Spring Catalogue 2024

GOW LANGSFORD

25 September19 October 2024

Auckland City

Gow Langsford's annual Spring Catalogue exhibition for 2024 presents a remarkable collection of works by some of Aotearoa New Zealand's most celebrated artists. This exhibition offers a rich cross-section of Aotearoa’s artistic legacy, showcasing prominent pieces by Bill Hammond, Karl Maughan, Gretchen Albrecht, Dame Louise Henderson, Tony Fomison and Toss Woollaston amongst others. Spanning through to the early 21st century, this collection of works offers a captivating journey through the evolution of New Zealand’s visual art, showcasing the depth, diversity, and enduring impact of these revered artists.

Tony Fomison (1939–1990, NZ)

Sea Cavern, 1977 oil on canvas on pinex board inscribed with title and Cat No 190 verso 905 x 600mm 1160 x 855mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, Havelock South; Private collection, Hamilton

Caves and shorelines hold a distinctive place in Tony Fomison’s oeuvre. He was often sick as a child, which led to him developing a meticulous type of drawing. His mother remembers him ‘scribbling away’ in ‘his little cave, his drawing room off the kitchen’.1 He studied sculpture at the School of Fine Arts at Canterbury University, and it was during these early years that he developed his interest in archaeology. After graduating from art school, he worked as an archaeological assistant at the Canterbury Museum and took part in a major survey of Māori rock art, contributing to the archive with drawings, notes and tracings, recording over 300 sites. This focus infiltrated his paintings, which regularly feature rockscapes.

In Sea Cavern the small figure in the foreground stands with its elongated limbs outstretched, seemingly conflicted at the mouth of the rocky sea cavern. Having spent a turbulent three years in Europe and Britain during

the mid-1960s, Fomison returned to Aotearoa in 1967, a victim to a debilitating drug addiction. The small figure struggling against the vast landscape can be seen as an allegory of the outsider, a person who is rejected from society or does not fit in. The figure is removed from locality, amidst a landscape that is impossible to place on a map.

Deep and dimly lit, this painting is typical of the mood that often permeates Fomison’s works. The pared-back colours evoke the clay lustres of cave drawings, as well as the tonal chiaroscuro Renaissance paintings that he would have encountered during his travels in Europe. Fomison’s practice is characterised by repetitions and series, producing allegories that reinterpret the tradition of landscape painting in New Zealand.

The cave can be an allegory for his childhood drawing room, the construction of his identity as an artist, the gallery, the human need for refuge or

a symbol of shelter related to his own personal struggles. Fomison speaks of his time living in a cave sacred to the Kaitahu Māori on Banks Peninsula outside of Christchurch. ‘I knew I was living under this sacred cliff called Rae Kura which means red forehead which is very tapu.’2 It was his way of seeking a genealogy, a loner seeking to re-establish his connection as ‘Pakeha-Māori’. He was taken in by the Kaitahu Māori after being discovered in the cave, and he stated, ‘that’s when I began learning’.3

1. Ian Wedde, “Tracing Tony Fomison,” in Fomison: What shall we tell them, ed. Ian Wedde (Wellington: City Gallery, Wellington, 1994), p.14

2. Wedde, p.36

3. Ibid

Gretchen Albrecht (b. 1943, NZ)

Sky Edge (B), 1973

acrylic on canvas titled, signed and dated Oct ‘73

1510 x 1280mm

1555 x 1325mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, Australia

Gretchen Albrecht is a prominent New Zealand artist renowned for her abstract works, particularly those that explore the relationship between colour, form, and space. Sky Edge (B) is a striking example of the artist’s early exploration of colour fields and minimalism. The start of the 1970s was a time of significant artistic development for Albrecht, as she began to move away from figurative forms and toward an abstracted style that would define much of her later work. During this period, she first began using thinned acrylic paint rather than oil on canvas. This move facilitated greater experimentations with pigment, most specifically its absorption into raw fabric. Sky Edge (B) captures Albrecht’s use of this technique, materialising in a composition that evokes the vastness of a natural landscape whilst simultaneously blurring the boundaries of abstraction.

Sky Edge (B) features bands of colour that seem to flow seamlessly into one another. The dominant blues and purples are reminiscent of the sky at twilight, with the shifts in tone creating

depth and movement. The composition is suggestive of a horizon line, dividing the earth and sky. The edges of the colours bleed into one another, creating a sense of fluidity and organic transition. Albrecht’s work is often associated with the colour field movement, drawing comparisons to artists like Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman. Her connection to the New Zealand environment sets her apart, infusing her work with a distinct sense of place. This painting is a testament to Gretchen Albrecht’s ability to convey complex emotional and atmospheric conditions through abstract means. The work is a powerful example of this period in her career, providing insight into the development of her unique artistic voice. Through her exploration of colour and form, Albrecht captures the essence of the landscape, creating a visual experience that is at once meditative and evocative.

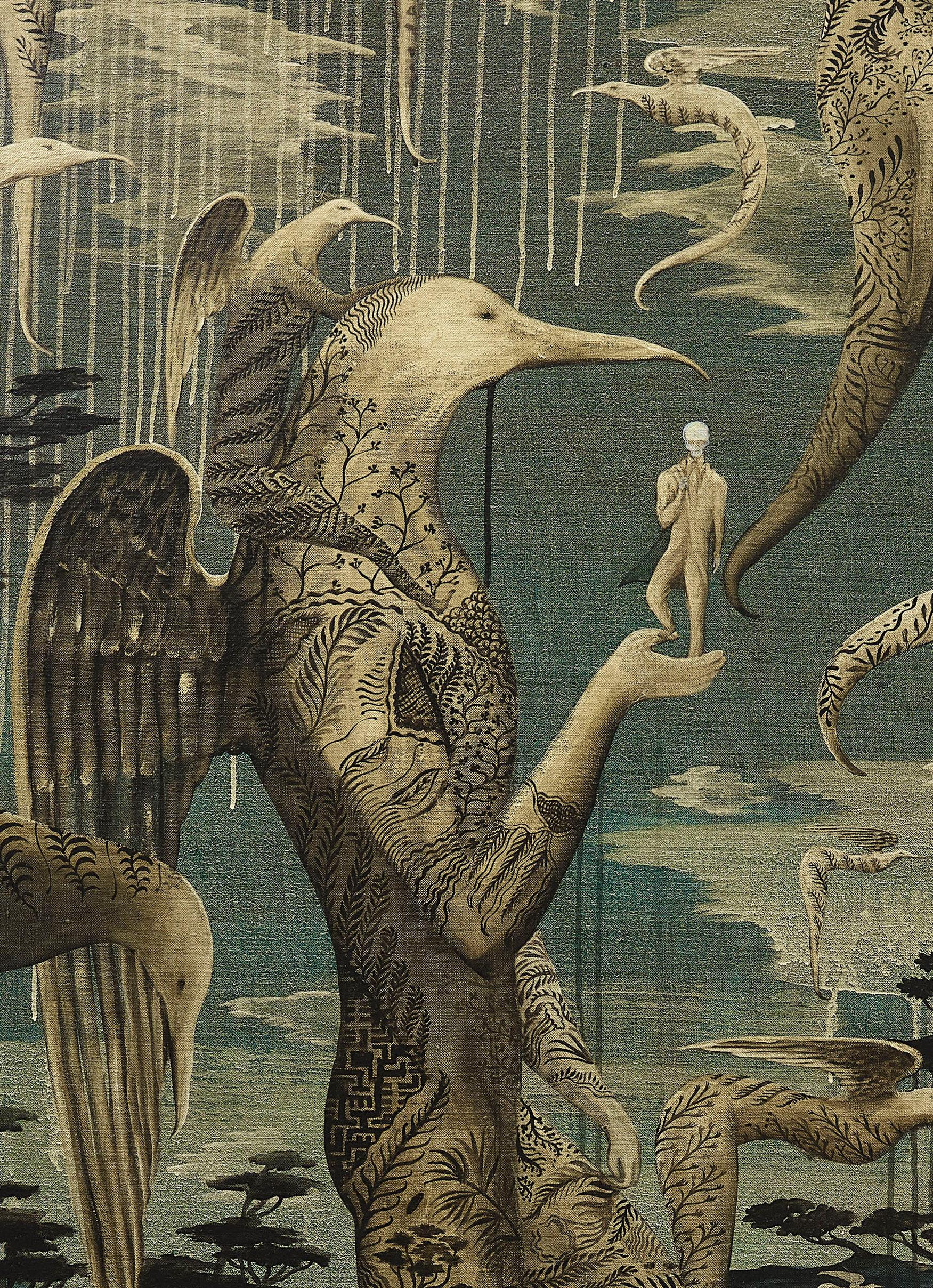

Bill Hammond (1947–2021, NZ)

Unknown European Artist, 2004 acrylic on canvas titled lower left, signed and dated lower right 2000 x 1200mm 2030 x 1285mm framed

Provenance

Purchased from its original exhibition at The Brooke Gifford Gallery, Ōtautahi Christchurch, 2004; Private collection, Picton; Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

Exhibited

Bill Hammond: Paintings, The Brooke Gifford Gallery, 2004

Bill Hammond: Jingle Jangle Morning, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu and City Gallery Wellington, 2007

Literature

Bill Hammond: Jingle Jangle Morning (Christchurch: Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, 2008). Full page illustration, p.174

Bill Hammond’s artistic vision is incomparable. Though its quality is immediately evident, his mature work has no real precedents. One could draw links between his bird-people and depictions of angels in Italian Renaissance painting, or compare his richly detailed compositions to those of the highly imaginative 16th Century Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch, or relate the overall tone of his paintings with contemporary fantasy illustration. Yet none of this makes for a satisfactory contextual framework. Hammond’s paintings – like the astonishing birdlife they were inspired by – are sui generis, unlike anything else.

Hammond’s transformational trip to the sub-Antarctic Auckland Islands in 1989 is perhaps the most mythologised story in the art history of Aotearoa. It was there that he encountered a staggering abundance of avian life, much as would have existed on the main islands of New Zealand before humans arrived. After this journey, the artist began to incorporate anthropomorphic bird figures into his paintings. Engaged in a range of esoteric rituals and activities, Hammond’s bird figures have become one of the most

recognisable motifs in New Zealand painting of any era.

Dunedin photographer Lloyd Godman was also on that trip, where he took some now iconic photographs of Hammond. He once commented on the huge albatross that inhabited the islands. With necks extended, they stood as high as a human torso. They would walk close by human visitors with no sense of danger. Godman noted the manaia figures in Māori carvings feature what could be bird heads on human forms. Hammond was quite possibly referencing this, either directly or obtusely, while painting his extraordinary works.

Unknown European Artist is among the very finest of Hammond’s paintings. It is breathtakingly refined and flawlessly executed. The scale is impressive and the details rich, allowing a viewer to fully experience the complexity and nuance of Hammond at his best. Compositionally, the work is dazzling; dozens of bird figures are set against a snaking harbour or inlet and accompanying headland. The complex array of elements are arranged seamlessly.

Hammond was active as an exhibiting artist from 1980 through to his death in 2021. Of all the periods of his work, there is none more highly appreciated and sought after than 1999–2005. At this time, his vision was mature and his technical skills were at their most polished. The palette of Unknown European Artist is the deep emerald green and mesmerising gold distinctive of Hammond’s work at this time. This combination of colours creates a striking effect of light and shadow, setting the luminous bird crea-

tures against a shadowy backdrop of land and sea.

In the foreword to the Jingle Jangle Morning book, Jenny Harper (the Director of Christchurch Art Gallery at the time of the book’s publication) stated, “In their early years these anthropomorphic birds on Hammond’s canvases perhaps represented the great flocks killed and stuffed by Victorian ornithologist Sir Walter Lawry Buller, but over the years they have grown into something quite different –a beautiful but at times also sinister race.”1 Examples from the early nineties, such as Waiting for Buller. Bar (1993), and Watching for Buller (1994), give a sense that the birds are waiting to enact retribution on the murderous ornithologist. Yet, his later works have an entirely different feel. These bird people are poised, engaged in their own rituals and life processes, not defined by the activity of Buller or any other human. In such works, one can catch a glimpse of the parallel world Hammond creates, a world inhabited by bird figures with their own motives and ways of being.

Of course, this parallel reality reflects and comments on our own. In an article titled The Edge of the Sea, writer Laurence Simmons states, “Hammond’s world is fraught with significance, immanent with shadowed meaning, he presents us with a landscape strewn with clues of colonisation and the colonial imperial project. A forest thinned out. An endlessly interpreted world in which practically everything is metaphor and nothing merely itself.”2 Just what the metaphors are is open to interpretation – Hammond was notoriously reticent when it came to discussing the meaning of his work, allowing viewers to make to

create their own understandings of his extraordinary paintings.

Two of the principal bird figures in Unknown European Artist are holding human forms. They are skull-headed, figurine-like. An explanation of these figures, along with the title of the work, comes from an anecdotal statement Hammond is believed to have made to the purchaser of the work. ‘Unknown European Artist’ refers to the artist’s father. He was also a painter, though was never recognised. Hammond painted this work after his father’s death, with the birds transporting the deceased unknown artist heavenwards. Viewed through this lens, the bird people act as guardians of the afterlife, companions to the dead.

Hammond never articulated exactly what his birds meant or how they should be read. In Unknown European Artist, the bird figures themselves are ornately detailed. They are covered in delicately painted imagery, as if tattooed. These unique glyphs are a language unto themselves, comprised of geometrically arranged floral motifs. While exactly what Hammond was saying with this work may have been in an indecipherable tongue, it is undoubtedly rich and complex.

1. Bill Hammond: Jingle Jangle Morning (Christchurch: Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, 2008), p.10

2. Laurence Simmons, “The Edge of the Sea” B.201, August 2020

Patrick Hanly (1932–2004, NZ)

Hope of Paradise, 1960 oil on board

signed ‘P. Hanly’ lower right

610 x 796mm

765 x 955mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau

Auckland The 1960s was a pivotal era for Pat Hanly. Having moved to London in the late 1950s with his wife Gil, he went on to paint his first major series of oil paintings, The Fire Series. It was the height of the Cold War; thus, these works can be seen as a personal response to the fearful socio-political climate, reflecting Hanly’s personal anxieties about nuclear conflict and human suffering. Hope of Paradise (1960) is a key work from this series, demonstrating Hanly’s ability to maintain faith in humanity despite this terrible subject matter. Lyrical brushwork and an Eden-like palette of greens and blues lends this piece an air of hope, distinctly calmer than other works from the series.

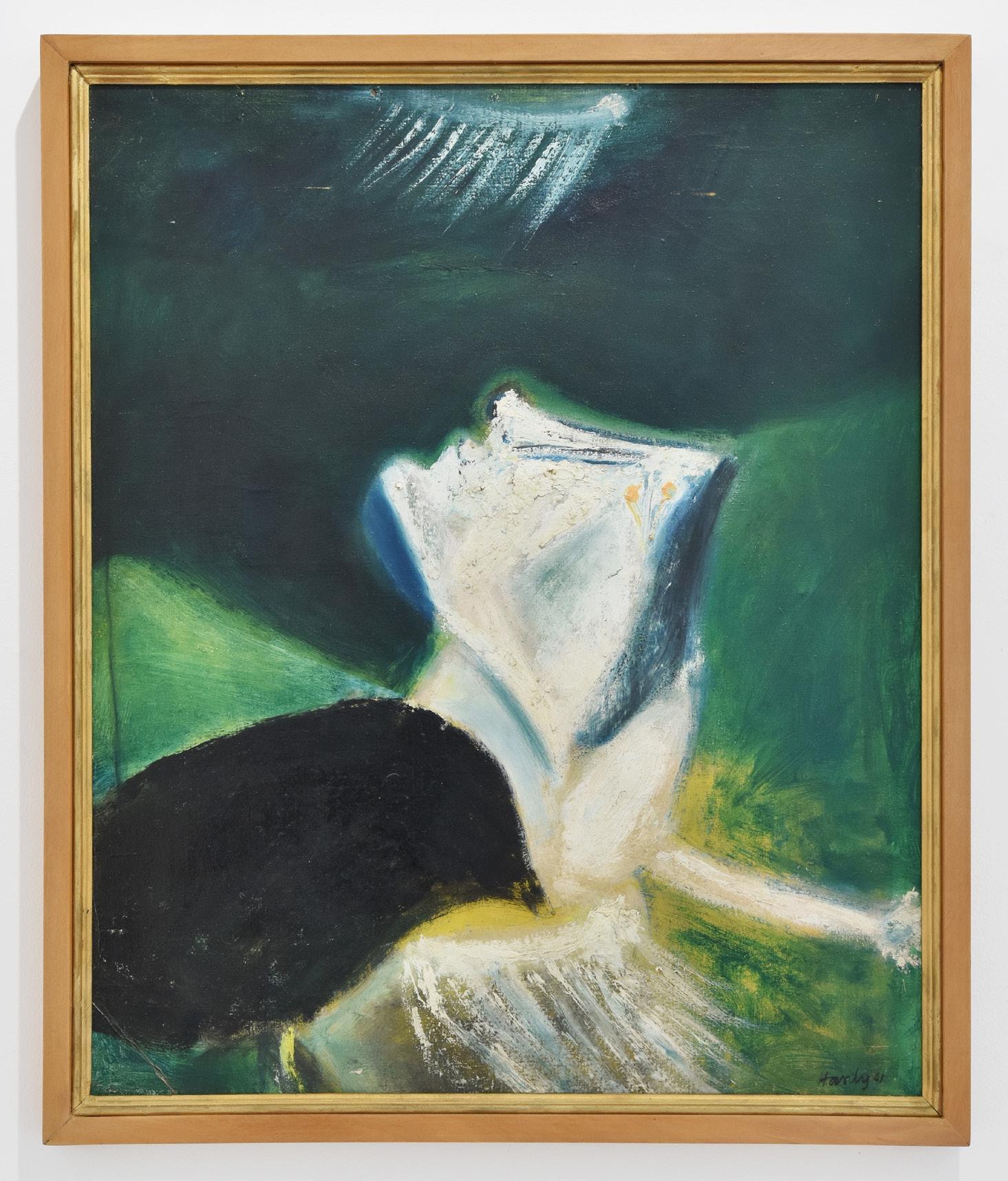

Painted just one year following, The Woman, is a profound piece from Hanly’s Massacre of the Innocents series. Painted when the artist received a three-month grant from the Dutch Government to work in Amsterdam, the artist has stated that these works were about ‘the inevitability of death and destruction wrought on man by his own follies and the ghastly waster of people and property by war.’1 Massacre of the Innocents Series - The Woman, can be seen as a visual

outcry against violence and the brutalities of war, this specific work capturing the essence of grief and vulnerability. The abstract nature of the painting allows for multiple interpretations, compelling viewers to confront their own perceptions of pain, loss, and hope. Hanly employs a rich colour palette dominated by deep greens and stark whites, creating a powerful contrast and drawing the viewer’s eye to the central figure. The abstract form suggests a figure in despair, bent over in sorrow or anguish. The use of light and shadow in the upper part of the canvas alludes to a looming presence or a distant glimmer of hope, suggestive of a spiritual or metaphysical dimension present within the depicted suffering.

Hanly’s ability to marry abstract techniques with deeply humanist themes helped cement his legacy as one of New Zealand’s foremost painters. His work remains a poignant reminder of the role of art in addressing the anxieties and ambitions of humanity.

1. Hanly (Auckland: Ron Sang Publications, 2012), ed. Gregory O’Brien, photo ed. Gil Hanly, p.29

Patrick Hanly (1932–2004, NZ)

Massacre of the Innocents Series - The Woman, 1961 oil on canvas

signed and dated ‘Hanly 61’ lower right

680 x 560mm

740 x 620mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

Dame Louise Henderson (1902–1994, FR/NZ)

Untitled [Still life with vase], 1987 oil on board signed and dated ‘Louise Henderson 1987’ lower right 805 x 595mm 880 x 670 x 25mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau

Auckland

Dame Louise Henderson was a pioneer of abstraction in New Zealand and one of few female career painters of her generation. Her phenomenal and influential career left a remarkable body of work now held in all major public collections in Aotearoa.

Born in Paris in 1902, Henderson moved to Ōtautahi Christchurch in 1925 to be with her new husband, Hubert Henderson – a New Zealander. Cultivated by her European experience and engaged in her immediate surroundings, her works were simultaneously local and international. Her earliest works offered thoughtful and detailed observations of her new environment, and she became known particularly for her cubist and modernist works which showcase her expressive use of colour.

Establishing herself as a central figure in the local art scene, Henderson would go on to work alongside major figures including Rita Angus, John Weeks, Colin McCahon and Milan

Mrkusich. She later described ‘the social and creative freedom of those early years in New Zealand as “like opening a door for a bird to fly”.’1

Untitled [Still life with vase] was painted well into her career, in her mid-eighties. The work embraces cubism, seen through the geometric patterning and flattened perspectives of the table and vase, but her use of bright colour evokes the abstracted form and atmosphere of the New Zealand landscape. At this time, she was living in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, with her artist studio located in Mount Eden and surrounded by native bush. This landscape would inform her later series of works, drawing inspiration from the view outside her window.

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū co-curated a large retrospective exhibition titled Louise Henderson: From Life (2019-2020). The curators noted, ‘despite the seemingly dramatic shifts

in style, which have been too easily dismissed as a dependency on different international art movements, Henderson’s oeuvre maintains a rigorous consistency. She sought to convey the essence of her subject through a complex visual language of layered and interlocking shapes’.2

Full of bold, colourful observations of life and nature alongside her abstracted still-life compositions, the exhibition celebrated her decades-long career as a strong-minded, experimental and instinctive artist.

Henderson’s artistic expression also included embroidery, stained glass, and tapestry, and she had a lifetime commitment to education. Born into an era in society where female artists and writers were not treated with the same respect as their male counterparts, Henderson is now rightly recognised as highly significant to Aotearoa New Zealand’s art history. Louise Henderson was honoured to become Dame Louise Henderson in 1992, one of only three woman New Zealand artists to achieve such acclaim.

1. https://christchurchartgallery.org.nz/blog/ media-release/2020/06/missing-louisehenderson-artwork-to-be-shown-in-ch

2. Milburn, F., Strongman, L., Waite, J. (eds) (2019) Louise Henderson From Life NZ: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, p.14

Ralph Hotere (1931–2013, NZ)

Sunrise Mururoa, 1985 oil and acrylic on canvas inscribed lower left: “DAWN WATER POEM / (after Manhire)/ Hotere, Port Chalmers ’85” 2040 x 1800mm

Provenance

Janne Land Gallery, Wellington; Private collection, Te Whanganui-aTara Wellington

Literature

Ralph Hotere, Kriselle Baker and Vincent O’Sullivan (Auckland: Ron Sang Publications, 2008). Full page illustration p.47

Ralph Hotere’s Sunrise Mururoa is a striking reflection on New Zealand’s stance against nuclear testing in the South Pacific, resonating with the global anti-nuclear movement of the 1980s. This artwork serves as a vivid protest against the French nuclear tests conducted at Mururoa Atoll, a site that became a symbol of environmental and political conflict.

Inspired by Bill Manhire’s concrete poem Dawn/Water from 1978, Hotere transforms the original work’s visual simplicity into a potent statement of resistance. Manhire’s poem, arranged to evoke the sunrise over the ocean, is reimagined by Hotere with the addition of the word “MURUROA,” shifting its meaning from a meditative reflection to a powerful critique of nuclear colonialism.

The misspelling of ‘Mururoa’ as ‘Moruroa’ by French cartographers in the 1960s, alongside the name’s original Mangarevan meaning of ‘the place of great secrecy’, adds layers of irony and urgency to Hotere’s piece. This error highlights a broader context of colonial oversight and environmental neglect. The central circular motif in the artwork not only suggests the sun but also evokes the destructive potential of a nuclear explosion, visually reinforcing the protest.

Hotere’s integration of Manhire’s subdued poetic style into his artwork reflects a deeper engagement with the intersection of art and activism. Where Manhire’s poetry is marked by calm yet profound rhetoric, Hotere’s approach in Sunrise Mururoa is more direct and visceral, using vibrant vermilion and

textured surfaces to convey urgency and intensity. The canvas, punctuated by fourteen metal rivets, subtly references the Stations of the Cross, drawing a parallel between the crucifixion journey and the anticipated devastation of the South Pacific. Unlike the narrative of redemption in the Stations of the Cross, Hotere’s work offers a sombre prophecy of ecological disaster, underscoring the gravity of the situation without offering solace.

Distinct from the more lyrical qualities of Hotere’s earlier Requiem series, Sunrise Mururoa emphasizes a raw and immediate visual impact. The work’s bold colours and dynamic texture capture both the beauty and terror of the subject matter, challenging the notion that art’s beauty is divorced from its political and emotional weight. This work stands as a powerful testament to Hotere’s ability to merge artistic expression with critical commentary, remaining a poignant piece in the dialogue on nuclear resistance and environmental advocacy.

Sir Mountford Tosswill Woollaston (1910–1998, NZ)

Yellow Nude, c. 1972 oil on board signed ‘Woollaston’ lower rght 920 x 1215mm 945 x 1240mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, Ōtepoti Dunedin

Toss Woollaston is widely regarded as one of New Zealand’s most important modernist painters. Born in Taranaki in 1910, he moved to Christchurch to study at the Canterbury School of Art in 1931. Unhappy with the conservative artmaking methods of the school, he relocated to Dunedin the following year to study under R.N. Field. There, study was focussed on modernist practices, which were still emergent at the time. Subsequently, he settled permanently in the South Island, first in Mapua, and later in Greymouth. He became particularly well known for his highly expressive West Coast paintings and remained active as an artist into his 80s. To this day, his work remains among the nation’s most notable and prized. Though Woollaston is best known for his landscapes, figurative paintings were central to his development as an artist and a consistent thread throughout his oeuvre. Writer and curator Luit Bieringa discussed the role of figuration in Woollaston’s work, stating that historically, “Figure and portrait painting, like still-life painting, has

never been much to the forefront in the studies of New Zealand painting. The reasons for this are quite obvious considering the ubiquitous presence of the landscape and its apparent accessibility as a subject…in the case of the painters of the new generation like Woollaston, McCahon and the late Rita Angus, portraiture and figure studies formed a major part of their oeuvre.”

In the earlier stages of his career, the artist juggled his artmaking around fulltime employment, painting at night and during weekends. He produced many portraits and figure studies, mostly of his family and friends. Bieringa wrote, “This expediency laid the foundations to one of the major aspects of Wollaston’s oeuvre, often forgotten, that he is one of New Zealand’s most successful painters of people. His development as a portrait painter over the years has been synonymous with his portrayal of the localities he has depicted. Indeed in 1961 he said with reference to his portraits ‘They are not portraits but extensions of the landscape into human shape’.”

Yellow Nude is a later work, painted in the early 1970s. It was sold by Peter McLeavey in 1972 and has remained

with the same collector until today. The painting depicts a striking figure set in a landscape environment with sharply contrasting tones between figure and ground. The paint handling is distinctively Woollaston’s, with energetic application and significant areas left raw, particularly in the background. Bieringa stated that some of the best features of the artist’s figurative works were his use of “unpainted areas, parallel strokes of dulled yet glowing colours and broad, broken charcoal lines - all joining forces to create a series of dynamic planes.”

An interpretive framework for Yellow Nude could be a metaphorical relationship between the figure and the landscape – a depiction of the environment and ecology in human form. The artist was deeply

interested in the natural world – both in its fragility and rich beauty, qualities Yellow Nude gracefully conveys. The palette of the painting is in an earthy configuration unique to Woollaston. The artist himself stated, “Writers on my work are fond of quoting me as having said many years ago, that I wanted to paint the light, but only after it had been absorbed into the earth. It is true. Therefore, yellow ochre is my only yellow. I don’t need any brighter. I find the most exciting exercise is to set it next to another colour (or other colours) so that it glows and looks brighter than people would have supposed it could.” In Yellow Nude, the ochre of the figure is surprisingly rich and luminous, as if Woollaston had written those words of this very work.

Sir Mountford Tosswill Woollaston (1910–1998, NZ)

North of Nelson, 1960 oil on board

600 x 800mm

705 x 905mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau

Auckland

There is an immediacy to North of Nelson with its brisque, energetic brushstrokes. It is a striking example of Woollaston’s depiction of landscape for which he is most celebrated. The work’s earthy palette is the result of extended looking, of wanting to capture a likeness or essence of the landscape. Woollaston describes a search for ‘the feeling you get when you look at a distant landscape trying to penetrate it.’1

Throughout his career Woollaston would often create sketches and drawings en-plein air. His son Philip describes him as sitting still in the landscape, looking - for what seemed like hours, before a flurry of action.2 For an oil such as North of Nelson, the process was more prolonged and considered, with Woollaston harnessing the passage of time, but it retains a sense of spontaneity and energy from the artist’s engaged practice of looking. Woollaston has an interest in the structure of painting which pushed him to play with scale, bringing elements to

the forefront that feel most urgent and allowing others to recede.

By the 1960s, Woollaston was becoming well recognized as a painter. In 1958 he was awarded a Fellowship that allowed him to travel to Australia, while in 1960 he presented an autobiographical lecture, The Far-away Hills: a meditation on New Zealand landscape, to the Auckland Gallery Associates at the Auckland City Art Gallery. This lecture was later published by the Associates. Nelson and the West Coast were a primary source of inspiration throughout the artist’s career.

Woollaston was a transformative figure in Aotearoa’s art history and is widely recognised as one our pioneers of modernism. North of Nelson is a wonderful example of Woollaston’s vision of the land, at a point where his career was gaining recognition and his painting was flourishing.

1. Jill Trevelyan (ed), Toss Woollaston: A Life in Letters (Wellington: Te Papa Press, 2004) 2. https://vimeo.com/943487063

Tony Fomison (1939–1990, NZ)

Life and Death, 1989

oil on jute laid onto board titled, signed and dated 1989 and inscribed ‘Williamson Ave, Grey Lynn’ verso

280 x 230mm

480 x 420mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau

Auckland

Faces are a subject matter that dominate many of Tony Fomison’s paintings. Often distorted and looming, they encapsulate the anxious subjects that he continually explored in his art practice – his self, his relationship to his community, religion and death.

Painted in his characteristic earthy chiaroscuro tones, in Life and Death we see two faces pushed forward in the picture plane, devoid of any context in the form of space or time. In the foreground of the painting is a rounded head, bald and melancholic. We can assume this figure is an allegory of ‘life’, and thus a summarisation of Fomison’s own anxieties surrounding human experience. Overtop is a distorted face, perhaps in the caricature of a jester or demon – who we can only assume is an allegory of ‘death’.

Fomison’s forms are generalised rather than individual, reminiscent of his repeated exploration of Christ, clowns, jesters or the ‘humpty dumpty’

figure that was present in several of his works. Unnamed, his faces represent hallucinations of perception and reality. There is an uncomfortable inevitability in Life and Death, reflective of Fomison’s own turbulent struggles.

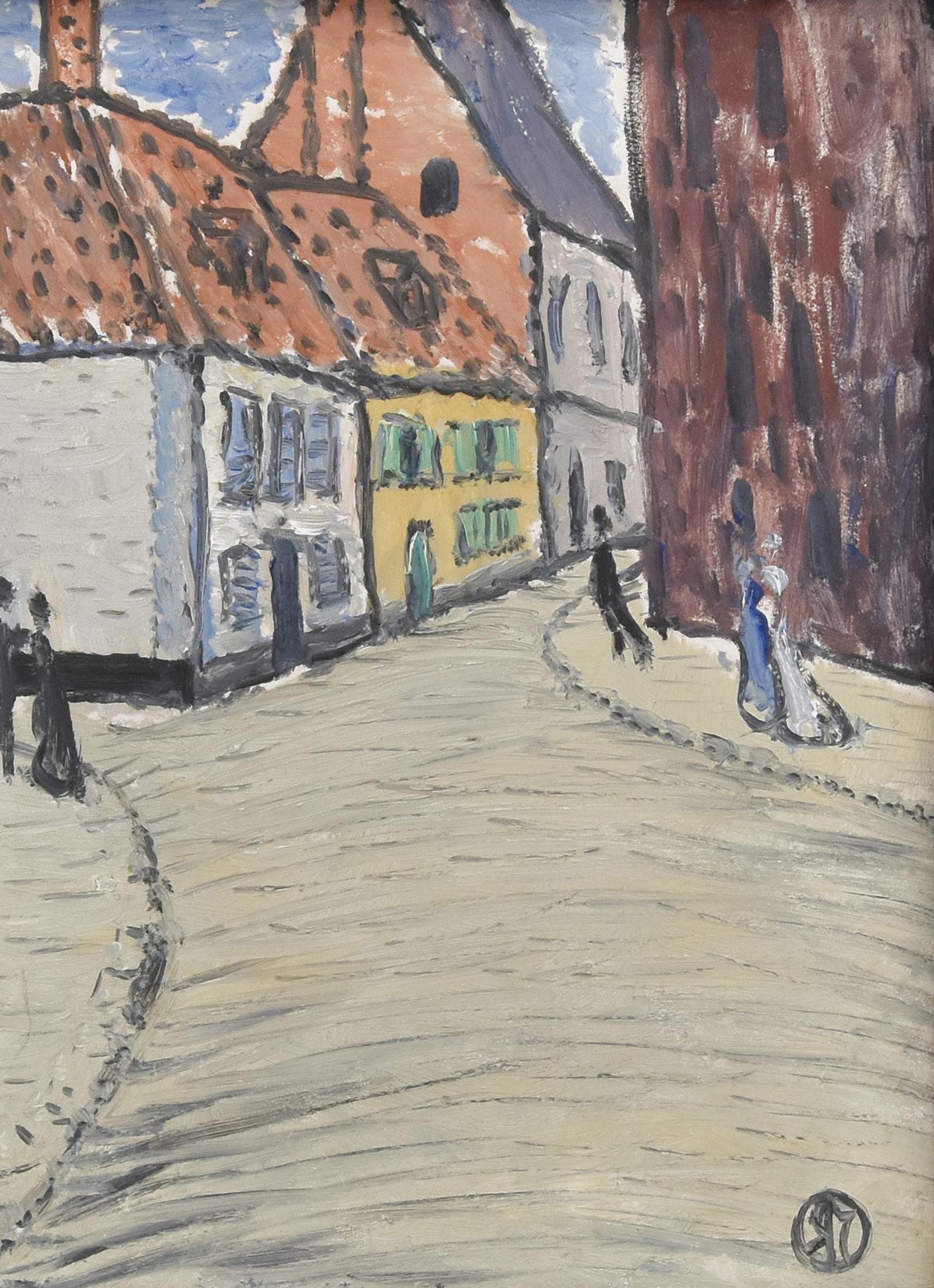

Raymond McIntyre (1879–1933, NZ)

Street in Saint Valery-sur-Somme, c.1915 oil on board

signed with monogram lower right, inscribed with title on a label attached verso

295 x 245mm

490 x 440mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, Hay on Wye, Wales; Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau

Auckland Raymond McIntyre’s painting Street in Saint Valery-sur-Somme is a charming depiction of the French street, painted by the New Zealand-born expatriate artist. It captures a moment in the small coastal town of Saint Valery-surSomme, located in northern France. McIntyre’s use of thick brushstrokes and muted yet vibrant colours bring the scene to life, reflecting his deep connection to the European art movements of the early 20th century, predominantly post-impressionism. The composition is intimate, with buildings lining a curved street, leading the viewer’s eye deeper into the scene. The figures are loosely depicted, although the charm of the ladies and gentlemen’s Belle Époque fashions are still perceptible.

McIntyre studied at the Canterbury School of Art in Christchurch before moving to London in 1909. There, his work was influenced by postimpressionist artists such as Paul Cézanne, Vincent Van Gogh, and Henri

Matisse, whom he admired. Among others, he studied under notable artists such as William Nicholson, George Lambert, and Walter Sickert. Throughout the following decade, he frequently showcased his work at The Goupil Gallery. While McIntyre often depicted street scenes, a subject shared with the Camden Town Group, his technique was distinctly different from theirs. In October 1918, he held a significant exhibition at the Eldar Gallery in London. Then, in 1921, as a member of the Monarro Group, he exhibited at the Goupil Gallery alongside Paul Signac, M.L. Pissarro, and Le Maitre. His work received recognition both during his lifetime and posthumously, with exhibitions such as the 1984 Raymond McIntyre Survey Exhibition at the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

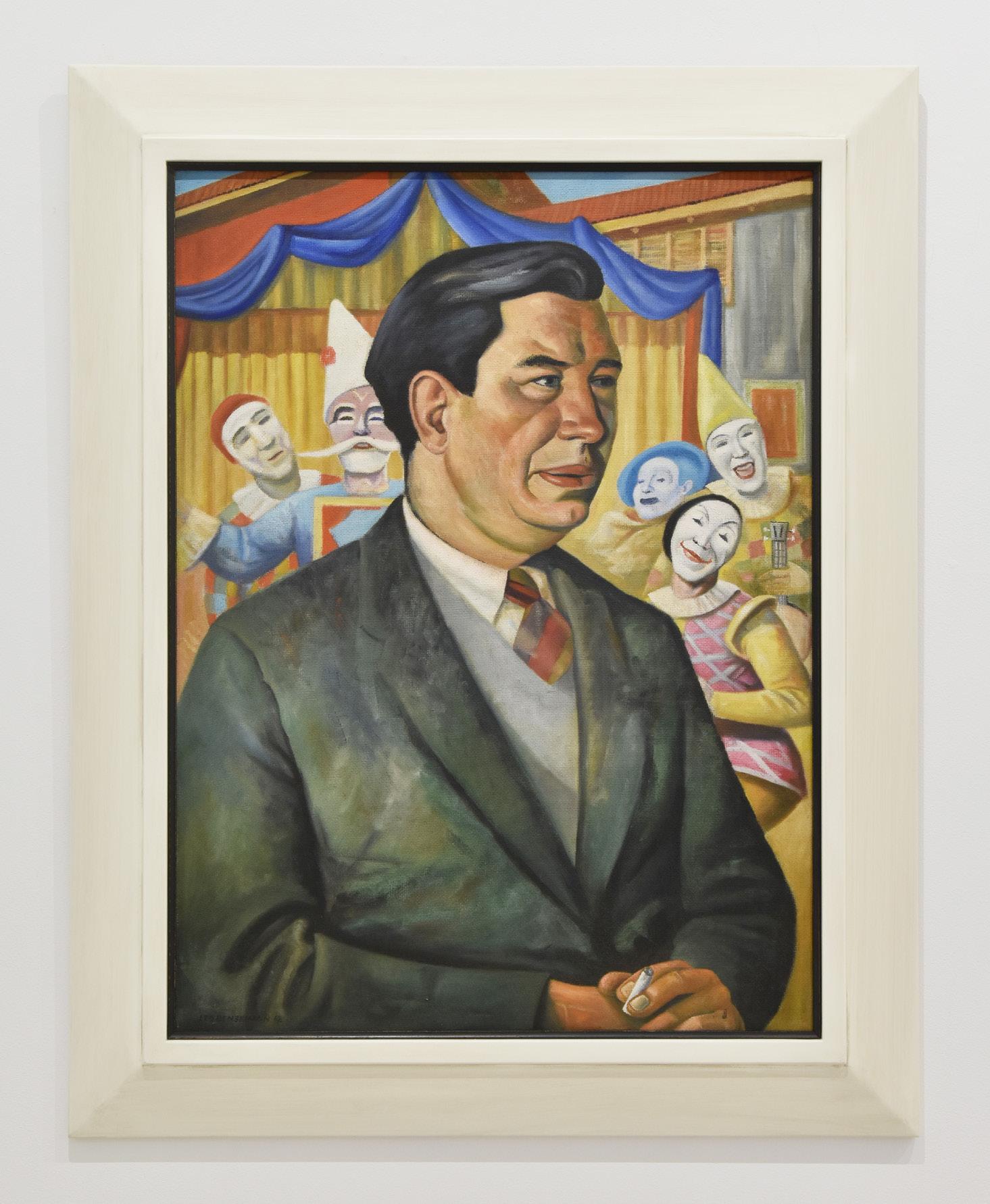

Leo Bensemann (1912–1986, NZ) Gregory Kane, 1962 oil on board signed and dated lower left 790 x 590mm 980 x 780 x 35mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, London

Leo Bensemann moved to Christchurch in 1931. He and his friend Lawrence Baigent moved into a flat at 97 Cambridge Terrace, where Rita Angus was living at the time. In 1938 and on Angus’ recommendation, Bensemann joined The Group–an artist-led collective at the forefront of New Zealand’s avantgarde scene. Members included some of the country’s best-known artists, such as Colin McCahon, Toss Woollaston, Olivia Spencer Bower and of course, Rita Angus. Unlike his contemporaries, Bensemann was primarily working in portraiture rather than landscape painting, and his portraits were highly influenced by his friendships and close relationships with those around him. His paintings provide an insight into the psychology of his sitters, often engaging in portraying the idiosyncrasies of his fellow Group artists.

The subject of this painting is Gregory Kane, noted as a close friend of Bensemann by his daughter Caroline Otto, who writes about an unfinished watercolour of Kane painted during the 1960s.1 Kane was also the sitter for several other portraits by Doris Lusk. A library archive entry states Kane was a Christchurch theatre producer and artist, characteristics which Bensemann appears to imbue into this work. The

background of this painting as what looks to be a circus, with clown-like figures and the outline of a tent, may reference Kane’s position at the theatre and his influence on the Christchurch arts scene.

Otto also notes her father’s interest in the book The Thurber Carnival, a revue by James Thurber adapted from his stories, cartoons and casuals, nearly all of which originally appeared in the New Yorker. Bensemann was intrigued by Thurber’s interpretations of the absurd, in people and everyday life, and this influenced his own work. Bensemann’s portraits aimed to capture more than just the likeness of his sitters, but a whole personality, quirks and all.

Peter Simpson has reflected on the artist; ‘always something of an odd man out, Bensemann has proved hard to integrate into the accepted narrative of New Zealand art history and is much less well known than he deserves. However, the sheer quality of his output over more than fifty years is steadily extending his reputation as one of New Zealand’s most distinctive artists.’2

1 Caroline Otto, Leo Bensemann: Portraits, Masks & Fantasy Figures, Nelson: Nikau Press, 2005, p.92

2 Peter Simpson, Fantastica: The World of Leo Bensemann, Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2011, p.VII

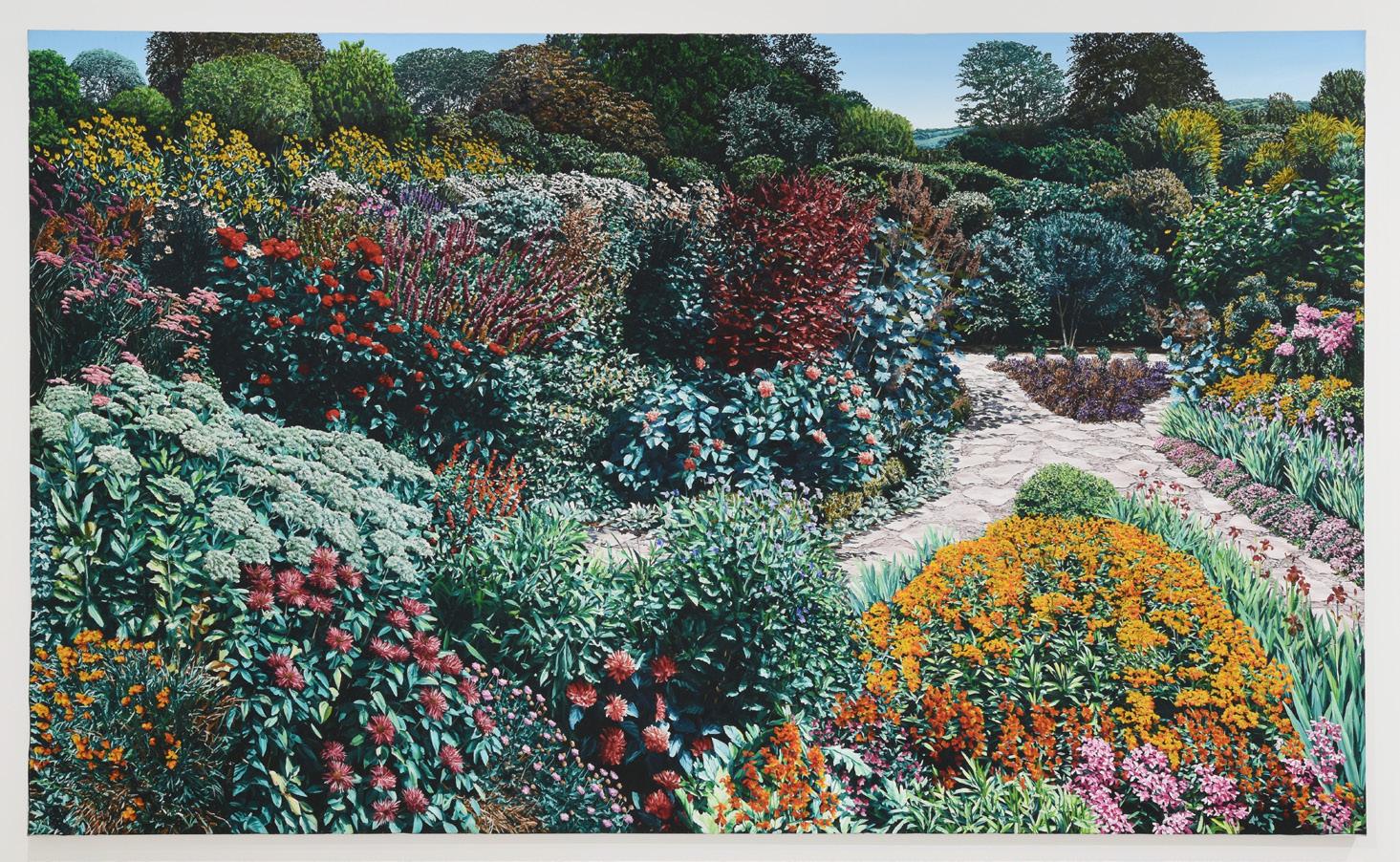

Karl Maughan (b.1964, NZ) Ashhurst, 1998 signed and dated verso oil on canvas 1830 x 3050mm

Provenance

Charles Saatchi collection, London; Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

Karl Maughan’s invitational, immersive commitment to the garden as a framework for painting is enduring. His compositions, borne from close observation, are pieced together in layered constructions to create worlds of evergreen, ever-in-bloom possibility. Having worked with the subject matter for decades, Maughan delights in the garden as a mechanism to explore formal interests in the interplay of light, colour, and shape on a painting’s surface. Artist and author Gregory O’Brien writes, “The gardens are like musical compositions – both the score and the thing played – with their upward and downward inflections, stops and starts, repetitions and transitions, their points of confluence and dispersal. Truth and accuracy are far less of a concern than phrasing, rhythm, pitch, and timbre. ‘You’re not responsible for the veracity of what you are painting,’ he [Maughan] notes. ‘The painting is its own thing.’”1

The large-scale painting Ashhurst is an outstanding example of Karl Maughan’s practice from his London years. The artist moved to London’s

East End in the mid-1990s, sharing a studio space with a group of young British artists who would later rise to fame. This period was hugely formative for Maughan’s practice. This painting, along with Diane (1994) and Plume (1996) were acquired by the renowned businessman and art collector, Charles Saatchi. Maughan’s work was included in the exhibition Neurotic Realism at London’s Saatchi Gallery in 1998, which looked to define a new trend in British art. Shortly afterward, Maughan’s painting, Aro Valley (1999), was purchased by the Arts Council Collection of England. Painted during the same period, Ashhurst possesses a meticulous attention to detail in a work of outstanding scale and quality.

1.Gregory O’Brien ‘Florescence: Notes from the studio,’ Karl Maughan, Auckland: Auckland University Press and Gow Langsford Gallery, 2020 p.153

Richard Killeen (b.1946, NZ)

How may we learn?, 1992 acrylic and collage on aluminium titled, signed and dated; inscribed Cat No. 1340 on artist’s label affixed each part verso 29 pieces, 1400 x 1800mm pictured, dimensions variable

Provenance

Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau

Auckland

Developed over his decades-long career, there is no single, authorised ‘reading’ of Killeen’s cut-outs. Made from cut aluminium, then hand painted with alkyd paint on paper, this is the style Killeen is most well-known for. Looking like encyclopaedic plates or taxonomic museum displays, the works combine images drawn from a wide range of sources - insects, plants, machines, tools, figures, geometric shapes and abstract symbols.

In abandoning the frame, Killeen defies traditional compositional structures, breaking down distinctions between painting, drawing, sculpture and installation. Killeen prescribed simple display instructions for many of his works - ‘hang in any order’. Each individual work within these cut-outs is endlessly moveable, with each configuration opening new conversations and relationships between the individual images. This non-hierarchical construction of the works implies that

each image is created equal, denying any authoritative meaning emanating from the artist.

Although Killeen may relinquish control of the final composition, he still determines the number of included images, their scale, colour and content. He allows an element of chance whilst also ensuring inevitability in the overall style and feel of the works. What unifies the cut-outs is their playful sense of humour, with the viewer able to make their own associations from the jumbled images – a reflection of the consensus of the human experience. Killeen’s practice explores how our reading of images and objects both reflect and create our culture, asking How May We Learn?

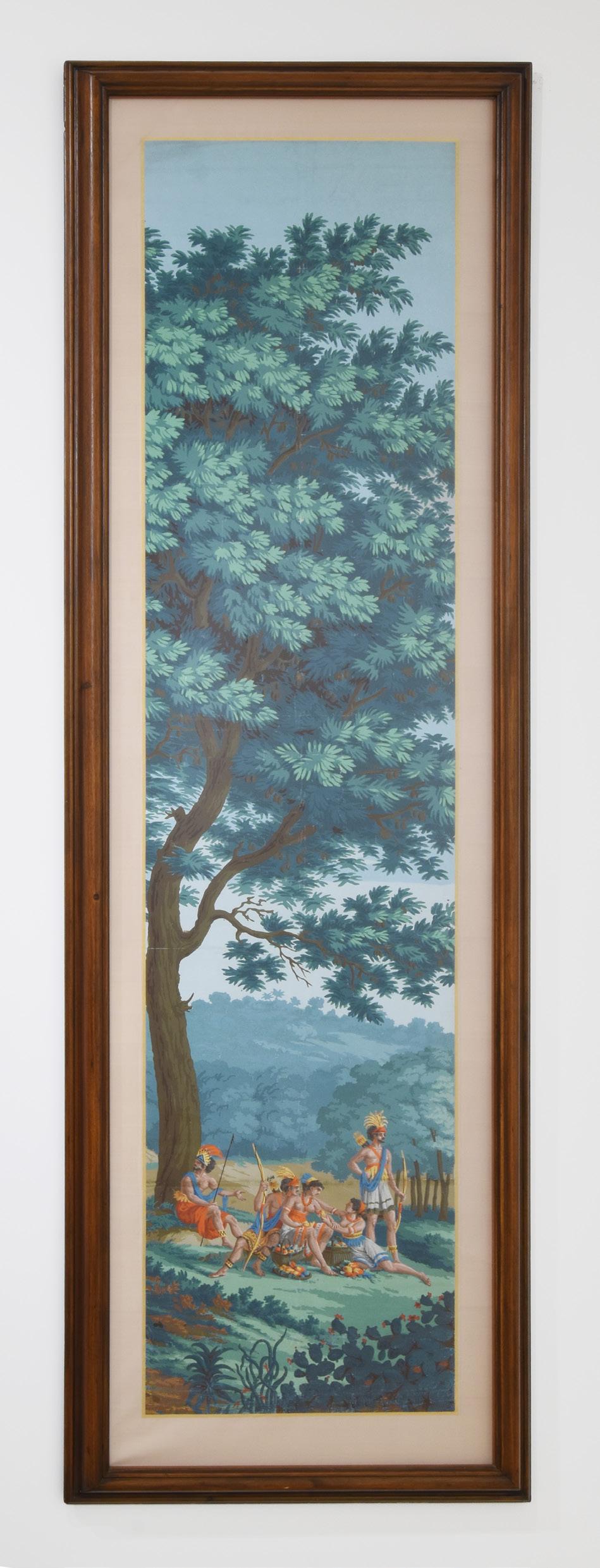

Joseph Dufour et Cie (founded 1797, FR) Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique, panel 2, c.1805

hand coloured woodblock

2265 x 525mm

2600 x 800mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, Derek McDonnell; Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau

Auckland In 2017, Lisa Reihana wowed audiences at the Venice Biennale with her exhibition Emissaries. The central focus of the show was In Pursuit of Venus [infected], an immersive video installation that examined European colonisation of the Pacific. Reihana’s work at the biennale was a showstopper, and it drew considerable acclaim. A key visual reference for this work was the 20-panel panoramic wallpaper, Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique produced by French wallpaper manufacturer Joseph Dufour et Cie in c.1805. Dafour’s remarkable wallpaper is historically significant. It was sold in Europe and North America at a time when interest in the South Pacific was burgeoning in the wake of Cook’s voyages. Its depictions of largely idyllic scenes from across the Pacific proved highly popular with wealthy individuals, who chose it to adorn their homes. It presents an arcadian vision in a Pacific setting, showing a Tahitian picnic with figures that appear influenced by neo-classical, idealised depictions of Roman centurions or Greek archers. The wallpaper was produced in the Lyonnais town of Macon by Dufour

(1752-1827) after designs by the littleknown Jean-Gabriel Charvet (17501829). Incorporating ideas from theatre and landscape design, it captures the intense French interest in the south seas of the 19th Century. Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique has also retained the interest of contemporary viewers, providing a rich visual reference for the colonial attitudes of the time.

This is one panel from the panorama, section 2 of 20, and it is in pristine condition. It was purchased as an unrolled specimen from Maggs, the famous rare books and manuscripts dealers in London in the late 1980s or early 1990s. It was formerly held in the private collection of Derek McDonnell, a rare books and manuscripts expert. It is in remarkable condition, having not been restored, and the colour remains rich and unspoilt. The National Gallery of Australia collection includes a full set that has been restored, and the San Francisco Museum and the Honolulu Museum of Art both have full sets. It is a rare and valued icon of the Pacific, and a fine example of early 19th century French colour printing.

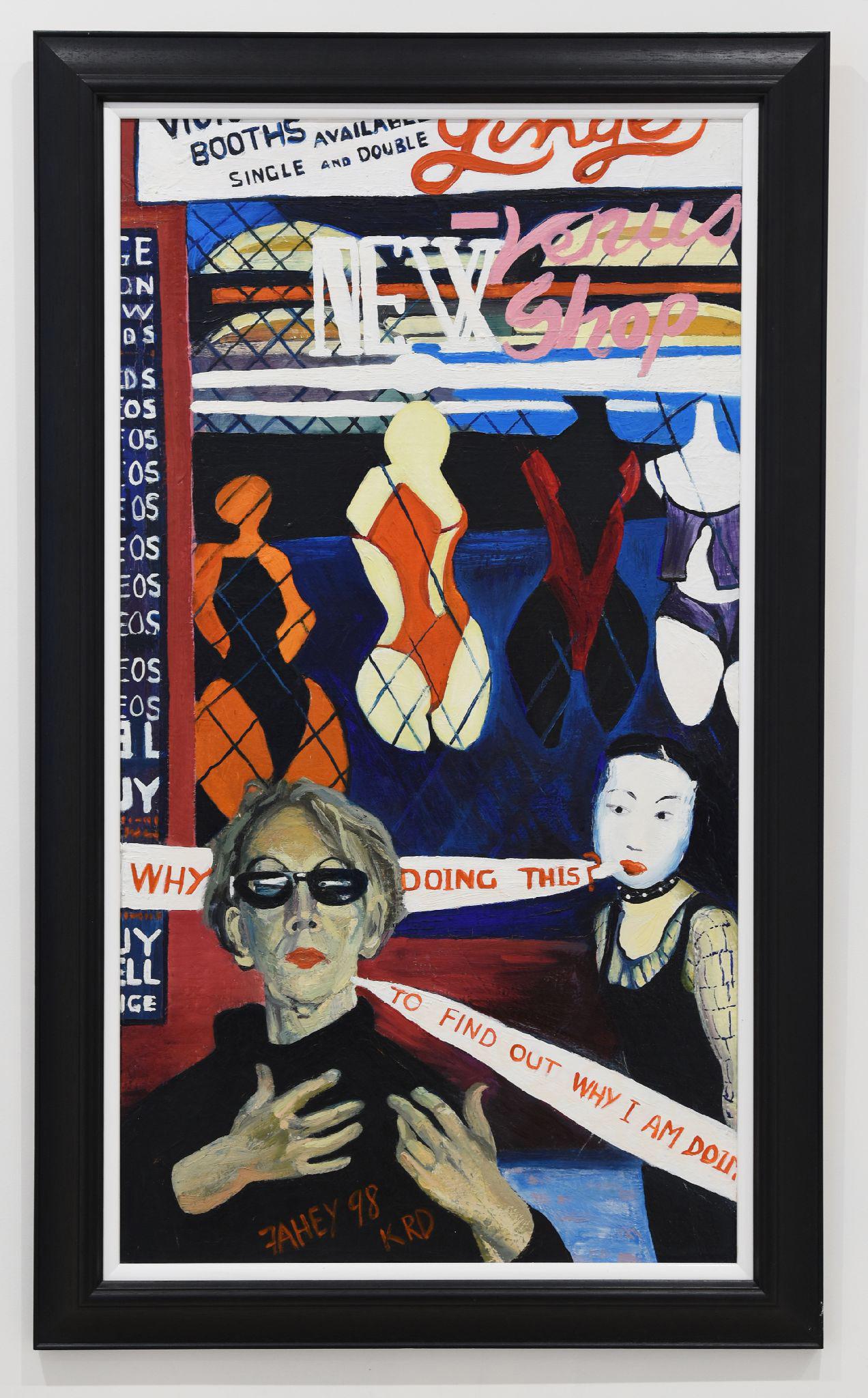

Jacqueline Fahey (b.1929, NZ)

Why are you doing this?, 1998 oil on board signed and dated ‘FAHEY 98/ KRD’ 1095 x 580mm

Provenance

Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau

Auckland In her nineties, Jacqueline Fahey is an iconic and treasured figure in New Zealand art, who continues to push the boundaries of societal structures and politics within her work. Combining vivid portrayals of urban and suburban landscapes with figurative components, she makes observations of people and how we live and communicate. With the rich use of colour and intimate detail in her compositions, her work challenges the status quo and encourages new ways of looking.

She was married and a mother of three from the early stages of her painting career, when the stiflingly gendered society of 1950s and 1960s New Zealand saw Fahey adopt less conventional and at times unpopular subject matter to reflect and actively challenge the gender divide. At times, her deliberate use of perspectival space forces the viewer into the claustrophobia of the female experience. Yet embedded in her approach is a great level of affection for the women and relationships portrayed, evident in the careful detail bestowed on tradition-

ally ‘female’ interests – clothing, interior textiles, bouquets. Later bodies of work went on show Fahey applying her distinctive flare to urban environments and characters, translating domestic politics to their manifestation in the public environment. Why are you doing this?, painted in 1998, is a clear example of this.

The painting features the words ‘New Venus Shop’ written across a shopfront window with a crisscrossed exterior. There is also signage describing available booths and what could be seen as the word ‘lingerie’ in orange text. The mannequins all wear various lingerie items from low-cut one pieces to a two-piece camisole set.

Inscribed ‘Fahey 98 K RD’, this painting is part of her K Rd series in which she painted various scenes of the iconic Karangahape Road during the time she had an artist studio there. As a cultural cornerstone of Auckland City, K Rd has a reputation for its eclecticism. It was, and still is, a hotspot for creatives.

The figure depicted to the right is dressed in a mesh long-sleeve top with a black dress, black studded collar and her face painted in geisha-like make up. The figure is asking ‘Why [are you] doing this?’ and the woman in sunglasses (the artist herself) replies, ‘To find out why I am doing [this]’. Fahey has explained that the act of painting is a quest for answers. In doing the paintings, she seeks to understand why she is doing them herself.

Dame Louise Henderson (1902–1994, FR/NZ)

Arab Portrait No.8, 1959 oil on canvas signed and dated ‘Louise Henderson 1959’ upper right 860 x 630mm

1005 x 780 x 60mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau

Auckland

Exhibited

Louise Henderson: From Life, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, 2019-2020

Literature

Louise Henderson : From Life, Felicity Milburn (Auckland and Christchurch: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki and Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, 2019). Full page illustration, p.113

Dame Louise Henderson’s Arab Portrait No.8 exemplifies her ability to merge geometric abstraction with cultural exploration. The 1950s marked a significant shift in Henderson’s practice, where she moved away from purely representational art towards a more abstracted style that still maintained a strong connection to the subject matter. It was in the late 1950s that Henderson travelled to the Middle East, a region that not only brought new content to her work, but a wholly new exploration of colour and form. Drawn to both the historic sites and modern architecture, Henderson’s practice transcended cubism to embrace a flattening of form influenced by post-cubism.

Arab Portrait No.8 displays these bold, simplified forms and vibrant colour blocks, reflecting her fascination with the region’s cultural symbols and architecture. The work can be celebrated for its formal qualities—a strong composition with rhythmic lines and a harmonious colour palette—yet it is also deeply imbued with a sense of place and personal experience. The abstraction serves not only as an aesthetic choice but as a means of capturing the essence of the Arab culture she encountered, distilling her observations and experiences into a visual language that blends modernity and history.

Robert Ellis (1929–2021, UK/NZ)

River Bend and City, 1964 oil on hardboard signed and dated lower left 905 x 698mm 930 x 725mm framed

Provenance

Private collection, Tāmaki Makaurau

Auckland

Robert Ellis grew up in post-war England, a landscape shaped by industrialization and reconstruction. He initially trained as a graphic designer, studying at Northampton School of Art and the Royal College of Art in London. His training gave him a solid foundation in drawing and design, but it was during his time in London that Ellis began to gravitate toward painting. His move to New Zealand in 1957 marked a turning point in his artistic career. Ellis took up a teaching position at the University of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts, where he taught for over three decades, significantly influencing younger generations of New Zealand artists. Cityscapes—or more specifically city lights, streets, motorways and waterways—became an enduring subject in Robert Ellis’ oeuvre and dominated his works from the early 1960s to mid-1970s. River Bend and City is a notable work from the series, painted in 1964 when he was well established in this theme. Unlike the earlier works,

which included horizon perspectives, River Bend and City is purely an aerial perspective showing a city engulfed and enclosed by the surrounding darkness. This perspective abstracts the city, reducing it to a network of lines, shapes, and colours, making the urban environment feel simultaneously familiar and alien.

As Hamish Keith wrote in a Barry Lett Galleries catalogue from 1965, “Robert Ellis offers us a vision of the city as it may be – were man to leave it entirely to its own devices…The city is built in the image of man. In Ellis’ painting this image is endowed with an organic life of its own. Here the city is not what man has fashioned, it is what the city has made itself.”1

1. Hamish Keith, “Robert Ellis”, Barry Lett Galleries catalogue, 1965

4 Princes St.

Onehunga Auckland 1061

GOW LANGSFORD

28-36 Wellesley St. East

Contact

info@gowlangsfordgallery.co.nz

www.gowlangsford.co.nz

+64 9 303 9395

Hours

Auckland City

Monday - Friday 10am-5pm

Saturday 10am - 4pm

Onehunga

Thursday - Friday 10am-5pm

Saturday 10am-4pm

Or by appointment