6 minute read

EXECUTIVE CORNER

Beware of thGAPe

by Darrell Wilkes, Ph.D., International Brangus Breeders Association (IBBA) executive vice president

I must give credit to my friend Dr. Bob Weaber from Kansas State University for finding the perfect word – a simple three letter word – to describe a phenomenon that is becoming more significant in the seedstock industry. In this case, the “GAP” is the difference in average genetic merit of cattle born each year in herds that are using all the tools and technology available to them compared to those herds that are less intense in their use of data and technology.

Like any business in any industry, cattle breeders run on a technology treadmill – like it or not. In order to remain competitive, one must constantly adopt new technology. If you stand still, you fall behind. This has always been true and will certainly remain true for the foreseeable future – not just in cattle breeding, but in every industry that one can imagine.

Technological innovations rarely accumulate in a straight line - a linear advance. Rather, there are certain points in time where a disruptive technology comes along and allows a quantum leap forward. Examples would be micro-processors, the internet, and DNA sequencing to name but a few of the most obvious ones. In our business, examples would be artificial insemination, the advent of EPDs, and the emergence of genomics (DNA testing).

I think we have reached an inflection point in the cattle industry where the cumulative power of technology is allowing the most aggressive users of technology to advance at an accelerating pace in terms of genetic improvement. As this occurs, those who are slower to adopt these technologies run the risk of falling victim to the GAP – that is, the genetic distance between the low-tech herds and the high-tech herds will increase at an accelerating pace.

There has always been a GAP between herds in terms of average genetic merit for traits of importance. This was true long before we had EPDs to help quantify the differences. As far back as the 1940s, and perhaps even earlier, there were hard-nosed breeders who weighed every calf, multiple times, and kept meticulous records. Imagine these folks calculating adjusted weights and ratios longhand – without a calculator (maybe they had an abacus or a slide rule). Even before we understood all the nuance of quantitative genetics such as heritabilities and other parameters, it was understood that “like begets like” – this is just an instinctive understanding of genetics. If you breed fast-growing cows to fast-growing bulls, you’re likely to get fast-growing calves. This is cowboy common sense. But some breeders kept records. They did the math and used their data to select the next generation of parents. Others, it’s fair to say, just eye-balled the cattle and picked those that were bigger (assuming the goal was to increase growth rate).

Image two breeders on opposite ends of town, each with a goal to breed faster-growing cattle. One is weighing calves, keeping records year-after-year, and calculating which animals have the greatest growth potential. The other one is

looking at them and selecting accordingly. Which one do you suppose has a steeper plane of improvement for growth rate? There is no doubt that the guy with the adjusted weights and records will outpace the other guy. I submit that the GAP between these two herds (in terms of growth rate) grows wider in a linear fashion over time.

As new tools have become available, notably the ultrapowerful genetic change tool knows as EPDs, the opportunity to increase the rate of improvement is dramatically enhanced. This is particularly true when we shift our thinking from a single trait – like growth rate in the above example – to multiple traits.

Back in the “good ol’ days” when all we had to work with were in-herd ratios, it was very difficult to achieve elite status across many traits, and especially hard to achieve elite status in a pair of traits that are naturally antagonistic. An example would be birth weight and yearling weight. Nearly every breed of beef cattle that is still economically relevant has been able to hold BW constant, or lower it, while simultaneously increasing YW. Breeders have been able to increase marbling, increase rib eye area, and reduce age at first calving – while controlling BW and increasing growth rate. This is quite remarkable when you stop and think about the complexity of simultaneously improving genetic merit for multiple sometimes antagonistic traits. This could not be achieved without EPDs – not in your lifetime or mine.

But it takes more than EPDs. It also requires what geneticists call disproportionate reproduction. In plain English, this means getting a large number of progeny out of the most superior animals. Again, in plain English, this means AI and ET.

In summary, when you take conventional EPDs, add in the boost from genomics, and then add in AI and ET, it is not like adding 1 + 1 + 1 + 1. It’s more like: 1 + 2 + 3 + 4. The message in this essay is not intended to discourage anybody or scare anybody off. On the contrary, it should be seen as encouraging and uplifting for one very simple reason. Namely, none of this technology is discriminatory. It does not favor large over small, or wealthy over non-wealthy. You do not have to be a large outfit or have a big bank account to implement these technologies. I submit that your cost per pregnancy from AIing to the elite sires in the breed is no higher than your cost per pregnancy from using a $10,000 natural service sire. A genomic test costs the same whether you send in 10 samples or 200.

The chart included is for illustration only. It is not reflective of actual and specific data but depicts the accelerating pace of genetic improvement and suggests that the gap between herds is likely to grow wider unless steps are taken to take full advantage of the tools and technologies.

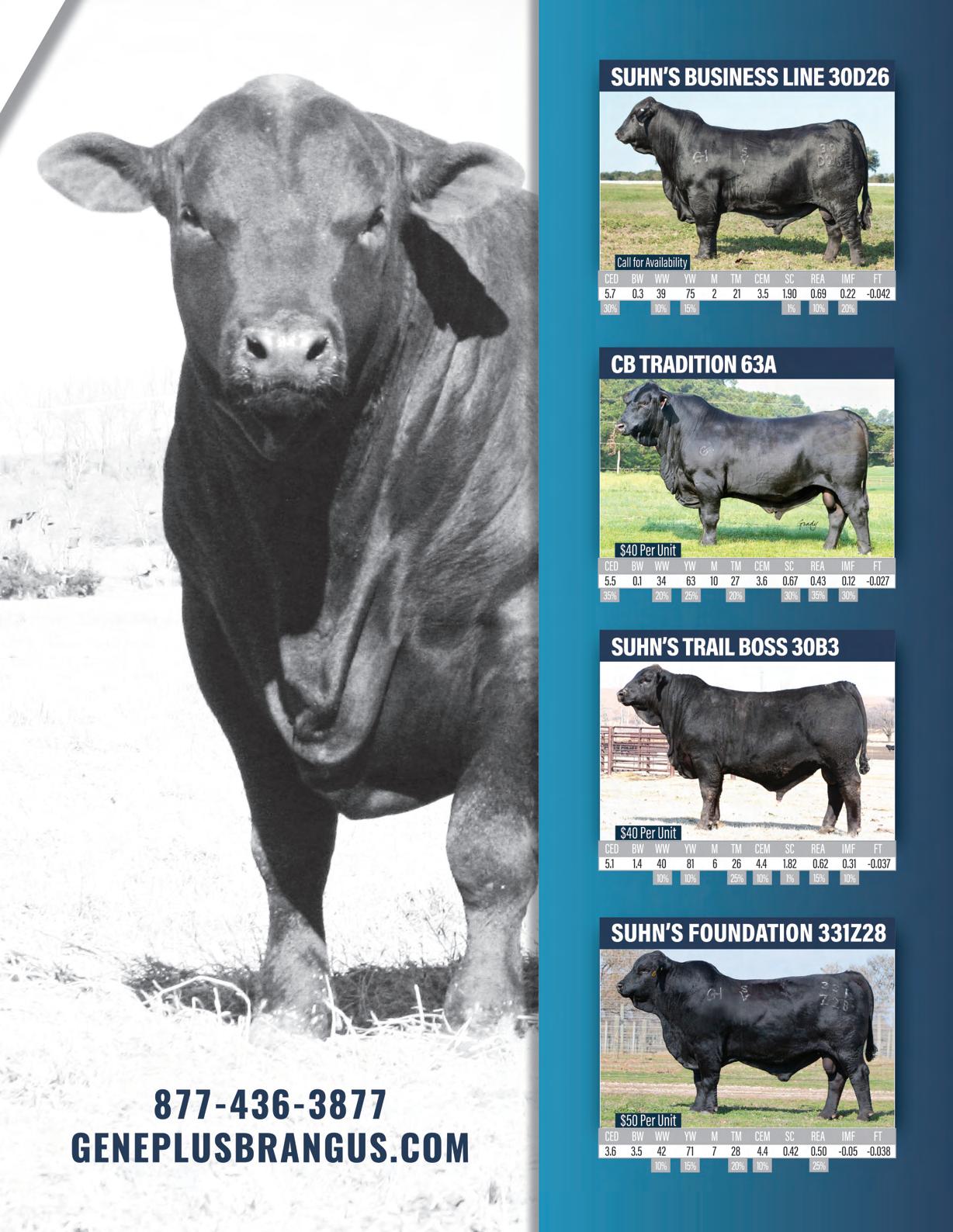

GENEPLUS