4 minute read

MUNICIPAL FOCUS

from ReSource May 2020

by 3S Media

Gauteng’s landfill future

Responsible for roughly 33% of the country’s waste, Gauteng is by far South Africa’s biggest waste generator. But is the province making adequate provision for its long-term waste management needs?

Advertisement

By Danielle Petterson

ince 1998, when the last large S regional municipal landfill was licensed and developed in Gauteng, the province has consumed significant amounts of landfill airspace and seen the closure of several landfills throughout the province.

Speaking to delegates at an IWMSA seminar on the topic ‘Addressing the landfill airspace crisis in Gauteng’, Kobus Otto, director, Kobus Otto & Associates, provided an overview of the state of the province’s landfills.

“Without sufficient landfill airspace in Gauteng, the municipalities in Gauteng will not be able to render effective and environmentally sound waste management services to millions of residents,” he said.

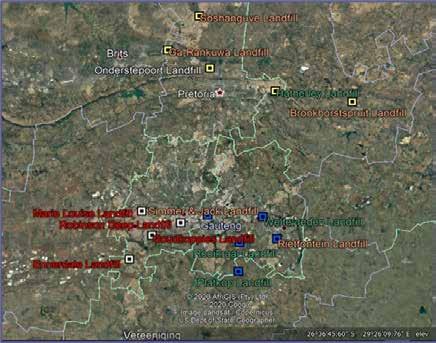

Currently operational municipal landfills

Ekurhuleni has five large regional landfills operated under contract: Rietfontein (GLB+), Rooikraal, Weltevreden, Platkop, and Simmer & Jack (all GLB-). While Rooikraal, Weltevreden and Platkop all have an estimated remaining life of more than 20 years, Rietfontein and Simmer & Jack only have an estimated remaining life of 5 to 10 years.

Tshwane has one large regional landfill, one medium landfill and two small landfills operated by the municipality. These are Hatherley (GLB-), Ga-Rankuwa (GMB-), Bronkhorstspruit (GSB-), and Soshanguve (GSB-). Hatherley has an estimated remaining life of more than 20 years, while Bronkhorstspruit, Ga-Rankuwa and Soshanguve have only 5 to 10 years remaining. The Onderstepoort landfill was recently closed.

Johannesburg has three large regional landfills – Goudkoppies, Marie Louise, Robinson Deep (all GLB-) – and one medium landfill operated by the municipality – Ennerdale (GMB-). The estimated remaining life for all four of Johannesburg’s landfills is less than five years. According to Otto, there is no real space

at these landfills for further cell development to create additional airspace.

Increased transport distances

There are no municipal landfills towards the north of Ekurhuleni and Johannesburg, nor towards the south of Tshwane. As a result, some areas already have long travel distances to reach landfills. As landfills close over the next 5, 10 and 20 years, these travel distances will increase significantly.

Predicted municipal landfills between 2030 and 2040

Otto stressed that, as waste will need to be transported over longer distances in future, Gauteng has a growing need for effective waste transfer systems.

Increased transport distances will result in significantly increased collection and transport costs, coupled with decreased collection efficiencies. There will be an increased pressure on remaining landfill infrastructure, longer turnaround times for collection vehicles at landfills, and negative impacts on environmental compliance.

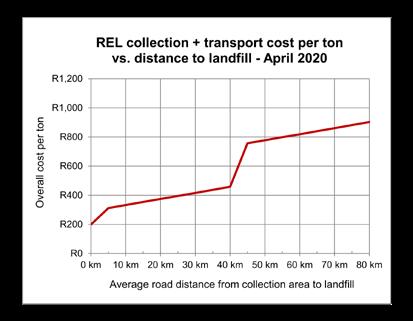

Based on synthetic data (costs, times, etc.) – which includes a truck with driver and a collection crew of six – the overall per-tonne costs associated with the collection and transport of waste to landfills using large rear-end loaders have been predicted, as shown in Graph 1.

As may be seen from the graph, per-tonne costs rise steadily as the distance to landfill increases. Above a distance to landfill of roughly 40 km, the per-tonne cost increases dramatically, due to a drop in the feasible number of collection rounds per day from two to one.

Waste management alternatives

The waste hierarchy forms the basis of all South Africa’s waste projects and is generally seen as the solution to the landfill airspace shortage. But the unfortunate reality is that South Africa is not compliant with the waste hierarchy and there is no balance between landfilling and alternatives, stated Otto.

He highlighted the fact that South Africa has no cohesive set of waste industry targets. Instead, it appears as though we are shooting in all directions trying different technologies.

Waste diversion from landfill is considered the preferred option and various alternative waste treatment technologies are available internationally. Only some of the treatment technologies implemented in South Africa were sustainable; many failed. Otto pointed to, among others, the discontinuation of municipal separation-at-source projects, as well as the closure of several ‘dirty’ MRFs (materials recovery facilities) since the Robinson Deep MRF was shut down during the early 1990s.

Otto explained that the two primary requirements determining the financial viability and therefore sustainability of alternative waste treatment technologies are mostly ignored: 1. Appropriate feedstock (quality and volume) 2. Sustainable markets for various offtakes. “Without these, we can have the most advanced technologies and the most committed staff, but it is not going to work. With sustainable markets to drive demand for and subsequently the price of offtake upwards, the waste industry, both formal and informal, will source appropriate feedstock – whatever it takes,” he said.

Recycling is meant to create thousands of jobs, but the industry is facing serious problems. Prices for recyclable material in South Africa are extremely sensitive to international influences. Otto stressed that there is no sense in using donor funding to support the recycling industry if, when that funding is withdrawn, the project collapses. The only solution is to create sustainable local markets.

“Driving the markets up will drive the demand up, will drive the prices up and will drive the sustainability up. This is the basic principle of making waste minimisation successful in South Africa,” he concluded.

GRAPH 1 REL cost per tonne vs distance to landfill (Graph developed by John Clements)

Note: The X-axis represents the one-way distance to the landfill. The ‘fixed’ cycle time used was 180 minutes: 120 to 150 minutes for actual collection and 30 to 60 minutes’ turnaround time at the landfill.