4 minute read

Fostering the �es that bind Jennifer Charteris, Angela

Fostering the �es that bind: the challenge of school connectedness during COVID-19

“All these teachers are quiet heroes… there are teachers here [who]… are living in the same situa�on as we are and

Advertisement

they come to work and they get on with it.” Teachers and principals “com[e] to school with a posi�ve focus on their students despite the myriad of problems.”

These words from Carol Mutch’s research a�er the Christchurch Earthquakes illustrate the challenge teachers face in ensuring their students and school community are supported through �mes of crisis.

And it has a been a tough gig over 2020 and 2021 with snap school lock-downs. According to Saavedra (2020) in as early as 28 March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had already caused more than 1.6 billion children and youth to be out of school in 161 countries (almost 80% of the world’s enrolled students). Over 150 countries have closed schools (UNESCO, 2020). These periods of home schooling dispropor�onately affect students and teachers.

School connectedness is vital at this �me. School connectedness can be defined as a sense of belonging and as having a posi�ve rela�onship with suppor�ve adults and peers. There is sustained engagement with learning and the experience of a safe and suppor�ve environment.

Associate Professor Jennifer Charteris

School of Educa�on, University of New England

Dr Angela Page

School of Educa�on, University of Newcastle

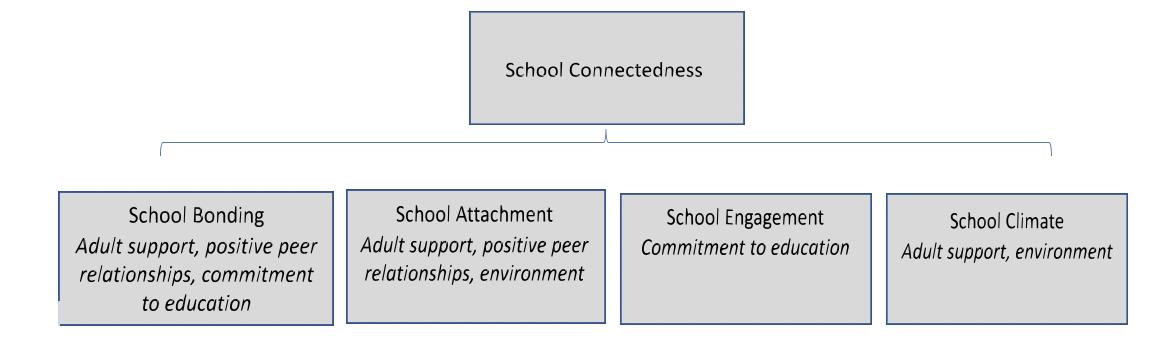

Our research into school connectedness suggests that strong and suppor�ve rela�onships develop through school bonding, school a�achment, school engagement, and school climate. School connectedness can be seen in the rela�onships between teachers, the commitment to students and the all important pastoral support from school leaders. School connectedness can be linked to:

� students’ percep�ons of healthy and posi�ve rela�onships experienced in school; � experiences of care, respect and support; � posi�ve feelings toward school; � a sense of posi�vity about the school as a community (García-Moya et al., 2019). The diagram in Figure 1 has been adapted from research we undertook into fostering school connectedness online for students with diverse learning needs. We illustrate four key domains of the construct of school connectedness: school bonding, school a�achment, school engagement, and school climate.

School bonding is where students feel close to people at their school. They feel connected to school and are happy to be there.

School a�achment is the emo�onal feeling of fondness for school. Students feel accepted and liked by peers and teachers and know they are par�cipa�ng members of the school community.

School engagement is students’ commitment to schooling prac�ces. For example, students a�end school regularly, are punctual, and submit assignments. There is willingness to invest energy into accomplishing challenging skills.

School climate is where students believe that teachers are willing to help them and are suppor�ve. The school is a safe and fair environment.

Teachers in our research found it highly problema�c that students were disconnected from their school-based learning (Page et al., 2021). Some students refused to par�cipate in distance learning or were precluded access due to their home situa�on. These students, who are already at a disadvantaged, were seen to be at risk of slipping even further behind. Recognising that there can be par�cular challenges for students with addi�onal learning needs, we advocate the maintenance of effec�ve communica�on, peer connectedness, and individual educa�onal plans (Page et al., 2021).

We acknowledge that there are teachers doing an amazing job (unsung heroes) at sustaining connectedness in Aotearoa schools. The following are just some reminders to keep in mind.

� Plan for and support peer connectedness. This can involve arranging informal fun ac�vi�es to foster social rela�onships. � Strive to ensure that school rou�nes are sustained at home. (Consistent �metables and the wearing of school uniform.)

Figure 1. Domains of school connectedness. (Adapted from Page et al., 2021)

� Keep in contact with parents where students are reluctant to communicate digitally. � Try to ensure that communica�on is consistent and frequent. � Strive to maintain rela�onships for the well-being of students and teachers. This connec�on can address mental health. (Page et al., 2021). We know that teachers work in school ecosystems and cannot create school connectedness on their own. However, all teachers play an important part in fostering collegiality with colleagues and connec�on with and between students.

References

García-Moya, I., Bunn, F., Jiménez-Iglesias, A., Paniagua, C., & Brooks, F. M. (2019). The conceptualisa�on of school and teacher connectedness in adolescent research: A scoping review of literature. Educa�onal Review, 71(4), 423-444. Mutch, C. (2020). How might research on schools’ responses to earlier crises help us in the COVID-19 recovery process? Set: Research Informa�on for Teachers, 1-8

Page, A., Charteris, J., Anderson, J., & Boyle, C. (2021). Fostering school connectedness online for students with diverse learning needs: inclusive educa�on in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Special Needs Educa�on, 36(1), 142-156. DOI: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1872842 Saavedra, J. (2020). Educa�onal Challenges and Opportuni�es of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. Educa�on for Global Development: A Blog about the Power of Inves�ng in People. h�ps:// blogs.worldbank.org/educa�on/ educa�onal-challenges-andopportuni�es-COVID-19-pandemic UNESCO. (2020). Half of World’s Student Popula�on Not A�ending School: UNESCO Launches Global Coali�on to Accelerate Deployment of Remote Learning Solu�ons. h�ps://en.unesco.