BUILDING

Findings and recommendations from the Copenhagen People Power Conference, September 2023. Developed by ActionAid Denmark.

Photo: Clayton Conn

Photo: Clayton Conn

INTRODUCTION

PAGE 3

CELEBRATING PEOPLE POWER

PAGE 5

THE ROLE OF PEOPLE POWER IN SOLVING THE CRISIS OF TODAY

PAGE 14

THE IMPERATIVE OF SUPPORTING SOCIAL MOVEMENTS IN THE FIGHT FOR CLIMATE JUSTICE PAGE 15

THE ROLE OF MOVEMENTS IN PEACEBUILDING EFFORTS PAGE 18

SUPPORTING DEMOCRATIC MOVEMENTS IN AN AGE OF GROWING AUTOCRACIES PAGE 20

HOW TO BE BETTER ALLIES

FUNDING PAGE 24

PAGE 23

CAPACITY STRENGTHENING PAGE 29

ROLE OF DECISION MAKERS PAGE 32

ROLE OF CSO’S PAGE 34

PROTECTION MECHANISMS PAGE 37

WHAT’S NEXT

PAGE 39

NEXT STEPS WITHIN THE WORK STREAMS PAGE 40

NEXT STEPS IN CONVENING STAKEHOLDERS PAGE 41

APPENDIX

ENDNOTES

PAGE 42

PAGE 47

INTRODUCTION

Our current era of intersecting global crises calls for deep, structural reconfiguration of politics and power. Historically, social movements have been instrumental in shifting power, influencing public opinion, and creating lasting impact by organising the people affected and their allies. On many occasions, social movements have moved far beyond what was considered possible among traditional civil society, and dared to shake power structures that some nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and civil society organisations (CSOs) were unwilling to address. 1 This is now acknowledged broadly: A recent United Nations report concludes that social movements are at the forefront of efforts to foster social engagement, democratic participation and responsive governance, and that NGOs and governments must embrace and enable social movements as essential partners in ‘building back better ’from the intersecting crises of today. 2 If we are to successfully respond to today’s most pressing crises, we need to understand the role that social movements play, and the way in which we can support them.

This is why ActionAid Denmark (AADK), with support from more than 15 Danish and international partners, hosted the Copenhagen People Power Conference (CPPC) on the 28th and 29th of September 2023. The conference was primarily funded by Danida, Open Society Foundations and Humanity United.

The conference was organised with three connected aims:

1)Deepen understanding of the power and potential of social movements in the fight for climate justice, peace and security, and democracy and digital rights;

2)Create a broad agreement among key international stakeholders that movements are critical in order to create structural change across the world;

3)Find specific ways to support and collaborate with movements to amplify their strengths and potential for success.

Through engaging with representatives of movements, governments, parliaments, academia, the private sector, multilateral institutions, foundations, media, activists and civil society organisations from across the world, we explored a range of people power movements and their abilities to address major crises of our time and to advance towards a more just world. We also highlighted and celebrated movements around the globe through the People Power Award 3 , selected from more than 150 nominees.

280 people from 60 different countries attended the CPPC in person and various sessions were streamed for online participation. 4 The program 5 was a mix of plenary talks, panels, outcome-oriented sessions and workshops. Speakers and panelists included a diverse range of profiles, from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, to representatives from large scale donors, to prominent researchers and activists.

This report recaps key discussion points and recommendations, provides a resume of key agreements, initiatives and collaborations, and elaborates on how these will be carried forward after the conference.

The report is written with the aim to create relevance for both conference participants and others interested in becoming better movement allies. The outline is designed so that sections can be read and used independently.

Outline of report

The first section, ’Celebrating the Power and Potential of Social Movements’ clarifies key terms and portrays the winners of the People Power Award 6 , which exemplify what people power looks like today, and highlight the remarkable struggles in which they are engaged.

The second section, ‘ The Role of People Power and Social Movements’ , focuses on the three core issue-areas addressed at the Copenhagen People Power Conference (CPPC): climate justice, democracy and digital rights, and peace and security.

The third section, ‘How to Be Better Allies’ , provides concrete recommendations to external actors on how they can best support social movements. It covers five key areas:

1) Funding: How bilateral and private donors can better support social movements throughout their lifecycle.

2) Capacity strengthening: How tools, peer learning and mentor programmes can be developed to fit the needs of movements.

3) Role of decision makers: How governments, multilateral institutions and politicians can be true allies of social movements.

4) Role of civil society organisations: How and when civil society actors can support non-violent resistance struggles.

5) Protection mechanisms: How the UN and donors can be strategic allies to enhance safety protection of social movements.

The final section of the report,‘ What's Next’, summarises new initiatives that came out of the conference, and proposes how to keep momentum and emerging work streams alive.

CELEBRATING PEOPLE POWER

CELEBRATING PEOPLE POWER

‘People power’ , ‘resistance struggles’ , ‘nonviolent action’ , ‘ protest groups’ , ‘grassroots organising’ , ‘large scale mobilisation ’are terms often used interchangeably to refer to the organised efforts of ordinary people pushing for social, political, economic or cultural change. While the choice of terminology depends on context, culture, and the nature and focus of the group itself, in this report we refer to such efforts broadly and collectively as social movements: groups of people with a shared identity and common goal(s) that engage in collective action. As elaborated in AADK’s publication ‘building a movement mindset’ 7 social movement refers to the way ordinary people participate in politics and move power through a combination of organising and protest. Social movements are civilian-based, involve widespread popular participation, and alert, educate, serve, and mobilise people. 8 People power tactics stems from civil disobedience and direct actions, such as strikes and boycotts, being different from formalised pathways to change (eg. elections, the parliamentary system). However, in practice many movements engage in both people power and institutional methods. 9

In recent times we have witnessed people power drive national and global agendas on egalitarian economy and social reforms (Occupy, Pink Tide), women’ s rights and sexual harassment (“#MeToo”), racism and systematic abuse of power (Black Lives Matter), democracy and rights (Arab Spring), and climate justice (Fridays for Future). In alignment with these much-celebrated global movements, every day, all over the world, we see people pushing for change at local, national, and international levels.

To draw attention to the critical work and achievements of movements today, AADK established the People Power Award 10 In response to an open call, more than 150 movements from diverse corners of the world were nominated. The nine finalists were highlighted in an audiovisual presentation 11 at the CPPC. From confronting corrupt and repressive regimes, to challenging exploitative industries and mega-corporations, countering oppressive societal norms, and protecting our precious ecosystems, these movements exemplify the power of collective action to catalyse positive change.

Three award winners were ultimately selected, and the following portraits of each provides concrete examples of the struggles, tactics, and impact of contemporary social movements.

THE SAMYUKTA KISAN MORCHA

(JOINT FARMER’S FRONT)

Uniting Indian farmers in an unyielding movement for fair agricultural policies.

WHERE: INDIA

WHO ARE THEY?

Samyukt Kisan Morcha (SKM) was formed in November 2020 as a coalition of over forty farmers unions in India, that led coordinated resistance against three farming laws with the slogan ‘the Dilli Chalo movement’ (March to Delhi).a The struggle spanned over a year and sought the repeal of these laws, which farmers perceived as unjust and procorporate, and demanded a law guaranteeing a minimum support price (MSP) for crops.b Estimates during the peak of the movement suggest that hundreds of thousands, possibly even millions, were actively participating in various ways, be it on the frontlines of New Delhi’s city limits, through supporting roles in their villages, or digitally through awareness campaigns and other online platforms.c The farmers’ movement in India is an inspiring example of how ordinary people can challenge unjust policies and practices through collective non-violent resistance. It is also a lesson about how democracy and dialogue can prevail over growing authoritarianism and violence. It is a movement that has not only changed the fate of millions of farmers but also, transformed the political and social landscape of India.

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

STRATEGY AND TACTICS

SKM carried out a well-planned and systematic approach, unifying farmers from various states, religions, castes, and backgrounds, emphasising common objectives over individual differencese. SKM’s primary strategy was mass mobilisation, unifying over forty farmer unions under one consolidated front, and raising awareness by initiating discussions and information sessions at village levels, ensuring that every farmer, irrespective of their scale of operation, understood the implications of the new laws. With peaceful demonstrations, combined with a consistent engagement with national media, SKM ensured their concerns remained in the public eye, attracting international attention. Through international outreach, they built broad alliances and support systems beyond their own constituencies, such as with celebrities and public figures, which amplified attention to, and credibility of, their cause.

TACTICS INCLUDE:

■ Prolonged sit-ins at three key entry points to the national capital, New Delhi, namely the Singhu, Tikri, and Ghazipur borders.f

■ Nationwide strikes to galvanise widespread support and nationwide concern regarding the laws.g

WHAT DID THEY ACHIEVE?

On November 19, 2021, after consistent pressure applied by the farmers organisations, the Government of India withdrew all three farming laws.d The farmers welcomed this announcement as a historic victory for their movement, and they continue to raise other issues affecting them, such as debt relief, crop insurance, land rights, and environmental protection.

■ Rallies and marches, often culminating in large gatherings, to keep the continuous momentum alive over a year-long period.h

■ Direct Engagement with the Government, through multiple negotiation rounds, and proposing changes beyond the repeal of the particular laws.i

■ Showing solidarity with other movements in the country as part of a larger fight for justice and equality.j

STOP EACOP

(EAST AFRICA CRUDE OIL PIPELINE)

Standing resolute against EACOP and advocating for a sustainable African energy landscape.

WHERE: UGANDA AND TANZANIA

Winner of ’People Power Award’ 2023

WHO ARE THEY?

Igniting a potential global movement, the StopEACOP Campaign stands resolute against the East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) project, a proposed 1,445 kilometre pipeline from the oilfields of Lake Albert in Uganda to the port of Tanga in Tanzania. If realised, the project will result in forced displacement of communities, destruction of wildlife and climate instability.k The movement unites voices against fossil fuel giant TotalEnergies, and advocates for community-owned renewables and a sustainable African energy landscape.l

The StopEACOP Campaign has brought together local community members, environmental activists, human rights defenders, and climate justice campaigners. The movement is particularly strong in Uganda and Tanzania, but includes supporters and allies globally, from USA to Japan, South Africa and several European countries, particularly in France where there exists a strong resistance to TotalEnergies.mn The movement is growing rapidly and more than one million people from across the world have signed petitions against the projecto, and thousands of people have participated in protests and other actions regionally and globally.p

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

The StopEACOP Campaign is working to build people power from the ground up by working with local communities and organisations.q At a time when powerful corporations wield influence over many local communities, the movement has managed to turn the tables on global cooperations and financial institutions by linking together ordinary people affected at different levels. StopEACOP stands as a global inspiration by showing that it is possible to challenge powerful corporations and governments by connecting highly localised struggles to global climate justice movements and harnessing international support to amplify local voices on wider platforms.

WHAT DID THEY ACHIEVE?

The Movement has managed to halt the construction of EACOP by preventing banks from financing the project.r StopEACOP garnered thousands of signatures on petitions against the project, organised actions at AGM banks and shareholder meetings, and aided community resistance against displacement along the pipeline’s path. This has fostered the global #StopEACOP movement and 27 major banks have since publicly disowned the project, while several investment firms and 28 insurance companies have also pulled away.s

STRATEGY AND TACTICS

The movement has addressed three interdependent areas necessary to create change, at once: The political power (decision makers), the corporate power (fossil fuel companies) and the financial power (financial institutions). StopEACOP is built through a multi-pronged strategy combining community organising, financial pressure, shifting popular narratives and building solidarity between different communities that face the same challenges, and between global climate activists and local communities.

TACTICS INCLUDE:

■ Training local leaders and activists in areas affected by EACOP.

■ Amplifying voices of ordinary citizens through storytelling.t

■ Supporting community efforts to claim collective rights.u

■ Lobbying governments and oil companies to halt EACOP’s approval and construction.v

■ Organising community resistance and protests against land grabs and displacement.w

■ Campaigning to pressure banks/insurers to withdraw financing and insurance for EACOP.x

■ Raising international awareness through social media campaigns, petitions and actions.y

■ Utilising strategic lawsuits to uphold land rights and environmental regulations.z

■ Forging alliances with climate activists globally to apply pressure.aa

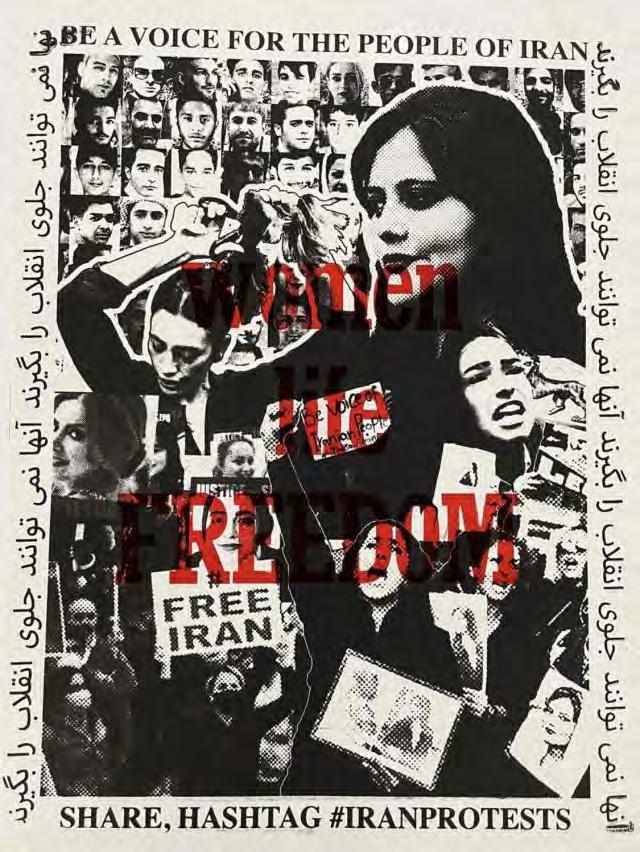

WOMEN LIFE FREEDOM

Bravely challenging gender inequality and igniting hope for all women

WHERE: IRAN

Winner of ’People Power Award’ 2023

WHO ARE THEY?

After four decades of suppression since the Iranian revolution in 1979, the tragic death of Mahsa Amini in custody of the ‘morality police’ of Iran, sparked massive mobilisations and protests led by women. Now known as the “Women, Life, Freedom!” movement, after the chant Jin, Jian, Azadi’ in Kurdish became a slogan that quickly spread across Iran. Initiated by brave women and girls breaking government imposed rules, the movement resonated with frustrations of other demographics, and became a force in demanding an end to an oppressive, patriarchal system.

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

This is an ongoing struggle: Hundreds have died, tens of thousands have been arrestedab, and prominent women’s rights defenders, journalists, students, and civil society activists continue to be harassed by the Iranian government who cling to laws that control the bodily and intellectual autonomy of women.ac In Iran and beyond, WLF fight for the strongest political subject today – the woman: no country is free if women are unfree. Through unwavering determination, WLF challenge societal norms, systemic inequalities and strive for a future marked by empowerment and freedom.

WHAT DID THEY ACHIEVE?

While most members of the movement are young Iranians under twenty-fivead, the WLF has become a broad, diverse movement that transcends gender, class, ethnicity, social division, economic classes, and geographic divisions. Whether the movement achieves their political aims or not, the country has already been transformed by themae: the majority of Iranians in both Iran and throughout the diaspora, regardless of their religion, support the protests and oppose the regime.af Even more so, the movement has resulted in changing patriarchal attitudes in Iran, specifically among the youth, with an unmistakable shift in men’s perspectives towards women and women’s rights.ag

STRATEGY AND TACTICS

Historically, women have been at the forefront of various political and social movements in Iran. The involvement of women in this movement is crucial; research shows that sustainable peace is more likely if women are meaningfully involved.ah The movement has been successful in connecting women’s rights with other issues and types of discontent towards the current

regime, and in attracting support and solidarity from Iranians across societal spheres that have been divided on other political issues, including students, worker’s unions as well as ethnic, religious and sexual minorities. WLF is a leaderless movement, built and developed by the young people inside Iran, providing hope for millions of Iranians living abroad who have, in turn, been involved as crucial supporters. People active in WLF have connected women inside the country with Iranians in diaspora, leading to the emergence of new grassroots organisations and campaigns aimed at supporting Iran.

TACTICS INCLUDE:

■ Mobilising thousands to take the streetsai, expressing their anger with the current regime.

■ Mobilisation through social media, leading to protests across all of Iran’s 31 provinces.

■ The creation of a preliminary version of a “Bill of Women’s Rights”.aj

■ Women removing head scarfs and cutting of their hair in public and on social media are strong symbolic acts of resistance and effective in mobilising support, solidarity and hope, showing how women are taking control of ‘their lives, their bodies, and their freedom of choice.ak

■ Raising international awareness through social media campaigns, petitions and actions, gaining international support for their message and protests.

Illustration: Nat McGartland

Illustration: Nat McGartland

REFERENCES

a PTI. (2020, December 2). ’Delhi Chalo’ explainer: What the farmers’ protest is all about. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/delhi-chalo-explainer-what-the-farmers-protest-is-all-about/articleshow/79460960.cms

b Giri, D. K. & Prakash Kammardi, T. N. (2022, January 26). India’s farmers want the agrarian crisis to end. International Politics and Society journal. https://www.ips-journal.eu/topics/economy-and-ecology/indias-farmers-want-the-agrarian-crisis-to-end-5670

c Live Mint. (2021, May 22). Farmers’ protest: Samyukta Kisan Morcha seeks resumption of dialogue with govt. https://www.livemint.com/news/india/farmers-protest-samyukta-kisan-morcha-seeks-resumption-of-dialogue-with-govt-11621648183300.html

d Giri, D. K. & Prakash Kammardi, T. N. (2022, January 26). India’s farmers want the agrarian crisis to end. International Politics and Society journal. https://www.ips-journal.eu/topics/economy-and-ecology/indias-farmers-want-the-agrarian-crisis-to-end-5670 e Zaffar, H. (2021, September 27). Nationwide strike by India farmers a year after farm laws enacted. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/27/nationwide-strike-by-india-farmers-a-year-after-farm-laws-enacted f PTI. (2020, December 2). ’Delhi Chalo’ explainer: What the farmers’ protest is all about. The Economic Times.

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/delhi-chalo-explainer-what-the-farmers-protest-is-all-about/articleshow/79460960.cms

g Zaffar, H. (2021, September 27). Nationwide strike by India farmers a year after farm laws enacted. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/27/nationwide-strike-by-india-farmers-a-year-after-farm-laws-enacted h Ibid.

i Giri, D. K. & Prakash Kammardi, T. N. (2022, January 26). India’s farmers want the agrarian crisis to end. International Politics and Society journal. https://www.ips-journal.eu/topics/economy-and-ecology/indias-farmers-want-the-agrarian-crisis-to-end-5670 j Mathew, J. (2021, March 4). Farmers’ protests Samyukt Kisan Morcha to block Kundli-Manesar-Palwal Expressway. Business Today. https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/economy-politics/story/farmers-protests-samyukt-kisan-morcha-to-block-kundli-manesar-palwal-expressway-289963-2021-03-04

k Why stop EACOP? StopEACOP. https://www.stopeacop.net/why-stop-eacop

l Beyond oil: Better economic alternatives. StopEACOP https://www.stopeacop.net/beyond-oil

m Meet the #STOPEACOP alliance. StopEACOP. https://www.stopeacop.net/our-coalition

n Euronews. (2023, May 26). Climate protesters face tear gas at oil major TotalEnergies shareholder meeting in Paris. Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/2023/05/26/climate-protesters-face-tear-gas-at-oil-major-totalenergies-shareholder-meeting-in-paris

o See https://secure.avaaz.org/campaign/en/stop_the_total_disaster_loc/ and https://www.totalincourt.org/

p BankTrack. (2023, February 22). Global protests against multinational banks funding East African Crude Oil Pipeline. BankTrack. https://www.banktrack.org/article/global_protests_against_multinational_banks_funding_east_african_crude_oil_pipeline

q Act local. StopEACOP. https://www.stopeacop.net/act-local

r StopEACOP (2023, May 16). SMBC ends involvement as EACOP financial advisor, taking a stance against controversial project [Press release].

s See https://www.stopeacop.net/banks-checklist and https://www.stopeacop.net/insurers-checklist

t EACOP’s devastating impact: Livelihoods worsen amidst environmental damage. StopEACOP.

https://www.stopeacop.net/our-news/eacops-devastating-impact-livelihoods-worsen-amidst-environmental-damage u Hearing delayed again for jailed Ugandan student climate activists. StopEACOP.

https://www.stopeacop.net/our-news/hearing-delayed-again-for-jailed-ugandan-student-climate-activists

v Climate activists call out TotalEnergies for planned climate-wrecking EACOP project as oil giant announces huge profits. StopEACOP.

https://www.stopeacop.net/our-news/climate-activists-call-out-totalenergies-for-planned-climate-wrecking-eacop-project-as-oil-giant-announces-huge-profits w See https://www.stopeacop.net/our-news/petition-for-release-of-four-stopeacop-activists and https://x.com/stopEACOP/status/1717103596091666885?s=20

x See https://www.stopeacop.net/our-news/global-protests-target-banks-funding-east-african-crude-oil-pipeline and https://www.stopeacop.net/ our-news/100-organizations-are-calling-on-lloyds-to-reject-eacop

y StopEACOP. Twitter. https://twitter.com/stopEACOP

z Natural Justice. (2023, April 4). EACOP: East African Court of Justice will hear arguments on court’s jurisdiction. Natural Justice. https://naturaljustice.org/eacop-east-african-court-of-justice-will-hear-arguments-on-courts-jurisdiction/ aa Meet the #STOPEACOP alliance. StopEACOP. https://www.stopeacop.net/our-coalition ab Human Rights Watch. (2023, January 12). Iran: Brute Force Used in Crackdown on Dissent. hrw.org. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/01/12/iran-brute-force-used-crackdown-dissent

ac International Centre for Research on Women. (2024, February 8). Women, Life, Freedom! Why ICRW Stands with the protest movement in Iran. ICRW. https://www.icrw.org/women-life-freedom-why-icrw-stands-with-the-protest-movement-in-iran/ ad Khalaji, M. (2022, September 28). How Iran’s protests differ from past movements. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/how-irans-protests-differ-past-movements ae Safaei, S. (2022, September 23). Iran’s anti-veil protests have already succeeded. Foreign Policy Magazine. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/09/23/irans-anti-veil-protests-mahsa-amini/ af Maleki, A. & Arab, P. (2023). Iranians’ attitudes toward the 2022 nationwide protests. GAMAAN. https://gamaan.org/2023/02/04/protests_survey/ ag Radio Zamaneh. (2022, December 3). ”Woman, Life, Freedom” will gather the regressive masculinity [Translated from Farsi]. https://www.radiozamaneh.com/742590/ ah Principe, M. A. (2016, December 29). Women in non-violent movements. USIP https://www.usip.org/publications/2016/12/women-nonviolent-movements ai The Danish Immigration Service. (2023). Brief report on Iran Protests 2022-2023. https://us.dk/publikationer/2023/marts/iran-protests-2022-2023/ aj A group of women activists. (2023, February 28). We will not take a step back [Translated from Farsi]. Bidarzani. https://bidarzani.com/44374/ ak Mehrabi, T. (2023). Woman, Life, Freedom : On protests in Iran and why it is a feminist movement. Kvinder, Køn & Forskning, 34(2), 114–121. https://tidsskrift.dk/KKF/article/view/134480

THE ROLE OF PEOPLE POWER IN SOLVING THE CRISIS OF TODAY

THE ROLE OF PEOPLE POWER IN SOLVING THE CRISES OF TODAY

Copenhagen People Power Conference (CPPC) was partly built around core issue-areas: climate justice, democracy and digital rights, and peace and security. In the lead up to the CPPC, a framing essay 12 was commissioned on the role of movements in advancing these areas, and during the first day of the conference itself, breakout sessions were held to further discuss and qualify these topics and recommendations. This section will summarise the main points drawn from the conference proceedings, the conference framing essay, and commentary by the conference organisers.

THE IMPERATIVE TO SUPPORT SOCIAL MOVEMENTS IN THE FIGHT FOR CLIMATE JUSTICE

CPPC brought together climate justice activists and scholars from diverse geographies and sociopolitical realities to share experiences and shed light on the critical role of grassroots efforts in advancing climate justice. The session brought to conversations the historical roots of climate change; the importance of collaboration between a broad range of social justice movements in the fight for climate justice; how transnational campaigns can bring together struggles and amplify local voices; the links between energy crisis and human rights, such as how oil and mineral discoveries and exploitation has led to both environmental degradation and grave violations of basic rights; and the necessity of sustaining hope and practising self-care, mutual trust and solidarity.

Why movements matter for Climate Justice

The primary challenge in confronting the climate crisis is a lack of political will. Fossil fuel and other industries that have grave environmental impact hold great economic and political power. They prevent progressive policies in order to protect their interests, and manipulate political leaders, governments, and non-governmental actors to confuse and polarise the public, hindering coordinated action. Ordinary people and their movements hold the key to mobilising citizens worldwide, rebalancing relationships and creating leverage to ensure decision makers fulfil their mandate and steer market forces towards sustainable energy practices. 13 Research shows that climate marches are effective in engaging bystanders and changing public opinion 14; protests and civil disobedience increases public support and have led to declined emissions and policy changes in both democratic and non-democratic countries. 15 Some philanthropy researchers convincingly argue that movements are one of the most cost-effective investments that can be made to stop climate change. 16

In general, there are five key characteristics embedded in the work of social movements which are key to advancing climate justice:

1: Amplifying local voices: One of the most compelling reasons to support social movements is their ability to amplify the voices of communities directly impacted by climate change. Such movements provide a platform for frontline communities to share their experiences and struggles. They humanise climate change, making it tangible for people across the globe. When we lend our support to such movements, we contribute to making the global population aware of climate change’s real and devastating consequences.

2: Bridging divides: The issues of climate change stir conflict and polarisation, but social movements have the potential to bridge divides due to their intersectional perspectives. By connecting climate issues to broader social justice concerns, movements emphasise that climate activism is not confined to a specific demographic because climate change affects us all, transcending political and ideological boundaries. 17 Supporting social movements therefore can help unify efforts and create a sense of shared responsibility.

3: Mobilising diverse stakeholders: Climate justice movements are diverse and inclusive. They consist of individuals from various backgrounds, professions, and regions. This diversity ensures that a wide array of perspectives and skills are brought to the table. 18 By supporting these movements, we enable a collective effort that harnesses the strengths of different stakeholders and encourages a holistic approach to tackling climate change. Diverse, transnational alliances provide local movements with resources, expertise, and global visibility, and can also exert pressure on governments and corporations by bringing environmental issues to international attention.

4. Focusing on structural causes: Social movements call for structural change. The “System Change Not Climate Change” slogan and emphasis on breaking down the oppressive systems that perpetuate climate change is a prime example. 19 When we support these movements, we contribute to reimagining a system that works for the planet and its people.

5: Sustaining hope: The fight for climate justice can be daunting, given the urgency and scale of the problem. Yet, social movements inspire hope: the shared experiences, collective determination, and solidarity among activists help people remain motivated and optimistic, even in the face of immense challenges. 20 By supporting these movements, we bolster this collective hope, ensuring that we continue to press forward, no matter the odds.

Challenges and recommendations

Movements must critically assess their narratives and arguments to the public

Across the broad spectrum of environmental movements, science-based narratives are often used, but they are not enough to ease tensions between cultural and social classes that prevent broad mobilisation. Valuable lessons can be learned from the narratives of environmental movements in Latin America, where indigenous communities are at the forefront in resisting extractive activities that threaten their territories. Their narratives are inclusive, holistic and spiritual, appealing to basic human sense of being and belonging, therefore enhancing the appeal for broader based support. 21

Movements need to expose and debunk the myth of fossil fuel dependency

This means exposing greenwashing practices that might affect emissions (slightly), but which do not aim to change systems and shift power. It also means opposing the ‘ right to development' argument put forward by governments in countries, such as Brazil and El Salvador: while this is often framed as a defense of sovereignty against neocolonial control 22 , this is a predatory type of development, based on mining, agribusiness and large-scale infrastructure projects that leads to land grabs, air pollution, violation of rights, and the destruction of livelihoods. 23

Movements need to provide and support concrete alternatives

While it is crucial to expose unjust and false solutions to the climate crisis, climate justice movements need to simultaneously provide people with images of what climate justice looks like, in order to mobilise hearts and minds. Solutions already exist for an ecological transformation from ‘below’, based on the knowledge and practices of local, place-based movements and indigenous communities. 24 At an international level, there are promising initiatives and coalitions worth backing within the areas of renewable energy, pushing for alternative ownership models that give power back to communities.

It is critical to foster broad coalitions and expand the range of allies

Fossil fuel companies operate and coordinate from local to international level and must be met with pressure on each of those levels. Climate activists and their movements need a wide range of allies beyond their own expertise and specific issue-areas; journalists, social entrepreneurs, workers/labour unions, scientists, researchers, attorneys and policy makers are all potential allies. 25 There is a need to better link areas of politics and reforms at national and international levels, with efforts that deepen engagement and contextualisation through community involvement, training and exchange. The impact of the StopEACOP campaign, for instance, was due to the collaboration between environmental activists, academics, lawyers and indigenous communities. 26

Movements need to confront power in various spheres

Powers within 1) institutional and legal frameworks (visible power) 2) people and networks (invisible power) and 3) discourse, dominant world views (hidden power)need to all be addressed simultaneously. 27 Strategies that address formal spheres and paths of decisionmaking (e.g. advocacy, lobbying) need to be complemented by strategies that influence decisions taking place in networks ‘ behind the scenes ’(e.g. creation of alternative networks, dialogue tactics), and by strategies to confront and change dominant stories and values that are assimilated as ‘true ’without public questioning (e.g. reconstructing local history and knowledge). Allies and support across these spheres are crucial.

Organisers concerned with democracy, corruption, neo-colonialism and environmental activism should join forces

These struggles are not separate but, rather, interconnected: instead of creating separate 'brands' or competing concepts, we should work together, think together, develop new ways of seeing and talking about the world. Given the urgency and consequences of climate change in people’s daily lives, climate activism should be seen as “a form of civic engagement” 28: a right that is encouraged to be exercised beyond environmental groups.

A crucial area where allies can support climate movements is in fighting repressive laws and defending criminalised activists

Even in democracies, climate activism has come under attack 29 and, with significant influence from the oil and gas industry, laws that violate the basic rights to protest and mobilise have been passed. 30 This leaves movements with only the formal, institutional pathways, which have shown to be insufficient and slow in creating the necessary changes. 31

THE ROLE OF MOVEMENTS IN PEACEBUILDING EFFORTS

The peace and security track of CPPC included a panel with scholars and activists across geographical contexts. Conversations addressed a wide range of peace and security challenges, including a review of relevant research into the positive and constructive role of movements in advancing sustainable peacebuilding; tensions between peacebuilding and nonviolent action approaches to addressing conflict; how to prevent atrocities against civilians, as seen in Syria from 2011 onward (including the role of the international community in holding perpetrators accountable); how ordinary people can confront violent non-state actors in their communities and gain a voice in government-led efforts to address chronic insecurity; and the importance of analysing power structures and addressing power imbalances when developing people power and designing peacebuilding efforts.

Why movements matter for Peace and Security

People power movements are a powerful, yet often under appreciated, factor in preventing violent conflict, mitigating, and supporting peaceful and just resolution. These types of movements are also common in contexts of armed conflict: a total of 346 civil wars spanning 99 countries took place between 1955-2013, and large scale nonviolent movements were present in approximately one-fifth of them. 32 In addition, localised, smaller movements have an even higher prevalence in conflict settings (i.e. cases in which terrorists and criminal groups oppress the civilian population), and these movements can help broker local ceasefires, provide for the needs of local civilian populations, and deter violence by armed groups. There is clear evidence for the impact movements have on increasing peace and security. 33

First, movements advance conditions—such as democratic change, accountability, and recognition of a wide range of human rights which can reduce risks of violent conflict and fragility. 34

Second, when a conflict is ongoing, movements can take actions that decrease violence and conflict intensity. For example, in Colombia, communities in conflict zones have developed innovative nonviolent organising strategies to communicate with armed groups, and deter and reduce killing. 35

Third, the presence of people power movements can undercut the recruitment rationale for armed insurgents. By modelling a form of effective and inclusive nonviolent power, they offer an alternative to violence. 36

Fourth, research finds that when movements are present in civil war contexts, they increase the likelihood that combatants will reach a negotiated settlement, as well as the probability of a democratic outcome. 37 For example, Liberian women organised, protested, and held vigils against ongoing war to get parties to the negotiating table, and then they engaged in more assertive and disruptive nonviolent tactics during 2003 peace talks to pressure all sides to come to a binding agreement. 38

Fifth, the use of protests by civil society has been found to increase the likelihood that civil society groups will be included in peace talks, as well as the likelihood that they will be given substantial roles (i.e. full participant, mediator) that give them power in the process. 39 In this way, movements rebalance power disparities among parties and increase the likelihood that peace agreements will be durable and address questions of justice.

Lastly, after peace agreements have been signed, movements can play a critical role in enforcing compliance and accountability to prevent relapse into violent conflict. 40

Tensions and challenges between Peacebuilding and Movement-based approaches

People power movements and peacebuilders often have shared goals—the cessation of violence, and establishment of durable and just peace but their approaches are sometimes in tension with each other. 41

Below are several examples:

Peacebuilders may take an impartial stance that prioritises stability and depolarisation in a conflict, while people power movements may take a stance that prioritises justice. Movements are also often willing to engage in acts of disruption that impose costs on their adversaries, and that could increase polarisation.

Some peacebuilding approaches focus on engagement with clear leaders and representatives of combatant or civilian groups, but at times it can be difficult to discern clear people power movement leadership.

In some cases, social movement leaders fear that entering negotiations could legitimise the authority of abusive parties, and that making concessions would lead to loss of support among the movement’s base. In turn, peacebuilders may be concerned that movements may be radical and unwilling to negotiate or compromise.

In some cases, external donors might incentivise certain movement groups to register themselves and become NGOs, especially during political transitions. Some risks of this shift include creating divisions within the movement, cooptation of the movement, shifting movement activity to meet the needs of external donors, dissolution of the movement’s popular base of support.

Increasingly, scholars and practitioners recognise that both peacebuilding and movementbased approaches are complementary, and both can be pillars of strategies to transform conflict. To ensure a constructive inclusion and collaboration with movements, these tensions need to be addressed openly.

Recommendations

Peacebuilding organisations have a responsibility to inform themselves about what social movements are doing on the ground and to listen to their views and needs. Regular dialogue and mediation sessions may be one way that movements and peacebuilding organisations can bridge the gap.

Donor organisation staff members should receive training and education about people power movements in general, and must be knowledgeable about the specific social movements that are operating in their countries or regions of concern.

Negotiators should prioritise both peace and justice during peace negotiations. Achieving peace requires accountability. Peace is also more likely to be sustained if concerns about justice are considered from the outset of the peace process.

Identify and engage with people power movements at all stages of the peacebuilding process and offer full participation to movement representatives during peace negotiations.

Develop rapid response capacities both to foster movement resilience and to put pressure on groups that use repressive methods against movements.

Create safe spaces for movements to plan, and for individual activists who may be facing persecution.

Build trust by providing convening spaces where movement members can engage in dialogue with armed actors, sensitise armed actors to the community upon which they inflict harm, and reshape their relationship with that community.

Convene international working groups to develop more robust international enforcement mechanisms for severe perpetrators of human rights abuse.

SUPPORTING DEMOCRATIC MOVEMENTS IN AN AGE OF GROWING AUTOCRACIES

The world is facing its seventeenth consecutive year of democratic decline. 42 Even in longstanding democracies, the right to freedom of assembly, and thus protest, is increasingly under attack. 43 While people are mobilising and protesting in greater numbers across the world, civil resistance movement success rates have also declined sharply in recent decades. 44 This issue demands urgent attention, as any useful strategy to reverse waves of authoritarianism will depend on effective, bottom-up, civic pressure. So as authoritarian regimes become increasingly innovative and adaptive by employing new technology and tactics to bypass international human rights law, there is a need for civil society to listen closely to the needs and analysis of local actors. The session on democracy and digital rights brought together activists and movements from some of the most repressive contemporary contexts. The panelists shared perspectives on contextual differences and common challenges, including how to counter threats, (digital) surveillance and criminalisation of activists from state authorities, navigating and sustaining protests when public spaces and formal civil society organisations are shut down; and the important role of diaspora communities and political refugees abroad.

The content in this section of the report is drawn from the conference proceedings, the conference framing essay, and commentary by the conference organisers.

Why movements matter for Democracy and Digital rights

As a result of the current autocratic wave, room for democratic participation is either shut down, or not functioning as intended. People lose faith in institutional processes and find alternative ways of organising and advancing social, political and economic goals. Prodemocracy movements are central actors in processes of democratisation beyond formal practices such as elections: they serve a watch-dog function, bear witness and act against social injustices, give voice to marginalised groups, promote citizen engagement, make claims to policy makers, and express views of ordinary citizens to local governments. 45 They also play a crucial role in pushing for alternatives models and repertoires for practicing participatory democracy. 46

Besides defending and developing democracy, civil resistance movements have been critical in advancing democratic transitions: once a transition against an autocrat occurs, ensuring prospects for democracy and other stabilising factors have proven significantly higher for civil resistance-led transitions. 47 And despite broader, worrisome tendencies, social movements have had significant wins recently, especially for women’s and LGBTI+ rights. While abortion rights have famously been restricted in the USA, the global tendency is progressive: for example, the tireless, decade-long organising and mobilising efforts of social movements across Latin America and the Caribbean have recently led to victories around abortion and reproductive rights, and decriminalisation of outdated colonial laws, such as on same sex marriages. 48

Challenges and recommendations

The following points towards general principles and practices that democratic governments, INGOs, philanthropies, diaspora groups, and others can use to support movements in repressive contexts..

Allies need to understand the context of the struggle when investing in support

The impact of most forms of support to pro-democracy movements have been found to be context-dependent, and meaningful support should “be an extension of (rather than a substitute for) their strategy”. 49 While it is always beneficial to learn from practices, tools and strategies that have proven successful elsewhere, there is obviously no blueprint for successful outcomes. Interventions need to be designed in close dialogue with the movements themselves.

Donors and NGOs need to be committed to stand with movements over the long-term

A partnership is a commitment throughout the ups and downs, including when global media shifts attention elsewhere. Support needs to be flexible and correspond to the shifting needs of the movement along its path. Donors must sustain support during critical moments, be firm, and not shy away when pro-democracy people power movements are criminalised by those in power.

Diaspora activism is key in countries with closed civic space

Diaspora activism helps shed light on the repression and the ‘ democratic ’allies of the regime (e.g. France in relation to Togo) and provides spaces for (re)organising for activists in exile (e.g. Nicaraguans in Costa Rica). There is an opportunity to help diaspora or neighbouring country organisations to prepare for when dictatorships suddenly fall (e.g. Iran) to ensure a power vacuum isn't filled by opportunistic and non-democratic actors. Recognising activist within diaspora communities as important actors and supporting their growth is an important first step, as they are often lack resources and political support.

The digital space is a battleground, and there is a need for increasing investment

Two key areas of importantance:

1)Strengthening digital security for activists, countering spyware such as Pegasus which is a threat to activists globally, as well as training and sharing on how surveillance can be countered through encrypted communication tools, and how to handle social media. Activists and CSOs must focus on building robust networks, engaging in peer-to-peer learning to enhance their collective impact.

2) Developing secure and effective digital spaces for organising against governmentcontrolled narratives and propaganda. Platforms for global connectivity and collaboration connect activists, journalists and citizens with like-minded people and organisations in order to build solidarity in the face of suppression.

Particular learnings and tactics were highlighted across the panelists:

We tend to underestimate that civic space may be uneven within a country. In Georgia, for example, a country with a CIVICUS Monitor rating of ‘narrowed’ , far-right groups are able to exercise their rights and freedom of expression more easily than LGBTQI+ groups.

It is key to keep regional “beacon” countries open, given their role in setting an example to follow, and as hosts to peer-exchanges for others in the region from more repressive contexts.

Businesses can be allies for pro-democracy movements and their support should take the form of both words and actions. They should question the government and apply pressure to restore respect for human rights.

Translating complex new laws into simple and easy to understand language is effective in creating messages about real-world impact on the lives of ordinary people, including broader populations and mobilising through social media.

It can be effective to tap into constitutionally guaranteed rights, such as civic education (e.g. in Kenya), as a way to leverage funding.

Build relationships with key national and regional influencers who can see and speak to local issues, for causes to gain a greater reach.

HOW TO BE BETTER ALLIES

Ugandan queer rights advocate and poet, Stella Nyanzi together with Nigerian feminist and country director in ActionAid Nigeria, Ene Obi.HOW TO BE BETTER ALLIES

There are many concrete measures that multiple stakeholders in the ecosystem around social movements can take to become a better support. In August and September 2023, key actors from civil society organisations, movements, the donor community, academia and the political sphere of decision making met in a series of online roundtable dialogues hosted by ActionAid Denmark and partners. The output was initial recommendations that were qualified at the conference itself. This section provides an update on these recommendations based on discussions and inputs at and around the conference.

FUNDING

How can bilateral and private donors better support social movements throughout their lifecycle?

The donor community plays an important role in supporting social movements. Yet direct grant making to social movements and grassroots organising comprised an average of only 3% of all human rights funding from 2011-2019, which shows that this an under-financed area that is relatively new to many donors. 50 There are, however, funders with long-term experience and well tested tools that can be scaled. Some base their work on a typology of movement growth and phases 51 , while others have specialised in analytical tools and M&E frameworks. 52 In addition, there is no one funding model that is best-suited for all movements or all funders. For example, some funders provide direct support, others provide funding through intermediaries, while others provide in-kind support. There is a wide range of learning materials out there to assist donors in becoming more movement-centred in their work.

The conference brought together actors with different types and levels of experience funding social movement work. Following are specific recommendations provided within four interrelated themes that are considered most important in supporting social movements:

Ensuring flexible, unrestricted, multi-year operational support

Flexible, unrestricted, multi-year donor funding has been identified as helpful in supporting social movements to navigate complex environments. 53

To incorporate these aspects into their funding models, donors may consider:

Terms of funding:

Reducing restrictions about where funds can be used and for what. 54

Increasing the length of funding commitments. Donors must understand the lengthy cycle of social movements, supporting them in various phases without imposing unrealistic timelines.

Reporting requirements:

Accepting grant reporting in multiple languages.

Streamlining accounting procedures. As a concrete example, donors should invest in building administrative systems that can bear the burden of auditing processes, in order to ensure that movements are not restricted by a requirement for receipts.

Selecting report requirements that generate useful information both for funders and movements, and that are tailored to particular movement capacities. Such requirements may vary in terms of evidence gathered (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, narrative), focus (i.e. emphasising impacts and changes over time rather than shortterm program metrics) and formats (i.e., written, verbal)

Challenging unachievable indicators, and emphasising the need for flexibility in measuring progress. Measurements should be co-created with movements, so that monitoring, evaluation, and learning processes becomes less complicated and time-consuming.

Building movement-centred support strategies

Movements draw upon a wide range of civil society, including informal and unregistered entities. They also may exist in repressive environments and lack the structures of traditional civil society organisations. However, they can often persist and make gains in contexts where traditional civil society organisations, by themselves, are inadequate.

Funders can adapt their support to movements through considering the following:

Applications for funding:

Accepting applications for funding in multiple languages.

Creating procedures to fund non-registered entities, especially in contexts where it is difficult for organisations to register as nongovernmental organisations. Addressing challenges, such as lack of bank accounts or state blacklisting, requires creative solutions and empathetic collaboration.

Making it possible for movements to write proposals together, either cross-issue or cross-geography. Donors should support collaborations across issues and regions.

Funding strategies:

Seeing movements as partners walking with movements, learning with them, and using donor influence to support movements through funding and other means (i.e. advocacy in media and among governments, connecting them to networks, amplifying movement messages).

Identifying and working with qualified intermediary organisations that can support movement-based sub-grantees and distribute funding and other forms of assistance. Qualified intermediary organisations know the local context and/or have other kinds of specialised knowledge and adequate administrative capacities to receive grants, which they can then sub-grant to movement actors.

Prioritising listening to movements, understanding their specific needs, and developing processes for trust-building. Donors should also provide space for political conversations, as political understanding is crucial.

Investing in local and grassroots entities that can channel tailored resources and movement support in settings with authoritarian regimes and severely limited civic space.

Expediting funding review/approval processes and planning outside of the normal planning cycle. Donors should be willing to support movements promptly when funds are needed.

Exploring fellowship models to support individuals within social movements.

Managing risks for both grantees and funders

Supporting movements can be highly political work, as many movements by nature are set to challenge powerful institutions and the status quo. Thus, offering movements funding can entail risks for both funders and grantees. For example, funders may face reputational and/or financial risks, and risk that in-country staff may be persecuted. Movements also face risk of security breaches and persecution, as well as risk of funding volatility.

The options below are split into two categories: minimising risks for activists; and minimising risks for donors. However, in practice, risk mitigation strategies for these two groups are often related minimising risk for grantees can minimise risks for donors, and vice-versa.

Minimising risks for grantees:

It is essential that donors listen to movements and not impose their goals and expectations on them. However, donors often will have their own agendas and procedures that they bring to the funder-grantee relationship. Therefore, when supporting social movements, it is particularly important for funders to articulate values and communicate limitations and ambitions. A shared understanding of these matters can minimise damaging power dynamics, and instead, foster collaborative decision-making.

Relying on intermediary funding organisations to provide a variety of movement support. Such support can build infrastructure, resources, networks, relationships, and processes that sustain movements and can respond to emerging crises. It also helps maintain a movement’s independence in perceived and real terms and reduces the risk of co-optation by donors.

Prioritising trust as a foundational principle in their philanthropic relationship, acknowledging the movements’ need for protection and support.

Actively listening to early warning signals from local organisers’ analysis of potential risks, and developing responsive strategies.

Practicing due diligence to ensure that funds go to the actual organisers of movements instead of those that masquerade involvement.

Sharing strategies and tactics with activists for better risk analysis and mitigation.

Adopting communication methods and practices that do not compromise the safety of the movements.

Developing reporting requirements that minimise the need for movements to collect or transmit sensitive data, ensuring that any such data transmitted is stored securely.

Managing risks for donors

Dedicated staff with adequate capacity, expertise and interest in movement work. Funders should invest in their own staff training to ensure program officers understand movements and their work.

Relying on intermediaries for partnership and administrative management.

Establishing clear criteria to assess financial risks, so that both funders and grantees have a shared understanding up front.

Ensuring all staff are trained in digital security practices, and when circumstances require it, physical security.

Donors and intermediary organisations should work together to create a system to avoid fraud and corruption. A step towards this could be the creation of shared practices among intermediary organisations.

Donors must understand the lengthy cycle of social movements, supporting them in various phases without imposing unrealistic timelines. Donors should be partners, walking with movements, learning from failures, and using their influence to amplify movements' messages.

Address the problem of “risk transfer”, whereby donors want to work with movements, but pass on the risk to others. Mitigate risk transfer by:

o Assisting frontline activists and movements in mapping and managing their own risks in a way that is meaningful to them (i.e. not in standard donor tools). For example, a recent study suggests that the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs supports its partners in more robust risk management mechanisms and mitigation strategies, illustrating the donor’s willingness to support the calculated risk that comes with supporting social movements. 55

o Providing adequate support to manage risks, where possible. Agree on roles and responsibilities between donors, intermediary organisations and other specialised partners. Acknowledge where it is not possible to provide support.

o Accepting and incentivising appropriate levels of risk-taking through support from intermediary organisations, which take on risks on behalf of donors. Intermediary organisations can be risk averse due to their own internal priorities, policies and compliance systems, as well as due to the compliance requirements from the donors.

Ensuring Coordination, Collaboration and Knowledge Sharing among movements and their allies

Research shows that coordination among donors of external support is critical and can increase impact. 56 Furthermore, uncoordinated external support to movements can cause harm. 57

Fostering more effective collaboration among donors and other movement allies can involve:

Investing in processes, spaces, and structures that increase knowledge sharing, collaboration, and synergies among activists and movement allies. For example, supporting communities of practice, conferences, networks, coalitions, and learning and research opportunities dedicated to a range of issues related to movements. These could be organised regionally and/or thematically.

Establishing funders' networks that create a wider ecosystem for supporting movements, with inspiration from existing networks providing this support in adjacent fields. Examples of existing spaces are the Lifeline Consortium, Human Rights Funders Network, Peace and Security Funders Network and the Building Responses Together network.

Prioritising collaboration around pooled funds and movement support at donor gatherings.

Governments and multilateral agencies should pursue partnerships with likeminded philanthropic organizations to effectively leverage one another's unique organizational attributes, resources, and networks in order to allow movements greater flexibility to meet their needs and goals, while better ensuring movement unity and cohesion. Greater coordination among governmental, bi- and multilateral, and philanthropic organizations is a key demand of activists.

Coordinating with diverse donors and movement allies to reduce the risk of “group think” where all donors shift to new ways of working, or support and focus energy on the same areas of work.

Standardising reporting protocols to provide data and insight into whether funding has gone to social movements and its efficacy. Donors should be responsible for compiling this data to ensure that grantees are not burdened.

Taking an active role in building bridges between movements/grassroots organisers and traditional civil society actors. Since there tends to be a lack of understanding among many CSOs about what movements are, made evident by the small percentage of overall human rights funding received by grassroots organisations, other actors may view movements as “new players”and as competition for resources.

CAPACITY STRENGTHENING

How can tools, peer learning and mentor programmes be developed to fit the needs of movements?

Skill-building, training, and peer learning efforts are often the most effective external support needed for social movements. 58 Out of all the forms of assistance, training is most consistent in effectively supporting nonviolent campaigns and is associated with high levels of public participation in movement actions, greater likelihood of defections of security forces, and lower fatalities. 59 Popular movements are built on growing, distributed leadership. Therefore, a focus on training new organisers and leaders, and internal leadership development through on-demand, tailormade trainings and mentorship opportunities are particularly necessary. In general, capacity strengthening for providers can support movements throughout their lifecycle with knowledge and tools for how to organise people, build leadership, assess, strategise and develop security plans, strong campaigns and creative actions. This can be through self-paced online courses, webinars and workshops, skill-building sessions, and inperson trainings. 60

Capacity strengthening efforts benefit from being more systematic and sustained. At present however, activists are often involved in one-off training opportunities that follow organisational project timelines of the training provider, rather than of the social movements ’ lifecycle and needs. Although these one-off opportunities can be positive experiences for individual activists, much more can be done to link specific trainings to other relevant opportunities and networks across organisations, and to different training providers, in order to increase the sustainability and effective impact of movements.

The following section provides recommendations to address these challenges and provides more useful and better coordinated capacity strengthening opportunities for social movements. It is based on inputs from the working group of experienced trainers and facilitators from ActionAid Denmark, Leading Change Network, International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, Beautiful Trouble, The Horizons Project, and Just Associates.

Ensure relevant, timely and adaptable support

While social movements are easiest to spot in the middle of their particular campaigns, they are more than just public protest actions: long-term organising efforts, before and after peak mobilisation events, determine the success of a movement and its long-term impact. Support from training providers should:

Be offered throughout movements lifecycle and not just at their peak. Activists who receive training prior to peak mobilisations are more likely to instigate change. Capacity strengthening support should be designed so it is targeted to the various stages of the change process. For an example of this, see ActionAid-Denmark’s GOLD programme. 61

Be adaptable and correspond to emerging realities. Flexibility is key when it comes to identifying a movement's evolving needs, and to responding to emergencies that

do not conveniently follow the January-December project cycle or the end of year planned deliverables.

Be based on the movements' own analysis of where they are in their lifecycle and what types of support are useful to them. For example, see this Cycle Matrix 62 and the Beautiful Trouble Movement Compass Tool 63

Prioritise coaching and mentorship. Long-term mentors assigned to movements can help the movement expand, nurture new leaders, survive short-term losses and develop a culture that reflects their identity and goals.

Develop a community of practitioners

Capacity providers need to build a global community of practitioners that can facilitate the culture and habits of knowledge sharing not tied to project deliverables, across different fields and generations. Some ways to enable this is to:

Support convenings where the organisations/trainers/facilitators/coaches who are developing/contextualising curricula and providing training can learn from each other.

Ensure that all actors involved, from CSOs to donors, are coordinated to accompany movements on their journey, and respect the integrity and local roots of movements, while keeping them globally connected.

Map the specialisations and work that each capacity provider organisation is doing in order to facilitate collaboration and avoid replication. A list of existing resources and networks are provided in the end of this section.

Facilitate a support system that is not tied to specific project deliverables. An example of this could be supporting convenings that enable organisations to learn from each other.

Support strategic analysis and sharing of learnings and tactics

It is crucial to invest in movements ’skills and capacity for self-assessment, analysis and strategic planning, and to support sharing new knowledge. Therefore:

New knowledge should be developed and shared through specific case analysis and research collaboration in alignment with the needs of social movements. Best organising practices, strategies, tactics and creative actions should be shared and adapted to make them accessible and relatable to local actors and circulated through safe channels.

Activists and their movements should be actively engaged in research to theorise, analyse, and develop new knowledge that can be useful for others. Research initiatives should be based on the realities, needs and interests of activists and aim to be applied, providing useful knowledge and links to capacity strengthening efforts.

Monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) efforts should benefit movements. Instead of designing MEL processes based on donor requirements, e.g. activities held or number of activists trained, an emphasis should be put on facilitating continuous learning and analysis, and on developing cases with practitioners in formats that can inspire others. Participatory approaches and qualitative methods, such as Outcome Harvesting and emergent learning tools, are a good starting point.

Materials and programs should be adapted and developed in collaboration with local partners to ensure that language, media, and formats are useful and accessible.

Promoting a movement-minded culture

Social movements have different needs and challenges at different stages. To maximise the impact, capacity strengthening efforts need to be part of a wider culture that actively supports and promotes such capacity, as well as within the organisation. For NGOs and other actors who seek to offer relevant support to movements, this entails:

See capacity development as more than just trainings or a series of trainings. This includes creating a culture of valuing education and training as critical elements for success.

Build the capacity of training providers themselves to have the knowledge, experience and understanding of what long term social movement support entails, beyond just training.

Hire practitioners with experience in organising and movement building, including former or current movement leaders that can serve in mentorship roles.

Work with movements that align with your mission, expertise, values and available resources with the objectives and characteristics of the movement. 64

Partners and existing resources

The following links to online resources are recommended in the effort to learn, align with, and build an ecosystem of different complementary capacity strengthening efforts:

More on supporting movements throughout their lifecycle based on their needs analysis: ActionAid’s MOVE page and its capacity programme GOLD; Movement Netlabs Cycle Matrix; and the Beautiful Trouble’s Movement Compass Tool

See the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict’s ICNC's resource library with material in over 70 languages, moderated and unmoderated online courses, and blog from people on the front lines.

See Leading Change Network’s (LCN) resource centre for a curated multilingual library of community organising resources consisting of training plans, guides, case studies, reports, podcasts and more.

For an excellent resource library of civil disobedience tactics, actions and organising and mobilising principles, translated into nine languages look at Beautiful Troubles free online toolbox.

See the Growers ’Guild hosted by The Horizon’s Project as an example of cross pollination and synergies among capacity providers.

See SNAP guide for nonviolent action and peacebuilding, available in four languages.

For an interactive game to radically transform systems of oppression with a movement-minded methodology, see Building Just Futures by Just Associates (JASS).

The Commons Social Change Library provides an overview of resources on campaign strategy, community organising, digital campaigning, and the Democracy Resource Hub for organisers, activists, and peacebuilders pushing back against authoritarianism with a directory of training organisations.

More on the benefits of external support to movements by Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, External Support to Nonviolent Campaigns: Poisoned Chalice or Holy Grail, ICNC Press, 2021.

To read more on the value of training, see Education and Training in Nonviolent Resistance | United States Institute of Peace

THE ROLE OF DECISION MAKERS

How can decision makers, multilateral institutions and politicians be true allies of social movements?

Representatives from governments, institutions, and politicians from across the world joined the Copenhagen People Power Conference to discuss how decision makers can best support social movements. These actors came together to share experiences and recommend next steps for decision makers to become better allies. A closed meeting for 11 governments was held outside the formal program, under the Chatham House rules.

Decision makers present at the conference expressed wishes to better support social movements, and committed to establish a collaborative community of learning. Several governments shared experiences and best practices regarding risk sharing, the inclusion of social movements in legislation processes at national and multilateral levels, as well as concrete foreign policy support. Some have guidelines in place on how they can best support human rights defenders from embassies around the world. Others have focused on including social movements in UN dialogues. Some have designed ways in which they openly share the risk with social movements stating that: while decision makers who actively support social movements may face severe consequences, such as arrest orders, state surveillance, and risks to personal safety when leaving the country, the price that movements pay is far greater than that of the government supporting them, and inaction is far more costly.

Below follows recommendations on how decision makers can stand in solidarity with social movements and increase their safety.

How to stand in solidarity

Governments should create accessible, safe and healthy civic spaces in which youth and social movements from all areas of social justice can thrive. This involves both speaking up for the legitimacy of movements and a clear legal and political framework of social movement protection through the promotion of rights to freedom of expression, association, and assembly, and a free and independent media that can hold state actors accountable for issues activists face.

Resolutions and joint pledges from multilateral institutions and governments are important to facilitate a narrative shift towards the important role that social movements play in implementing human rights globally, to protect rights to public discussion, and to impact judicial decisions on human rights abuses.

There is a need for ensuring UN agencies and entities are aligned in responding to movements facing attacks and sensitising internal UN staff to their responsibilities in preserving civic space.

Governments should apply pressure or withdraw state support from autocrats who repress movements, in order to challenge the legitimacy of a regime’s actions and deny it practical material or other assistance. Examples are France’s withdrawal of support for the Ben Ali government in Tunisia, and the United States ’withdrawal of support from the Pinochet regime in Chile.

Decision makers should try and push issues that align with social movement values, and consult and involve representatives of social movements in various stages of legislative processes.

As consistency with movement support is important, decision makers should make long-term commitments and support human rights and minorities across the board both in their national-, foreign- and aid policies. In addition, a shared value framework should be created for working with social movements.

Social movements should be invited to participate in international fora, so activists have a platform to speak directly to decision makers. This will add to decision makers ’knowledge of what is being defended, the core of the movement, and the struggles they face. It will also ensure that information from the grassroots and movements is fed into human rights monitoring mechanisms.

Decision makers must support social movements without co-opting their voices, but rather amplifying the voices of movements. For example, visiting dignitaries can give priority to meetings with civil society, including social movements, as they do with foreign government officials.

Decision makers should share messages of support for activists facing crackdowns by authoritarian regimes on social media, which is effective to spark hope for the population affected.

It is imperative that embassy staff are aware of events on the ground and are in contact with grassroots actors as the timely expression of solidarity is impactful.

Decision makers can express in-person solidarity by marching in protests, pride parades and with others at risk and by supporting court cases through the attendance of embassy representatives.

Social movements should be allowed to maintain their independence and be critical of political decisions, while still receiving solidarity from decision makers.

Support should be given to people with activist backgrounds entering the political system to bridge any gap between the movements and institutional responses.

How to increase safety

Multilateral institutions should pass resolutions about situations where freedoms are suppressed to put pressure on oppressive governments.

Governments should blacklist companies that use spyware to monitor civil society and social movements.

Governments should build a system to protect social movements and the CSOs that support them against digital attacks by actors nationally or abroad.

Politicians and governments should provide safety for social movement actors by issuing visas for temporary relocation to those who have been threatened.

There is a need to have UN human rights country offices, so people in emergency contexts do not have to travel to Geneva.

Diplomats should offer safe spaces in embassies or UN offices when social movements are facing attacks.

Governments and other actors engaged in the internet infrastructure should commit resources to improve internet resilience, expand and develop solutions to counter internet shutdowns, or get online access during electricity cuts, exams periods and humanitarian crises.