5 minute read

DAWN CHAN

from GIRLS 17

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. It took place in March 2023.

GM: What was your path to becoming a writer and editor?

Advertisement

DC: During undergrad, I'd done a fair amount of coursework in studio art. I had this notion that I would move to New York, set up a studio, make work, and start showing work. What I was making took up a lot of space The financial challenges of finding a big enough studio that was affordable only piled on to all the usual, more existential roadblocks that all artists starting out have to grapple with. For example, I’m talking about all the years an early-career artist has to stick to their vision, without an ounce of external validation. If you can believe in what you make for years, whether or not that belief ends up mirrored by others – that's a special trait. I think that those of us without it soon turn our efforts towards projects propelled forward by the motivational structures offered by institutions, communities, deadlines, and/or back-and-forth conversations. In my case, various friends working at magazines [who were] in need of content convinced me to try writing pieces for them here and there. And that work just somehow turned into more work.

GM: You are currently an editor for November, a non-profit magazine that features long-form interviews on art, architecture, media, and politics. How did this editorial project come to fruition, and what has been your experience working for it?

DC: All credit for November goes to founding editors Emmanuel Olunkwa and Lauren O'NeillButler. They had the vision to start this project in the midst of the pandemic, and then half a year later kindly brought me and others on board as the project was expanding in its scope. Lauren and I had worked side by side at Artforum.com for nearly a decade, and I wasn't going to miss an opportunity to collaborate with her again. Nowadays, I find myself constantly wanting to contribute more work to the project, but I am always short on time.

GM: You co-curated the exhibition Phantom Plane: Cyberpunk in the Year of the Future (2019-20) for the Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts in Hong Kong, which was co-presented by CCS Bard. What was your experience working on this exhibition, and what do you hope the audience took from it?

DC: That show was a very collaborative curatorial effort, with curators Lauren Cornell, Tobias Berger, and Xue Tan at the helm, and Jeppe Ugelvig contributing expert curatorial work and research. Working with that much museum space was a terrific opportunity, as was sitting at a table full of top-notch curatorial minds throwing top-notch ideas into the mix. Memorably, the show happened to coincide with a significant wave of pro-democracy protests taking place throughout Hong Kong. People did come to the opening of Phantom Plane, but the mood was somber. Many showed up dressed in the signature black outfits that the protesters had adopted. There were fires raging throughout the city later that night, traffic jams, clashes with police, tear-gas canisters in the streets. It all made certain artworks that we'd included resonate in a manner we hadn't expected at all. As it happened, the ways that cyberpunk had once laid out various aesthetic and speculative approaches for the envisioning of broader societal futures suddenly felt eerily adjacent to the ways that young people in Hong Kong were testing out their own ability to chart a path forward on their own terms. You couldn't help but be reminded that all art is encountered through the lens of the moment, which might be one of the chaotic, alchemical aspects of exhibiting art that curators have no choice but to embrace.

Shinro Ohtake, MON CHERI: A Self-Portrait as a Scrapped Shed (2012), Tai Kwun Contemporary. Courtesy of Take Ninagawa, Tokyo Copyright: Shinro Ohtake

Exhibition view of Phantom Plane: Cyberpunk in the Year of the Future (2019), Tai Kwun Contemporary. (L-R): Tetsuya Ishida, Aria Dean, Nurrachmat Widyasena

Photo: Kwan Sheung Chi.

GM: You have written essays about the concept of Asian futurism for numerous publications – why is this topic important to you?

DC: Asian futurism is a topic I've thought quite a bit about ever since the visionary writer and critic Ryan Lee Wong, author of Which Side Are You On (2022), introduced me to the notion years ago in a conversation at a Chinatown bar. We'd both turned up for a group viewing of Fresh Off The Boat, which at the time was the first primetime U S TV show in decades to feature a cast of Asian and Asian American actors. Soon after that, I wrote about Asian futurism in 2016 for Artforum. Around that time, discussions around the notion of "representation" had taken on a renewed intensity. But along with those discussions, there was the ever-present realization that checking boxes and meeting numerical quotas would always be a flat, simplistic response to a complicated reality To me, Asian futurism seemed like one way to move from quantitative questions to qualitative ones: what does it mean that the notion of a futuristic Asian city, whether utopian or dystopian, has taken hold in global imaginations? How does that notion in turn affect the sorts of artwork by Asian diasporic artists that are selected and amplified in exhibition spaces? How does Asian futurism affect the reception and understanding of such work worldwide? My first writings [about] the subject were very much done from my position and perspective as an American, but [there was] the extent to which the discussion expanded globally. Hearing from the U.K. professor who added it to their syllabus, or the Hong Kong based artist sharing some handwritten translations of it on social media, was both really rewarding and eye-opening

GM: How do you think society should steer conversations about diversity and safety beyond the #StopAsianHate Movement?

DC: The #StopAsianHate movement was clearly an urgent response to a moment when we saw people be racialized as Asian in public spaces and consequently designated targets of unspeakable violence. Beyond that urgency, one wonders if and how such broad public conversations can now move in a direction of nuance. (Continued)

These conversations can only grow more productive when we can start to acknowledge the permeable, unstable aspects of race that hashtags simply cannot capture. Start with the very reductionistic fact that the term Asian, as it is used in America, encompasses both various South Asian and East Asian communities, even when these communities end up racialized in ways that have historically subjected them to completely different patterns of violence. I think of the slurs hurled at an Indian American colleague post 9/11, as compared to the slurs encountered on the street by a Chinese-American colleague during the pandemic. The inadequacies of even the term "Asian" – the very term that needed to stay simple, in order for hashtags to go viral – underscore the ways that conversations, and the vocabularies that underpin these conversations, need to keep evolving toward nuance

GM: What are you currently working on in your practice?

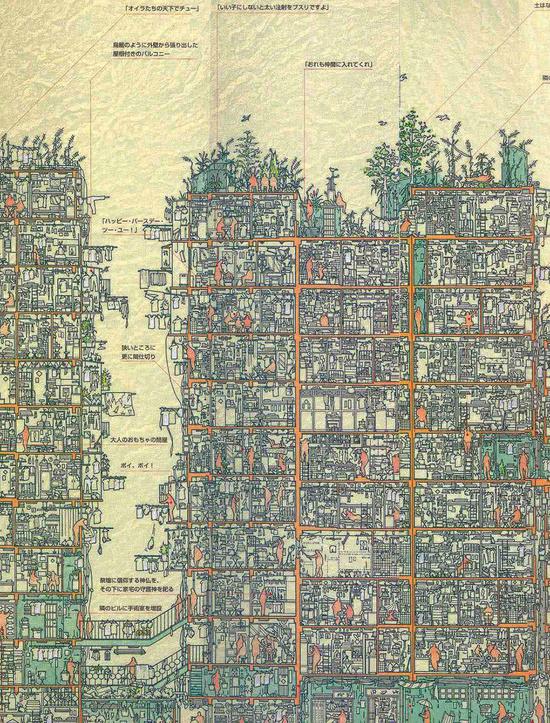

DC: This spring, photographer Tommy Kha staged a two-room show at Baxter Street Camera Club, and it was a privilege to be able to contribute as a curator. My intention is to write primarily and curate very occasionally, but I couldn’t pass up the chance to work with Kha, who is really doing fresh things with photography. Meanwhile, colleagues at November convinced me to finally finish and publish a piece about the contemporary art resonances of Kowloon Walled City, [which is] an iconic, infamously unplanned building complex in Hong Kong that functioned outside of government rule And for now, I'm trying to keep up a balance between writing and teaching, but have also started working on a piece that tries to interweave many different things: verb tenses, counterfactual worlds, in-between worlds, urban futurism, and constructions of self, set in Hong Kong. We'll see!