10 minute read

Lizania Cruz

from GIRLS 11

Lizania Cruz is a Dominican participatory artist, designer, and curator interested in how migration affects ways of being & belonging. Through research, oral history, and audience participation, she creates projects that highlight a pluralistic narrative on migration. Cruz has been an artist-inresidence and fellow at the Laundromat Project Create Change (2017-2019), Agora Collective Berlin (2018), Design Trust for Public Space (2018), Recess Session (2019), IdeasCity:New Museum (2019), Stoneleaf Retreat (2019), Robert Blackburn Workshop Studio Immersion Project (SIP) (2019), A.I.R. Gallery (20202021), BRIClab: Contemporary Art (2020-2021), Center for Book Arts (2020-2021), and Jerome Hill Artist Fellow, Visual Arts (2021-2022). Her work has been exhibited at the Arlington Arts Center, BronxArtSpace, Project for Empty Space, ArtCenter South Florida, Jenkins Johnson Project Space, The August Wilson Center, Sharjah’s First Design Biennale, Untitled, Art Miami Beach, and CUE Art Foundation, among others. Most recently she is part of ESTAMOS BIEN: LA TRIENAL 20/21 at el Museo del Barrio, the first national survey of Latinx artists by the institution. Furthermore, her artworks and installations have been featured in Hyperallergic, Fuse News, KQED Arts, Dazed Magazine, Garage Magazine and The New York Times.

Image courtesy of Manolo Salas

Advertisement

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. It took place in July 2021.

GM: What was your path to becoming an artist?

LC: I always wanted to be an artist. When I was a teenager, I was painting and had a hard time convincing my parents that I could make a living from art. I also wanted to go to Altos de Chavón School of Design in the Dominican Republic; it had an untraditional reputation, so my parents were really against me going there. I started studying advertising in a different school, and then I applied behind their backs and got in. At that time, it was hard to get in because they only accepted around 50 people and the school only had fashion design, art/illustration, and graphic design departments. So I ended up convincing my parents. The graphic design department really excited me because they were doing more conceptual things, and at that time I really didn’t know what type of artist I was. I was still developing, and the art program was very specific. They were painting and doing sculptures, but I was interested in telling stories in a different way, so I ended up switching majors and doing graphic design. I worked as a graphic designer for around 8 years, and I started working more with immigrant communities as a graphic designer trying to use design in order to talk about different oppressive systems. I was also figuring out ways to do political education through design, as well as working with organizations that were using publications and other participatory design elements in order to engage folks into organizing. From there, I started to work more on my own projects that had a similar vision, which is addressing immigration and belonging from a perspective of participation and putting people at the center. Once I started doing [artist] residencies, one thing led to another.

GM: How do you center on Latinx themes and identity in your interdisciplinary practice?

LC: I think of materials and processes and what will be the best approach to bring across a concept. It’s interesting because that’s just who I am – I would consider myself more of a Caribbean woman than a Latina or Latinx woman, and we can speak about those [identifying] terms and why I feel that way. I’m a lightskin Black immigrant woman [living] in the U.S. and I’m here on an artist’s visa. I have a ton of privilege within that system because I have documentation. What I try to focus on throughout my practice is thinking about plurality and how we can create more stories that address or dismantle a monolithic view of what a Latinx person or immigrant is. So I always try to think of pluralistic approaches to narratives and storytelling. I believe in a politics of differences and how we can embrace our differences in order to understand how we are interdependent.

Installation view of Lizania Cruz's solo show In Search of Motives (April 23 - May 23, 2021). Photo by Sebastian Bach and courtesy of A.I.R. Gallery

GM: Do you want to touch on your hesitation surrounding identifiers such as “Latinx” and “Latino/a”?

LC: There are a lot of conversations around identifying terms because there are so many and so many different viewpoints. I appreciate the push to make the term “Latino/a” gender inclusive and be more aware of the expansive community that is Latino/a/x. […] My whole thing with the term “Latino/a” is that it is a term that was prescribed to the region and us, rather than a term that we started ourselves. I think that the term “Latinx” is trying to move into a direction of using a term that feels more representative of the current moment in the community. But I have issues with the term “Latino/a” because of its history. [While] I belong to this larger umbrella, I feel very Caribbean at heart.

GM: What could art spaces do to better represent Latinx and Latin American people on a systemic and programming level?

LC: I don’t even know where to start! The thing is, a lot of the people that are represented in these high level institutions are within the selective few. The biggest step is first, how can we dismantle this idea of the selective few, and two, what are the barriers of entries that exist in these high level institutions? A huge barrier that people don’t talk a lot about is academia. Why is academia so legitimized for people to even be able to work within institutions? Not everyone can afford to go to school, and not everyone can afford to have a Master’s degree. We have to shift the way that we consider what knowledge is legitimate [enough] to be a part of an institution. When I say “knowledge” , [I’m referring to] so much knowledge in Latin American culture that is Indigenous, Afrocentric, and not rooted in the white, colonialist system that is academia. […] I know there’s a ton of talk about transparency, but we need to know where the money is coming from, who is on the staff, who is and isn’t an intern, and who’s getting paid what. Once we know the real transparency of the machine, we’ll be able to hold more people accountable.

GM: Could you talk about the work that makes up your current solo exhibition at CUE Art Foundation, “Lizania Cruz: Gathering Evidence: Santo Domingo & New York City” (2021)?

LC: I feel super grateful because I was able to work with Guadalupe Maravilla as a curator-mentor, and it has really made me think a lot. 90% of the [exhibited] work is in Spanish, as language is a huge barrier for certain folks. I live in New York City, where Spanish is a language that you hear people speak everywhere. But it has also been really great to work with someone that [knows the] historical context of the diasporas [affected by] U.S. involvement in Latin America. I’ve been working on a project titled “Investigation of the Dominican Racial Imaginary” , which looks at how the nation-state in the Dominican Republic created this historical narrative that has been imbedded in our identity and in the way that we share history that has repressed and erased African heritage from our identity. In this investigation, [I’m also] looking at our relationship with Haiti and how the creation of the [Dominican Republic] nation-state comes from the idea that we are not Haitian. So “other-ing” became a mechanism of creating a separation from Haiti.

GM: I’m sure this wasn’t intentional on your part, but Haiti is a polarizing topic right now due to everything that went down with the recent assassination of Jovenel Moïse, President of Haiti.

LC: […] I’ve been working with archives and the archival history [of the Dominican Republic] for this project. So when [the assassination] happened, so many people that know about my project texted me, “Oh

my god! Can you believe this is happening?” I’m not a historian, but once you start working with the archive, you see how history repeats itself over and over again. I feel that this project really looks at how the history of the Dominican Republic has been constructed by those in power to specifically address a creation of an identity, as well as separate that identity from Haiti. These are folks that we have roots with because we were on this island together and we fought colonialism together in many instances. (Continued)

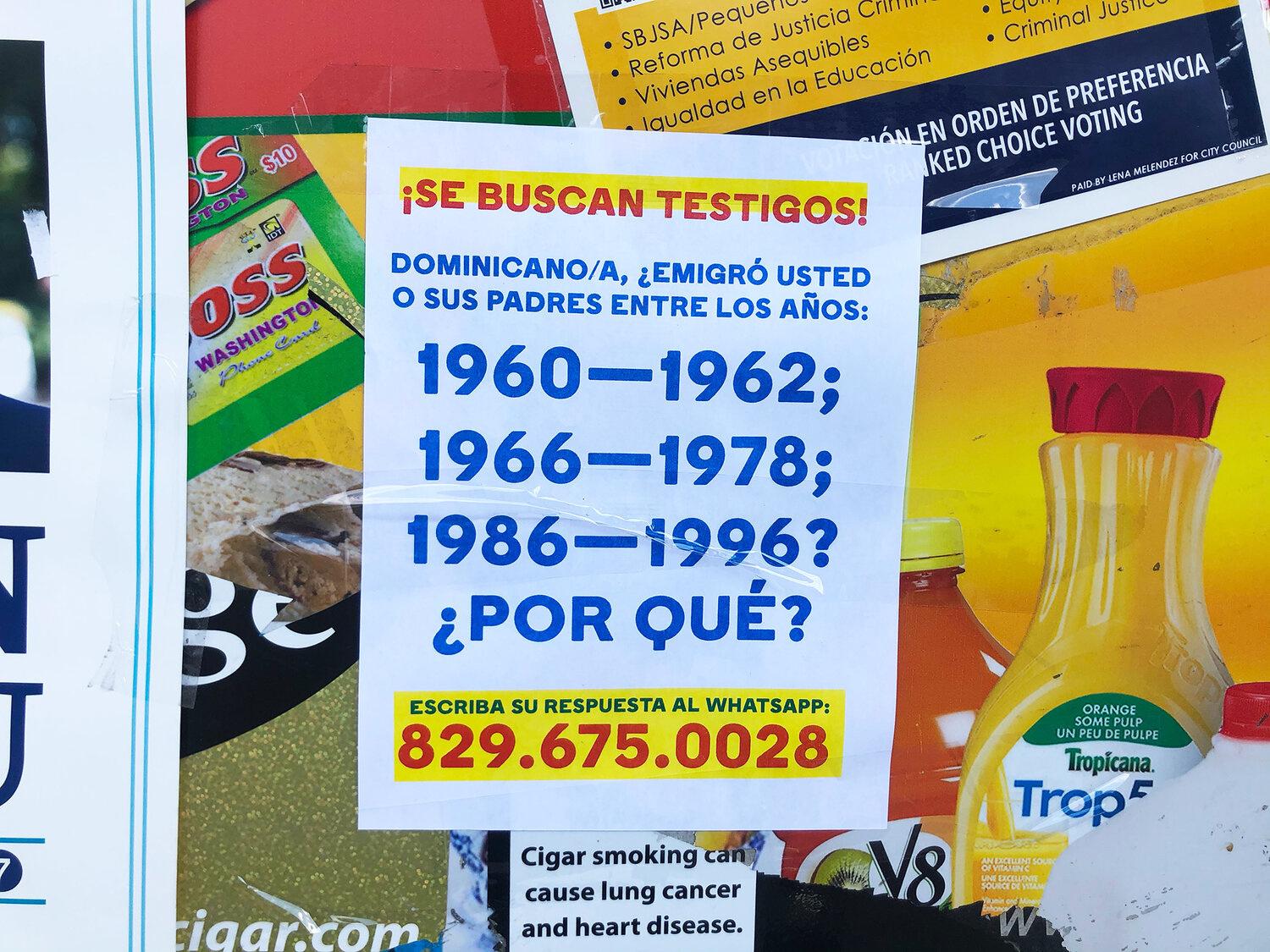

" ¡Se Buscan Testigos! [Looking for Witnesses!]" (2020-2021) by Lizania Cruz. Courtesy of the artist and CUE Art Foundation

It’s incredible to me that we’re at the point where, by law, Dominican’s were de-nationalized because of their Haitian descent. So the project is specifically about all that. It’s been super nice to see the show come together because I worked on a lot of the pieces in both Santo Domingo and here in New York City, so this is the first time I’ve seen the work together in conversation. A lot of my work happened in the public space, so this exhibition is the first time where I was able to not only do an action in the public space, but also think about all the documentation that happens within an action. The central piece to the exhibition is " ¡Se Buscan Testigos! [Looking for Witnesses!]" (2020-2021), where I did a campaign in both the Dominican Republic and New York City. I pasted signs throughout the places that asked very specific questions, such as, “What do you know about enslaved people in the Dominican Republic?” “Did you know that mangú was popularized in the Dominican Republic by enslaved Black people?” “What do you believe is the true story you learned in school about Christopher Columbus?” People could respond through WhatsApp via a phone number.

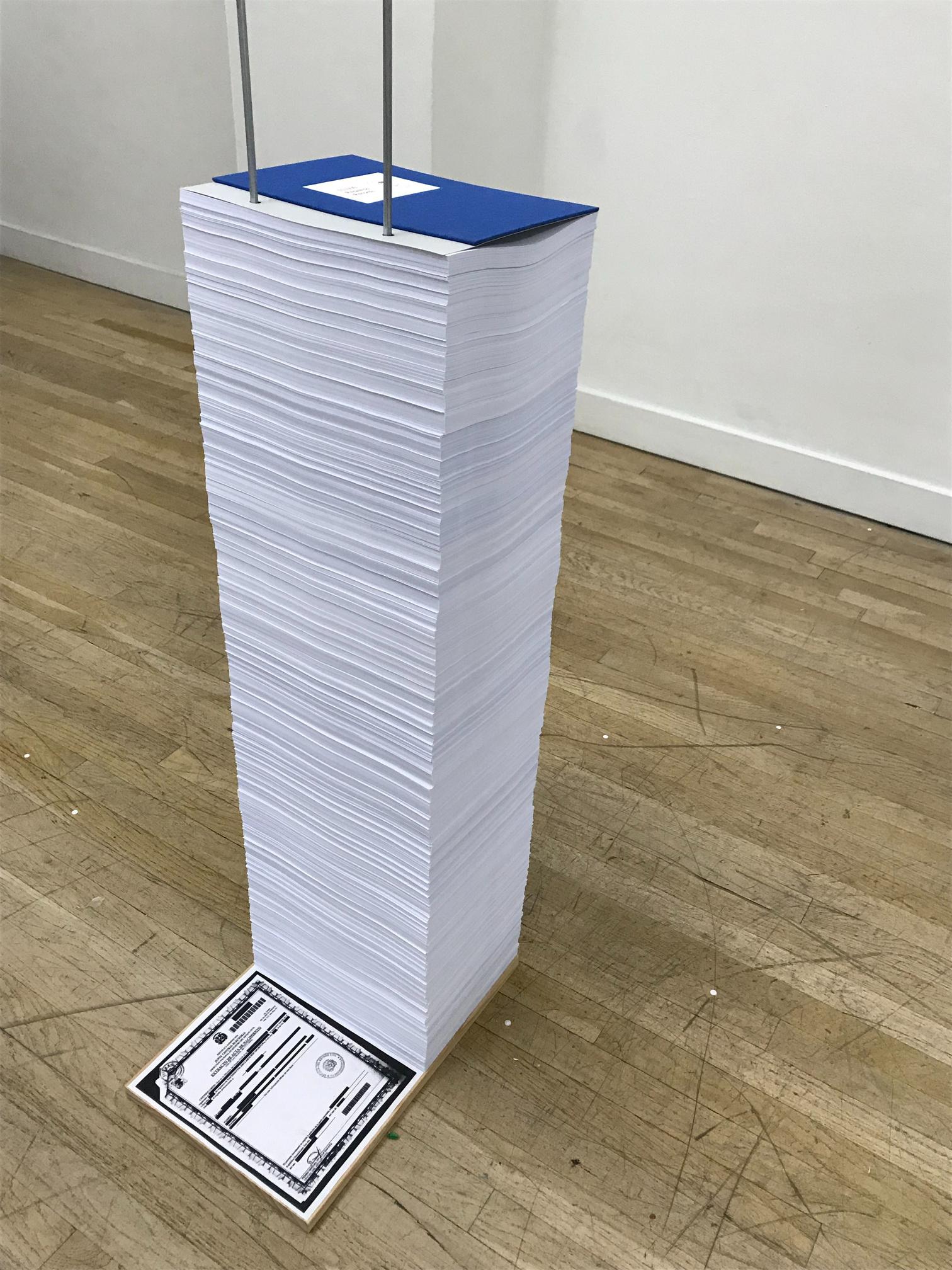

"The Plaintiffs Records" (2021) by Lizania Cruz. Courtesy of CUE Art Foundation I made a video that showed the signs all throughout the streets, and then I made an app with a creative technologist. [The exhibition is] multifaceted and what’s in the gallery is the posters, video of the documentation, and then visitors can scan a QR code and see all the testimonies through a phone app. There’s another [exhibited] piece that I’ve been working on for a year and am showing for the first time called “The Plaintiffs Records” (2021). It’s a series of books, each comprised of 10,000 pages, and is in reference to La Sentencia, the 2013 law that retroactively revoked the citizenship of Dominican’s of Haitian descent. There’s an edition of twenty books; each page represents a revoked birth certificate, and in some of the books there’s a bookmark with a QR code that allows visitors to read a story written by a person affected by La Sentencia. For this piece, I partnered with We Are All Dominican (WAAD) here in NYC and Reconoci.do in the Dominican Republican, two groups that organize folks that have been affected by La Sentencia.

GM: Did the past presidential administration’s xenophobic and racist laws against people from Latin American countries, especially immigrants, affect your practice?

LC: Yeah, of course! There was a sense of urgency that definitely pushed a lot of the things that I was thinking about and focusing on. One of my first public art projects, “Flowers for Immigration” (2016 – 2020), was actually a specific project around views on U.S. immigration rhetoric. I started the project when Trump was campaigning to be president. […] I honestly don’t think we’re done with the Trump era. What Trump did that was unfortunately so powerful was shift public opinion and public discourse – he gave space for people that were having feelings similar to his but were silent about it. These people are now empowered to do the things that they’re doing now. We’ll have to see what ultimately happens, because all the systems in place – the media, [U.S.] Congress – fuel Trump. We’ve turned a corner, but we’re still in the beginning stages.

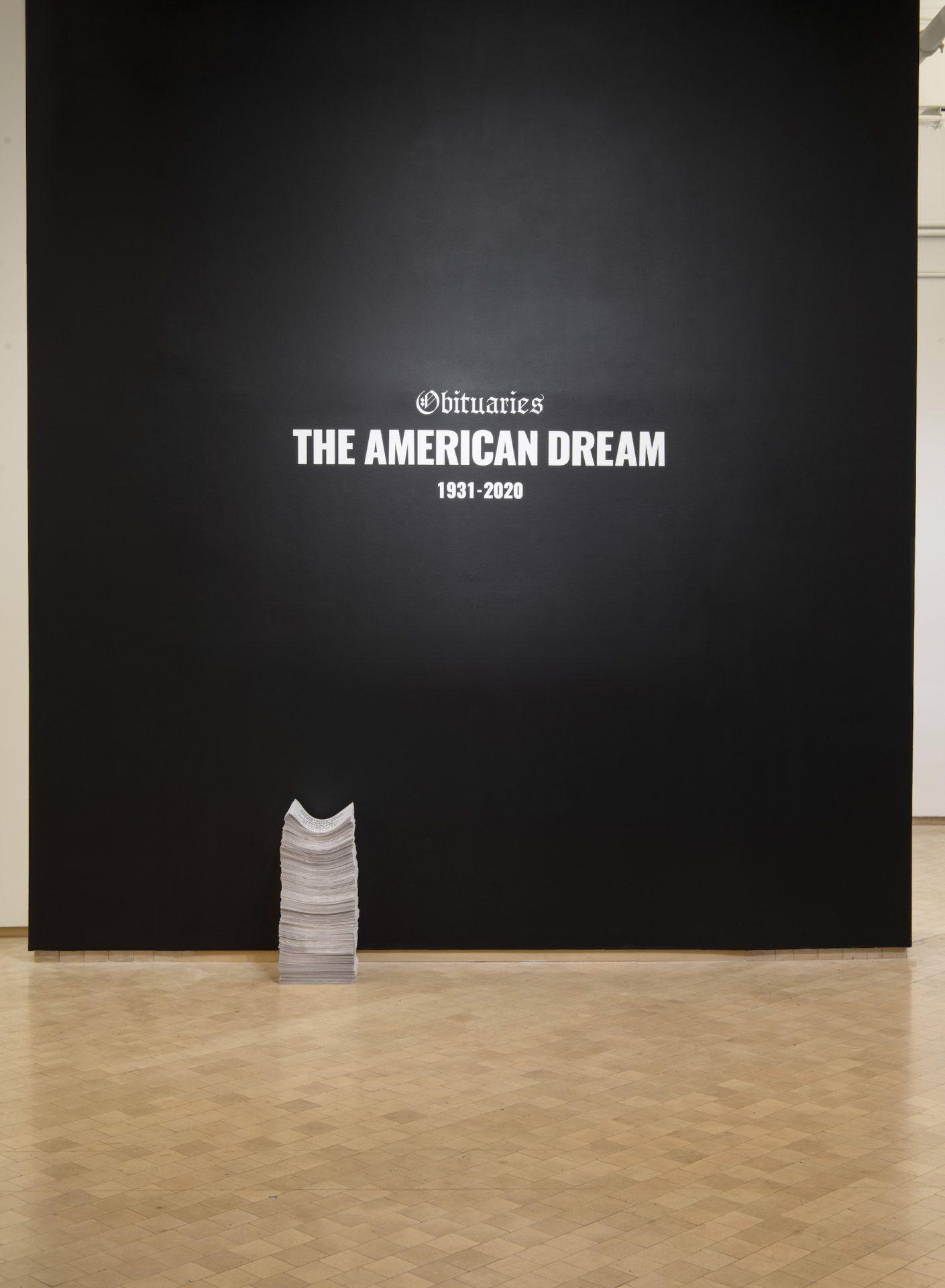

"The American Dream" (2021) by Lizania Cruz, as part of "Obituaries of the American Dream" . Installation view in ESTAMOS BIEN: LA TRIENAL 20/21 at el Museo del Barrio, March 13 - September 26, 2021. Courtesy of the artist