The Foreword

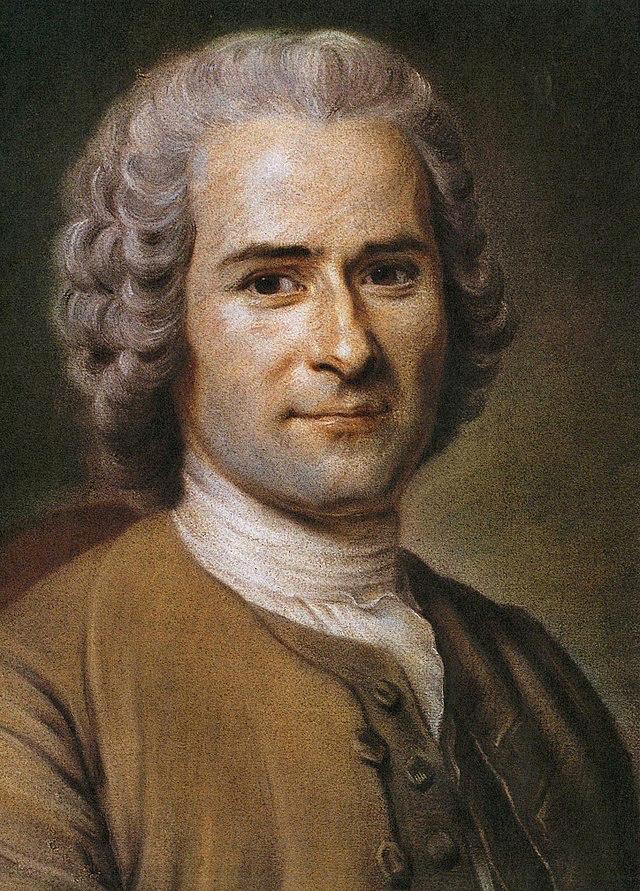

Across time and literature, humanity has remained fixated on the idea of an ideal society – yearning to reach this state which is epitomised in descriptions of places such as Camelot or Heaven The inverse: dystopias (which are imagined states in which there is great suffering, typically totalitarian or post-apocalyptic) have sparked as much interest, with both philosophers and authors struggling to define what a worst-possible society would look like. In this edition of The Thinker, G+L students delve into their own perception of utopias and dystopias, considering literature like the Hunger Games and Maze Runner and evaluating philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Stuart Mill. Read on for thought-provoking articles on the ideal, the unacceptable and the unattainable!

Yours Sincerely,

Nina, Maya, Antara and Aurore

An introduction to Rousseau: The problems he found with society and his idea of a Utopia by Phoebe Watson

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a prominent philosopher in the 1800s that had many opinions on society and how problematic it had become The introduction of governments and industrial cities, he thought, had ruined the modern day man, who he now viewed as selfish, greedy and unhappy as a product of this development His idea of a Utopia, “an imagined place or state of things in which everything is perfect”, was ahead of its time, yet this idea still shapes the way people and philosophers think today

The problems which Rousseau found in society were primarily linked to traditional development He believed that when humans lived in nature they were free and lived simple yet fulfilling lives However, when they began to coexist more closely and live together, destructive emotions such as jealousy and pride began to form. He called this the “corruption of man” by society – because he thought that humans were born good and pure, but were tainted by civilisation. He also thought that humans were born free and equal to one another, but that society imposed conflict and injustice on them This inequality between one another was normalised, but it wasn’t in any way natural or instilled in the beginning, according to him Instead, he idealised the “noble savage ” , a conceptual idea that people living in the wild were in reality better off because they didn’t face the stress and inequality that came with modern, built up life

He claimed that it all started with people feeling unequal to one another When people started to form governments, ideas of private property were created Owning this private property created unfair advantages and inequality This caused people to become jealous of each other and unnecessarily competitive. When a few select people hold all the wealth and power, others become oppressed and unhappy.

While one may think that technological advancements help development and efficiency, Rousseau thought that it increased unnecessary consumerism and isolated people from one another, some could afford to implement these changes, and others couldn't, so they would fall behind in development, once more increasing inequality. People lost their sense of freedom because governments were only looking out for the needs of the powerful and wealthy, neglecting the common people and alienating them, which furthered problems of inequality even further

Instead, Rousseau argued that the Earth belongs to no one, and therefore “Private Property” does not exist In his Utopia, there would be a new form of government and society, which he talked of in his book ‘The Social Contract’ published in 1762 He wanted a system where governments didn’t only serve the rich, but rather everyone had an equal say and all worked together for the common good He called this the “general will” and the idea behind it was that all citizens would then collaborate and make decisions that would benefit each other, rather than a few select privileged individuals as he claimed with the current system Individual rights were much less important than this common interest, and laws are merely actions of the general will with the end goal of liberty and the equality of all. If we all worked together for a common goal, as he claimed, wealth and resources would be shared much more equally and people wouldn’t be divided by class or status because it would no longer exist. Therefore, everyone would have the same opportunities and rights and if the government decided to take the power from these people, they would have a right to rebel against this system

Another aspect of his Utopia was education Learning based on memorisation and formal instruction he thought was trivial, and was part of society's problems of greed and corruption Alternatively, humans should be allowed to develop at their own pace and be educated in a way that teaches them morality They should be allowed to freely develop their own interests and natural abilities rather than feeling pressure to conform to societal norms Instead of the classes in school taught by a well educated professional, he thought that education should be based on lived experience and character development In fact, any traditions that we had in society in the 18th century would only have been followed if they went hand in hand with our common interests. Authenticity should be foremost, and convention neglected completely.

Whether or not you agree with Rousseau’s stance on society as a whole and his Utopia, it had a huge impact on the world when published and continues to impact the way philosophers think today. His criticism of inequality and the way the poor were treated by the governments influenced movements such as the French Revolution, changing the nation forever. The idea that the government should serve the common good and that all people should be equal is still something that is discussed today.

His ideas around education were also revolutionary, in turn influencing current educational theories surrounding hands-on learning and critical thinking. In an ever changing working environment, these skills are becoming more and more sought after

In conclusion, Rousseau believed that the main source of all the problems we faced in the world was society. When we became more “civilised”, we became more corrupt. His Utopia was one where everyone was equal, where we all work together for the common good, and where education helped people become free-thinking individuals Even though his ideas may be unrealistic or impossible, they still shape the way we think about equality, society and government today

Does

democracy make us virtuous?

By Rania Lwin Karim

The derivation of the word utopia is one with two possible meanings The prex “ u ” can come from the Ancient Greek word “ εὖ” eu, denoting to an imaginary island described in Sir Thomas More's Utopia, 1516, as enjoying perfection in that society Yet it also can come from “ υ ” , a negative prex, meaning something unattainable Thus, is utopia merely an ideal that we must strive towards? Or rather, are there principles of it in real life? Ones enshrined in the notion of democracy, that allow it to manifest in tangible form?

Democracy is paradoxical. Plato once postulated in fourth century B.C.E whether “democracy’s insatiable desire for what it denies as the good is also what destroys it.”(1) It is undeniable that the tensions within this concept are perpetually at war with one another; conicting and antagonistic. Yet, as Alexis de Tocqueville argued, "The health of a democratic society may be measured by the quality of functions performed by private citizens ”(2) Morals underpin democracy Moreover, it can be argued that they legitimise it Democracy is an enormously compelling prospect for human beings because of the potential inherent within it A true dystopian society seems to be one without the principles of democracy These ideals, enshrined with qualities of equality, freedom and justice are incredibly alluring Thus, this essay asserts democracy has the potential to make us virtuous, but only through the system of equality it is founded on

Yet that thesis makes assumptions that require further elaboration It establishes that democracies with the propensity for virtuous societies are not simply the rule of the majority, but rather a more complex model, “with reference to the conditions characteristically obtained under such a system ”(3) In line with

the OED, these democracies that can promote virtue are “ a form of society in which all citizens have equal rights and the views of all are tolerated and respected ” The distinction made between liberal and illiberal democracies is critical in identifying the form of democracy founded on fair morals Illiberal democracies, such as America before the 1965 voting rights act, that do not account for all citizens rights, are not legitimate ways of cultivating virtue and thus will not be considered

Second, the foundations of the argument for virtue, presuppose that democracies are obligated to make us virtuous citizens While certain philosophers’ scepticism ultimately concede that politics cannot produce virtue, this essay argues that morality is inextricably linked with democracy, and they cannot be distinct entities Augustine believed that "Human institutions are awed and cannot bring about true righteousness”(4), however, true righteousness and virtue are not synonymous with each other. The belief that human institutions are fallible, (specifically those of democracy) doesn’t necessarily propagate that these institutions are incapable of promoting virtue. The Aristotelian argument that the purpose of political communities is to cultivate virtue among their citizens is more convincing since it is founded on the idea of a purpose (different to the divine purpose Augustine alludes to) While his ‘polity’ wasn’t an exact democracy, he argues the state should be “ a partnership in virtue”, and this feels applicable to a modern context Democracies have moral obligations, such as their obligations to uphold equality Thus, if democracy is already so deeply rooted in morality, it is logical to conclude that they are obligated and (when put in effect correctly) will help us flourish to become virtuous citizens

Next it is important to consider one of the most eponymous critics of democracy Plato posits that democracy’s egalitarian nature leads to a populist disdain for wisdom, and subsequently he fears of tyranny of the majority He conceded that education develops virtue (such is redolent in his analogy of the cave) and that argument certainly holds in this essay. However, his denigration of the masses and fear of rule by the ‘poor’ seems unconvincing in today’s democracy where far more checks and balances are in place. Bicameral legislation, federalism, protection of rights are all ingrained within our democracy. Arguably, in the contemporary moment, the costs of no democracy is incommensurate with Plato’s fear of ‘bad cupbearers,’ (5) moreover, Plato seems to oppose how to make people virtuous He mocks the playwright Aeschylus’s phrase of “ say whatever comes to our lips now ” , and thus attacks the notion of freedom of speech The suppression of individualism seems to echo that of a totalitarian state In preventing individuals from developing their independent integrity, Plato’s rhetoric thus sties moral development A totalitarian state cannot lead to a virtuous society, and thus the alternative of democracy seems far more promising

In contraposition to Plato's fears that democracy will lead to rule of the ‘uneducated masses’, Mill proposes an alternative solution Perhaps democracy would actually enlighten citizens This argument feels more compelling on several different levels, and seems more pertinent in our contemporary society In On liberty, he states that “The general tendency of things throughout the world is to render mediocrity the ascendant power among mankind. At such a time it is essential that education should be regarded as the means of enabling persons to assert their own individuality”(6) He argues that being an active member in society’s democracy fosters a sense of individual agency, and thus is empowering, propelling people to be more virtuous Furthermore, he strongly advocates that qualities such as judgement, tolerance and empathy are intrinsic to democracy, and all these features perpetuate our virtuosity as a society Also, in suggesting that people transcend mediocrity, it seems an alternative solution to the Nietzchean argument that democracy suppresses excellence This argument seems more realistic and there is empirical evidence that democracies in today’s world, still promote ‘excellent’ citizens And for all citizens, Mill's argument for education via democracy develops moral faculties necessary for making virtuous decisions

To conclude, democracy can make us virtuous If its inherent values are upheld, democracy promotes equality, individual integrity and ultimately strong morality among the people However, as established, democracy is a spectrum It is not fixed but fluid Thus, the key to realising democracy's potential lies in its continual refinement and commitment to its foundational values, ensuring that it remains a system for its citizens that cultivates a society where virtue can thrive

1 Plato, The Republic (Book VIII)

2 deTocqueville, Alexis, DemocracyinAmerica, VolumeII,Part2,Chapter 5

3 "Democracy" Oxford English Dictionary Online, Oxford University Press

4 Augustine of Hippo, The City of God

5. Plato, The Republic (Book VI)

6. Mill, John Stuart, On Liberty

ST p p p g y g pp g y eradicated, sometime in the far future, fits the loose idea of utopia. However, when all these problems are eradicated, what more do we have to work for and strive for, what are our ambitions and goals? If the growth of civilisation was complete and there was no more left to learn, the motivation to go to work and the satisfaction of discovering something new would be non-existent As the supporting character in Scythe, Scythe Curie says ‘In the Ancient times, it was about forging life instead of passing it’, touching upon the boredom felt, when you have achieved everything All these aspects which changed, they are trying to perfect and change the humans, make them almost super humans but as Scythe Curie, points out ‘power comes infected … with the virus of human nature’, meaning that although humans can change their appearance to look younger or older with the press of a button, and their pain nanites will take the pain away, the one thing that can’t change is human nature. The greed for power, the jealousy of those in power, doubt, anger, sadness and boredom, those can never change.

The main protagonist, Citra constantly ponders these questions and only truly finds fulfilment by becoming an apprentice scythe. Scythes, being the only people who can glean/kill permanently and being able to choose who to kill, are entrusted with a lot of power and with power comes corruption and greed. Notice however that instead of being called ‘murderers’ or worse, they are entitled as ‘Scythes’ This is because although people naturally fear a Scythe, they understand their importance in society acting as a sort of human culler, maintaining the population of the world since no one can die permanently unless at the hands of a Scythe Scythes are also supposed to be pure, unbiased and above the law as well as being forbidden to wear black as this cultivates an image of the grim reaper and a harmful death

In the Ancient times, people did fear death, but if you visually see ‘death’ or the people who wield death in everyday life, then that amplifies the fear by a thousand And if you have lived for a thousand years instead of 80, then the thought of the unknown that follows death, scares you more

Now let’s return to the thought that the idea of utopia varies from person to person, so what happens if and when you can’t satisfy or meet everyone’s demands? What happens if someone has an idea of utopia that is harmful to a large group of people or people have directly opposing ideas of utopia? In Scythe, the main antagonist is Scythe Goddard, who abuses his power and kills great masses of people at a time (technically not allowed in Scythe law) and causes terror just because he finds it fun. He then justifies it in his diary, writing ‘in a perfect world, don’t we all have the right to love what we do?’ And to an extent, worryingly, he isn’t wrong

He also states that ‘ we scythes are above the law because we deserve to be’, touching upon the social hierarchy and divide between scythes and everyone else Although some scythes may not want to abuse their power, they still reap the benefits of skipping queues, never having to pay and being gifted extravagant items just because people fear them These benefits remind me of the sacrifices that ancient Greeks and Romans used to make to gods to keep them happy and ‘prevent’ the Gods from harming them, drawing the comparison that the Scythes are like gods. This directly goes against the utopian idea that everyone is equal, as this is simply not possible and there is always going to be someone or some people in a utopian or dystopian society, who hold more power and influence than someone else.

In conclusion, the idea of Scythe is utopian but the reality is dystopian as although what we see on the outside is flashier and more impressive, in terms of human appearance, the inside, the personality and the most important aspect, hasn’t changed. In addition, the power of who gets to kill, is distributed and executed unevenly and unfairly This power grants Scythes advantages such as never having to pay, just because people fear them and have been living with this overwhelming fear when seeing a Scythe since they were young Finally, the idea of utopia never works because everyone is different and will have different thoughts on what utopia is

The Chasing of Unrealistic Utopias: Animal Farm by Maya Erkman

On the surface, Orwell’s Animal Farm appears to be a short fable about animals revolting against their corrupt human master’s and establishing their own society However, beneath this ostensible plot lies a cautionary message warning against false saviours, exploitation and the dangers of utopian thinking which can rapidly descend into a dystopia. Though Orwell clearly anthropomorphised the characters to parallel the rise of Stalin in 20th century Russia, the themes present are still applicable in numerous contexts.

It is Old Major’s dream of a perfect farm run by animals and free from human oppression which inspires the rest of the animals to overthrow Farmer Jones. Initially they appear to have formed a perfect, utopian society. The idea of a utopian society incorporates the promotion of certain values through presenting them in an ideal society. In the case of Animal Farm, the chief value is equality, empathised in the motto of

“All animals are equal ”However, the subsequent fall of the farm into tyranny and oppression outlines Orwell’s warnings against foolishly chasing unrealistic utopias because of ‘the betrayal of liberty in the name of “equality” and false fraternity of collectivism’, that the influential minority, the pigs, imposed on the rest of the animals

The descent into a dystopian society is gradual The original utopia is defined by seven commandments collectively formed and benefiting all in the farm It is the idealistic Old Major who formulated these commandments and although his intentions were noble, they were unfortunately unrealistic Things take a turn after Old Major’s death which results in a change in leadership and a deterioration of the key principles of the utopian society

One of the themes most prevalent throughout the novel is the pigs’ manipulation which leads to the indoctrination of the other animals It is clear throughout that the pigs are the most intelligent creatures in Animal Farm. Napoleon and Snowball are shown to be charismatic leaders with strong opinions and a thirst for power and even the subordinate pigs have their own areas of cunning like Squealer’s talent for propaganda The reason why the pigs’ manipulation is so effective is due to the other animal’s gullibility and lack of teaching They very easily give blind trust to the pigs which results in a dichotomy between pigs as protectors and human beings as tyrants causing the inability of animals to realise the extent of their suffering under the leadership of the pigs This trust enables the pigs to control the meaning of words such as, ‘freedom’ and ‘equality’ and shape these terms to fit their agenda.

Fear is another tool the pigs utilise to their advantage The pigs constantly threaten a worse alternative to their regime, this being Jones’ return to the farm, to get away with their corrupt practices. This officially begins with the disappearance of milk and apples and it is later revealed that these resources are to only be distributed amongst the pigs. The use of terror becomes more explicit when Napoleon forcefully exiles his political rival, Snowball, by sending a pack of hounds to chase him away Once Snowball has been disposed of, he becomes the scapegoat for all that goes wrong on the farm which allowed Napoleon to dispel blame away from himself

Despite the utopian society being jeopardised at this point, the rest of the animals are blind to the ongoing corruption However, when commandments which were written down are blatantly broken, unease begins to spread amongst the animals Before when the pigs went against Old Major’s ideas, Squealer would challenge what the animals had remembered him saying Yet once written rules were disregarded, it became clear that the changes being made were for the worse of the animals' benefit

The plot reaches its climax when the pigs begin to emulate their previous oppressors, the humans This is marked by the horrifying scene of the pigs walking on their hind legs exemplified by the new maxim “four legs good, two legs better ” A cycle of oppression had ensued and the utopia which the animals had helped to create descended into a tyrannous dystopia. In the final scene it became impossible to differentiate pig from human marking the completion of this cycle.

The Life of: John Stuart Mill (the Dystopian Coiner) by

Emma Chen

Dystopia: There’s no arguing about it You’ve at least heard of the term, or, more likely, even seen it for yourself The Hunger Games, The Handmaid’s Tale and Animal Farm all being extremely infamous examples of dystopian fiction It’s the anti-utopia that just so happens to have more in common than utopian ideology one would think, not only in the media nowadays, but also in their history This article delves into the coiner of the term ‘dystopia’, as well as the topics surrounding.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) was not only a past member of parliament, but a political economist, civil servant and philosopher, paving the way for ideas such as liberal socialism and women's rights As a child, Mill was born to be the child prodigy of London Son of James Mill a Scottish philosopher, historian and economist, and Harriet Barrow, he was taught by his father and friends, and rather than any traditional schooling he learnt Greek at the age of three and Latin at the age of eight It was an ‘extremely rigorous’ upbringing, James had high expectations of the boy, shielding him from others his age, aiming for him to become a genius.

Mill would go on to note his remarkably harsh education in his Autobiography for in his early teenage years, he had already learnt the classical canon, algebra, the historical works of England and Scotland and much, much more, going on to study politics, logic and calculus He was steadfast in his academics his entire life, and was the tutor of his younger siblings So much so focused, that it manifested into a ‘mental crisis’

“Suppose that all your objects in life were realised; … would this be a great joy and happiness to you?” And an irrepressible self-consciousness distinctly answered, “No!”

So, how did he recover? Although Mill’s restlessness occurred somewhat infrequently during later periods of life, he eventually found inspiration within the writings of thinkers from a wide variety of intellectual traditions to name a few, Thomas Carlyle, Herbert Spencer, Frederick Maurice, and his eventual wife, Harriet Taylor Mill worked as chief examiner of the East India Company until his retirement, where he was recruited as a MP for a term He died at Avignon, France, where he muttered his last words to his daughter, Helen Taylor:

“You know that I have done my work ”

Utilitarianism is one of Mill’s most promoted philosophies, debatably founded by English jurist Jeremy Bentham. Ironically, it relates much to the ideals in utopia. As a branch of ethical philosophy and consequentialism, utilitarianism strives to achieve the highest good for the largest number of people a common approach to moral reasoning In today's society, we often use this philosophy for business (due to the accounting of costs and benefits) and war

And yet, utilitarianism holds a few issues of its own First and foremost, there comes the point of human error We, ourselves, hold limited information as to what a single action can bring for the future The second point is that utilitarianism does not necessarily apply to justice and individual rights Say that two people need a cup of water each, and the other has two cups of water. Using this philosophy, both people

would get the cup of water which leaves the other with none and in more extreme cases, this could be a life or death scenario for the one man, which would not be equitable in most circumstances

This may be linked back to the relations of utopia and dystopia, where the middle ground is blurred, such as in utilitarianism That is not to say that the philosophy in itself is ‘bad’, there is no ‘bad’ philosophy merely that it is flawed The most effective factor in Mill’s thinking is that it provides us a clear path to determine action in the terms of utility.

Liberal Socialism is a political philosophy (and it is here that I point out that ‘philosophy’ quite literally displays all that invokes thought and study due to their ‘love of wisdom’). The definition is both simple yet complex, it is a term that combines liberalism and socialism, however, historically, the idea of socialism was essentially built to oppose liberalism

Classical Socialism seeks to create a society through economic equality and collective welfare It was a response to the inequalities formed by the Industrial Revolution, famously, when Karl Marx, a famous early socialist, published The Communist Manifesto in 1848 alongside Friedrich Engels Examples of socialist countries include Vietnam or Sri Lanka, meanwhile, some countries have ‘socialist constitutions’ such as India and Portugal.

Classical Liberalism is heavily influenced by the Enlightenment era, with thinkers such as John Locke and Adam Smith This comes with limited government, individual freedom and a free market economy which, simply speaking, is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by unrestricted competition, without significant government intervention

The harm principle was created by none other than Mill, saying that people should be free to act however they wish, unless causing harm. This is one of the main reasons that philosophers tend to view him as a liberal. We see a great sense of ethics in Mill, from utilitarianism to the harm principle, but ethics barely need the law to exist As a feminist, Mill also argues that all should be able to pursue what they see fit, priding individuality above all He gave many influential arguments across his time, dedicating many to free speech and personal autonomy so much so that Herbert Marcuse, a German-American philosopher and social critic dismissed him as one who holds ‘elitist’ opinions But, we ourselves can not dismiss the most important note of Mill’s socialist ideology, within his own Autobiography

Mill writes, “[his] ideal of ultimate improvement went far beyond Democracy, … and under the general designation of Socialists.” He would then go on to publish treatises such as The Principles of Political Economy and Socialism. Nonetheless, it wasn’t a gross pandering to a new audience without any thought, no. During his time in office, he supported taxing wealth in order to reduce inequality, endorsed government-provided education and often used his power as an MP to uplift those in need

Though this is heavily linked to utilitarianism, there’s no denying that he used socialism in his day-to-day life, describing his relationship to it as a ‘North Star’ as even though it can’t be reached, it ought to be used as a navigational guide

Finally, as I’m sure many of you have been patiently waiting for, we come to the Irish Land Question. It not only is associated with socialism, but crucially is the very event that started the word ‘dystopia’

with conditions so horrible that it can be linked to totalitarian societies The name was given in the 19th century to the problem of land ownership and agrarian distress under British rule, taking place just after the Irish Famine (also known as the Great Famine or Potato Famine) In a sense, the two are intertwined, and act similarly to a ‘revolution’ Whilst the Irish Famine was a tragic event of mass starvation, the Irish Land Question was an ongoing struggle for reformation, more specifically for land rights.

John Stuart Mill was highly influential during this period and endorsed the action of peasant property as the most suitable form of land appropriation. This means that peasants may hold title to land outright (fee simple) or by any of several forms of land tenure

During the late 1800s, Mill would continue to spend money ‘lavishly’ to help the people of Ireland vocalising to Britain that they would never be able to pay back the troubles and lives they damaged, even after sending £100,000 For context, many Irish were convinced that the famine was a direct outgrowth of British colonial policies. In support of this contention, they noted that during the famine's worst years, many Anglo-Irish estates continued to export grain and livestock to England.

Yes, dystopian affairs can, and sadly, are happening across the globe. Yes, they were once used to describe the state of panic and anger in Ireland, and yes, Mill was the first man to utter his newfound celebrity in 1868, eleven years before Thomas Edison invented the lightbulb, and one hundred and forty-nine years before the great boom of dystopian fiction

Dystopia: There’s no arguing about it From books to movies to much, much, more it all stems from John Stuart Mill a child prodigy turned empathetic man who shows to be the foundation of much of the modern world.

The Hunger Games: What does this dystopia tell us about society? By Nicole Zabelina

The Hunger Games is probably one of the most famous dystopias, and is very similar with books and films such as Divergent. Below I will analyse some of the similarities between dystopias and what this therefore tells us about our society

Firstly, in both Divergent and The Hunger Games, there is a division in society; in the Hunger Games there are twelve districts, and in the Divergent there are five factions In both of these dystopias, once you are in this district or faction, it is impossible to transition to a different one This tells us that perhaps people do not think that the future will be as hopeful or democratic as believed by the wide public However, if these best-selling books have been written, then is this really what the people of today think or is this what we are told they do? Are we already on our way to making one of these realities become our future?

This is not the only example; in Scythe, The Hunger Games and Divergent, there are large ceremonies that dictate your entire future In The Hunger Games this is to determine whether you compete in the Games (and possibly die), in Scythe if you are an apprentice it is to decide if you will continue as a scythe or get rejected, and in Divergent it is to which faction you will now belong to. In all three of these books there are a series of trials that must be completed to achieve glory, wisdom or success. This suggests that our

society has a need for approval by officials, or people of importance, and that the common concept that “ we shouldn’t rely on what other people think or say because ultimately it is our life” is not used by people This theory draws parallels with social media The whole point of it is to receive approval and praise from others that shape your thoughts about you as a person

It is surprising that most of these ideas start as a glorious utopia where the idea will benefit humanity, but turns out to be something that is rebelled against or is an ultimate failure This theme is consistent in a lot of dystopia and usually ends with everything going back to how it was before, and good triumphing over evil This topic is not common in dystopia alone, but other genres of literature and film as well, which ultimately tells us that we like to be seen as a good, righteous and knowledgeable society that will know what the right thing is to do when all is wrong. But what is the right thing to do? And from whose perspective is the story taken from? Most of the time, the story follows a young person confined to the parameters of that which the regime sets, and rebels against the leadership, ultimately victorious. But surely the older generations will have a better understanding of what is right, because of their experience? If the younger generations have been born and raised in the dystopian society, then how would they know how to think otherwise? This shows that today’s writers are more positive and hopeful than we think when we first discover the plot of the Hunger Games or Scythe

By Amalie Langseth Hughes

Utopia is defined as ‘ an imagined place or state of things in which everything is perfect’ but is this a cop out? Everyone’s utopia will be different as everyone has differing likes and morals Is it possible to promise a utopia when someone's idea of perfection could be a prison for someone else?

There is no developed society in the world that has reached any form of perfection and many argue such a feat isn’t possible Now more than ever we are seeing divergence in ideas of a utopia in one of the strongest countries in the world The USA’s election race has illustrated perfectly that a perfect leader to millions is the equivalent to hell for many others. Donald. J. Trump won the election by a majority and with democracy. Yet following his win there was a large uproar throughout the USA. This shows that even by electing a leader through democracy can create a world that is worse than death to many. The fact alone that there are multiple political parties shows that we all have different versions of utopia How can utopia be feasible when even small countries cannot reach a consensus about their leaders, especially when a utopia requires so many other factors that we must also reach a consensus on Are humans capable of it?

The philosopher Nietzsche once said "People either never dream or dream interestingly", life is like a dream, but whether or not this dream is wonderful needs humans to work on it The Truman show was somewhat critical of real life, the director wanted to use the Utopian happy life in Truman's world to contrast the injustice of modern society For Truman, this world was a dystopia in which he lived under constant surveillance and was traumatised and forced into believing his life was perfect, however the viewers believed the Truman Show was a utopia. This shows the unattainable and dual nature of a utopia as even though the viewers all believed that Truman’s life was a form of utopia, for Truman his life was the ultimate form of hell This illustrates that we cannot even create a fictional form of utopia with a majority were actors because there is no one definition of a utopia

The concept of utopia may be constructive to society as it may give inspiration for improvement, as Utopian thinking can inspire individuals and societies to strive for a more just and harmonious world The notion of a perfect society can serve as a guiding vision which leads to reforms in areas such as the government, environmental sustainability, and human rights However this could be destructive as utopian thinking can be rigid and intolerant especially to those who live contrasting lifestyles and can lead to the elimination of human rights and freedom Utopian visions also fail to account for complex human nature Human beings are diverse, with a range of desires, and values. The assumption that a perfect society can be created by simply aligning systems, values, and institutions under one ideal ignores the complexity and messiness of human nature.

Ultimately the question of whether utopia is a cop-out hinges on how it is used. If utopia becomes a way of avoiding action, or a way to force your singular idea of perfection on the whole it can certainly be seen as a cop-out. However, when approached as an inspiration, an ideal that motivates progress and helps us critique and work on our current systems, the concept of utopia is not a cop-out, but a powerful tool for social and personal transformation In the end, the danger lies in the way we utilise the concept of utopia It shouldn’t be a way to disengage from the complexity of the real world, but rather a way to shine light on how things could be better, urging us to take action and pursue those better possibilities, imperfect though they may be

Zootopia: Utopia?

By Safia Pancholi

The animated film Zootopia is a seemingly vibrant world where animals of all shapes and sizes coexist in a bustling metropolis At first glance, the city seems to embody the principles of a utopian society: diversity, cooperation, and the promise of a better future However, upon closer examination we can see the underlying tensions and philosophical problems that challenge the notion of Zootopia as a true utopia. This article explains the complexities of this animated world, considering philosophical ideologies such as utilitarianism, social contract theory, and the idea of the "noble savage " to assess whether Zootopia represents a genuine utopian vision or merely a veneer of idealism.

Utopia, as originally conceptualised by Sir Thomas More, embodies an ideal society characterised by harmony, equality, and the absence of suffering In Zootopia, the premise of a society where predator and prey can live together peacefully resonates with this ideal The film’s protagonist, Judy Hopps, embodies the spirit of progressivism, breaking free from societal constraints to become the first rabbit police officer Her journey is a testament to the potential for individual achievement within a seemingly equitable society. Yet, this ideal is complicated by the realities that Judy and her fox partner, Nick Wilde, encounter. Systemic discrimination against certain species and the rise of fear-based politics challenge the superficial harmony of Zootopia. The fear of predators has been ingrained in society, showing how societal narratives reflect underlying biases that can lead to harmful stereotypes Here, we see parallels to another fictional animal society, where Orwell’s prescient pigs conclude that “all animals are equal, but some are more equal than others” We have to ask- does the film’s society genuinely embody utopian principles or does it merely offer a comforting narrative to gloss over the inevitability of societal inequalities?

While Zootopia presents a city where “anyone can be anything,” the reality is far more complicated The film positions itself as a post racial utopia, suggesting that it transcends the divisions of predator and prey However, as Judy navigates her new role, she uncovers systemic injustices that challenge this ideal Predators are marginalised, deemed untrustworthy, and victims of scapegoating in the face of a mysterious disappearance crisis This narrative raises profound questions about the nature of societal harmony: can it truly exist if it is built on the oppression of others? The film illustrates that the assumptions made about others can be detrimental to social cohesion, reflecting real-world dynamics of prejudice and fear.

Utilitarianism, as explained by thinkers like Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, posits that the best action maximises overall happiness In Zootopia, the societal structure strives for the greatest good for the greatest number. The inhabitants enjoy a high standard of living and vibrant social life. However, this apparent harmony is compromised by the manipulation of public perception and the scapegoating of predators. The fear that arises from the missing mammals mirrors real-world issues of social panic and prejudice, suggesting that a society can achieve superficial peace while enforcing narratives that serve the majority at the expense of the minority If the happiness of the many relies on the suffering of the few, can such a society truly be considered utopian?

The concept of the social contract, as discussed by philosophers like Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, offers another lens through which to view Zootopia According to social contract theory, individuals consent to form societies and accept limitations on their freedoms in exchange for security and order Yet, Zootopia illustrates a breakdown of this contract for its predator population, who face discrimination despite their contributions This unequal treatment highlights a fundamental issue: the assumption that all members have equal stakes and opportunities In Zootopia, the social contract skews toward herbivores, creating a hostile environment for predators. The social fabric of Zootopia does not accommodate all its inhabitants equally, suggesting that a true utopia must ensure that all voices are heard and that no group is relegated to a status of “other.”

The idea of the "noble savage, " popularised by Rousseau, posits that humanity is at its best in a state of nature, free from civilization's corrupting influences. Zootopia plays with this concept, particularly regarding predators, initially portrayed as dangerous yet eventually revealed to possess complexities and moral agency. However, societal pressures that lead to the resurgence of primal instincts among predators- exacerbated by fear and political manipulation- raise questions about civilization itself Is Zootopia a utopia, or does it expose the fragility of civility when faced with prejudice? The film’s conclusion, with Judy and Nick advocating for understanding and cooperation, suggests that the path to utopia is fraught with challenges requiring constant vigilance against societal regression Understanding and empathy are essential to overcoming the fear that divides us

Ultimately, Zootopia may seem like an innocent Disney film, but it conveys deep messages about the complexities of achieving a utopian society Beneath its colourful world where diversity is celebrated and dreams are pursued, the movie reveals the cracks in this ideal through themes of systemic bias, inequality, and the fragility of social harmony Zootopia suggests that true utopia isn’t a static end state but rather a continuous journey toward justice and equity. Through its story, the film invites us to reflect on our world, encouraging us to envision a society that transcends prejudice and embraces the diversity of our shared humanity.

Utopias to Dystopias: Literature’s Switch to a Darker Future by Victoria Artemeva

Literature has long reflected on the anxieties and hopes of the society in which it was written, so, if this is true, why has literature taken a dark turn from mostly utopias to dystopias, and what does this say about society’s mindset for the future?

This article will analyse the historic shift of literature from utopian to dystopian literature, explaining many of the factors behind this shift. For clarification, a ‘utopia’, as used in this article, is defined as ‘ an imaginary place or society in which everything is perfect’. Literally translated from Greek, it means ‘ no place’. A dystopia is defined as ‘ an imagined state or society in which there is great suffering or injustice, typically one that is totalitarian or post-apocalyptic’ It is also often a social commentary about societal issues

The early modern period is commonly considered as the historical period that lasted from the 16th century to the early 19th century This time was alive with post-renaissance scientific discovery, enlightenment ideals and hope for the future Thomas More’s Utopia coined the term in his book ‘Utopia’ and depicted a seemingly ideal society. Published in 1516, it paved a path for further utopian ideologies. In this society, money doesn’t exist, creating a seemingly classless society, and there is abundant food, water and resources for everyone. No-one experiences poverty, there is no greed, little crime or immoral behaviour, and little war. There are, however, slaves, who don’t get freedom, but they have their basic needs fulfilled This seems, to the average person, as a near perfect society, an ideal Utopia, it is an imaginary place which has little to no problems for the average citizen

Other utopian works produced during this time include Sir Francis Bacon’s new Atlantis, published in 1626, it details a perfect land in which Bacon’s main focus is on education The commonly held beliefs of the people are said to be "generosity and enlightenment, dignity and splendour, piety and public spirit". Discovery and knowledge are central to the story, and Salomon’s house of knowledge, located in the mythical town of Bensalem in the story, is considered a perfect college.

Additionally, The City of the Sun by Tommaso Campanella (a book about a utopian city with a focus on education and order, which is governed by philosopher-priests) and The blazing world (which has a focus on technological advancement and education) are also both utopian works produced in the early modern period

From all of these utopias, we can see that people in the early modern period were optimistic about the future and believed that morality, rational governance and a strong enforcement of the law and rules of the place would lead to a utopian society.

During the 20th century, people began to be less optimistic about the future Idealist visions of the past gave way to totalitarian regimes such as the Soviet Union - which aimed to create a society without classes where all were equal, based on Marxist principles - but which eventually crumbled to a highly authoritarian state, and Nazi Germany, which was thought to be an ‘ideal’ society at its founding by some, but soon became a brutal totalitarian state The worries about extreme surveillance and government control over the people in both of these examples began to become common anxieties of the people The horrors of the world wars also influenced people’s collective mindset to shift towards a darker, more pessimistic future, and the Great Depression shattered the belief in a perfect utopian society.

In the rise of this pessimism about the future and disbelief in perfect societies, literature now began to depict times when attempts at Utopian societies went wrong; when they became dystopias

Some popular examples of these kind of societies include:

● 1984 by George Orwell. 1984 is set in a highly totalitarian state called Oceania. It is constantly at war with other nations and has full control over the public’s opinions and the media. A fictional character called ‘Big brother’ watches over the people, showing how there is constant surveillance. It raises concerns about the people’s loss of freedom, and the government’s complete control over them.

● Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury The society in Fahrenheit 451 is one in which all the people live in fear, and books are the one most illegal thing which must be burnt or destroyed. It highlights themes such as the public’s loss of critical thinking, censorship, and the control of the government over the people

To summarise, In the 20th century, people began to be less optimistic about the future due to the rise of totalitarian regimes, the Great Depression, and both world wars They began to think that the utopian societies of the past would cause ruthless, authoritarian governments, and their main concerns were surveillance, societal control, and people’s loss of freedom.

Modern dystopian literature often deals with themes such as the climate crisis, people’s dependence on technology, and similarly to past worries, societal control. This may be due to the prominence of technology in the world, with it being central to many of our lives and rising addiction to technology, climate change and environmental degradation, political propaganda and the fact that some anxieties from the past generation are still present

Some examples of modern dystopian literature include: The hunger games by Suzanne Collins, which raises concerns about the control of the government over all people, the people in the capitol's loss of critical thinking and surveillance. The Maze Runner by James Dashner, which has central themes such as environmental collapse and societal control. And lastly, Ready Player One by Ernest Cline, which emphasises people’s dependence on technology, climate issues and corporate power.

So, today’s stories are mostly dystopian, and centred around concerns about environmental collapse, societal control and a host of other concerns, due to our current global problems, but it can also serve as a warning for what may come if we neglect societal issues such as the climate crisis

But is there still a place for utopias in this world? Since the early modern period, there have been few utopias written, and most recently, utopian novels such as ‘A modern Utopia’ by H.G. Wells, published in 1905, which has continuous improvement of the social and technological systems and a world state owns all power sources and land, and potentially ‘brave new world’ by Aldous Huxley, which although many could argue is dystopian, can also be utopian, as it is a society, called the world state, that is based on science and efficiency, and emotions and individuality are eliminated

Therefore, due to the widespread switch to dystopias, not many utopias have been written, however, it is possible that with the creation of sustainable cities in the world, and better societies people may become more optimistic about the future and more utopias may be written

To conclude, literature reflects on the mindsets of society at certain times During the early modern period, many people wrote utopias, hoping for the creation of a better future, but following the horrors of the world wars, and seeing utopian societies crumble into dystopian realities, many people’s mindsets shifted towards a more dystopian future

Now is my question to you, reader: How do themes in literature, both utopian or dystopian, compare with your personal view of the future?

1984 - Orwell’s Realistic Dystopia by Aurore Lebrun

George Orwell’s seminal novel 1984 explores a dystopian world, in which we are constantly watched and examined This presence is named ‘Big Brother’ and serves as a ‘higher-power’ throughout the book Although this concept may seem alien, it has infiltrated large parts of our modern society From TV shows to CCTV to facial recognition systems, many have started to fear that a dystopian concept is so near to our daily lives

The TV show ‘Big Brother’ was created in 2000, becoming the first reality TV show to watch its participants for all 24 hours of the day. Obviously, this created a large amount of interest, as most viewers found it unnatural to follow individuals for the entirety of a day. Nevertheless, the show was a hit as there was a lot of intrigue over how much privacy a person was attributed to; there was stark fascination over what people did and how they reacted to one another The program let its competitors live in a cramped area where cameras watched every encounter, every emotion, and every small movement they made Big Brother, in many respects, elevated human behaviour to a spectacle, allowing viewers to examine everything from the ordinary to the spectacular Audiences couldn't help but wonder how participants would act in similar situations, with no privacy and no way out of continual scrutiny, as they negotiated everyday obstacles, forged alliances, and occasionally clashed in heated confrontations.

This dystopia is henceforth continued from the rise of CCTV, as individuals are filmed doing the most basic of daily actions In the book, CCTV is used to control and analyse the actions of the civilians Although today, CCTV is primarily used for safety reasons and to watch for crime However, some argue that the simple fact we are filmed and watched is a violation of privacy Even if we have nothing to hide, the awareness that we are constantly being watched can make us feel anxious and uneasy A "chilling effect," in which people start to self-censor their behaviour, refrain from particular activities, and adjust to social norms in order to keep from drawing notice from authorities, might result from the erosion of privacy. For example, in China, the government has instituted a "social credit" system in which people are watched for social behaviour, such as how they interact with others or if they follow traffic laws, along with criminal activity Individuals are rewarded or punished based on this information, fostering a culture that encourages constant adherence to state-approved conduct A terrifying image of the future that was hinted at decades ago in 1984 is a possibility that our thoughts, movements, and acts may be tracked, examined, and used against us

The argument of CCTV is taken one step further with the creation of facial recognition, identifying individuals in the street Facial recognition systems have become a key part of the so-called "smart city" initiatives, where surveillance infrastructure is deeply integrated into urban environments In cities like London, New York, and Beijing, high-definition cameras equipped with facial recognition can identify people within seconds of them appearing in public, and match their faces to vast databases containing millions of records This allows for police forces and government agencies to identify criminals and deliver justice. Conspiracy theorists would argue that it is for the government to watch and keep tabs on us. What the two arguments have in common, is that this concept would have seemed extremely alien and abstract to anyone 50 years ago. A number of cities in the US and Europe have outlawed or strictly restricted the use of facial recognition technology in public areas because of concerns about overreach and accountability issues According to civil liberties organisations, facial recognition technology may be used to violate people's freedom of speech and privacy There is a serious risk of misuse if facial recognition technology becomes widely used

In conclusion, the dystopian world of perpetual surveillance portrayed in Orwell's 1984 seems more and more true in today's world due to the development of reality TV, CCTV, and facial recognition technology. These technologies raise questions about individual freedom and the possibility of abuse by obfuscating the boundaries between privacy and safety. We must learn to consider how to strike a balance between security and autonomy as monitoring techniques proliferate, as our world could be seen to take on a dystopian reality.

The Dichotomy of Utopia: Balancing Aspirations Against Realities by Nina Freudenheim

Dystopian novels have been a feature of contemporary reading culture for as long as I can remember. Articles in this edition have explored The Hunger Games, Maze Runner and Fahrenheit 51 but other examples include Lord of the Flies and Noughts and Crosses While readers see the societies which feature in these books as distinctly undemocratic, authoritarian and even nightmarish, to the villains within the novels, their society is no dystopia – it is the opposite While it is hard to understand this perspective, perhaps the contradictory views of a society come about because in reality it is difficult to determine when utopian visions are warped to become perfect only for a minority, rather than a majority

This distortion of utopias will occur far more easily than one would expect It happens in part because the pursuit of a perfect society inherently involves imposing certain ideals on others Perfection is not achieved through people having the freedom to do all they choose, on the contrary this would lead to such immense amounts of chaos, that a society might descend to the basest levels. Thus, even the best societies would seemingly require control and if the ideal is what a government is trying to achieve, then a more rigid enforcement of policies might be required to impose this, as the highest standard is expected. One example of this is in The Handmaid’s Tale where the male regime in their quest for a utopian society creates a dystopia for women – with all women being assigned specific, limiting roles which result in dehumanisation

Another fundamental issue of utopias is that they’re based on only one group’s perception of what perfect is,as the conventions which make up someone’s ideal society will vary and therefore the concept of utopia is subjective This leads to societies rife with conflict as an elite group dictate their understanding of what’s best on others – who will resent the neglecting of their own ideas of the ideal This group, propelled by resentment, are then likely to challenge those in authority, distancing the society further from any form of utopia This vicious cycle is strikingly similar to Karl Marx’s theory which argues a capitalist system contains the seeds of its own destruction.

Despite the issues which appear intrinsic within the concept of utopia, it remains important to aspire towards perfection as they function as a guiding vision and offer hope Striving for a utopia pushes society to address what is imperfect in their current states and reflect on what principles and moral values need to be improved. Regardless of whether a complete state of utopia is attainable, gradual steps towards it, aimed at bettering humanity and social, political or economic structures, makes the world more equitable. Belief in utopias also implies belief in humanity’s capacity to develop. In essence, even if utopias are only an idea, they’re one worth keeping in mind This is a view shared by many optimists and Oscar Wilde epitomises it in the following quote:

“a map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realisation of utopias.”

To conclude, while utopias seem impossible to reach in reality, as an idea they are representative of humans’ tendency to dream and are a driving force which encourages societal improvement Setting great expectations also ensures that even if these aren’t met exactly, something will undoubtedly be accomplished – as Norman Vincent Peale wrote ‘reach for the moon Even if you miss, you’ll land among the stars’

Are Utopian Visions Inherently Authoritarian? By

Antara Martins

The concept of utopia, a perfect society free from suffering and injustice, has been a guiding star for philosophers, revolutionaries, and dreamers for centuries Yet, beneath the guise of its alluring promise, a darker question comes to light: does the pursuit of utopia lead to authoritarianism? This peculiar paradox may reveal that in striving for the ideals of harmony and equality, rigid systems of control are demanded, eroding the very freedoms they claim to uphold

Utopian visions are typically characterised by their pursuit of a singular ideal be it universal equality, absolute happiness, or a perfect balance with nature The foundational problem lies in defining this ideal Who determines what constitutes perfection? And how do they ensure compliance? The inherent diversity of human values and desires often means that achieving a utopia for one group may impose dystopia on another.

Philosopher Isaiah Berlin argued that the imposition of a single, ultimate good often sacrifices the pluralism that defines a free society For example, the Marxist utopia envisioned by Karl Marx, aiming for a classless society, was interpreted by regimes such as Stalin’s Soviet Union as requiring stringent controls on speech, thought, and individual initiative. Similarly, the "utopia" of Nazi Germany, predicated on racial purity, demanded horrific acts of genocide and violence. In both cases, the pursuit of an ideal became justification for authoritarian means.

In fact, the very nature of utopia implies a tension between order and freedom Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), a seminal work in the genre, describes a society of shared property, rigid social roles, and strict laws an environment where individual autonomy is heavily curtailed to maintain collective harmony Even the most benevolent utopian visions often necessitate surveillance, suppression of dissent, or other mechanisms to align human behaviour with the ideal

Michel Foucault’s critique of modern power structures offers an insightful lens here He suggested that utopias often rely on what he termed “disciplinary power” systems that normalise behaviour through surveillance and regulation In attempting to perfect society, utopias inevitably create hierarchies of control, with certain individuals or institutions empowered to enforce the collective vision. This dynamic can spiral into authoritarianism, as the pursuit of harmony overrides respect for individual autonomy.

A further complication, perhaps, is human nature itself. Philosophers like Thomas Hobbes have argued that humans are driven by self-interest and conflict, making utopia inherently unattainable without coercion From this perspective, utopia’s promise of universal agreement and cooperation is a fantasy achievable only by suppressing natural tendencies toward dissent and difference

On the other hand, Rousseau’s notion of the "general will" suggests that utopia could arise from aligning society with the collective good Yet even here, enforcing the "general will" often results in marginalising minority perspectives, as seen in the French Revolution's Reign of Terror, where dissenters to the revolutionary vision were executed in the name of equality and liberty

Contemporary utopian projects, particularly those tied to technology or environmentalism, reflect similar challenges Tech-driven utopias like those envisioned by transhumanists or Silicon Valley optimists promise a world where AI and biotechnology eliminate suffering and extend human potential. But these visions often come with authoritarian undercurrents: who decides which enhancements are necessary? Who controls the data, the algorithms, or the definition of “improvement”?

Similarly, environmental utopias, while laudable in their aims, can veer into authoritarianism when attempting to impose strict limits on behaviour for the sake of sustainability. Consider proposals for “carbon rationing” or enforced population control both measures that could curb freedoms in the name of ecological harmony.

Does this mean all utopias are doomed to authoritarianism? Not necessarily. Some philosophers argue for "negative utopias" societies focused not on prescribing perfection but on minimising suffering and injustice. John Rawls’ Theory of Justice offers a framework for a more modest vision of societal improvement, grounded in fairness and respect for individual rights Such approaches recognize that perfection is unattainable and that diversity of thought and experience is essential to human flourishing

Ultimately, the danger lies not in dreaming of a better world but in believing that any single vision of it can justify the suppression of others Utopia, like fire, can be a source of inspiration or destruction The challenge is to navigate its promise without succumbing to its authoritarian pitfalls, embracing imperfection as the price of freedom