process for artists and designers to work flexibly with fabricators. Early selection of designer and artist teams allowed for an integrated approach to embed proposals with the design of the building.

Key to the curatorial approach beyond the positioning of commissioning within keys points of the patient pathway was the opportunity to draw in the city and build new partnerships to promote and reflect the social and cultural aspects of the city which the hospital serves. Focus was placed on a people led approach embedding co-creative and participatory practice building relationships between artists and designers with staff and communities. It also served to promote the value of a placebased approach to leverage local and regional cultural resources and partnerships for the benefit of all participants.

7

Scale and Focus

Art and therapeutic design enriches more than 30% of the rooms in the building.

The programme draws on the substantial evidence of the role of therapeutic design and art to:

• reduce patient stress through enhancing wayfinding

• de-institutionalise spaces to support patient dignity

• improve recovery times

• reduce the requirement for pain-relief medication

• increase staff retention rates

Beyond Walls supports and promotes a sense of identity and distinctiveness within the hospital environment. Each project was developed within the guiding principles:

• creating a positive healing environment focusing on user experience

• recognising the importance of cultural context and cultivating community links

• integrating the role of the artist and designer into the design and working life of the hospital

• upholding artistic quality and contemporary practice.

Publication Structure

We have spoken to many staff and have, wherever possible, brought together the voices of NHS clinical and support staff with the voices of artists and designers to provide the clearest sense of how the programme is focused on patients, families and carers through the following four chapters.

The Way Through addresses wayfinding, a key challenge in healthcare environments, and a specific cause of stress and anxiety for patients, families and carers. Providing effective wayfinding is, as with all healthcare, a multi-disciplinary challenge involving the NHS, architects, wayfinding signage designers, and artists. Art provides several important aspects of wayfinding including building on the building colour scheme adding pattern and texture at key points, commissioning unique landmarks, and connecting the building with its wider context.

Wonder draws out the multifaceted use of distraction. Distraction has traditionally been associated with children’s services, and in this project the benefits to service delivery of distraction have been extended to specific aspects of adult services. Distraction is widely understood to be a vital aspect 8

of the patient pathway, particularly in the context of treatment and also in relation to staying and waiting in hospital.

I am not a Number explores how artists and designers have helped shape dignity and personalisation, the complement to distraction, and a vital aspect of a caring environment. This case study focuses on the design process for challenging spaces including the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service, the Child Protection Unit, the Spiritual Care and Bereavement Suites as well as Interview Rooms across the Hospital. The engagement process, driven by co-creative approaches from the various artists and designers, has shaped not only the look and feel, but more fundamentally the ways in which these different areas meet the needs of patients, families and carers.

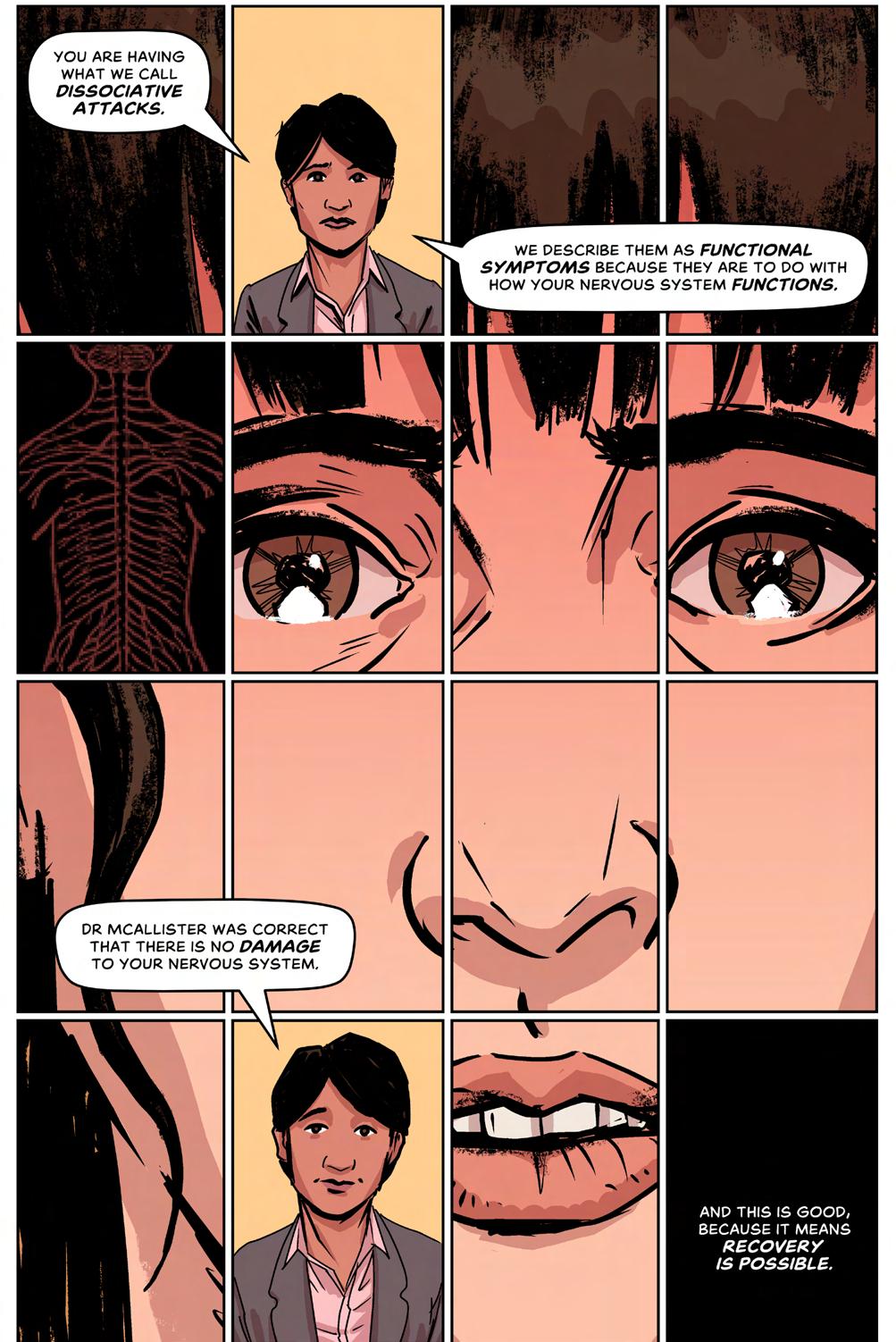

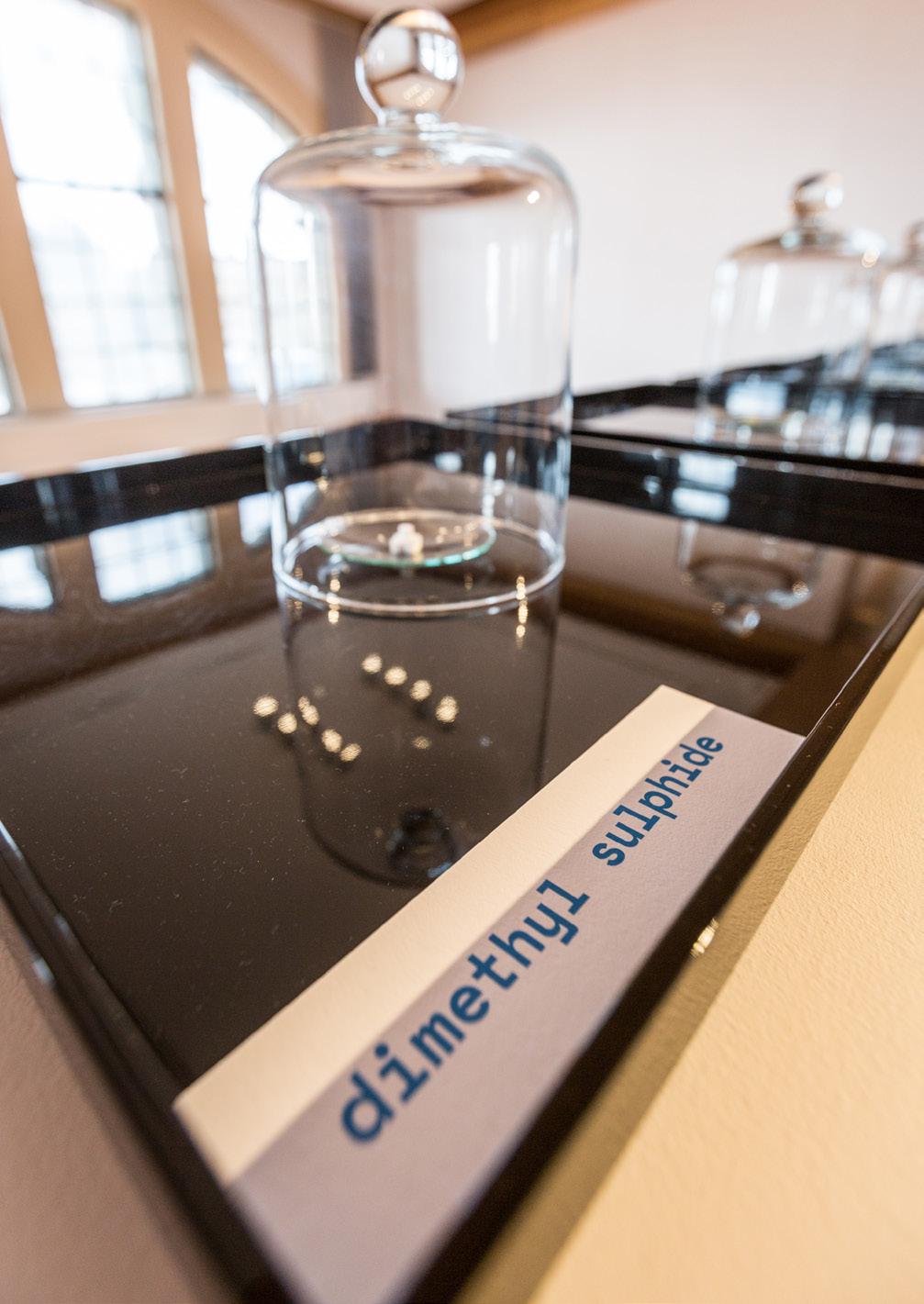

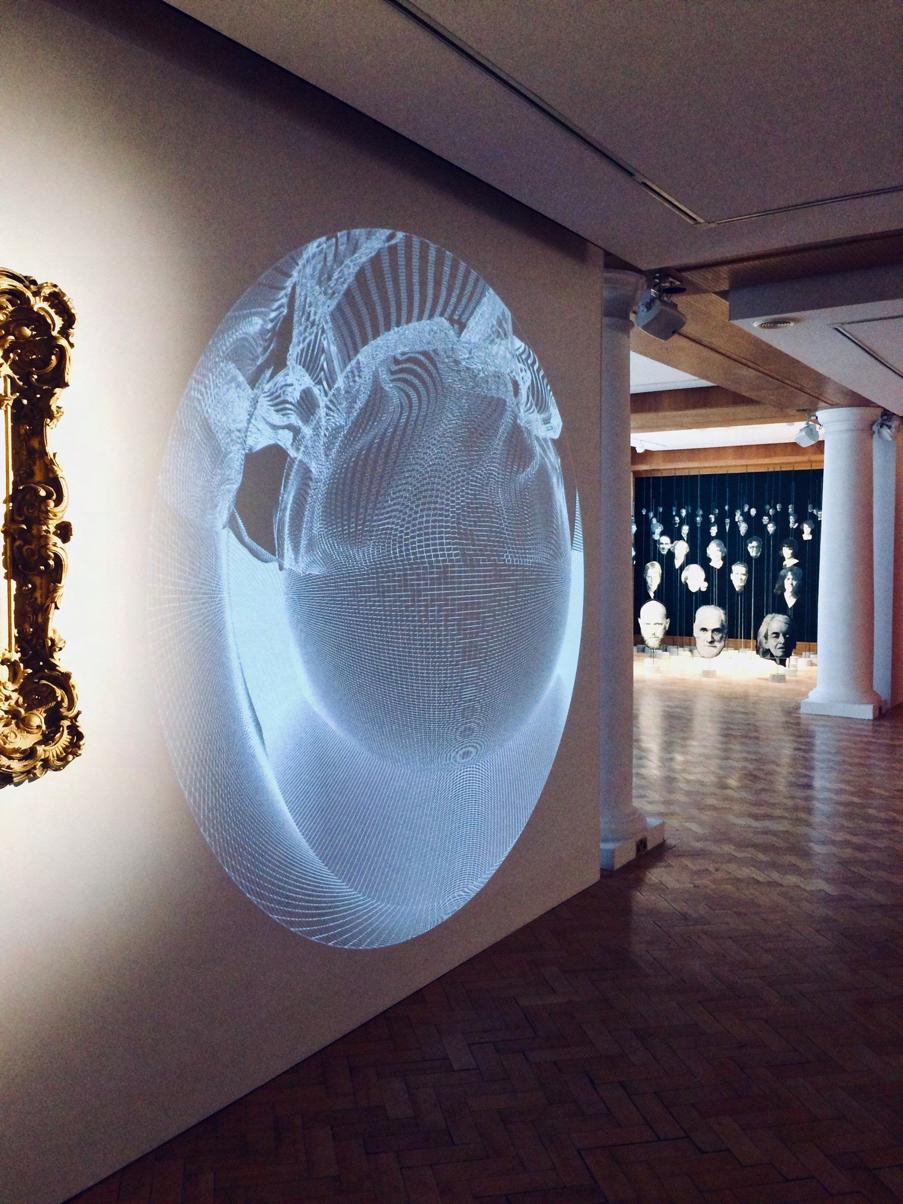

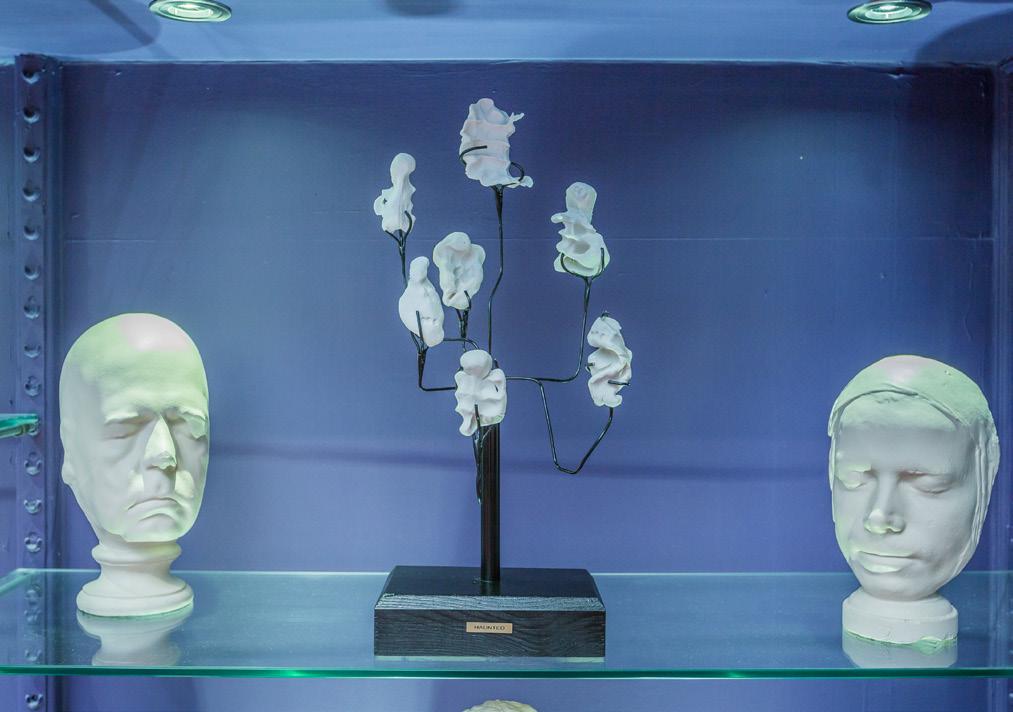

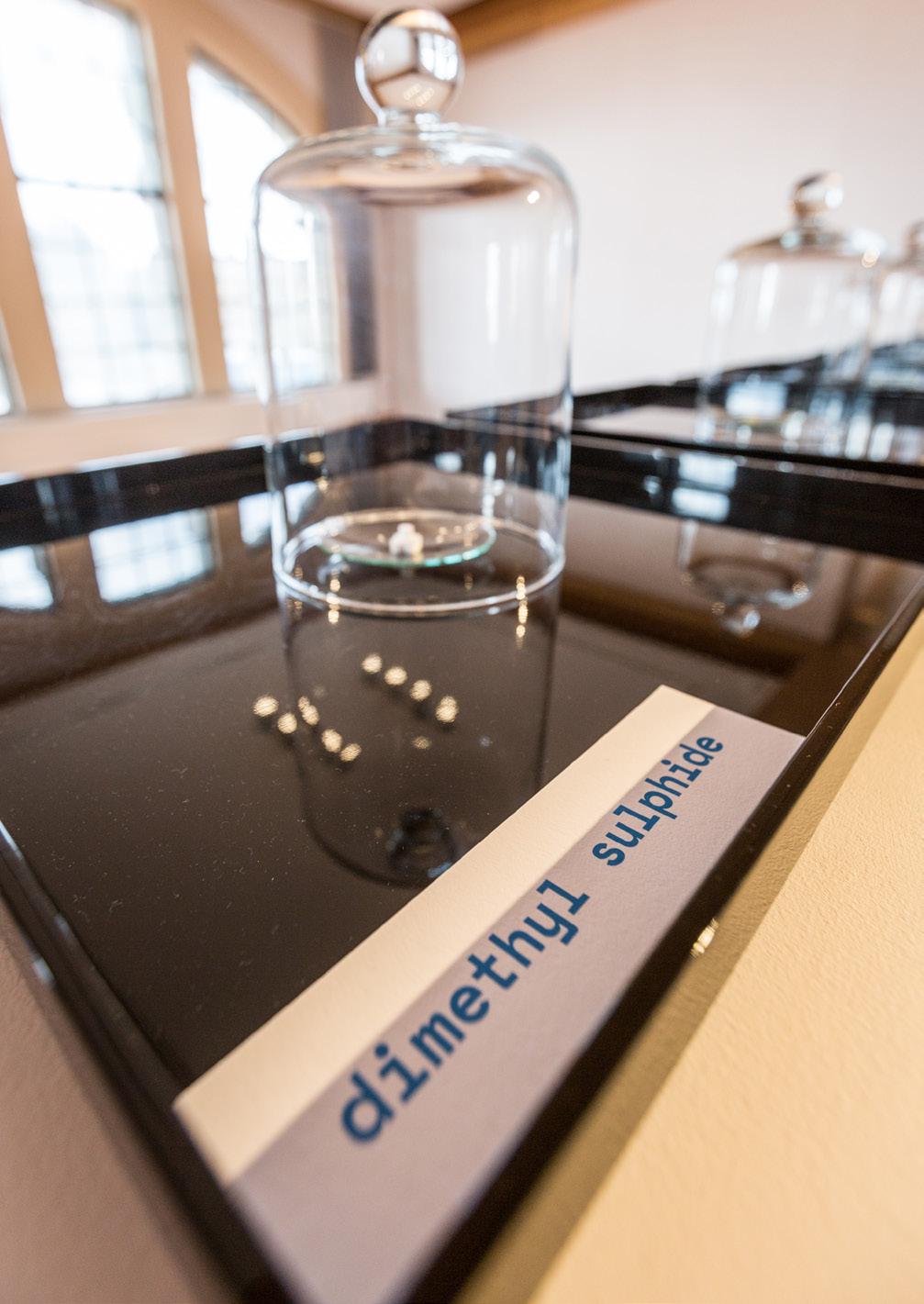

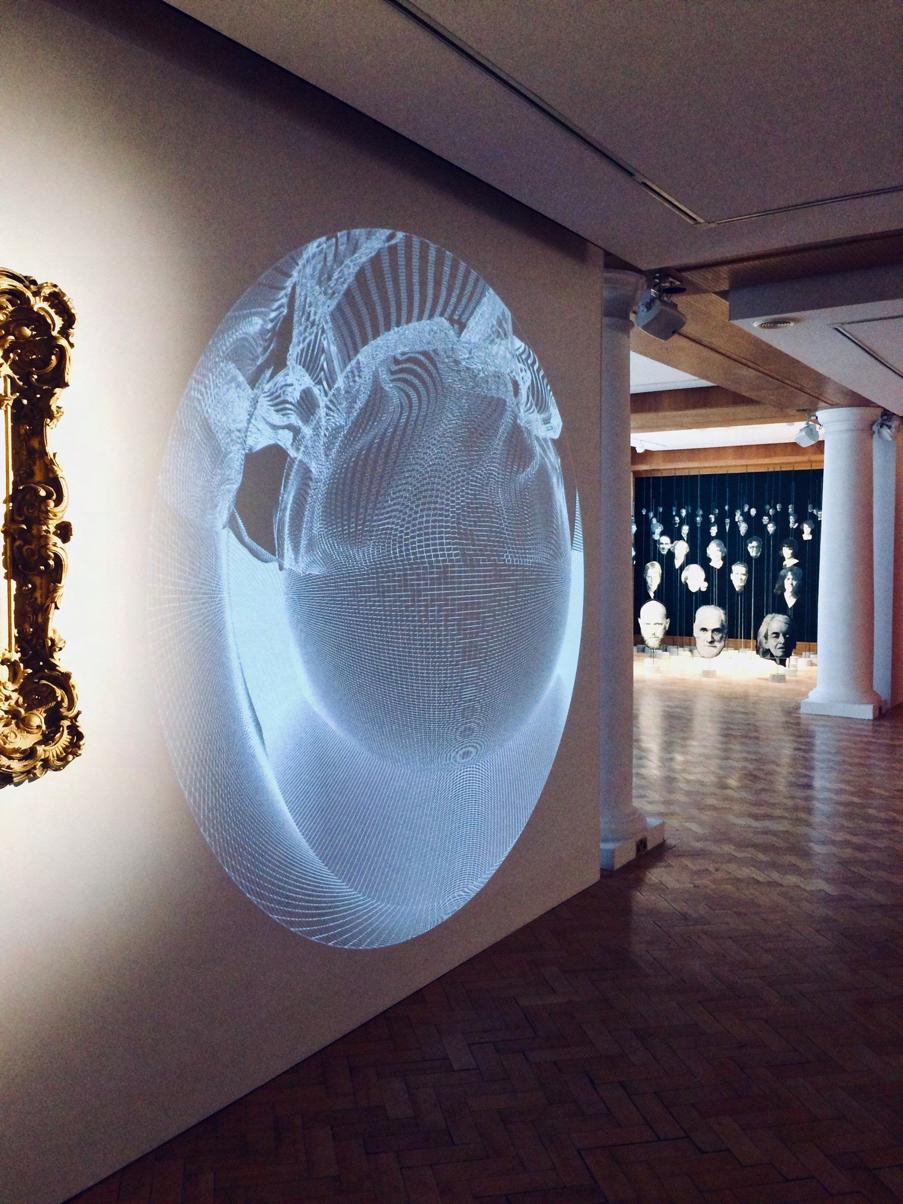

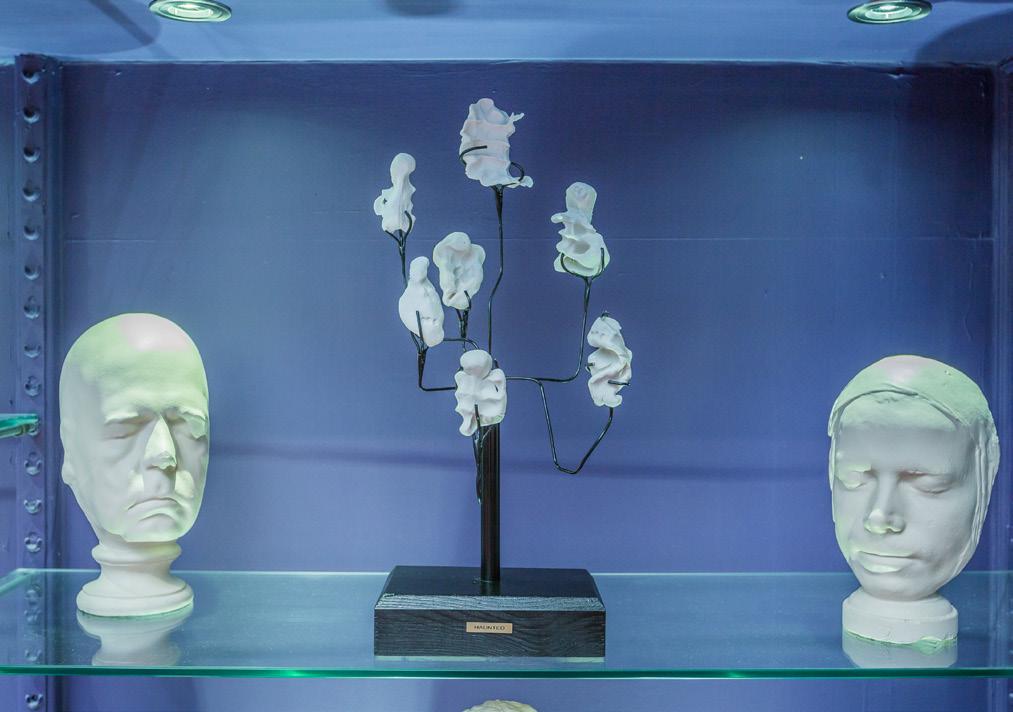

Time & Space opens up the work undertaken by artists and designers through the Residencies and Fellowships programme. Artists worked with Mental Health Service users, but also with clinicians in the Department of Clinical Neurosciences interested in smell and trying to build awareness of Functional Neurological Disorders.

Artists and designers involved in this aspect of Beyond Walls were not asked to deliver any installed work in the new building, but rather to open up and connect with new communities and audiences. Throughout the Case Studies we have highlighted the impact and benefit of the cocreative approaches of artists and designers, clarifying the needs of patients, families and carers and resulting in funders allocating additional funds. Rather than profiling each project in detail, we have focussed on showcasing the key benefits to patients and staff of working with artists in the creation of a therapeutic environment within the provisioning of a complex building with complex service needs.

We very much hope that our placebased and people-led approach is reflected in the resulting high quality final work. We hope that the approach provides evidence to support the case for the normalisation of working to create therapeutic environments over the coming years.

9

11

Key Collaborators

Spine Wall and Main Entrances: Peter Marigold, Artist

Christina Liddell, Dance Instructor

Evan Glass, Patient

Peter Keston, DCN Consultant

Atrium Vestibules: ELFA / Kevan Shaw Lighting Design

Wall Graphics:

Claire Hope, Artist

Alison Unsworth, Lead Artist

Rachel Duckhouse, Artist

David Galletly, Artist

Natasha Russell, Artist

Andy Illingwor th, Interior Designer, HLM Architects

Sanctuary Stained Glass: Emma Butler-Cole Aiken, Artist

Old to New:

Kate Ive, Artist

Joachim King, Designer and Maker

Ruth Honeybone, Manager, NHS Lothian’s Archive

12

Why wayfinding works.

13

‘Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?’

‘That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,’ said the Cat.

14

Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll

We have all felt lost at some time, whether that’s physically or mentally. It might be that we were stressed, distracted, excited or something as simple as not being able to spot a sign. Finding your way around a hospital as a patient, carer or family member can seem a bit scary, bewildering, exciting or just over-whelming.

The patient’s pathway is the key inspiration of Beyond Walls. Everything is focussed on making the experience of visiting or staying in the new Children’s Hospital, CAMHS and DCN as positive as possible.

In this chapter on Wayfinding we review several projects that seek to lessen patient stress by supporting patients and visitors to find their way through the building. Sometimes quirky, always interesting, the art and therapeutic design exists to make the various

journeys that countless numbers of people will undertake as smooth and as easy as possible.

The Spine Wall is a 180 metre long glass reinforced concrete wall that acts as a backbone to the building, flowing directly into the main atrium from both external approaches.

As Peter Marigold explains, “The design for The Spine Wall features three-dimensional skin textures taken from one representative from each of the three Services.”

Peter always knew he wanted explore how to create such a huge artwork without it feeling overwhelming. “I wanted to investigate textures and shapes of skin at microscopic levels and how these seem both utterly familiar and yet equally mysterious.

I chose skin samples of patients and staff because I also wanted to reverse the idea that the hospital is simply a container of humans, but instead the building is created by the people who inhabit it. In this case, the skin of the occupants wraps around the building between all parts of the hospital flowing into the landscape outside.”

Peter ran casting and impression making workshops to explore the evolving themes. As he says “There were lots of different people involved in lots of different ways. They weren’t about working on the artwork directly but they did provide a taster of what I was thinking about, so we worked with microscopes and textures, modelling and casting. They were fun and everyone was really enthusiastic. In the end three volunteers’ skin samples were used.”

15

Sorrel Cosens said, “One of the things that came through loud and clear from staff moving out of the existing sites was that there is a real love for the buildings and their history, so they were very keen to develop something physical that could be a new identity. This is really why and how The Spine Wall came about.”

It also helped the staff understand the benefits of the Beyond Walls programme. As Tom Littlewood, explains, “Clinical Directors were working alongside DCN staff and patients. The artist-led workshops started to open people’s minds about the role artists could play in what is a major intervention in the building.”

With such a large-scale work there were many technical challenges. Peter Marigold said, “We went through a lot of samples of differing depths in order to get

it right. The wall looks different depending on the various lighting effects and we also had to have a balance between an approach that would work outside as well as inside.

What I wanted was that sense of scale. It’s huge but when you’re standing right next to it you might well think it’s just texture. You might not be sure if it’s stone or mineral. I’m hoping that your relationship with it will be different, depending on where you are standing and what part of the wall you’re seeing.

I wanted it to be characterful without being obvious. It’s the idea of skin but without identity. It could be any one of us. The patterns of skin are staggered and scattered across the space. Only coming together to form complete images in certain key areas. I’ll leave you to discover where they are. Hopefully a double-take

played out over a long period of time.”

Kevan and artist Claire Hope were responsible for the Atrium vestibules which the Spine Wall links. The two glass entrances, one at each end of the Atrium, form both a physical connection and colour ‘place’ marker. Kevan and Claire felt that embedding the entrance and exit experience in people’s memories could “help to reduce two potential moments of stress in an individual’s day by simplifying a journey.”

One of the aims NHS Lothian felt was that each part of the building should have its own identity and that the patient pathways for both patient groups would be separate wherever possible.

You can see the distinct colour of the vestibules from across the Atrium and from most levels

16

internally: a simple visual cue on a patient or visitor’s journey. The new Children’s Hospital entrance is bright blue and orange and the DCN entrance is green and purple. Claire Hope used abstract, transparent colour washes which are both a wayfinding tool but are also relaxing and very striking. She described the space as being about the, “play of daylight on the transparent paintings” with a “natural sense of time and location as the colours, shades and shadows shift across the hours. By overlaying artificial light in the evenings, the dynamic changes to that of a beacon in the landscape - a full body experience” that offers “a moment of calm.”

The attention to detail to ensure a clear pathway is at the heart of this building and carried on through the use of light and colour at the DCN entrance through to the Service.

The green of the vestibule is picked up and carried on as a visual clue with the same green continuing in wall-mounted lightboxes, providing a guiding stream of colour and leading you to DCN Outpatients reception.

Another way the DCN entrance is differentiated is the large artwork stretching up three floors. Peter Marigold, working with clinicians from the Department developed this from a patient’s angiogram. The staff were very engaged in what the visuals in the Atrium and in particular ‘their’ entrance would be like. Sorrel Cosens said, “The staff are rightly proud of what they do and seeing that exhibited in a different way, though art, has been a really new experience for them.”

At the RHCYP entrance Peter created a large-scale, wall-based work that captures the movement derived from a therapeutic dance

session held at Musselburgh Primary Care Centre. The looping shapes track each of the participant’s movements -one is the young patient Evan Glass, the other dance instructor Christina Liddell. These movements were at first interpreted by the artist using motion tracking technology and then loosely translated by hand. Photographs superimposed onto the abstract forms differentiate the colours of the two dancers in motion. Peter wanted the artwork to reflect the happy and playful interaction between the patient and dancer through an abstracted form.

Colour is an integral part of the Wayfinding techniques used throughout the hospital as part of interior design, signage as well as art and design. It enhances identity, creates a memorable pathway, and a more relaxing and

17

pleasant environment for patients and their visitors, and, of course, the staff.

As interior designer Andy Illingworth explained, “I was obviously very keen to understand what the Art and Therapeutic Design involved and how this would integrate with our overall concept for the hospital and also what sort of areas it would affect. It was important to make sure it coordinated with existing services and existing architectural interior elements of the building.”

Andy continued, “It helped that Ginkgo were involved very early in the bid stage of the project and they understood what we were trying to do and vice versa from the outset. In some cases, the projects could stand alone but in others they had to consider the whole hospital. For example, the Wayfinding Graphics had to tie in

with the colour scheme for the different hospital areas. Their areas of expertise and the artists who had been appointed could take a theme that we’d identified and dedicate a lot of time and extra research into taking it to that next level of enhancement. For us it might be a concept idea but looking at it from an artist’s point of view means a different approach.”

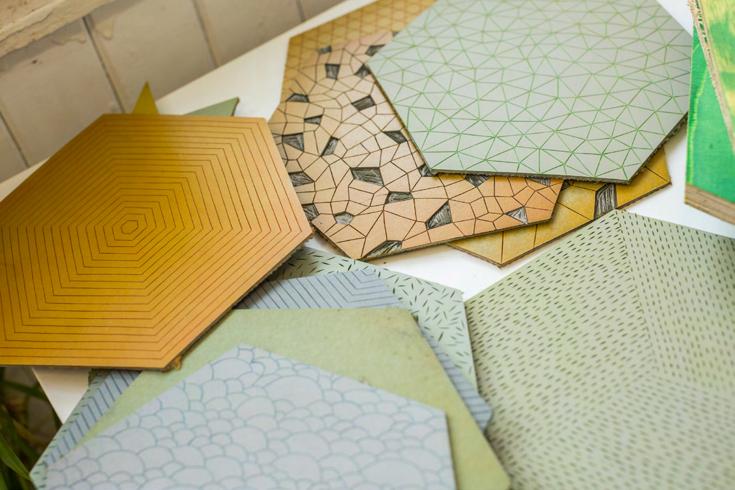

That ‘different approach’ was created by a team of three artists Rachel Duckhouse; David Galletly and Natasha Russell, supported by Lead Artist Alison Unsworth. As Andy Illingworth pointed out earlier, as a major project providing visual clues to support the patient pathway, it had to also connect with the existing colour palette and themes which HLM had introduced.

The Wayfinding Graphics team had a lot of freedom to come up with new, interesting and quirky interventions at approximately two hundred locations and which, as Alison Unsworth says, “supports the patient journey throughout the hospital, provides patient and visitor distraction, helps create a sense of place and identity and creates links with the surrounding city community.”

Creating the links with the community meant getting out and hearing what people thought. “We did a lot of engagement work before we started. We had a workshop at the National Museum of Scotland where we asked people to describe and draw on luggage labels what they thought should be included in the graphics.”

David and Natasha spent significant time at the old Hospital

18

working with play staff, children and young adults. “It was important to be on the ward and play areas and doing drawing activities to get feedback about the interests and context. We also did the same in the waiting areas in DCN with each artist working on various activities so that we could chat to people about what interested them, for example, memories and reminiscences of the local area.”

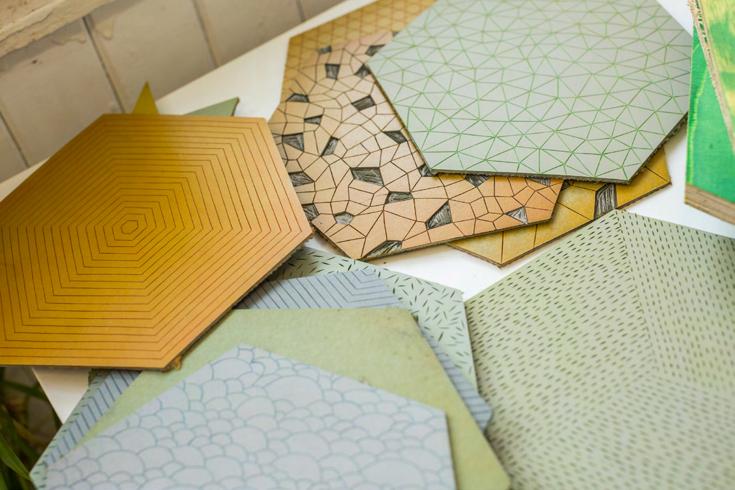

“The Wall Graphics you will see around the hospital for Wayfinding are split into three groups,” explains Lead Artist Alison Unsworth. “The first group is in the main public corridors created by Rachel Duckhouse. As a person moves through the public corridors on each floor there will be ten to fifteen Graphics locations with the idea that they are a series of linked images and you will remember the last one you saw as you spot the

next one at a junction ahead creating a visual ‘trail of breadcrumbs.’ They draw on HLM’s colour scheme with accent colours to give a visual ‘pop’. They are in linear strips and are made of different shapes. There are cubes on the ground floor, chevrons on the first and second floors and hexagons on the third and fourth floors.” These patterns and colours are subtly replicated around signs as an extra visual Wayfinding clue.

Rachel takes one shape as a motif and plays with it in different patterns. Rachel is a printmaker and she hand-prints so a lot of the shapes are linocuts or are printed directly from materials. For example, on the first (rural) floor they are printed directly from wood capturing the grain. She made a whole range of printed patterns, scanned them to make digital files and created lots of different combinations of shapes.

It was very important for Rachel that you could see these were hand-made and not digitally altered for size or shape so there will be little random marks or misalignments to add ‘life’ and interest. Where a line is made up of multiple shapes, for example hexagons, she’ll also has a floating hexagon that looks like it’s jumped up to the ceiling or fallen down to the floor. The odd chevron will look like it’s decided to be a boomerang, and cubes will pile up like unfinished walls. All these quirky details add both interest and help with working out and remembering where you are.

The second group is the next step on the patient journey and is when you enter each ward, the corridors within them and the nursing stations and reception desks. These are by David Galletly and Natasha Russell. David’s work relates well to the colour scheme

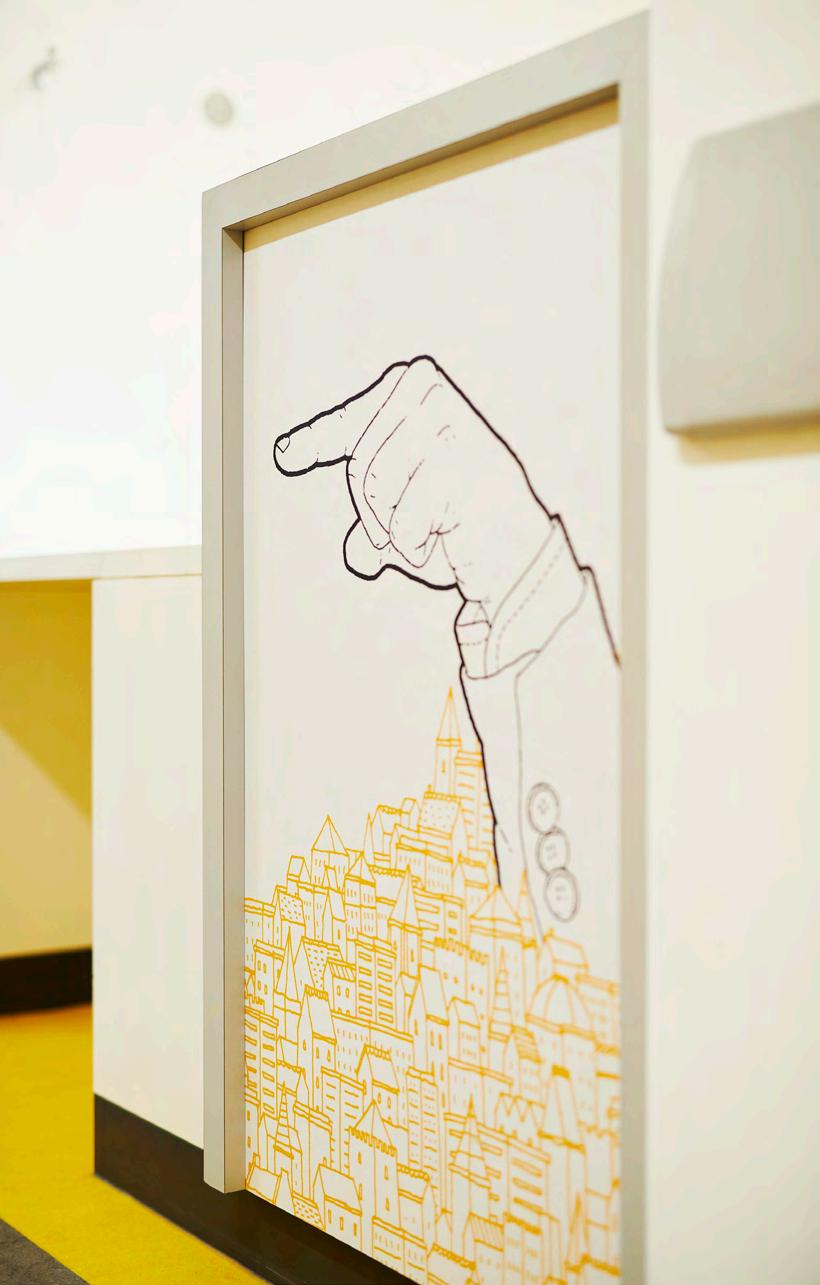

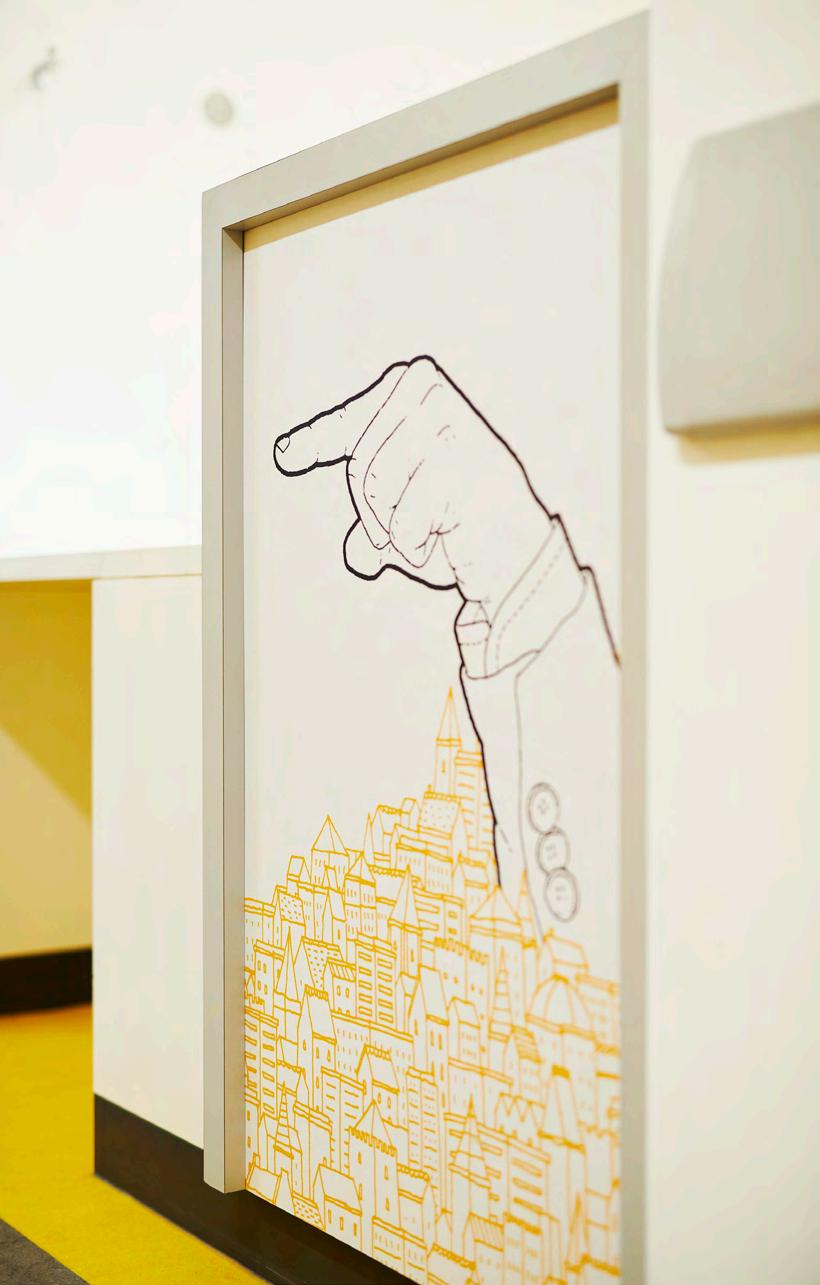

19

for each floor as his work is black line drawings with a ‘spot’ colour which are hand drawn, scanned into the computer and then manipulated further. Like all the other artists, however, it’s important that there are slight imperfections and quirks. David used HLM’s conceptual idea, so on the ground (urban) floor, he drew the Edinburgh cityscapes with playful elements, like giants or ice-cream sundaes. With Wayfinding it can be something as simple as giving a ‘hand’ to find the right way! However, he kept his own quirky style, so on the first (rural) floor there are trees with lots of leaves, but with parts of buildings popping up from underneath them, reminding you that the Ground Floor is below you. The stairwells between floors depict mixed themes as a visual reminder of which floors you are between.

Natasha Russell works through printmaking, painting and drawing through illustration. Like David she used HLM’s conceptual scheme so, for example, on the second (lochs) floor there are islands in the Firth of Forth and people swimming. On the fourth (mountain) floor there are wonderful mounds that could be, “Huge Hills, Hairy Heads or Hopping Hummocks?”

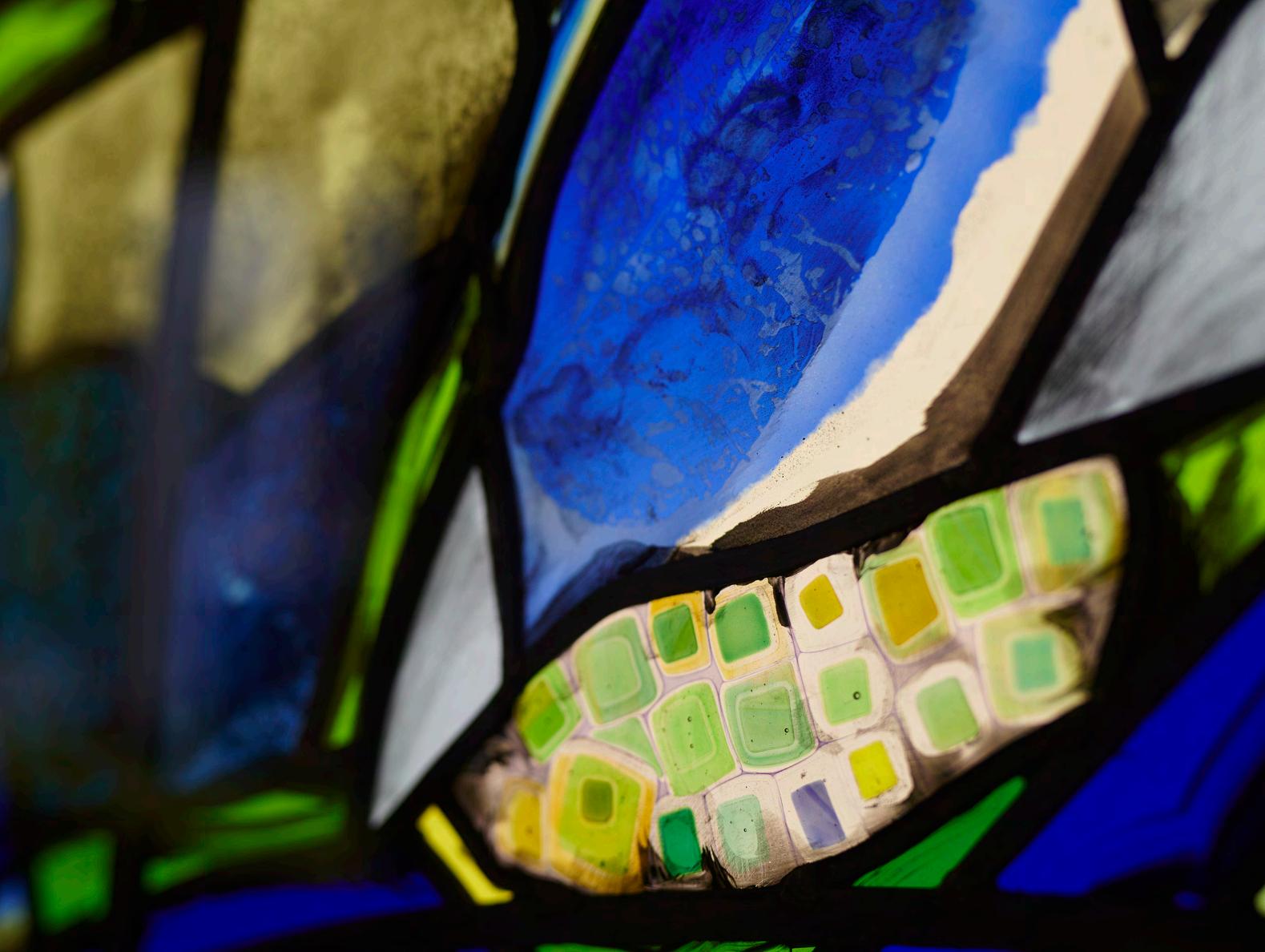

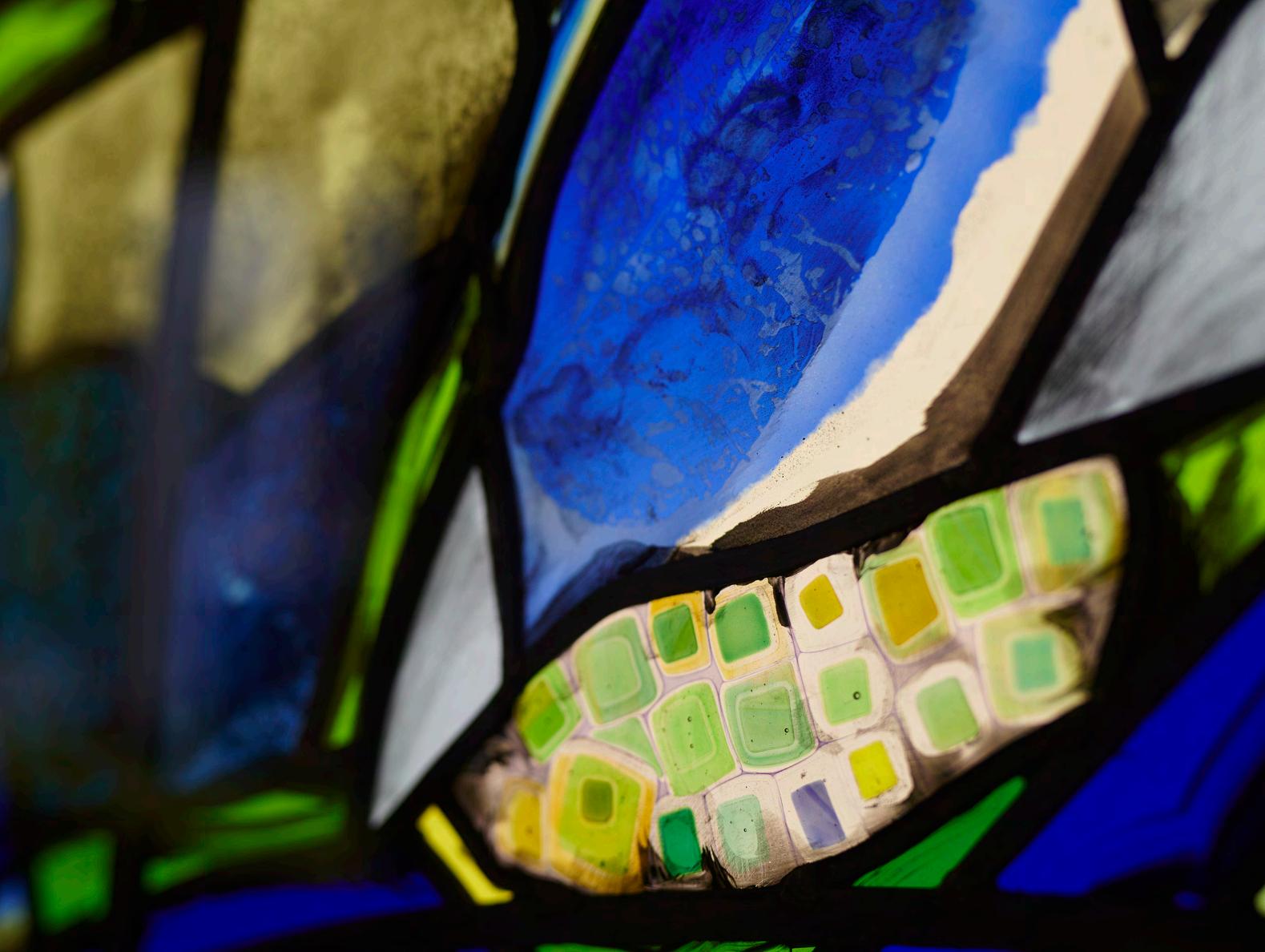

Some journeys in hospital are ones where it is vitally important that they are as stress-free and dignified as possible. Emma Butler-Cole Aiken was commissioned to lead the design of the stained-glass which appears outside the new Bereavement Suite. She had previously designed and made the Sanctuary stained glass window for the old Hospital in 1997, a place she knew well as she had spent a lot of time there in the nineties. “My daughter was

being treated for kidney failure following an e-coli infection and it was a worrying time for our family. When creating the original window, I tried to remember how I felt at that time, and what I would have liked to look at. That’s when I came up with the idea of a beautiful tree tunnel with light at the end as a symbol of hope.”

In the new commission Emma again used nature as her inspiration with the design being based on one of the trees on the right-hand side of the old window. The theme is the cycle of life: green shoots and healthy leaves; weathered branches bearing the weight and finally the inevitability of decay. The old stained-glass window has been much loved over the years and so she has created a new window using traditional techniques and colours to bring a memory of the old alongside the beauty of the new.

20

The importance of remembering and honouring the old whilst celebrating the new is at the forefront of Old to New by Kate Ive, a series of portals placed at key points within corridor spaces.

The project aims to share the identity, history, and stories of the three institutions as they undergo a transition from their original sites to the new building at Little France.

Kate said, “I really enjoyed doing the project, it was fascinating. I loved tapping into these unique nuggets of history and information and representing it in the works. During my research I met with a range of people in the Children’s Hospital and heard the hopes for the new buildings. In DCN I was meeting neurosurgeons and saw some of the technology they use. Both groups were excited by the opportunity to have their input

heard and reflected back in the artwork.

It was clear through all the stories I got from the staff how important their everyday workspaces and the history in the buildings was to them. For example, I engraved one of the outside perspex discs from the Norman Dott designed domeshaped operating theatres and it’s gone into an artwork because the neuroscientists are very attached to those spaces.

I was commissioned to make artworks to go into wall mounted lightbox cabinets throughout the hospital. Eight are in the new Children’s Hospital; two in CAMHS and eight in DCN, plus one double sided wall-mounted cabinet in a waiting room in the Neuroscience Outpatients Waiting Area which is a technological feat by the cabinet maker Joachim King. It’s viewable from the waiting room and the

walkway. The artwork is more three-dimensional because we had more space. It relates to Neuroscience Imaging and is a polarized artwork. The artwork is completely clear but it uses filtered light to change colour. You can spin a knob on the glass and that changes the filtering of the light and hence the colours seen in the artwork. The shape of the artwork symbolises the brain and there are little arrows hand cut into the glass. I also was lucky enough to get to spend time in the NHS Lothian Archives. I was given a lot of help by the team there and I used it to get a sense of the different Departments I was working with.”

Ruth Honeybone, who manages NHS Lothian’s Archive based at the University of Edinburgh, was one of a team who helped Kate and others. “The Archive holds significant collections that relate

21

to the hospitals moving to Little France. This primary source material was used by artists and researchers who wanted to draw on the history of the buildings and the past experiences of both patients and staff. Our role was to introduce the potential of the Archive and help narrow down what material might be of most interest. That’s what we do for most researchers, but what was intriguing in this context was watching the artists take this initial shared starting point in their own direction. Seeing how the stories stored within the Archive were absorbed into the work of these artists was fascinating – they have created a connection with the past through new pieces that will be enjoyed now and in the future.”

Kate found the Archive fascinating. “I asked for a lot of books! I looked at the history. One of the pieces

in the new Children’s Hospital was informed by my finding that, when rickets was still prevalent, the old Hospital had a Sunlight Department where they used to treat the children. The piece is lots of pairs of sunglasses. The lenses are engraved with facts about the Sunlight Department. Plus, the medical advice that, with care, it’s good for us to get out in the sunshine and fresh air. There are also mountain scenes and sailboats to represent a healthy, active outdoor life. Another big thing that came out of working in the Archive was that there were lots of sources of inspiration to make the wall mounted cabinets circular rather than a traditional shape.

It’s been such a fun and interesting project and I have loved making pieces that relate to the history and stories from the various departments but that also

celebrate their future. For example, I created a piece about the history and future of bone setting. It’s called ‘Sticks and Stones’. and is outside the Plaster Suite. It’s filled with representations of the types of treatments through history, like wooden splints, through bandaging, then pinning, to the future where 3-D printing might be used.

Each of the artworks is unique in approach and treatment. I worked with the staff and thought about the location and tried to pick themes and materials that were relevant. A number of people have said they thought they were all made by different artists! I wanted each one to be dependent on where it was going and who it was going there for.

I know staff will see them all the time and patients and visitors may well be spending long periods of time at the hospital. I wanted to

22

create pieces that won’t disappear into the background and so I’ve tried to put a lot of fine and hidden details into the background. That way people will be able to see things that they didn’t see before.”

Conclusion

NHS Guidance says,

“The wayfinding process is fundamentally problem-solving and is affected by many factors.... People’s perception of the environment, the wayfinding information available, their ability to orientate themselves spatially and the cognitive and decisionmaking processes they go through all affect how successfully they find their way.”

The basic principles of wayfinding according to Jan Carpman’s ‘Design that Cares’ are:

• Knowing where you are

• Knowing your destination

• Knowing how to get there

• Knowing when you have arrived

• Getting back out

The reprovisioning has provided NHS Lothian with a significant opportunity to modernise service delivery, and wayfinding is critical to the efficiencies being sought. To deliver this required HLM’s design for the building to focus on the patient pathways through treatment and care involving multiple different hospital departments. Beyond Walls contributes to this multi-layered approach to wayfinding through a number of complementary elements. Fundamental to Ginkgo’s approach has been both the focus on the Patient Pathway and draw the cultural assets of the city and region into the new building –a place-based approach.

The Spine Wall both marks the Atrium out as a distinctive space and leads visitors into the building,

almost as an outstretched hand connecting the point you come onto the campus through to the reception desks and onwards. The texture is organic and brings a human element into the clinical environment.

The Atrium vestibules are designed to be accessible. Bright colours allow them to both be easy to see and memorable. These two projects are the first examples of landmarking which runs through the building.

The Wayfinding Graphics integrate into the overall architectural design as well as the signage. Rachel Duckhouse’s ‘trail of breadcrumbs’ accentuates the designation of different levels of the hospital as different layers of the landscape with associated colour palettes.

23

This particular element represents an innovative use of the art programme to animate and strengthen the memorability of the colour and signage. The use of graphics in Waiting Areas to reinforce patient and visitor under-standing of where they are in the building, drawing attention to the important locations.

Finally, the Old to New project provides ‘Landmarks’ at key points throughout the building across all three services. Landmarks are specifically identified in NHS Scotland guidance as an important part of supporting the patient pathway.

In an environment where corridors and entrances, as well as signage, are all standardised, things that only appear once, placed at significant locations are useful.

They signal ‘when you’ve got there’ as well as giving staff a specific reference point – ‘keep going until you see a porthole full of sunglasses’. Involving staff and connecting to memorable aspects of the various histories means that these are unique points of interest. They meet practical wayfinding needs as well as the high-level objective of fostering pride in the history of healthcare in NHS Lothian.

Problem-solving approaches are important but there is another level – sense-making. Ginkgo’s ‘place-based’ approach directly strengthens the practical wayfinding and also contributes to making sense of the building by drawing on the resources of the City and region.

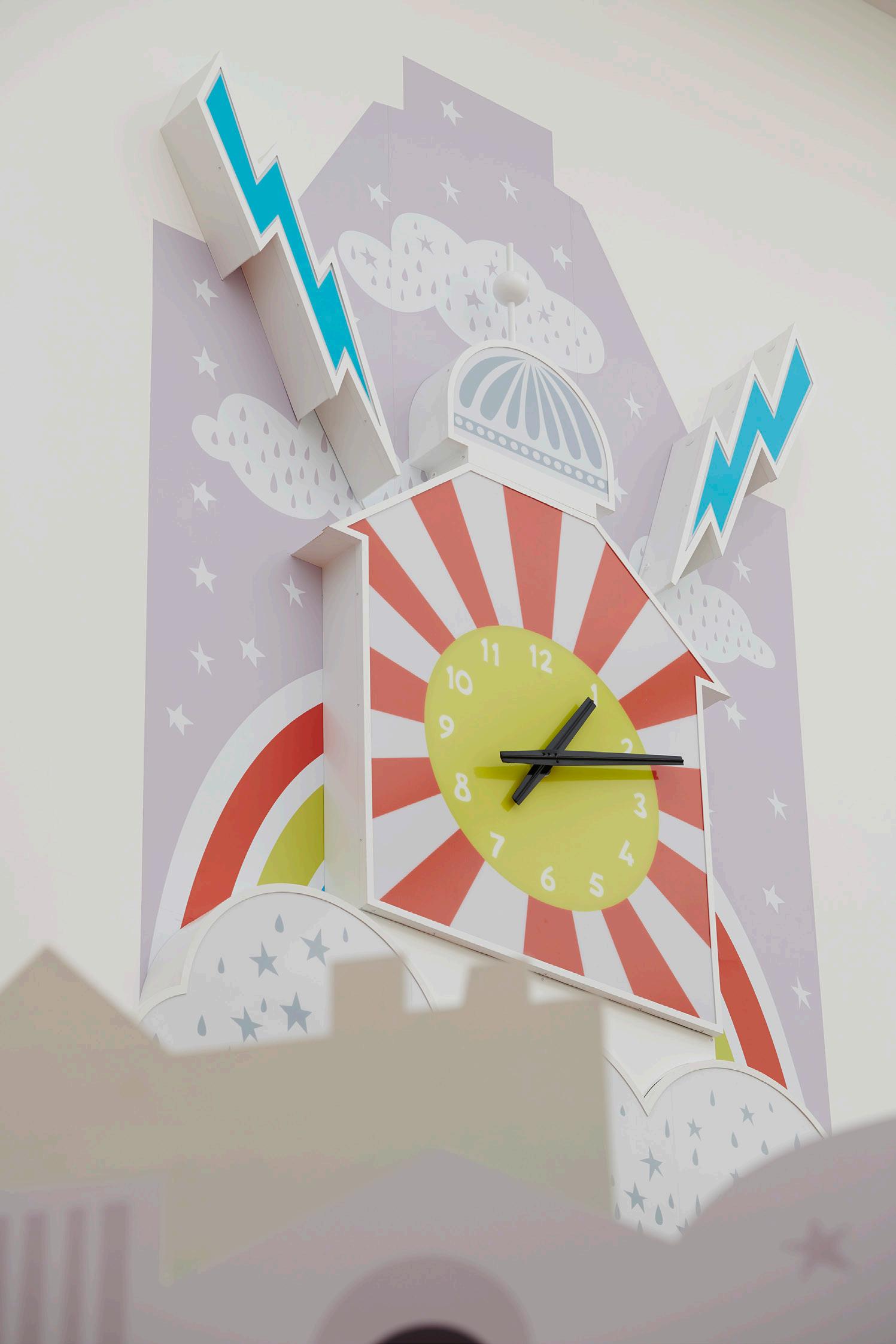

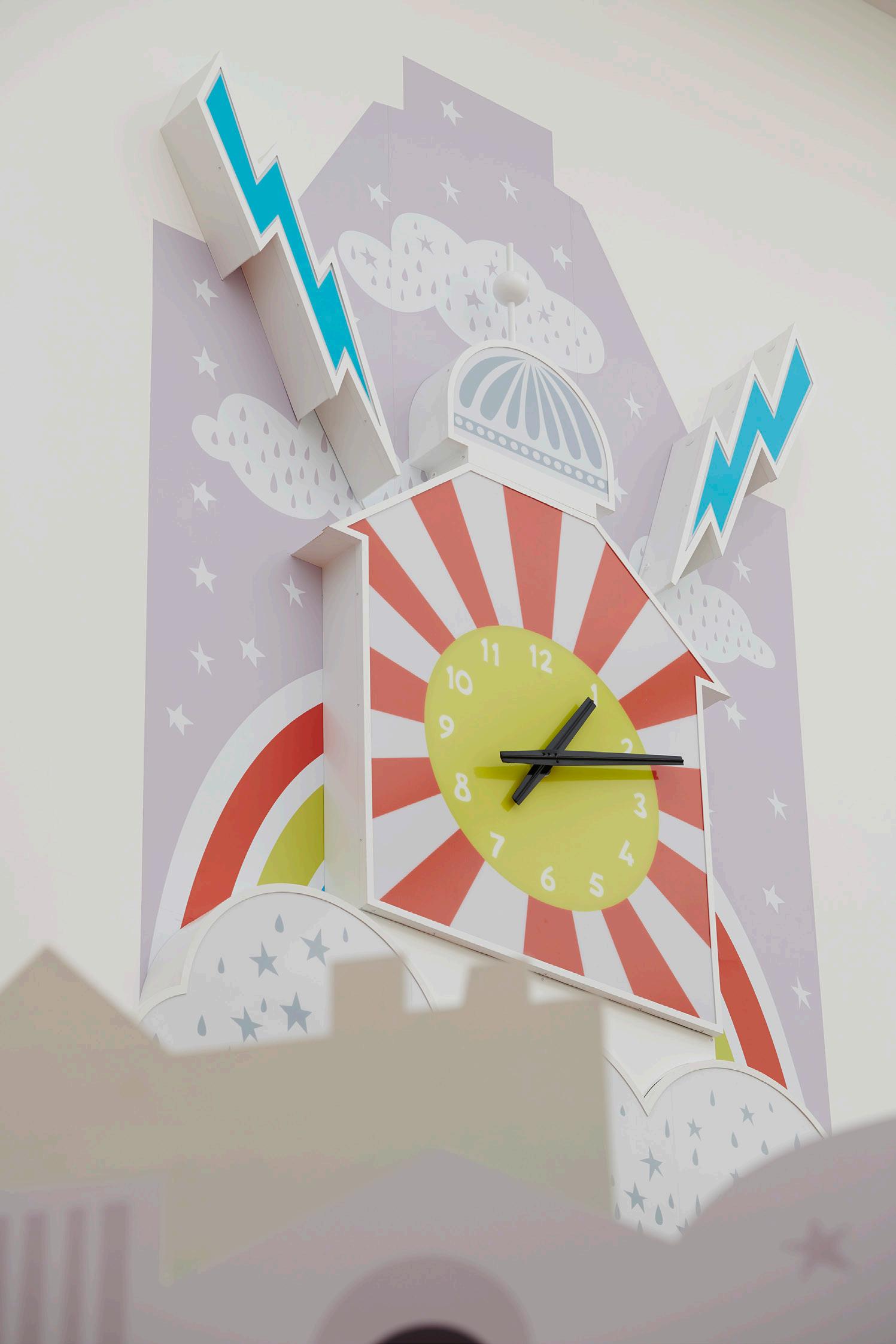

This takes the form of reimagining of the Scott Monument as a rocket

in the new Children’s Hospital waiting area (the Pod) through to details such as the Orkney Chairs in waiting areas. NHS Lothian named the wards after castles, and the trees used in the Wall Graphics are all indigenous to Scotland.

Humanising, accentuating, providing unique reference points, and placing the building in the City, are some of the things art and therapeutic design can do to reduce the stress for patients and visitors, and help staff too.

24

THE SPINE WALL

Peter Marigold

A 180 metre long glass reinforced concrete artwork running through the building guiding people into the main atrium from both external pedestrian approaches. The design depicts skin textures cast from one patient or staff member from each service.

26

27

Let’s reverse the idea that the hospital is simply a container of humans, but instead the building is created by the people who inhabit it. In this case, the skin of the occupants wraps around the building between all parts of the hospital flowing into the landscape outside. It’s the idea of skin but without identity. It could

be any one of us.

Peter Marigold, Artist

28

29

30

31

ELFA / Kevan Shaw Lighting

Design and artist Claire Hope

Abstract, transparent colour washes which are both a wayfinding tool but are also relaxing and a very striking way to welcome visitors at each entrance to the atrium.

32

ATRIUM VESTIBULES

33

VESTIBULES

EFLA / KSLD and Claire Hope

34

35

ATRIUM WALL GRAPHICS

Peter Marigold

DCN entrance: A large scale image based on a recovering patient’s angiogram developed through collaboration with Peter Keston.

37

ATRIUM WALL GRAPHICS

Peter Marigold

RHCYP entrance: A dynamic work that captures the movement derived from a therapeutic dance session held at Musselburgh Primary Care Centre. The looping shapes track each of the participant’s movements. One is the young patient Evan Glass, the other dance instructor Christina Liddell.

38

39

STAINED GLASS PANEL BEREAVEMENT SUITE

Emma Butler-Cole Aiken

A representation and development of existing work at the old hospital. This new design is based on the cycle of life: green shoots and healthy leaves; weathered branches bearing the weight and finally the inevitability of decay.

40

41

OLD TO NEW

Kate Ive

A series of portals placed at key points within corridor spaces. Each explores the identity, history and stories of the institutions as they transition from their original sites to the new building at Little France.

42

43

“I wanted to create pieces that won’t disappear into the background and so I’ve tried to put a lot of fine and hidden details into the background. That way people will be able to see things that they didn’t see before.”

Kate Ive

44

WALL GRAPHICS

Alison Unsworth

David Galletly

Rachel Duckhouse

Natasha Russell

A series of over 200 artworks throughout the whole building focussing on main corridors, reception, waiting and treatment rooms providing waymarking and distraction

46

Printmaker Rachel Duckhouse created playful designs that articulate the main corridors at key decision points.

48

49

RECEPTION DESKS

Reception desks throughout the building are enhanced through narratives developed by David Galletly and Natasha Russell

50

51

53

54

55

52 56

Natasha Russell’s intricate illustrations inhabit both reception desks and walls.

57

58

It was important to be on the ward and play areas and doing drawing activities to get feedback about the interests andcontext. We also did the same in the waiting areas in DCN with each artist working on various activities so that we could chat to people about what interested them, for example memories and reminiscences of the local area.

David Galletly

59

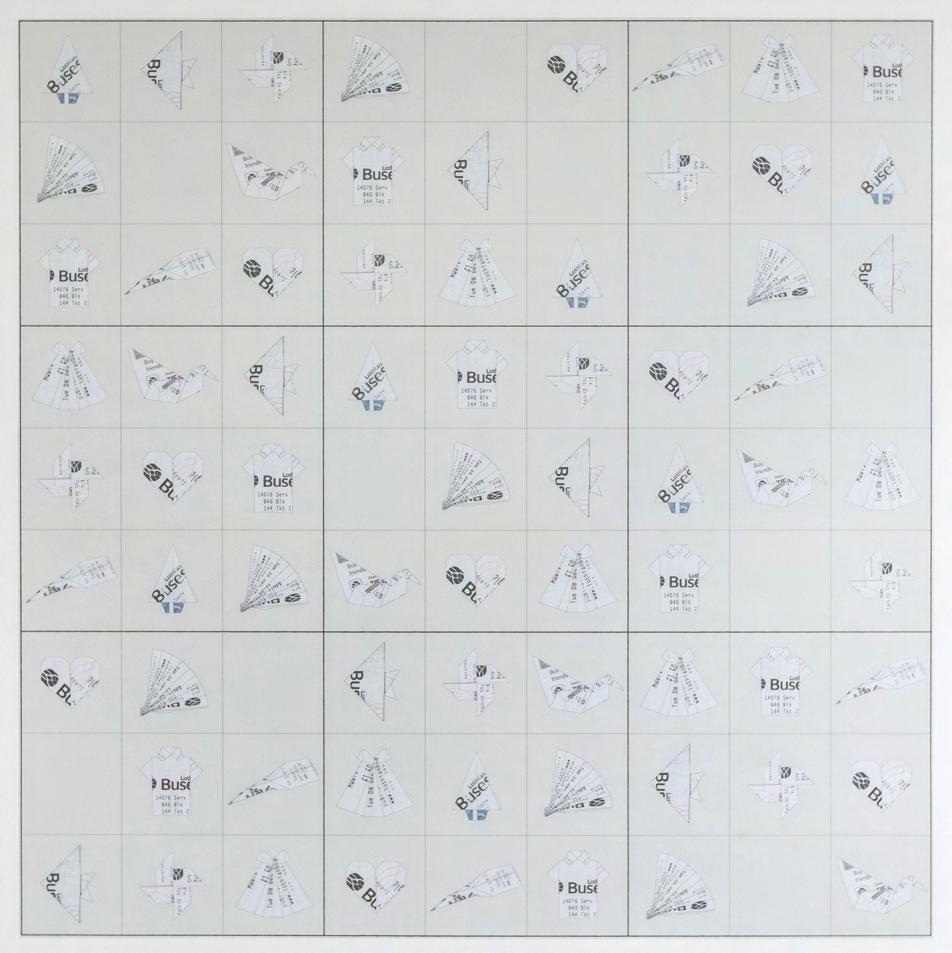

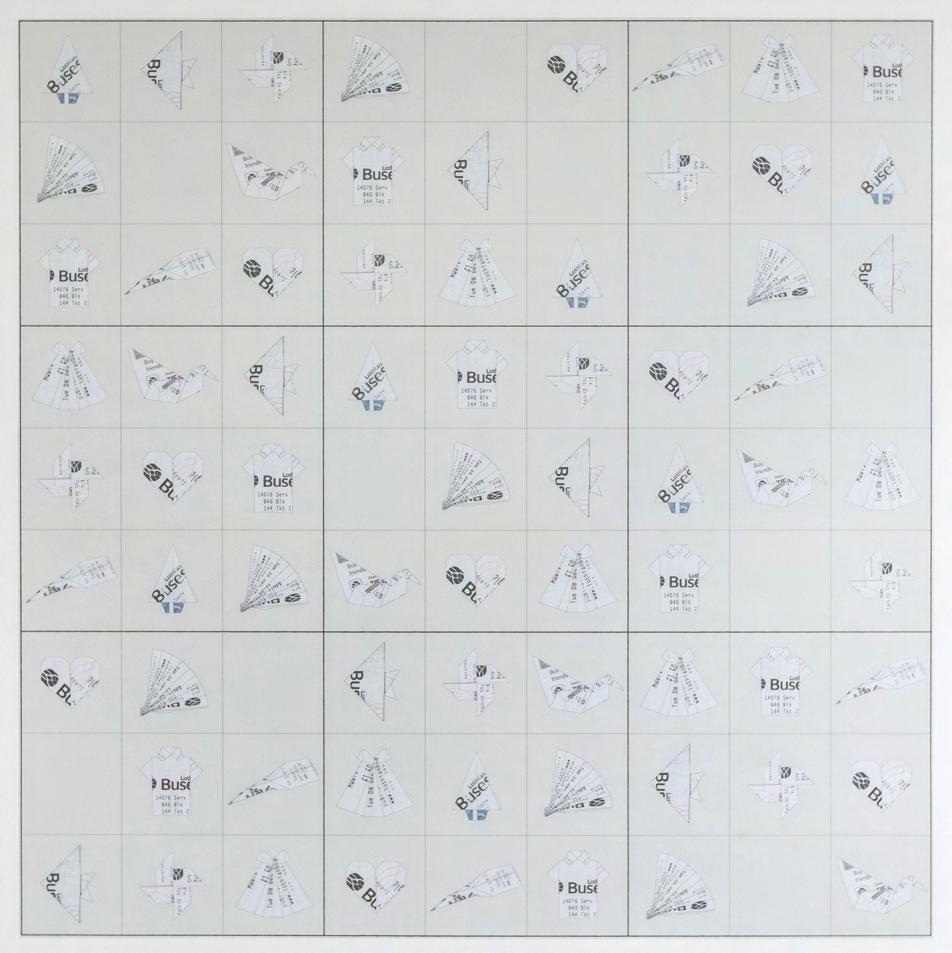

Alison Unsworth created graphic puzzles within treatment rooms and waiting areas based on five different types of objects: drinking straws, patterned paper bags, lolly sticks, bus tickets and revision/ index cards.

60

61

63

Key Collaborators

Interview Rooms, Sitting Rooms, Dress for the Weather, Andy Campbell and Matt McKenna, Architects

Waiting Areas, Adolescent Shared Daniel Ruther ford, Manager of the Children’s Hospital Charity Drop-in

Facilities and The Hub: Centre (The Hub)

Bespoke Atelier, Design Studio

Sanctuary and Sue Lawty, Artist

Bereavement Suites: Lucy Harwood, Ginkgo Projects

Child Protection Unit Dr Lindsay Logie, Consultant Paediatrician

CAMHS:

Annie Campbell

James Christian, Projects Office, Architect

James Leadbitter, Madlove

Alison Unsworth, Ginkgo Projects

Gwyneth Bruce, Head of Occupational Therapy in CAMHS

64

Why Patient Dignity and Personalisation are at the heart of Beyond Walls.

65

Before you examine the body of a patient, be patient to learn their story.

66

The Maxims of Medicine, Suzy Kassem

Being seen as an individual allows us to articulate how we can feel lost and vulnerable. Being treated with dignity and being allowed to personalise a clinical space goes a long way to making us feel like a human being rather than an illness. We most need kindness, calm and support when we are at our lowest ebb, feeling desperately worried and frantically seeking answers.

This chapter reviews work in spaces used for the some of the most challenging and difficult aspects of the work that goes on in the hospital including child protection, spiritual care and bereavement, as well as less challenging, but no less important aspects such as staying and waiting. The issue of dignity has both physical and mental dimensions and is critical to a hospital that has the range of services including the new

Children’s Hospital, CAMHS as well as DCN.

There are many ways Beyond Walls has brought a concern for dignity to the new Hospital, not least in addressing the eighteen Interview Rooms where difficult conversations take place and hard decisions are made.

Sorrel Cosens explained why these were included, “We hear such horrible stories of people who are being given the worst news of their life and what really resonates with them, when they revisit the memory, is they were sitting on a hard, plastic chair and there was a bulb that was broken.

I really think that Interview Rooms should ideally be invisible, in a very reassuring and comforting way. It’s a very traumatic time and Interview Rooms should be about giving people the time and space to think about what they’ve been

told, then compose themselves before carrying on. It’s about giving them a bit of dignity.”

Mary Murchie agreed, “It’s little things that make the difference, but they are so important. Things like changes in the lighting, comfortable furniture and a less clinical feeling to the space, but just having the space for an Interview Room where you can have a private, possibly distressing talk is such a huge bonus.”

Dress for the Weather enhanced the rooms in subtle ways. “We changed the brighter clinical lighting to softer down-lighting which is concealed behind pelmets running around ceiling. We also created mood-lighting with wall lamps. We felt it was important to work with real materials: stone, concrete, metal and wood. We added metal tables with Jesmonite tops to create

67

a sense of order in the room. Jesmonite is a concrete substitute and we used it to create a terrazzo style with stones that were picked up on a series of engagement walks around Lothian with patients and families. The tables have two levels because this is something staff flagged as being important. There’s a high part for staff making notes and a lower part for the family. This makes the space less like a consultation and more natural and comfortable.”

The attributes that might well seem ‘invisible’ are invaluable at enhancing patient dignity. Sorrel Cosens adds that one of the things she likes the most about the new Interview Rooms are the, “little design features. For example, Dress for the Weather proposed putting a mirror in so people can brush their hair, wipe their eyes and just check their appearance before they go back to their

loved one’s bedside or leave the hospital.”

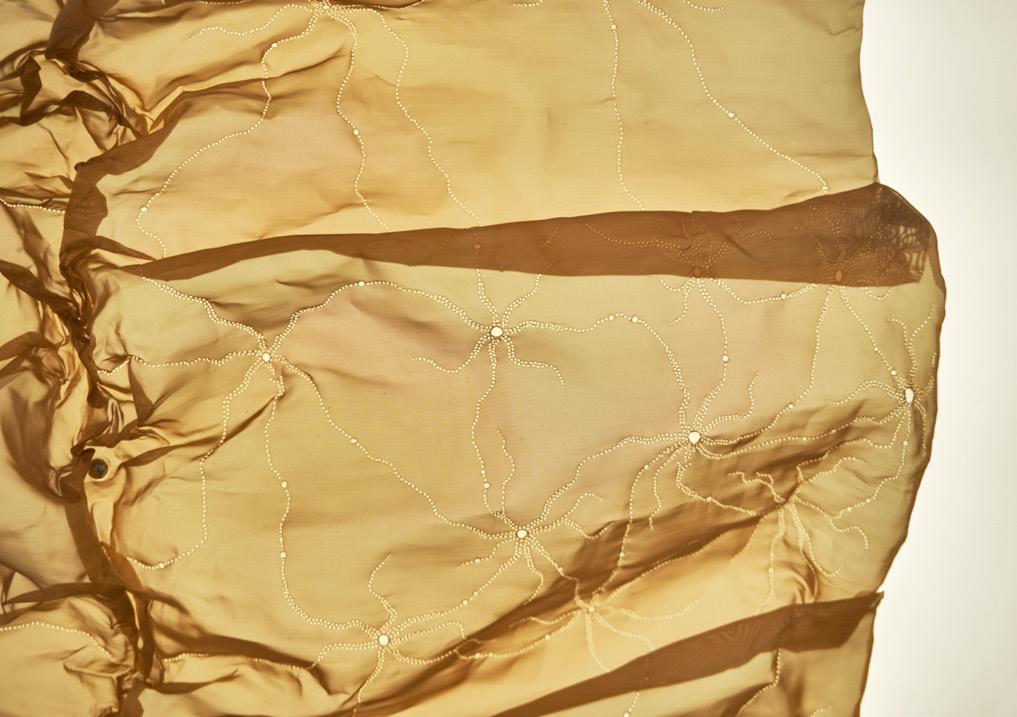

The Sanctuary in the new hospital is a multi-functional space where patient dignity is central to its identity. Sue Lawty designed a space for patients, staff and visitors of all faith communities and none, with spaces for reflecting, celebrating, and for communal activity. The spaces Sue Lawty designed provide a main space for prayer, meditation and reflection, an interview room, and courtyard which allows for movement between inside and out.

Lucy Harwood explains, “We had some initial meetings with staff from the Bereavement Services and the Spiritual Care Department. What was emphasised in these discussions was that the feeling and quality of the space was more important than specific art works. Sue Lawty quickly picked up that

the biggest impact we could have was on the building itself. We worked with HLM to change the shape of the spaces to a curved wall so the route through the space was calmer. The lighting and colour palate are soft and Sue focused on natural materials, with beautiful wooden floors and benches.

There is a wall of glass that both provides natural light, which is known to be therapeutic, and also looks out onto the courtyard. The flooring and lighting in the Sanctuary were designed to draw the eye to the outside space which people will be free to enjoy or to sit inside and admire the view if the weather is bad.”

The courtyard can be seen from a number of places in the building, including one of the two Bereavement suites, also enhanced by Sue Lawty. The

68

other suite in the Emergency Department also has a small private garden, allowing families the dignity of a peaceful place to start to come to terms with the news.

Another challenging area in the new Hospital is the Child Protection Unit, called the Acorn Suite. Dr Lindsay Logie explained that the work they do has particular requirements. “We cover the whole of Lothian and carry out medical examinations of children when there are concerns about physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect and, as a by-product, emotional abuse.

In the new Acorn Suite we will be able to have a dedicated room, which means less traffic, making it far easier to keep it as forensically clean as possible. One of our main discussions right at the beginning about having

this suite was about making the space both suitable as a Child Protection Unit but also ‘child friendly’. I was also keen to take into consideration the teenagers we see as part of that discussion. I don’t want it to just be about the younger children. I wanted everyone to be catered for and for the space to seem as friendly as possible.

Part of that is the furnishings, which are very comfortable, and that the curtains around the private area have an acorn design which is echoed in the ceiling tiles. We had chosen the name Acorn a long while ago. We wanted something attractive but both gender neutral and not age specific. Dress for the Weather picked up on that, and there are brightly coloured oak patterns. It looks less clinical whilst still allowing us to do our job. It was so helpful being able to engage

with them early on. We felt listened to and able to explain what we need from the space, not just for the children but from a staff viewpoint too. It’s a complex process and to have a well organised, friendly space is very beneficial.

We also have a distraction module with a docking station for a tablet. This allows children to control the lights. I wanted a background distraction that will allow children to be able to relax but not be too immersive as we need them to listen to instructions and questions.

NHS Lothian will be doing other work with sexual assault and young people outwith the new Hospital and so my hope is that the Acorn Suite will be able to be a learning tool for the future about how to make children feel safe.”

69

The Hub provides a domesticspace for child and adolescent patients and their families to relax in. Sorrel Cosens described the Hub as, “A space where they can play games, go on the internet and Skype their friends.

Sometimes it’s something as simple as being able to make a coffee for themselves that makes all the difference. People spend a lot to time in hospital: waiting for news or deciding next steps. There is shared decision-making to be done and providing people with privacy and spaces to do that is a luxury we haven’t had in the old hospital.”

Daniel Rutherford agreed about the need for a domestic setting, but also added that there is a requirement for flexibility of space to provide a more diverse selection of opportunities.

“The services we offer at the moment may well change because it’s an ongoing process of consultation and the developing needs of the children, young people and their families. I think having the Hub will affect the way we work. The opportunity to offer more specific support will be an enhancement. For example, we’ve got a social youth group on a Monday evening now where before there wasn’t a non conditionspecific youth group. This provides a really nice social opportunity for young people who may otherwise have been quite isolated.”

Dress for the Weather, said, “We visited the original Drop-in centre, overlooking the Meadows. We wanted to take as much of the quality and vibe of that into the new Hub. There was a danger that the kids are so attached to the Drop-in centre that they might feel a bit unsettled, so we

aimed at creating both a sense of connection and a space which was really sociable. That meant thinking about the layout and getting away from the hospital environment.

Our understanding of how children and families used the previous space was one of the drivers for us to provide an inter-connected flow and flexibility. It now looks like a domestic kitchen, dining room and living room. We enlarged the kitchen space and designed a new kitchen that is the first thing to greet you on arrival because the parents said that the old Dropin centre it was very welcoming that the kettle was always on. We also created a breakfast bar overlooking the kitchen with bar stools, as well as having tables so everyone can have somewhere to sit. Next door is much more ‘kid friendly’, and the sliding door can be kept open to keep a casual eye

70

on things but it can also be closed for privacy.

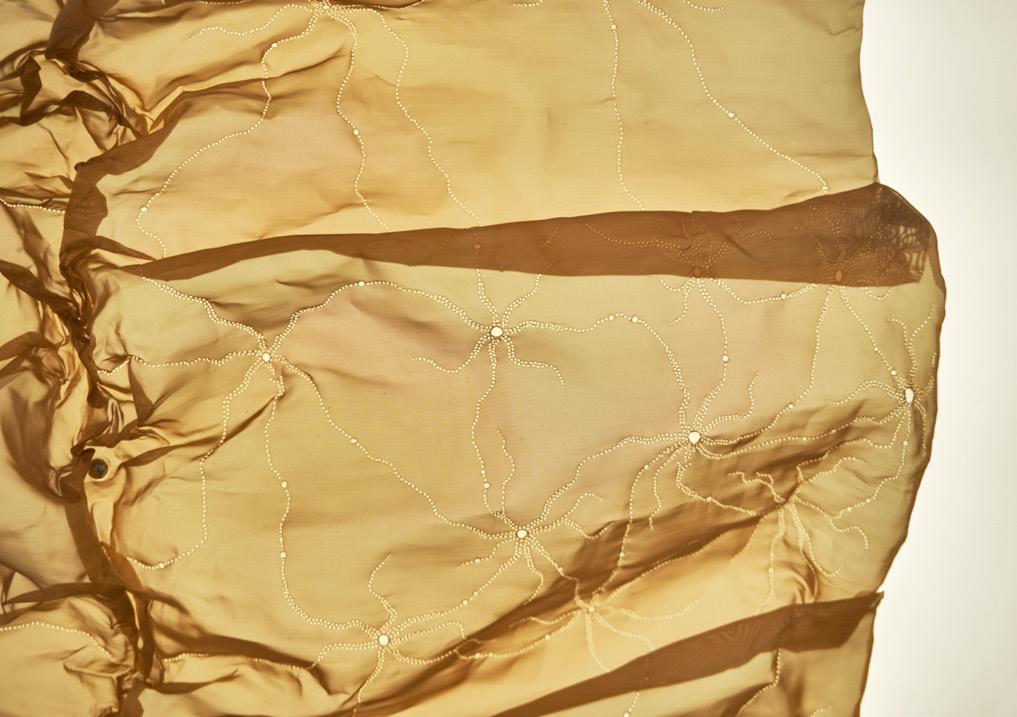

Flanking both rooms are ply-lined storage spaces, where all the workshops materials can be tidied away. We wanted to make the most of the space so they also drop down to become benches, a dining or computer table, or TV cabinet units. They serve quite a functional purpose but we worked with textile designers Bespoke Atelier to develop a pattern of animals from the zoo and plants from amongst other places the Meadows. Bespoke Atelier developed the design with young people in a series of workshops.

Dress for the Weather designed the Shared Adolescent Spaces. “If the Hub is about parents and family time, then we really wanted to make sure the Adolescent spaces were about the older kids breaking away and having their

own space. One of the things we did was to talk to them about what kinds of rooms they wanted. We took some of the adolescent patients for lunch in a couple of cafes in Edinburgh that have the kind of interiors we thought they might like and talked about how they might like and want to use the space. What came across as being important to them was colour, vibrancy and sociability but also spaces where you can tuck yourself away. They wanted the rooms, one for studying and one for being social, to be theirs.”

One of the key aims for bringing departments together in the new hospital was that physical and mental health facilities are on the same site. The new CAMHS is the amalgamation of two units which have been in different parts of the City up to this point.

One of the challenges for Projects Office was to make sure both the younger children and the adolescents felt represented whilst creating a cohesive feel to the Department as a whole.

“Prior to and since our appointment for this project we’ve been working with Madlove, an artist-led project whose big aim is crowd-sourced ideas in order to come up with designs for good mental health. We worked with James Leadbitter of Madlove who shaped the workshops programme.

We took a part of the established Madlove workshop process which encourages participants to talk quite broadly about environments and what makes us feel good. We explored the sensorial side of smells, touch, texture and things we like to look at with the staff, children and young people in

71

CAMHS. That bespoke workshop process was very much key to our approach to the project.”

Gwyneth Bruce felt that engagement process was instrumental in making the young people feel a part of the creative process. “We had lots of fantastic workshops about what the teens and primary age children hoped the Unit would be like. Projects Office worked with the staff and young people around what kind of colours and environment they found calming and soothing and the sorts of places they felt comfortable in. That was when the theme of the sea and the coast and seaside came through. Many people talked about how the colours and the images of the coast were things that they found uplifting and calming and so that’s the ideas that Projects Office have used as the basis

of their design which has been amazing.

We wanted our young people to think about the new hospital and have a sense of preparing for it, so we had them creating designs that could be integrated into the soft furnishings and table-tops. They took time looking at objects at The National Museum of Scotland who were at the time exploring what makes a sense of home, and then created prints which are going to be used. Although the specific young people who made them won’t be there, it’s really important that it brings the young people’s voices and history into it. It made this process not just for them, but about them.”

James Christian agreed that this was vital to how the process was shaped. “The brief stressed the opportunity for personalisation of spaces, so we thought a lot

about how individual identity can be taken into account within the design process.

We dealt with this in bedroom spaces by creating a piece of furniture which is a ‘safe’ wall board that allows the young person to bring their own belongings from home and personalise the space. They can bring decorative items like photographs and small objects so they don’t have to suffer from bare clinical walls. We were very fortunate that the bedroom brief did expand quite considerably, thanks to extra funding from the Children’s Hospital Charity. This additional support was in response to some of the things we fed back to them from the workshops with young people. We had a particularly illuminating conversation with the parent of a teenage inpatient being treated for her very severe anorexia. She’d been in the unit some time

72

and the parent talked about the difficulty of having nowhere to sit comfortably in the room and just talk. From a very early stage we had the desire to facilitate normal conversation in the bedrooms. It was great that the charities really wanted to go that extra mile to personalise the space. We created, in some of the rooms, an upholstered bench window seat which can be pulled out so that it, combined with a desk chair, enables more natural seating arrangements for conversation. They also have a television on the wall, bespoke furniture including a desk and seating, curtains and colour on the walls with the ambition to create a much more dignified environment.

We were keen to incorporate seating into some of the other spaces that might be used for visiting families. In the Games Room we created a seat in a nook

and that, combined with the moveable furniture, allowed those corners to be used more naturally for visits. One of the things we were told in engagement was that often the young person will not admit that they are very unwell and so it was important that although the rooms weren’t sterile, the space had to communicate comfort but not a ‘home.’ We used quite bold colour schemes to strike a balance between the clinical and domestic.

Throughout the space we also had to balance comfort and privacy with safety.” Gwyneth Bruce agreed this was vital. “The real challenge about creating this Unit is that it would be easy to make it ultra-safe, but if it looks too clinical then it’s not at all ‘young people friendly.’ We wanted to use good colours and scenes of the coast and the seaside and all of the things that the young people

said gave them a lift, but at the same time we had to make sure that things were safe and people could see that support was around them. I think Projects Office have done an amazing job. They brought someone along who facilitated things and they’d obviously put a lot of planning and thought. They seem to have really listened and very thoughtfully gone away and created amazing furnishings and décor. They’ve clearly kept in their heads all the staff have said about the importance of being able to look after the young people in this very vulnerable time in their lives.”

James Christian continued, “In the Dining Room space and the Inpatient open space we have allowed for private booths that staff can still monitor and keep people safe. In all of the design for Mental Health work we undertake we are keen to explore ideas of privacy. That can range

73

from solitary spaces where people can feel that they are alone; intimate spaces where you might have a conversation with a couple of people; and group open spaces where activities take place and there is more action. With group spaces we always try to create opportunities where someone can retreat from the action. In the Inpatient Open Space there’s a central table and seating for activities, but the storage wall has a recess in it so you can observe the activities taking place but not feel you have to be part of it if you are feeling overwhelmed.

The Inpatients Open Space is quite large, and we wanted to make it as friendly as possible. In every workshop we undertook about the places that make people feel good, there was an overriding theme of the coast. There is also, in one of the original buildings, a very important artwork of a lighthouse

which is a memorial to a member of staff. So we were able to take these two ideas and combine them in a strategy for the unit. That memorial lighthouse is now one of these retreat spaces. The lighthouse anchors the space and provides privacy but the windows are angled so that the staff can ensure patient safety as well.

The sea and coastal theme continues throughout the space but we wanted to give each age group their own sense of identity. The adolescent spaces are offshore with slightly stronger colours. The ‘under eleven’ spaces, the Rainbow Unit, references East Coast Scotland seaside towns with brighter colours. We’ve designed the artwork in the circulation spaces to pick up on the coastal themes. We use the lighthouse motif throughout along with seaside buildings. In the young people’s

spaces and the main waiting area the lighthouse leads the boats into the shore, emphasizing safety and protection.

It’s a challenge designing for a Mental Health environment, but what we did learn was to take forward the lessons from engagement and be ambitious about what we wanted to achieve.

Conclusion

Dignity and personalisation is a complex and multifacetted challenge – fundamentally it is at the heart of developments such as ‘realistic medicine’ and person-centred care. The evidence for the impact of personalised and respectful care by health professionals is substantial and this can be demonstrated through environments as well. Art and Therapeutic Design can make a significant contribution,

74

but the challenges cannot be underestimated. Through this thread of work for the new Hospital we have seen how artists and designers can deinstitutionalise aspects of the healthcare environment, even in some of the most challenging areas such as CAMHS, the Child Protection Unit, Bereavement Suites, and Interview Rooms. This has to be done without compromising safety or in some cases forensic requirements. The approach taken throughout has focused on understanding the needs of users through engagement and co-creation. The significance of this is highlighted by the way that the principle funder, the Children’s Hospital Charity, listened to the feedback from the workshops focused on the CAMHS and substantially increased funding to enable a more comprehensive approach to the needs of users.

This focused on simple domestic needs such as a place for visiting family to sit in a bedroom or have a cup of tea together, or for the kitchen area to be the welcoming face of the Hub. These domestic aspects significantly change the experience of the hospital.

The co-creative approach generated many aspects of the aesthetic, such as the seaside theme, but it also ensured that the functionality was informed by users. Dignity doesn’t just mean de-institutionalising the look and feel of the spaces – it means putting the needs of the patient, their families and carers at the heart of the design.

De-institutionalisation is one of the key ways to affect perceptions of healthcare, and is achieved through effective interior design. Most often the spaces that will make a difference are non-clinical spaces – places where people

wait and meet with clinical and nursing staff. Making these spaces more ‘human’ through use of different colours, patterns, types of furniture as well as with artworks has a significant impact. The converse, as noted by Sorrel Cosens above, is abiding memories receiving bad news sitting on a hard plastic chair or standing in a corridor. The ambition that she goes on to articulate, that these spaces go unnoticed, invisible, is perhaps the clearest statement of the challenge for art and design.

75

and their families.

76

THE HUB Dress for the Weather

A flexible meeting, dining and work space for young people

77

We worked with textile designers Bespoke Atelier to develop a pattern of animals from the zoo and plants from amongst other places the Meadows. Bespoke Atelier developed the design with young people in a series of workshops.

Andy Campbell, Dress for the Weather

79

INTERVIEW ROOMS

Dress for the Weather

A series of Interview rooms located around the building designed with hand crafted elements, furniture and controllable lighting.

10 80

82

It’s little things that make the difference, but they are so important. Things like changes in the lighting, comfortable furniture and a less clinical feeling to the space, but just having the space for an Interview Room where you can have a private, possibly distressing talk is such a huge bonus.

Charge Nurse, DCN Outpatient Department

83

SHARED ADOLESCENT SPACES

Dress for the Weather

Two spaces, one for socialising and one for study have been designed as vibrant, colourful spaces in discussion with teenagers.

84

85

86

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT MENTAL HEATH UNIT Projects Office

A bold and vibrant enhancement of social, dining, work, bedroom and courtyard spaces based on a coastal theme providing for dignity and personalisation.

88

89

90

91

92

93

95

96

98

99

101

102

103

People talked about how the colours and the images of coast were things that they found uplifting and calming.

Projects Office

105

106

107

ACORN ROOMS

Dress for the Weather

Two rooms forming part of the Child Protection Unit designed to enhance privacy and distraction

108

THE SANCTUARY AND BEREAVEMENT SUITES

Sue Lawty with Ginkgo

The non-denominational spaces

Sue Lawty designed provide a main space for prayer, meditation and reflection, an interview room, and courtyard which allows for movement between inside and out.

110

111

112

The flooring and lighting in the Sanctuary were designed to draw the eye to the outside space which people will be free to enjoy or to sit inside and admire the view if the weather is bad.

Lucy Harwood

114

115

116

119

Key Collaborators

Restaurant:

Emma Varley, Artist

Multi-Sensory Design & Distraction: Alex Hamilton, Lead Artist

Oli Mival, UX Research & Design

Derek Kemp, Audio Visual Consultant

Helen Fisher, Communications Consultant

Yulia Kovanova, Curator

Film makers: Nim Jethwa, Jack Lockhart, Kris Kubik, Tracey Fearnehough & Holger Mohaupt

Tony Kimera, Occupational Therapist

Radiology:

Alison Unsworth, Project Manager

David Galletly, Artist

Sarah-Jane Selway, Radiographer

Multi-Sensory Room: Southpaw, Multi-sensory equipment provider

The Pod & RHCYP Waiting Daniel & William Warren with Alex Fitzsimmons, Designers & Dining Areas: Emily Hogar th, Artist

Guy Bishop, Ar tist

Touzie Tyke, Animation Studio

DCN waiting & sitting rooms

Dress for the Weather (Matt McKenna & Andy Campbell) & RHCYP sitting rooms: Catherine McDerment, Lead Occupational Therapist/Children & Young People Strategic Lead

References:

Kaplan Attention Restoration Theory

Belfiore & Bennett, Social Impact of the Arts

Debajyoti Pati, writing on Positive Distractions in Healthcare Design (2008 Report from Cornell)

120

Effective Distraction Techniques and their Therapeutic Effects.

121

Wonder (noun)

A feeling of amazement and admiration, caused by something beautiful,remarkable, or unfamiliar.

Wonder (verb)

Desire to know something; feel curious.

122

In a hospital setting distraction is a very useful therapeutic tool. Beyond Walls demonstrates a plethora of distraction techniques. These range from artworks to contemplate whilst you have a cup of tea through to works developed in close collaboration with Clinicians, Nurses, Radiologists and Therapists to take a patient’s attention in a very specific way during treatment or in the process of rehabilitation.

On the fourth floor is Emma Varley’s ‘Garden of Dreams’. It’s situated in the restaurant which is open to all and provides the chance for a moment of whimsy, reflection, calm and yes, sitting over a meal or a drink and just dreaming.

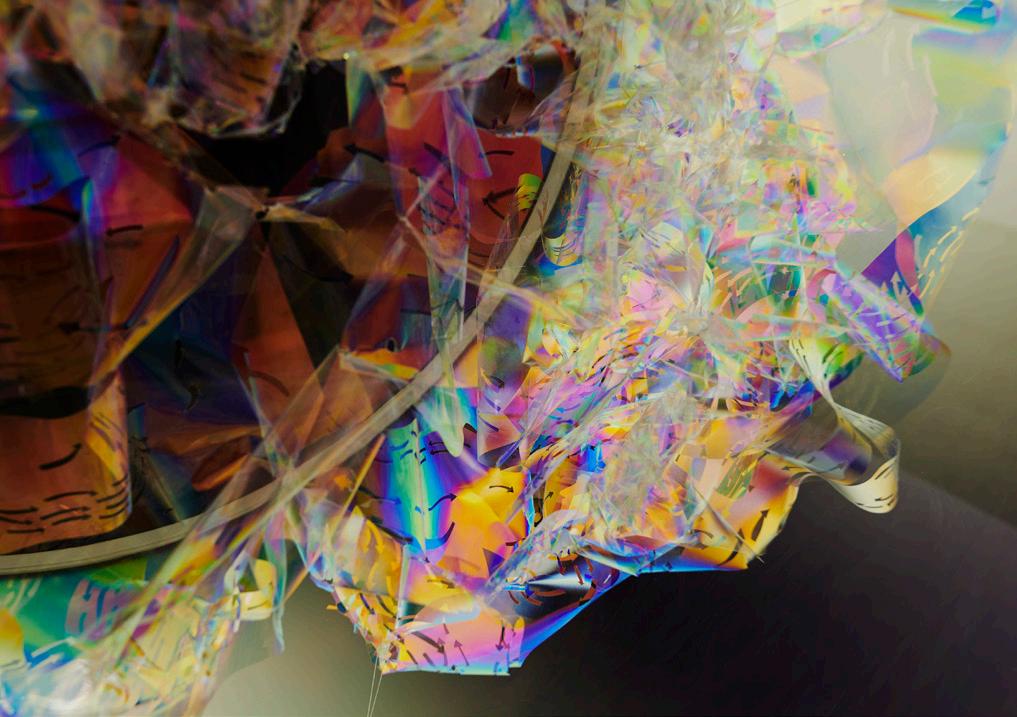

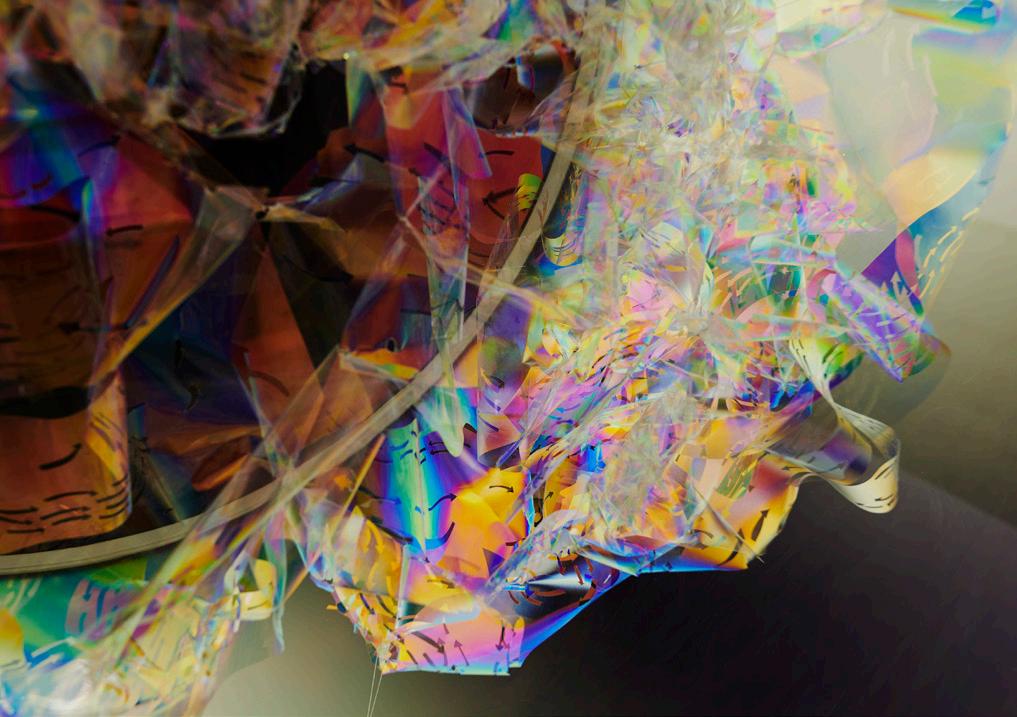

As Emma says, “The work unfolds over six large scale light boxes which are a re-interpretation of the existing stained glass from the

old Children’s hospital. The final artworks are real and imagined; snapshots of a wider landscape captured in portrait format to emphasise elements of strata linking to the local Lothian environment. Scottish flora and fauna dominate each scene, the hare perched up high keeps watch over the Scottish meadows whilst being observed by the sun. A view over Loch and Glen with a spring rabbit and swan who observe a single weed bearing its intricate root system, referencing energy and power echoed by wind turbines and the moon. A stag and eagle look towards the mountains protected by the Willow pattern plate – a reference to dining, storytelling, love and escapism.”

As with all the projects, engagement was an important part of the process. Emma says “Creative engagement with the patients inspired ideas

of escapism, developing around stained glass and the intensity of light as projected colour. Using an overhead projector, we explored light collages, placing coloured glass, translucent papers, found and personal objects on the surface to create ‘dream-scapes’.”

Yet distraction, in therapeutic terms, can be much more than an escape. In the Multi-Sensory Design project there is a range of distractions to specifically aid treatment as well as rehabilitation. This is a example of taking something that already has a proven track record within the old Hospital and building on it for the benefit of all patients within the new hospital.

The ‘Secret Garden’ in the old Hospital was an art installation designed to engage children for therapeutic purposes. As Catherine McDerment says,

123

“The Secret Garden was a ‘first generation’ interactive distraction commissioned with funding from the Children’s Hospital Charity about ten years ago and designed by Falling Cat with a lot of engagement with children and staff. What we wanted was the ability to add more diversity and the ability for the system to grow and adapt. The ambitions for the possibilities of the new system came from the great success of The Secret Garden. The staff knew what worked well and knew what they wanted to improve, adapt and add.”

As the new system will be part of the combined hospital, it was important that all the Departments were brought on board for the planning stage. Engagement with DCN was particularly relevant because Secret Garden had been part of the old Children’s hospital.

Janice MacKenzie said, “One of the successes we’re building upon is the Multi-Sensory work for therapy, both in Children’s and in DCN. I think, initially, DCN were a bit sceptical that there would be any benefit for their patients. However, it was, to use the cliche, ‘the journey’ the Therapists went on to actually see the real benefits and how it could be adapted for their patients.”

Alex Hamilton, Lead Artist on Multi-Sensory Design and Distraction agrees completely.

“A lot of our initial consideration about this project came from the existing Secret Garden programme. This was a very early use of this technology and we were excited to develop the Multi-Sensory Design and Distraction programme as the next steps in the cutting-edge future for these therapeutic techniques. It also meant that a lot of staff were immediately

involved and on board as they had confidence in the technology and were excited to explore and help us push the boundaries to give the best patient experience possible. The Therapists and Support Staff were incredibly generous with their expertise about what would be beneficial for all the variety of patients, their needs and particular challenges.

The brief identified a need for digital media being projected and used in a variety of different ways to engage patients, providing entertainment, exercise and as part of a recovery programme. I and the team (Oli Mival, Derek Kemp and Helen Fisher) created the programme for three Therapy Rooms, two in the new Children’s Hospital, and one in DCN, as well as forty-six Treatment Rooms. We had a lot of engagement with the staff. We wanted the programme to be an addition to the existing ‘tool

124

kit’ rather than being seen as a replacement. The main focus was to enhance the patient experience and help the staff do the best job possible.

The Therapy Rooms have three projectors. One of the projectors is set up to project onto the largest wall on any of the three rooms and will draw imagery from the film library. It’s there to produce a more calming, relaxed environment.

The other two projectors are set up to allow much more sophisticated, interactive Apps to be presented on another wall. There is a camera to catch a patient’s movement and translate that into different games and exercises to encourage correct posture, movement and exercises but in a fun, distracting way. The last projector will project onto the floor to allow other types of interaction. This will allow the staff to work with whatever particular

needs the patient has. For example, in DCN, with the help and advice of many members of staff including Tony Kimera, the set up will address the particular practical needs within patient recovery such as learning to walk again. This projector will allow the patient to feel as if they are engaging in everyday situationslike walking through a shopping mall or garden centre; climbing steps to get onto a bus; or navigating around furniture in different rooms at home.

Each Treatment Room has a laser projector projecting imagery from the film library onto the wall or ceiling, depending on which way the patient needs to be positioned.

The Film Times contains three strands of commissioning curated by Yulia Kovanova and Alison Unsworth.

Film Times

Strand One: Commissions for Artists and Filmmakers

Kris Kubik produced four 5min films using wildlife footage, including footage of birds in a coastal landscape, footage of bees and other insects and close up footage of birds. The films are suitable for multiple age groups. Whilst some focus on creating an atmosphere of calmness and relaxation, others are fun and playful, with some surprises and vivid colours.

Nim Jethwa spent 11 days filming in locations across Edinburgh to film content which he edited to create the film ‘A Little Edinburgh’.

Jack Lockhart created four 10-minute films, from collaged video, photographs, painting and animations of the beach. Three

125

films are designed for young children aged 0-5, and one is designed for a broader age range including adults. A character encounters kites, boats and sea animals during the first three films. The fourth is a relaxing film using beach and seascape imagery and a soundtrack of wave sounds.

Holger Mohaupt and Tracey Fearnehough worked with Jupiter Artland to run a series of workshops for a group of 6-8 children aged between 7 and 11 years old within the Jupiter Artland setting, exploring the themes of water, breath and wind, things that grow, animals and light.

Strand Two: Commissions for Creative Curators

Matt Lloyd, Director of Glasgow Short Film Festival, selected a series of short animations from

GSFF’s Family Animation Programme, intended to relax, focus or engage patients. He also produced a series of short films using content from ‘Everything’ a game created by Irish animator David OReilly.

Adam Castle, Curator, ran an open call for film submissions for the film library through Edinburgh Artist Moving Image Festival networks and received more than 400 submissions. He selected a number of these films along with a curation of other short films around the functions of focus, relax and engage.

Strand Three: Open Submission

Just under 50 film submissions were received from an open call. Staff and/or patients at RHCYP and DCN were invited to be involved in the selection of a wide range of content and creative approaches.

The films are grouped through an accessible interface as:

• Relax - feel less stressed about procedures;

• Engage - be ready to listen and follow instructions; and

• Focus - keep a particular part of the body still.

This is a bespoke very nuanced system which will continue to grow and adapt whilst allowing staff to choose options which will best suit a particular situation for an individual patient.

The other important aspect of the Multi-Sensory Design and Distraction was the provision of storage in order to provide a calming, therapeutic workspace. We utilized the expertise of Interior Designer Paula Murray to create storage that would allow all the clutter of vital equipment to be tidied away.”

126

Another area where distraction is a useful therapeutic tool is the multi-sensory room which was developed by Southpaw. A multi-sensory room is a controlled environment which is specifically designed for Sensory Therapy. Sensory experiences can include touch, movement, body position, vision, smell, taste, sound and the pull of gravity. Depending on the particular needs for each patient, it will be adjusted to be as soothing or stimulating as required.

One of the great strengths of Beyond Walls is the multi-layered, nuanced approach to the four themes of Wayfinding, Distraction, Personalisation and Dignity. For NHS Lothian and the Funders it was always vital that the programme was integrated into the fabric of the new build and always had the patient at the heart. Janice MacKenzie NHS Lothian Project

Clinical Director said, “We want the Art and Therapeutic Design to deliver a building which is special and very memorable to people. That it would be a nice place for patients and their families to be and for staff to work in which didn’t feel like a hospital.” This integrated approach means that although projects have been highlighted in one chapter they will often have aspects of another.

This is the case with the Wall Graphics work of Alison Unsworth and some of the work of David Galletly. Alison’s work can be seen in waiting rooms and treatment rooms within the various departments. Alison explained that for her distraction is all about the context and environment of the particular room. “My Wall Graphics are all picture puzzles with five different types of objects: drinking straws, patterned paper bags, lolly sticks, bus tickets and revision/

index cards. I created a type of picture Sudoko, with gaps for you to work out. There are different ways you can engage with them. You can look at it carefully to work out the puzzle, you can then expand the pattern. You can draw or make it. You can also create your own ideas. For example, I made Origami objects out of bus tickets, and then hand drew them. I have very happy personal memories of sitting with my Gran whilst we waited for my sister who was taking part in competitions. She taught me how to make Origami boats with nothing but a packet of lottery tickets. As an experienced artist I’ve worked a lot in gallery education and with school children and often the most amazing results you can get with groups are when you limit them to one item. I wanted to create graphics for the hospital waiting rooms that people could join in with by using what they might

127

have in their pockets.”

David Galletly’s work is more focused on distraction techniques for various interventions and treatments. Sarah-Jane Selway talked about how early engagement and an open dialogue between staff and artist can produce exactly what a department is looking for in terms of therapeutic distraction.

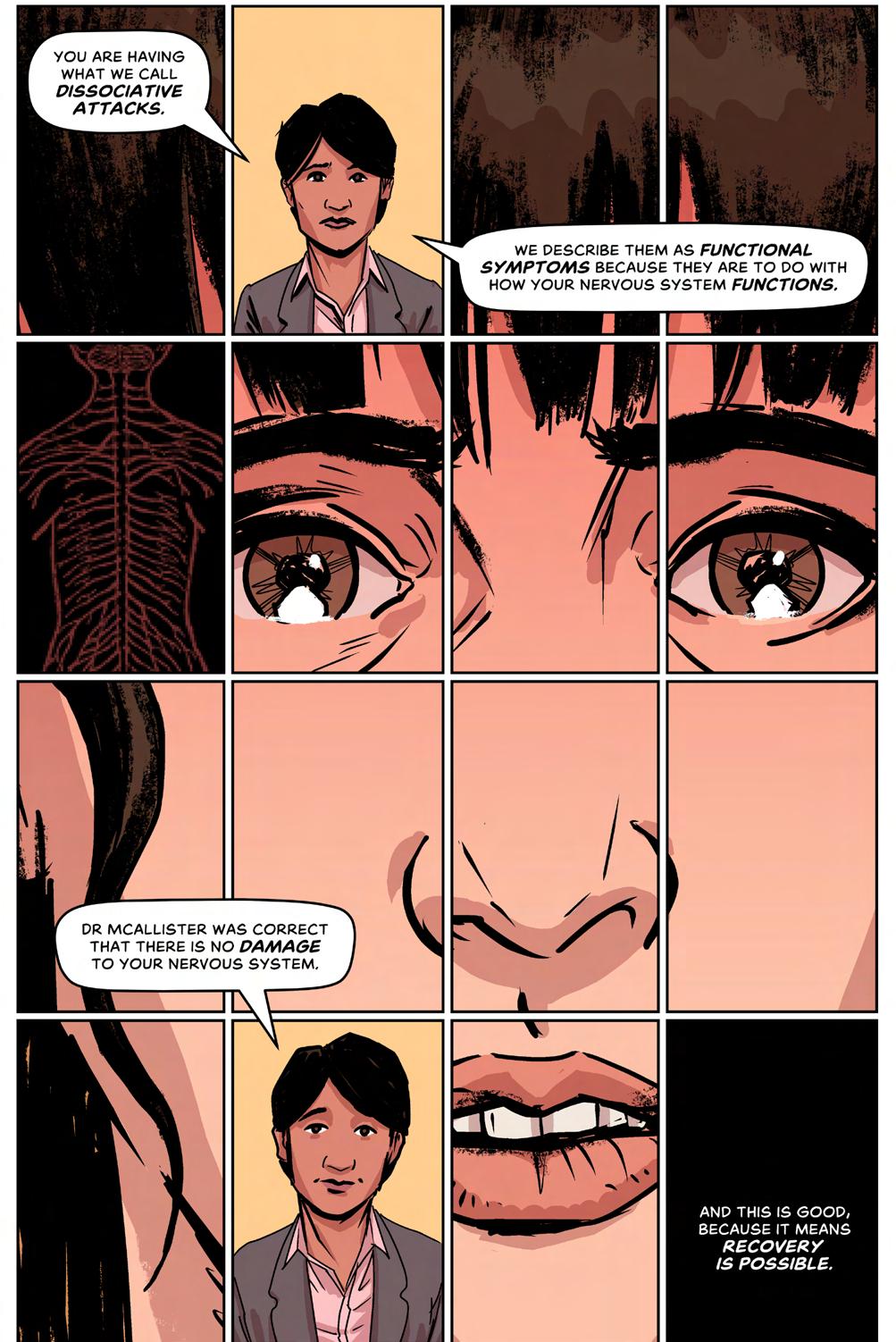

“I got involved because radiology needed artwork for all its rooms. I became quite active in making that happen and then working with the artist to develop it. Early engagement is vital so that the artist can get a better understanding of how we use each room and tune into what our requirements were going to be. For us the art on the walls is really an essential tool. We use it all the time. Firstly, it’s a way to get a child into the room and making them comfortable. Secondly, it