9 minute read

Labour-intensive Construction

from Imiesa October 2020

by 3S Media

EPWP Infrastructure Sector?

Advertisement

This definitive overview of the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) during the 2004/05 to 2018/19 period highlights its failure to create sustainable employment and deliver infrastructure.

By Robert McCutcheon

Within South Africa, there are insistent demands for public infrastructure and housing. These demands for public services lie at the core of current community discontent. Communities are also demanding jobs in an environment where levels of unemployment are extremely high and disturbing.

The narrow definition of unemployment, which is the one always reported in the media, tracks those who are actively seeking employment. For all South Africans, it is over 27%. The broad definition includes those who have given up looking; it is over 37% for all South Africans. In turn, disaggregation reveals far more disturbing results. For black South Africans, the figure stands at around 46%. The next worst affected group is the 16 to 35 age group, at 68%.

Not surprisingly, employment creation is a national priority. And work is the means whereby we recreate ourselves and the world around us. It provides an income and contributes to personal and communal dignity.

However, another component of the dire situation in South Africa is the fact that employment opportunities need to be created for large numbers of people who have little or no education and very few formal skills. The lack of education and skills are largely the disastrous legacy of the 1951 Job Reservation Act and the iniquitous 1953 ‘Bantu’ Education Act.

Economic growth

Economic growth is widely postulated as the solution. However, in the absence of adequate economic growth and low levels of education and skills, what is the solution?

In South Africa, public works programmes are acknowledged as having a role to play. The 2011 National Development Plan recommended that public employment programmes would form a component of employment strategy until 2030. Labourintensive industries were to be encouraged.

SA’s Expanded Public Works Programme

South Africa’s Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) is one of government’s strategic responses to the triple challenge of poverty, unemployment and inequality.

The greater use of modern labour-intensive methods (LIC) was at the intellectual core of the EPWP. LIC is the technically sound and economically efficient substitution of human effort for non-essential, fuel-based, ‘heavy’ equipment. It generates a significant increase in productive employment among ‘targeted labour’1 : the poor, unemployed and unskilled. By ‘significant’, what is meant is an increase of at least 300% to 650% in employment generated, without compromising on cost, time and quality (once systems, including training, have been established). The range varies for different categories of construction. ‘Earthworks’ provide the main opportunity for this substitution. Earthworks comprise over 50% of the cost of most civil infrastructure projects: excavation, haul, unload and spread. Think ‘lots of small earthworks’, not ‘mass earthworks’.

Legislation, regulations and procedures were introduced to promote LIC. However, LIC still hasn’t gained the traction it was meant to. A review of the available data confirms this.

During the 15-year period between April 2004 and March 2019, the EPWP was allocated R1 540 153 million.2 Of this amount, some R1 149 835 million was apportioned to the Infrastructure Sector. In the end though, a total amount of R253 741 million was spent – of which the EPWP Infrastructure Sector component only came to R179 229 million.

The degree of discrepancy between allocation and expenditure vividly illustrates the public sector’s well-known lack of capacity to deliver at national, provincial and local levels.3 However, overemphasis upon pervasive incapacity within the public sector shouldn’t distract us from manifold shortcomings in the implementation of the EPWP’s Infrastructure Sector itself.

Between 2004 and 2019, expenditure on infrastructure generated over 1 260 000 person-years of employment.4 This is far less than should have been achieved. The large expenditure of public funds should have generated a huge increase in productive employment for the poor and unskilled – together with the concomitant, essential skills development (mainly for matriculants) required to organise and control on-site construction and maintenance.

Key deficiencies

The author provides argument and evidence to substantiate the following critique. In the first instance, the EPWP’s Infrastructure Sector is a programme in name only. It has failed to establish any sort of construction programme in the sense of a series of planned projects constructed using LIC. In fact, it continues to be an ad-hoc collection of disparate, individual projects funded mainly by the MIG and simply labelled a programme.

A cornerstone of LIC is that payment should only be made on completion of set individual or group tasks. A competent, trained supervisor5 sets the task; however, the fundamental importance of output-based remuneration for this type of project has been ignored. Paying a daily wage without any link to productivity has undermined the cornerstone. The remnants of this cornerstone were destroyed in March 2020 by the official decision to pay an hourly minimum, without any reference to production.

It was mandatory to construct particular categories of infrastructure labour-intensively: low-volume roads, stormwater drainage, sidewalks and trenches. The mandatory conditions for the expenditure of funds on the LIC construction and maintenance of these particular categories of infrastructure have neither been obeyed nor enforced.

The original mandatory requirement relating to competence of the consulting engineers entrusted with EPWP/LIC projects has led to NQF 5 and 7 requirements in tenders. The EPWP has claimed that numbers of people have been trained. The unimpressive results demonstrate that this training has not resulted in LIC.

Furthermore, analysis revealed that the totals paid for professional fees and wages were not very different from one another. This is a travesty. Expenditure on wages should far outweigh professional fees. Essentially, an elaborate, ineffective process has led

to an enormous waste in time, effort and expenditure. The physical quantity of assets has not been recorded in the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) system. It is therefore impossible to assess the value obtained for the expenditure of funds and human effort. Neither can one facilitate an offset of the value of assets created against an expenditure, which is currently assumed to be payment to labour.

Furthermore, there is still no linked programme of training and construction for the full NQF 4 level qualification of ‘hands-on’ construction processes site supervisors.

A new approach required

In relation to expenditure on public infrastructure, the author recommends disentangling LIC from the complex, cumbersome and now outmoded MIG and PIG regulations and procedures that have failed to promote it. The web of confusion and contradiction and the inappropriate M&E system must also be removed from association with the provision of public infrastructure, particularly small-scale municipal-type infrastructure.

A new approach is required – or rather, a re-evaluation of an approach that relied on the contract for greater use of LIC. The basis would be the Framework Agreement between Cosatu and the Construction Industry in 1993, which was incorporated into the National Public Works Programme in 1994.

As an industry, we need to unashamedly maximise the efficient use of LIC for the construction and maintenance of public infrastructure. We need to forbid the use of non-essential fuel-based heavy equipment for those mandatory categories of construction, namely low-volume roads, stormwater drainage, sidewalks and trenches.

Technical progress since 1994 means that more mandatory categories could be included. We shouldn’t use ‘cop out’ clauses like ‘wherever feasible’ or meaningless, feeble terms such as ‘labour-friendly’ or ‘labour-enhanced’.

Task-based work is essential

In principle, ‘A fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work’ makes sense.

However, in LIC, wage payment must be dependent upon the completion of a set ‘task’. Trained supervisors and the use of ‘output based remuneration’ would ensure ‘a fair day’s work for a fair day’s wage’. As expressed in the Code of Good Practice for Employment and Conditions of Work for Special Public Works Programmes: “A ‘no work – no pay’ rule must apply except in the following circumstances: illness… injury”.

We also need to review the wage paid per task assessed against an accepted output of effort. The wage per task would be considerably more than that paid on the EPWP’s Community Work Programme (which is yet another source of confusion at the local level). A review of the wage scale should be considered alongside the statutory construction sector wage rates agreed annually.

Another recommendation is the reinstatement of the original rule that “works identified to be undertaken by LIC must be constructed through that method”. Failure to do so must be enforced by the client’s refusal to pay for works performed incorrectly according to the contract. This would be simpler to enforce than the current situation, where no one knows for sure whether LIC is being used correctly.

The Department of Public Works and Infrastructure should review the Ministerial Determination and DORA in accordance with this new vigorous approach. The Attorney General would have to give full support through rigorous enforcement of conditions of contract. A truly independent body, independent of the EPWP, should be appointed to visit all LIC sites and have the authority to enforce the legislation and regulations.

Furthermore, the scale of professional fees and the overheads must be in line with the principle that experienced consultants should be appointed for ‘large’ contracts. They should be required to transfer their experience to others, either by free transfer or by partnering. The concept of the consultants ‘learning on the job’ – at the expense of the project – must be eliminated.

A new M&E system is essential. In the first place, quantities must be recorded. In the second, end results should be based upon the amount of infrastructure constructed according to a specific number of person-years of human effort.

To address the lack of progress to date on proper technical training, the author would advocate that municipalities and SOEs like Sanral establish ‘in-house’ linked programmes. These would formally link construction and maintenance to the training of ‘hands-on’ single-site supervisors holding the NQF 4: Construction Processes Site Supervisors qualification. Critical for the execution of results-based outcomes, more independent and entrepreneurially minded supervisors could also receive supplementary training and become small contractors.

Going forward, Covid-19 has placed even greater pressure on South Africa’s fragile economy, with unemployment now rising to unprecedented levels. LIC and EPWP infrastructure investment are part of the solution. As an industry, we need to work together to ensure alignment and implementation.

*Robert McCutcheon is a professor emeritus and honorary professor at the University of the Witwatersrand’s School of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

1 'Targeted labour’: local people whose human effort is replacing fuel-based heavy equipment. It does not include those who would have been employed during conventional equipmentbased construction (traffic control, security, cleaners, etc.). 2 In the period 2004 to 2019, the value of the rand fluctuated between R5.50 and R15.00 to the US dollar. 3 Although there has been a severe inability to spend the allocated budget, the allocations indicate the scale of internal resources (ostensibly) available to South Africa. 4 In EPWP language, one ‘full-time equivalent’ is equal to 230 days per year. 5 NQF 4 level – the supervisor could be a contractor.

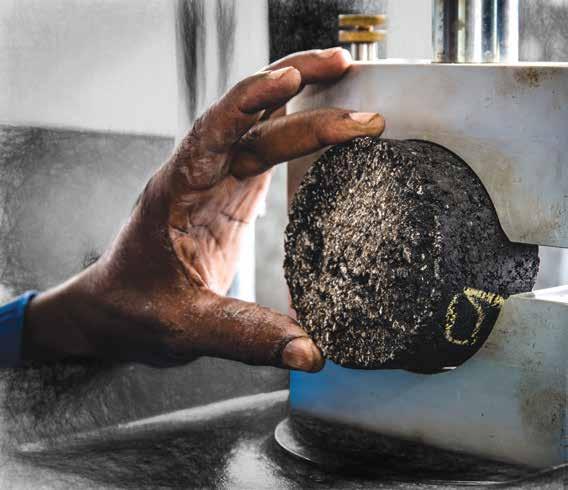

ACCOUNTABLE FOR QUALITY

AECI Much Asphalt is southern Africa’s largest manufacturer of hot and cold asphalt products.

We don’t just promise quality. We hold ourselves accountable for it. Process control laboratories at every plant and on site continually monitor and test our processes and products. Our customers can rest assured they are placing and compacting quality asphalt.

17 static plants • 5 mobile plants • extensive product range stringent quality control • bitumen storage • industry training

T: +27 21 900 4400 E: info@muchasphalt.com W:www.muchasphalt.com