6 minute read

More than a Game

One of the most storied rivalries in the history of Washington, D.C. interscholastic football occurred in the 1940s when the Eagles of Gonzaga twice faced the mighty barnstorming Boys Town team from Omaha, Nebraska. Boys Town, an orphanage founded by the legendary Father Edward J. Flanagan, had only a few years before been the subject of a feature fi lm starring Spencer Tracy and Mickey Rooney. In the following article, Gonzaga alumnus and award-winning documentarian Luis Blandon ’81 recounts the highlights of two epic games—the impact of which went well beyond the gridiron.

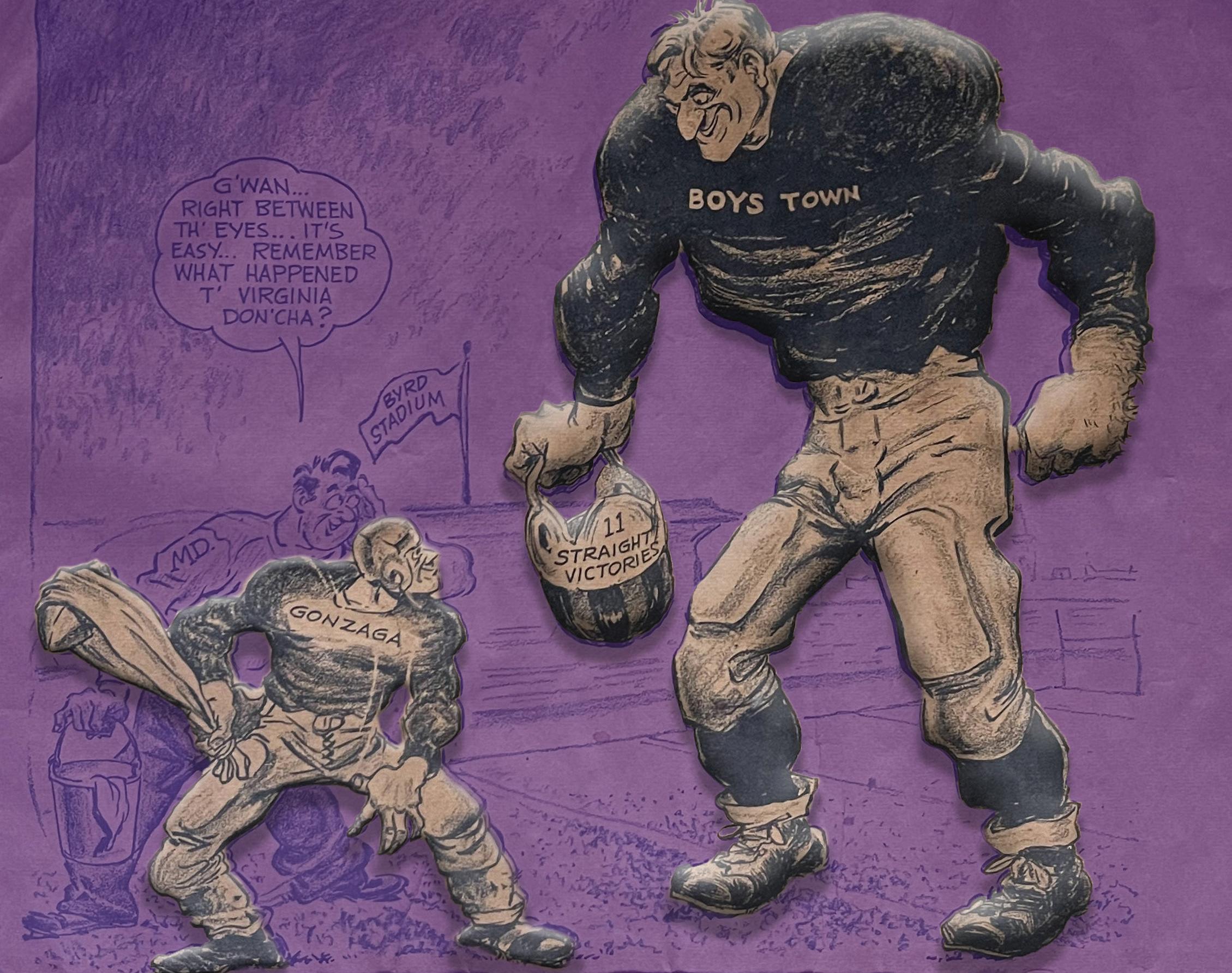

A photo of the Gonzaga Boys Town game from the 1946 Aetonian.

On Sunday, November 7, 1943 as World War II raged, Gonzaga students arrived at Griffi th Stadium by foot, car, trolley, and bus, clad in clothing that made them look like younger versions of their fathers. Unsure of where they would be in a year, they fi led into Griffi th to cheer on their beloved Eagles. Hype had been building since the October game announcement with outlets like the Washington Post publishing such hyperbole as “…the greatest schoolboys intersectional football treat in District history has been booked into Griffi th Stadium.” Gonzaga was playing the celebrated Father Flanagan’s Boys Town of Nebraska. Founded in 1917 in Omaha, Nebraska by a young Irish priest named Father Edward J. Flanagan, Father Flanagan’s Home for Boys was an orphanage and school that welcomed all boys, regardless of their race or religion. The game in November 1943 was the culmination of several days of fundraising by Father Flanagan, including speeches at the Touchdown Club and Uptown Theatre, and visits with General John J. Pershing and wounded soldiers at Walter Reed Hospital. Dignitaries such as Eleanor Roosevelt were in the stands along with several former Gonzaga athletes. As Boys Town was being feted by politicians, Gonzaga’s motto, according to an article in the Washington Post, was “We concede Boys Town the edge in publicity, but we’ll try for touchdowns.” The star for Boys Town, which held secret three-hour practices at Griffi th in the lead-up to the game, was African-American player Clarence Adams, celebrated as one of the best players in the Midwest. The game would mark one of the fi rst integrated high school competitions in segregated Washington—a fact largely ignored by the local press. To prepare for the game, Gonzaga’s Coach Samuel (“Bo”) Richards led practices at the Eagles’ athletic fi eld at 34th and Benning Road, NE. Richards planned to use, according to an article in the Post, “the triple threat brilliance of Angelo Zanger and its defense behind two of the District’s fi nest schoolboy guards in years, Jim Nalls and Tony Museline.” Before a rambunctious crowd of 12,000, Gonzaga jumped to a fi rst quarter lead. Recovering a fumble at midfi eld, Gonzaga drove as, according to The Evening Star, “Zanger, [Bill] Murphy and [Joe] Hickson shared the ground-gaining labors of that hike.” The Eagles scored when Hickson “smashed through the marker” for two yards for a 6-0 lead. Boys Town took the kickoff to their 30. “After passes, runs and bucks, slashing advances off a skilled T-formation attack,” quarterback Dickie Thomas connected with Leo Virgil for a 20-yard touchdown that, the Washington Post said, “caught the Eagles fl atfooted.” Boys Town missed the extra point as the fi rst quarter ended in a tie. Five minutes into the third, Boys Town scored a touchdown, shifting the momentum in their direction. Gonzaga threatened late in the third but fumbled. With four minutes left in the game, the Eagles drove with a combination of runs by Zanger and Hickson but were stalled at the Boys Town 25. According to an article in the Washington Times Herald: “Then came the heartbreaker for Gonzaga” on the fourth down when Coakley broke free as Zanger “seeking rescue from defeat by air” threw the ball. Covering Coakley, Adams tipped the pass and the ball bobbled off Coakley’s grasping hands. The game was over.

On November 30, 1945, a rematch was played at the University of Maryland’s Byrd Stadium. This time around, Joe Kozik was the Gonzaga head coach. Famed Washington sportswriter Shirley Povich, using the language of the time, saw an additional importance to the game: “when Father Flanagan’s Boys Town football team opposes Gonzaga …Ken Morris, a colored lad will be the starting fullback for Boys

Town. He’s one of four Negro players with the team.” The other three African-American players were Tom Carrodine, Chester Oden, and Jarrod Williams. Povich wrote that the attitudes towards race and Jim Crow policies permeating the city “threw [Father Flanagan] for a loss down in Magnolia-fringe Washington.” During their 1943 visit to DC, Boys Town unexpectedly learned only white players could stay at the Statler Hotel and had to quickly fi nd accommodations for Clarence Adams with a local family. To prevent a repetition of the 1943 fi asco, Boys Town reached out to Gonzaga’s Reverend Cornelius A. Herlihy, S.J., who arranged housing for Boys Town’s Black players with two Black families. Coming into the rematch, Gonzaga was a four-touchdown underdog. Gonzaga star Pat O’Neill was unavailable due to infl uenza but, according to the Evening Star, “the I Streeters have fi lled the gaps with gallopers who proved their worth.” Another Eagle star, Phil Daly, was also sick but suited up on game day. All Prep tackle Bernie Lavin was suffering from a cold. Quarterback Dick Redmond’s availability was in question due to an injury incurred in a previous game. Despite the injuries and the week’s rainy weather, Kozik was ready. Though absent on the fi eld, O’Neill told the Evening Star what made Gonzaga special: “You always can win a game if you want to badly enough.” His words rang true as the game progressed—with the Eagles pulling off a surprise win in front of 8,000 shivering fans. The scoreless fi rst half was marred by fumbles due to a muddy fi eld. Gonzaga stalwarts Gil Buckingham, Billy De Chard, and Johnny O’Keefe ran behind what the Evening Star described as a “stellar Purple line.” Late in the third quarter, as a result of a poor snap on its own 10 by Boys Town center Chester Oden, halfback Frank Roe fumbled and was taken down by O’Keefe in the end zone for a safety. After the kickoff, Gonzaga methodically went 45 yards down the fi eld via De Chard, Daly, and Buckingham rushes to the Boys Town 10. On a reverse, Buckingham scored and then De Chard connected for the extra point making it 9-0. The Eagles threatened several more times, dominating every element of play. Only once did Boys Town cross midfi eld, on an interception returned from one of Daly’s passes. As the clock wound down, Gonzaga celebrated in avenging its previous loss.

The game represented more than football to Kozik. As a player at Penn State and a coach in DC, Kozik had witnessed the corrosive nature of segregation. The rematch was the fi rst in a series of steps Kozik took to challenge systemic racism in DC high school sports. Six years later, when Gonzaga added African-American sophomore John Gabriel Smith to the 1951 team, local schools refused to schedule Gonzaga. Kozik and Gonzaga decided to cancel games in Washington and took the team on the road. Many years later, in an article in the Washington Post, Kozik’s son, Randy, refl ected that his father “thought an athlete was an athlete regardless of color.” Fighting the entrenched segregation of high school sports in DC remained an uphill battle. However, on that December 1945 evening, Gonzaga took an important step toward winning the war.

Editor’s note: Gonzaga is grateful to Luis Blandon ’81 for the extensive time and research given to this article, and especially for allowing Gonzaga gridiron greats of yesteryear to take a victory lap as the school celebrates its Bicentennial.