86 minute read

Seeing the big picture Sludge management solutions for water and wastewater works

from IMIESA March 2021

by 3S Media

Committed to providing value-engineered solutions, Hall Longmore’s decision to introduce dual-layer (DL) fusion-bonded epoxy (FBE) corrosion protection coating systems will set a new benchmark for the South African market. The primary objective, says managing director Kenny van Rooyen, is to ensure legacy benefits for local infrastructure.

Hall Longmore ventures into dual-layer FBE coatings

Advertisement

To ensure that carbon steel pipes meet their expected lifespan, some form of coating system is always required – often in conjunction with cathodic protection – to combat corrosion. Allied to this are primary considerations like impact, as well as load and soil stresses, which all influence the internal and/or external lining system chosen for each specific application. Examples include the oil and gas sector, and the water and wastewater segment.

Alongside pipelaying, these coatings also need to be able to withstand and maintain their integrity for rigorous tasks like horizontal directional drilling, pipe jacking and allied trenchless technology techniques. Here, these coatings perform optimally in terms of high mechanical impact resistance, providing exceptional protection properties that exceed what was previously available in these hot, moist environments.

“Hall Longmore, as a leading steel pipe manufacturer since 1924, has always fielded a range of coating systems. However, we’re confident that one of our most enduring solutions to date comes in the form of AkzoNobel’s

Kenny van Rooyen, managing director, Hall Longmore, discusses the benefits of ARO and MRO coatings during a factory open day in March 2021

Second layer being applied

proprietary DL FBE powder coatings series. FBE is a premier corrosion resistance coating adopted globally,” says Van Rooyen.

Adding back

“As a South African company, our investments and innovations play a crucial role in revitalising our country’s industrial base, especially via local content production. This has a direct benefit for all the industries that we supply, and we clearly understand that their growth is integral to ours. In addition to this, we understand the need to launch products that can extend the life of our pipeline assets. Up front, that hinges on choosing the best technologies,” Van Rooyen continues.

Hall Longmore’s target market for FBE coated pipes is for 100 mm to 600 mm nominal bore applications in the water reticulation sector.

Dual-layer benefits

There’s a two-pronged solution, which is application dependent, namely an abrasionresistant overcoat (ARO) and a moisture-resistant overcoat (MRO). Both are intended to provide the final protection layer within the DL powder-coating

Conducting a coating thickness test

A view inside the spray chamber

application process. The base coat is always the corrosion protection layer. Then follows the secondary ARO or MRO coating. ARO forms a tough outer layer that is resistant to gouging, impact, abrasion and penetration.

DL FBE systems that have ARO or MRO as a second outer layer have an elevated glass transition temperature up to 180°C, which underscores their durability. An improved moisture barrier also translates into less ‘steam jacking’ in hot systems. This is because these coatings absorb destructive energy in rough environments, minimising coating damage. These coatings also exhibit excellent cathodic disbondment resistance and superior performance in long-term roles that include wet conditions.

Application process

At Hall Longmore’s factory in Wadeville, Gauteng, there are two powder application booths working in tandem. Hall Longmore has invested in one of the few dual box fusion bonded application plants in Africa. This is a high-speed line, incorporating an extensive degree of automation. The advantage for customers is that this technology achieves higher efficiencies that result in more competitive pricing for end users. As per industry standards, typical pipe lengths are either 9 m, 12 m or 18 m. During the coating process, the pipe is charged negatively and the powder positively, so there’s an automatic attraction to each other. This creates an even coat. During this manufacturing process, the powder coating is air sprayed while the pipe is polarised. The pipe is heated to a specified temperature. The first layer is then applied, followed within 10 to 20 seconds by the second layer.

As an indication of the speed of production, around 1.5 km of DL FBE coated pipe can be produced in a single shift configuration daily, depending on the pipe bore specification.

Field joints can be coated with a compatible epoxy system to maintain the coating integrity of the entire pipeline.

Meeting the holiday test

These coatings comfortably meet holiday test specifications. This non-destructive test method essentially verifies that the pipe is homogeneously coated, correctly sealed, and that there’s no opportunity for air or water ingress. In this respect, a holiday is defined as a hole or void in the coating film, which would expose the pipe to corrosion.

“The point to emphasise here is that the DL FBE coating then adds a further level of quality assurance,” Van Rooyen continues. “Thanks to DL FBE, the direct current voltage gradient is also significantly reduced during pipe handling and installation.”

Higher intrinsic dielectric strength results in less moisture uptake and fewer issues with wet/ dry sponge holiday detection – i.e. fewer false positives. That has key benefits where pipelines are laid in vlei and marshy areas using the MRO. The MRO actively repels water.

“To ensure carbon steel pipe integrity, cathodic disbondment resistance testing is another important tool. The test verifies the ease with which corrosion could under-creep any coating system. In the case of DL FBE, this test proves that these coatings have exceptional resistance against cathodic disbondment in this scenario,” he adds.

Final production stage

Robust pipeline installation, simplified backfilling

DL FBE coating systems promote long lifespans, and that’s not just thanks to factory quality assurance. Downstream installation was always top of mind, which is where ARO scores major points in terms of transport logistics and onsite operations.

ARO coatings are designed for tough handling, ensuring that there’s minimal or no damage in the process. The upside for contractors, especially SMMEs without access to formal pipelaying machines, is that more general earthmoving plant, like excavators, can be used.

Another important aspect to consider is backfilling. Traditionally, fill material must be carefully screened to remove sharper and larger rocks; however, the DL FBE system provides more leeway in terms of improved damage tolerance, since the coating is effectively as strong as steel despite its approximately 1 mm thickness. This middle ground helps to lower earthmoving costs and accelerate the overall construction programme.

Global best practice, local excellence

“Over the years, Hall Longmore has developed a detailed understanding of the needs of consulting engineers and pipeline contractors. This has constantly influenced and shaped our research and development programmes,” adds Van Rooyen.

“We fully appreciate the critical contribution that infrastructure makes in building a vibrant economy where everyone benefits. The local launch of new technologies like DL FBE is our latest contribution to ensuring that South Africa remains in step with what’s happening in the rest of the world,” Van Rooyen concludes.

Established in 1924

Infrastructure procurement: A minefield for municipal engineers

Few activities of built environment professionals in the public sector are as disconcerting as the appointment of engineering consultants and contractors. The process is a minefield of innumerable, inconsistent, inhibitive and contradictory legislative provisions that ends with the built environment official being answerable for decisions mainly made by finance and legal professionals. By Gundo Maswime*

Gundo Maswime

Infrastructure procurement in South Africa, by design or coincidence, is about financial prudence and administrative compliance, and less about the successful delivery of public infrastructure. This is mainly because legislation was conceived by politicians, drafted by non-engineering bureaucrats and presided over by accountants and auditors, with nominal engineering input.

Even at institutional level, infrastructure procurement is presided over by the chief financial officer. There are many clauses in the various pieces of legislation governing public infrastructure procurement that have no identifiable benefits nor beneficiaries along the infrastructure value chain. These clauses are painstakingly followed in pursuit of a clean audit outcome at the expense of good project outcomes.

The pre-1994 procurement system in South Africa had an obvious bias towards large and established construction and consulting firms, which made it very difficult for newly established businesses to enter the sector.

Government procurement was granted constitutional status in 1996. A year later, the 1997 infrastructure sectoral transformation Green Paper was gazetted as a means of addressing past discriminatory policies and practices. Saki Macozoma, based on his experience as managing director of Transnet, conceded that the new framework was too preoccupied with getting the politics right at the expense of government efficiency.

If by “the politics” Macozoma meant the transformation of the construction sector, it is debatable if indeed “the politics” came to be right. If they really were, the stoppages of construction projects and the frustration at the slow pace of transformation of the industry would not be as commonplace as is the case today.

Procurement and engineering interlinked

Procurement for public infrastructure is a core function of an engineer’s repertoire, which should be inseparable from engineering practice. There is a direct link between design philosophies (such as limit state design) and contract price (as a determinant of risk). This link is hidden in the concept of safety factors and the inherent uncertainty in some aspects of engineering science.

The more obvious one is geotechnical engineering. The engineer has a valuable insight about where the real risk in design and construction lies and this expert knowledge is critical in deciding which bidder has the most appropriate set of skills and experience, and which price can envelope the risk that the uncertainty presents.

Incompetent bidders and legislative hurdles

In the public sector today, supply chain officials without engineering credentials

participate in allocating points for functionality and their scores weigh enough to tip the scales in favour of an incompetent bidder. When this bidder fails to deliver the project, the municipal engineer will be the one reporting to various structures and accounting for the lack of progress.

The engineer, in daily practice, is confronted by the need to comply with not less than 11 pieces of legislation that are enforced by the Auditor-General. Geo Quinot, a law professor at Stellenbosch University, places the number at just over 80 indirect legislations affecting infrastructure procurement, of which 22 have direct applicability to the process. The Auditor-General inspects whether these are complied with.

The audit process is very unforgiving to engineering logic. Many engineers in the public sector know that it is safer to let the project fail than to skip any of the stipulated procurement procedures. These rules can be used on a whim to frustrate, intimidate and even dismiss engineers in local government.

The absence of differentiation between infrastructure procurement and the procurement of any other goods and services is a statutory negation of the uniqueness of infrastructure procurement. Infrastructure procurement is unique and distinct in the sense that it concerns the procurement of goods that are not delivered packaged and finished like furniture or computers. The risk in infrastructure procurement increases very sharply as the bid price drops. Our procurement philosophy puts a premium on the very lowest price despite its risk amplification. This is a very costly contradiction.

Regulation 28

Public officials appeared to rationally drift away from minimum price using the creative dismissal of low-price bidders. This prompted National Treasury to issue Regulation 28 of the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act (No. 5 of 2000) to compel public servants to appoint the bidder with the highest points. Regulation 28 was issued after a number of legal cases that the state lost to aggrieved bidders that had the more points than the appointed bidder.

Typically, the highest points go to the lowest-price bidder because price accounts for either 90% or 80% of the points, depending on the estimated overall contract price. The appropriate reaction should have been to revise legislation to ensure that the fallacy of equating the lowest price to the best price is circumvented. The courts merely interpret legislation as it is and make a ruling.

The Draft Public Procurement Bill has been widely circulated for comment in a process so delayed that the lack of a sense of urgency is obvious. The Supreme Court of Appeal made a ruling that rendered sections of the 2017 Preferential Procurement Regulations unlawful. These are regulations pertaining to subcontracting and the prequalification criteria associated with the Preferential Procurement Framework Act.

These legislative interventions do not address the bigger problems with infrastructure procurement. That is why both Construction Alliance South Africa and the South African Forum of Civil Engineering Contractors never mentioned them in their petitions to the Minister of Finance just before the budget speech, though they wrote broadly about procurement. Fana Marutla, president of SAICE, unpacked how procurement attracts corruption when it is not based on sound engineering judgement (Civil Engineering, January/February 2020). The draft bill on public sector procurement does not show any significant change in direction from a rules-based approach to a project-outcome-based approach driven by product experts.

Conclusions

There is a need for a comprehensive infrastructure procurement manual that factors in the uniqueness of infrastructure procurement, and shifts from the boxticking approach into strategy and risk management by allowing engineers to apply their technical knowledge in deciding how best to procure the services of built environment consultants and contractors.

This manual should correct or nullify some clauses that apply to general procurement. It will also add new clauses to cover the gaps that exist pertaining to such scenarios as strip-and-quote, as-andwhen contracts, and procurement for new innovative methods and technologies in the built environment.

Until then, funds will be wasted while avoiding wasteful expenditure, and projects will be abandoned to avoid unauthorised expenditure. The construction fraternity must patiently lobby relevant authorities to bring comprehensive reforms to this important aspect in the delivery of public infrastructure.

*Gundo Maswime is a lecturer at the University of Cape Town and researcher in public infrastructure.

Build smarter with digitalisation

The construction industry is tool-based – there are different tools for different jobs. This creates silos of information and work that are unstructured and uncollated. Andrew Skudder, CEO of RIB CCS, talks about a solution-based collaborative platform and one central database. This digital platform approach empowers the sector to use the increasingly important asset of data to make better decisions and ensure projects are delivered more efficiently, on time and within budget.

Andrew Skudder, CEO of RIB CCS

What value does RIB CCS bring to the construction sector?

AS Our mission as a business is to digitally transform the construction and engineering industry into a more sustainable, advanced industry. Digital transformation increases collaboration, (and the associated infrastructure) is key for people’s quality of life and prosperity.

productivity and efficiency, which results in greater profitability and sustainability for companies. By assisting construction companies to build more with fewer resources, we then benefit society. Those saved resources can be directed to other projects. An effective built environment

What is MTWO Complete Construction Cloud?

This is a cloud platform that provides end-to-end management across the

1982

WHO IS RIB CCS? A STORY OF TWO SOUTH AFRICAN PETERS AND A project manager called Peter Reynolds, A GERMAN SOFTWARE COMPANY frustrated with repeatedly generating estimates on a piece of 2000 – 2008 2020

paper, decided to digitalise his estimating activity. He developed the Candy estimating CCS and BuildSmart Schneider Electric buys software solution and established CCS. merge and expand their shares into RIB Software.

From there, Peter further developed footprint into India and

Candy into a project planning and Australia. control solution and CCS

offices opened in 2000

Portugal and

the UK. Peter Cheney 2019

started BuildSmart, where he developed a financial management solution (including procurement, payroll and accounting) specifically for the construction industry. It is introduced into other Southern African neighbouring countries. Candy expands into CCS joins RIB Software – a German multinational construction software company that has been operating since 1951, leading to the rebranding of CCS as RIB CCS in 2020. Dubai and New Zealand.

design, build and operate phases of the construction life cycle. It is a partnership between RIB and Microsoft. RIB hosts iTWO 4.0 software with 5D BIM (fivedimensional building information modelling) capabilities on the Microsoft Azure platform. Furthermore, Microsoft Azure offers exceptional cybersecurity and other capabilities like AI (artificial intelligence) and HoloLens that are layered on top of the software – creating additional value.

A critical part of MTWO 5D BIM is the integration of 3D models with cost and schedule information to create a 5D model or digital twin of a project. 3D models can demonstrate how changes to materials, layouts, square meterage and other design elements affect the appearance of a facility, as well as the cost and schedule of construction. With a 3D model, costing and schedule, a client can simulate a project before construction has started and then value engineer and optimise that project. A 3D model is a visual representation of the project and if you add a functionality like HoloLens, you can even do a virtual walkthrough. The AI functionalities on MTWO are chatbots, voice assistance and machine learning.

The beauty of MTWO is that it has an open architecture with open APIs, and this allows it to interface with other tools within the construction value chain. For example, many of our clients are users of Microsoft Project or Primavera, as well as SAP or Oracle, which can integrate into our platform. This allows for everyone to work on one single platform and database, which means that everyone collaborates seamlessly.

As an internet-based solution, MTWO needs decent bandwidth to operate, but there are offline functionalities, particularly relating to work done on a site.

RIB CCS is bringing this product to the Southern Africa, UK and Middle East regions. We are also working on further enhancing the platform with new functionality and modifications that may improve or better reflect the way that owners, developers and contractors operate within these markets.

MTWO Complete Construction Cloud

BIM Model Management Quantity Takeoff Estimating

Is MTWO a major departure from ERP-type (enterprise resource planning) systems industry has known in the past?

I would like to describe MTWO as the technical ERP in the construction industry. F a c i l i ty Building Li fecycle M an g e m en t O P ERATE a PLAN S i m u l a t io n Schedulin g Site Management We depart from traditional ERPs because we are industry specific – the engineering and construction industry is projectbased and operates differently to other sectors. Traditional ERPs focus on multiple Quality &Safety Procurement BUILD Project Management & Bid Tender verticals while we focus on one – therefore, the depth of functionality, expertise and support is unique, which is why roughly 80% of RIB CCS staff have previously worked People think that digital transformation is at construction companies. Also, unlike expensive and time consuming. other ERPs, MTWO deals with the entire MTWO can be implemented in months, not value chain – from bidding for the project to years. But this often depends on a client’s its operation. implementation approach – some clients choose to start with estimating, and then a Can MTWO be used in the few months later move on to planning and, public sector? a few months later, procurement. Buying a Absolutely – government entities must best-of-breed solution that is purposely built make sure that infrastructure is built in a for your specific industry can be expensive, responsible way (on budget, on time, quality but there is limited customisation and no and according to environmental, social and development. We will be developing an outgovernance rules). MTWO gives government of-the-box solution, where MTWO can be entities transparency to see if a project is on preconfigured and precustomised, which budget and time, and provides transparency lowers the barriers to entry. to stakeholders (like National Treasury) with But if there is poor planning with regard to procurement. no digital roadmaps and unclear

This transparency will give greater objectives, digital transformation can be confidence to the funders of these projects, expensive and time consuming. Change as they would know that the project has management, led from the top, is key to a been optimised and value engineered before successful transformation. construction and is well managed and “The construction industry has taken the controlled during construction. longest to embrace digital technology. But

The Deutsche Bahn (German rail operator) we are now at an interesting stage within and Autobahn (German equivalent of Sanral) the built environment where we have uses MTWO because they see the value solutions like MTWO that are available to in the transparency, collaboration and the us. This is a unique opportunity for owners, ability to coordinate multiple projects. developers and contractors to embrace this technology and create a more collaborative, What are common misconceptions transparent, efficient, and productive about digitalisation? industry,” concludes Skudder.

ribccs.com

FIDIC versus NEC

When it comes to contract disputes, the FIDIC and New Engineering Contract (NEC) suites both have their merits, but which is the most practical and costeffective?

By Zizodwa Zizo Mkhize

The Global Construction Disputes Report (2016) definition outlines a situation where two parties typically differ in the assertion of a contractual right, resulting in a decision being given under the contract, which in turn can become a formal dispute. The important point is to find a middle ground that achieves favourable resolution.

In this respect, the construction contract adjudication process is a form of dispute resolution that meets a need for a rapid, inexpensive mechanism where agreedon outcomes can be implemented immediately. The aim of my study was to evaluate if the clauses of the construction contract adjudication method for FIDIC (International Federation of Consulting Engineers) were similar for NEC infrastructure construction projects.

Dispute resolution methods in South Africa

Table 1 shows the four standard forms of construction contracts used in South Africa, as noted by the Construction Industry Development Board and the applicable dispute management clauses.

Two prominent methods used for resolving disputes include the dispute adjudication board (or DAB) and statutory adjudication. The DAB is utilised under FIDIC contracts, while adjudication is utilised within the NEC, JBCC (Joint Building Contracts Committee) and GCC (General Conditions of Contracts) framework.

FIDIC versus NEC adjudication

FIDIC contracts make provision for arbitration as the final dispute resolution method, while the NEC prescribes litigation as the final method. In addition, FIDIC contains a provision for adjudication, while NEC renders adjudication FIGURE 1 Breakdown of sample contract types compulsory, and has a separate 1 adjudicator’s contract. 6 In both the DAB and adjudicator’s case, decisions are final and binding. That’s 14 Fidic Red if no notice of dissatisfaction Fidic Yellow is raised by either party within 12 NEC ECC NEC TSC 28 days after the decision. Several studies have confirmed that there is no single source of disputes, since various interconnected factors

Zizodwa Zizo Mkhize, Pr CPM (SACPCMP), senior manager: Contracts Management at Eskom

combine to form them. However, where delays do occur, this has adverse consequences on project objectives in terms of time, cost and quality.

According to the Global Construction Disputes Report, the most important activities in helping to avoid a dispute are proper contract administration, fair and appropriate risk and balances in the contract, and accurate contract documents.

My research focused on the principal or main contractors only, as they signed a direct contract with one organisation. The research study was mainly qualitative in nature because of the questions to be answered. A total of 33 awarded adjudication cases were analysed, of which 18 were FIDIC and 15 NEC contracts. The FIDIC analysis referenced high-value and complex projects, whereas the NEC was used for non-complex and low-value projects.

A comparison between the FIDIC suite of contracts and the NEC suite is very complex because there are many contracts in each family. Therefore, it was never clause-toclause. The scope of this study was limited to the concluded adjudication cases for the construction infrastructure contracts only.

The case study was based on the type of contracts as per Figure 1.

Key findings

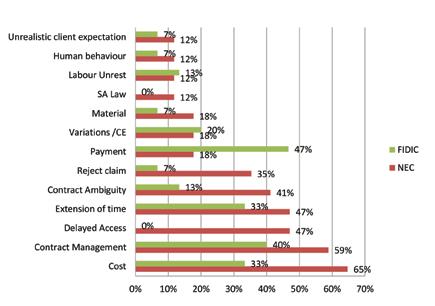

There were 21 main causes and driving forces identified in the FIDIC cases and a total of 16 were derived from the NEC cases (see Table 2).

Figure 2 in turn represents a comparison of the top 10 FIDIC and NEC causes of adjudications.

Conclusions and recommendations

In comparing the FIDIC and NEC main causes of contract disputes, the summarised conclusion is as follows: • There are comparable causes of disputes among the two contracts even though they vary in terms of ranking on each contract. • Cost and contract management ranked as the highest source or the cause of the disputes. • Design, poor planning and risk management ranked as the lowest source or cause of the disputes. • The adjudications or DABs disputes on the interpretation of the contract terms and conditions of the contract should have been avoided. The key strategic factor in dispute management is the appropriate knowledge in managing the construction disputes. The formal training of project managers, engineers and contract managers on contract dispute avoidance and management is therefore recommended. In addition, the lesson learnt on the awarded adjudication cases must be published within organisations to ensure common understanding and aligned focus on the primary mandate – namely, optimal infrastructure delivery.

TABLE 1 Dispute-resolution methods endorsed in the standard forms

Contract type Adjudication/dispute adjudication board Arbitration

FIDIC Clause 20.2 Clause 20.6 NEC Clause W1.1 Clause W1.1 GCC Clause 10 GCC 2019 Guidelines Clause 10 GCC 2019 Guidelines

JBB

Clause 30.3 Clause 30.5, Clause 30.7

FIGURE 2 Comparison of the top 10 FIDIC and NEC causes of adjudications

TABLE 2 Main causes and driving forces of disputes in FIDIC and NEC cases

Sources of disputes from the cases Number of occurrences in NEC Number of occurrences in FIDIC Total numbers of occurrences Ranking

Communication Contract ambiguity Contract management Cost Delayed access Design/scope Dispute settlements Extension of time Human behaviour Labour unrest Material 5 1 6 7 2 7 9 4 6 10 16 1 5 11 16 1 0 8 8 5 0 1 1 11 1 1 2 10 5 8 13 2 1 2 3 9 2 2 4 8 1 3 4 8

Payment Performance and experience Poor planning Quality Reject claim Risk management SA law Termination Unrealistic client expectation Variations/CE Weather conditions 7 3 10 3 3 1 4 8 0 1 1 11 1 1 2 10 1 6 7 6 0 1 1 11 0 2 2 10 2 0 2 10 1 2 3 9 3 3 6 7 0 1 1 11

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author would like to thank the organisations for allowing the study and giving access to the adjudication cases. Further acknowledgement goes to Professor Dhiren Allopi from Durban University of Technology for his assistance and guidance.

This article is an edited version of the original paper. Full references are available from the author.

Public buildings

need expert maintenance plans

Clearing government building maintenance backlogs requires a working partnership between the private and public sector, with a specific focus on employing the skills of facilities management (FM) experts. Lydia Hendricks, business development director at FM Solutions, says this is the best way to help curb wasteful expenditure.

The South African government spent R5 billion on renting private buildings during the financial year ending March 2020, according to a recent statement by Minister of Public Works and Infrastructure Patricia de Lille. This has highlighted how failing infrastructure forces government departments and institutions to procure reliable and compliant office space from the private sector to the point of paying premium rates.

“The South African government has a portfolio of more than 93 000 buildings. Many of them hold great historical value and should be more than adequate to accommodate the public servants and departments they were meant to house, provided they were in a safe and habitable state. The fact that state departments needed to rent private buildings from landlords shows the urgent need for collaboration between the public and private sector, especially when it comes to managing valuable property assets,” says Hendricks.

Hendricks explains that, traditionally, government’s approach to property management has been to steer funds towards upgrading derelict buildings at huge capital costs instead of directing enough funds toward preserving their assets.

A reactive approach

“Historically, the government was steadfast in managing their buildings themselves and applied a reactive approach. This meant that massive financial injections were needed to restore the structures to their former glory. In many cases, the renovation and repair projects were done long after disgruntled and frustrated departments had moved out to find more suitable and safe accommodation. Because some buildings were left vacant, the burden on the state’s coffers only became heavier,” Hendricks reports.

She also explains that the absence of a robust FM plan, backed by a financial plan to preserve and extend the life cycle of these assets, meant that the negative cycle continued unabated for many years.

Lack of data

“Owing to the size and complexity of managing buildings and assets at this scale, decisionmakers at the top had no real data to know whether the state property assets were being effectively managed for many years. The Government Immovable Asset Management Act (No. 19 of 2007) sought to address this, but the wheels churned too slowly. When conducting our conditions audits, we still find that some government departments have no clear understanding of what their asset portfolios need to include, or the true state of their assets,” she reveals.

Hendricks advocates that fixing this problem starts with government admitting that it needs help and accepting guidance from professional FM experts who will be able to give them a thorough understanding of the built-in systems, as well as develop a detailed recovery and restoration plan.

“A robust and measurable FM support plan will not only ensure building compliance, but also the sustainability and reliability of all government’s operating systems. This includes the technology and the human resources that drive and manage it. FM plays a huge role in aligning service delivery and infrastructure. Because valuable assets are preserved and maintained, service interruption is kept to a minimum, and strategic objectives of the organisation are met,” she says.

Informed procurement decisions

There are numerous ways in which partnerships between the public sector and private FM service providers will not only address inefficiencies but will also result in immediate savings thanks to informed procurement decisions. Moreover, it can create more jobs in communities through the development of SMME initiatives, the appointment of carefully selected local service providers, and the in-house training of staff to run facilities more effectively.

“I believe the current Covid-19 pandemic has brought us to the point of no return. Local and provincial governments are now willing to concede that they need help in curbing ongoing fruitless expenditure, unlocking savings, and turning ailing administrations around,” Hendricks explains.

“Local government entities are facing serious financial deficits ahead of the start of the new financial year. Funds are required to continue operations, maintain buildings, and drive the post-lockdown recovery of local economies and town centres. The only way they can do this is to join hands with the FM industry and form public-private partnerships,” she implores.

Hendricks says the challenges facing government today stretch far beyond delivering frontline services, corporate strategy and income generation. More than ever before, government needs to be resilient. This requires long-term thinking and deliberately improving capabilities in order to ensure it can effectively deal with future challenges.

“During last year’s State of the Nation Address, President Cyril Ramaphosa made it clear that his administration needed help to get the economy back on track. The good news is that it is not yet too late to turn the country around, but it is impossible for government to do it alone. Going about business the same way will only continue to cost the taxpayer billions and put thousands of jobs at stake,” she adds.

“We therefore urge our country’s leaders to tap into the wealth of specialist knowledge housed in the private sector to develop workable, holistic and achievable plans that will provide the right solutions for government departments and the communities they serve,” Hendricks concludes.

Lydia Hendricks, business development director, FM Solutions

Eliminating technical barriers to trade

The SABS has been designated as the WTO TBT Enquiry The South African Point Office, with the goal of consolidating the technical knowledge of government experts regarding the preparation, Bureau of Standards (SABS), analysis and submission of technical regulations in collaboration with the World

Trade Organization (WTO), recently an obligation to drive resolving all enquiries that arise from both hosted a seminar on the WTO transparency by local and international stakeholders that Technical Barriers to making available all experience barriers to trade. Hundreds of the documentation alerts and enquiries are dealt with on a Trade (TBT) Agreement's related to the monthly basis and these queries range from

Transparency Framework. This enablement of trade reviewing regulations to managing queries on forms part of a vital initiative within borders and to local trade conditions and any requests for be available to answer country contacts regarding equipment and that sets out the rules enquiries from member infrastructure,” Scholtz explains. of engagement. states,” Scholtz continues. South Africa, as one of e-Tools the 164 countries that are a During the seminar, national regulators were signatory to the WTO TBT Agreement, reminded of the key provisions, principles The seminar discussed national regulatory organisations’ responsibilities in the drafting of policies, has a responsibility to ensure that all technical regulations, standards and conformity assessment procedures are nondiscriminatory and do not create unnecessary obstructions to trade. The SABS has been designated as the WTO and e-tools available to assist and enable the successful implementation of the WTO TBT Agreement. “Notifications relating to regulations, changes to conformity assessment procedures, or new or amended standards regulations, standards and conformity TBT Enquiry Point Office, with the goal can have an impact on trade and it is assessment procedures. of consolidating the technical important to ensure that South Africa does

“The principle of transparency knowledge of government not intentionally or unintentionally restrict or underpins the TBT Agreement, experts regarding the hinder open trade,” adds Scholtz. and this is attained preparation, analysis Anyone can access the WTO ePing portal through the framework and submission via https://epingalert.org/en to receive of notifications, the of technical alerts and updates on the regulations establishment of enquiry regulations. issued by WTO member states. The site points and publication “The SABS has has a search function that enables users to requirements,” says Jodi the responsibility research product specifications by market Scholtz, lead administrator of coordinating and or country and by industry classification. at the SABS. These TBT services are available for free

“In essence, all states that Jodi Scholtz, and are intended to encourage transparent are members of the WTO have lead administrator, SABS global trade.

Risk and reward

Policy certainty is a deciding factor for doing business with any country. Alastair Currie talks to Lebo Leshabane, CEO, iX engineers, about the firm’s diversification strategy in the SADC and sub-Saharan region.

What is iX engineers’ experience in the SADC region?

LL We’ve completed numerous successful projects, some under the WorleyParsons name prior to the name change to Worley, and others as iX engineers.

What we’ve found is that conducting business with governments outside South Africa can be challenging, since their operating environment is so different. In some instances, signed contracts are not honoured and governments default on funding agreements, which clearly presents a business risk. We try to hedge that risk by insuring against non-payment.

Despite this, expansion in SADC and greater Africa remains one of our diversification strategies alongside continued growth in South Africa; however, where SADC countries have the skills, capacity and resources in place, it’s not realistic to expect to win work there. To secure opportunities, it’s therefore important to have a unique proposition, or to present a bankable turnkey concession model. Establishing local partnerships achieves the most flexibility and business benefits.

Where do you see the growth?

We categorise countries based on their risk profile. Key countries where we see opportunity for public sector infrastructure projects include Botswana, Rwanda and Zambia. Across the board, we also focus on private clients. In Mozambique, for example, we work for multinational groups involved in key growth sectors like oil and gas. Work here ranges from pipelines and power stations to the design and construction management of complete settlements for personnel working on these longer-term projects.

As in South Africa, we will focus on our core market segments, namely energy, water, transportation, mining and urbanisation.

Going forward, we want to concentrate more on our build, operate and transfer model because we know it is the most viable for cash-strapped African governments. To achieve this, we work closely with leading EPC firms globally. Our successful concessions to date have been in energy and transportation infrastructure.

Does the signing of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement present meaningful opportunities?

I think it’s a much-needed agreement; however, effectively managing its roll-out and implementation is crucial. Participating countries need to ensure that mechanisms are in place to reduce the risk exposure for companies doing work on the continent. This includes legislation conducive to doing business and clearly stating the regulations around contracting and foreign investment. An enabling environment is vital. Rwanda, for example, is a country that welcomes the concession model.

Lebo Leshabane, CEO, iX engineers

Is giving back an important part of doing business in Africa?

As in South Africa, we apply the same operating philosophy on SADC projects when it comes to community upliftment, job creation and skills transfer. South Africa has a great need for increased social investment. In many cases, however, that need is even greater in many parts of Africa. Our infrastructure designs cater for this. An example would be the installation of a community borehole as part of a turnkey water project.

Does iX engineers work with international donor agencies?

Yes, we do. In fact, our largest donor project to date was as a member of the design team on the Saint Helena Airport project. This was funded by the UK’s Department for International Development.

We have also completed planning work in South Sudan, which was funded by the World Bank, and work in South Africa for USAID in Mangaung and Polokwane.

What is iX engineers’ key focus for South Africa during 2021?

Water and sanitation are at the top of the list. At present, only around 33% of South Africa’s wastewater treatment plants are functional. We want to help resolve this challenge, restoring these plants back to full operational capacity.

Non-revenue water is an equally crucial focus. At present, South Africa loses 40% or more of its potable water due to failing infrastructure. Delivering solutions for desalination and reuse, as drought mitigation and water security strategies, are integrated areas.

Zeekoegat WWTW

How can you contribute personally as an engineer and business leader?

Seawater reverse osmosis desalination, Cape Town I’m part of the Steering Committee for the South African Water Chamber. Our mandate is to foster public-private partnership investments in the water sector. The establishment of a water regulator is one of our key objectives as part of national government’s Public Private Growth Initiative.

Internally, iX engineers is continuing to mentor, train and upgrade its teams to adapt to new technologies. Ensuring that we have a shared vision and purpose makes iX engineers even better equipped to deliver legacy projects in South Africa and Africa.

The African Continental Free Trade Agreement came into effect in January 2021 and serves as a working policy for intercontinental imports and exports. Alastair Currie speaks to Chris Campbell, CEO, Consulting Engineers South Africa (CESA), about partnership opportunities that could unlock mutual value within the infrastructure arena.

Opportunities for African engineering integration

Does FIDIC Africa welcome opportunities for engagement with CESA firms?

CC Definitely. We share similar infrastructure challenges and opportunities in areas like energy, urban planning, sanitation, and water. We also commonly experience funding shortages, which presents a strong case for the exchange of proven ideas and practical solutions.

The important point to emphasise is that it’s a partnership approach and must be inclusive in terms of skills exchanges, community upliftment and mutual financial benefit. The upside is that there’s already an invaluable network in the form of the FIDIC Group of African Member Associations (FIDIC Africa). This is a regional body that forms part of the International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC), an umbrella entity that is present in more than 100 countries via national member associations like CESA. CESA forms part of FIDIC Africa, which currently has around 18 member countries, with the membership base continuing to grow. Most Southern African countries are members, so that’s a good starting point for business engagement.

A further benefit of being part of FIDIC is that its contract suite is one of the most accepted globally. The FIDIC suite, for example, is one of the World Bank’s preferred contract agreement frameworks for infrastructure projects. FIDIC’s regionalisation focus sets out to reinforce this to the benefit of all FIDIC Africa chapters in securing work, including with local organisations like the African Union and African Development Bank.

Key FIDIC goals include the establishment of global best practices, the creation of a knowledge base, and the identification of potential partners. Where African countries don’t have the capacity to form their own association, CESA and its African counterparts can assist. These associations provide the essential and credible linkages that can viably facilitate the South African export of engineering, contracting, product and services solutions to the benefit of all parties. Phase II of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project is a good example of where South African and local companies have formed joint ventures on this megaproject.

Chris Campbell, CEO, Consulting Engineers South Africa

How would possible implementation work?

Throughout Africa, there’s a pool of exceptional engineers that can maximise their collective contribution to infrastructure development via pan-African participation. That forms the basis for proactive joint ventures on national, foreign direct investment and public-private partnership projects. Combined with design, this presents the opportunity to specify appropriate technologies that are affordable, sustainable and locally maintainable. A multidisciplinary consortium model can achieve this.

The starting point, though, is the business risk, which applies equally when considering business opportunities in any country around the globe. Here, bilateral country-to-country agreements would greatly mitigate the risk for South African built environment businesses.

Diversification is a recognised strategy, but South African companies cannot expect to achieve quick wins in Africa. It’s not a South African conquest approach and there’s already intensive competition within the SADC and broader regions from external countries including China, Brazil and India.

Historically, there are examples of South African companies, particularly top-tier contractors and specialist subcontractors, that have run into challenges when working in Africa, resulting in some major financial losses and retrenchments at home. In contrast, consulting engineering firms are far less exposed, especially where work in Africa is secured via major funding agencies like the World Bank, UN and USAID.

Could the SA consulting market face increased competition from external firms?

Unless it’s an internationally funded consortium project, foreign firms would not qualify in terms of South African legislation. That’s unless of course they establish operations in South Africa and meet local

regulatory requirements, which has happened in the past and successfuly so, contributing to the growth of our own local capability. It is worth noting, though, that South African engineering capability has always been held in high esteem the world over.

Why has BEPEC stalled and should it be remodelled and relaunched?

Initiated more than 10 years ago, the Built Environment Professions Export Council (BEPEC) concept germinated within the CESA fold. From there, it evolved into a standalone organisation with the express aim of bringing all built environment professionals and contractors together under an umbrella body to trade collectively with Africa and the world.

As a separate, partially member-funded entity, BEPEC had a key objective to work in line with the broader Department of Trade, Industry and Competition (DTiC) exports strategy in assisting in the planning and coordinating aspects of international trade missions that provided potential opportunities for built environment professions and contractors. These would of course further increase the demand for construction plant and equipment, all in turn exported from South Africa.

BEPEC did become one of the DTiC’s Export Councils. The challenge, however, was that although the money raised by BEPEC was matched by the DTiC, in line with their grant policies, BEPEC’s own member-derived funds had become insufficient to gain meaningful traction without other sources of external funding. There were also only two full-time BEPEC staff members, hence operational costs were kept to a minimum. As the economy started to decline and financial pressures increased, companies seeking to lower their own operational costs started reducing member subscriptions to organisations like BEPEC, and began to withdraw, so sustaining this excellent initiative became much harder.

BEPEC is parked for now; however, as indicated earlier, BEPEC is an offshoot of CESA. So while it goes through this difficult period, CESA has volunteered its support in a caretaker role for the foreseeable future.

Where can the DTiC do more?

Going forward, the rationale for BEPEC remains very sound; however, the possibility of relaunching it depends on greater policy clarity from the DTiC in terms of its national Export Council strategy. While specific sectors or goods are catered for, there doesn’t appear to be a holistic and integrated strategy for a construction sector Export Council.

DTiC support for South African trade pavilions at exhibitions on the continent would help consulting engineering firms, construction companies, manufacturers and suppliers promote their services and capabilities; however, the current realities in view of the risks related to the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic have understandably created the need for such interventions to be put on hold. That said, this should not have meant that all B2B initiatives facilitated by the DTiC’s government-to-government relations in respect of trade had to grind to a halt as well. The virtual platforms that exist make it equally possible to have such exhibitions and exchanges – you just need to be more creative in your approach to make them work. The recent launch of Construction Alliance South Africa (CASA), of which CESA is a member, is a proactive step towards uniting our industry locally. We’ve been too fragmented in the past. Therefore, we need a collective approach when engaging with government on issues of common interest.

As an industry, we’ve been too dependent on tenders, instead of being involved up front in joint master planning. We need to fix the challenges at home first and connect all the dots. Then, at some stage, one could approach CASA to drive the BEPEC rejuvenation.

And in closing?

An outward, Africa-wide focus should form part of a sensible diversification strategy, rather than a survival tactic to counter the dearth of current infrastructure opportunities in South Africa. Where consulting firms are exploring opportunities on the continent, we’d strongly encourage them to talk to CESA, which currently hosts the FIDIC Africa Secretariat, about network possibilities rather than going it alone.

Priority Number One for CESA and our member firms is to encourage home-grown excellence and the need for service delivery. Expectations are high that the South African government’s infrastructure-led economic recovery will begin to mobilise in 2021 as we all work to reverse the devastating impact of Covid-19.

A vibrant South African and SADC economy will directly and indirectly have lasting benefits for all African trading partners. Here, a formal government-to-government alliance approach would work best.

South Africa

Tracking water consumption is made easy by Water Wise

The Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) aims to reduce water demand and increase supply to our growing population and economy to ensure water security by 2030. Currently, our waterstressed country faces economic water scarcity due to issues with the country’s water infrastructure, an ever-increasing demand on a limited supply and other environmental factors.

Keeping track of water usage through the Water Footprint Assessment, founded by Arjen Hoekstra, is a step in the right direction that shines light on water use patterns in different aspects of society. With a deeper understanding of water consumption patterns and water balance, water utilities and municipalities can work towards improving their existing water-supply models, as well as addressing water wastage such as non-revenue water, and excessive use and leakages, in order to reduce water losses in large distribution networks.

End-users such as homeowners also encounter

leaks, which can be easily detected if households monitor their water use by taking regular water meter readings. To assist people with this, Rand Water’s environmental brand, Water Wise, has developed a Water Wise calculator, which serves as a simple tool to estimate household water use and assist people in detecting high water-use activities and even leaks. The calculator, through a question–answer system, generates a water usage chart and an estimated cost (R) of the household’s water bill in a month. This estimated value should not be used to dispute municipal bills, however, as the value generated is based on general South African water use statistics. This calculator aims to assist the end-users to be responsible in ensuring optimal use of the water they receive.

Achieving this will contribute to the bigger picture of reduced water demand, ensuring a sustainable supply of water for South Africa.

www.randwater.co.za and click on the Water Wise logo

Sand is well known for shifting, especially where wind and rain are prevailing factors, which can overwhelm and undermine coastal structures unless countered. This was the case for Nhoxani Beach, an idyllic residential Eco-friendly project on the Santa Maria peninsula in Maputo Bay, dune rehabilitation Mozambique.

Over the past four years, various new sites have been established on the peninsula’s waterfront, bordered by lush indigenous coastal forest and bush that have been preserved by the founders of the concession property.

One site needed urgent control measures to prevent wind and water erosion – a situation aggravated historically by local fisherman and boat skippers taking refuge in the bush and cutting wood to keep warm in winter.

Having completed his research, Mike Braby, Nhoxani developer and shareholder, decided to specify Terraforce’s earthretaining and erosion control system. Once an agreement and design were in place, Terraforce’s purpose-designed concreteretaining wall blocks were trucked from EFS Construction, a licensed manufacturer based in Mbabane, eSwatini, to Maputo.

The blocks were then shipped via dhows (local boats used for fishing) to Santa Maria, under the watchful eyes of Terraforce-recommended contractor Ben van Schalkwyk of BRW Projects, who designed and supervised the installation of the Terraforce wall.

Indigenous vegetation

Following completion, the Terraforce retaining wall was painstakingly planted with indigenous vegetation using local labour. It then took another couple of years for construction of the housing development to begin.

During that time, the wall has performed optimally in retaining and stabilising the slopes, keeping the dunes at bay from the homes that now line this pristine waterfrontage.

The Terraforce retaining wall was extensively planted with indigenous vegetation using local labour

Collapsing banks

As Van Schalkwyk explains, the installation proved to be no mean feat. The wall itself covers 400 m², designed with four 3 m high interconnecting terraces – the highest point reaching 12.4 m.

“Getting the concrete foundations placed (each terrace having its own) proved challenging, as the dune bank was constantly collapsing,” says Van Schalkwyk.

“An Agri drain was placed behind the wall to prevent water build-up that could cause future damage. We also placed bidim® behind the wall, as well as cement-stabilised backfill – all the way to the top – to provide extra stability,” he continues.

Getting the concrete foundations placed

The terraces nearing completion

ENGINEERING

futureproof plants

Maintaining and growing the water economy is vital for sustainable socio-economic development. IMIESA speaks to Chris Braybrooke, GM: Marketing, Veolia Services Southern Africa, about how innovation makes the difference.

How would you describe the state of WTWs and WWTWs in SA at present?

CB It’s a complex problem. The current statistics available from the Department of Water and Sanitation report a steady state of deterioration in the functionality of water treatment works (WTWs) and wastewater treatment works (WWTWs). Figures range from around 50% to much lower for some municipalities; however, one of the most pressing concerns is the approximately 41% non-revenue water loss statistic.

What’s the impact in terms of urbanisation?

The shift from rural areas to towns and cities is a global trend. This is particularly evident in Africa and South Africa, where unprecedented urban migration patterns have severely challenged the capacity of existing infrastructure to deliver essential services. As a result, WTWs and WWTWs are increasingly being overloaded beyond their design capacity.

Can we achieve ‘quick wins’ to bring faltering systems back online?

Through coordinated public-private partnership (PPP) participation, industry and government can come together to effectively clear bottlenecks. Veolia operates on an engineering and procurement model. As a proven technology solutions provider, we can mobilise and execute WTW and WWTW projects on any scale. We do this either via a build, own, operate and transfer (BOOT) model, or through the direct sale, installation and commissioning of our technologies.

Larger-scale plants for towns and cities require medium- to longer-term planning and commissioning. However, Veolia’s modular, containerised solutions are designed to provide more immediate solutions, even on the same day or within short timeframes of a few months or less.

In Lesotho, for example, we’ve successfully deployed truck-mounted purification units that are designed to abstract river water and deliver this on the spot as safe drinking water. These units are produced at our factory in Sebenza, Gauteng, for the local and African market.

How can Veolia assist in bridging the technology gap?

The starting point is for municipalities to update their asset management registers. To function effectively, they must have a clear condition assessment understanding.

Working with the municipality and its appointed consulting engineers, Veolia can then assist in developing an optimal operations model that improves overall cost and process efficiencies.

Chris Braybrooke, GM: Marketing, Veolia Services Southern Africa

At our project for Cape Town’s Bellville WWTW, for example, our solutions doubled the capacity. In addition, the plant footprint is now 25% smaller than the original one. This is thanks to the installation of membrane bioreactors (MBRs). Ideal for the treatment and reuse of industrial and municipal wastewater, MBRs combine a membrane separation process such as microfiltration, ultrafiltration or reverse osmosis with a suspended growth bioreactor.

To keep pace with urbanisation and population growth, municipalities must embrace new technologies. In France, for example, Veolia has commissioned underground WWTWs below city parkades, which is another example of smallfootprint technology.

Veolia’s modular, containerised solutions are designed to provide more immediate solutions, even on the same day or within short timeframes of a few months or less

Are environmental considerations top of mind?

Veolia always puts the environment first. That’s the rationale behind the Group’s Impact 2023, which aligns Veolia’s multifaceted performance model with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. All our solutions are aimed at reducing the carbon footprint and reversing climate change.

More frequent and extended droughts are a recurring concern. This makes water conservation and water security planning a major priority. Our strategy is to equip municipalities for their longer-term requirements. This especially applies to water reuse.

Agriculture and industry are the two primary sectors for this, but we must not rule out reuse as a potable source. In terms of the latter, our BOOT plant in Windhoek is a classic example. It is believed to be the first WWTW in the world to resupply drinking water.

Desalination is also a viable option, and we have extensive experience locally. Examples include the 15 Mℓ plant we designed and commissioned in Mossel Bay.

Through our integrated Waste and Energy business units, we also promote a sustainable circular economy. Examples include wasteto-energy ventures, and the commercial beneficiation of WWTW sludge into products like fertiliser.

Does outsourcing O&M make financial sense?

The proposed Water Resources Infrastructure Agency mentioned in South Africa’s 2021 Presidential State of the Nation Address is an encouraging sign of renewed investment in this vital sector. This could unlock more PPP opportunities, as well as a more concerted drive by municipalities to outsource operations and maintenance (O&M). This is especially the case where there are skills and funding gaps. O&M contracts are certainly a viable way to speed up the restoration and recovery of underperforming plants. O&M contracts also minimise the risk of cost overruns so that municipalities stay within budget. Through Veolia’s technical training support, we can also train municipal treatment plant personnel on the latest cuttingedge technologies.

Chris Braybrooke, GM: Marketing, Veolia Water Technologies South AfricaVeolia’s 15 Mℓ desalination plant in Mossel Bay

Does Veolia have working municipal O&M examples in South Africa?

Our 15-year contract for Overstrand Municipality in the Western Cape is an excellent example. In terms of our agreement, Veolia has 50 key performance indicators (KPIs) that need to be complied with. These KPIs range from specifications to availability.

Even under the challenging Covid-19 lockdown conditions, Overstrand’s water and wastewater infrastructure ran optimally without a single interruption. The same can be said for all Veolia plants managed via O&M agreements worldwide. This type of assurance gives clients and communities major peace of mind.

And in closing?

Upgrading infrastructure must form part of a long-term master plan in line with town and city geospatial growth projections. That’s why our systems can be designed up front to be scalable in modular phases to handle the estimated process volume requirements, say, 20 years into the future. The mistake is for utilities to think short term and then get stuck with a plant that’s difficult and overly expensive to retrofit.

It’s a proven fact that investing in the right technologies and solutions partner up front achieves the best return on investment over the longer term.

www.veoliawatertechnologies.co.za

Data sent to the cloud can be analysed by water utility operators to plan maintenance

Taking the pressure off with digitalisation

The water utility sector has made great strides in the uptake of digital technology; however, there is still plenty of scope for improvement. Because technology has evolved and the prices of smart devices have decreased, it is now possible for the water industry to achieve digital transformation.

Smart monitoring technology allows for asset optimisation in the water utility sector

Sean McCree, manager: Product Management at ABB, believes that utilities need to start with a clear strategic plan: “Ripping out all the existing hardware is probably not the best approach. Utilities can divide the water network into discrete zones and decide on how to identify what is needed to address each challenge. Effectively, it is best to start small by adding to existing technology. In this sense, smart sensors are the perfect starting point, as they can be placed on a motor, pump, bearings or gearing. They are easy to connect and use, without having to invest in new, expensive systems.”

Wireless smart sensors are a low-cost, easyto-install digital option where operators can use remote monitoring for the early detection of problems. With sensors, maintenance actions can be cost-effectively planned before functional failure. This results in reduced downtime, eliminating unexpected production stops, optimised maintenance and reduced spare parts stock. Sensors can also turn traditional pumps into smart, wirelessly connected devices. This approach measures vibration and temperature from the surface of the pump and uses it to develop meaningful insight into the pump’s condition and performance. This includes details such as pump speed, vibrations, misalignment, bearing condition and imbalance. In addition, smart sensors attached to the motors, which are connected to the pumps, can detect a drop in water flow based on the output power of the motor.

Insights and early detection

When sensors are used in variable-speed drives, the data can be uploaded to the cloud via a remote monitoring solution. This allows for data from the drive, motor and pump to be analysed together, providing insights on the health and performance of the complete powertrain.

While water companies are always monitoring their networks for changes in pipe pressure and the flow of water (which can indicate problems such as blockages and leakages), sometimes the first warning they receive is when a customer notifies them of a burst water pipe. Digitalisation can trigger the earliest possible warning.

There is increasing pressure on utilities to lower their total cost of ownership and high leakage rates. The rapid development of realtime sensing and monitoring technologies for improving early leakage and water quality anomaly detection is an effective way to address these challenges. By combining smart monitoring technology with drives and motors, water utility operators can secure pre-emptive asset management optimisation and, in the process, drive a significant shift from reactive to real-time monitoring.

ABB ACQ580 drive series ensures optimal operation of water and wastewater pumps

Easily erectable, economical tanks a big success

The Circotank range launched by Structa Technology during South Africa’s first lockdown in 2020 is rapidly becoming a market leader. The range offers a robust, yet economical solution to water storage.

The Circotank is manufactured from cold-rolled galvanised steel plate, which is stiffened with an anti-buckling profile in a secondary rolling process. Tanks are assembled on-site and a PVC liner is installed to ensure a watertight structure.

Circotank is offered in two model ranges. The Midi line-up caters for tank sizes from 1 000 ℓ to 20 000 ℓ capacity, while the larger Maxi models field tanks with capacities from 100 000 ℓ up to 1.5 Mℓ. supplies the tank and stand as a complete solution, which includes an optional site construction service.

Circotank is manufactured in the Structa Meyerton facility and is shipped and erected across South Africa.

Midi and Maxi applications

The Maxi is ideal for bulk water storage applications that include process plants, firefighting tanks and the delivery of potable water to village communities. These tanks stand on a concrete ring beam foundation and are constructed in circular segments on-site. No cranes are used, and it thus offers an economical solution both in terms of building speed and ease of transport.

The smaller Midi tanks have found successful application in rural water schemes, as well as water storage at schools and clinics. The 10 000 ℓ capacity tanks on elevated stands are popular products and, again, a crane is not required for their installation. Structa

A Midi tank housed on a purposedesigned tower manufactured and supplied by Structa as a turnkey solution

Robust and Reliable Water Storage

Maxi Series: 100kL - 1,500kL Midi Series:

5,000L - 20,000L

ADVANTAGES

• Highly economical cost to volume ratio • Easily transportable, especially for multiple tanks • Easy assembly, even at elevated heights • NO CRANES REQUIRED • Robust steel tank with high life expectancy • Replaceable liner allows for extended life

Manufactured by Structa Technology (Pty)Ltd

BBBEE Level 1

MEYERTON | Tel: 016 362 9100 watertanks1@structatech.co.za Director: rodney@structatech.co.za | 082 575 2275 www.structatech.co.za | www.circotank.co.za Manufactured in SOUTH AFRICA

More sustainable engineering detail now needed in WULAs

Ever-increasing pressure on water resources is leading to a greater focus on sustainable engineering detail in proposed water-related structures – a global trend now reflected locally in new water-use licence application (WULA) requirements.

There is a substantial shift in world best practice related to the comprehensive integration of engineering aspects with environment, social and governance (ESG) issues and financial sustainability in all projects,” says Jacky Burke, principal scientist at SRK Consulting.

“This shift – which SRK has already made – is driven from the levels of the UN and various participating entities across the globe, such as the International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD),” she continues.

Aligned with global best practice in ESG and sustainability, in facilitating the efficient use of water and to minimise pollution, the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) has issued in-depth engineering specifications that are now required as part of a WULA. SRK has been anticipating this changed approach. Burke highlights that far more detail is now required for the engineering designs that support WULAs, before the DWS will consider the submitted application. The WULA submission will now have to include a proof of concept, design and drawings to the required level, and a construction quality assurance (CQA) plan.

She notes that the WULA process has been regulated since 2017, when Government Notice R267 set out the procedural requirements for WULAs and appeals.

An off-stream storage dam that would require the approval of engineering design works for the authorisation of water use prior to construction

An in-stream storage dam that would require the approval of engineering design works for the authorisation of water use prior to construction Jacky Burke, principal scientist, SRK Consulting

“The DWS has now developed technical advisory notes (TAN) and design checklists to give effect to the WULA regulations and help its case officers to undertake the initial assessment on submitted WULAs to check readiness for review by DWS Engineering Services,” Burke explains. “In line with ESG best practice, this framework will also assist applicants in addressing the engineering requirements, which must now be conducted up front and not after submission.”

It is hoped that these changes will speed up the processing of WULA submissions, although they will certainly require a greater investment in upfront work by project developers. Insofar as these new requirements represent a positive movement towards responsible engineering, this new approach is fully supported by SRK Consulting, says Burke.

She notes that, in addition to the requirements outlined in the TAN from the DWS, there are two design checklists – one addressing all Section 21 water uses in terms of the National Water Act (No. 36 of 1998), and the second specifying the requirements for waste licence applications in terms of the 2013 Waste Regulations under the National Environmental Management: Waste Act (No. 59 of 2008).

Proof of concept

Outlining the new requirements, she said the proof of concept may involve sitespecific investigations, field and laboratory testing, other relevant assessments, and the required engineering of all structures.

“This aligns with the new global approach towards the construction of earthworks and engineering structures, to consider both the technical aspects as well as the ESG requirements,” she says. “It requires that the holistic feasibility of the concept or design must be proven in order to assure the DWS that the stability of the structure over the intended life of the facility is adequately engineered.”

The approach taken by the DWS is in line with that of global organisations like ICOLD, which has updated water and tailings dam standards. In terms of this approach, the structural risk must be assessed, and the identified risks must be mitigated by suitable engineering works, which are to be incorporated into the designs and CQA plan submitted with the WULA.

Design level

“Under the new arrangements, the design level that is acceptable to the DWS is stated in its TAN,” says Burke. “It is based on the Board Notice 138 of 2015 from the Engineering Council of South Africa, which provides the various stages of a project in its Regulation 3(2).”

Stage 2 is a level of design that is generally inadequate for regulations requiring a quantified performance but may be adequate in some projects. At this level, the concept design criteria would be established, and a preliminary concept design would be prepared. The client would be advised regarding further surveys, analyses, tests and investigations – including the establishment of regulatory requirements – which need to be incorporated into the design. The concept would be refined to ensure conformance, and the deliverables would include a preliminary design.

“A Stage 3 design is the basis of quantified performance assessment and subject to review by authorities,” Burke continues. “In this stage, the concept would be developed to finalise the design and outline specifications, which would incorporate a cost plan and define the financial viability of the project, as well as a programme for implementing the project.”

The regulatory requirements are to have been built into the Stage 3 design, which is to be reflected in design drawings, including draft technical details and specifications.

“Stage 4 comprises documentation and procurement, which is essentially the preparation of tender documentation and the procurement of construction services,” says Burke. “This can be done once the WULA is approved and a WUL is issued.”

The fifth stage addresses the general condition in an issued WUL requiring as-built drawings to be submitted on completion of construction. This is the implementation phase, which culminates in the issuing of certificates of completion and the submission of reports to authorities.

CQA plan

The other important element that the DWS now requires in a WULA submission is the CQA plan. This document establishes the procedures that will verify that construction is in accordance with the applicant’s construction drawings and specifications.

“The CQA plan must show that the planned procedures will meet the appropriate regulatory requirements and will lead to the development of the documentation that needs to be provided to the regulatory authority,” she explains.

The objective of this plan is to provide independent third-party verification and testing. It must demonstrate that the contractors and installers have met their obligations in the supply and installation of components and materials according to all the requirements of the construction drawings, the construction specifications and the regulatory requirements.

While the new DWS requirements for the submission of WULAs will undoubtedly demand a greater investment of money and time in the early stages of a project, the overall result will be a positive one, according to Burke.

“Developers will be more prepared for their project implementation, and the interests of safety, water conservation and environmental protection are more likely to be served,” Burke concludes.

A dam that can pose risks to downstream communities and the environment if not adequately engineered and maintained

Greywater reuse in landscapes

As the demand on surface freshwater increases due to a surge in urbanisation, development and population growth – and the future supply of surface freshwater remains uncertain – businesses and landscapers have started to focus on alternative water sources.

Greywater is one of the new approaches being considered to address water needs. In response to this, Rand Water has created a Water Wise Guide to DIY Constructed Wetlands manual that focuses on greywater reuse, as well as provides information on the installation and implementation of a greywater system.

Defined as wastewater that is derived from the domestic and household use of water for washing, laundry, cleaning and food preparation – and does not contain faecal matter – greywater is used for activities that do not require potable water, such as washing down hard surfaces, flushing toilets, and irrigating gardens and landscapes.

It is most commonly used to irrigate business and domestic gardens and landscapes. Plants such as rosemary, lavender, Olea spp., bougainvillea, Cape honeysuckle, Italian cypress, bearded iris and petunias thrive on greywater, as do most tough, drought-tolerant plants. One should avoid using greywater on acid-loving plants such as begonias, azaleas, gardenias, camellias, hibiscus, fynbos, proteas and ferns for long periods.