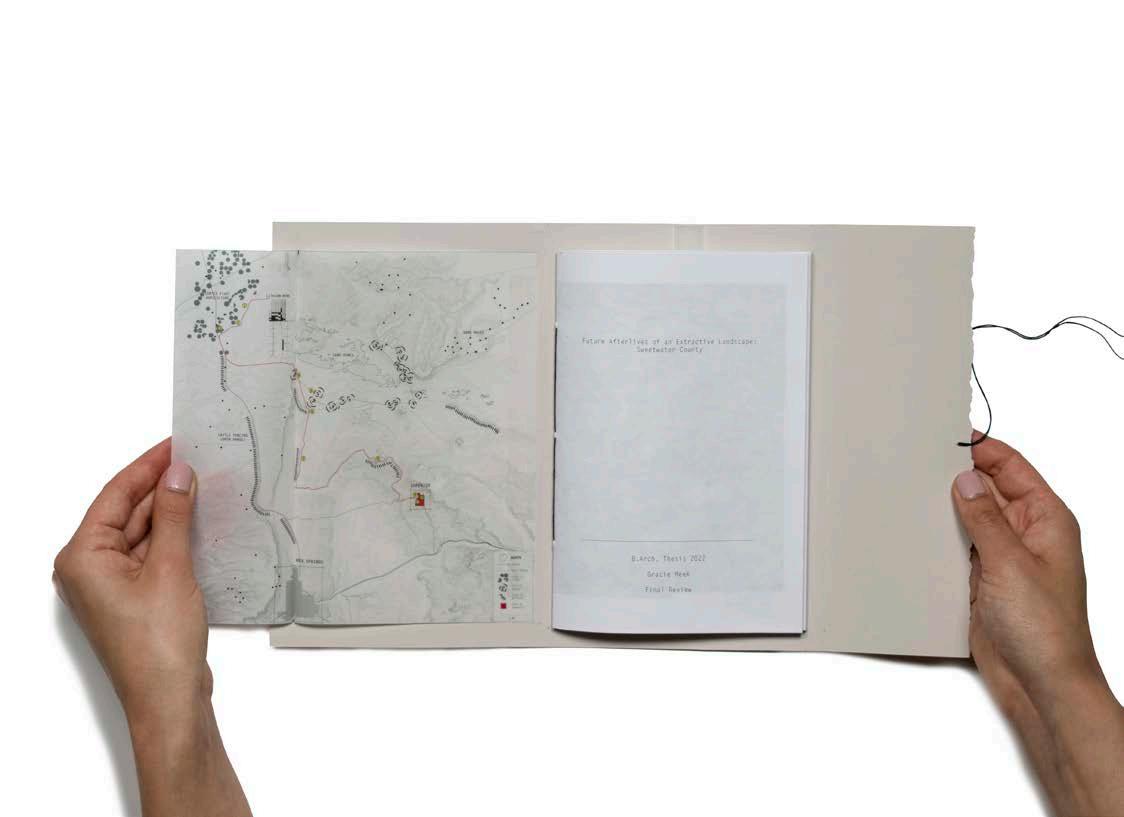

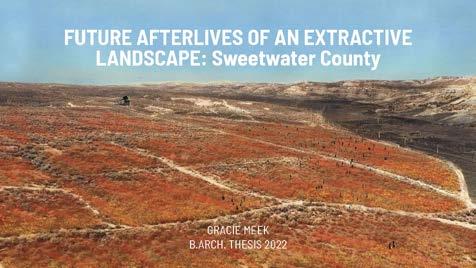

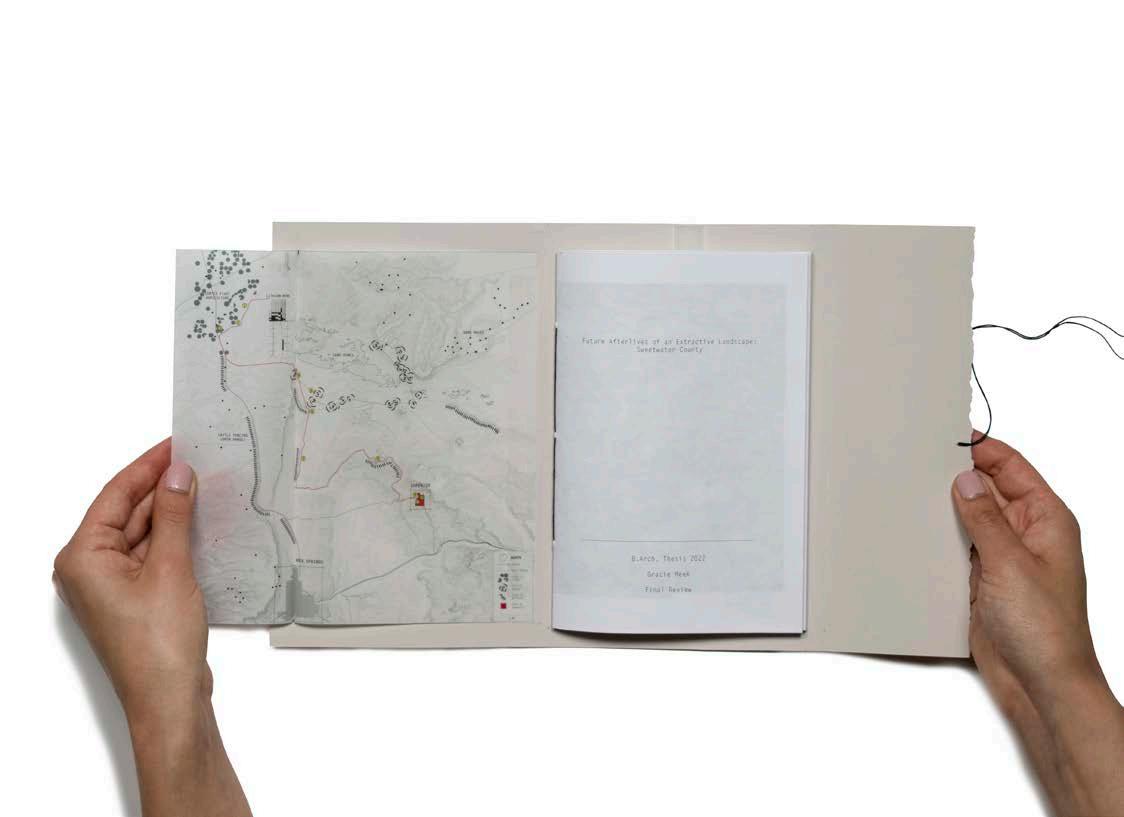

Future Afterlives of an Extractive Landscape: Sweetwater County

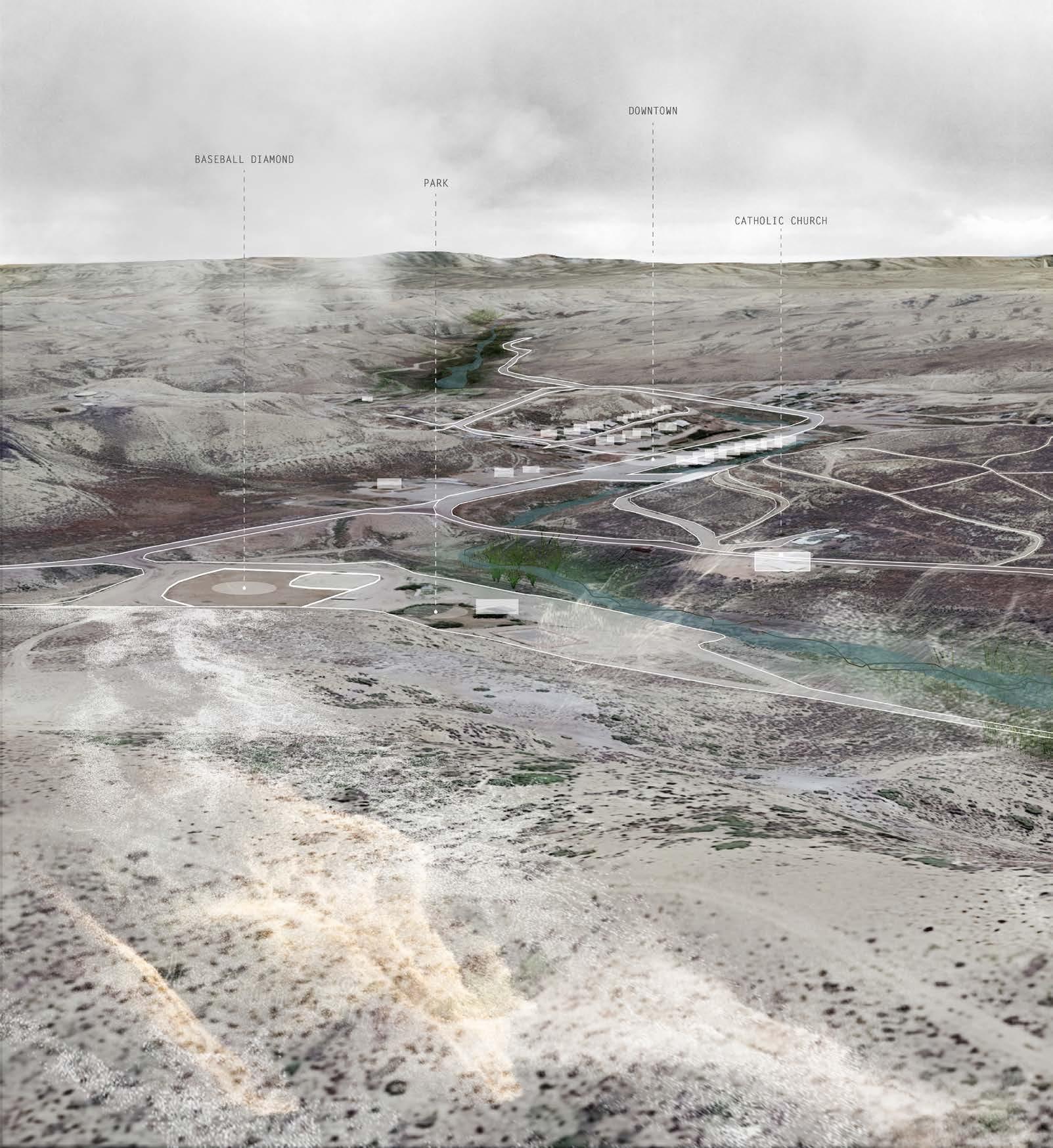

Future Afterlives of an Extractive Landscape: Sweetwater County by Gracie Meek

A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Bachelor of Architecture at Cornell University May 2022

Advisors: Lily Chi and Tao DuFour

Dedication

This thesis is dedicated to William and Francis Sines, my grandparents. Without your vivid stories of the good old days in Superior and Rock Springs, this thesis would not exist.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

While I am indebted to countless classmates, friends, family members, and professors whose conversations, ideas, and advice led to the completion of this thesis, I offer my foremost appreciation to my parents, Robert and Marilyn Meek. In retrospect, it is evident that growing up under parents whose passions range from the physical sciences and geology to drone flight and the history of the Wild West undoubtedly influenced the direction of this thesis. Apart from your academic inspiration, your love and encouragement motivated me to persevere through five years of architecture school.

I express my deepest gratitude to my thesis advisors, Lily Chi, Ph.D., and Tao DuFour, Ph.D., for providing me with invaluable guidance throughout this research. Your continual passion, excitement, and honest criticism inspired me to think innovatively and have fun in the process of this thesis. It has been an honor and privilege to work with you both for more than one semester, and the direction of this thesis, combined with our past studios, has shaped my academic interests and life decisions. Lily, your dynamism, vision, and rigor, and Tao, your sincerity, brilliance, and great sense of humor made this by far my most enjoyable semester.

The Highland Homies (Zana Hossain, Abigail Calva, Ing Wongpaitoonpiya, Jaein Lee, Duncan Xu, Jacob Wong, and Polen Guzelocak) kept me well fed and my levels of serotonin high. Our spontaneous gatherings, serenity walks around Beebe Lake, and study-break laps around the Quad kept me at a decent level of sanity over the past ten semesters. For who?! For Him!!

My sincere thanks also go to The Lineage (Lauren Lam, Miriam Gitelman, Charlotte Zhang, and Tracy Qiu, and those above on the ladder) for your friendship, endless hype, and eleventh-hour assistance.

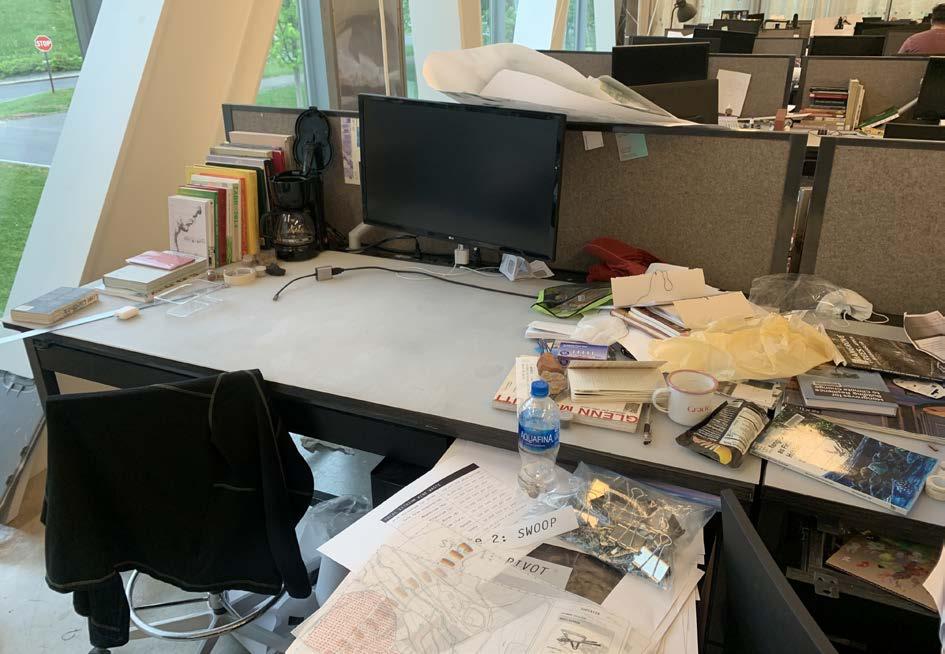

Last but not least, I would like to thank my Studio Deskmates (Theo Neil Blones, Joe McGranahan, and Joseph Appiah) for always lightening the mood—whenever I walked into studio and saw one of you already there, my happiness and inspiration were instantly amplified.

Final

Appendix:

PHASE

PHASE

P PHASE III ARCHIVE I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV 11 13 19 29 45 65 91 107 123 195 209 227 341 363 CONTENTS

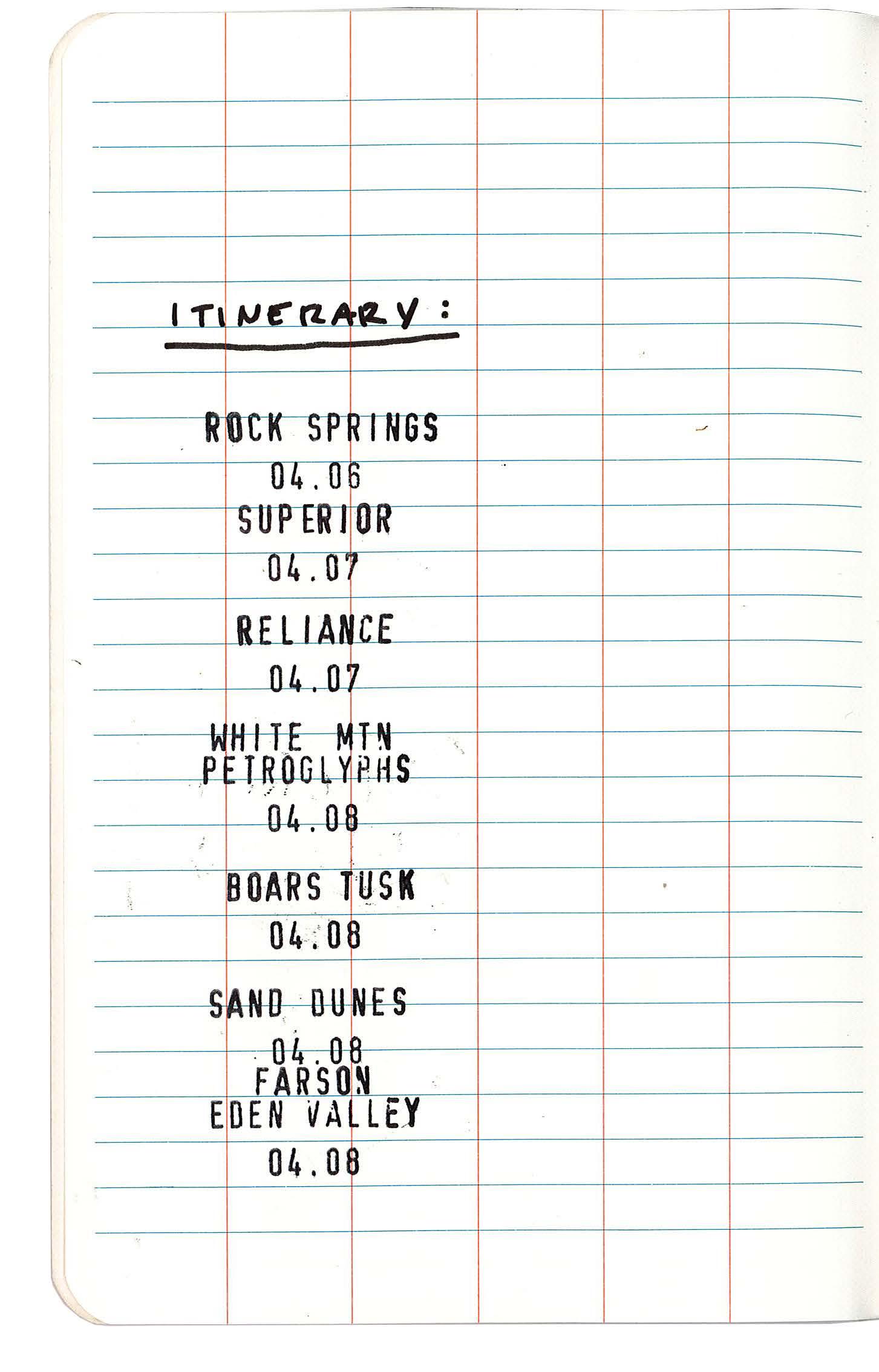

Introduction Proposal Energy Source Analyses An Electrified Landscape Superior and Rock Springs Historical Archive Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes Byproducts and Choreography Labor and Capital Sites of Stewardship Pivot Swoop Wrinkle Superior Schematic Projections

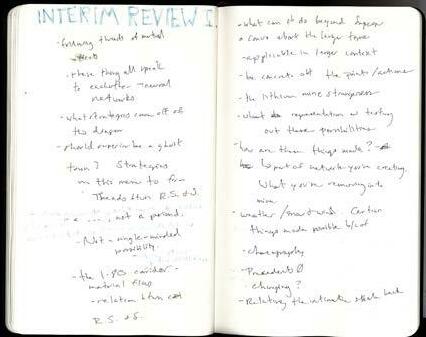

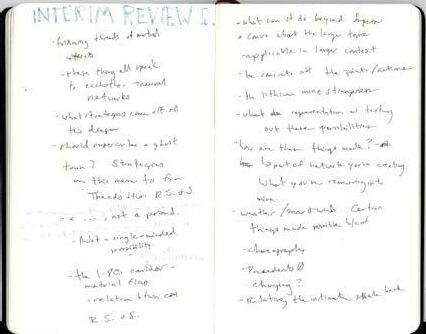

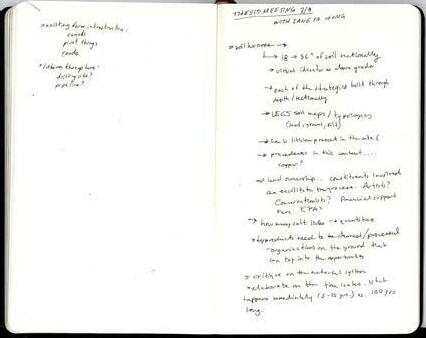

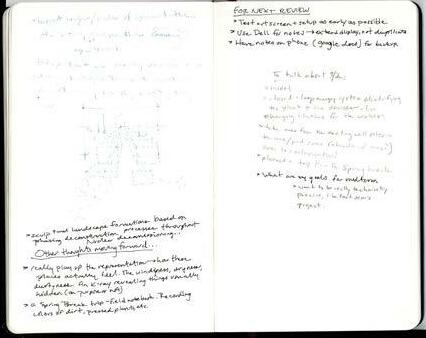

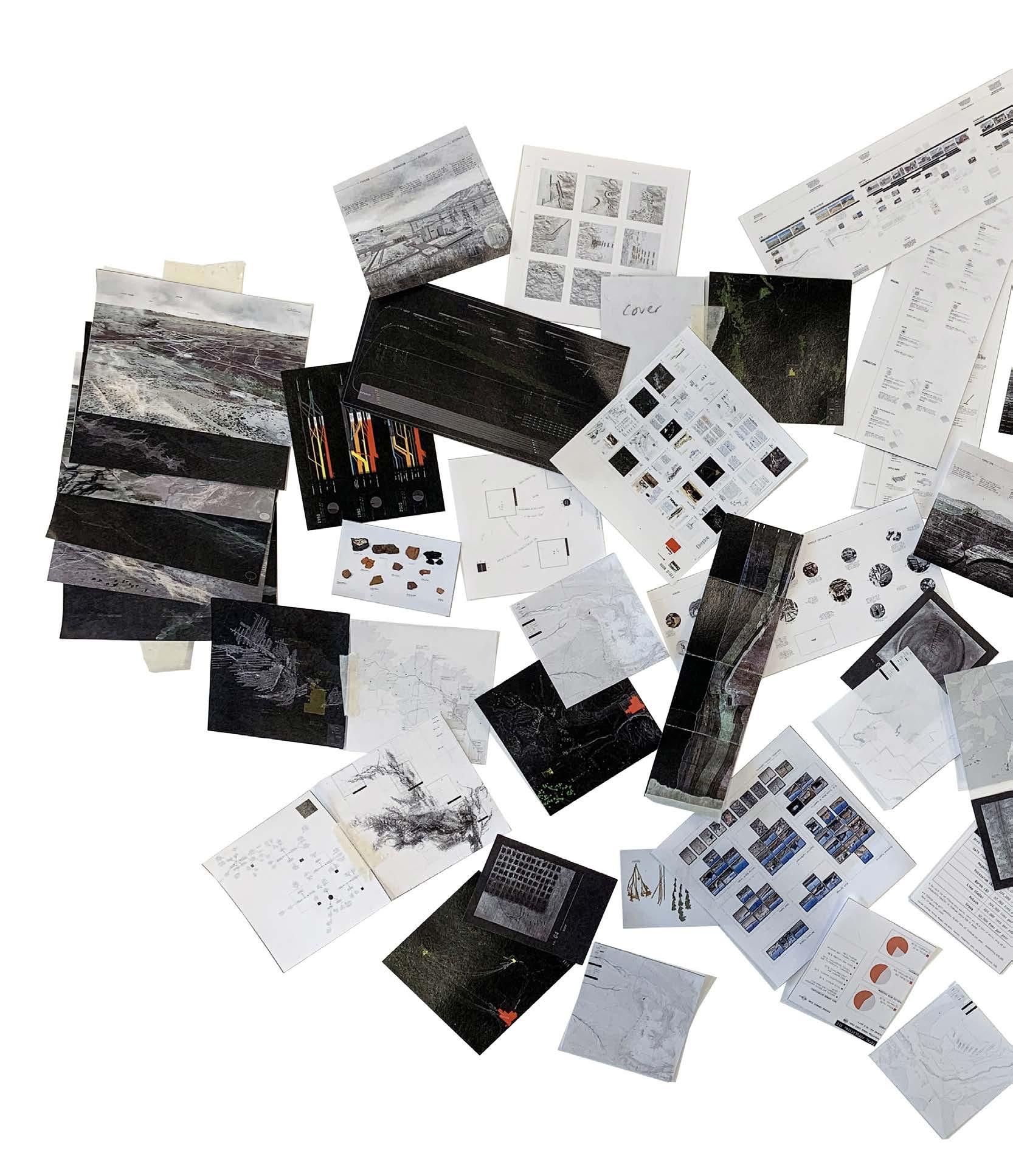

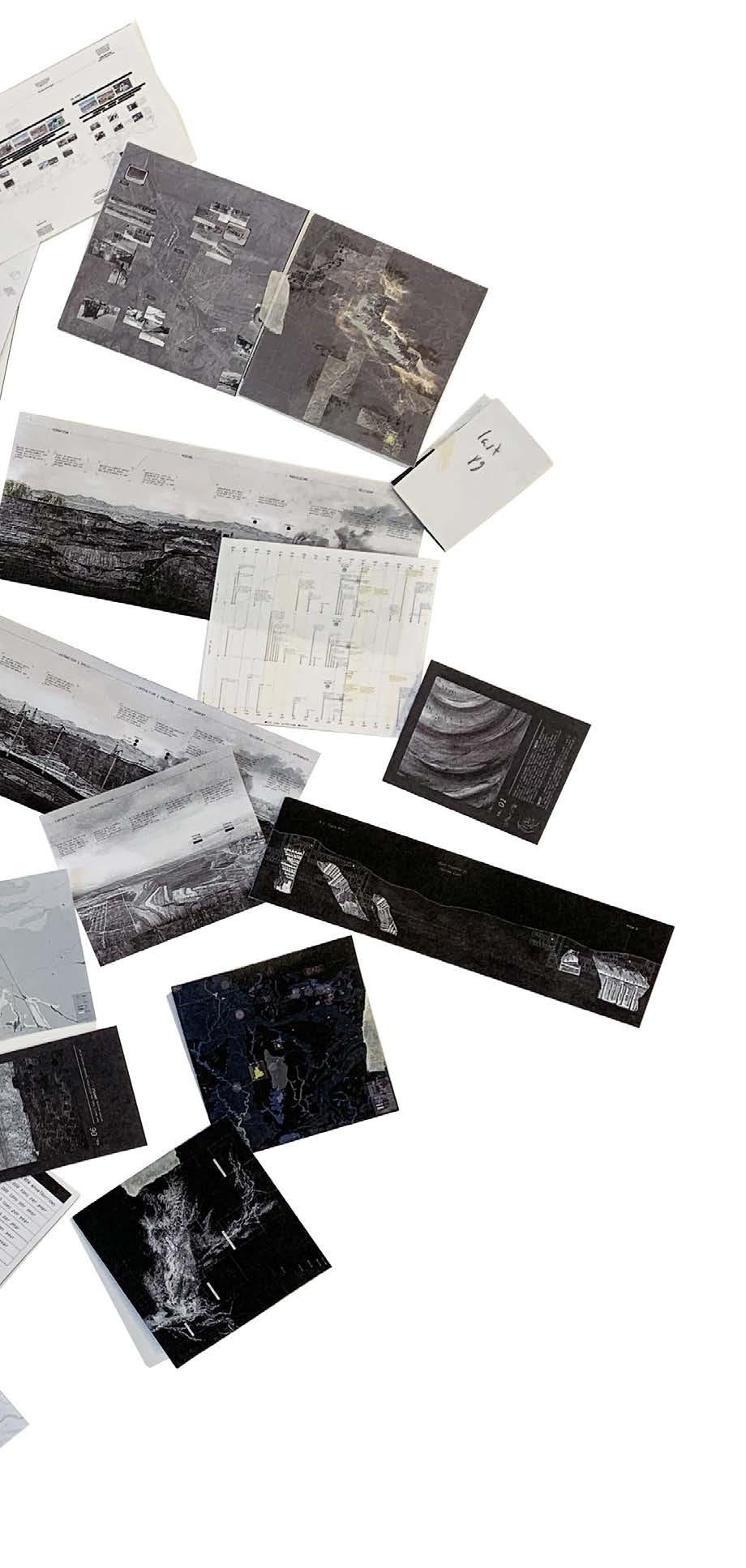

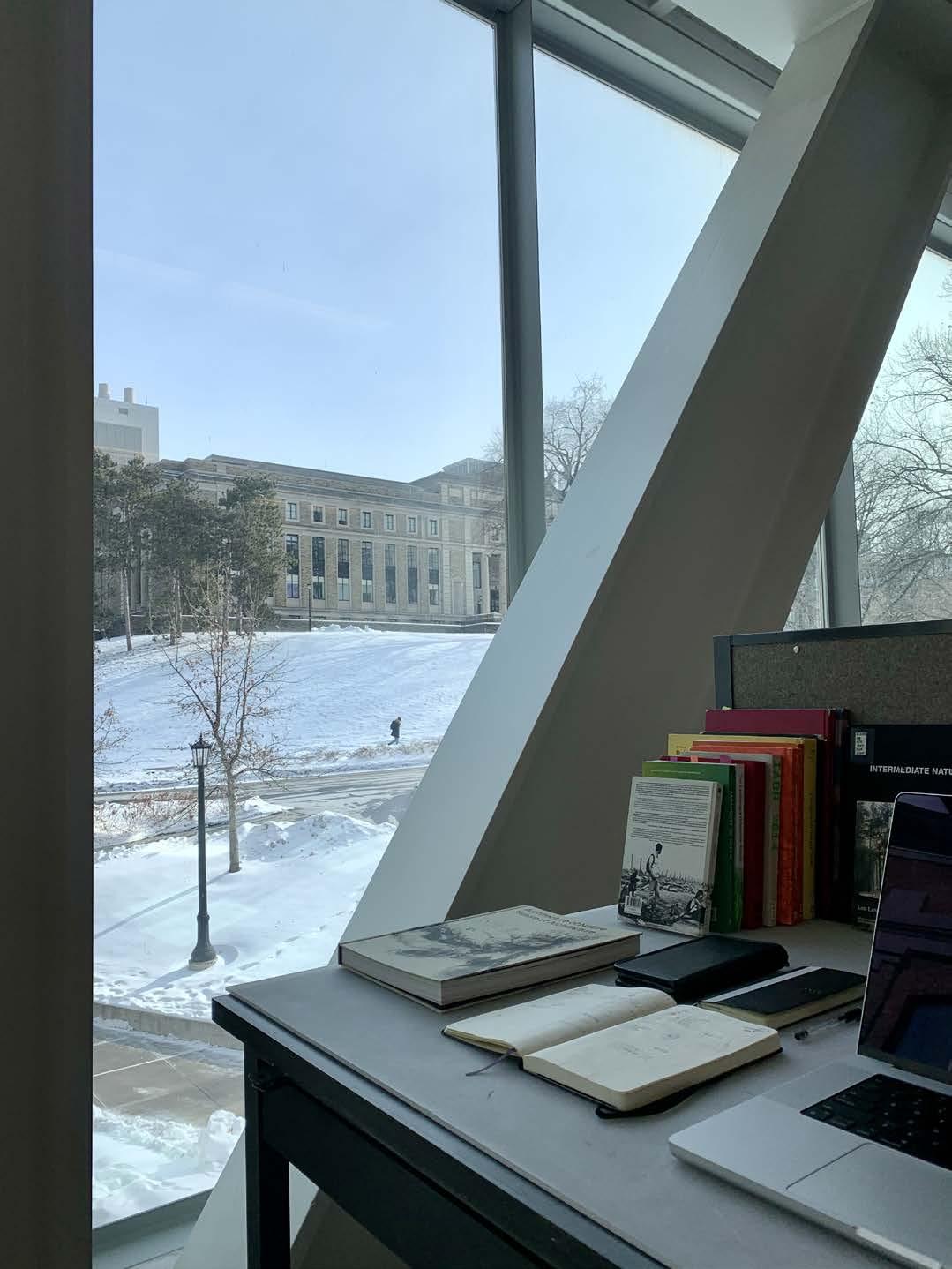

Thesis Defense

Site Fieldwork Process Bibliography

I

II

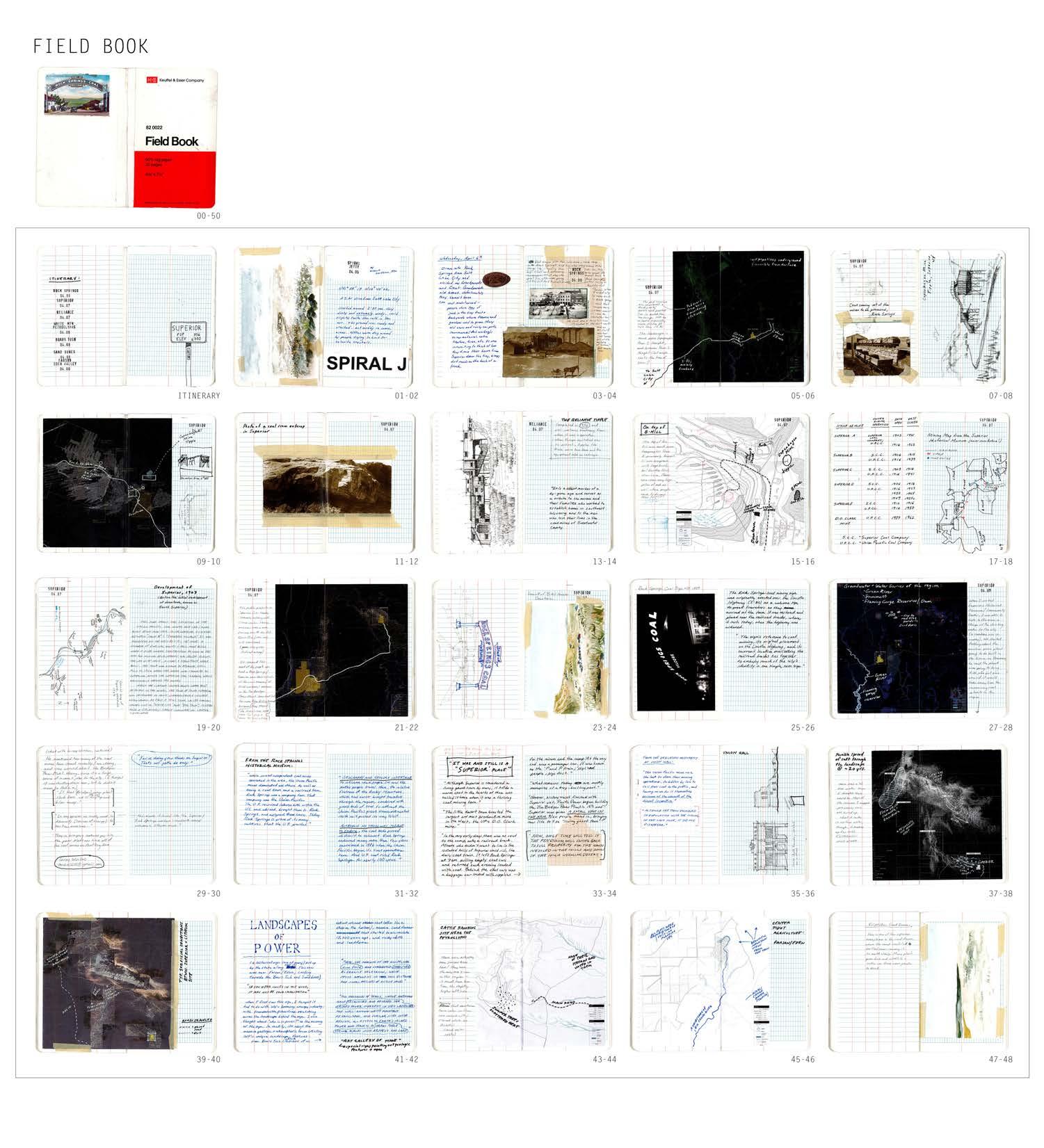

Operating in the context of a once-booming landscape of extraction, Future Afterlives of an Extractive Landscape: Sweetwater County restrategizes utilitarian extractive processes to be productive, beneficial, and remediative for the grassland ecosystem and agrarian community whose land uses will be altered by a future lithium mine. Toggling between macroscale ecological, economic, and infrastructural processes and the micro-scale human experience of stewardship, the thesis envisions an anticipatory field of revelatory landscapes whose reverberations are as much about the qualitative, perceptive experience as they are about systematization. The afterlife of an exhausted coal town has a possibility for future resurrection.

10 I

INTRODUCTION

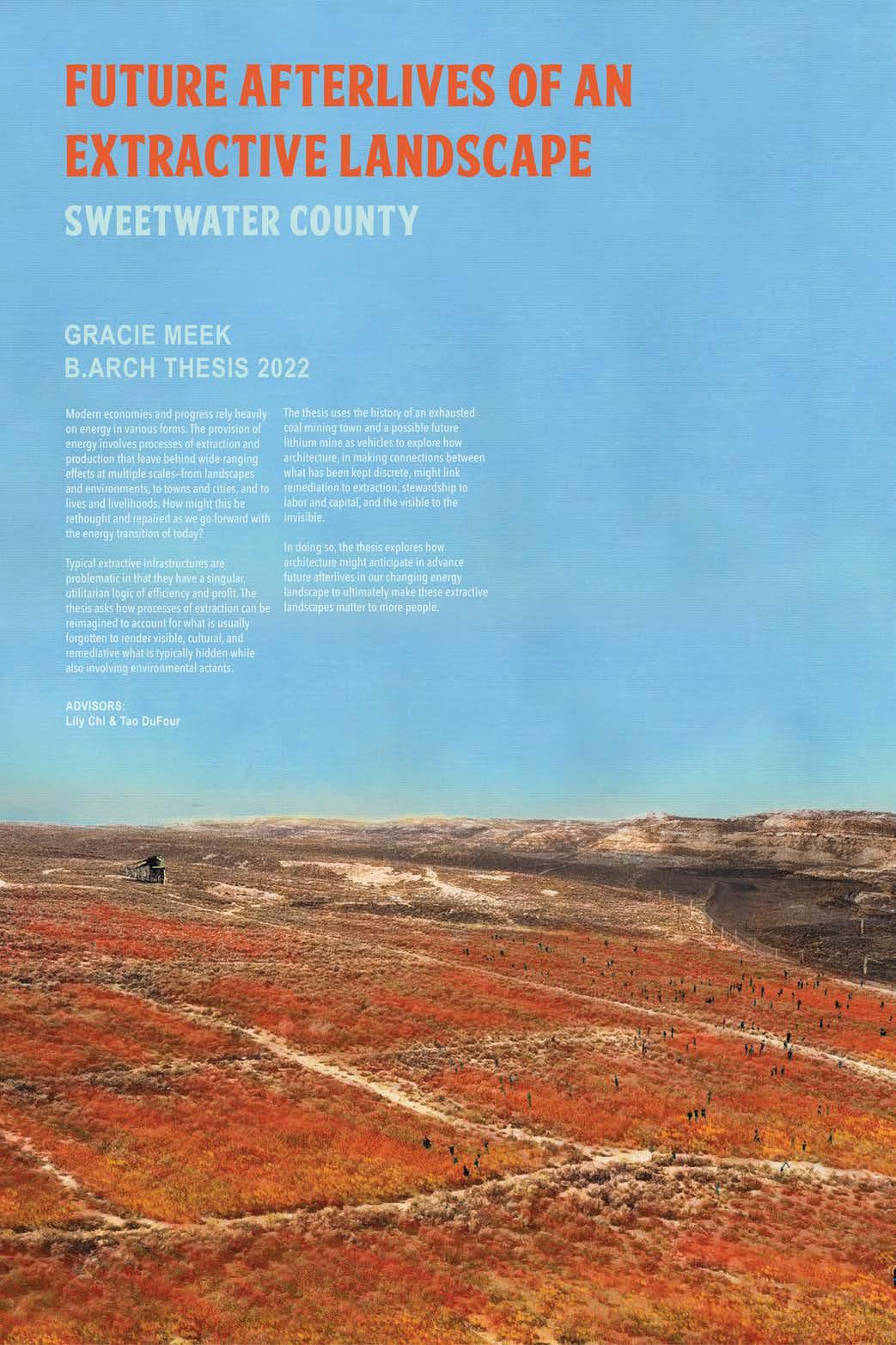

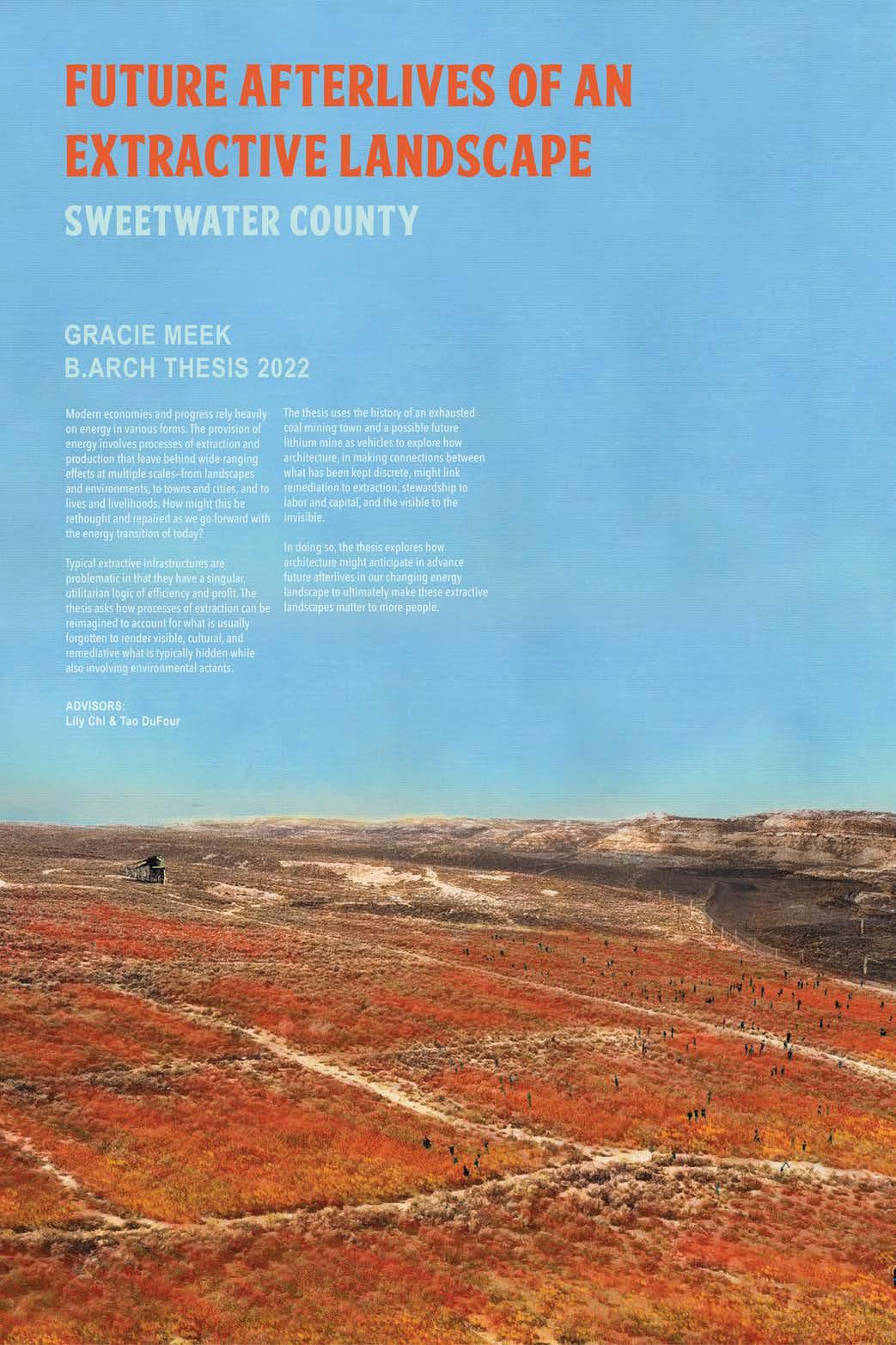

Modern economies and progress rely heavily on energy in various forms. The provision of energy involves processes of extraction and production that leave behind wide-ranging effects at multiple scales—from landscapes and environments, to towns and cities, and to lives and livelihoods. How might this be rethought and repaired as we go forward with the energy transition of today?

Typical extractive infrastructures are problematic in that they have a singular, utilitarian logic of efficiency and profit. Future Afterlives of an Extractive Landscape: Sweetwater County asks how processes of extraction can be reimagined to account for what is usually forgotten to render visible, cultural, and remediative what is typically hidden while also involving environmental actants.

The thesis uses the history of an exhausted coal mining town and a possible future lithium mine as vehicles to explore how architecture, in making connections between what has been kept discrete, might link remediation to extraction, stewardship to labor and capital, and the visible to the invisible.

In doing so, the thesis explores how architecture might anticipate in advance future afterlives in our changing energy landscape to ultimately make these extractive landscapes matter to more people.

11 I Introduction

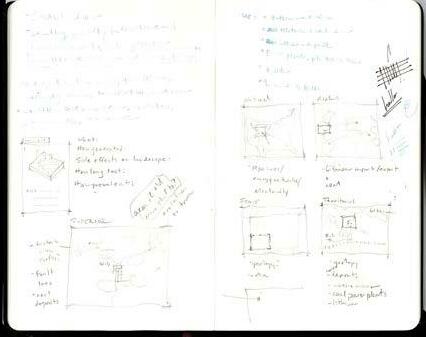

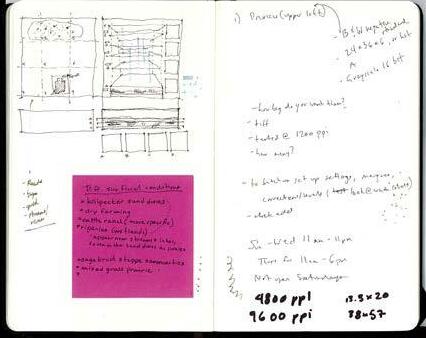

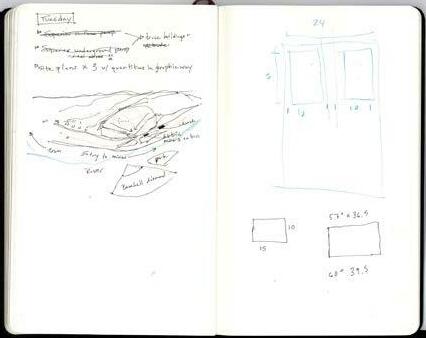

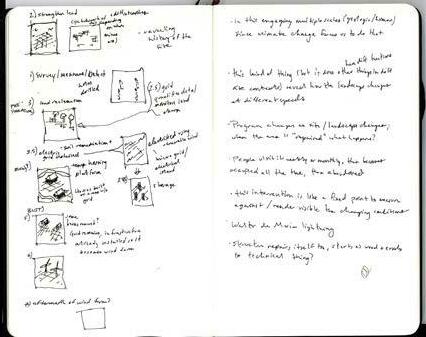

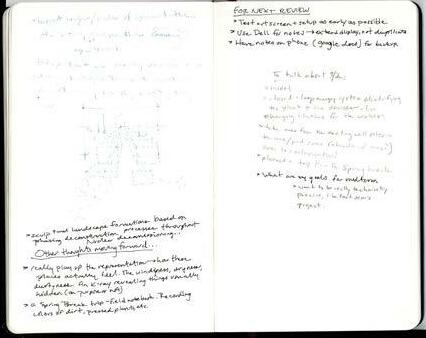

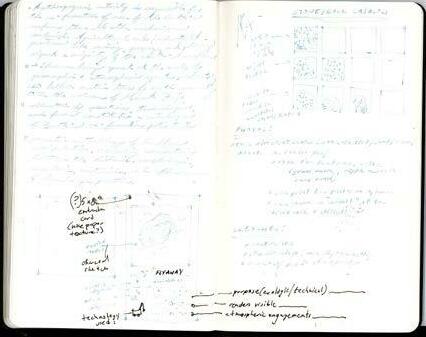

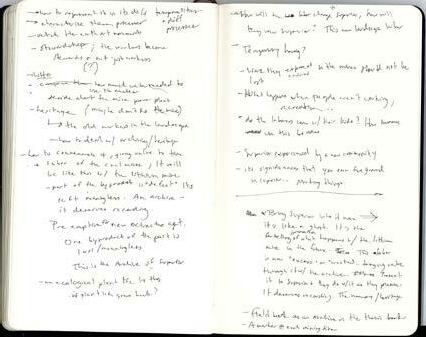

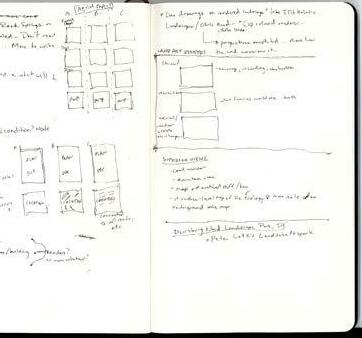

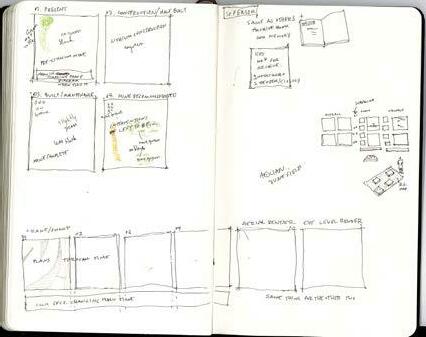

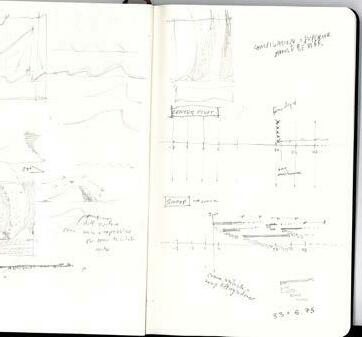

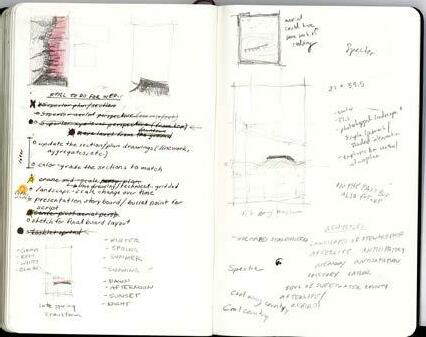

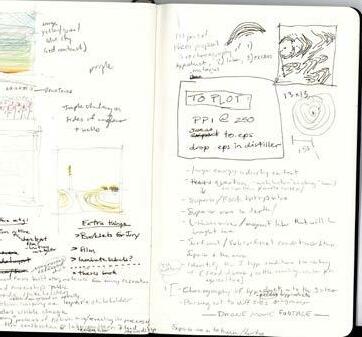

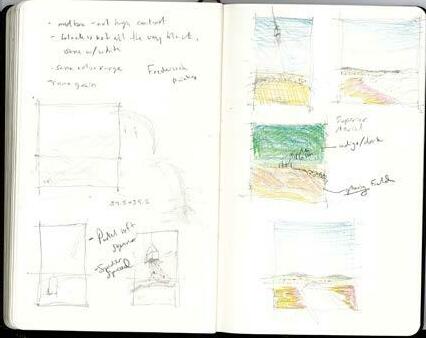

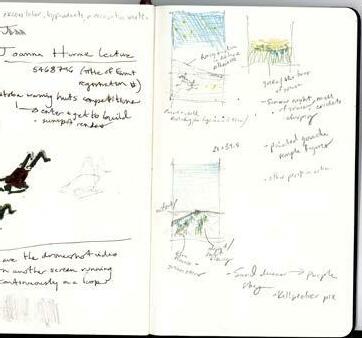

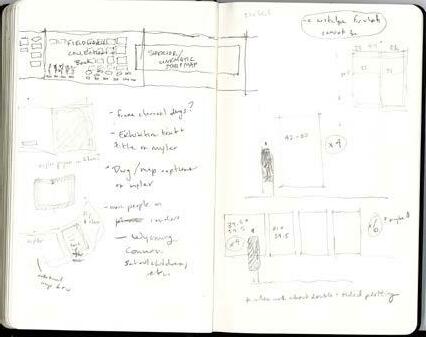

The original thesis proposal from Fall 2021 centered around creating remediative, hybrid charging stations for electric vehicles. While the large-scale concept of today’s energy transition implications remained the focus of the thesis, charging infrastructure was set aside to prioritize possible future afterlives of electrification.

12 II

PROPOSAL

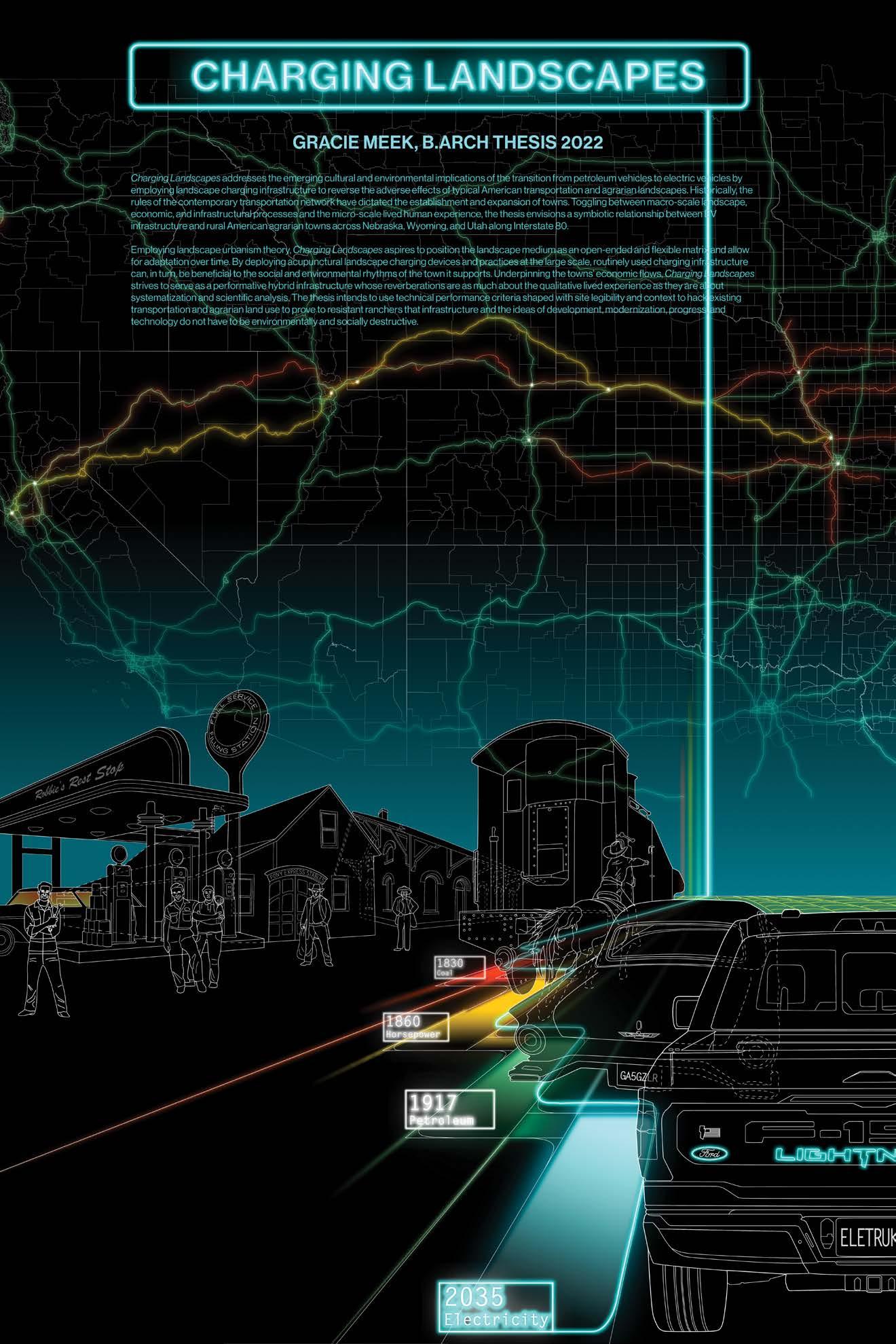

Charging Landscapes

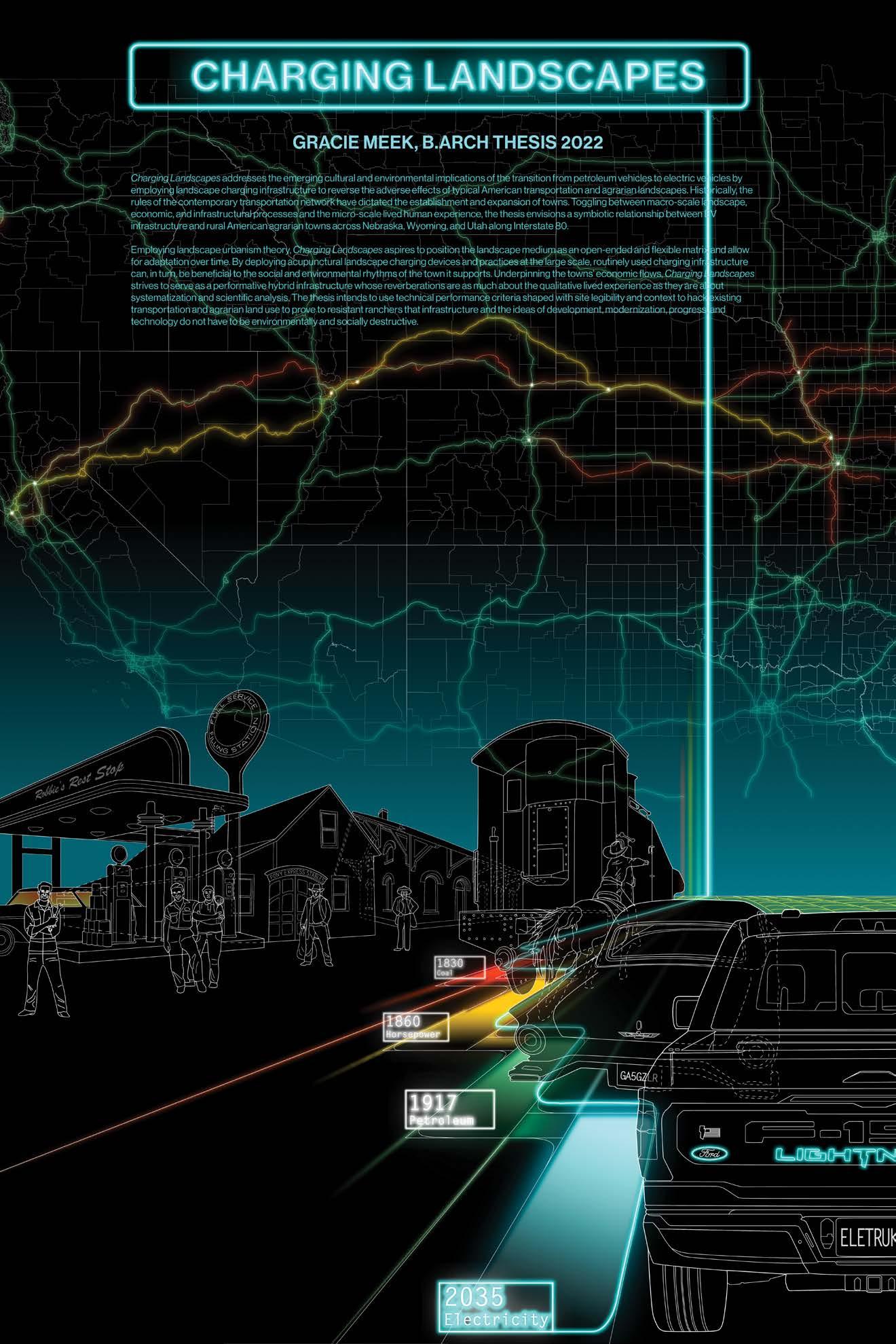

Charging Landscapes addresses the emerging cultural and environmental implications of the transition from petroleum vehicles to electric vehicles by employing landscape charging infrastructure to reverse the adverse effects of typical American transportation and agrarian landscapes. Historically, the rules of the contemporary transportation network have dictated the establishment and expansion of towns. Cities and transportation systems concurrently evolved socially, economically, and environmentally through transit oriented development (TOD) schemes. With GM’s transitioning out of gas and diesel engines by 2035, the Biden administration’s infrastructure bill providing $7.5 billion in federal grants to build a national network of charging infrastructure, and, closer to home, TCAT’s addition of seven electric busses to their fleet, America begins its transition to a “manifest destiny-esque” electrified landscape. The role of public infrastructure in our cities and towns is changing.

Making EV ownership the standard can be achieved only when charging infrastructure is available throughout the country and strategically placing it to make electric transportation to and from any point within the continental US a reality. However, with already overburdened rural electrical grids intensified due to climate change, the lack of charging stations along remote longhaul routes in the Great Plains causing “range anxiety,” and the ineffective setup of rest stops to support the wait for a car to charge, rural towns are confronted with the task of catching up with larger cities to make EVs accessible to everyone. An allinclusive approach is the only way to establish a completely interconnected electric road map throughout the country.

13 II Proposal

Toggling between macro-scale landscape, economic, and infrastructural processes and the micro-scale lived human experience, the thesis envisions a symbiotic relationship between EV infrastructure and rural American agrarian towns across Nebraska, Wyoming, and Utah along Interstate 80. These towns historically emerged as pit stops along the Oregon Trail, Union Pacific Railroad, Pony Express, and US Highway System. Presently, the road network facilitates access to vast cattle and sheep ranch lands, national trucking of agricultural products grown nearby, and the export of coal. But, it is also where a freshly licensed teen driver aimlessly cruises to express her newfound freedom and where families embark on long distance trips to cross the Rocky Mountains. Landscape becomes the vehicle by which to articulate solutions for the integration of EV infrastructure with practical programming that can address not only the needs of the everyday agricultural community but also the grassland ecosystem.

Employing landscape urbanism theory, Charging Landscapes aspires to position the landscape medium as an open-ended and flexible matrix and allow for adaptation over time. By deploying acupunctural landscape charging devices and practices at the large scale, routinely used charging infrastructure can, in turn, be beneficial to the social and environmental rhythms of the town it supports. Underpinning the towns’ economic flows, Charging Landscapes strives to serve as a performative hybrid infrastructure whose reverberations are as much about the qualitative lived experience as they are about systematization and scientific analysis. The thesis intends to use technical performance criteria shaped with site legibility and context to hack existing transportation and agrarian land use to prove to resistant ranchers that infrastructure and the ideas of development, modernization, progress, and technology do not have to be environmentally and socially destructive.

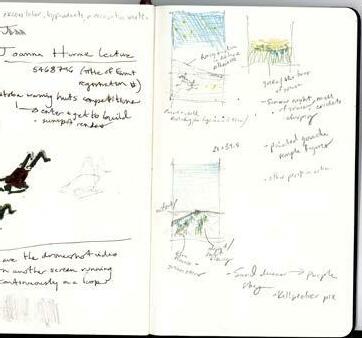

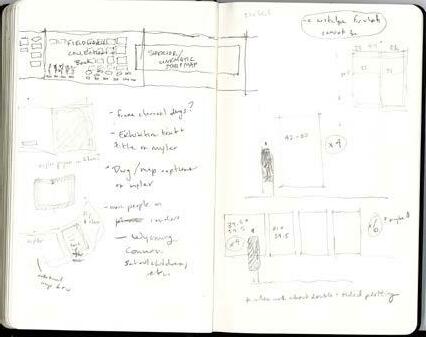

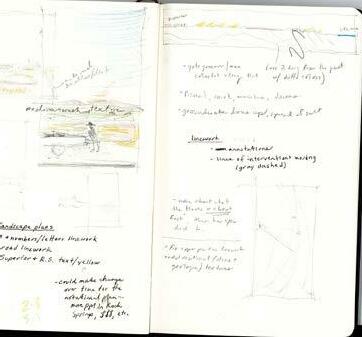

Original Thesis Proposal, November 2021

14

15 II Proposal

16

PHASE I

17

After encouragement in the initial thesis meeting to “not be too optimistic” about electrification, research about the implications of the energy industry including resource extraction and battery production was conducted.

18 III

ENERGY SOURCE ANALYSES

The Afterlives of Extractive Infrastructures and Future Afterlives of “Green” Energy

Initial research on today’s transition from fossil fuel derived energy to electrification revealed that renewables are not as “green” as they may seem. Electrification is generally seen as a positive, as the consequences of the combustion of coal and other fossil fuels like oil and gas extracted for energy production have dire social and environmental outcomes. Wild boom and bust economic swings and airborne, surficial, and groundwater pollution only scratch the surface when it comes to consequences of nonrenewable extraction. Additionally, possible solutions for “cleaner” energy production, like nuclear fission, fail to deal with wast which will remain toxic for thousands of years.

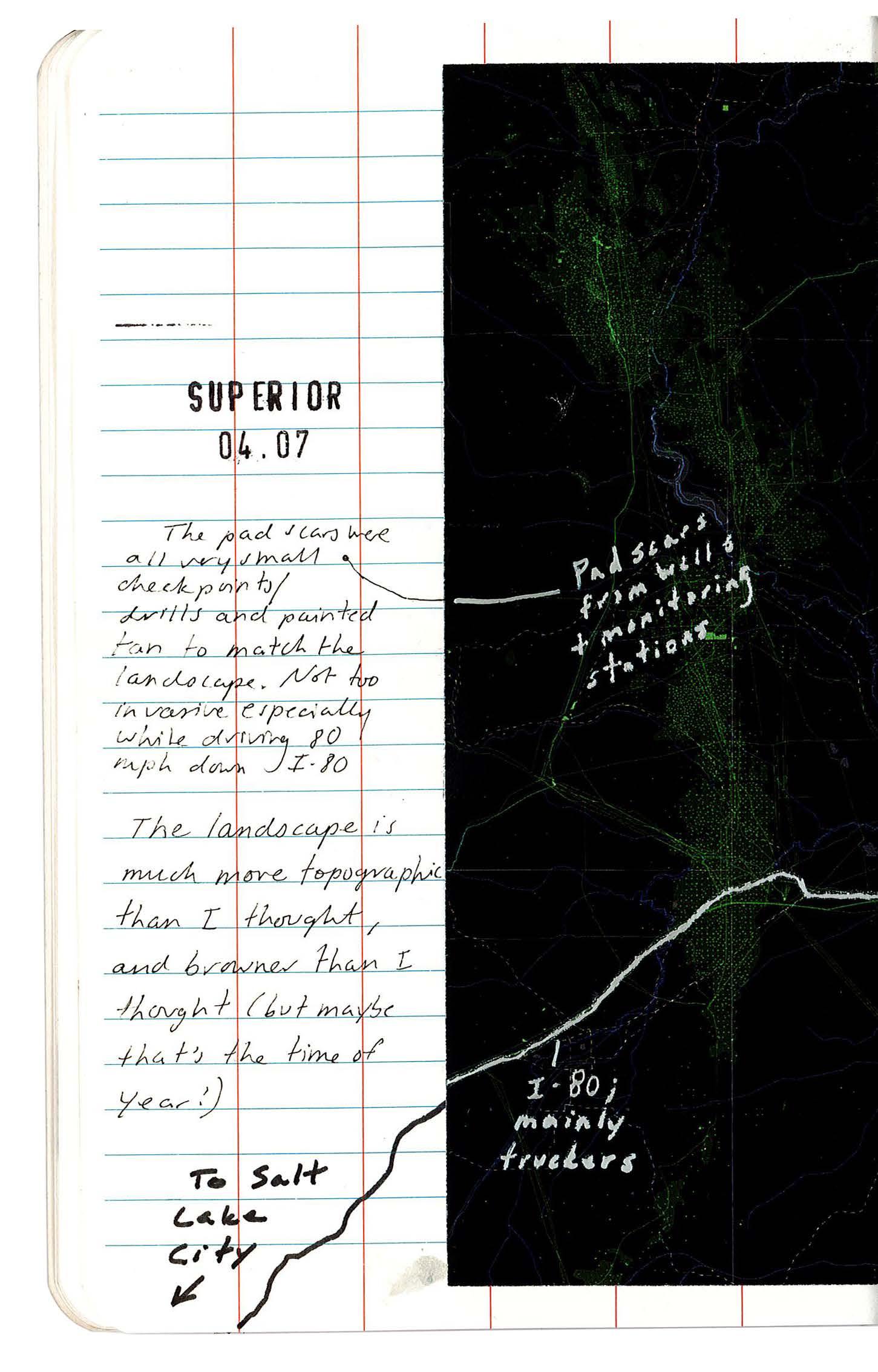

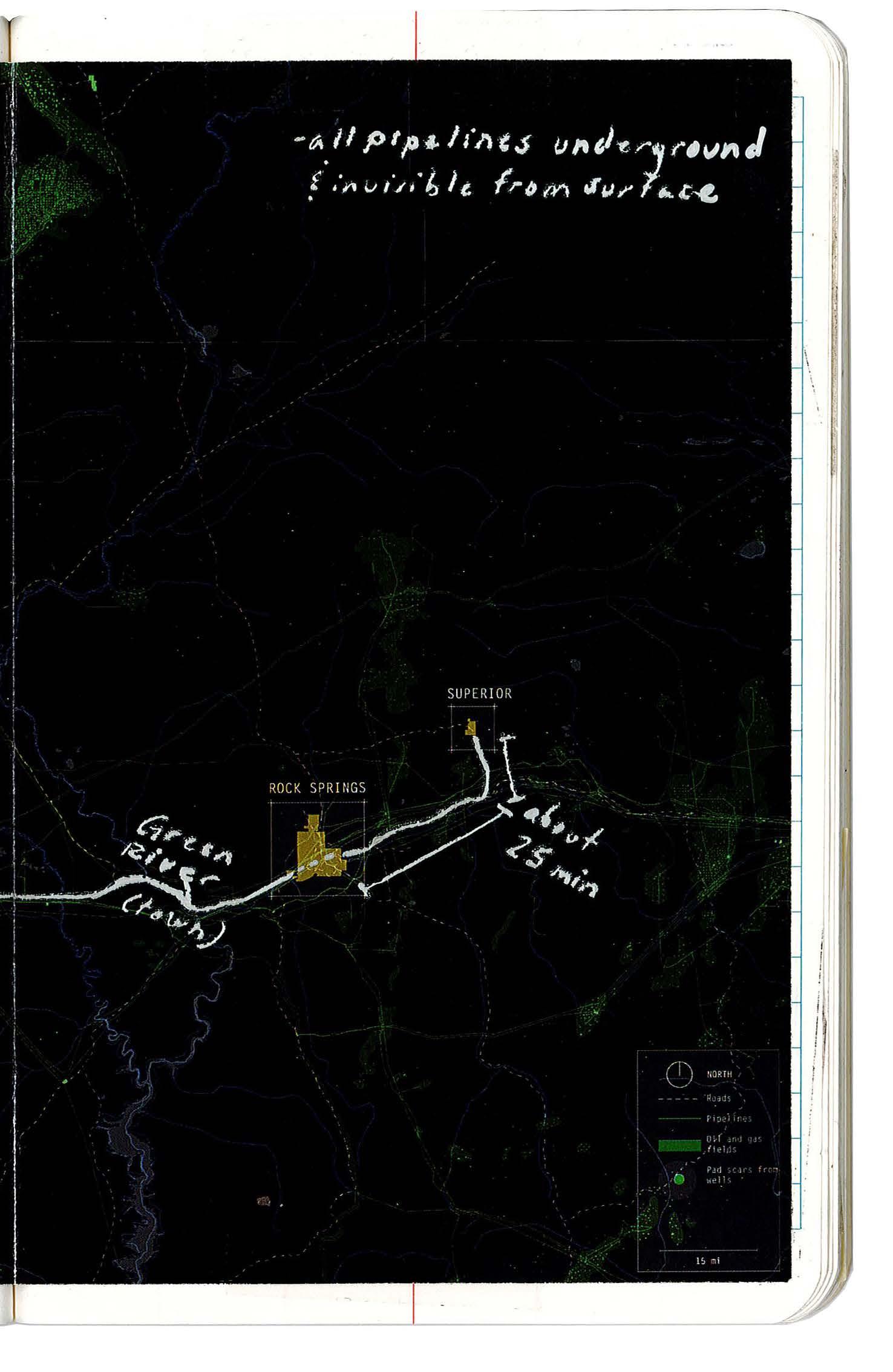

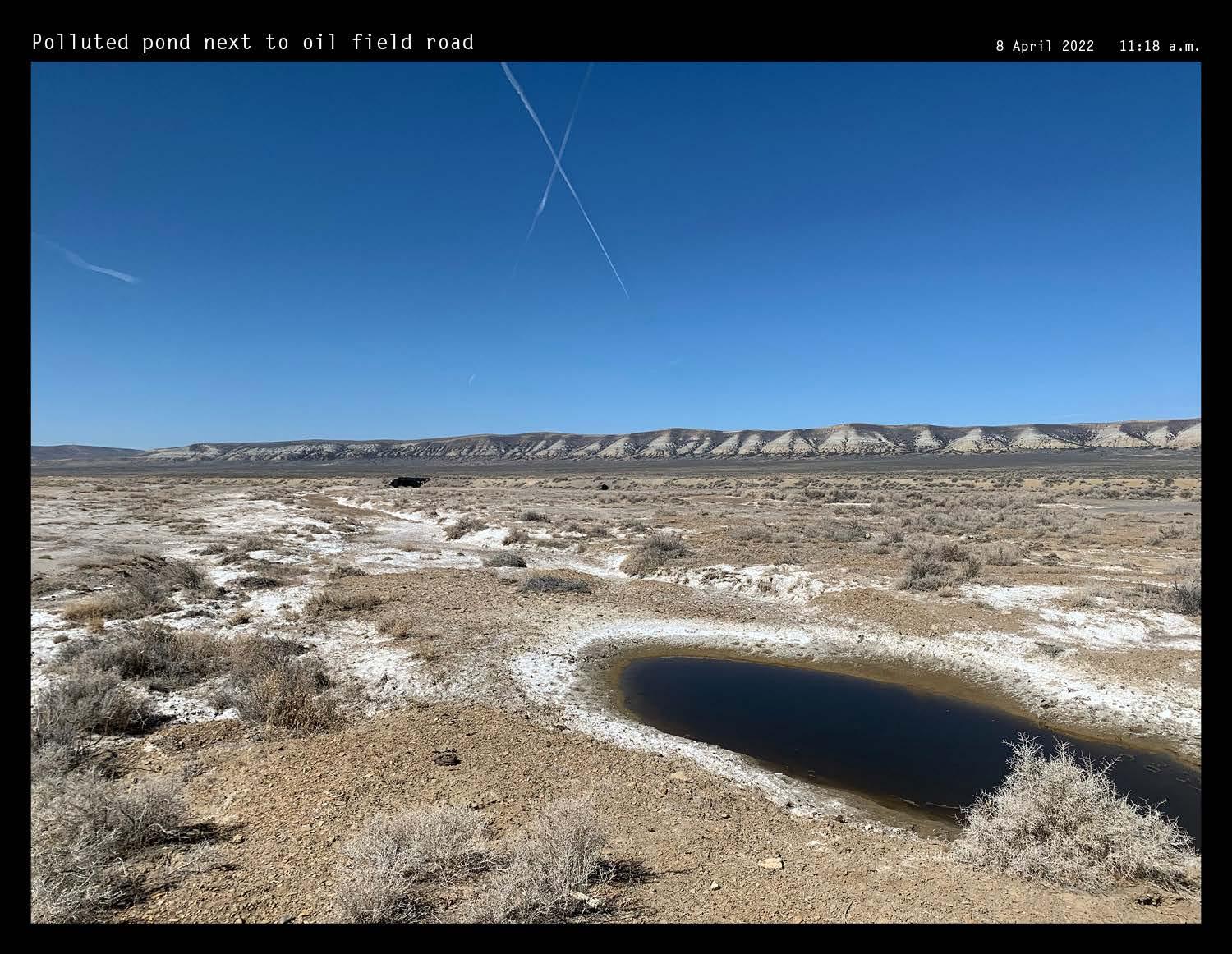

Typical extractive infrastructure is problematic in that it isolates functions, processes, and byproducts in an entirely utilitarian approach that is only interested in “efficiency” and profit. These infrastructures are hidden from the public eye, for instance, oil pipelines buried underground, or oil wells painted tan to blend in with the landscape. The thesis restrategizes these threads to render visible, cultural, and remediative that which is normally hidden while also involving environmental actants.

The thesis does not propose the adoption of the electrification of cities as a neutral or as a solution. The thesis takes this adoption as a fact. It has implications. So, rather, how can architects anticipate problems that may arise with the energy transition in the future to identify, measure, expose, and repair the traces left by past energy systems while working in conjunction with the energy transitions and operations of the present?

19

III Energy Source Analyses

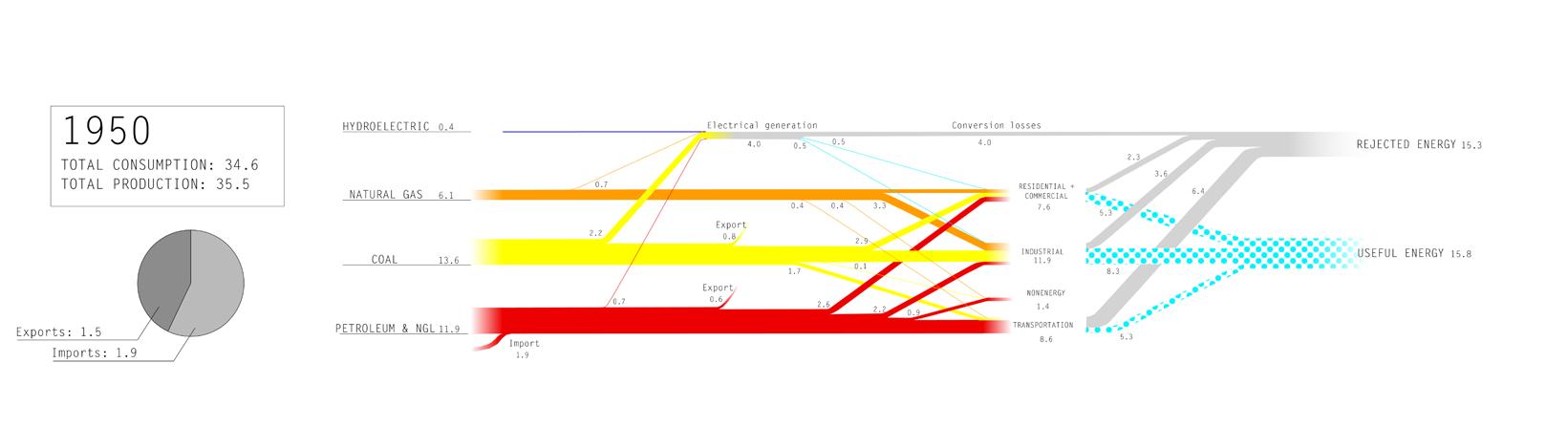

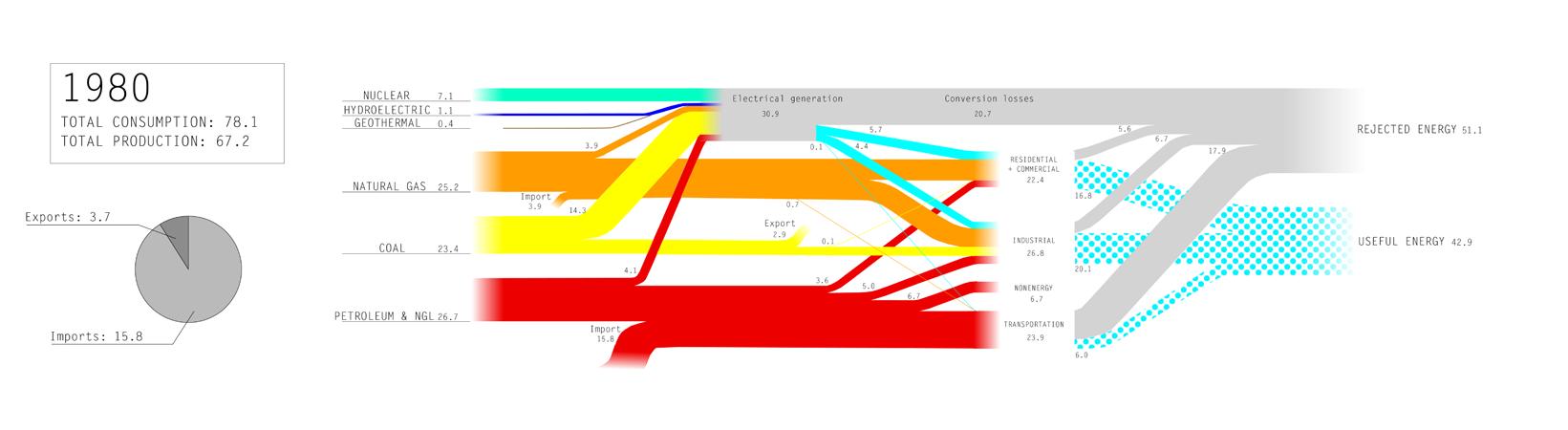

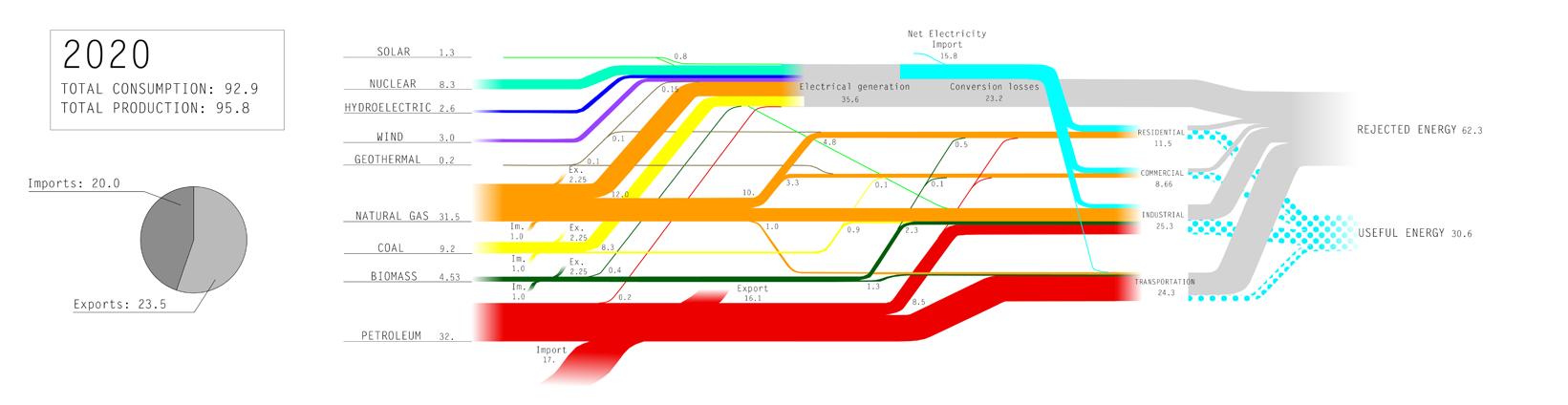

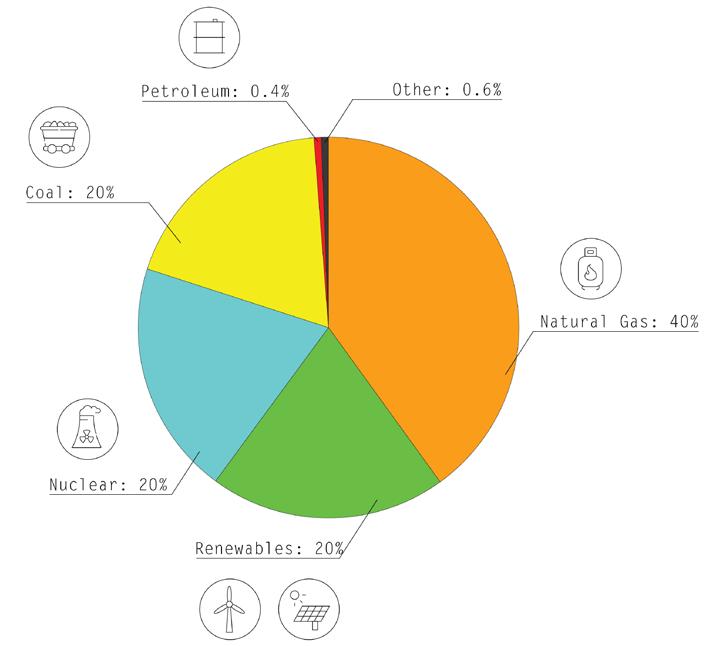

20 Data

from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, US Department of Energy, and US Energy Information Administration

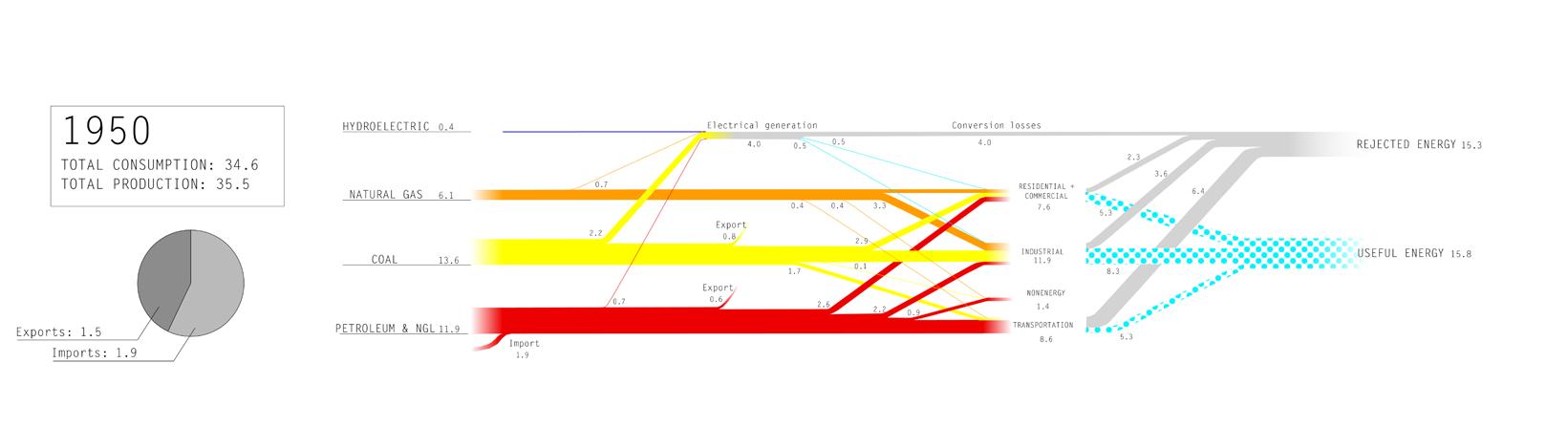

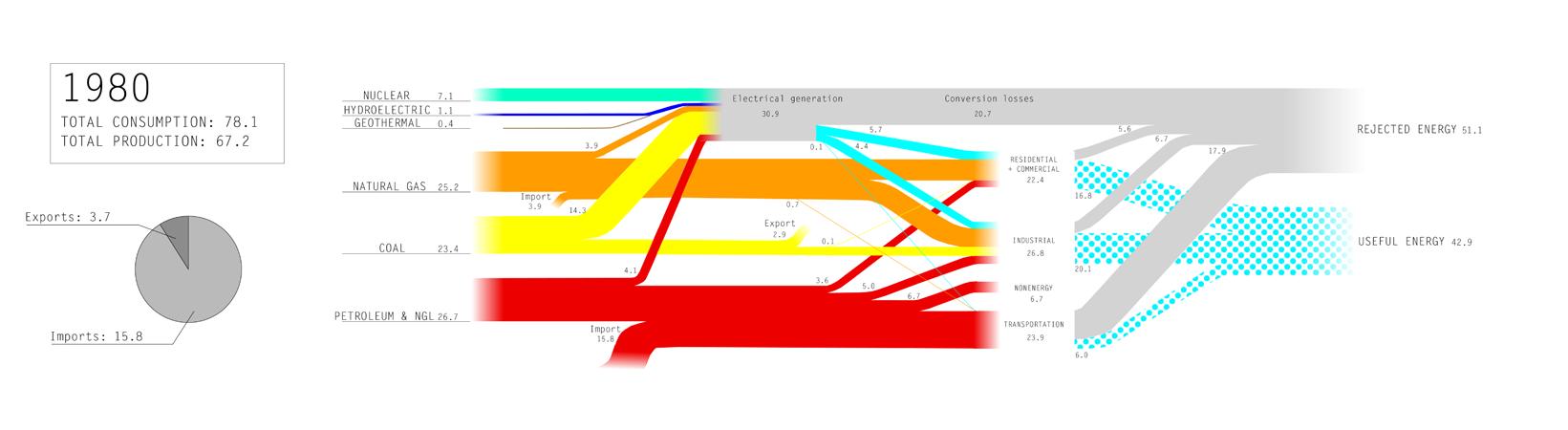

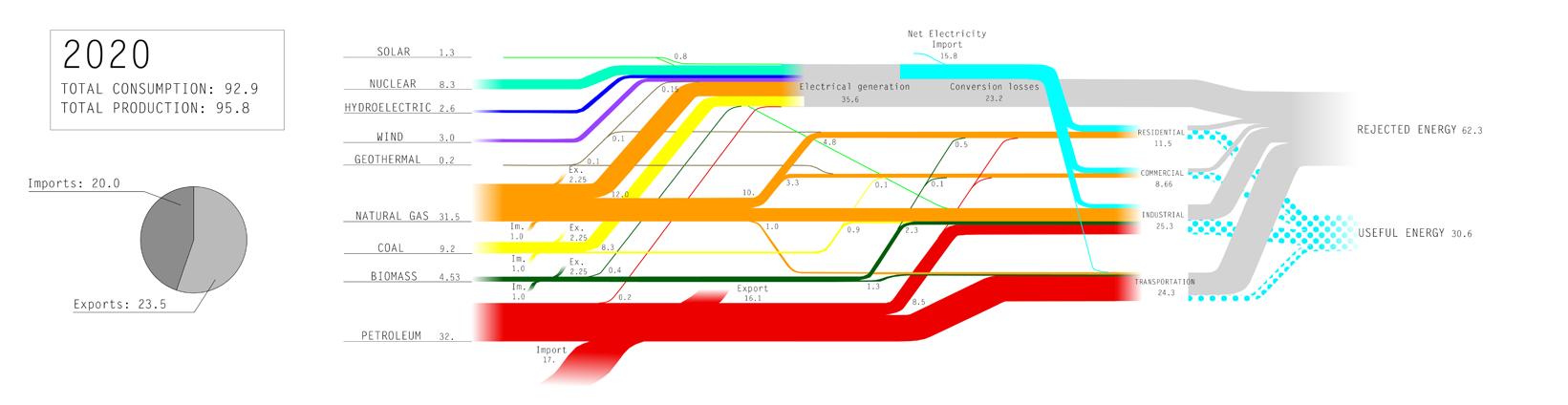

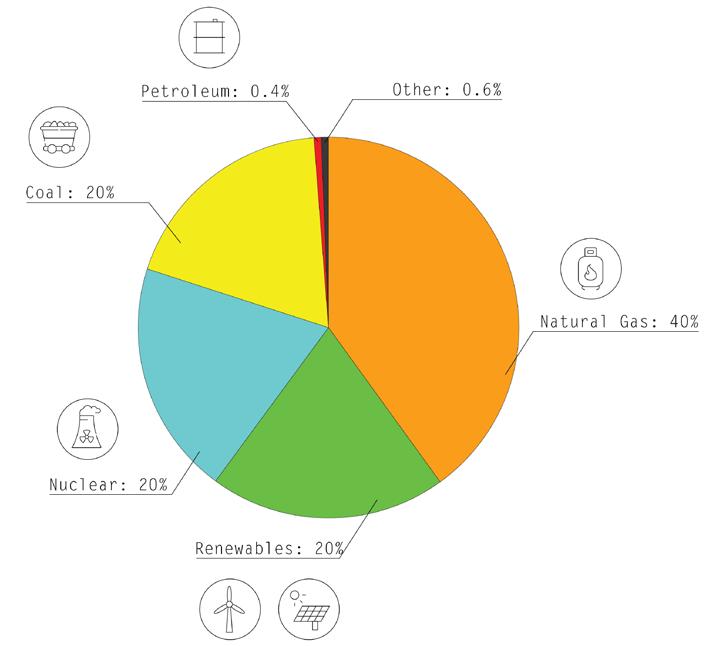

TYPES OF ENERGY, CONVERSION LOSSES, AND THEIR USABLE FLOWS IN THE US FROM 1950–PRESENT

The energy flow diagram on the left shows how the US creates energy, where the energy goes, and how much is wasted. The ineffective conversion of energy from raw materials throughout history resulted in a considerable loss of potential energy. As of 2020, the US is a net exporter of energy for the first time since 1952. The past ten years have seen a significant decline of coal extraction for energy production (yellow) with renewables slowly gaining traction.

Measurements in 1 quadrillion BTU (British Thermal Units: the amount of energy needed to heat 1 pound of water by 1 degree F), equal to 36,000,000 lbs of coal

21 III Energy Source Analyses

22 Geologic information from: (Hallman 2010)

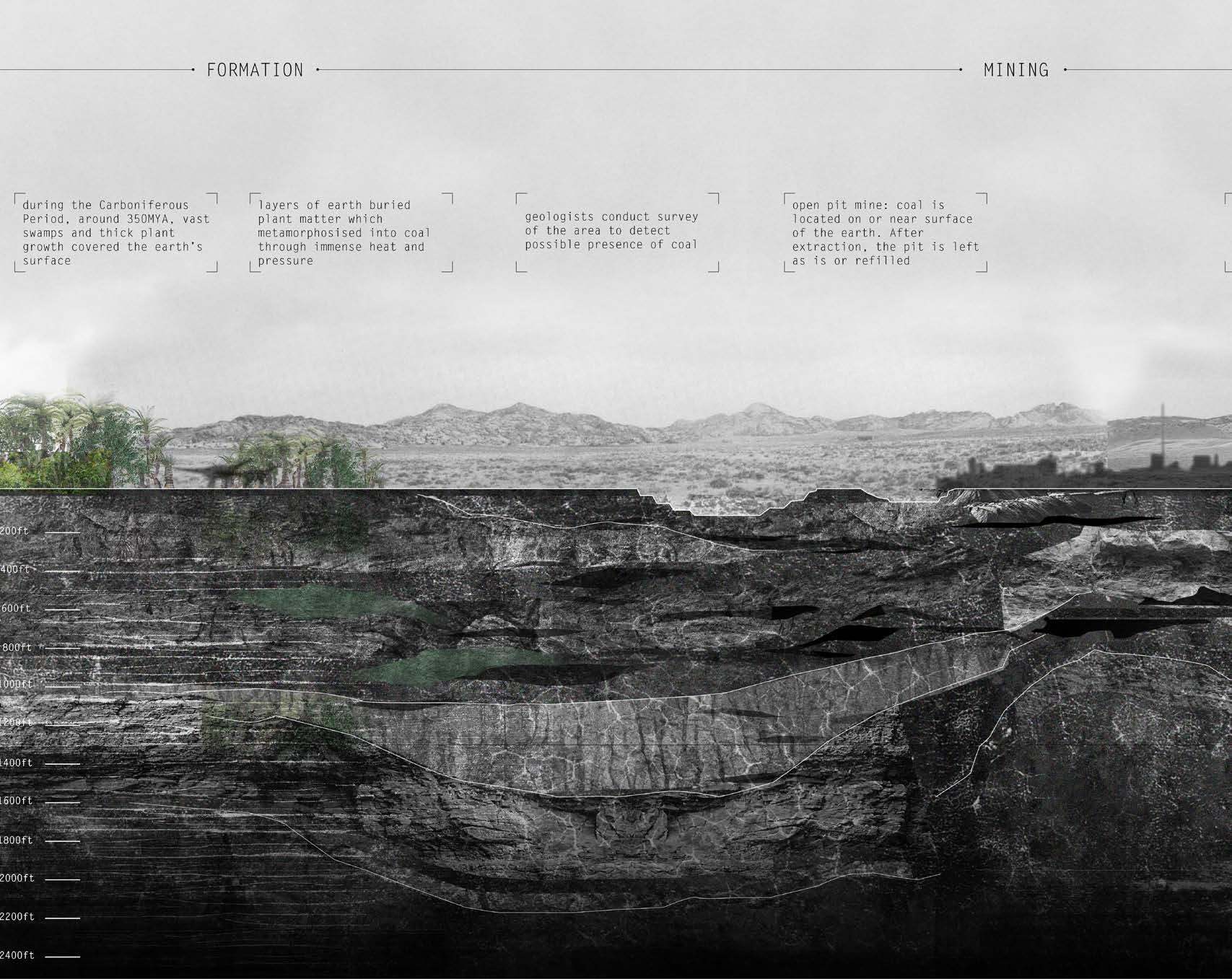

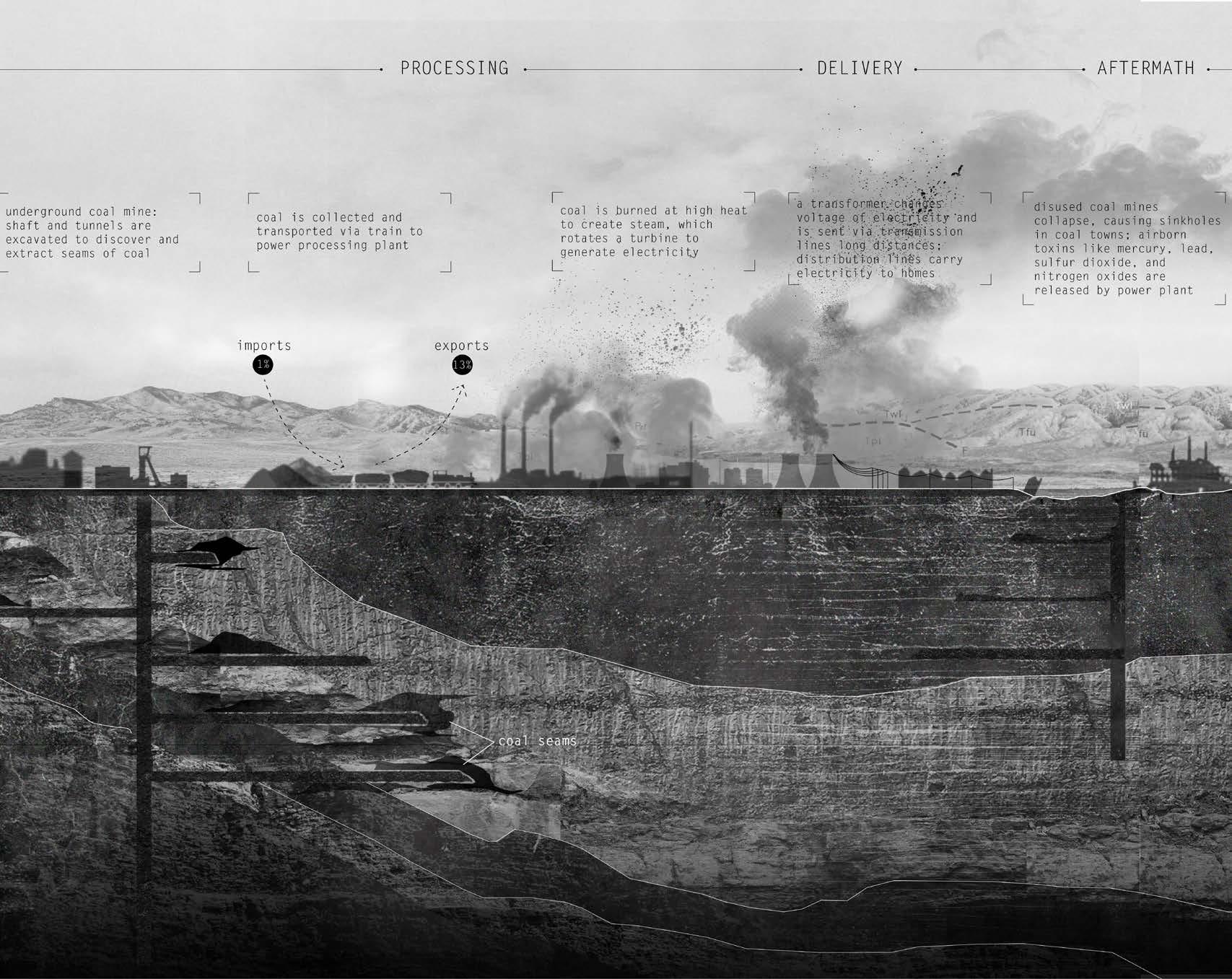

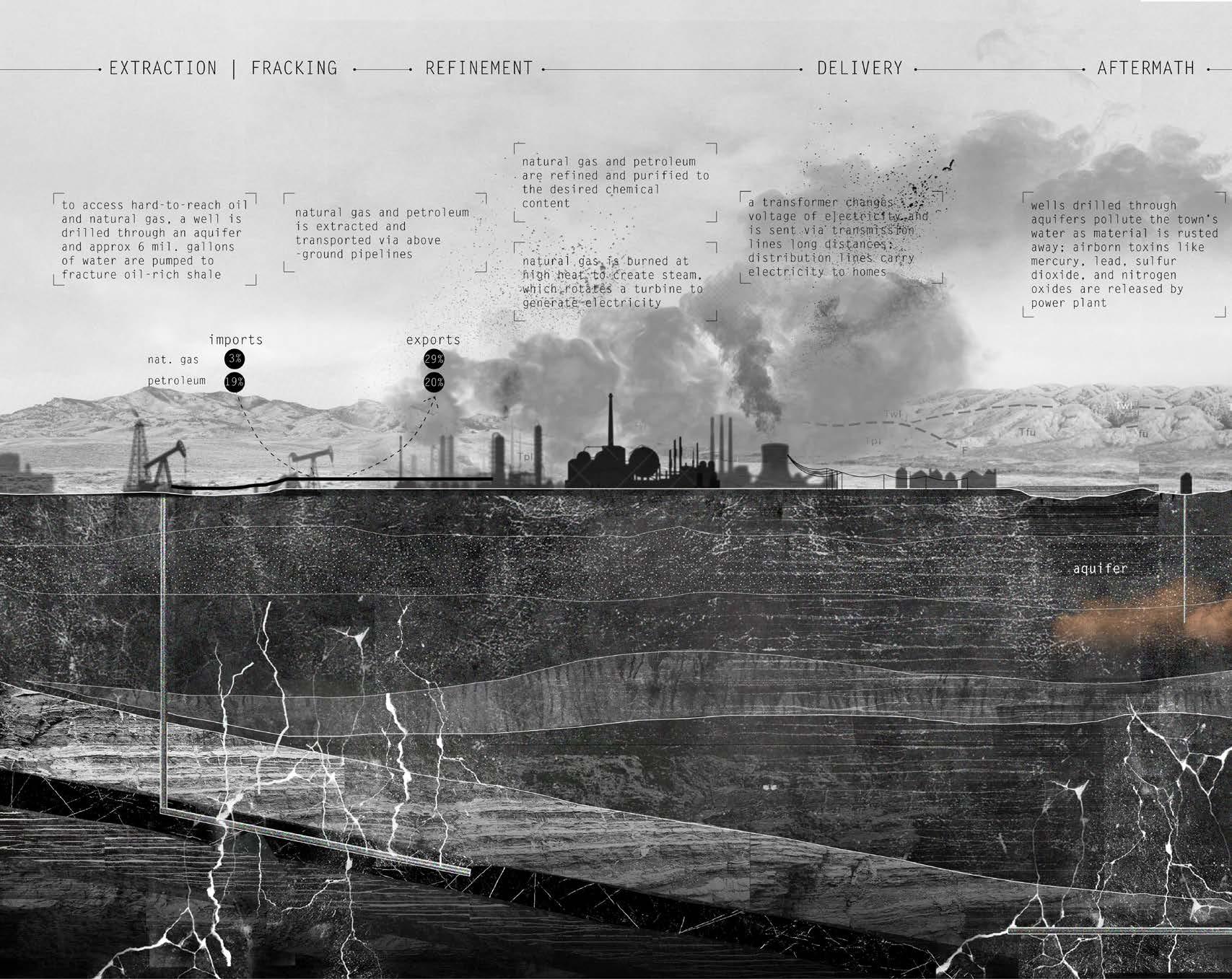

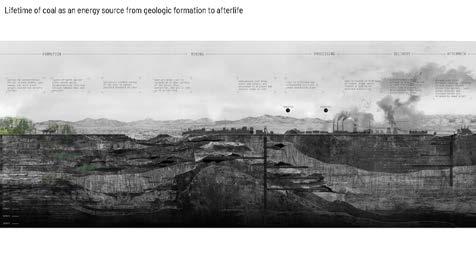

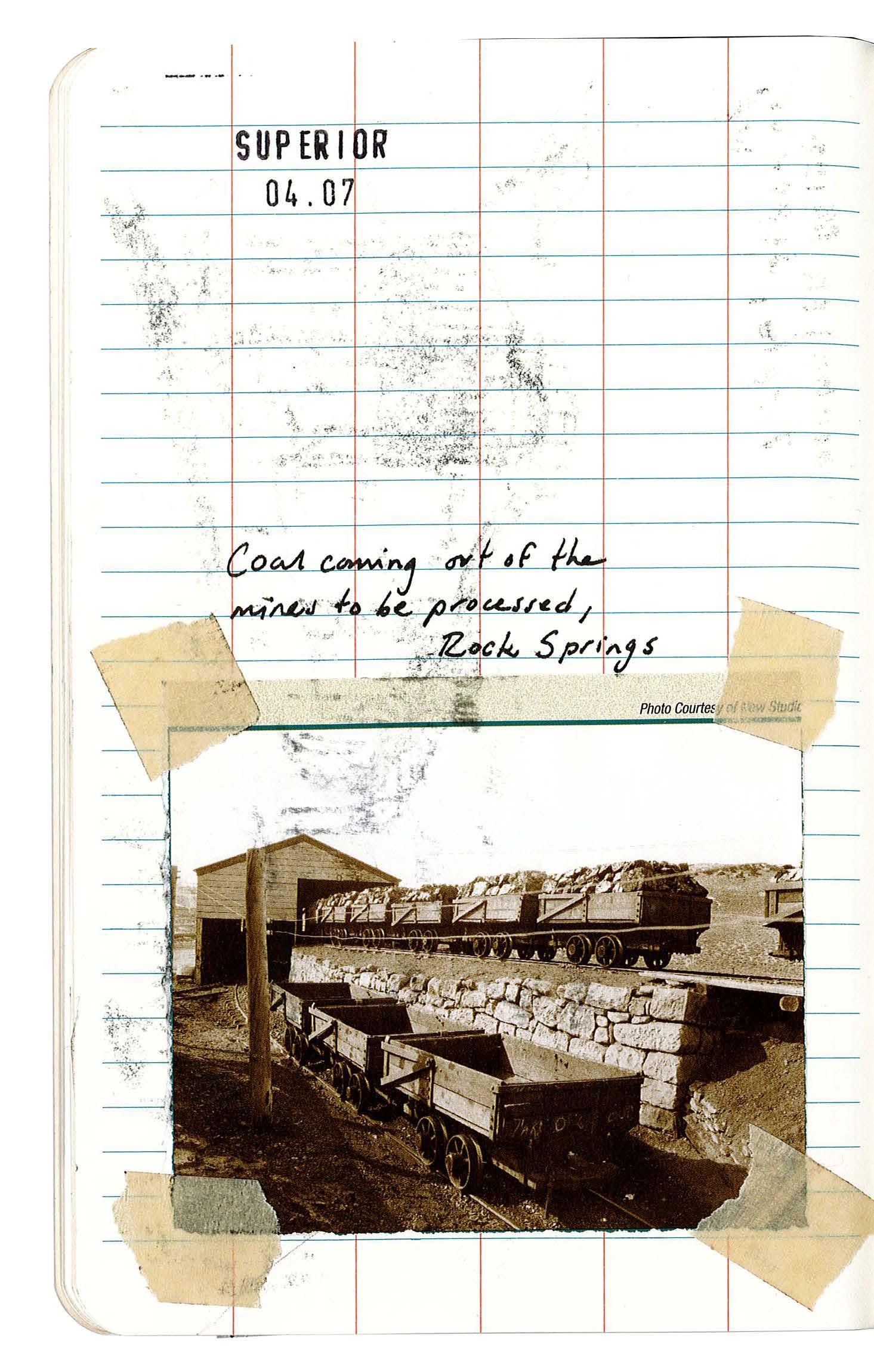

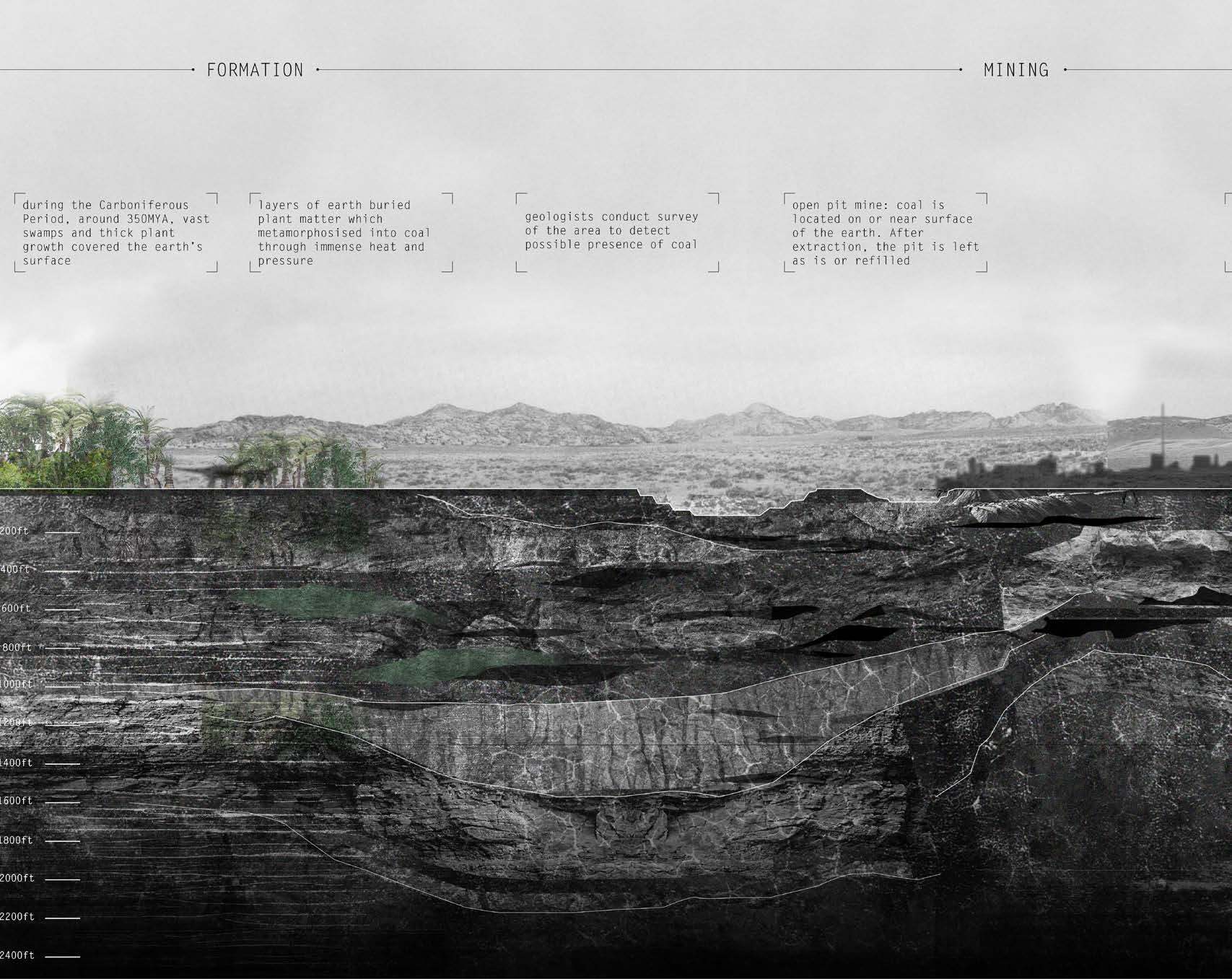

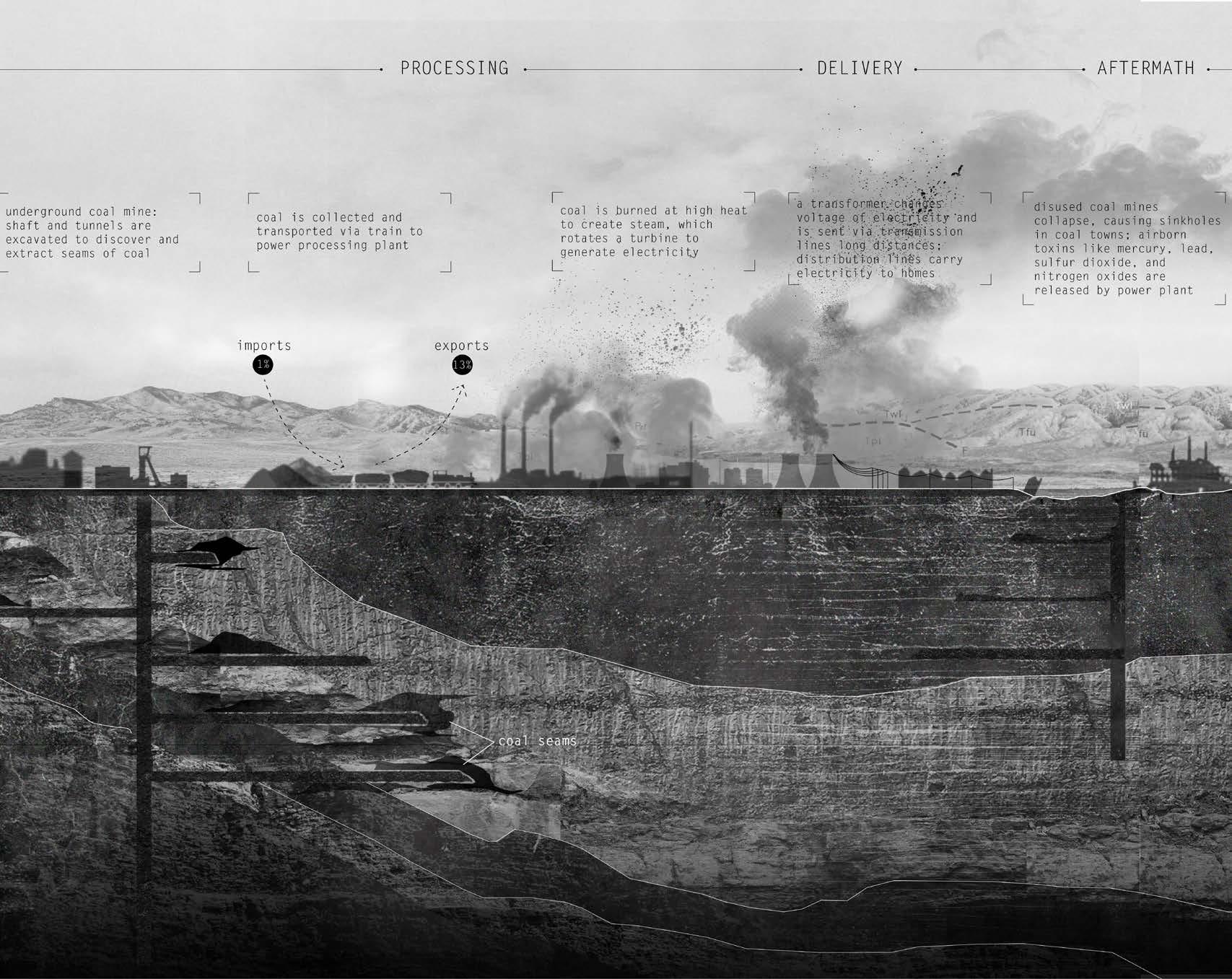

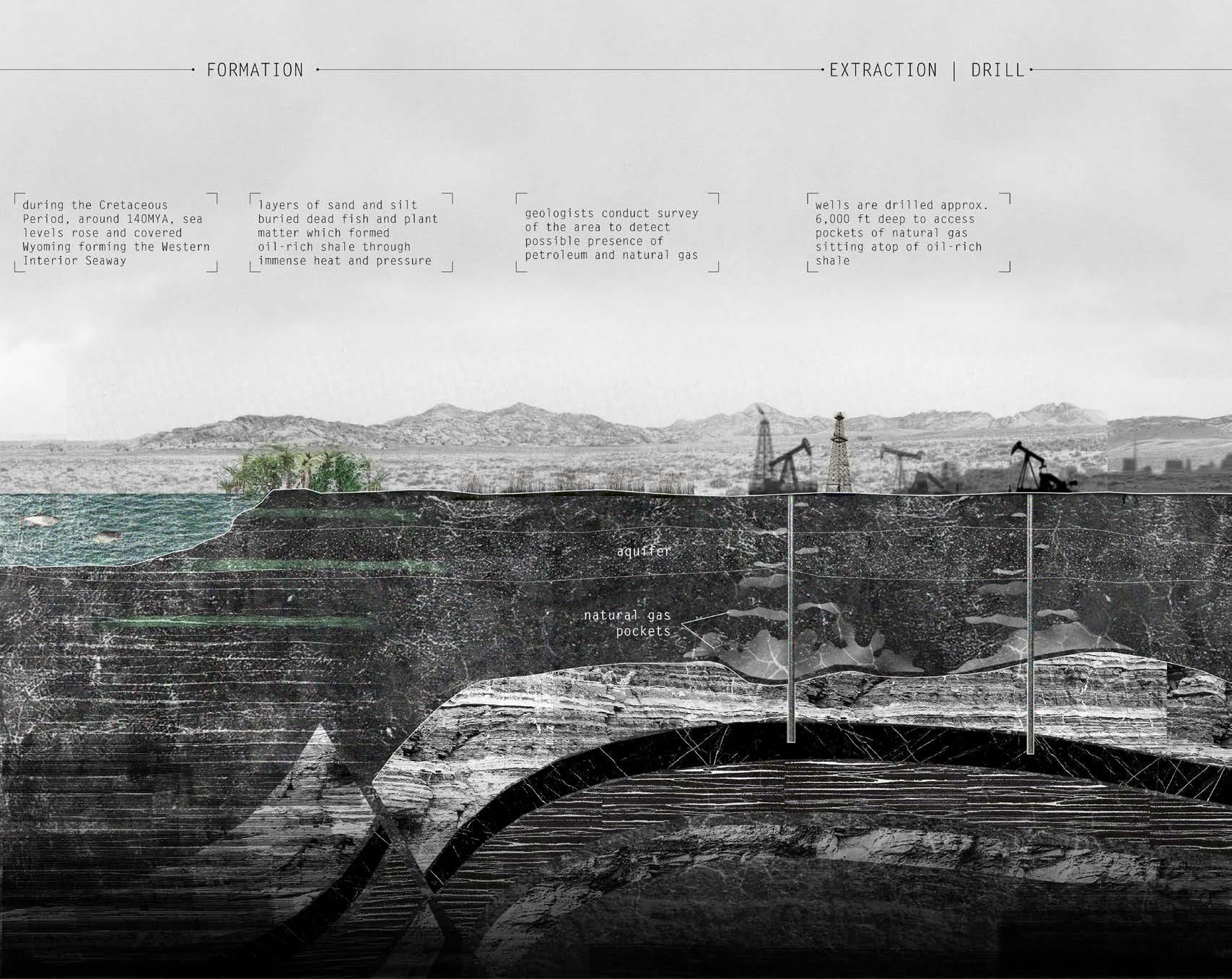

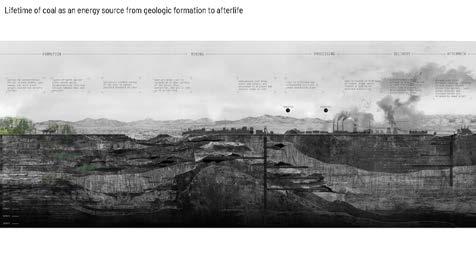

Coal in Wyoming was formed about 350 million years ago when vast swampy forests covered the territory. Over time, immense heat and pressure caused buried plant matter to metamorphosize into coal. In the early to mid-1800s, geologic surveyors discovered coal in the Rock Springs Uplift region of Wyoming. Currently, after being mined, coal is transported via train to a power processing plant. Coal is burned at high heat to create steam, which rotates a turbine to generate electricity.

23 III Energy Source Analyses

LIFETIME OF COAL FROM FORMATION TO EXTRACTION AND ENERGY PRODUCTION

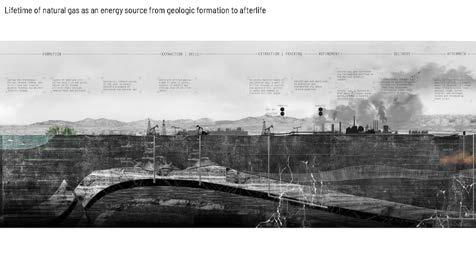

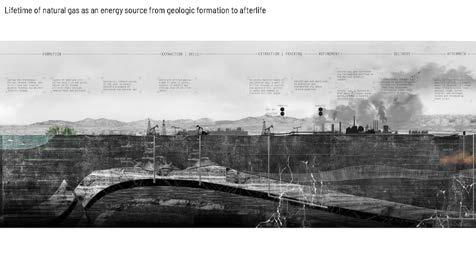

24 Geologic information from: (Hallman 2010)

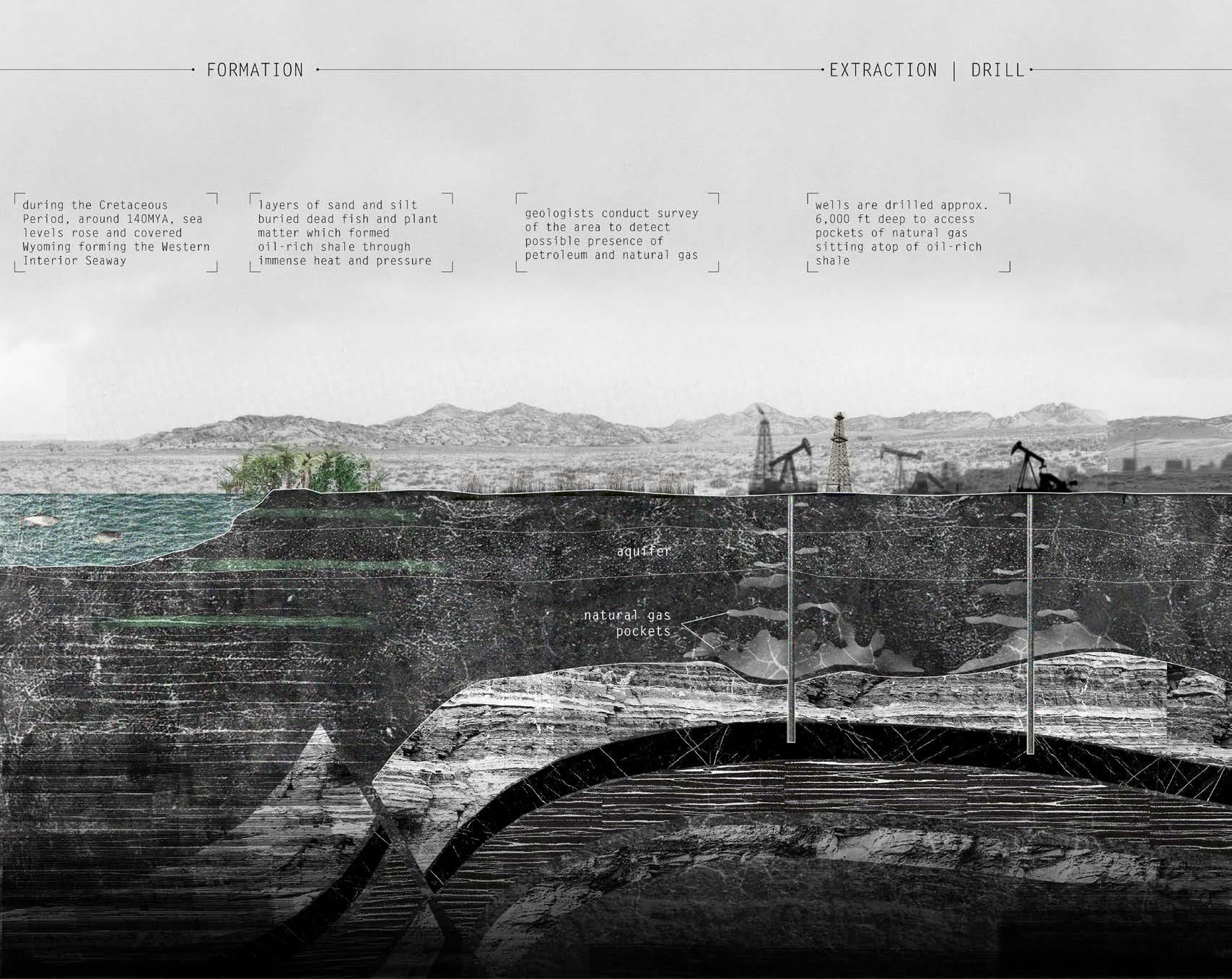

LIFETIME OF OIL AND NATURAL GAS FROM FORMATION TO EXTRACTION AND ENERGY PRODUCTION

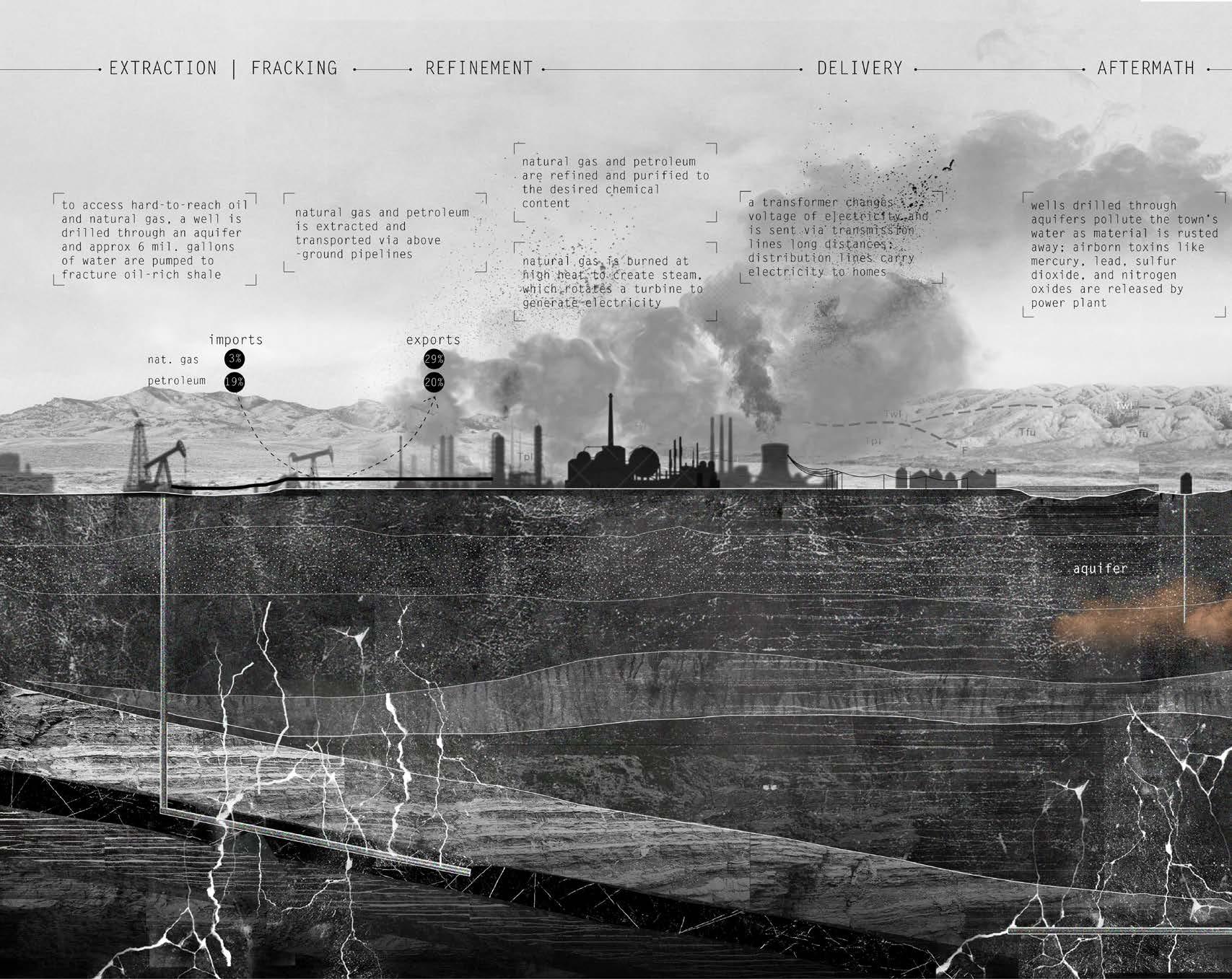

Oil and natural gas in Wyoming was formed about 140 million years ago when sea levels rose, covering Wyoming and forming the Western Interior Seaway. Silt and sand buried dead fish and plant matter, and oil-rich shale formed through immense heat and pressure. To extract oil and natural gas in hard-to-reach places, millions of gallons are water are pumped to fracture (i.e. fracking) the shale.

Oil and gas is then transported via pipelines to a processing plant where it is converted into energy after being purified to their desired chemical content.

25 III Energy Source Analyses

26 Nuclear energy information

of Energy 2021)

from: (Department

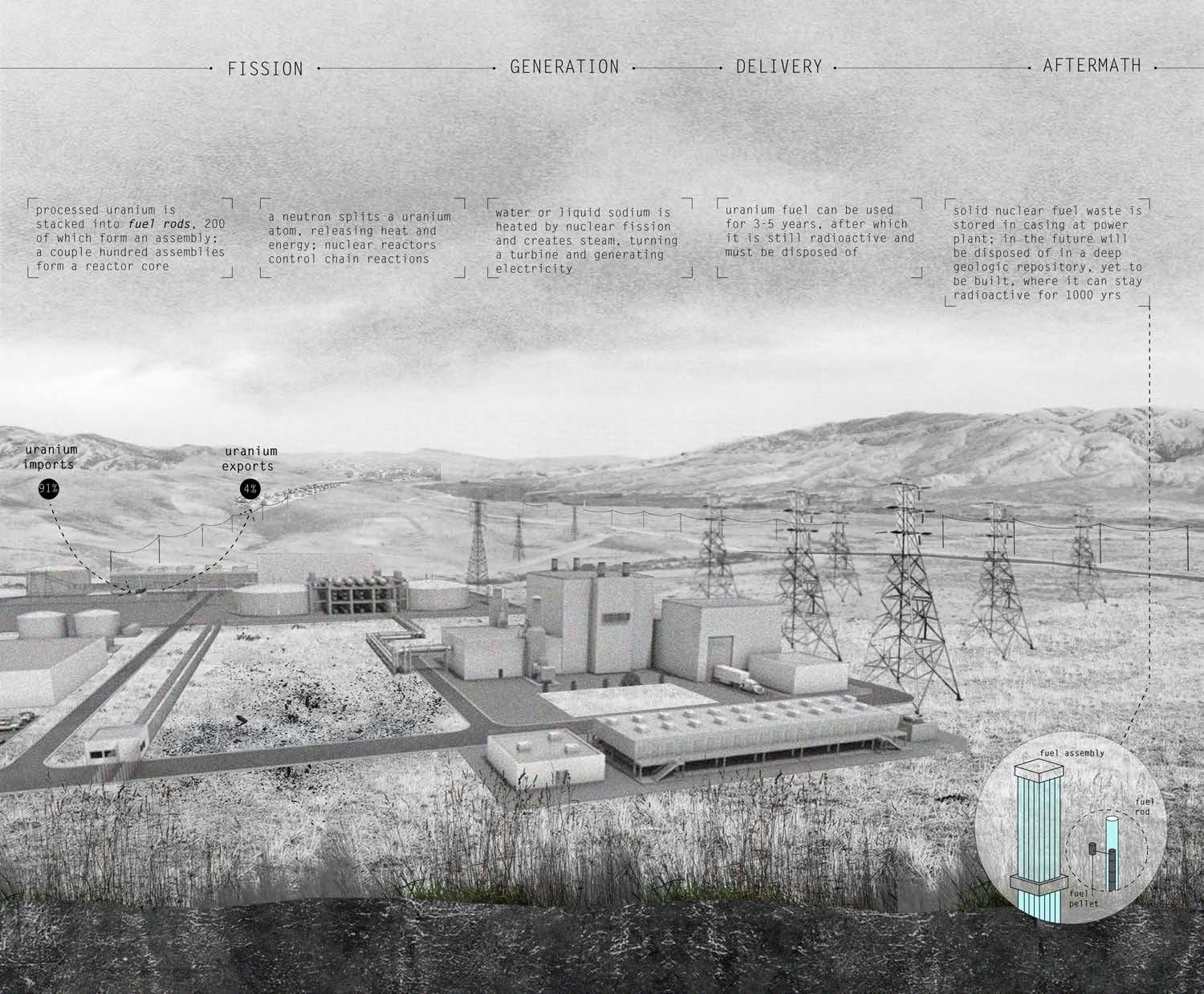

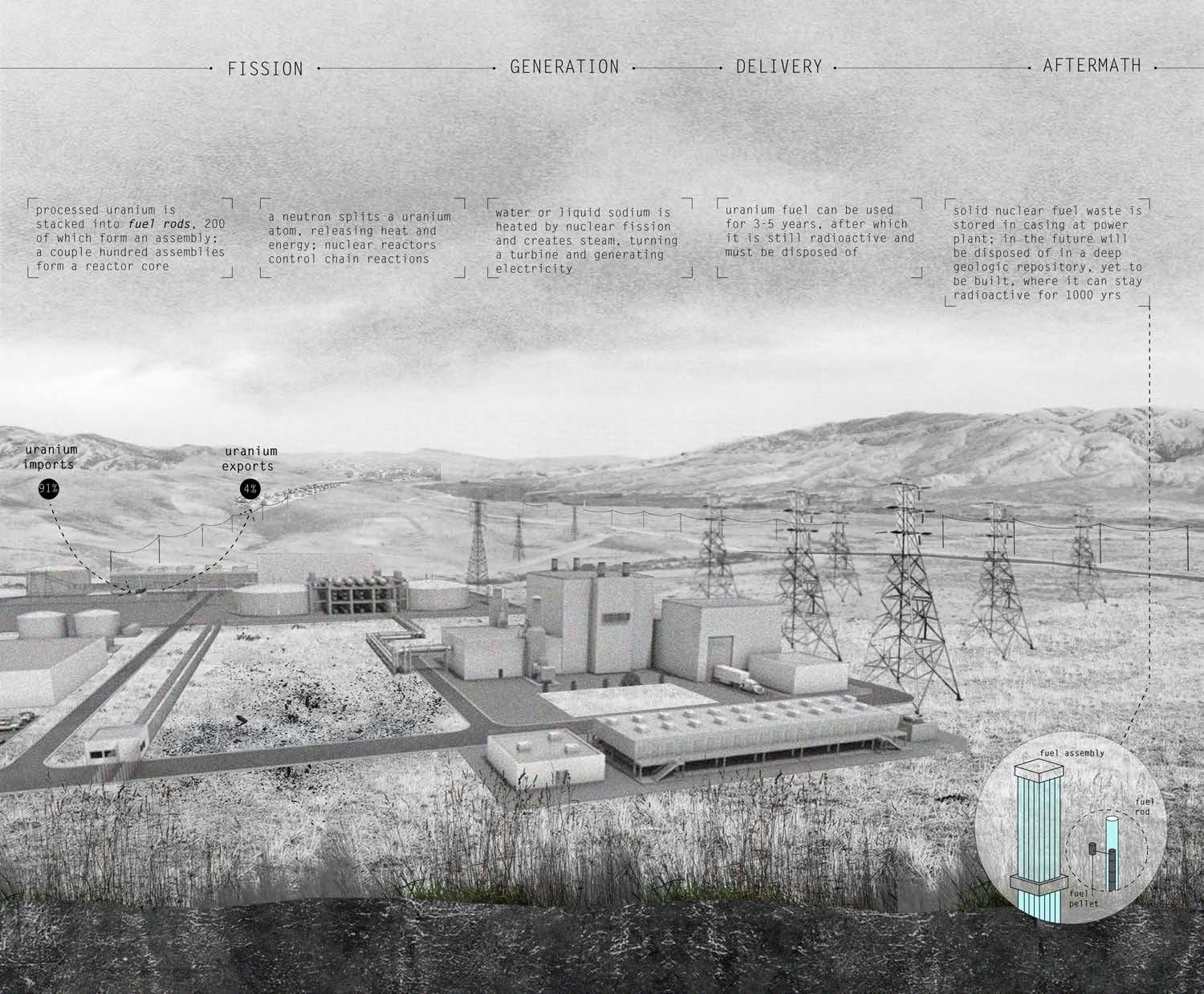

LIFETIME OF NUCLEAR ENERGY FROM RAW MATERIAL TO ENERGY PRODUCTION

The production of nuclear energy relies on the extraction of uranium. A uranium atom is split by a neutron, releasing heat and energy. Water or liquid sodium is heated by nuclear fission and creates steam, which turns a turbine and generates electricity.

Uranium as fuel can be used for 3 to 5 years, after which it is still radioactive and must be disposed of. Solid nuclear fuel waste is stored in a casing at the power plant.

27 III Energy Source Analyses

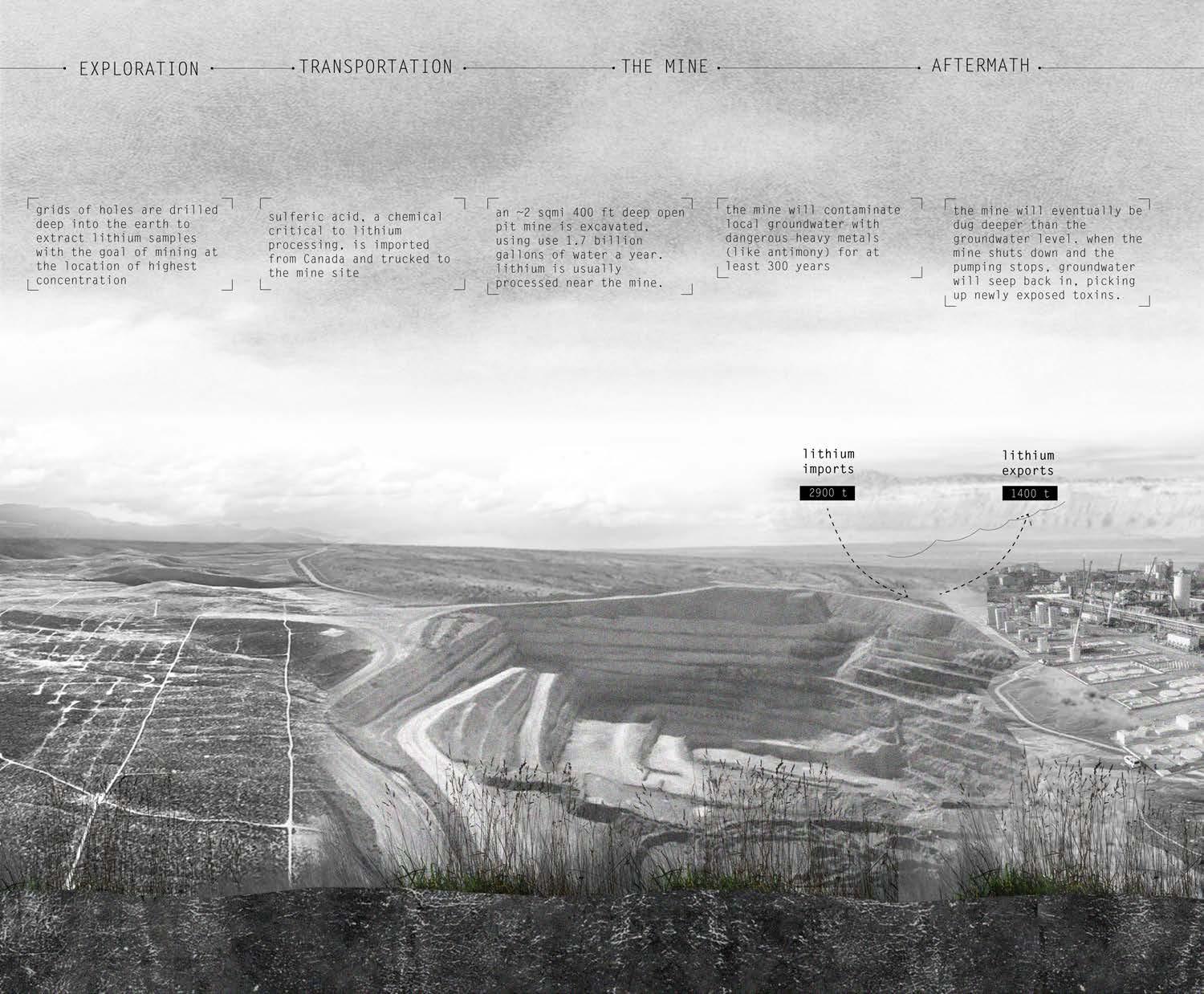

Lithium mining is vital to electrification. Renewable resources require lithium for the production of batteries, which reveals a dark present day reality of new environmental exploitation.

28 IV

AN ELECTRIFIED LANDSCAPE

The Rise of Lithium Extraction

Today, many environmentalists, politicians, and architects have the goal of switching to total electrification and renewable energy as a mode of decarbonization. With General Motor’s transitioning out of gas and diesel by 2035, the Biden administration’s infrastructure bill providing $7.5 billion to build charging infrastructure, and, closer to home, TCAT’s addition of 7 electric busses to their fleet, America begins its transition to an electrified landscape.

Wyoming is now slowing its reliance on nonrenewable energy and is beginning its transition to renewables. The state provides energy for the whole of America’s Pacific Northwest, so as more liberal-leaning states urge renewable-derived energy, Wyoming is building wind turbine fields to keep up with demand. This promises another social, environmental, and cultural upheaval as people look for new jobs in the renewables sector as coal and gas powered power plants in the region begin to close.

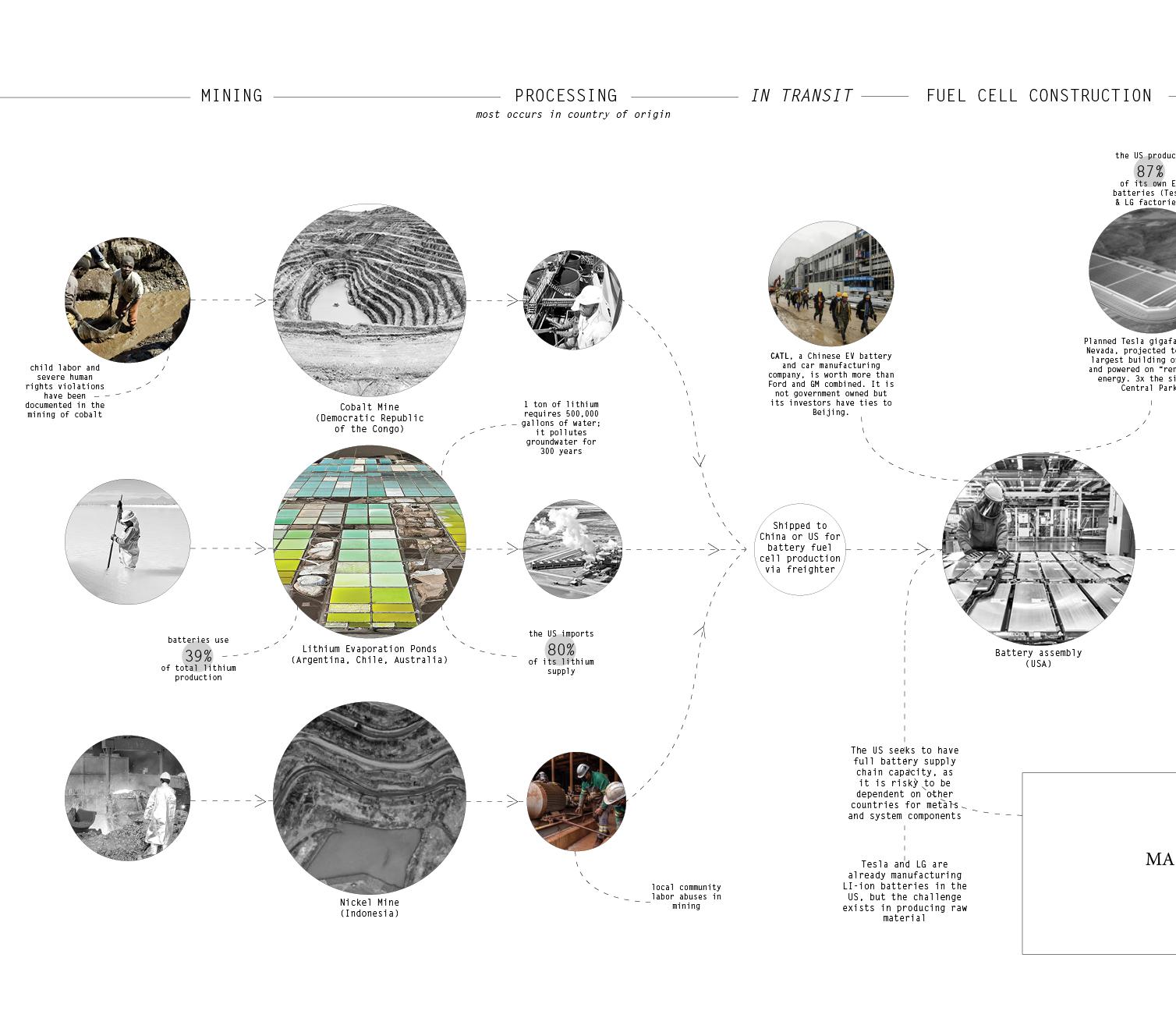

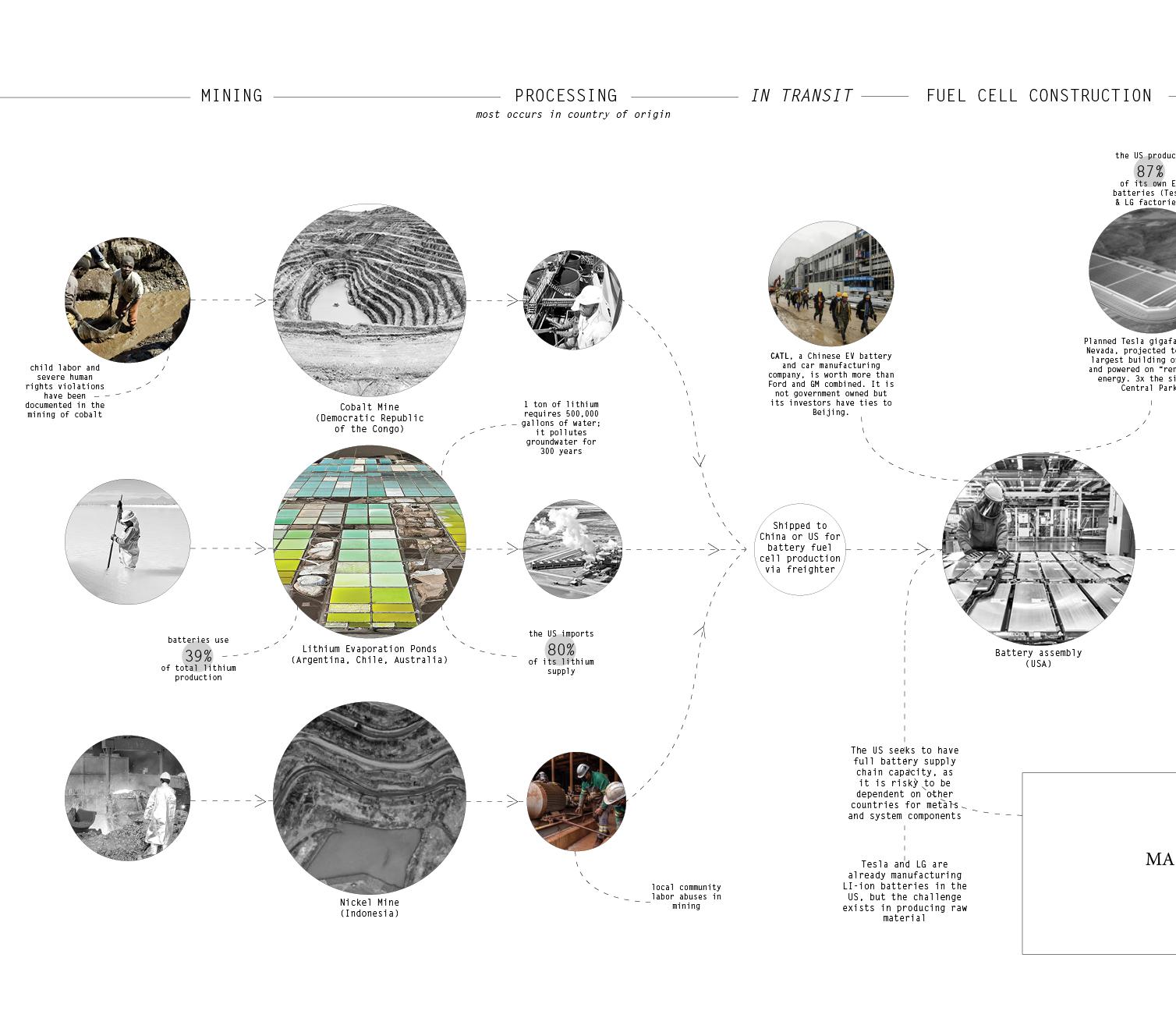

While this transition to “green” energy is usually viewed optimistically, it requires the extraction of lithium to produce batteries. Wind turbines, solar fields, and electric vehicles all rely on lithium-ion batteries for energy storage. These batteries require imported minerals from all over the globe for production. Lithium mining, namely, reveals a dark present-day situation of environmental exploitation.

29

IV An Electrified Landscape

30 Photos from: (NowThis News 2021)

RISE OF RENEWABLE ENERGY DEMAND IN WYOMING

To keep up with demand from states requesting renewable-derived energy, Wyoming has built, and is currently building, fields of wind turbines on open range cattle land.

31

IV An Electrified Landscape

32 Information on

EV batteries and labor from: (GreenCarReports 2022) and (Granholm 2021)

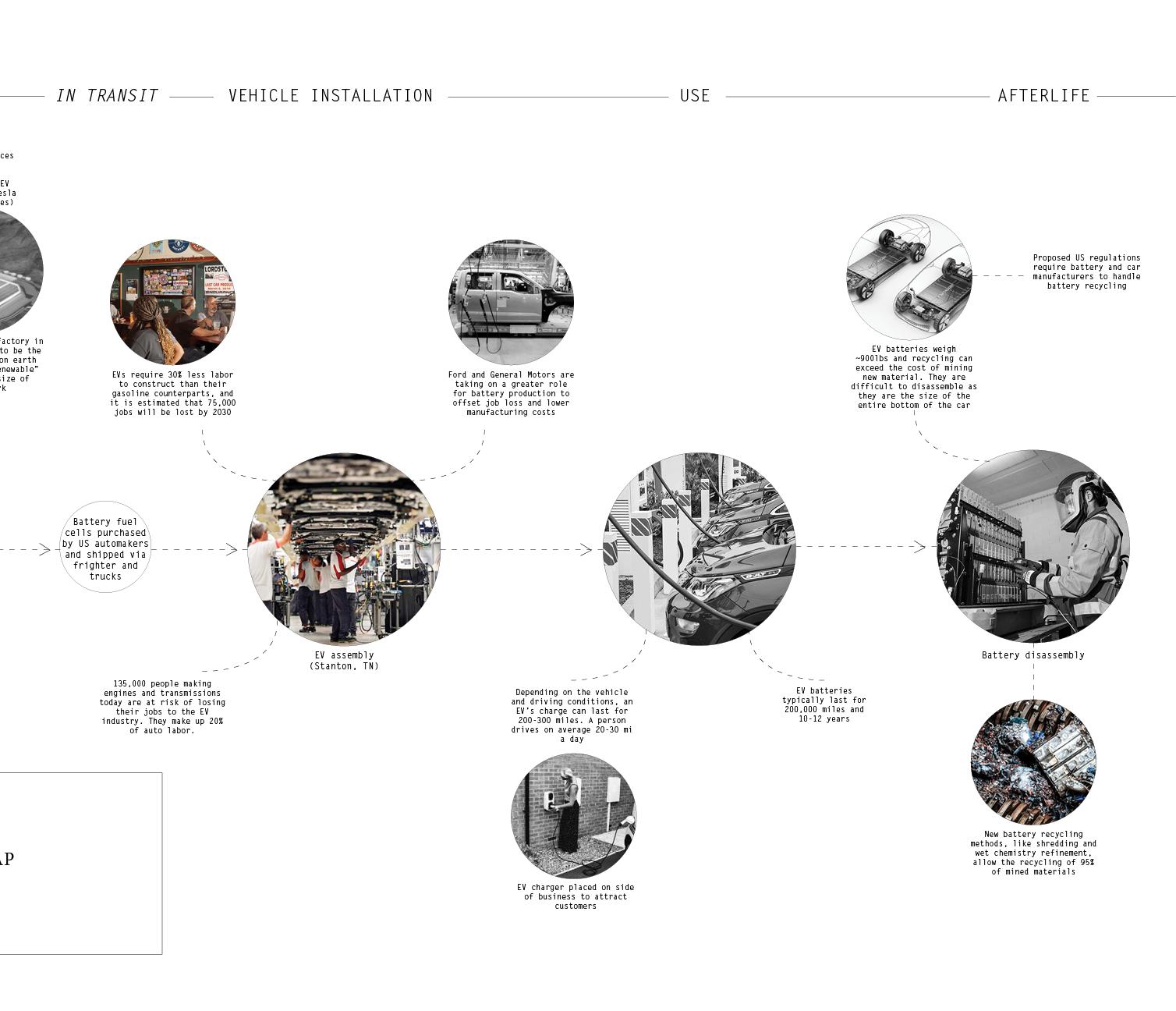

PROCESSES AND ACTORS INVOLVED IN LITHIUM-ION BATTERY PRODUCTION

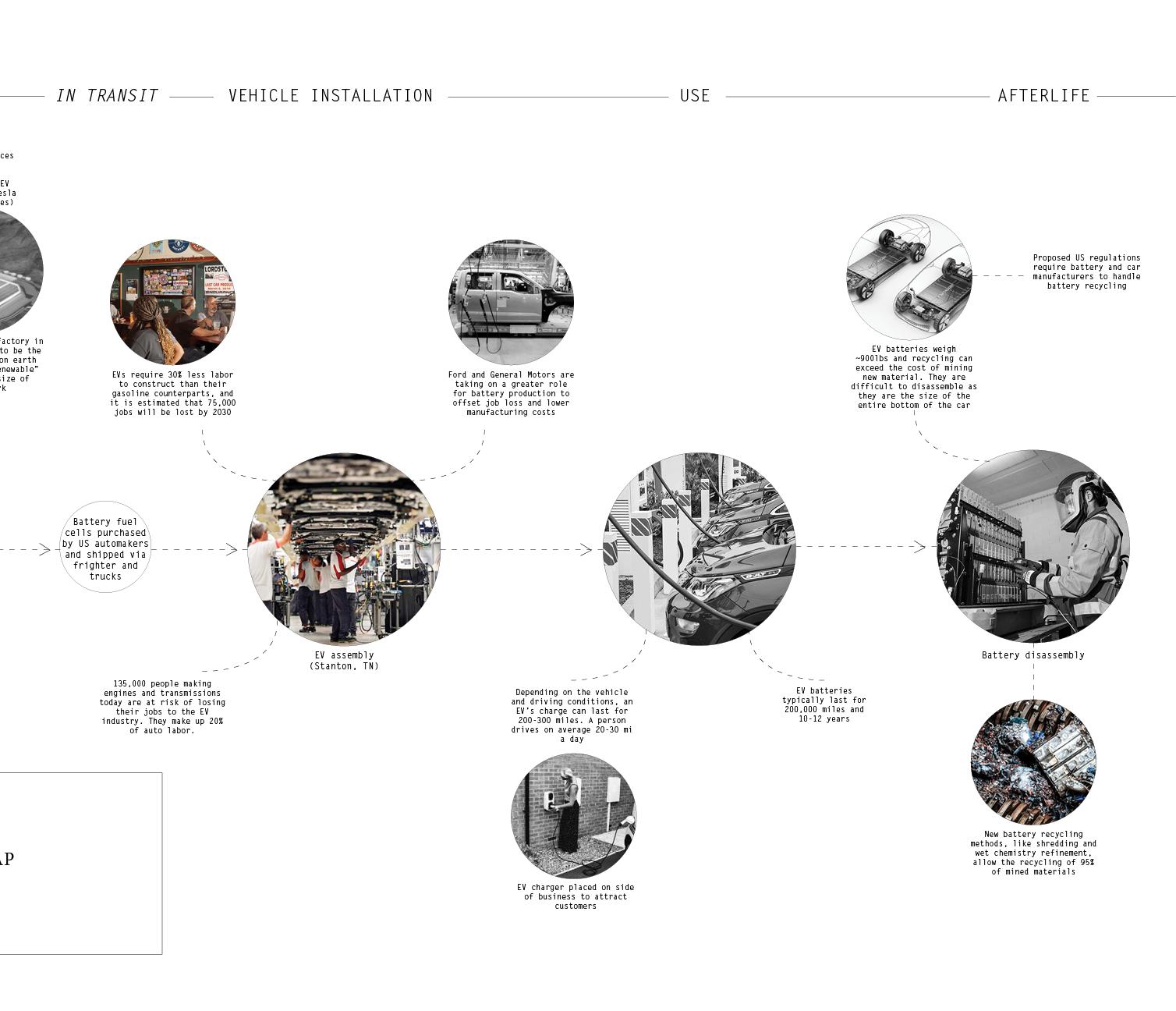

Minerals in addition to lithium, like nickel and cobalt, are also required for the production of a lithium-ion battery. Child labor and severe human rights violations have been discovered in mines that produce batteries for electric vehicle companies, such as Tesla.

About 20% of the auto labor market is composed of people who make engines and transmissions. They are at risk of losing their jobs to the EV industry.

33

IV An Electrified Landscape

34

Lithium extraction information from: (Penn, Lipton, and Angotti-Jones 2021) Photos by: (The Guardian 2021)

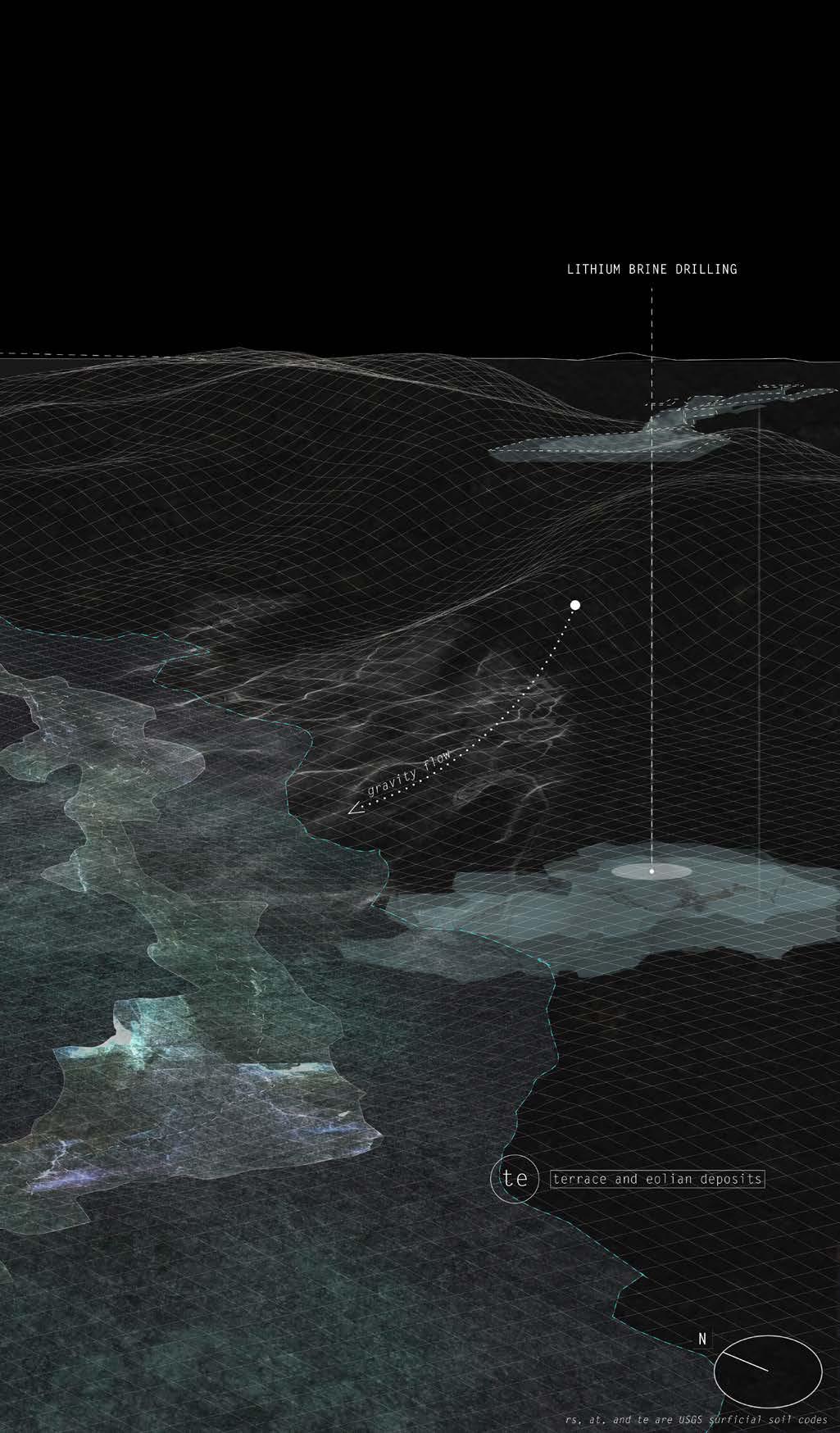

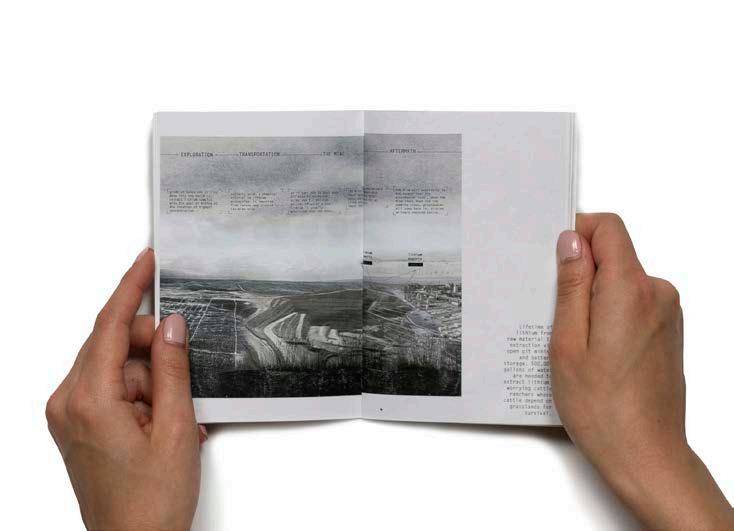

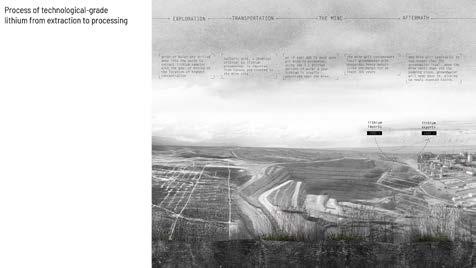

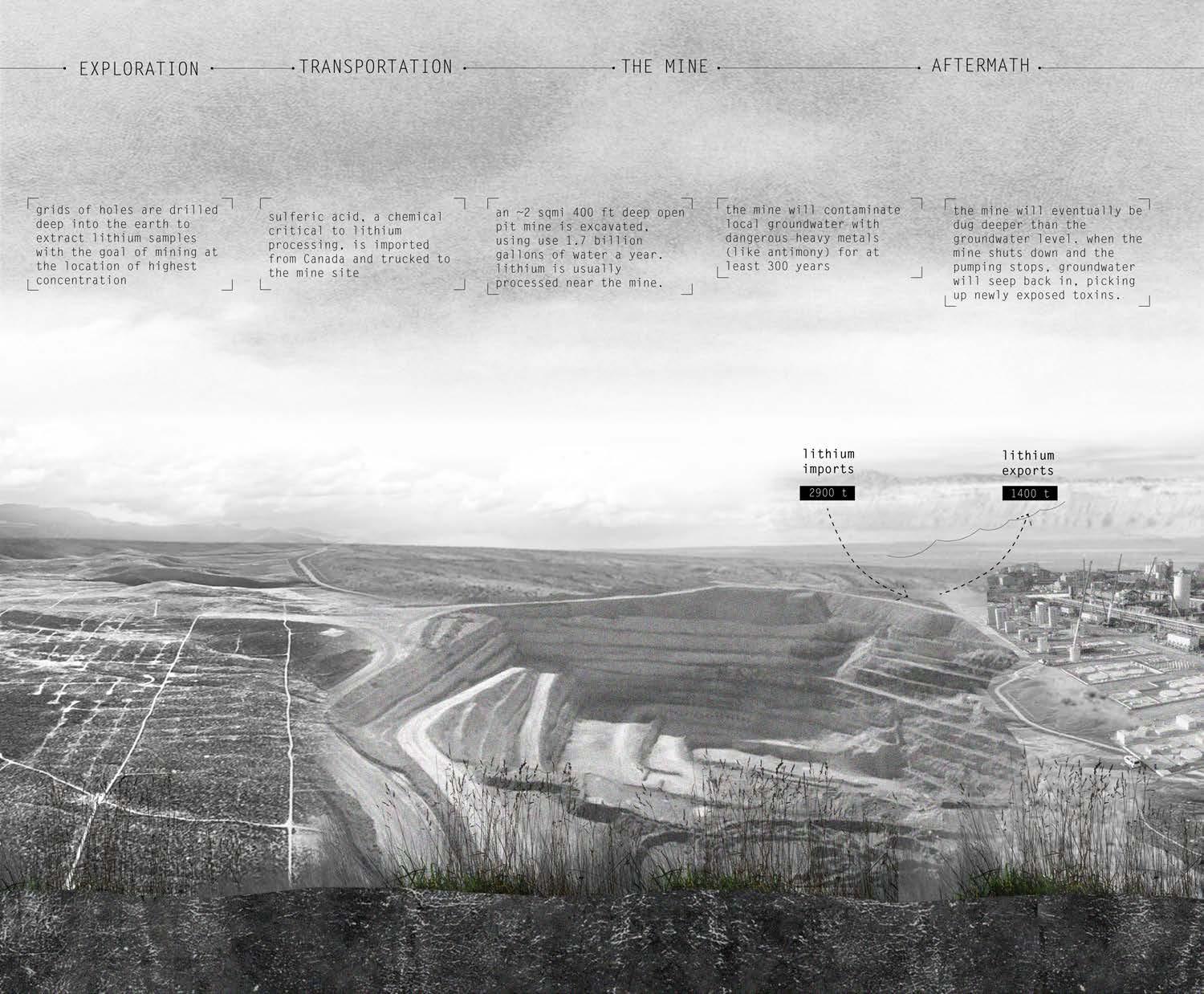

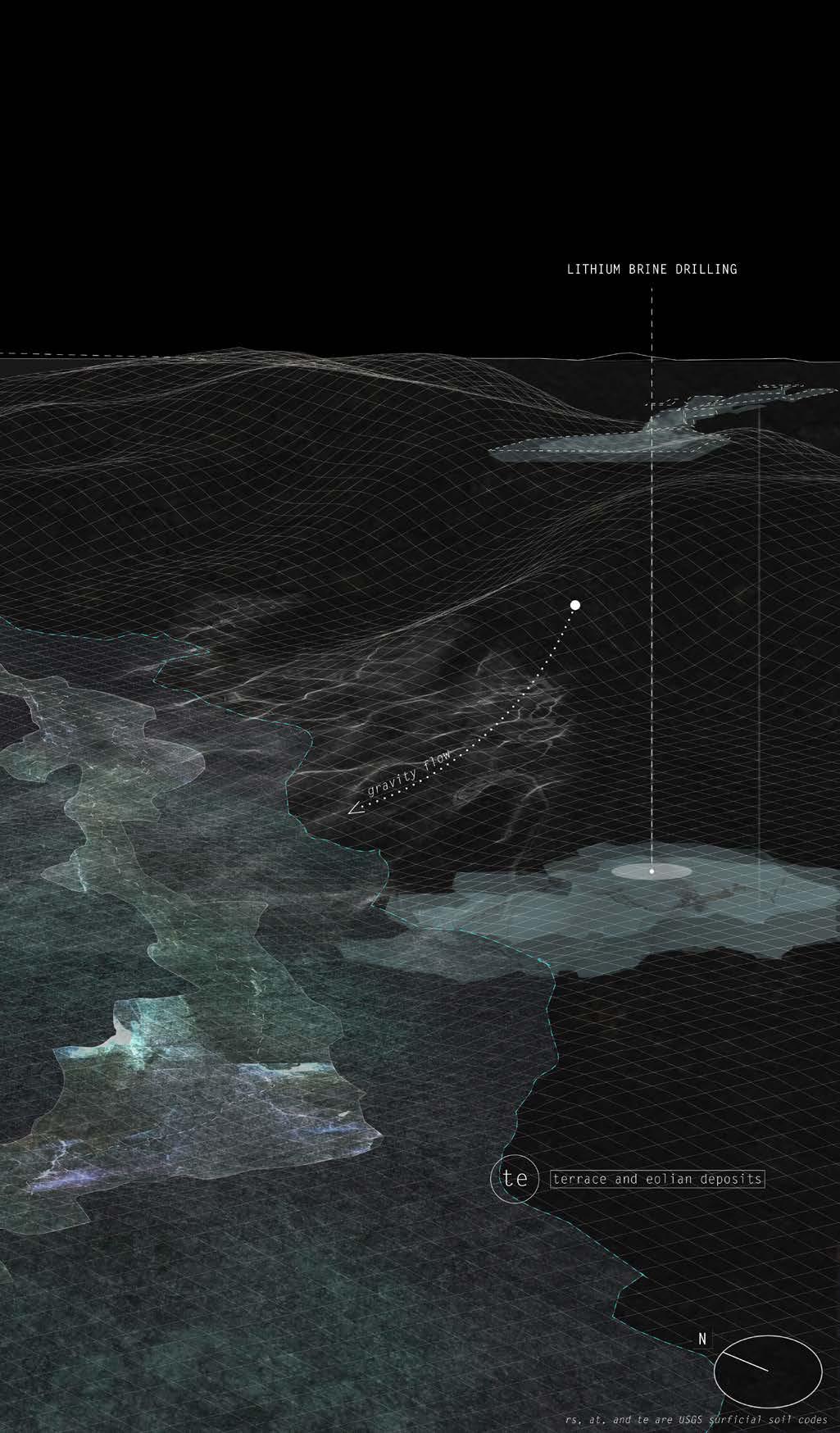

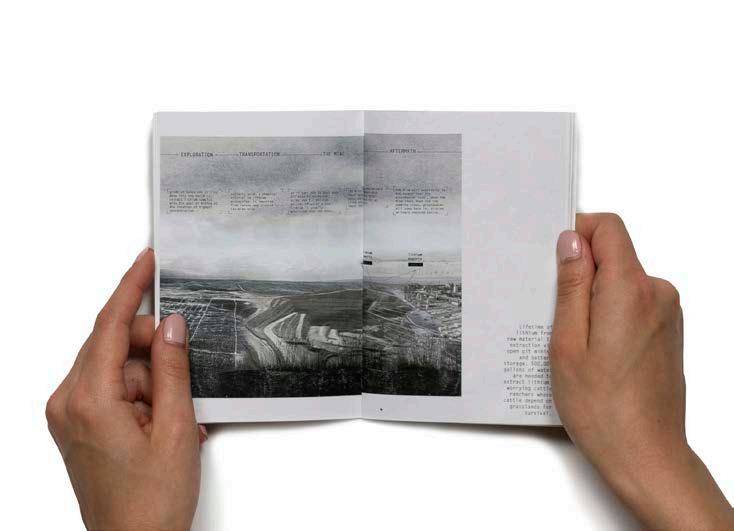

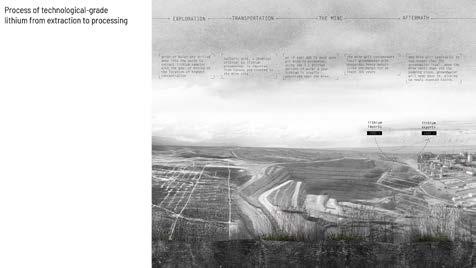

LIFETIME OF LITHIUM FROM RAW MATERIAL TO EXTRACTION AND BATTERY STORAGE

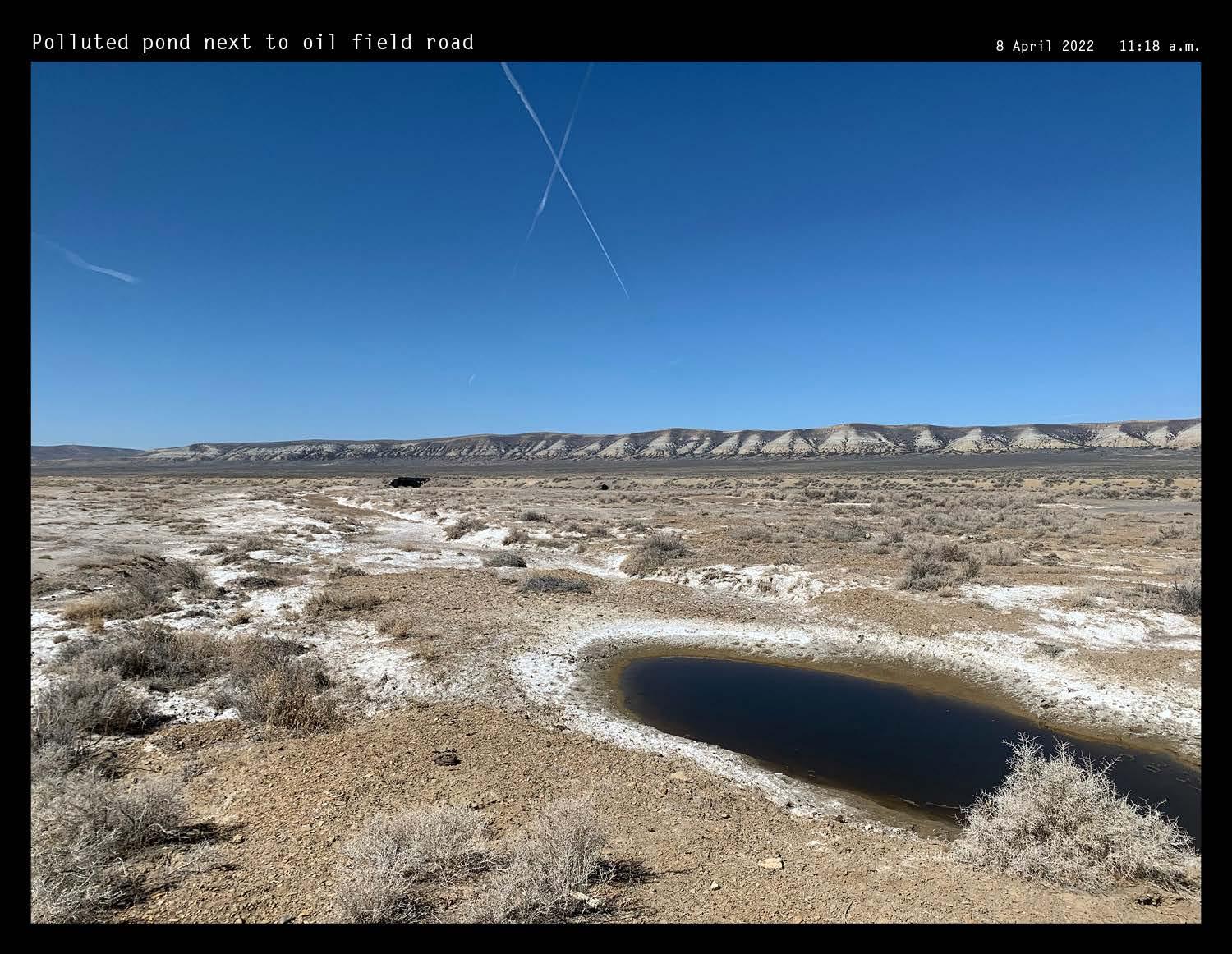

Lithium can be extracted either through open pit mining or by evaporation from brine found underground. Brine-derived lithium is usually located in parallel with oil and gas drilling, where excess water is tested for possible lithium concentration. This salty water is then pumped to the surface, through channels, and into large shallow pools. Ideally in hot and dry climates, water is evaporated from the brine with lithium leftover. Salt is a major byproduct of evaporation, as well as traces of magnesium. 500,000 gallons of water are needed to extract one ton of lithium, worrying cattle ranchers whose cattle depend on grasslands for survival.

35

IV An Electrified Landscape

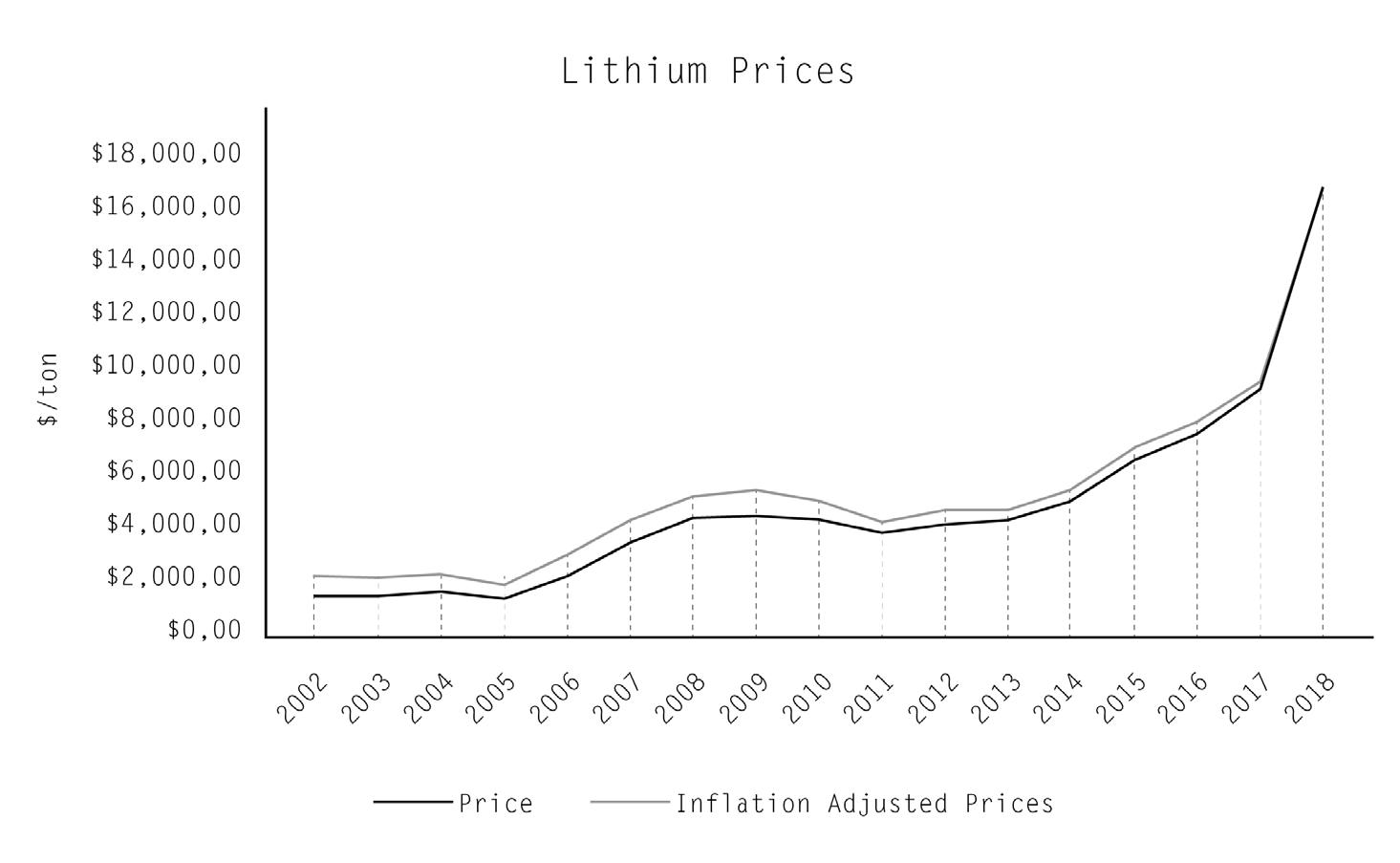

36 Lithium

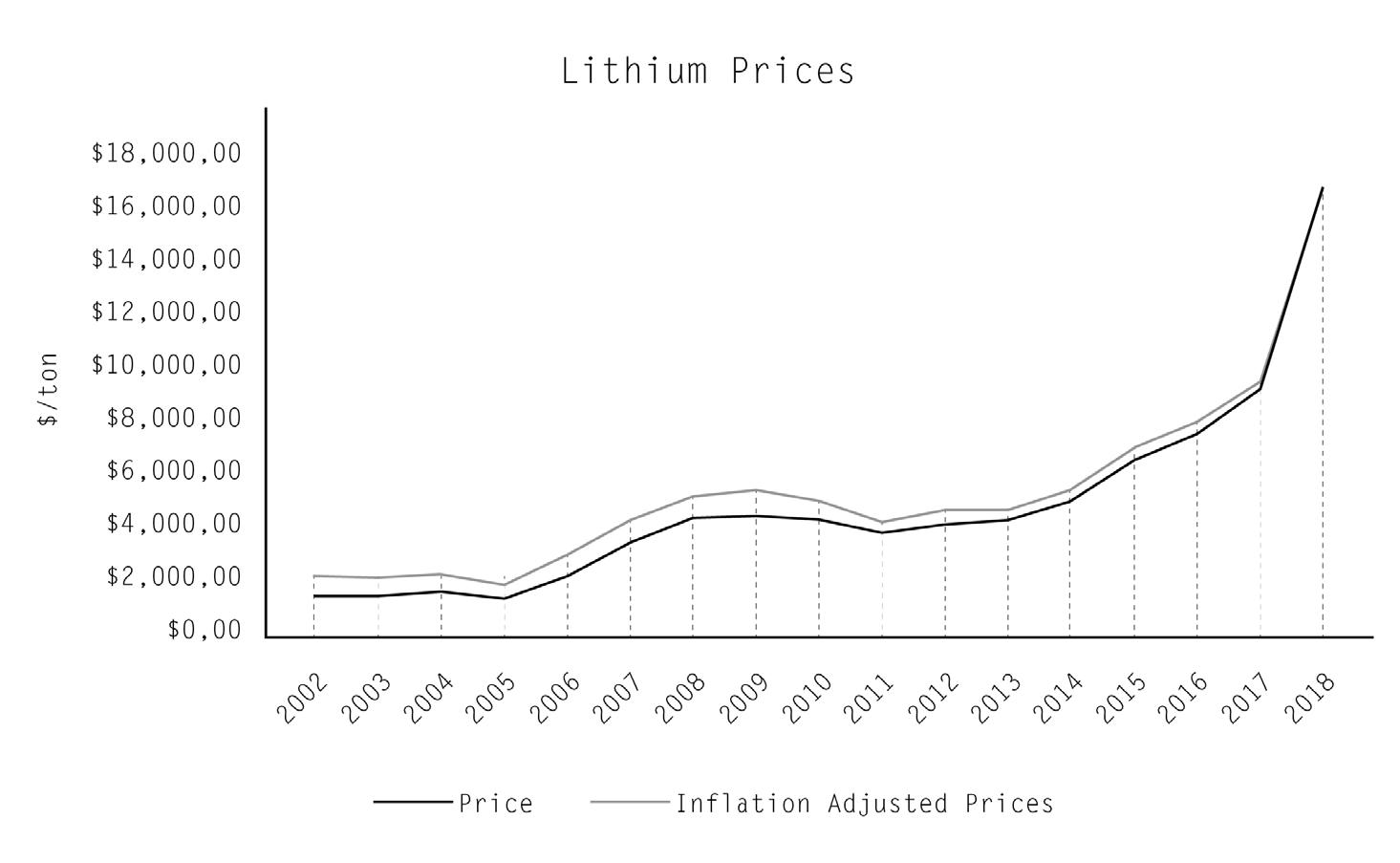

price data from: (Ewing and Boudette 2022)

MOTORS IS ON ITS WAY TO AN ALL-ELECTRIC FUTURE.”

-Mary

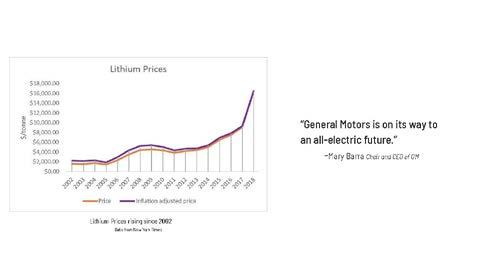

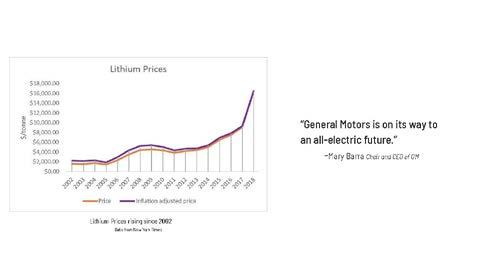

LITHIUM PRICES RISING EXPONENTIALLY SINCE RISE IN EV POPULARITY

Lithium prices are rising in conjunction with the growing renewable energy industry and electric vehicle industry. The US currently imports more than 80% of its lithium supply from Argentina, Bolivia, and Australia.

37

IV An Electrified Landscape

“GENERAL

Barra Chair and CEO of GM

treehugger.com

gillettenewsrecord.com

38

mining.com

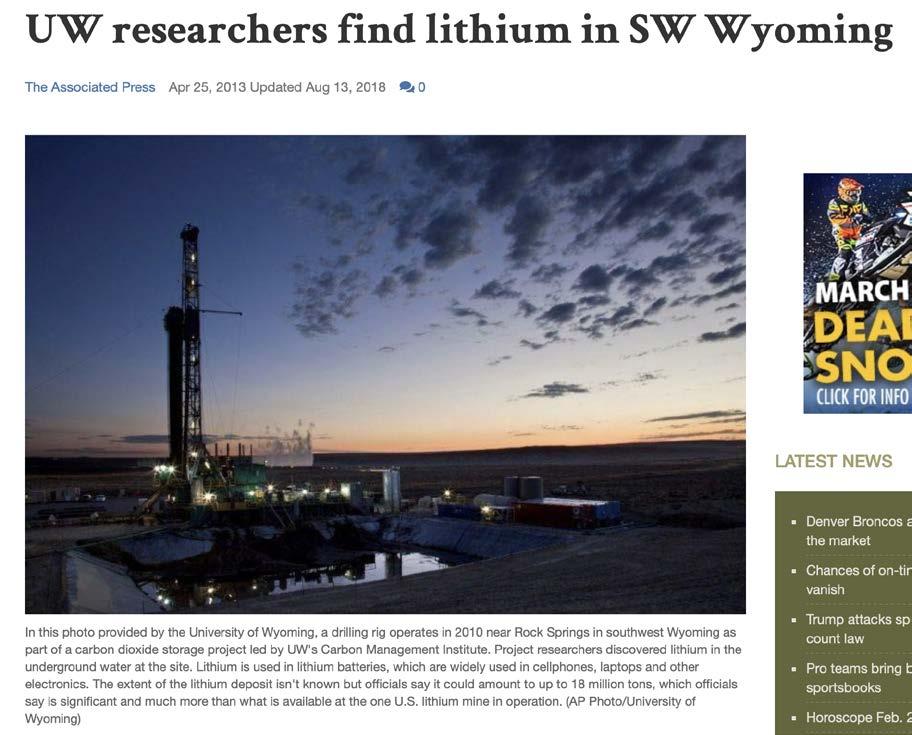

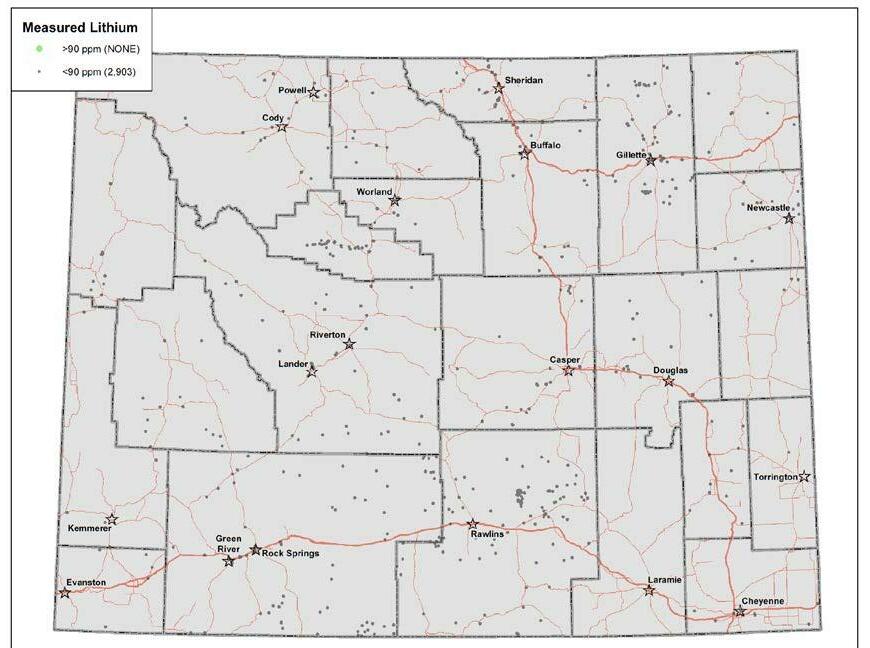

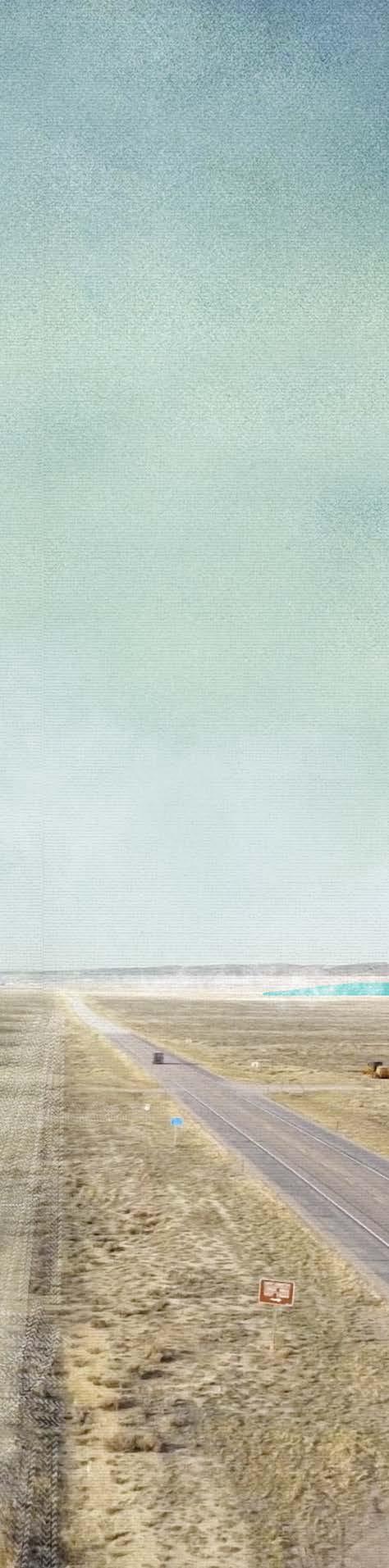

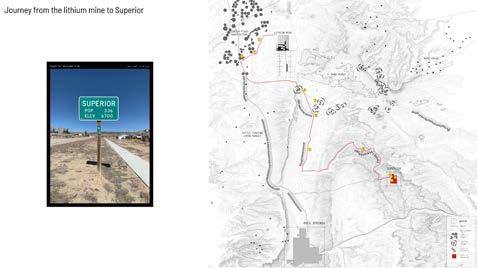

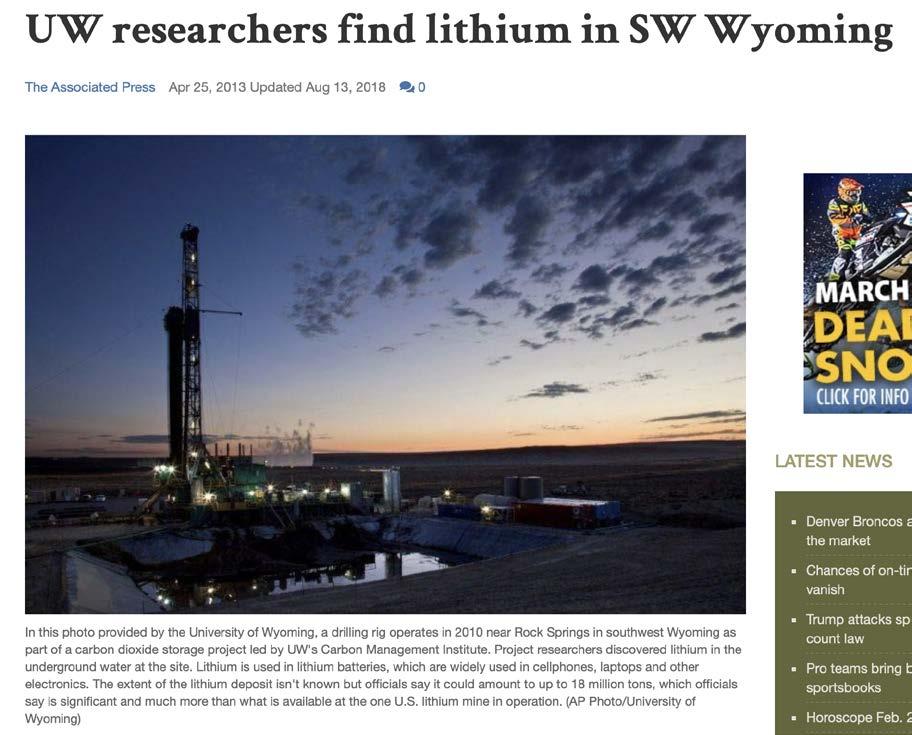

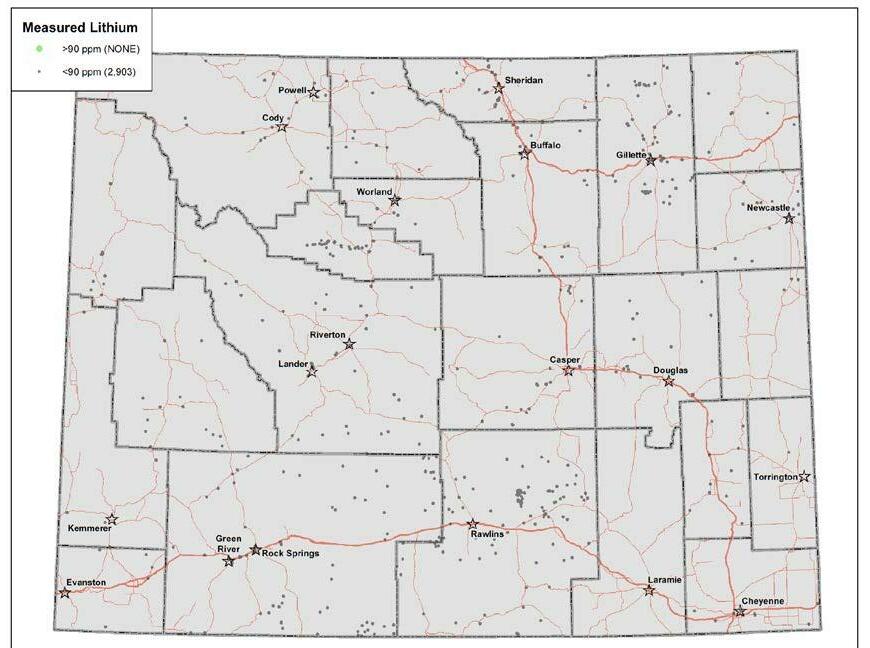

LITHIUM DEPOSITS DISCOVERED IN WYOMING VIA OIL AND GAS WELL WASTEWATER TESTING

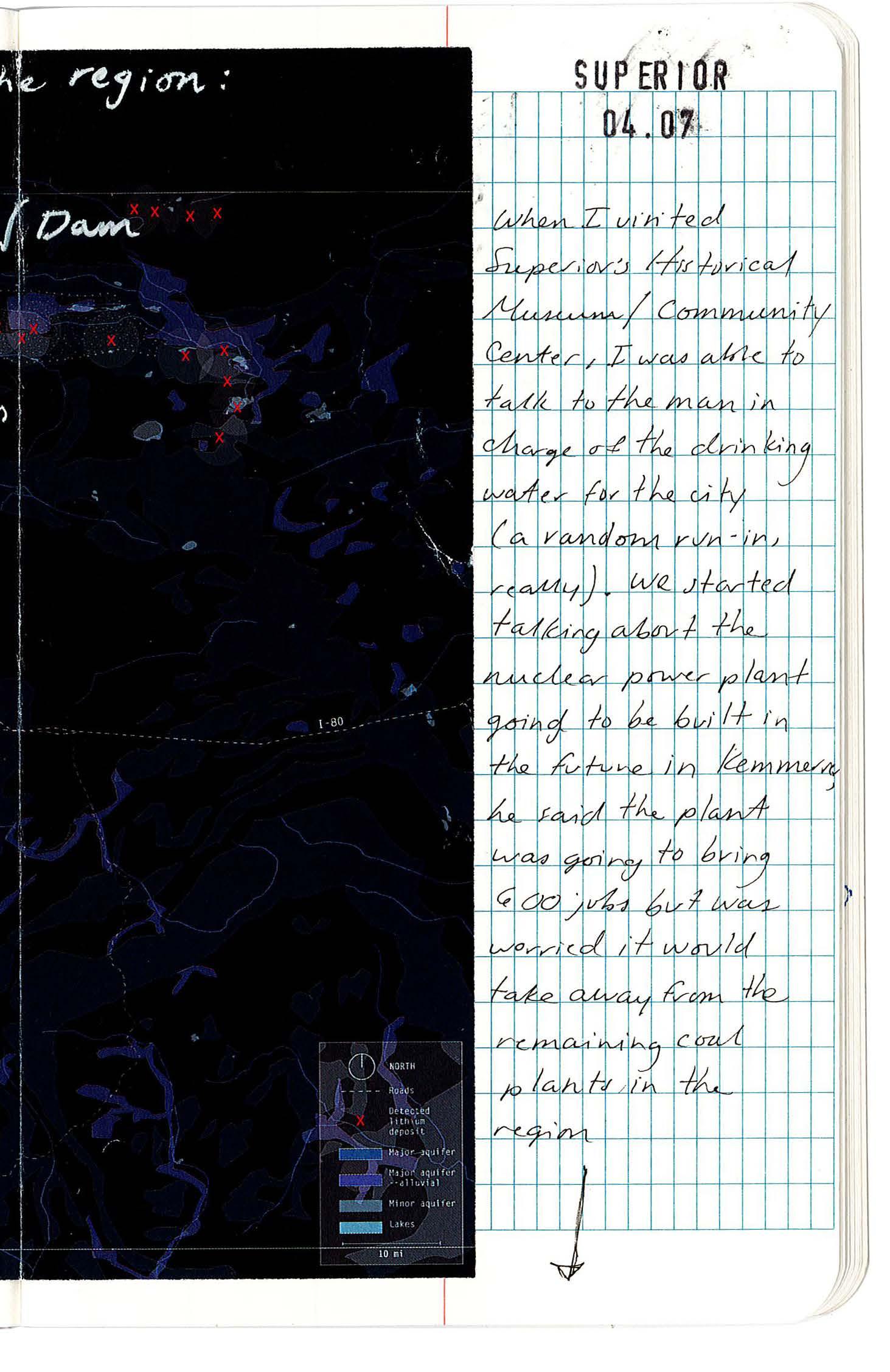

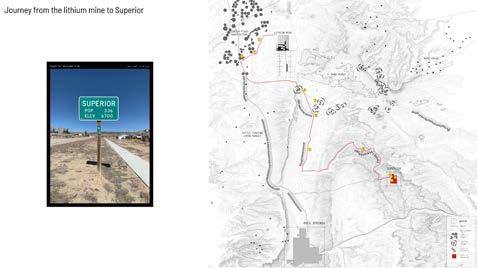

Lithium deposits have been located about 25 miles north of Superior. While not economic now, with the cost of lithium increasing exponentially, construction might ensue within the next 15 years. Superior will see a large influx of migrant workers like it has in the past as a support city for new Rock Springs mine and power plant construction.

National Water Information System (NWIS) water samples with lithium concentration data (NWIS, 2015)

39

IV An Electrified Landscape

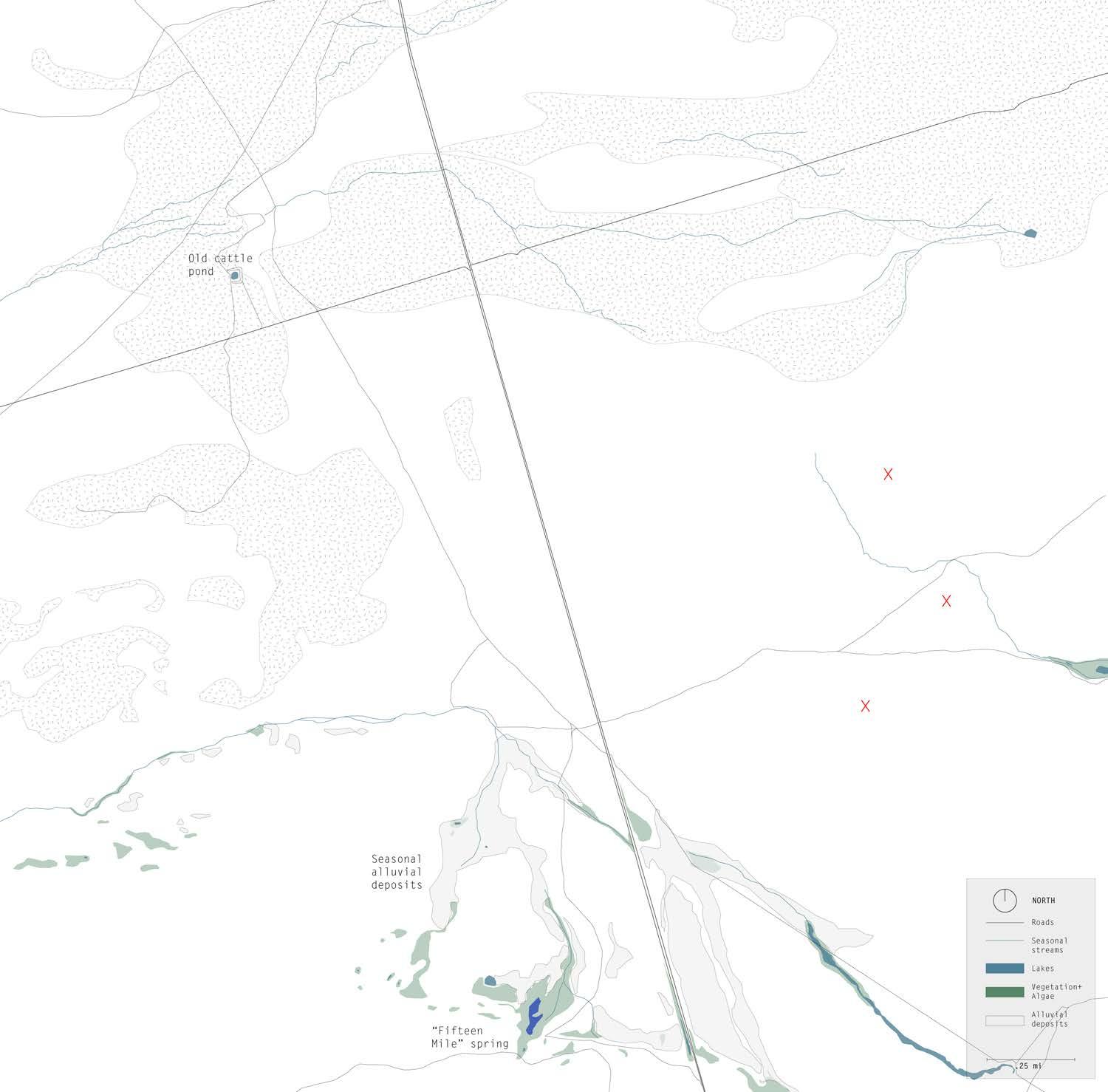

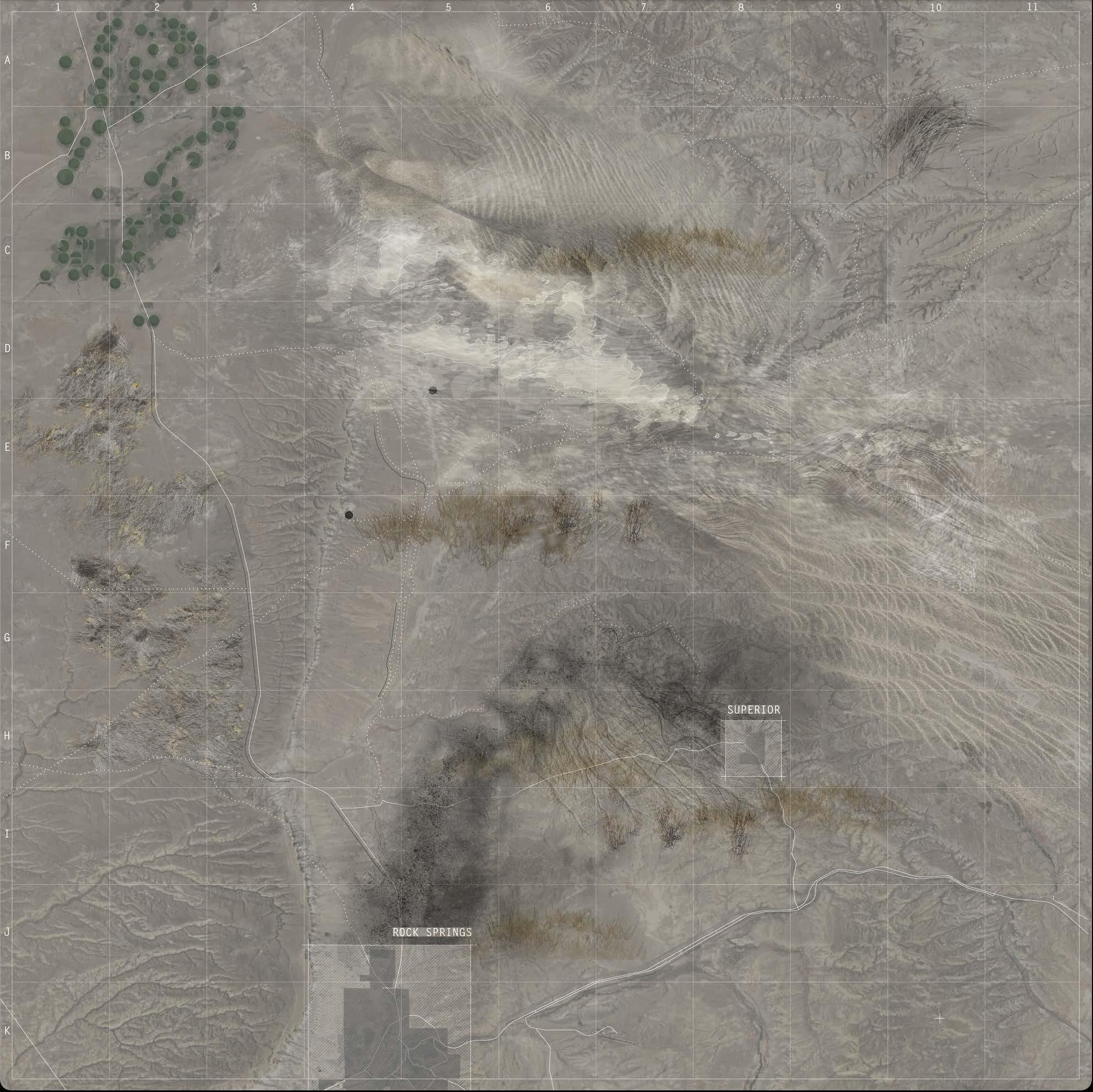

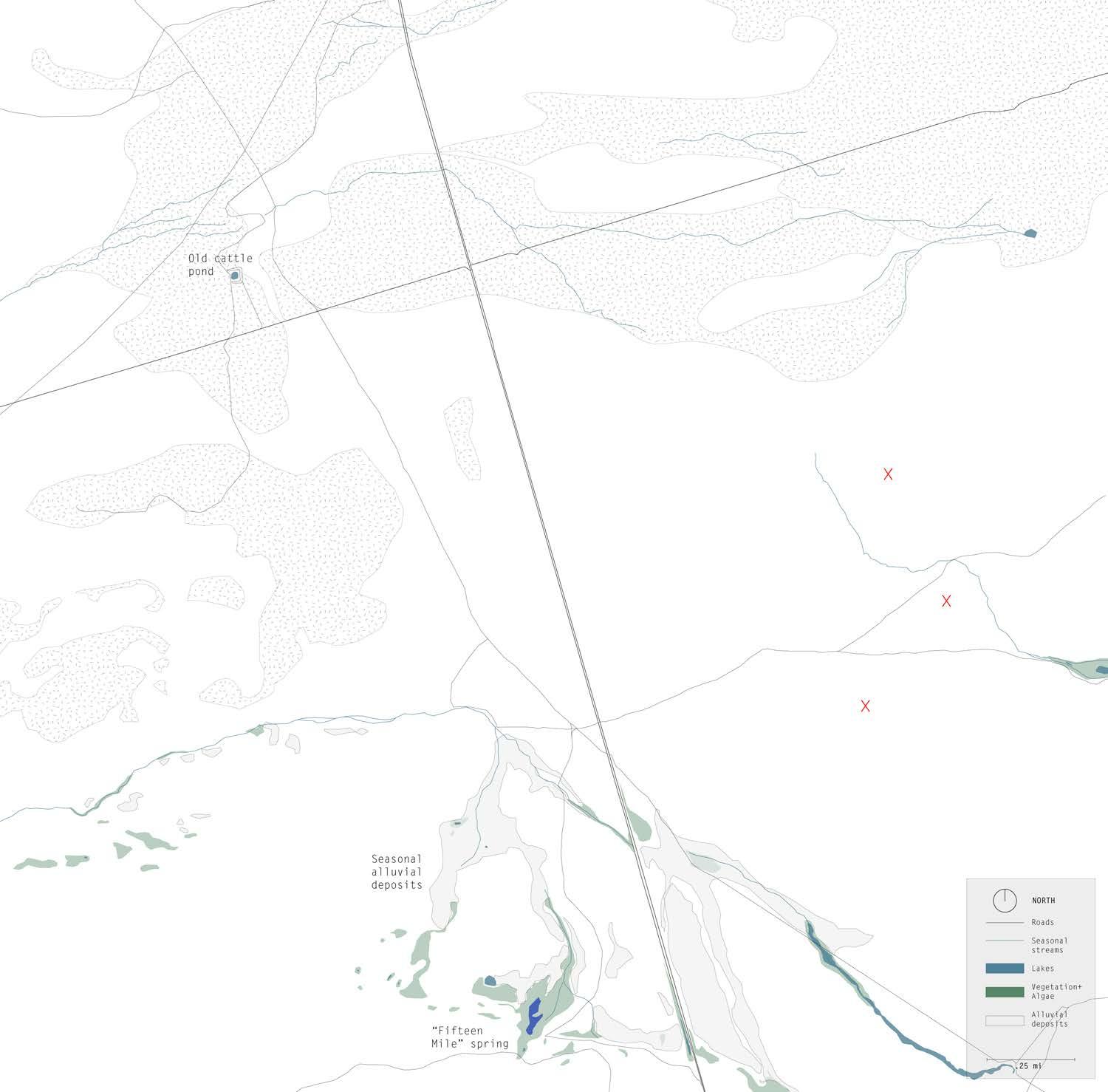

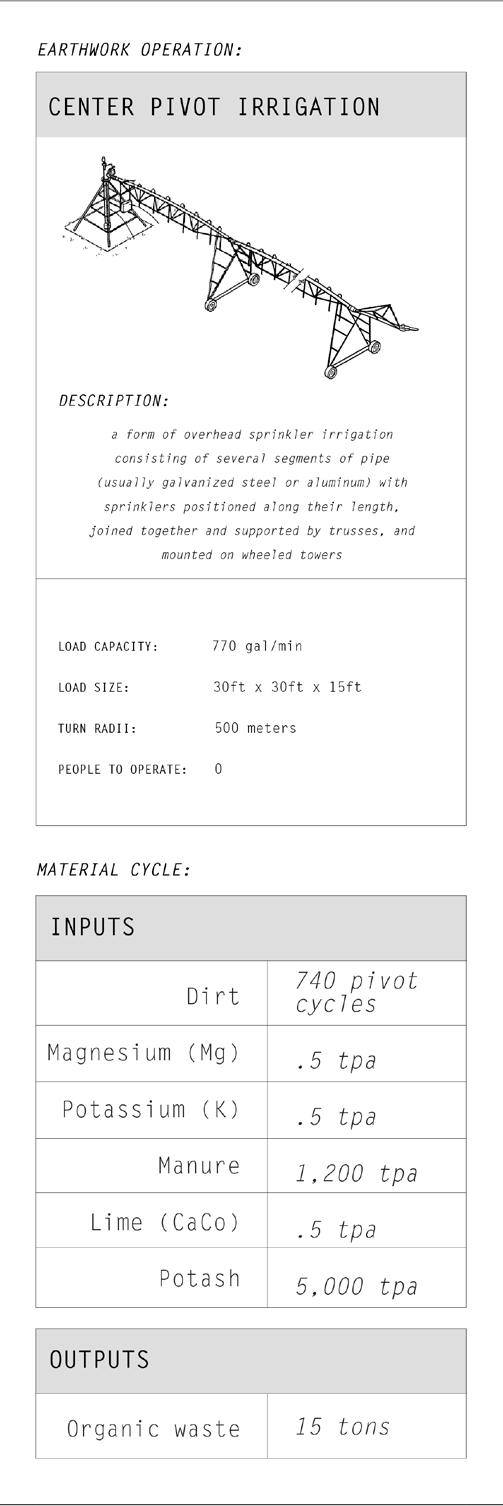

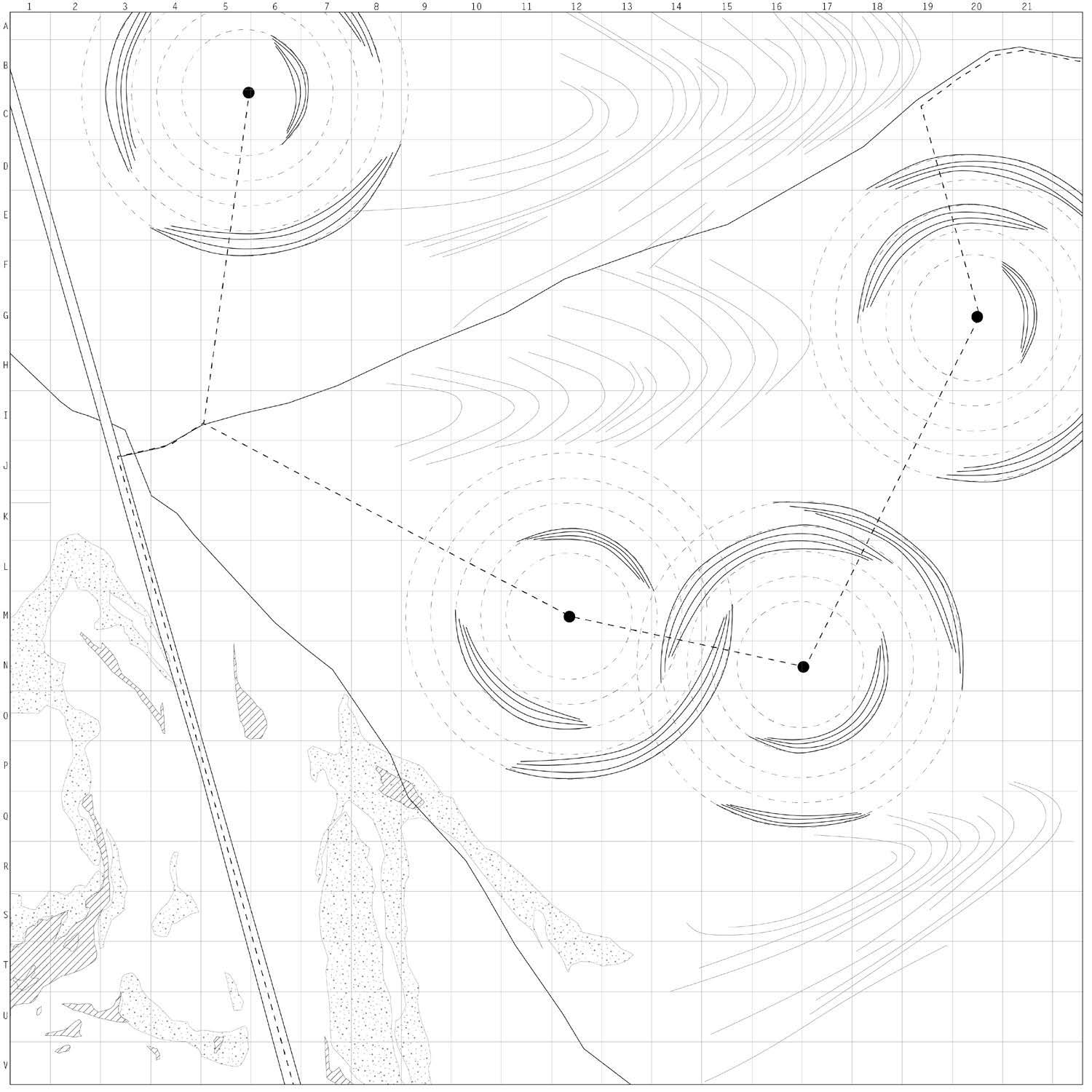

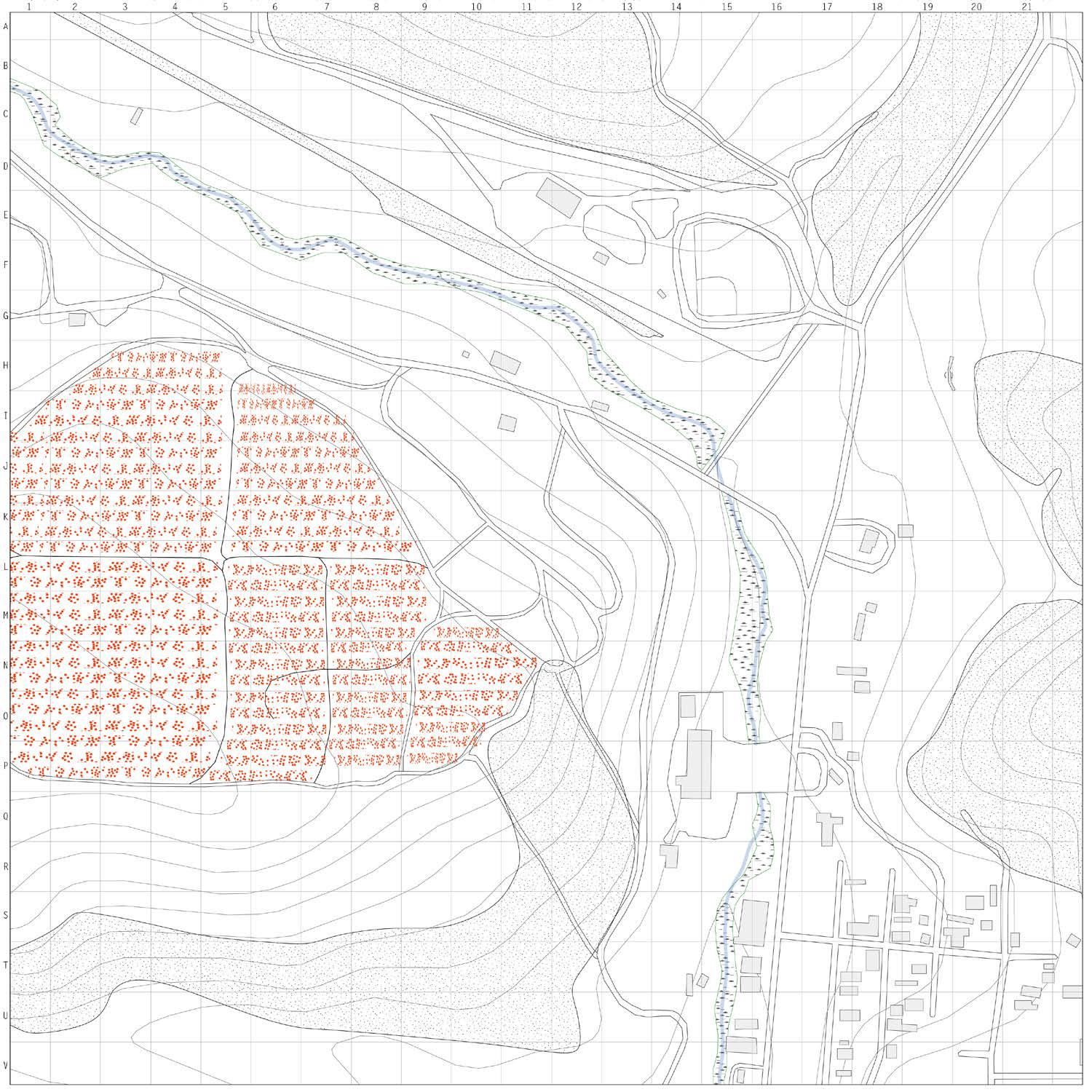

40 +0 ft .25 mi

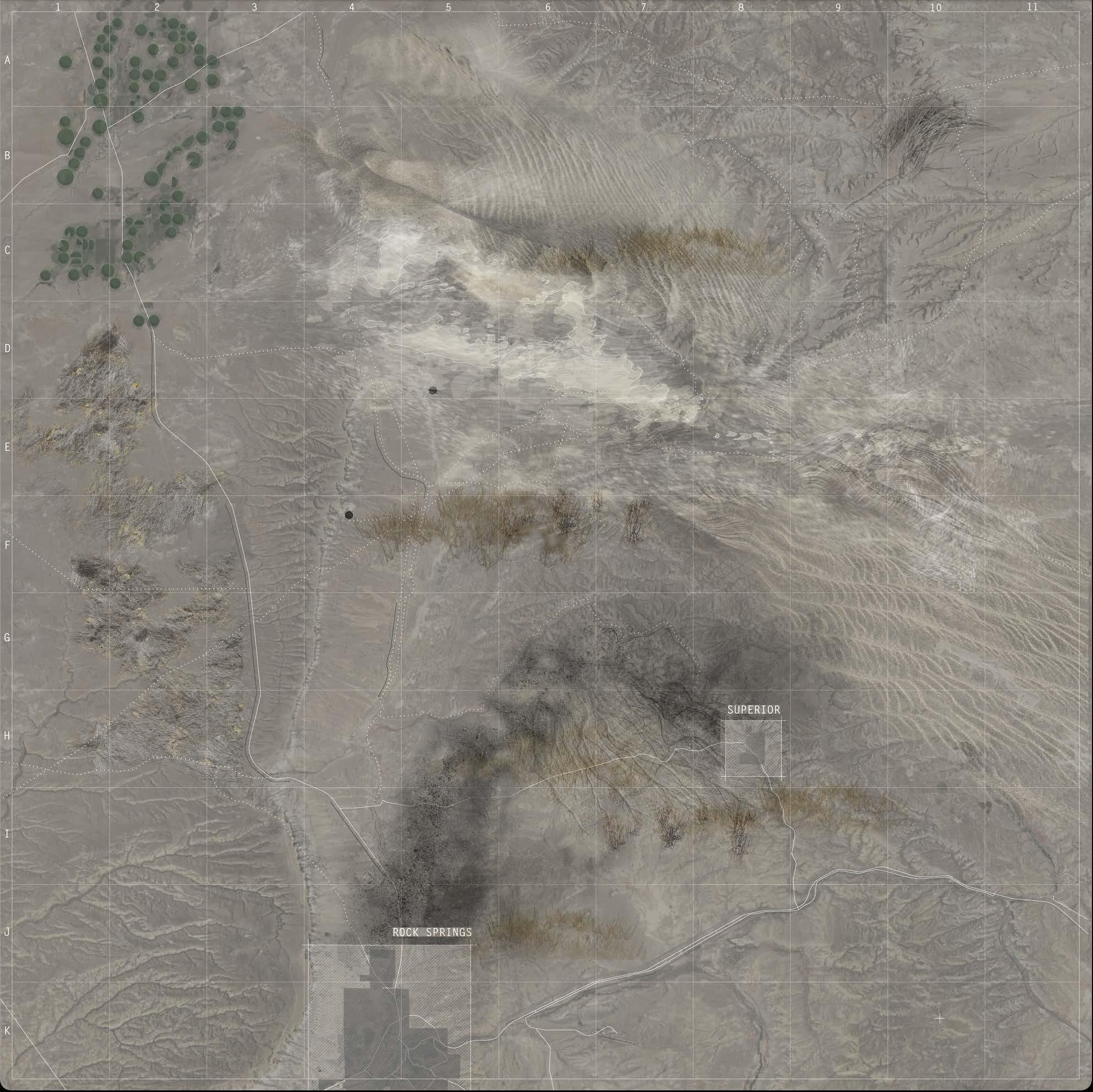

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

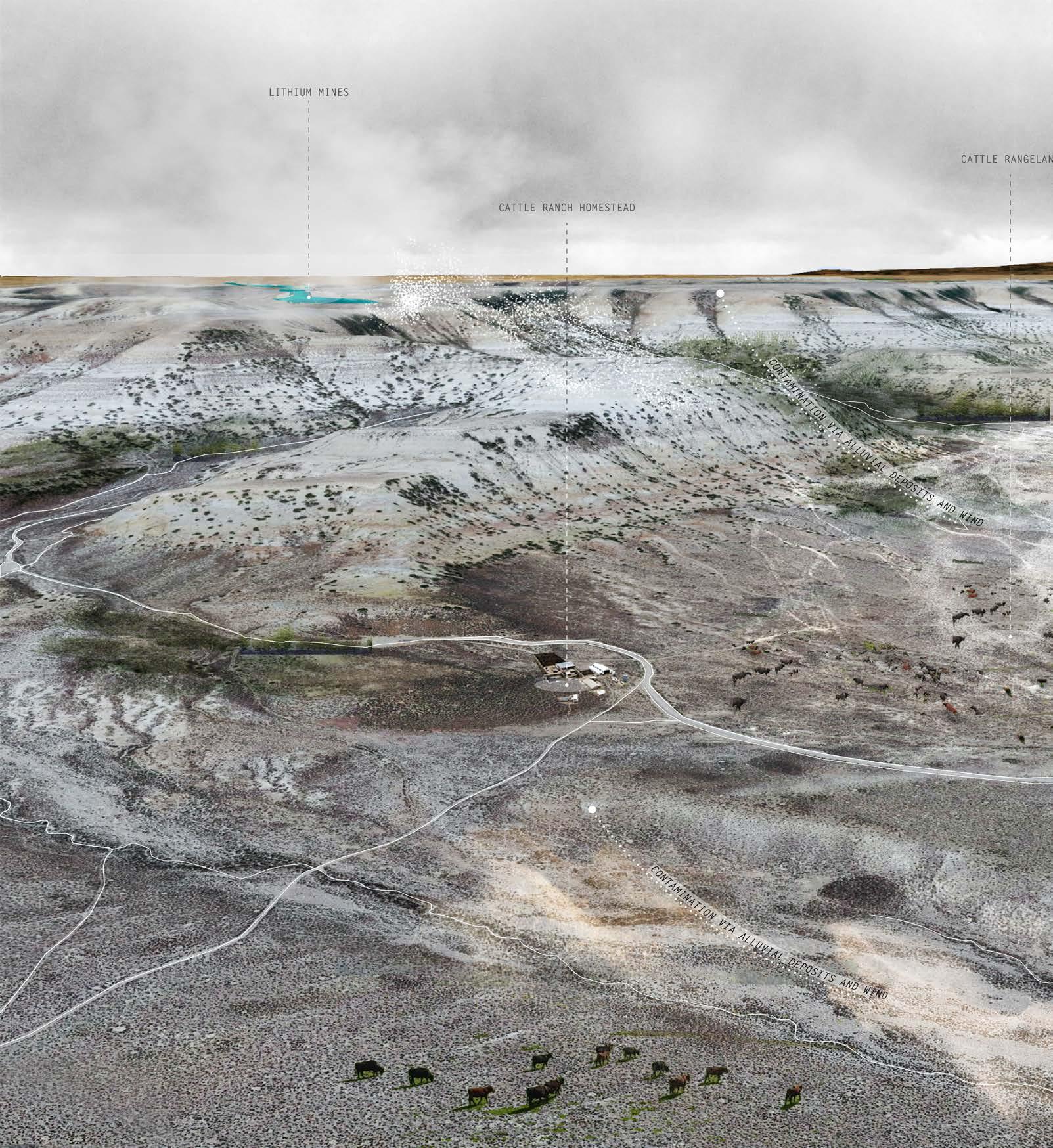

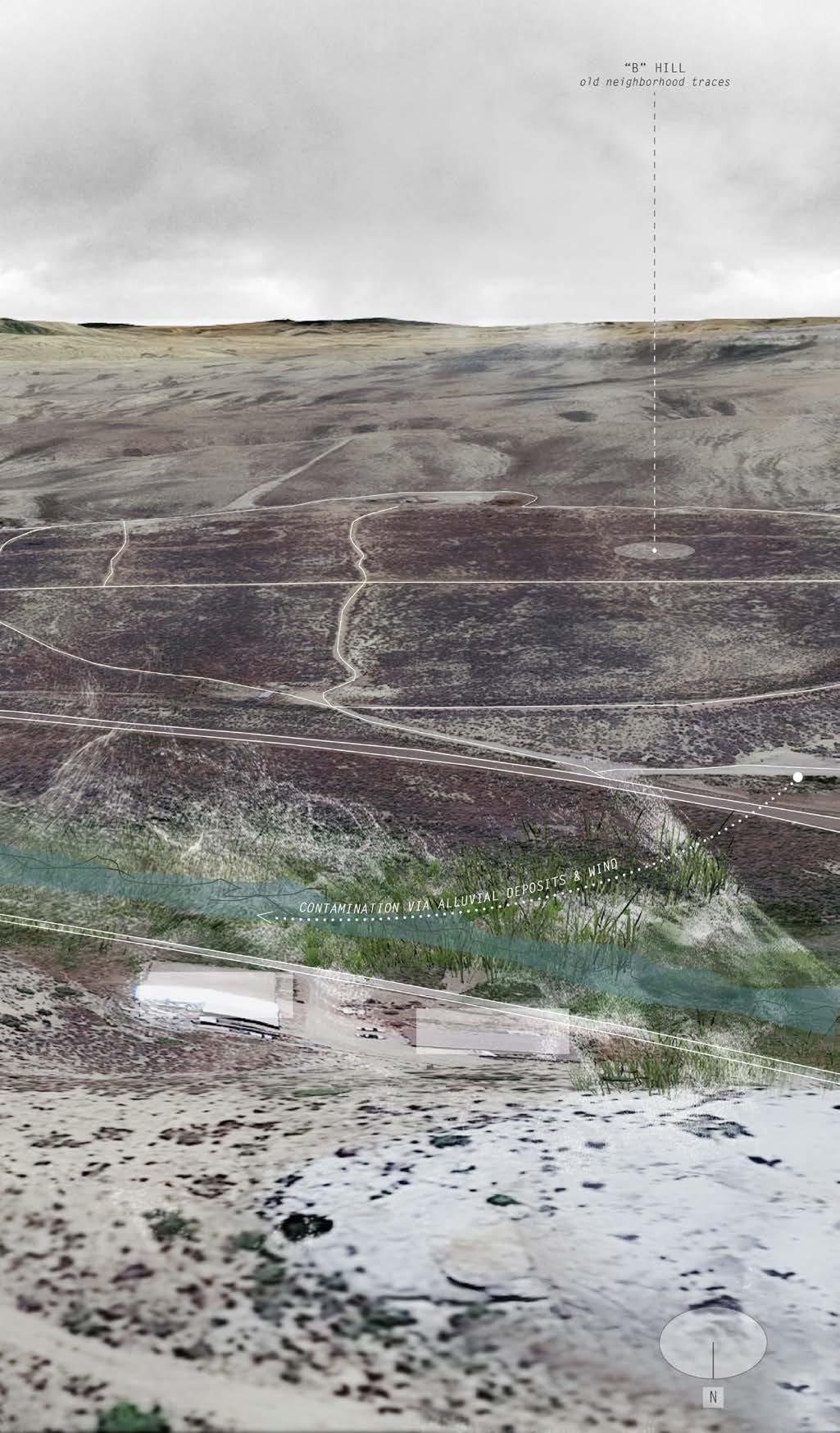

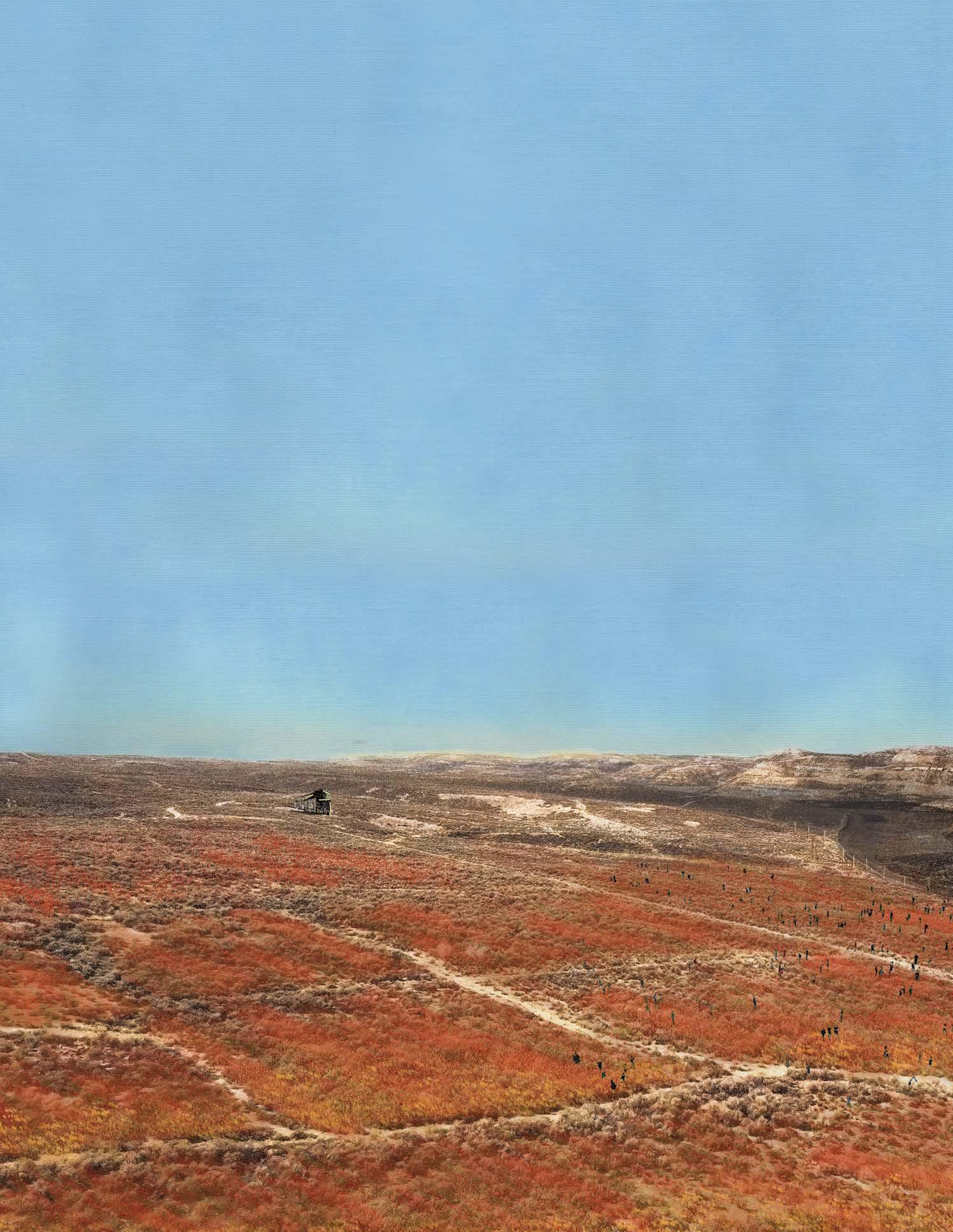

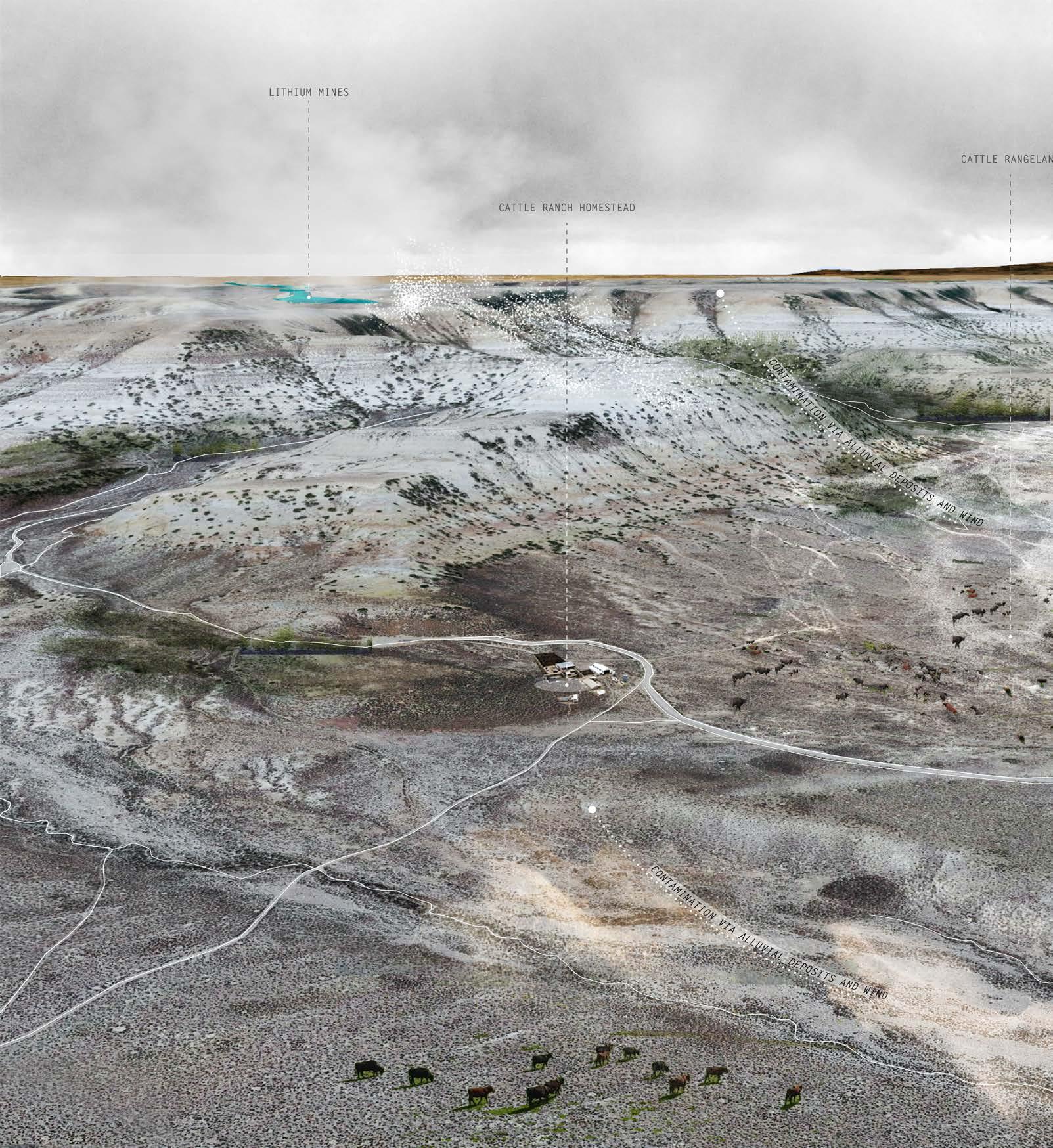

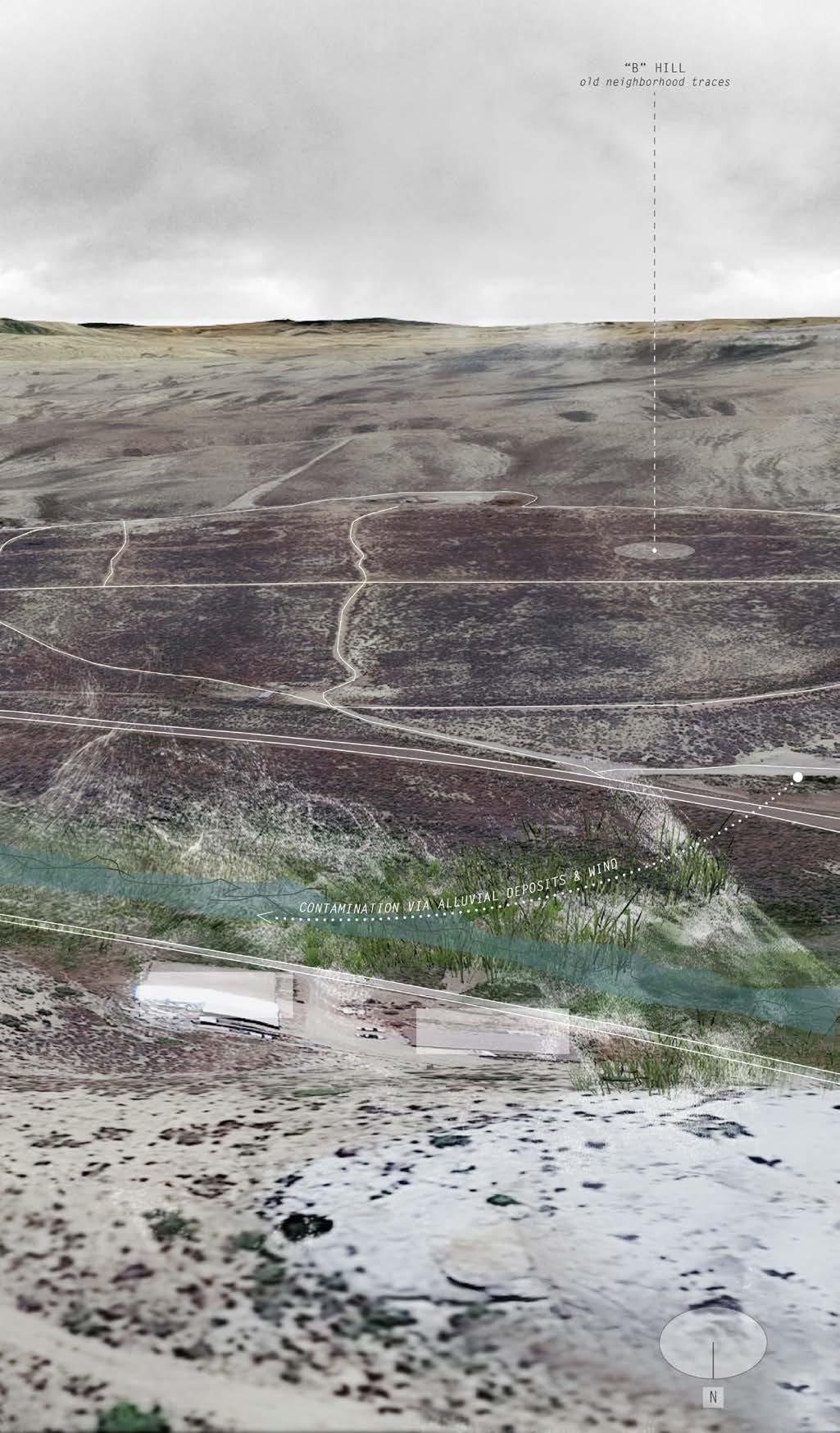

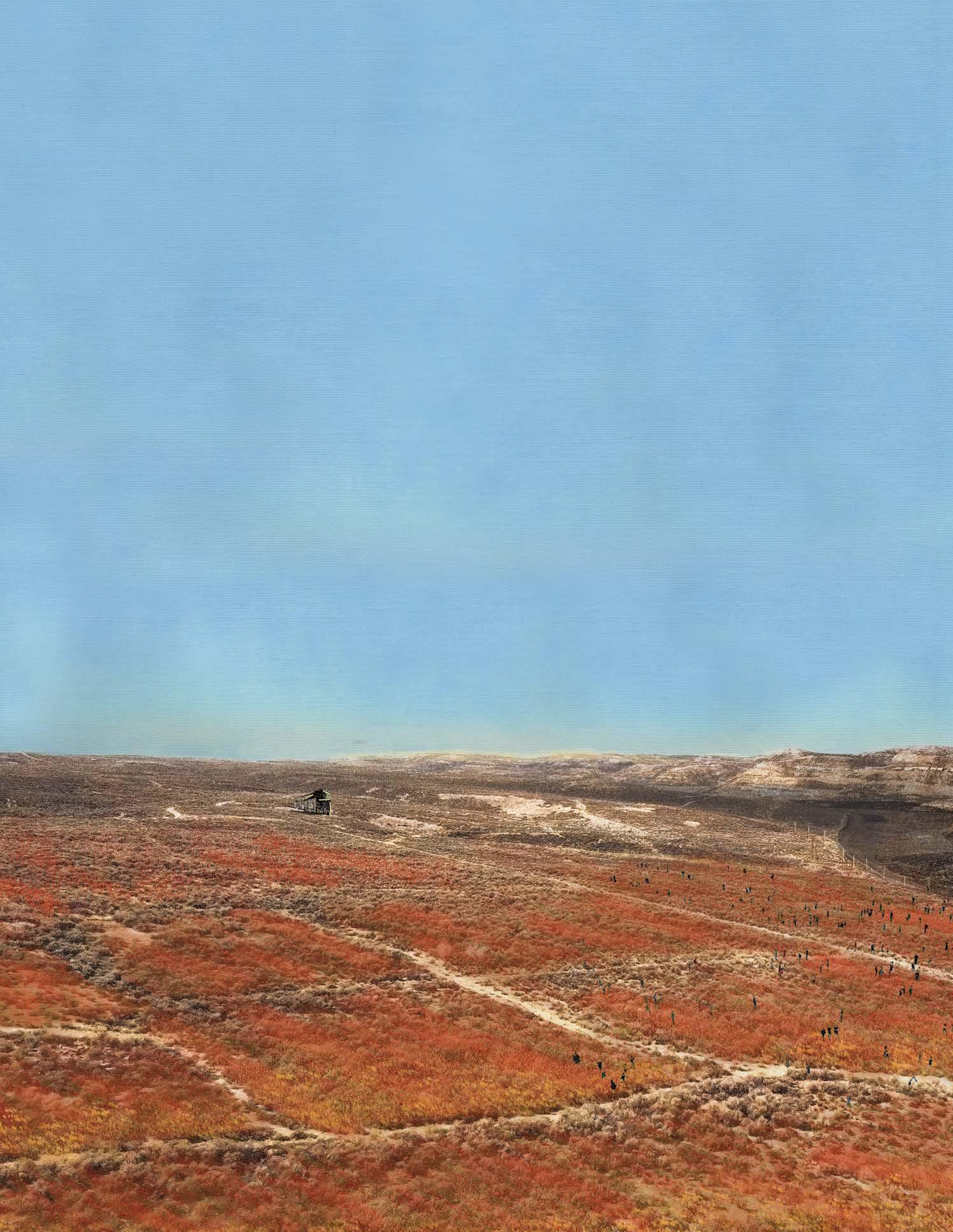

SITE OF FUTURE LITHIUM MINE BEFORE CONSTRUCTION

The mine will contaminate surrounding seasonal alluvial plains that flood during seasons of snowmelt. Wildlife like antelope, prairie dogs, and deer will be disturbed as their habitats dry due to the operation of the mine. The lithium deposits are located on BLM (Bureau of Land Management) Land, which was previously open range for cattle grazing.

41

IV An Electrified Landscape

42

PHASE II

43

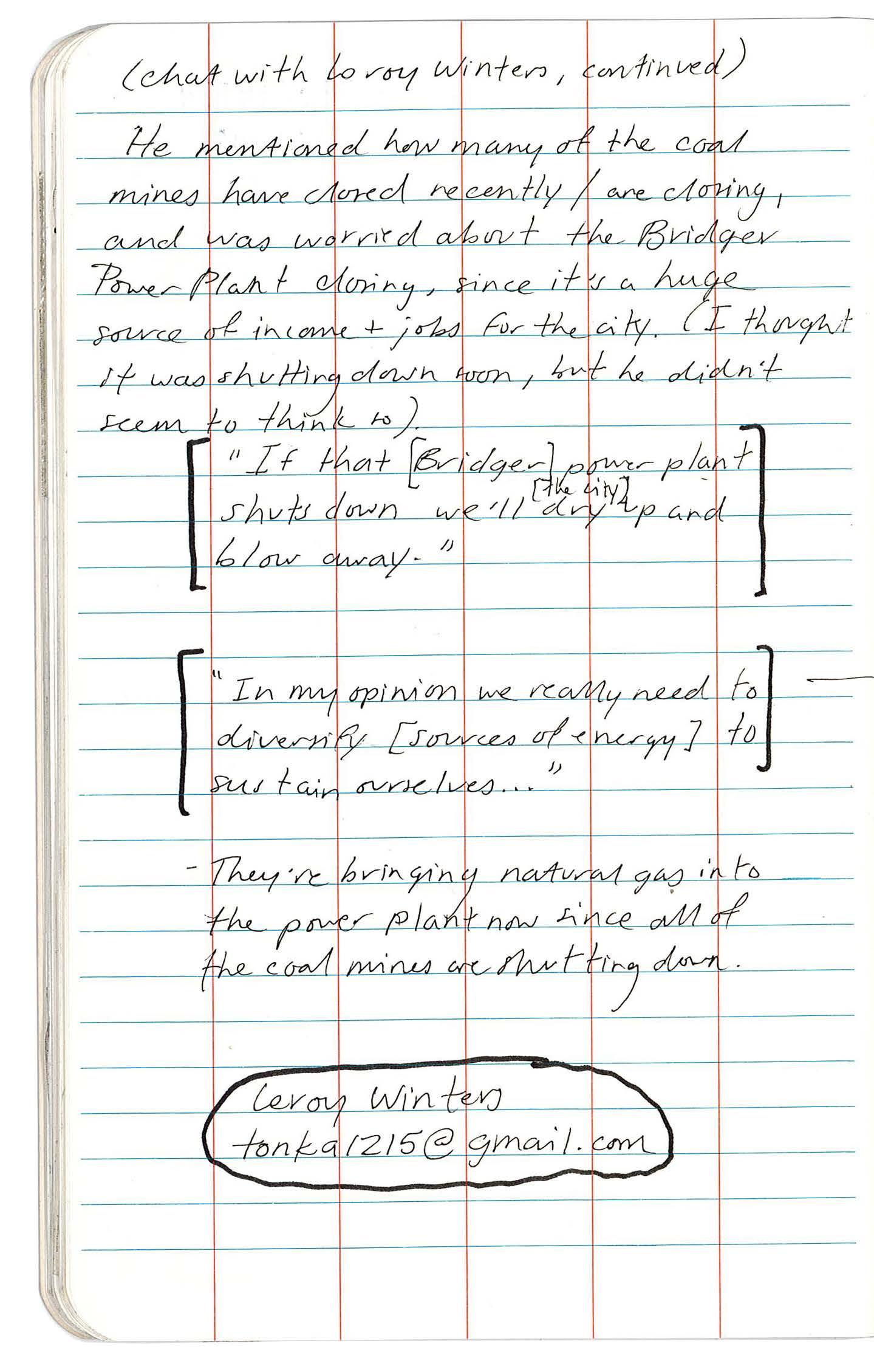

-Leroy Winters, who manages Superior’s water supply

44 V

“You’re doing your thesis on Superior? That hasn’t gotta be easy.”

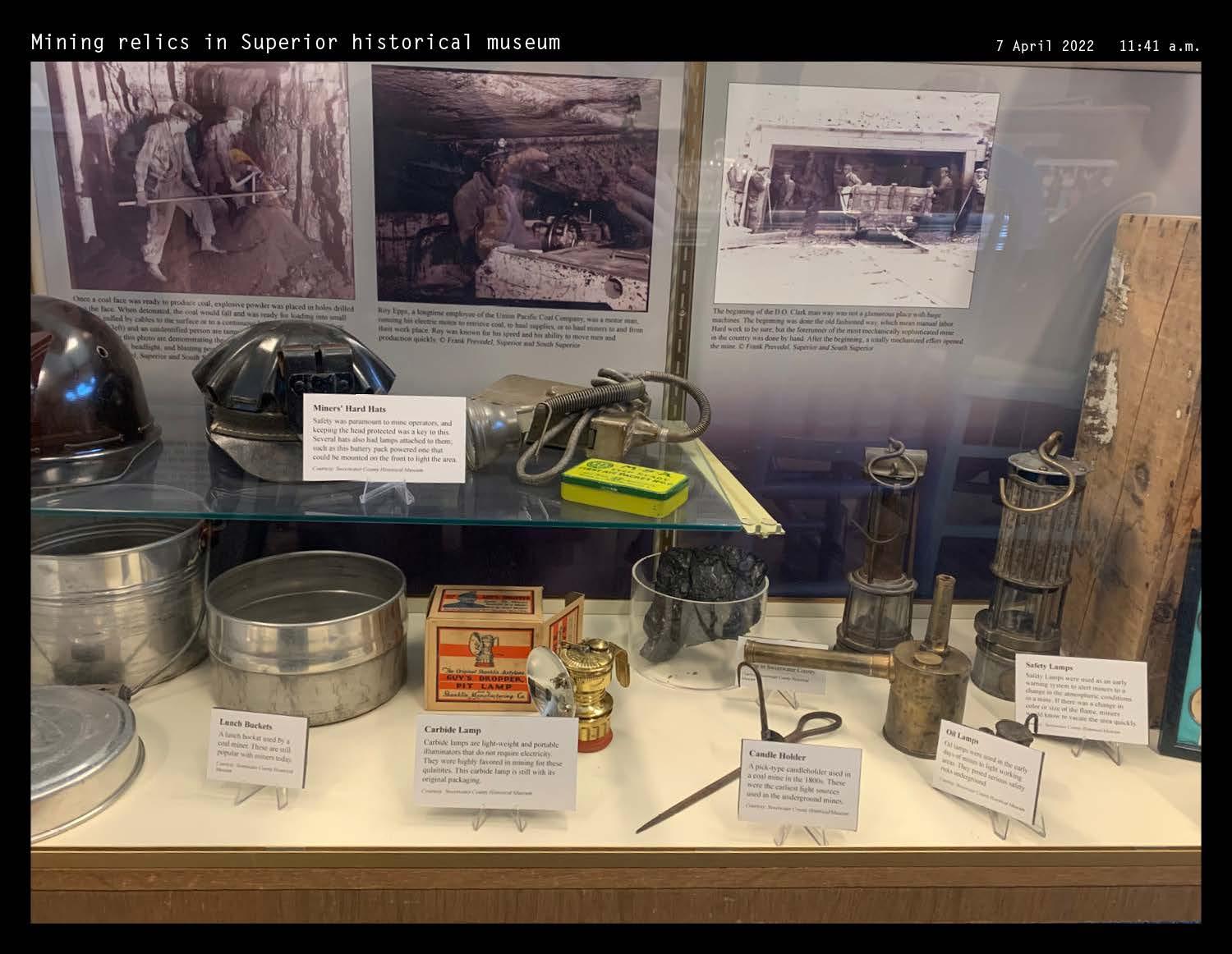

Historical information from: (Prevedel 2011)

SUPERIOR AND ROCK SPRINGS HISTORICAL ARCHIVE

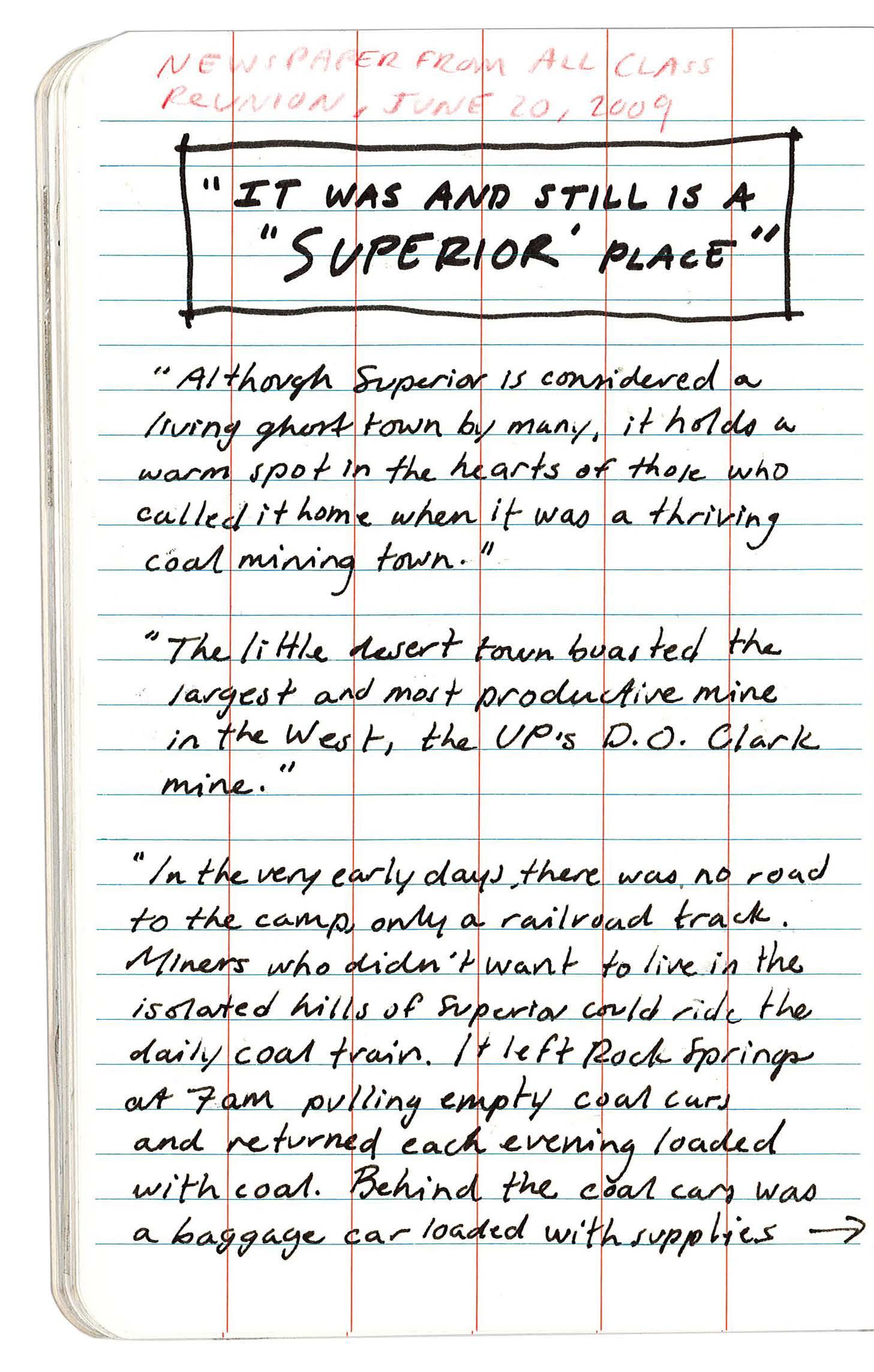

A Living Ghost Town

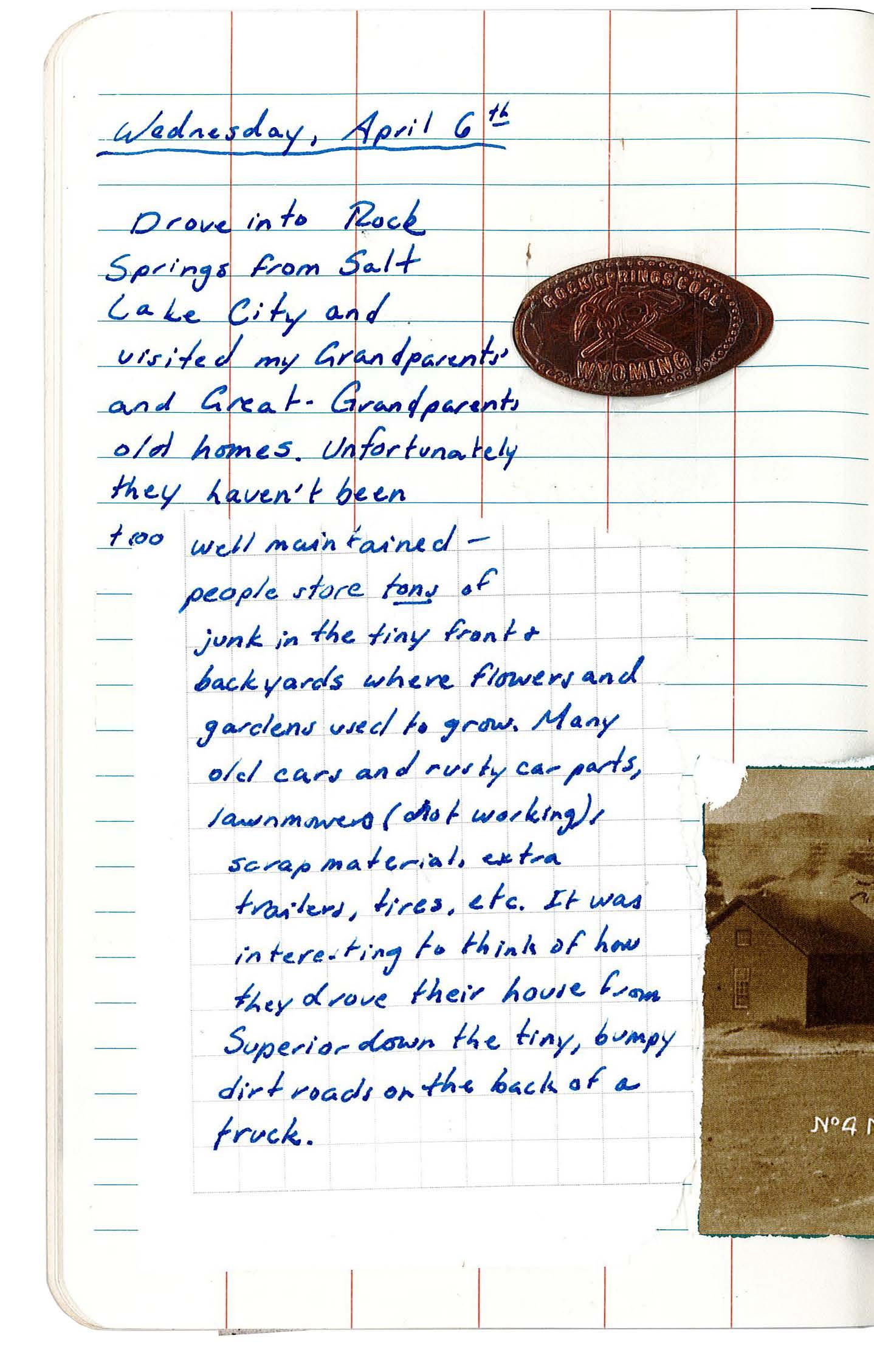

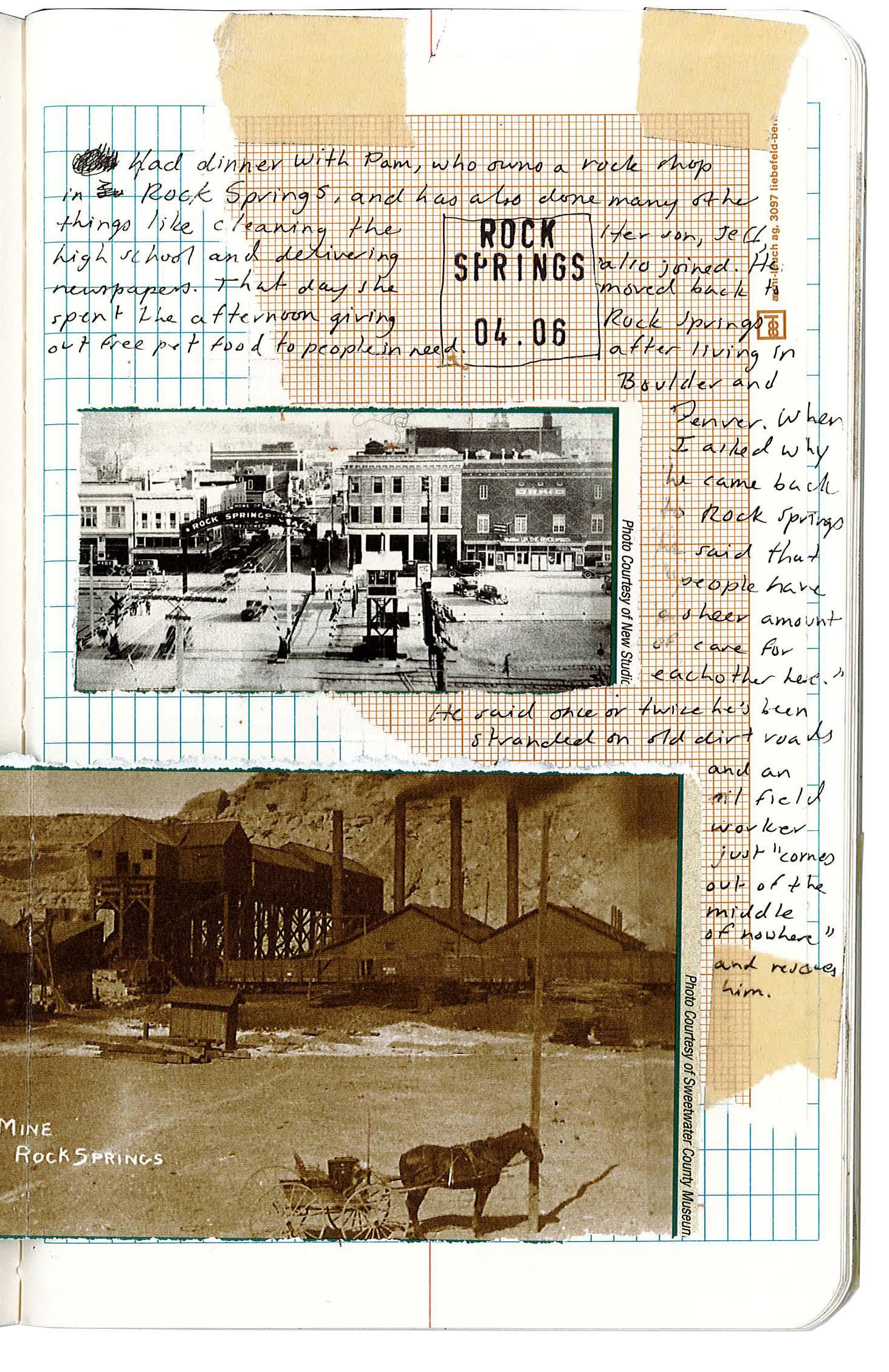

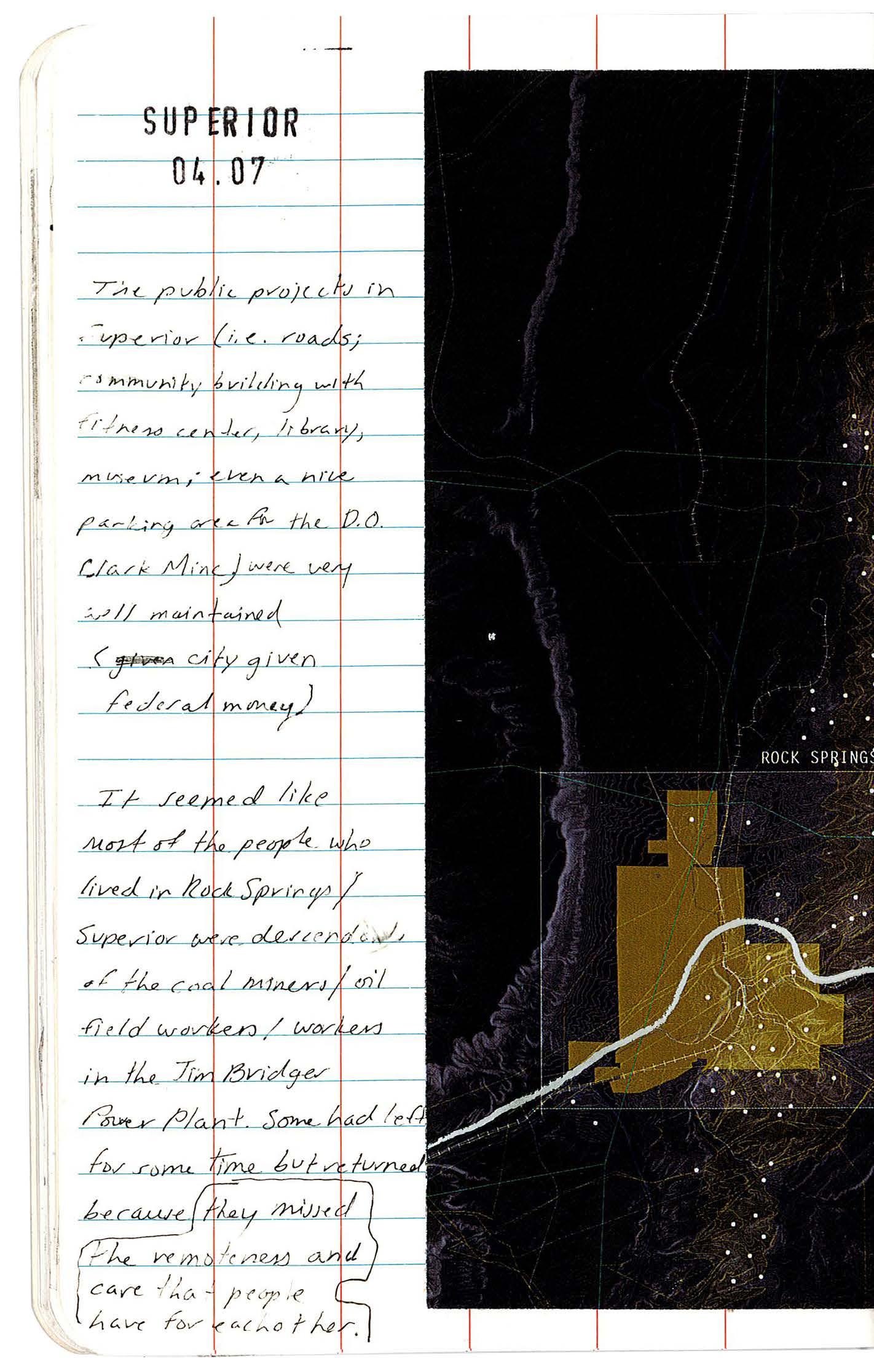

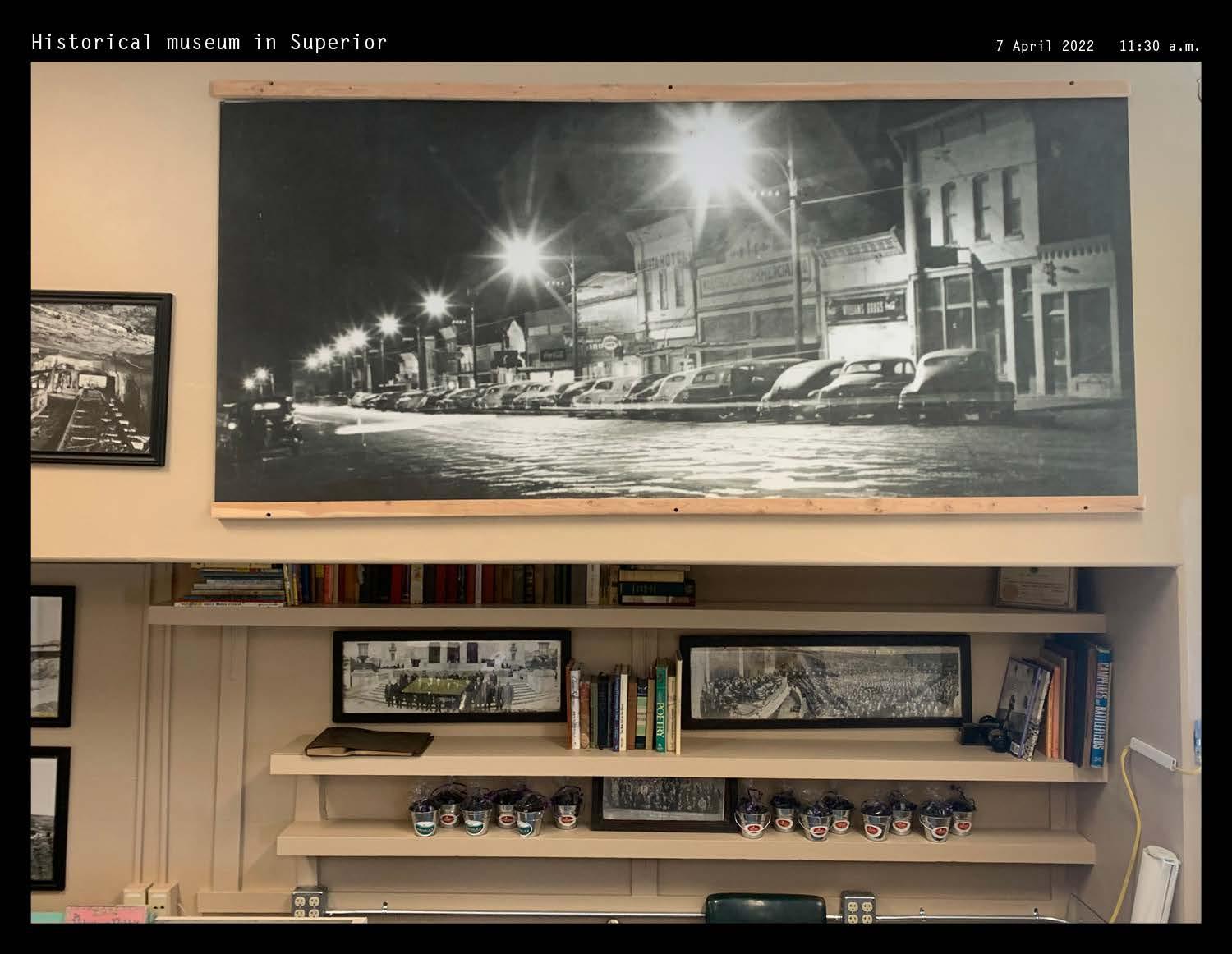

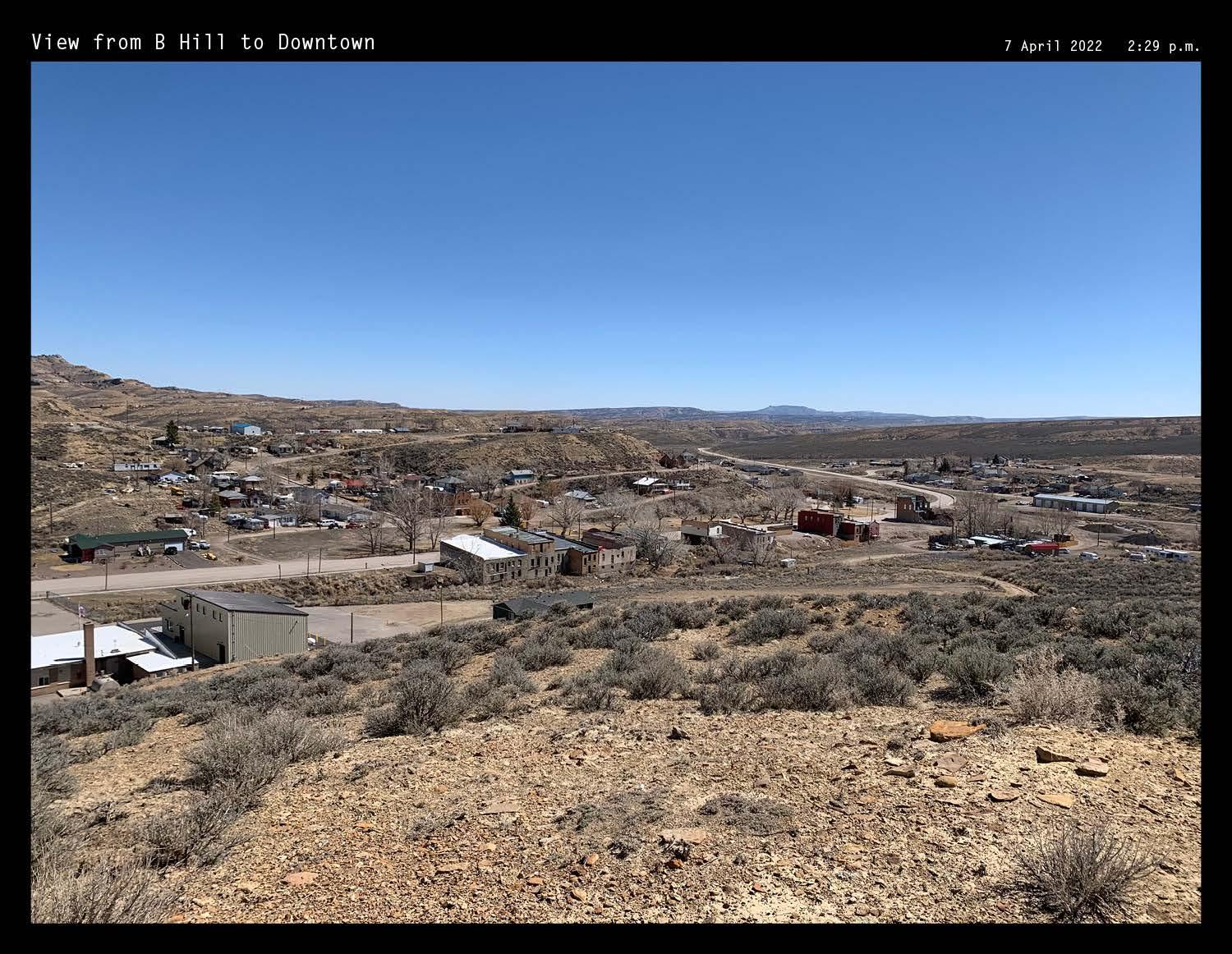

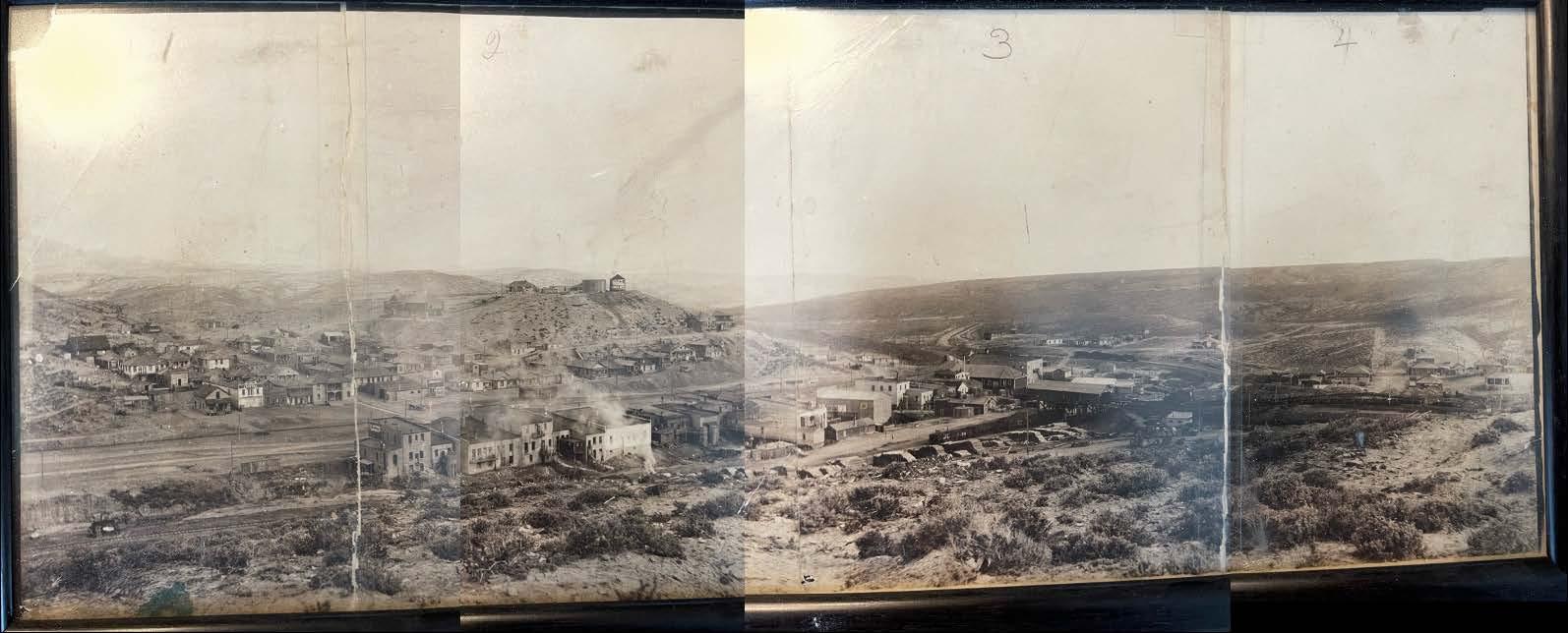

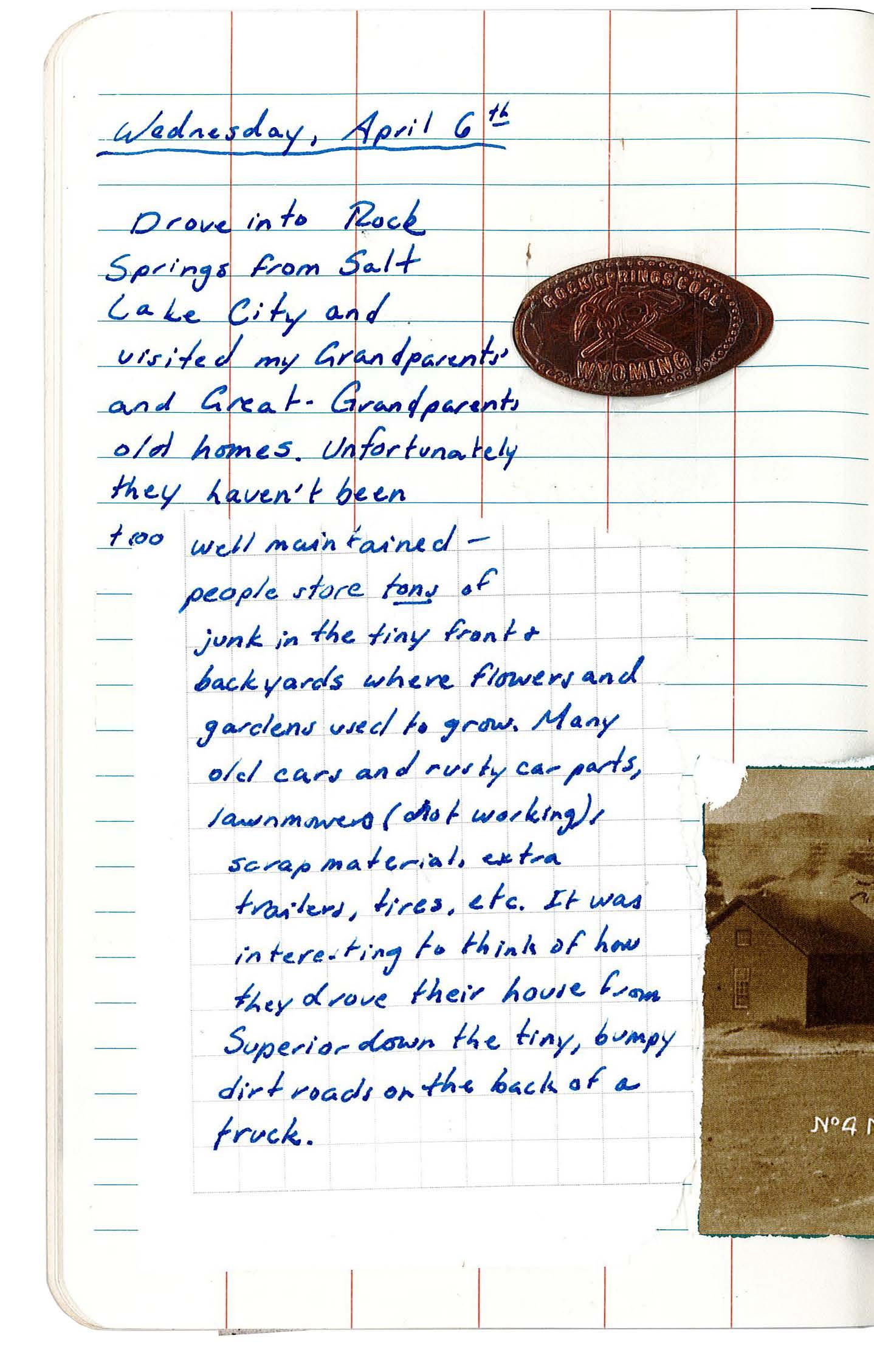

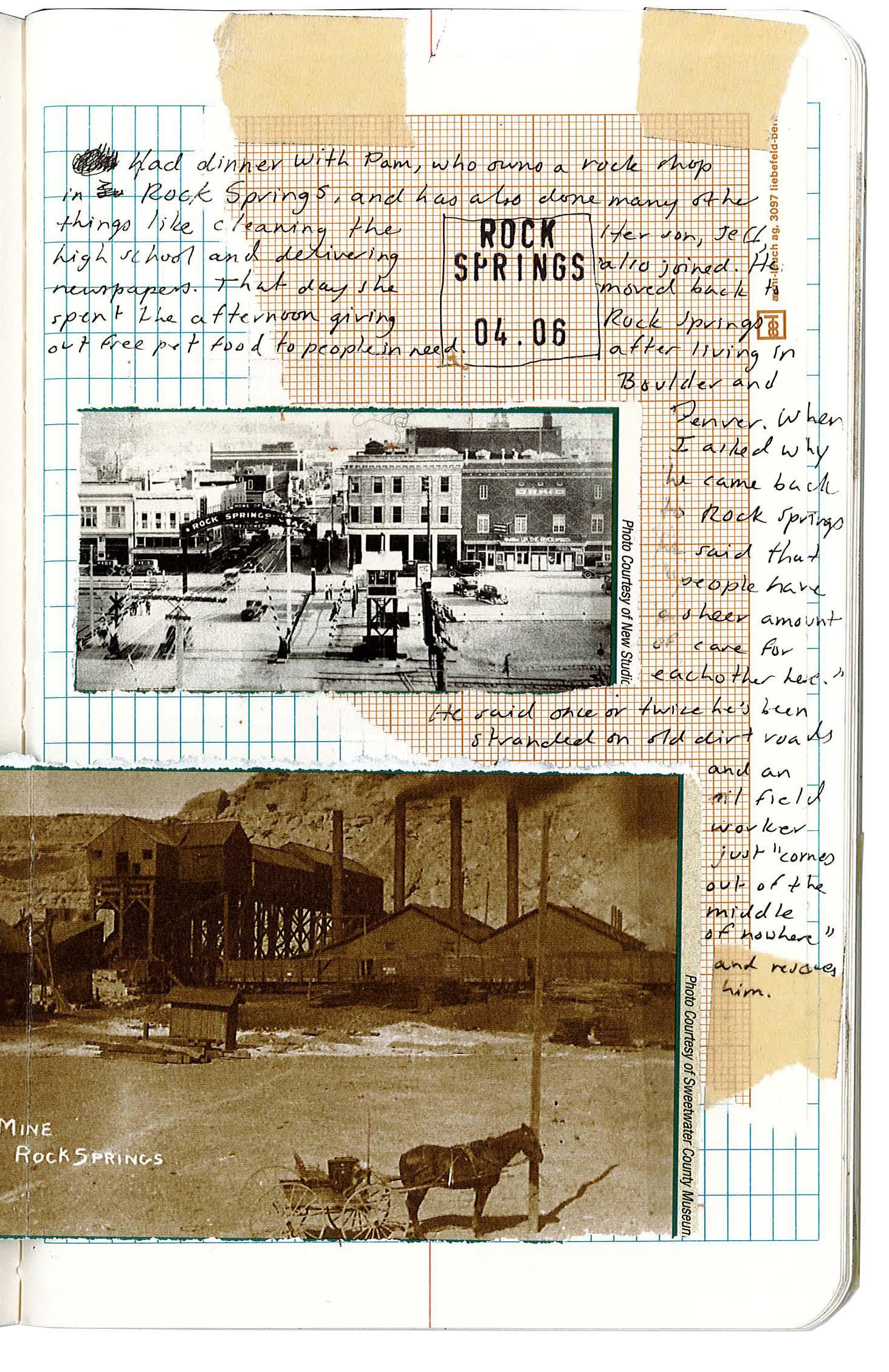

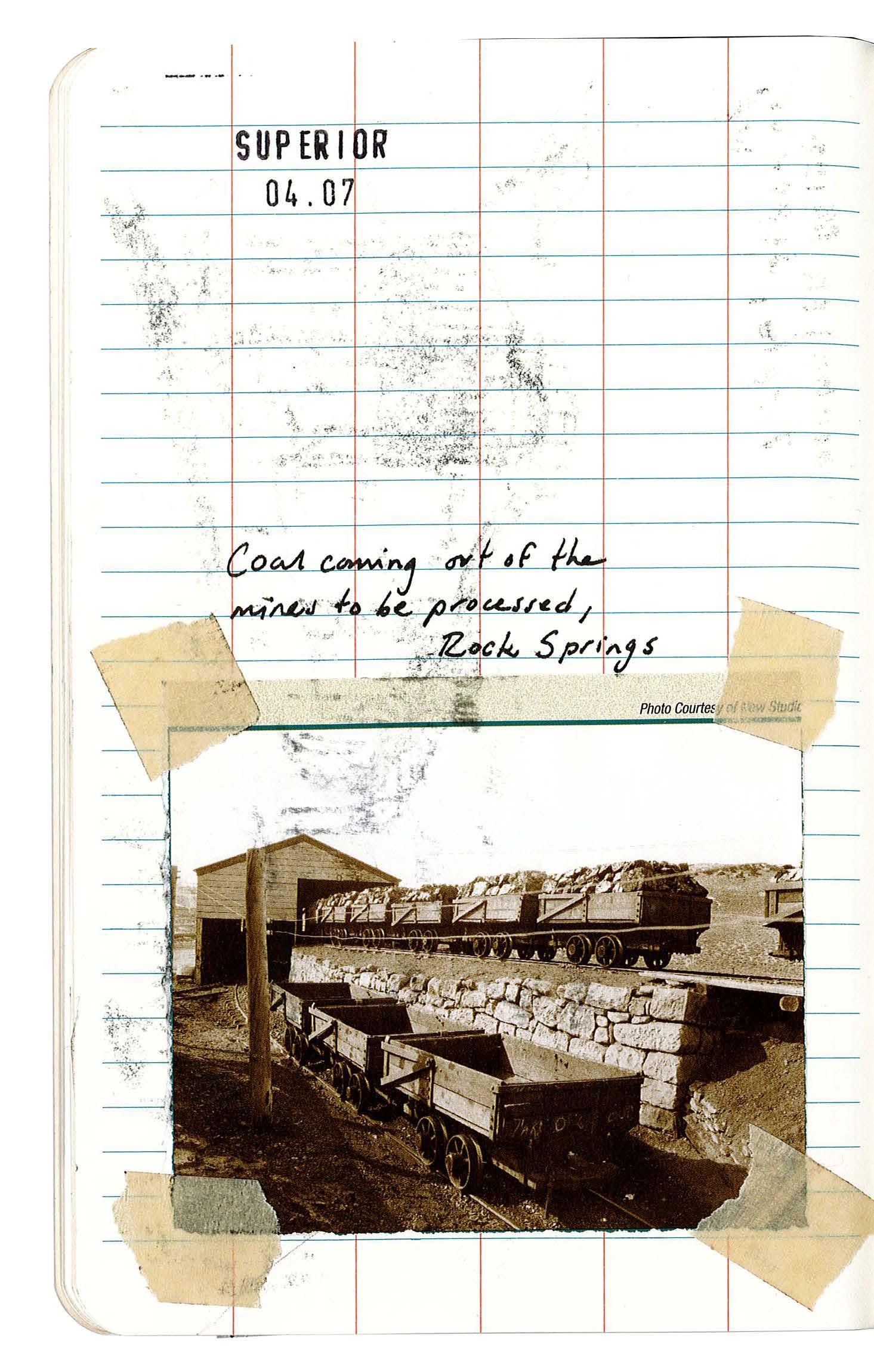

Superior and Rock Springs, located in southwestern Wyoming in an area rich with coal outcrops and natural gas deposits, offer a vivid example of how the livelihood of energy towns and the health of the environment rest on the extraction industry. These two towns have a personal story for me, as my grandparents, William and Francis Sines, grew up here working in the historic coal mines.

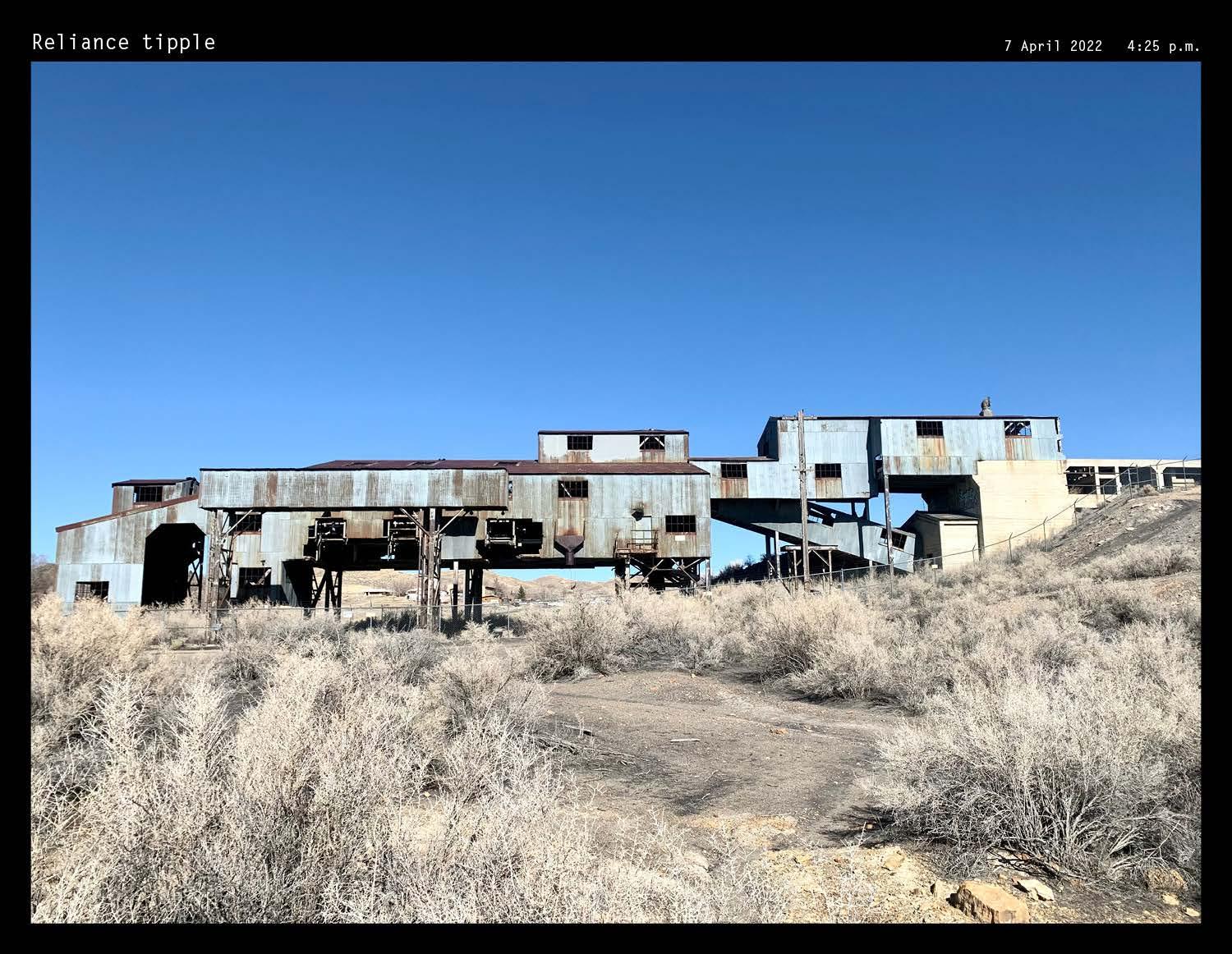

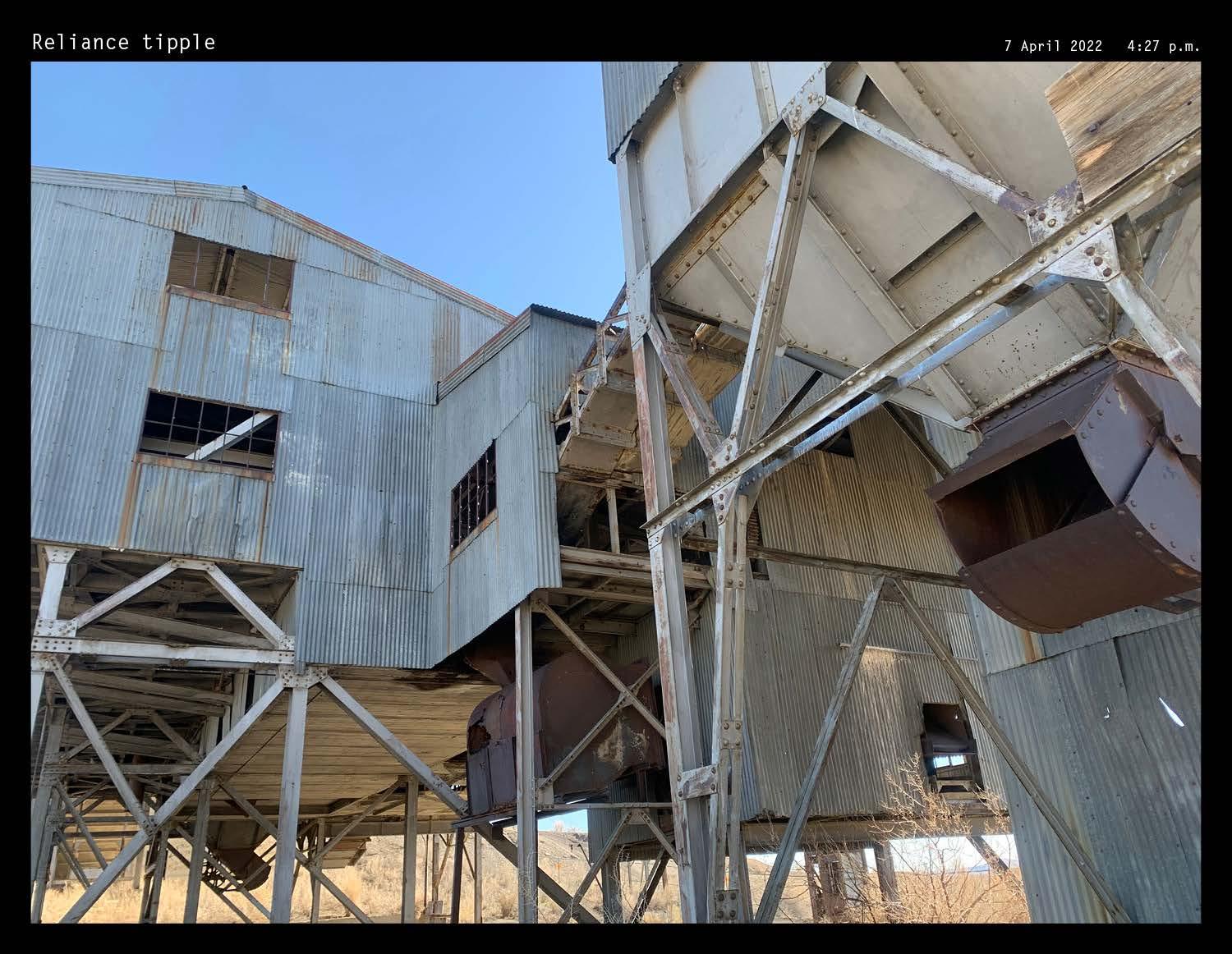

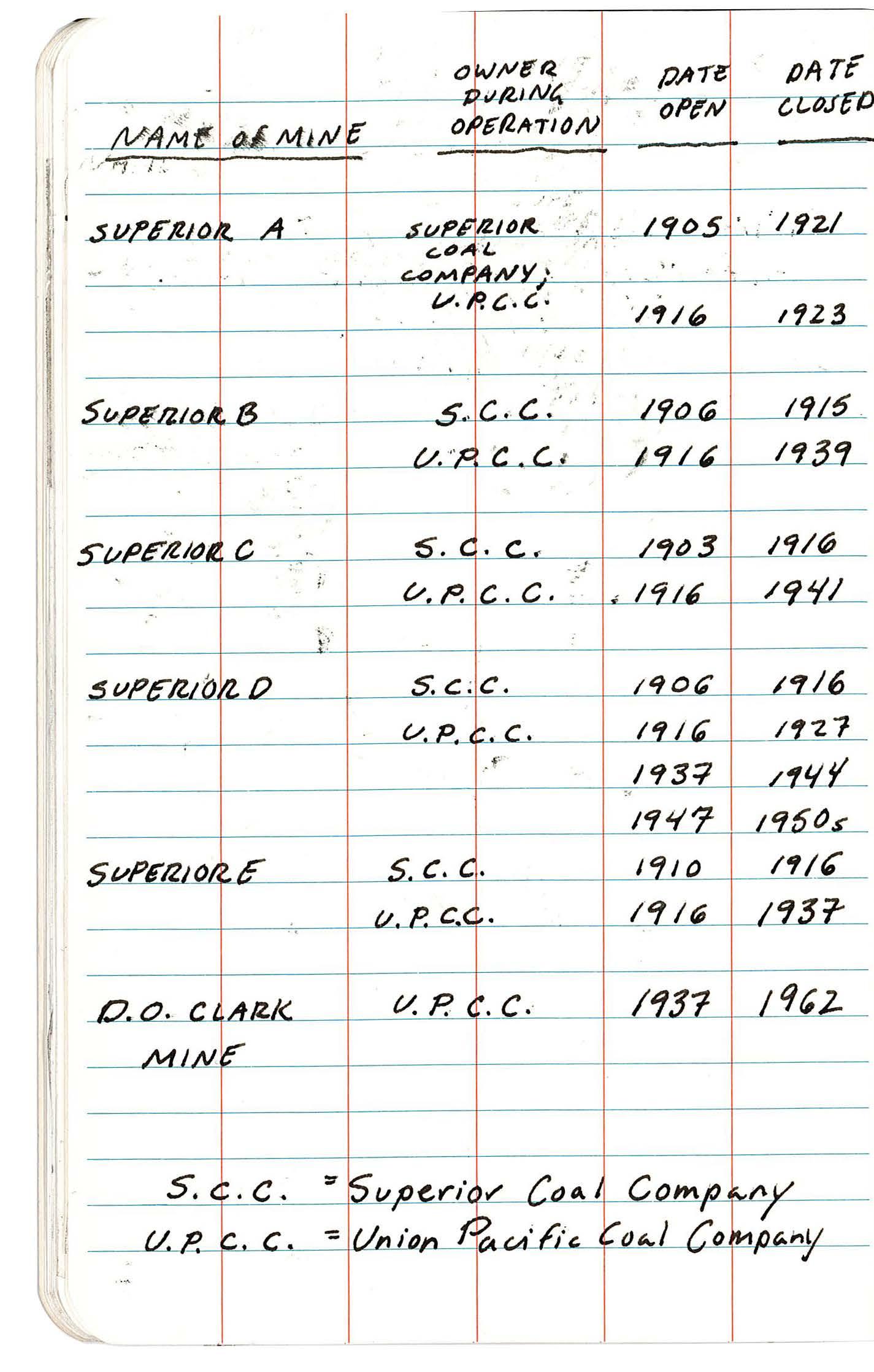

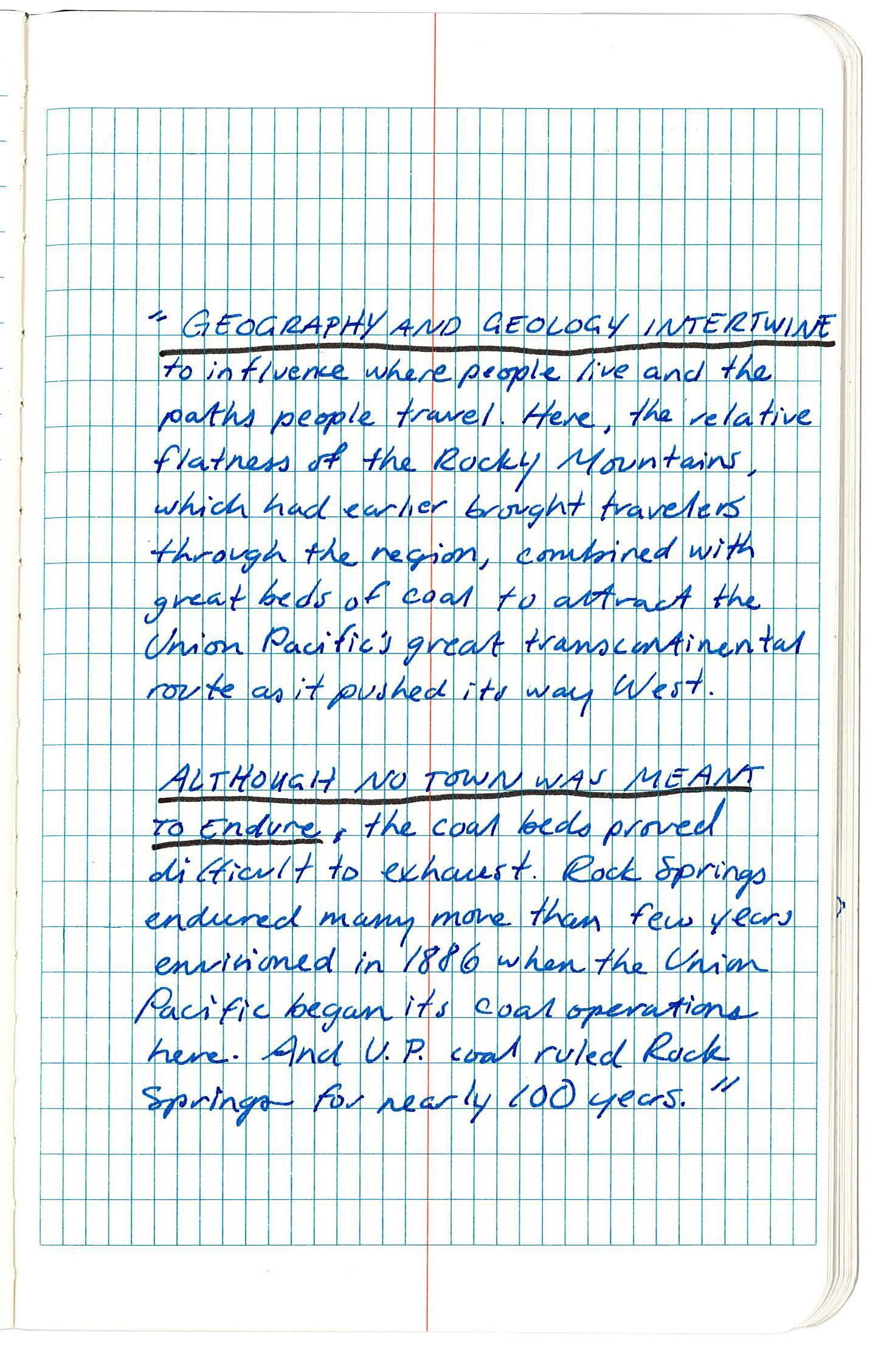

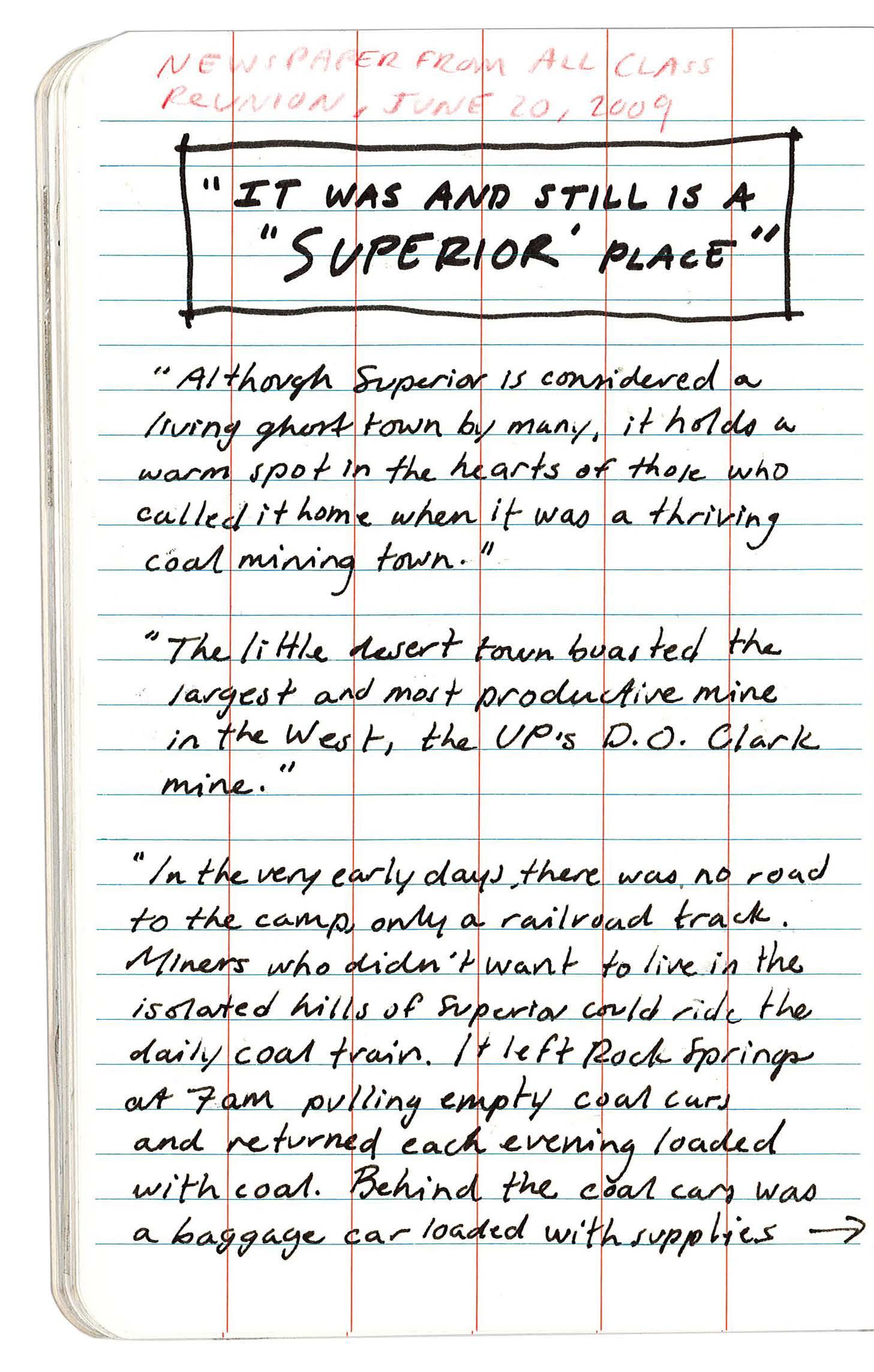

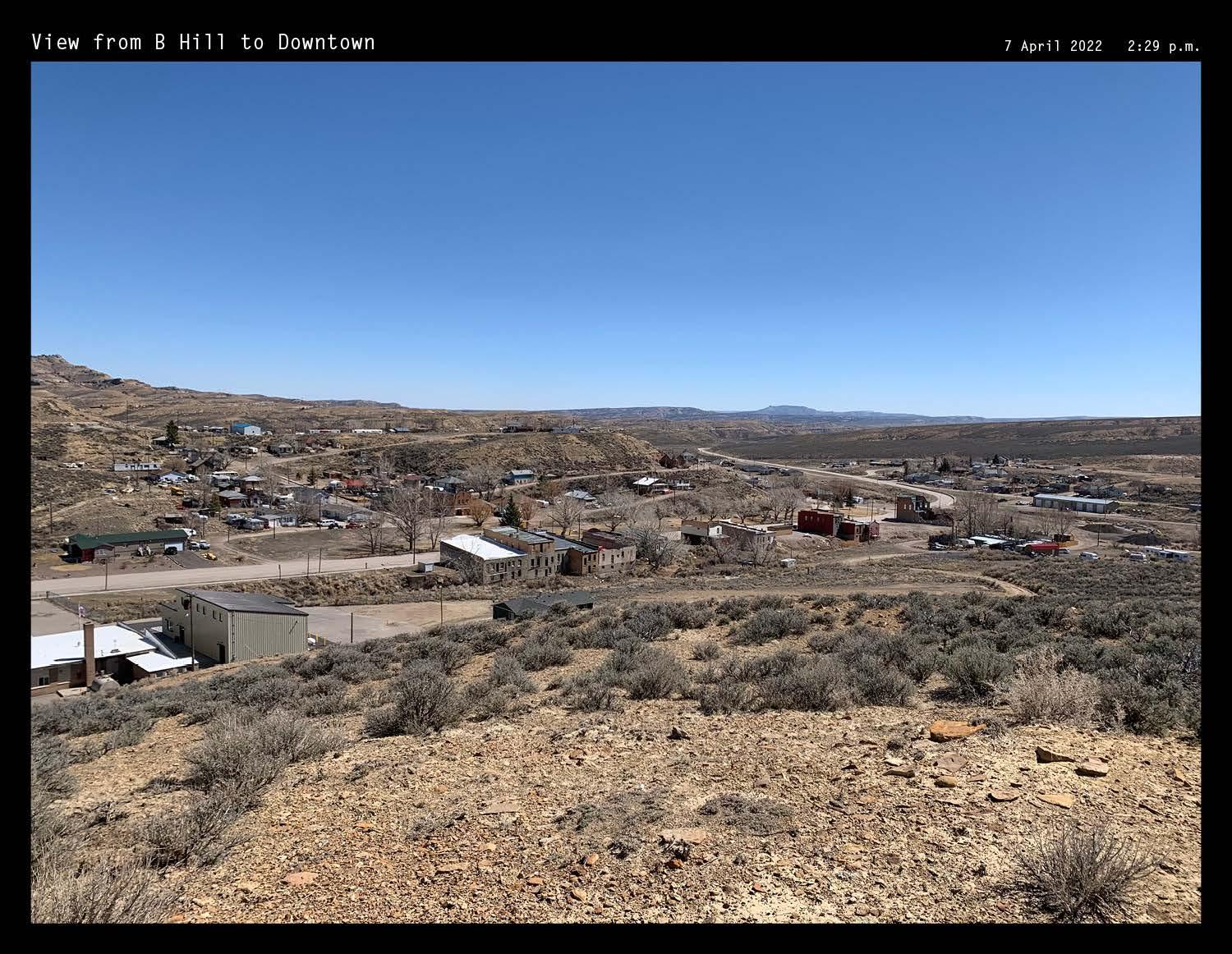

The town of Superior had its origins in the coal boom days around the turn of the century. The town grew to its largest population in the mid-1940s when, during World War II, hundreds of migrant workers came to the mines, living in homes fashioned from boxcars. Geography and geology intertwined to influence where people lived, worked, and the paths they traveled. Although none of these historic extractive towns were meant to endure, the coal beds proved difficult to exhaust. Superior and Rock Springs endured many more than the few years envisioned in 1866 when the Union Pacific Railroad began its coal operations.

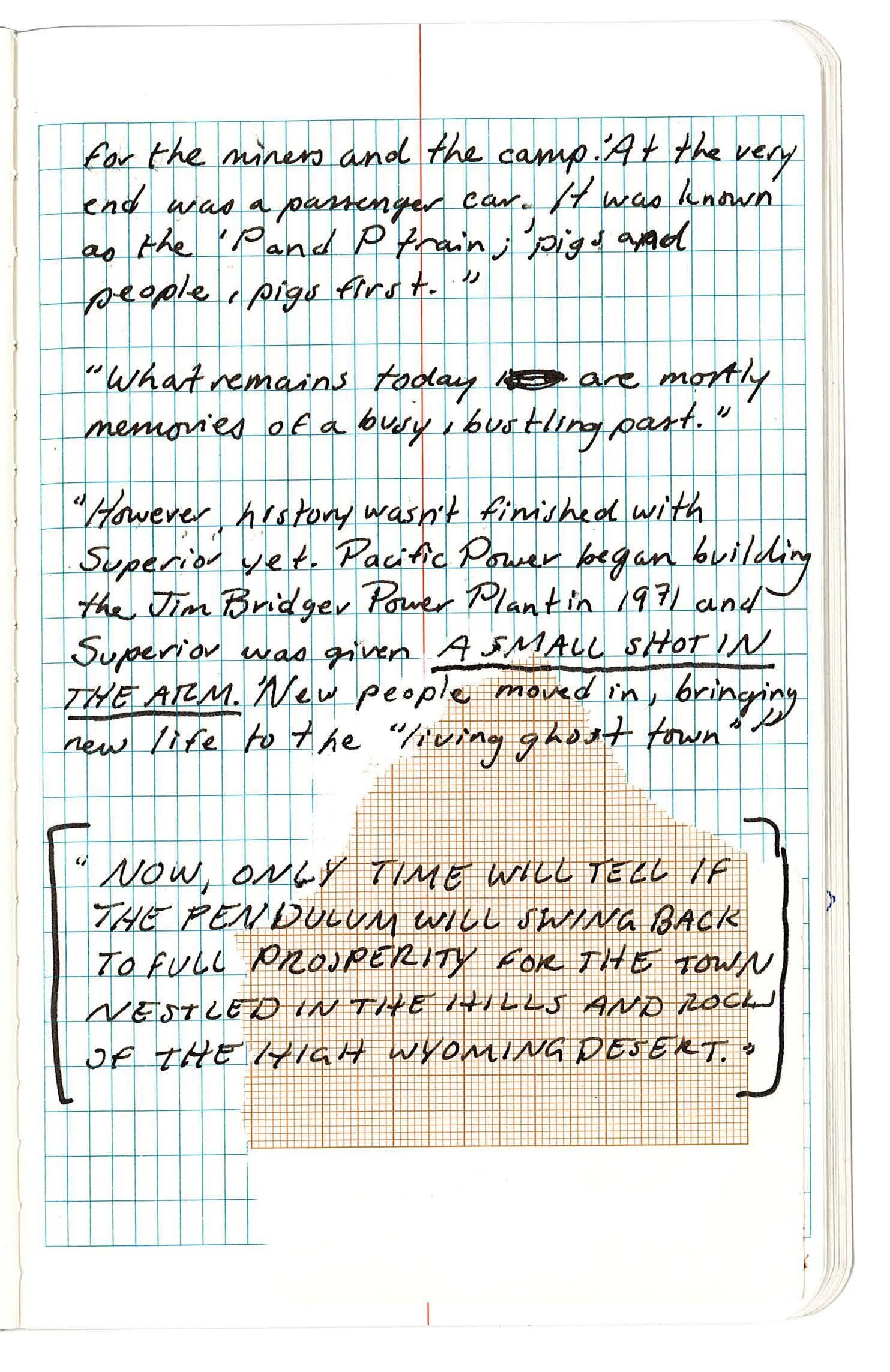

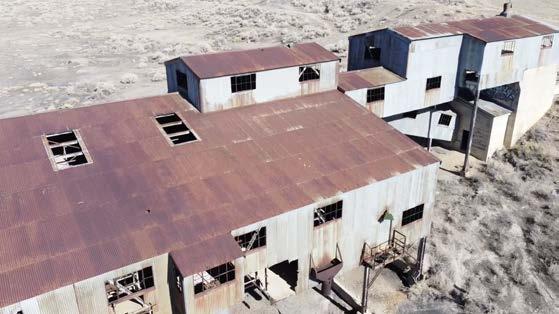

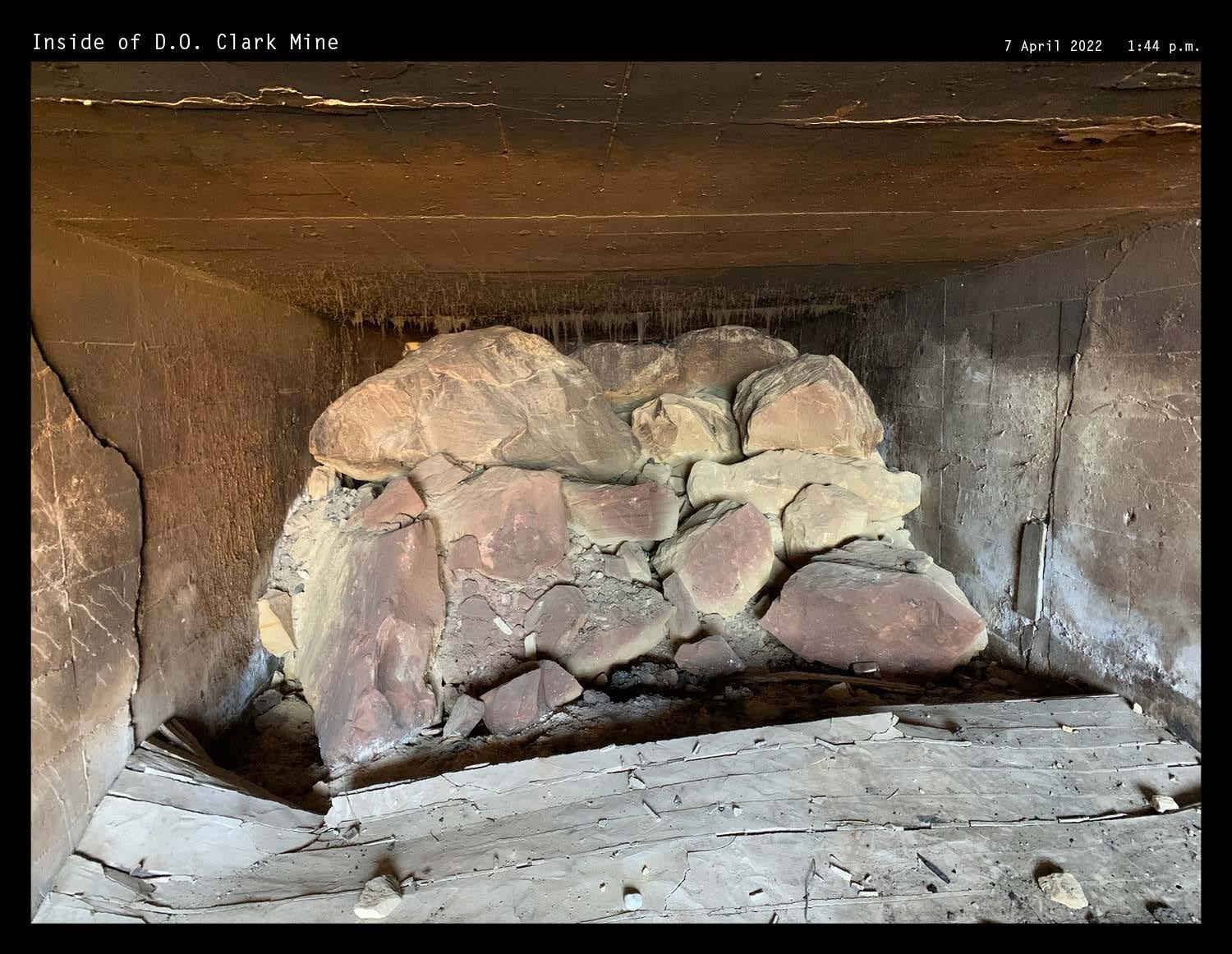

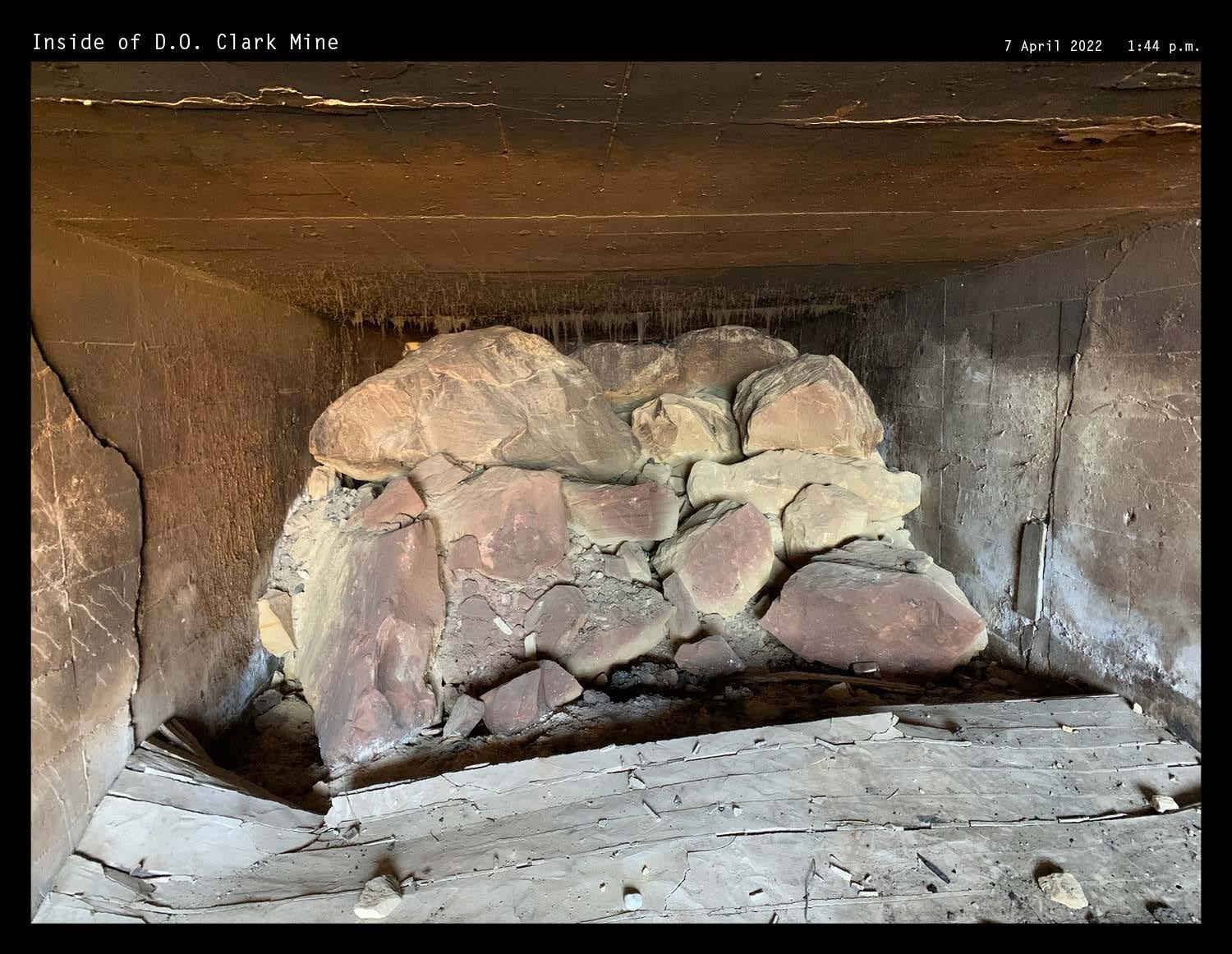

What remains today are mostly memories of a busy, bustling past. With the advent of diesel fuel, the UPRR began slowly converting from coal to oil to power its locomotives. The coal market declined and eventually ended. Mine closures began in the 1950s, with the D.O. Clark Mine the last to close in 1962. With the closure, Superior declined in population, and business establishments closed.

However, history was not finished with Superior yet. Pacific Power began building the Jim Bridger Power Plant in 1971 and Superior experienced a brief population spike. New people moved in, bringing new life to the “living ghost town.” Now, only time will tell if Superior will swing back to full prosperity for the town nestled in the hills and rocks of the high Wyoming desert. With a future lithium mine, the exhausted coal town has a possibility of resurrection.

45

V

Historical Archive

Superior and Rock Springs

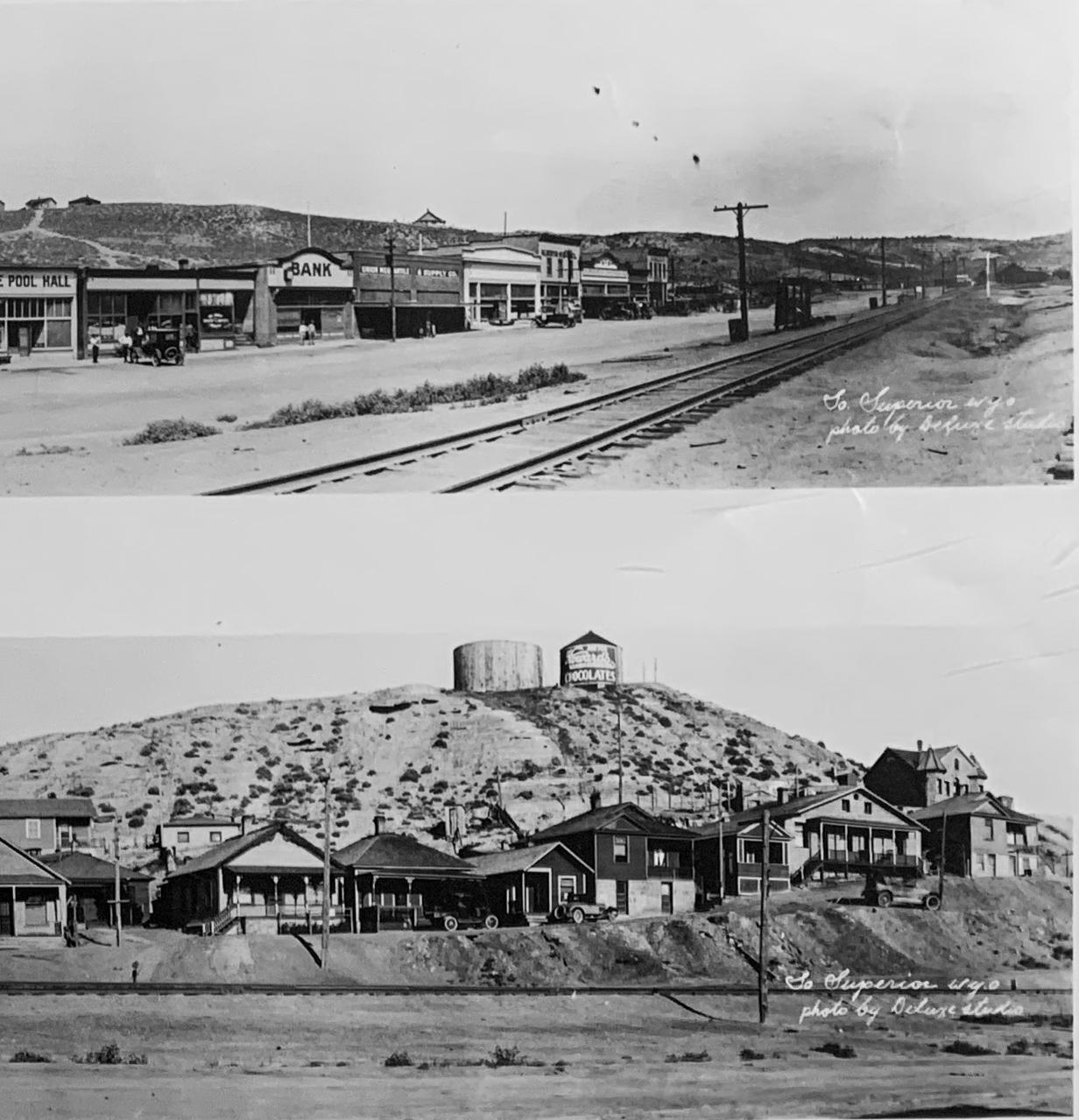

46 Historical information

2011)

from: (Prevedel

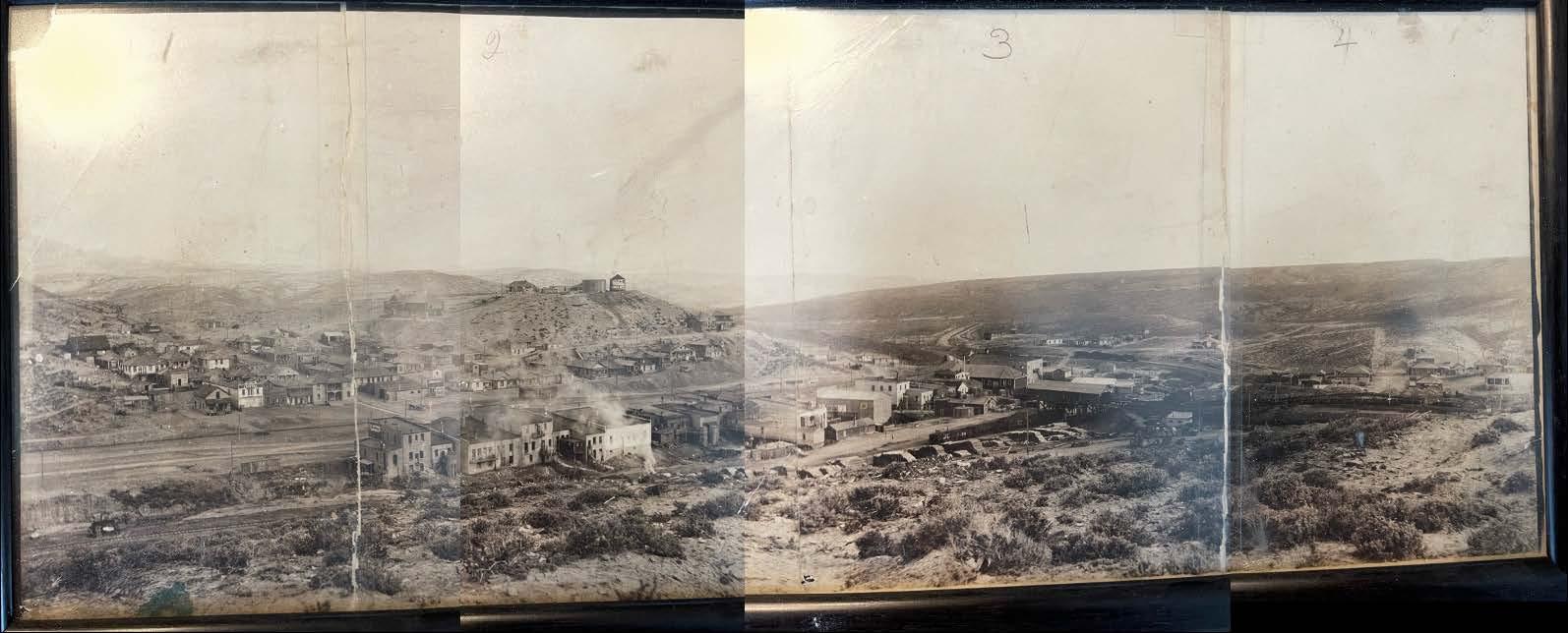

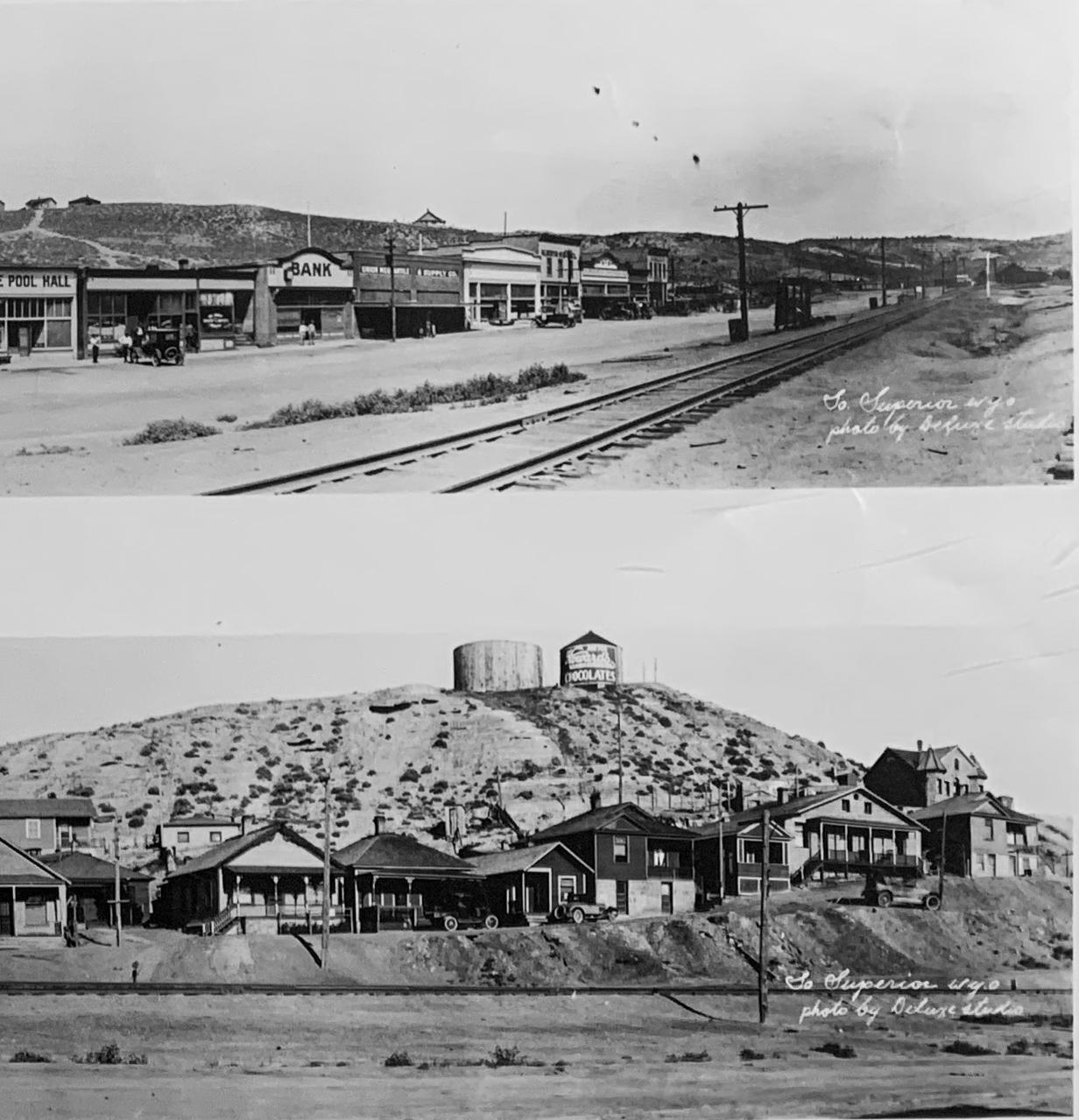

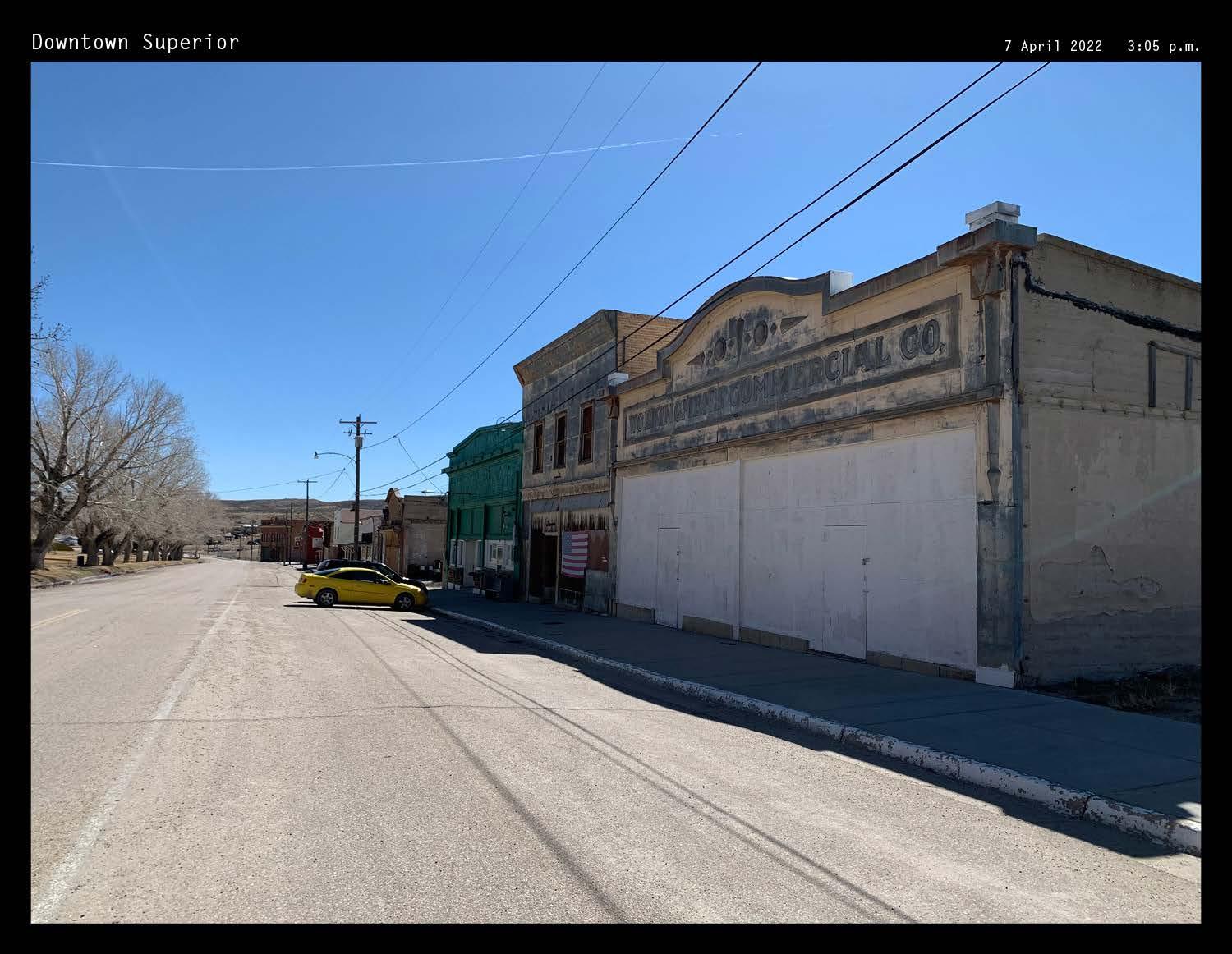

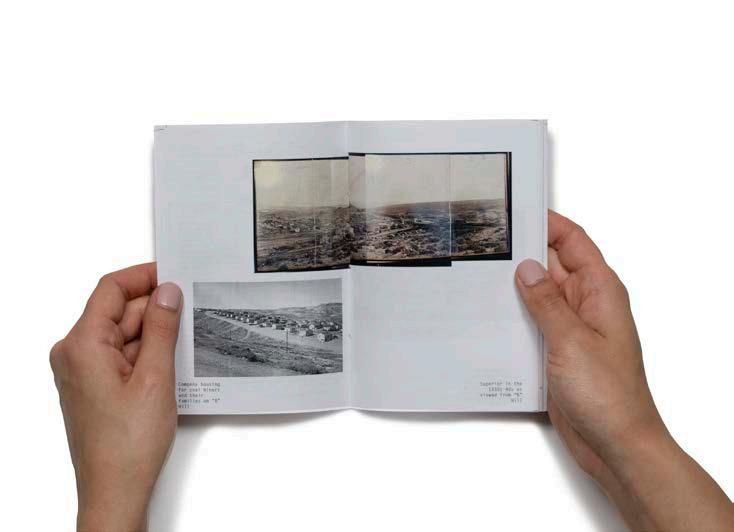

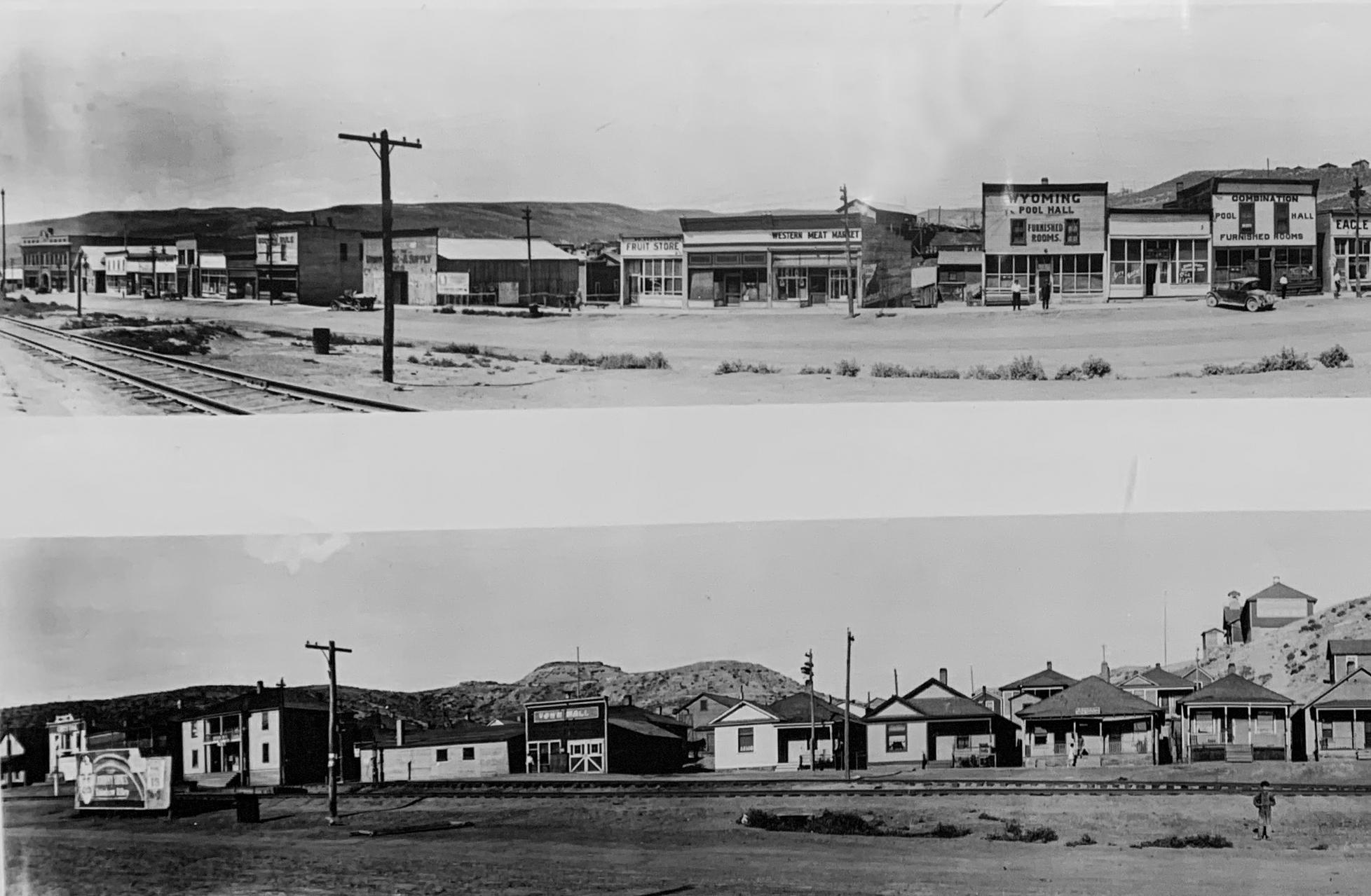

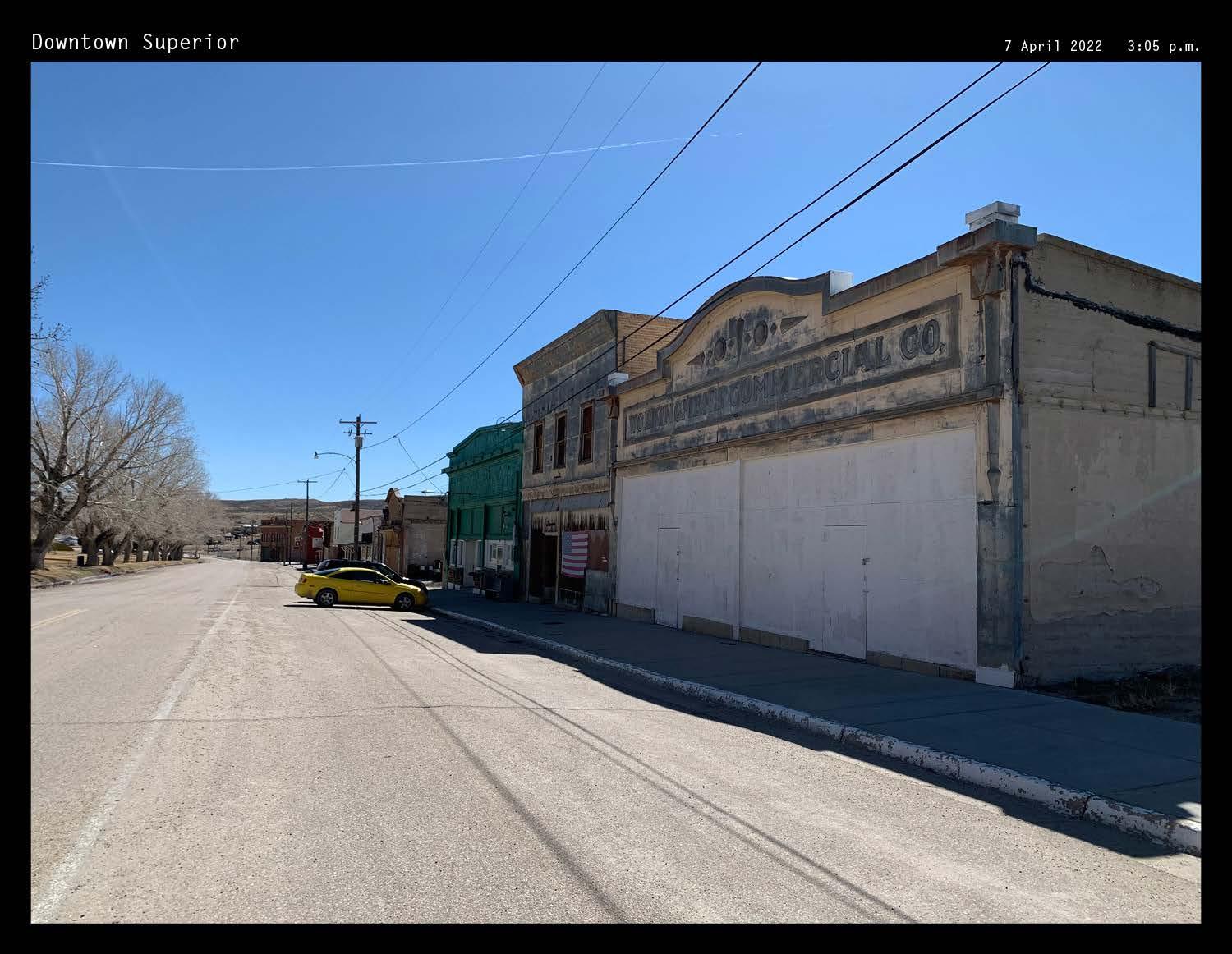

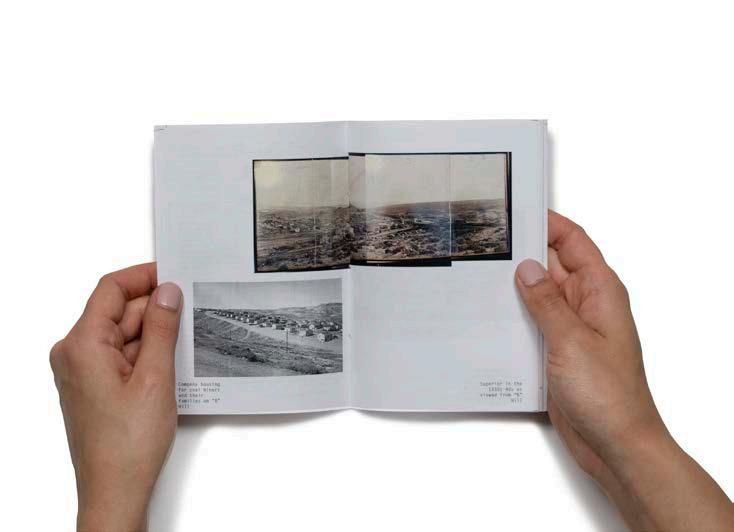

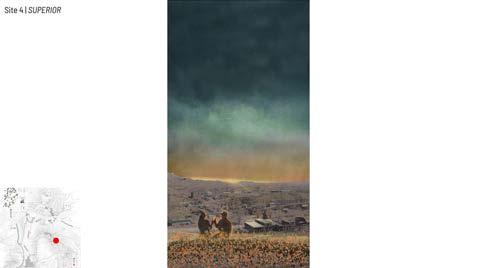

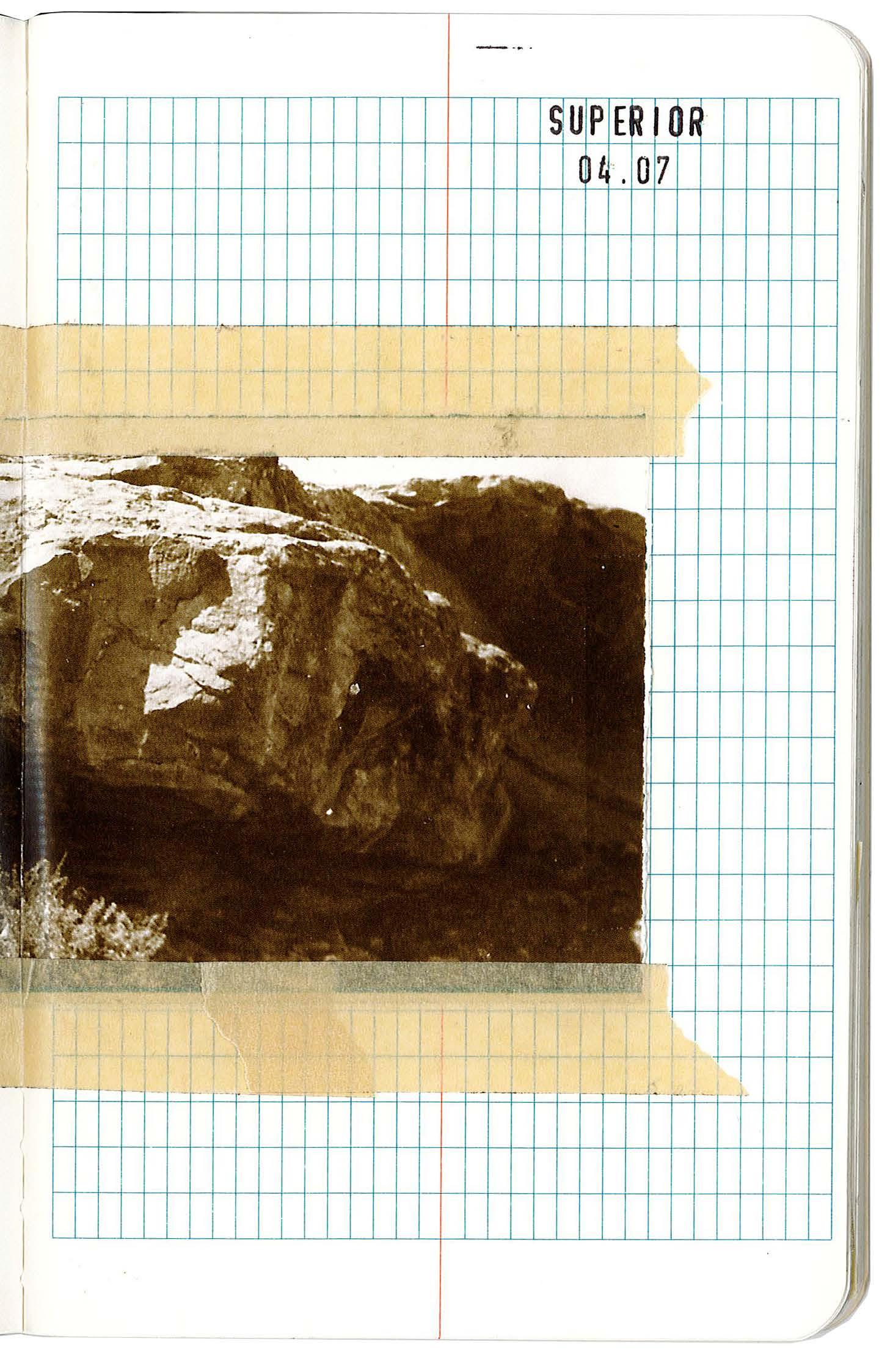

Superior in the 1930s-40s, photo from the Meek Family archives Superior in 2022, photo by author

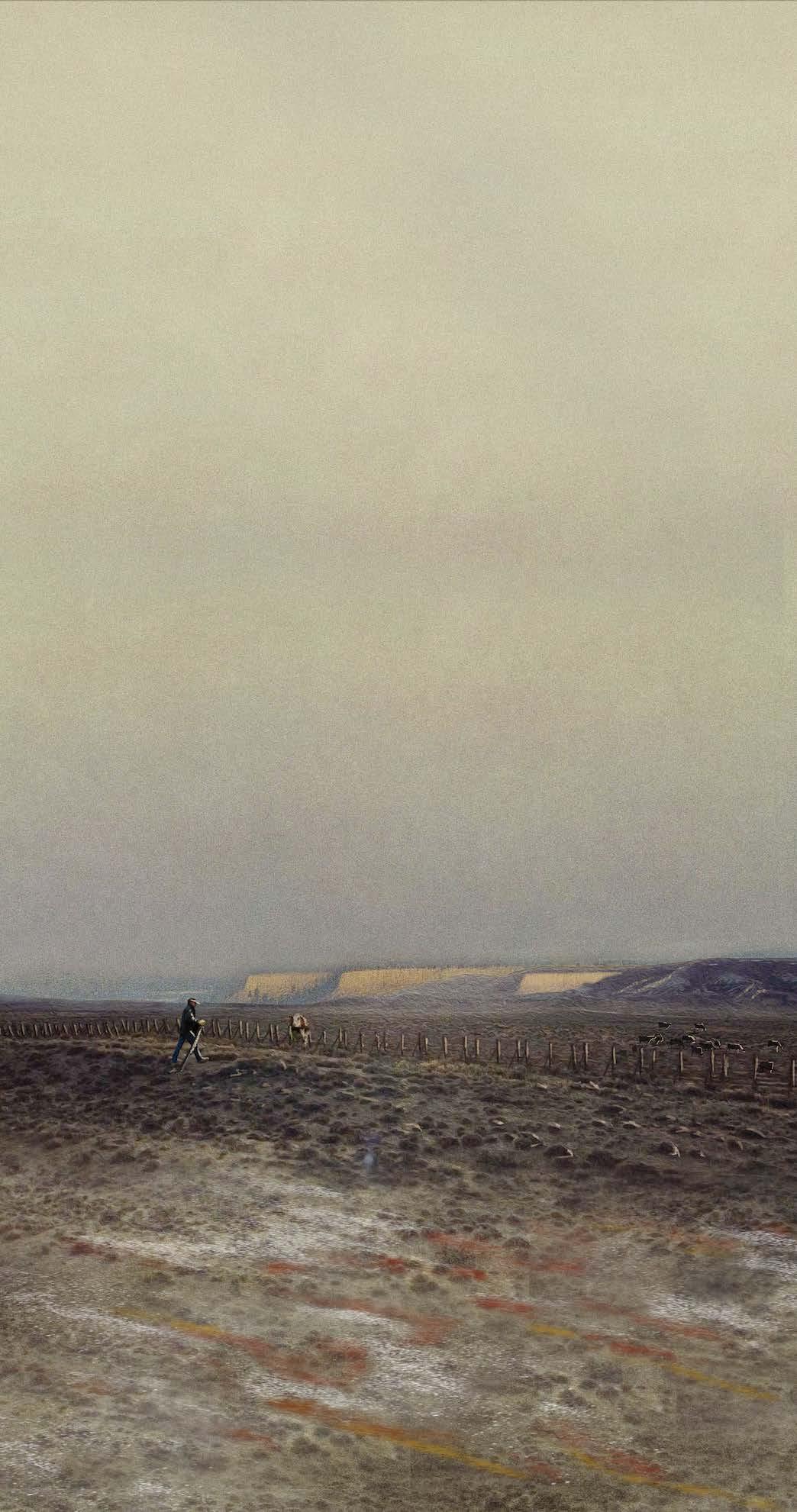

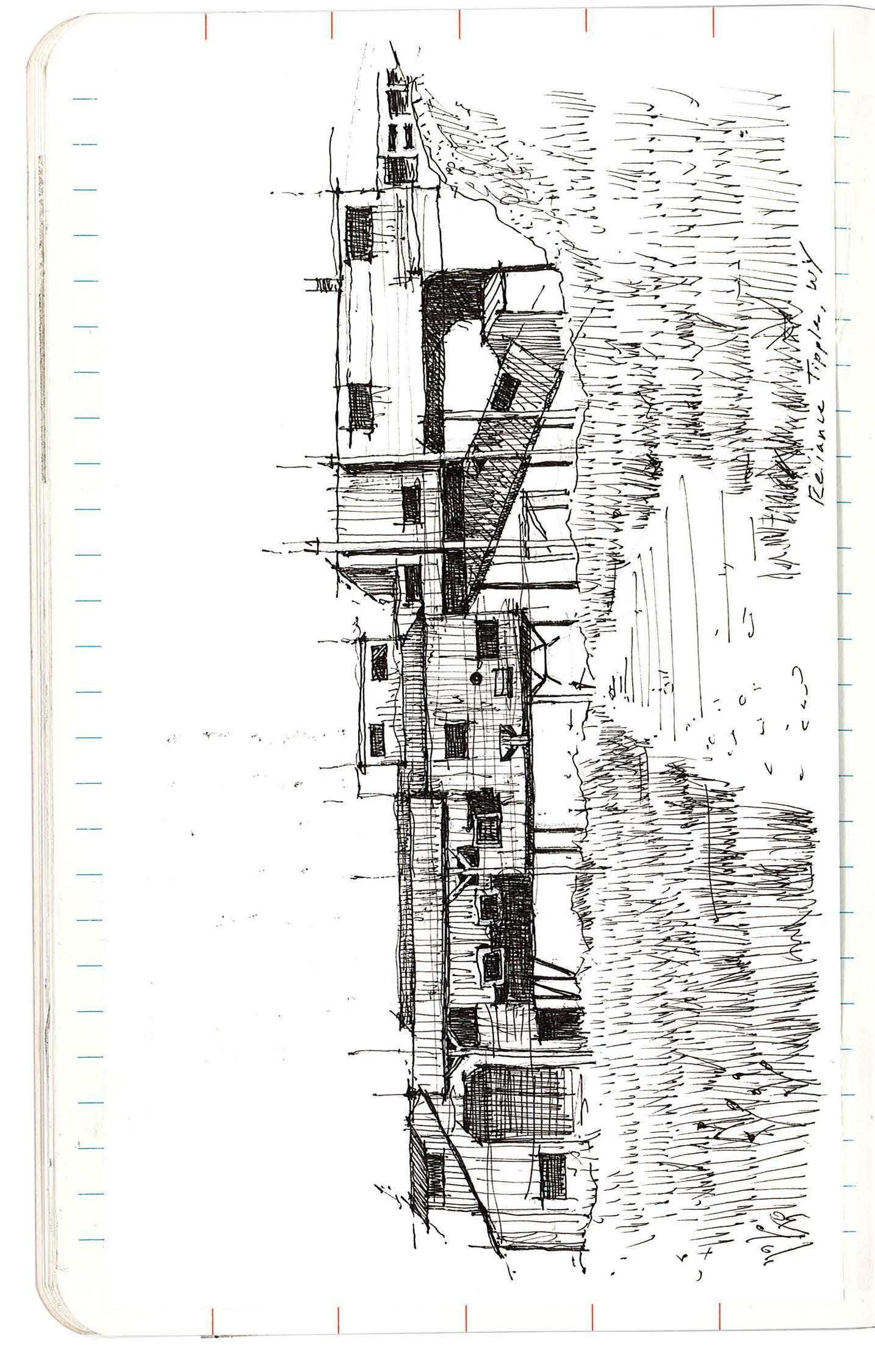

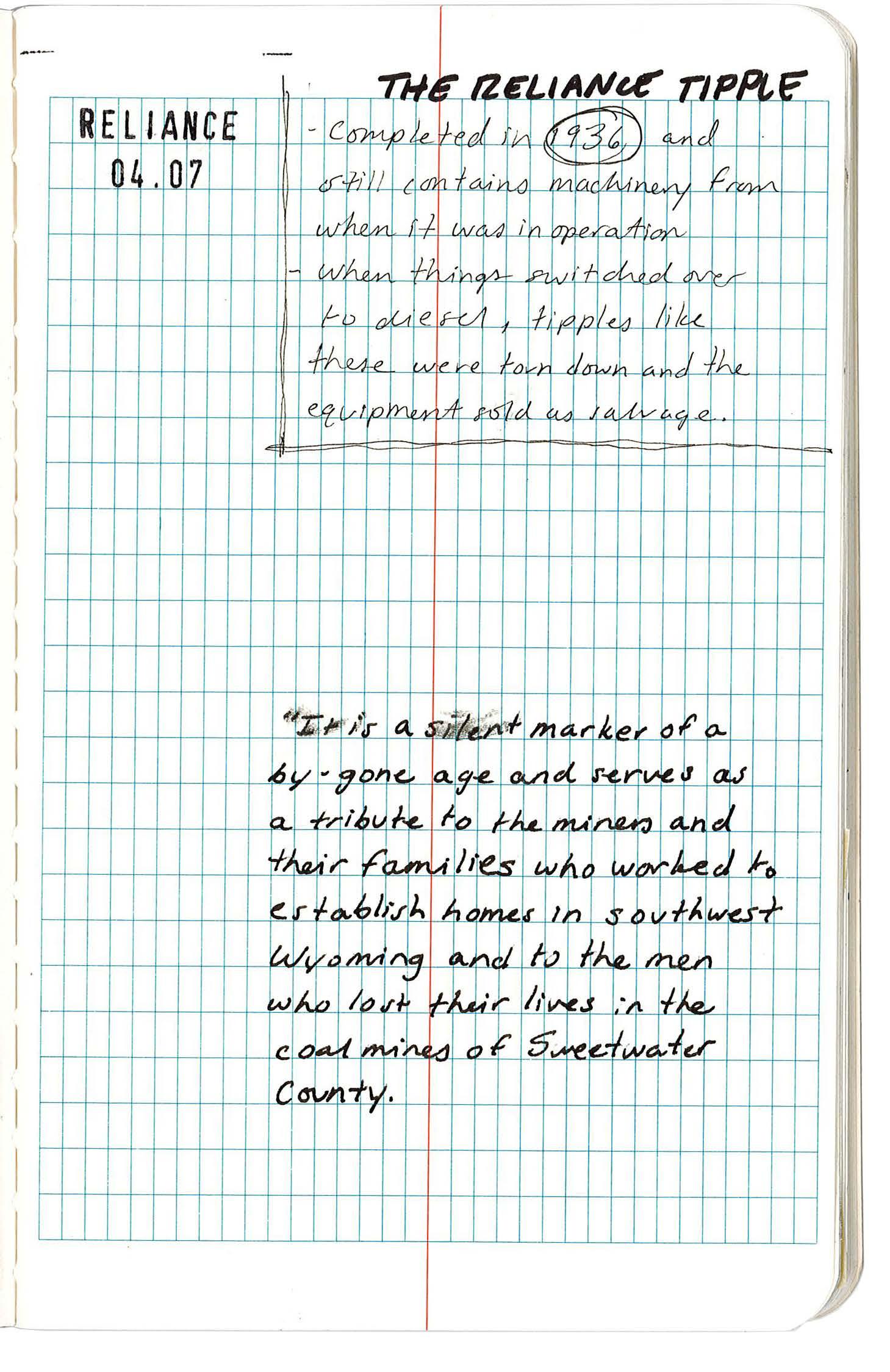

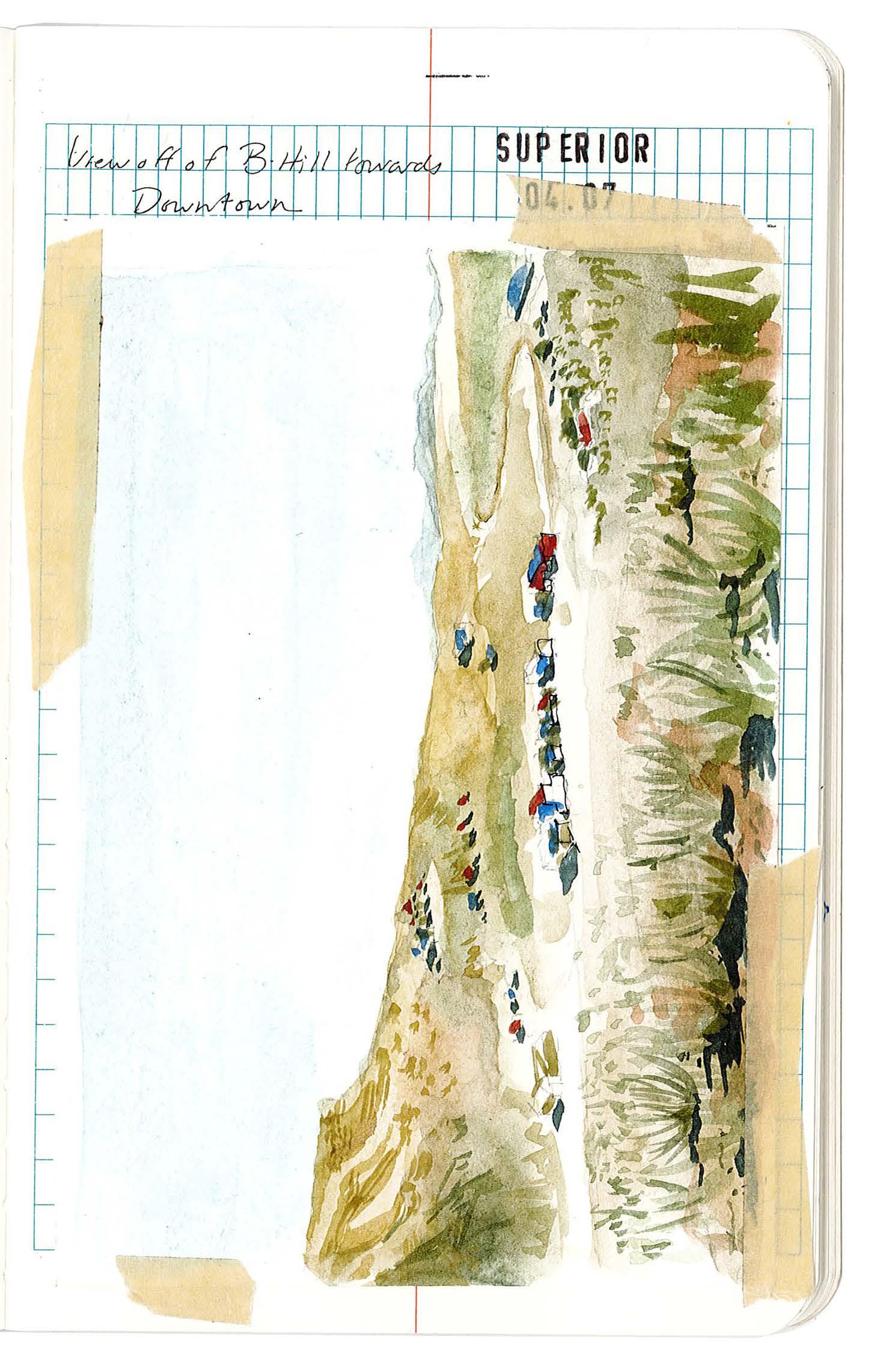

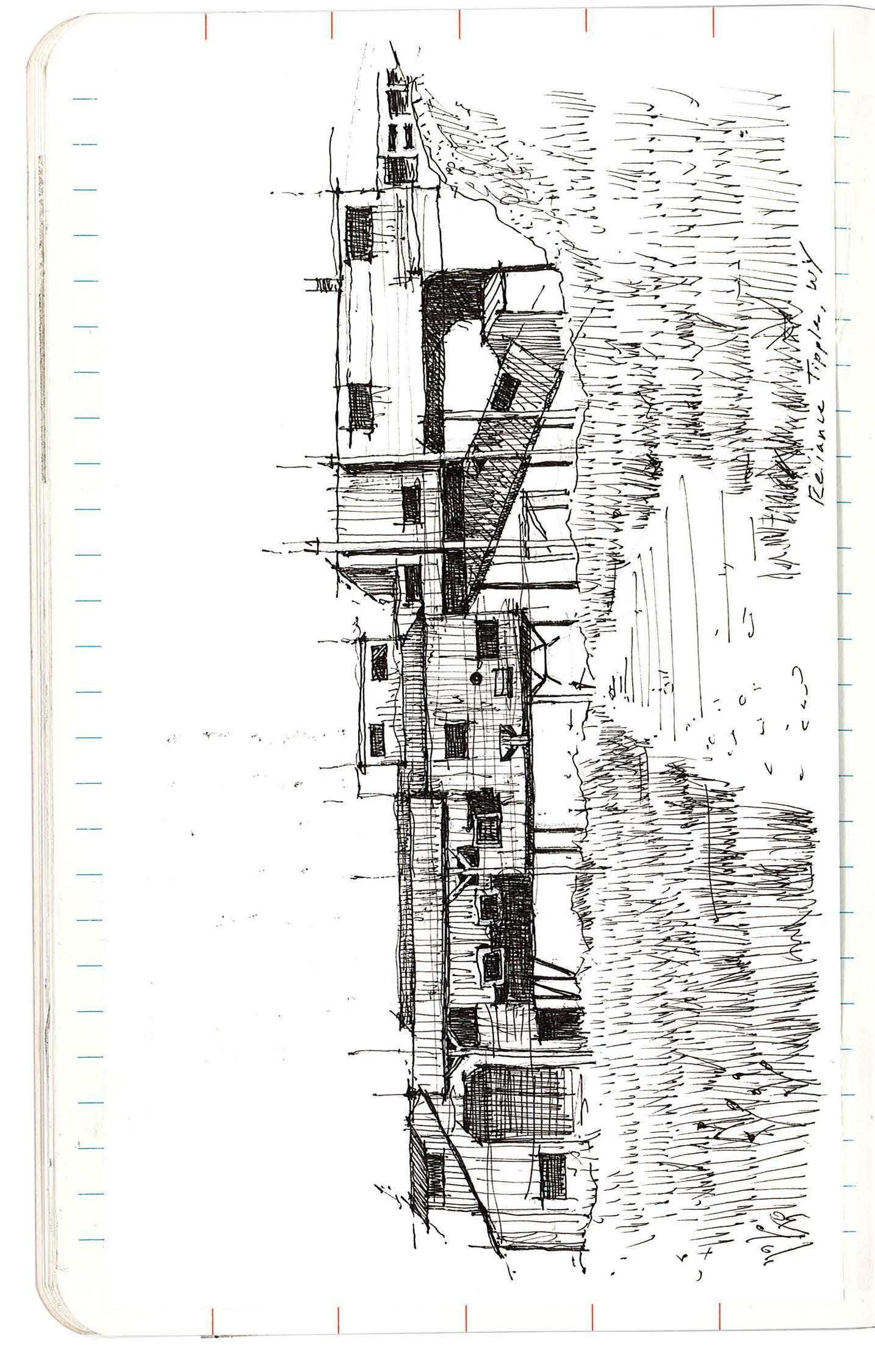

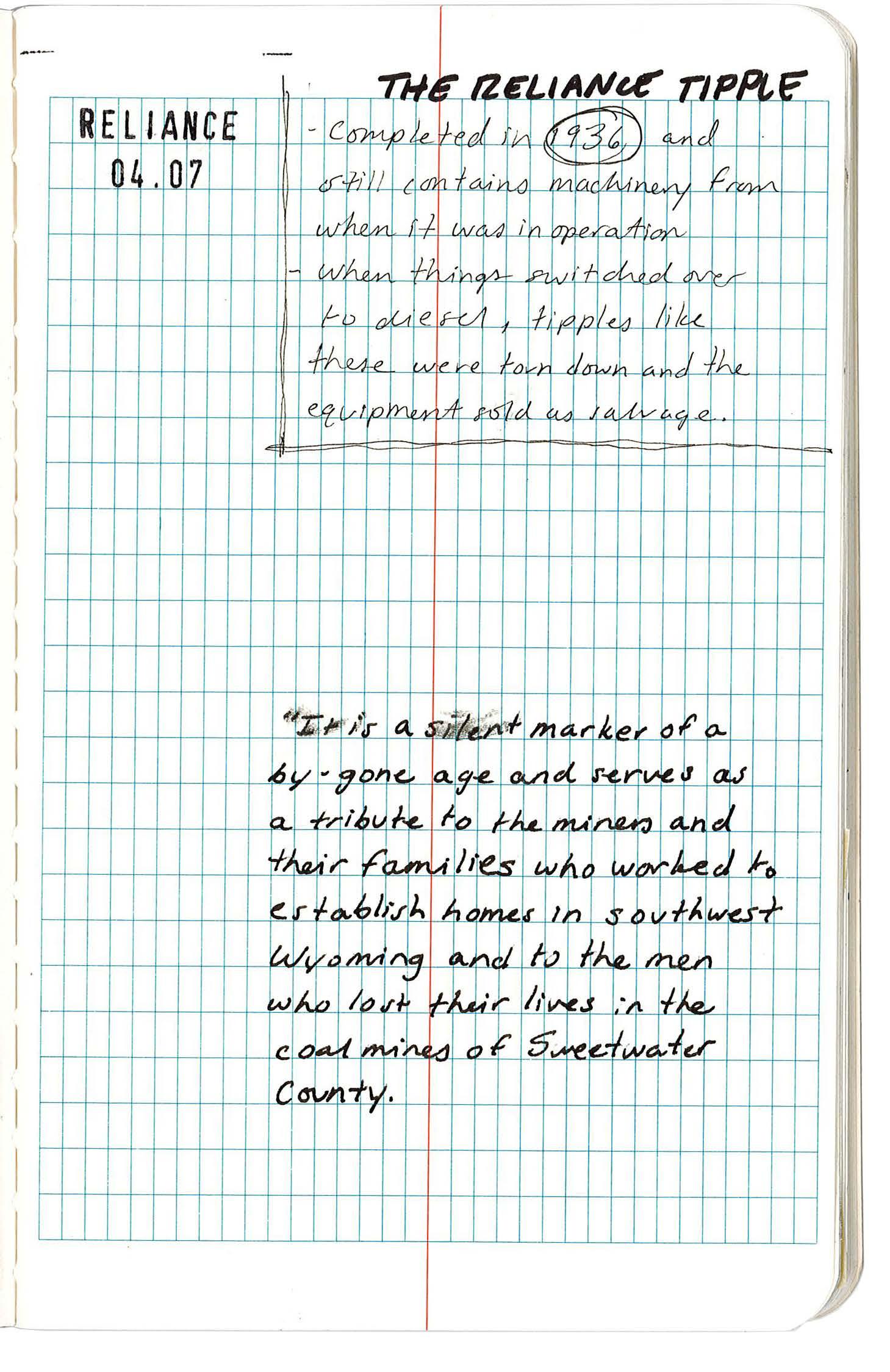

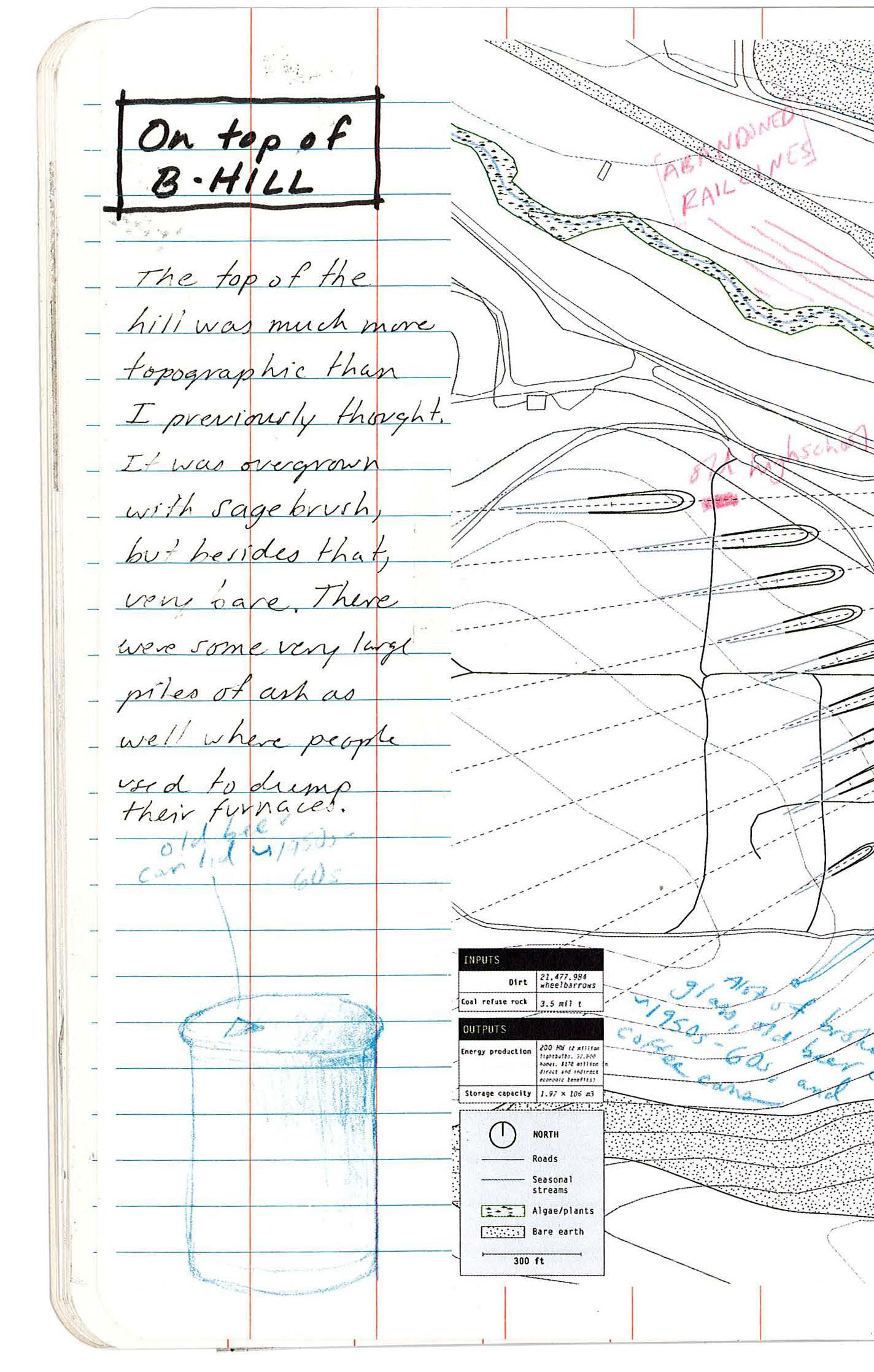

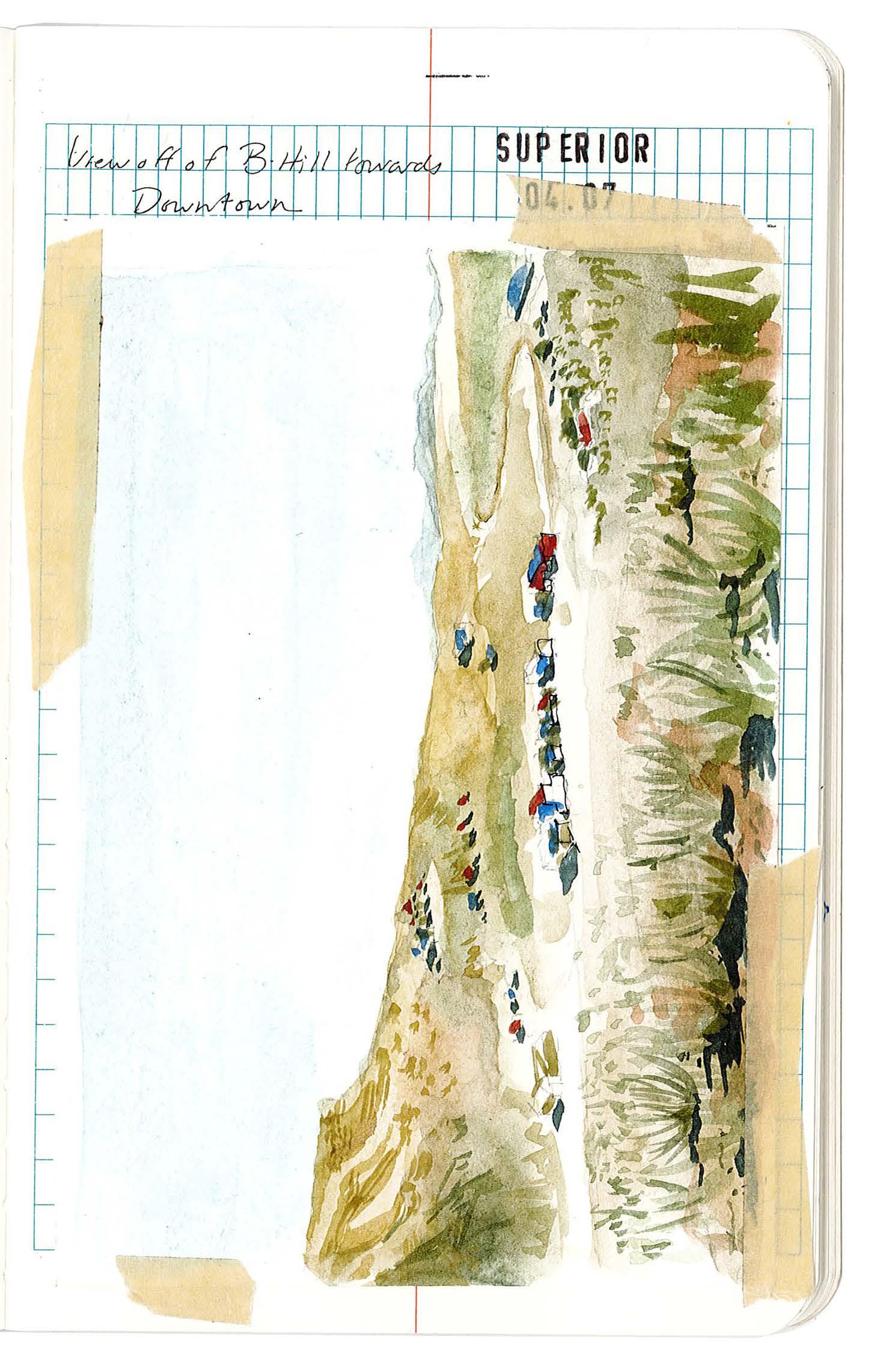

View from “B” Hill towards downtown Superior 7 April 2022 2:24 p.m.

ORIGINS OF SUPERIOR

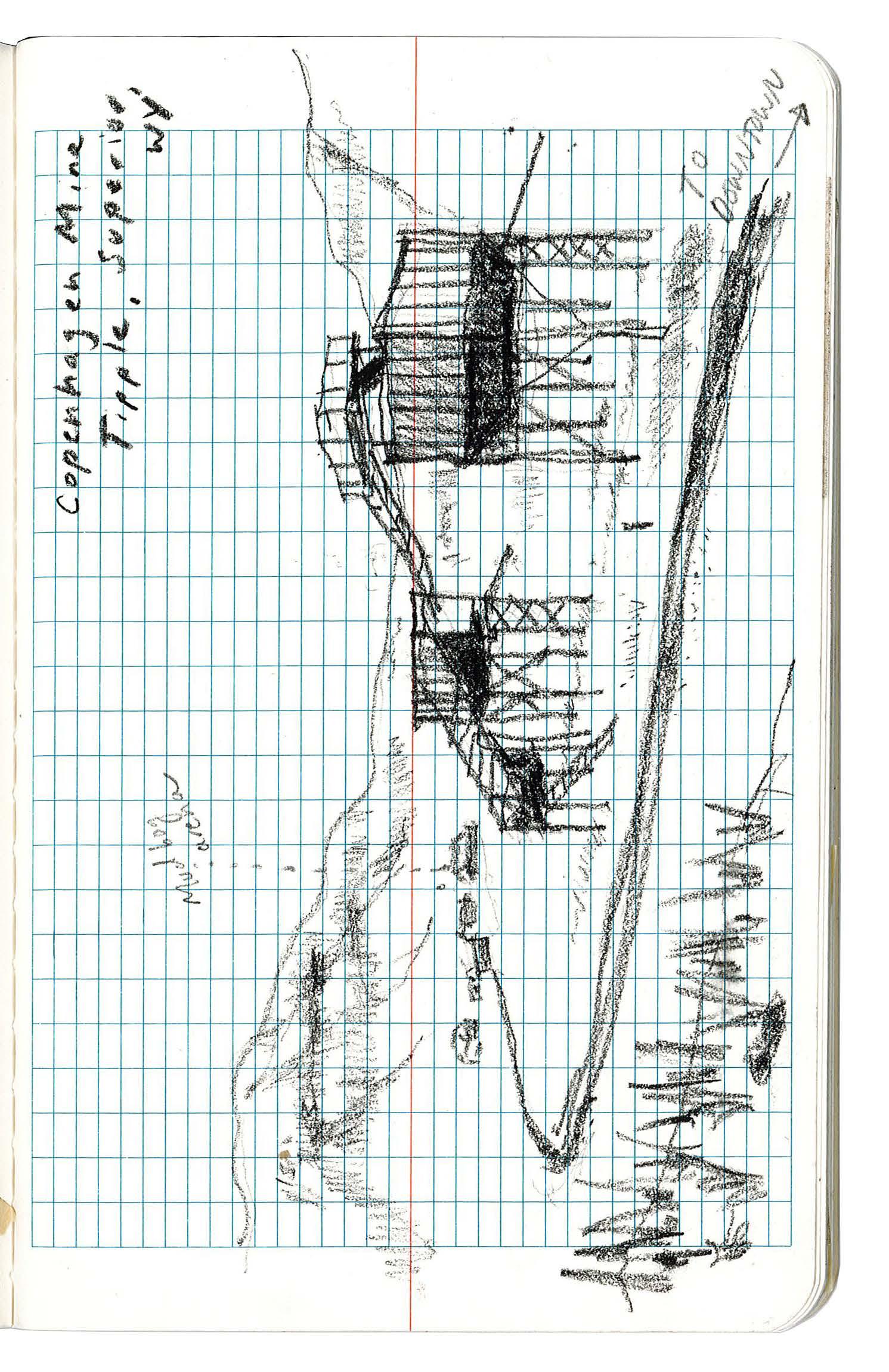

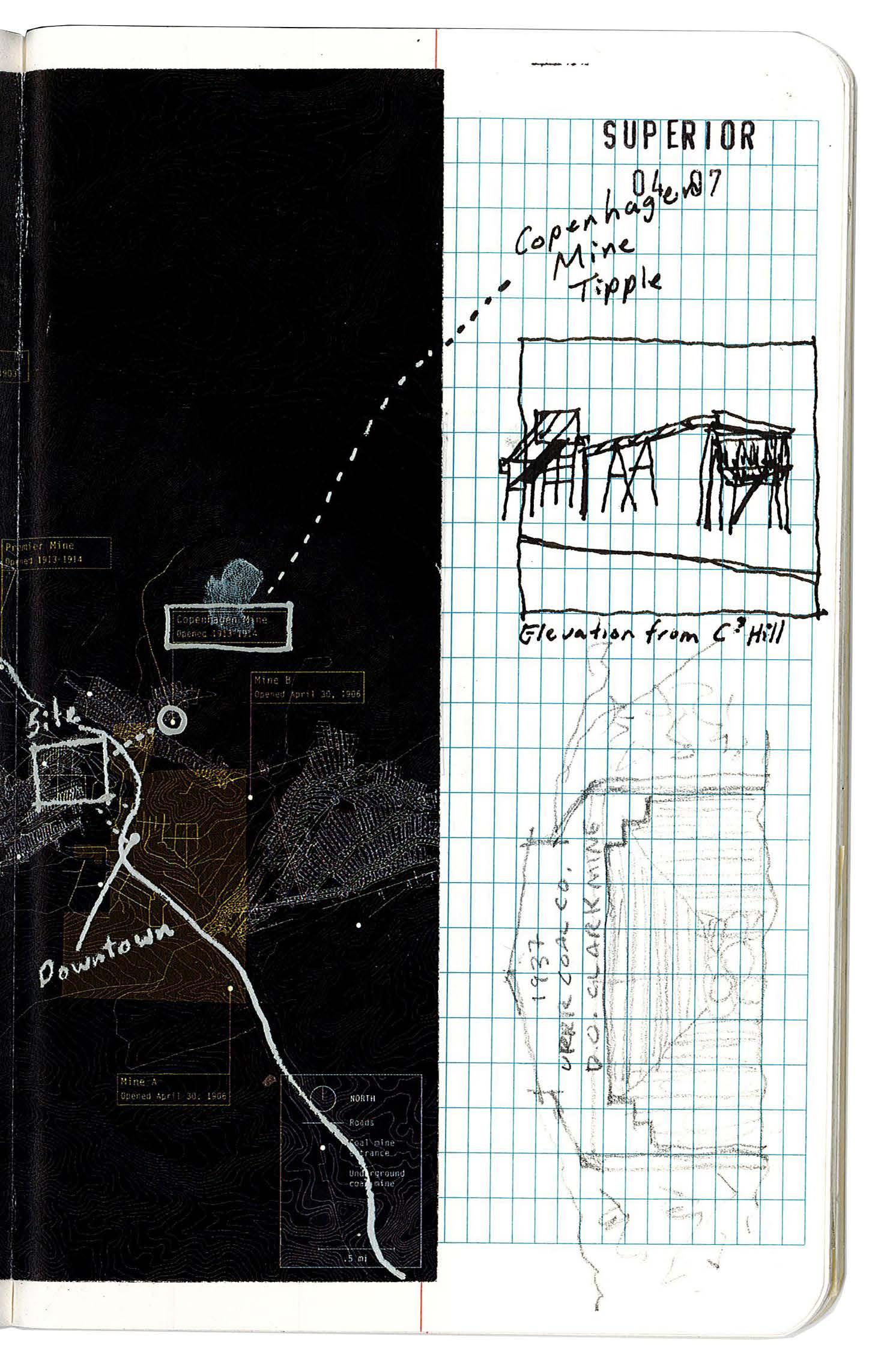

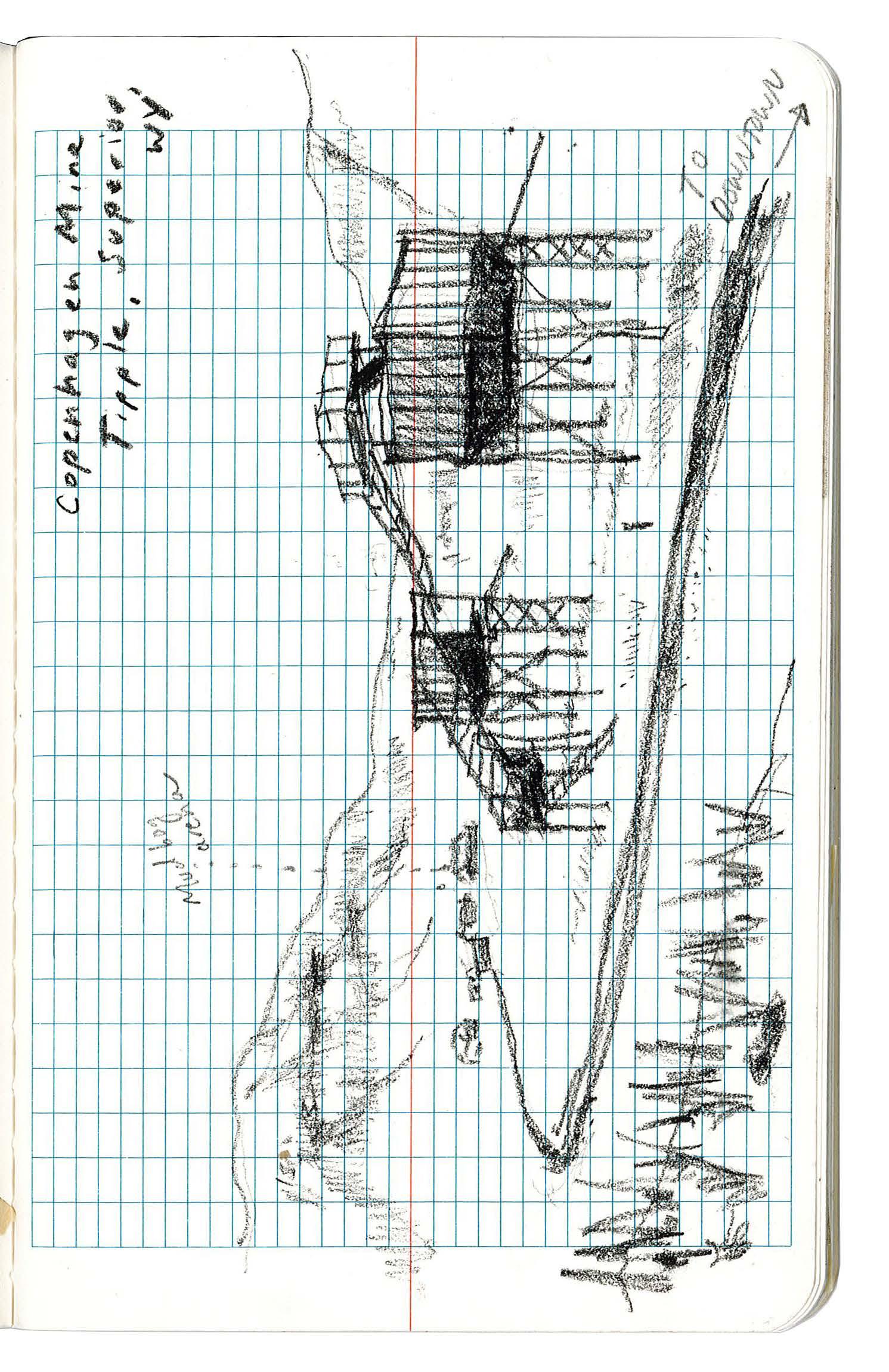

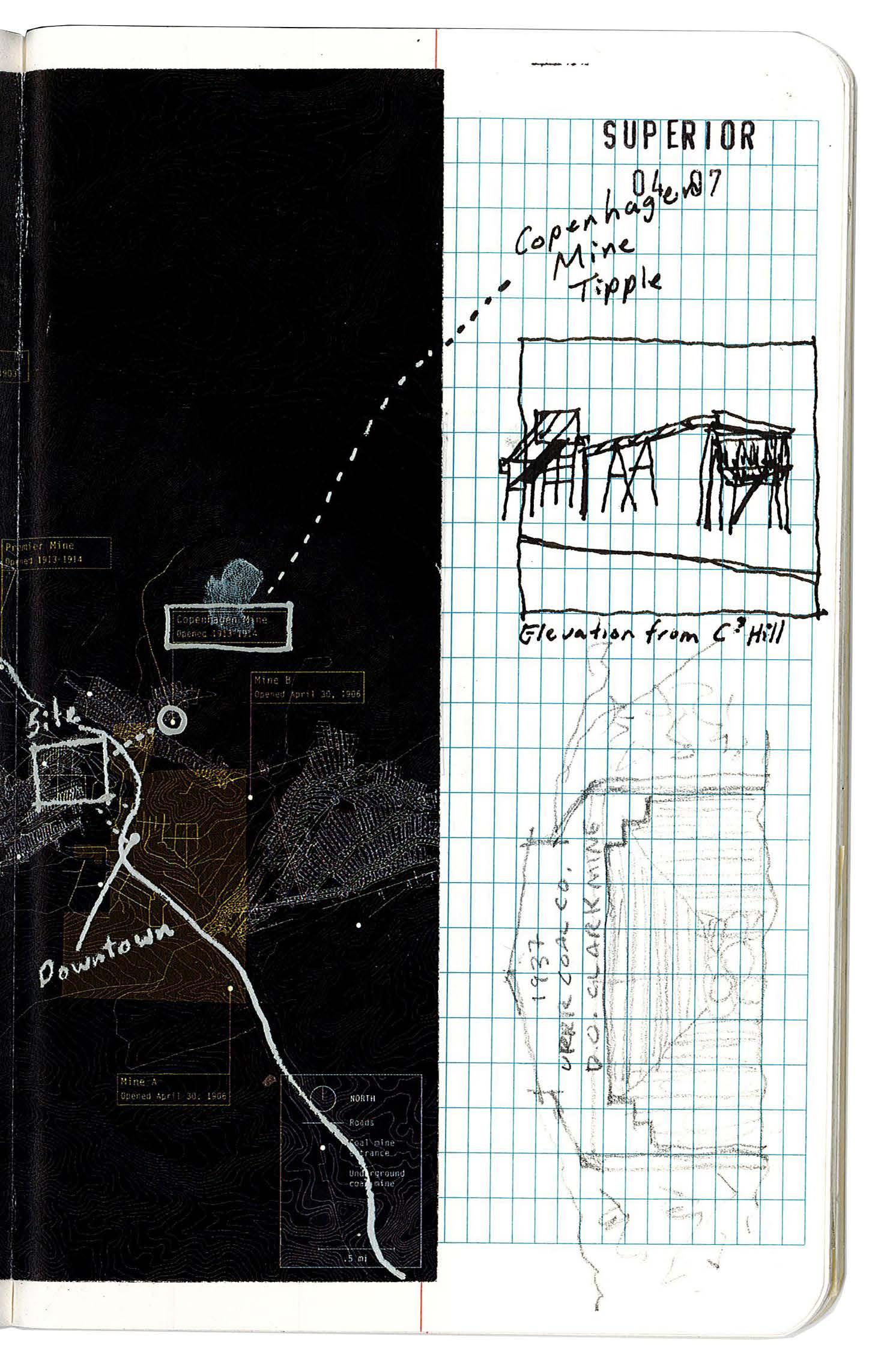

Located down the aptly named Horse Thief Canyon, an early day rendezvous point for stock-stealing outlaws, Superior proudly asserts its history as a coal boomtown. Coal was first located in Superior in 1900 when a prospecting team led by Morgan Griffiths entered the Canyon and established the site for the first of Superior’s many coal mines. The Superior mines produced nearly 24,000,000 tons of coal annually in their prime, second only to Rock Springs. There were eight mines in the area, all but two owned and operated by the Union Pacific Coal Company to supply their locomotives. The Premier and Copenhagen Mines were independent.

47 V Superior and Rock Springs Historical Archive

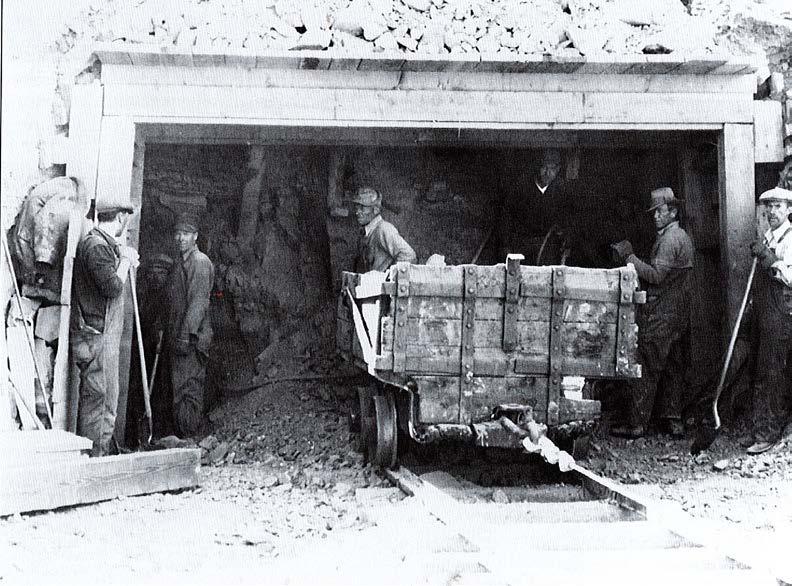

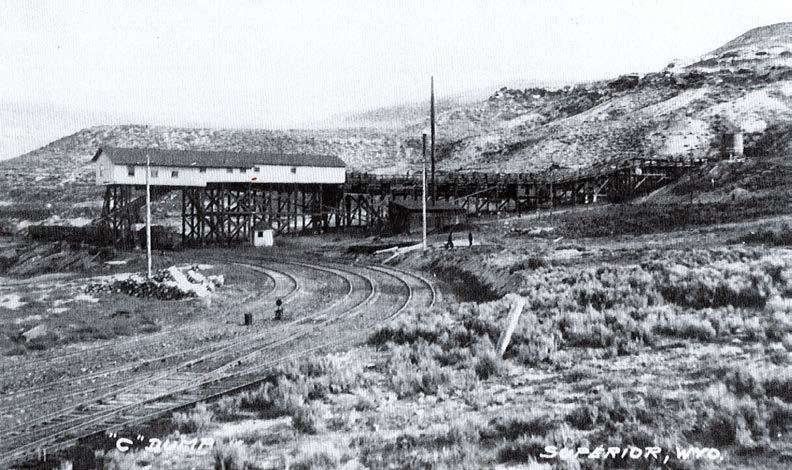

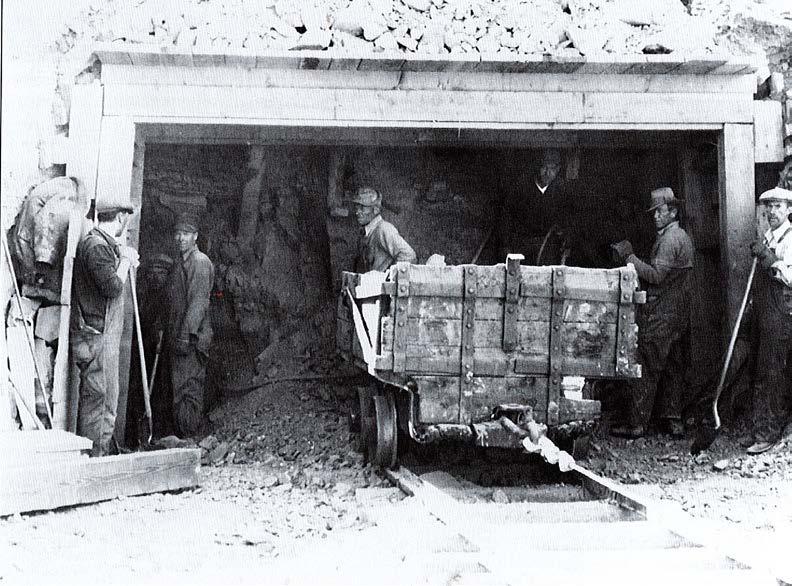

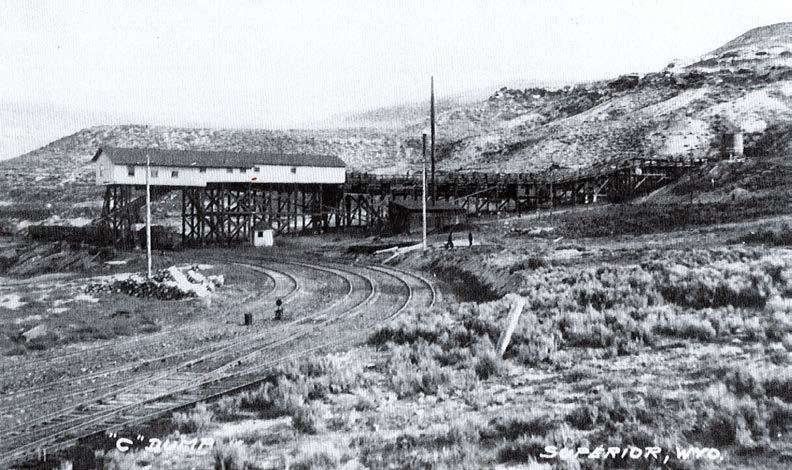

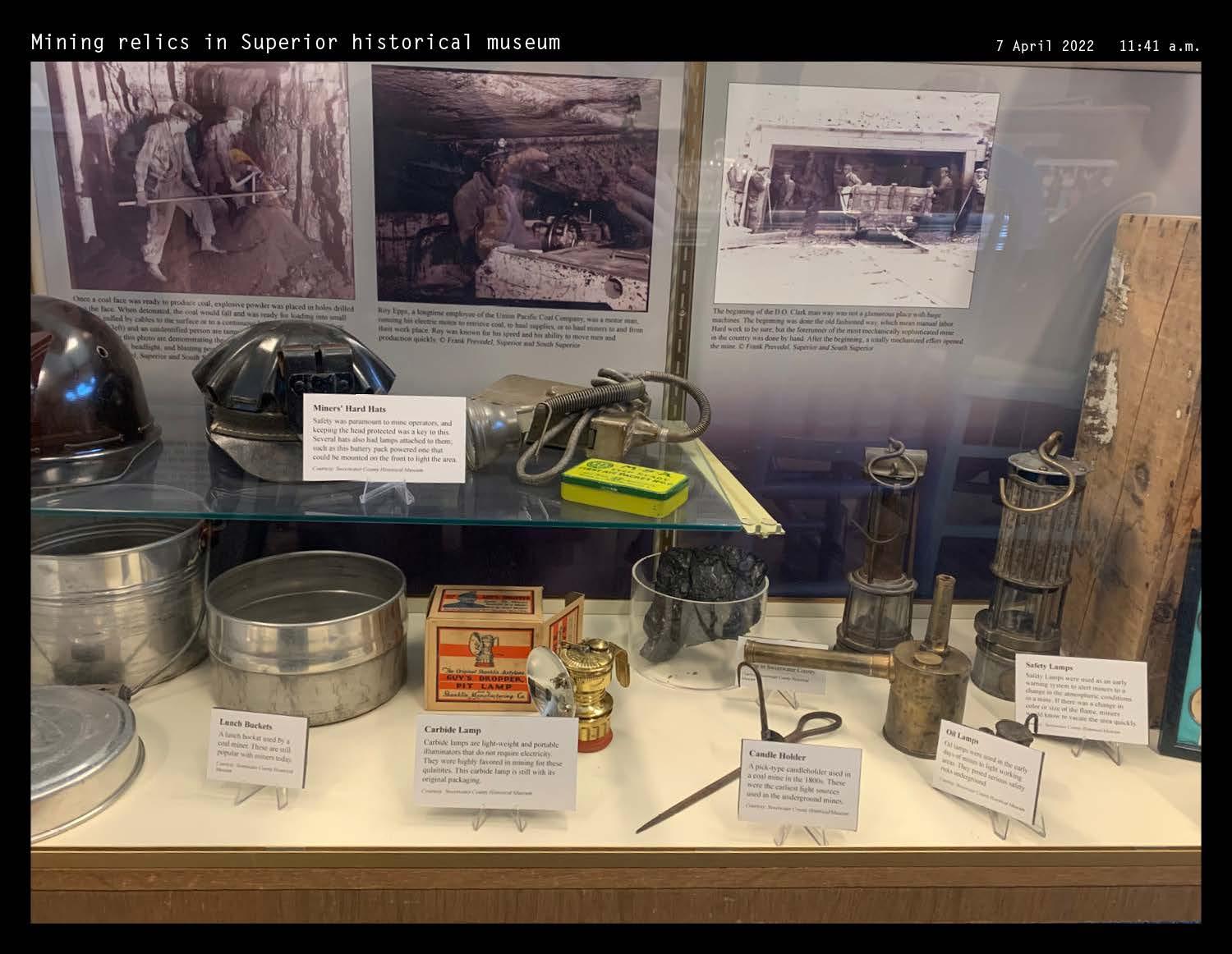

“C” Mine in the early 1900s, photo from Superior Historical Museum

Miners in D.O. Clark Mine, where my Grandfather worked, photo from Frank Prevedel and the Sweetwater County Historical Museum

48

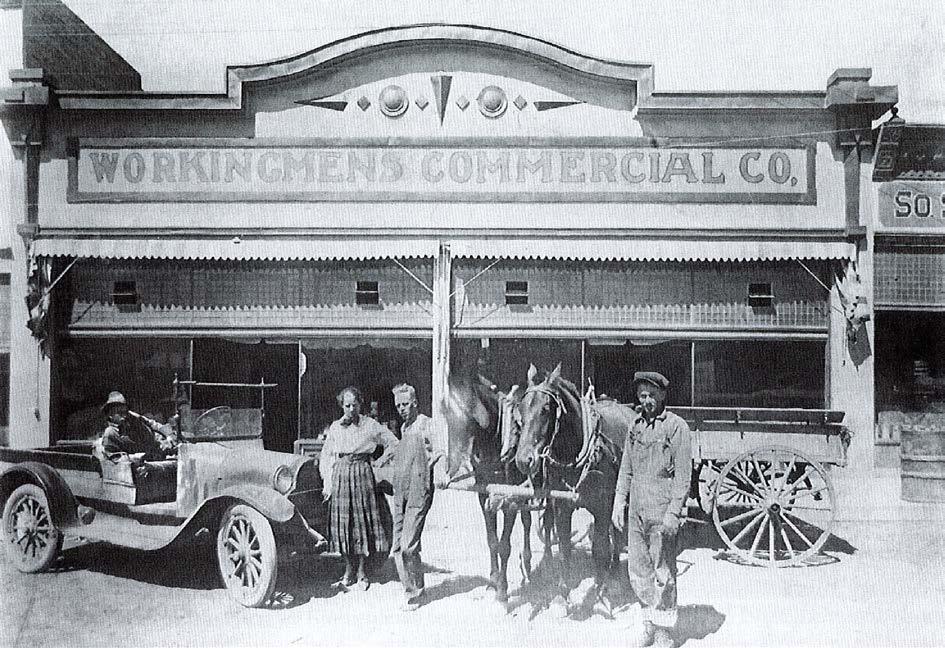

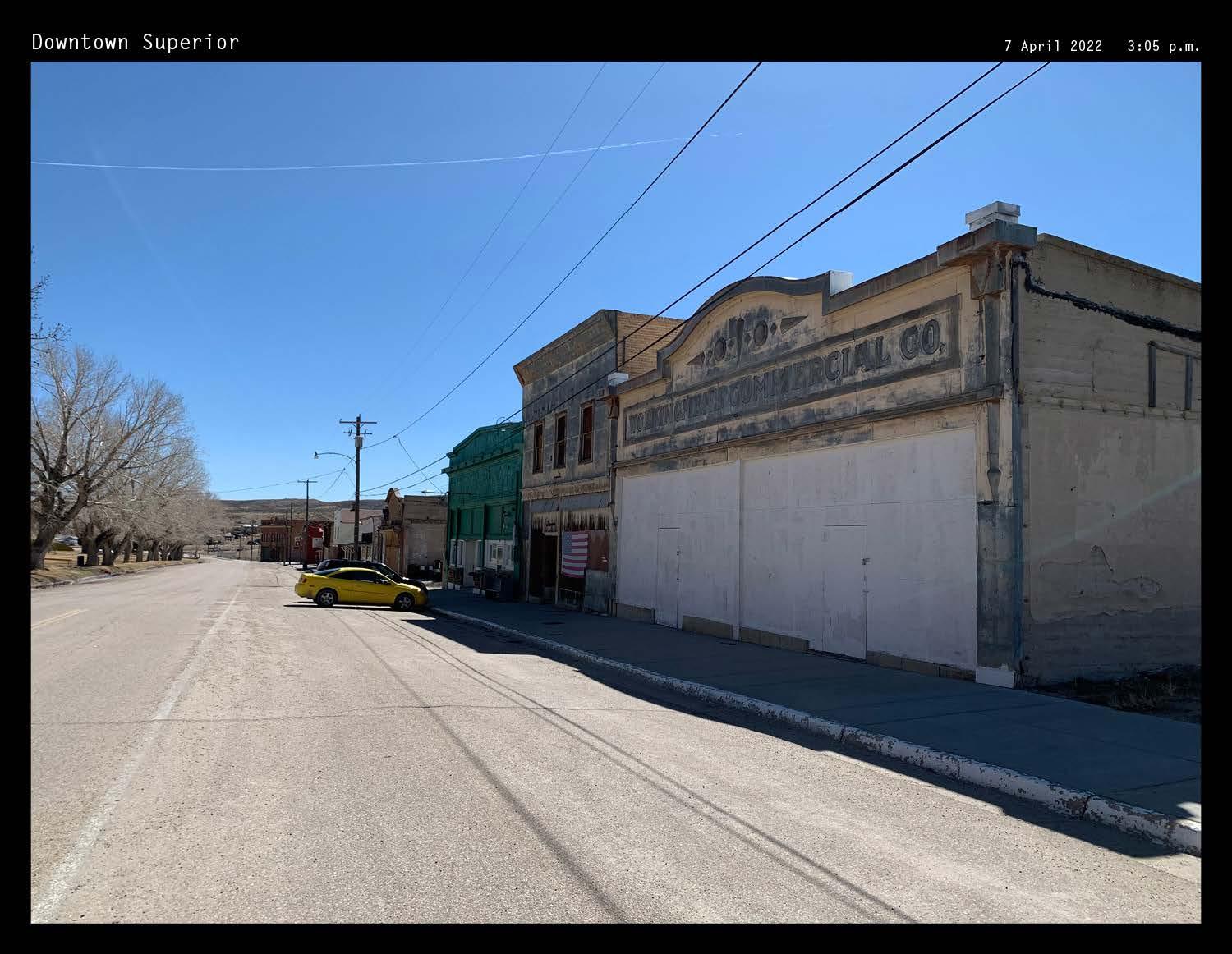

Workingmens Commercial Co. in 2022, photo by author

Historical information from: (Prevedel 2011)

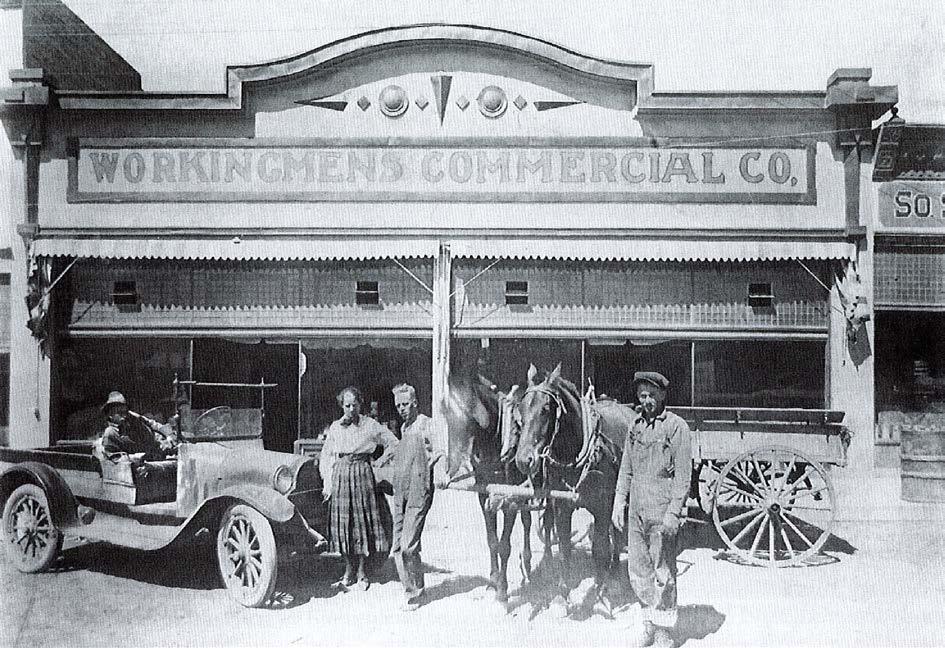

Workingmens Commercial Co. from the 1920s-30s, photo from Frank Prevedel and the Sweetwater County Historical Museum

SENSE OF COMMUNITY AND LIVELIHOOD CENTERED AROUND THE EXTRACTION INDUSTRY

Background research provoked the question: what is a town’s role in energy transitions, and what effects do these larger-scale actors have on the people whose livelihoods and sense of community depend on the extraction industry?

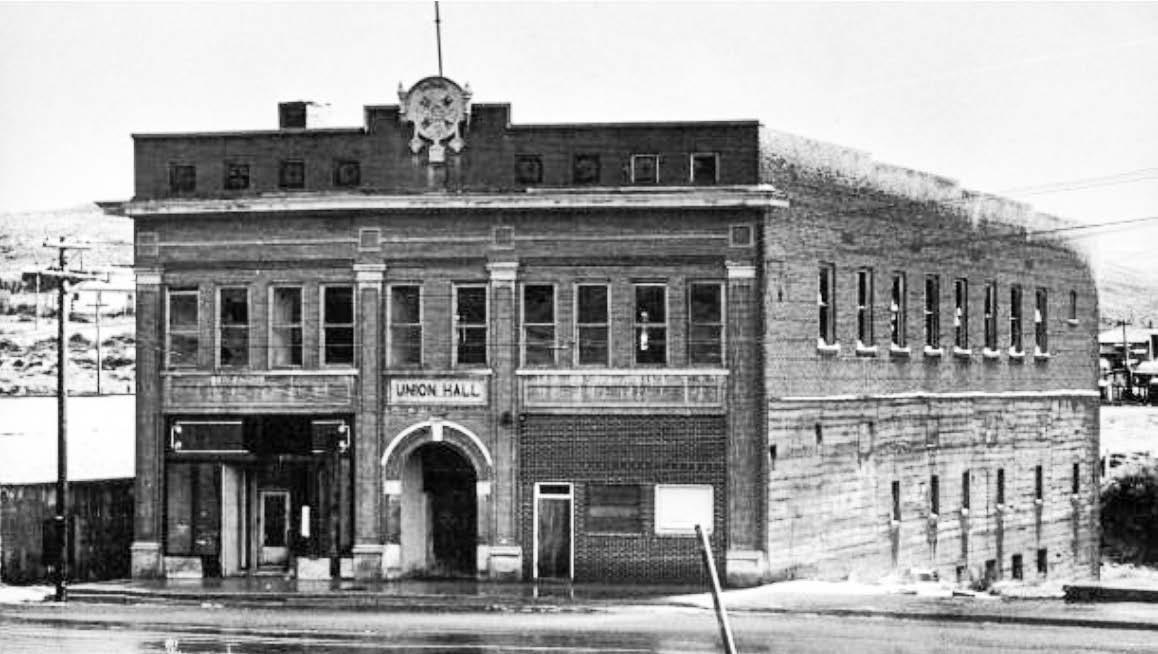

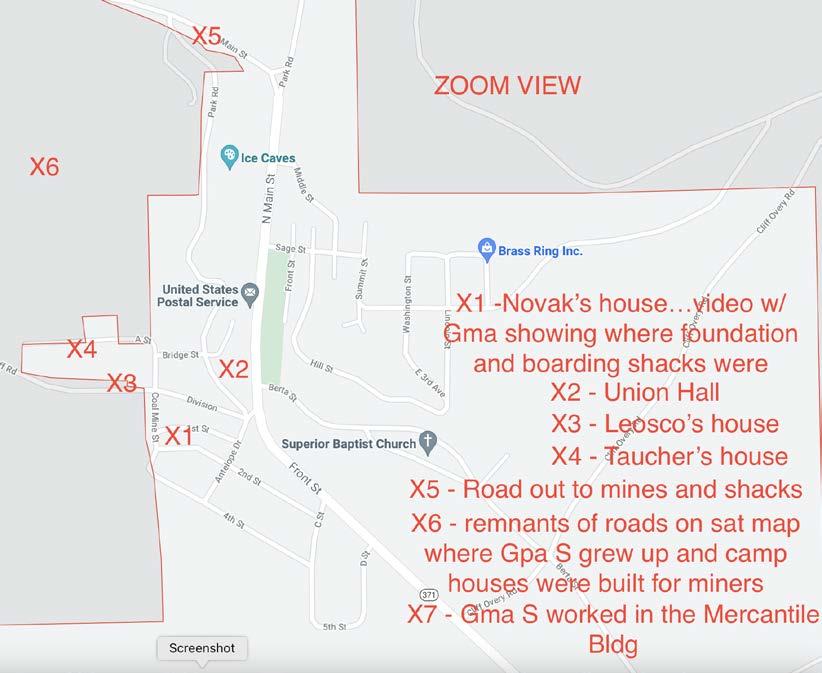

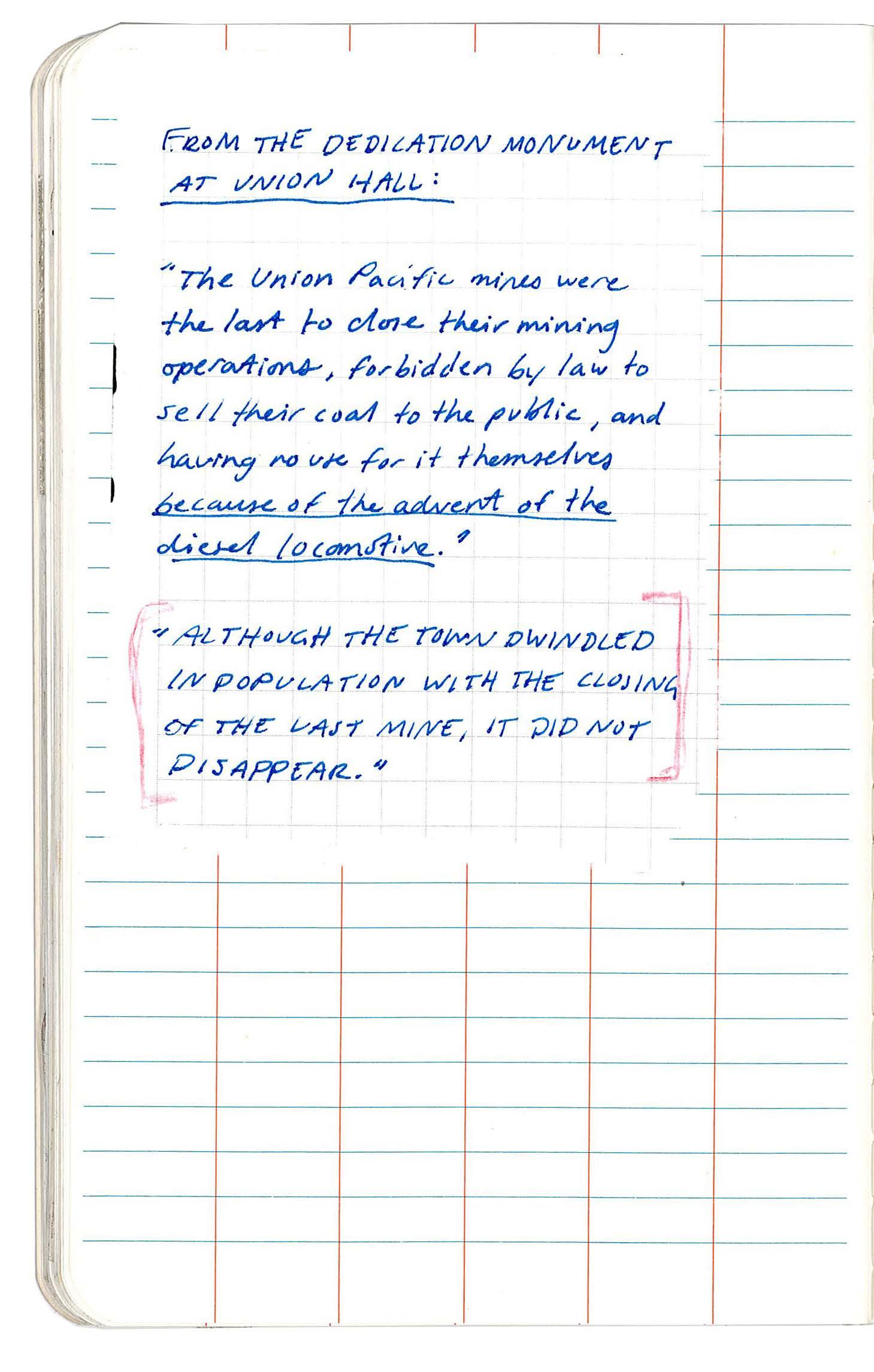

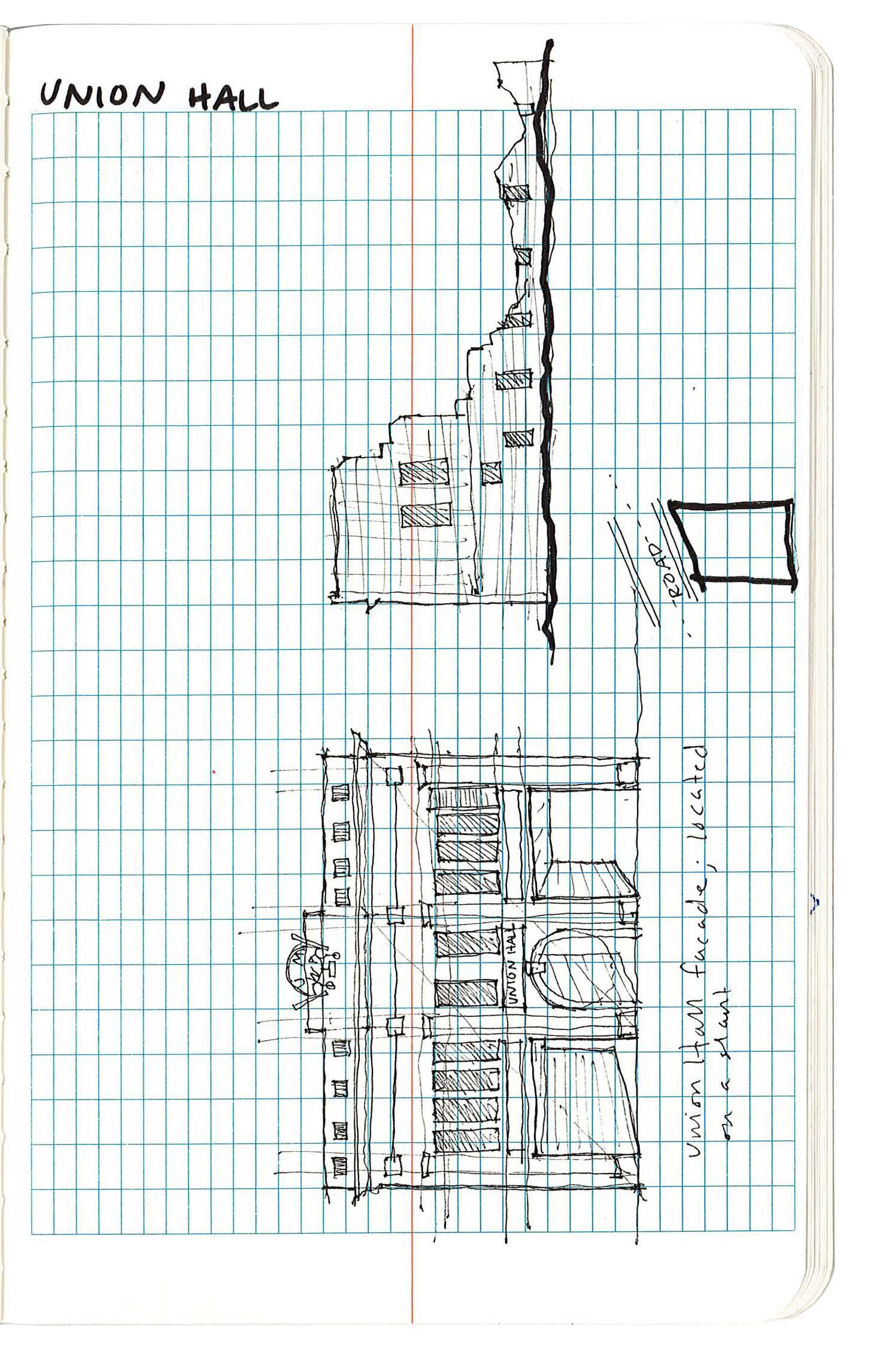

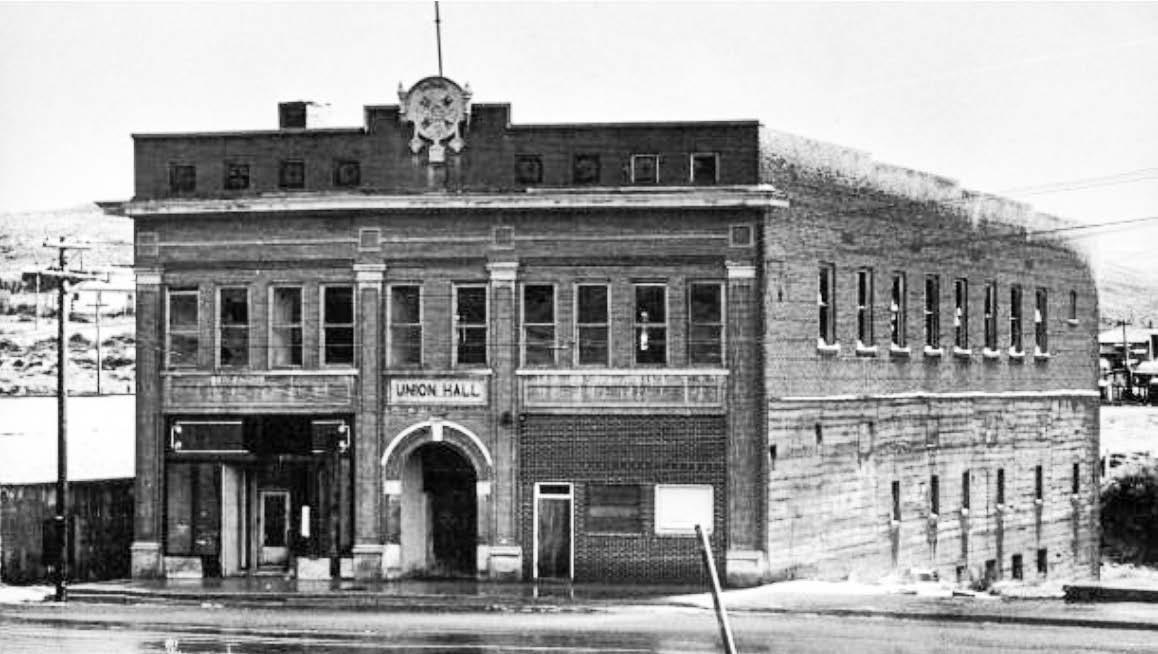

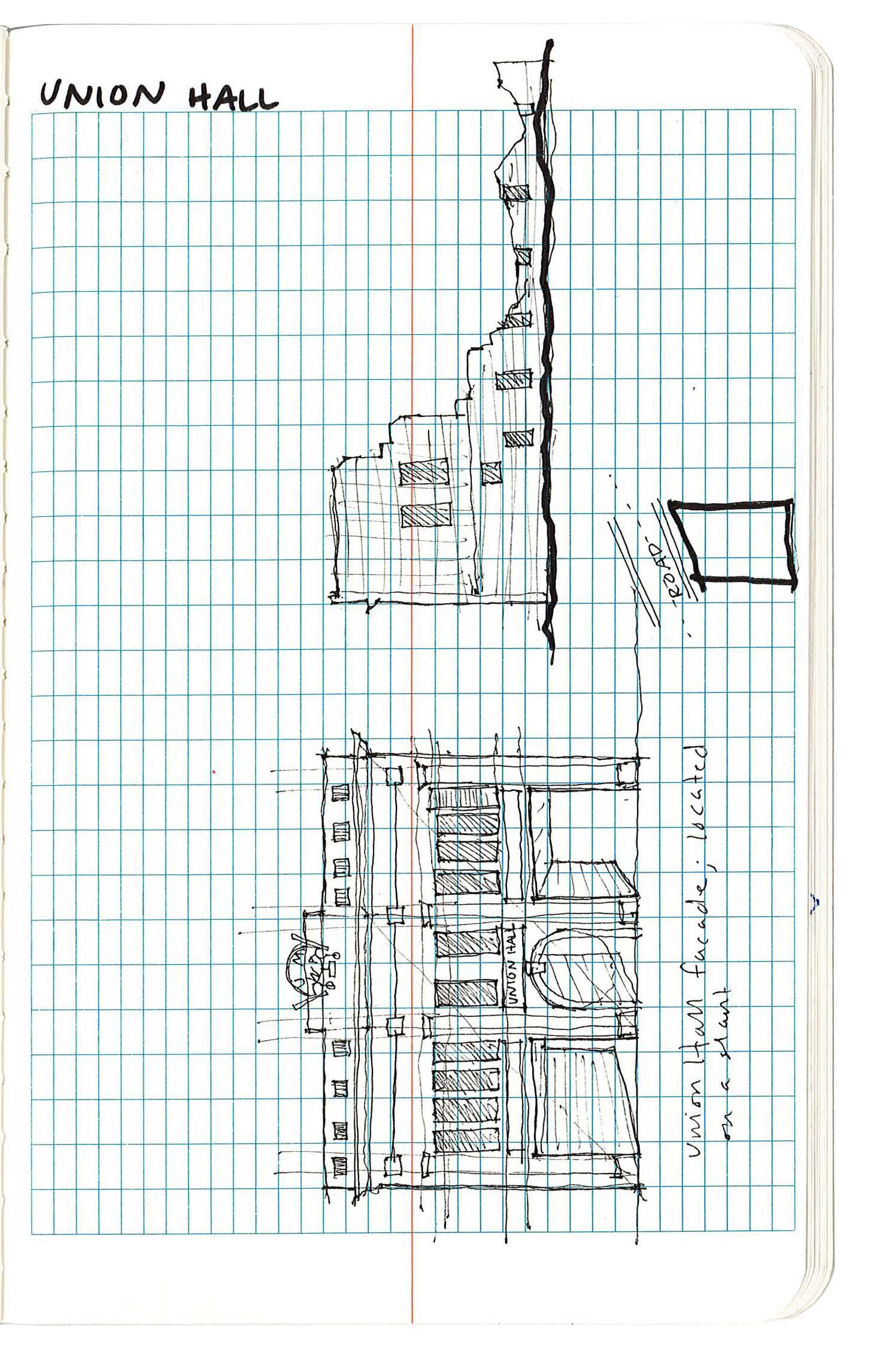

Union Hall in Superior, for example, was funded and operated by the United Mine Workers. Accommodating union and community activities, the hall at one time hosted a bowling alley, a grocery store, and doctor’s and dentist’s offices. My grandparents attended dances on the upper floor. Union Hall has since been restored and now stands as a park to inform visitors about the town’s history, and as a monument to workers in the Superior mines.

49 V Superior and Rock Springs Historical Archive

Union Hall in 2022, photo by author

Union Hall from the 1920s-30s, photo from Frank Prevedel and the Sweetwater County Historical Museum

50

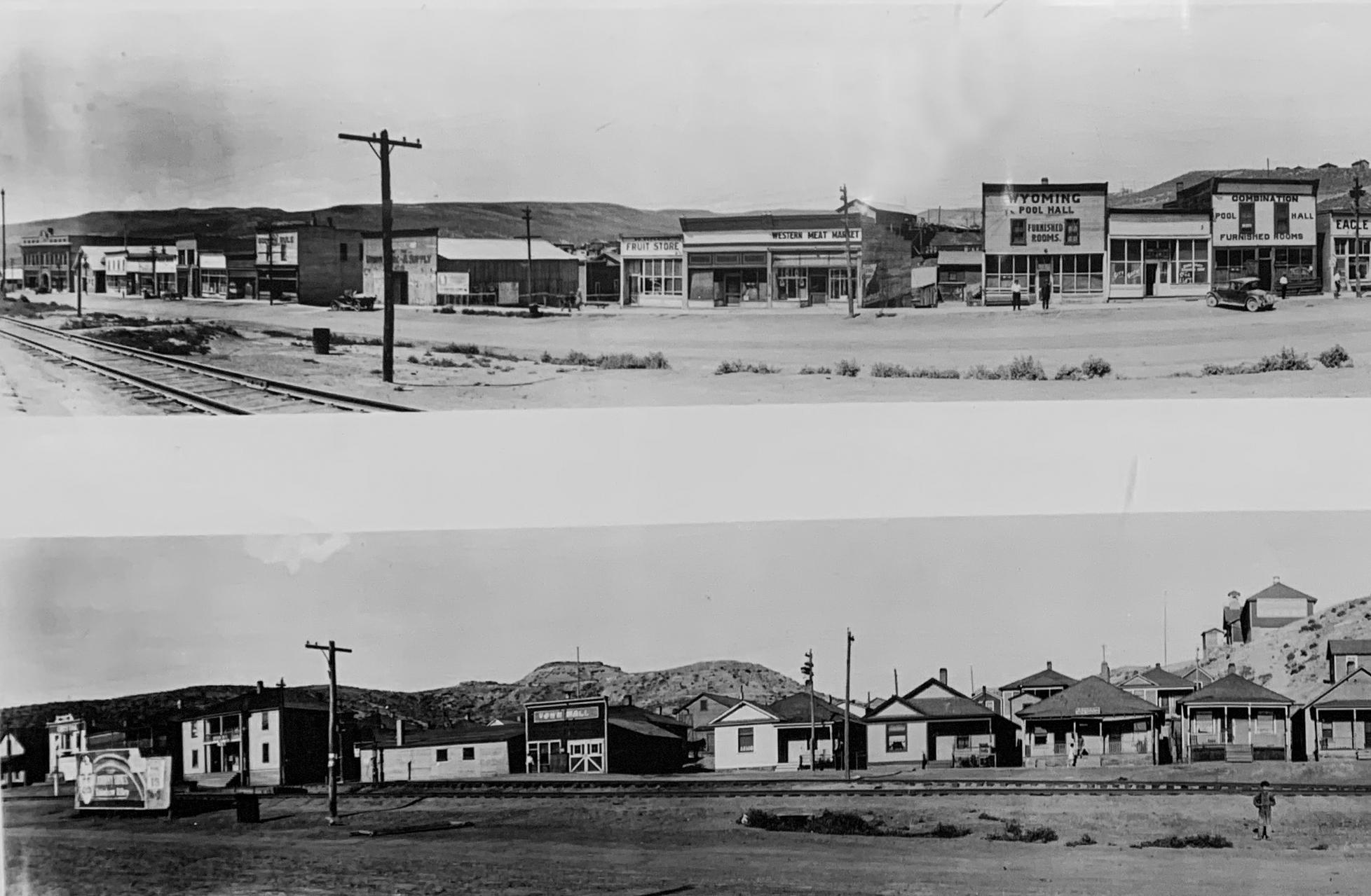

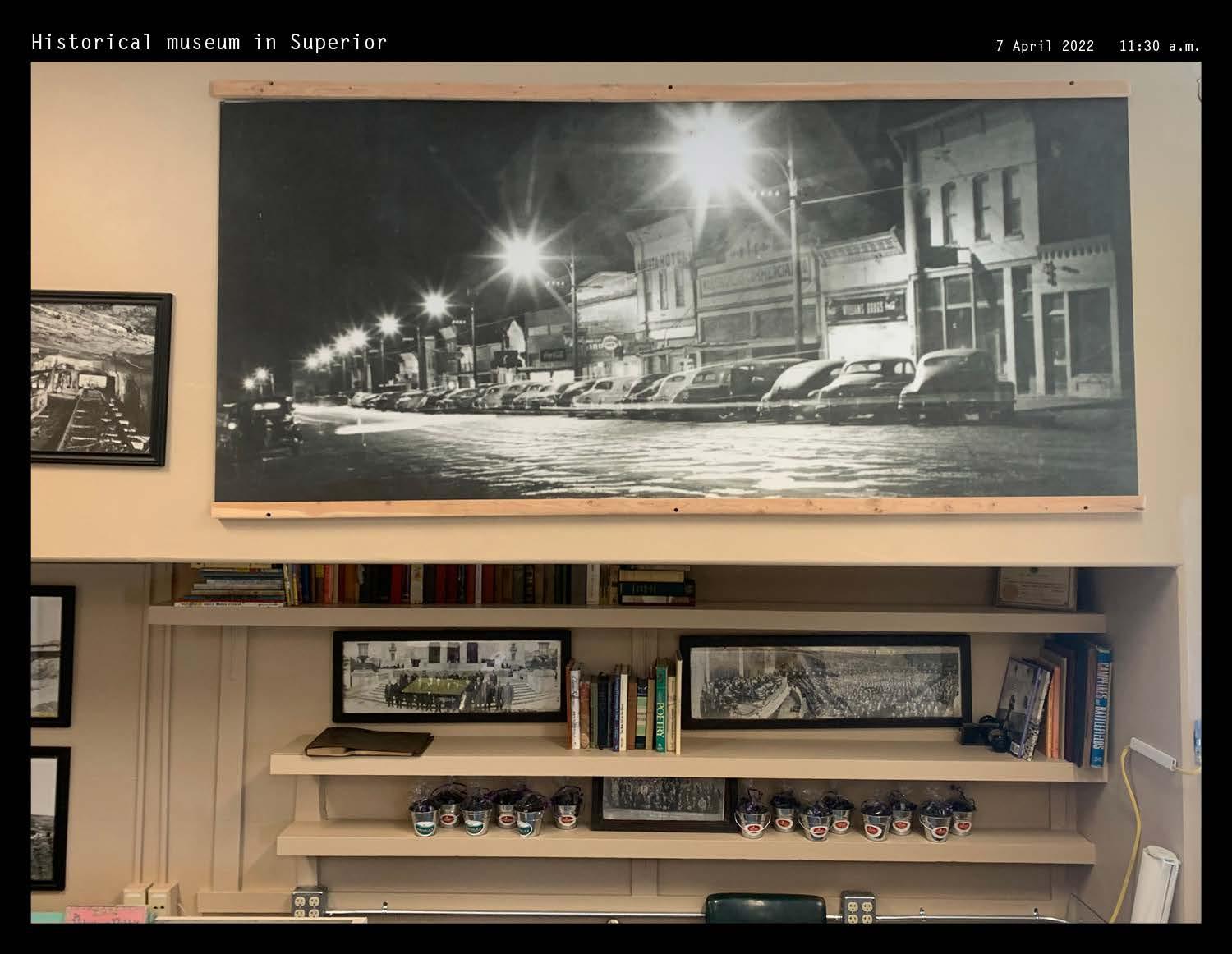

Downtown Superior, photo from the Superior Historical Museum

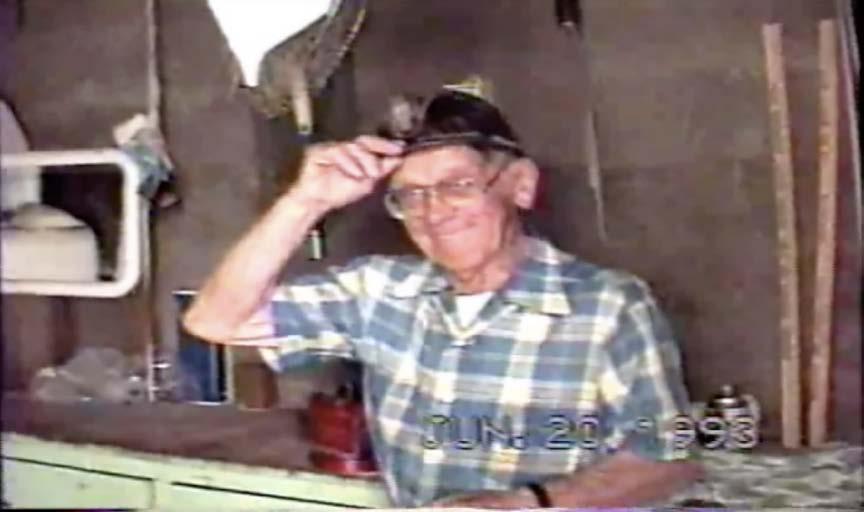

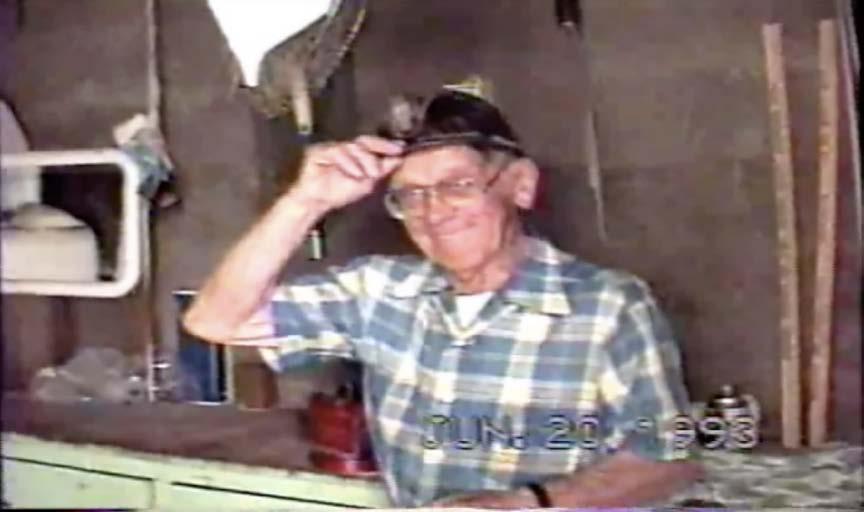

My great-grandpa, Frank Novak, wearing his coal miner’s hat. Taken from a family home video from June 20, 1993.

LIFE IN THE MINES: A FAMILY STORY

Coal mining was grueling labor. My grandmother, Francis Sines, recounted her father’s life in the mines:

“He [Frank Novak] worked for most of the time in D.O. Clark until it shut down, then they moved their house to Rock Springs and he went to work at the mine in Quealy which was a few miles from Rock Springs. The mine there wasn’t in good condition to work in. Some of the tunnels were barely high enough for the little coal cars to fit. When he had to move the cars, he had to sit in the car and duck his head down so it wouldn’t hit the top of the coal tunnel. His brother, my Uncle Tony, worked there too but he worked outside. But one day, he was by the big coal chutes that dumped to coal into train cars and an empty one broke loose and came crashing down right behind him and cut his leg off by the knee. One foot further and it would have hit him right on the head. And who knows what that would have done.”

“Your great-great Grandpa Leosco was hurt in the mine too. A coal tunnel collapsed on him and broke his back, his legs, and several ribs. The other miners thought he was dead, so they hauled his body up in one of the coal carts. A doctor on-site rescued him and he lived, but he was a few inches shorter after the accident.”

51 V Superior and Rock Springs Historical Archive

52

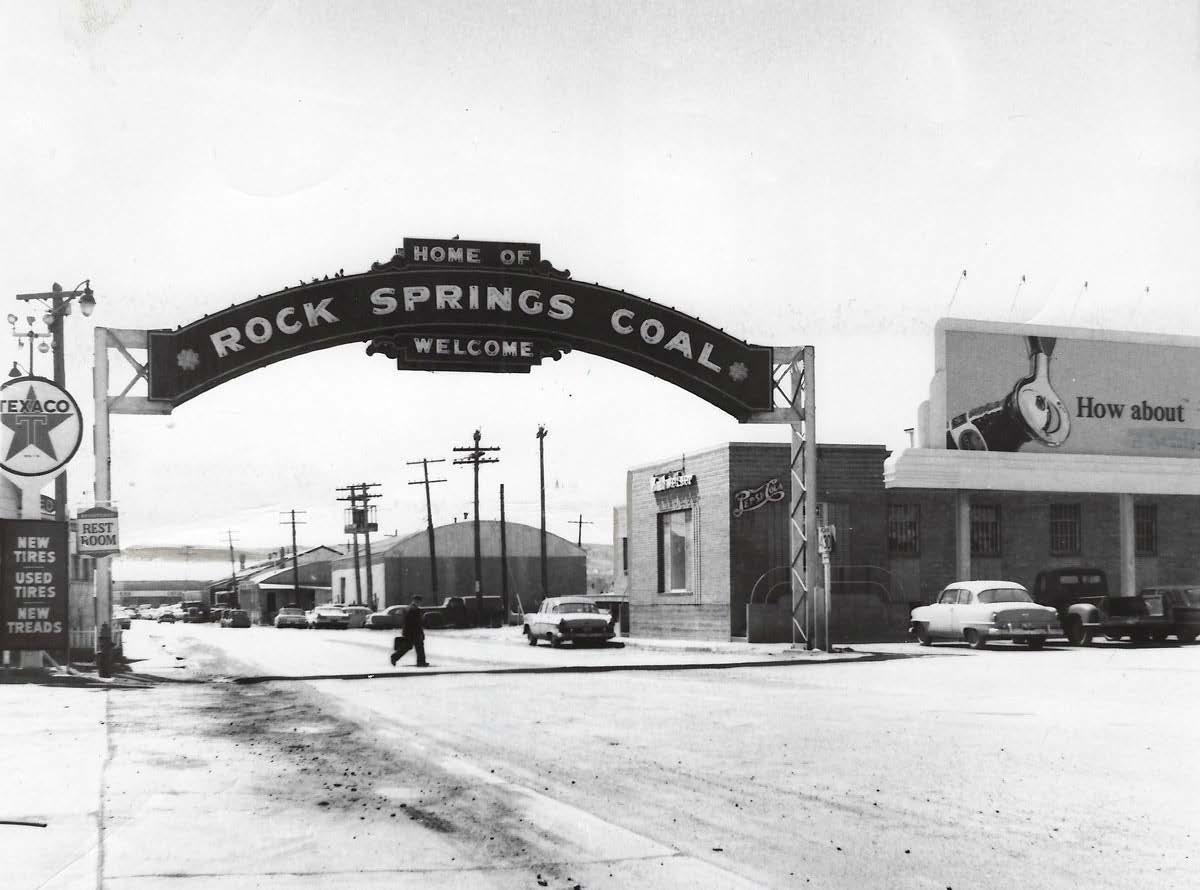

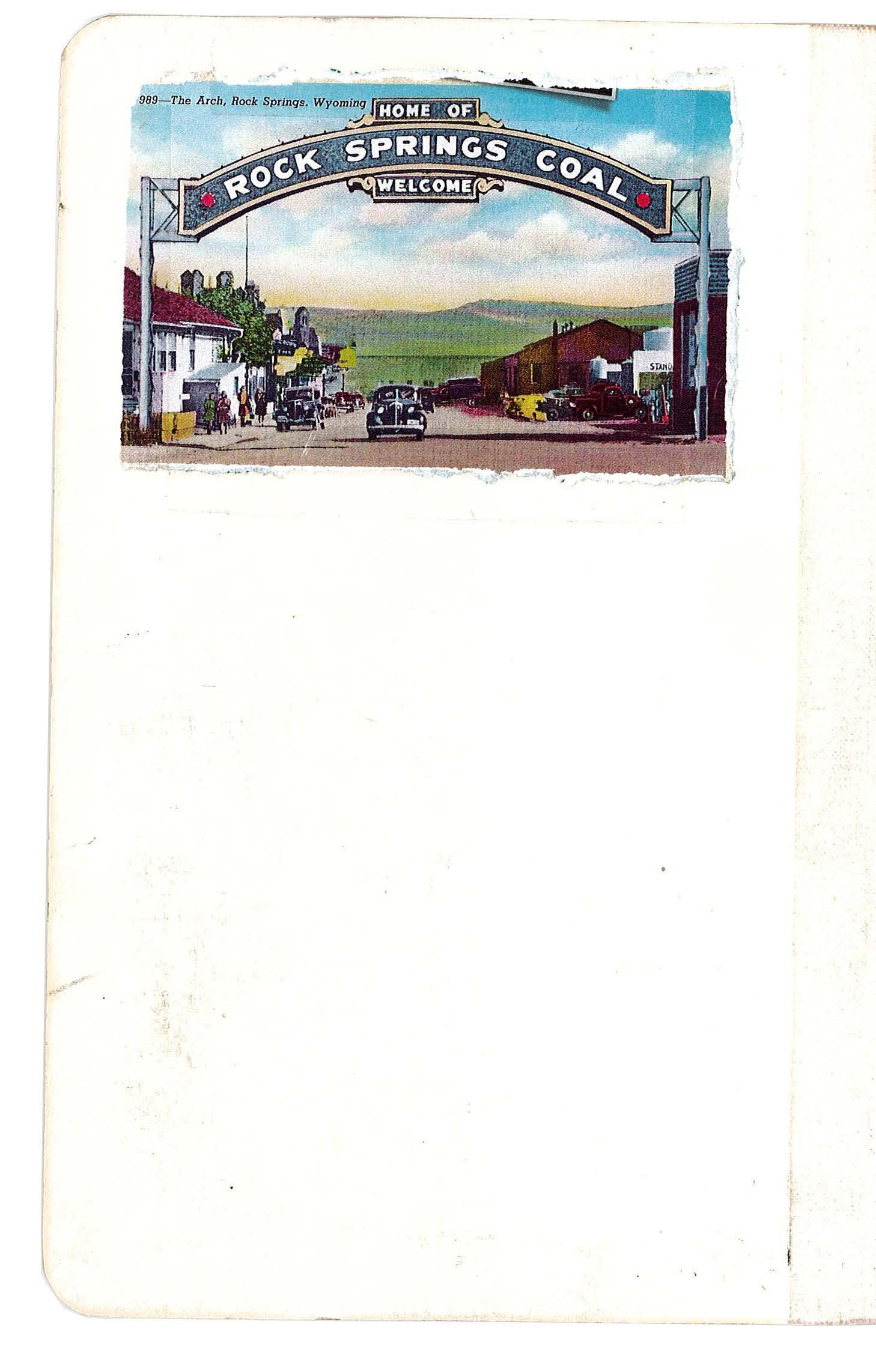

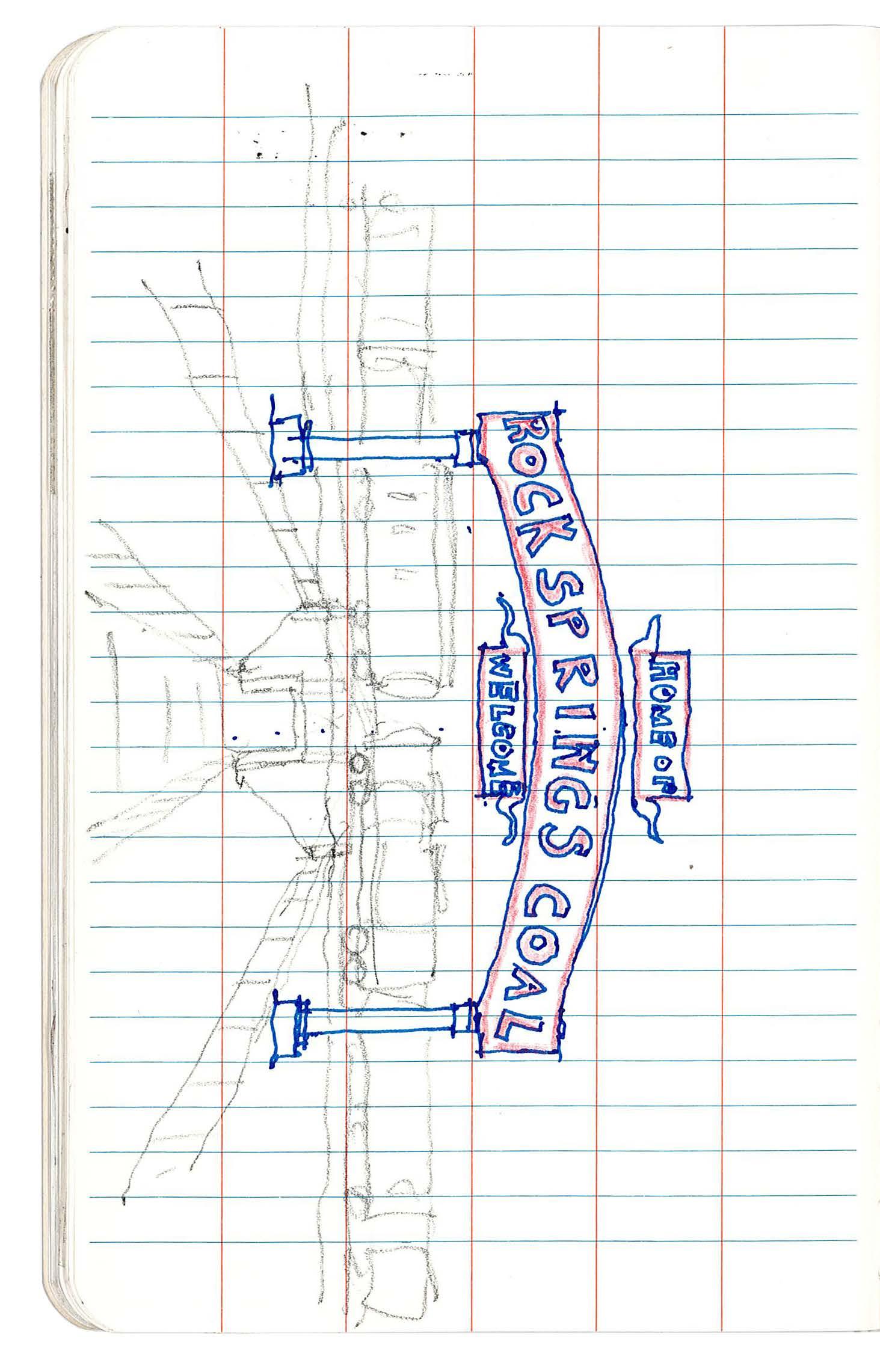

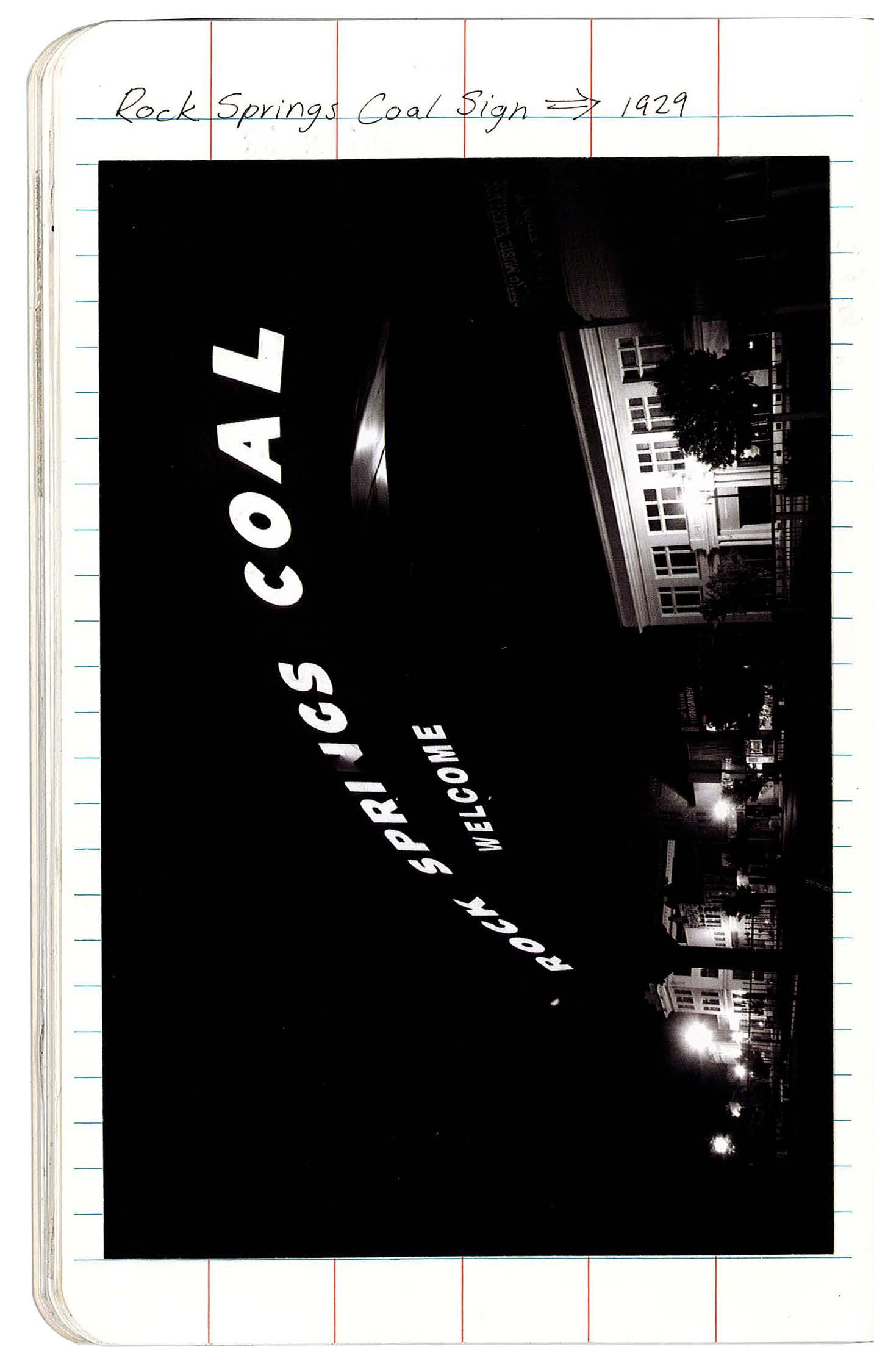

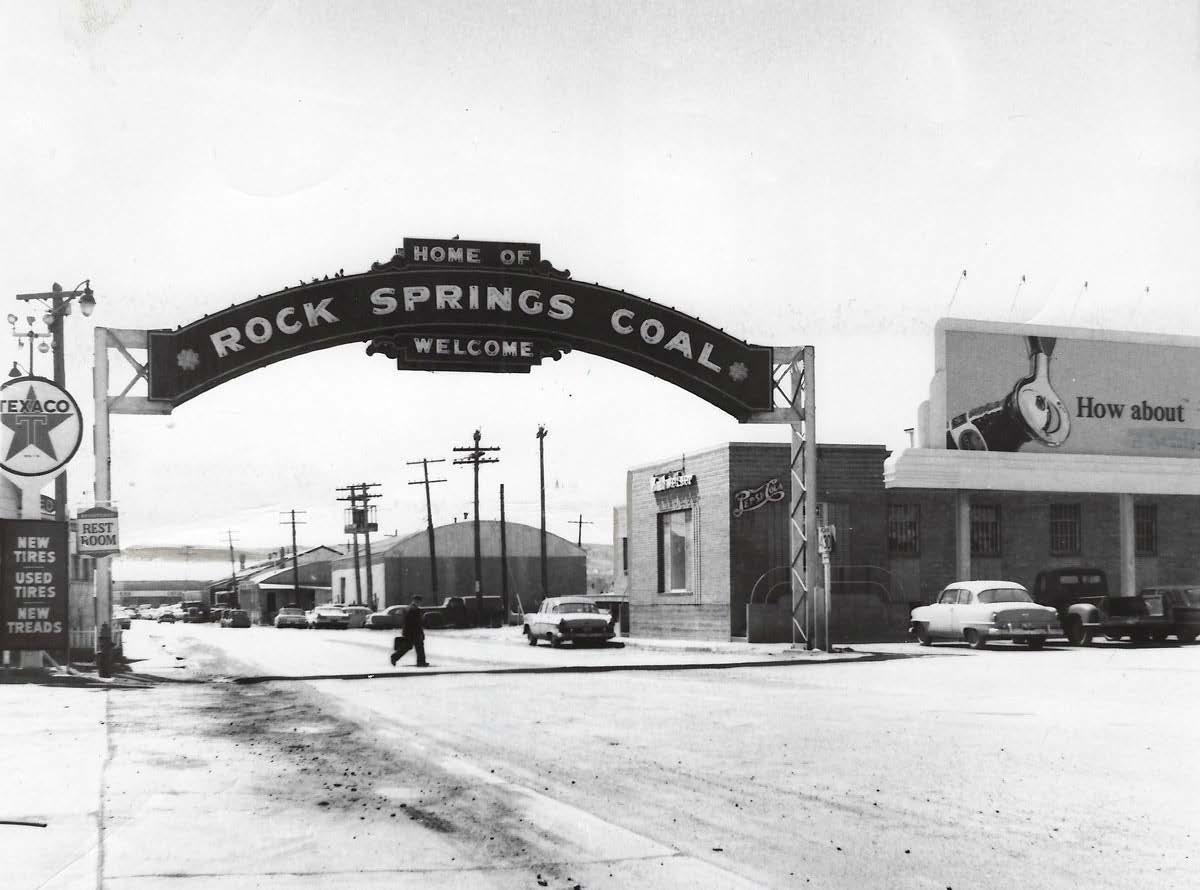

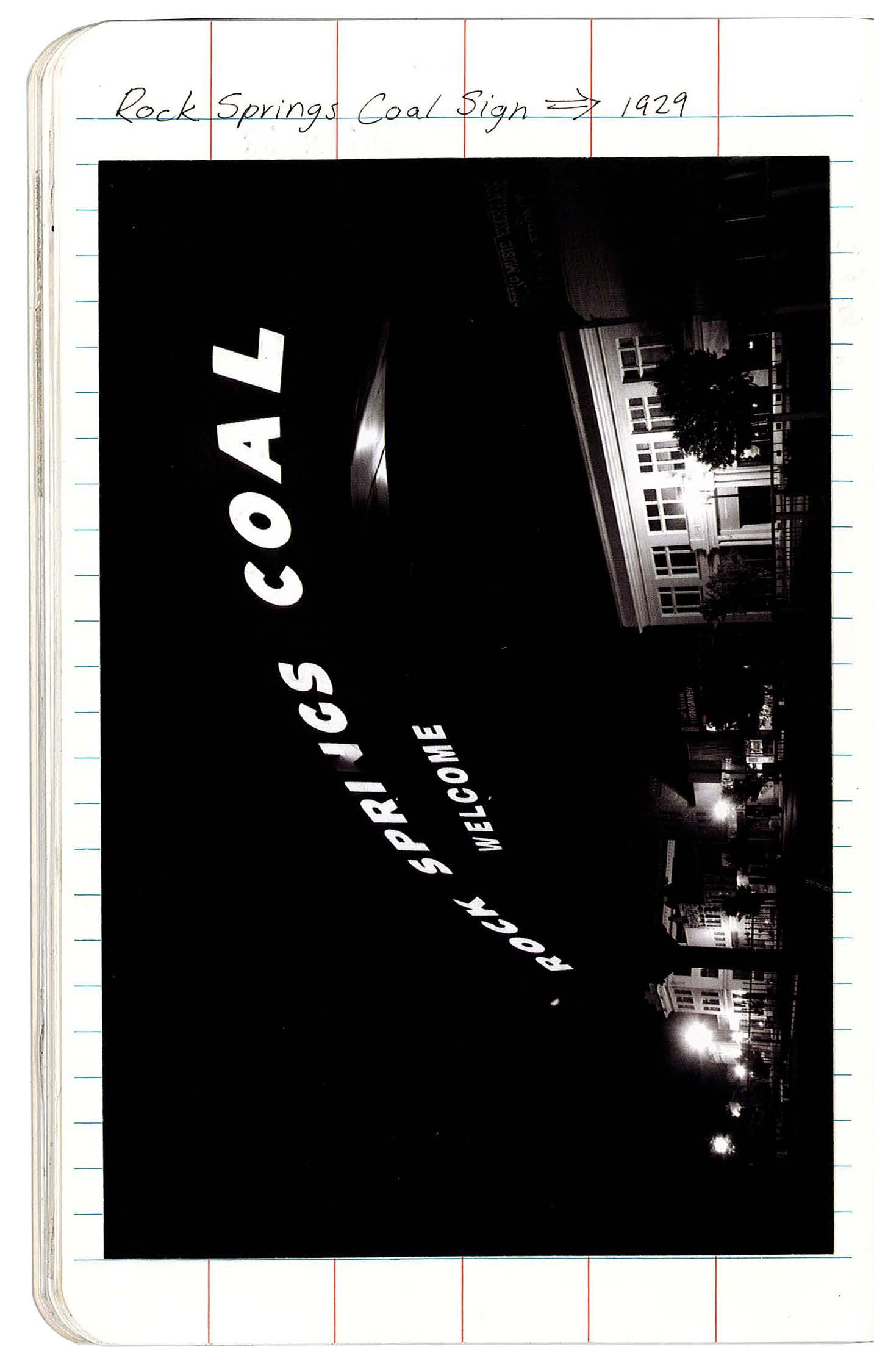

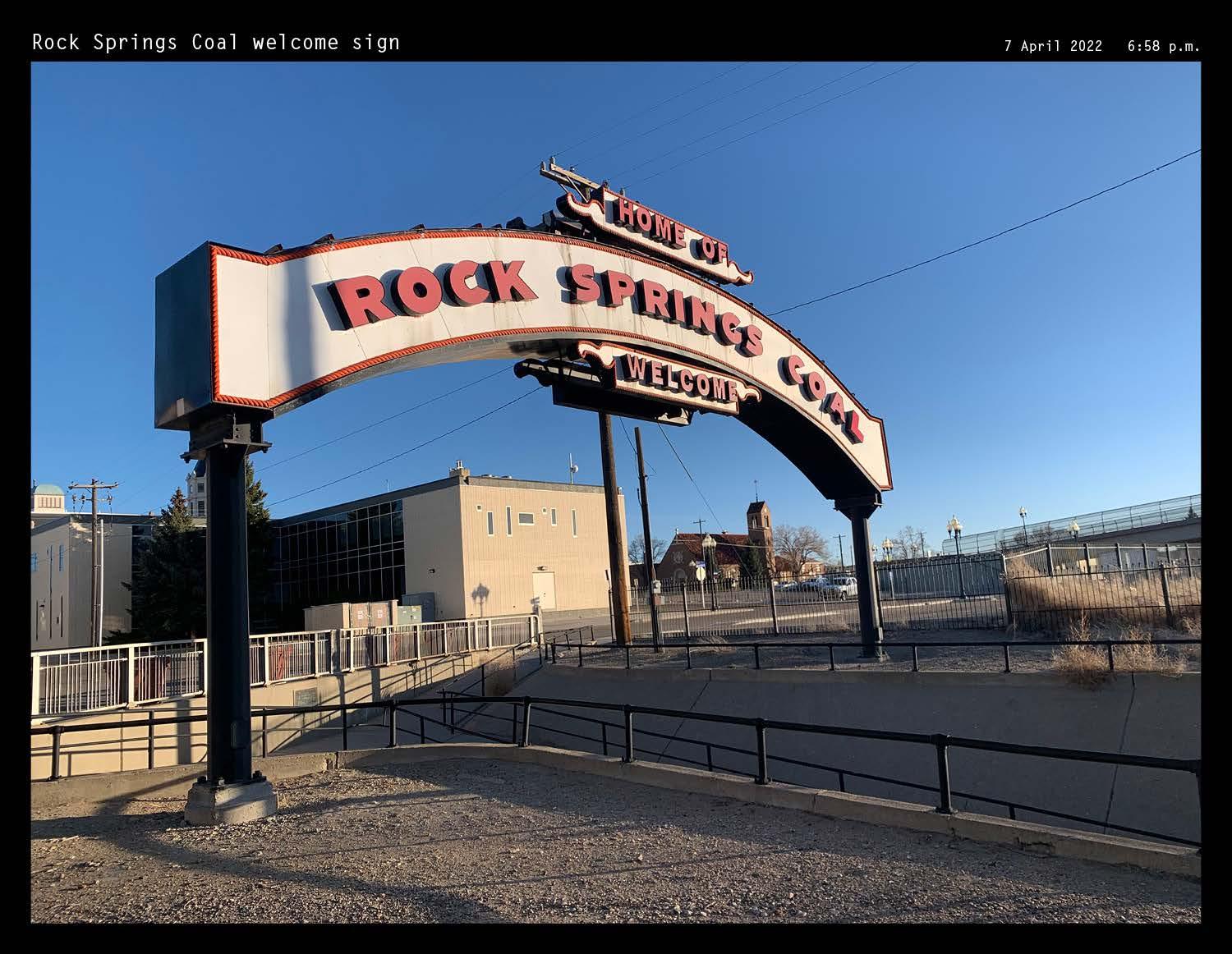

Rock Springs welcome sign in 2022, photo by author

Historical information from: (Prevedel 2011)

Rock Springs welcome sign in 1955, photo from The Sweetwater County Historical Museum

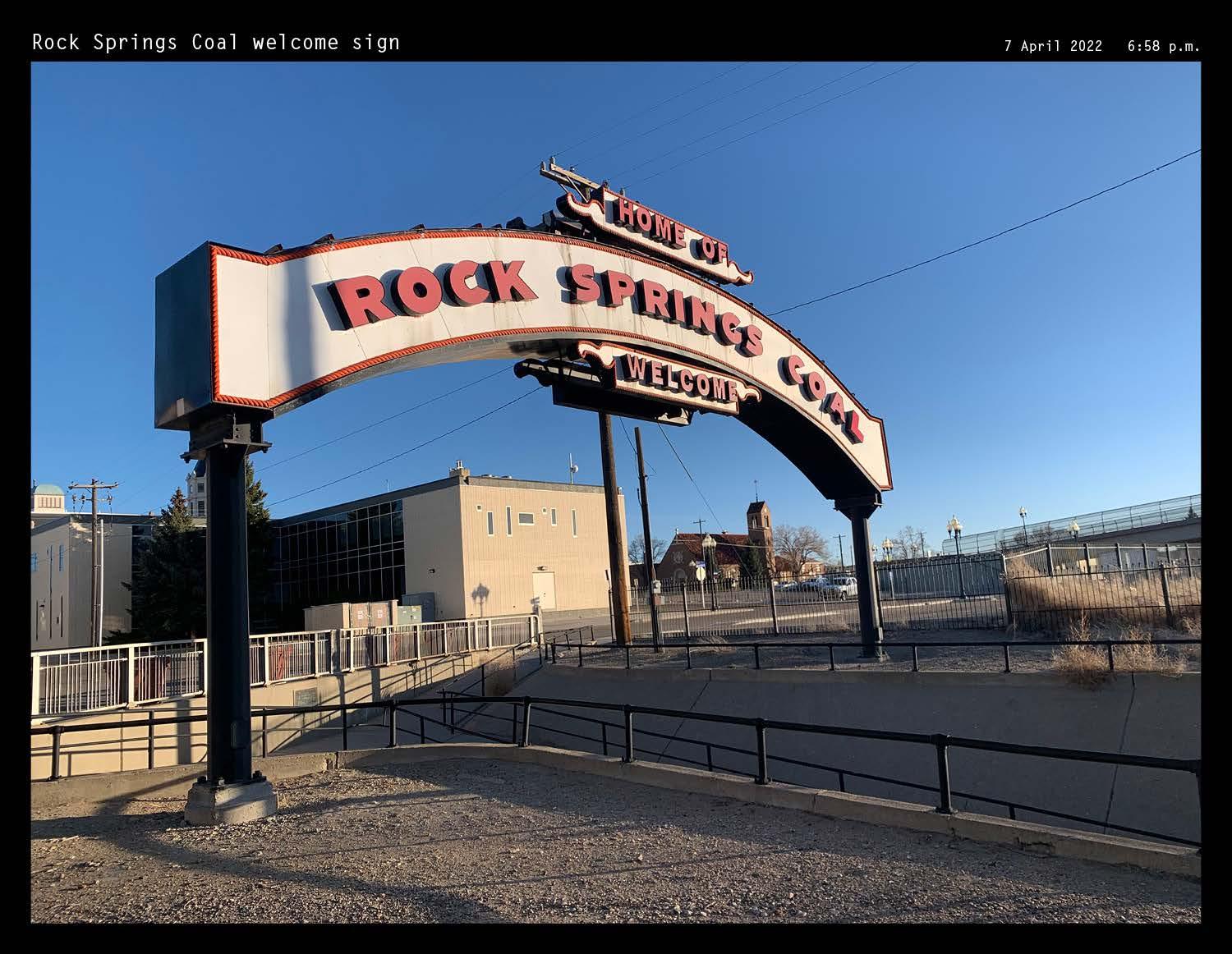

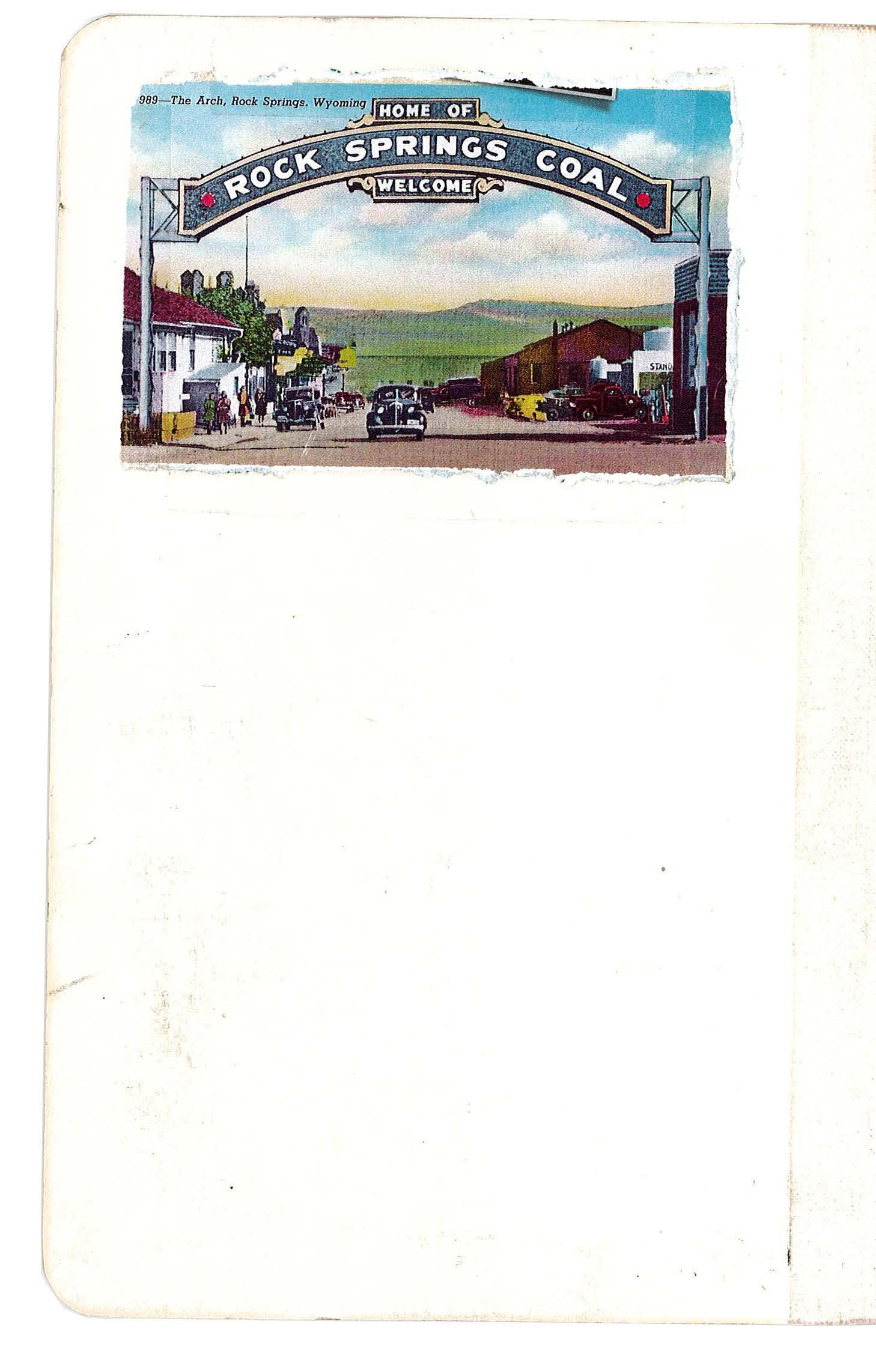

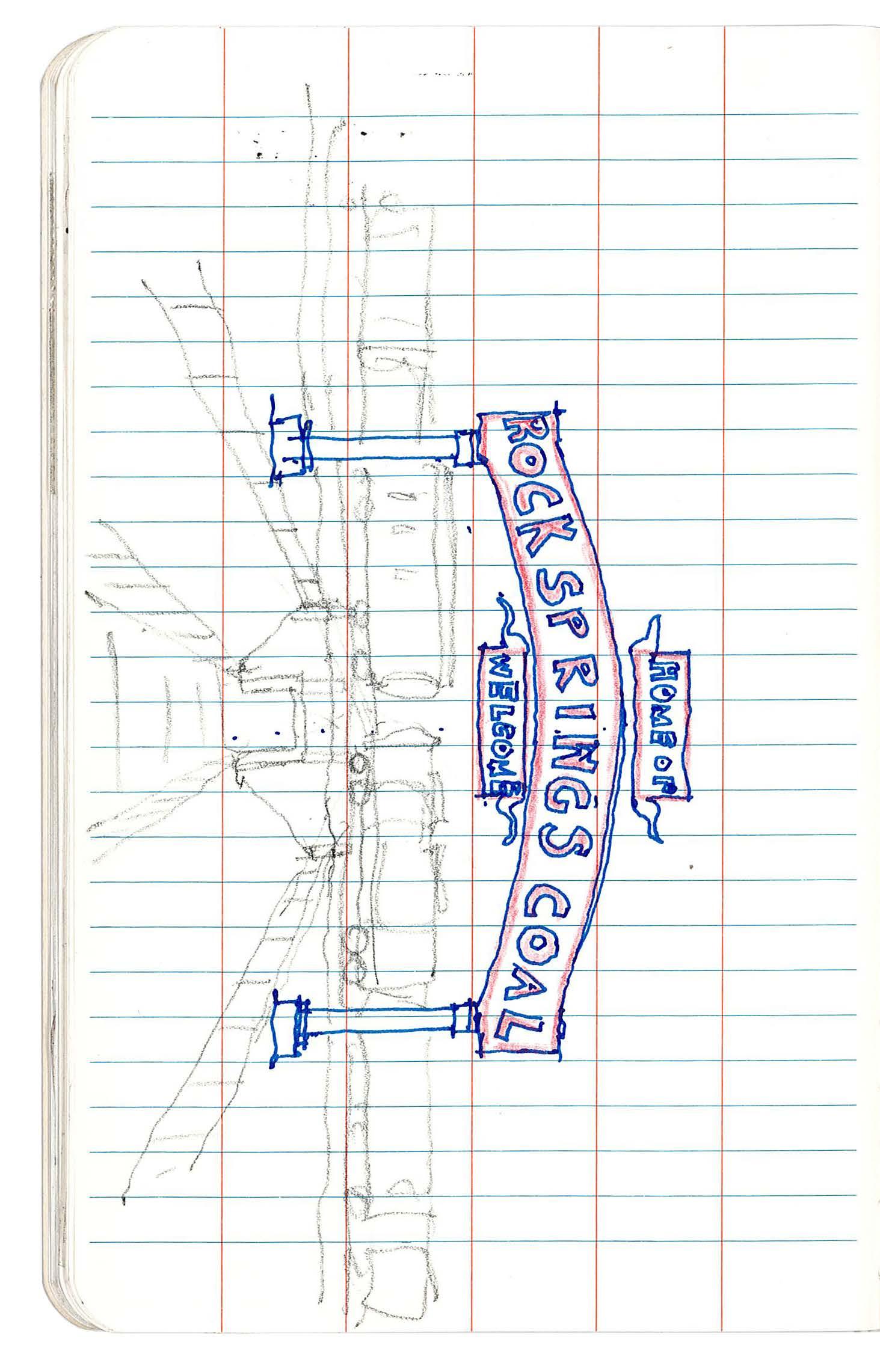

Both Rock Springs and Superior started out as fully reliant on the coal industry, and their economic dependency still strongly relies on extraction. A majority of workers in Rock Springs today work in fields related to the energy industry, whether it be at power plants, as oil field workers, or as trona and potash miners. The community already feels repercussions from the declining coal industry, and worries about what might happen when the Jim Bridger Power Plant closes in the future when energy becomes renewably generated.

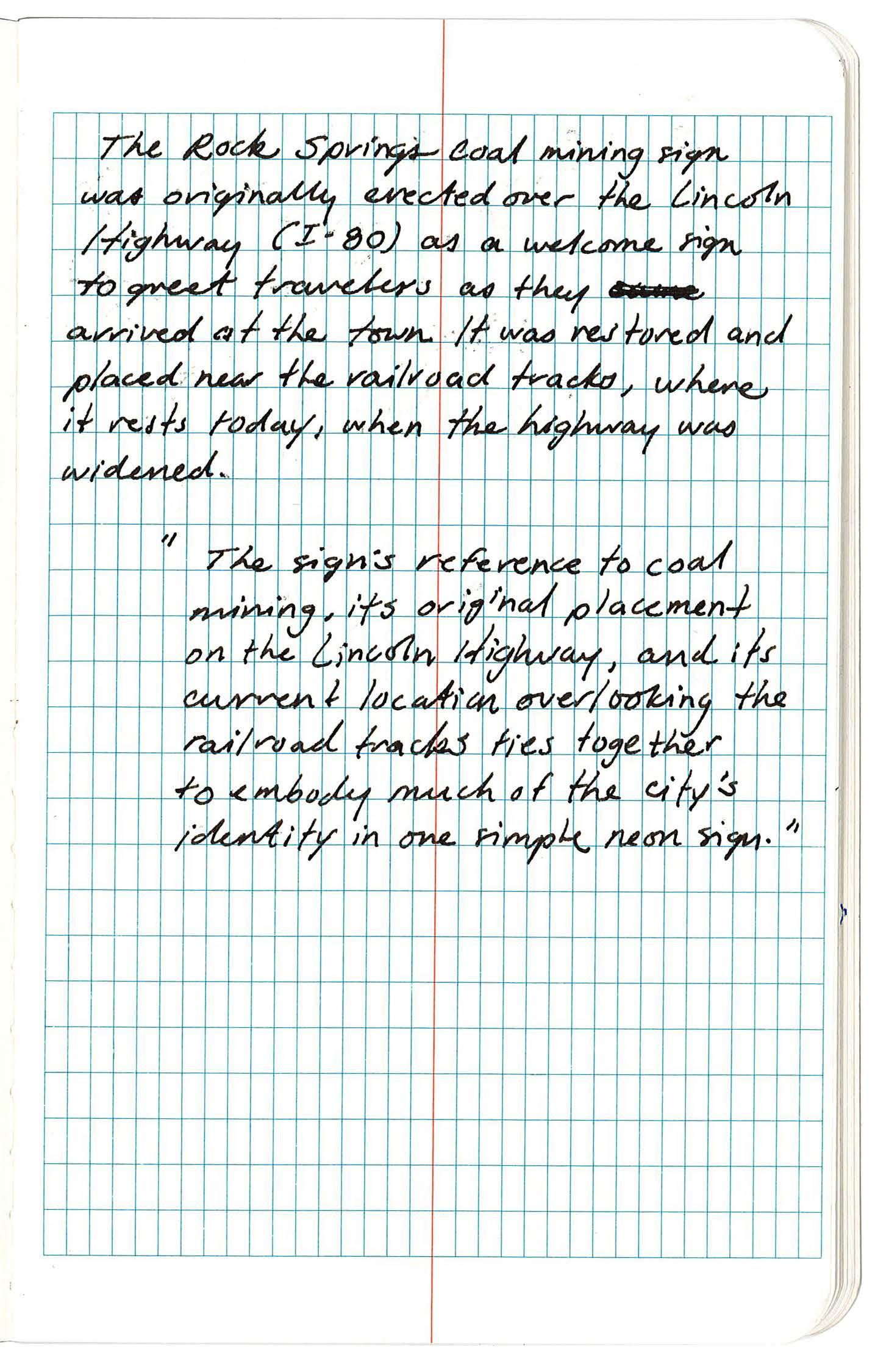

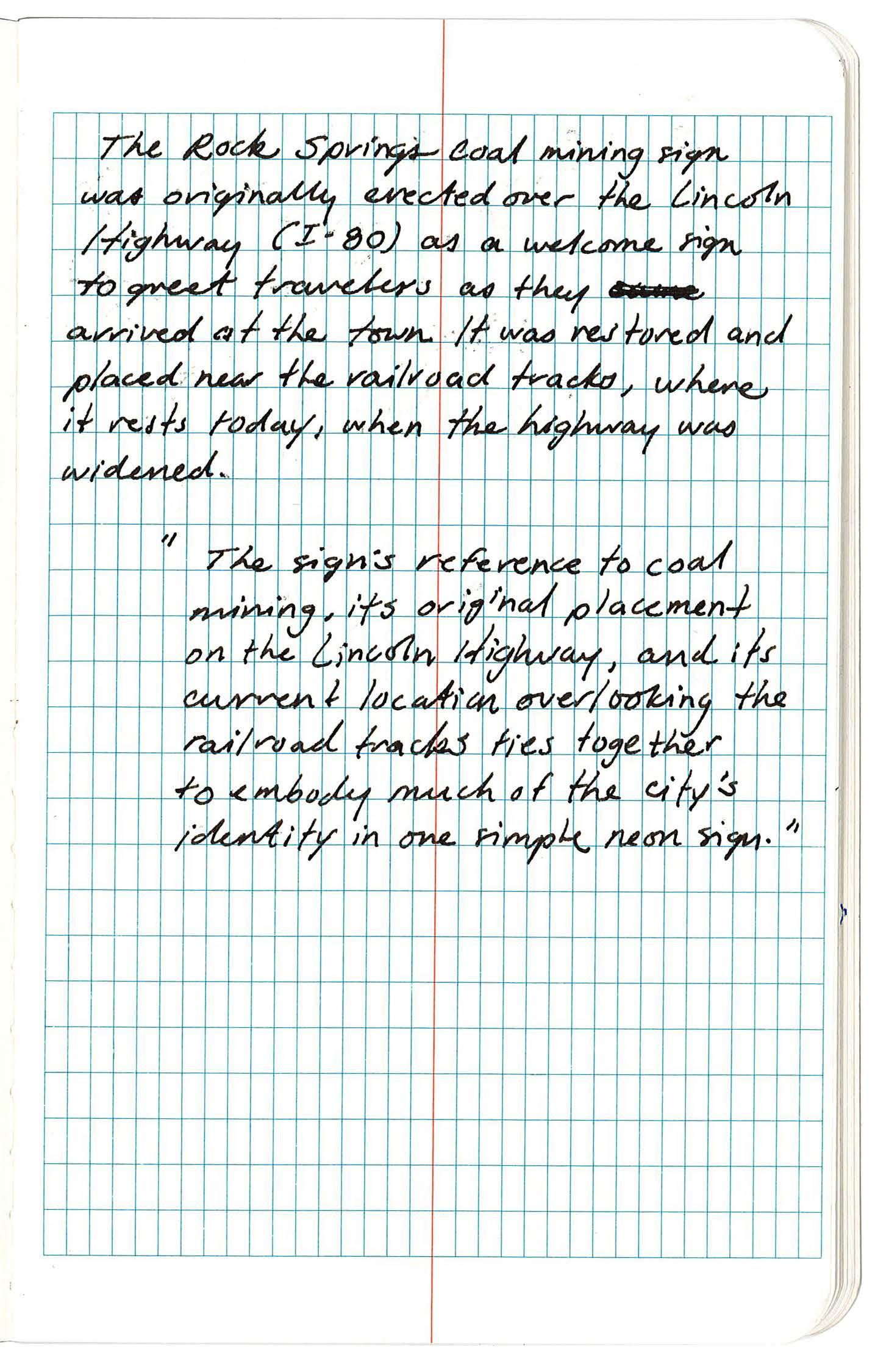

The Rock Springs Coal sign is an emblem of the community connected by the coal industry.

53

SISTER TOWNS: SUPERIOR AND ROCK SPRINGS

Downtown Superior in 2022, photo by author

Downtown Superior in the late 1940s, photo from the Superior Historical Museum

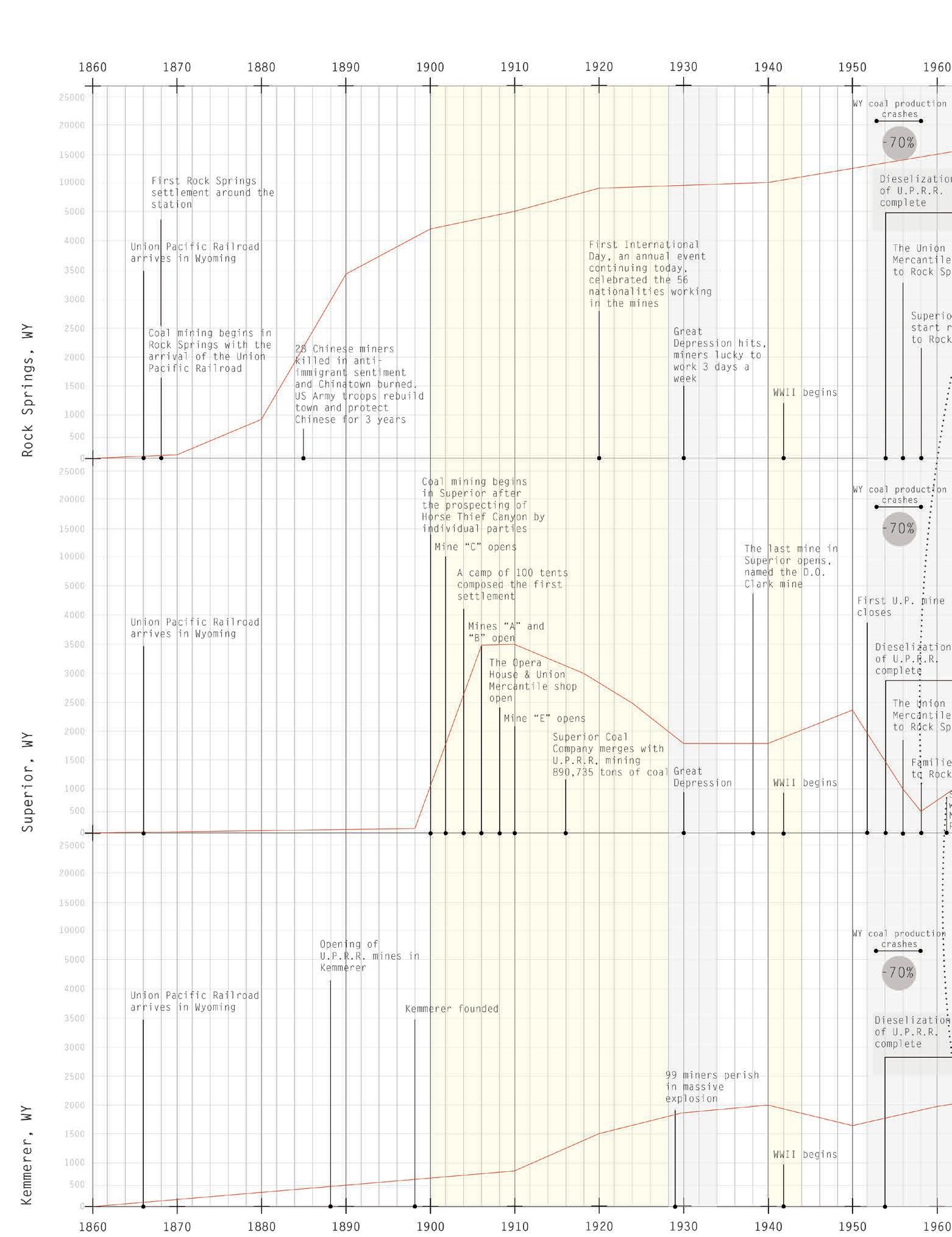

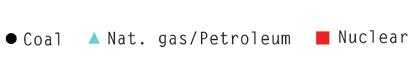

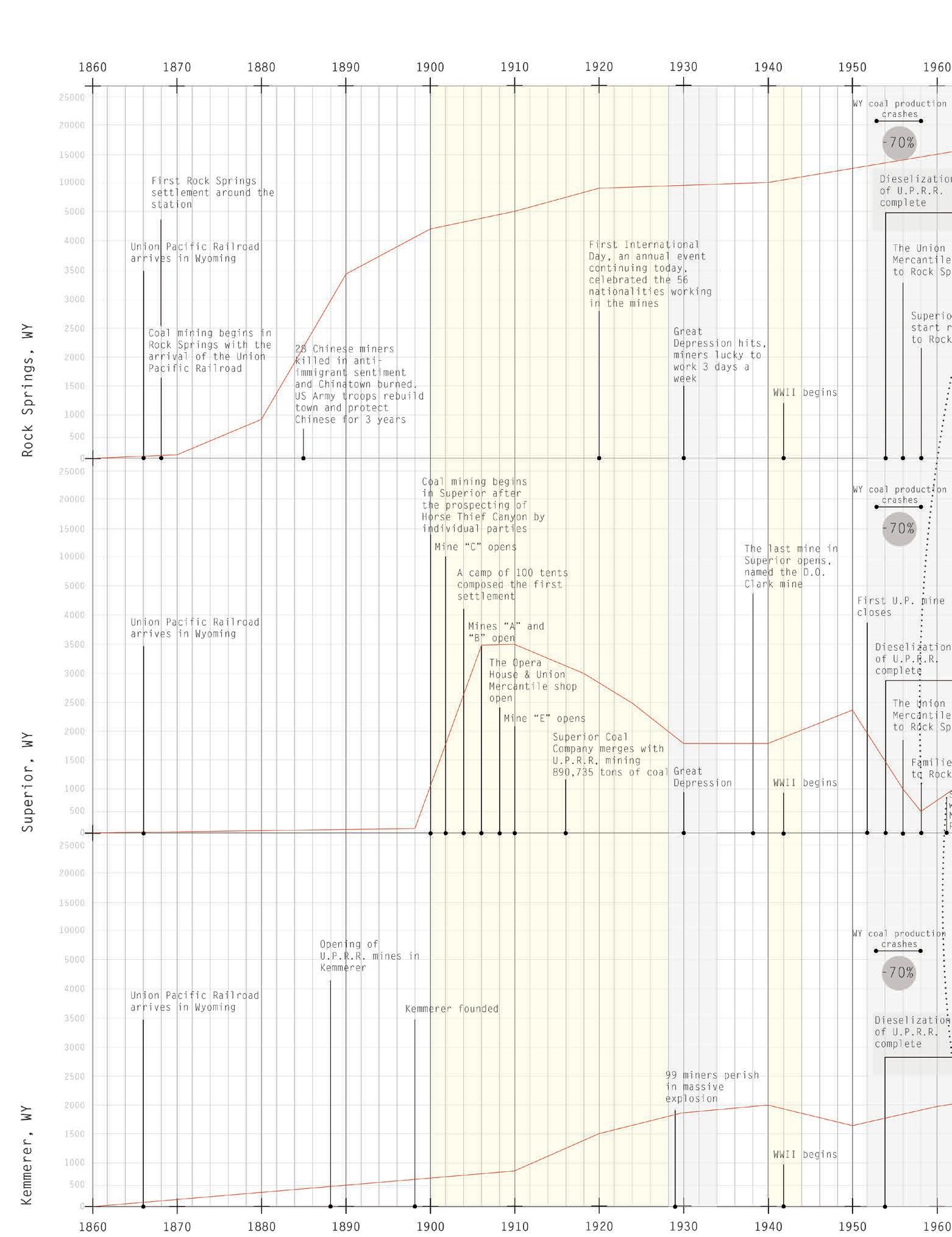

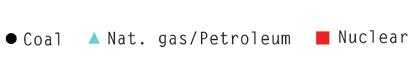

Historic and population data from: (Prevedel 2011) and (Shanks and Tanner 2008)

54

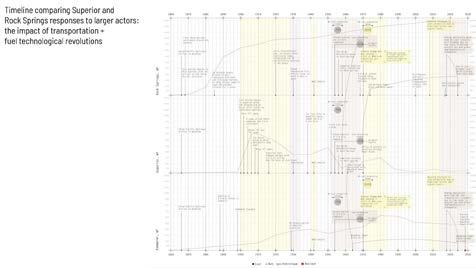

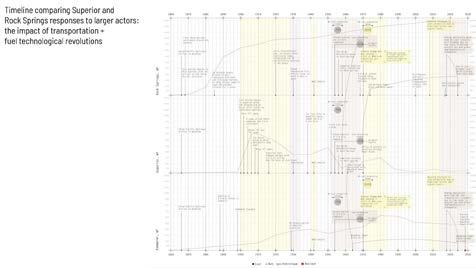

POPULATION FLUX IN SUPERIOR AND ROCK SPRINGS DUE TO ENERGY TRANSITIONS

Rock Springs and Superior had different responses to external processes, boom and bust patterns, and fuel technological revolutions. After the dieselization of the railroad after WWII, Rock Springs embraced the new form of energy while Superior collapsed into a ghost town, relying solely on coal extraction. The red line shows the fluctuating population of Superior as it becomes a support city for Rock Springs’ new mining operations.

55 V Superior and Rock Springs Historical Archive

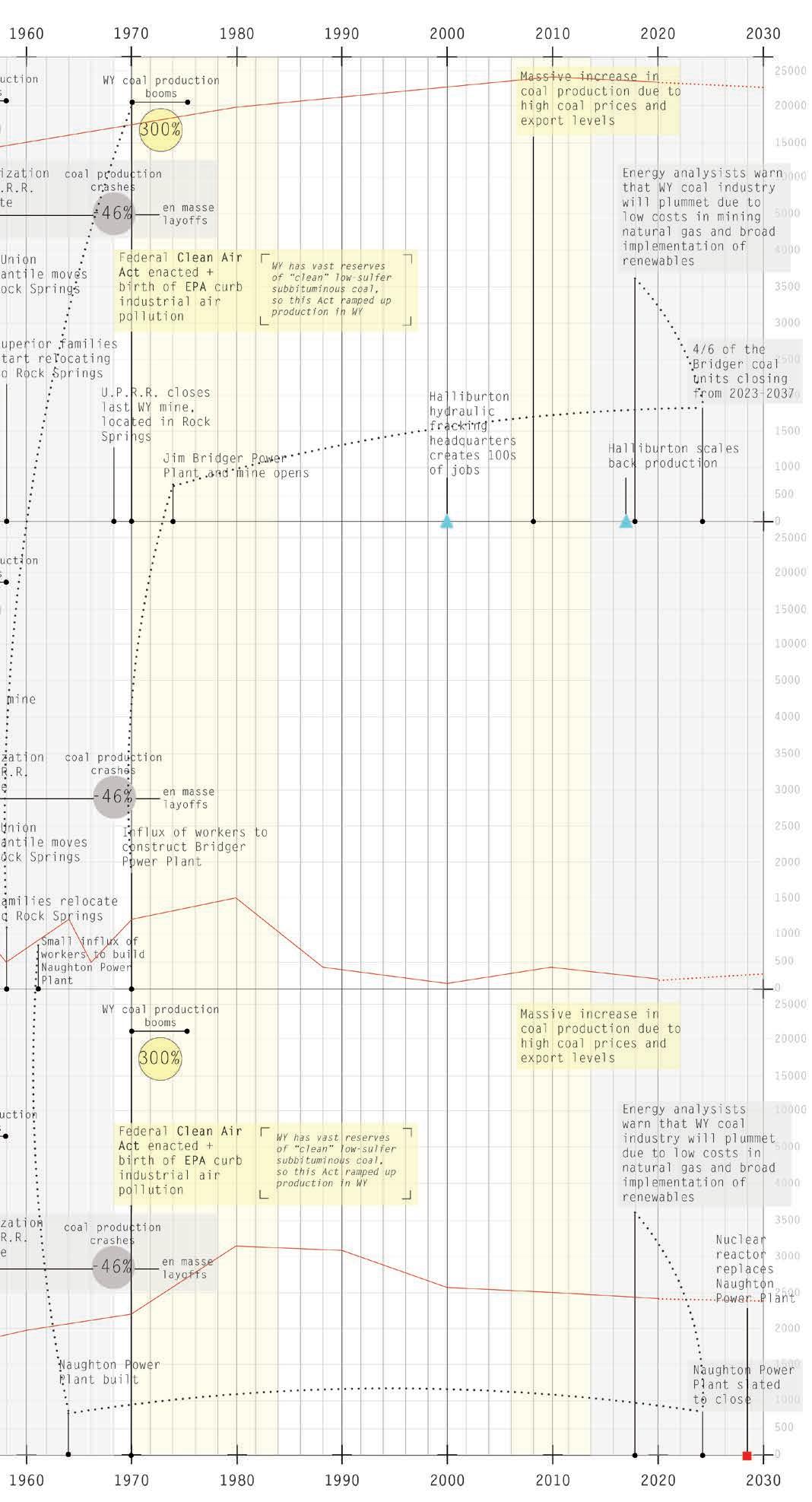

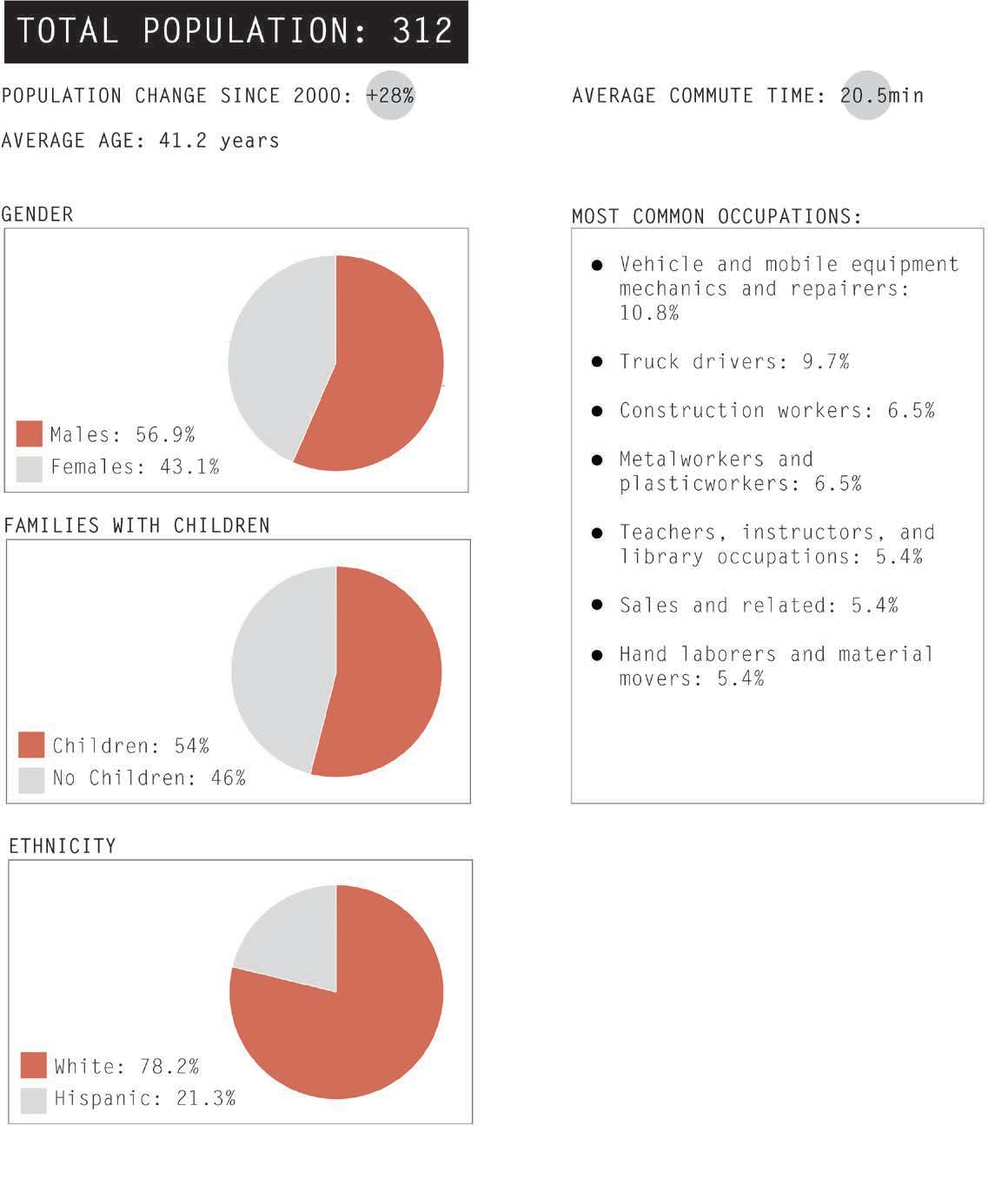

56 Demographic information from: (CityData.org 2020)

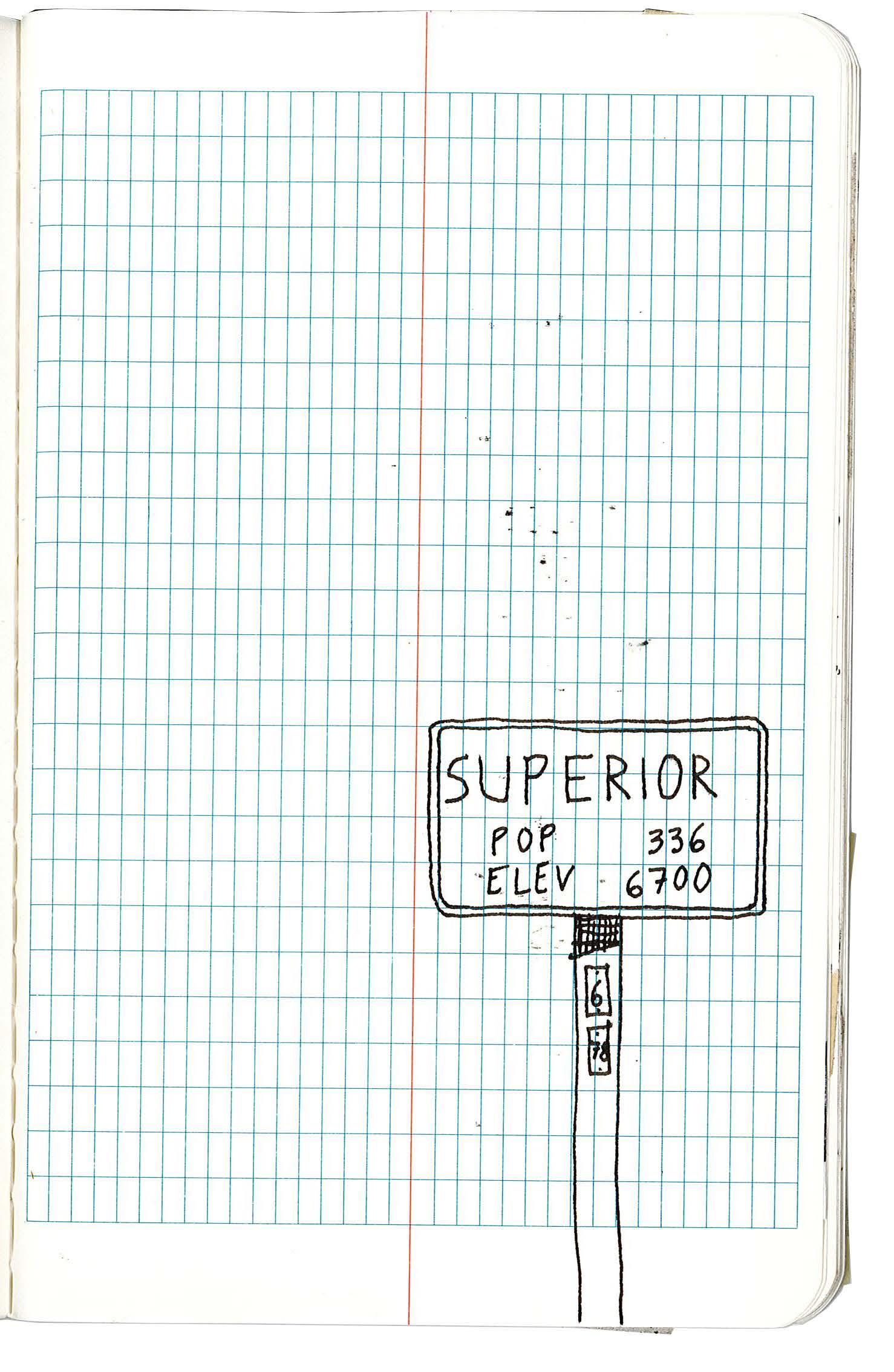

PRESENT DAY DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION FOR SUPERIOR

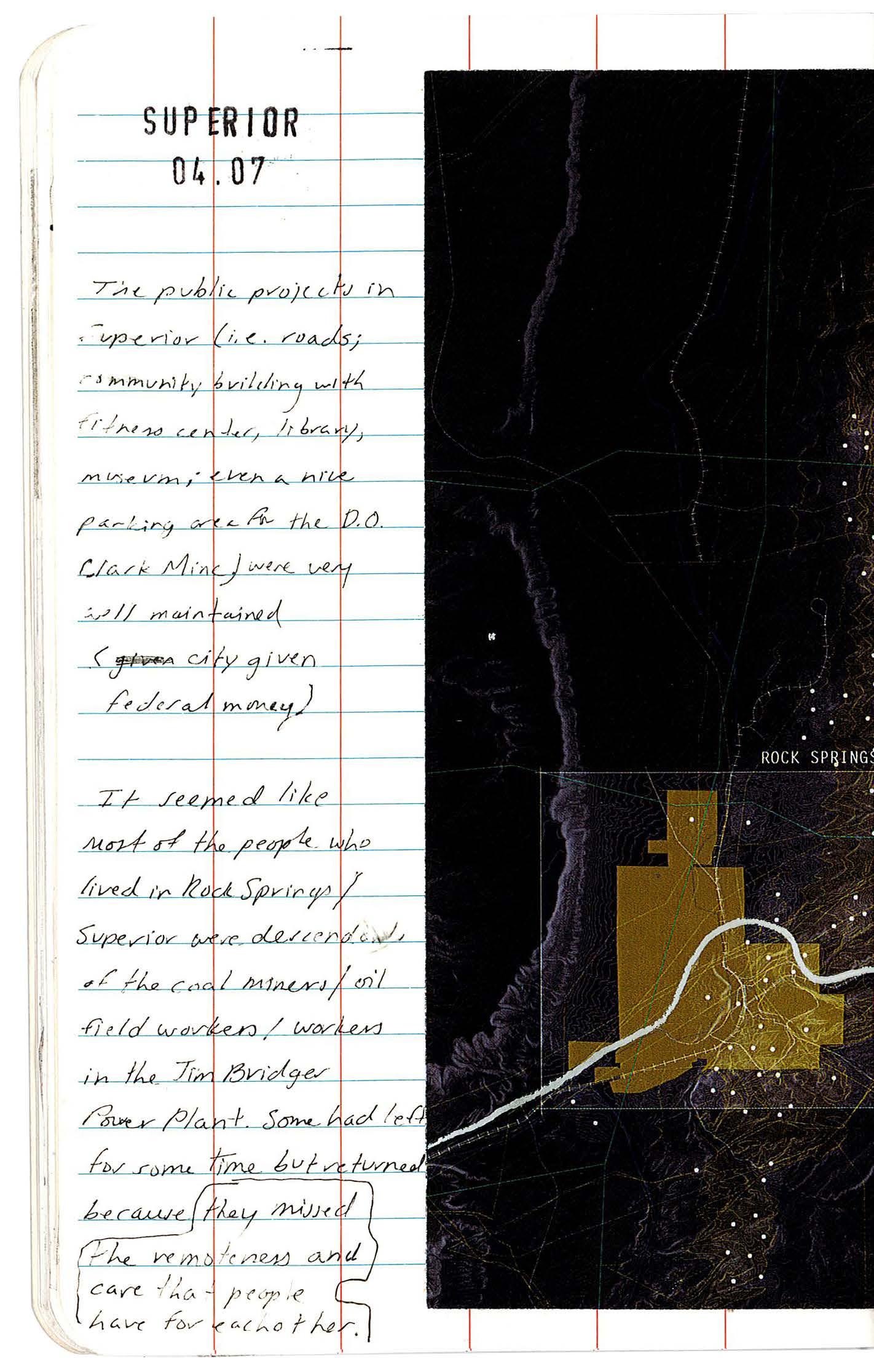

312 hearty souls live in Superior today, most commuting twenty minutes to Rock Springs for work. A majority of people work in the petroleum vehicle industry and in oil and natural gas extraction.

57 V Superior and Rock Springs Historical Archive

On

NATURE OF EXTRACTION INDUSTRY

In early Superior, people traveled to and from Rock Springs with a horse and wagon, taking a full day. In 1903 a railroad from Superior to the main rail line was constructed to carry coal, frieght, and passengers. It took 2 days to get to Rock Springs.

58

Oregon

Pony Express,

I80 closely follows the route of the original Lincoln Highway, the first road across the US. It also traces the

Trail,

and the Transcontinental Railroad

sign bids

Interstate 80 a

one to visit a “living ghost town”. Should you follow its advice, after a 7 mile journey through Horse Thief Canyon you would come upon Superior Wyoming once a thriving community dependent upon its coal mines.

A very long train. Lots and lots of trucks. Very windy. The last sign I saw back there it said ‘Superior.’ 00:00; 0mi 1 Truck Driver Livestream I-80 Pre-bust 2022 06:52; 1mi 12:63; 3.5mi 14:41; 5mi Trains along the Union Pacific Railroad, which flanks I-10, usually carry coal down to Texas. The original Rock Springs train depot was built in 1868, right after the railroad itself. It was the entryway for thousands of immigrants as they sought work in the coal mines or a new life. Car on display in Superior behind a WWII monument Nowadays, I-80 is mostly used by transcontinental truckers carrying goods and by tourists crossing the Rocky Mountains. 00:00; 0mi 1 Tourists ENTRY TO SUPERIOR Pre-bust 2022 Displayed relics of the past greet a visitor upon entry 06:27; 2.6mi 08:03; 4.7mi 09:25; Transcontinental Railroad I-80 Frontage road Bitter Creek Road 371 I-80 Horse Thief Canyon THE GREAT DEPRESSION With the Depression came a reduction of both freight and passenger trains on the U.P.R.R.

RELIANCE ON COAL TO POWER TRAINS

Passenger and freight trains relied completely on coal-fired engines. This highly increased demand for coal especially during WWII.

prices

lithium,

BOOM/BUST

With the rapid rising and falling of

on coal, oil/gas, or

town populations skyrocket or plummet within a matter of months. Superior fell in and out of its “Ghost Town” status as the US economy shifted on a large scale.

I-80 TRUCKING

Although Superior is only 7 miles away from a major trucking route, truckers take pit stops at Rock Springs since it’s easier to access and there are more amenities. Occasional tourists, drawn in by signs, visit to see a “Ghost Town.”

FOOD INSECURITY

CINEMATIC FORENSICS: DISSECTING

FAMILY HOME VIDEOS

Dissected and transcribed family home videos piece together memories of a once-booming energy boom town. Tying together larger-scale political and economic events, like the Great Depression and World War II, with present day plans of Superior reveals how patterns of livelihood and reactions of the community relate to personal memories of an era long past.

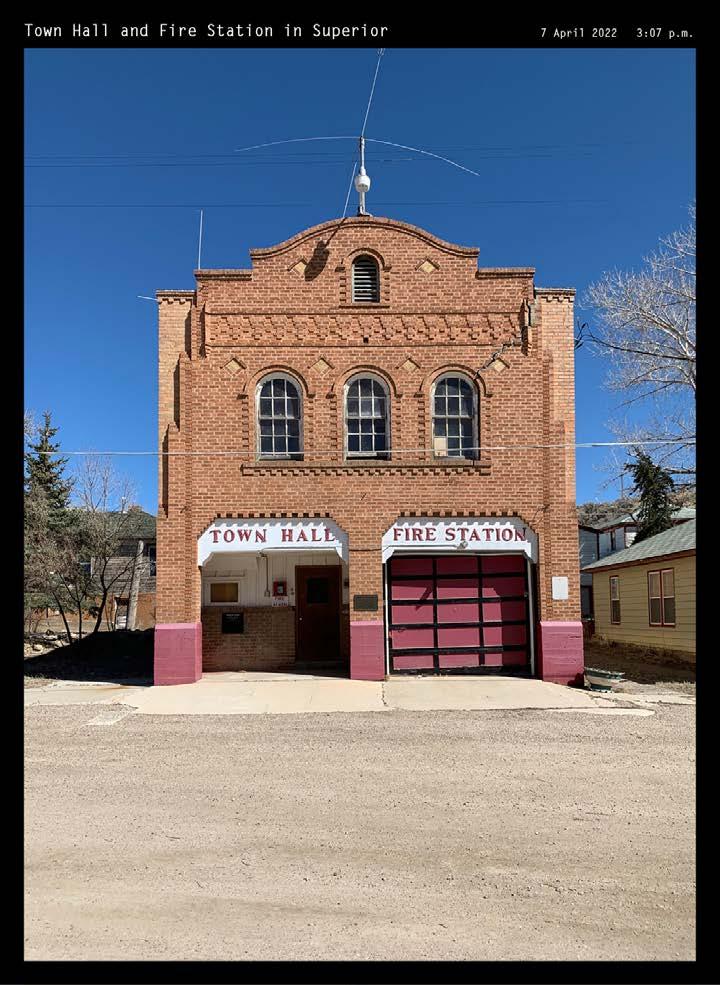

59 “Alberta Hotel” Pre-bust “Here’s good ole’ downtown Superior” Currently the Horse Thief Saloon 00:00; 0ft 00:13; 341ft “Mom used to work at this store right here on the end when she was a girl” “And she worked for V over there, that butcher shop” Novak Family Video: 1993 “A good ole’ ghost town” “And then she went to Rock Springs and worked for the telephone company for a whole month, she didn’t like it, “Here’s a little store that used to be, it looks like someone’s working there” “Oh, there’s the bank” 1 2 3 4 “And there’s the Union Hall right there” “Grandma and Grandpa used to live “Oh yeah, 00:13; 341ft “The senior center” 00:31; 652ft 00:47; 1025ft 00:47; 1025ft 00:58; 1231ft 2022 “Working Mens Commercial Co.” Grandma would be sent down by her family to get a bucket of beer for parties. Superior maintains over five acres of parks, two modern public restroom facilities, baseball diamond, basketball court, children’s play grounds, lighted tennis court, picnic tables and shade trees. “Here, preserved, lie epoch tales of the town’s origin, rising through the heydays and the hard mining life awaiting numerous immigrants and pioneers.” DOWNTOWN Union Hall finished construction in 1922, paid by the Union Mine Workers of Superior. Miners of Superior paid $2 a month to cover the cost and maintenance of the building. Every Saturday the Union held meetings in the mornings and dances in the evenings. Over its lifetime it contained a grocery store, saloon, doctor’s and dentist’s offices, a bowling alley, dance hall, and offices. The Union Pacific Coal Company wanted the miners to enjoy life and have a community spirit while working for them. Numerous saloons and dance halls added to the recreational facilities of the town in the 20s and 30s. The Workingman’s Store was established in 1910. It was a department store and carried dry goods as well as meat and groceries. During the coal boom There was a garage and filling station, Golden Rule Novelty Store, Laundry, Western Meat Market, Shoe Repair Shop, Bakery Shop, Bank, Dentist office, Alberta Hotel, Drug Store, Duzik Grocery Store, Beauty Shop, Jackson Café and Rooming House, Gratton Café, Harshbarger Barber Shop, John Bettra Barber shop, Pruja Pool Hall and Saloon, Palace Bar, Eagle Pool Hall, White City Bar, Combination Bar and Pool Hall, Houses of Prostitution or “Cat Houses”, the Union Hall and the Finn Hall. The railroad tracks ran through the main part of the town and on the other side of the tracks was the Crystal Theater, Angeli’s Garage, Town Hall and Fire Station. The town built a 50’x90’ swimming pool, financed and built by the community. The water came from the mine and was chlorinated and changed weekly. A large lawn was sown with grass and clover and 50 trees planted for families to enjoy. New community park where the swimming pool was The same view today; many buildings were destroyed in a fire in 1913 A sign reads: “Coal: It keeps the lights on” 09:25; 7mi Superior, appox. 1913 The Episcopal, Mormon, and Catholic Churches held services in the building. Administrative Building (includes the Mayor’s office, Senior Center, Community Room, Fitness Center, and Library Union Hall Post Office Horse Thief Saloon Town Hall & Fire Station Proposed site Public Building (will be an emergency shelter for and outlying commercial kitchen, public showers, restrooms, weddings & funerals, $500,000 business council grant

Superior was deserted as people left to Rock Springs to find new work in Rock Springs. Many downtown Superior businesses went bankrupt, never to recover. POST-WWII

groceries

shops

food

V Superior and Rock Springs Historical Archive

Even in its heyday, Superior residents traveled to Rock Springs for

since the

in Superior were expensive. Now, there is no

availability in Superior.

WATER SCARCITY

THE GREAT DEPRESSION

Later, the railroad company hauled water from Point of Rocks in tank cars. People waited in long lines to fill their 5 gallon buckets from the pump.

BOOM/BUST NATURE OF EXTRACTION INDUSTRY

DURING WWII

60 whole month, she didn’t like it, the buzzing in her ears” there” “Grandma and Grandpa used to live on the hill up there” “Oh yeah, this must be Dogtown” 00:58; 1231ft 01:04; 1413ft Superior maintains over five acres of parks, two modern public restroom facilities, baseball diamond, basketball court, children’s playgrounds, lighted tennis court, picnic tables and shade trees. Coal life community working facilities 20s The town built a 50’x90’ swimming pool, financed and built by the community. The water came from the mine and was chlorinated and changed weekly. A large lawn was sown with grass and clover and 50 trees planted for families to enjoy.

In the early days, dirty, inky water was hauled in from the mines and stored in tanks. Each family had several barrels of water storage. Barrels of water were 25 cents each from the department store. The water was then hauled throughout the community by wagon, which held twenty and fifty gallon containers.

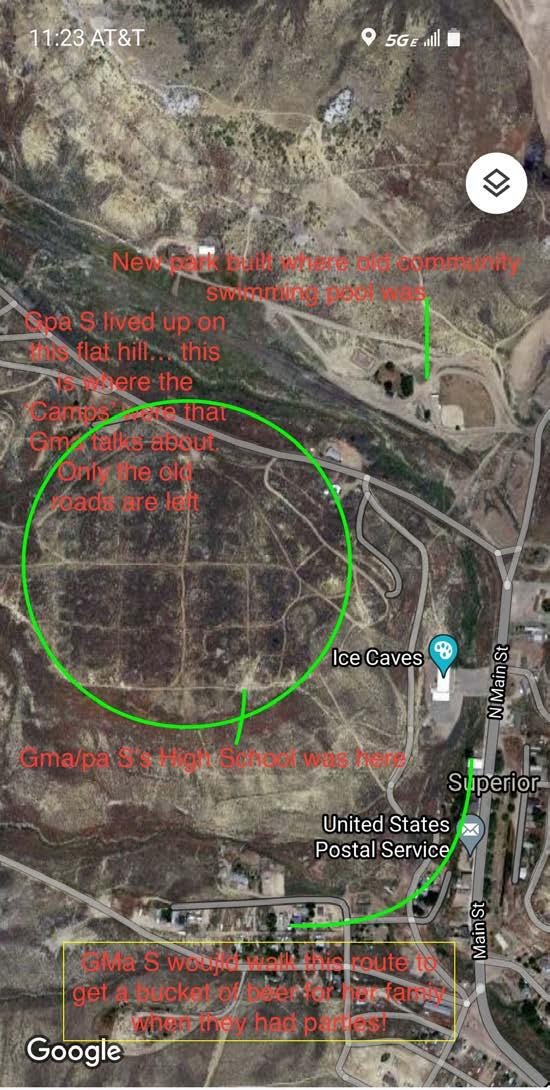

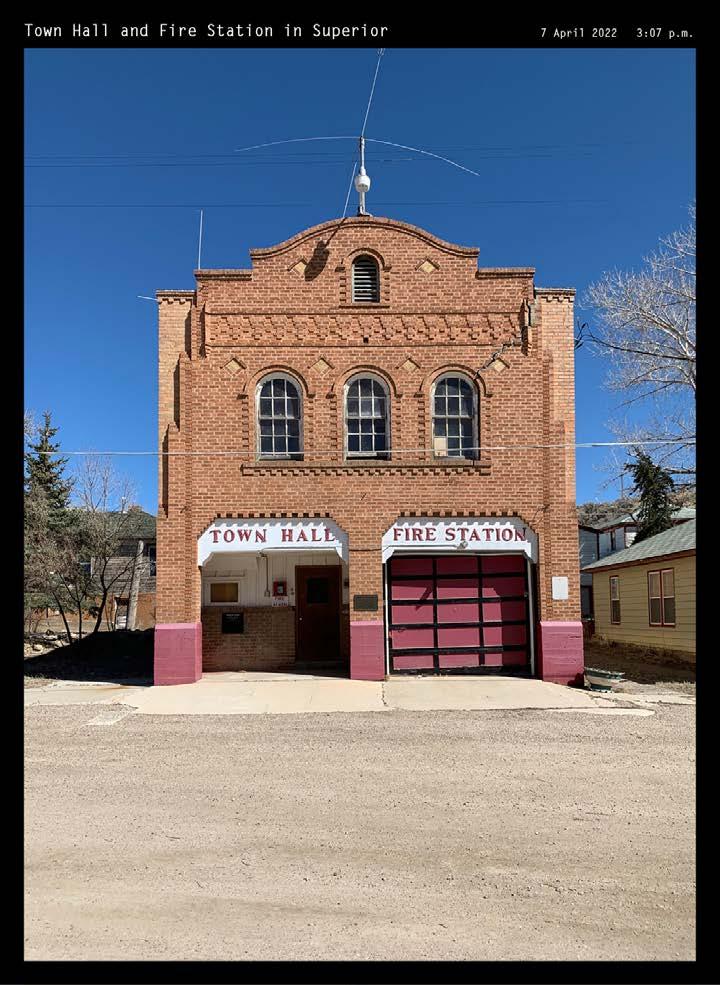

Before 1949, the only public telephone was at the DeGuio Shoe Repair Shop. Due to population influx during Company new residents railroad placed and two larger 01:55; 436ft The town hall and fire station was built in the 30s.The first fire truck Superior had was a cart driven by men and later by horses. The Town Hall now includes a history museum and community gym community park where swimming pool was Pre-bust “This is my parents’ house over here. The garage is gone.” 00:00; 0ft “Oh, that’s their house? It’s still standing. There’s the owner there.” “That white house back there?” Novak Family Video: 1993 1 2 3 4 2022 NEIGHBORHOODS 01:20; 0ft “No, that was just a bachelor pad.” “We lived in that basement for 16 years, it had a big 12’x16’ “In ‘50 we bought that house and moved 01:56; 0ft “This is where we lived right we got married, and where appendix attack. My sister lying on the bed reading and I couldn’t catch my breath. to run out of that door to breath and I hollered.” “That electric meter, there, in for us so we could get power.” “Ah, that’s right. argued about electricity. pay half the electricity whole family, and Grandpa way.’” “Your dad used to live up there on B-hill. “Francis went to school on that Camp houses, 1930s Camp houses, 1920s Superior BoxCar town, 1944 Camp house neighborhood gone, only roads remain Location of old highschool 02:21; 0ft Playgrounds and basketball hoops near town entrance Town Hall & Fire Station Proposed site of new Public Building (will be an emergency shelter for Superior and outlying areas, commercial kitchen, public showers, restrooms, hold weddings & funerals, $500,000 business council grant Grandmother’s

As a result Superior declined from a population of 1,580 in 1920 to a population of only 241 in 1930, leaving vacant properties.

In the coal booms of the 20s the U.P.R.R. Company built several hundred houses, constructing neighborhoods during the influx of new workers. All that are left of the neighborhoods are the roads, and the house foundations have been leveled. As coal miners in Superior joined the armed forces, there was high availability for new mining jobs. Families moved from all over the US to be housed in boxcar camps.

Superior obtains its water from 3 wells, and as of 2020 the water is safe to drink. Dirty, inky water has been sourced from the mines and water still travels through iron pipes. Wyoming has a very arid climate and water must be used thoughtfully.

DEPRESSION

OTHER STATES’ ENERGY DEMANDS

My Sweetheart’s The Mule in the Mine (Traditional)

My sweetheart’s the mule in the mine Down below, where the sun never shine And all day I just sit And I chew and I spit All over my sweetheart’s behin’.

My sweetheart’s the mule in the mine I drive her without an-y line On the bumper I sit, And I chew and I spit All over my sweetheart’s behin’.

BRIDGER POWER PLANT CONSTRUCTION

RELIANCE ON COAL TO

ENVIRONMENTAL REGULATIONS

61

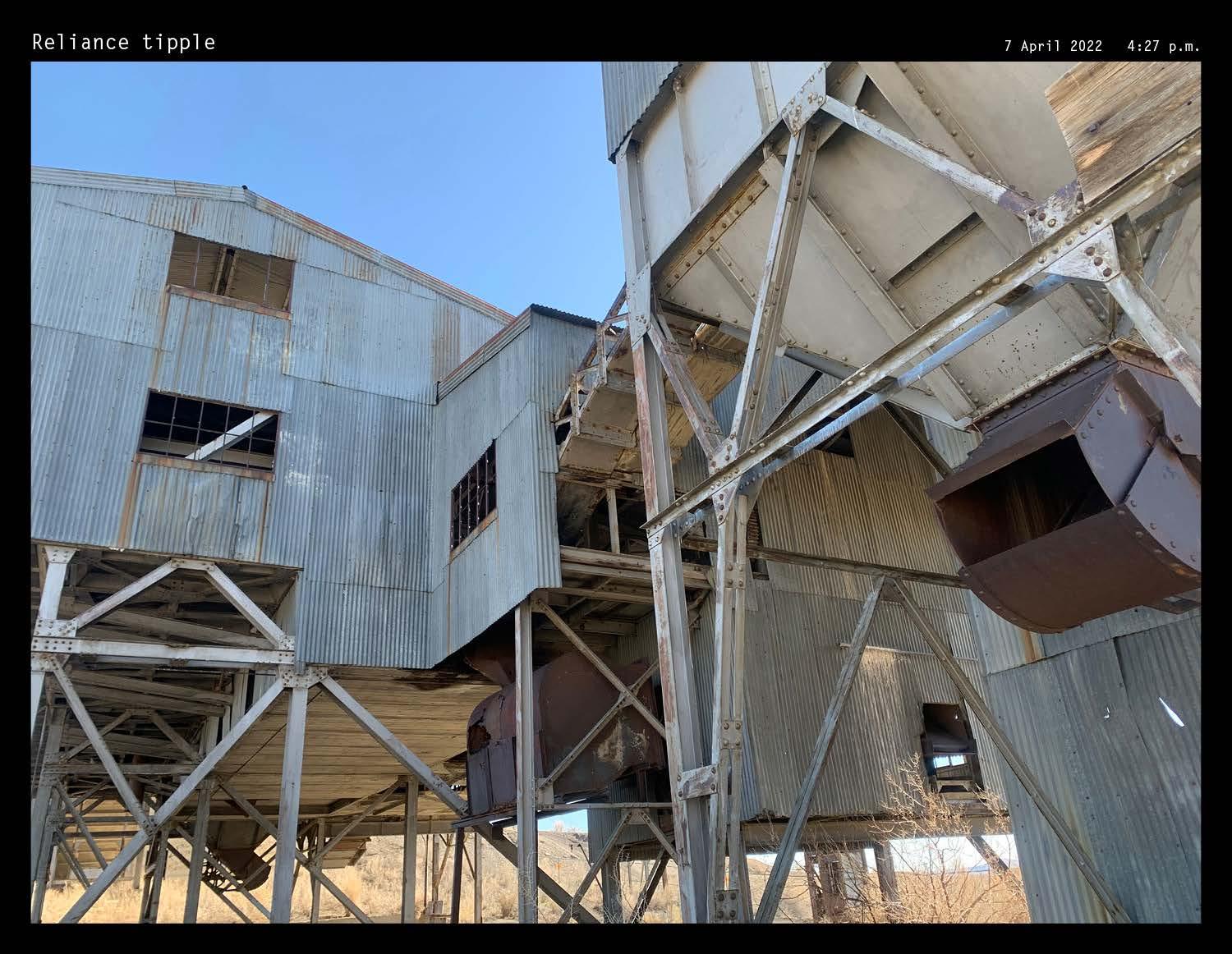

Miners from “D” Mine, 1943 Unidentified UPRR mine to an increase in population during the influx of new workers during WWII, the Company made homes for residents using railroad box cars, placed on foundations two combined for larger homes. 12’x16’ kitchen and a big bedroom. We added that porch, Francis’s little bedroom.” moved up there.” right after I had my sister and I were comic books breath. I had to catch my there, was put our own right. We always I had to bill for the said ‘no “Grandpa used to work in C-mine over there. He used to walk from A camp all the way across the hill up to go to work.” B-hill. There aren’t any houses up there anymore.” that hill, but it’s gone right now.” “This used to be all empty. What a mess it is.” Leosco family house Leosco prize-winning Victory Garden Houses and trailer homes on the hill 00:00; 0mi 1 THE MINES Pre-bust 2022 02:45; 0ft 04:05; 0ft 04:23; 0ft Marskey Park with baseball diamond and historic tipple in the background Nearby church 2 “It’s a miner’s cap.” “Wacha have on your head there?” “What’d ya wear it for?” “In the mine.” “Ya had to wear it everyday?” “Sure, it kept me from bustin’ my head.” 3 Novak Family Video: 1993 The aftermath of a coal mine With the dieselization of the U.P.R.R after WWII, all mines but one were closed. People left the town for Rock Springs and businesses were deserted. It soon began to resemble a “Ghost Town.” Jim Bridger Power Plant, now being shut down The town enjoyed a short revival in the ‘70s during the construction of the Bridger Power Plant and Mine. Several mobile home parks were built to house the workers, and many lived in tents next to the site. When construction finished in ‘75, Superior once again became a “Ghost Town.” The D.O. Clark Mine trams, the only mine in production after the WWII bust The old tipple in Superior still stands as a testament to the town’s coal mining history.

Workers still commute from Superior to Rock Springs for work at the power plant and other jobs. 00:28; .25mi 03:26; 3mi 03:50; 3mi Annual mud bog festival every June, tickets $7 Great Great Grandmother’s house was here THE GREAT

Many mines in Sweetwater County closed due to the lower coal demand and the mines in Superior began to exhaust their reserves. The dieselization of trains and machinery after WWII led to the closure of all but one mine and a rapid decrease in the town’s population.

Old Miner’s Working Song:

POWER TRAINS

Due to the high cost of coal in the late 70s and demand for electricity, the coal-powered Bridger Power Plant construction led to a rapid influx of workers to Superior. The Pacific Northwests depends on workers from Superior for their energy. Likewise, Superior jobs depend on other states’ energy demands.

The Pacific Northwest is ending its reliance on coal and encouraging renewables, prompting Wyoming to keep up with this new demand. Coal power plants, like the Bridger plant, are now being shut down. NEW

V Superior and Rock Springs Historical Archive

62

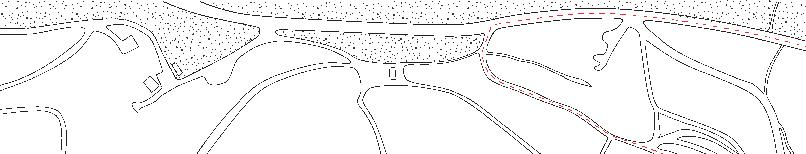

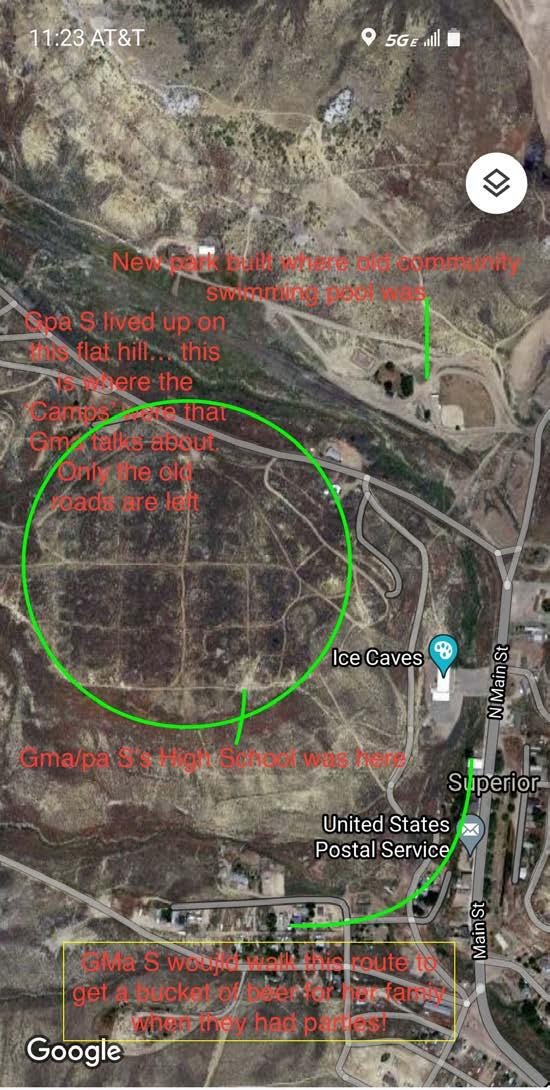

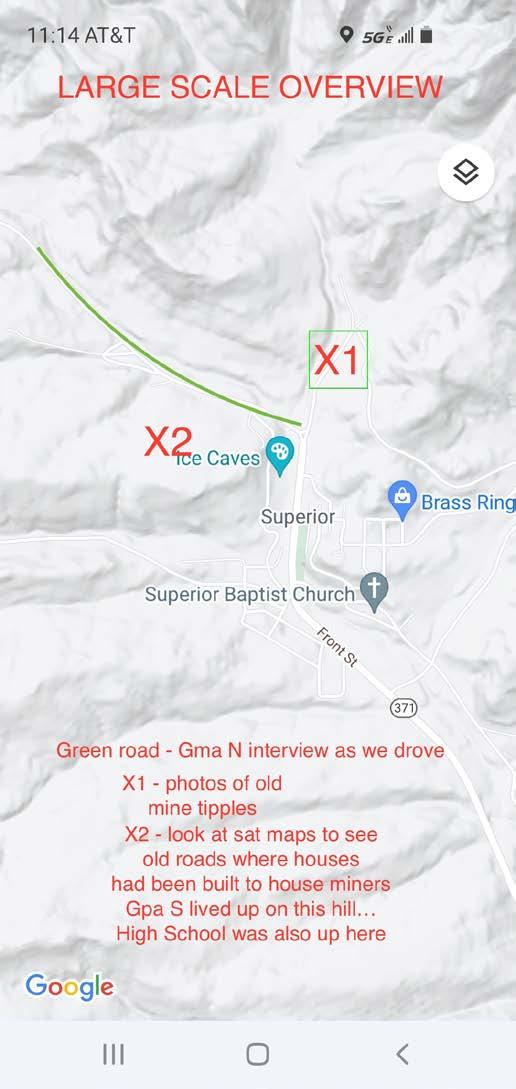

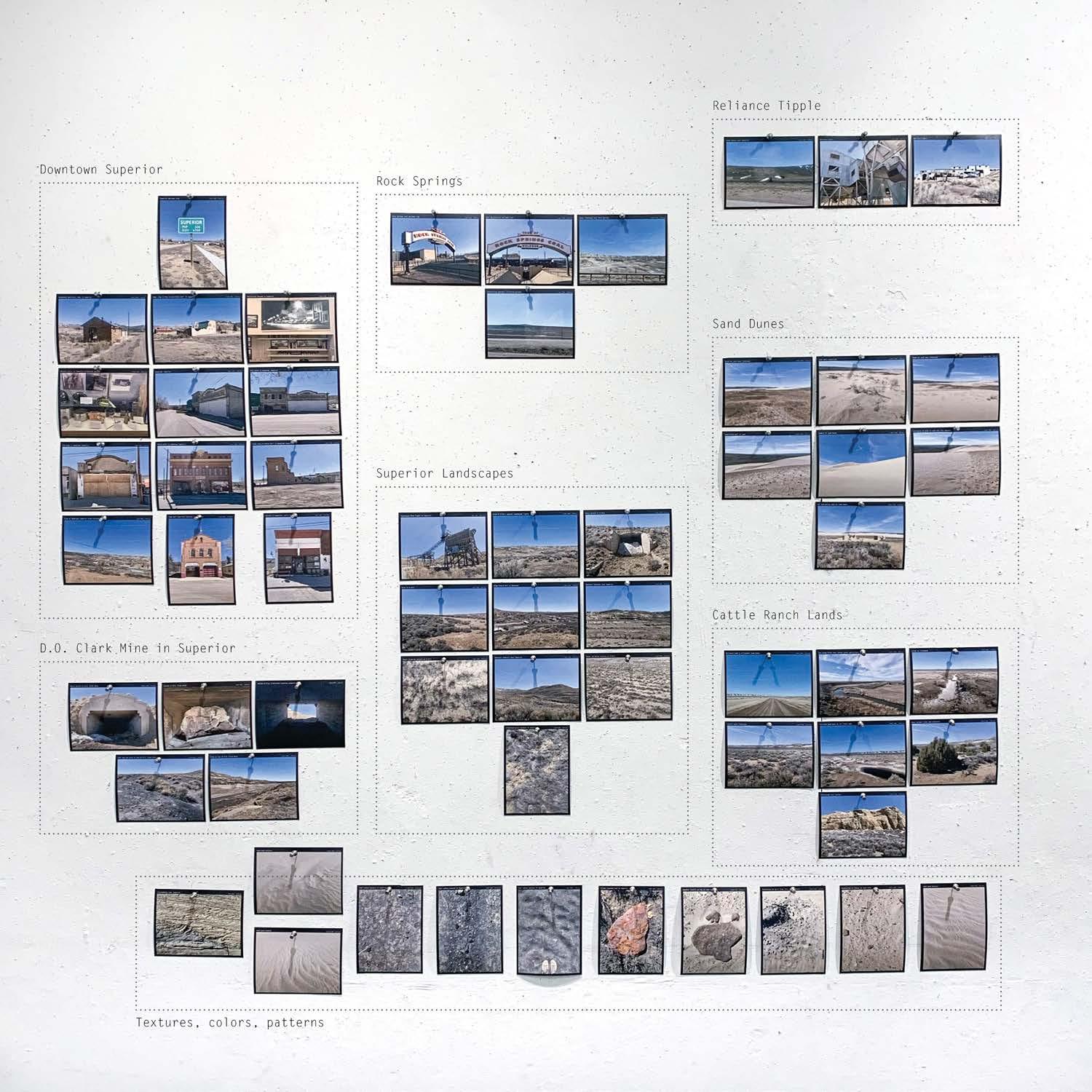

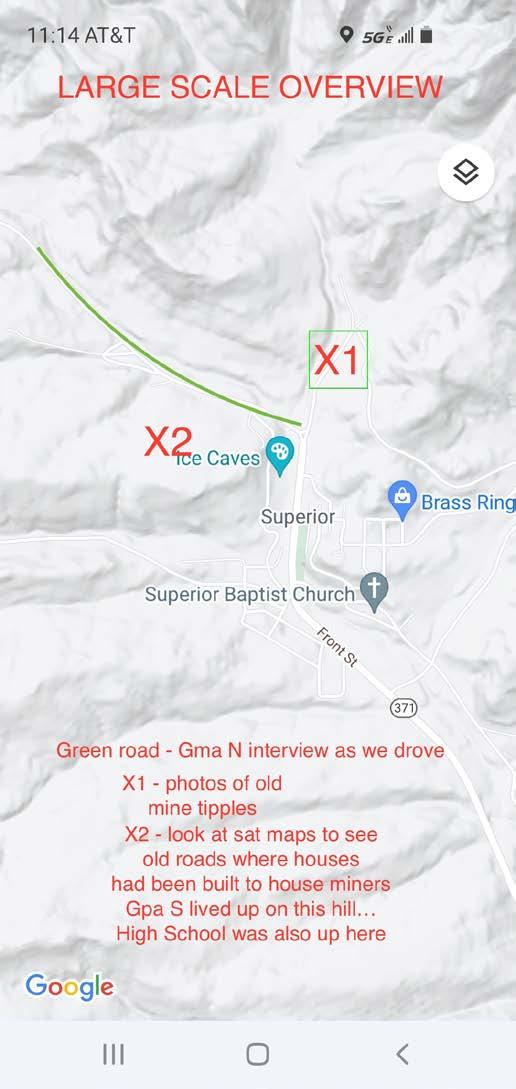

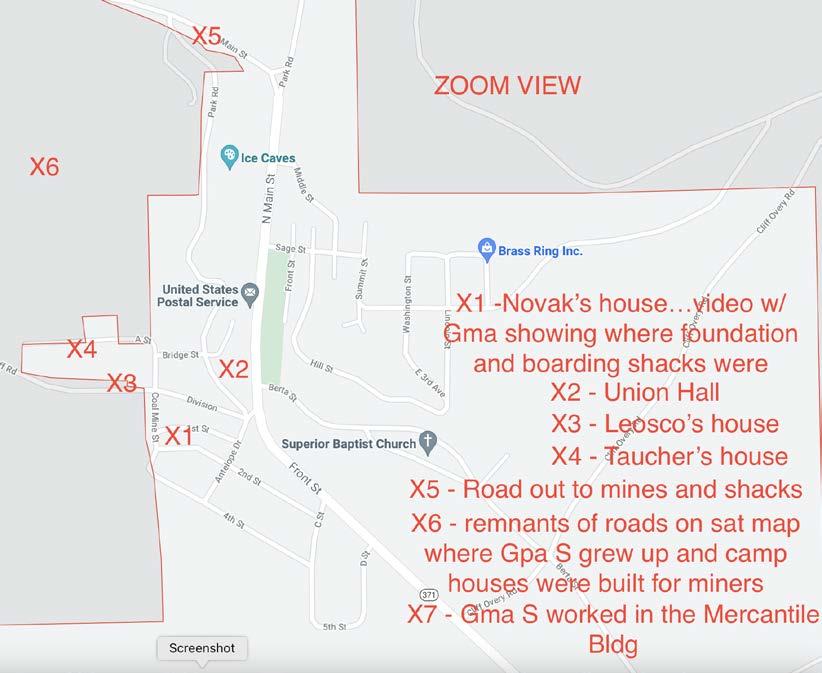

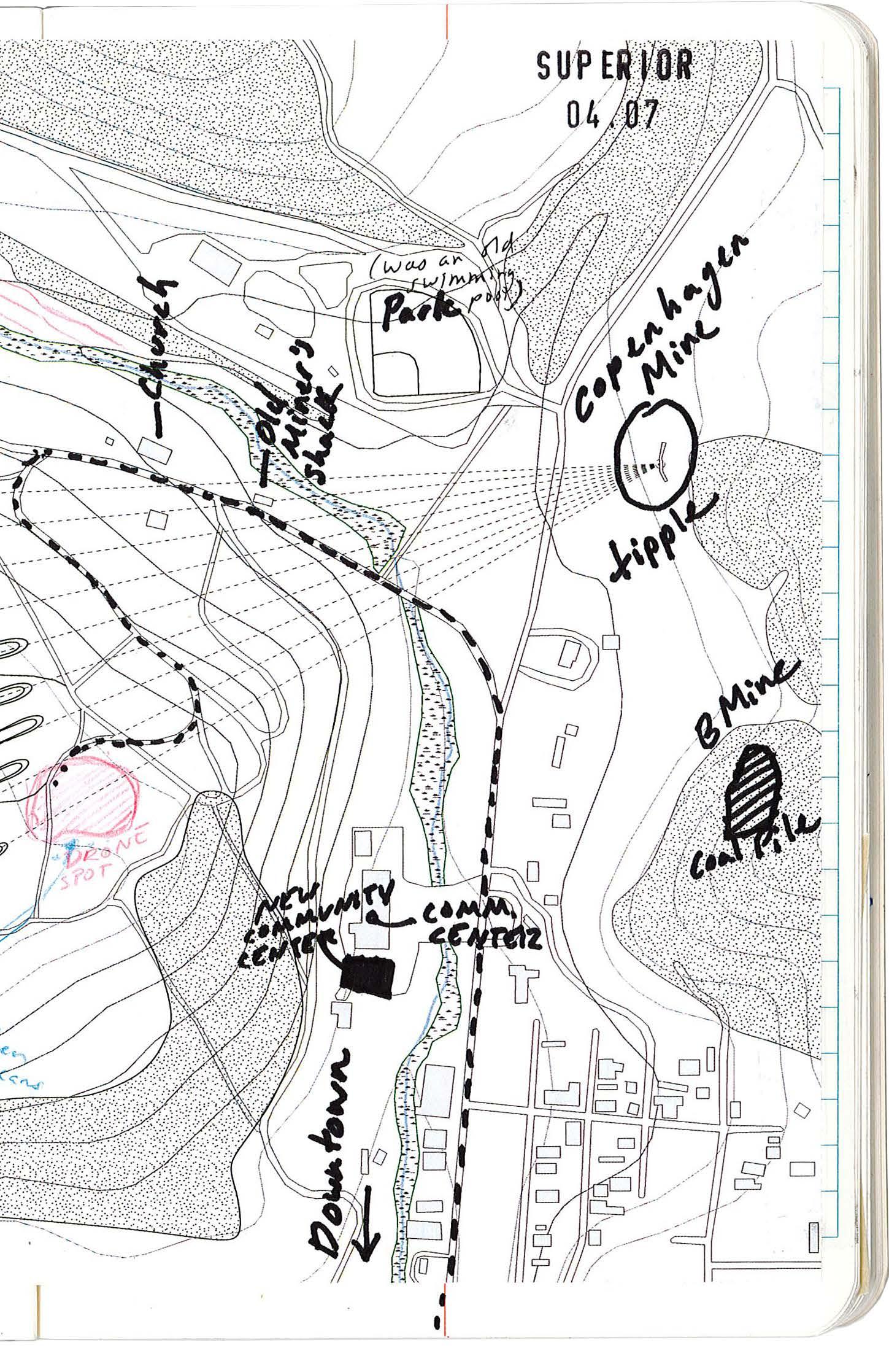

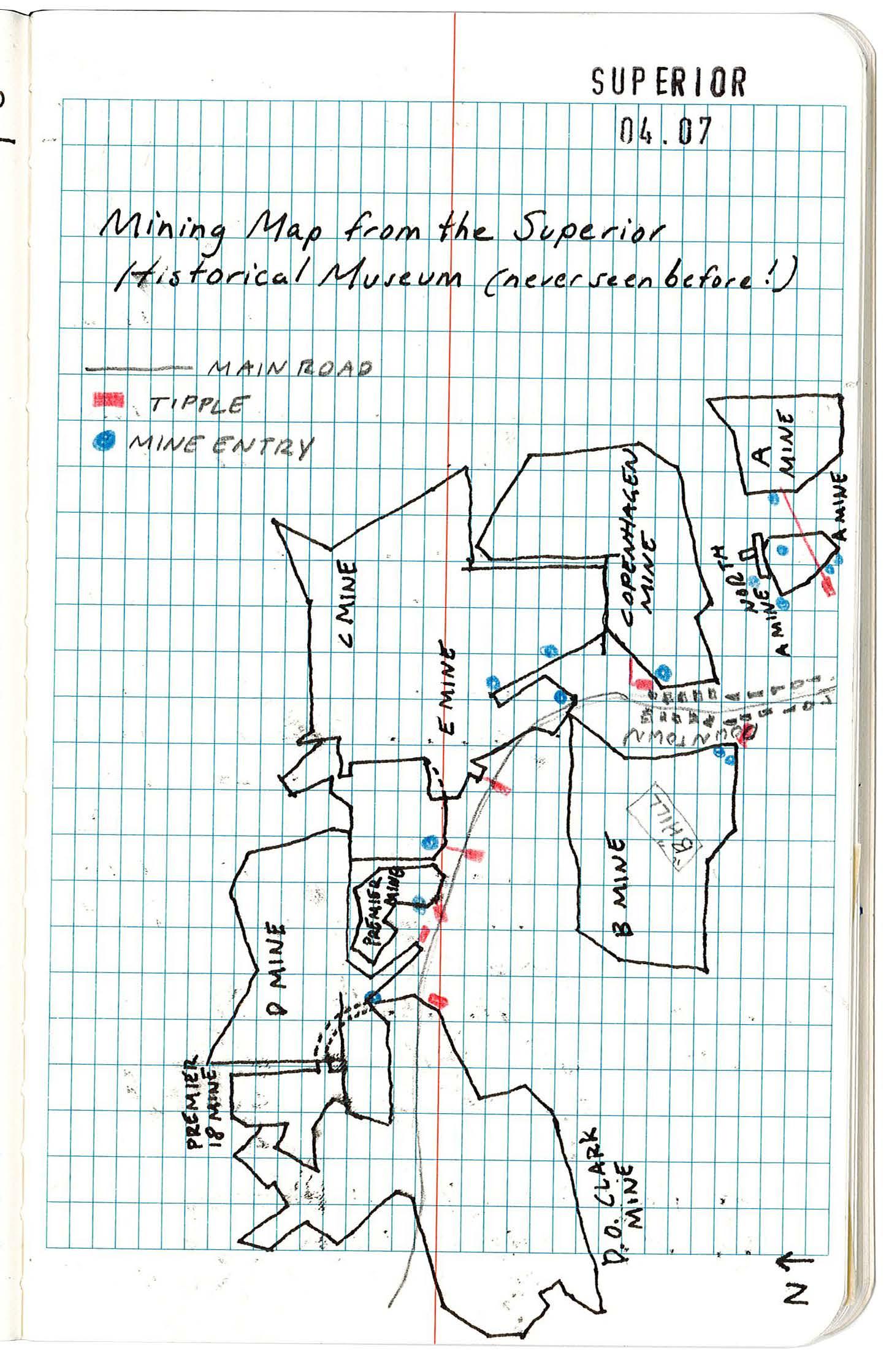

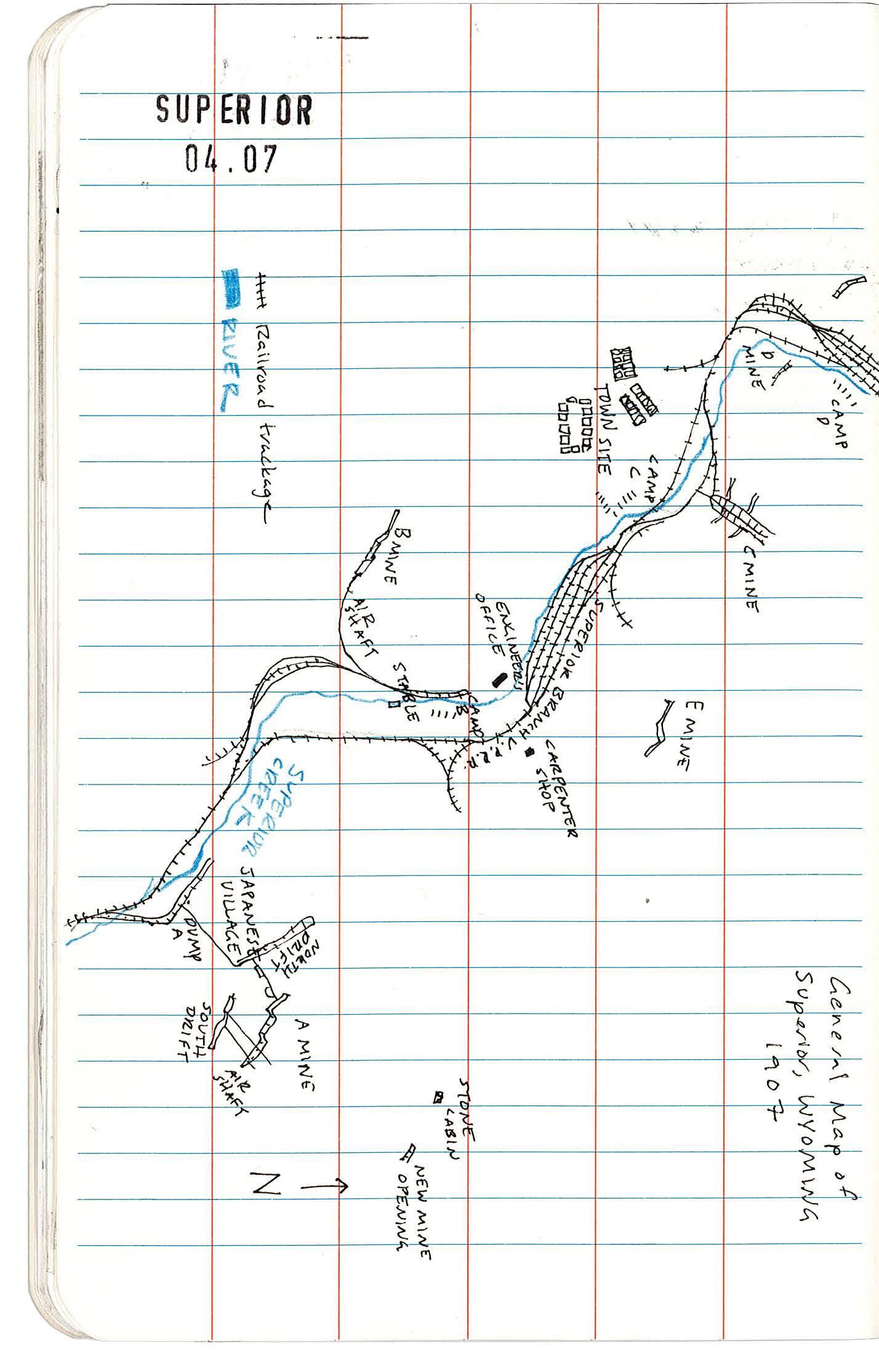

NOTATIONAL MAPS OF MEMORIES OF SUPERIOR DRAWN BY MARILYN MEEK

Information on Superior was difficult to come by in the early days of research. My mother, Marilyn Meek, helped provide orientation to the town she frequented as a child, and most recently ten years ago, by creating notational maps to pinpoint my family’s roots and what has since disappeared.

63 V Superior and Rock Springs Historical Archive

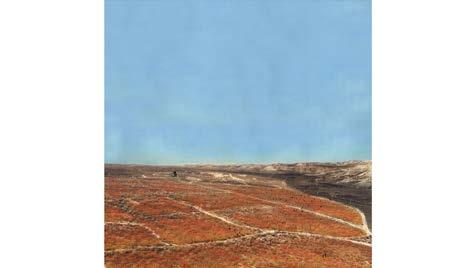

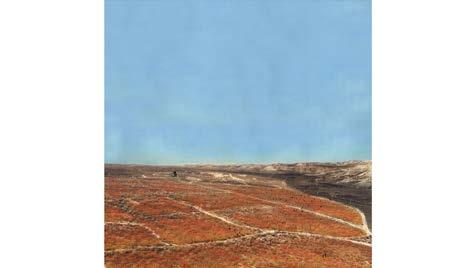

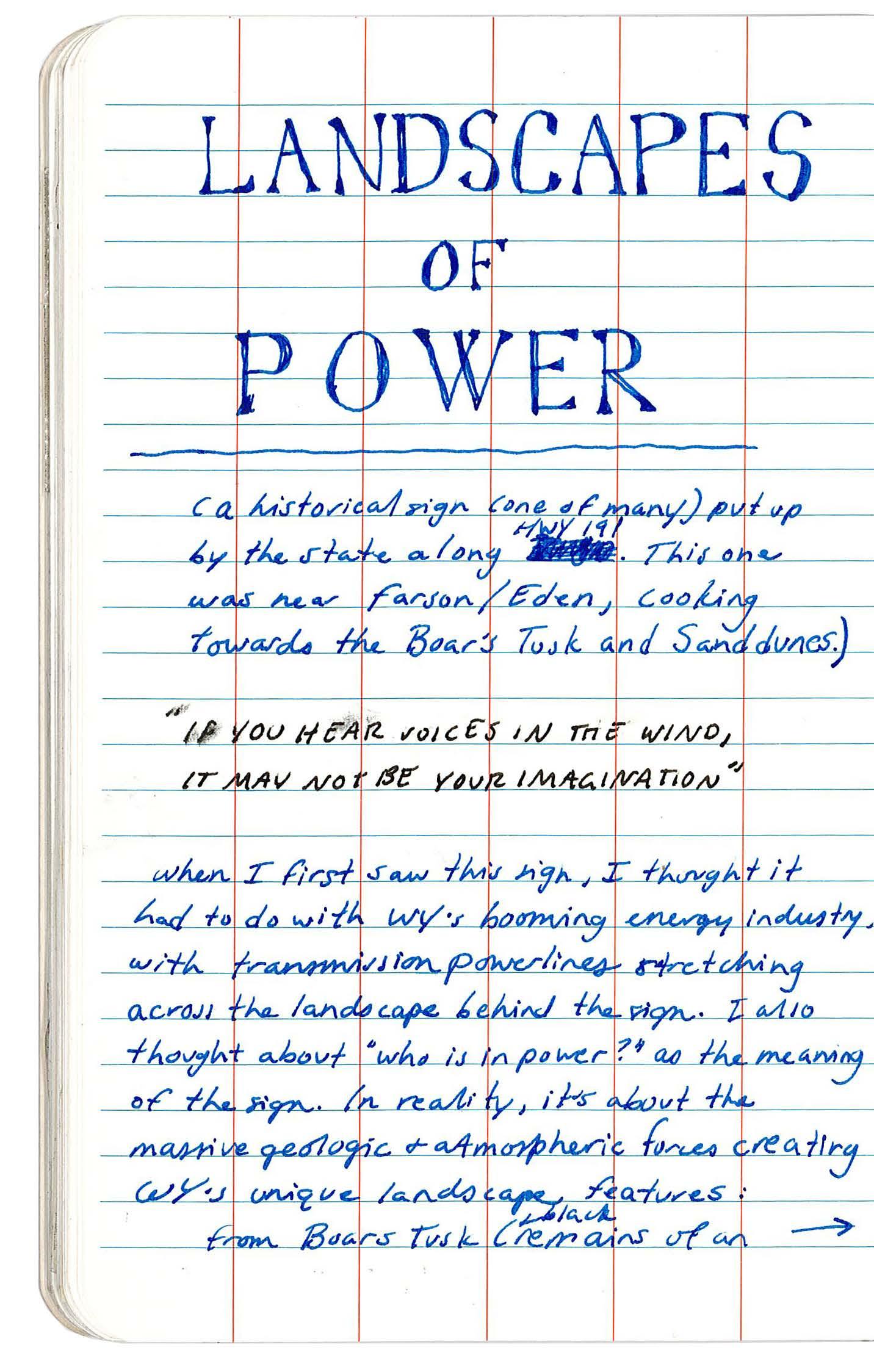

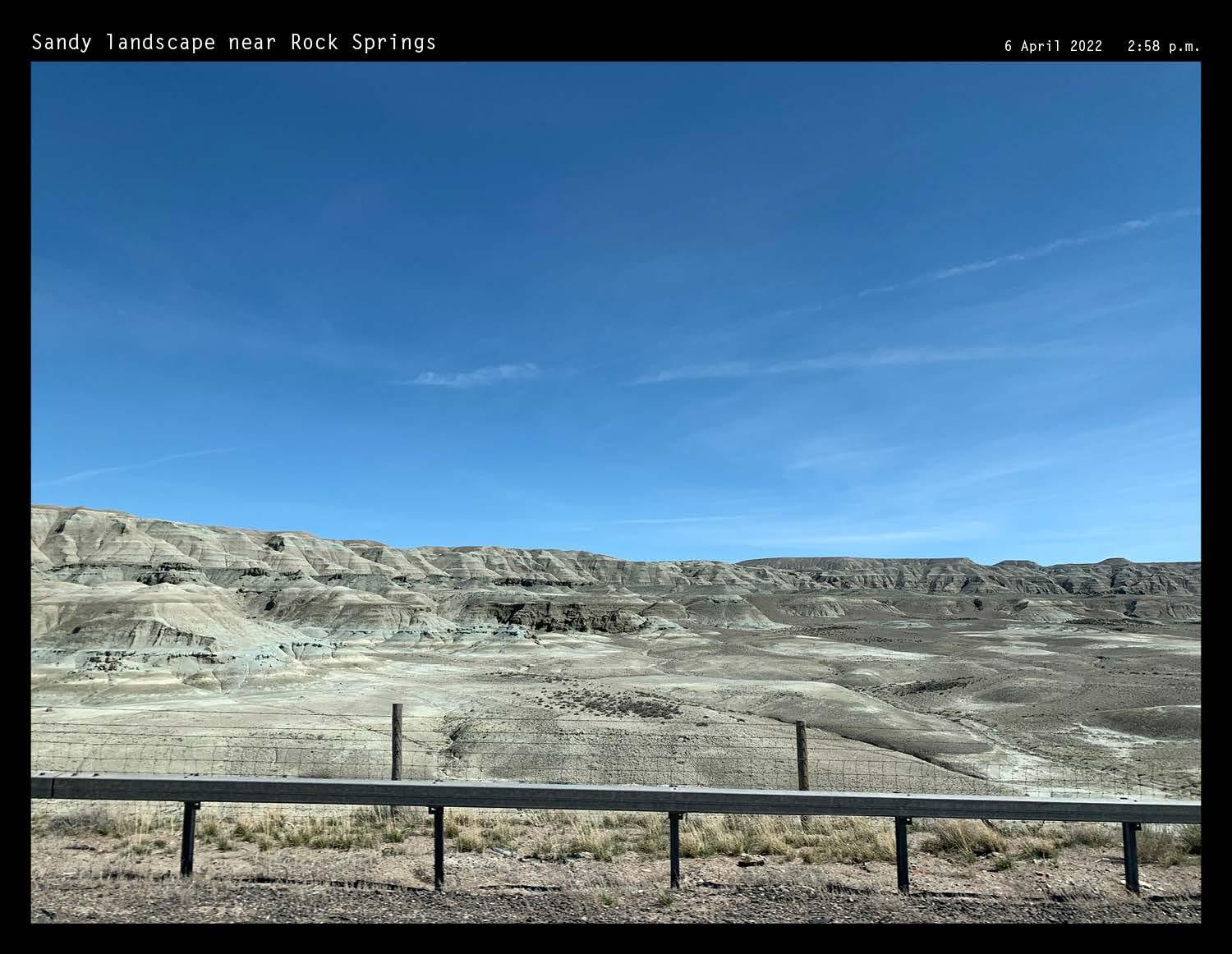

Recreational and extractive landscapes intertwine in Wyoming’s Red Desert.

64

VI

CARTOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE EXTRACTIVE PROCESSES

A Landscape of Extraction and Recreation

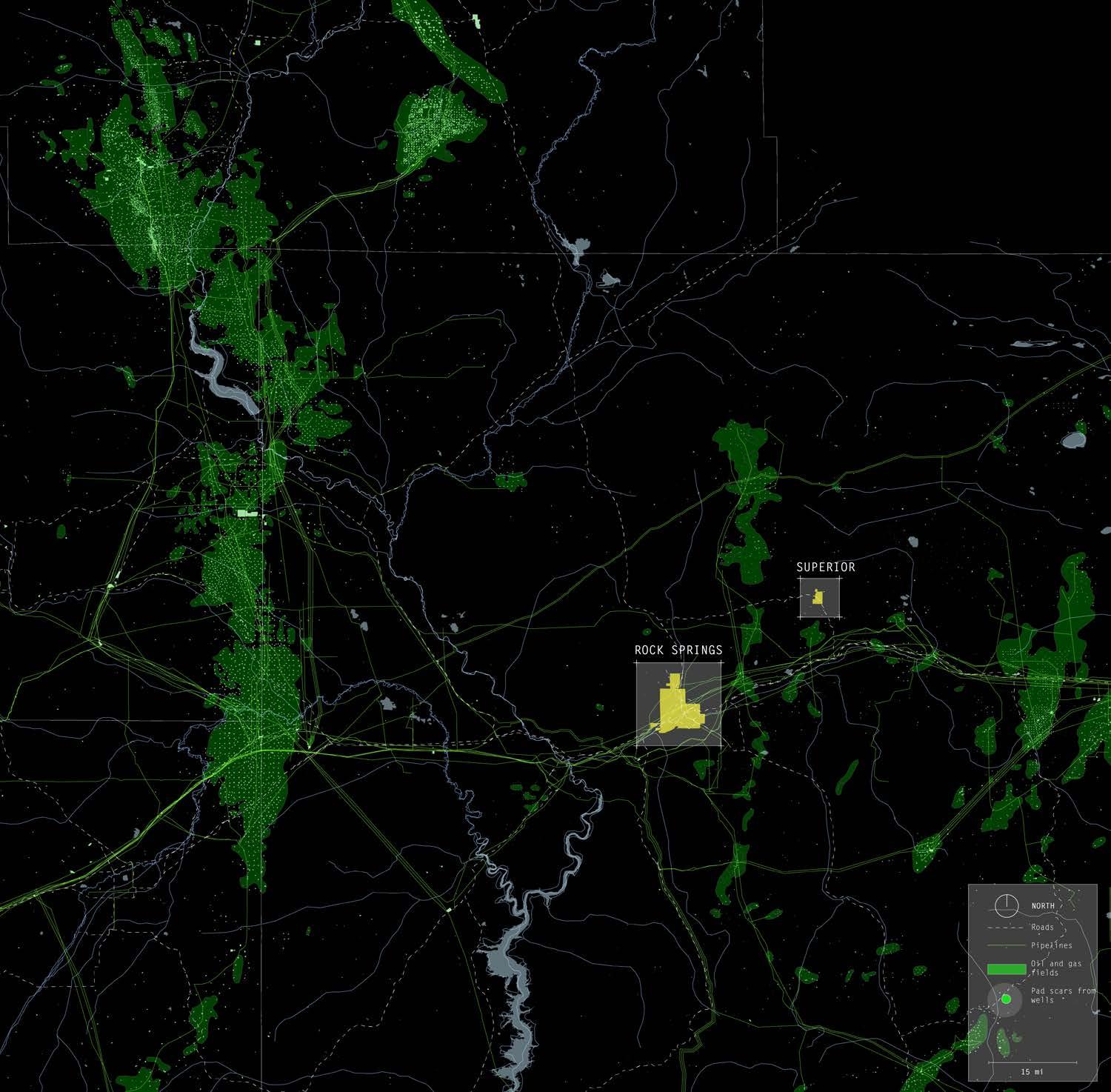

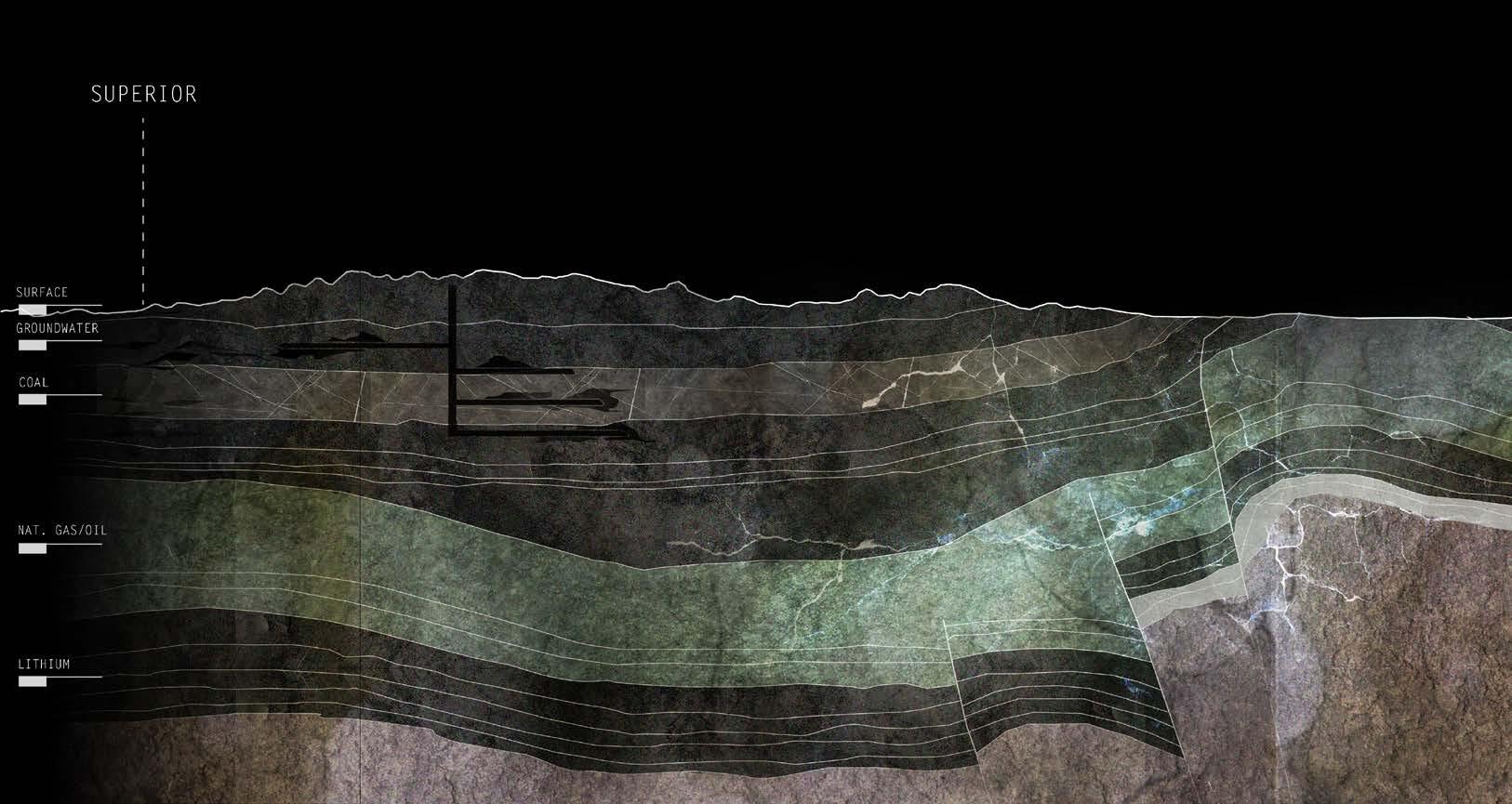

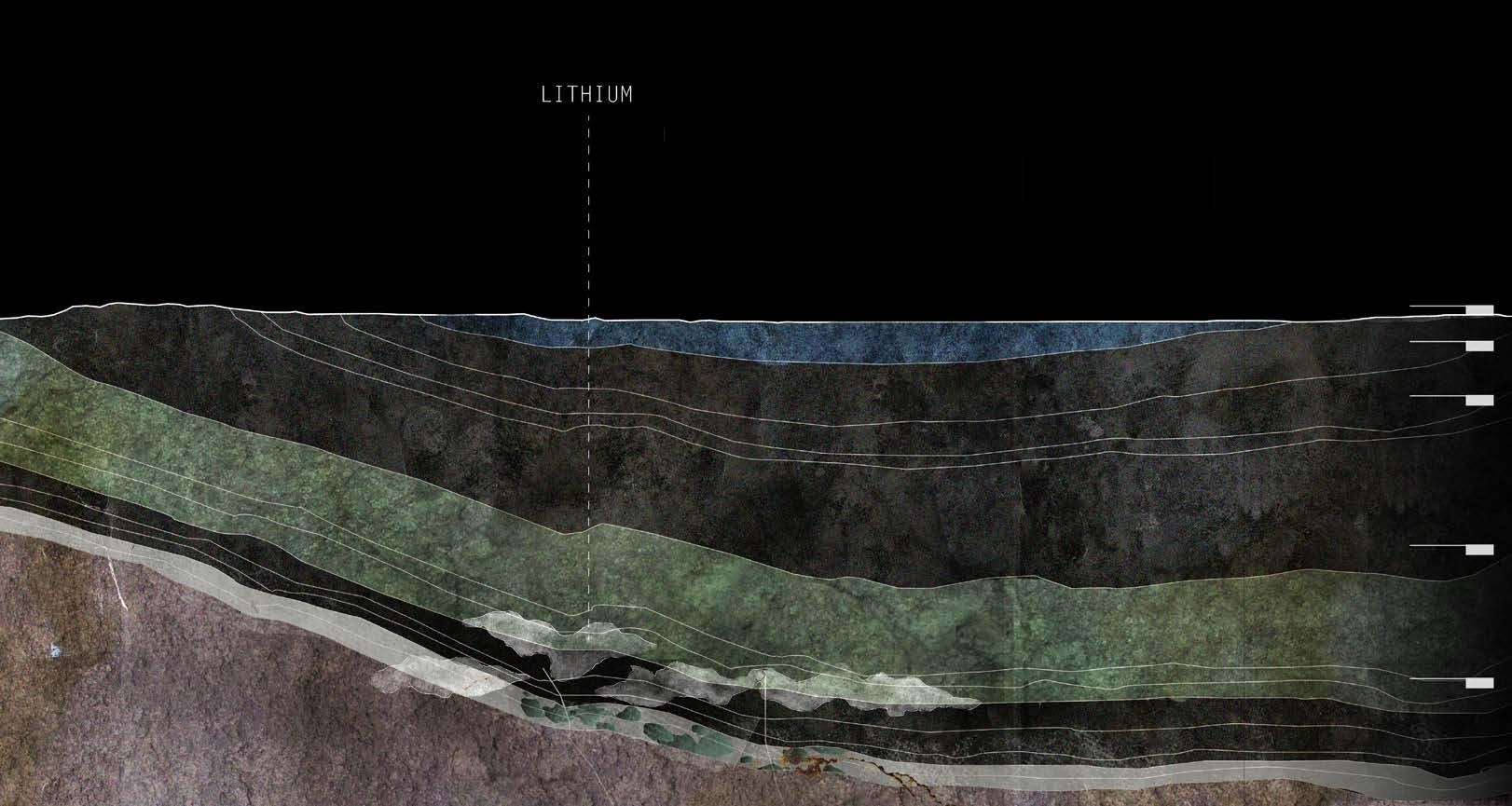

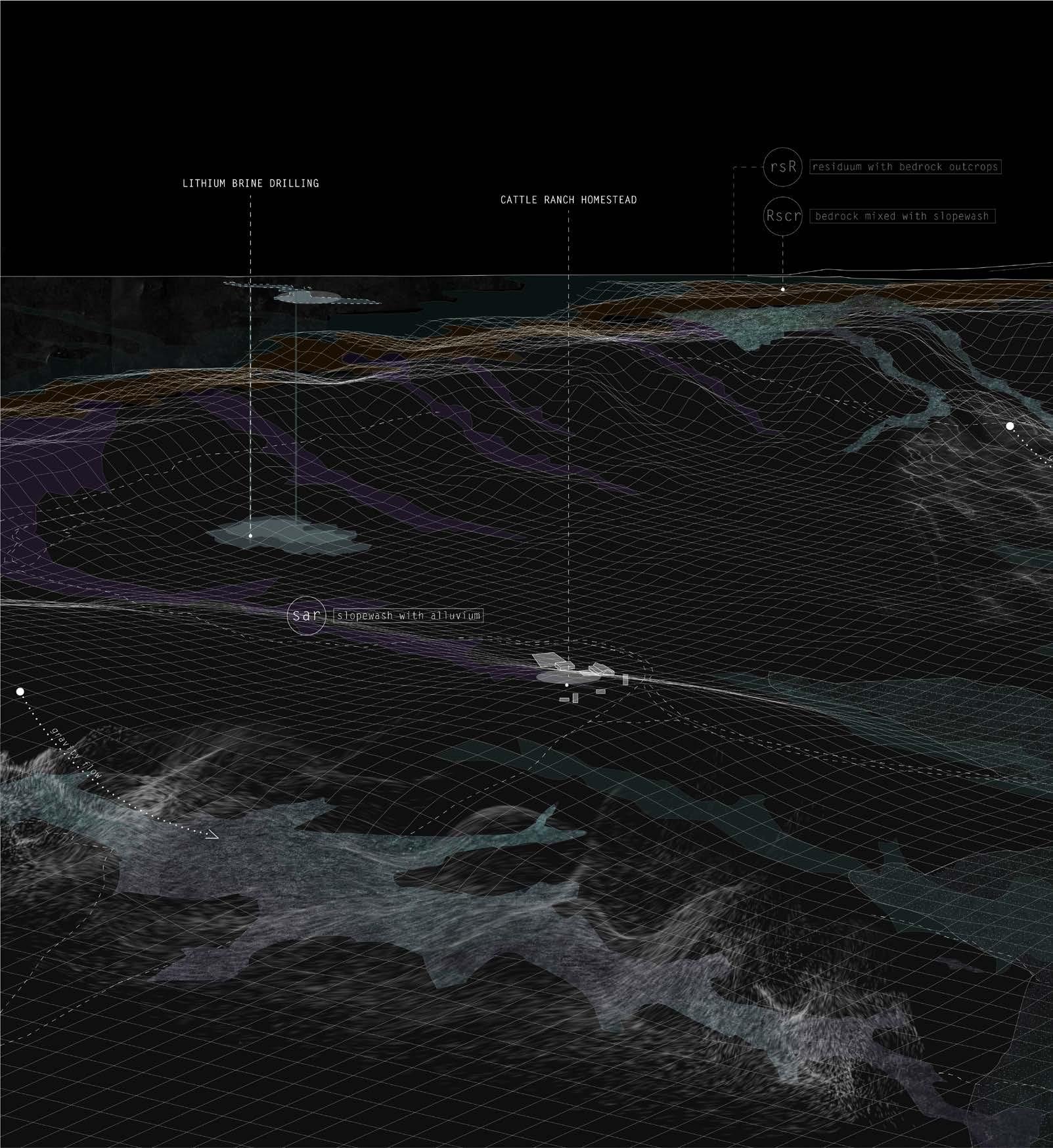

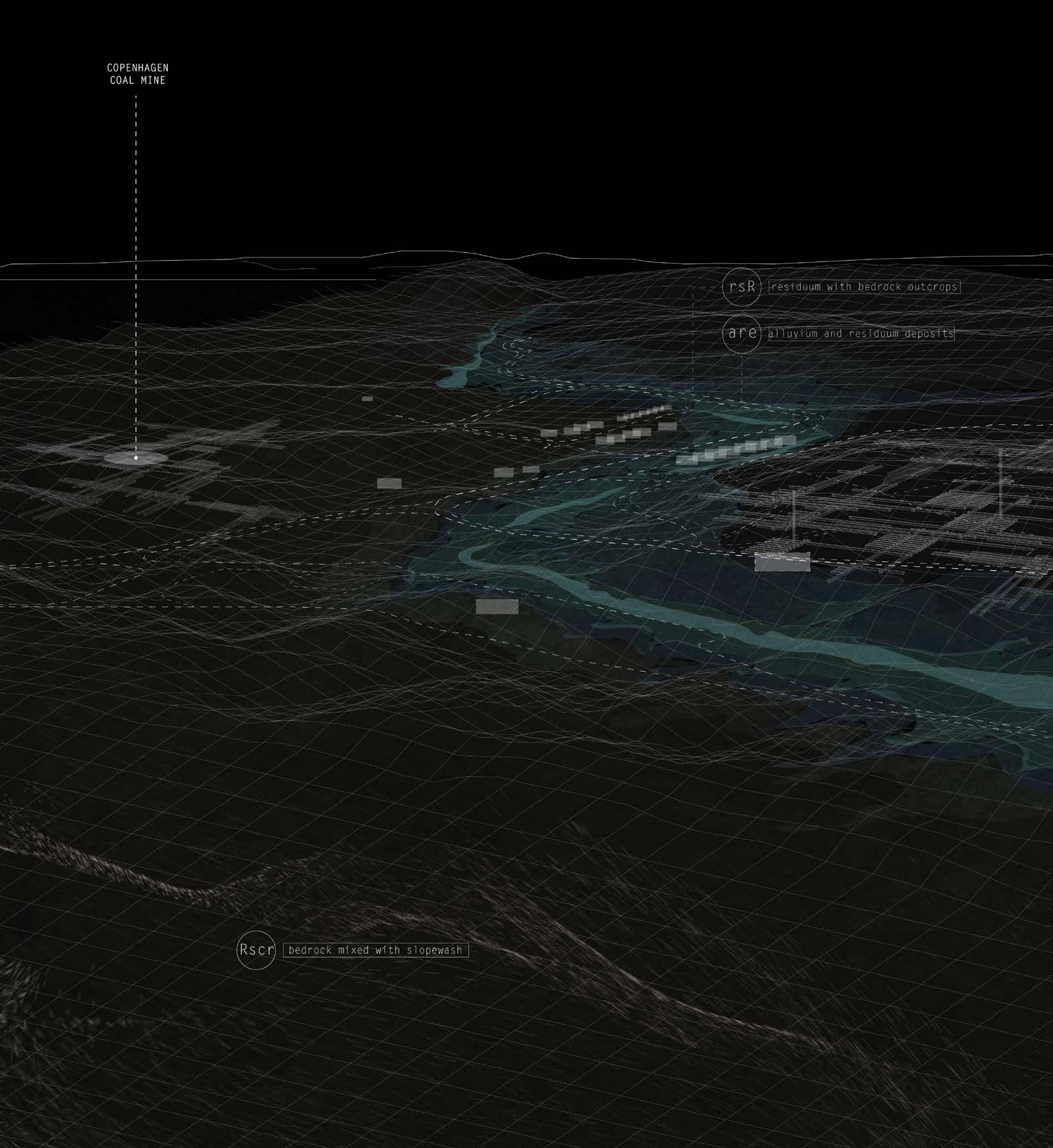

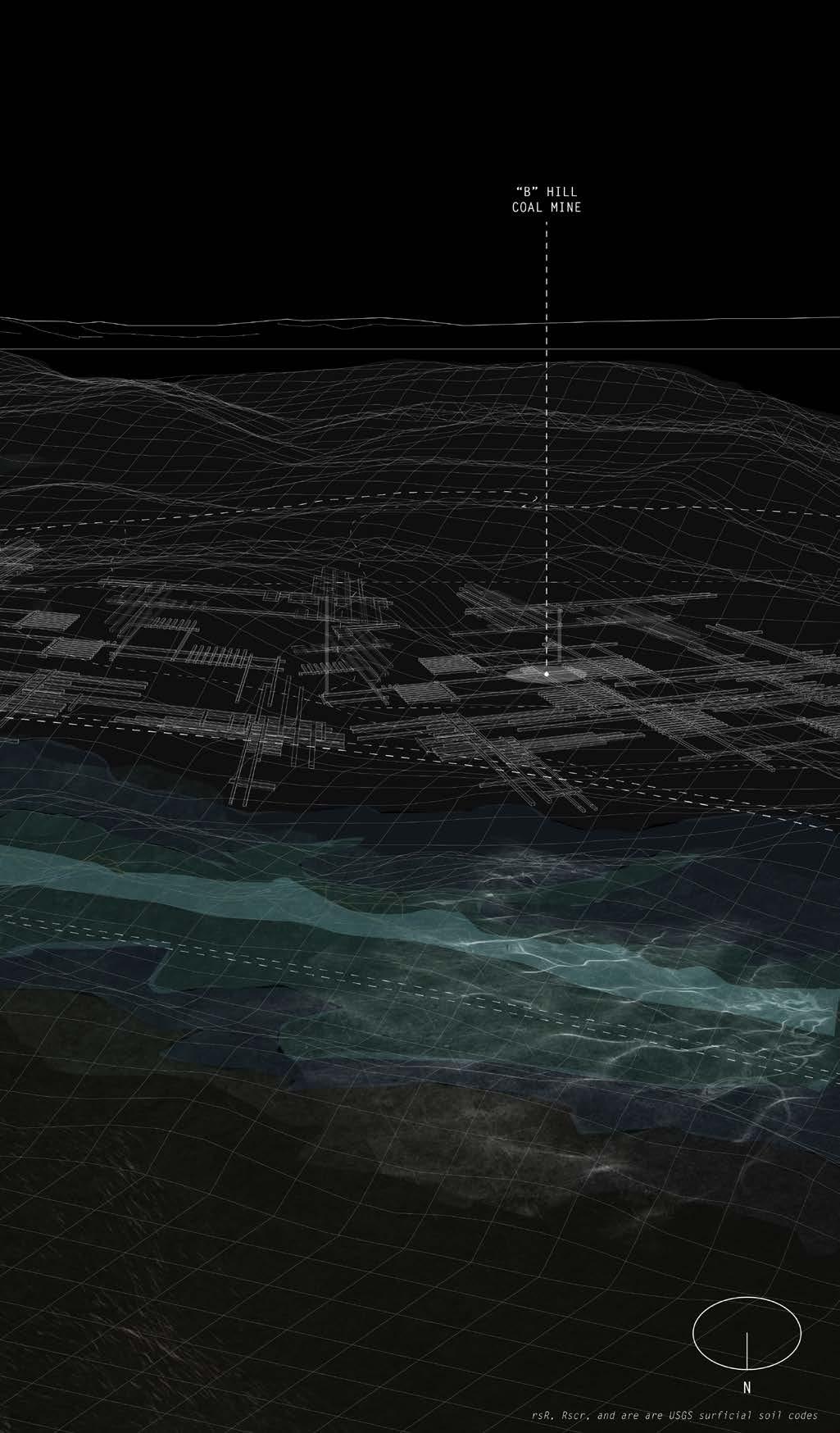

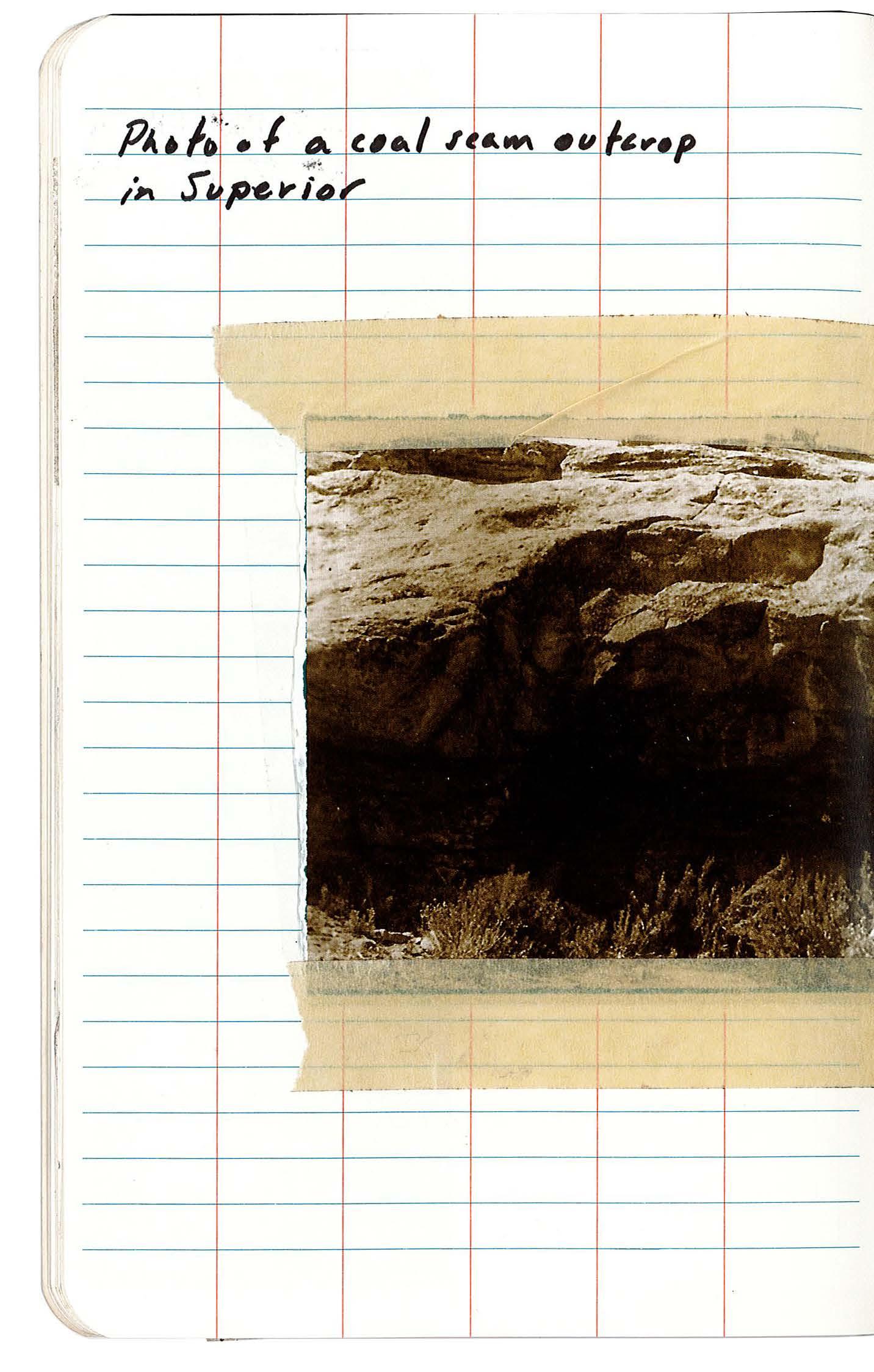

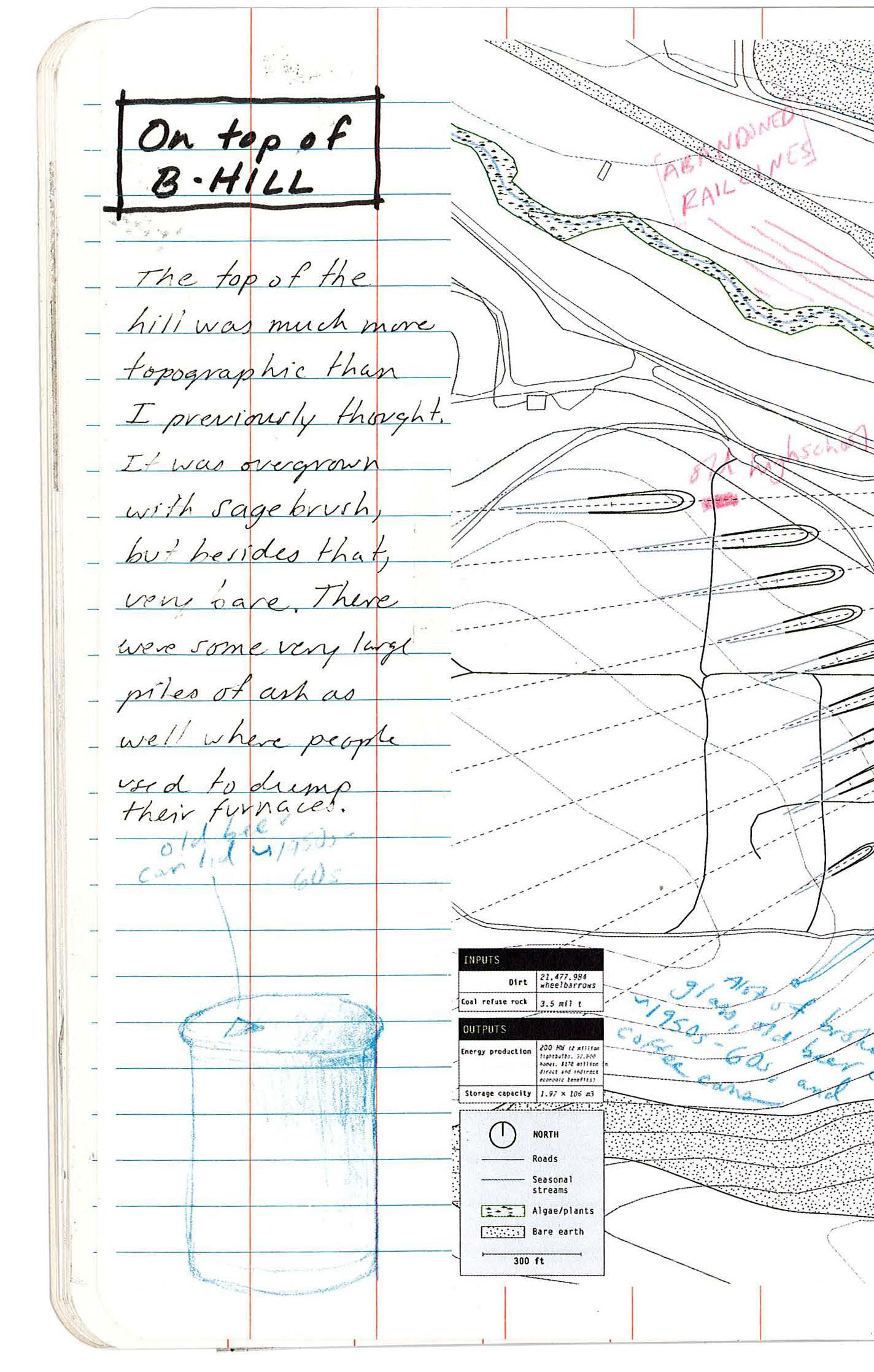

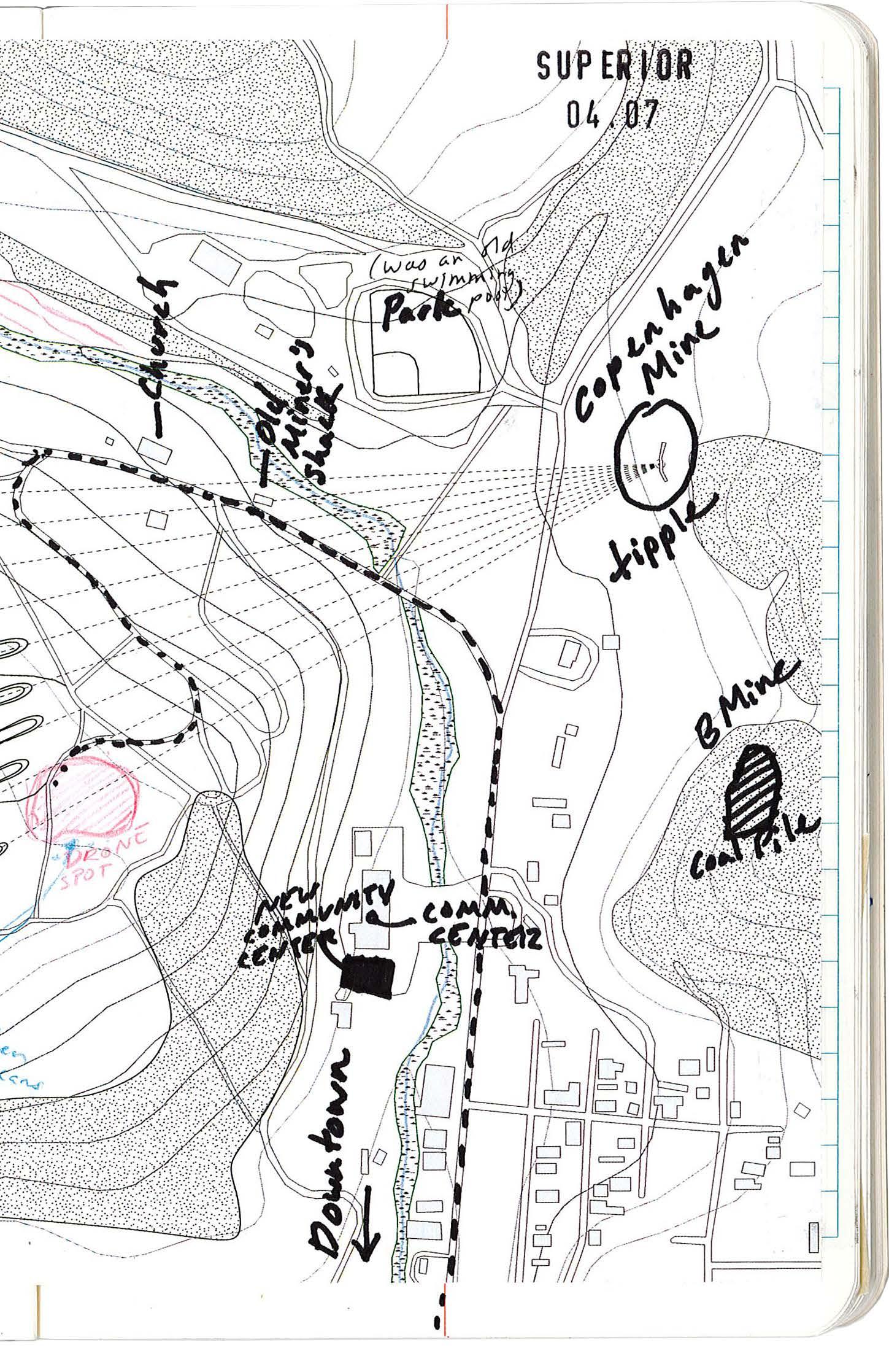

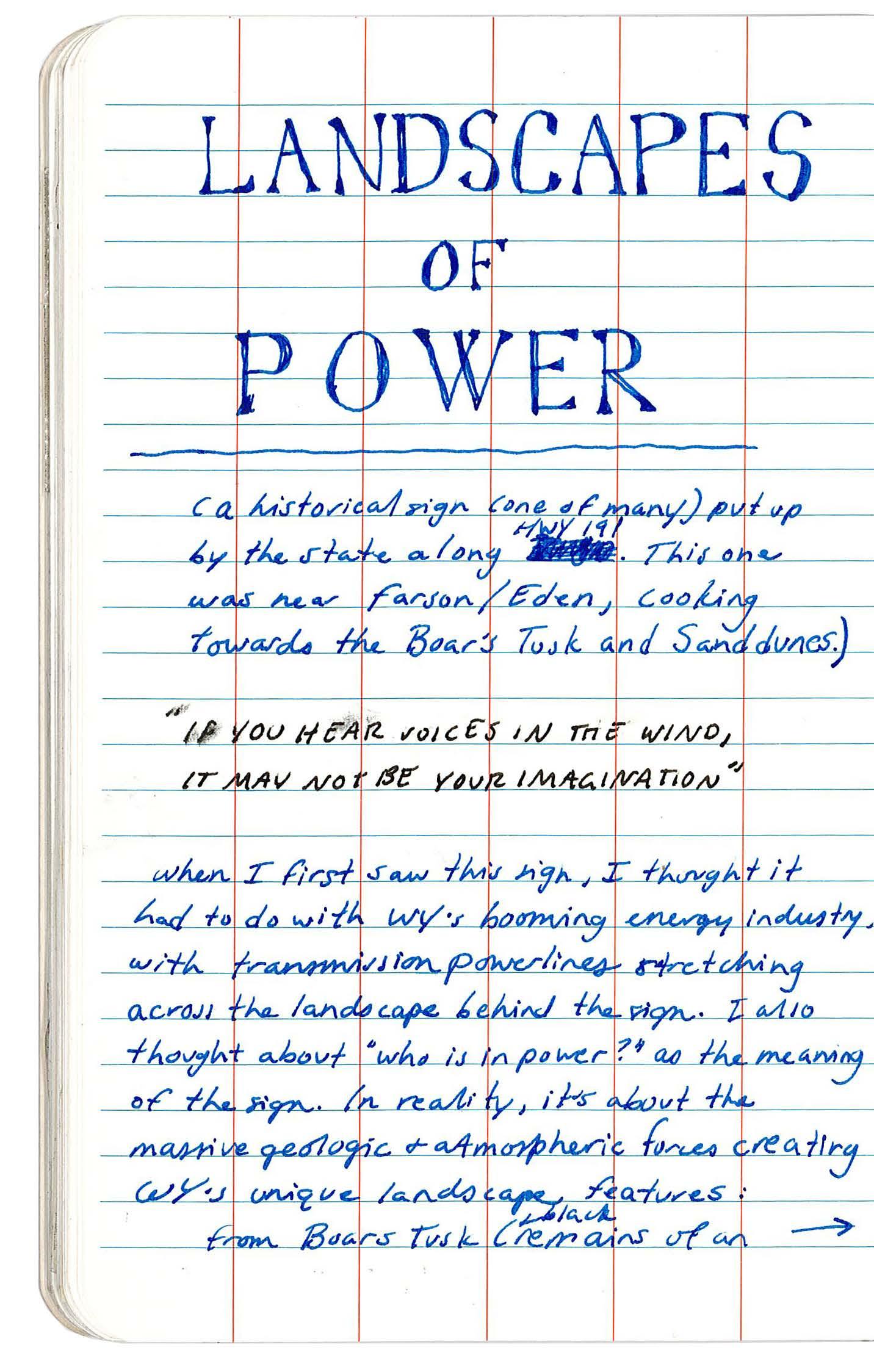

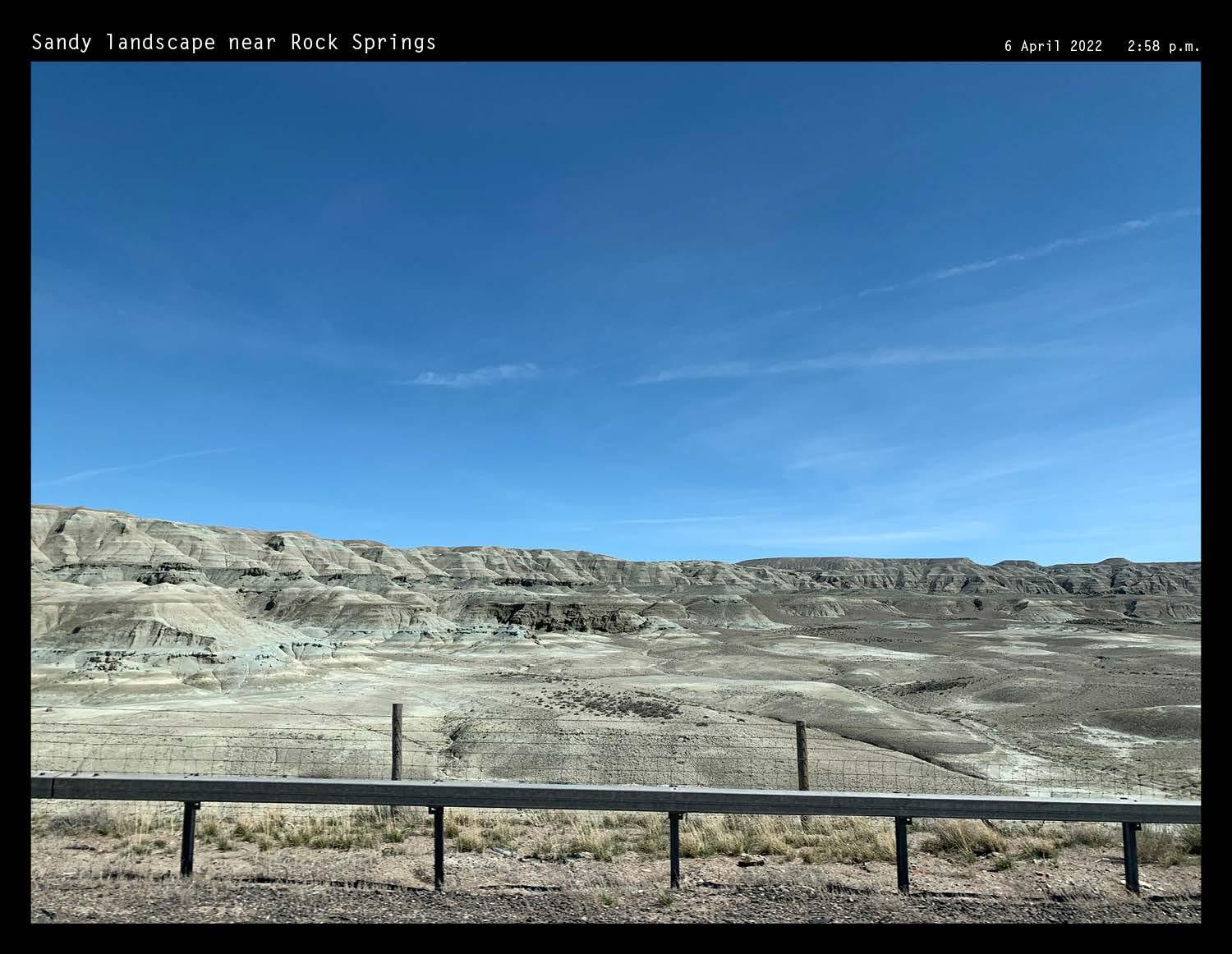

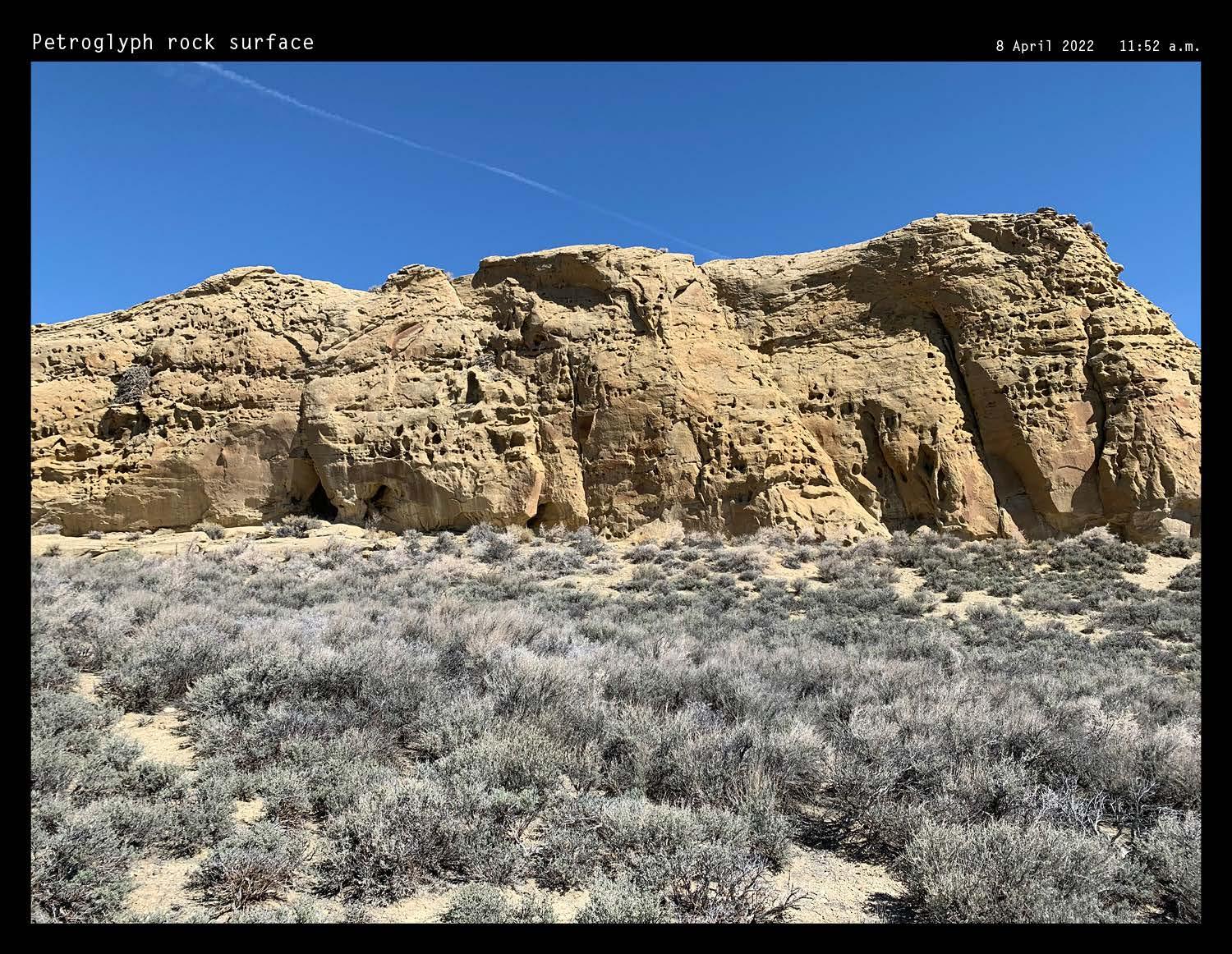

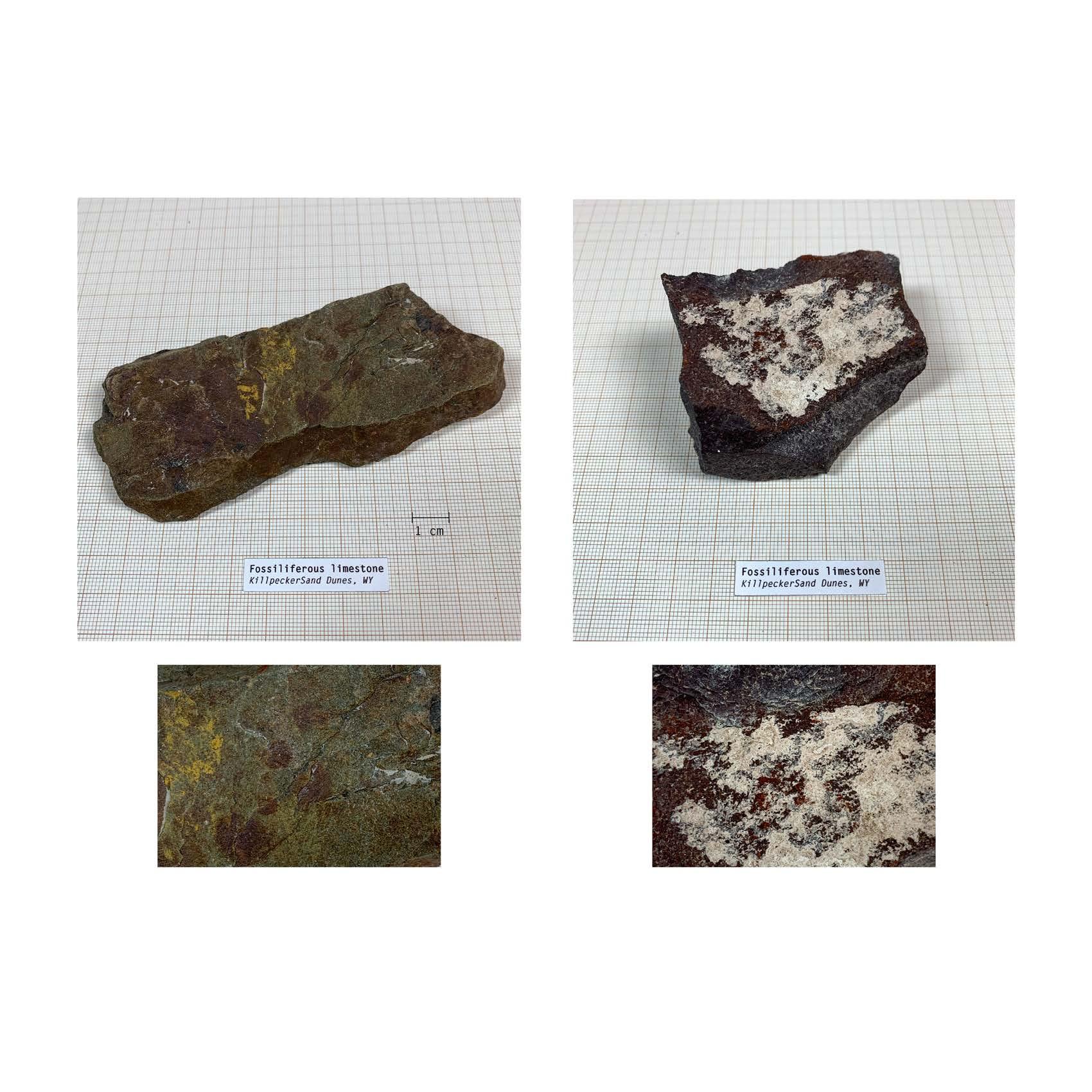

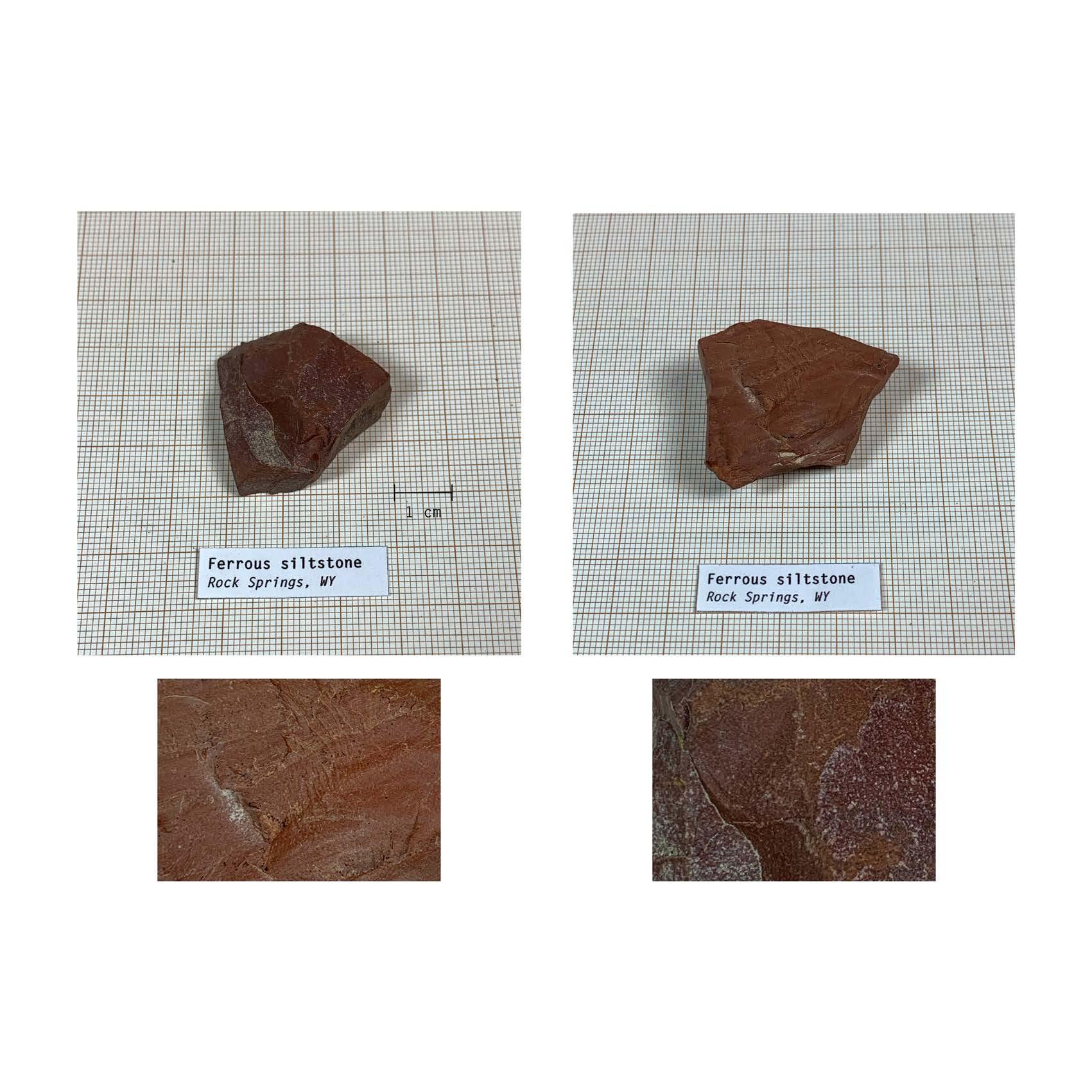

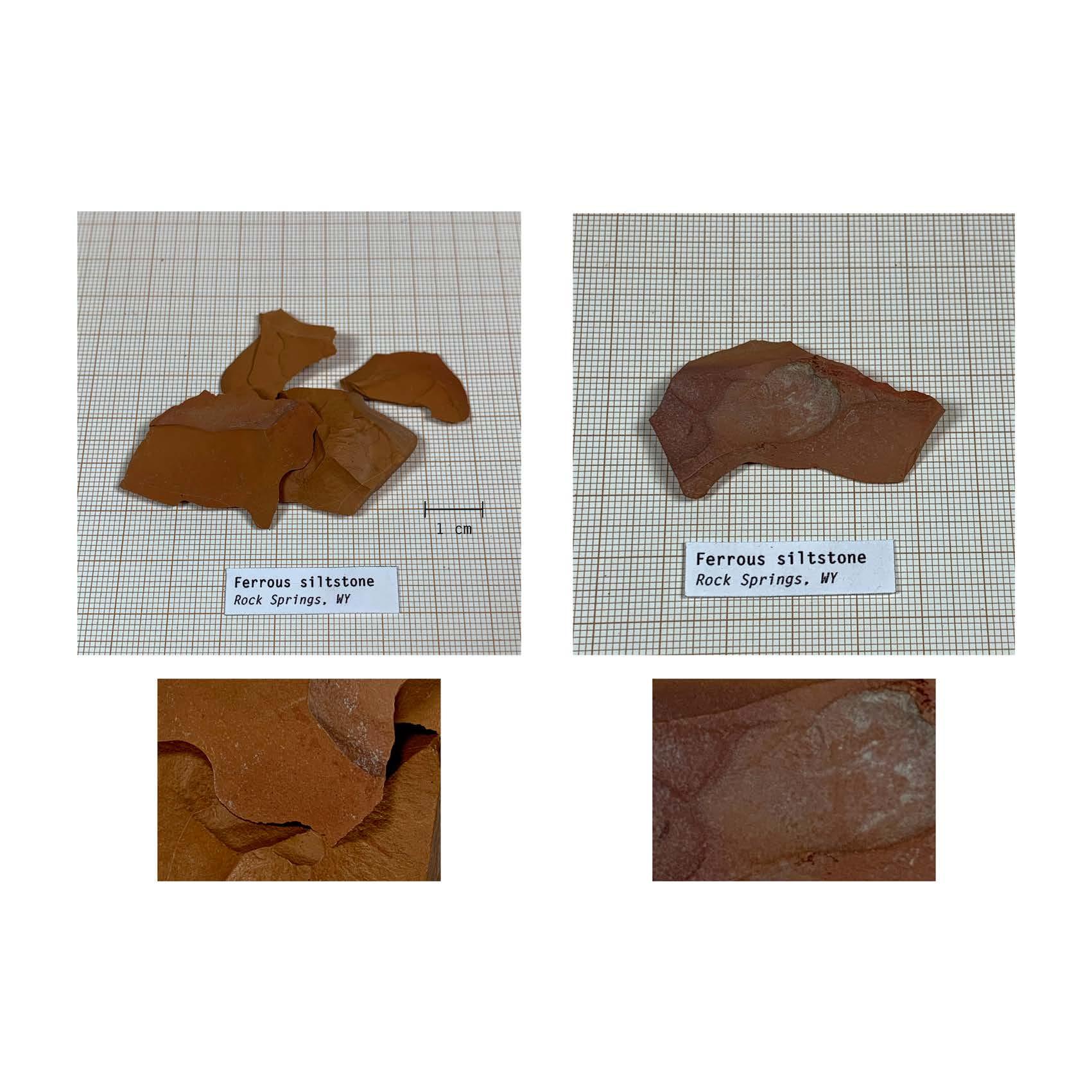

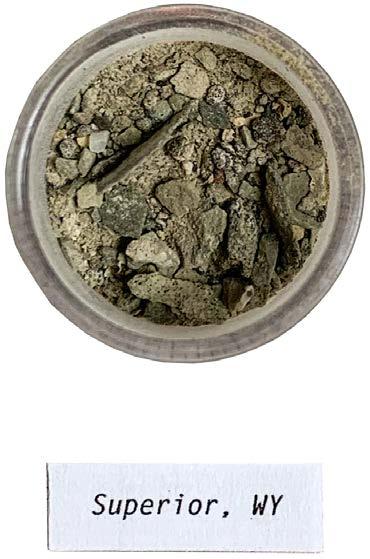

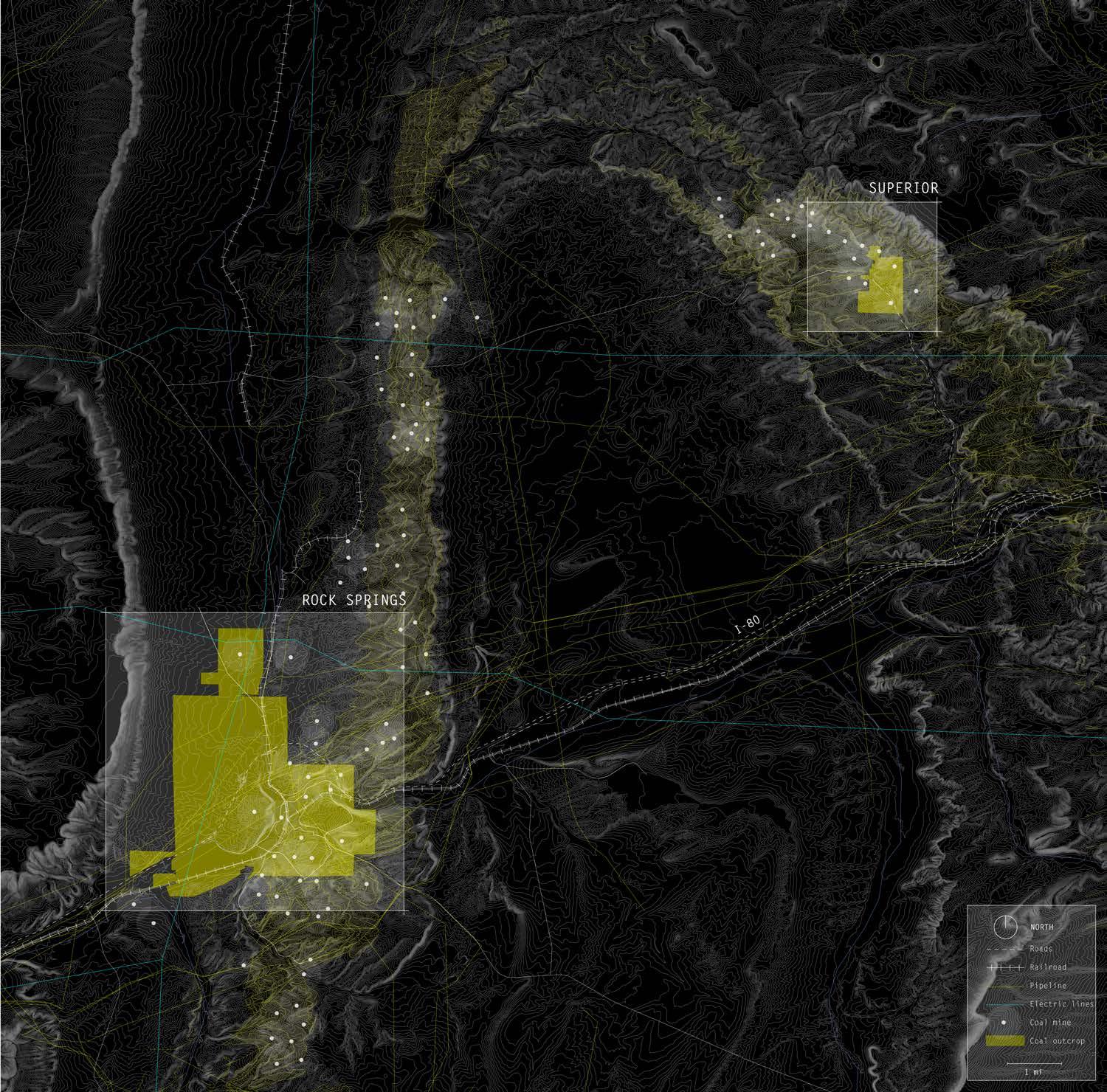

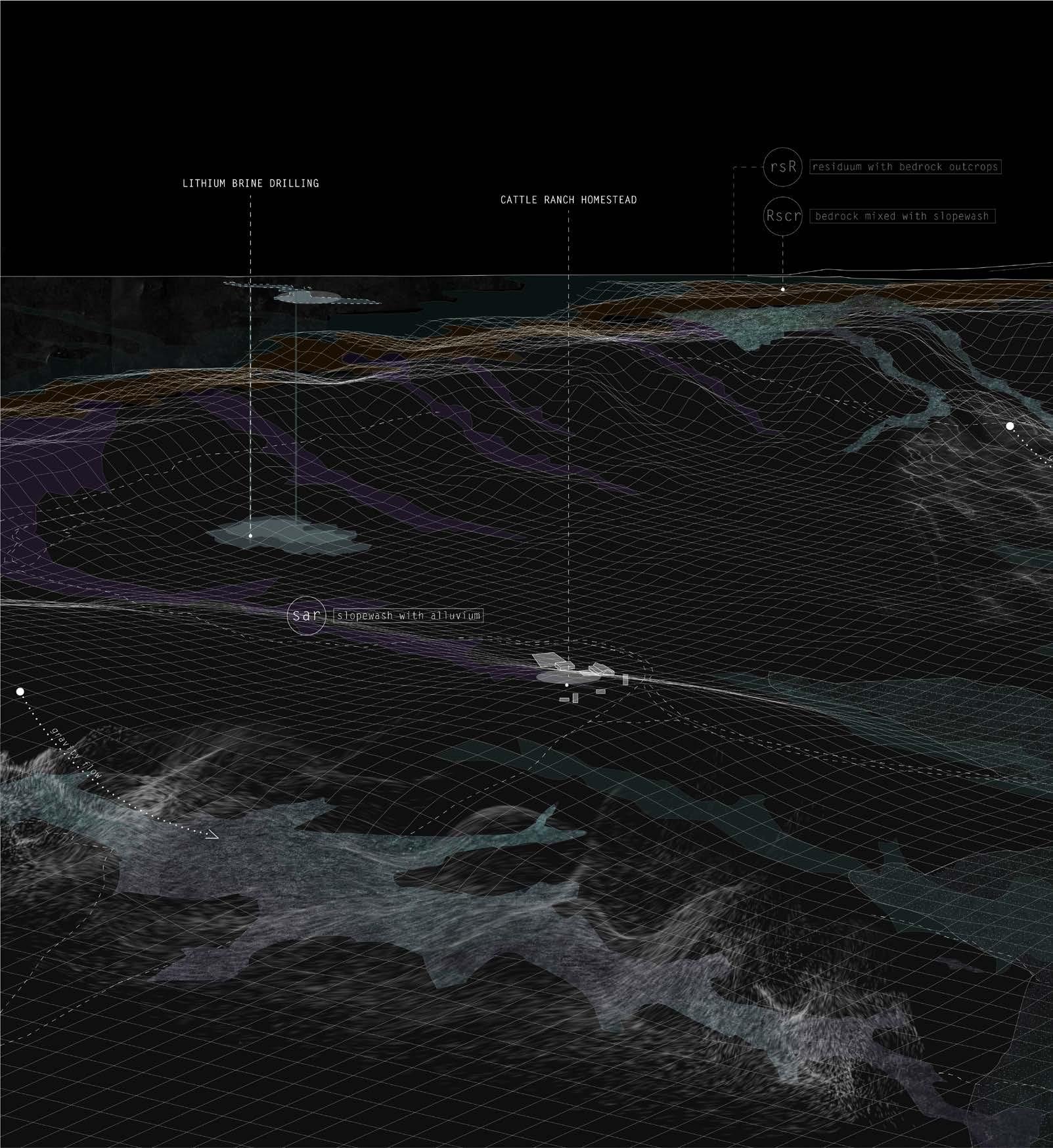

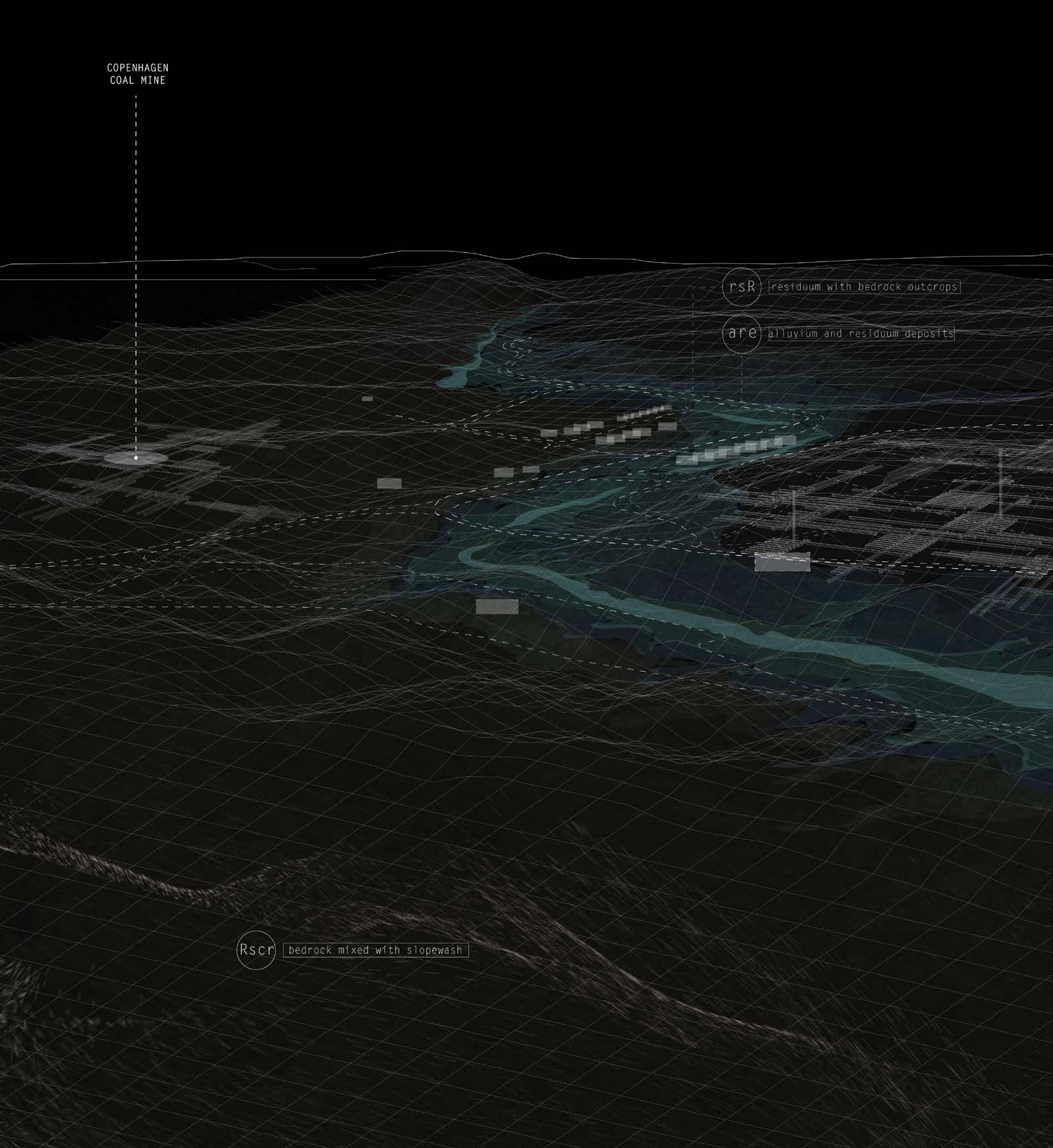

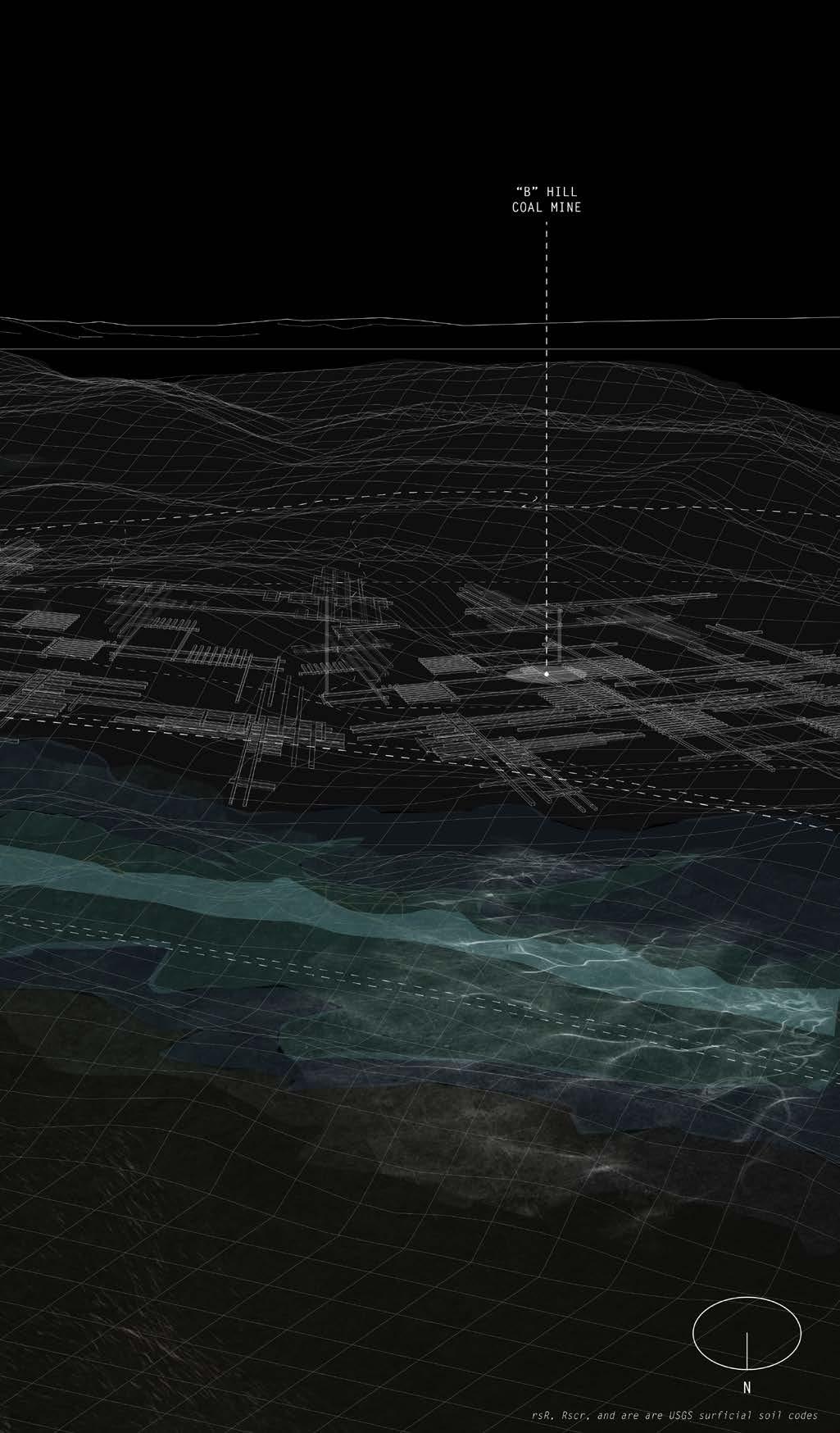

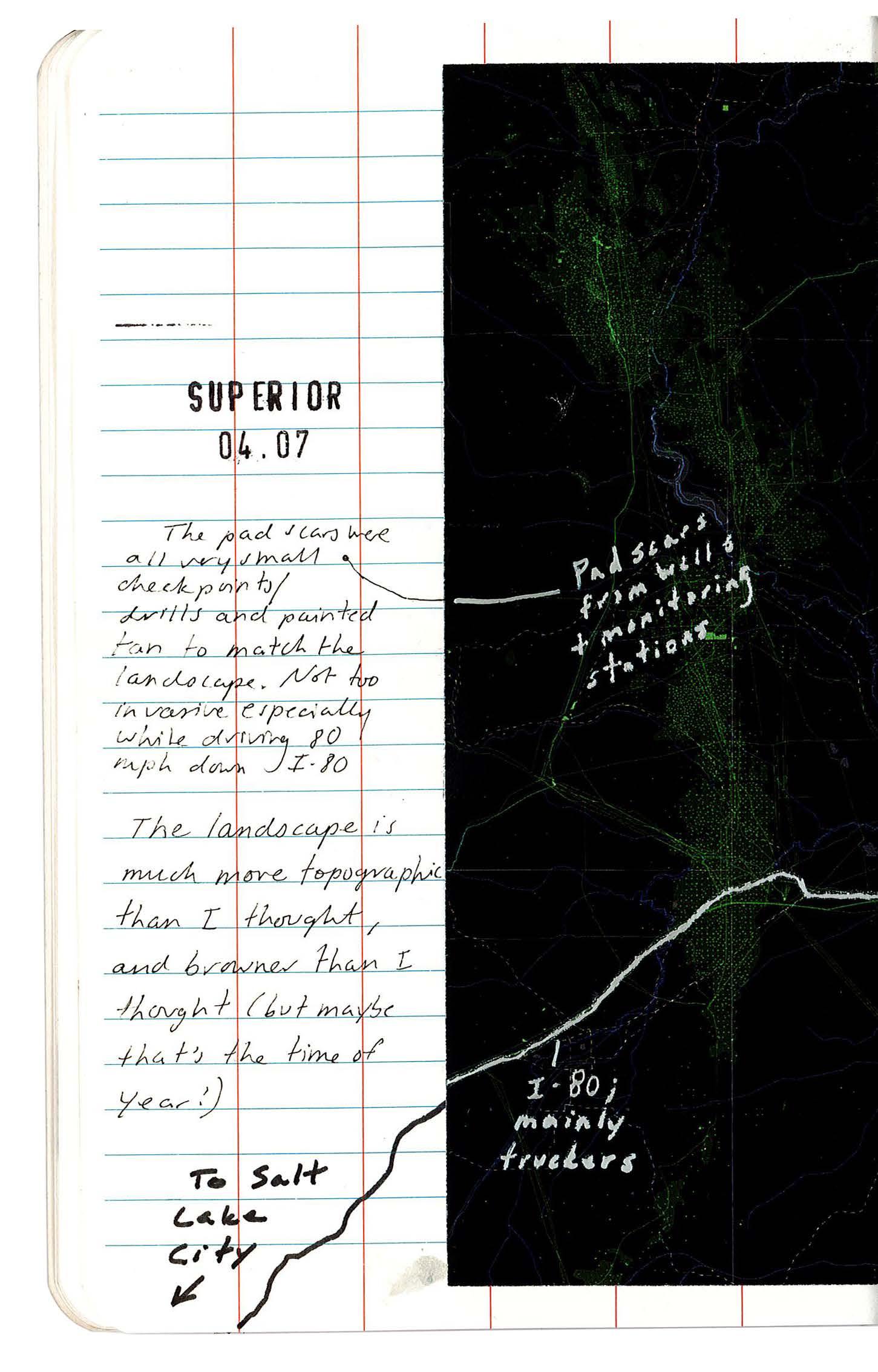

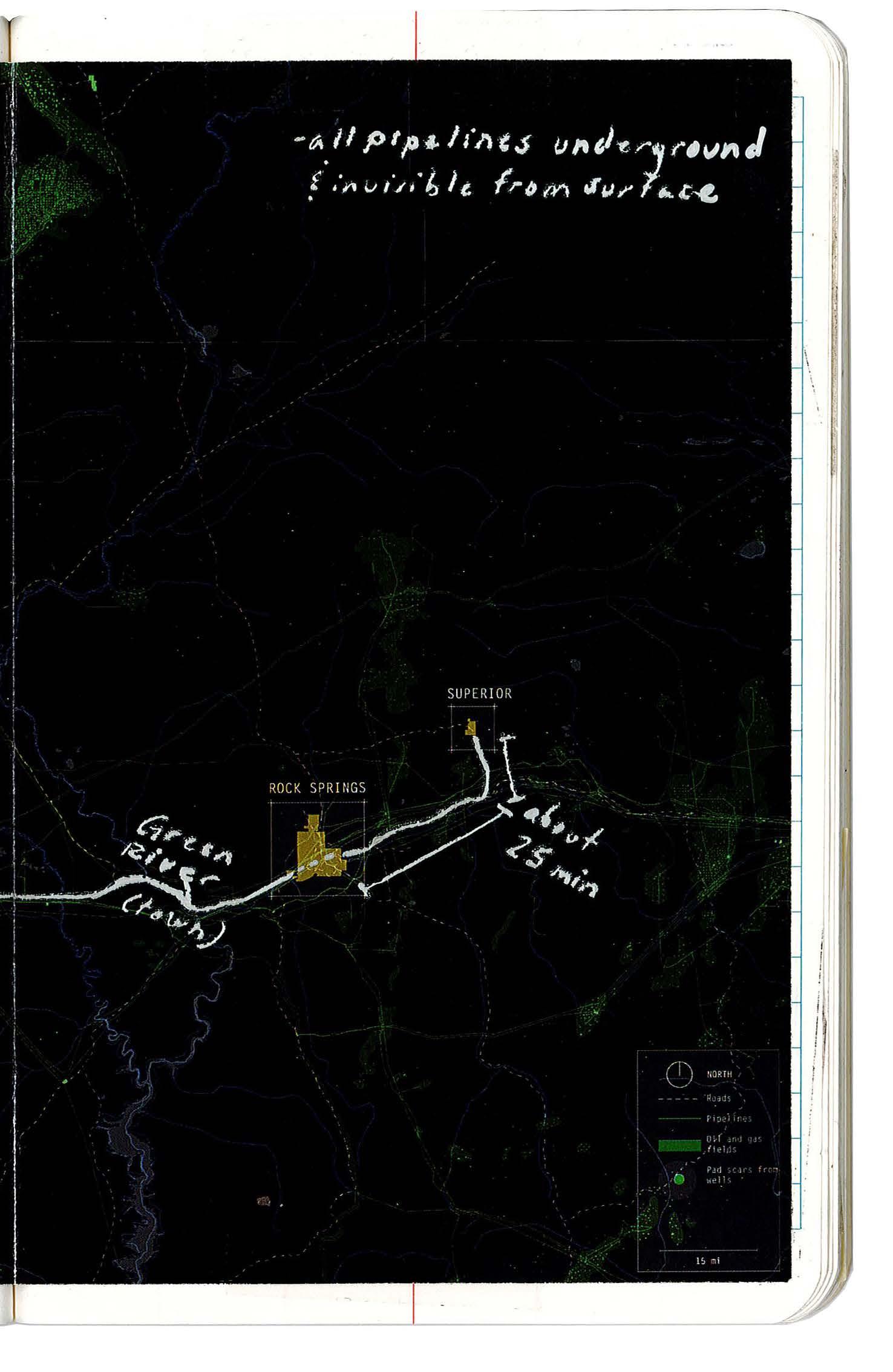

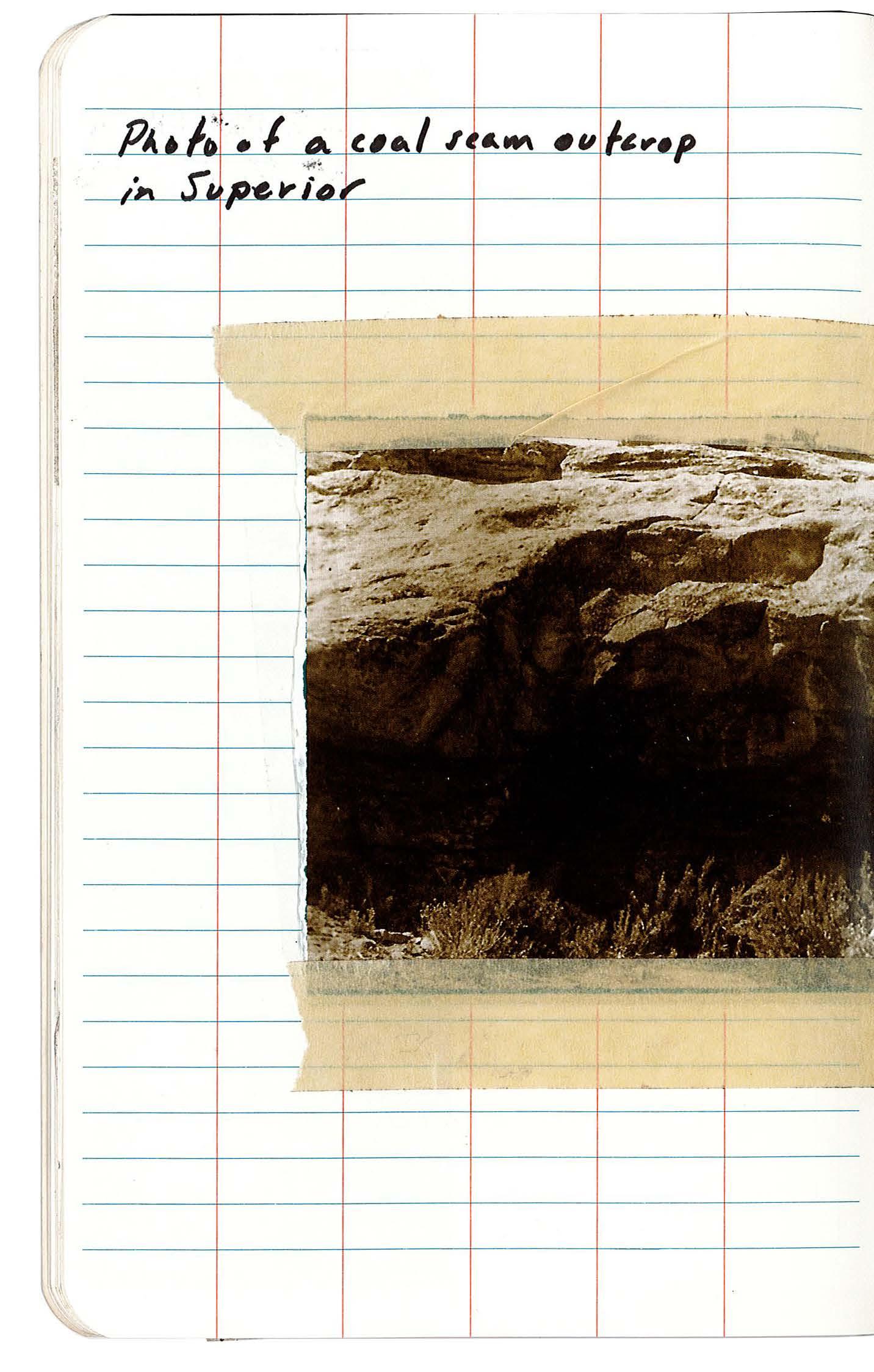

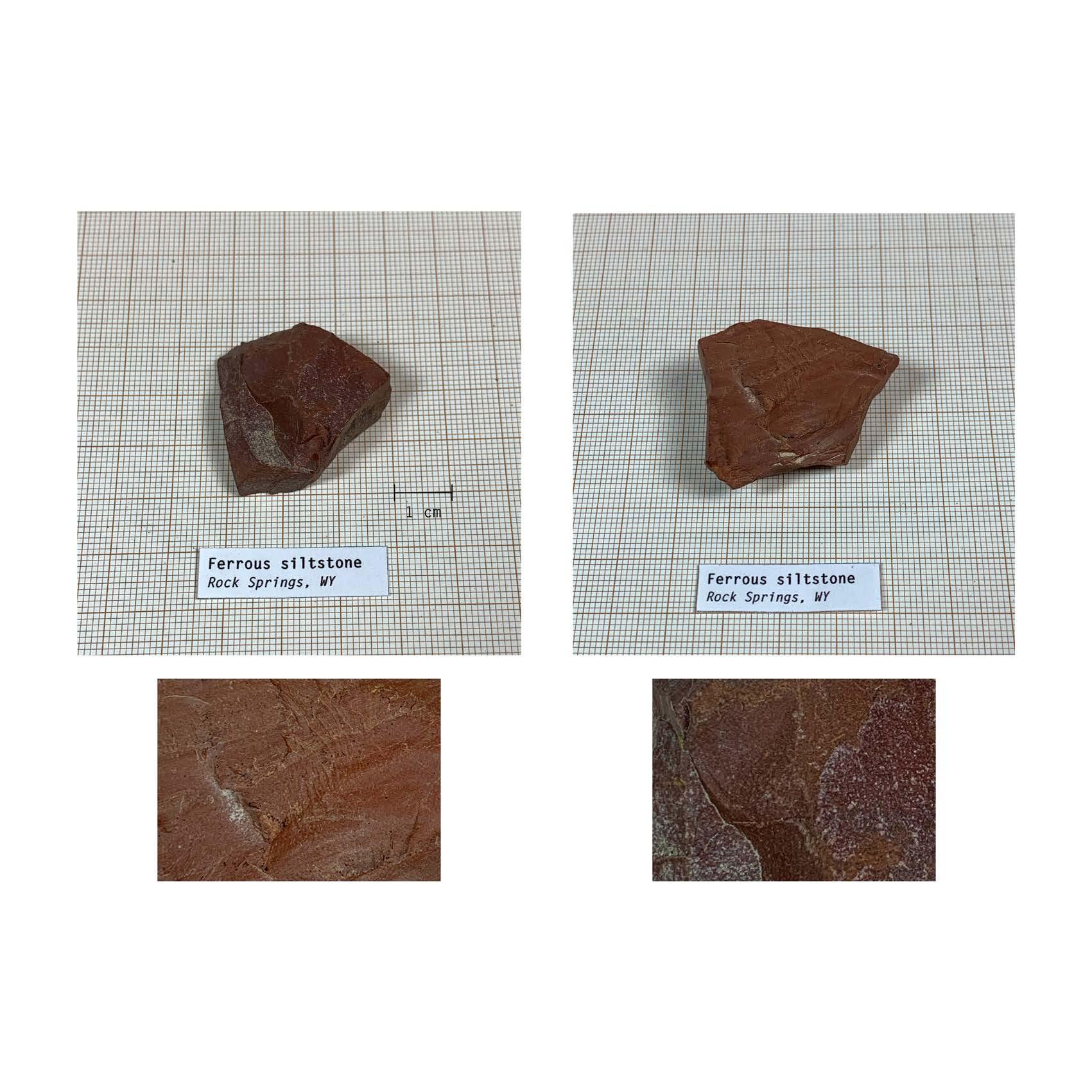

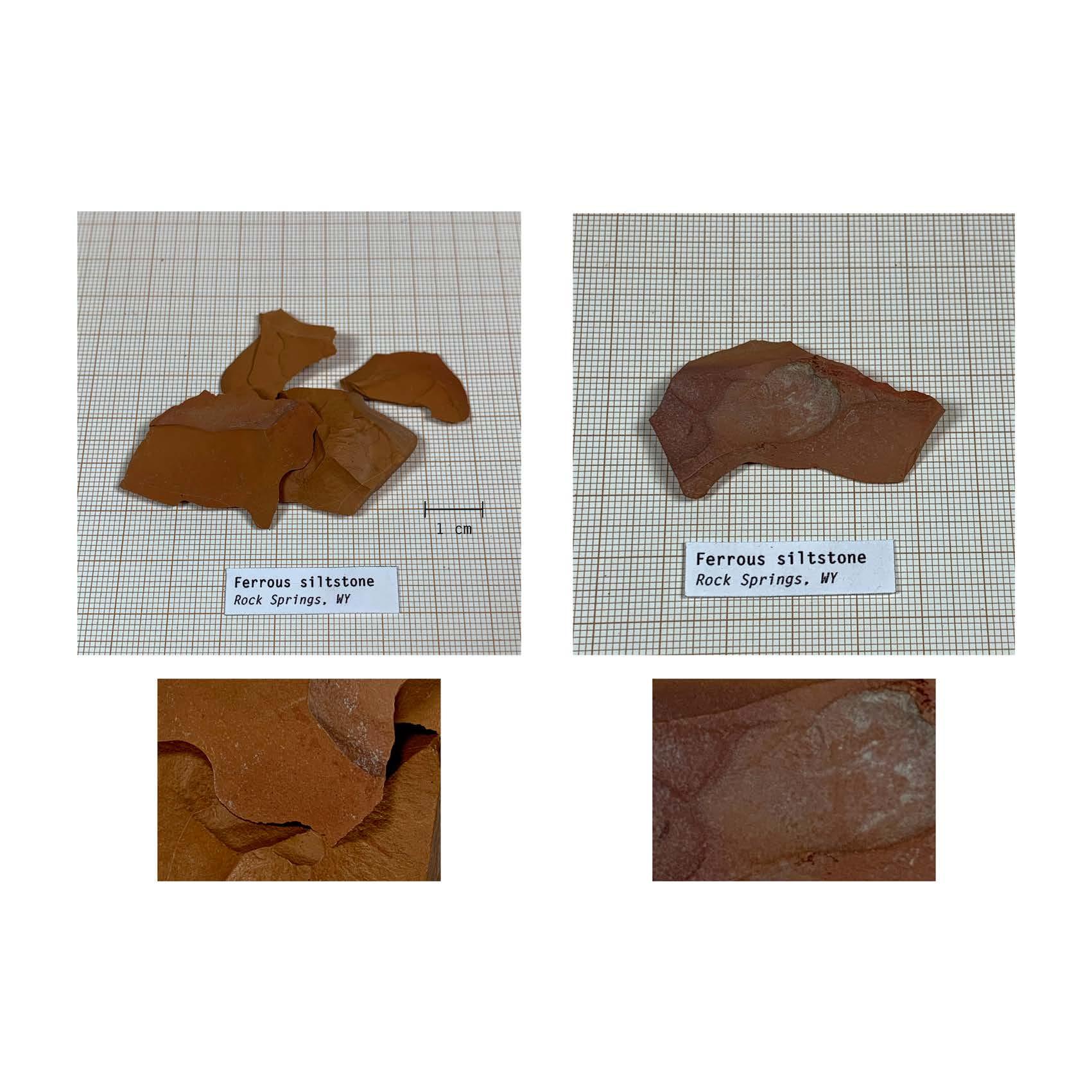

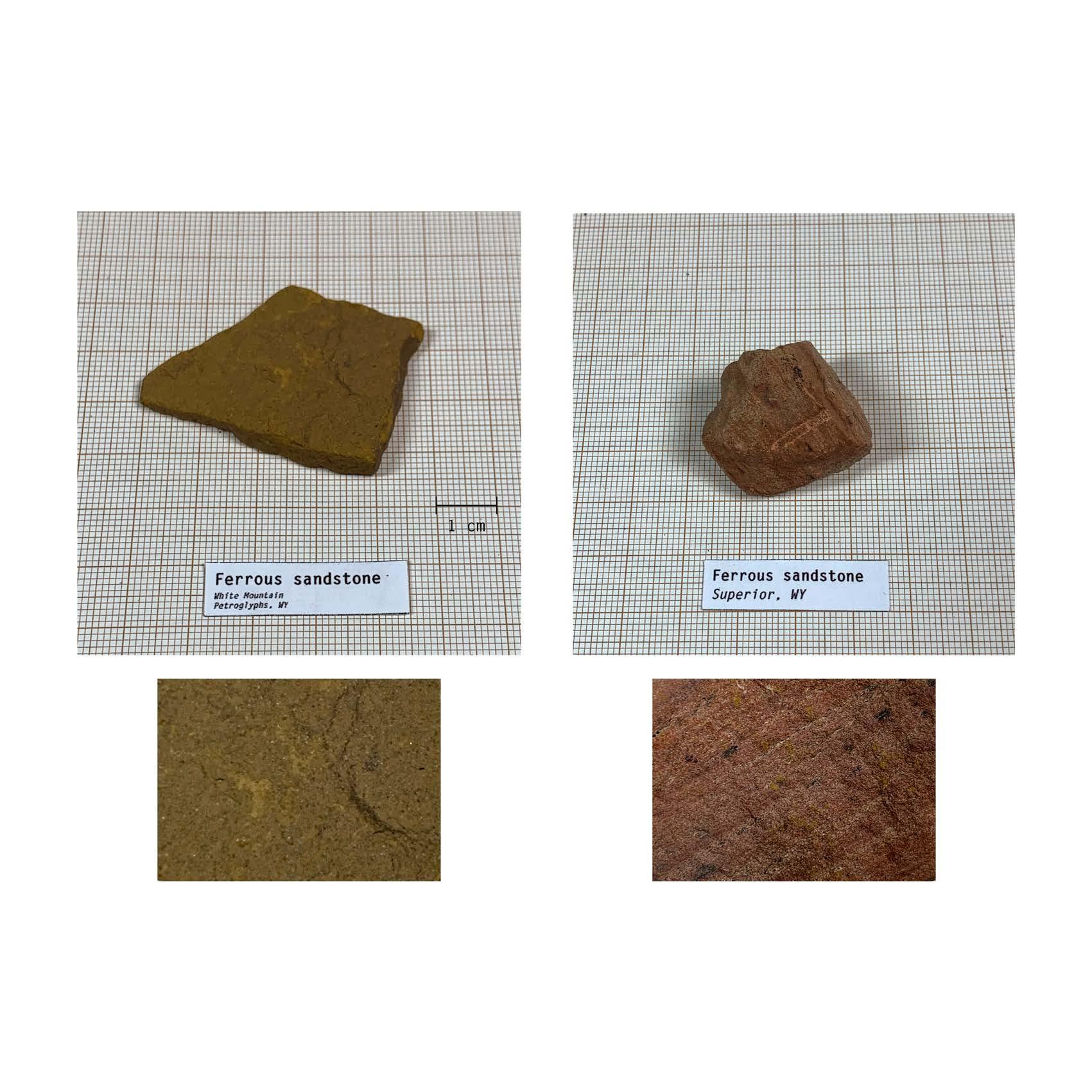

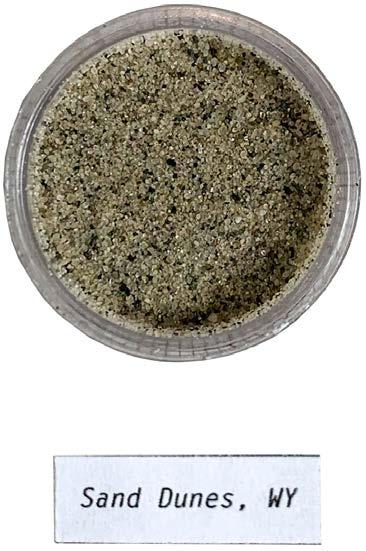

The act of mapping facilitated an understanding of Superior and Rock Springs’ territorial attributes at different scales and geological levels. Geology and geography intertwine to influence where people live, work, and the paths they travel. Only the oil field pad scars stippling the surface of the arid, barren Wyoming Red Desert give hint to the geologic richness and significance under the surface.

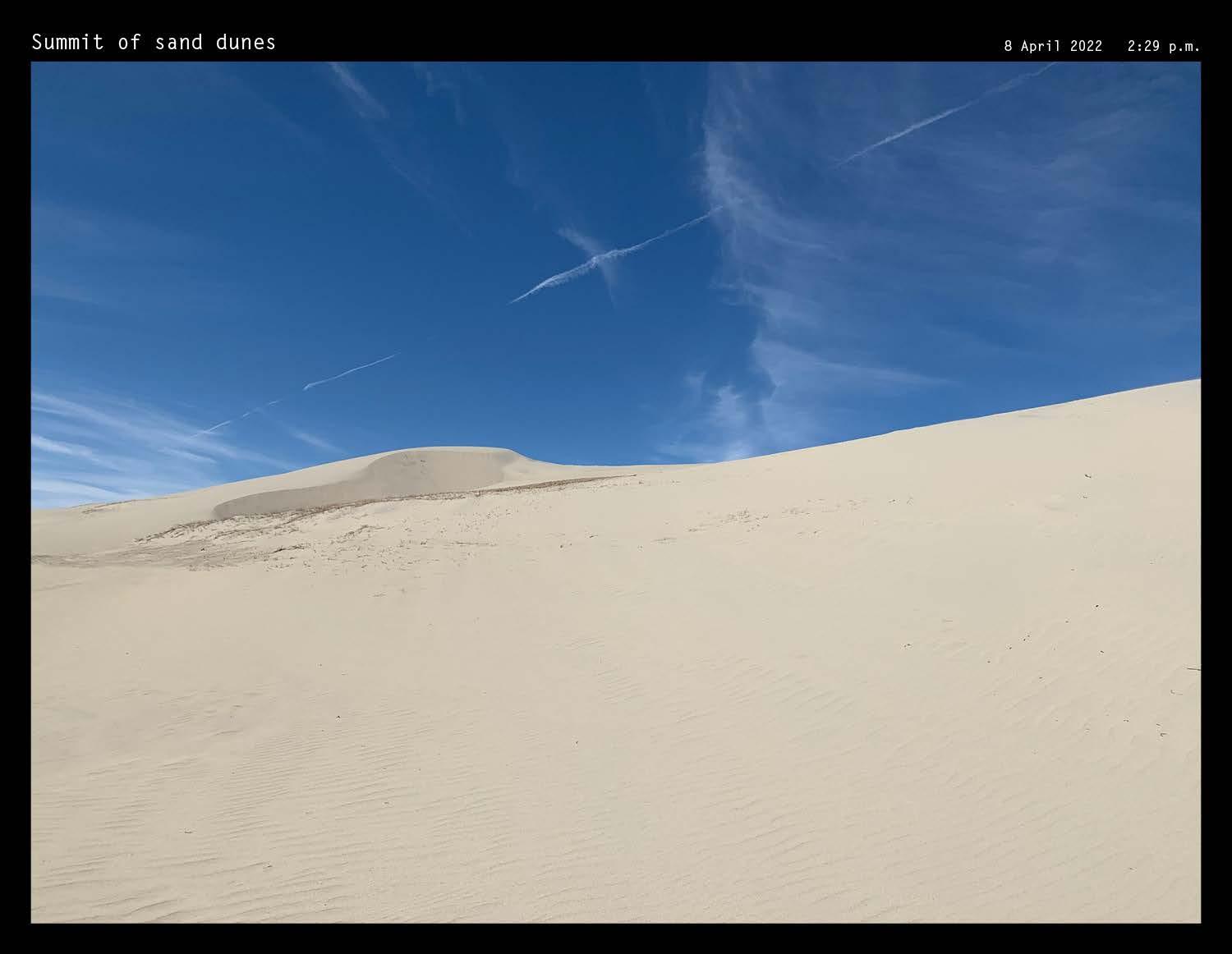

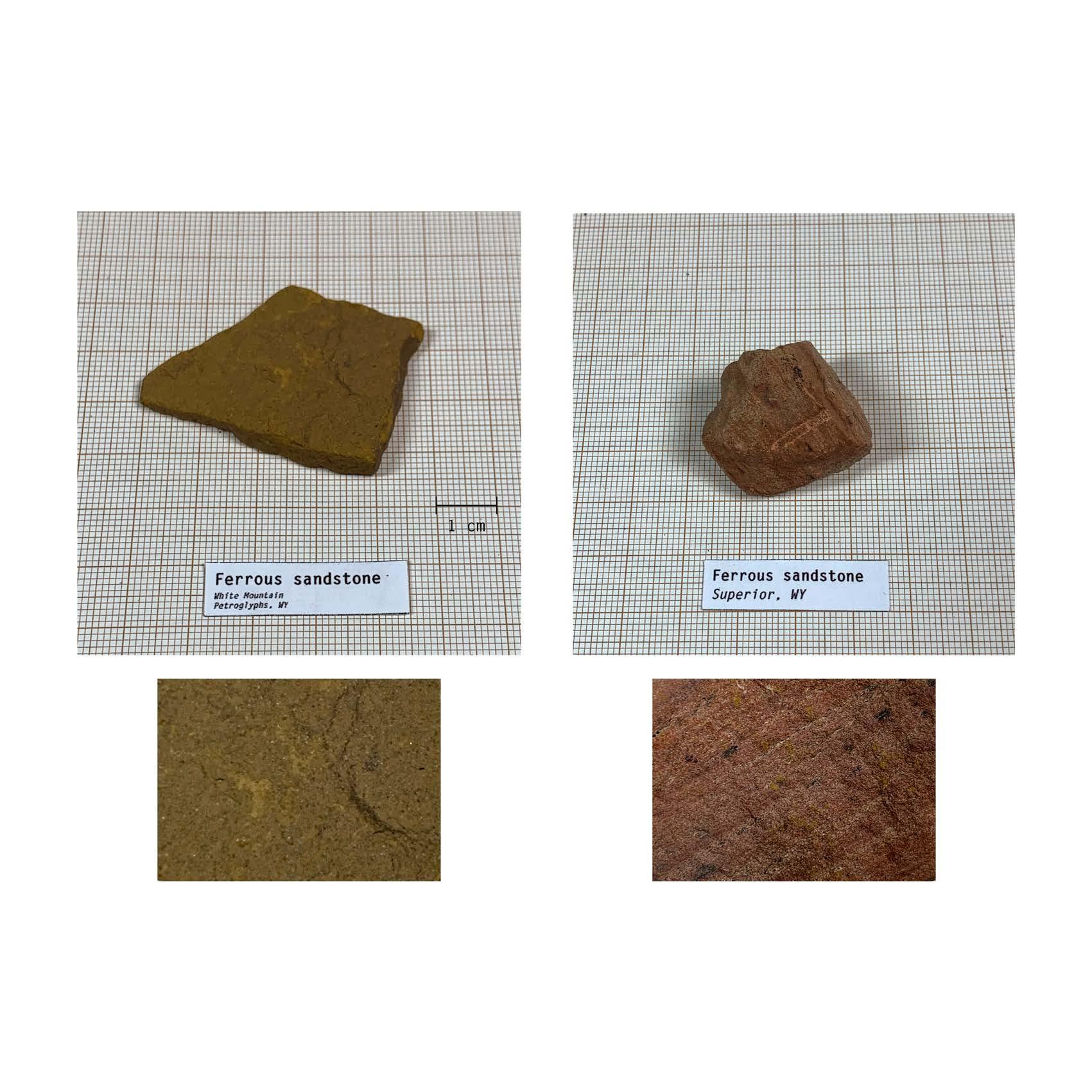

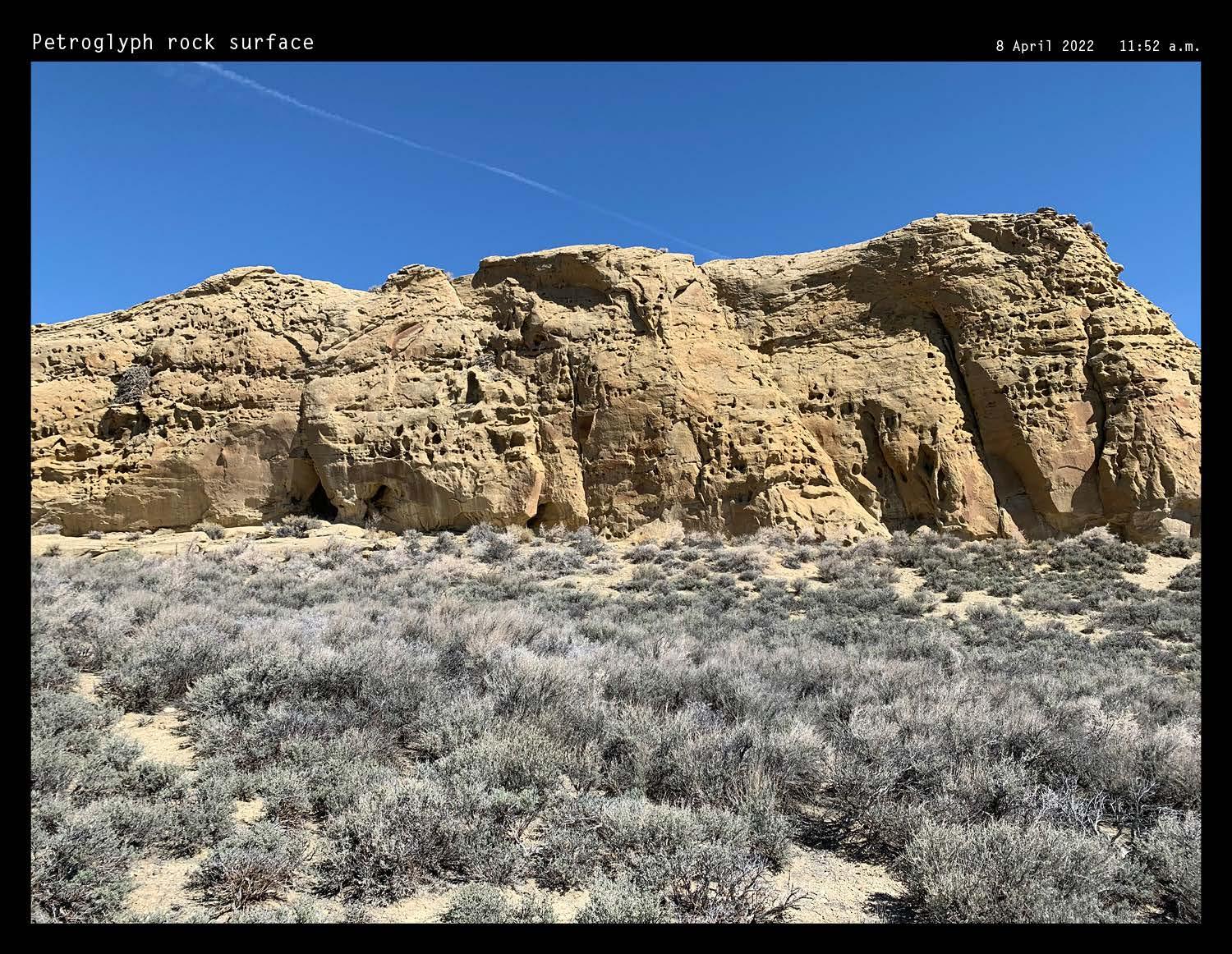

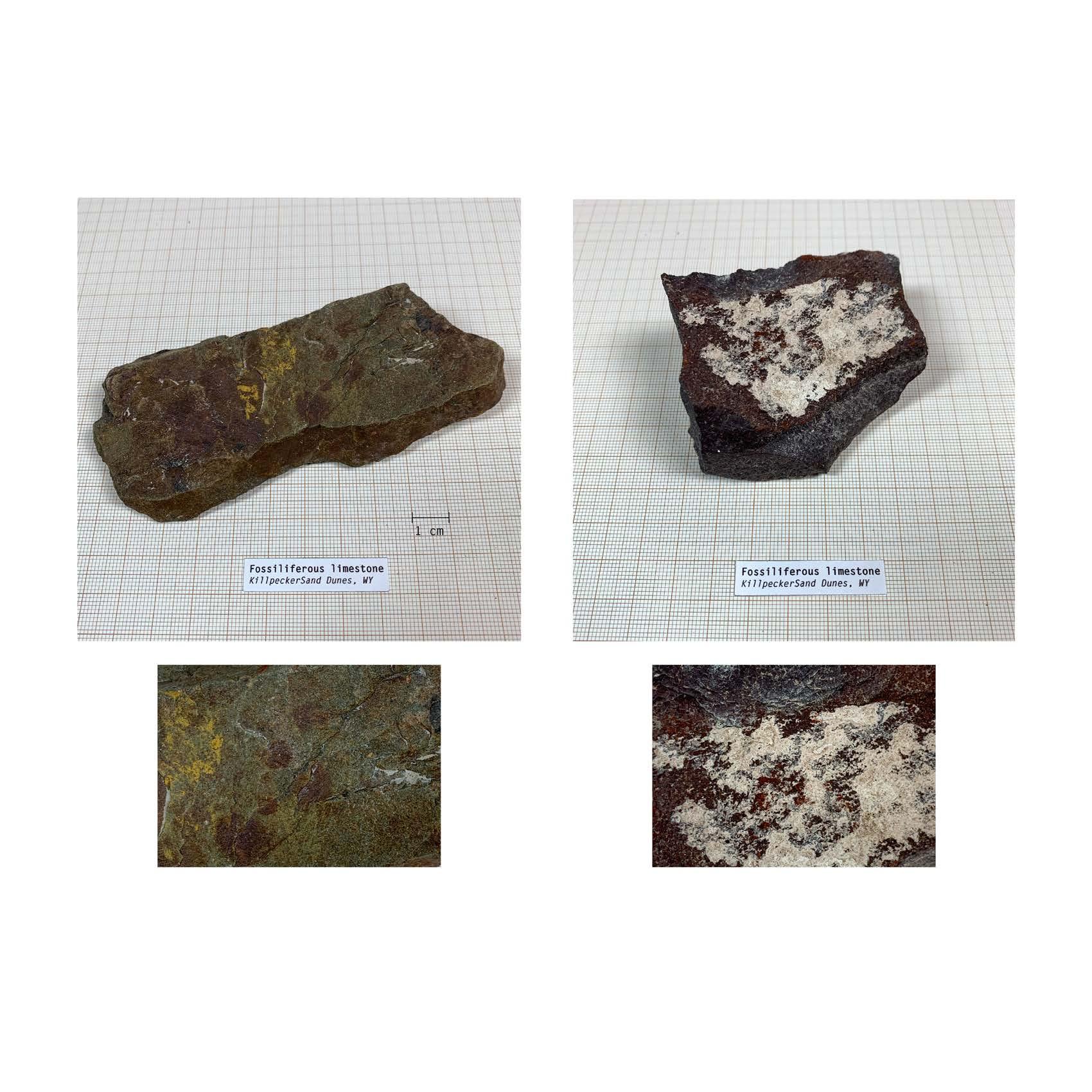

Human interest in this landscape ranges from the surface to -12,000 feet underground. Recreational locations, such as the White Mountain Petroglyphs, the vast field of the Killpecker Sand Dunes, and the dominant geologic monument of Boar’s Tusk attract both locals and out-of-staters to explore a landscape only typically used for extractive purposes.

Surficial exposed coal outcrops and coal deposits buried up to 8,000 feet underground first drew people to the Superior and Rock Springs territory. Because of the popularization of diesel fuel for locomotives, a geologic survey commenced and ended with the discovery of vast oil and natural gas reserves.

The discovery of lithium deposits about 25 miles north of Superior in 2013 continues Wyoming’s tradition as valuable land for extractive purposes. The thesis ties together both of this territory’s threads of intrigue by rendering visible operations of extraction while amplifying the recreational landscape.

65

VI Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes

66

15 mi

-10,500 ft

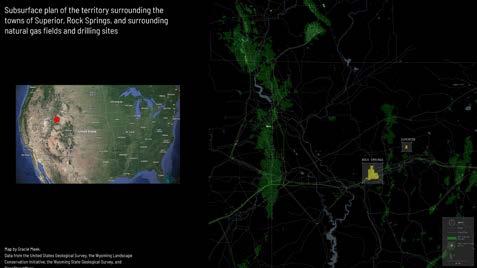

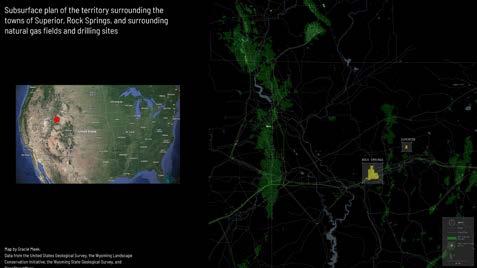

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

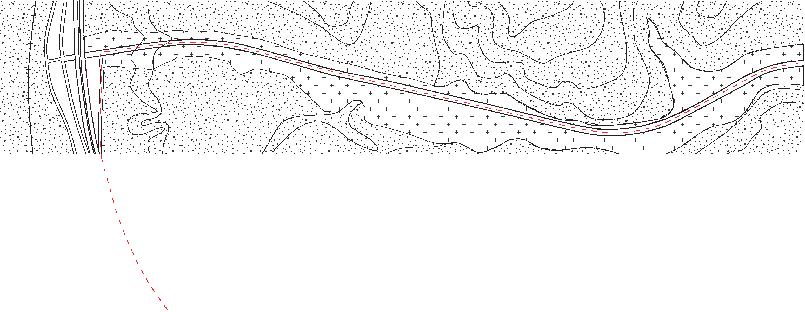

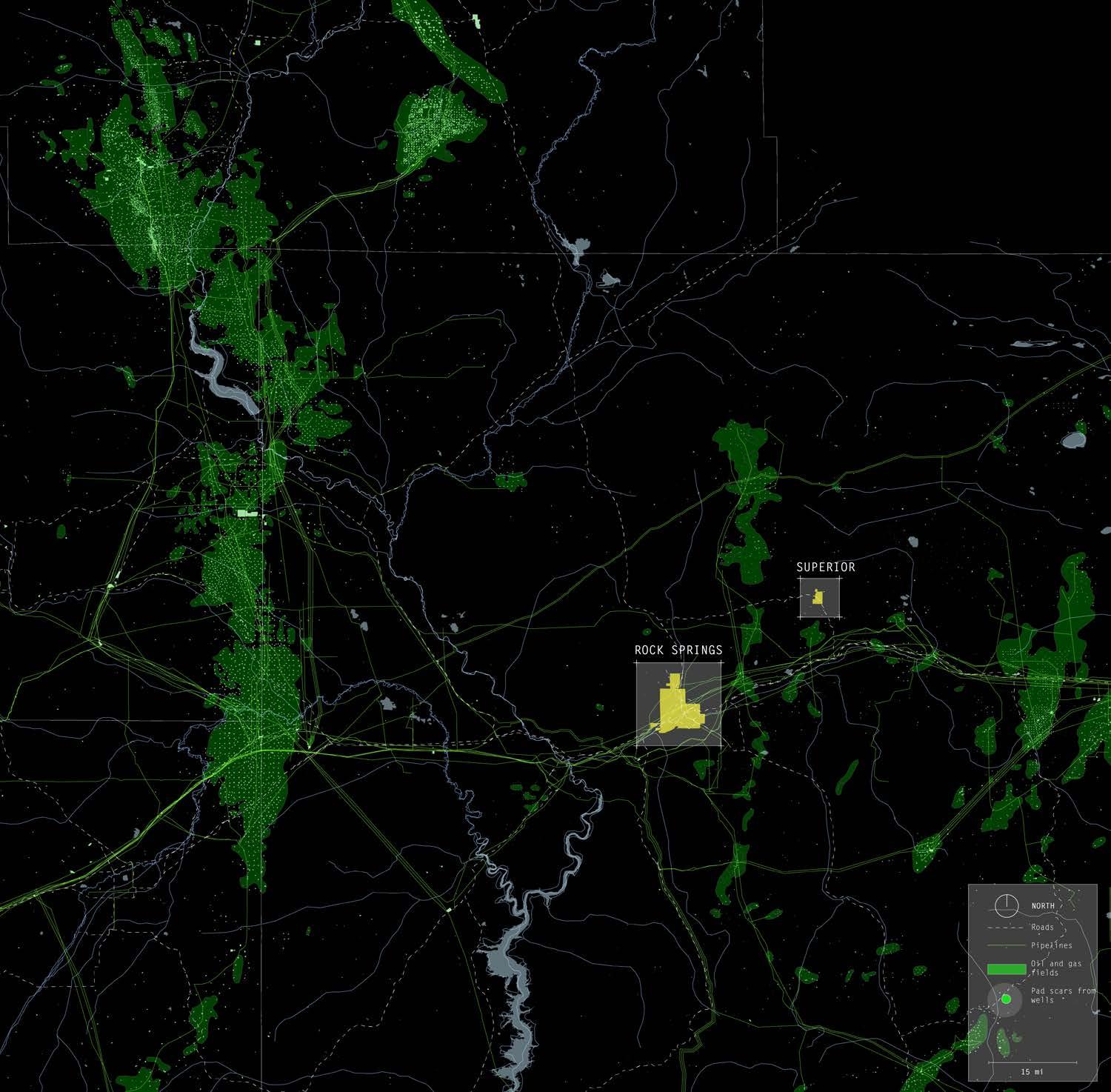

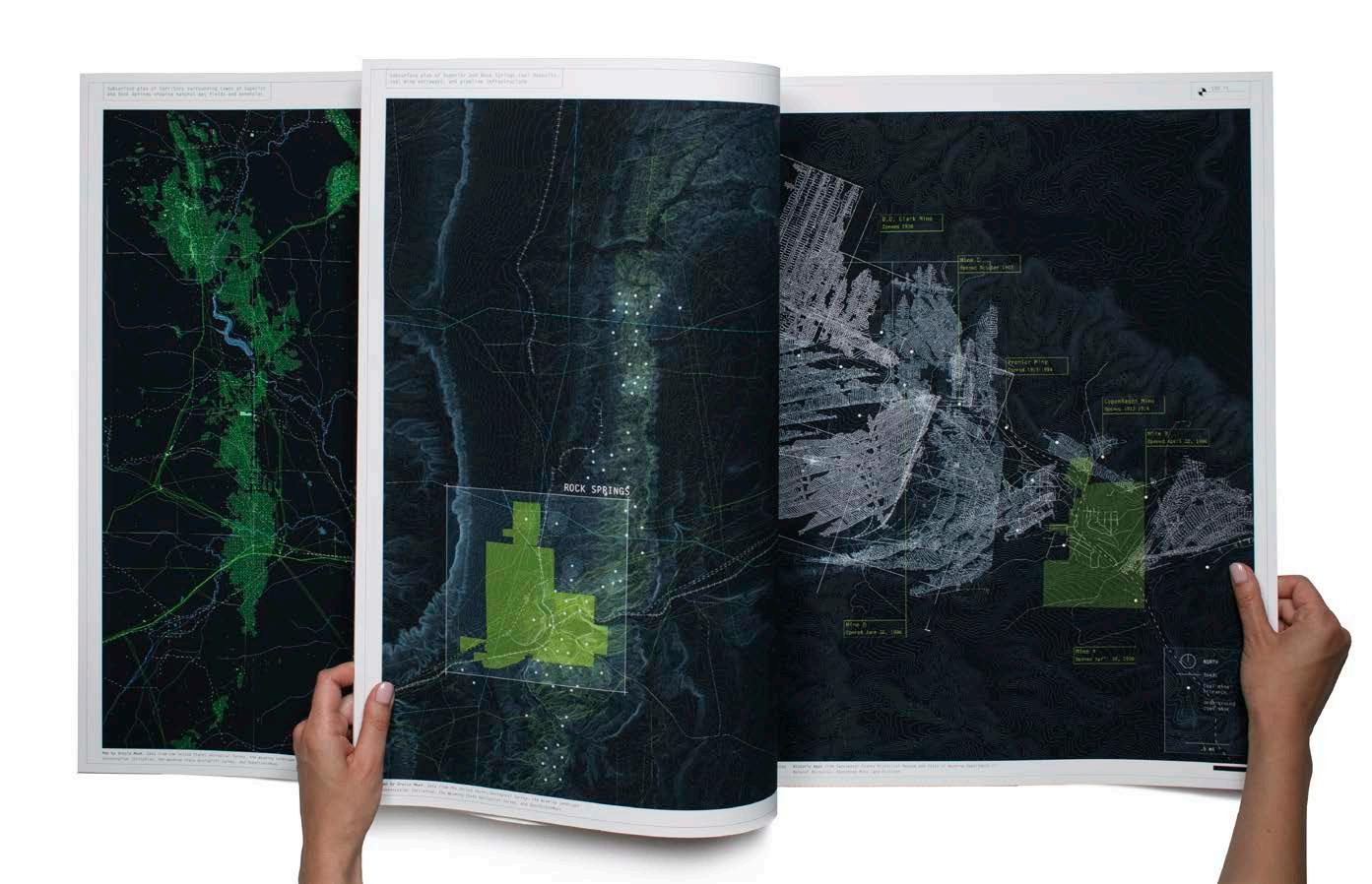

SUBSURFACE PLAN OF TERRITORY SURROUNDING TOWNS OF SUPERIOR AND ROCK SPRINGS SHOWING OIL AND NATURAL GAS FIELDS AND BOREHOLES

Oil field pad scars stipple the landscape above vast reserves of oil and natural gas buried -10,500 feet underground. Pipelines, both surficial and below ground, facilitate the transportation of these fossil fuels to refineries and power plants.

67

VI Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes

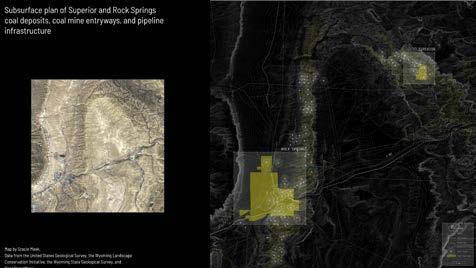

68 -200 ft 10 mi

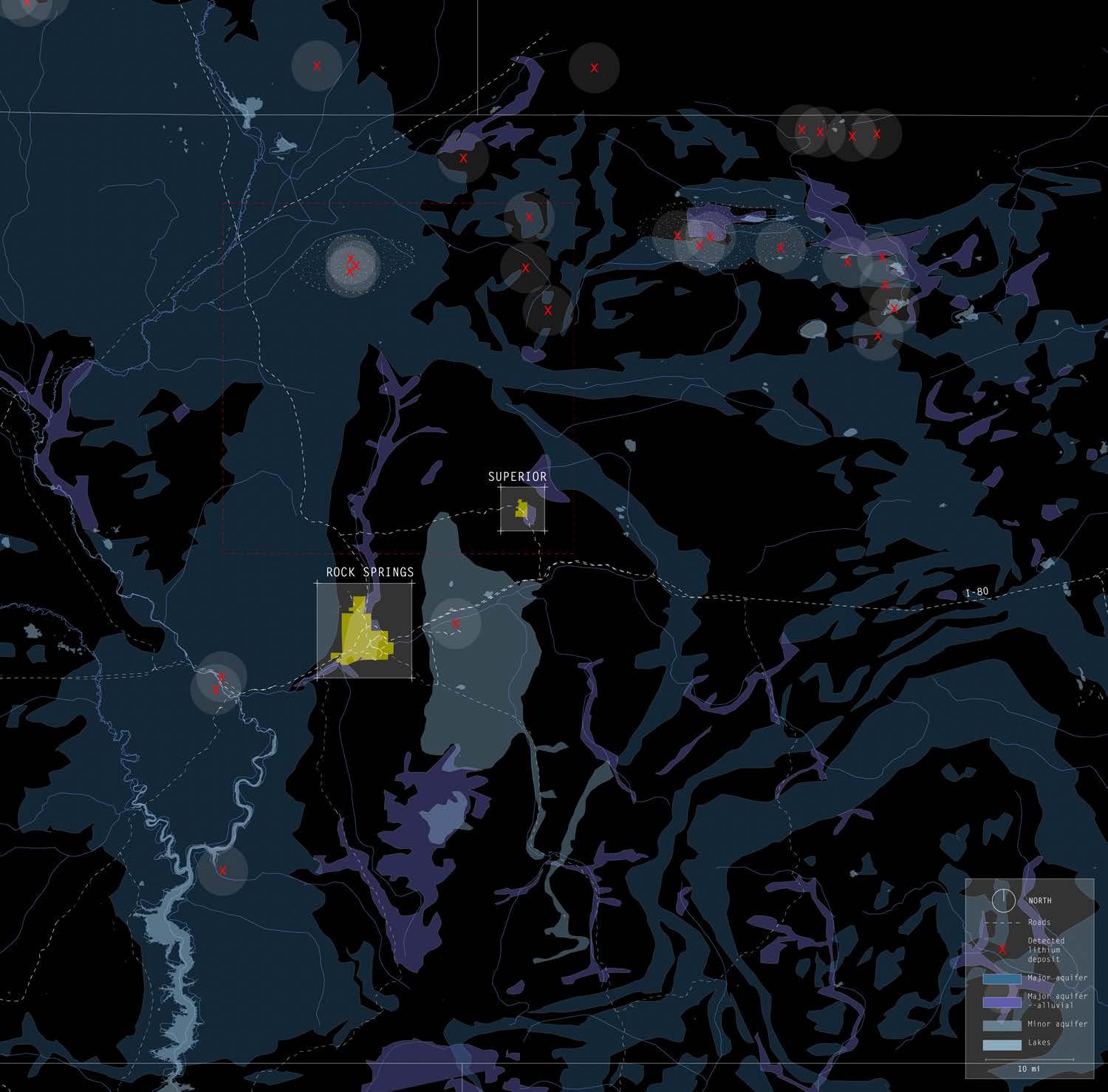

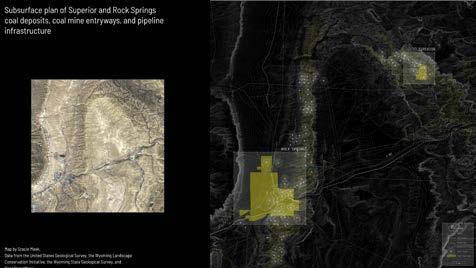

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

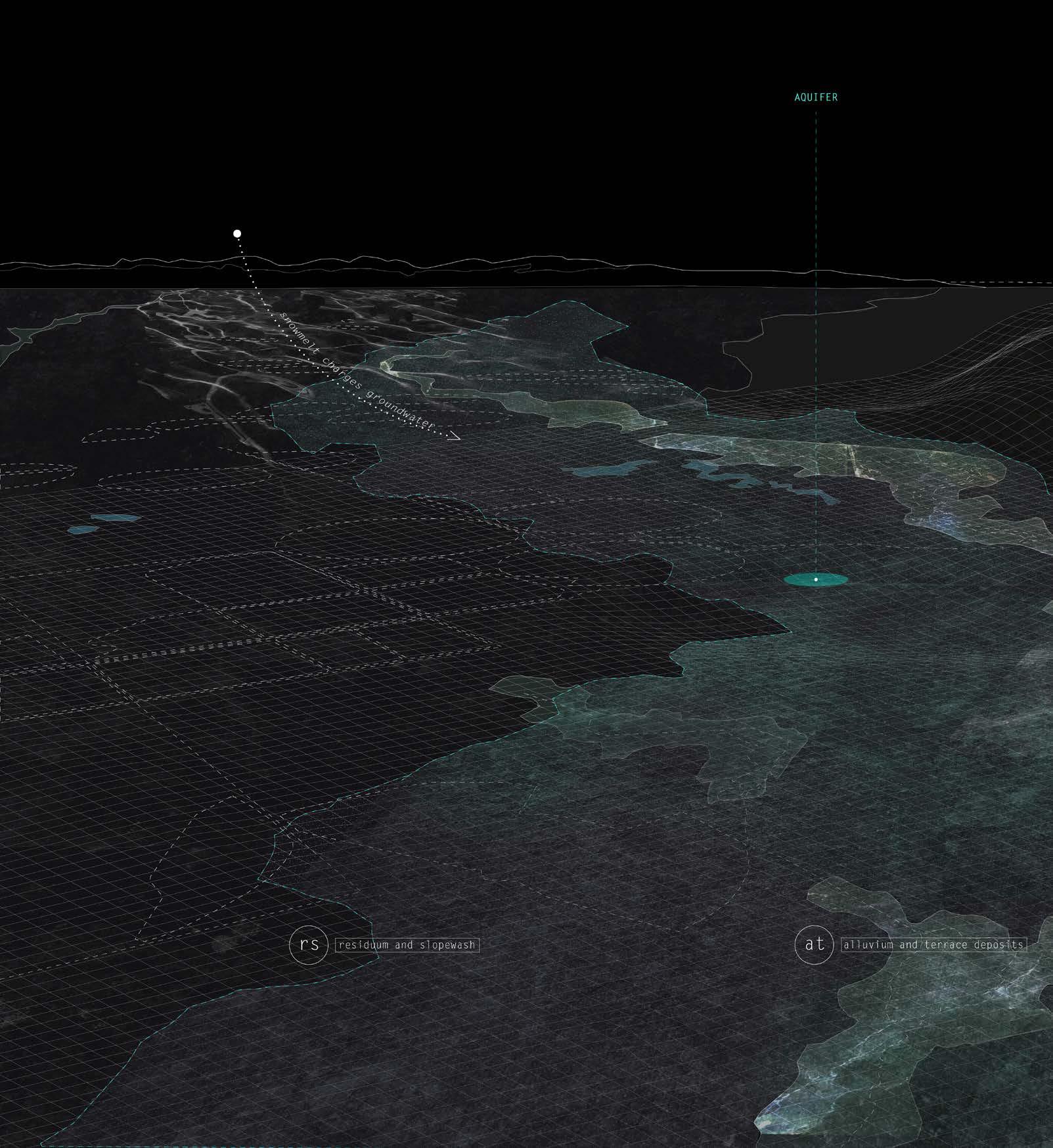

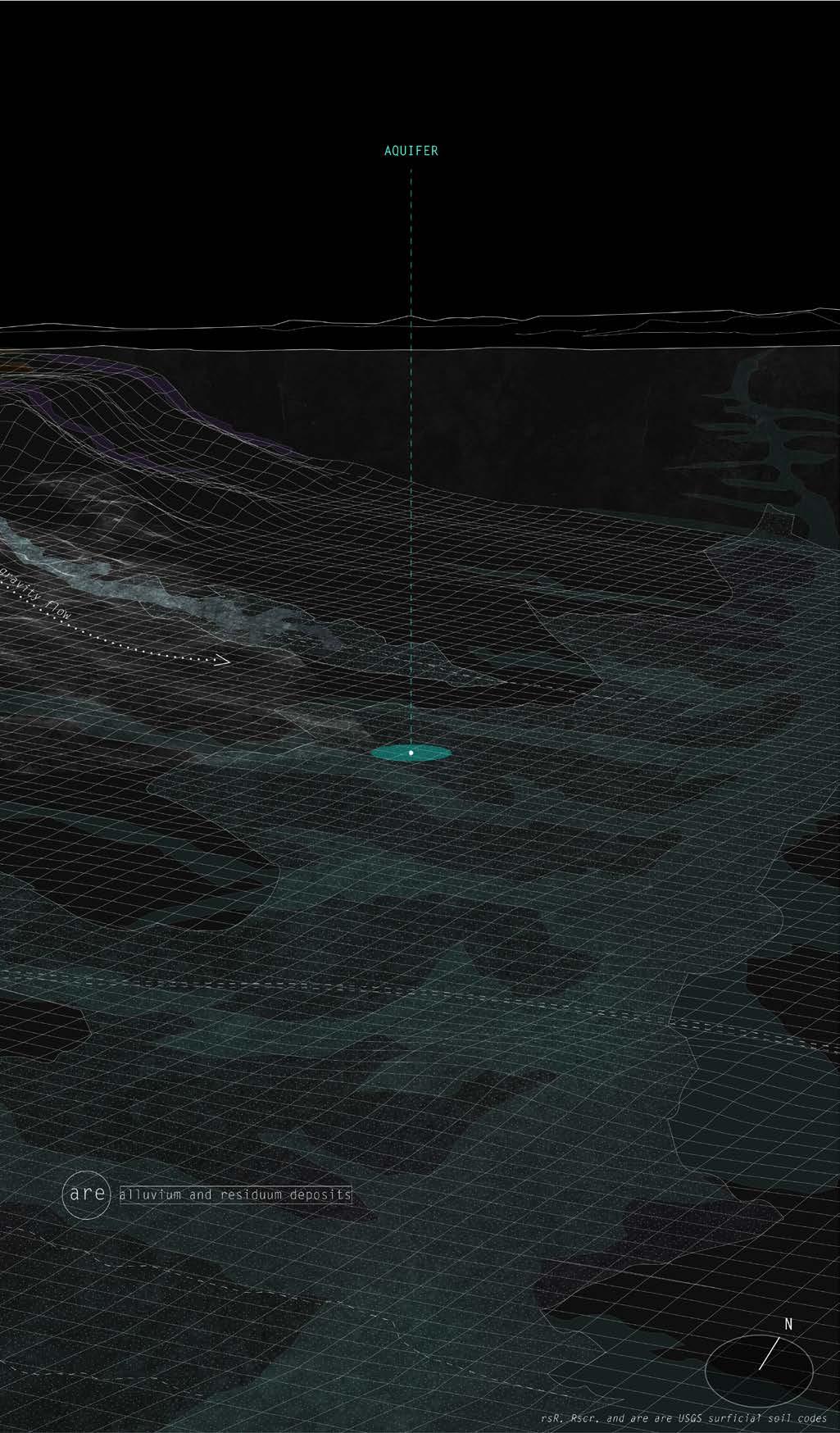

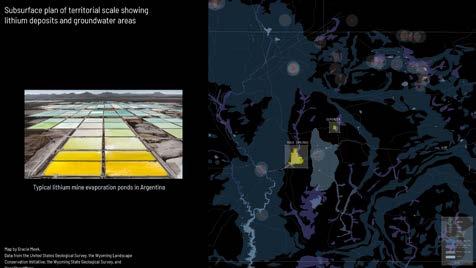

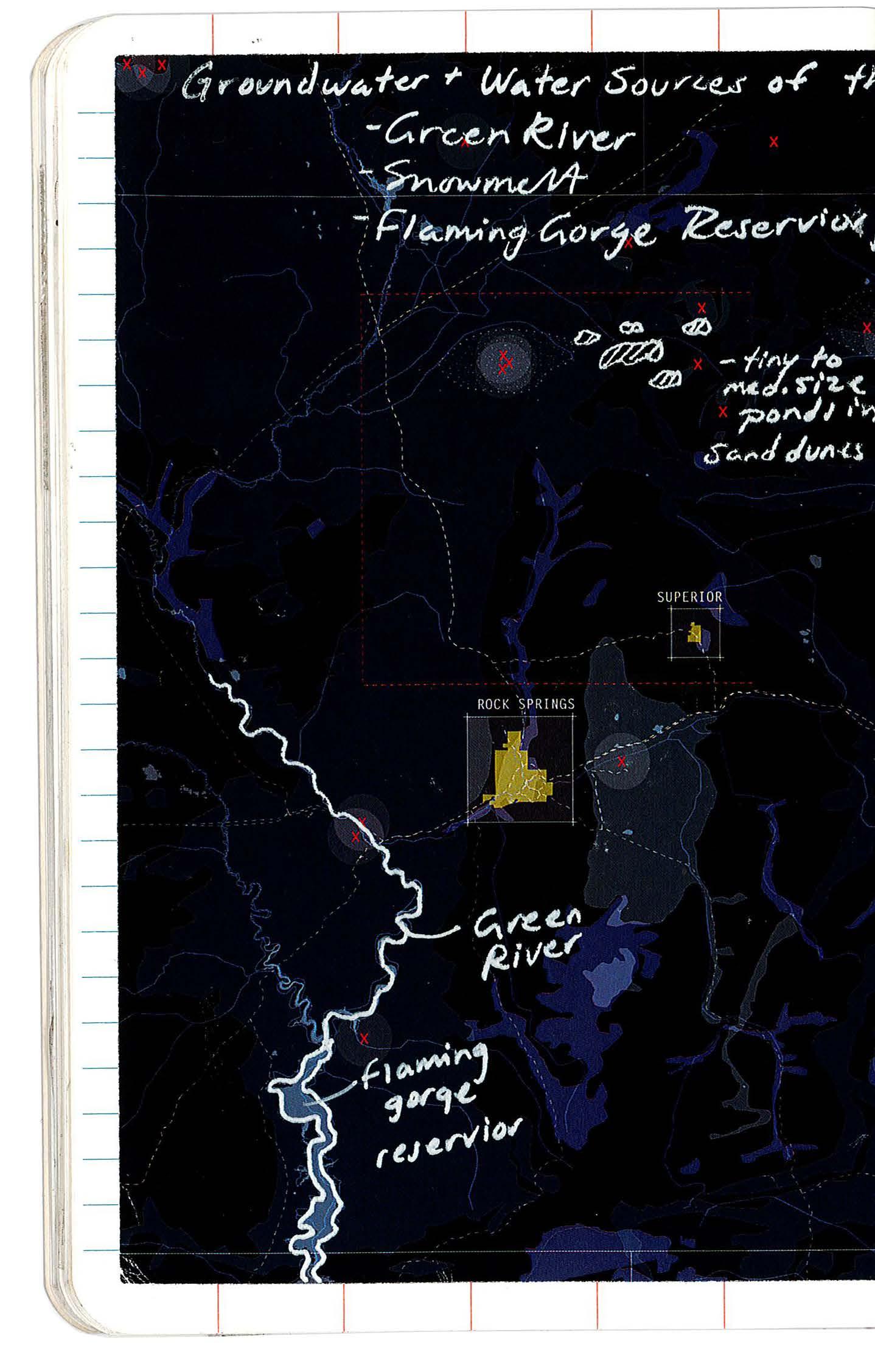

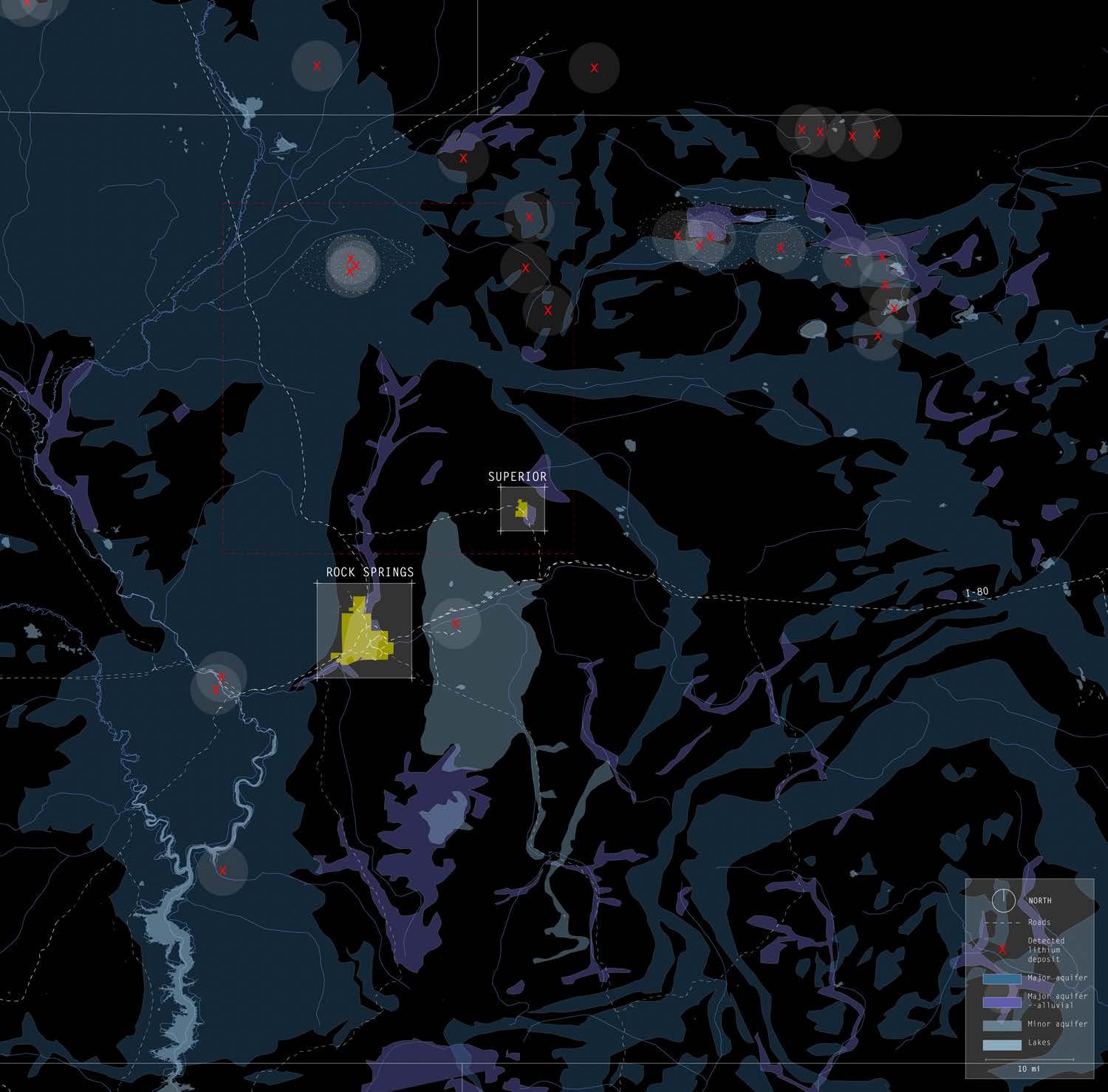

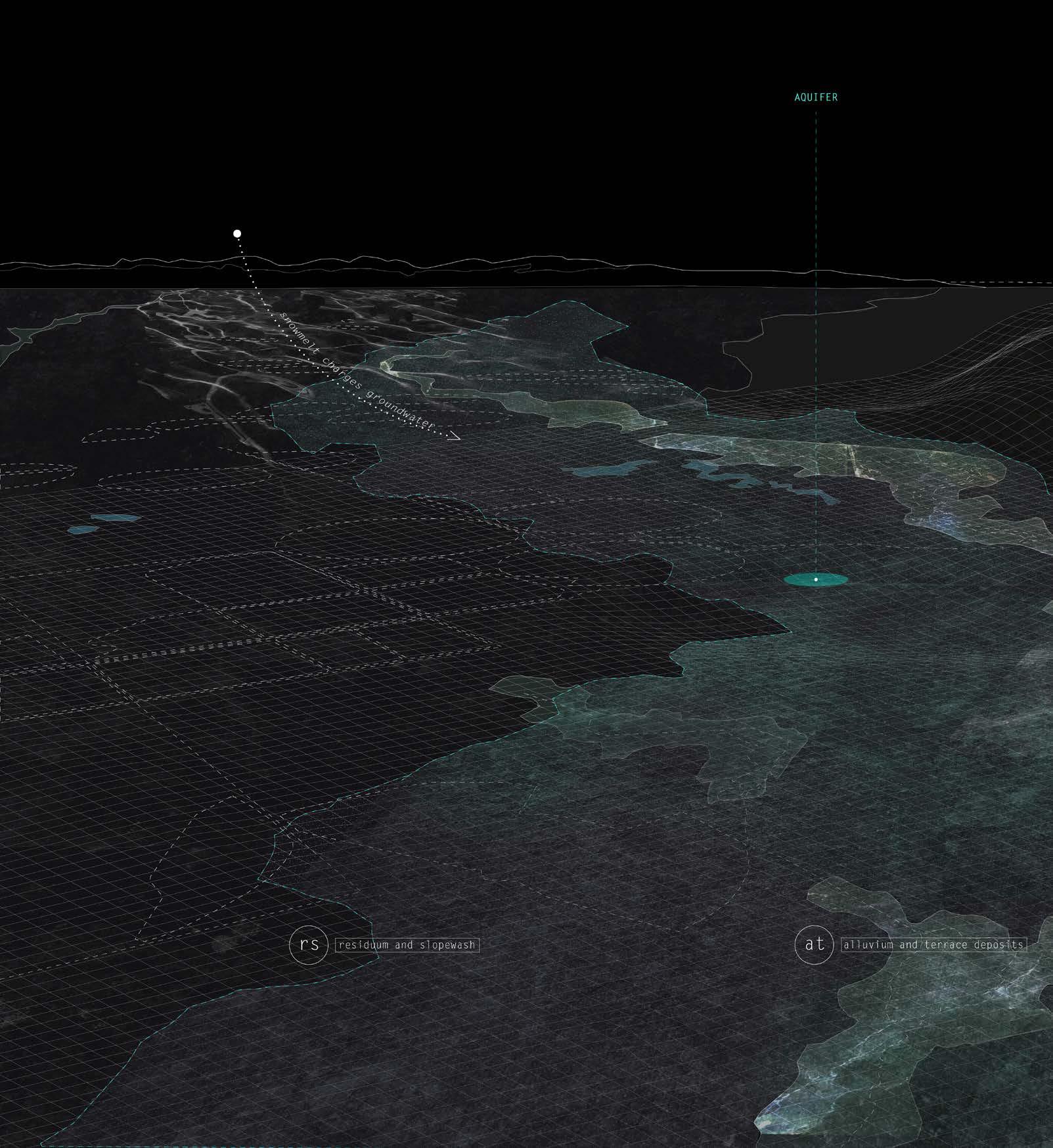

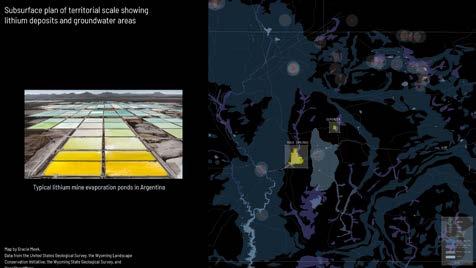

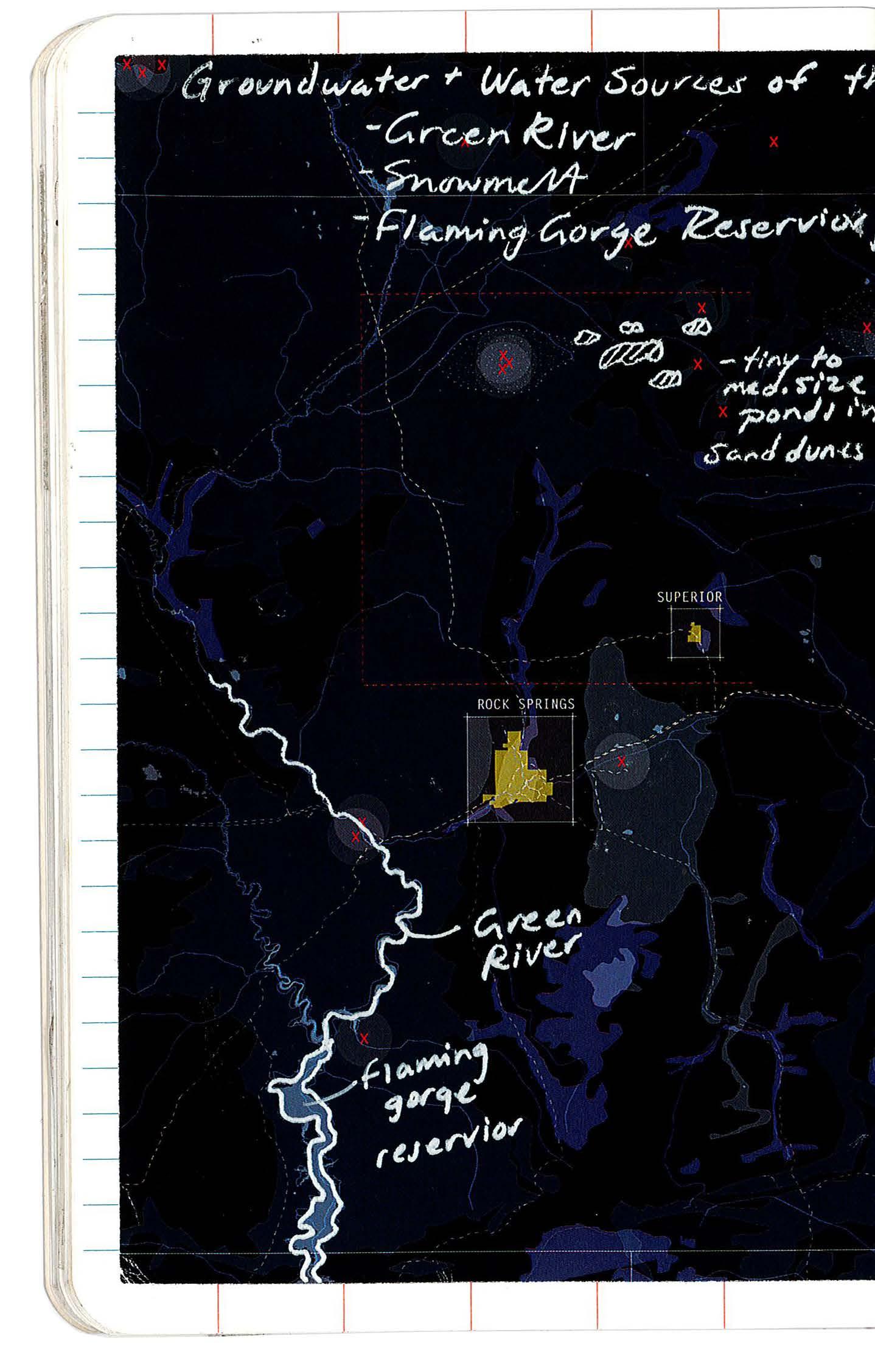

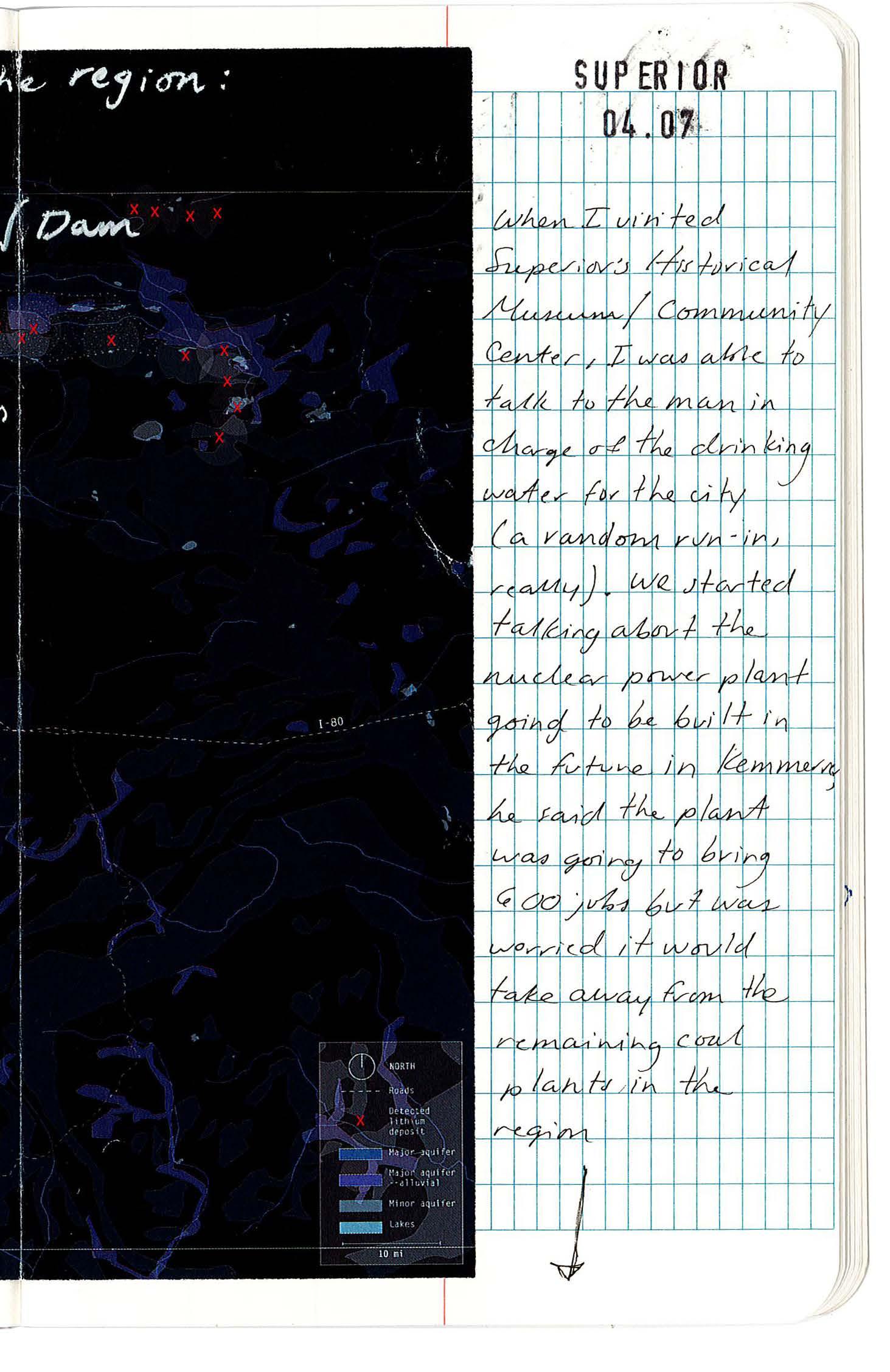

SUBSURFACE PLAN OF TERRITORY SURROUNDING TOWNS OF SUPERIOR AND ROCK SPRINGS SHOWING GROUNDWATER AND LITHIUM DEPOSITS

Lithium deposits have been located in an area about 25 miles north of Superior. With the cost of lithium increasing exponentially, construction might ensue within the next 15 years. Superior will see a large influx of migrant workers like it has in the past as a bedroom city for Rock Springs extraction.

This territory also supports alluvial aquifers and major/minor aquifers, which will be depleted if construction of the lithium mine proceeds.

69

VI Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes

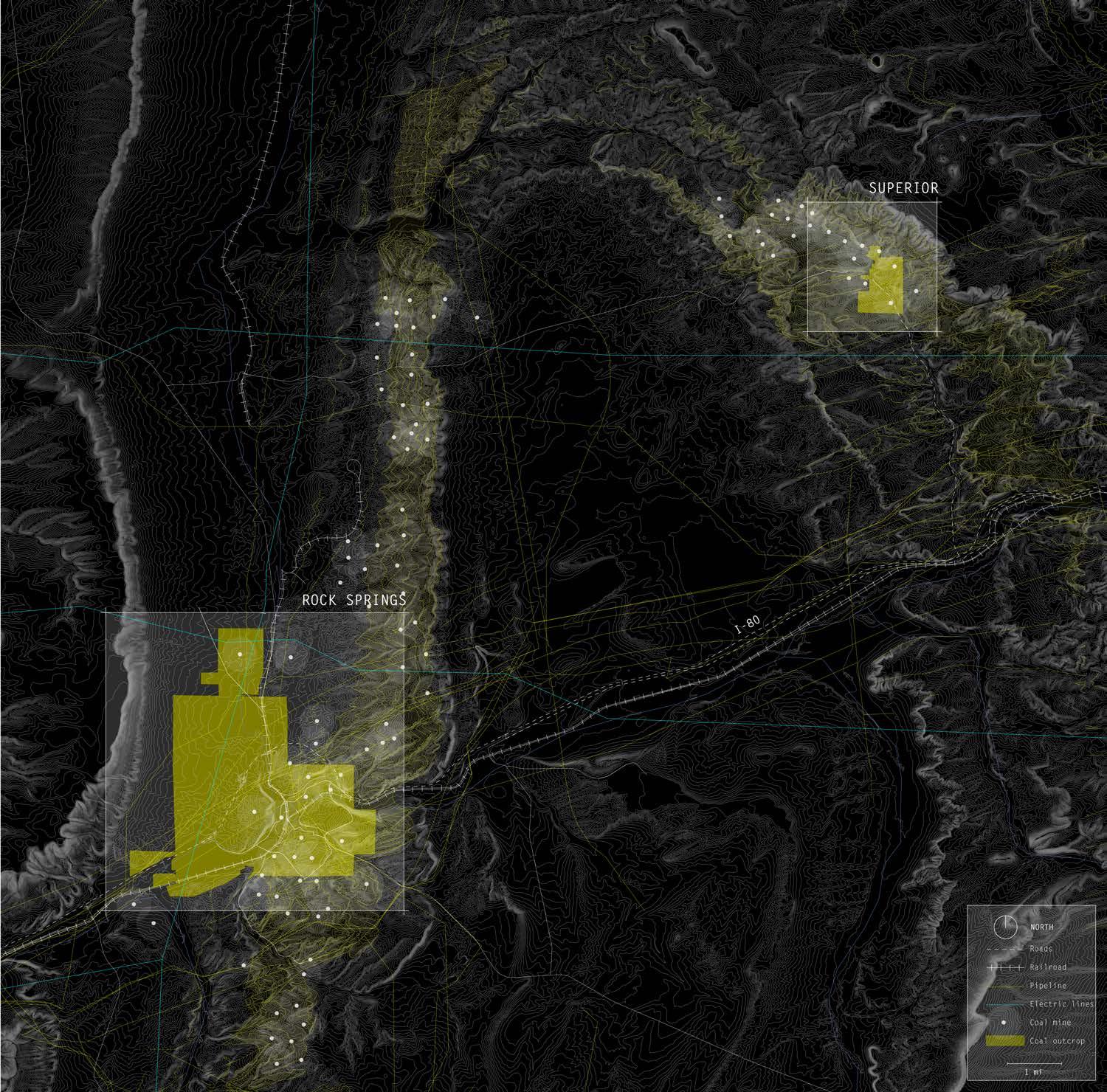

70 -50 ft 1 mi

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

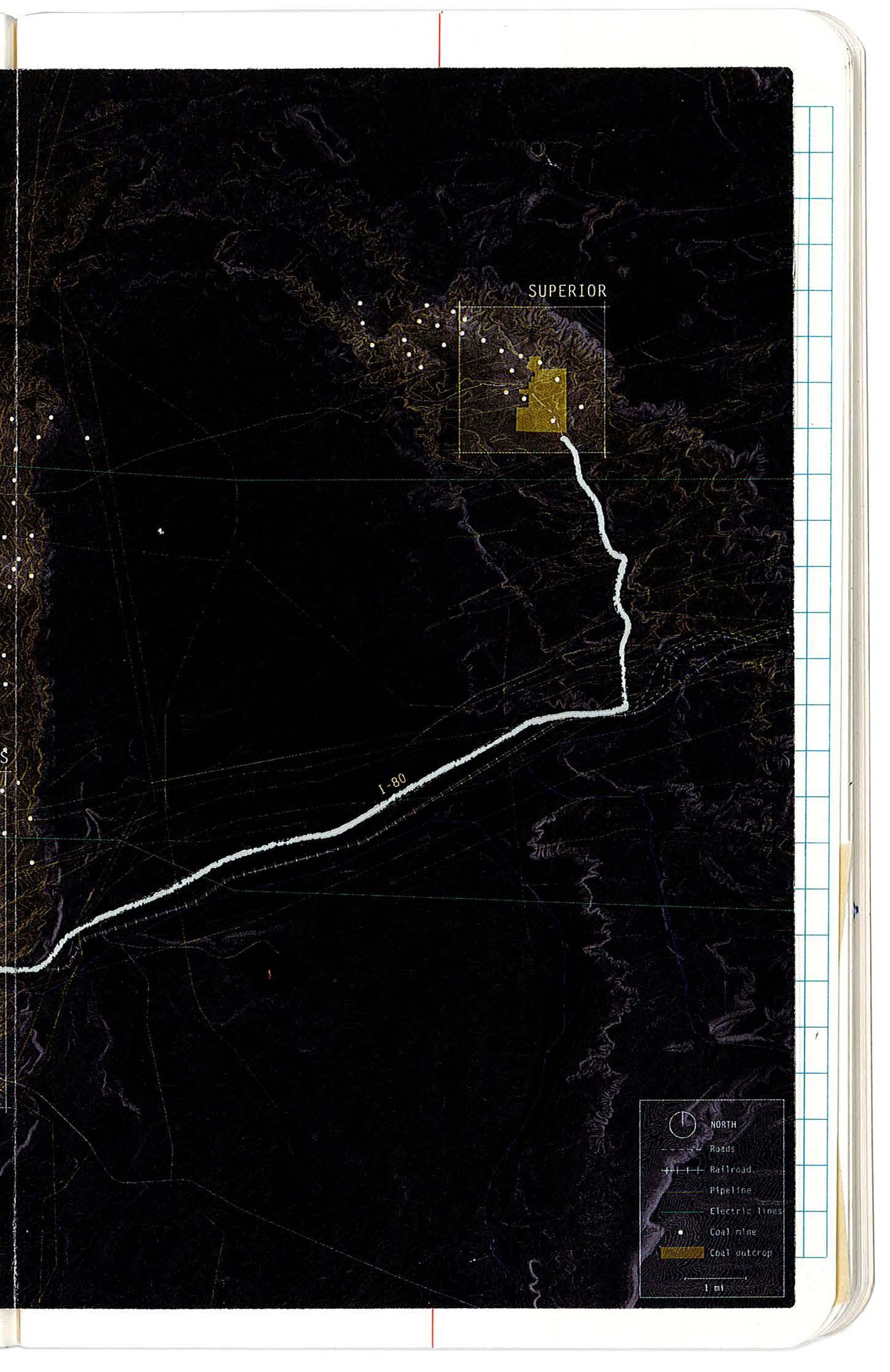

SUBSURFACE PLAN OF SUPERIOR AND ROCK SPRINGS COAL DEPOSITS, COAL MINE ENTRYWAYS, AND PIPELINE INFRASTRUCTURE

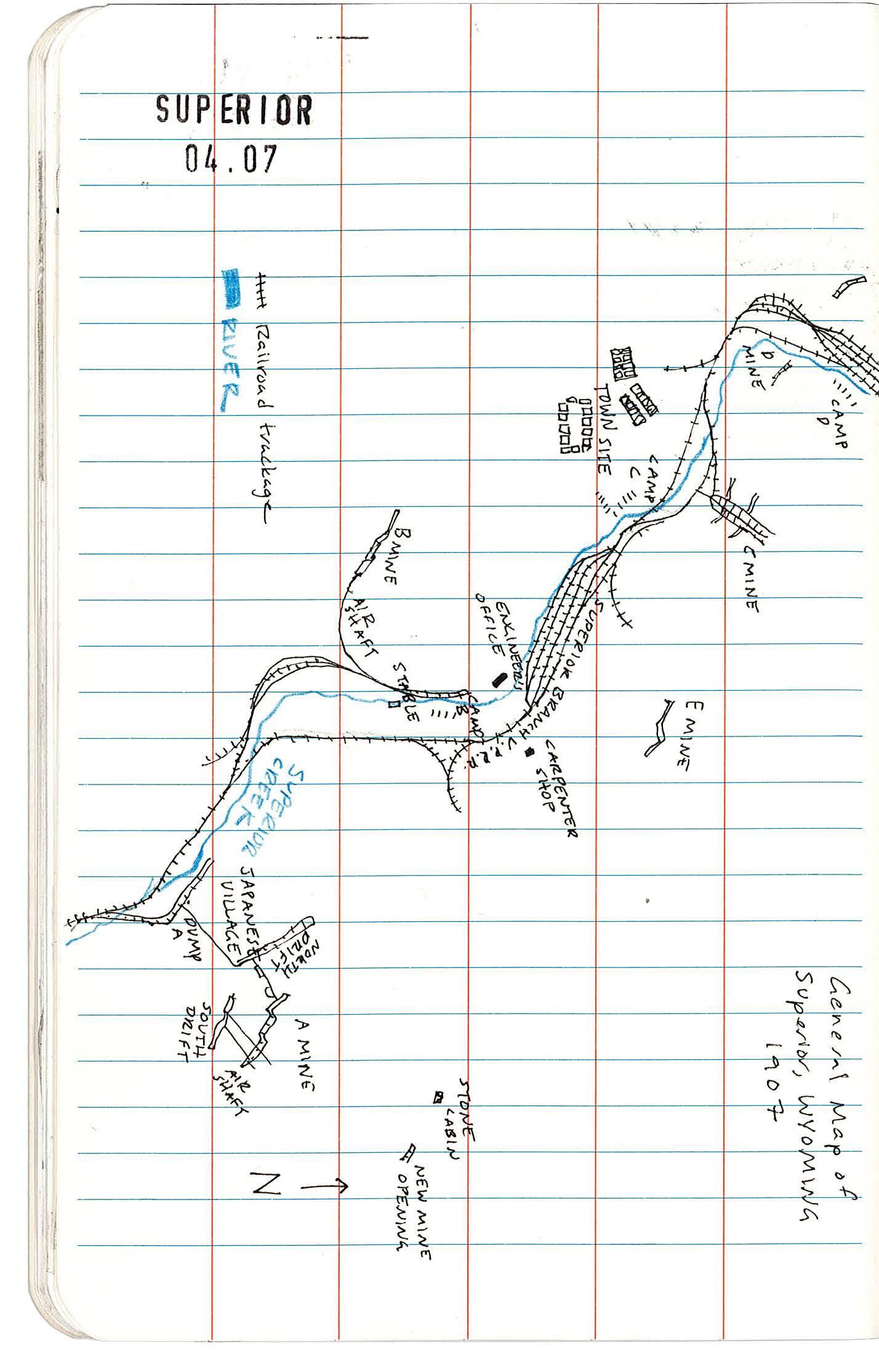

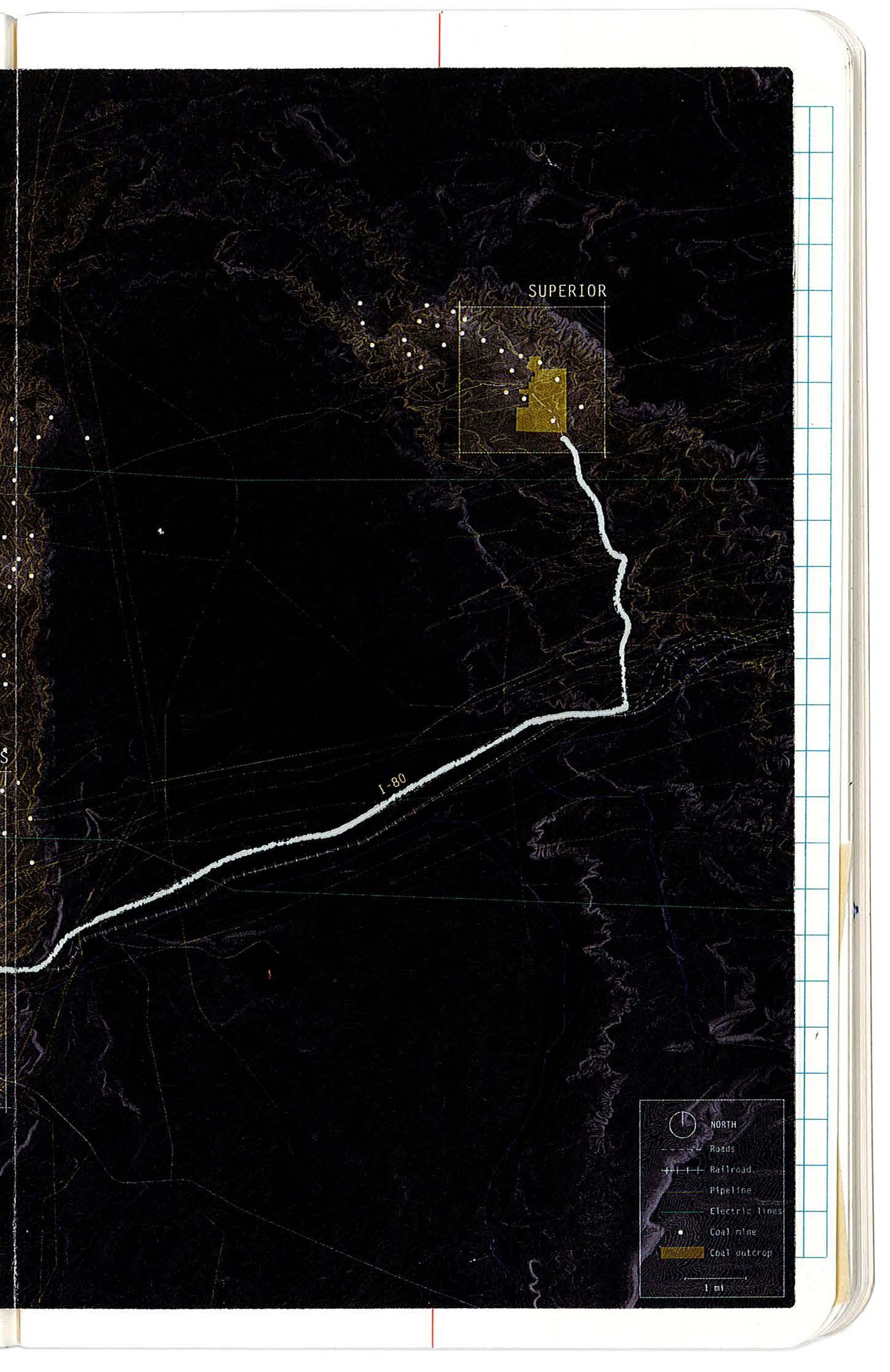

Superior and Rock Springs are historic coal, oil, and gas towns whose livelihood, culture, and economic dependency depend on the extraction industry. A band of surficial coal outcrops connects Superior and Rock Springs geologically, while pipelines, a rail road, and I-80 connect these energy towns to other urban centers.

71

VI Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes

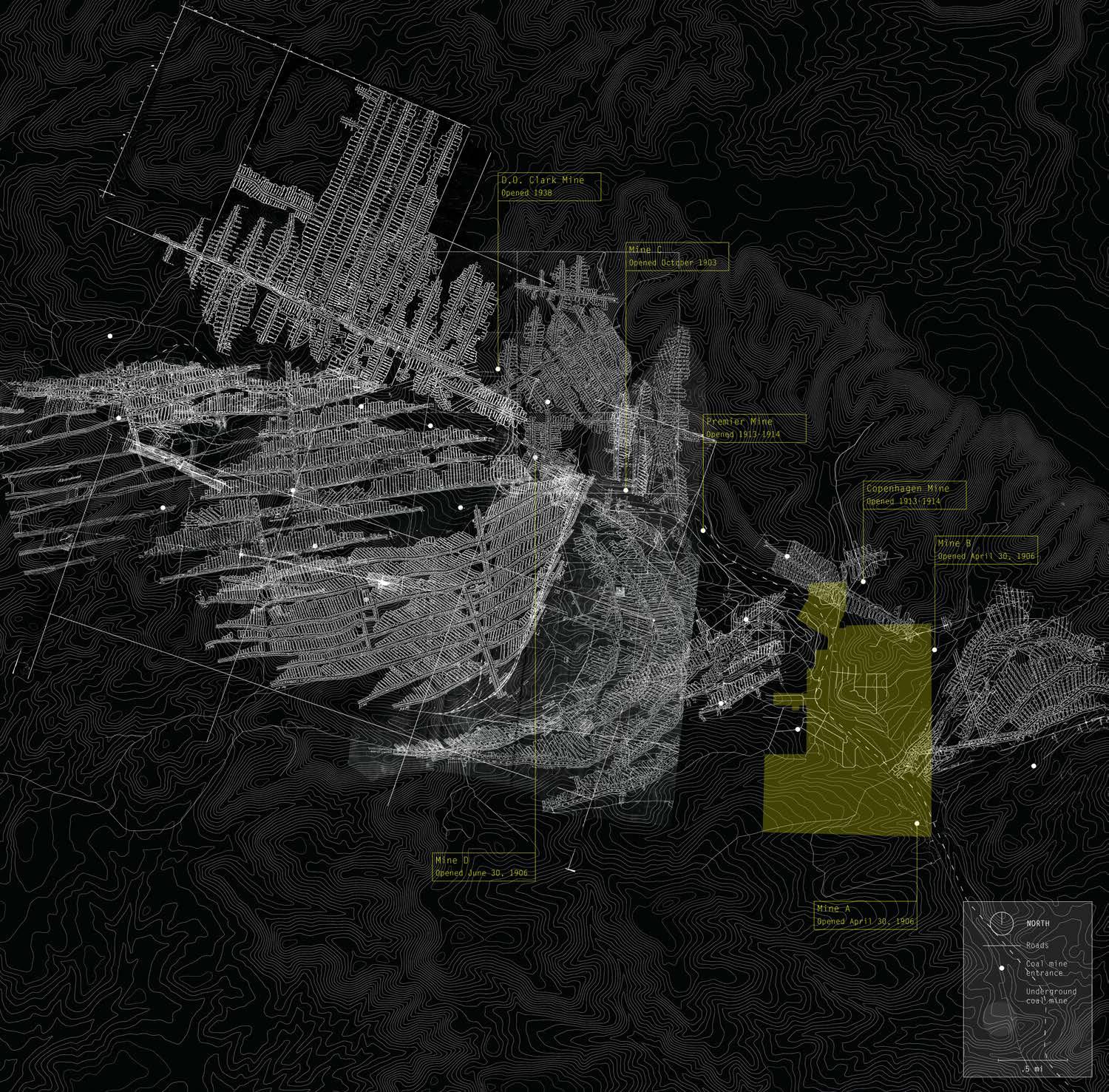

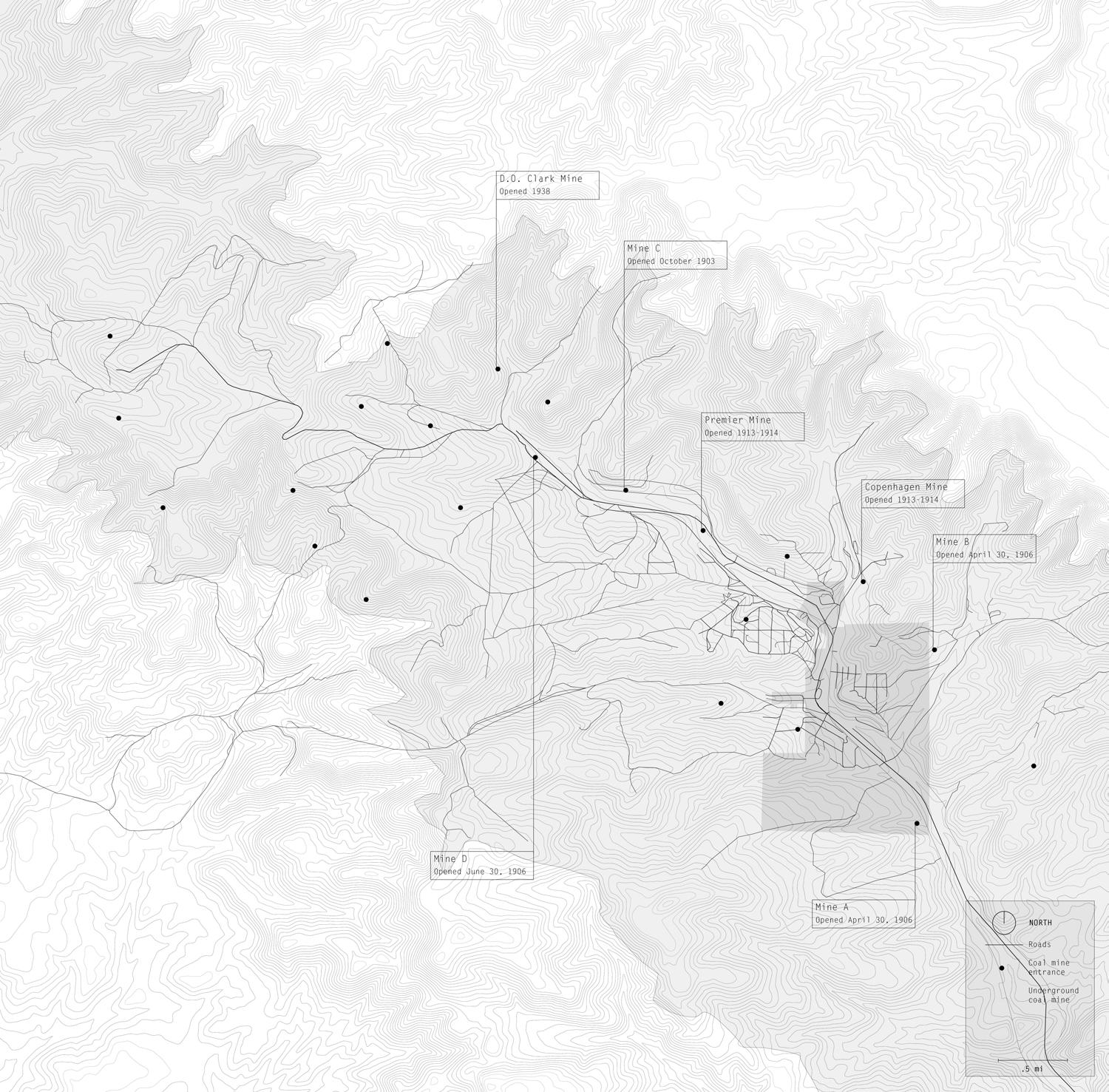

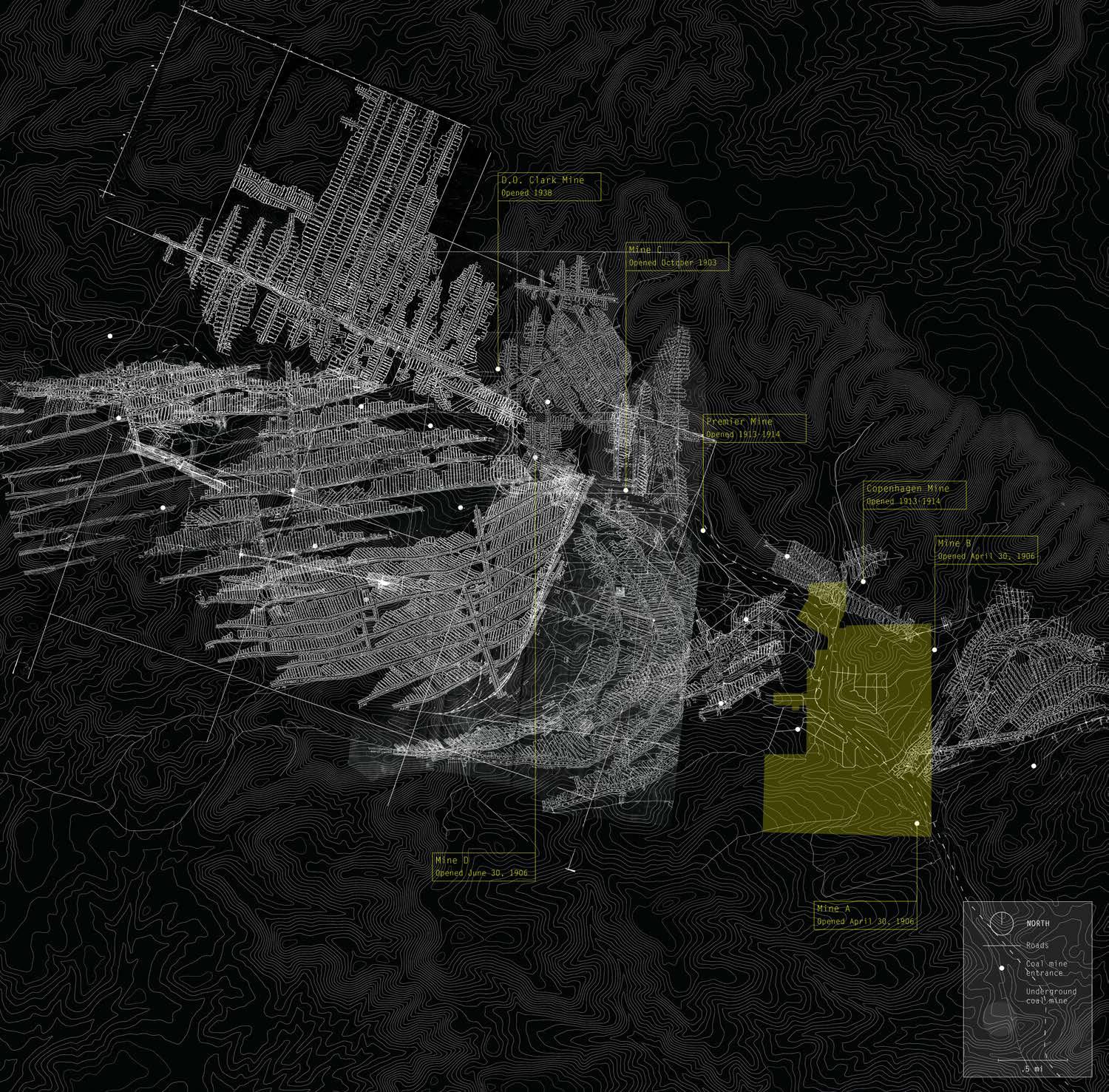

Historic maps from Sweetwater County Historical Museum and State of Wyoming Department of Natural Resources: Abandoned Mine Land Division

72 -100

.5 mi

ft

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

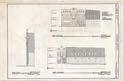

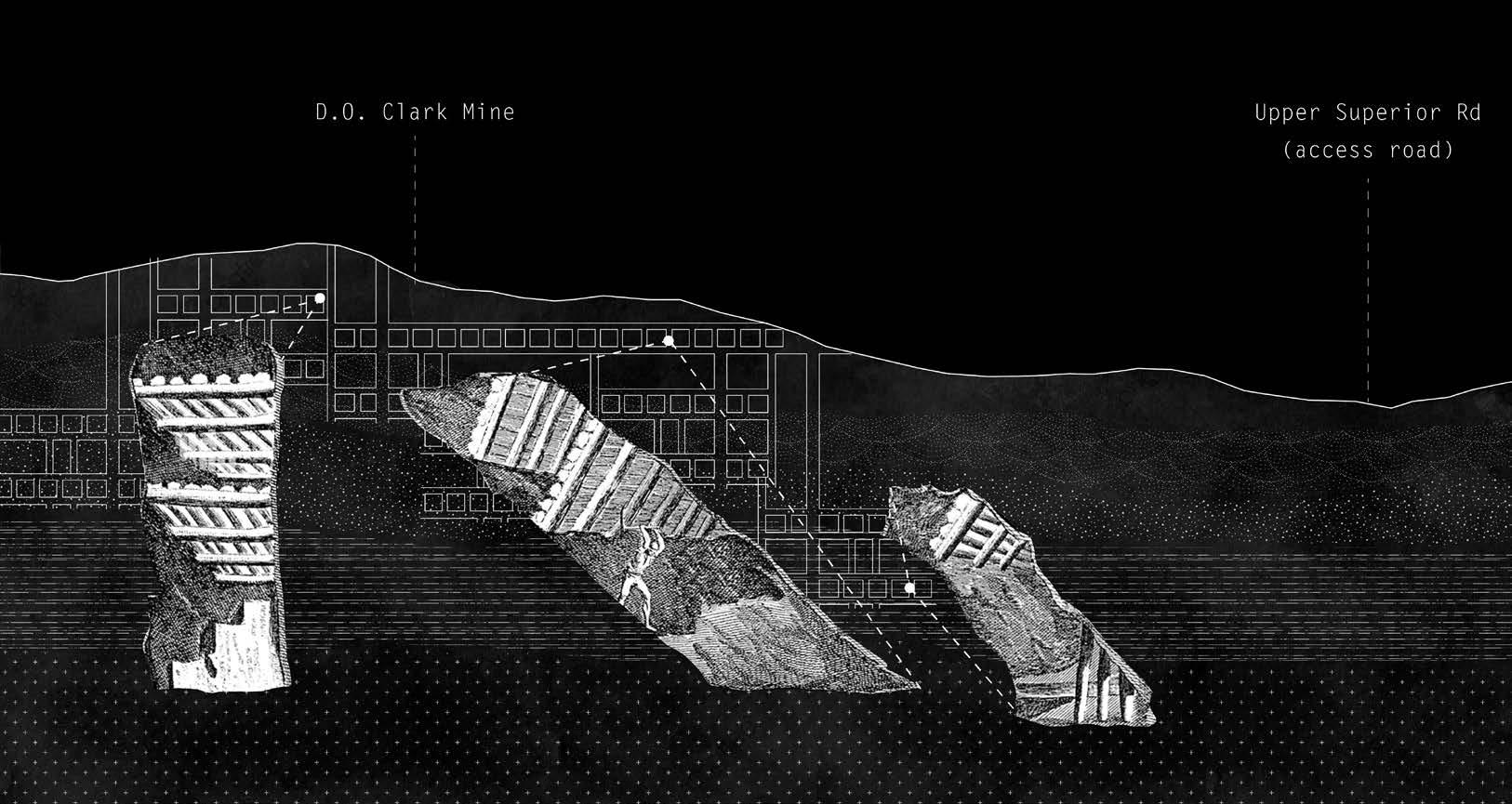

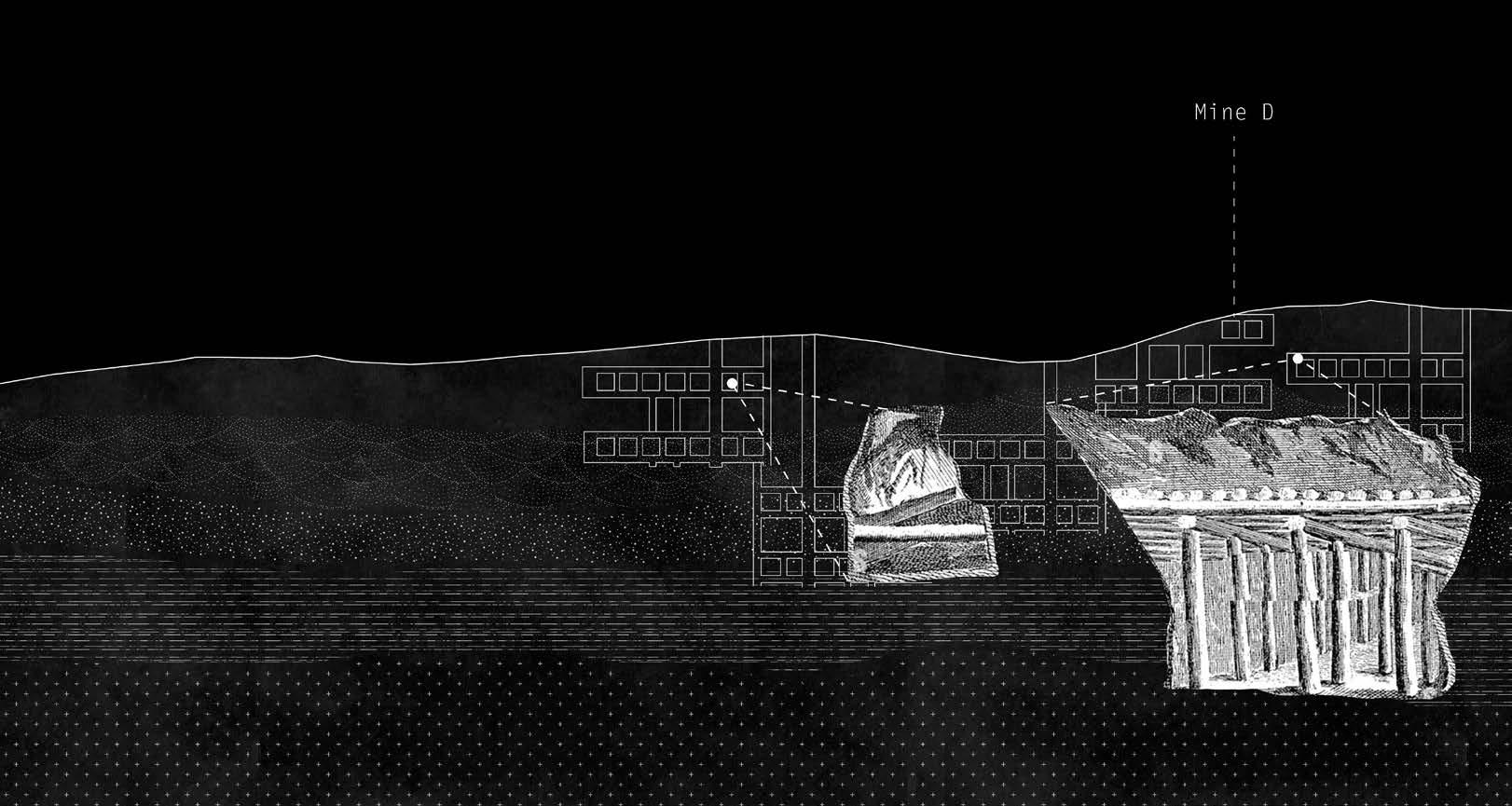

SUBSURFACE COMPOSITE OF AVAILABLE HISTORIC SUPERIOR MINE MAPS

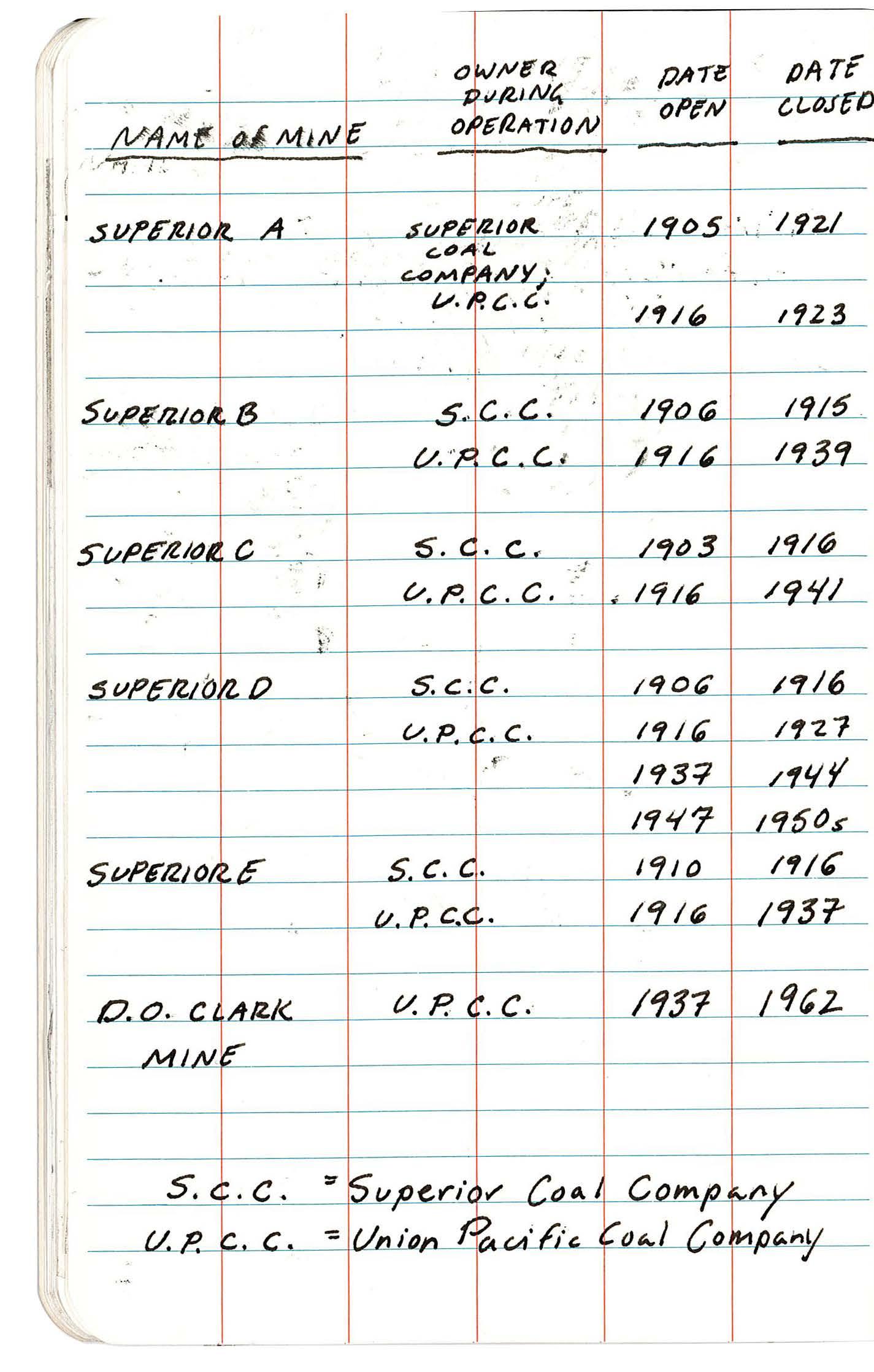

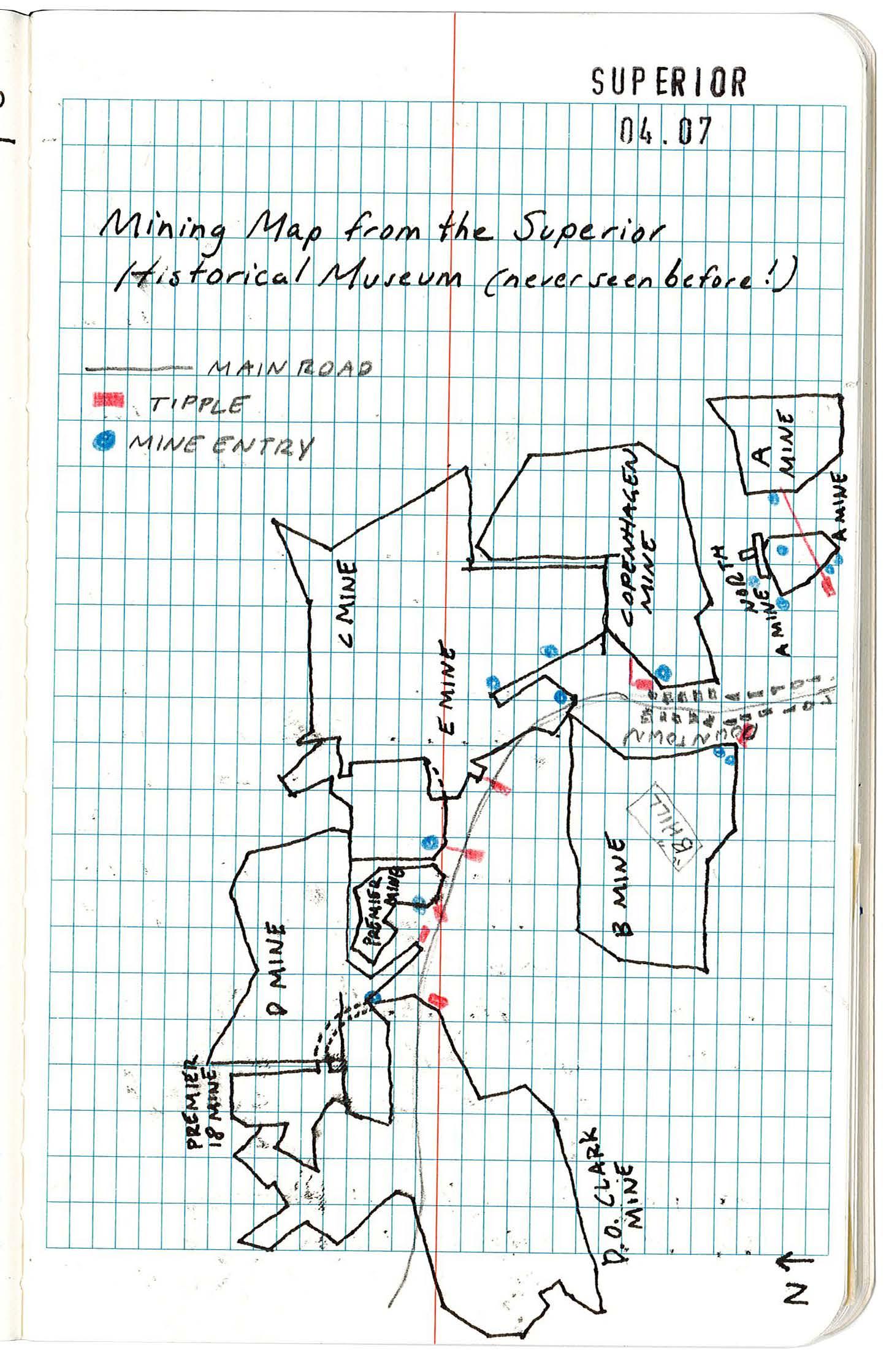

The mine network surrounding Superior is about seven times the size of the town itself. The first mines in Superior were “C” Mine in 1903, “A” and “B” Mines in 1906, and “D” Mine later that year. In 1934, when it became evident that the coal reserves of the present Superior mines were nearing exhaustion, active prospecting commenced in the vicinity of the mines. By mid-1936, evidence indicating reserves of 40,000,000 tons of coal justified the opening of a new mine of large capacity. The largest mine in Superior, D.O. Clark mine, opened in 1938.

73

VI Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes

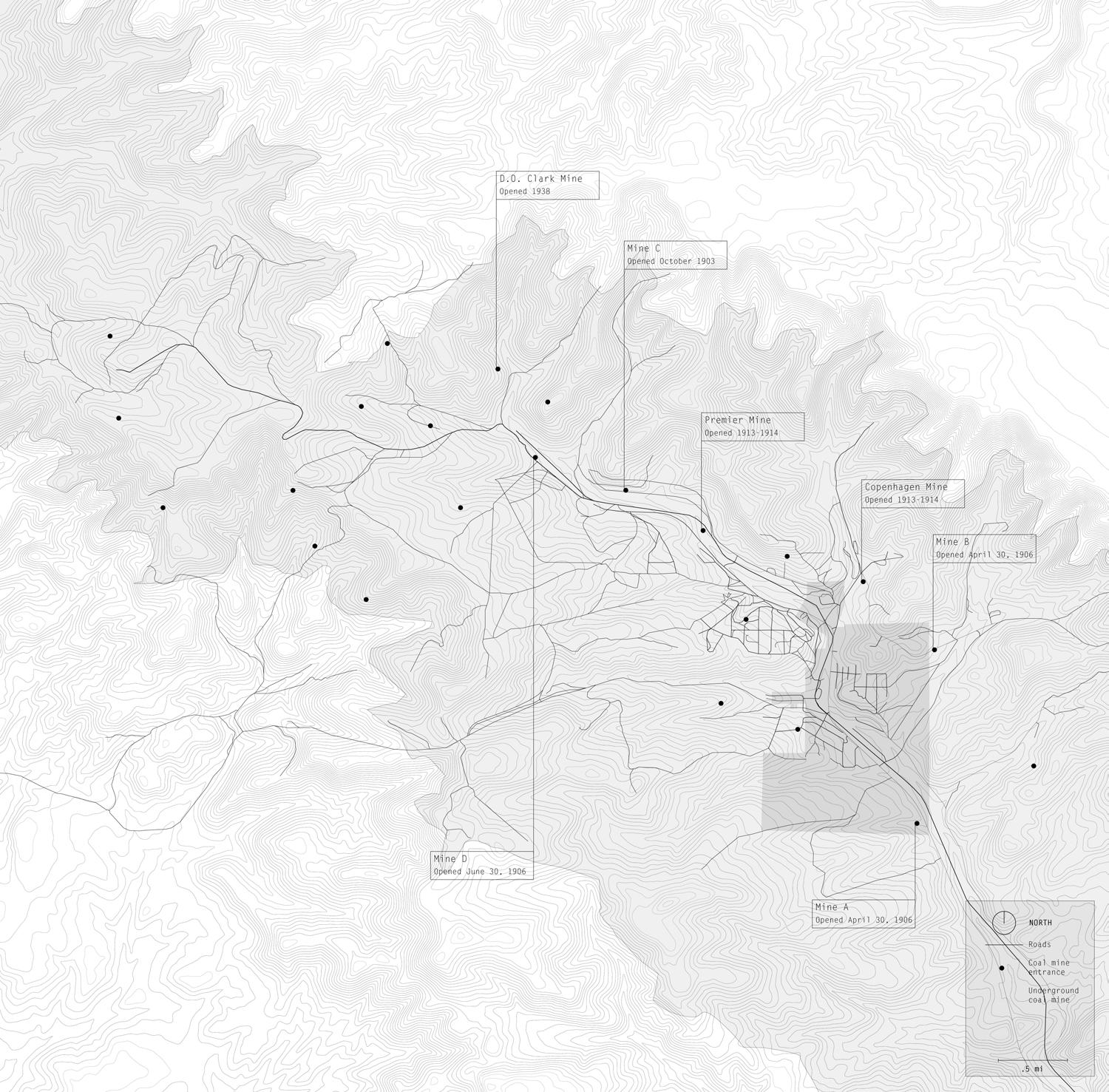

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

Historic maps from Sweetwater County Historical Museum and State of Wyoming Department of Natural Resources: Abandoned Mine Land Division

74 +0 ft

.5 mi

SURFICIAL PLAN OF SUPERIOR SHOWING PRESENT DAY RELATIONSHIP OF DOWNTOWN WITH ABANDONED COAL MINES

75

VI Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

Historic maps from Sweetwater County Historical Museum and State of Wyoming Department of Natural Resources: Abandoned Mine Land Division

76 +0 ft

.5 mi

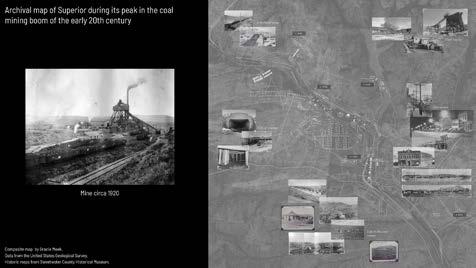

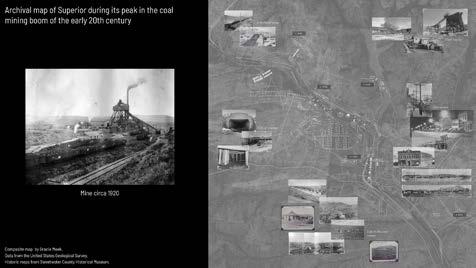

ARCHIVAL MAP OF SUPERIOR AT PEAK POPULATION DURING COAL BOOM PERIOD DOCUMENTING HISTORIC LIVELIHOOD

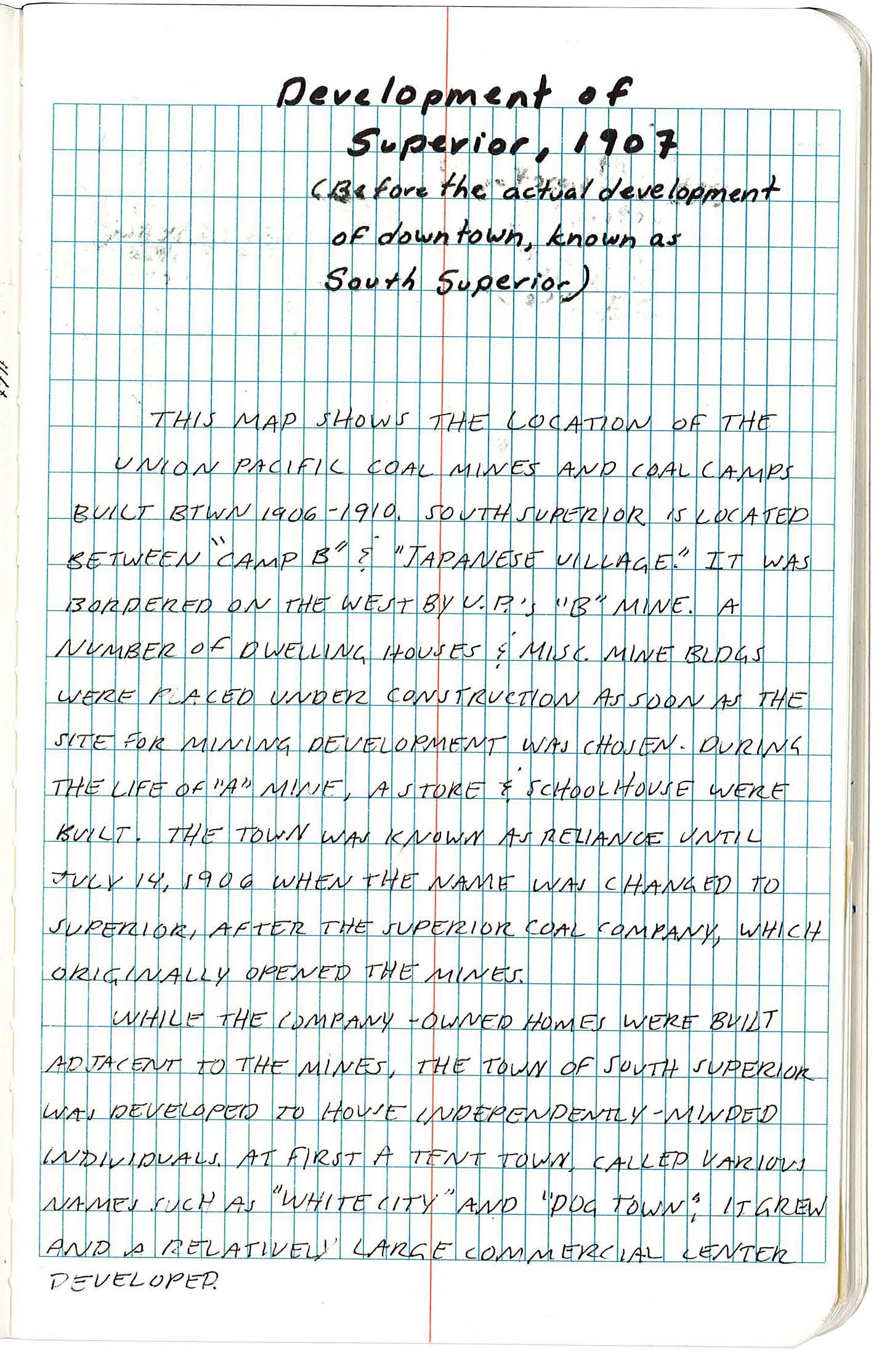

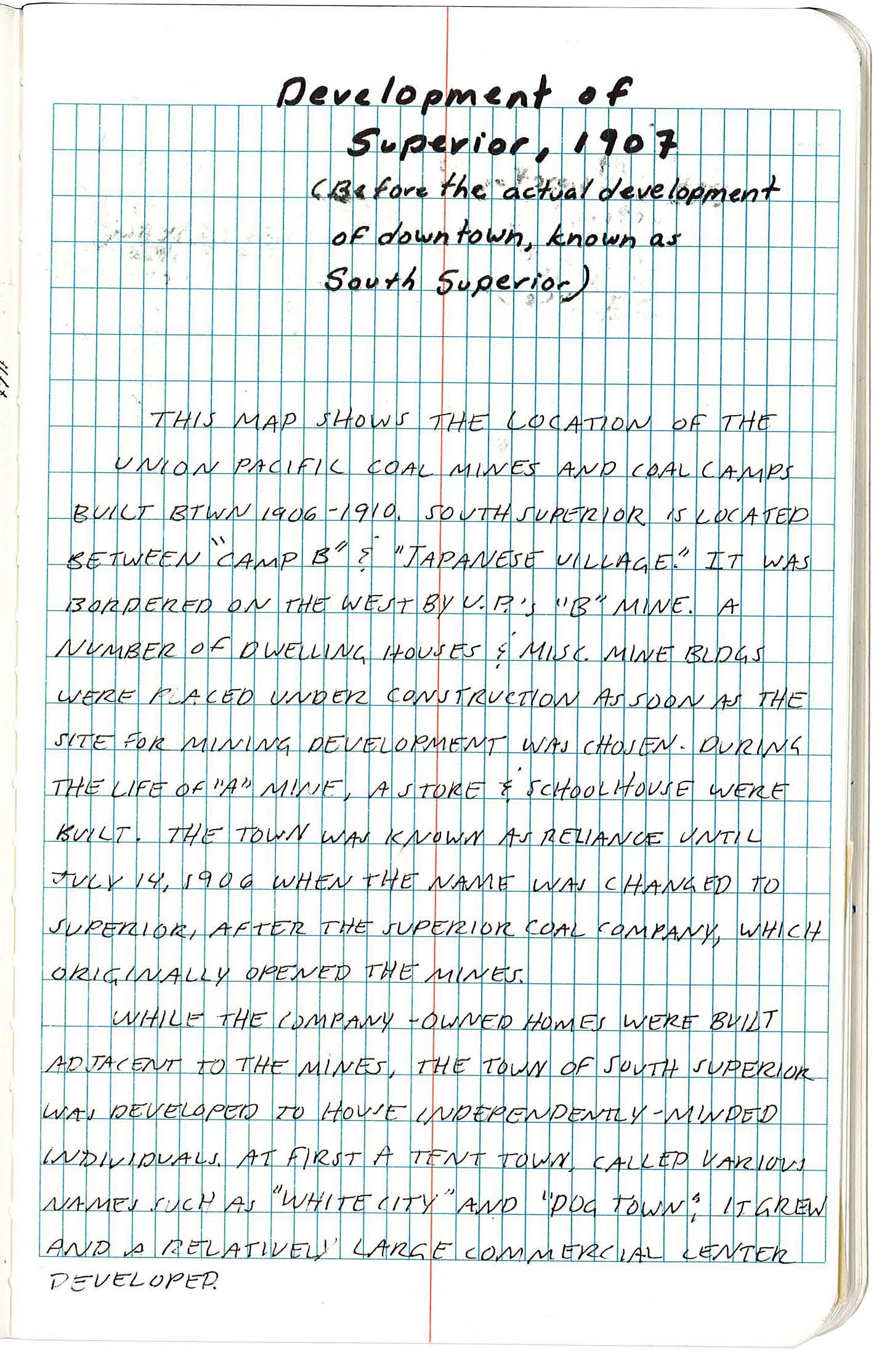

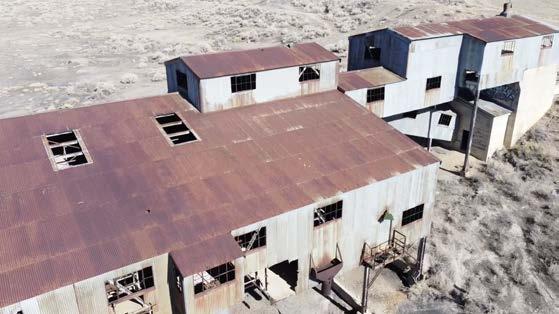

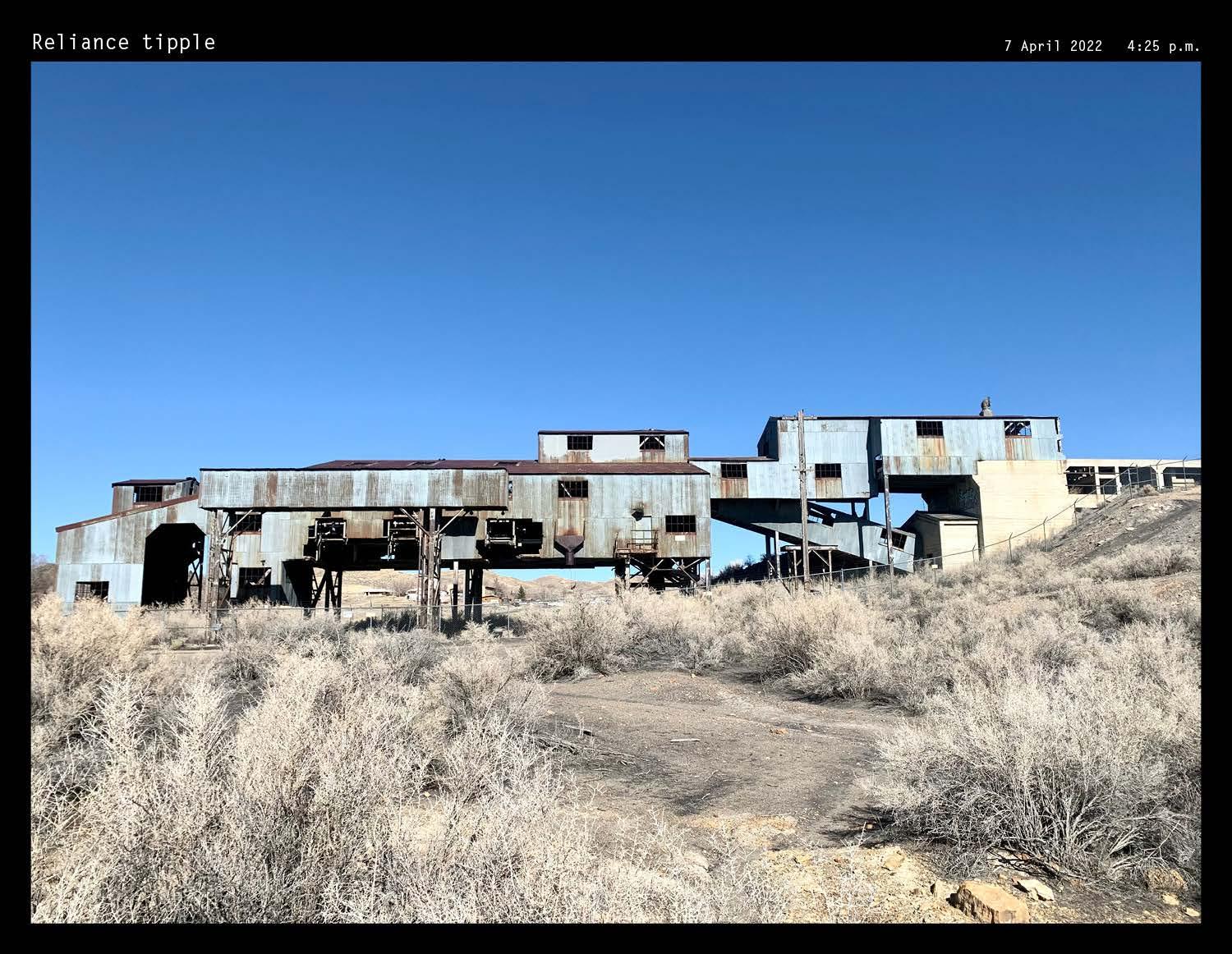

This map georeferences the location of the Union Pacific coal mines and coal camps built in the years between 1906 and 1910 with the town as it was in its heyday in the late 1940s-1950s. The town was known as Reliance until, on July 14, 1906, the name was changed to Superior, after the Superior Coal Company which originally opened the mines.

In its early days, Superior was actually two towns: Superior and South Superior. While the companyowned homes were built adjacent to the mines, the town of south Superior was developed to house independentlyminded families and individuals. Aft first a tent town, called various names such as “White City” and “Dog Town”, it grew, and a relatively large commercial center developed. My grandmother, Francis Sines, grew up in Dog Town while my grandfather, William Sines, grew up in the company-owned coal homes.

77

VI Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes

78 +0 ft

1 mi

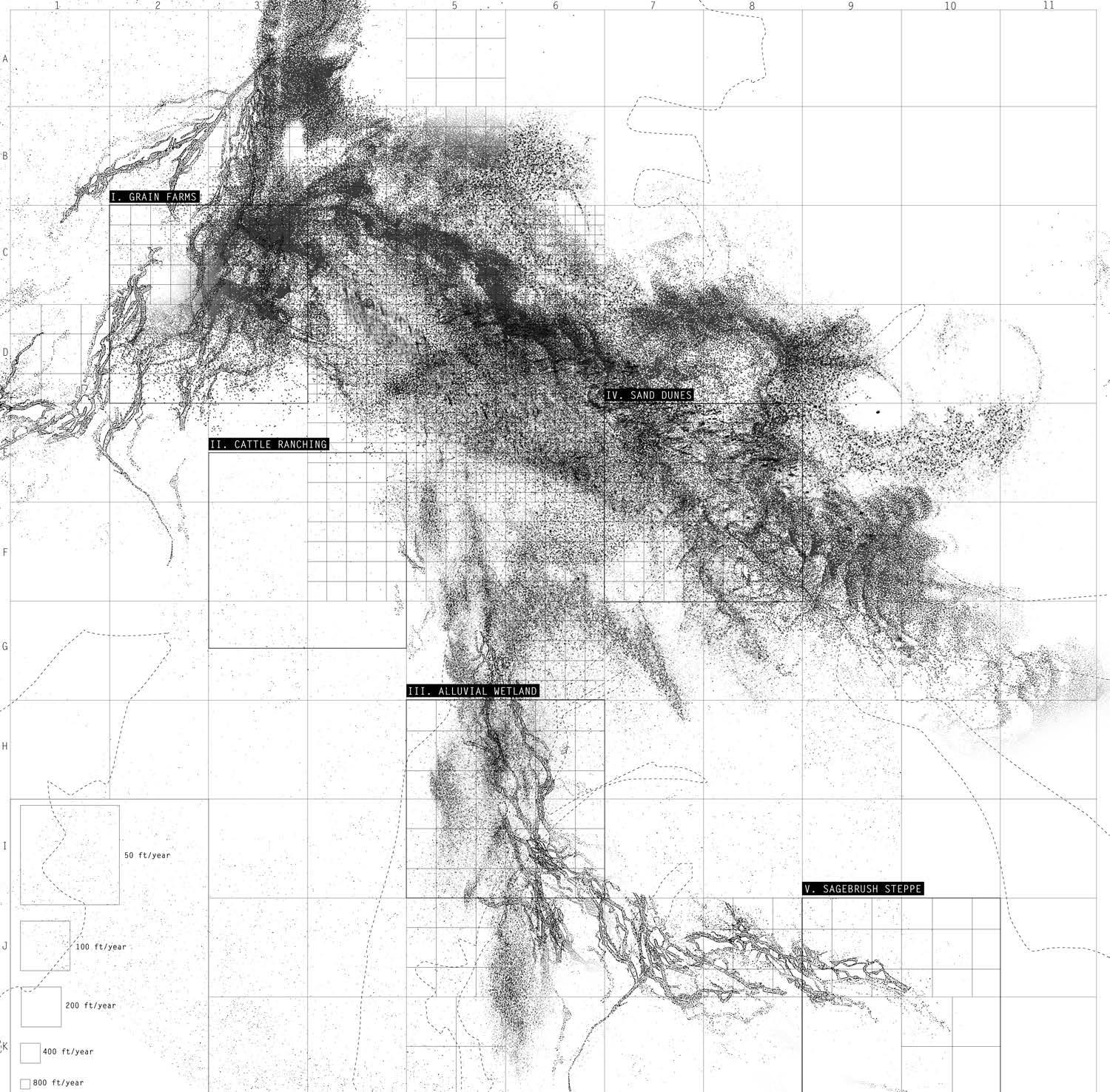

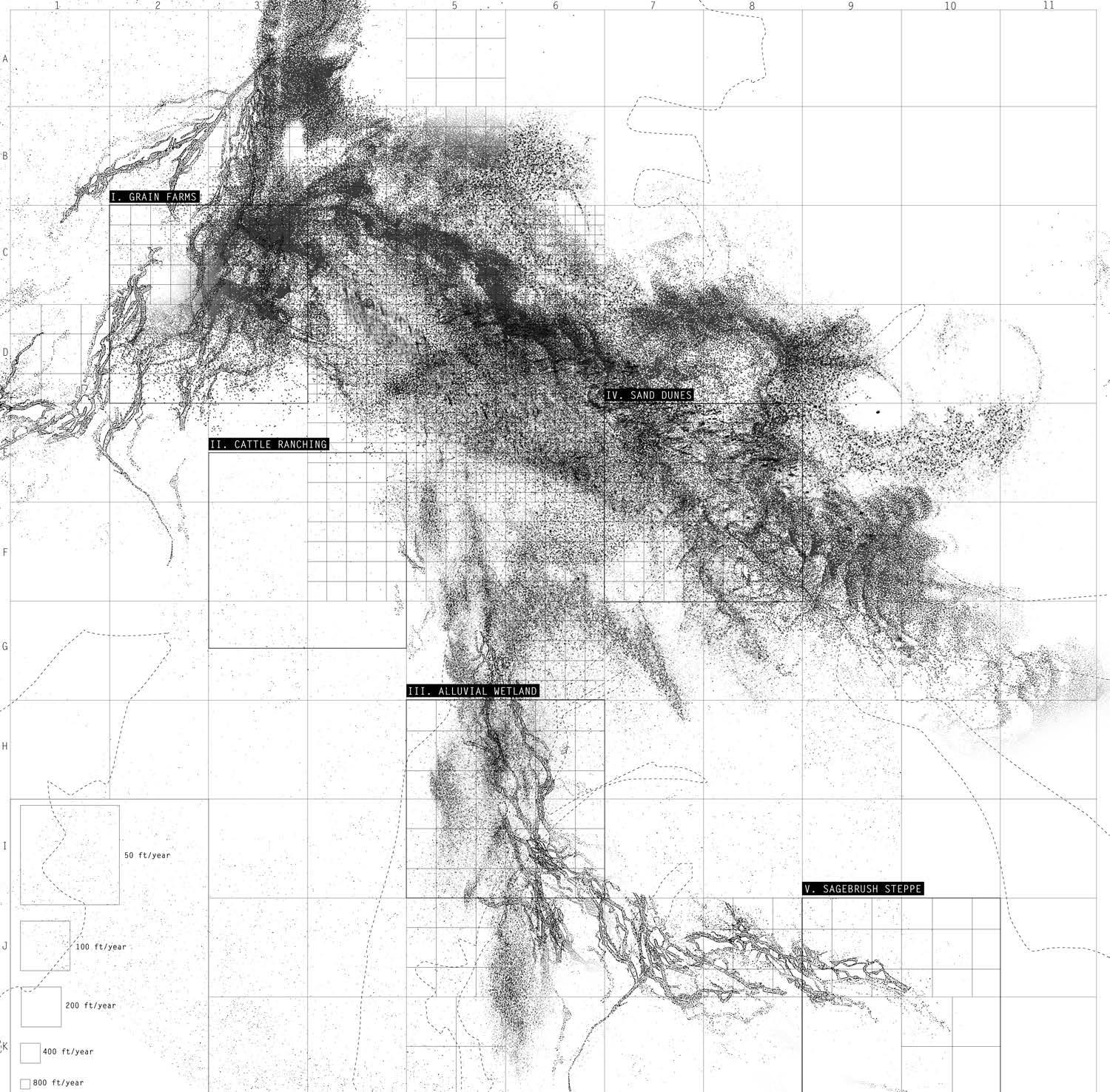

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

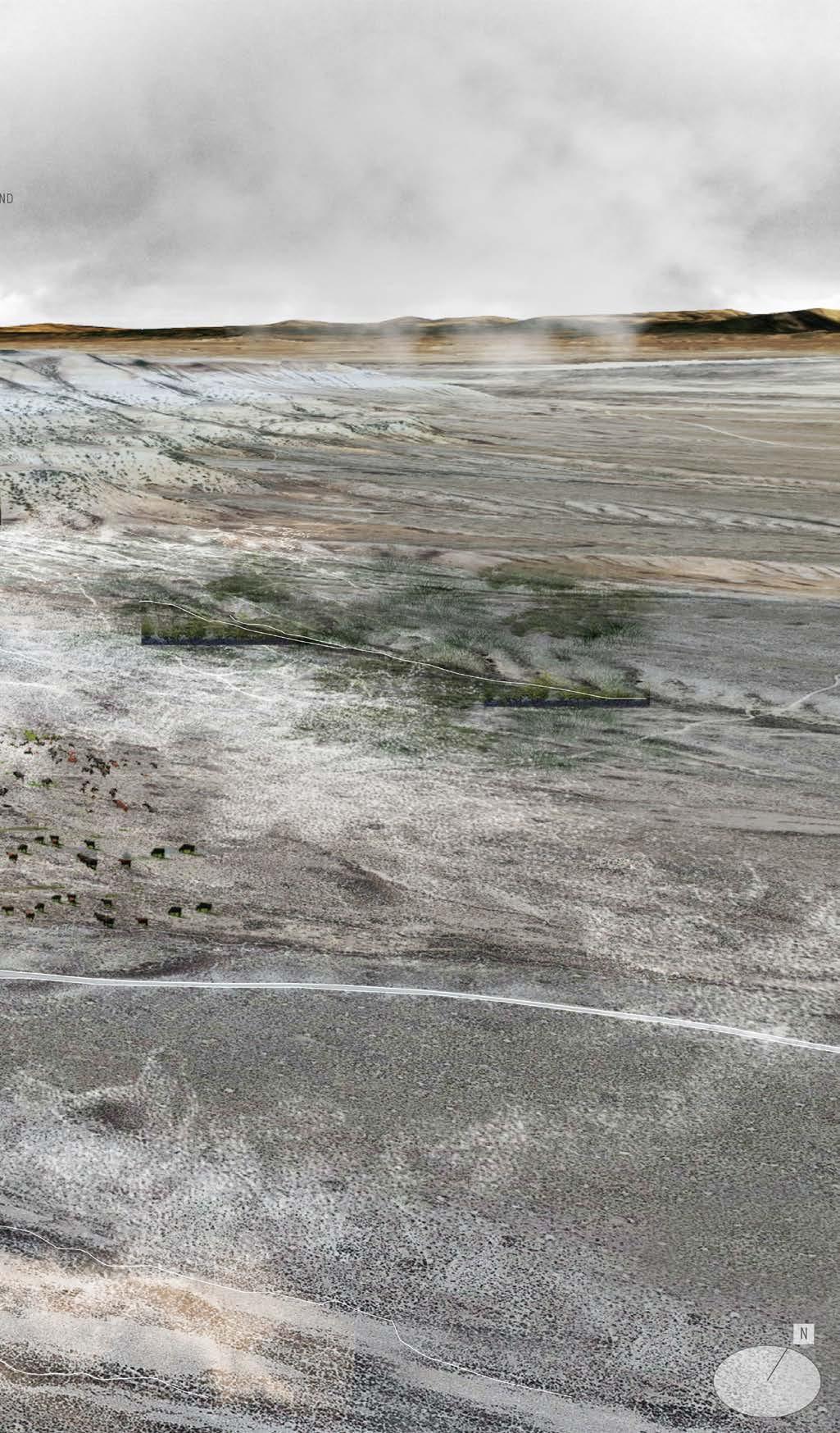

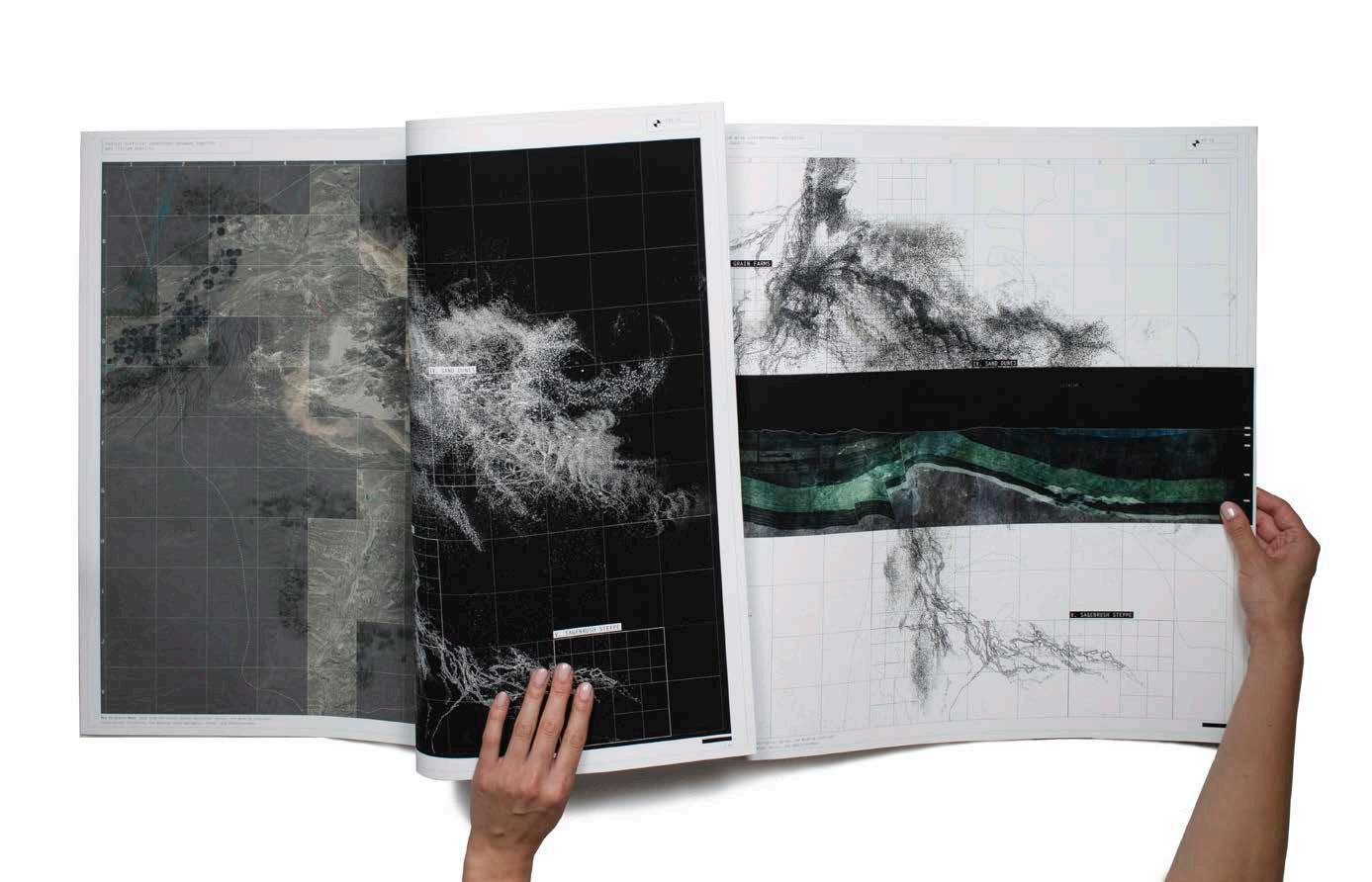

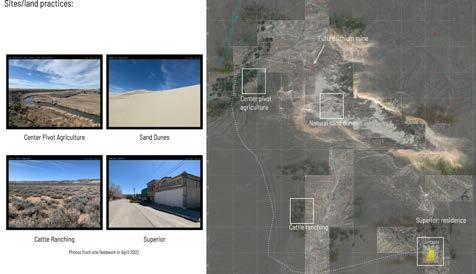

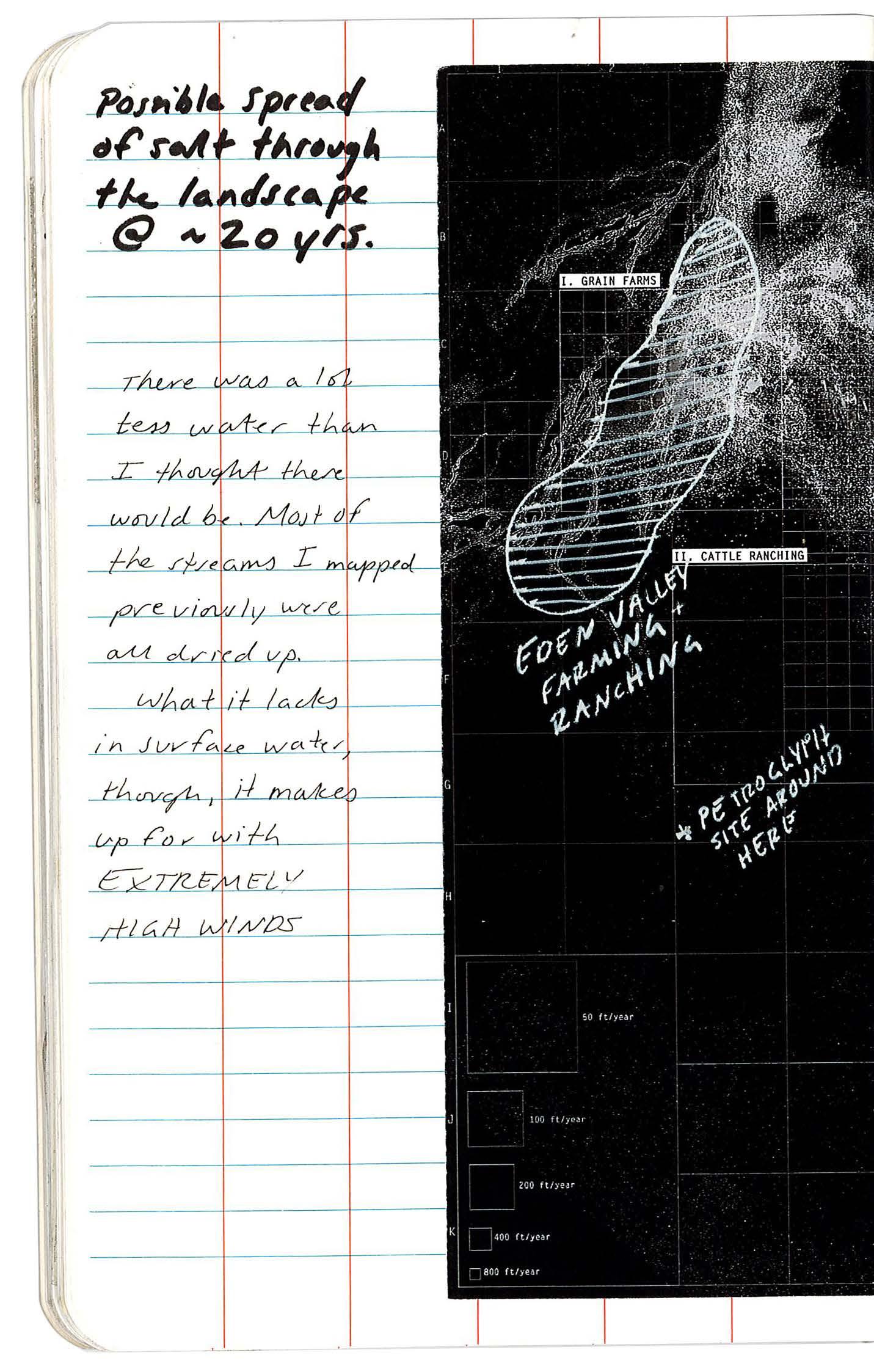

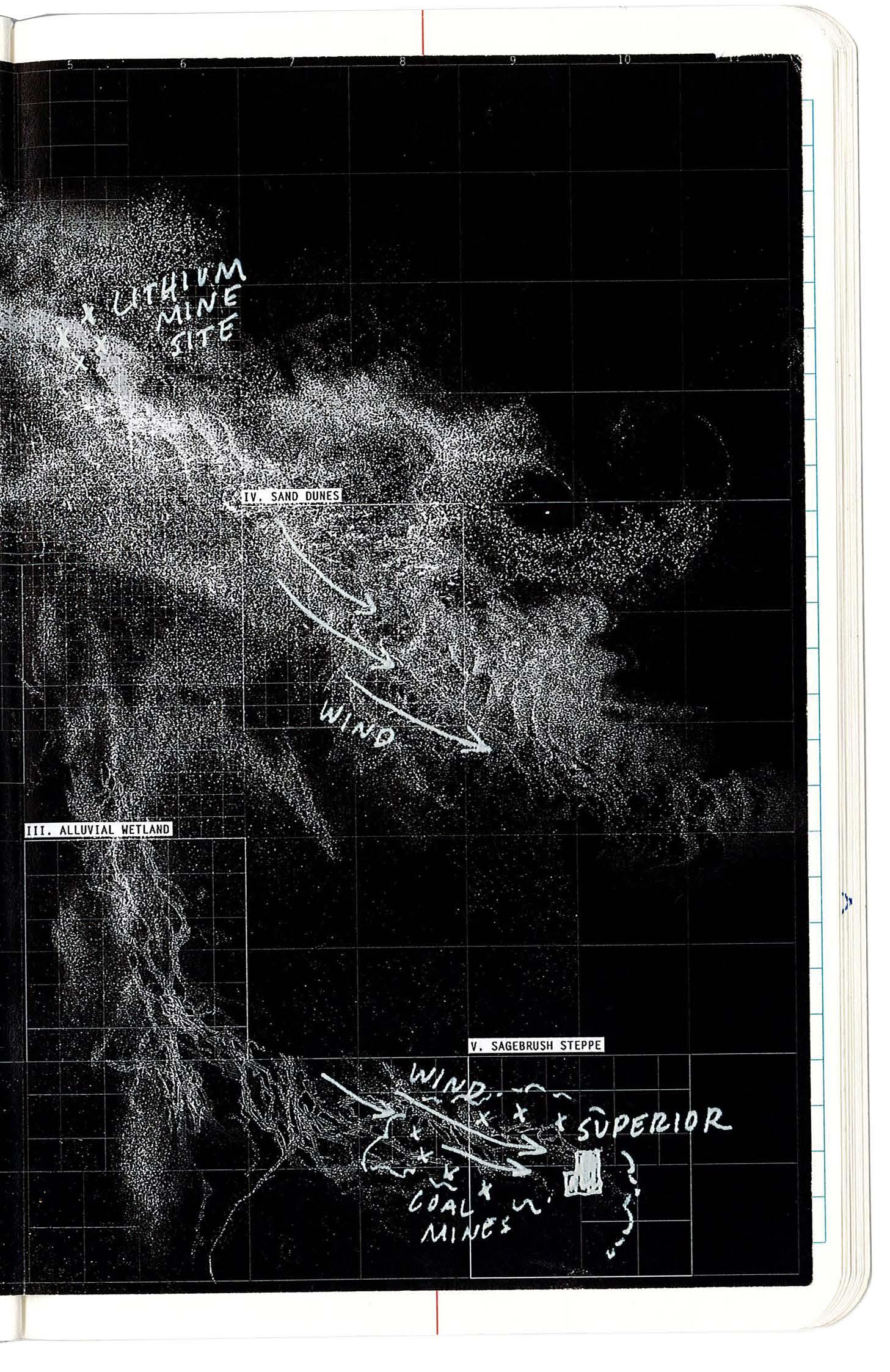

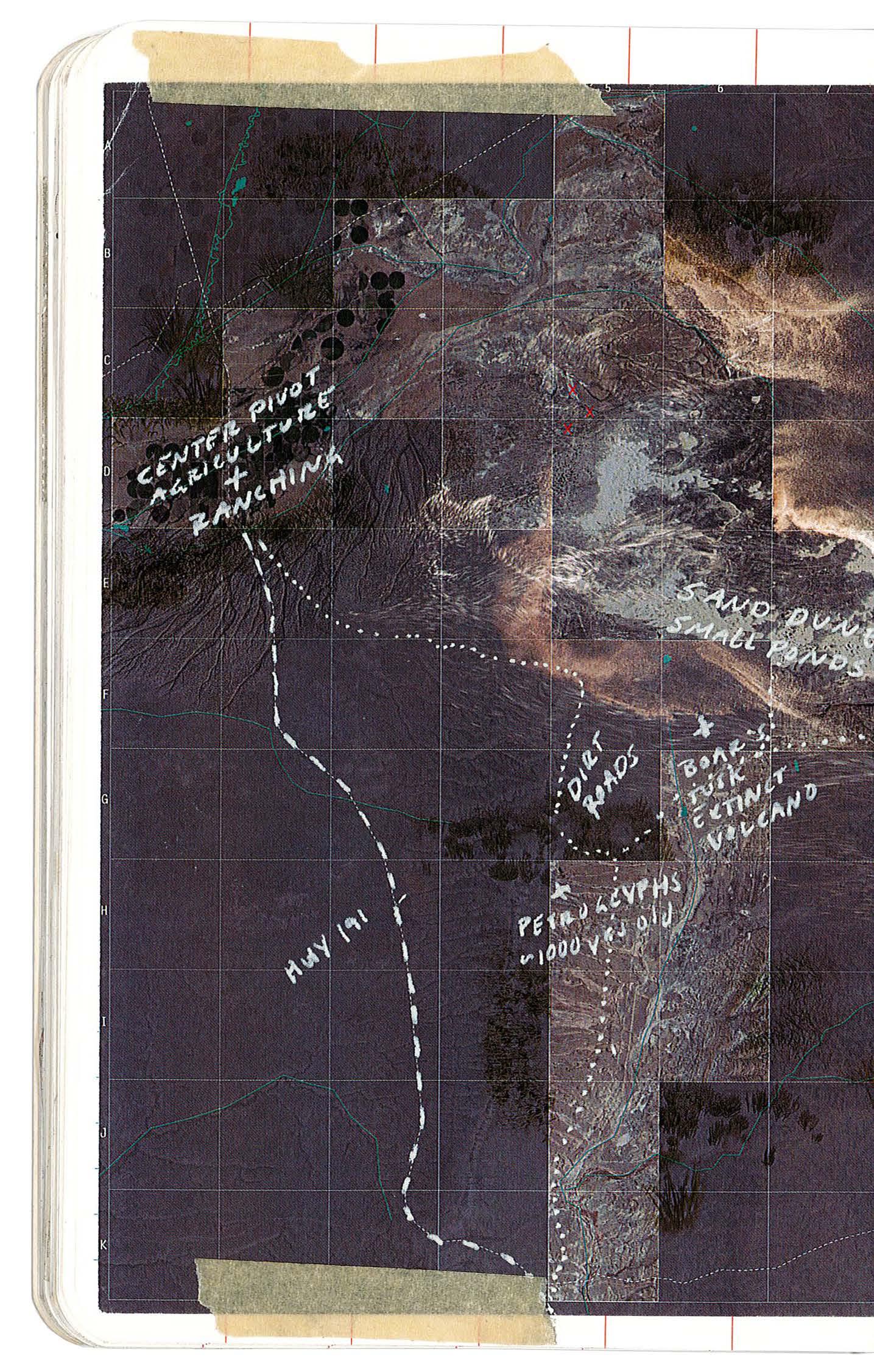

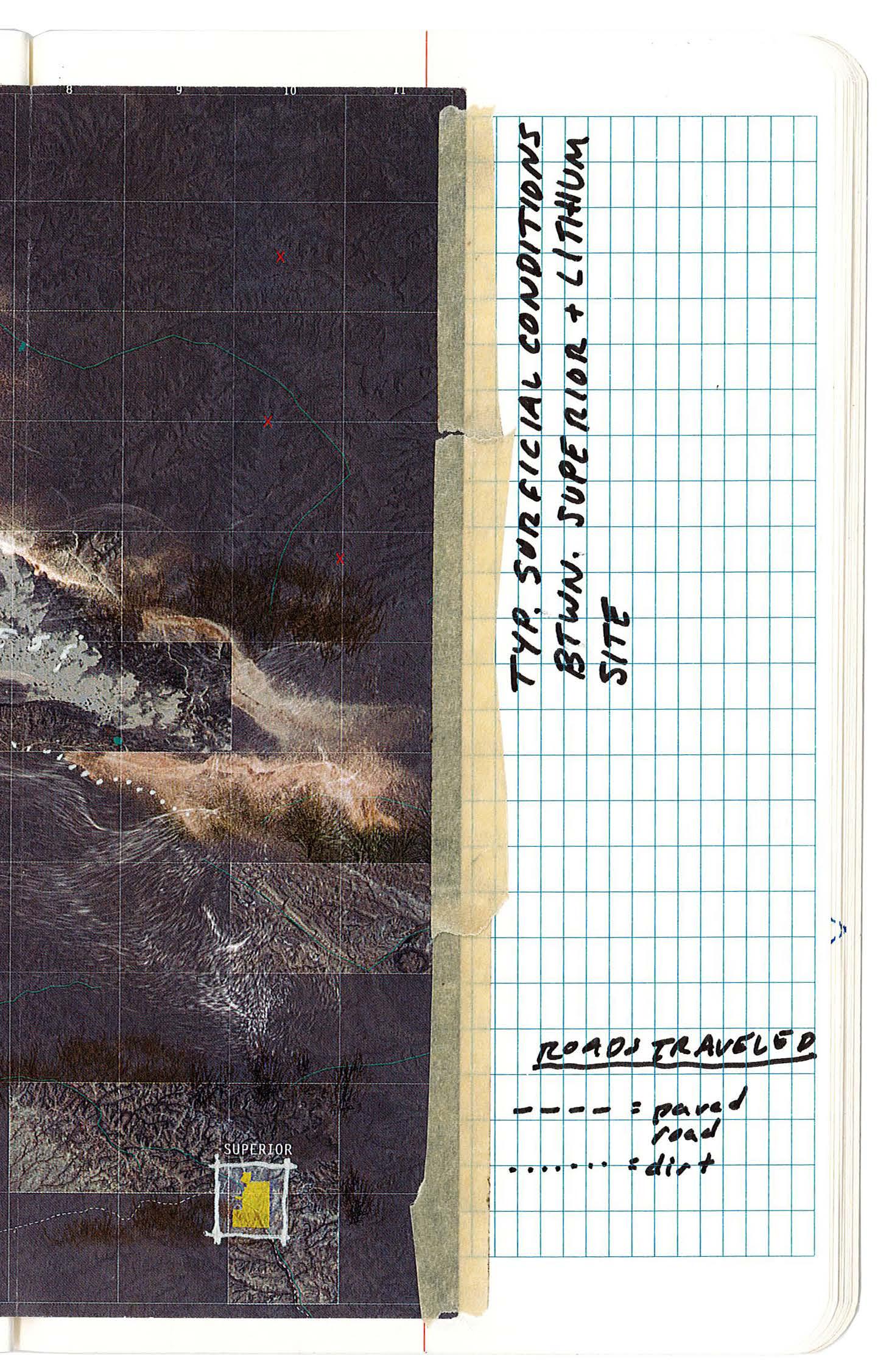

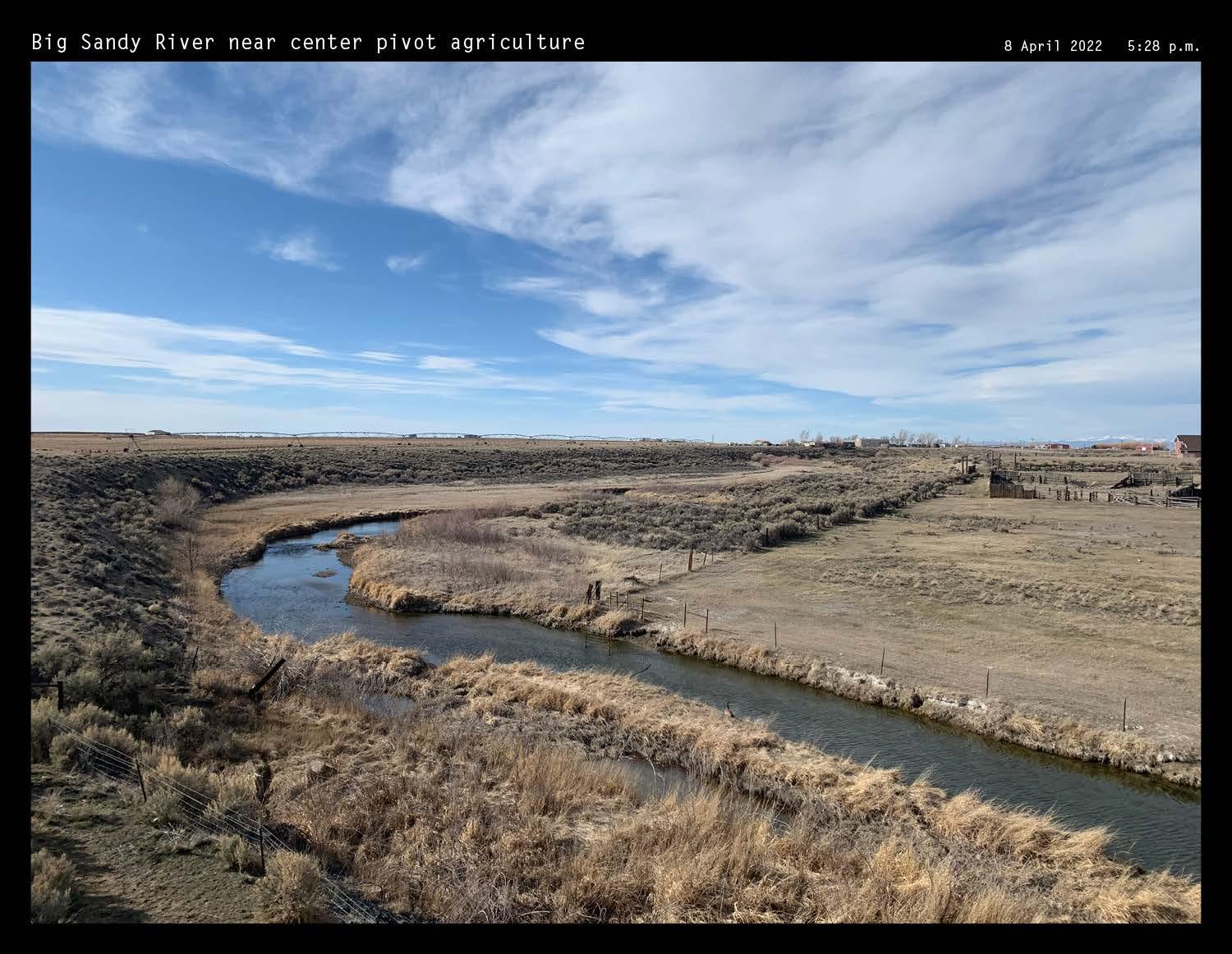

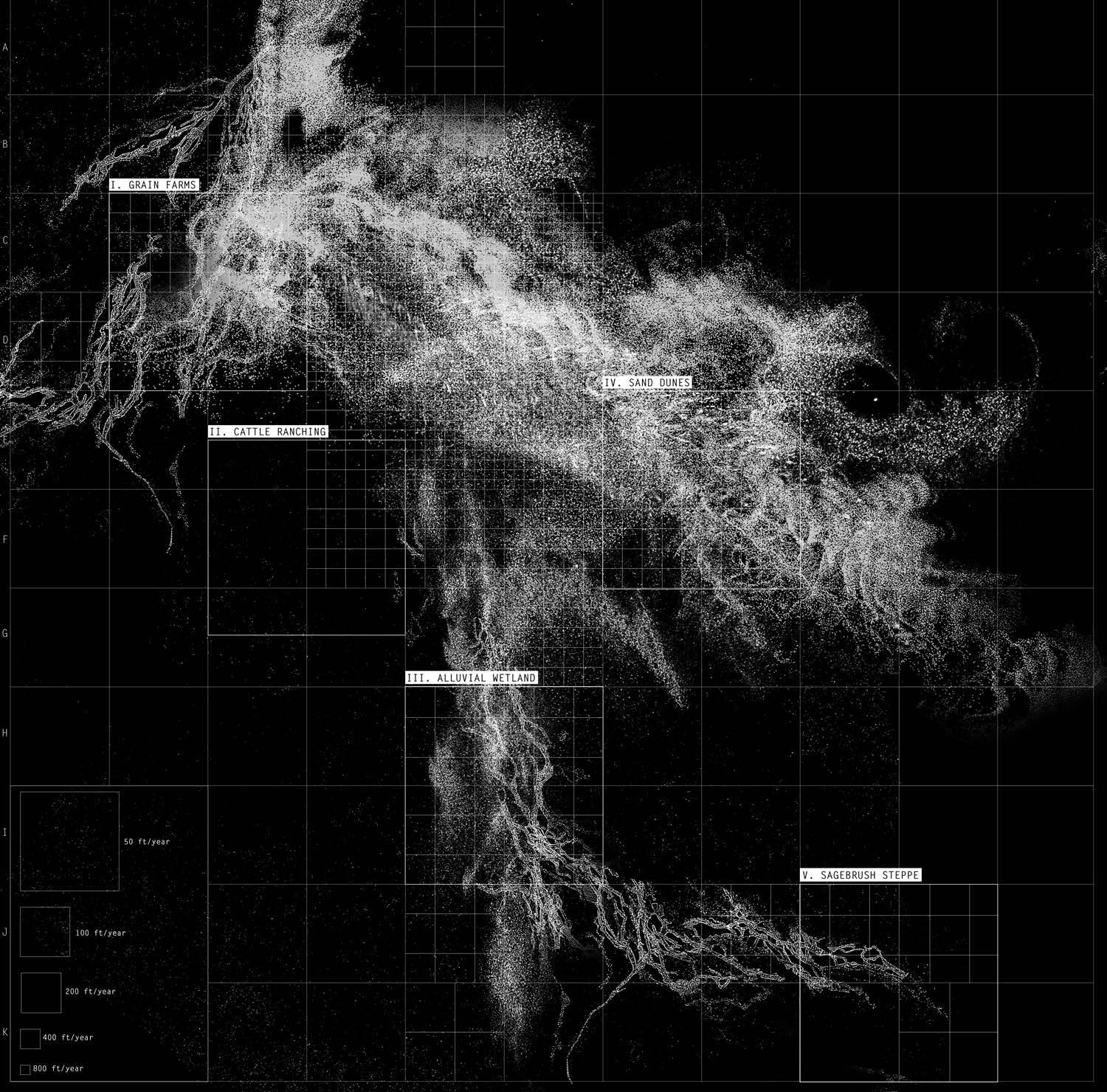

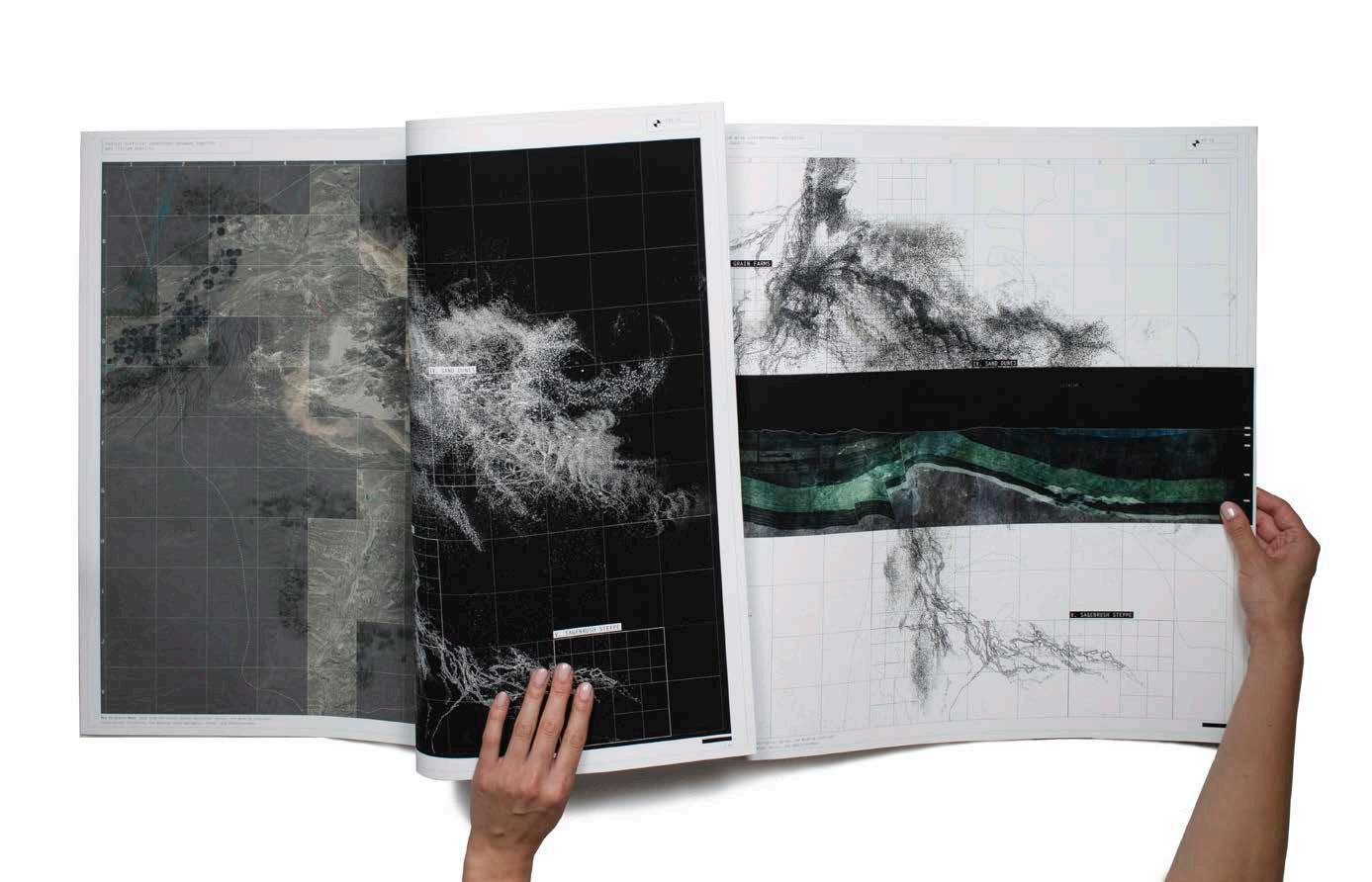

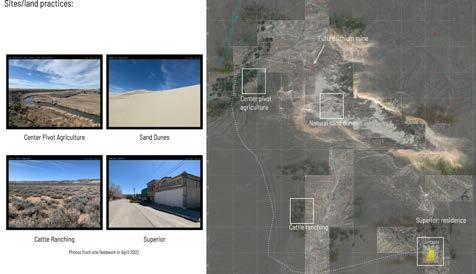

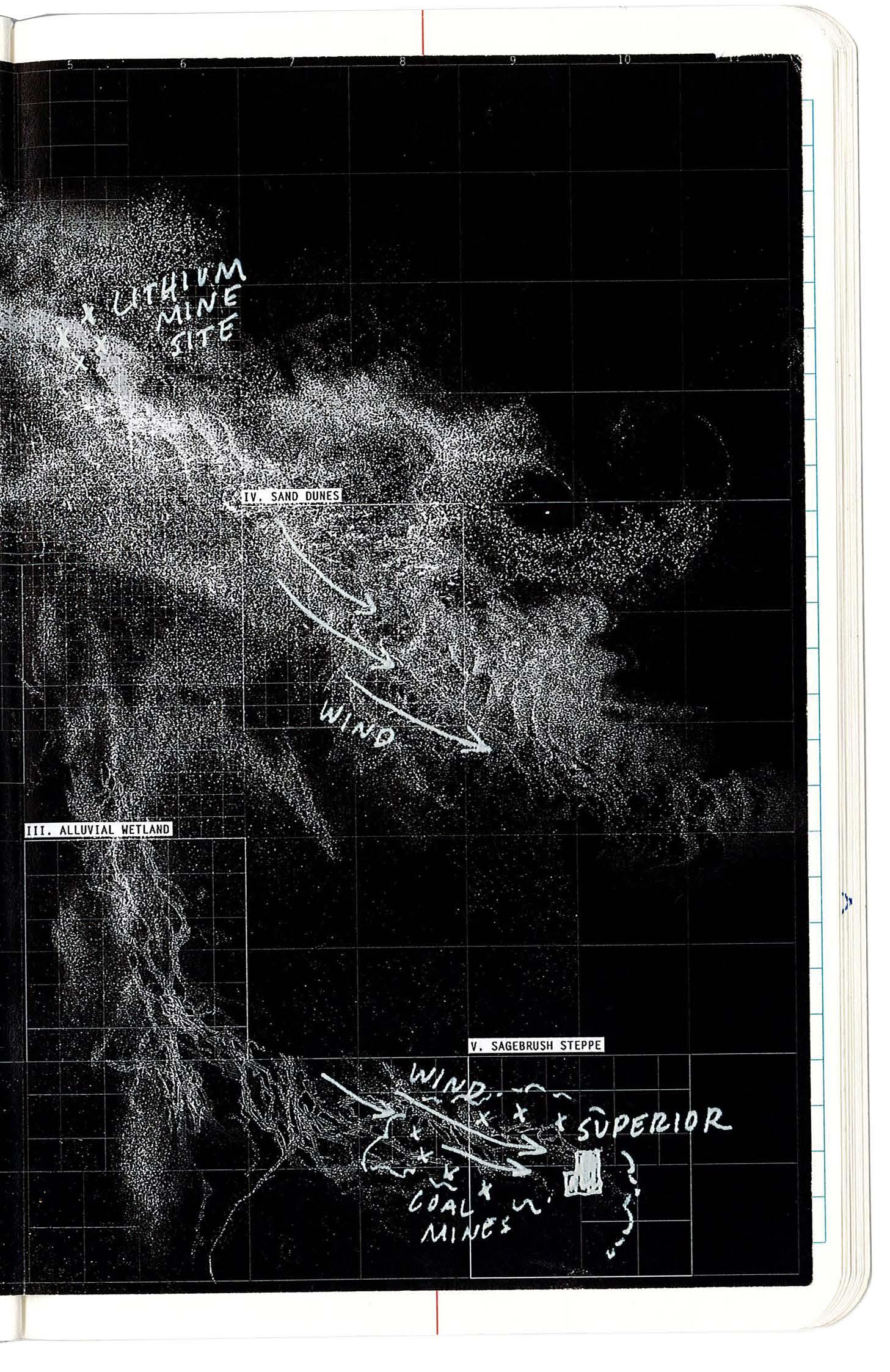

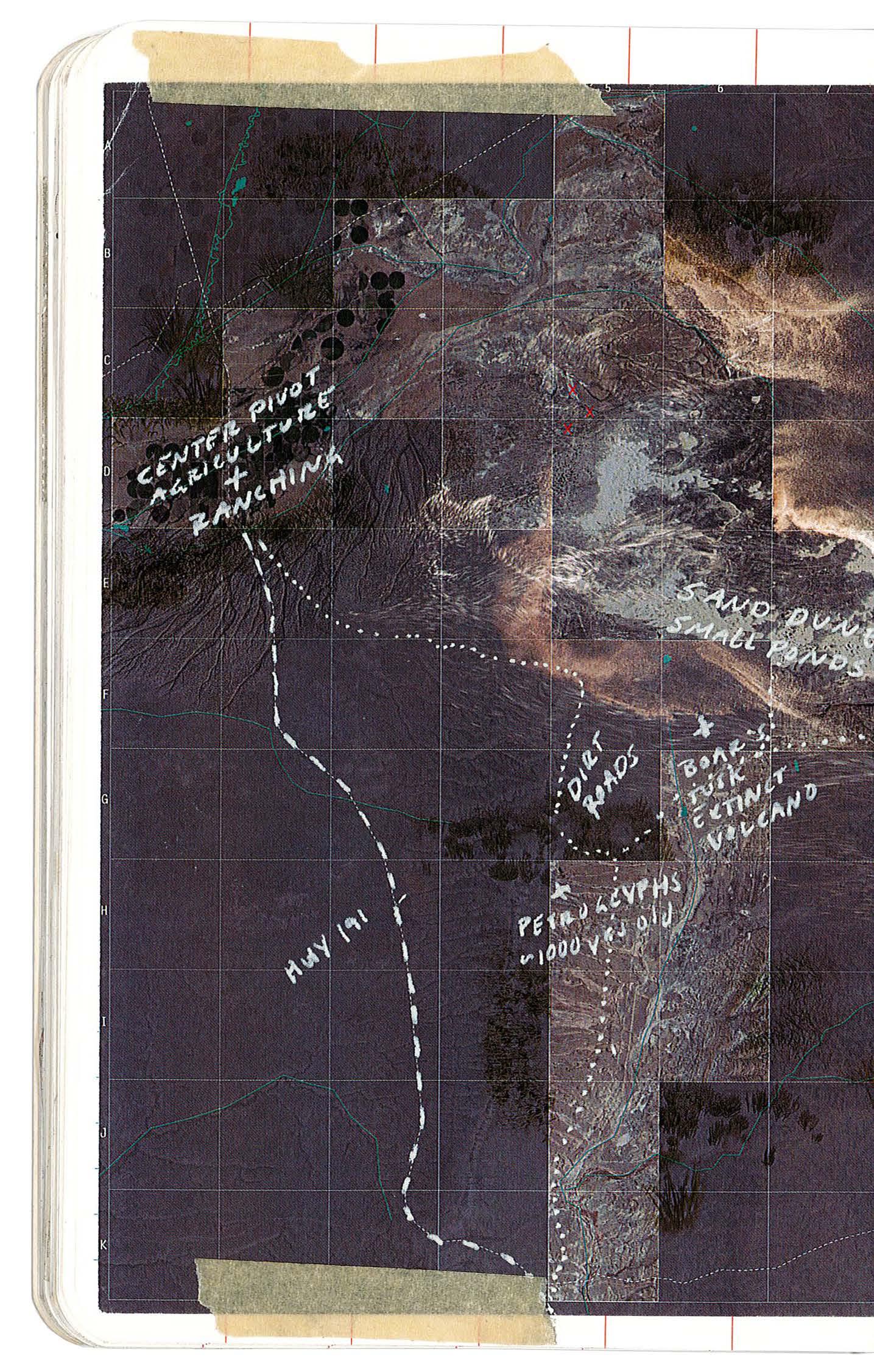

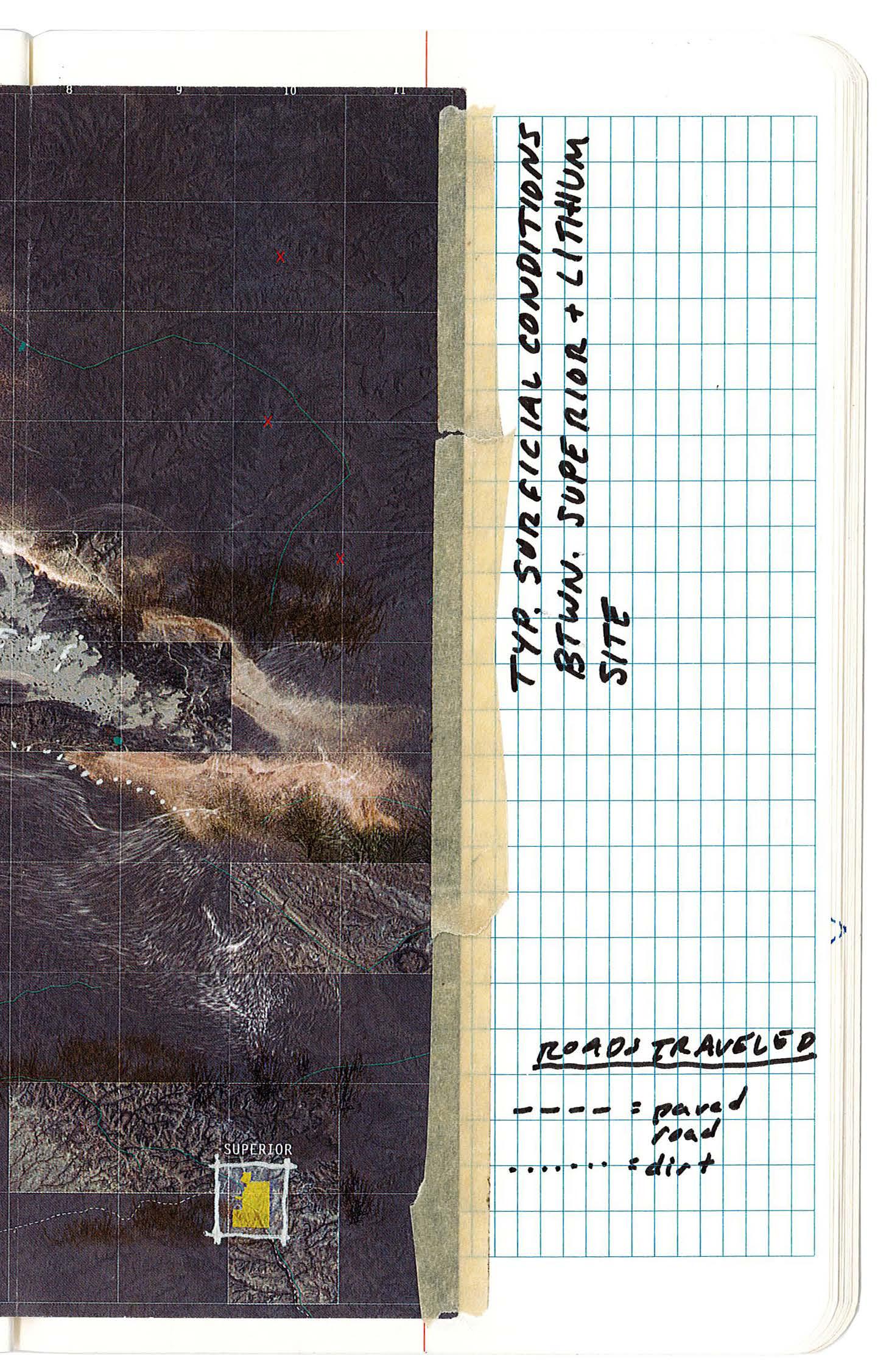

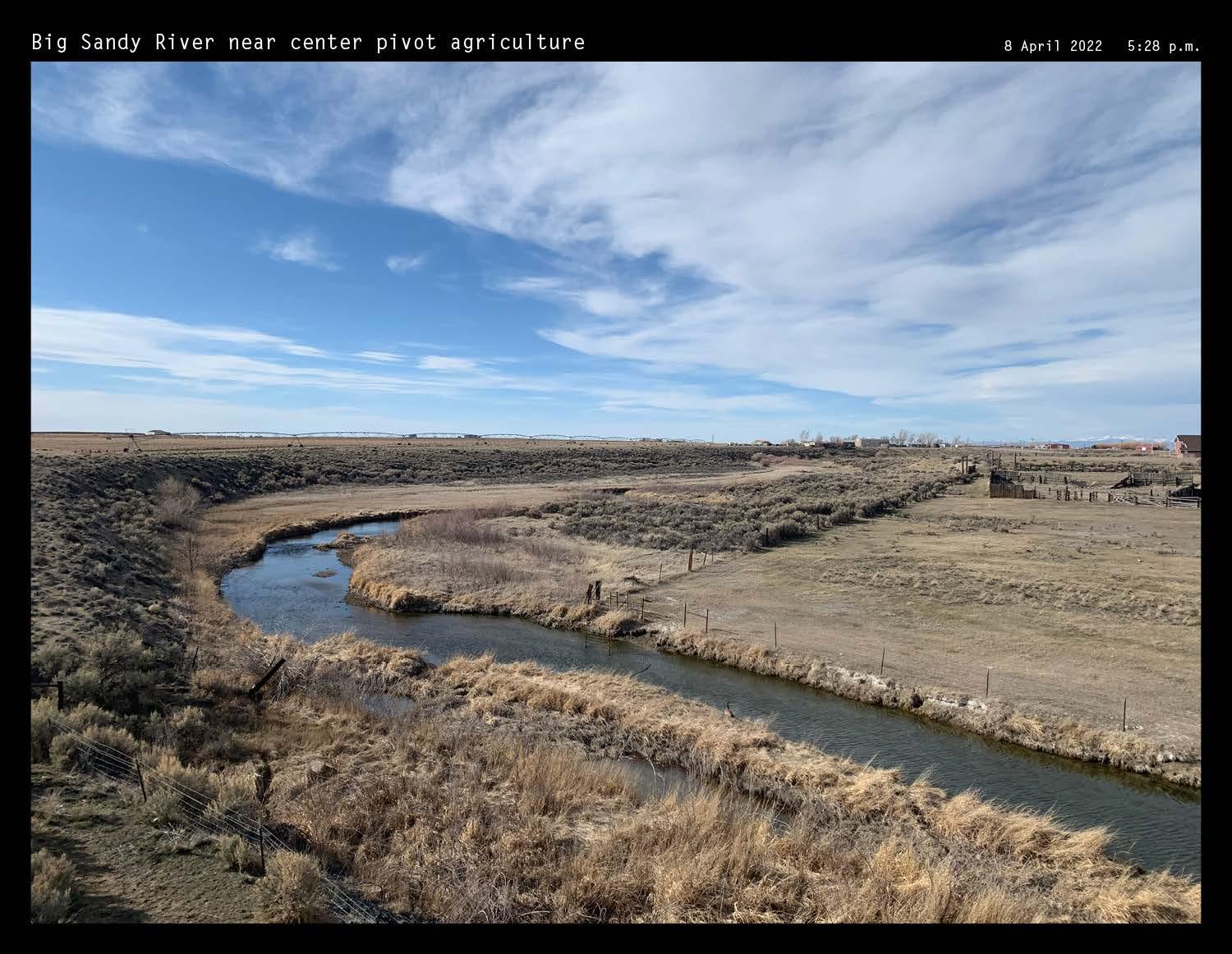

TYPICAL SURFICIAL CONDITIONS BETWEEN SUPERIOR AND LITHIUM DEPOSITS

Typical surficial conditions lying between Superior and the lithium deposit include grain farms, cattle ranching, alluvial wetlands, a vast field of sand dunes, and a sagebrush steppe ecosystem. Only the oil drilling sites stippling the surface of the arid, barren Wyoming Red Desert give hint of the geologic richness and significance under the surface.

79

VI Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes

80 +0 ft

1 mi

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

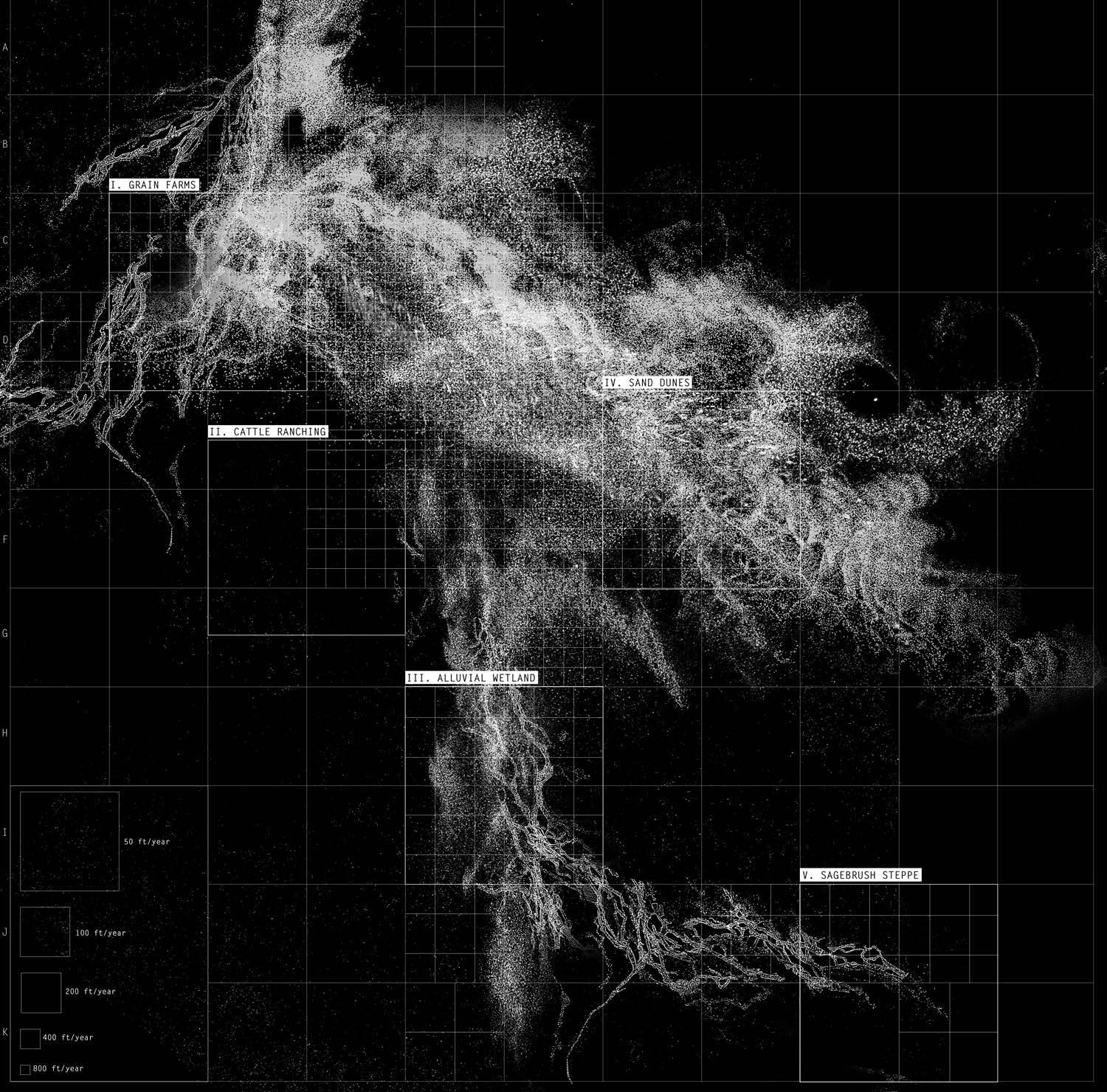

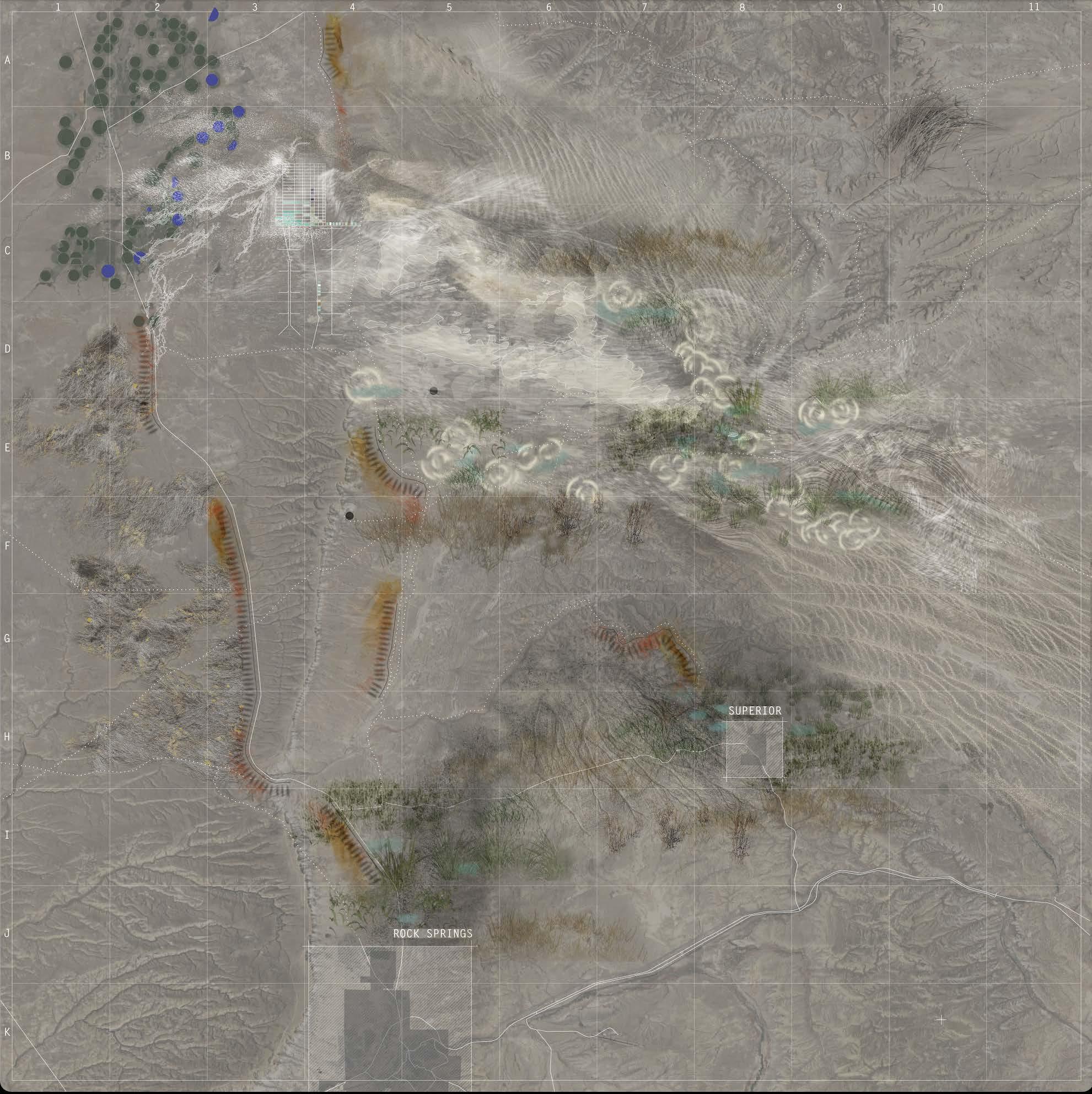

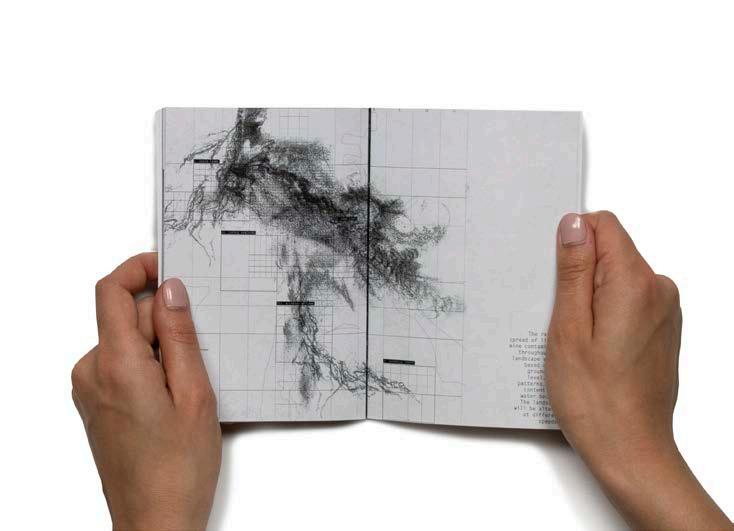

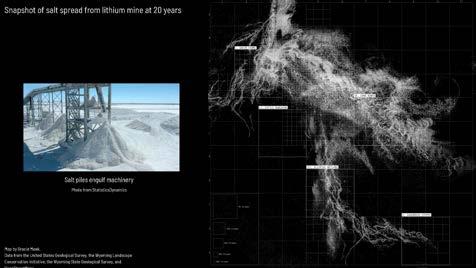

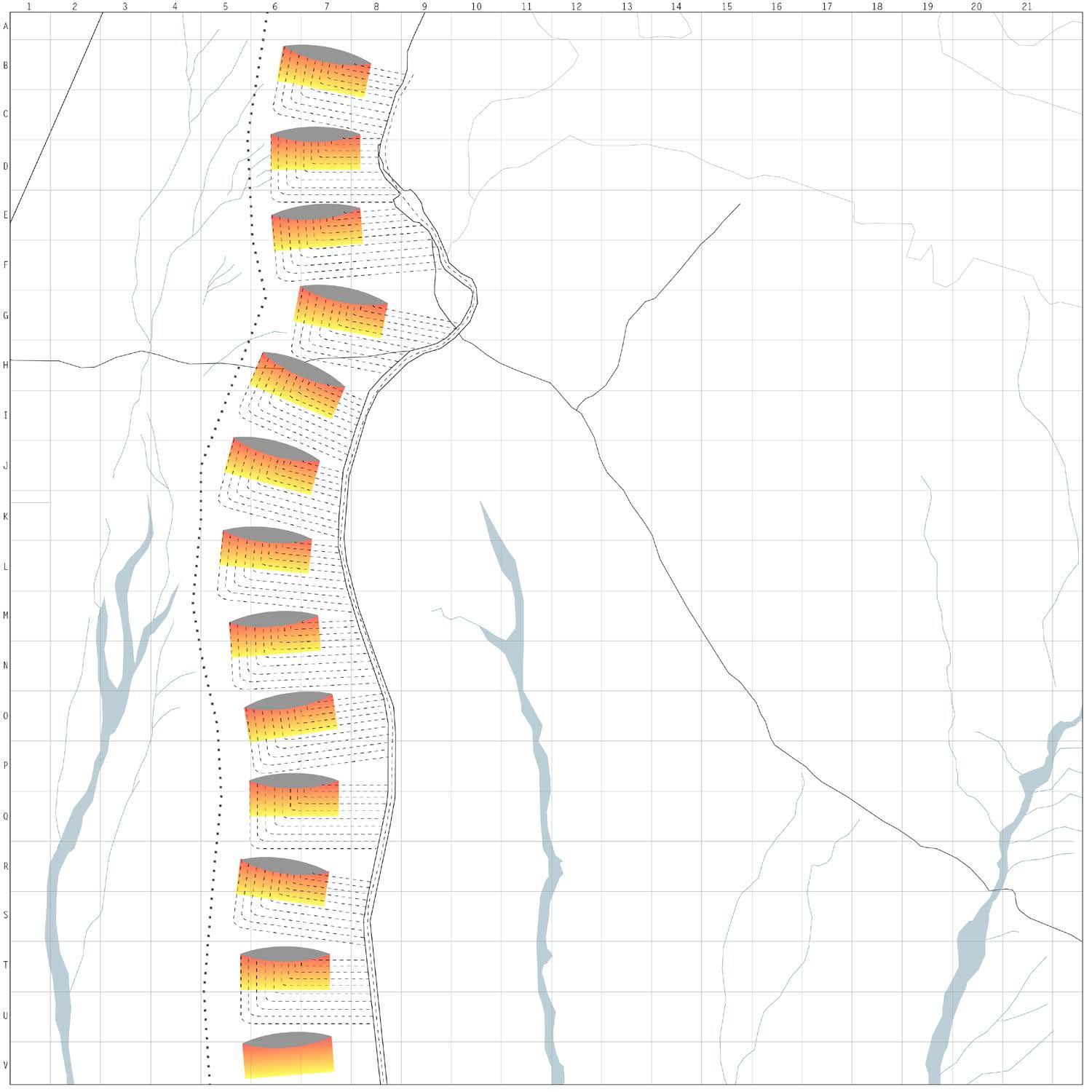

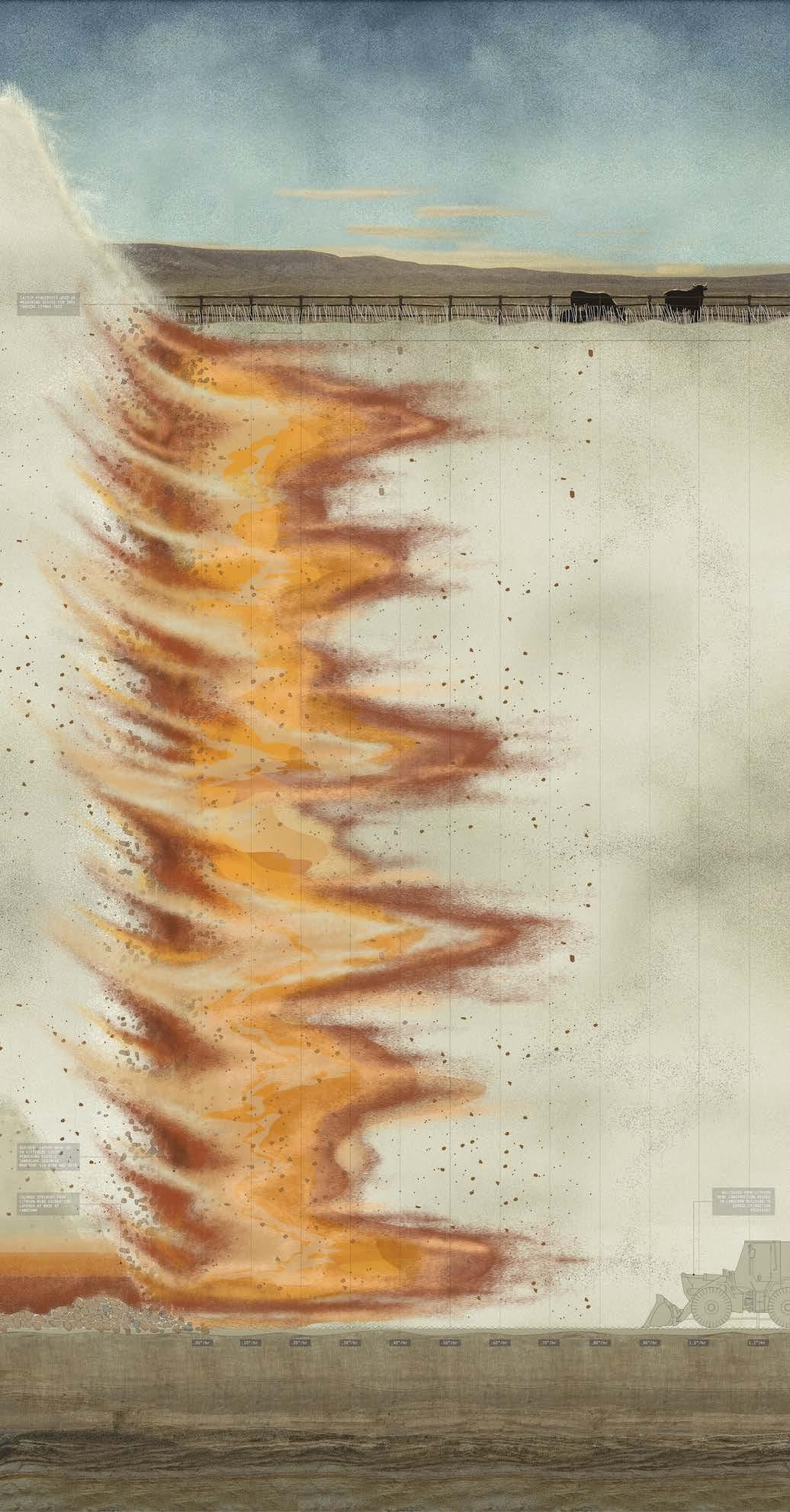

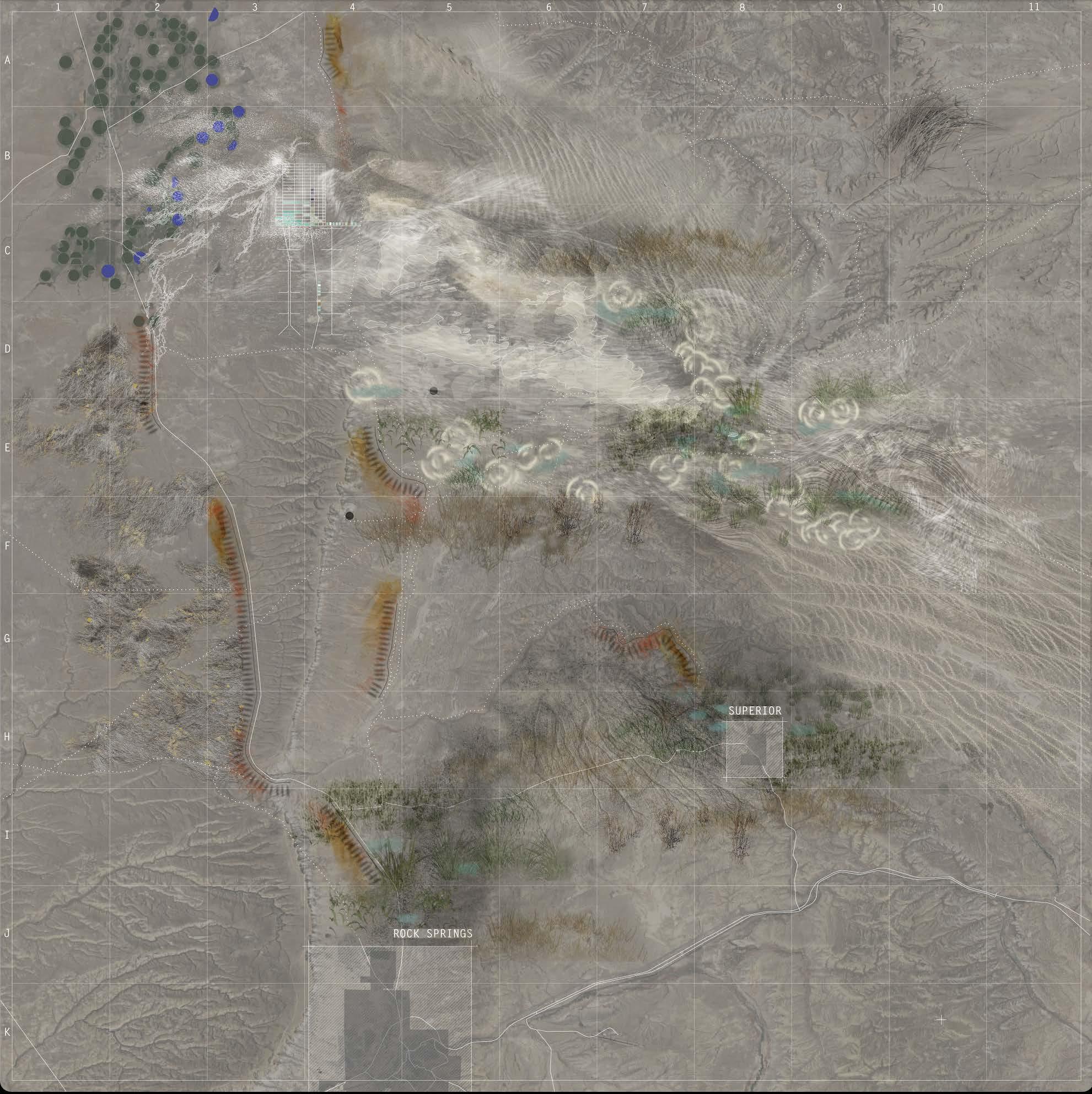

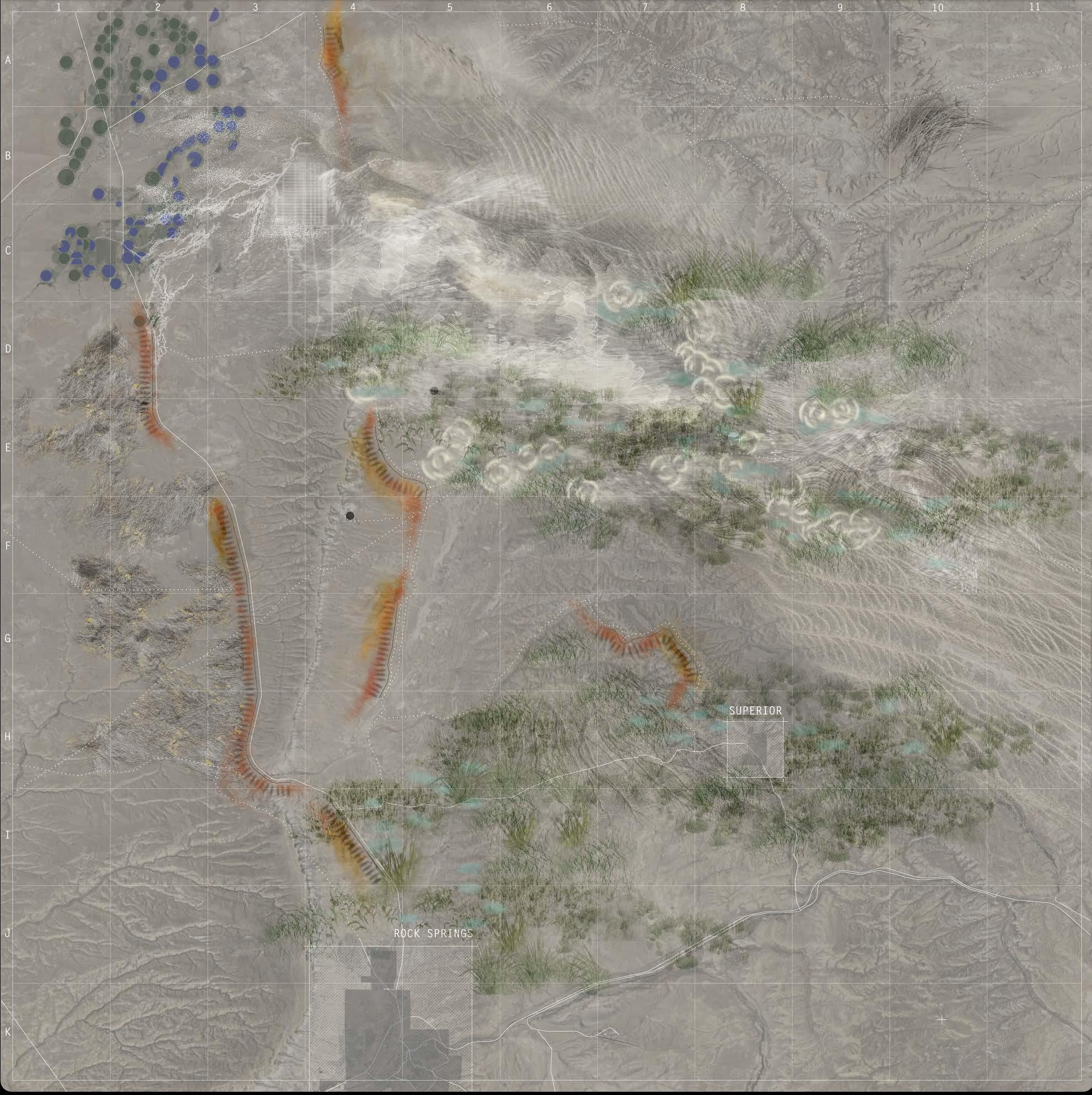

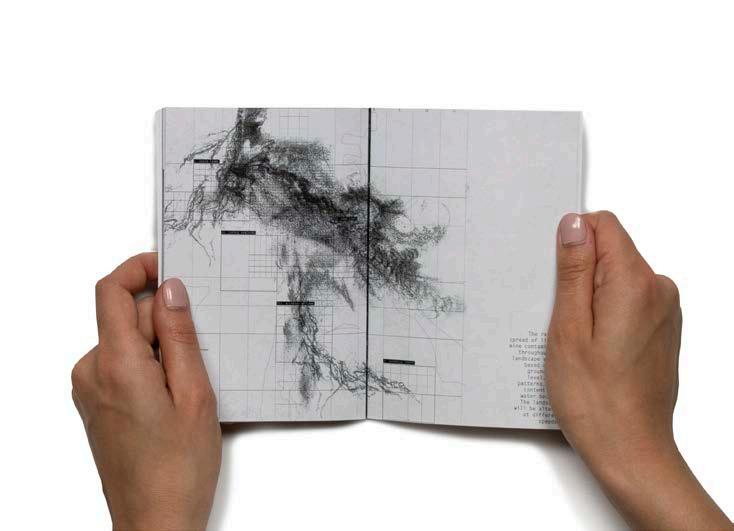

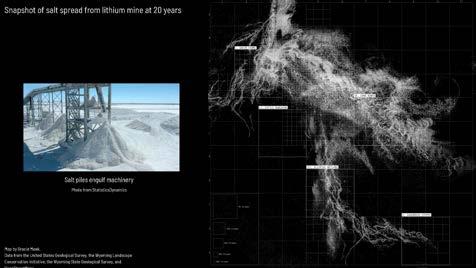

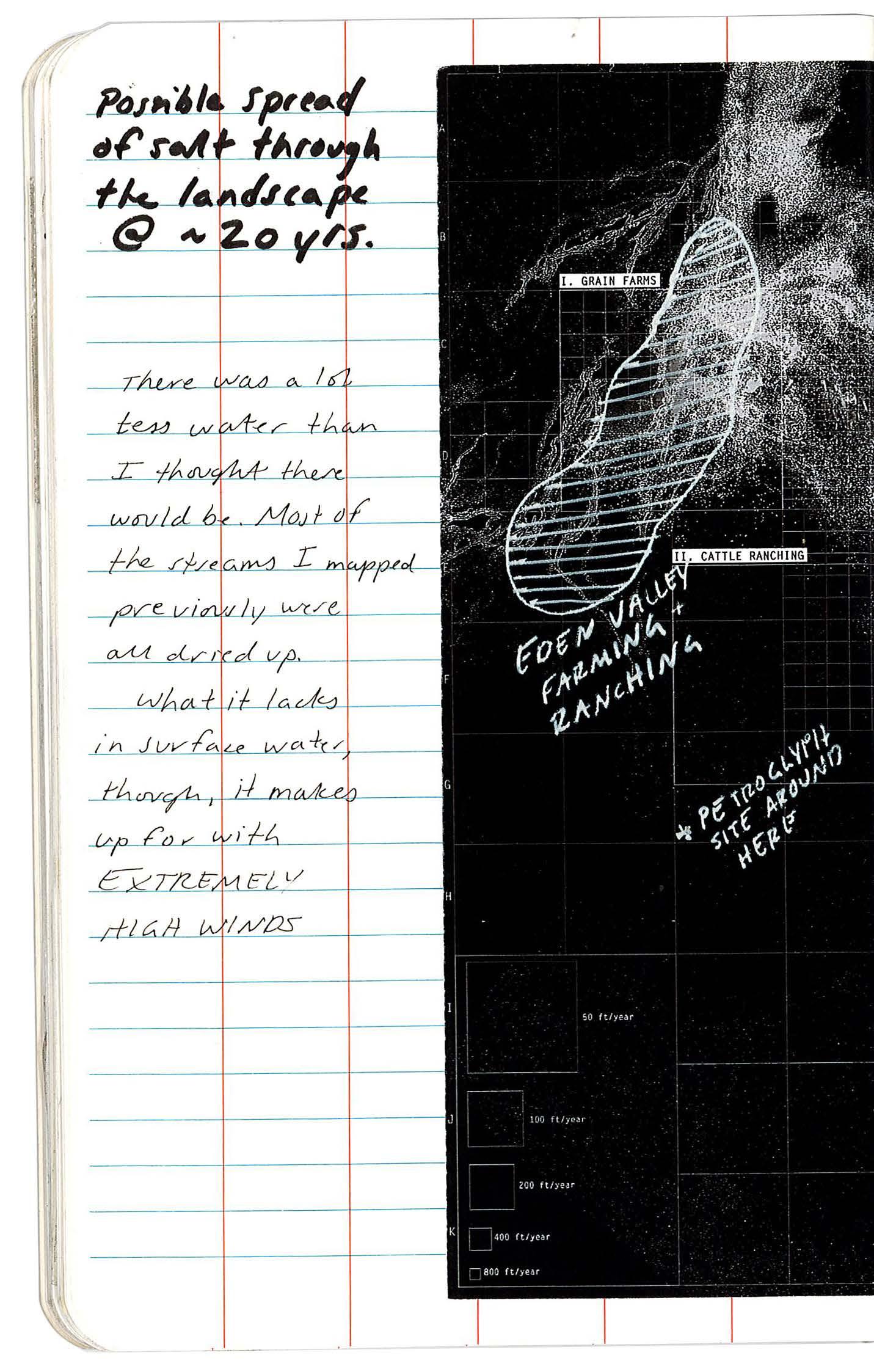

SPREAD OF SALT THROUGH THE LANDSCAPE BETWEEN SUPERIOR AND LITHIUM MINE VARIABLE DUE TO ENVIRONMENTAL AND GEOLOGIC CONDITIONS

The rate of spread of lithium mine contaminants throughout the landscape varies based on the groundwater level, wind patterns, soil content, and water bodies. The landscape will be altered at different speeds.

81

VI Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes

82 -100 ft

1 mi

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

SPREAD OF SALT THROUGH THE LANDSCAPE BETWEEN SUPERIOR AND LITHIUM MINE AFTER 20 YEARS OF OPERATION

The spread of salt byproduct over the landscape from the evaporation of lithium from briny water in pools is of large concern. People will be differently affected based on their specific practices in that region, for instance, cattle ranchers will experience the change in the landscape differently than grain farmers. An anticipation for the lithium mine’s future afterlife is critical to break the boom and bust cycle.

83

VI Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes

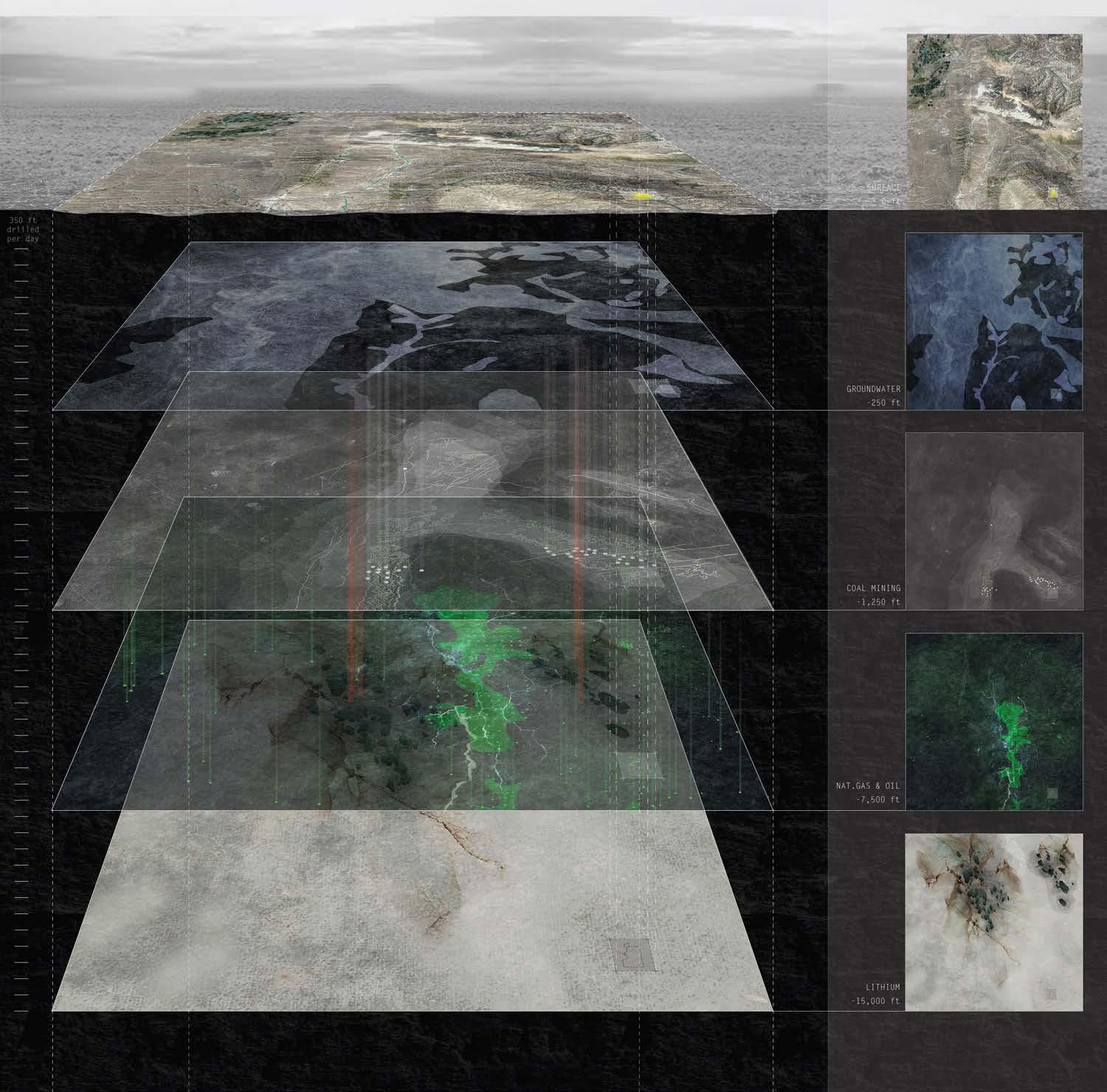

84 multiple

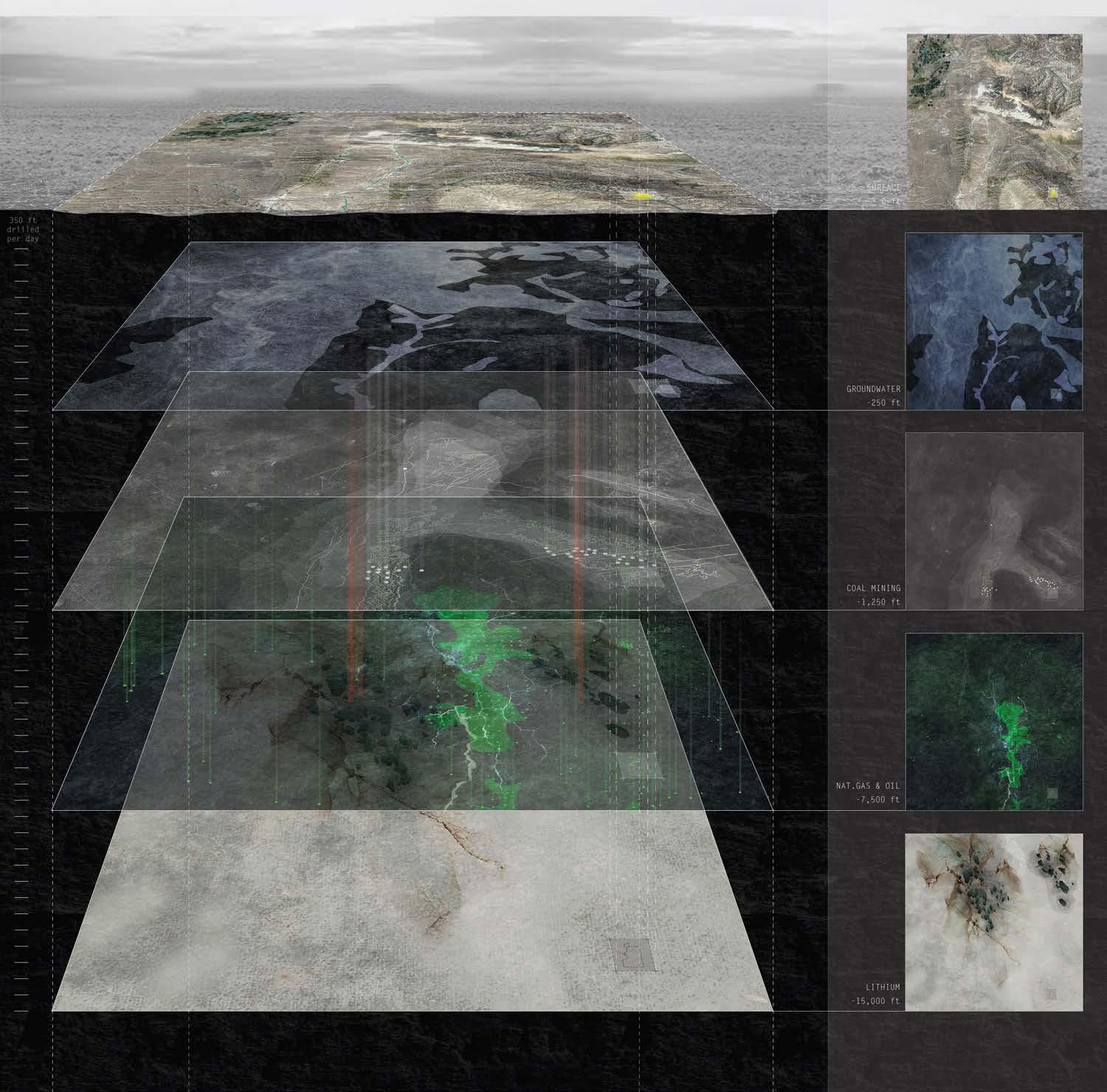

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

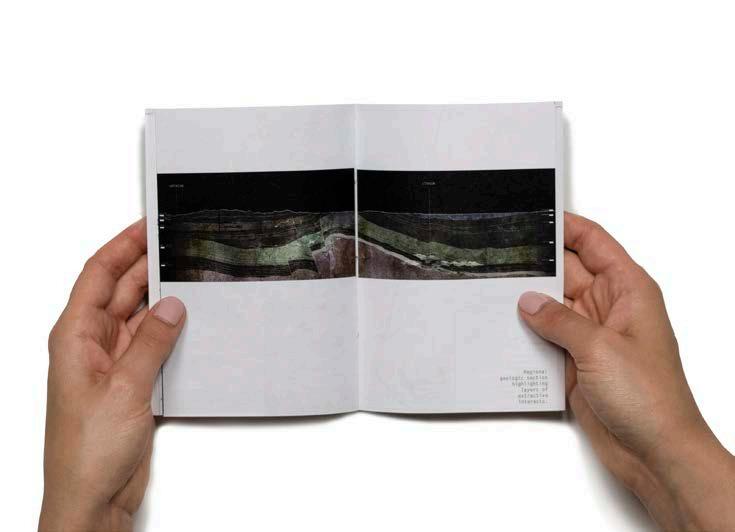

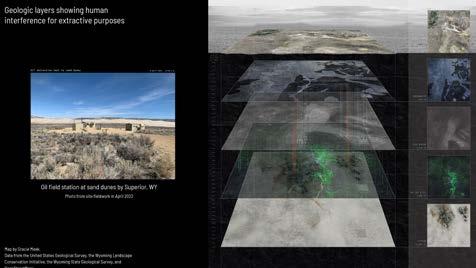

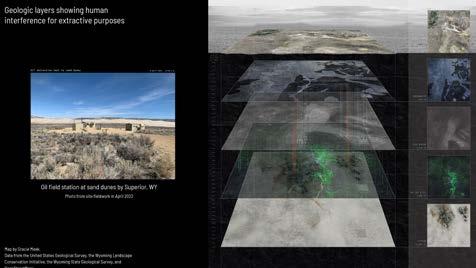

GEOLOGIC LAYERS SHOWING SUBSURFACE HUMAN INTERFERENCE THROUGH EXTRACTIVE PROCESSES

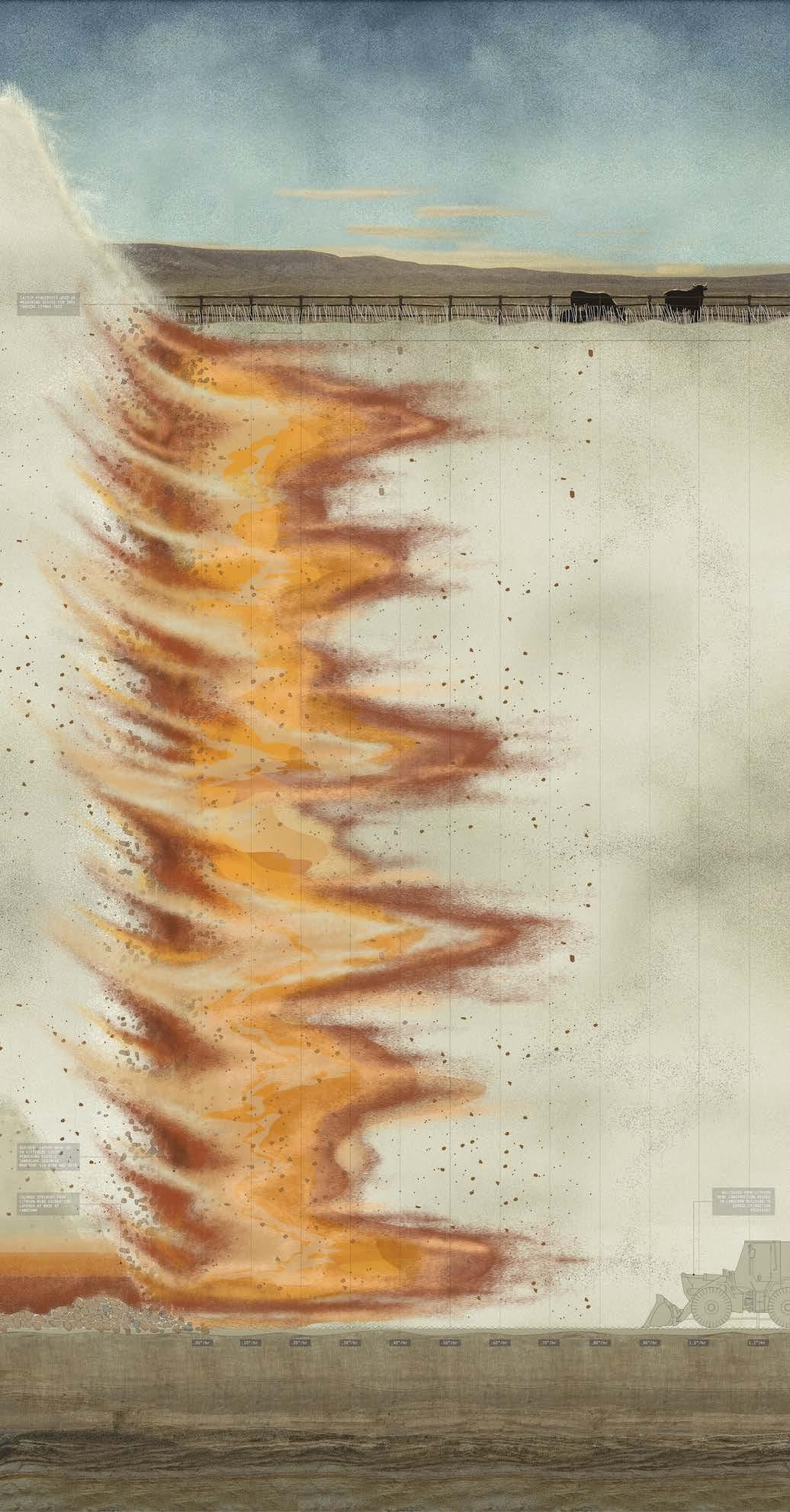

The geologic content of the land affects the spread of landscape contamination on the surface. Previous drilling operations exacerbate the spread of toxins since the groundwater layer was penetrated and exposed to leakages. Like coal, land subsidence is common with lithium mining since hollow caverns are left from the extraction of briny water pockets, leaving the ground subject to collapse.

85

VI Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes

86 +0—-15,000

ft

1 mi

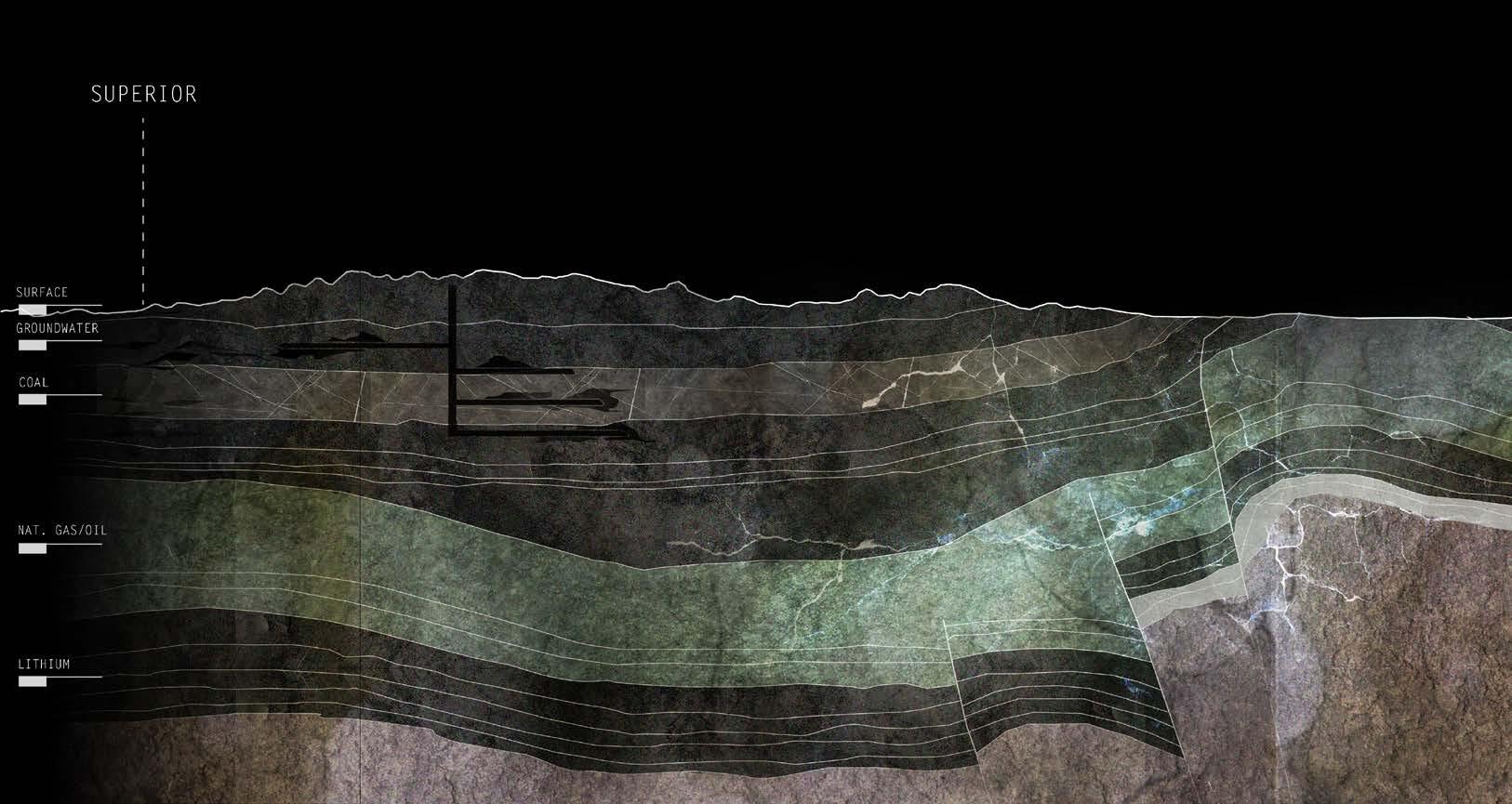

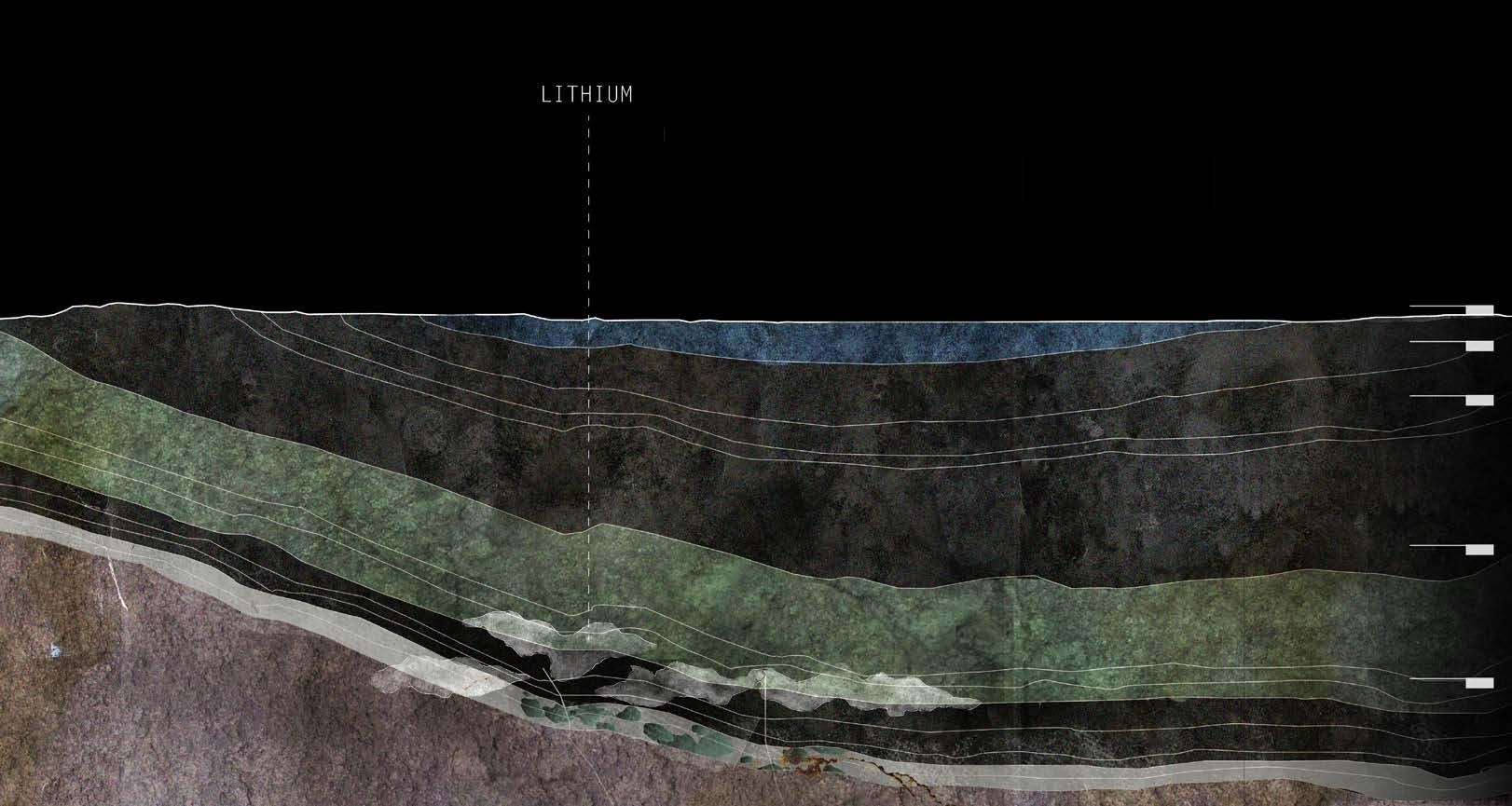

Section by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

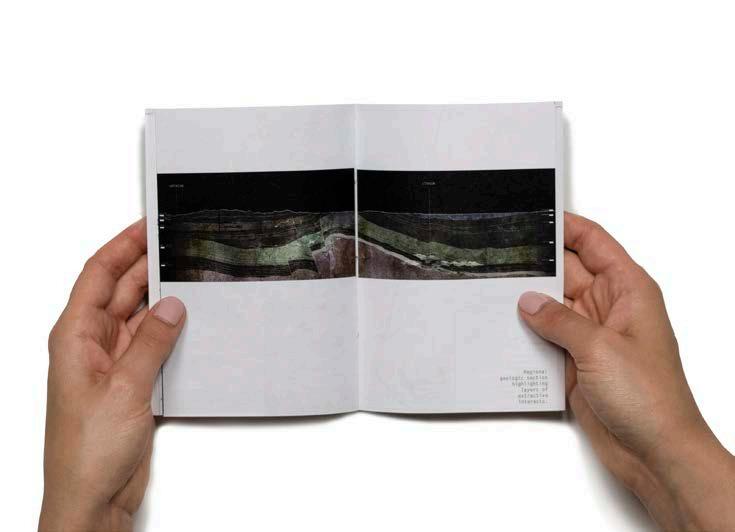

87 REGIONAL

HIGHLIGHTING

EXTRACTIVE INTERESTS VI Cartographic

of

and Future Extractive Processes

GEOLOGIC SECTION

LAYERS OF

Analysis

Past, Present,

88 +0—-15,000 ft

1 mi

Section by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

Interior conditions in D.O. Clark Mine, where my Grandfather worked, photo from Frank Prevedel and the Sweetwater County Historical Museum

89

VI Cartographic Analysis of Past, Present, and Future Extractive Processes

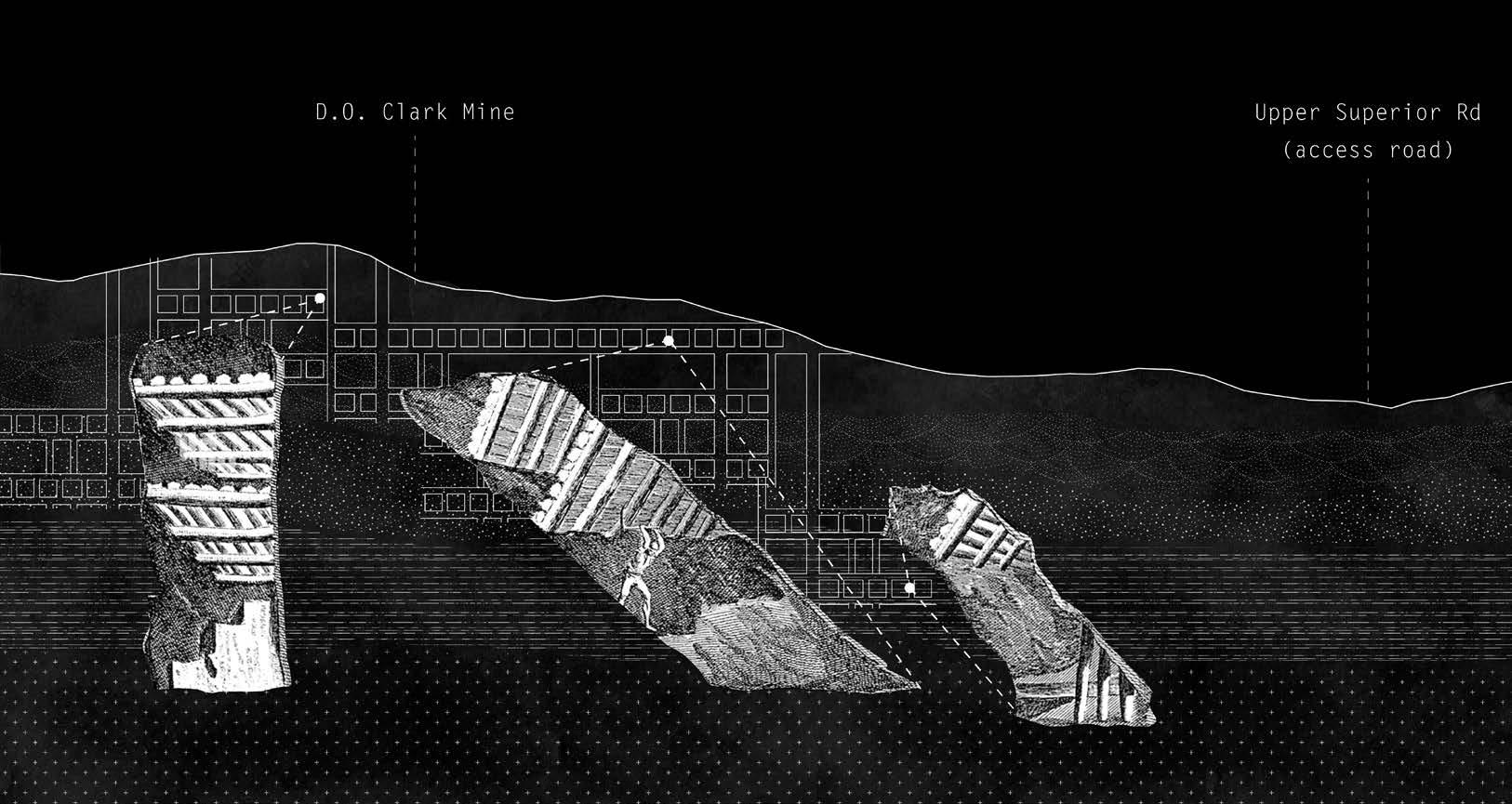

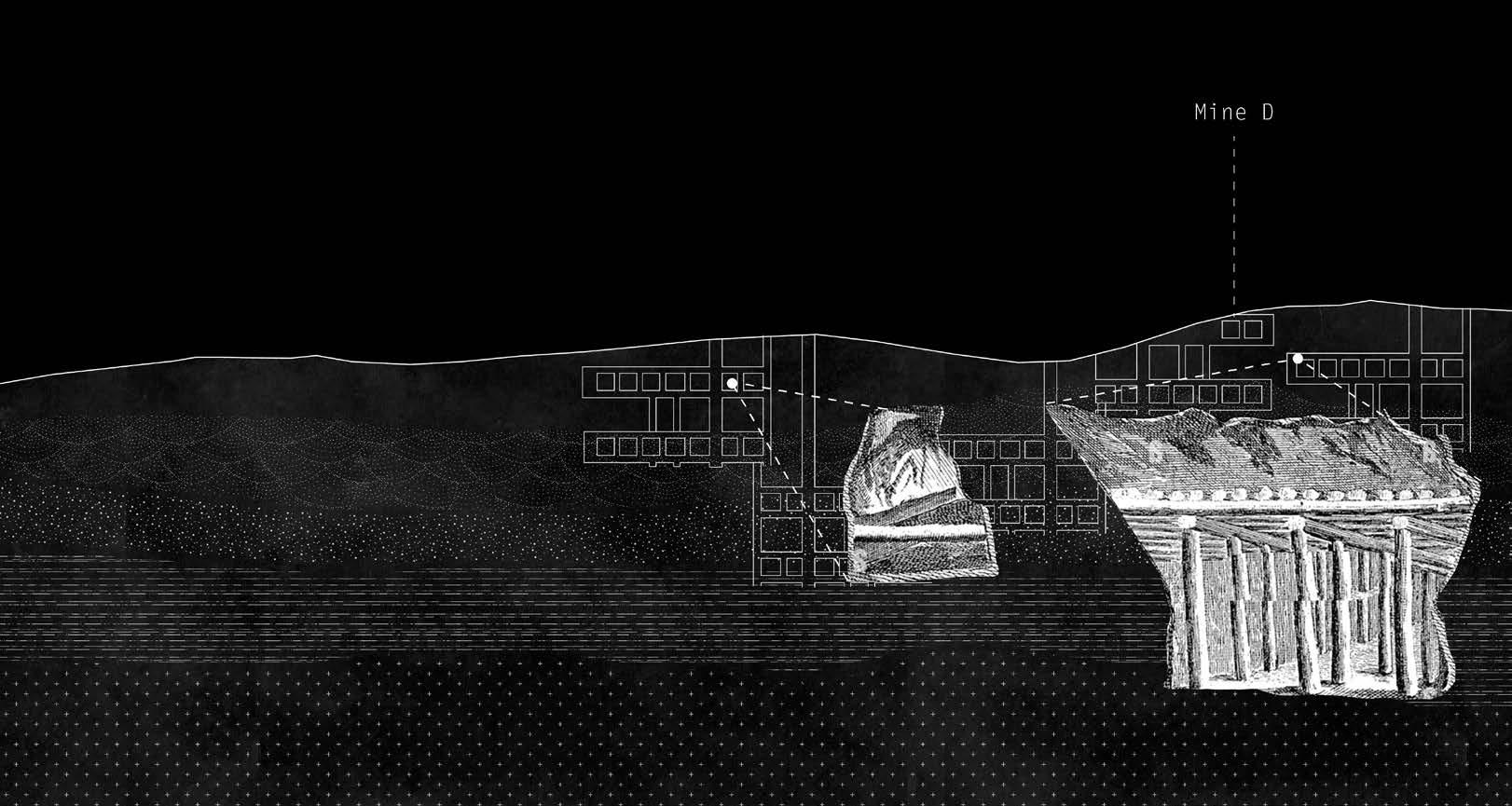

SECTIONS OF D.O. CLARK MINE AND MINE D EXPLORING INTERIOR CONDITIONS

The thesis makes circular excess materials and byproducts which are usually forgotten in the lithium extraction process.

90 VII

BYPRODUCTS AND CHOREOGRAPHY

Making Circular What is Usually Forgotten

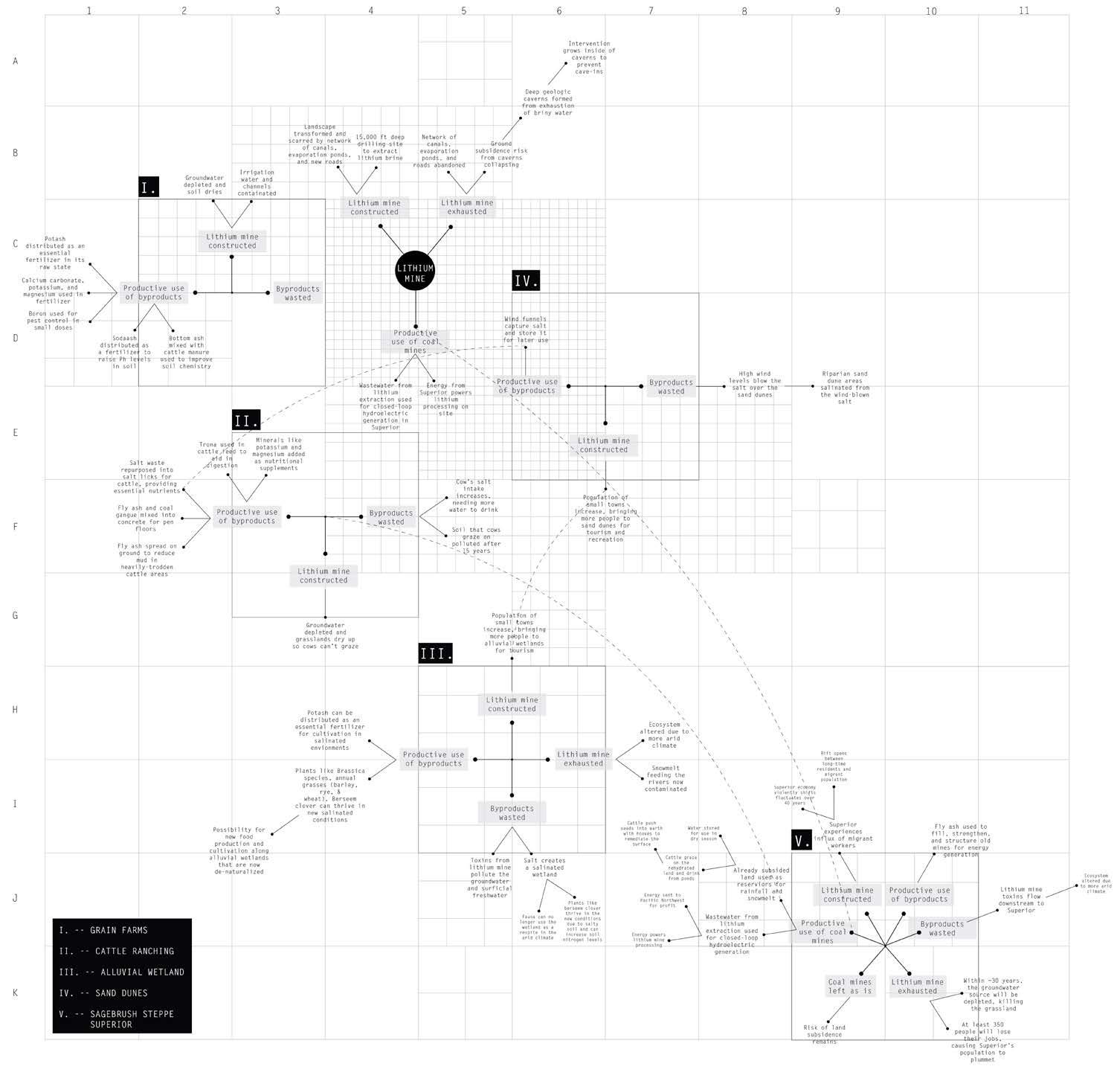

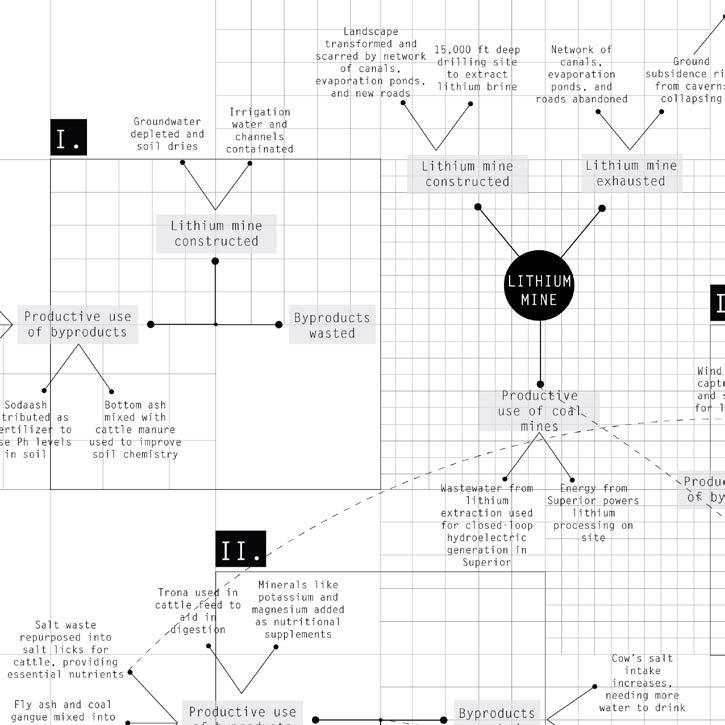

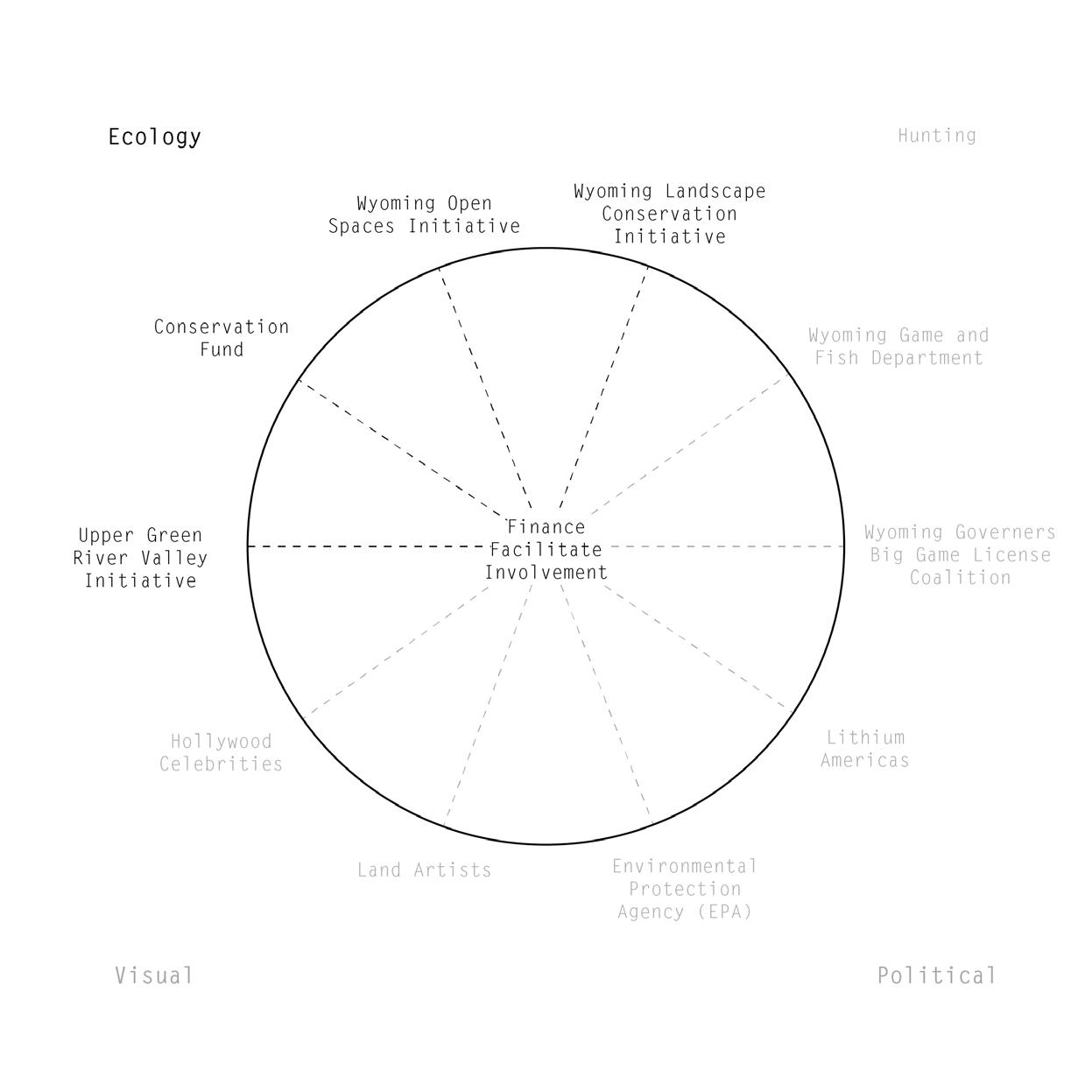

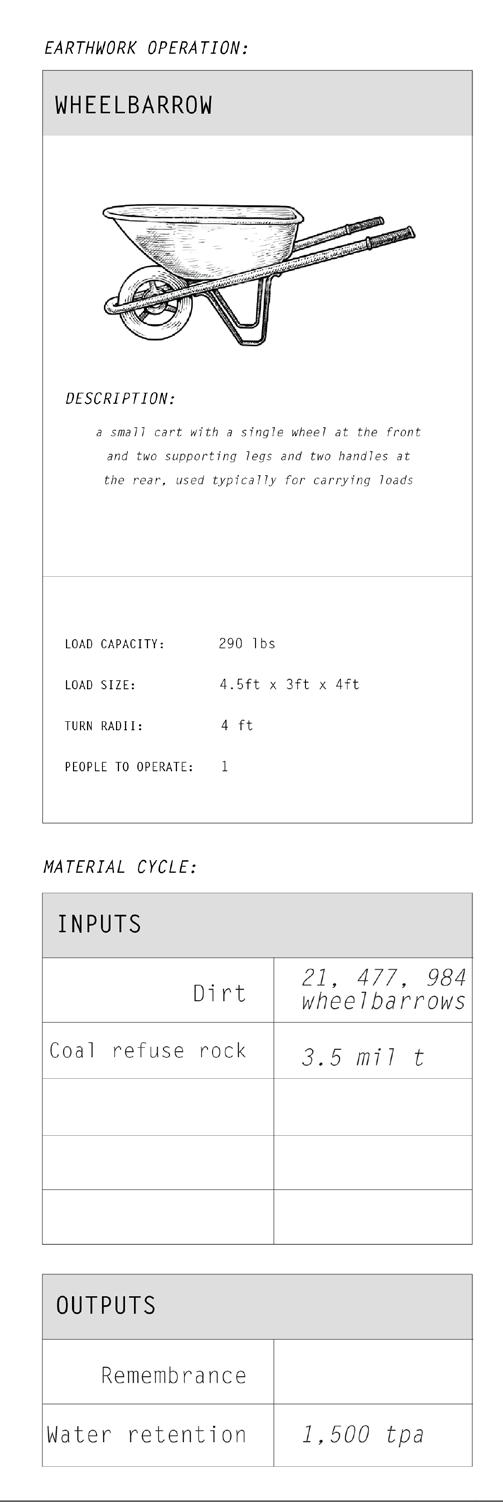

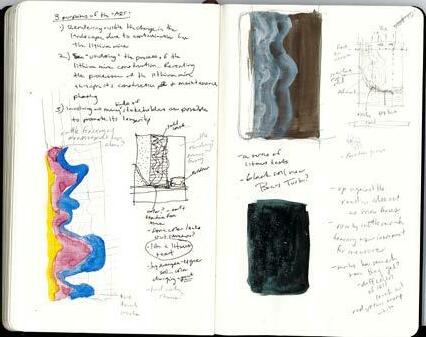

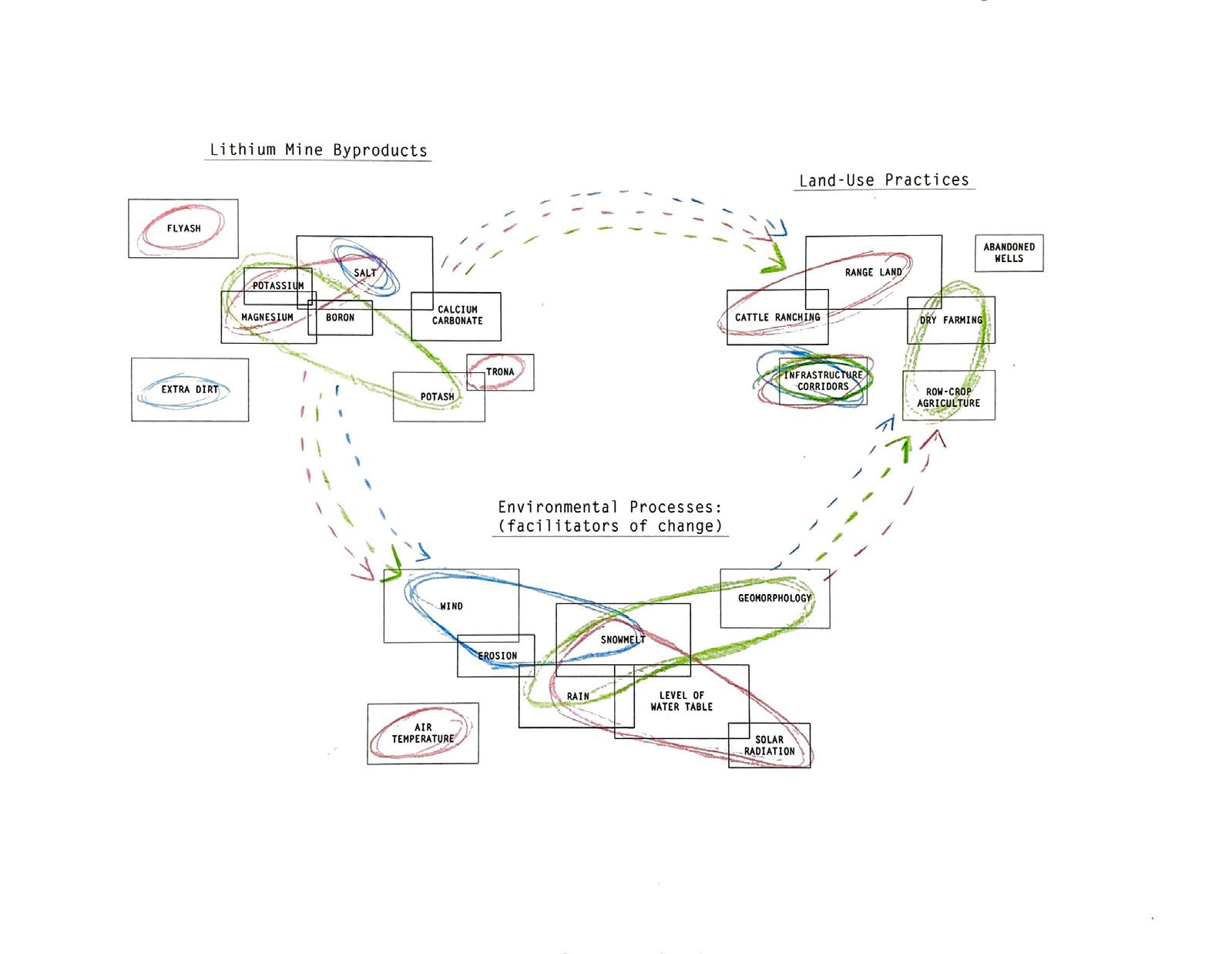

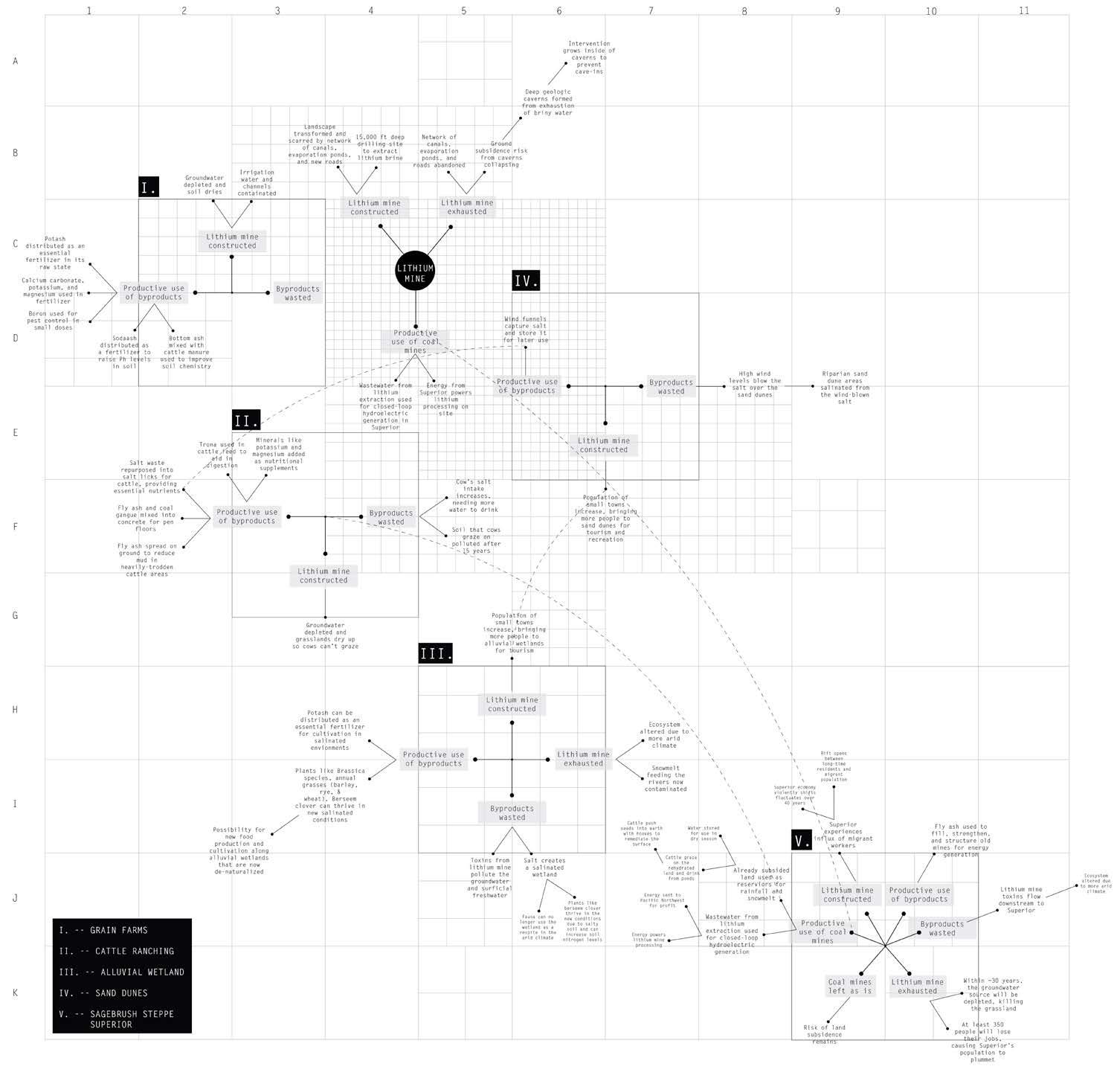

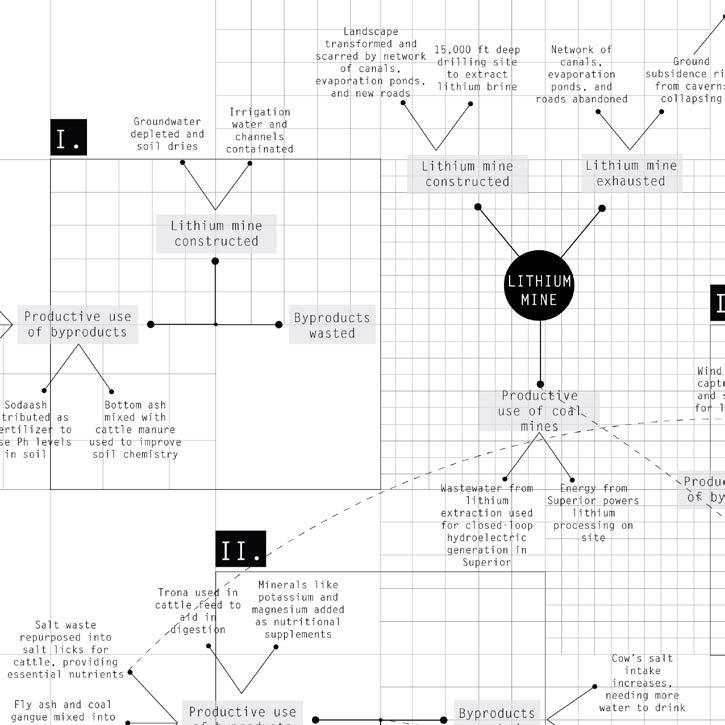

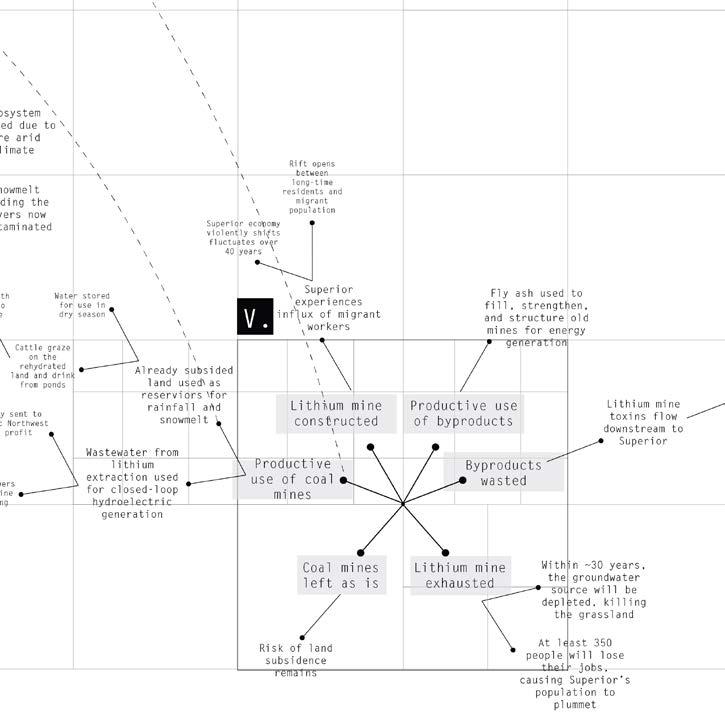

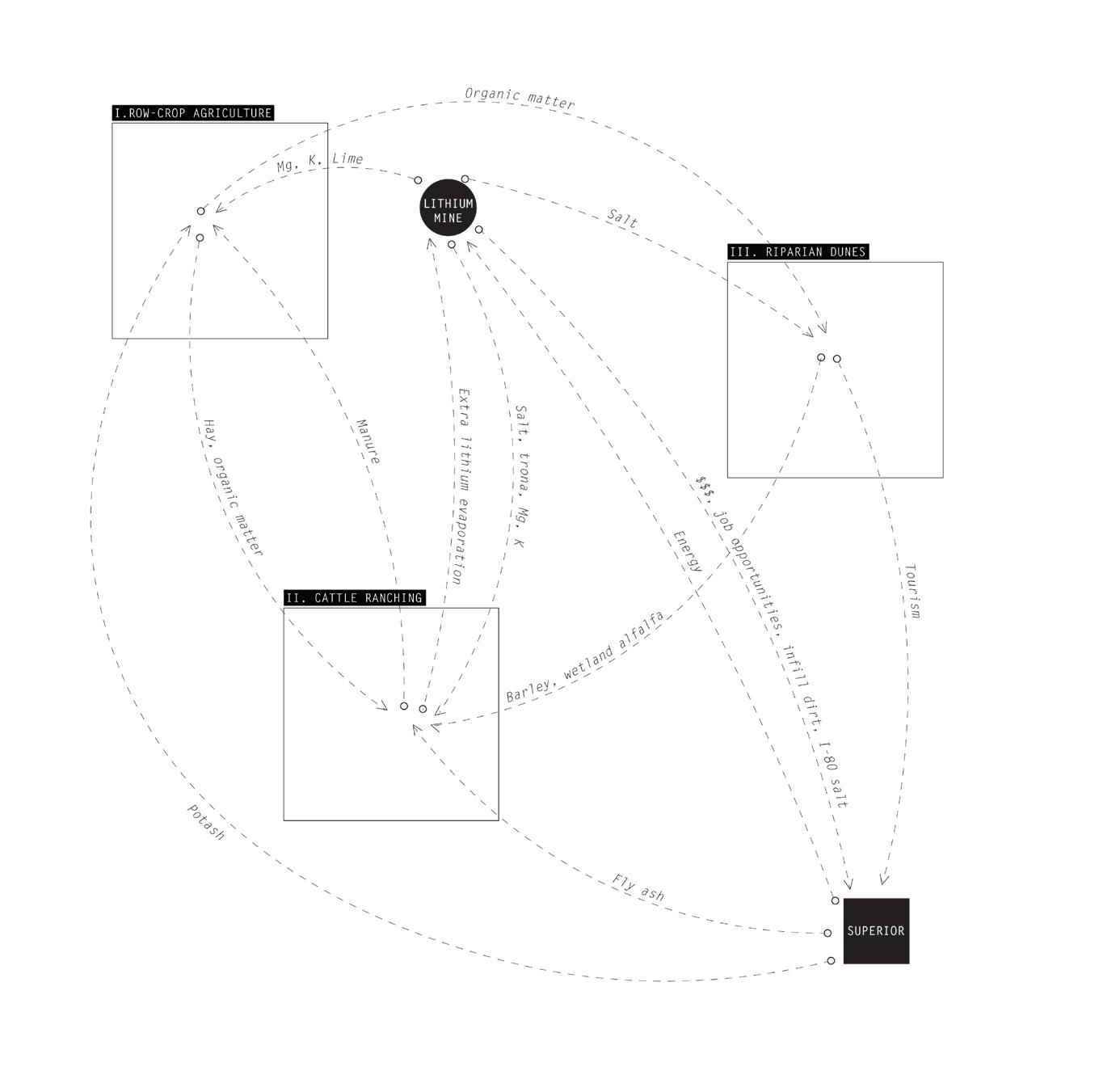

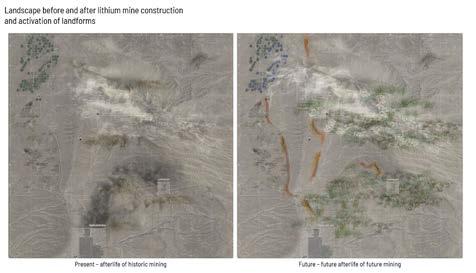

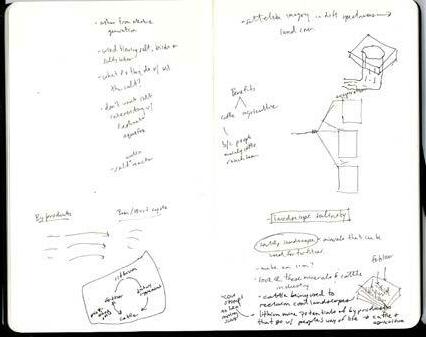

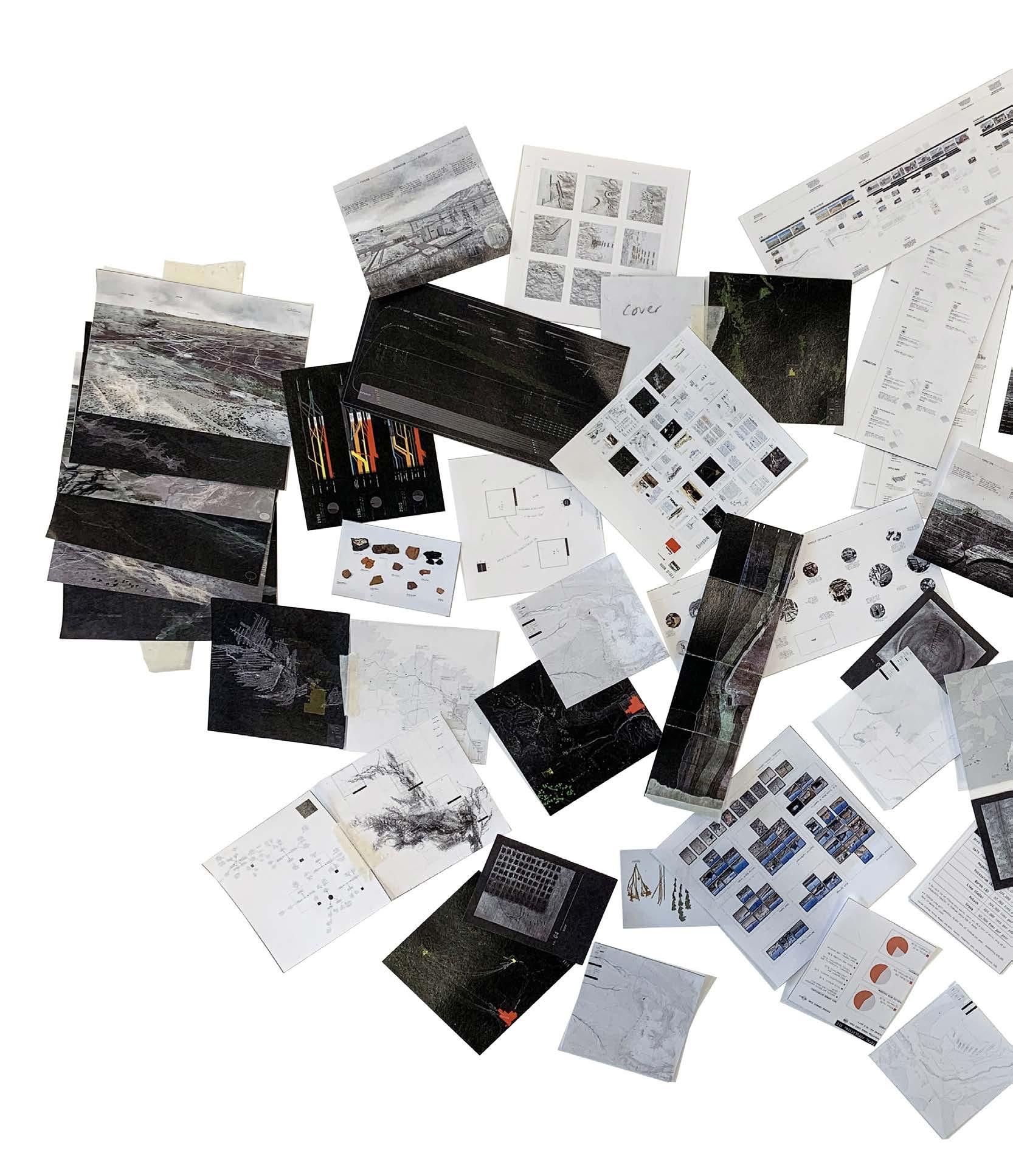

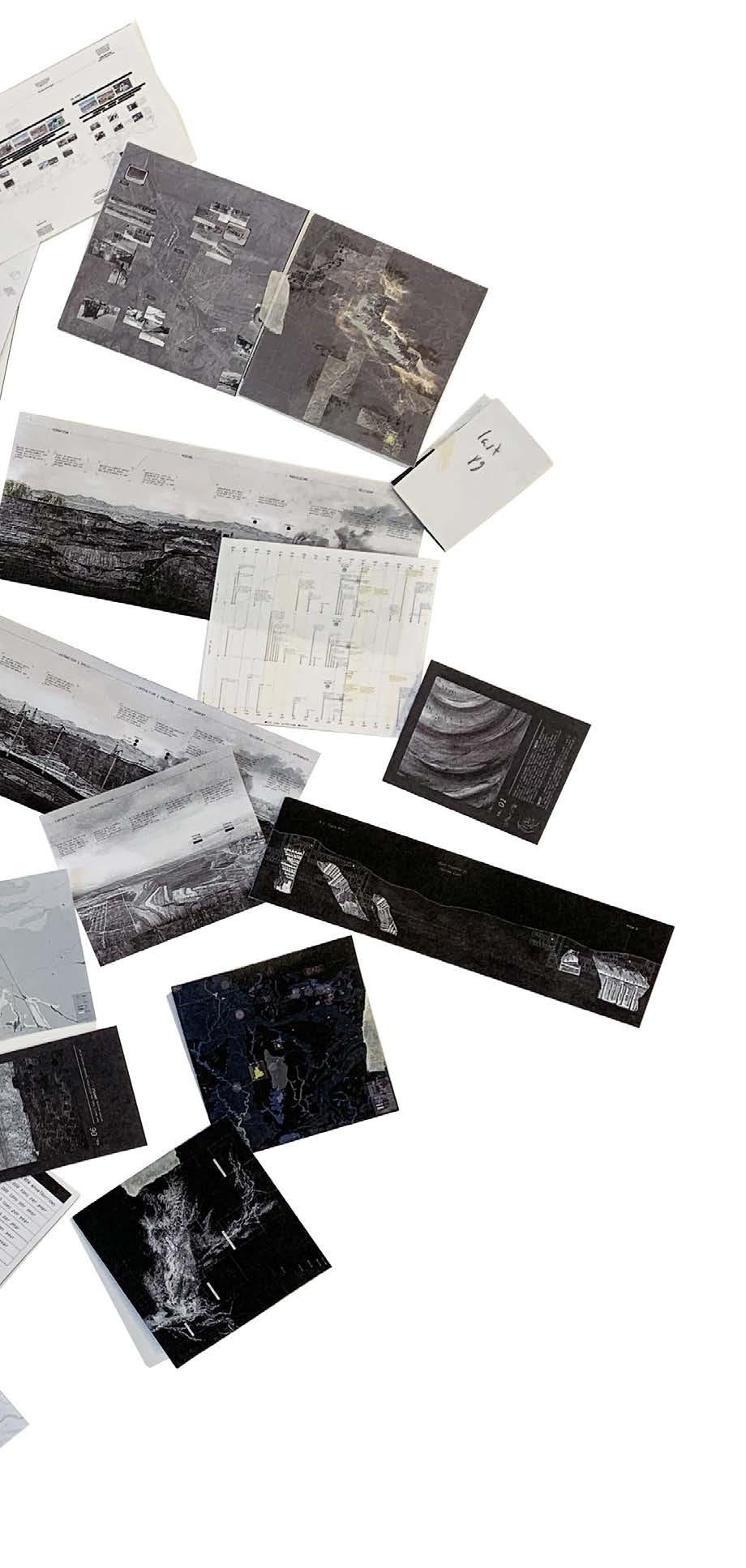

Choreographed, networked byproducts balance out excess materials from the lithium mine to make circular what is usually leftover and forgotten in extractive practices. The thesis parses byproducts, environmental processes, and land uses onto four sites where the output of one agent serves as the input for the other. Circularity is a guiding principle, but the thesis does not expect, or intend it to be, perfectly smooth.

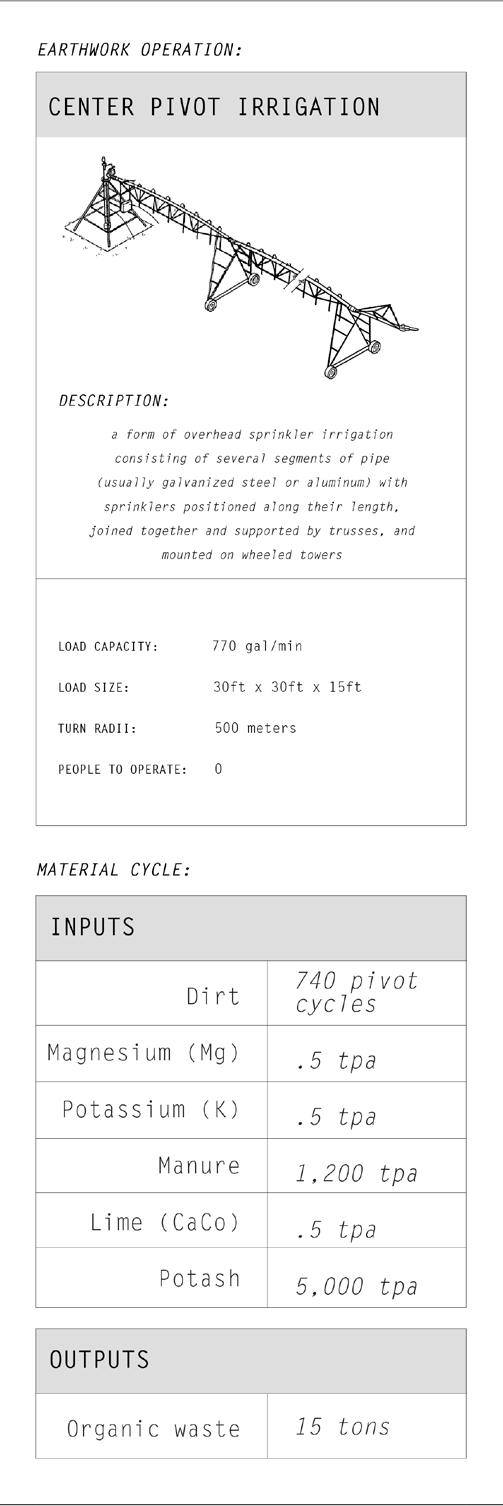

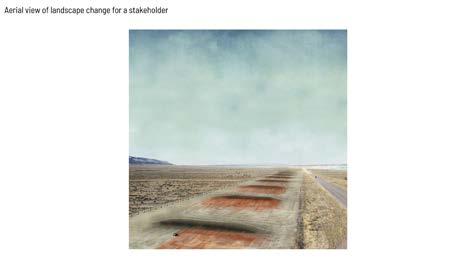

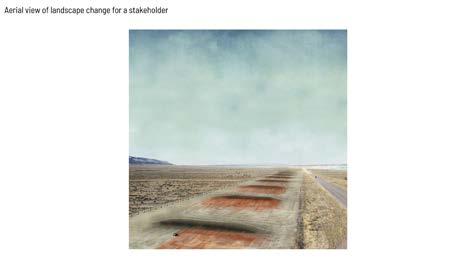

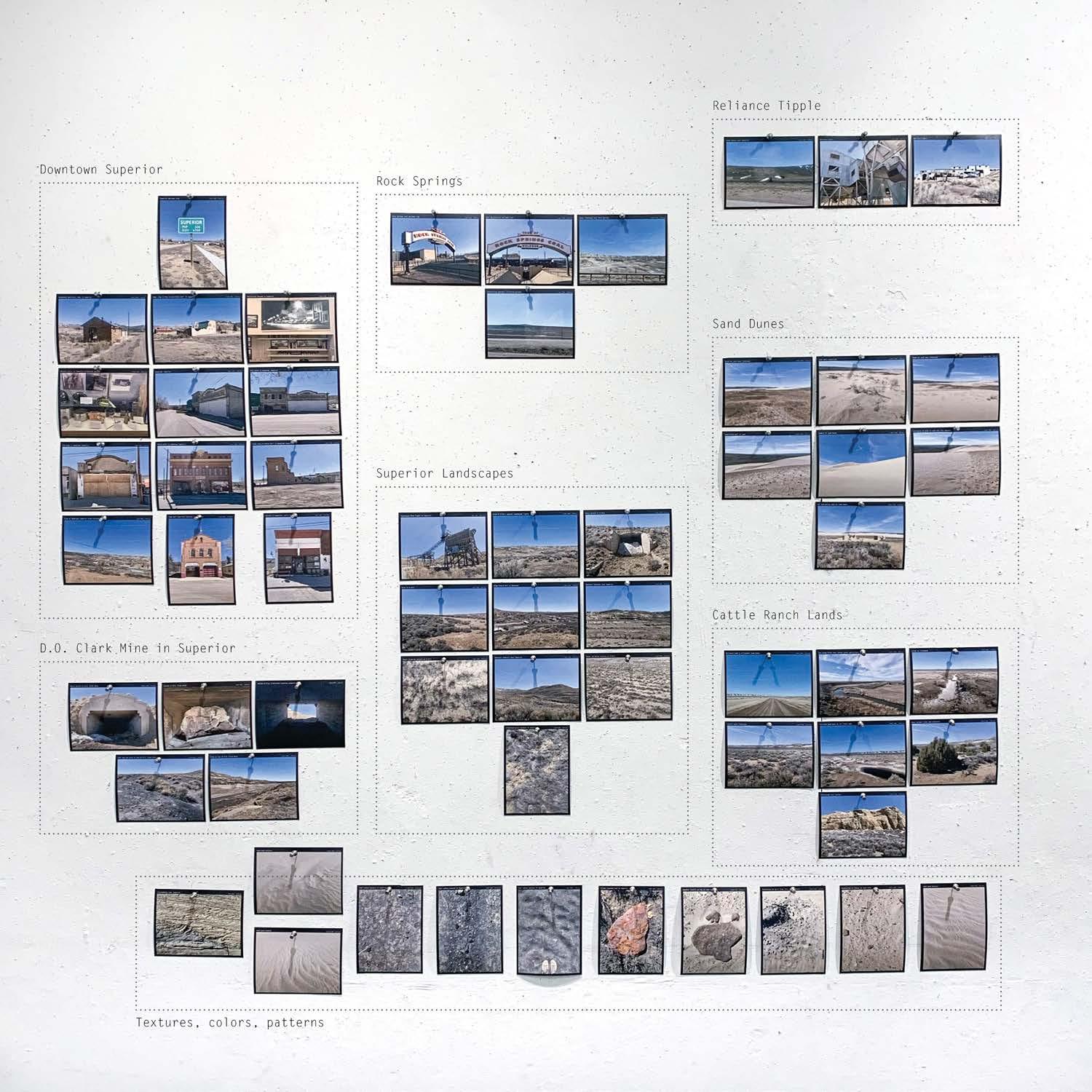

Excess materials are choreographed as a field condition onto different typical landscapes and practices. The thesis design begins with these different environments—center pivot agriculture, a vast field of sand dunes scarred by boreholes, cattle ranching, and finally, Superior. This is to anticipate future conditions when land-use practices are forced to adapt to the conditions of the pre/present/post-lithium extraction landscape.

For example, the displacement of dirt excavated for the lithium mine ponds is utilized in the construction of designed landforms. Some plants thrive in saline soil conditions and excess salt is made into salt licks for cattle. Minerals like magnesium and potassium are essential ingredients in fertilizer. Ash byproduct from coal combustion is used as a soil additive and is also spread in areas heavily trodden by cattle to prevent muddy conditions.

The initial process built and played out different scenarios to see how the landforms can anticipate and interact with different possible futures and remain productive. As a result, possible lateral activities can now develop alongside better lithium practices. It becomes like a dance, where leftover pieces of extraction move to convalesce into a circular whole.

91

VII Byproducts and Choreography

EVAPORATION

SALTS

BORON

NaCl B

WHAT: sodium chloride (table salt)

HOW GENERATED: evaporated from brine

SIDE EFFECTS: oxygen depletion in water bodies, contamination of irrigation water, freshwater reservoirs and wells, [in excess] plants cannot take water into their roots

DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: plants take up many salts in the form of nutrients; Brassica species, annual grasses (barley, rye, & wheat), Berseem clover (enriches soil with nitrigen) can thrive in these conditions when regularly irrigated; liquid salt is used in nuclear reactors; important dietary aid for cattle

MAGNESIUM

WHAT: boron (dark, brittle metalloid)

HOW GENERATED: evaporated from brine

SIDE EFFECTS: does not break down, contaminates the water table and water bodies

DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: allowed for pest control in organic food production; in low concentration it is an essential nutrient in plants and aquatic life; borax (bleach); pyrex glass

POTASSIUM

Mg K

WHAT: magnesium (shiny, gray solid)

HOW GENERATED: evaporated from brine

SIDE EFFECTS: contributes to water hardness, but not harmful to biodiversity in low levels; naturally dissolves

DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: an essential ingredient in fertilizer; in low concentration it is an essential nutrient in plants; important dietary supplement for grazing cattle; a reducing agent in the production of pure uranium

WHAT: potassium (silvery, white metal)

HOW GENERATED: evaporated from brine

SIDE EFFECTS: contributes to water softening; as a pollutant results in explosive algae growth

DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: an essential ingredient in fertilizer to resist disease; in low concentration it is an essential nutrient in plants; dietary supplement for cattle

PROCESSING

CALCIUM CARBONATE (lime)

SODIUM CARBONATE (soda ash)

WHAT: calcium carbonate (aka lime, chalk, limestone)

HOW GENERATED: removed from brine using soda ash (sodium carbonate)

SIDE EFFECTS: naturally occurring in form of sea shells etc.; produces carbon dioxide upon contact with acid

DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: pH control in soil; ingredient in fertilizers (adding calcium to the soil)

POTASSIUM CARBONATE (potash)

WHAT: sodium carbonate (a white salt)

HOW GENERATED: combination of salt and limestone to evaporate calcium carbonate (lime). Wyoming’s largest export.

SIDE EFFECTS: not harmful to environment since it is basic when it reacts with water

DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: a natural fertilizer to raise pH but makes a saltier soil; produces baking soda and powder

TRONA

WHAT: potassium containing salt in water soluble form

HOW GENERATED: removed from earth by conventional shaft mining

SIDE EFFECTS: mining creates hazardous air pollution

DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: an essential fertilizer in its raw state

WHAT: trona (a white, yellowish mineral)

HOW GENERATED: removed from earth by conventional shaft mining

SIDE EFFECTS: mining creates hazardous air pollution used to create sodium carbonate (soda ash); methane emissions

DURATION:

92

CaCO3

K2CO3 Na3H(CO3)2·2H2O Lithium byproduct information

POTENTIAL USES: used in animal feed products to aid in digestion; creates baking soda and Ayres 2013)

Na2CO3

from: (Kanji, Ong, Dahlgren, and Herbel, n.d.) and (Peiró, Méndez,

IDENTIFICATION OF LITHIUM EXTRACTION AND PROCESSING BYPRODUCTS AND THEIR POTENTIAL USES

Potential uses were narrowed down to how people living in the area might use them (i.e. agriculture, cattle ranching, and construction).

93

VII Byproducts and Choreography

COMBUSTION

REFUSE ROCK

COAL GANGUE

WHAT: refuse rock (rock leftover from mining operations)

HOW GENERATED: material left over from coal mining

SIDE EFFECTS: leaching of iron, manganese, and aluminum residues into waterways, creating both surface and groundwater contamination; vulnerable to fires

DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: very expensive to reprocess, so it is placed in a landfill

MERCURY

Hg

WHAT: mercury (shiny, silver-white metal)

HOW GENERATED: coal combustion for energy production releases mercury from the rocks

SIDE EFFECTS: burning of coal releases airborne mercury toxins

DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: in this airborne state, it is highly problemmatic and unusable

WHAT: coal gangue (solid black coal waste)

HOW GENERATED: generated during coal mining and washing

SIDE EFFECTS: disposed in landfills or discharged into nearby waterways

DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: can be used to make cement to create a structural fill to plug old coal mines

FLY ASH

BOTTOM ASH

WHAT: fly ash (a fine particulate made of cinders, ash, dust, and soot)

HOW GENERATED: composed mostly of silica made from the burning of finely ground coal in a boiler

SIDE EFFECTS: disposed in landfills or discharged into nearby waterways DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: used to make nutrientrich soil and compost; helps soil retain water; fertilizer; material to reduce mud in heavily-trodden cattle areas; make cement and grout used to create a structural fill to plug old coal mines

FLUE-GAS DESULFERIZATION SLUDGE

WHAT: flue gas desulfurization (wet sludge consisting of synthetic gypsum)

HOW GENERATED: a material leftover from the process of reducing sulfur dioxide emissions in coal burning

SIDE EFFECTS: disposed of in holding pond

DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: synthetic gypsum can be used as fertilizer to improve soil chemistry; used to make synthetic gypsum for wallboards; also used in concrete and mine fills

WHAT: bottom ash (coarse, angular ash particle)

HOW GENERATED: when burned is too large to be carried up into the smoke stacks so it forms in the bottom of the coal furnace

SIDE EFFECTS: disposed in landfills or discharged into nearby waterways DURATION:

POTENTIAL USES: when mixed with cow manure can be used as fertilizer to improve soil chemistry; used in road construction, snow/ice control on roads, and cement

94

MINING

Coal byproduct information from: (Song, Gang, Ma, Yang, and Mu 2017)

IDENTIFICATION OF COAL EXTRACTION AND PROCESSING BYPRODUCTS AND THEIR POTENTIAL USES

Potential uses were narrowed down to how people living in the area might use them (i.e. agriculture, cattle ranching, and construction).

95

VII Byproducts and Choreography

96

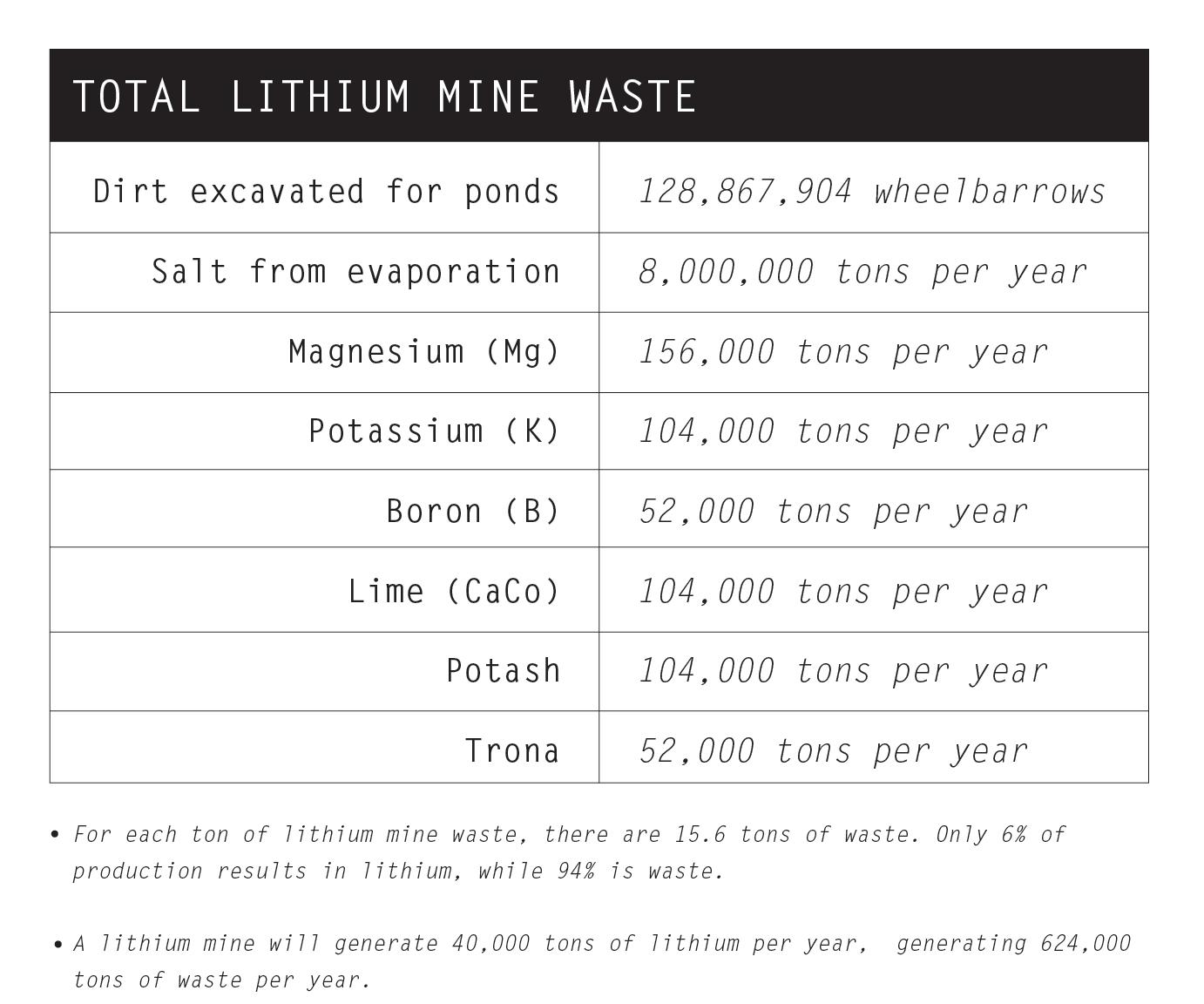

Lithium mine waste data from: (Peiró, Méndez, and Ayres 2013)

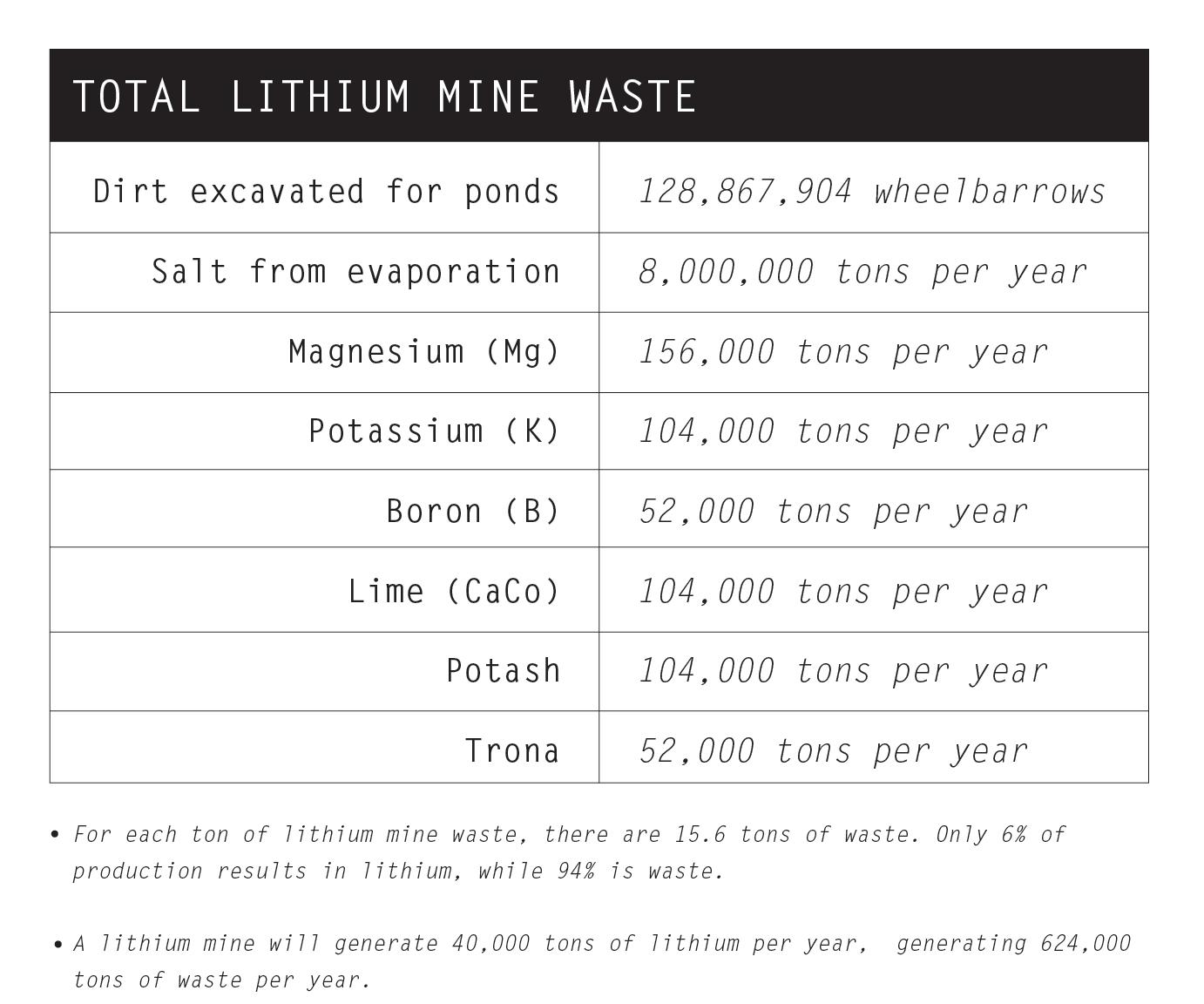

TOTAL LITHIUM MINE MATERIAL WASTE

Astonishingly, only 6% of total production results in usable lithium, while 94% is waste.

97

VII Byproducts and Choreography

98

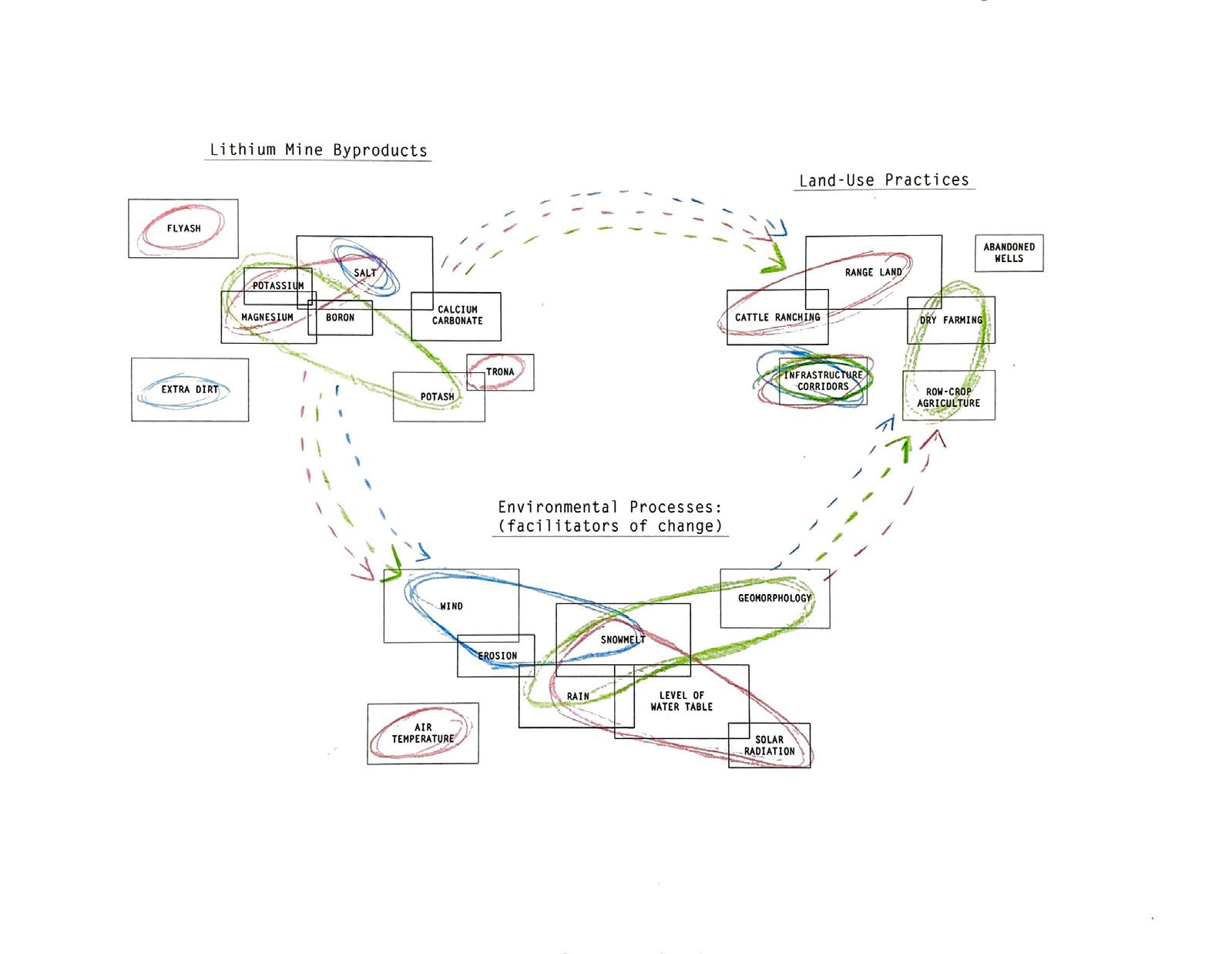

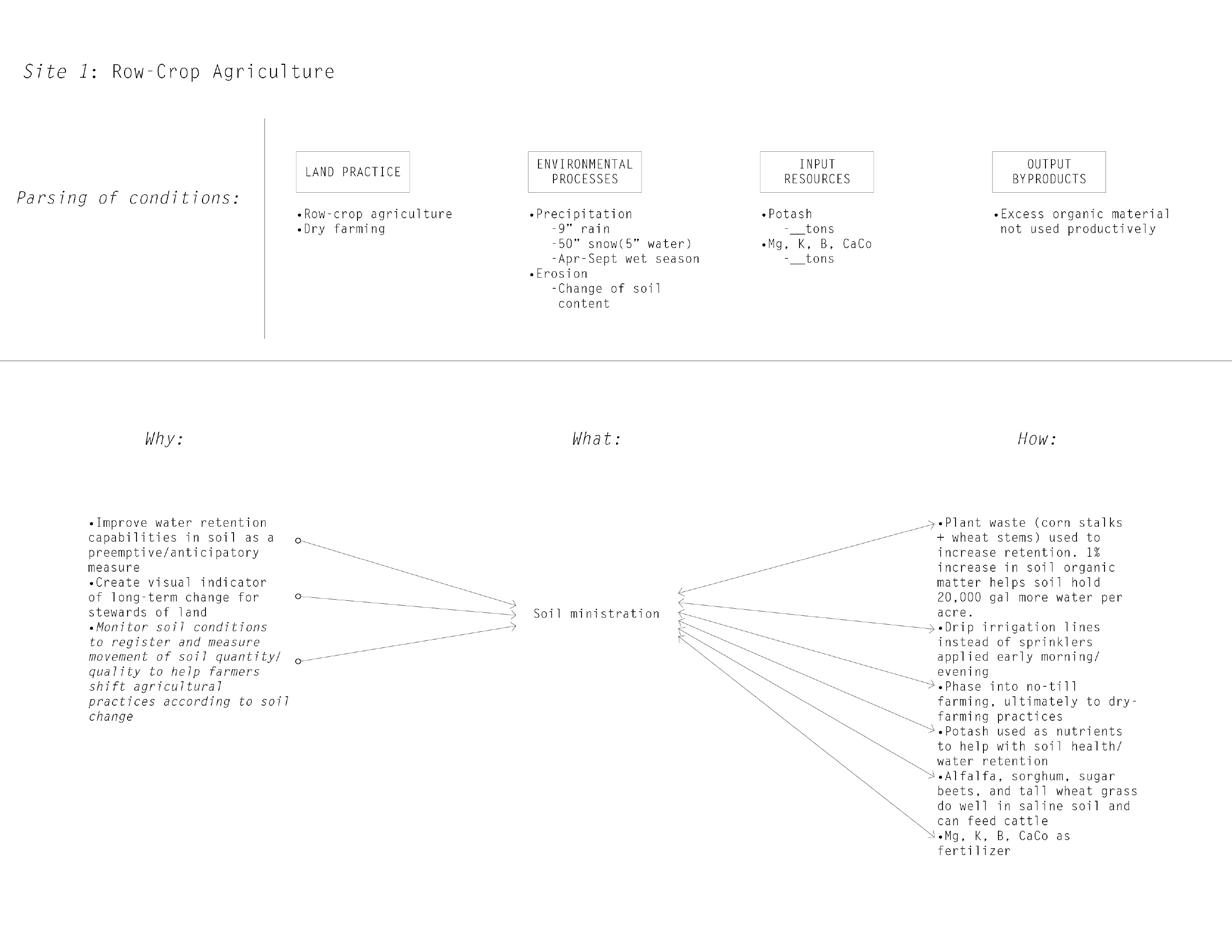

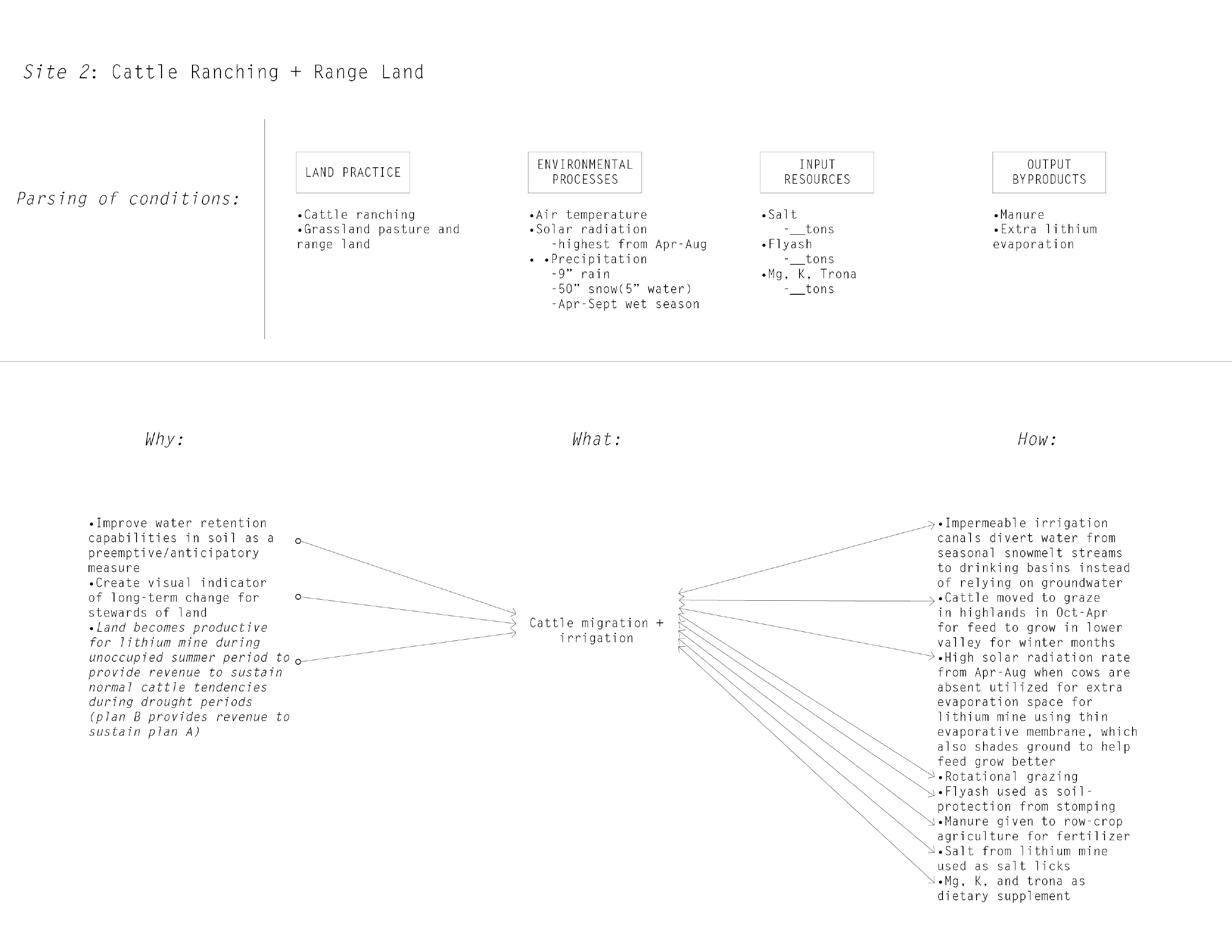

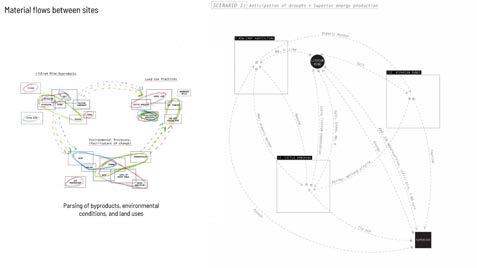

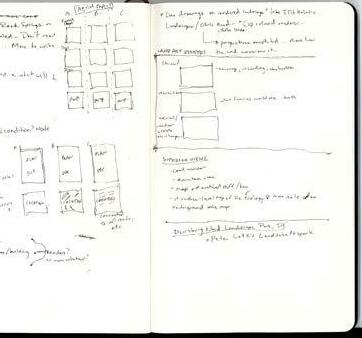

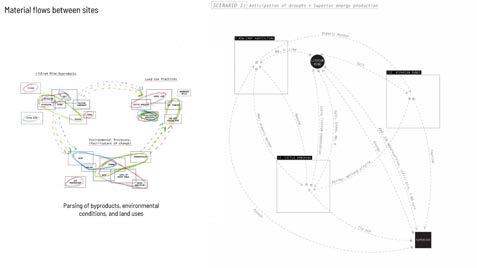

PARSING OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROCESSES, LAND PRACTICES, AND LITHIUM MINE BYPRODUCTS ACROSS THREE SITES

99

VII Byproducts and Choreography

100

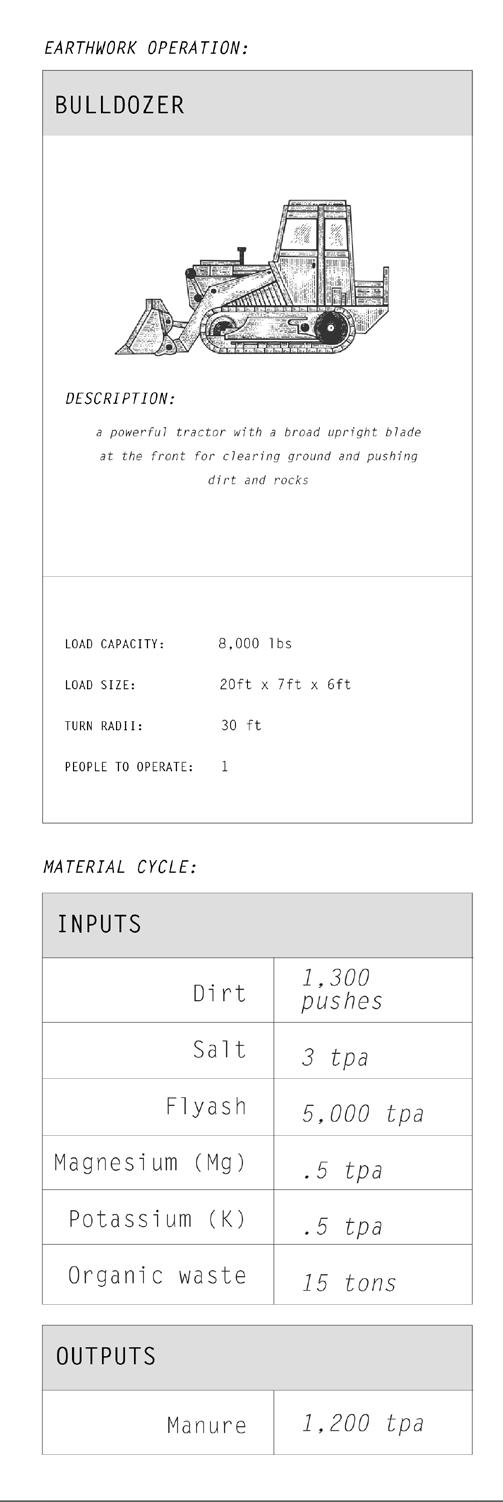

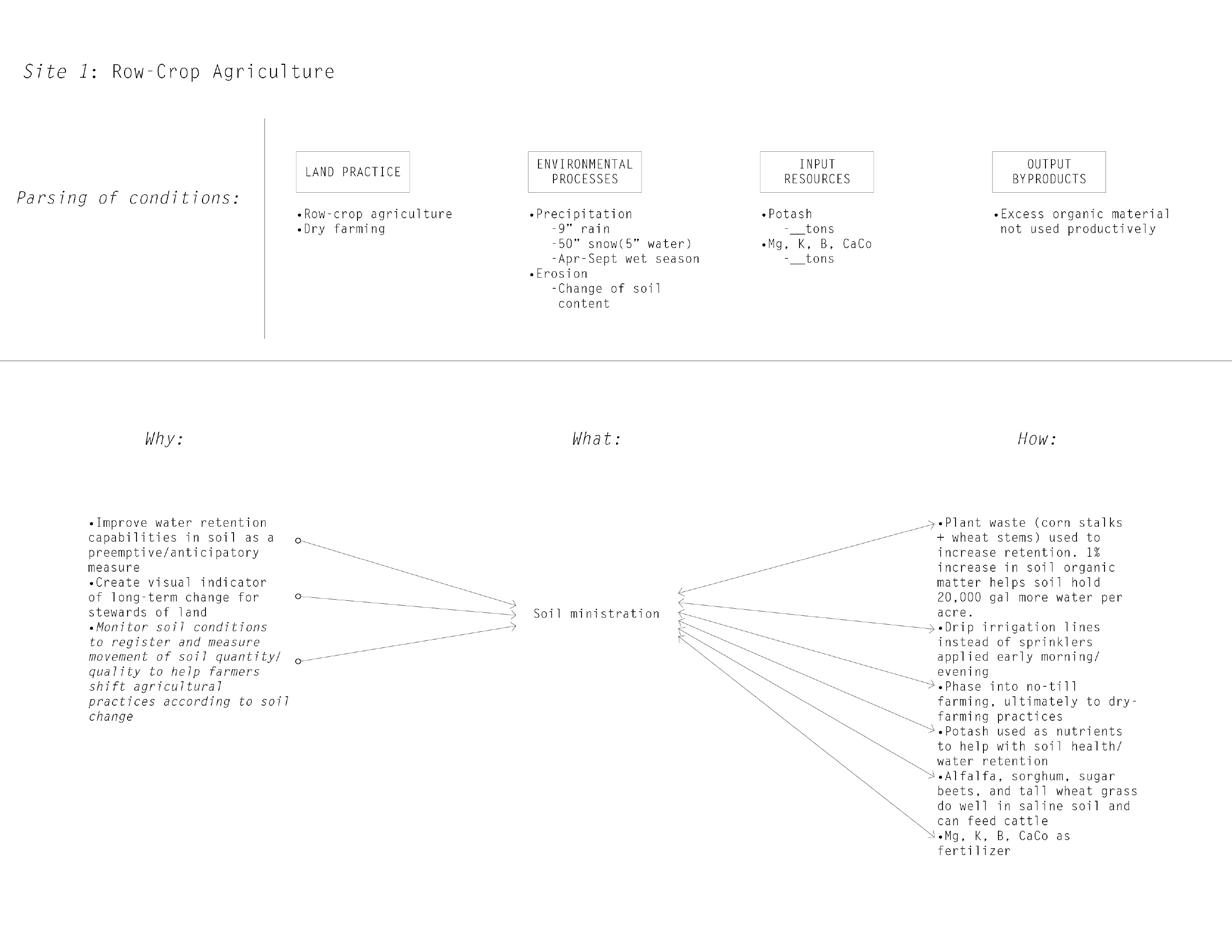

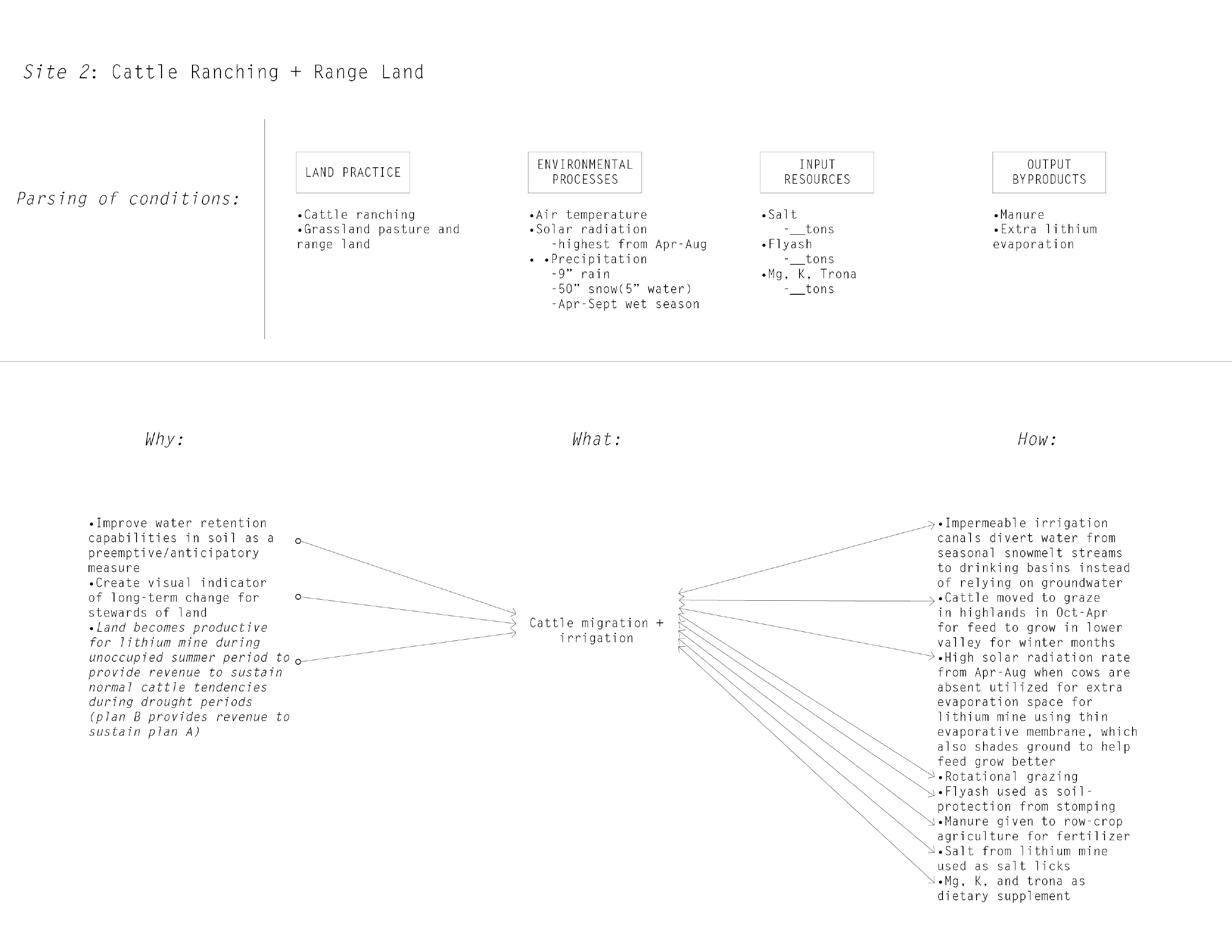

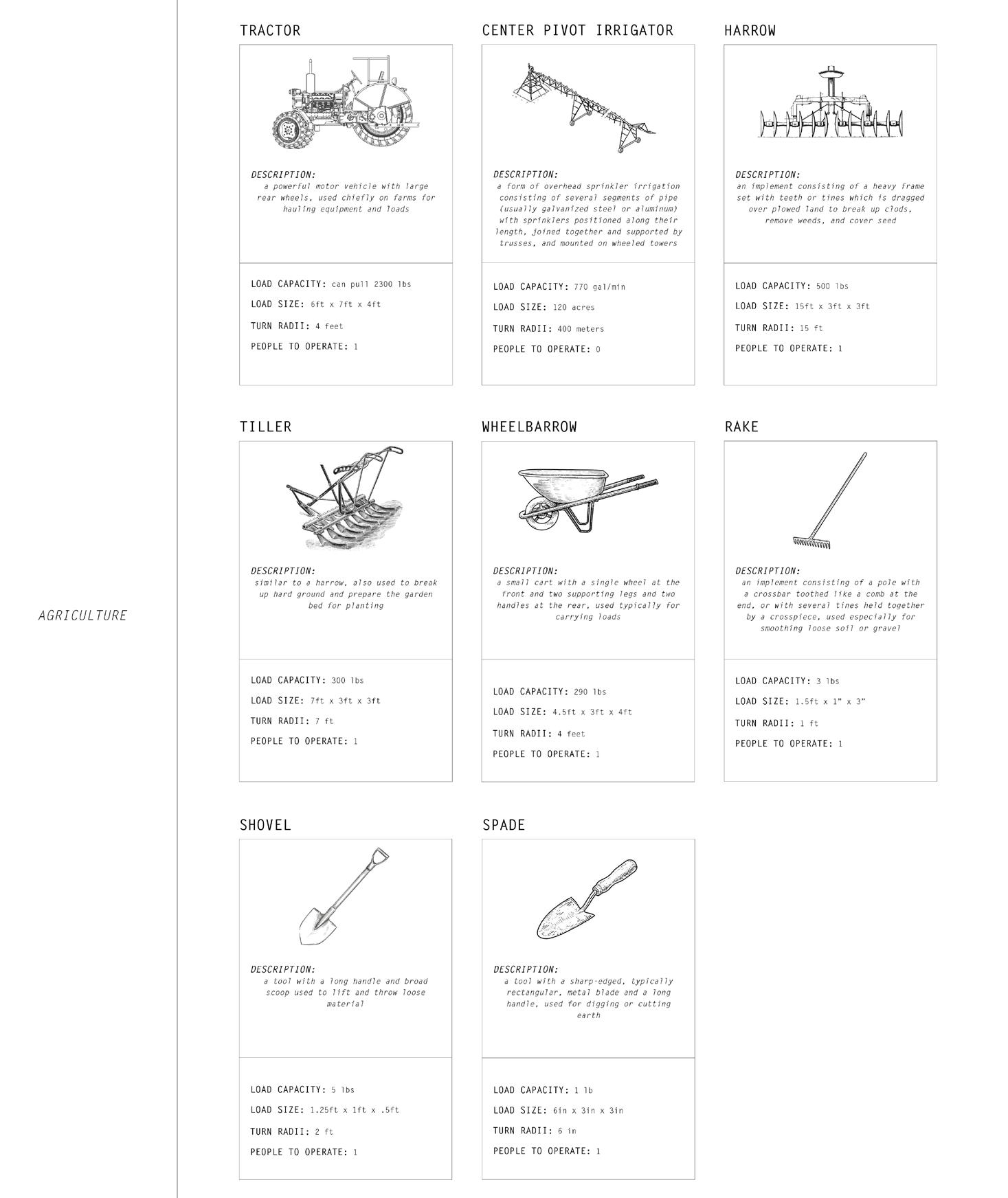

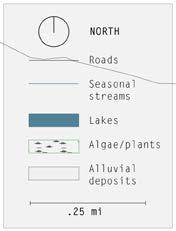

DESIGN AND RESOURCE STRATEGIES FOR AGRICULTURE AND CATTLE RANCHING

Design strategies for agriculture and cattle ranching consider land practices, environmental conditions, and input/output resources.

101

VII Byproducts and Choreography

102 1 mi

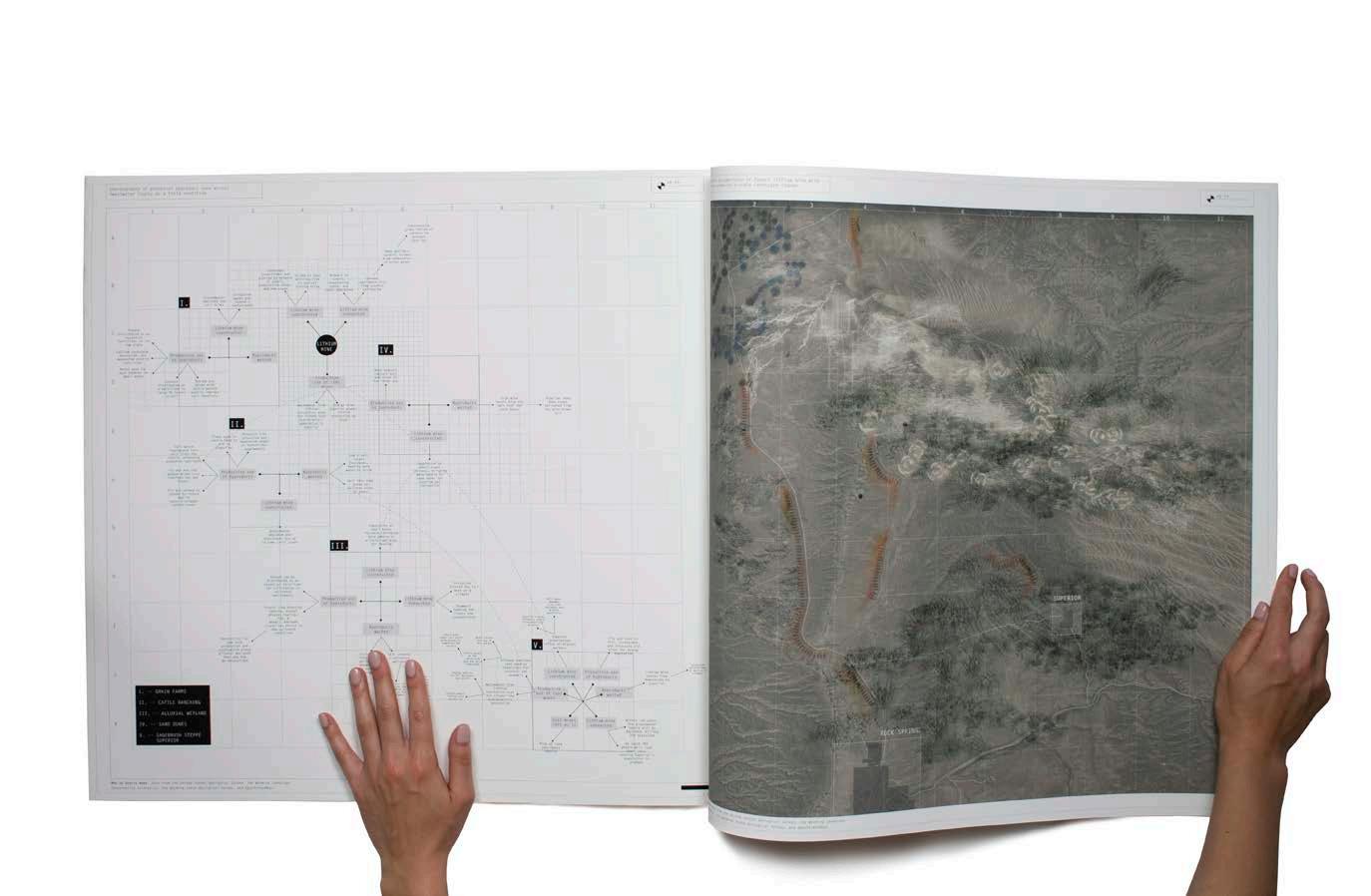

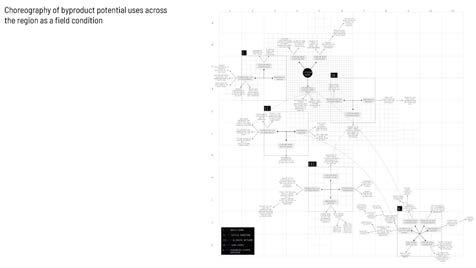

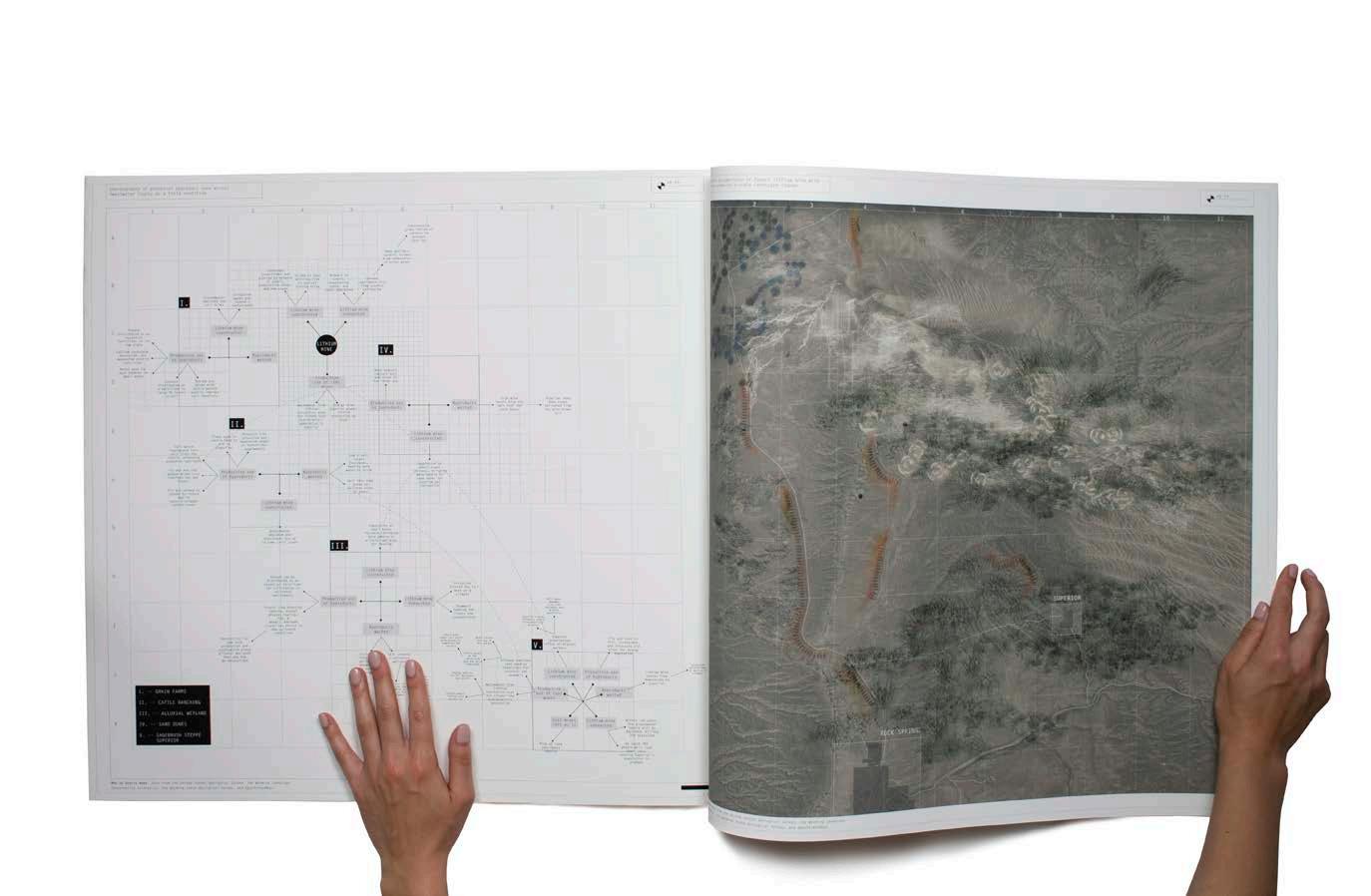

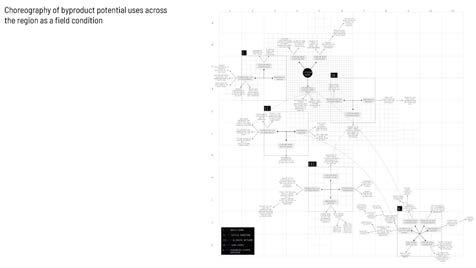

CHOREOGRAPHY OF POTENTIAL BYPRODUCT USES ACROSS SWEETWATER COUNTY AS A FIELD CONDITION

Excess materials are choreographed as a field condition onto different typical landscapes and practices. The initial process built and played out different scenarios to see how the landforms can anticipate and interact with different possible futures and remain productive. As a result, possible lateral activities can now develop alongside better lithium practices.

103

VII Byproducts and Choreography

104

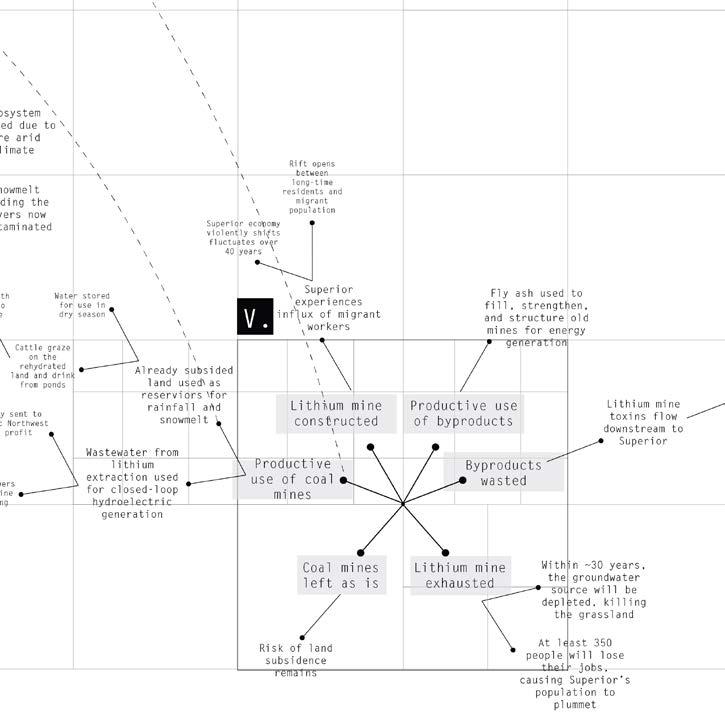

MATERIAL AND OPPORTUNITY FLOWS BETWEEN SITES OF INTEREST

The thesis parses byproducts, environmental processes, and land uses onto the 4 sites. The output of one agent serves as the input for the other, making circular that which is usually forgotten.

105

VII Byproducts and Choreography

The thesis manipulates the capitalist structure to create a beneficial, poetic method of being entrepreneurial where excess is rendered visible.

106 VIII

LABOR AND CAPITAL

Stewardship Linked With Labor and Capital

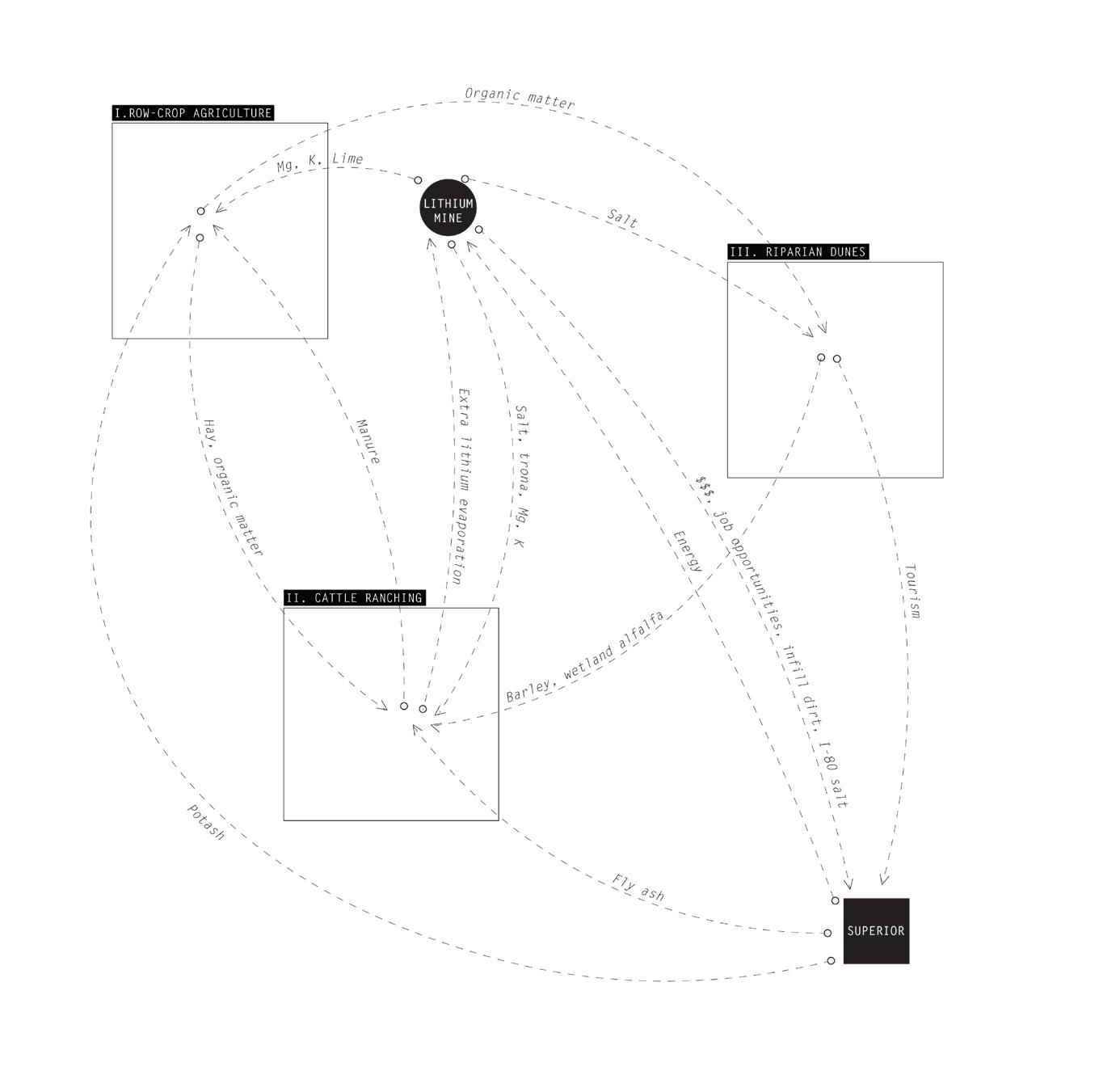

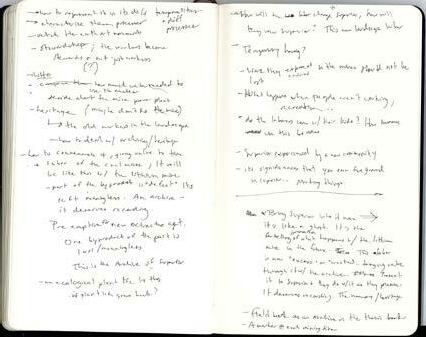

The thesis rearranges the excess from capitalism, both labor and byproducts, as an environmentally reparative gesture toward a landscape scarred by histories of resource extractive practices. In making connections between what has been kept discrete, the concept of stewardship is linked with labor and capital. Involving a diversity of stakeholders, both organizational and individual, is critical in making the landscape of extraction matter to more people and involves people who have the authority to make a difference. The capitalist structure is manipulated to create a beneficial, poetic method of being entrepreneurial where excess is rendered visible.

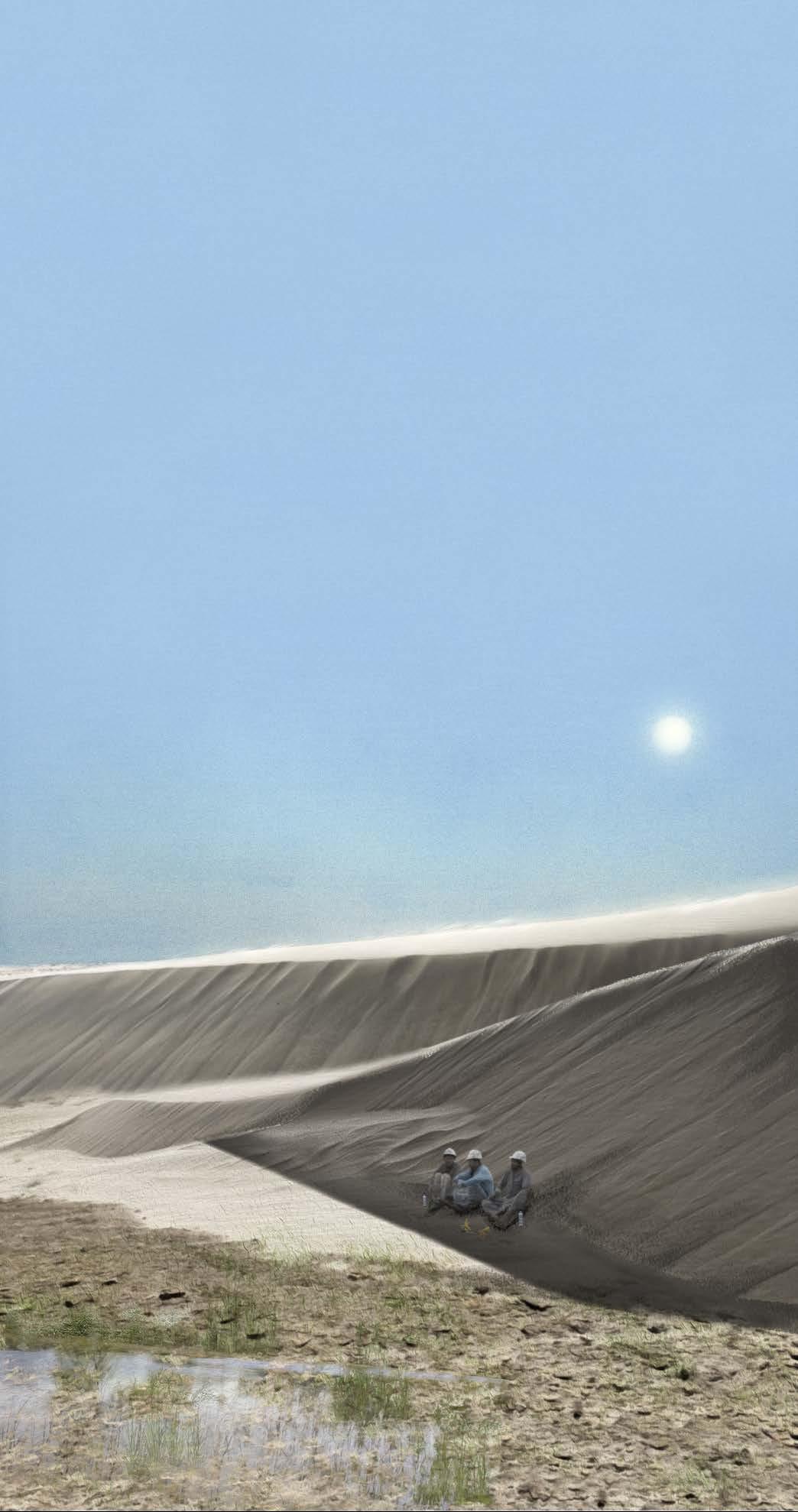

The laborers in this scenario are not just construction workers, they are stewards of the landscape developing a care for it over time. Surplus labor from the lithium extraction process is seen as one important stakeholder as well, who would live with and experience the various landforms, including their formation and transformation over time. They are a new community for whom Superior becomes a culturally significant landscape. A new relationship of concern for the landscape develops. An intergenerational relationship also develops, since the building of the landforms generates jobs over a 100 year time frame. The children of the 1940s-1950s coal miners have a different care and relationship with the landscape than the lithium stewards.

Apart from human labor, the earth, geologic forces, and the weather are conceptualized into labor of the atmosphere as the landforms change states. This is not a positive labor force, per se, as the atmosphere works against the humans in the maintenance of landforms. Hindering and interrupting the process, the weather pushes contaminants further into the landscape.

107

VIII Labor and Capital

108

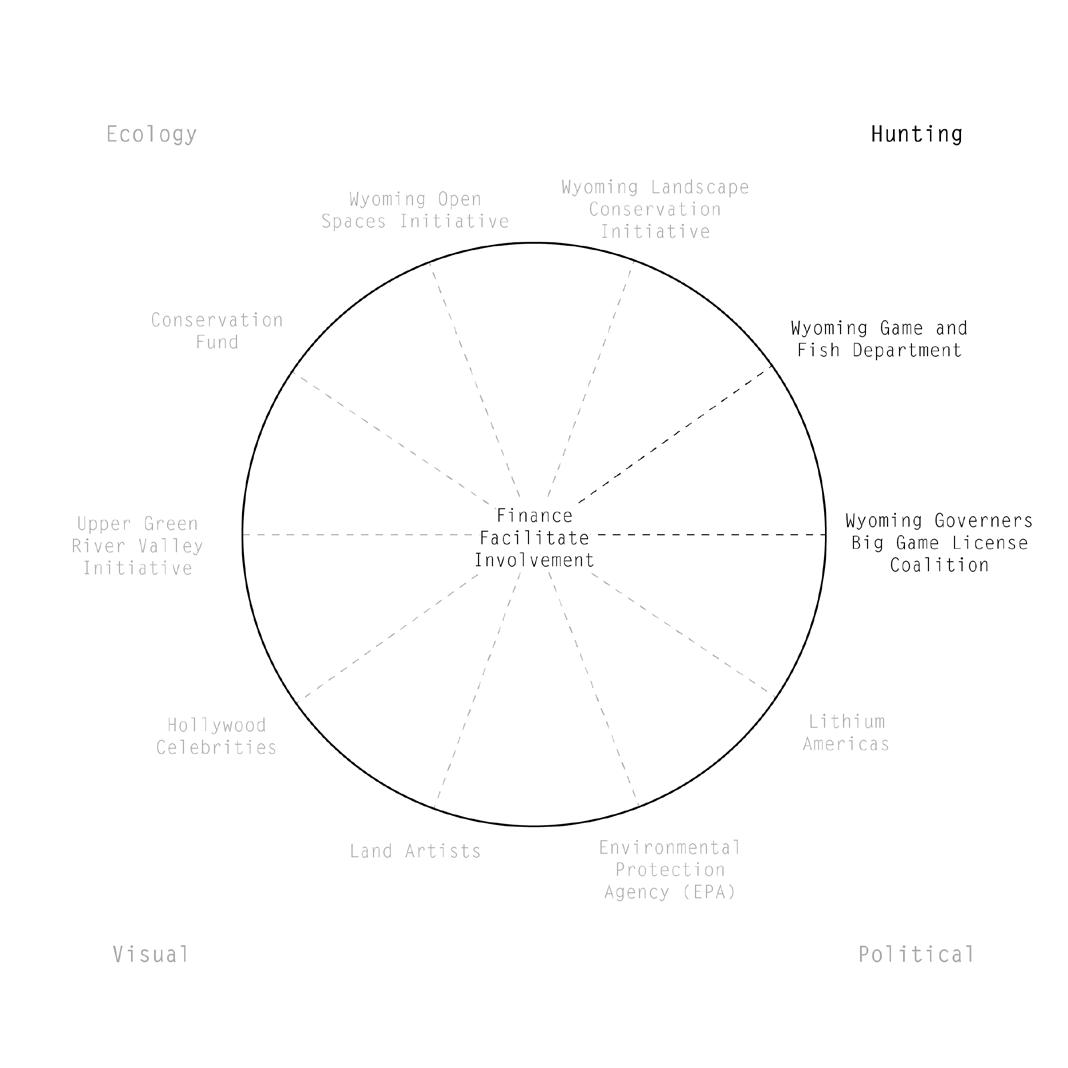

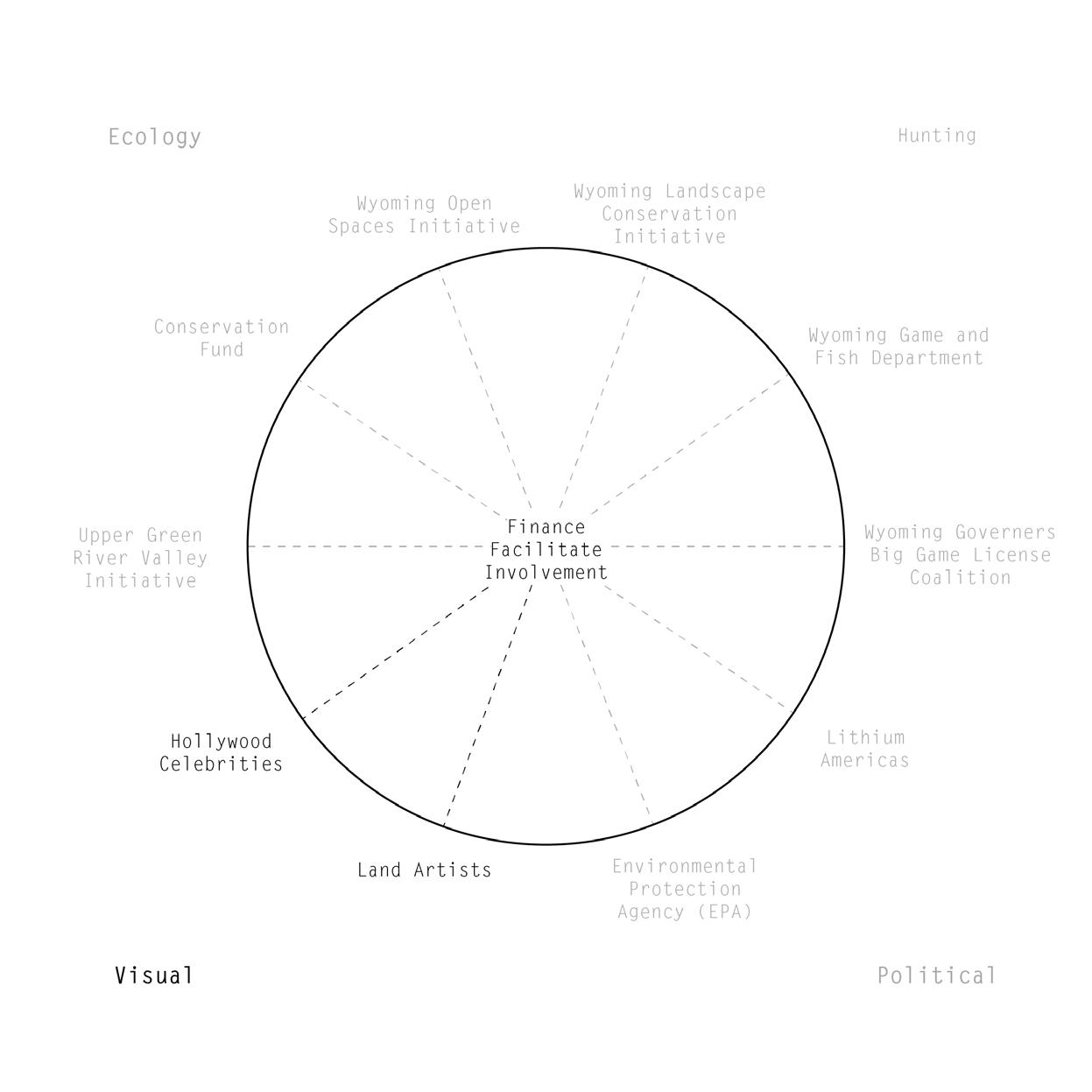

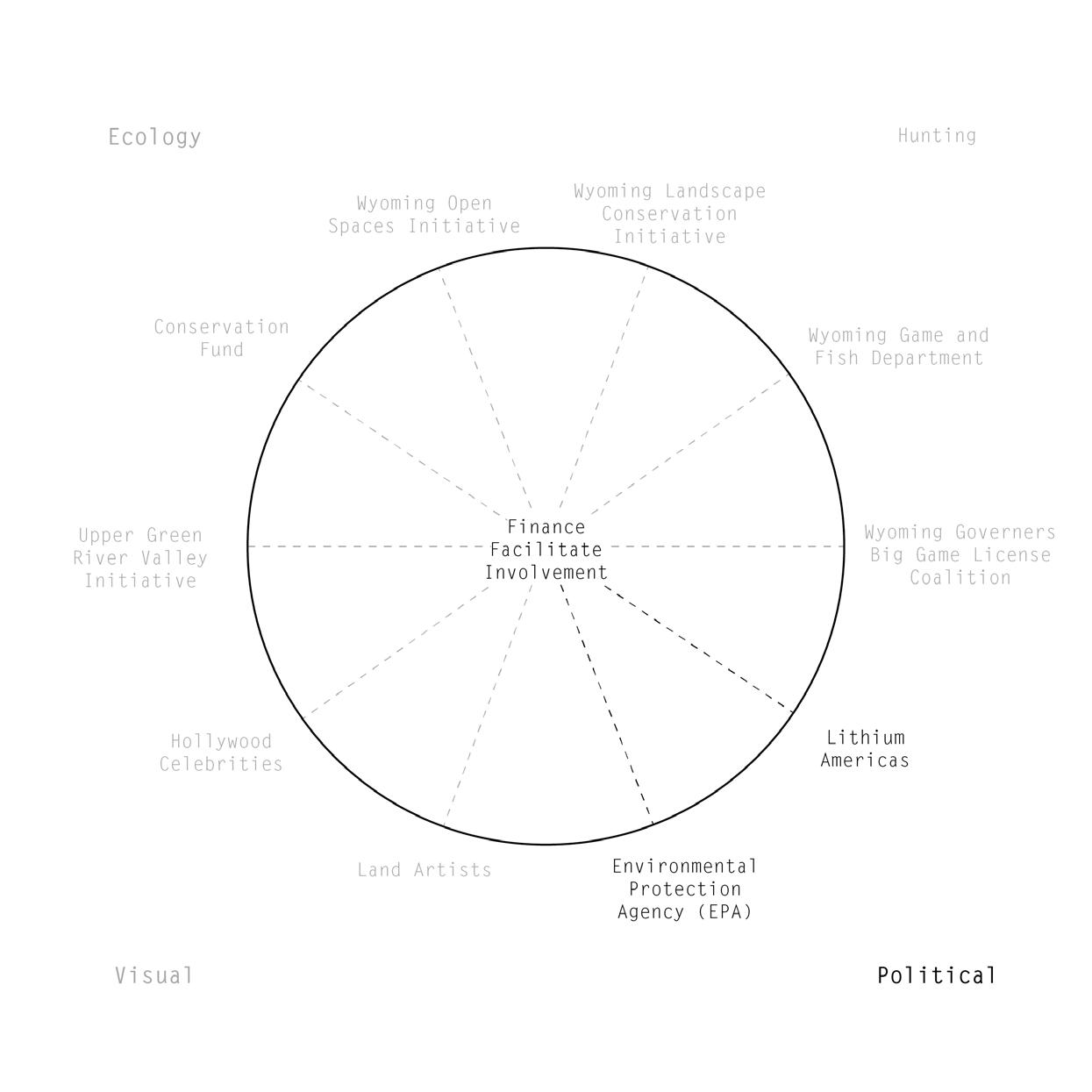

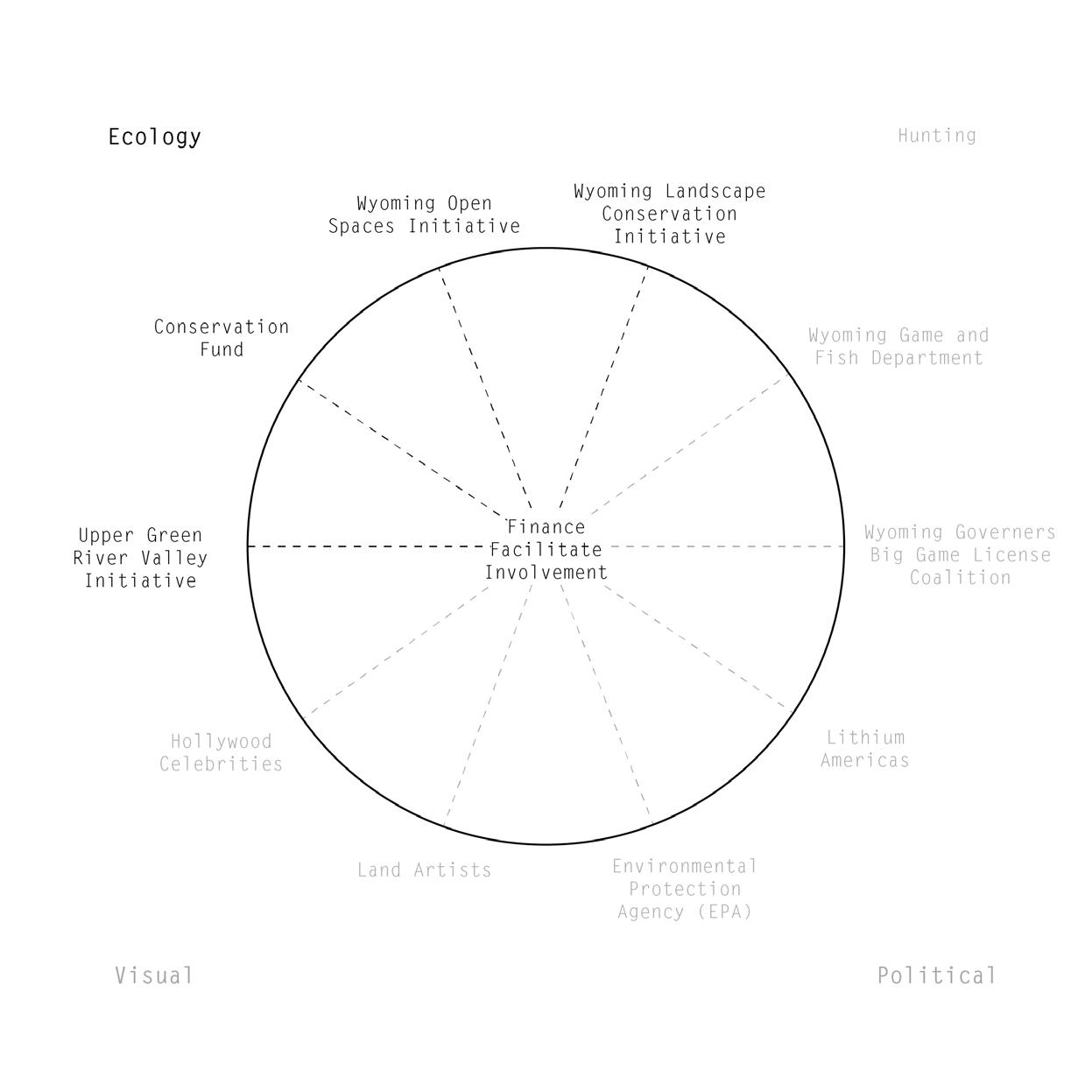

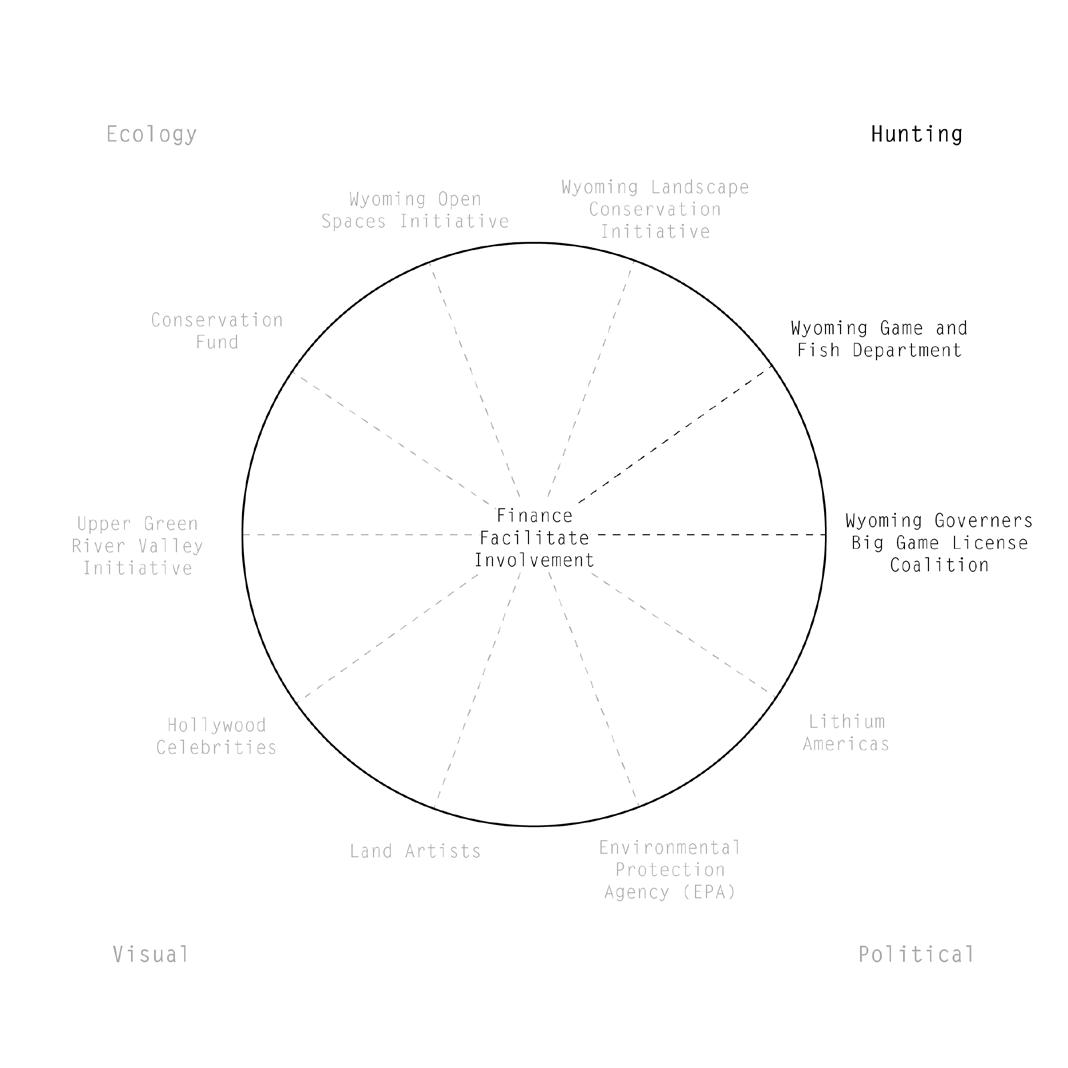

INVOLVEMENT OF OUTSIDE GROUNDBASED CONSTITUENTS

To facilitate and finance the process of building these landforms the thesis proposes the involvement of outside constituents. The involvement of the Wyoming Conservation Initiative, and even the conservative Wyoming Governor’s Big Game Coalition helps to draw in as many people and diversities of organizations as possible to promote longevity.

109

VIII Labor and Capital

110

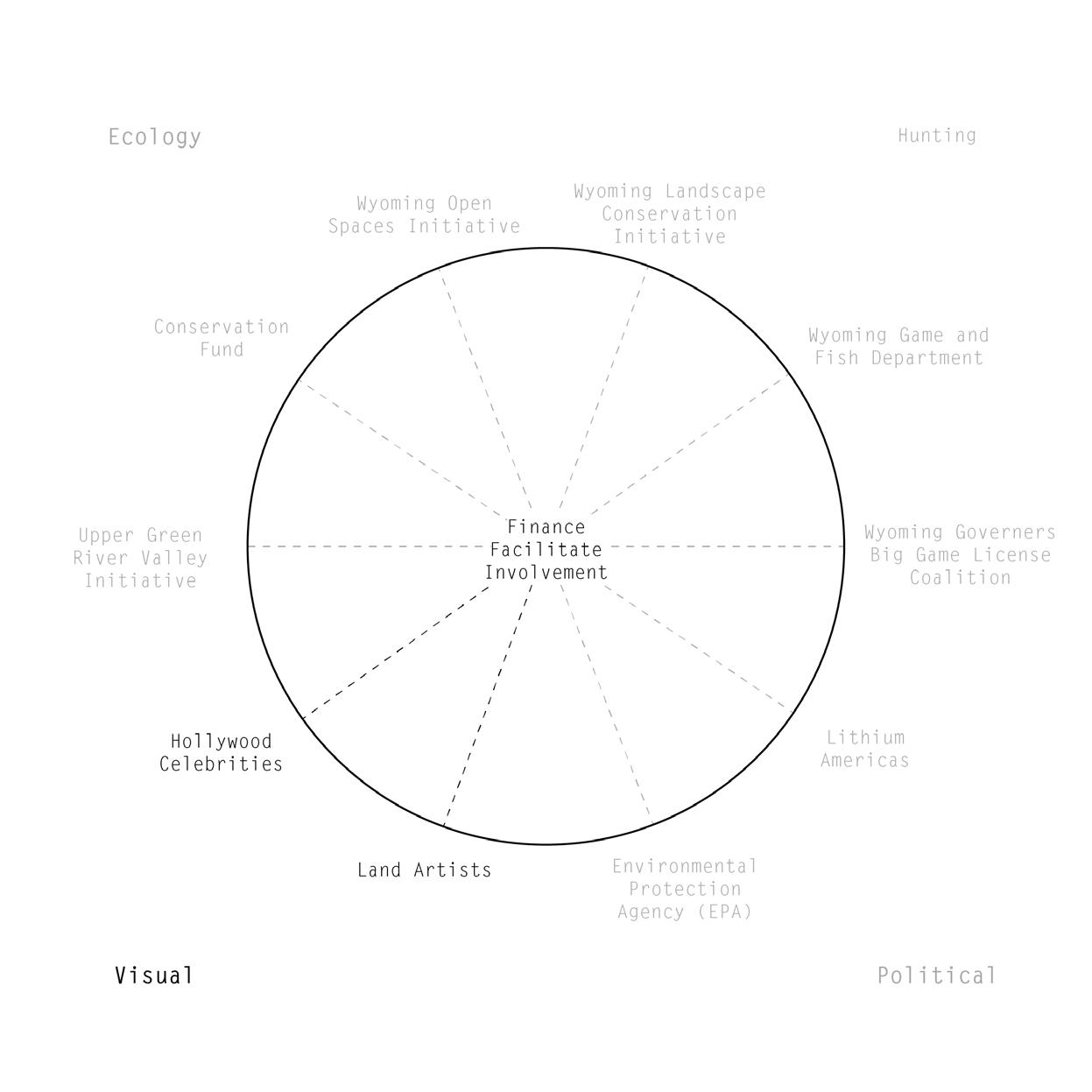

INVOLVEMENT OF OUTSIDE AERIAL CONSTITUENTS

Apart from the constituents that are more interested in ecological factors, some stakeholders experience the landforms visually aerially. For instance, a Hollywood celebrity pays $10 to sponsor a crane bucket of dirt, and in return receives a satellite image as the landscape undergoes change. This has a dual purpose in that the landforms render visible and measure the spread of contamination through the landscape.

The coalescence of eye level and aerial stakeholders is required to see the whole picture.

111

VIII Labor and Capital

112 Mining Law of 1872 information

2022)

from: (Robbins

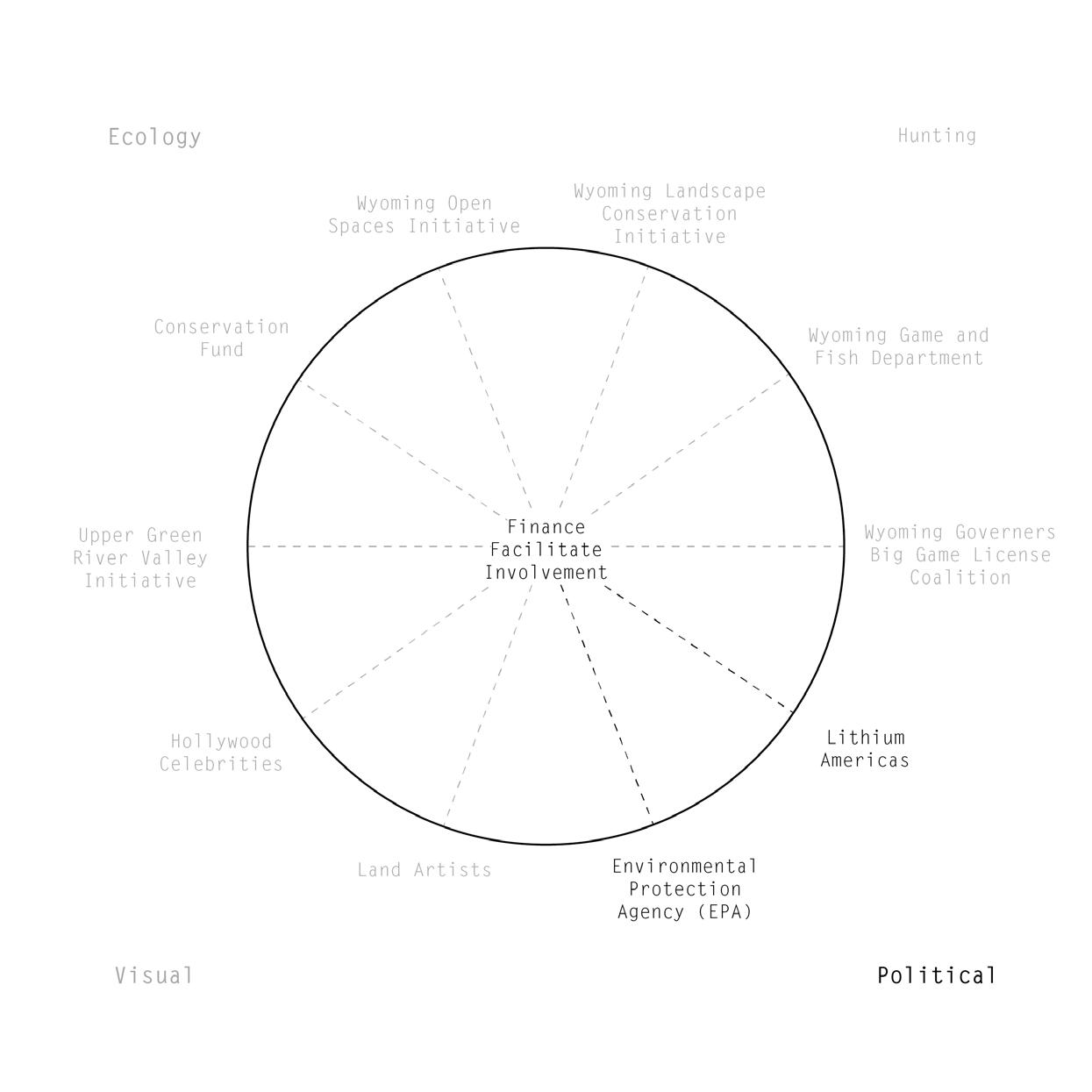

LITHIUM AMERICAS AS LOOPHOLE STAKEHOLDER: MINING LAW OF 1872

Even the company that owns and operates the mines, Lithium Americas, can be involved. as the still-in-place historic Mining Law of 1872, which allows miners to pay no royalties for minerals they dig from federal land, is currently being proposed to be reformed under the Biden administration. If the reform goes through, Lithium Americas in Wyoming could pay a royalty to the EPA since the minerals are publicly owned on Bureau of Land Management land. Part of the money could help recycle and purify the contaminants into their usable forms.

113

VIII Labor and Capital

“Land-use planning is primarily the responsibility of city and county governments that are empowered by state-level enabling legislation or land planning policy to preserve public health, safety, and welfare. Decisions about which land uses are permitted, their size, location, and compatibility, occur at the local government level, guided by citizen input and implemented by local elected officials.

In addition to guiding land-use decisions, planning also enables communities to promote economic development; protect private property rights, farmland, ranchland and historic areas; and make fiscally responsible decisions regarding community services and infrastructure needs.

There exists opportunity to both improve existing regulatory mechanisms and enhance current legislation with incentive-based strategies to better support economic growth, environmental resilience, and quality of life.”

114

Publicly owned land information from: (Hammerlinck, Lieske, Gribb, and

n.d.)

– Understanding Wyoming’s Land Resources: Land-Use Patterns and Development Trends by the Wyoming Open Spaces Initiative

Oakleaf

LAND OWNERSHIP AS DRIVER OF CHANGE

Land ownership is also a driver of change. The sites of intervention are publicly owned by the Bureau of Land Management. This enables the citizens to pressurize their political representatives for preferable land policies and protect private property from contamination.

115

VIII Labor and Capital

116

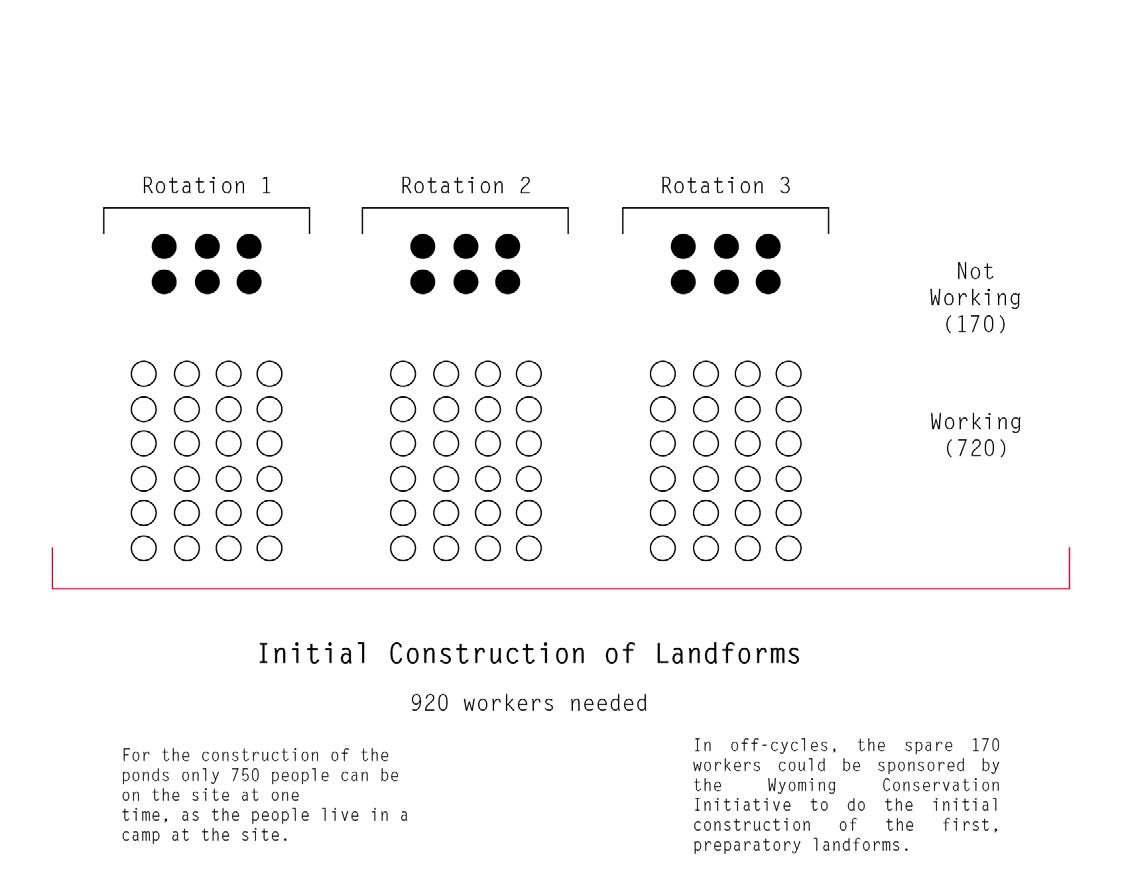

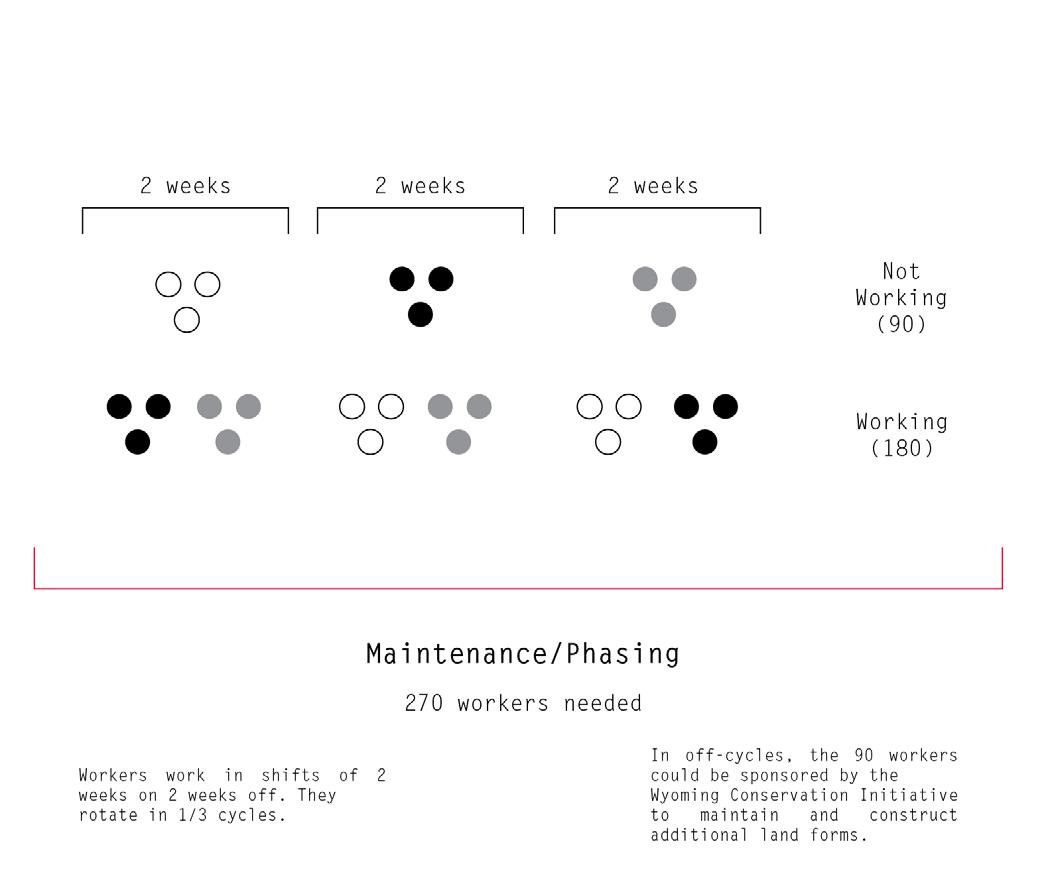

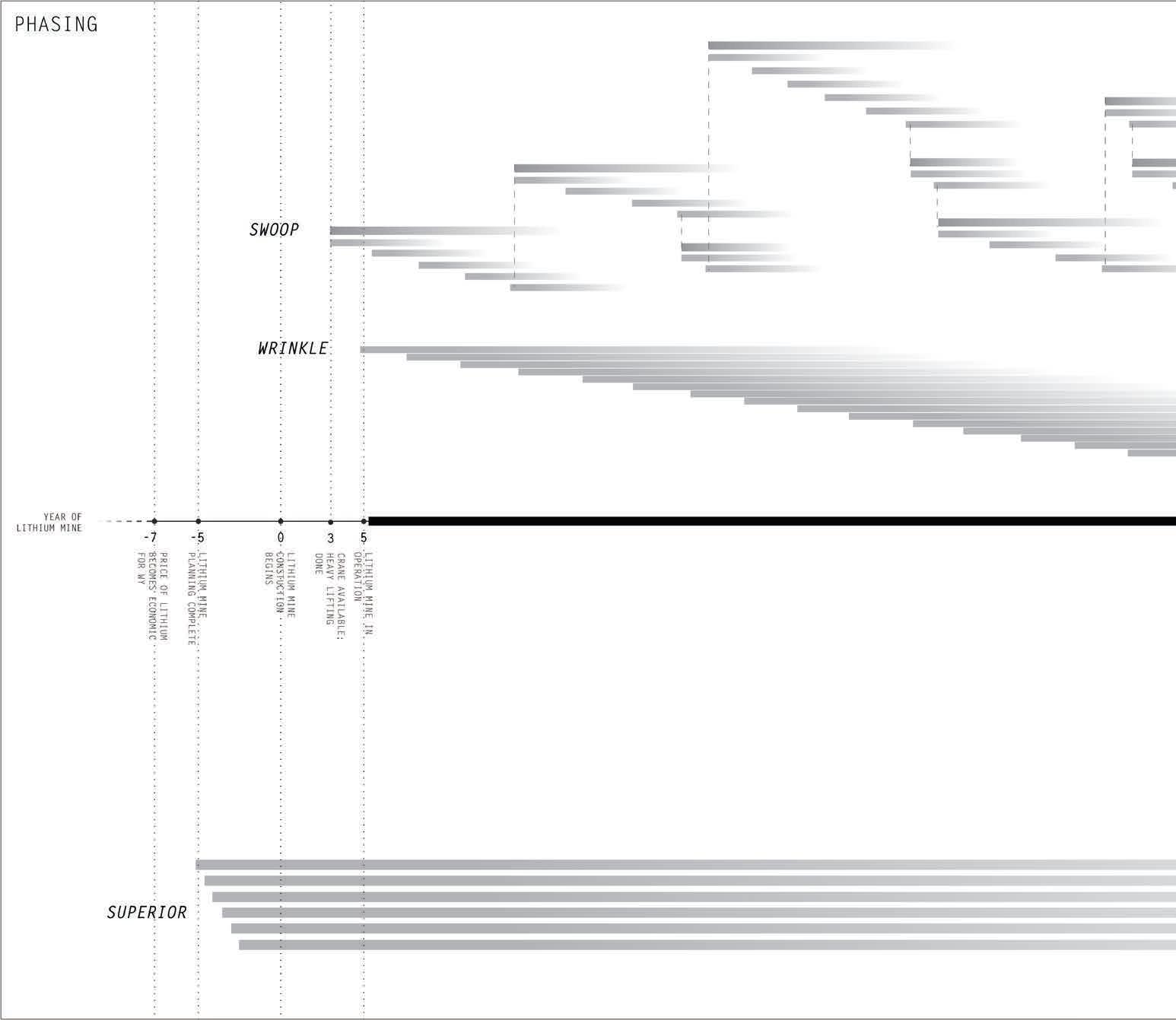

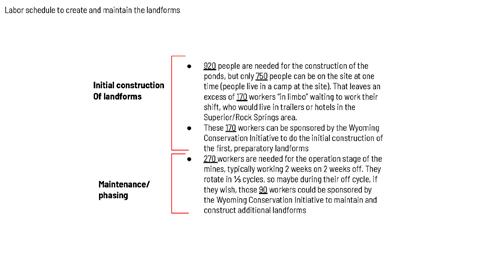

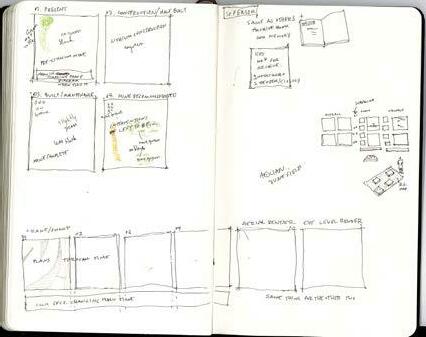

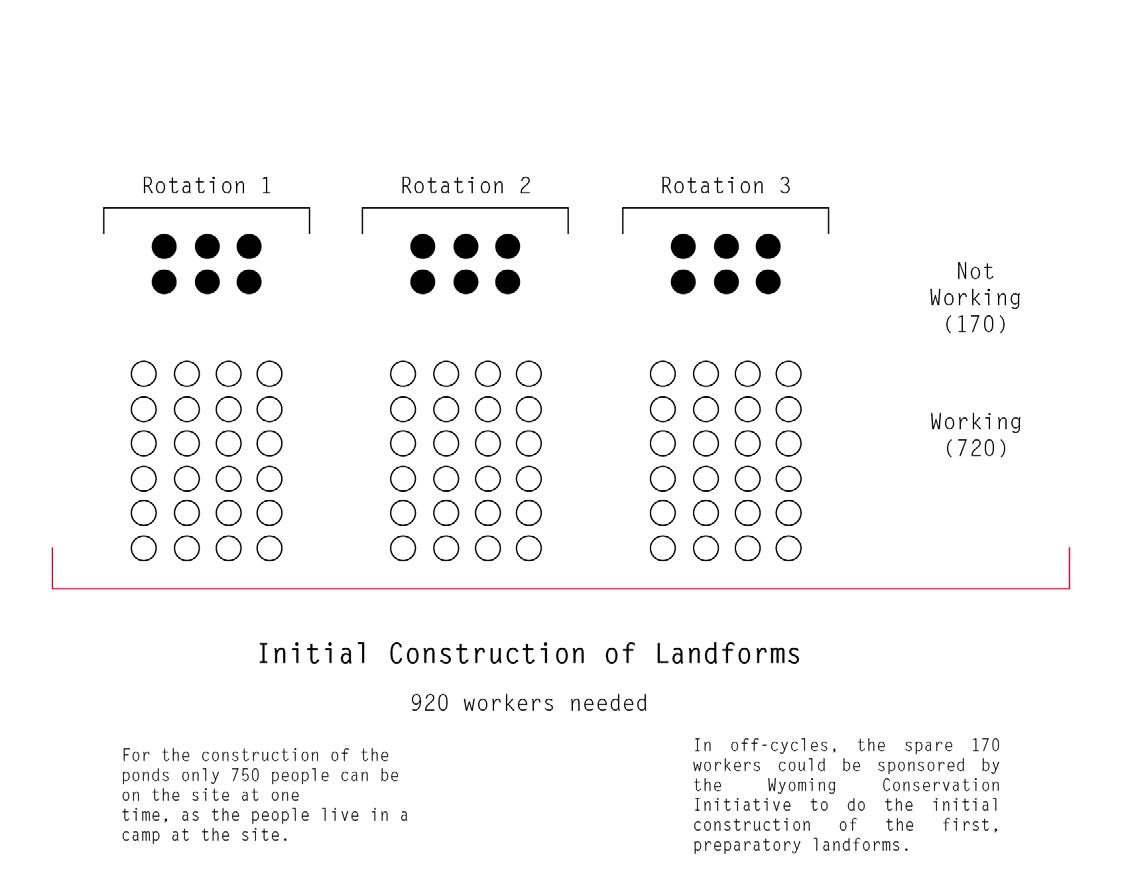

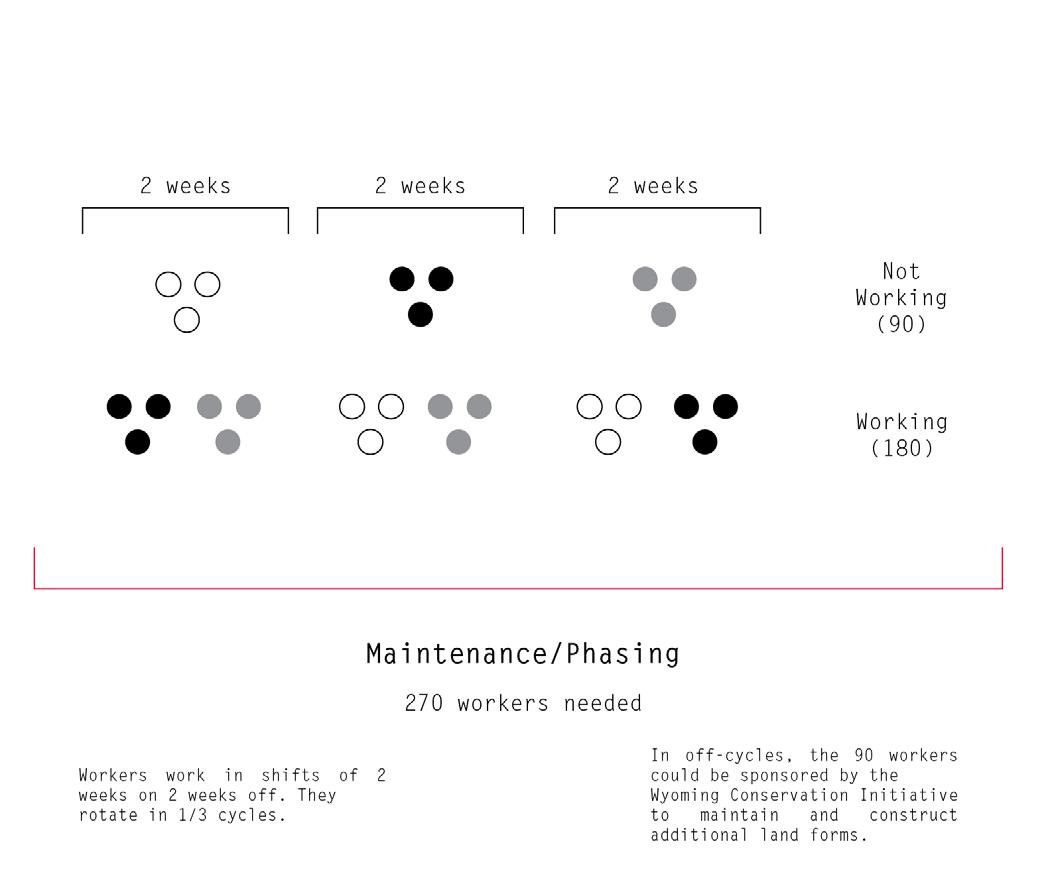

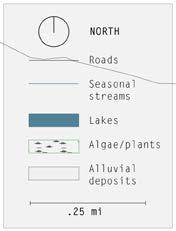

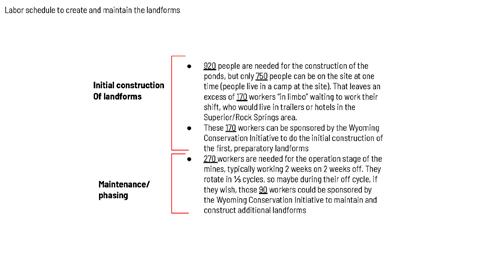

LABOR CYCLE FOR CONSTRUCTION AND MAINTENANCE OF LANDFORMS

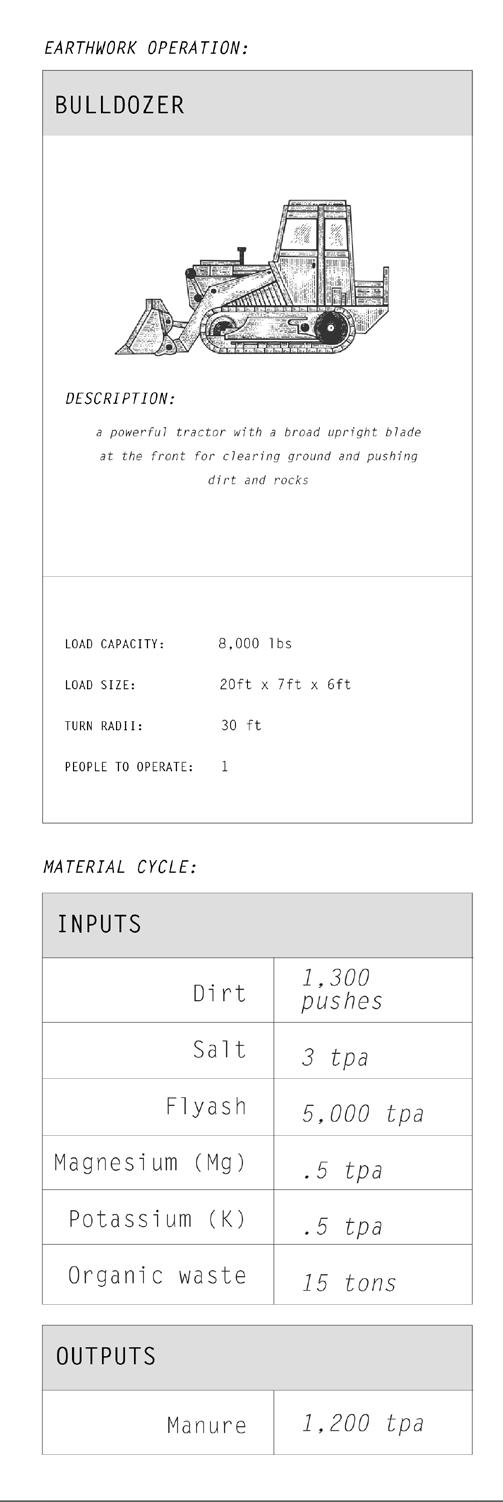

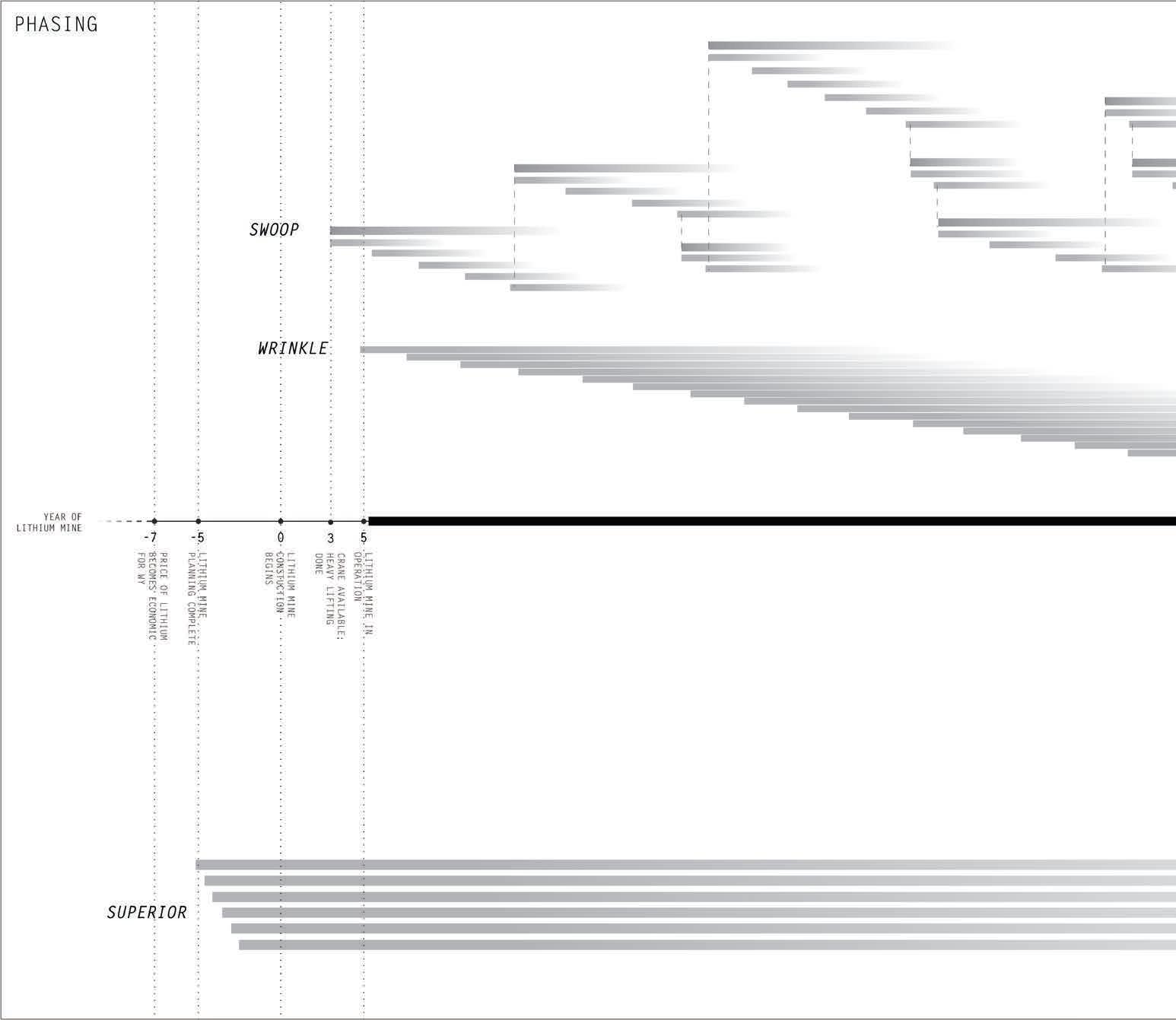

The labor to construct the landforms is composed of an excess of “in limbo” lithium mine workers due to their 2-week on 2-week off labor cycles. During their off cycles, the workers can be sponsored to construct and maintain the landforms. Lithium miners are now stewards, developing a sense of responsibility for the landscape.

The thesis rearranges the excess from capitalism, both labor and byproducts, as an environmentally reparative gesture toward a landscape scarred by histories of industrial resource extractive practices.

117

VIII Labor and Capital

118

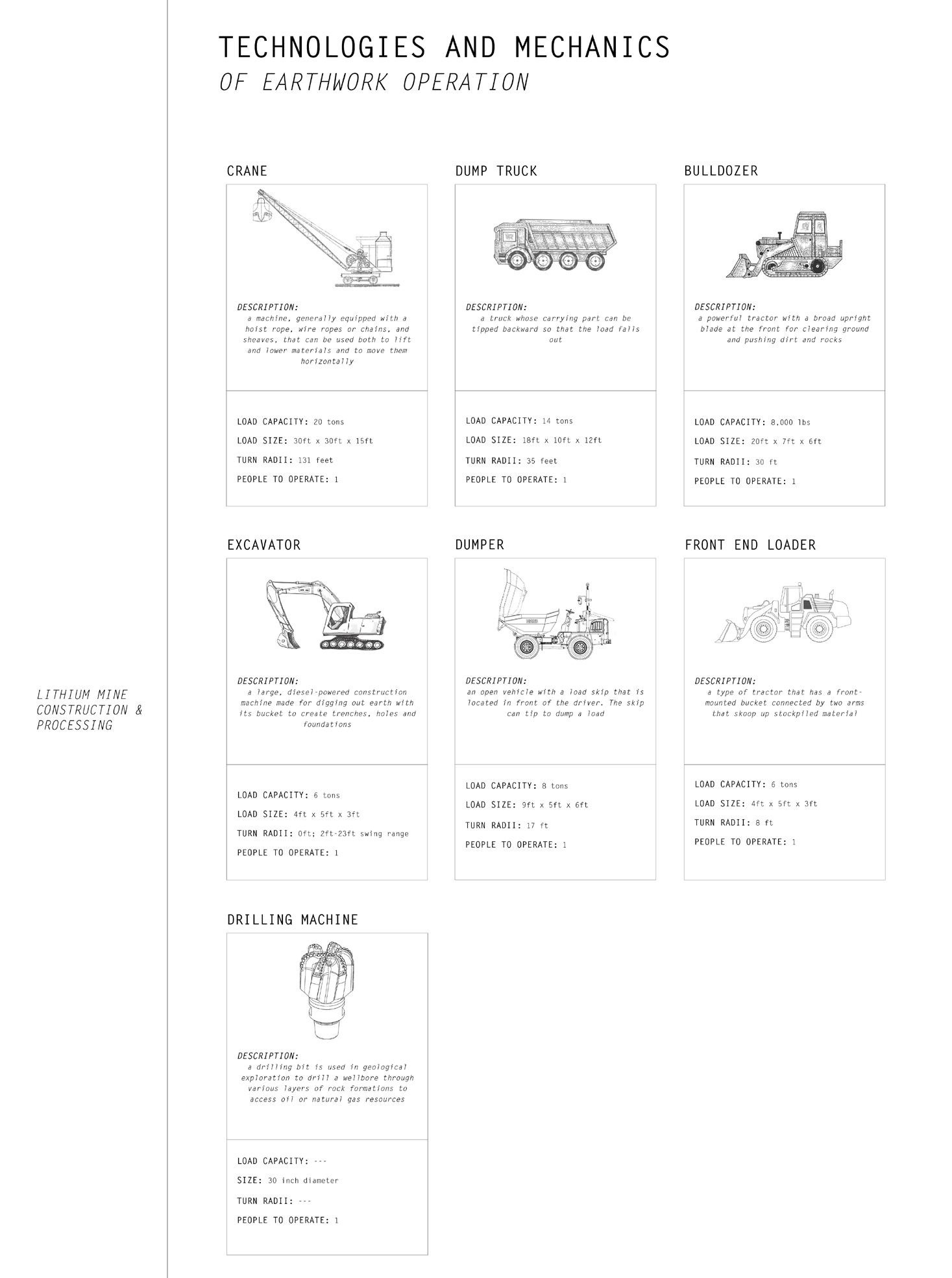

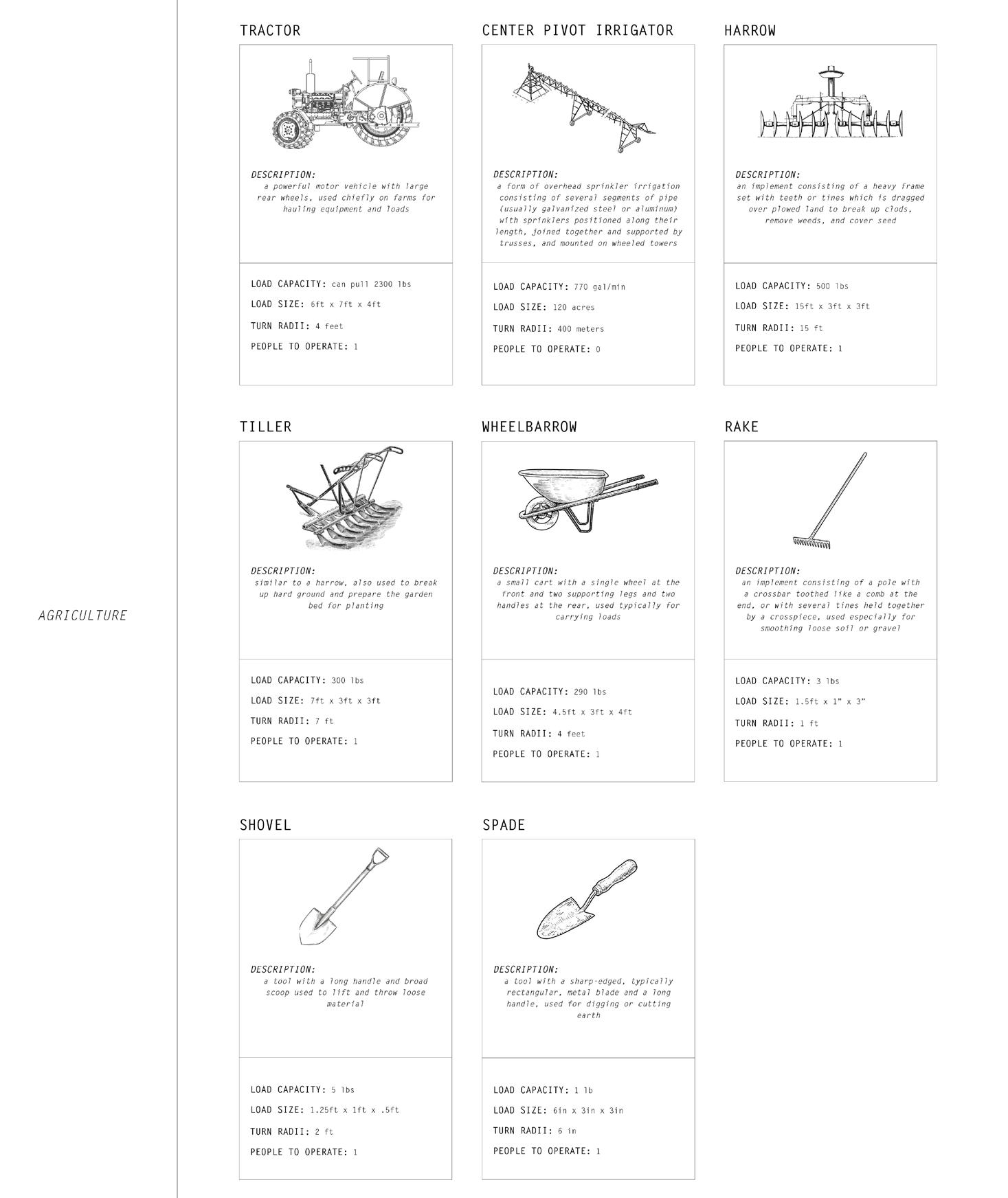

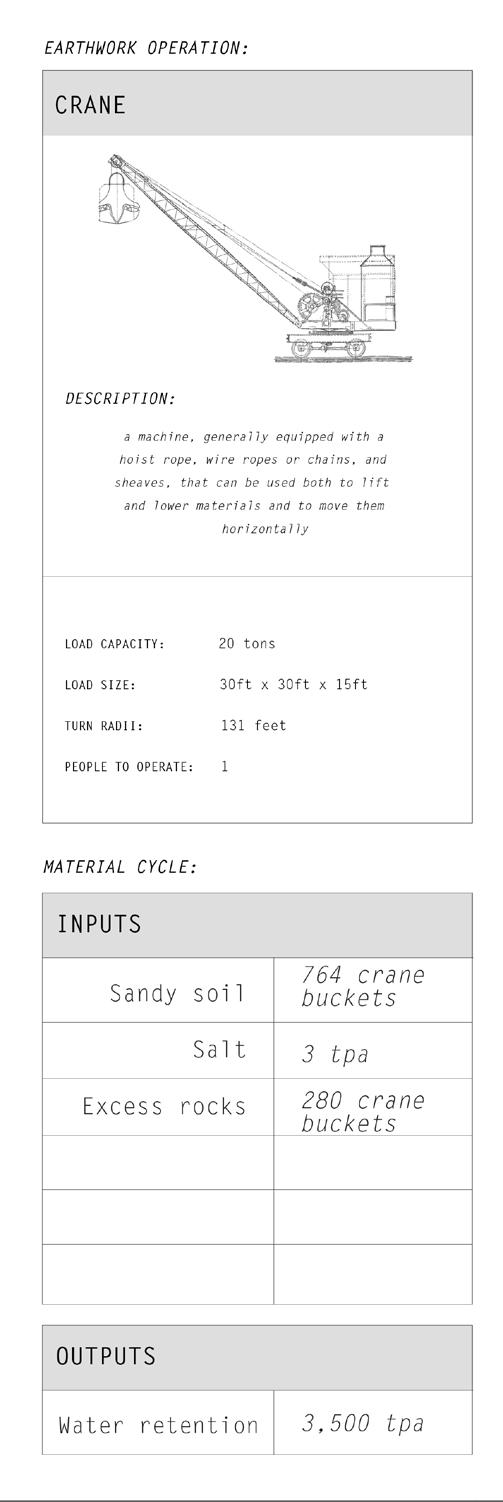

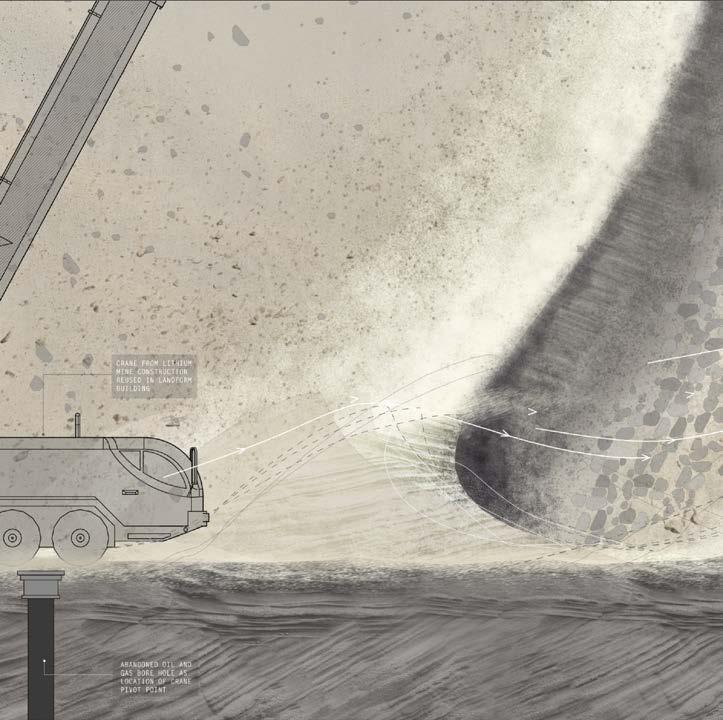

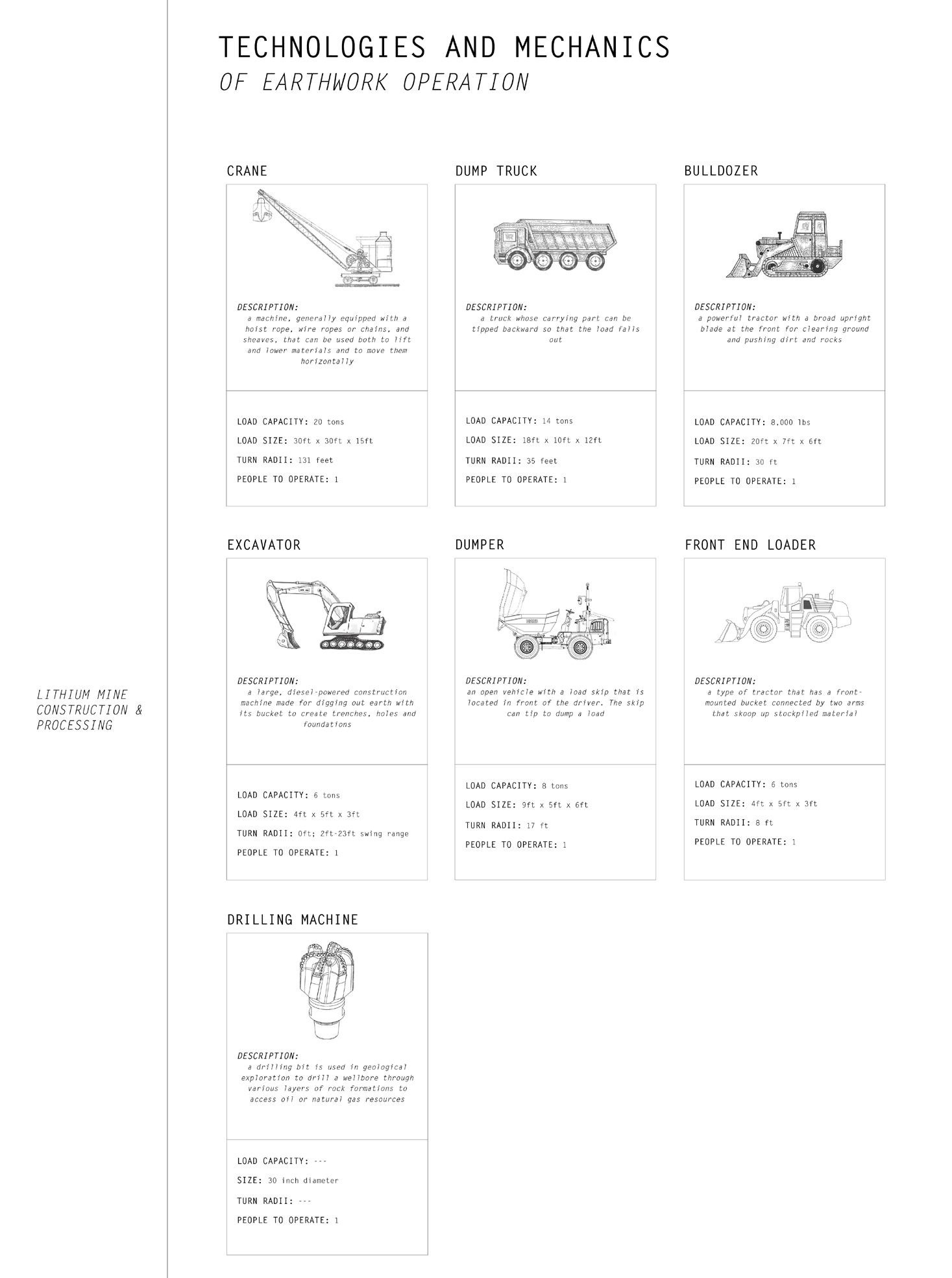

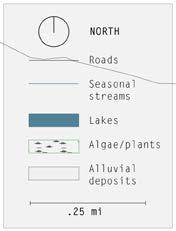

MECHANISMS OF LITHIUM MINE CONSTRUCTION USED TO BUILD LANDFORMS

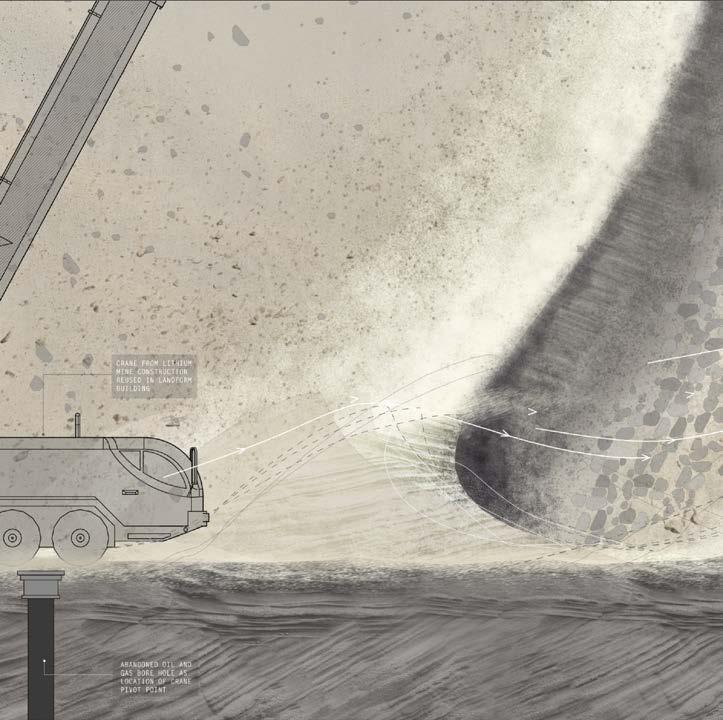

The construction and maintenance of the landforms reveal, expose, and undo lithium mine processes by utilizing the same mechanisms and machines that are used to build the ponds. Cranes and bulldozers are reused after their role is completed in mine construction.

119

VIII Labor and Capital

120

PHASE III

121

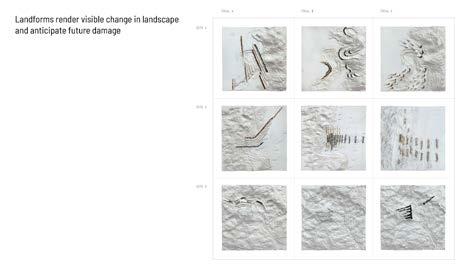

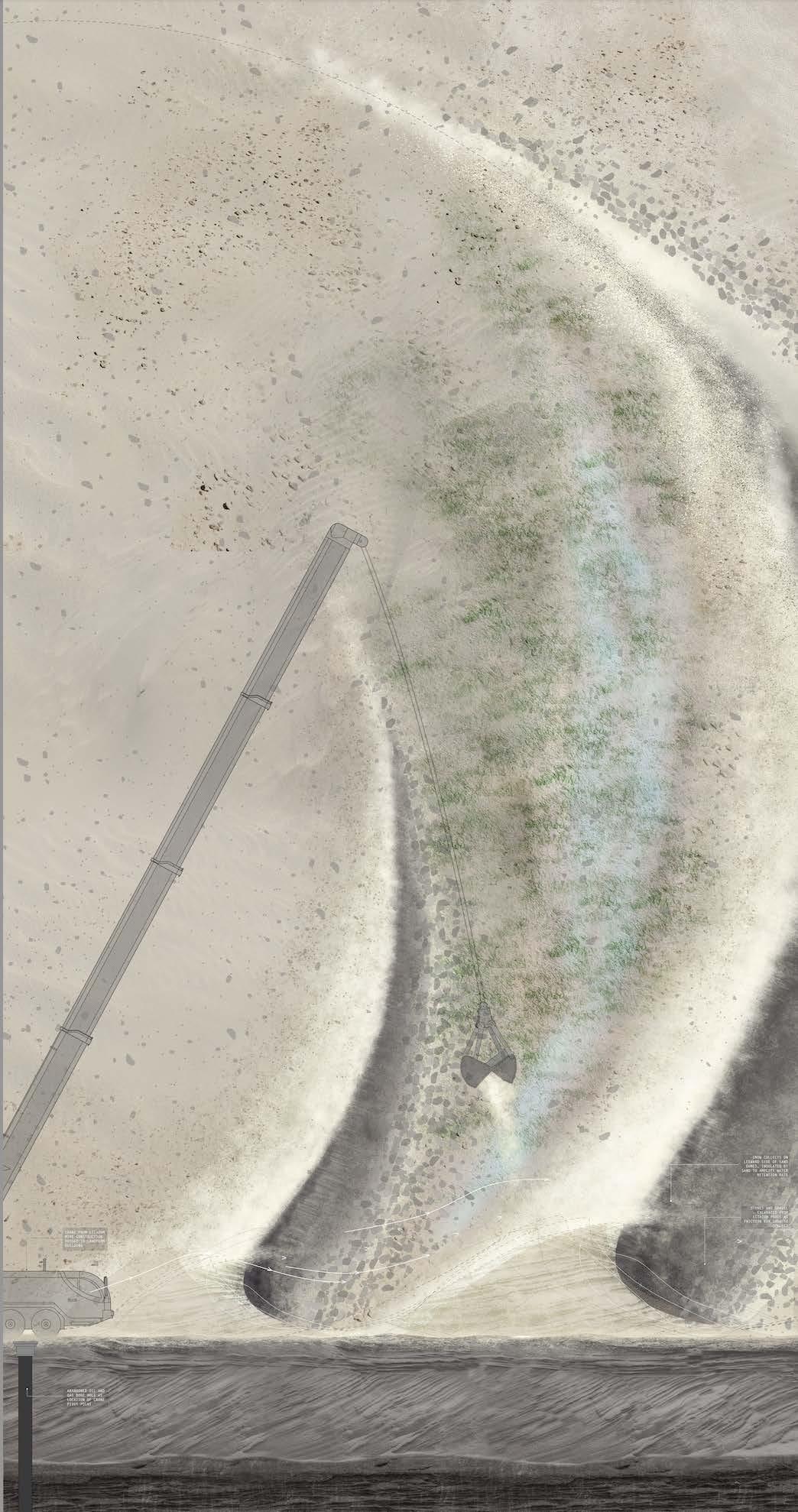

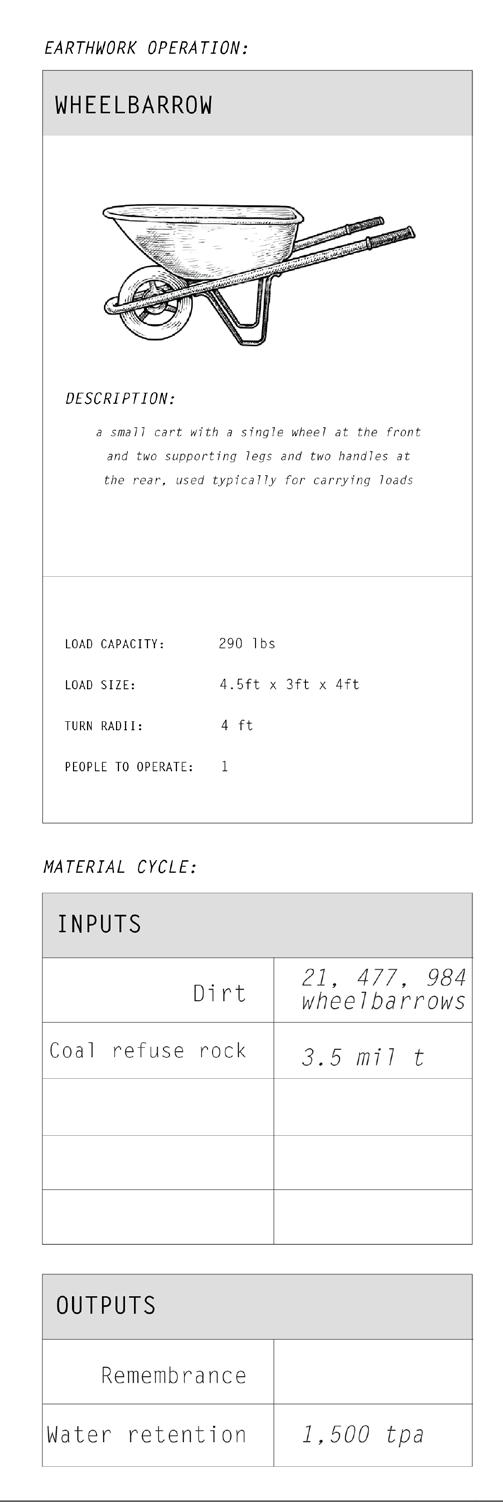

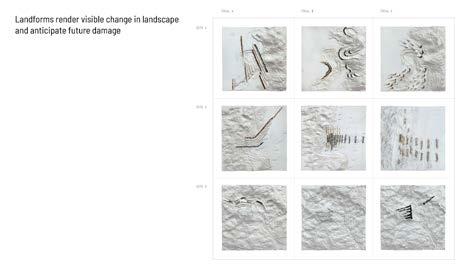

Designed landforms render visible landscape contamination, preemptively remediate future effects of the lithium mine, and reveal processes of lithium extraction.

122 IX

SITES OF STEWARDSHIP

Microclimates That Render Visible Change

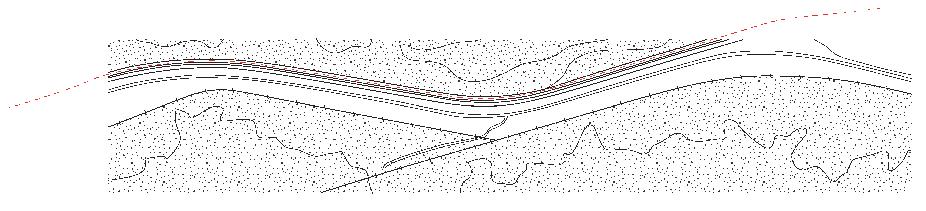

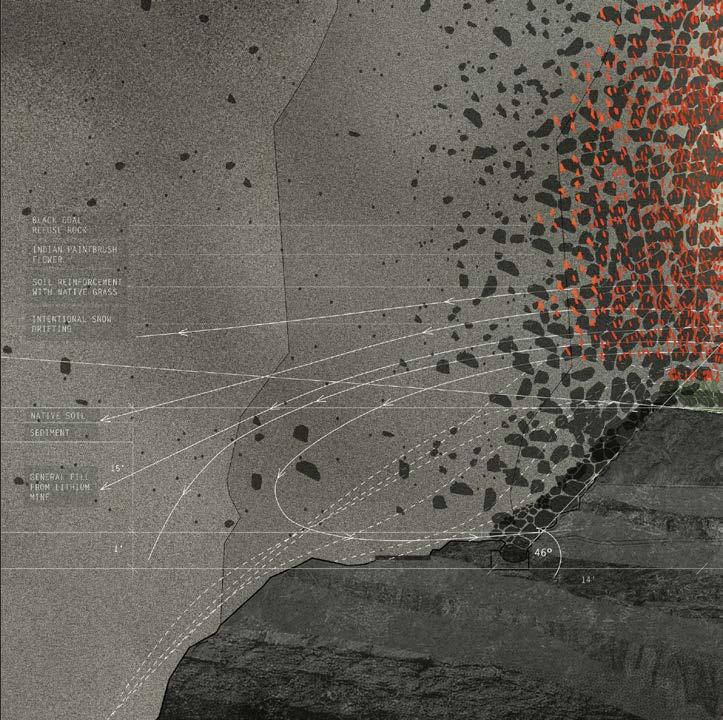

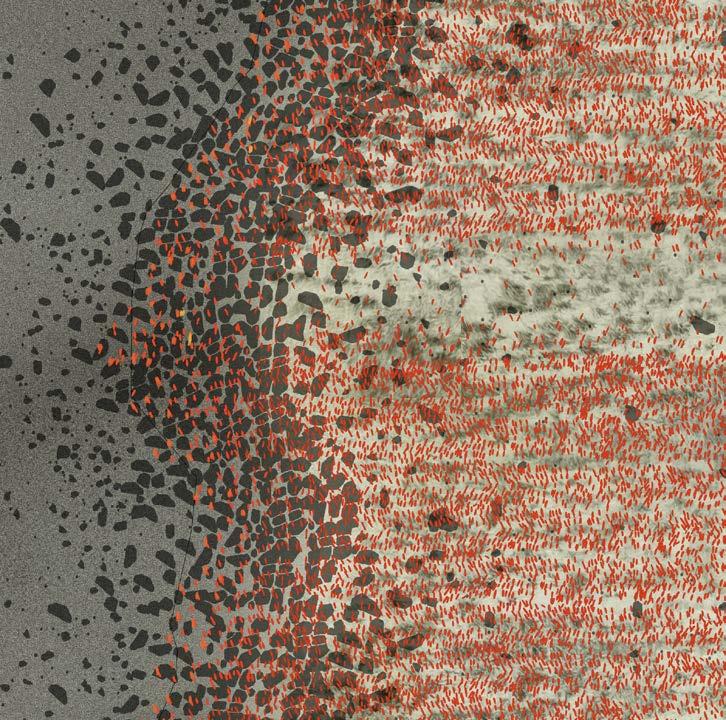

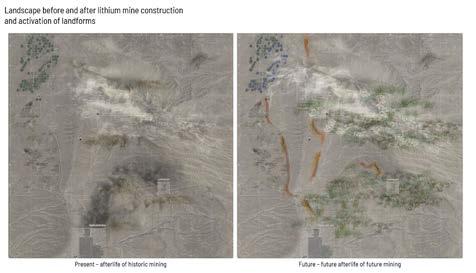

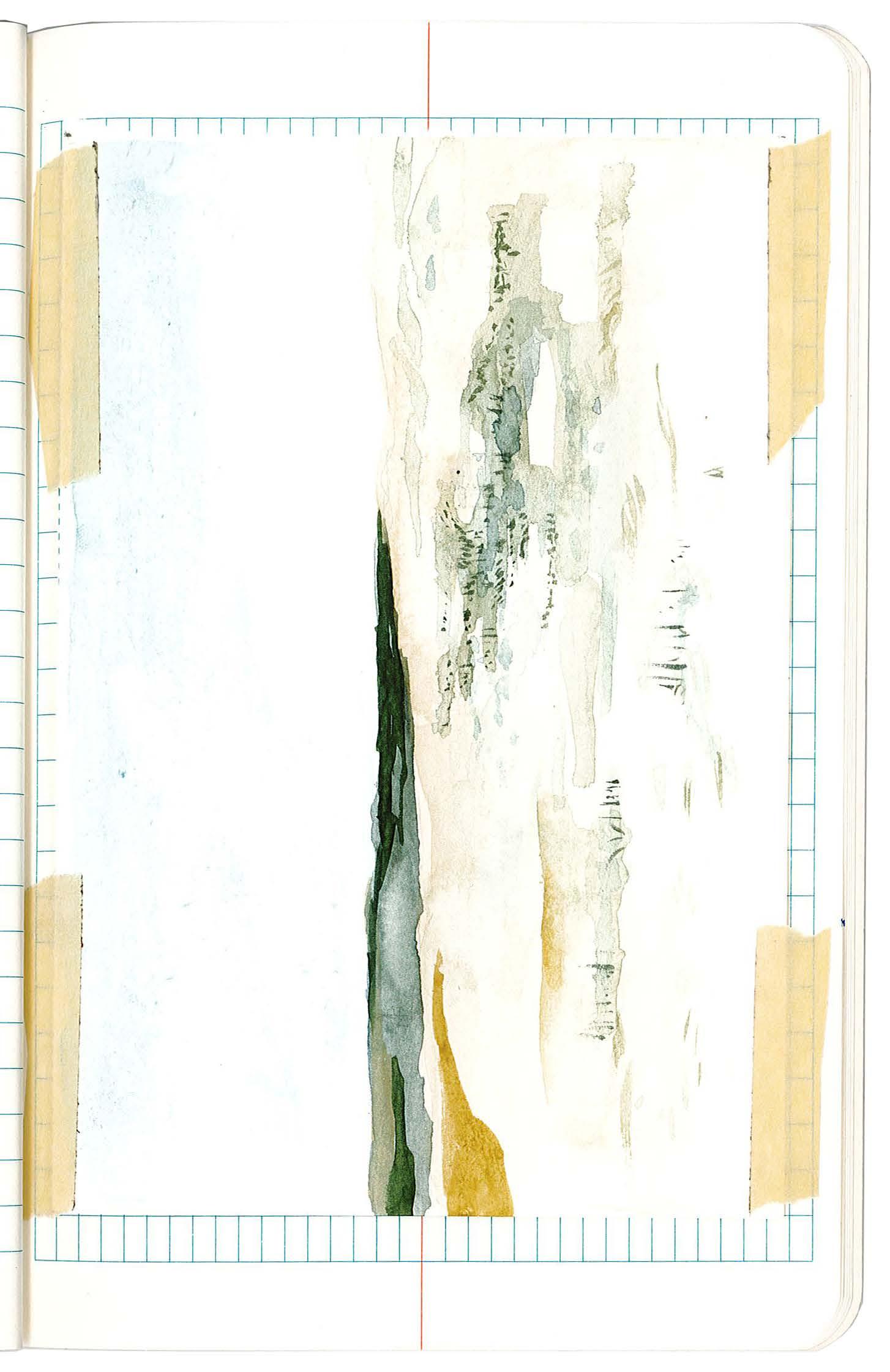

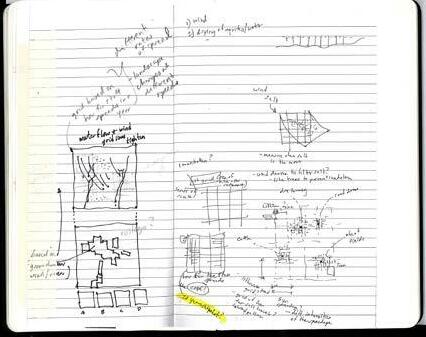

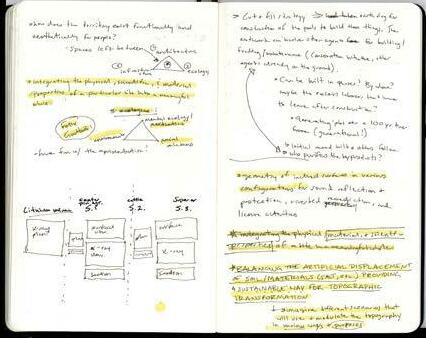

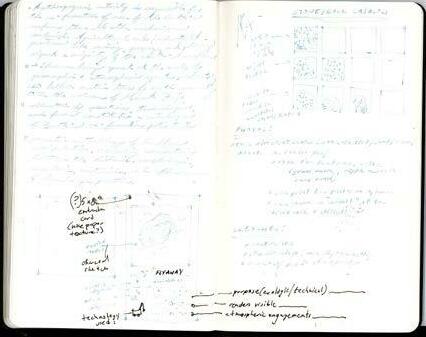

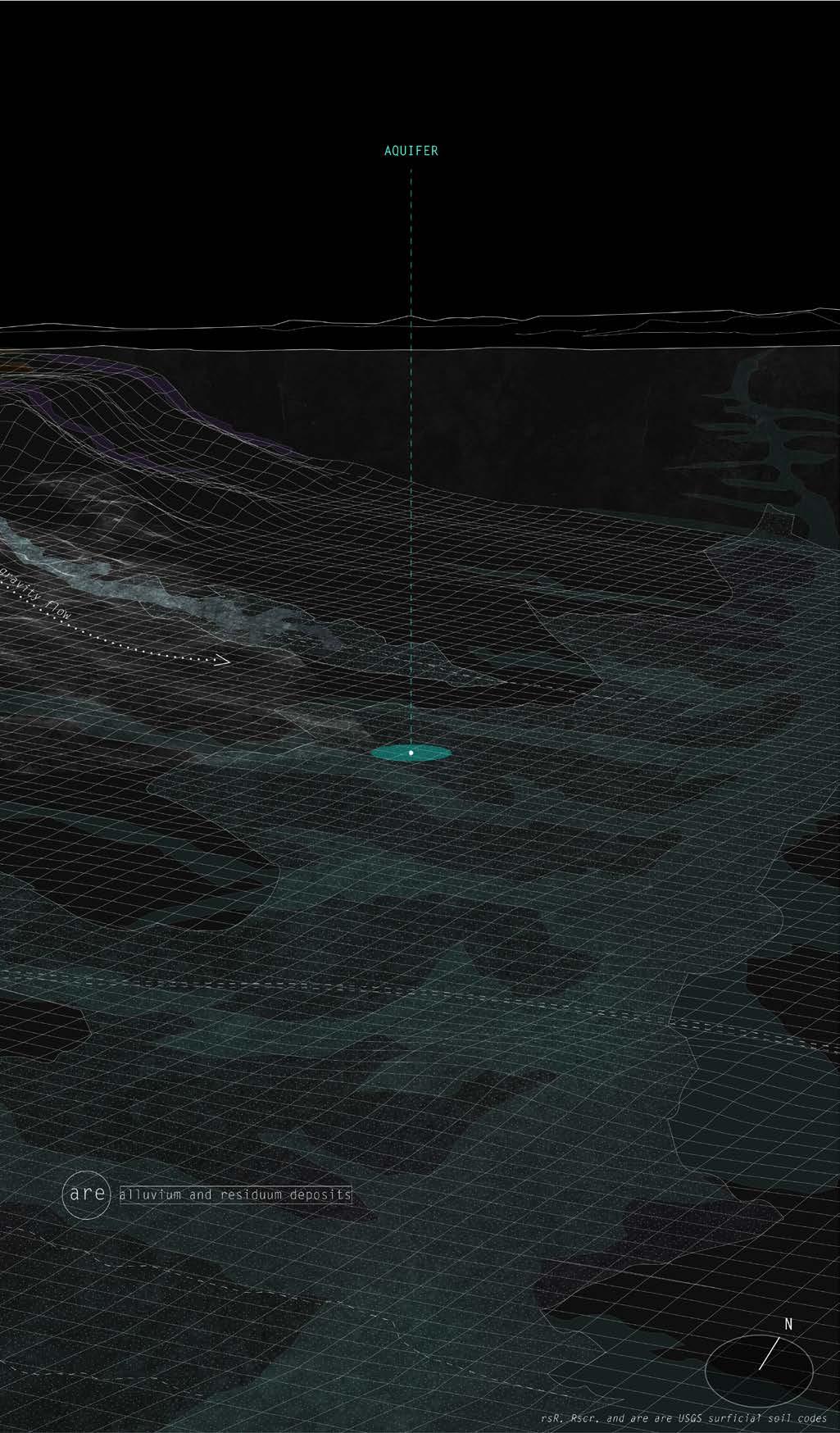

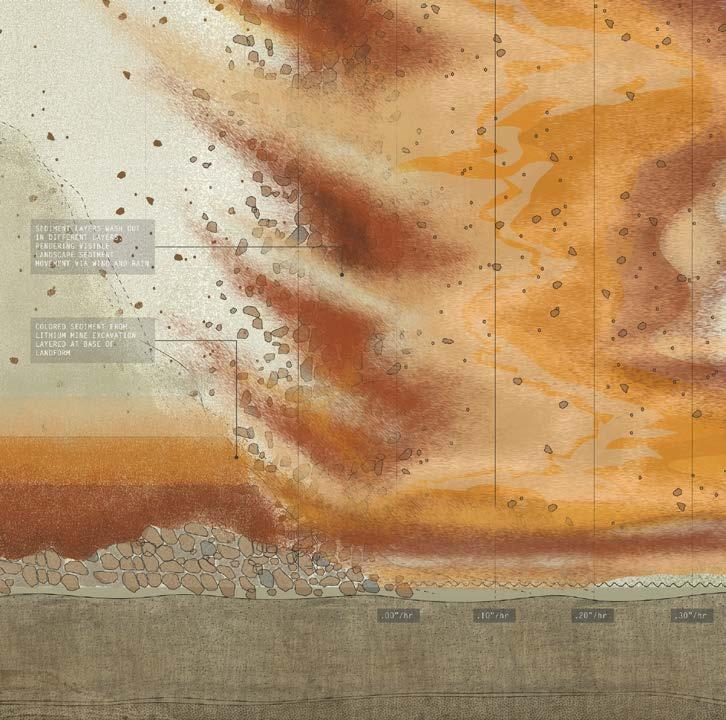

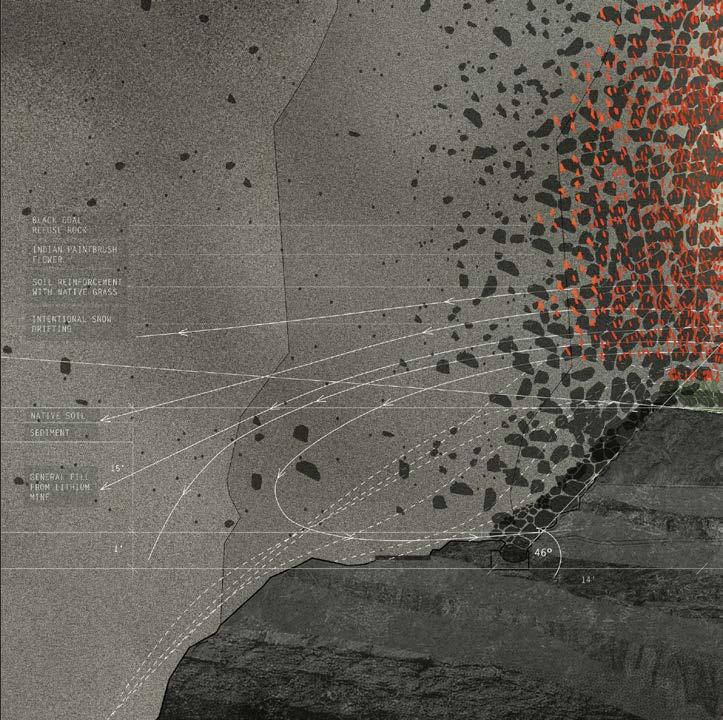

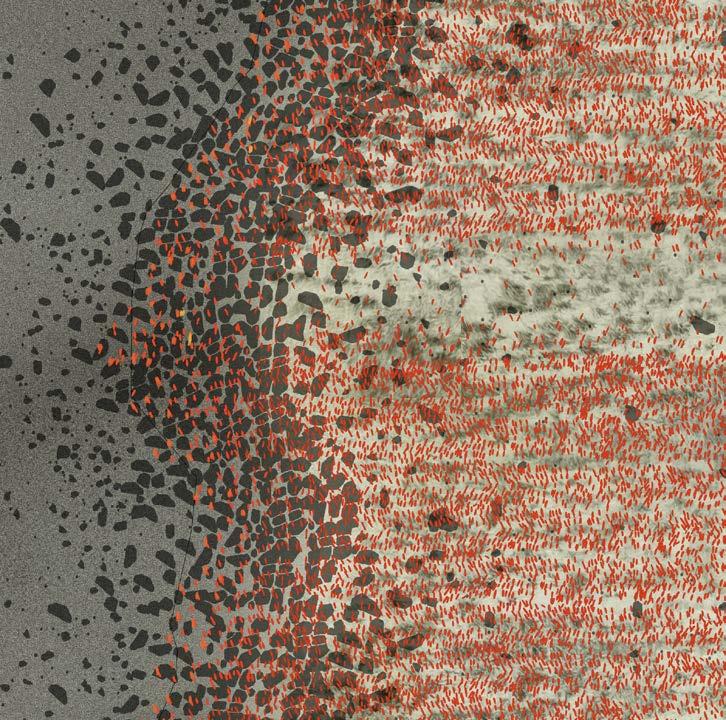

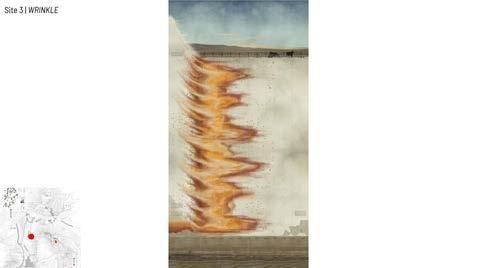

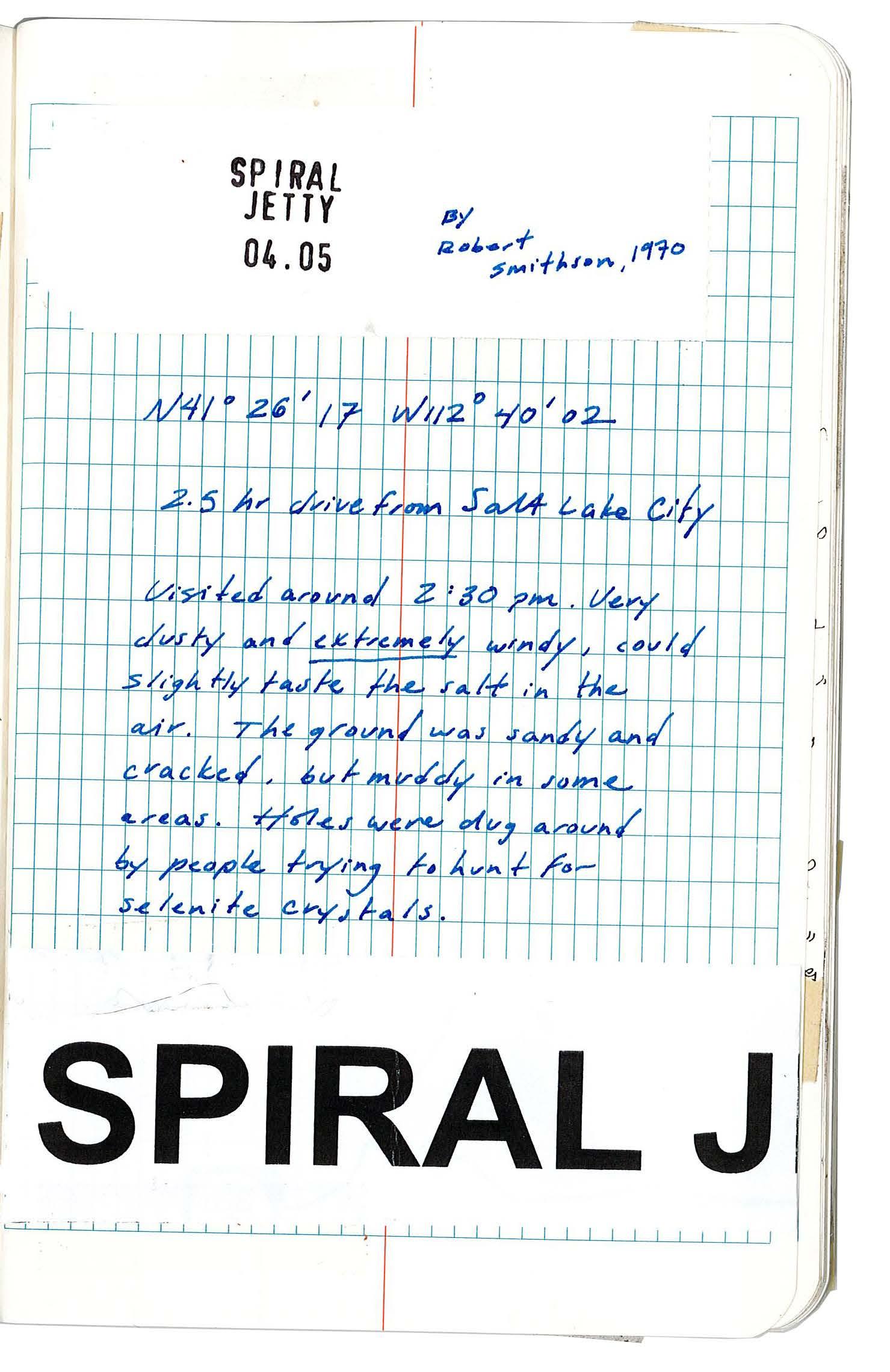

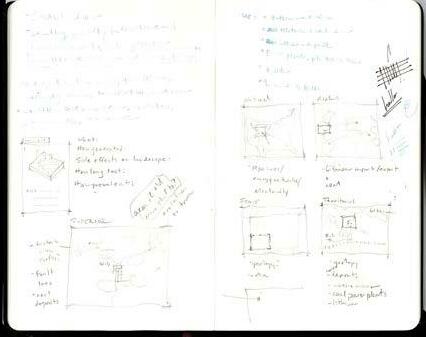

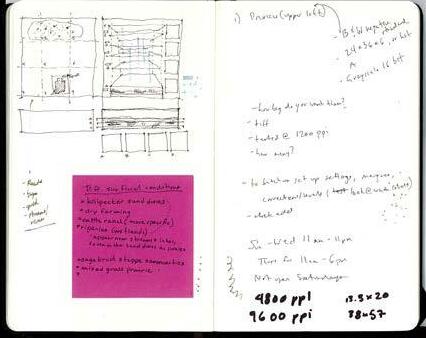

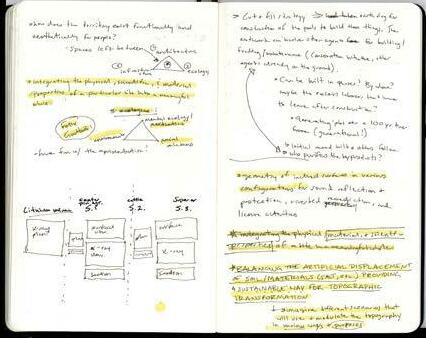

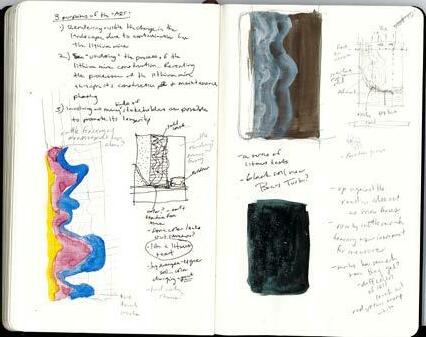

Historically the ground was hollowed for coal mines, excavated for lithium mine ponds, and drilled for oil and gas. The geometry of the earth surficially and sectionally is an expression of how it has been molded by natural, economic, and cultural forces over time. The thesis redefines this into visibility and productivity as a new form of infrastructure. In contrast with typical extractive practices, the landforms follow a cut and fill strategy, where the balancing of the artificial displacement of soil provides a sustainable whole.

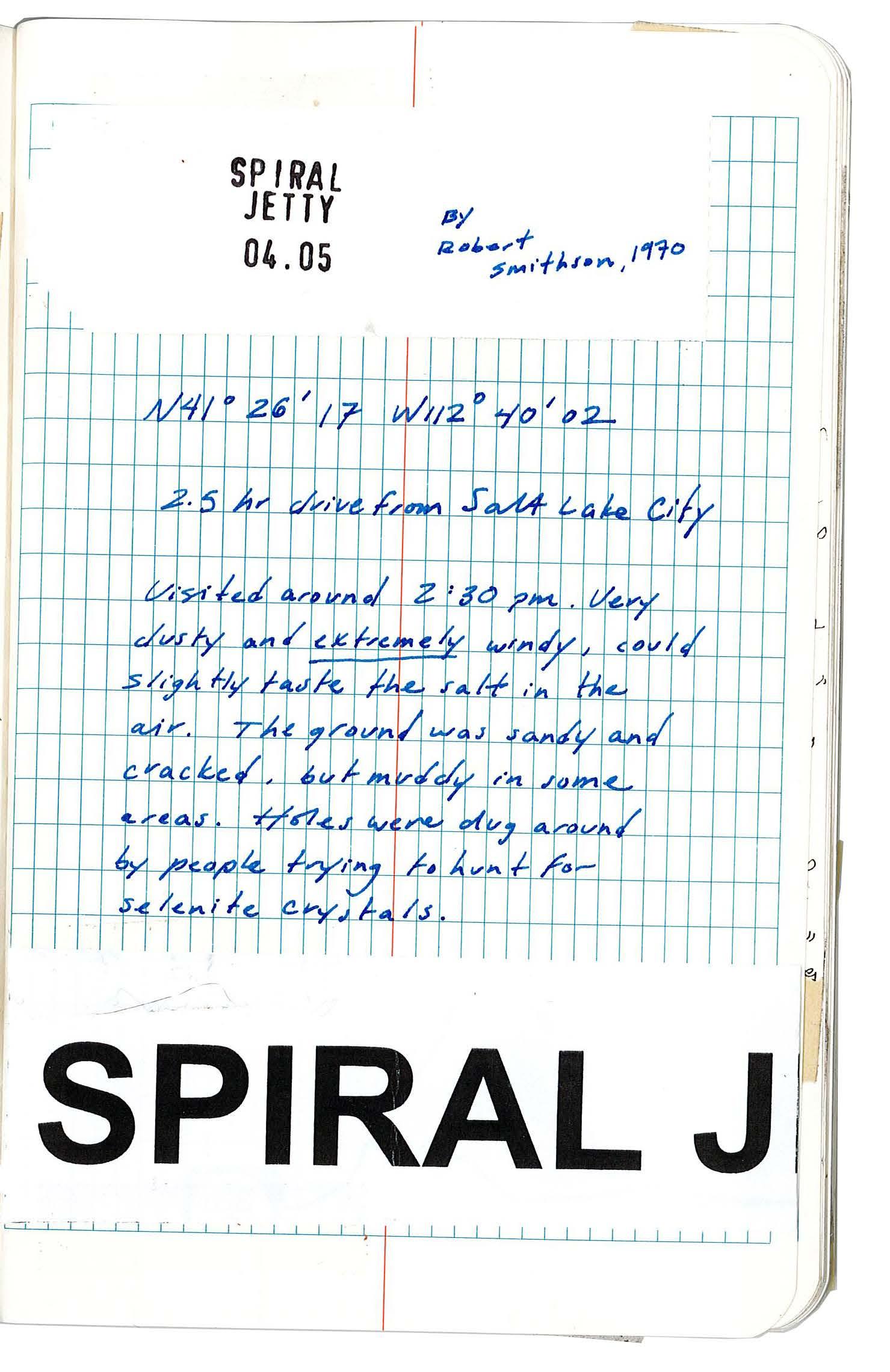

Existing in the voids left between architecture, infrastructure, and ecology, the thesis integrates the memory, physicality, material properties, and environmental processes of a particular site into a meaningful whole. Felix Guattari’s three ecologies: 1) mental ecology (aesthetics), 2) the environment, and 3) social relations, were a guiding principle in this pursuit. The landforms exist within the traditions of land art that began in the 1960s, but also the traditions and memory of the coal mining community that have been here since the late 1800s. The sites are superimpositions of natural, agricultural, and extractive networks changing over time.

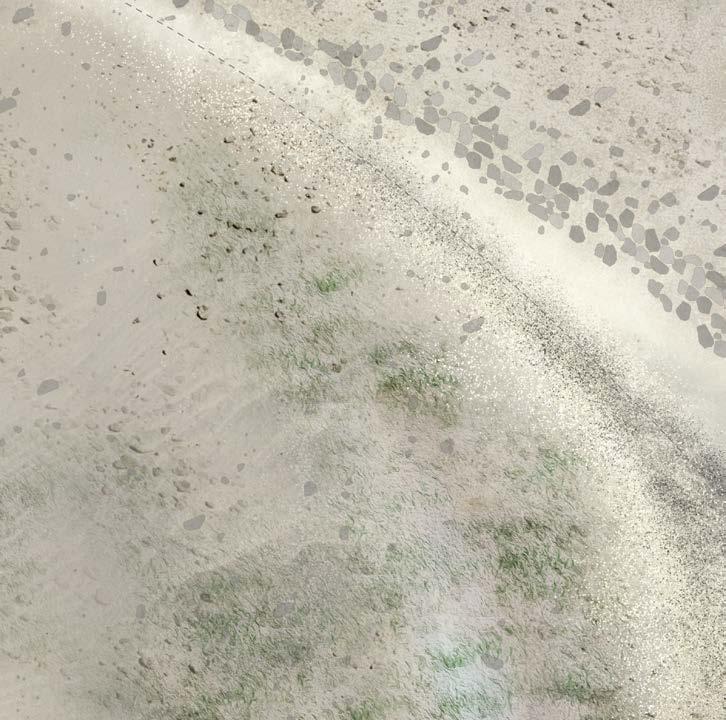

The landforms are not a static solution to the problem of landscape contamination, they are microlandscapes and climates of memory. While in plan the landforms render visible change in the landscape for stakeholders and landscape stewards, the section is ecologically remediative and affects the microclimate. While remediating past landscape exploitation, either by overtilling or unsealed abandoned drilling sites, the landforms also preemptively remediate possible future lithium mine effects.A generative methodology of landform manipulation reveals correlations between histories, morphologies, assemblies, materials, and affordances of landscape practice.

123

IX Sites of Stewardship

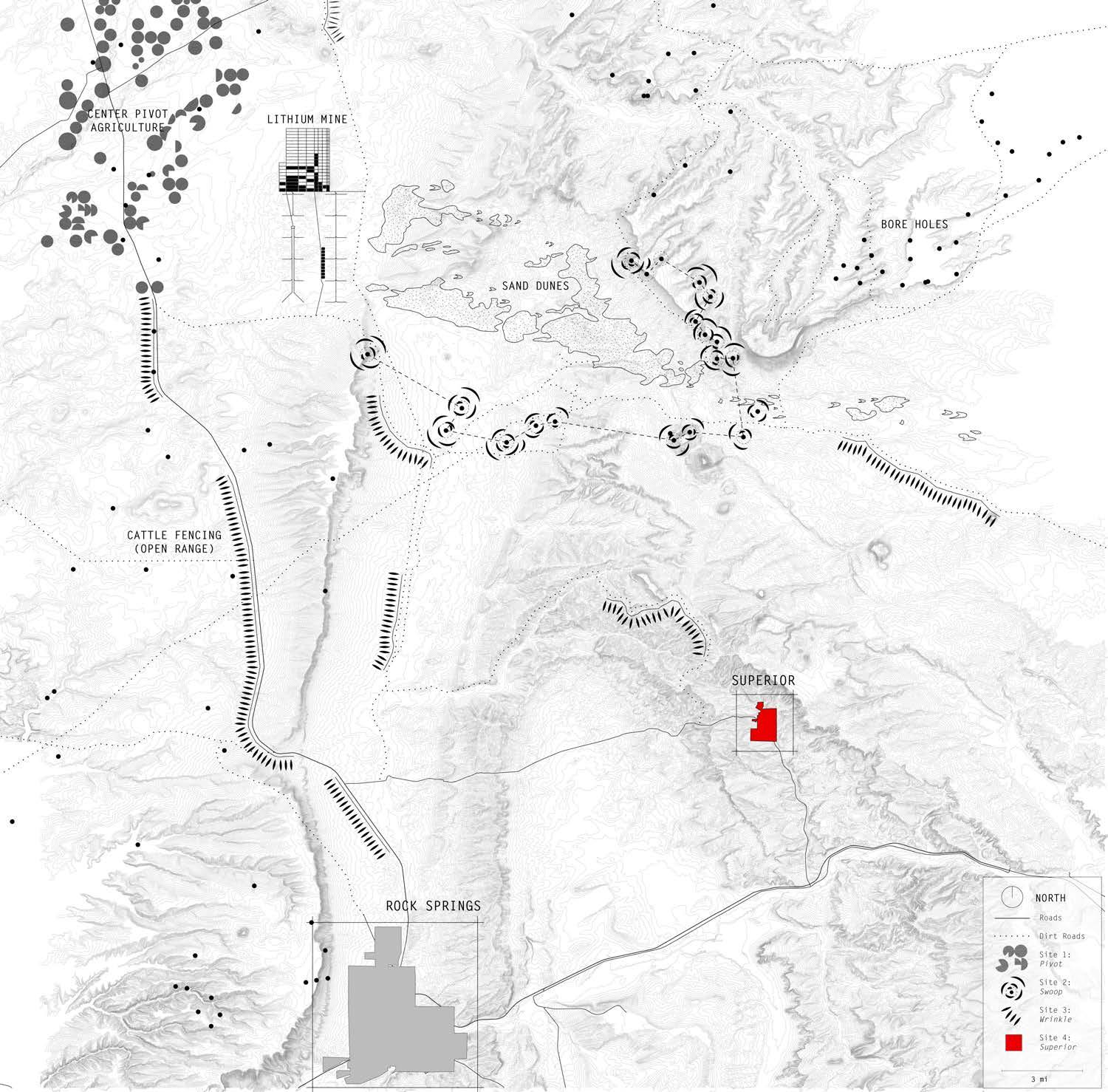

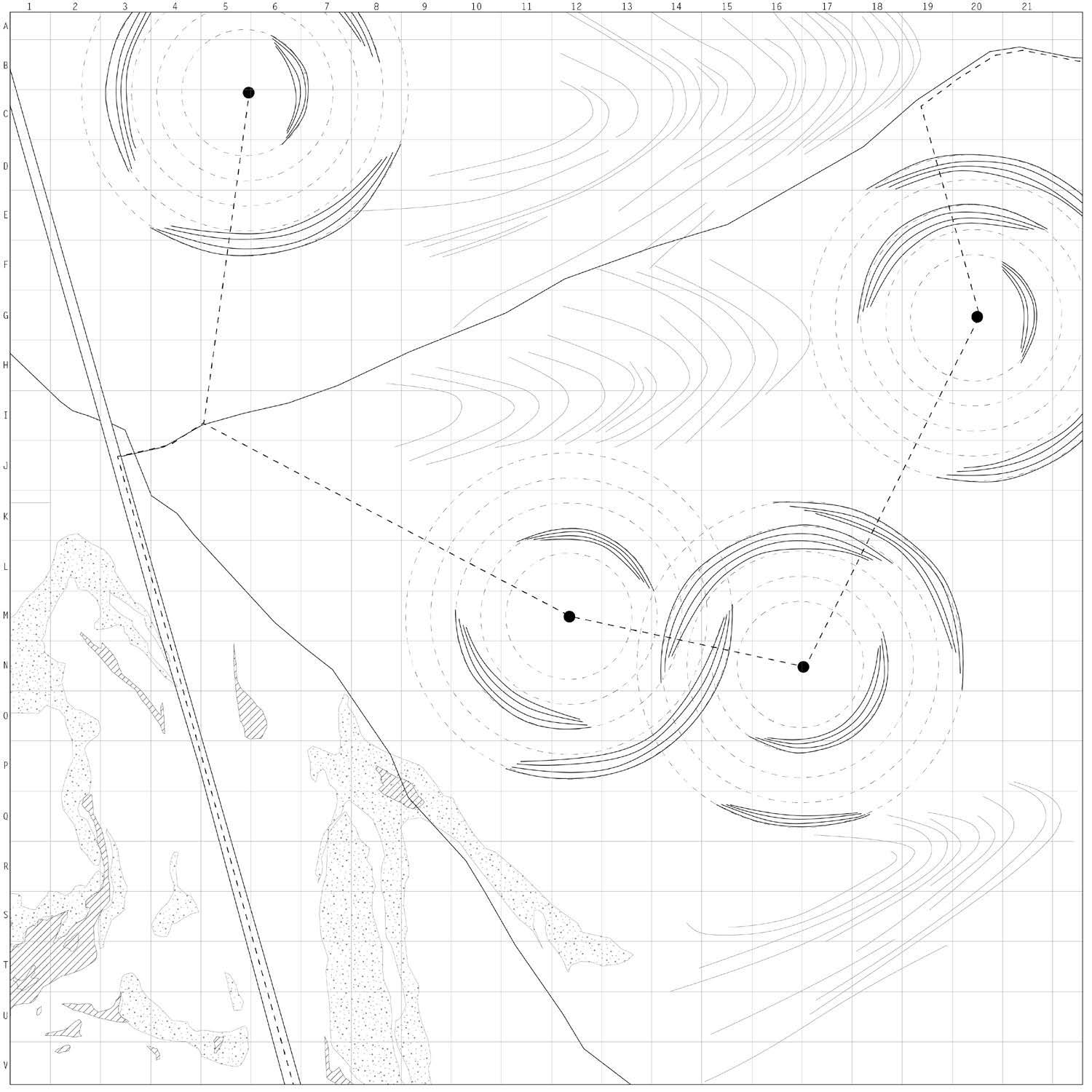

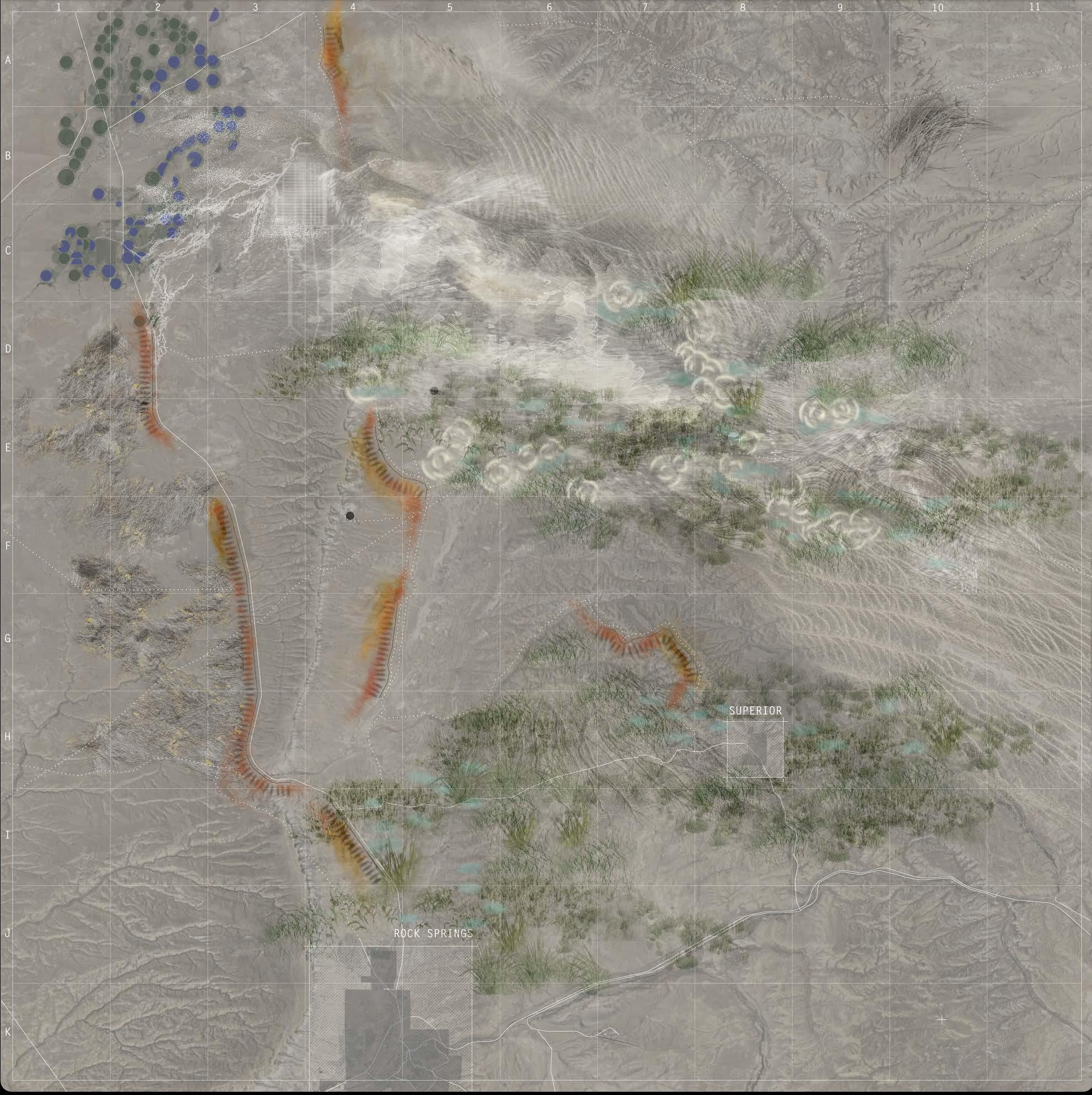

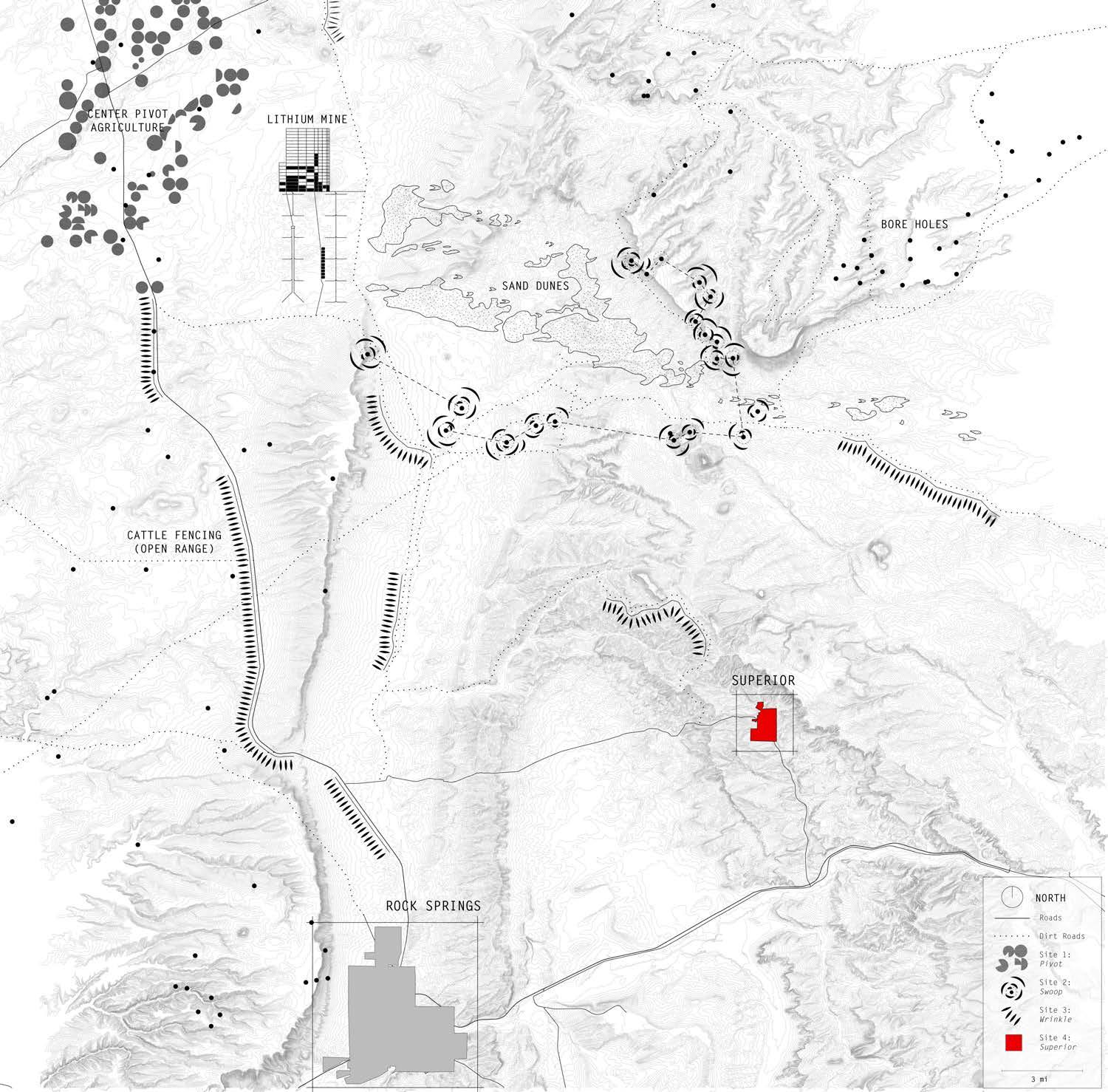

124 +0 ft 3 mi

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

NOTATIONAL KEY MAP OF THE DESIGNED LANDFORM FIELD IN SWEETWATER COUNTY

125 IX Sites of Stewardship

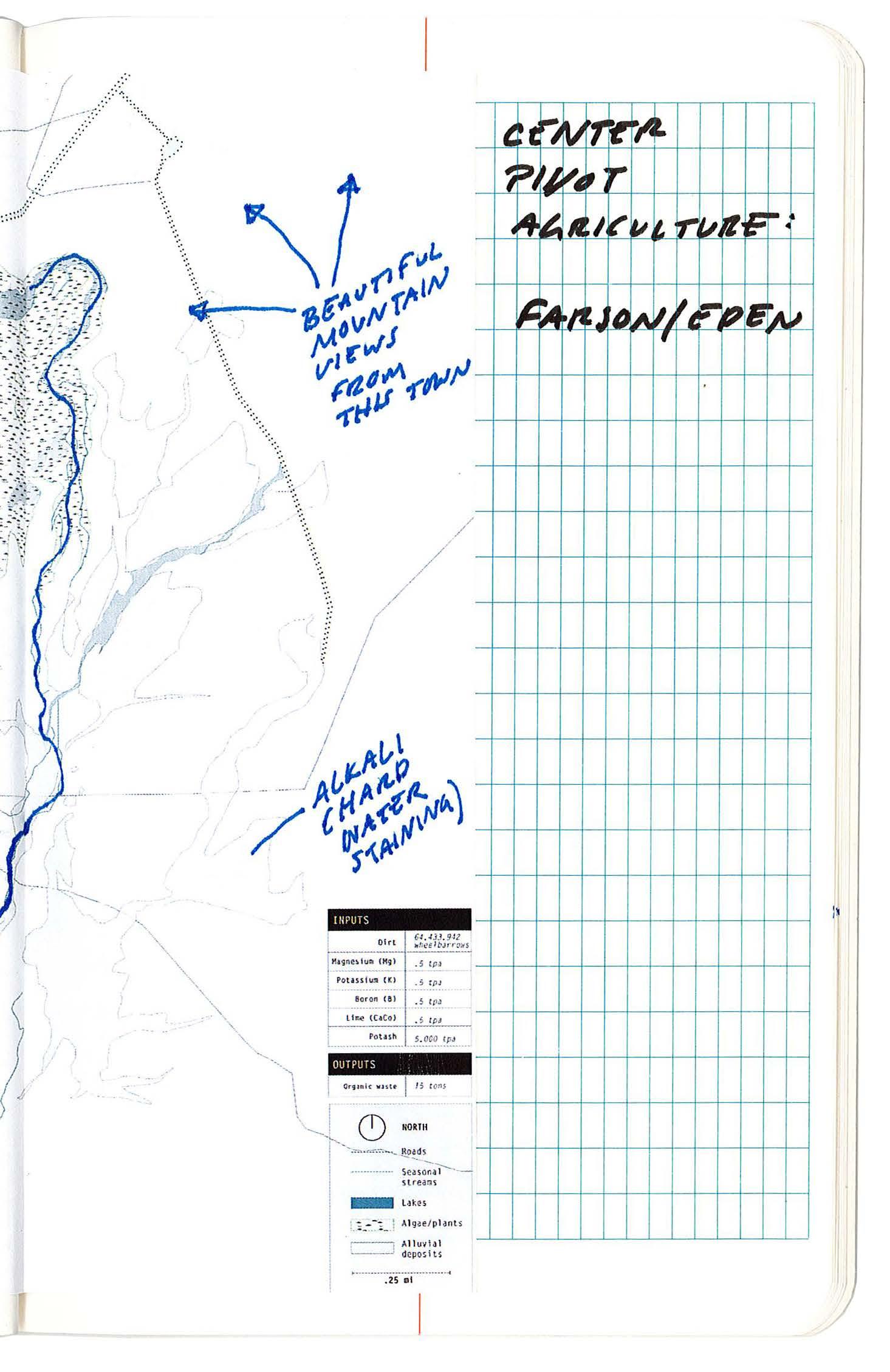

126 IX-a

Center Pivot Agriculture Turned Firefly Halos

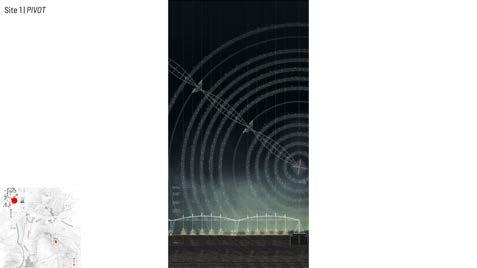

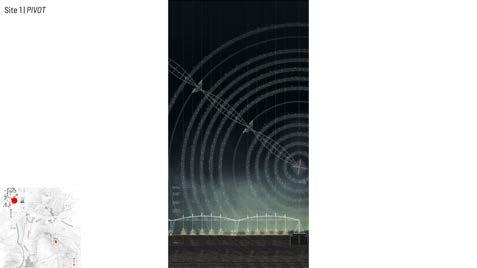

127 IX-a Sites of Stewardship | PIVOT

SITE

PIVOT

1:

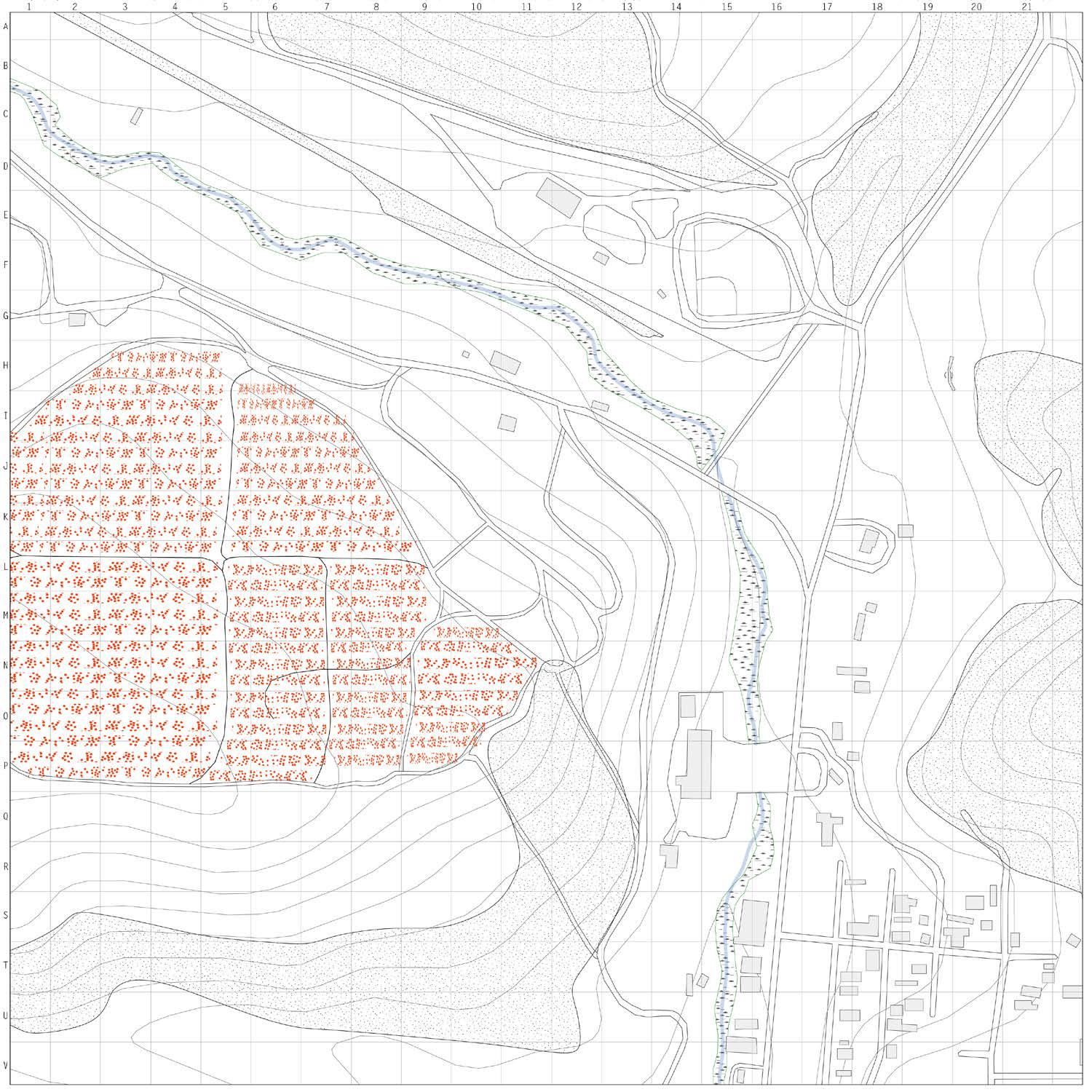

128 +0 ft .25 mi

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

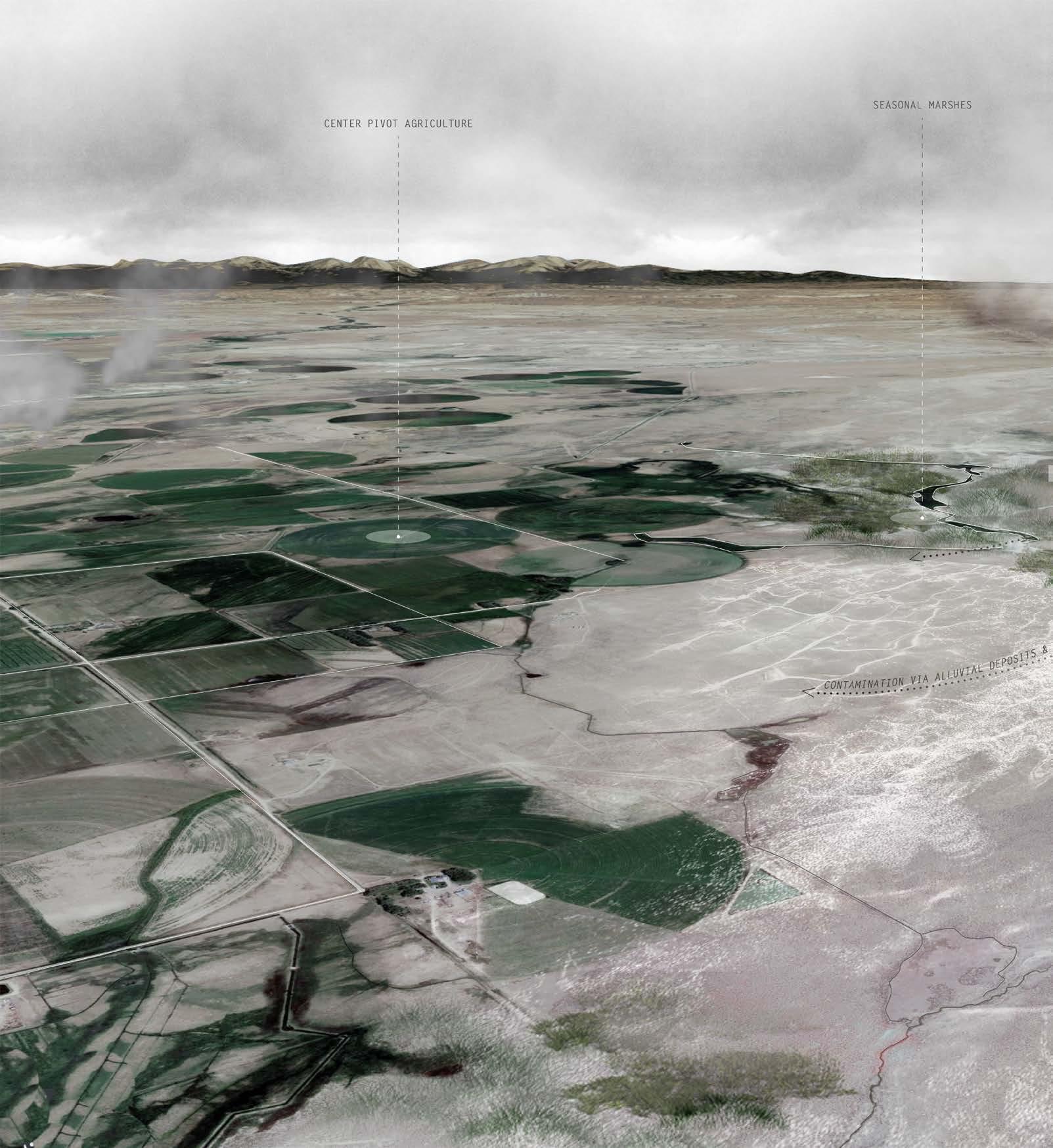

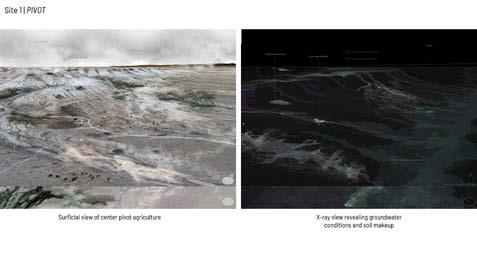

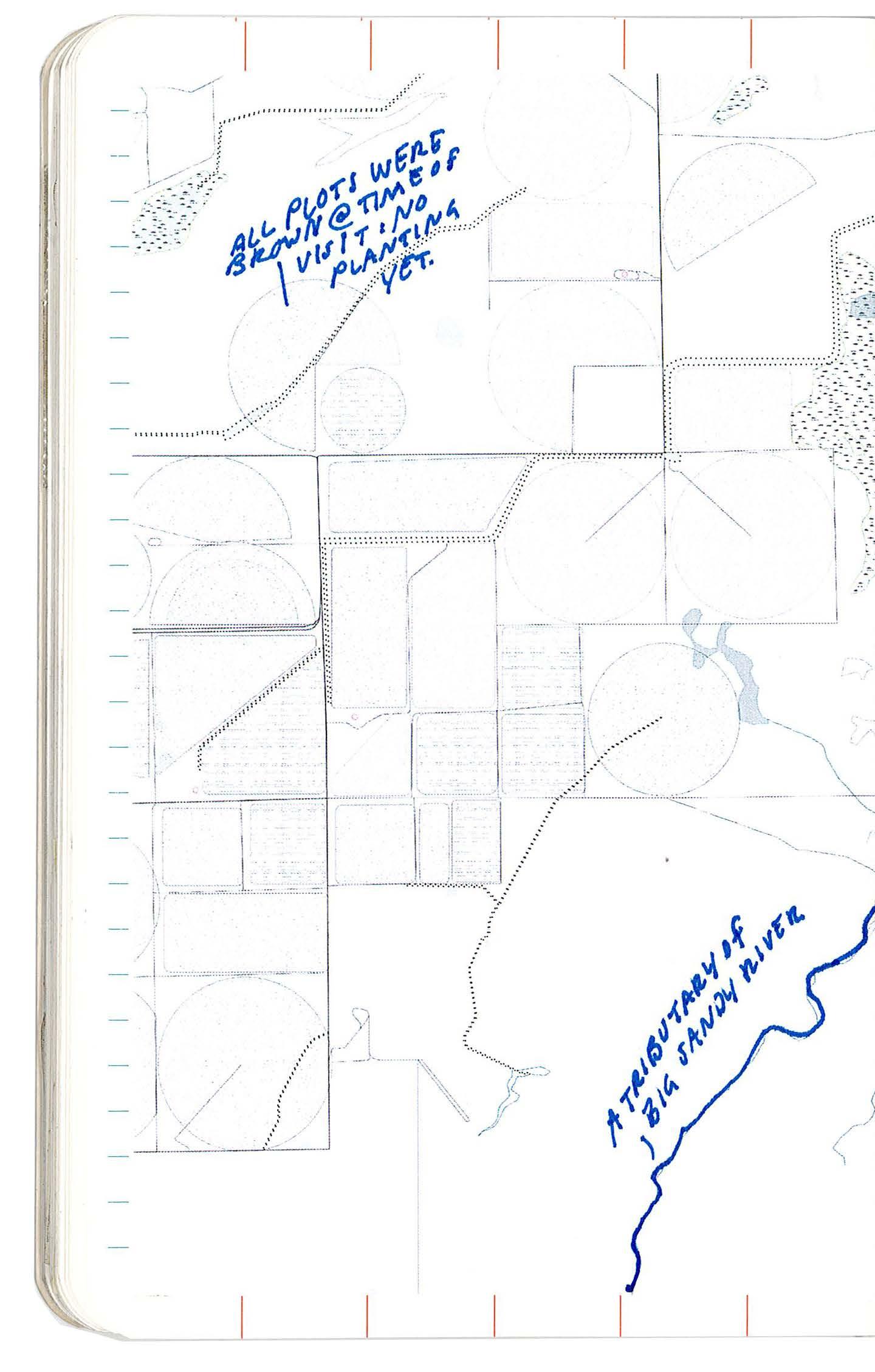

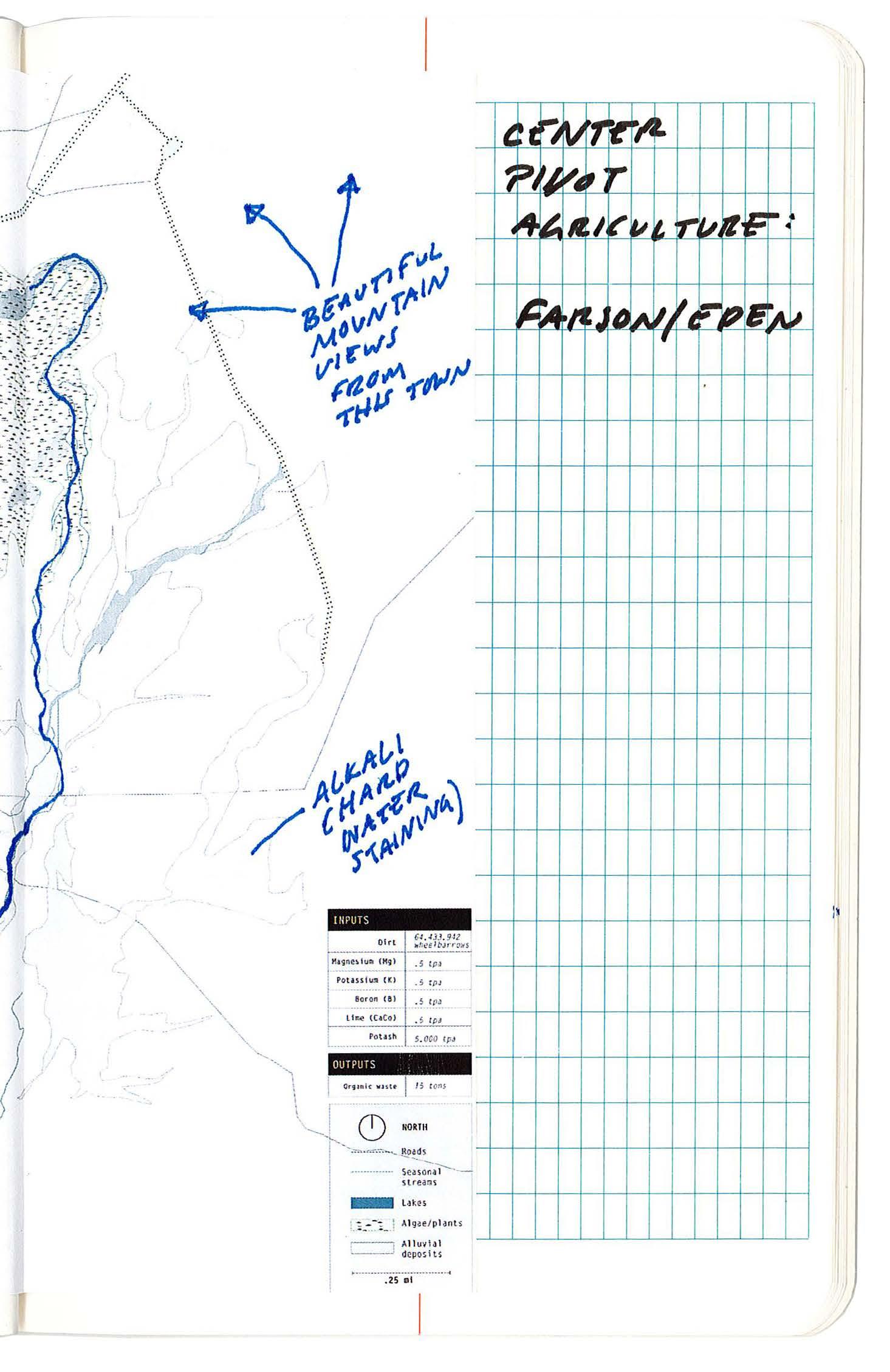

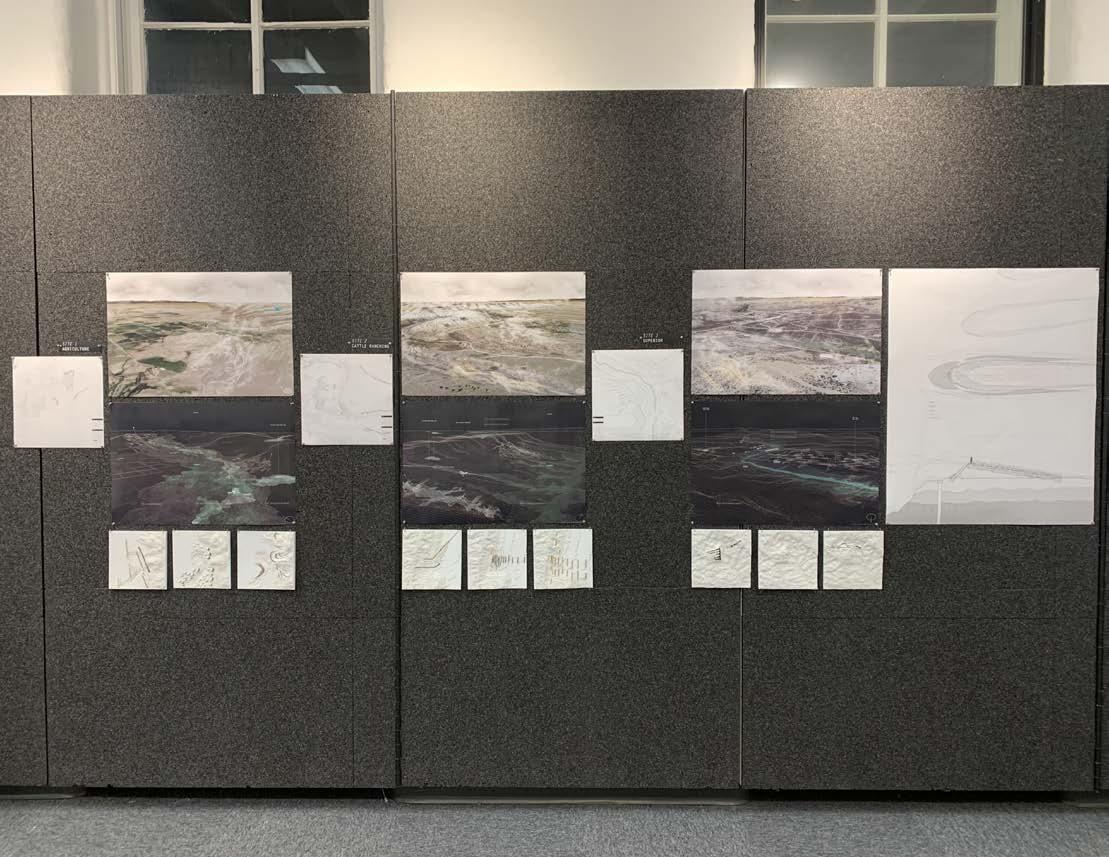

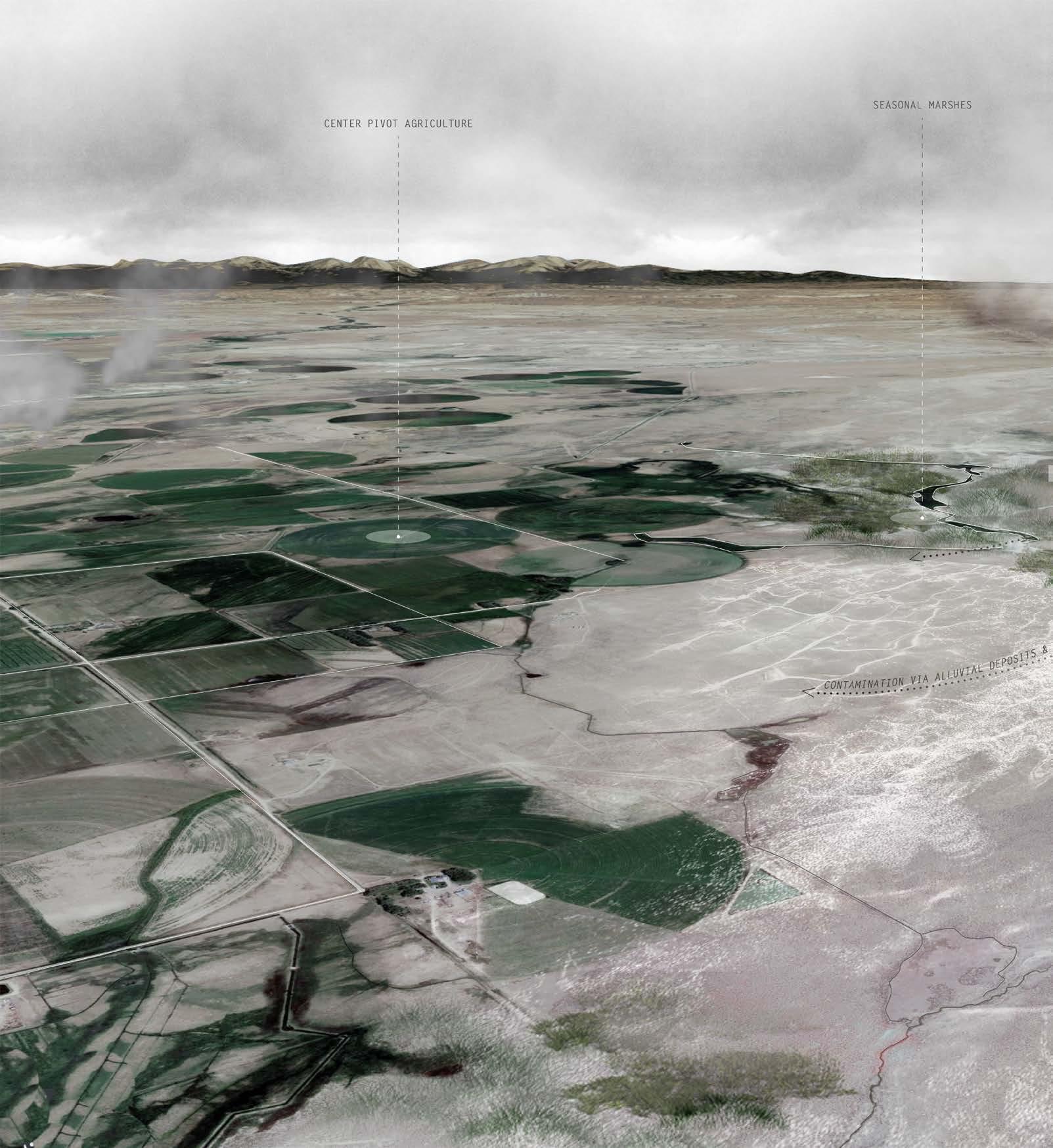

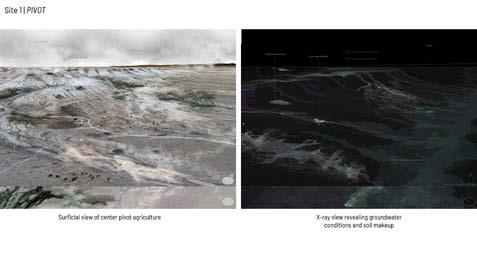

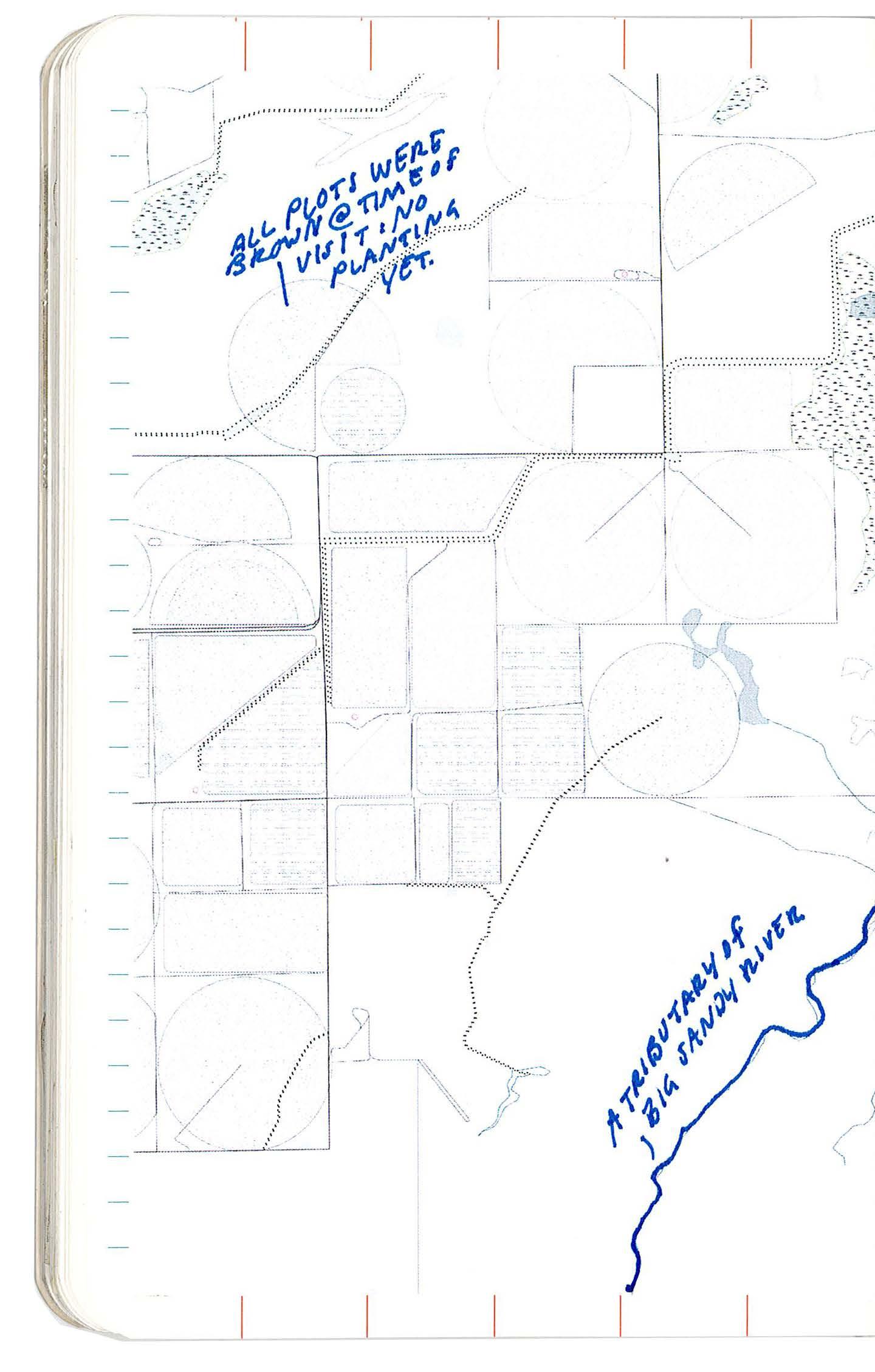

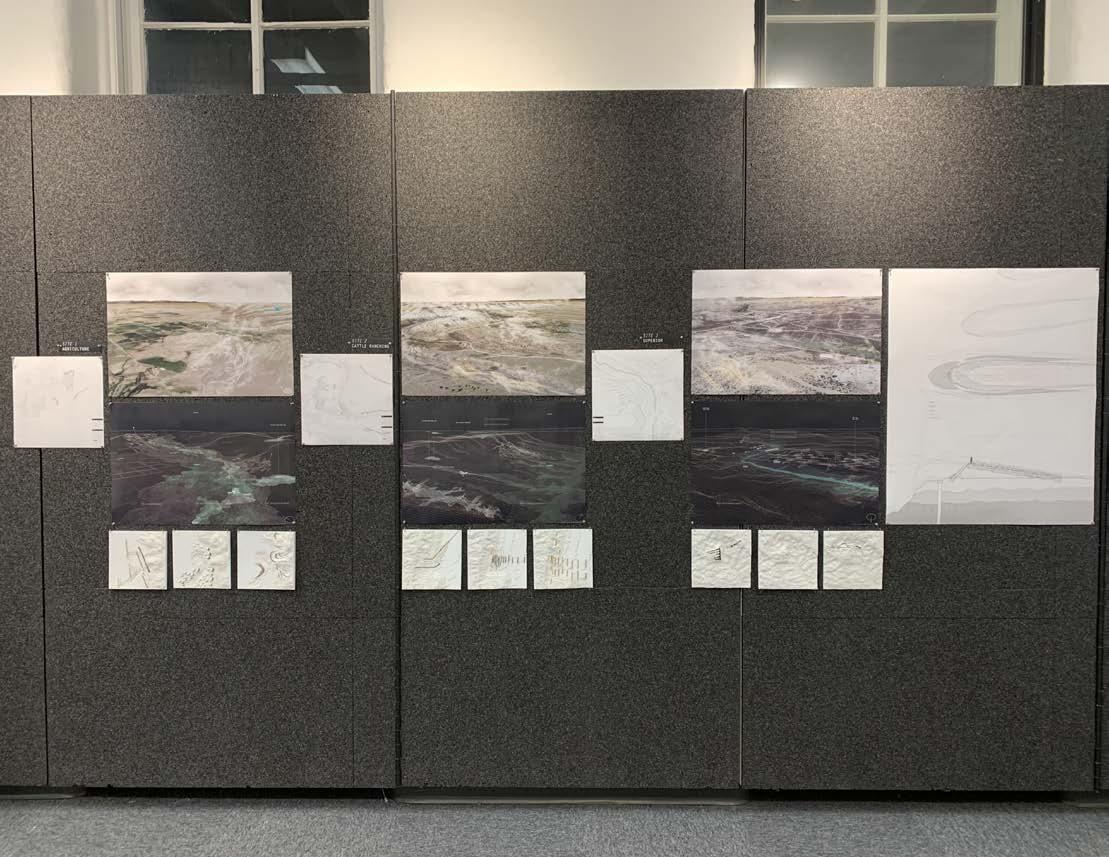

SITE 1: PIVOT | CENTER PIVOT AGRICULTURE

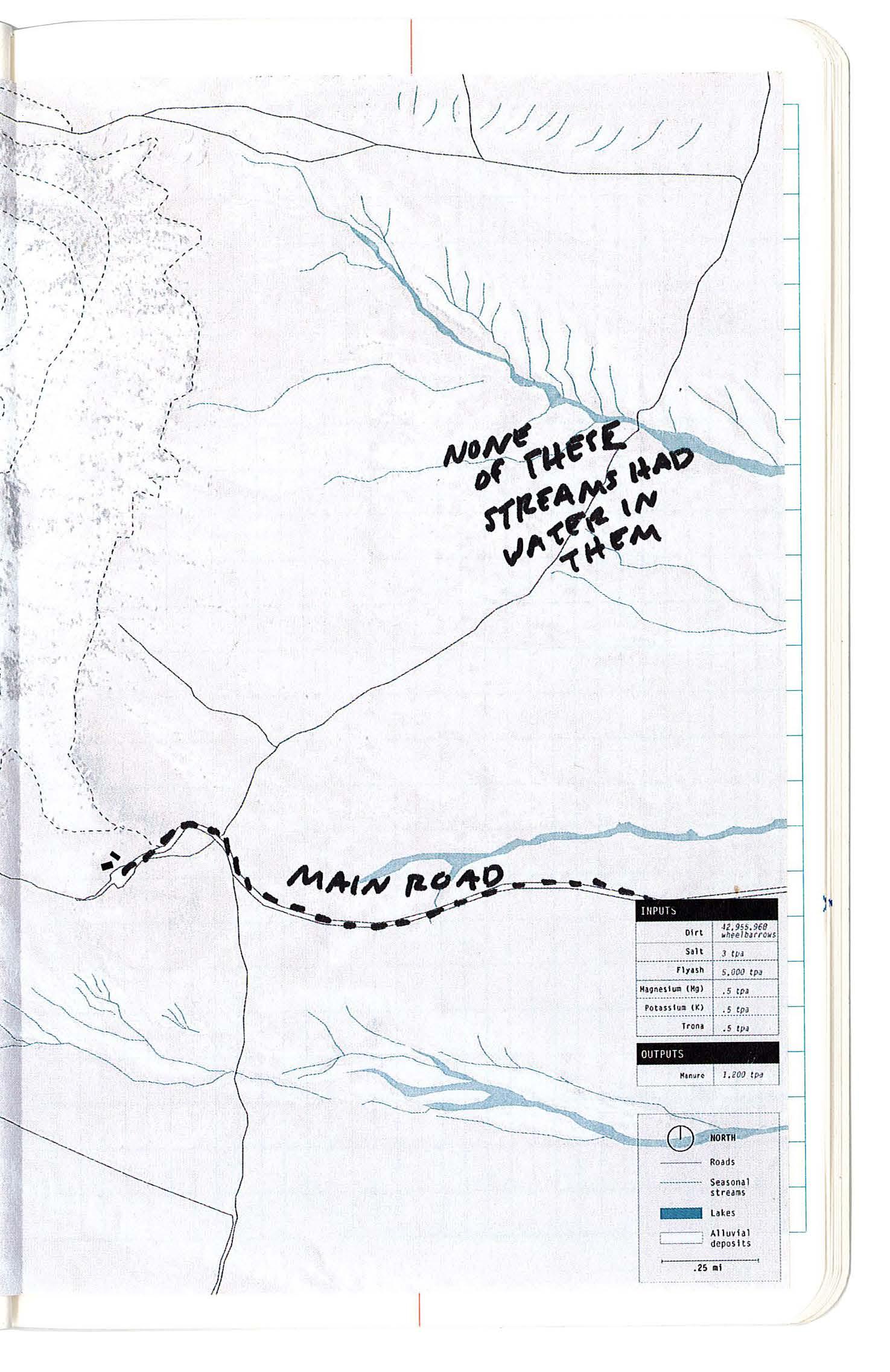

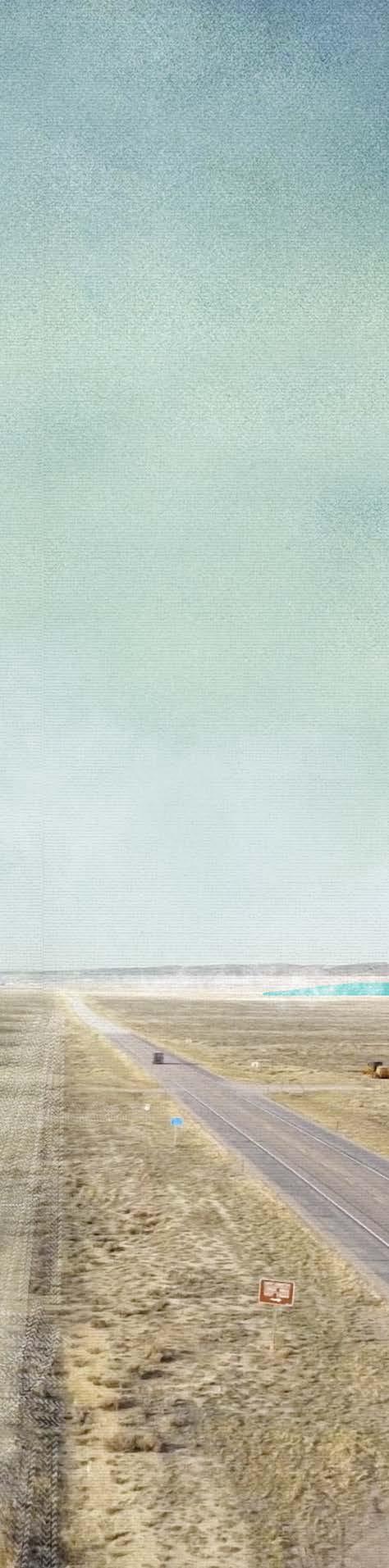

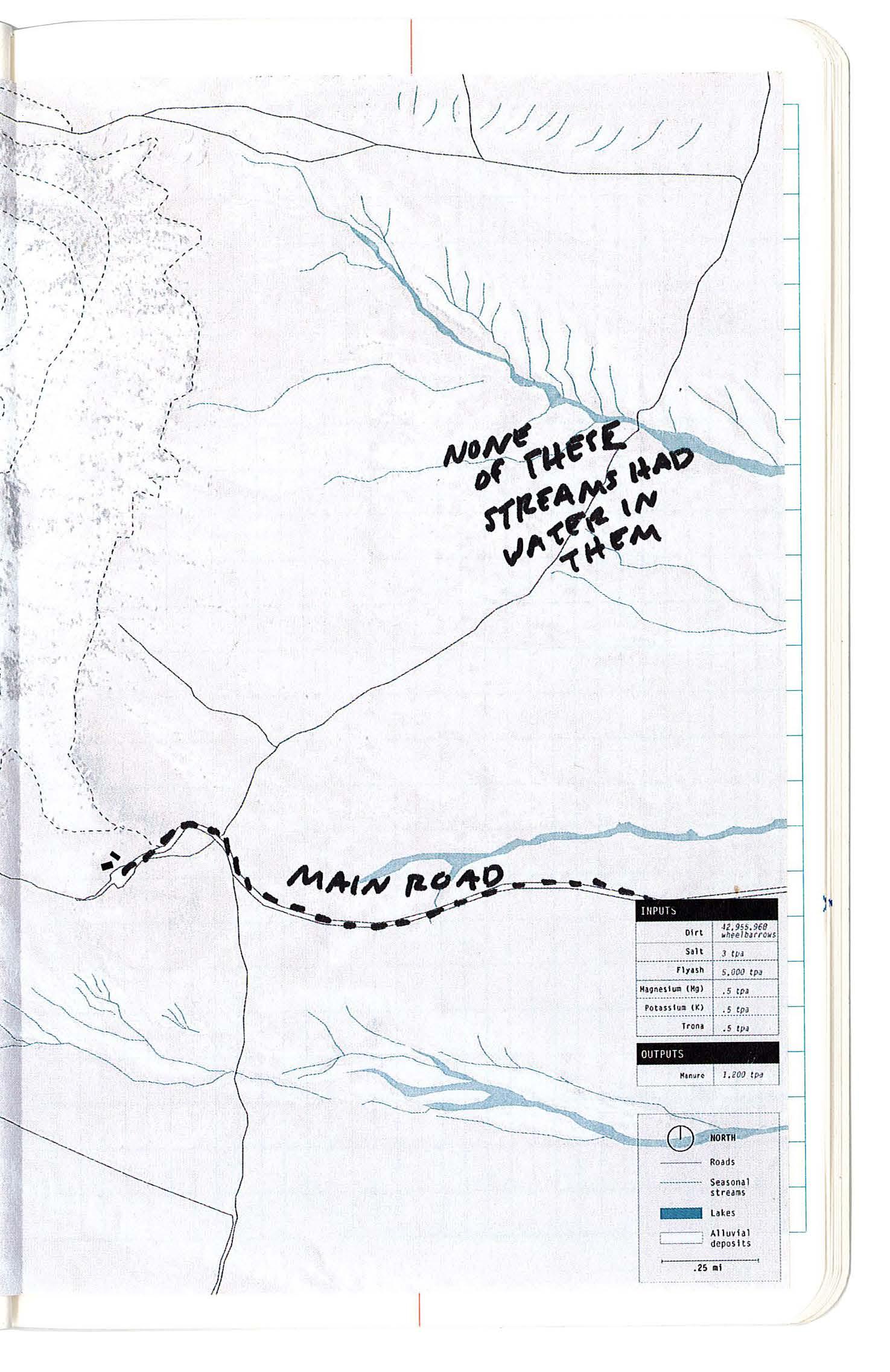

Land practices on Site 1 consist mainly of center pivot agriculture and row crops. A seasonal river in the “Eden Valley” feeds the farms through a series of canals. Since the parcels are downstream and at a lower topography than the lithium mine site to the west, the site is vulnerable to contamination via groundwater flow and toxic sediment that the river might collect.

Site 1 utilizes Magnesium, Potassium, and Boron as fertilizers for crops and Potash to improve water retention capabilities in soil as an anticipatory measure for future drought conditions exacerbated by the lithium mine.

129 IX-a Sites of Stewardship | PIVOT

130

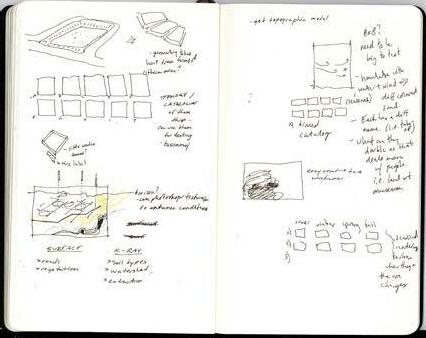

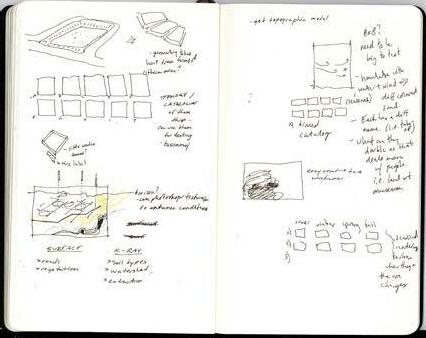

SURFICIAL ANALYSIS OF SITE 1

Surficial analysis of site 1 expresses land practices and possible flows of contaminants through the Eden Valley via seasonal alluvial channels.

131 IX-a Sites of Stewardship | PIVOT

132 Surficial

soil

content information from: United States Geological Survey

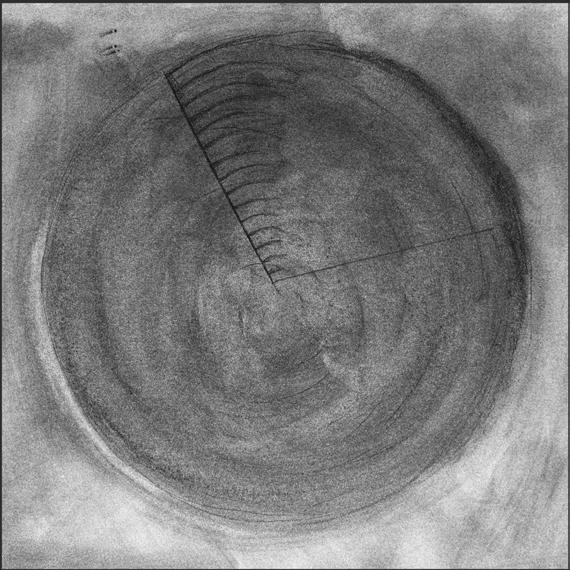

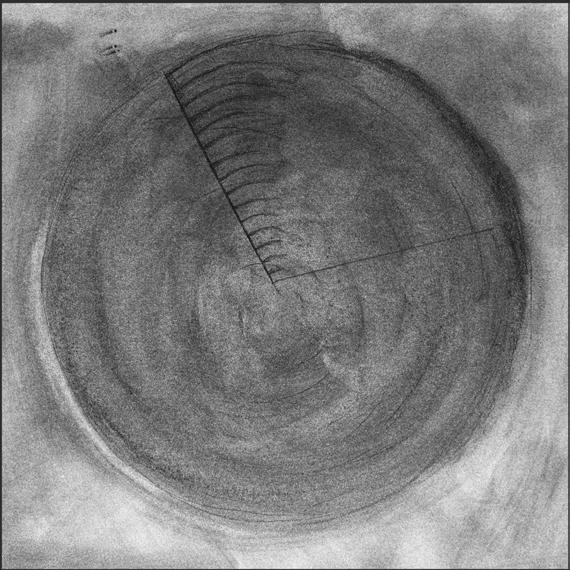

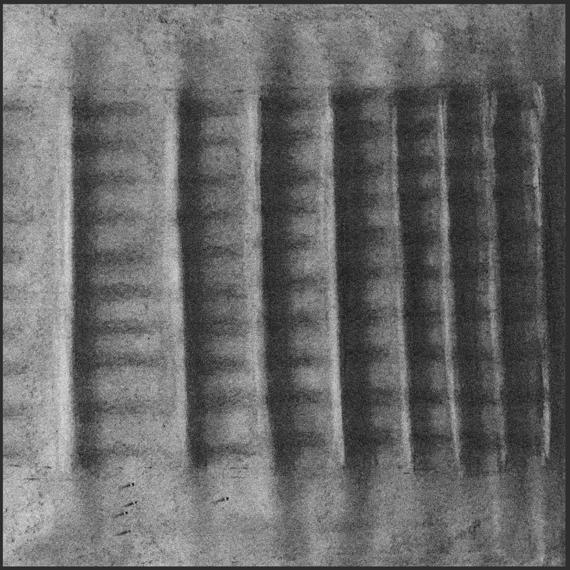

SUB-SURFICIAL X-RAY ANALYSIS OF SITE 1

Sub-surficial x-ray analysis of site 1 uncovers groundwater levels, surficial soil types, topographical conditions, and how contaminants might spread below the surface.

133 IX-a Sites of Stewardship | PIVOT

134

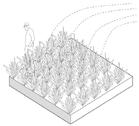

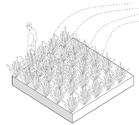

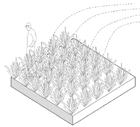

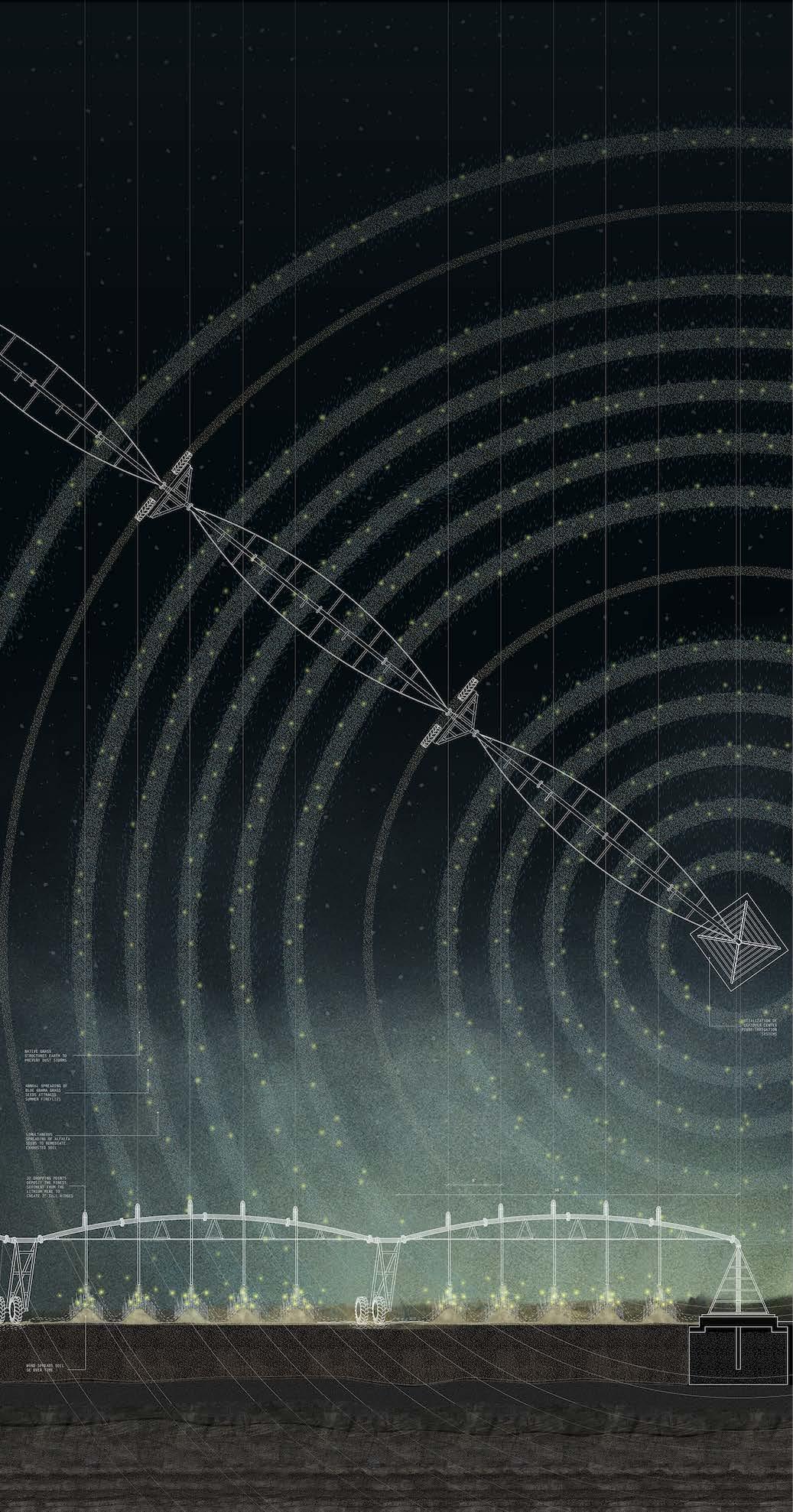

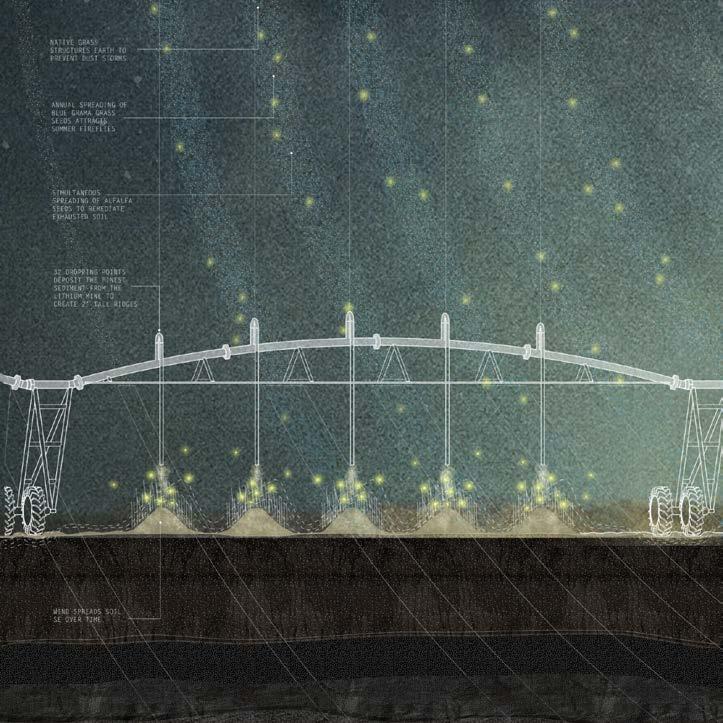

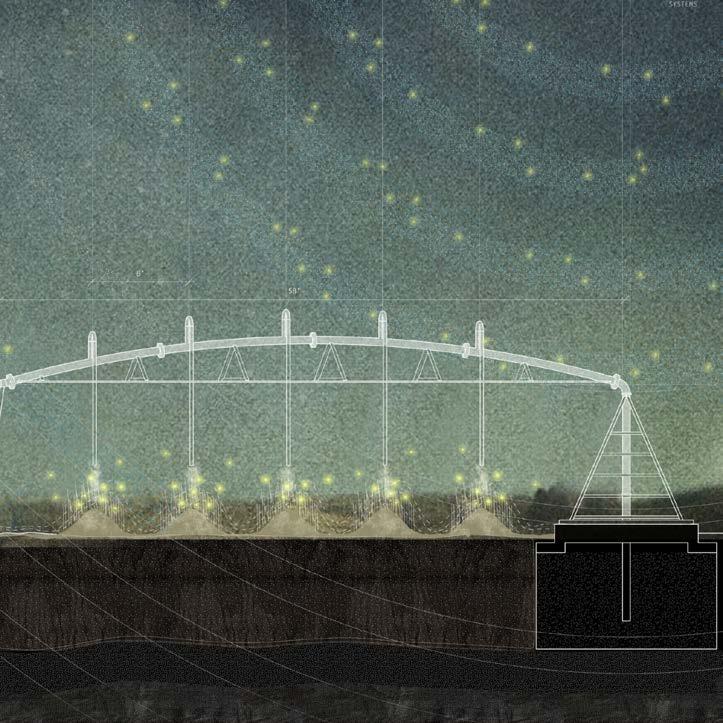

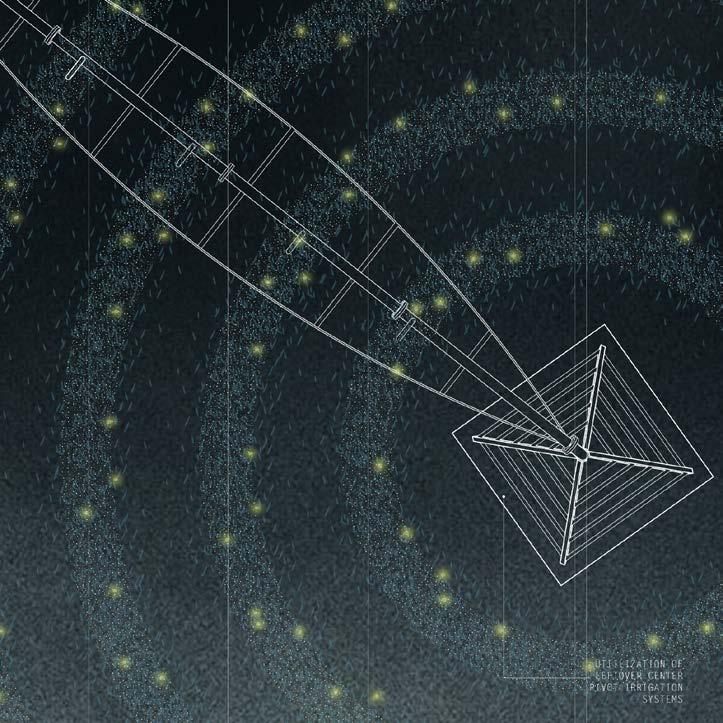

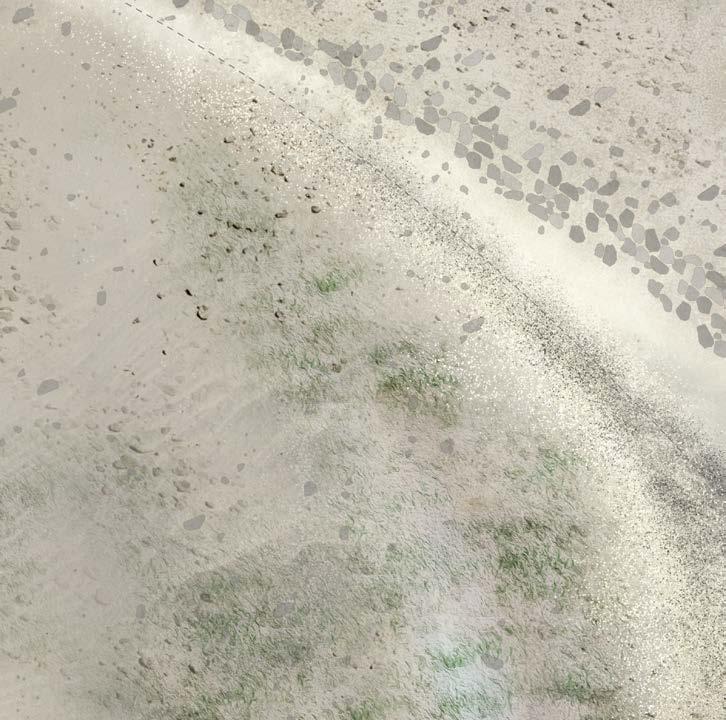

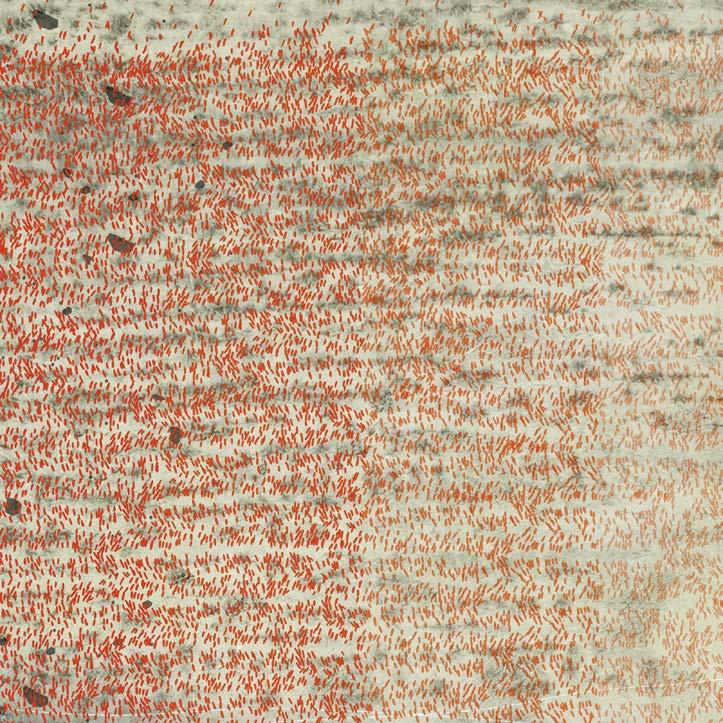

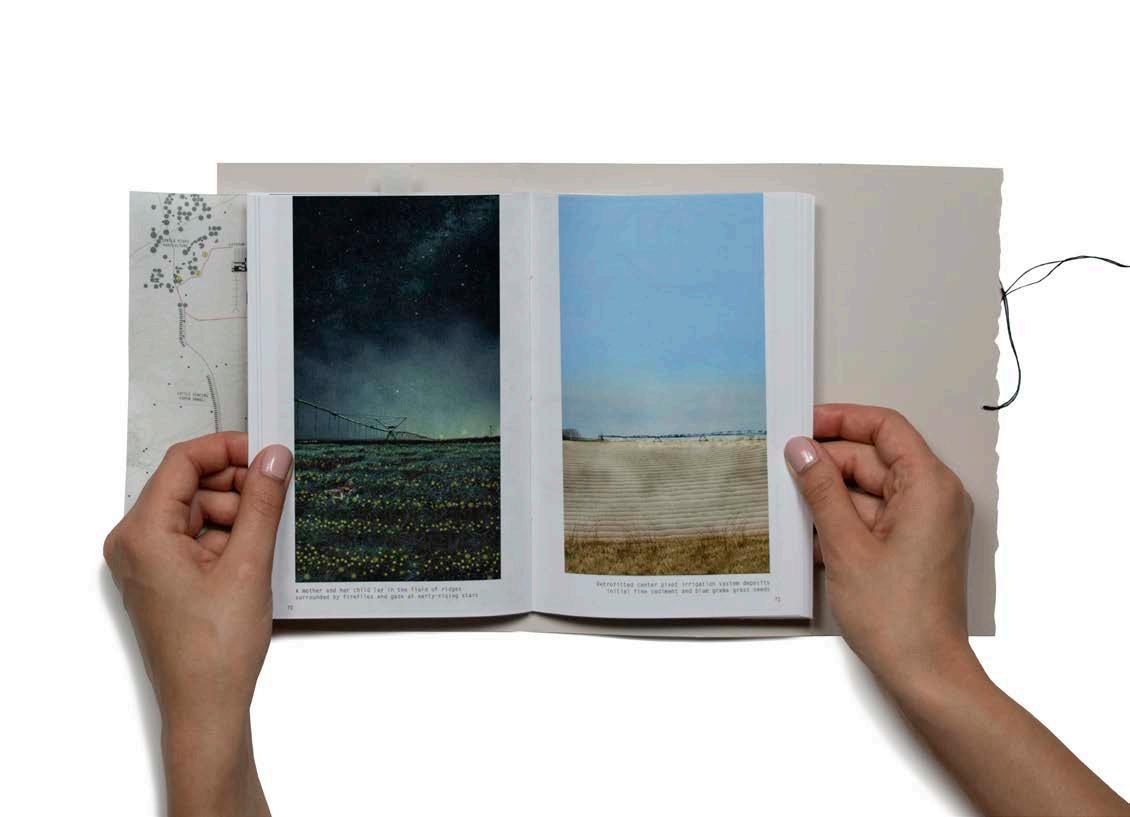

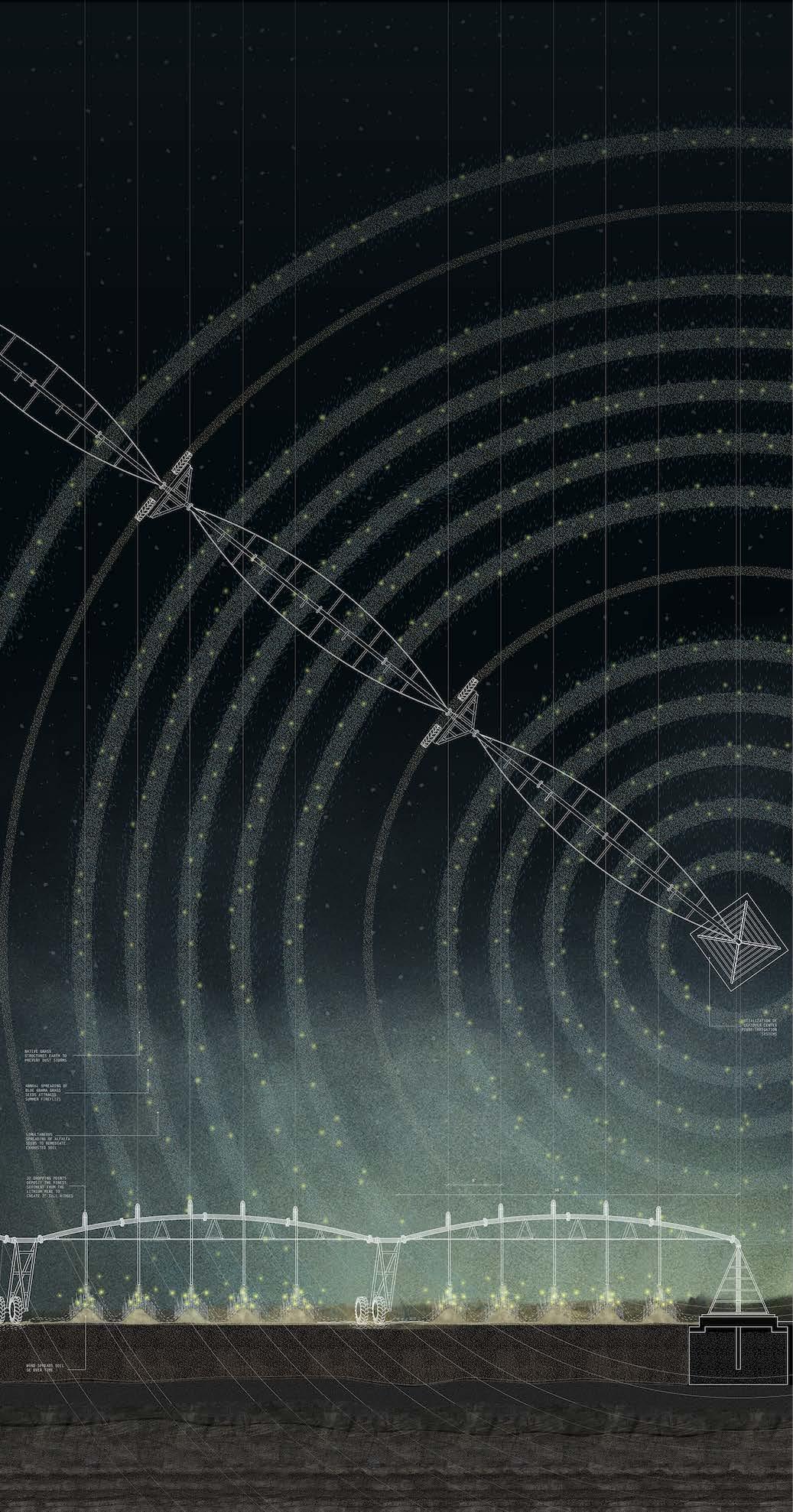

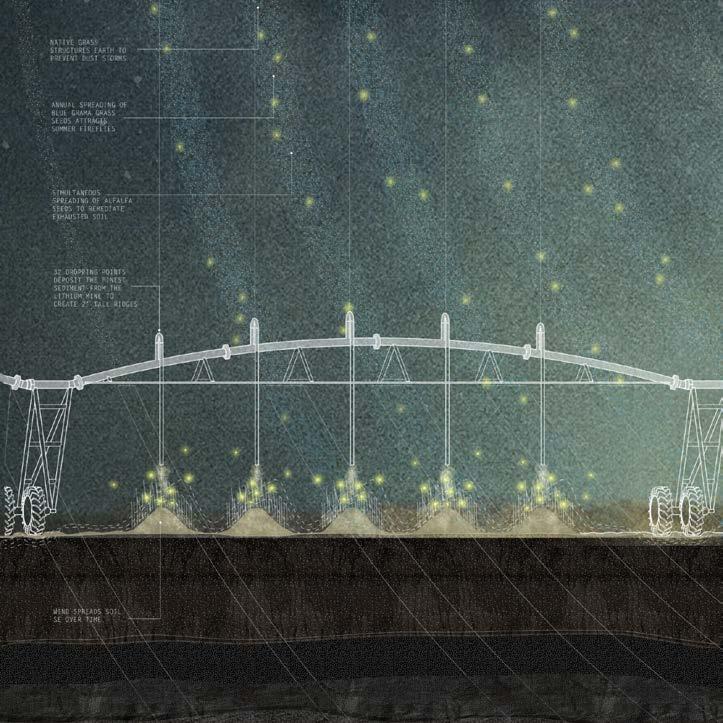

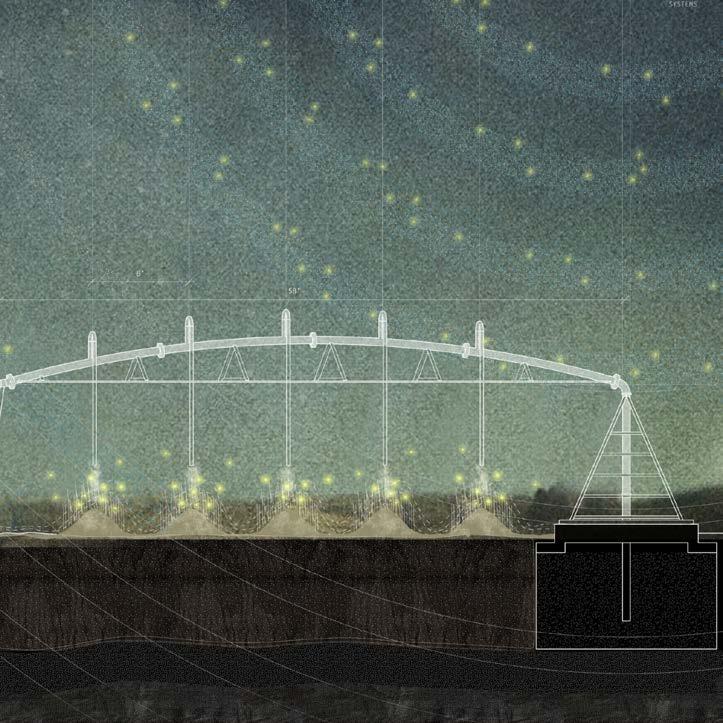

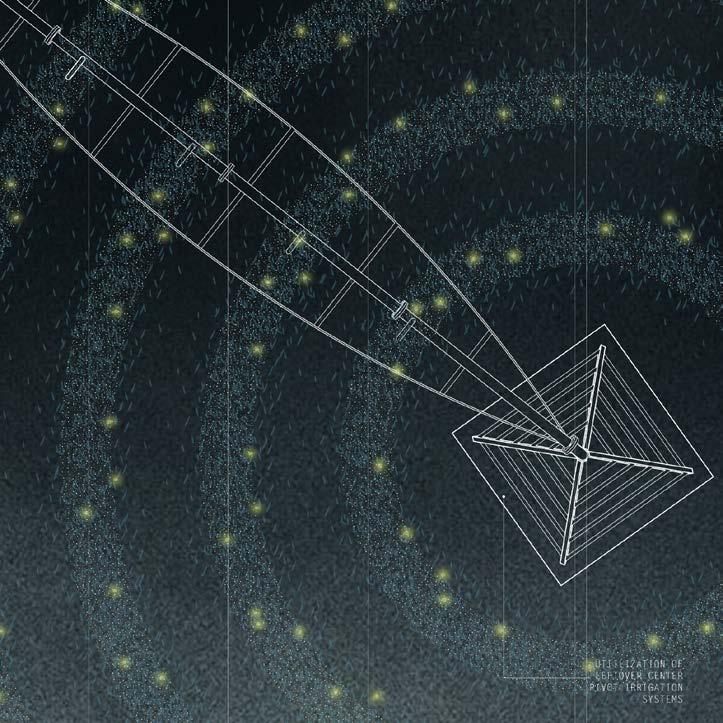

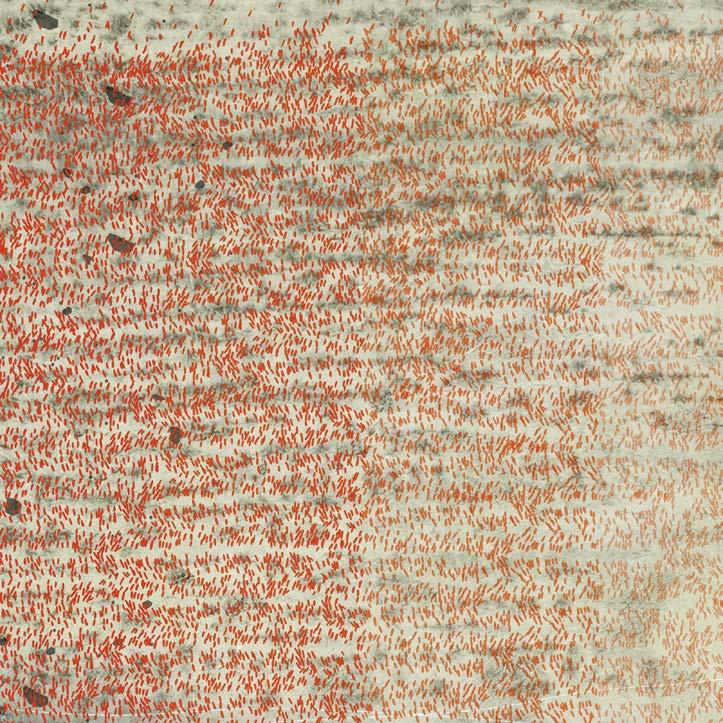

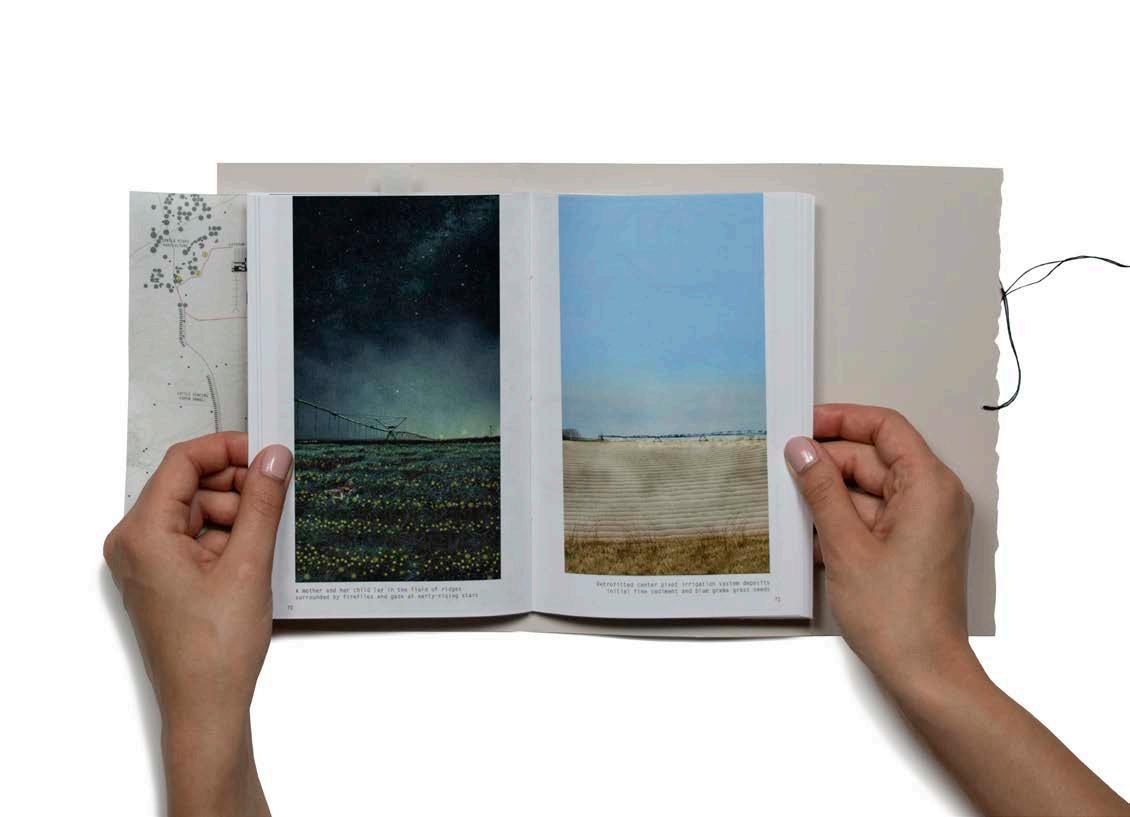

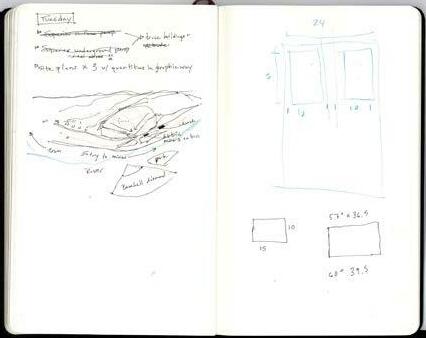

SITE 1: PIVOT | CENTER PIVOT AGRICULTURE DESIGN STRATEGY

PIVOT utilizes leftover circle pivot irrigation infrastructure as sediment sprinklers after groundwater levels decrease to a point that nearby farmers transition to dry-farming. 32 dropping points along the irrigation system deposit the finest sediment from the lithium mine pond excavation. These create 3ft tall ridges which are simultaneously planted with Blue Gramma grass seeds, which require little water and attract fireflies during summer months. The center pivot deposition system completes a rotation every six months, depositing the seeds annually on the Spring Equinox. The grass structures the earth to prevent dust storms in the newly dry landscape.

135 IX-a Sites of Stewardship | PIVOT

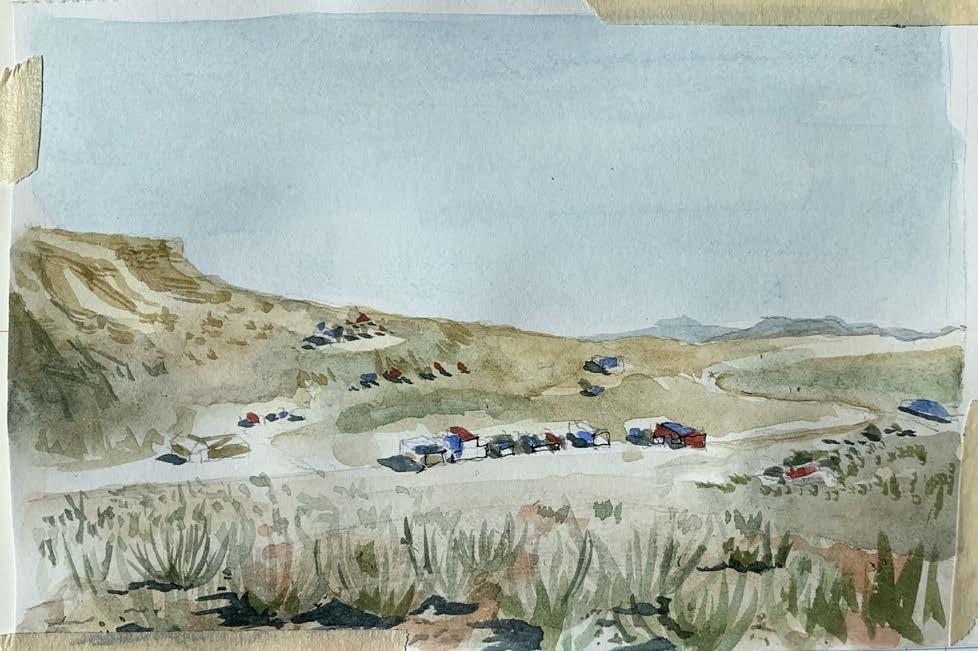

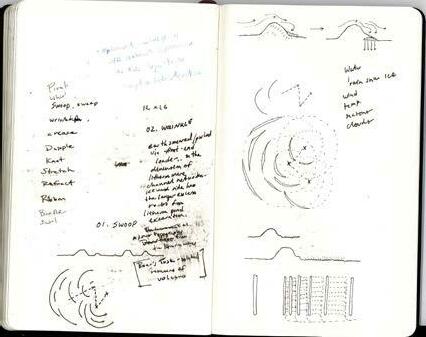

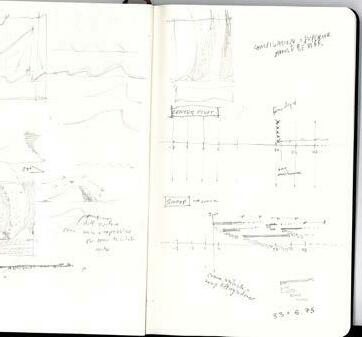

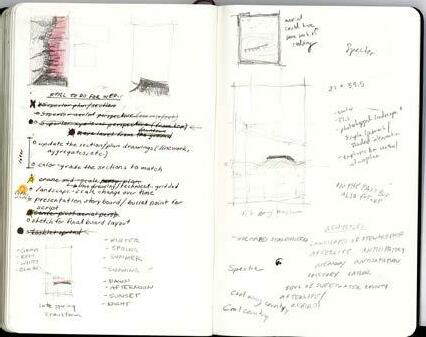

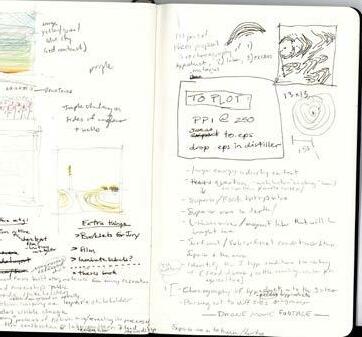

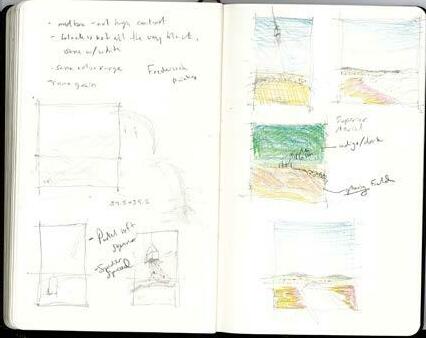

Early charcoal sketch

136

137 IX-a Sites of Stewardship | PIVOT PIVOT

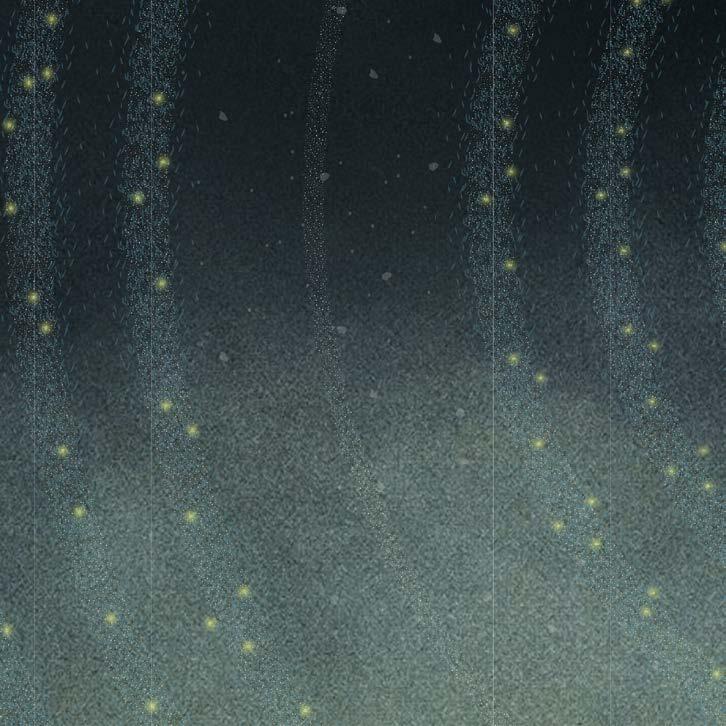

SITE 1: PIVOT | CENTER PIVOT AGRICULTURE AERIAL VIEW

Halo-like rings of fireflies bear resemblance to the Milky Way overhead.

139 IX-a Sites of Stewardship | PIVOT

140

SITE 1: PIVOT | CENTER PIVOT AGRICULTURE EYE LEVEL EXPERIENCE

A mother and her child lay in the field of ridges, surrounded by fireflies, and gaze at early rising stars.

141 IX-a Sites of Stewardship | PIVOT

SITE 1: PIVOT | CENTER PIVOT AGRICULTURE EYE LEVEL EXPERIENCE

Retrofitted center pivot irrigation system deposits initial fine sediment and blue grama grass seeds.

143 IX-a Sites of Stewardship | PIVOT

144 IX-b

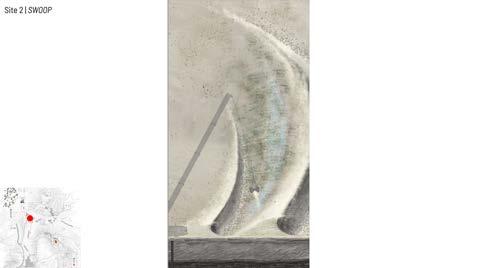

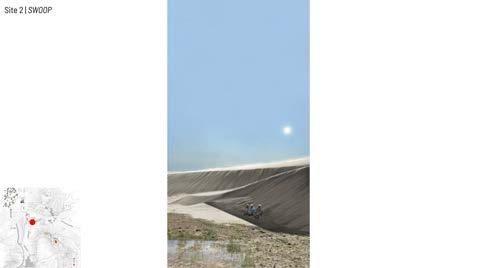

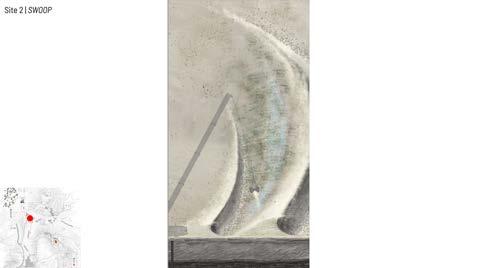

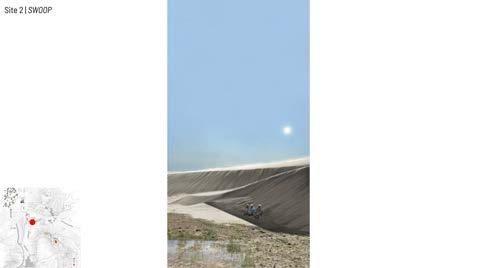

SITES OF STEWARDSHIP

SITE

2: SWOOP

Riparian Sand Dunes Remediate Boreholes

145 IX-b Sites of Stewardship | SWOOP

146 +0 ft .25 mi

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

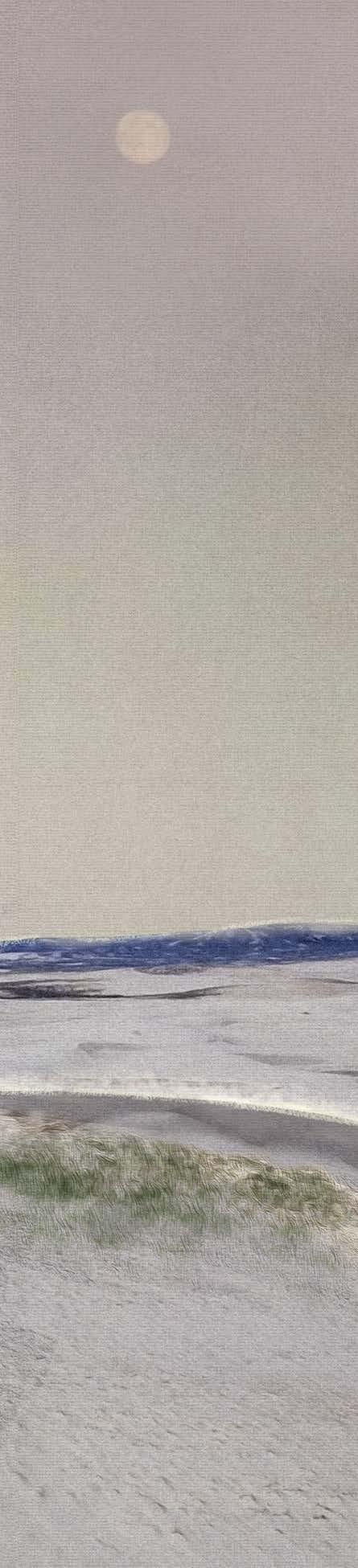

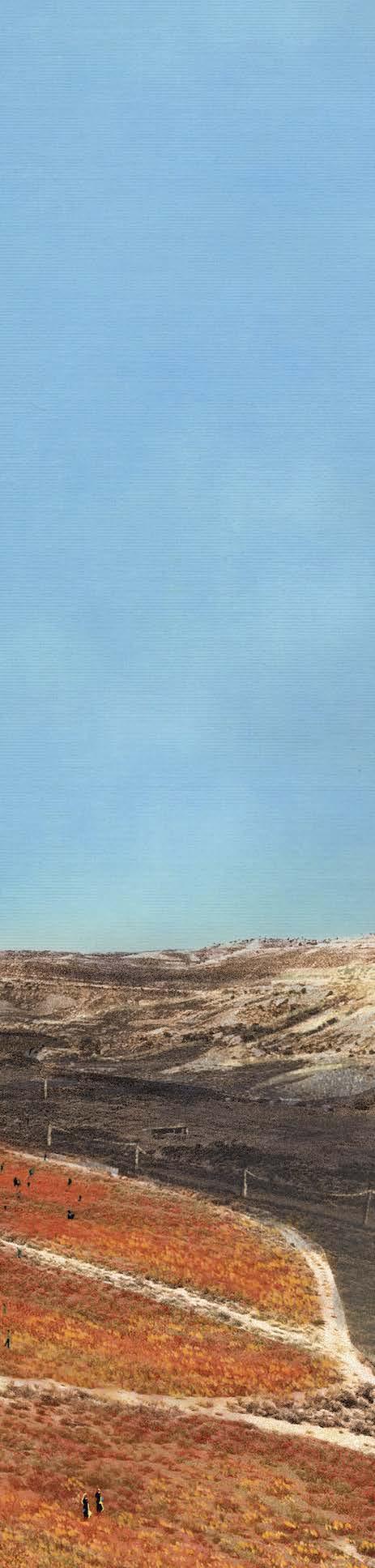

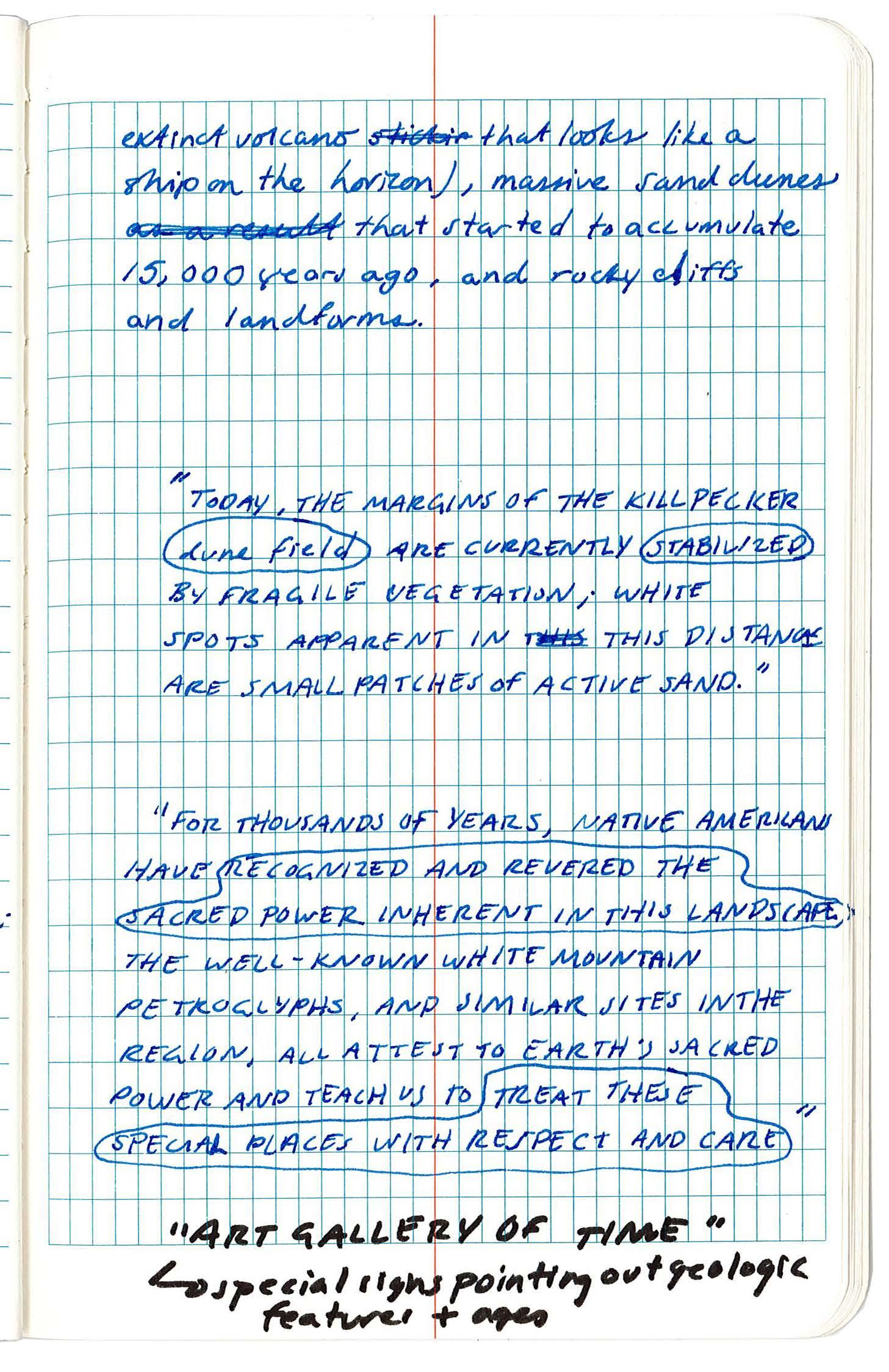

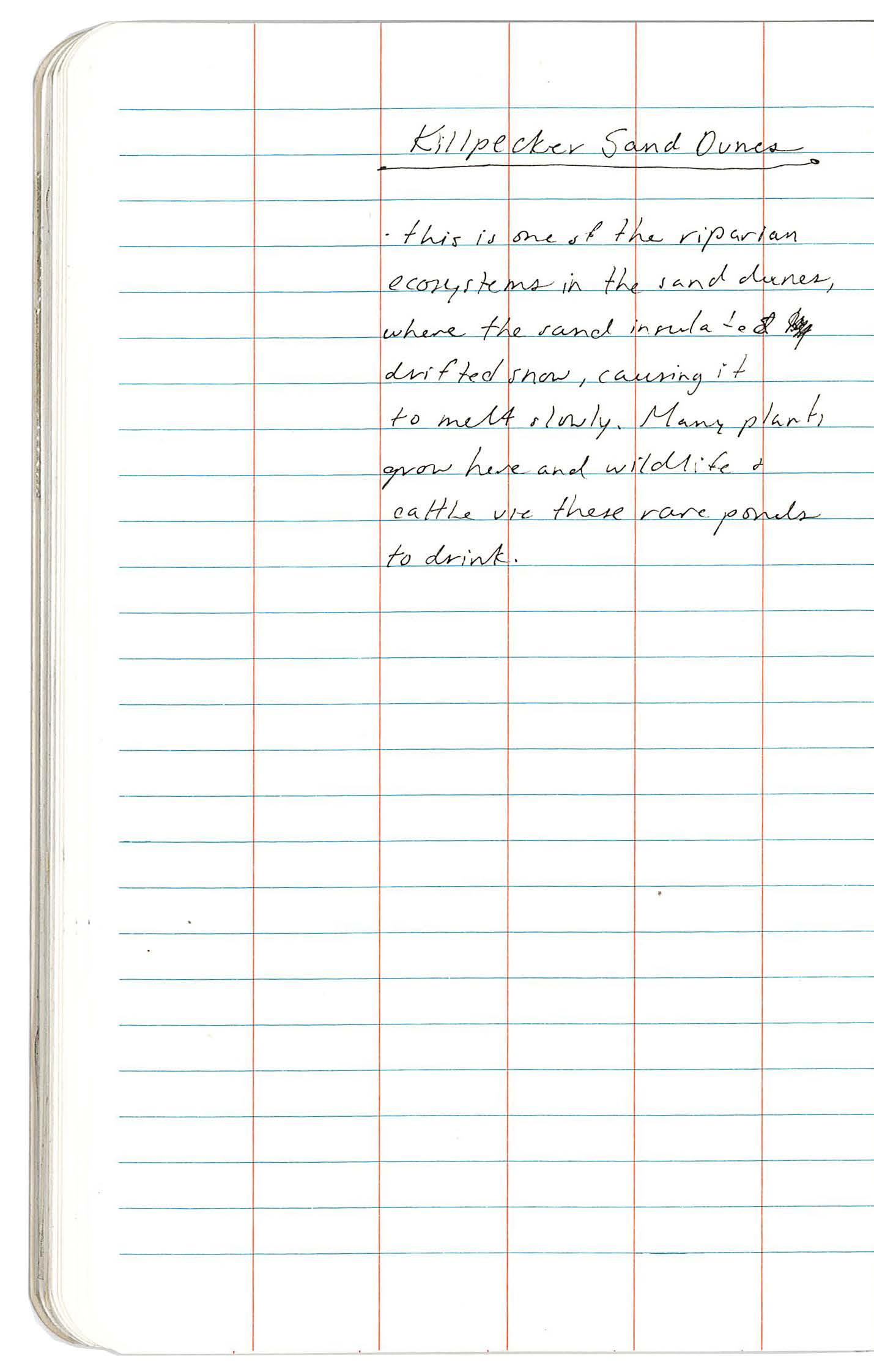

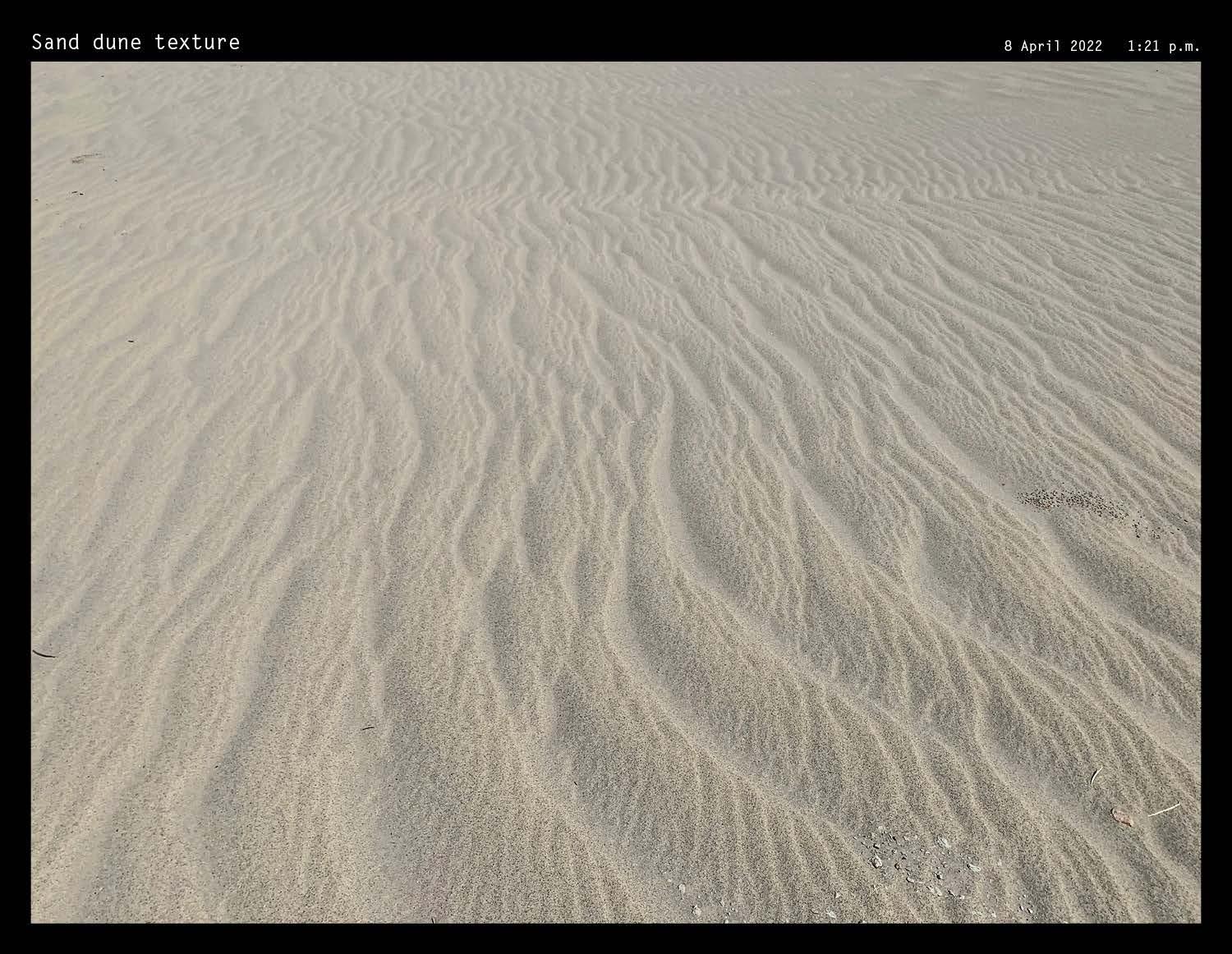

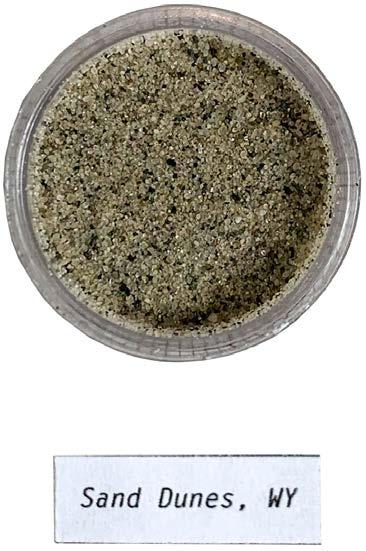

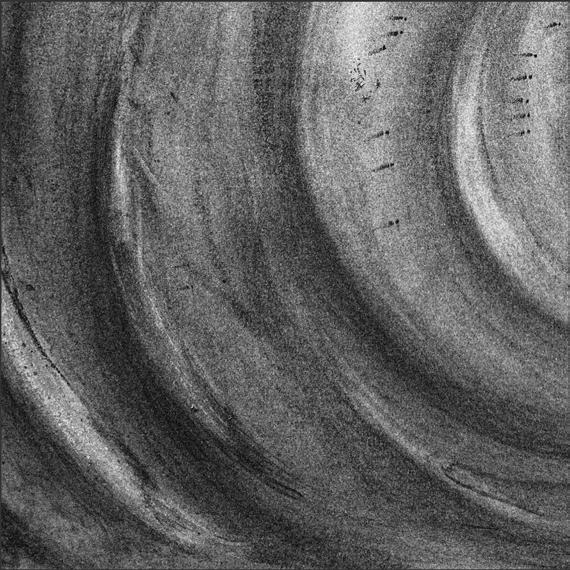

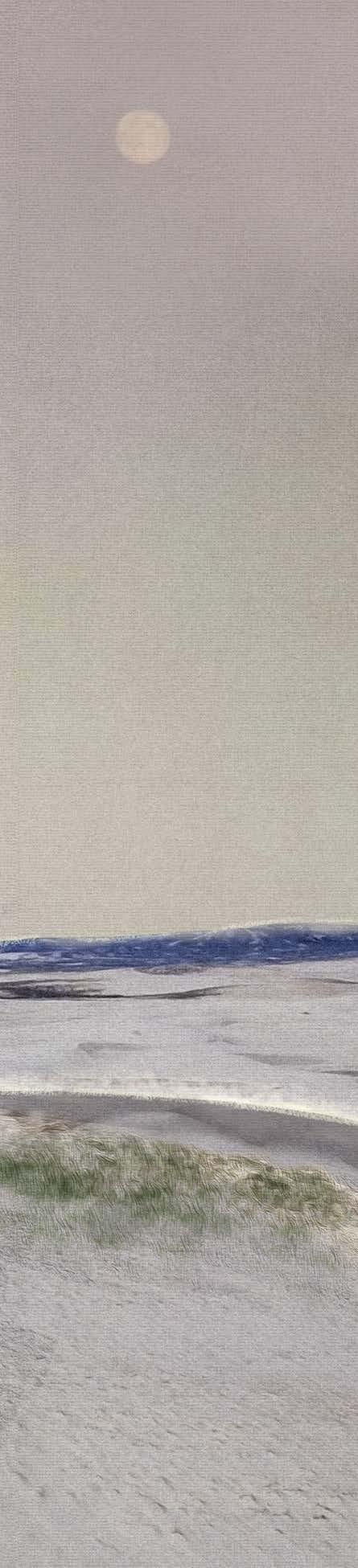

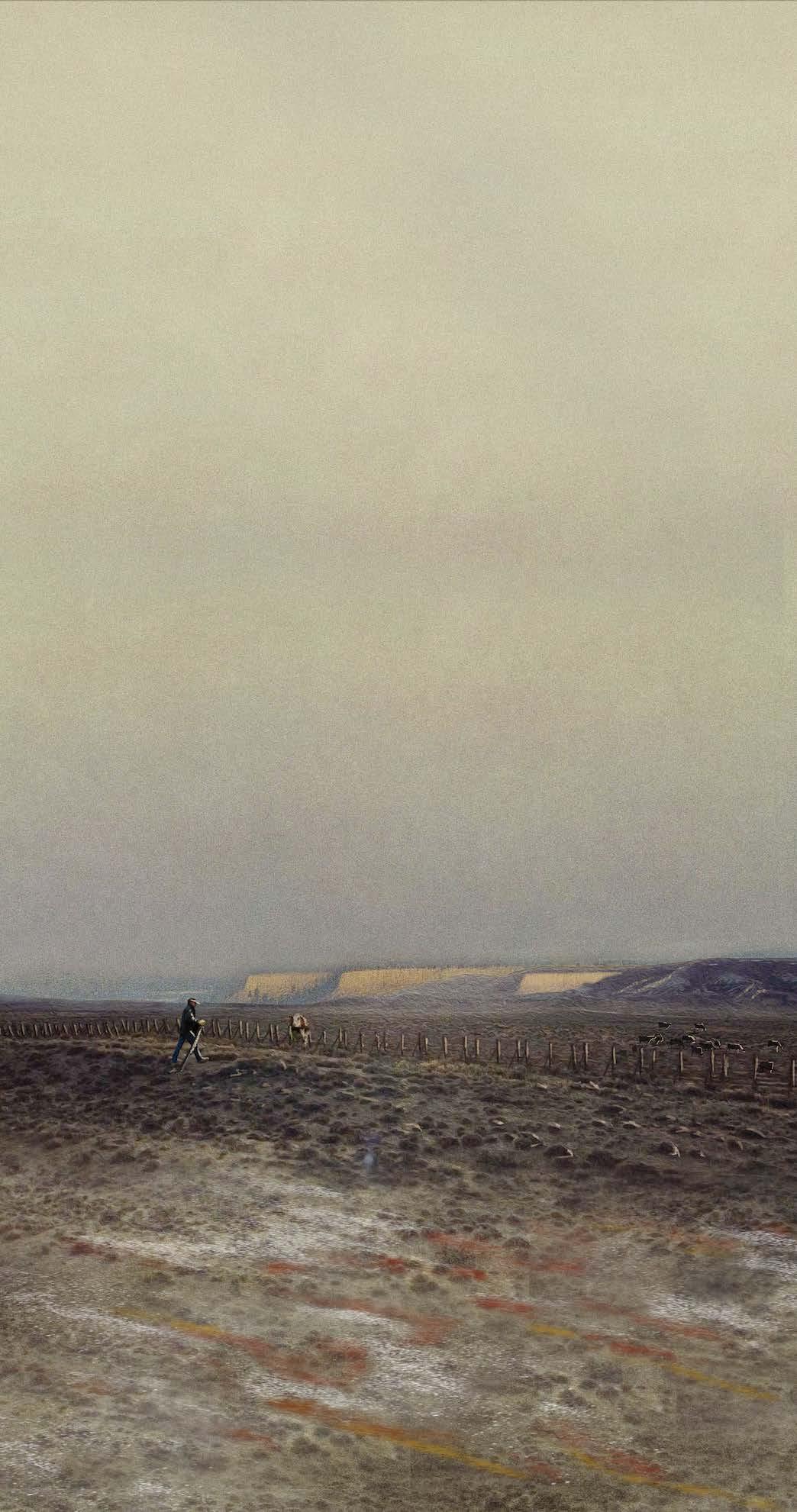

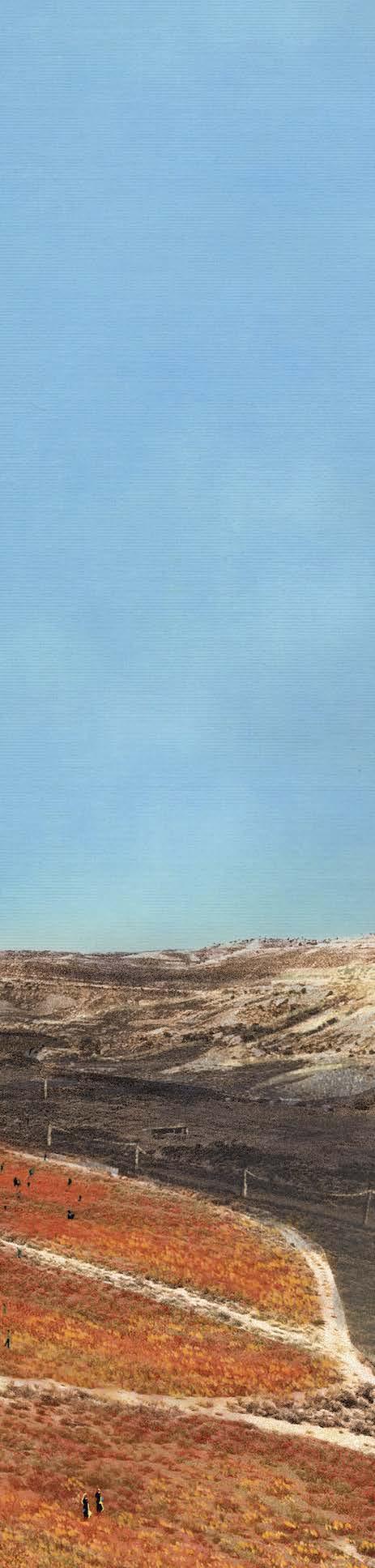

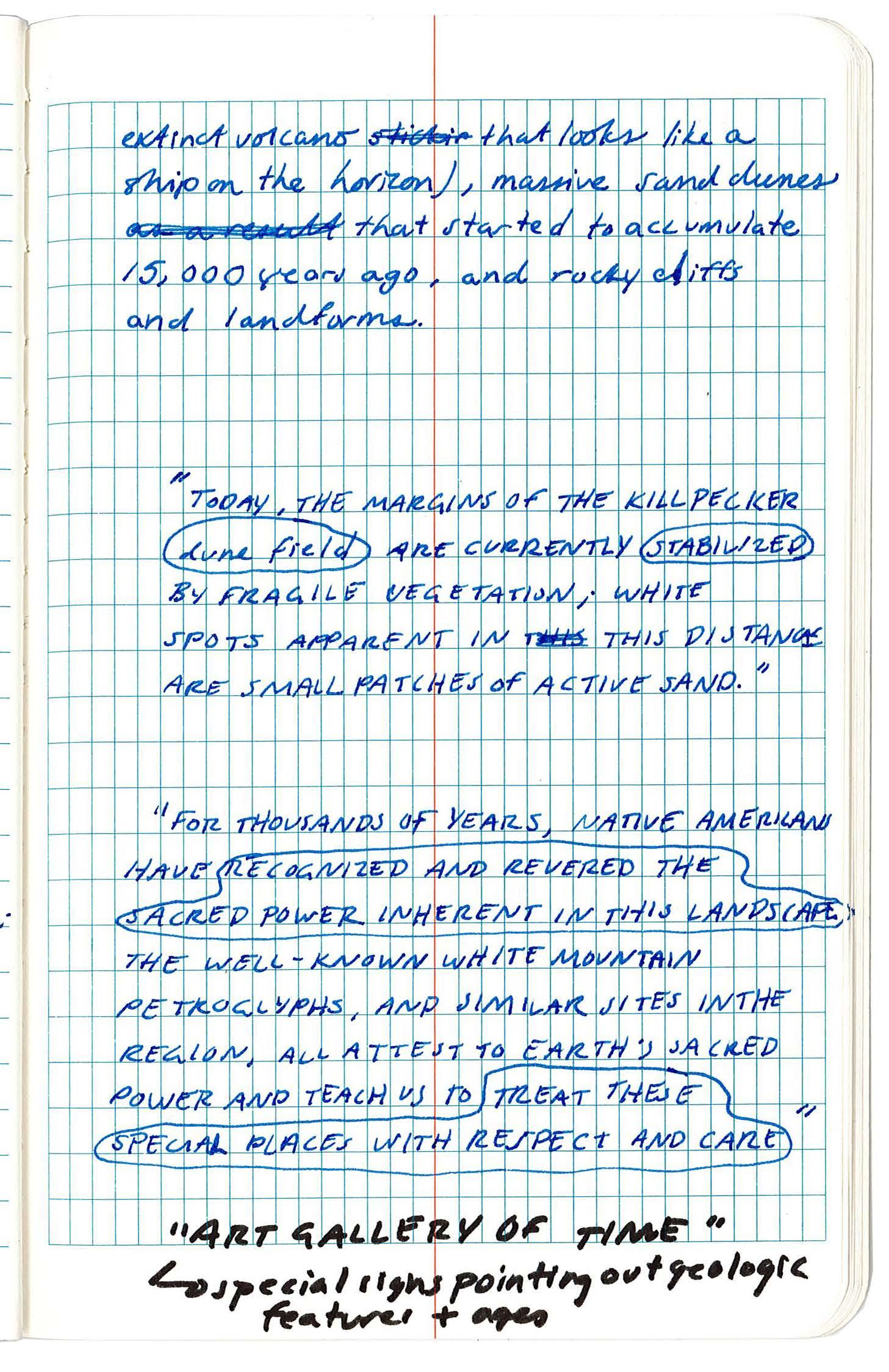

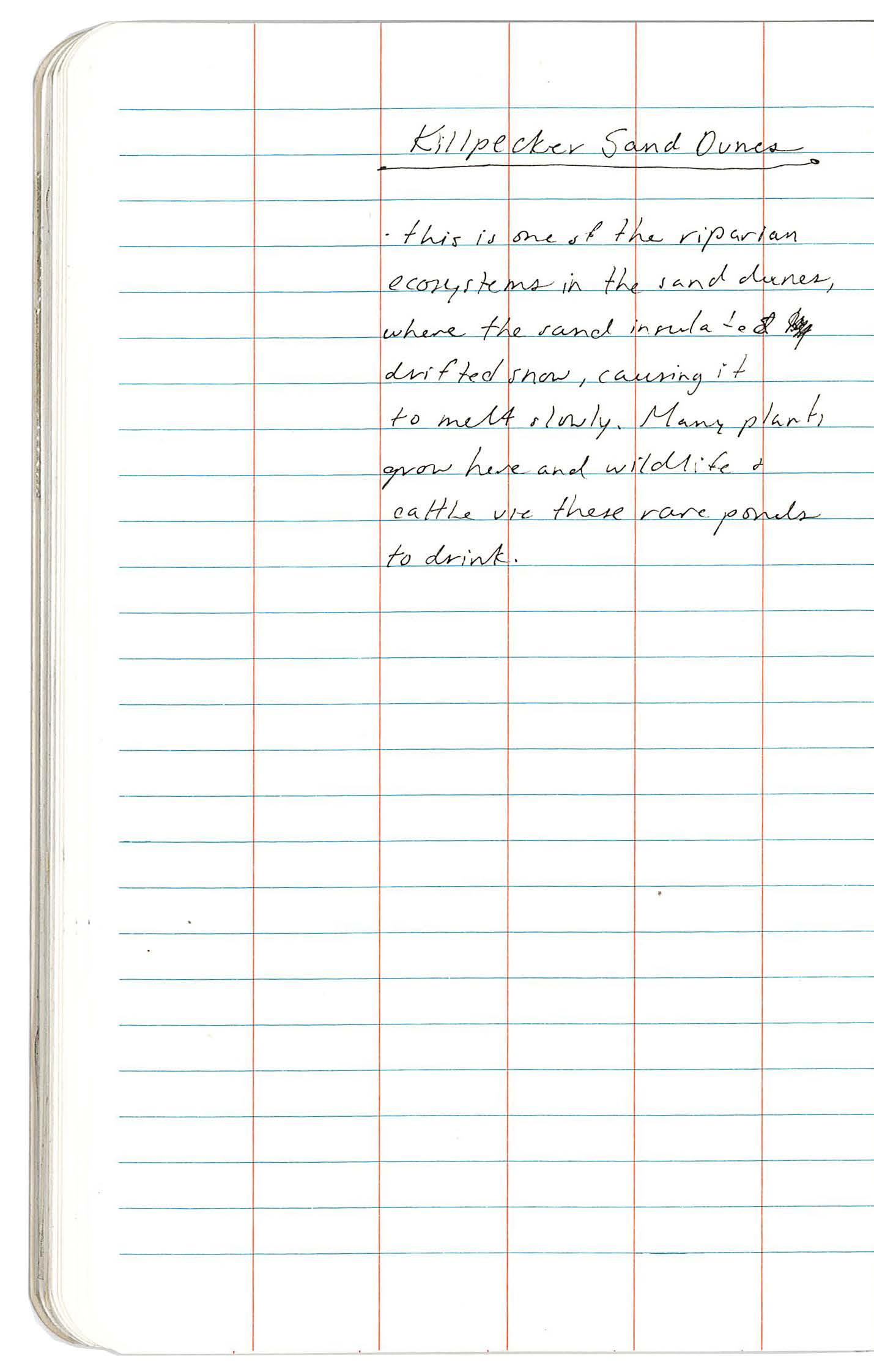

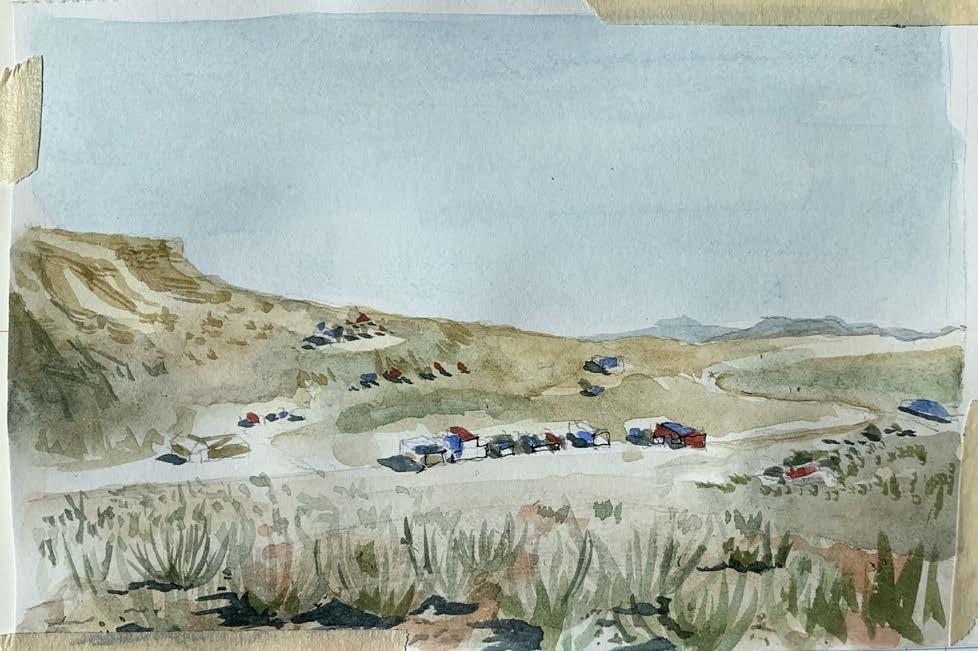

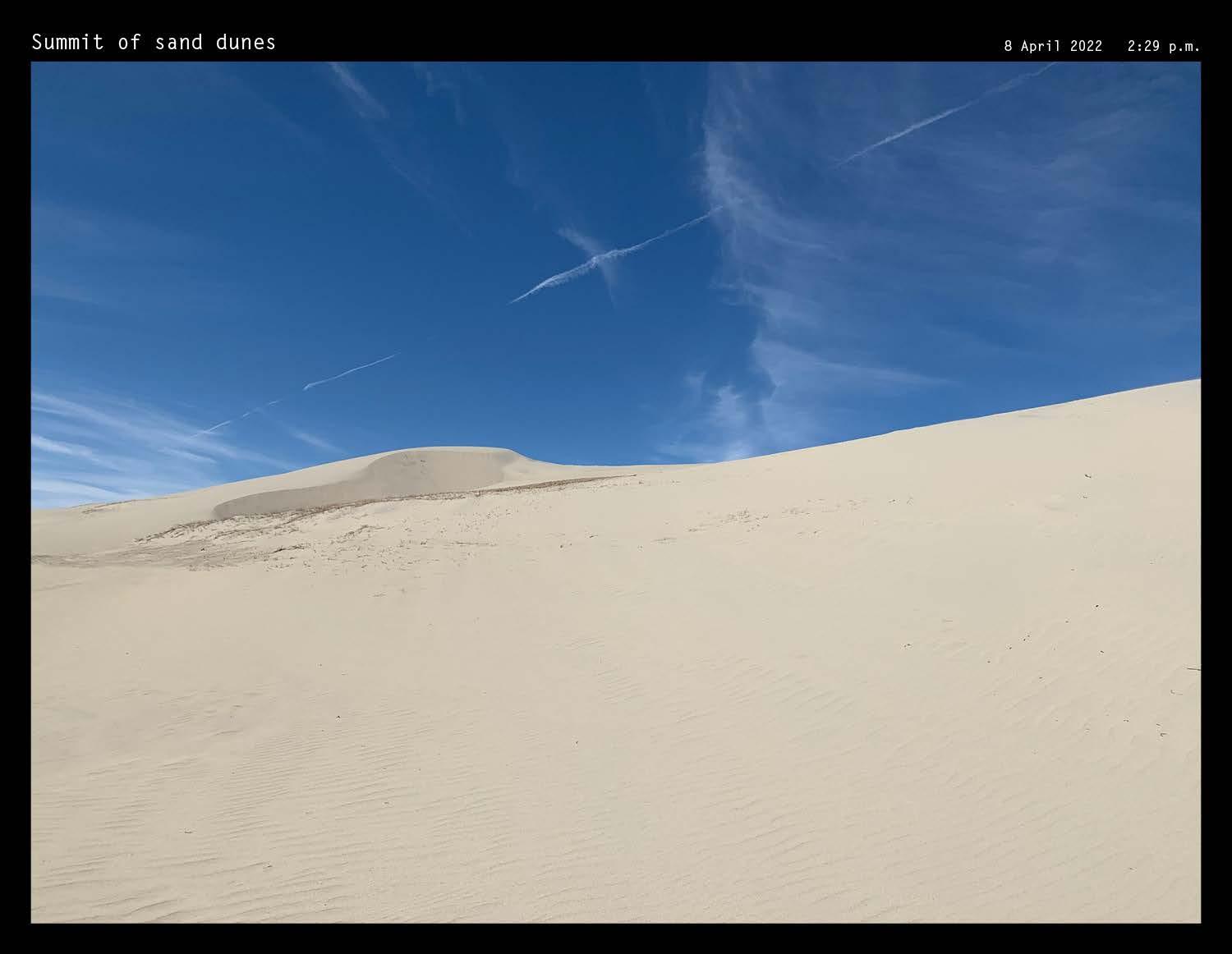

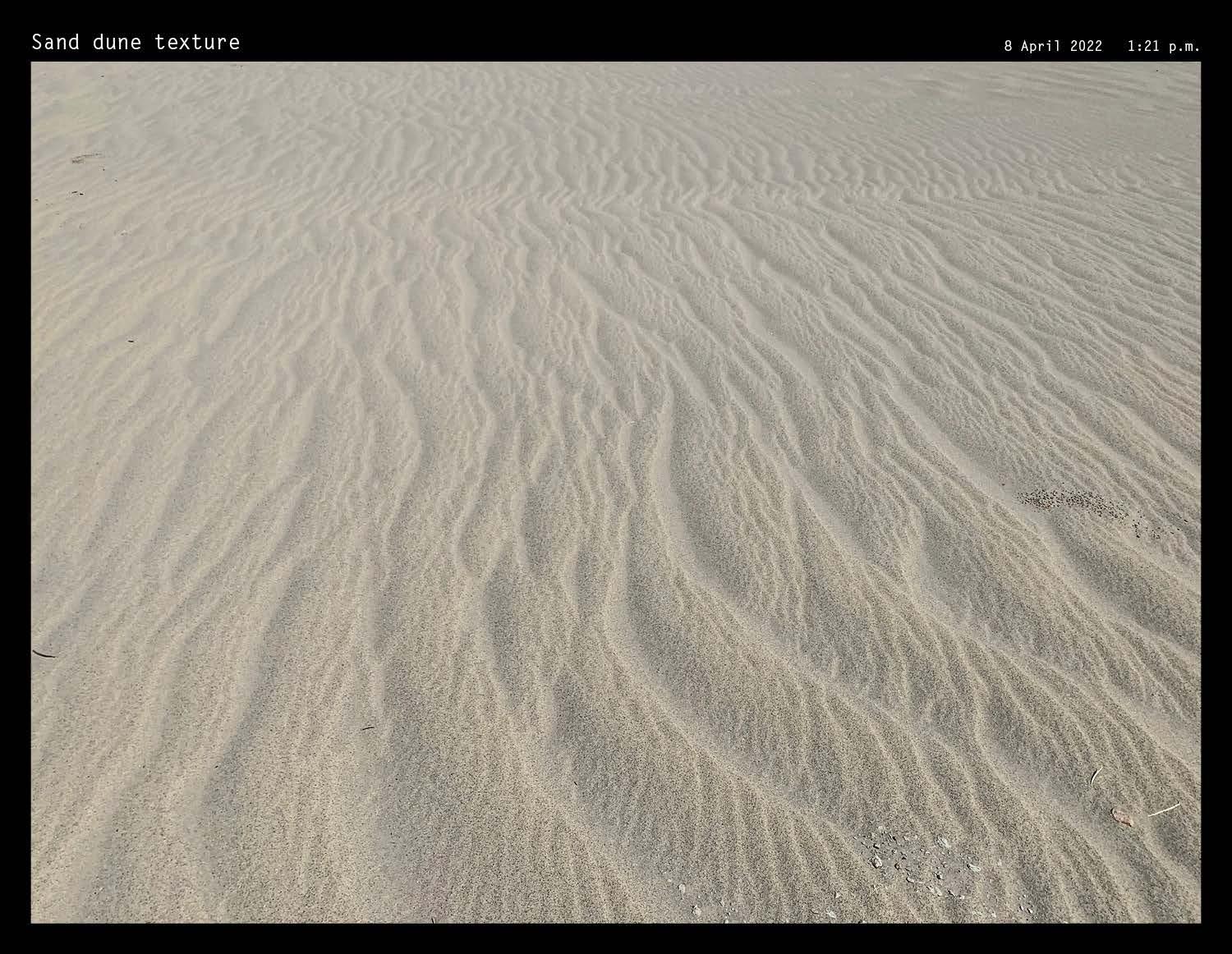

The Killpecker Sand Dunes, a field of naturally occurring dunes shaped over 15,000 years of high winds blowing sand from the Big Sandy River, is currently used as a tourist destination for dune buggies and sand surfing.

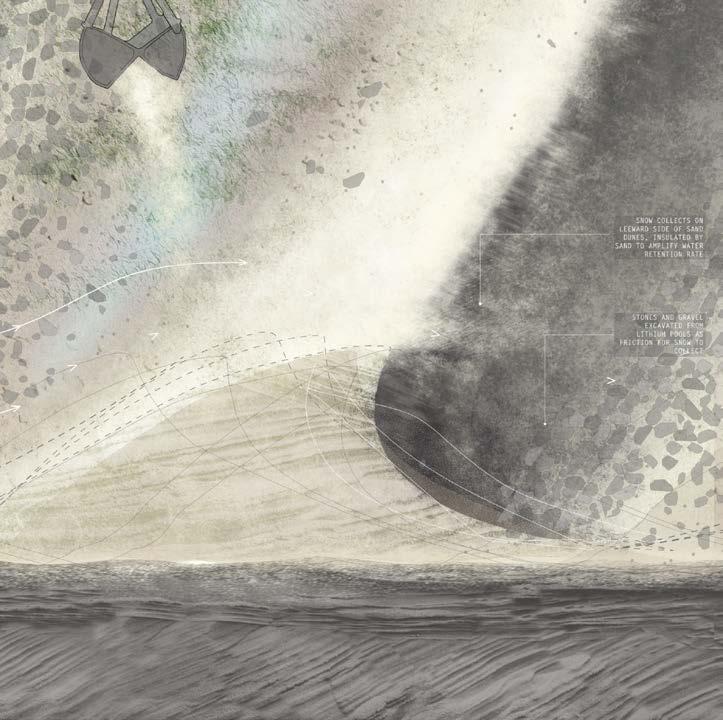

Along with recreational activities, the sand dune ecosystem also harbors a plethora of riparian life, to the great interest of conservationists in the area. Sand blows over drifted snow in the wintertime and compresses it into ice, delaying the rate of water retention. This creates seasonal wetland ponds where cattle and antelope drink and graze.

147 IX-b Sites of Stewardship | SWOOP

SITE 2: SWOOP | SAND DUNES

148

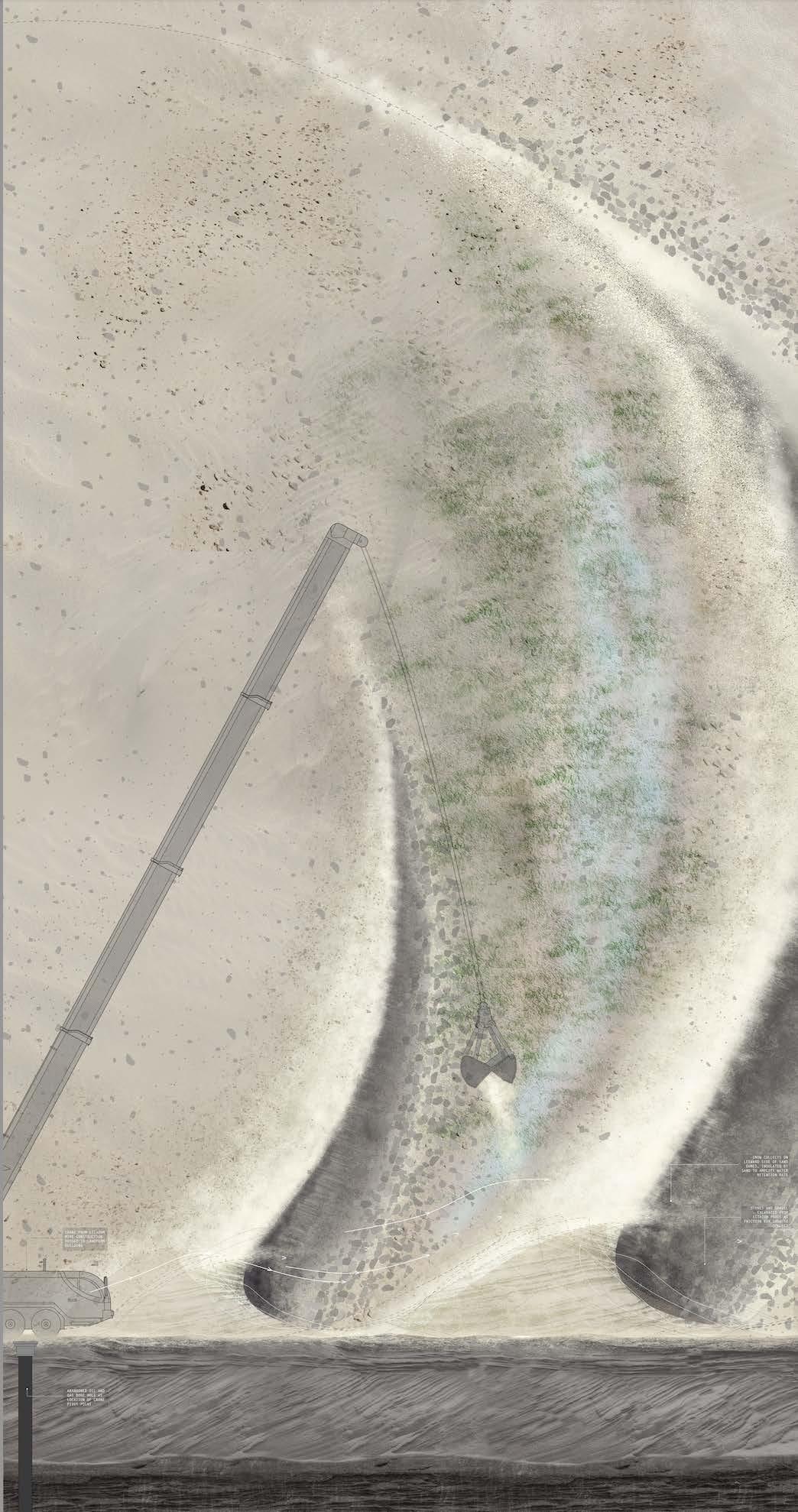

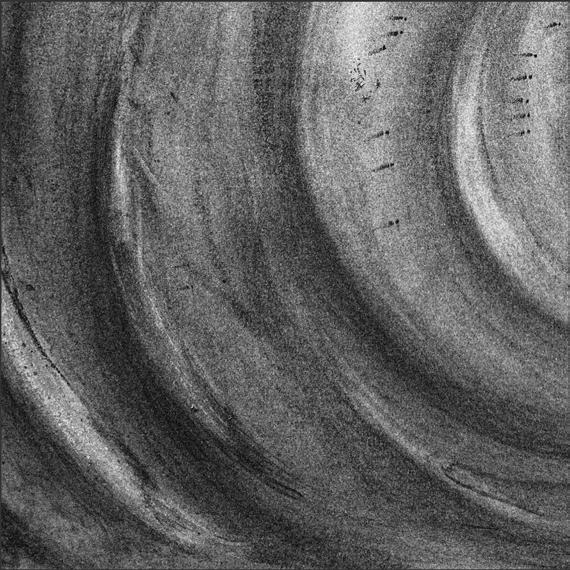

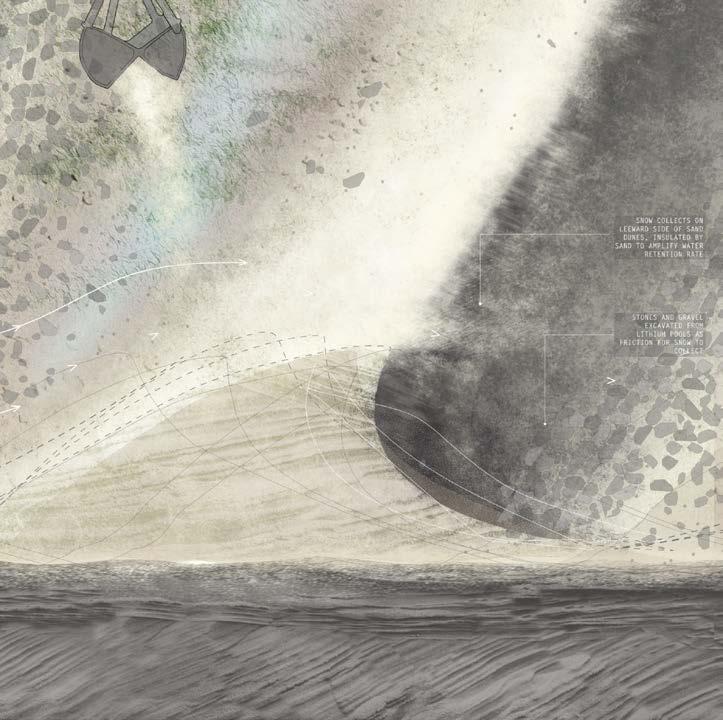

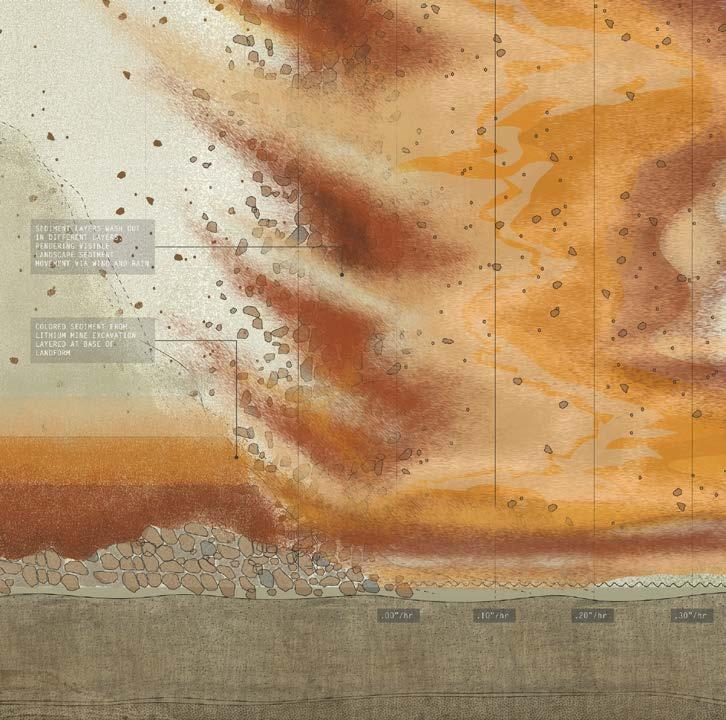

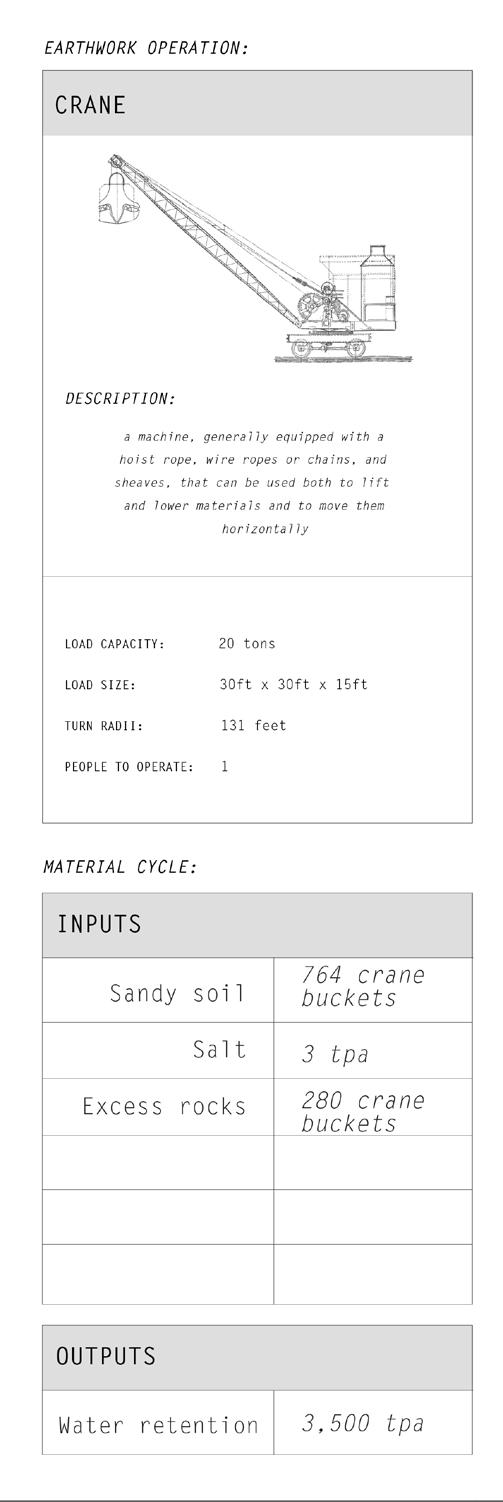

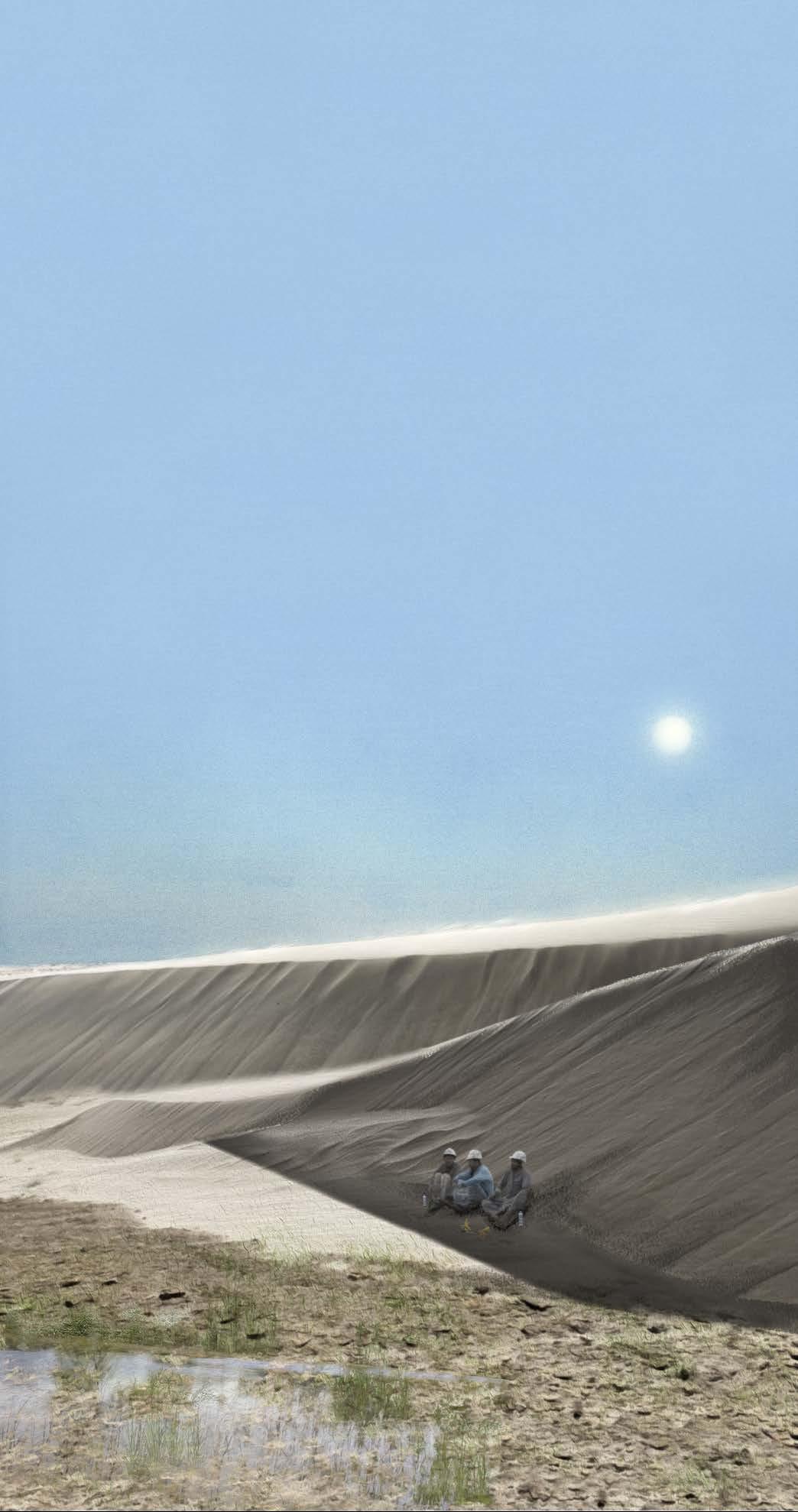

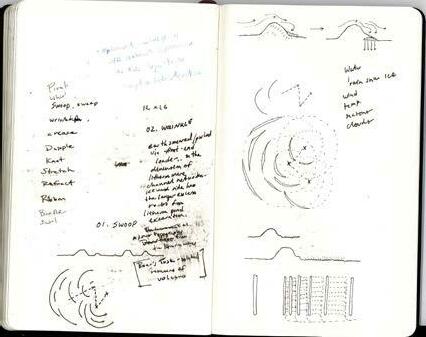

SITE 2: SWOOP | SAND DUNE DESIGN STRATEGY

Engaging with the natural processes of sand dune formation by wind, SWOOP is constructed preemptively in anticipation of groundwater drying up due to the lithium mine. Swoop is deposited by the swinging of a crane’s arm as it traces the path of abandoned infrastructural scars on the ground. Each pivot point marks the borehole of a previous drilling operation. Aggregating sand on its leeward sides to intensify the natural process of water retention and pondmaking from snow compacted under layers of sand, it simultaneously remediates the land marred by past extractive systems while anticipating the reduction of the water table due to the mine. A constructed barometer in the landscape, it renders visible and measures possible salt deposition due to wind direction as it relates to seasonal change as sand ebbs and flows.

149

IX-b Sites of Stewardship | SWOOP

Early charcoal sketch

150

151 IX-b Sites of Stewardship | SWOOP SWOOP

SITE 2: SWOOP | SAND DUNE AERIAL VIEW

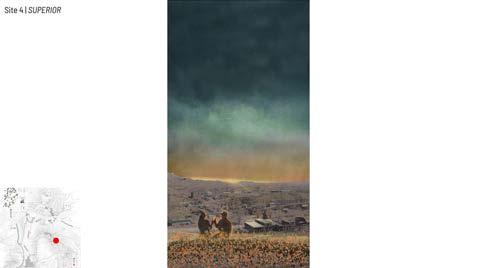

Antelope graze near a wetland pool made possible by the sand dune swoop remediating an abandoned borehole.

153

IX-b Sites of Stewardship | SWOOP

154

SITE 2: SWOOP | SAND DUNE EYE LEVEL EXPERIENCE

Oil field workers eat lunch sheltering from the harsh sun in the shade of a sand dune swoop.

155 IX-b Sites of Stewardship | SWOOP

156

SITE 2: SWOOP | SAND DUNE EYE LEVEL EXPERIENCE

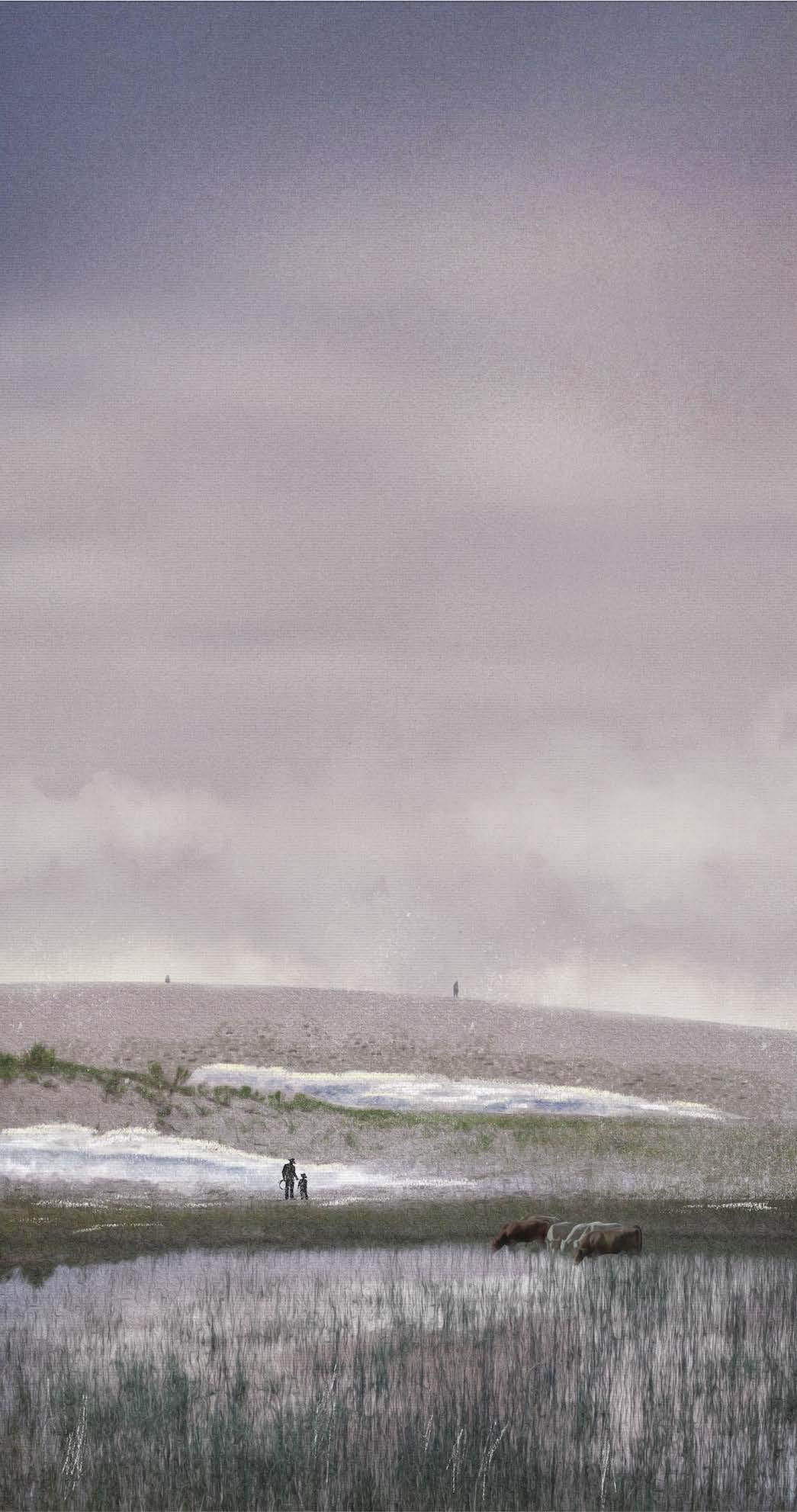

A rancher and his son watch cattle drink at dawn while snowdrifts melt.

157 IX-b Sites of Stewardship | SWOOP

158 IX-c

SITES OF STEWARDSHIP

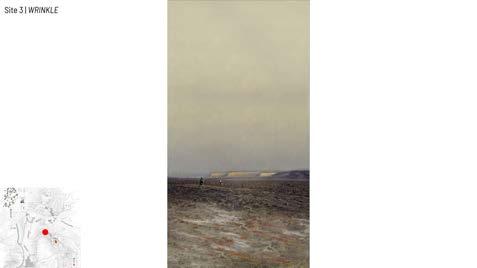

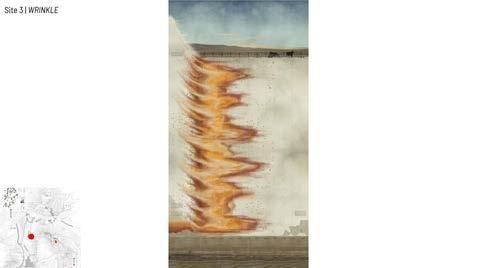

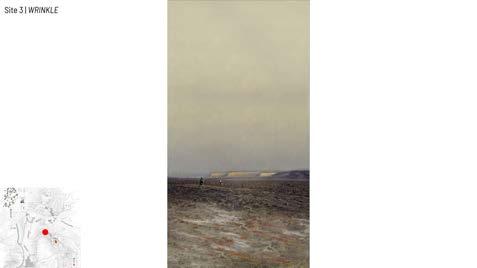

SITE 3: WRINKLE

Landscape as Litmus Test and Measuring Device

159 IX-c Sites of Stewardship | WRINKLE

160 +0 ft .25 mi

Map by Gracie Meek. Data from the United States Geological Survey, the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMaps

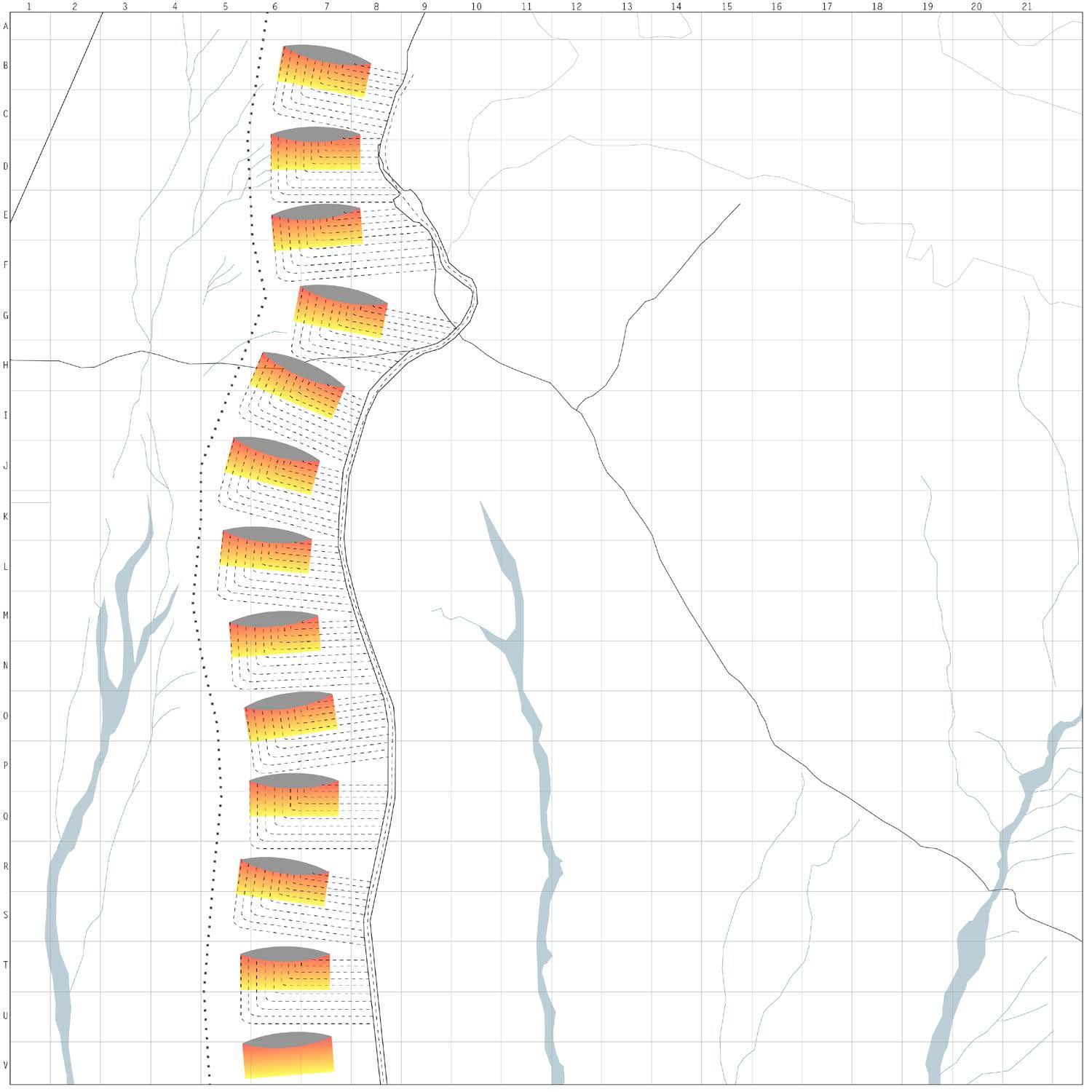

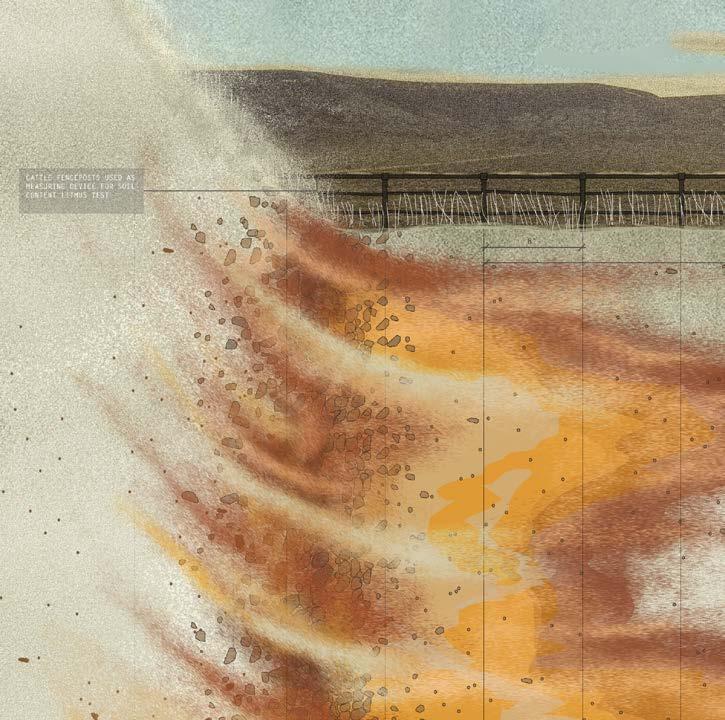

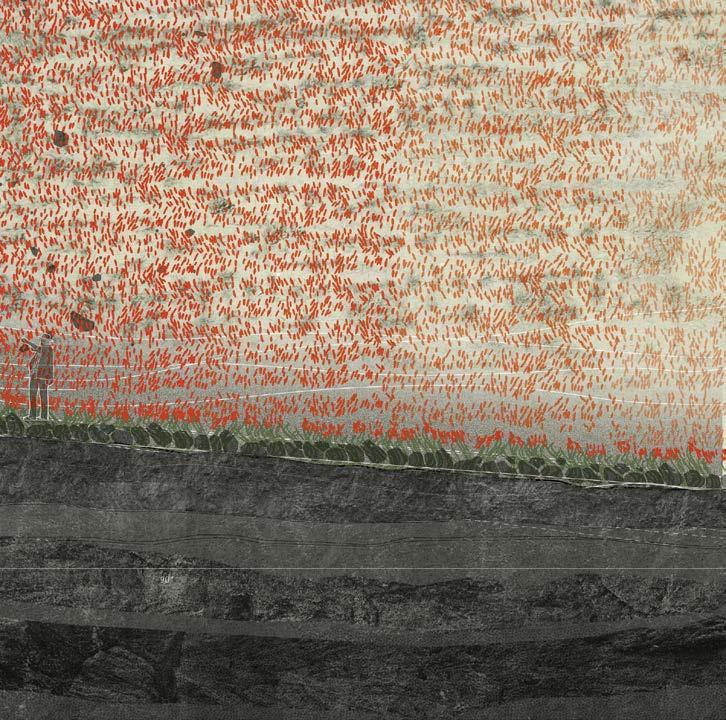

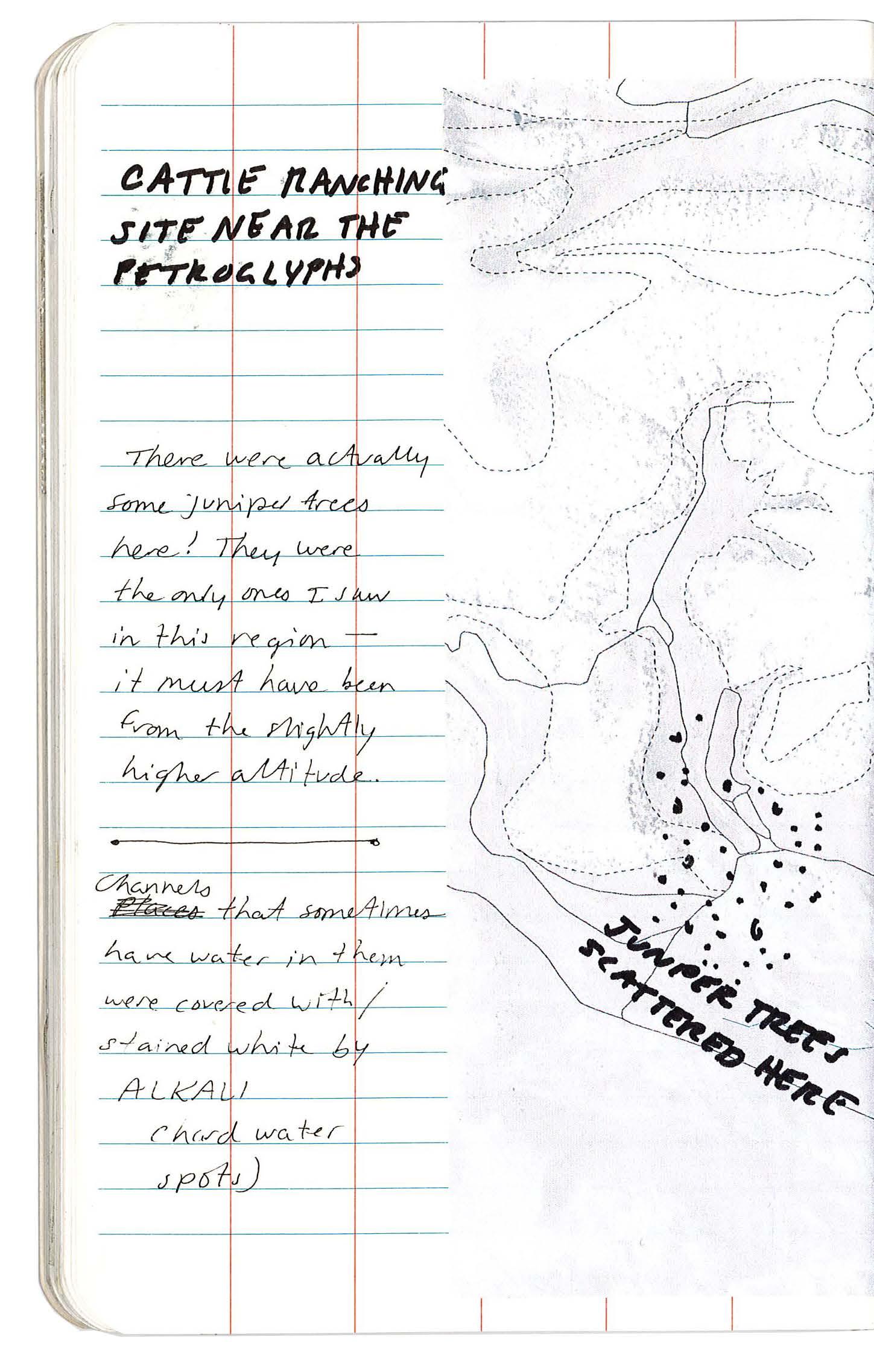

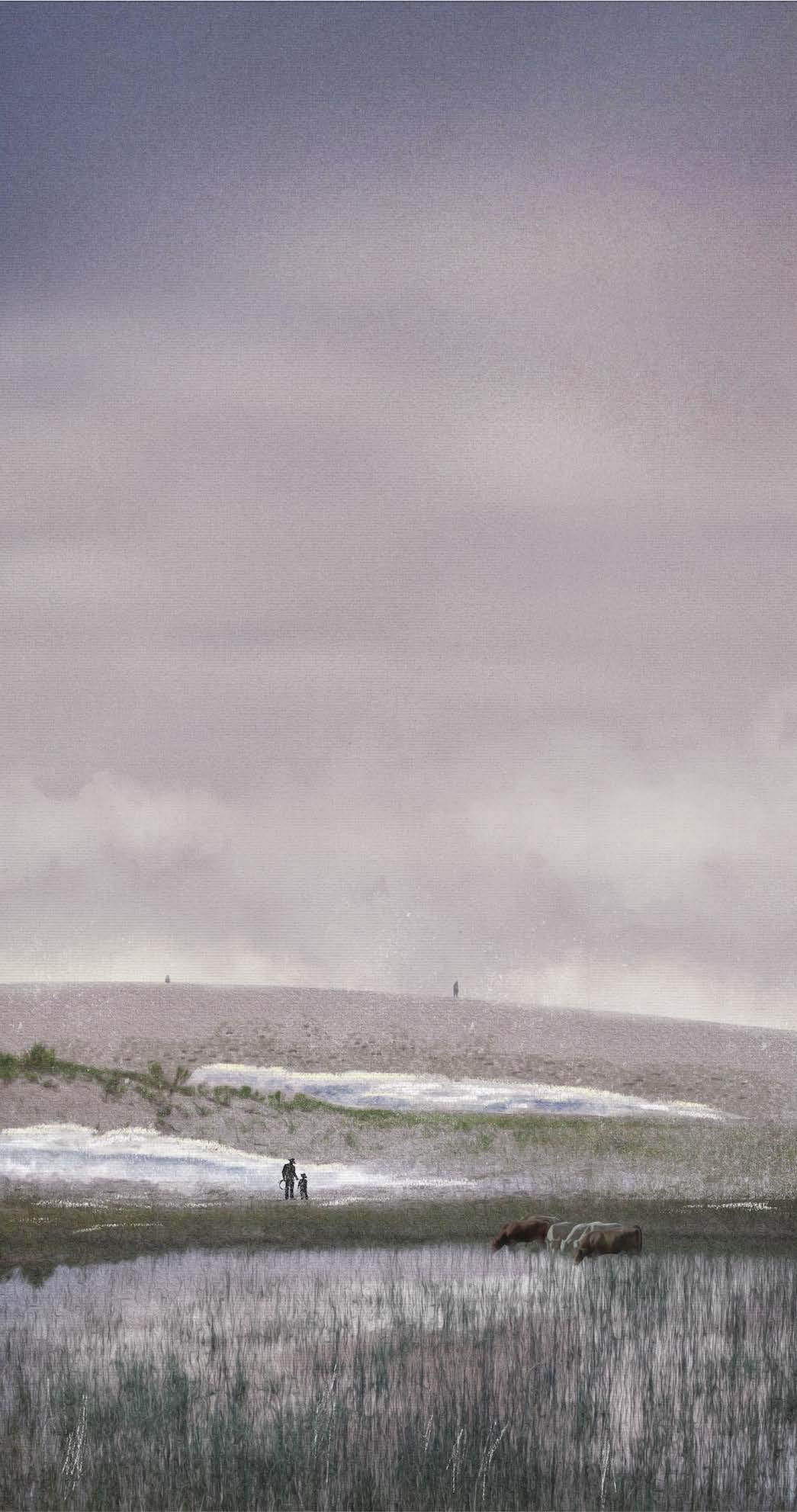

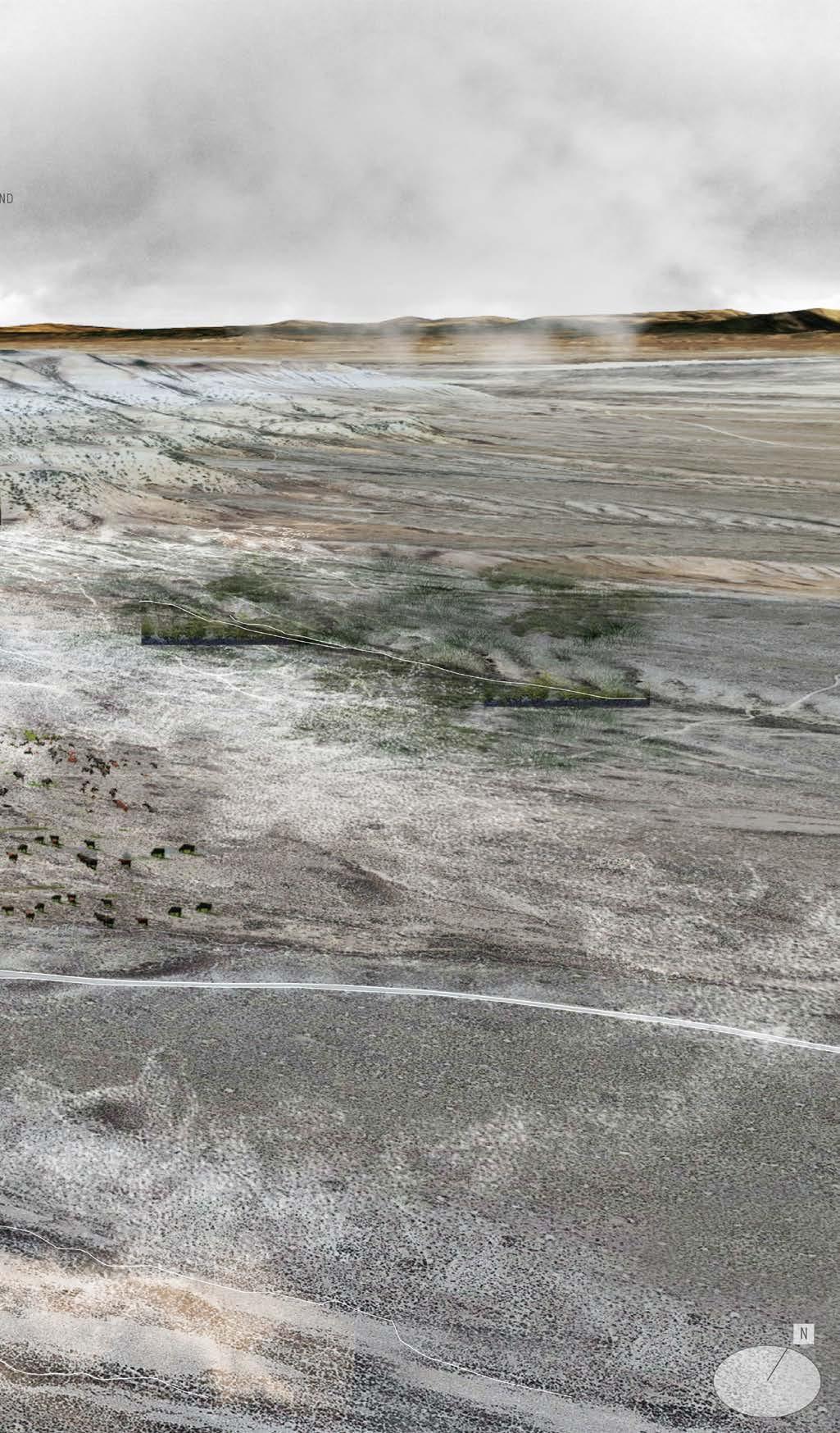

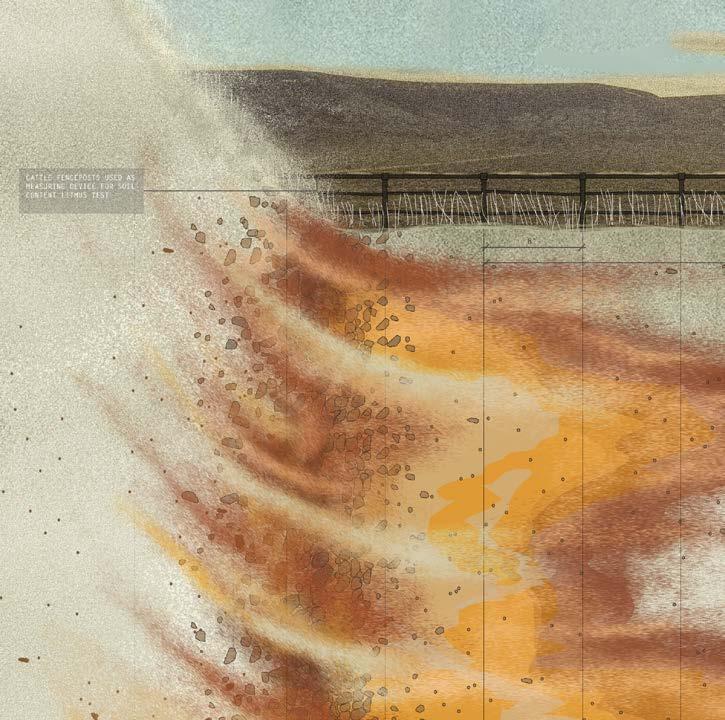

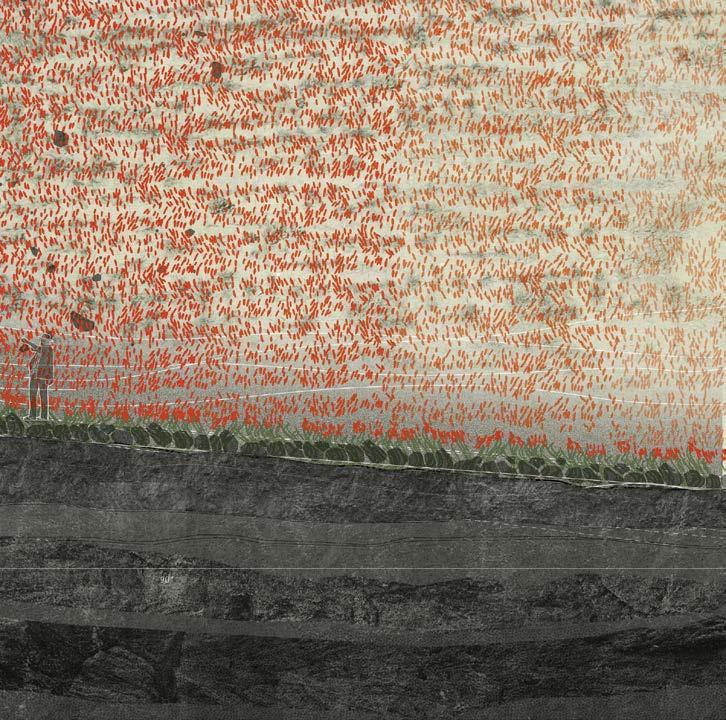

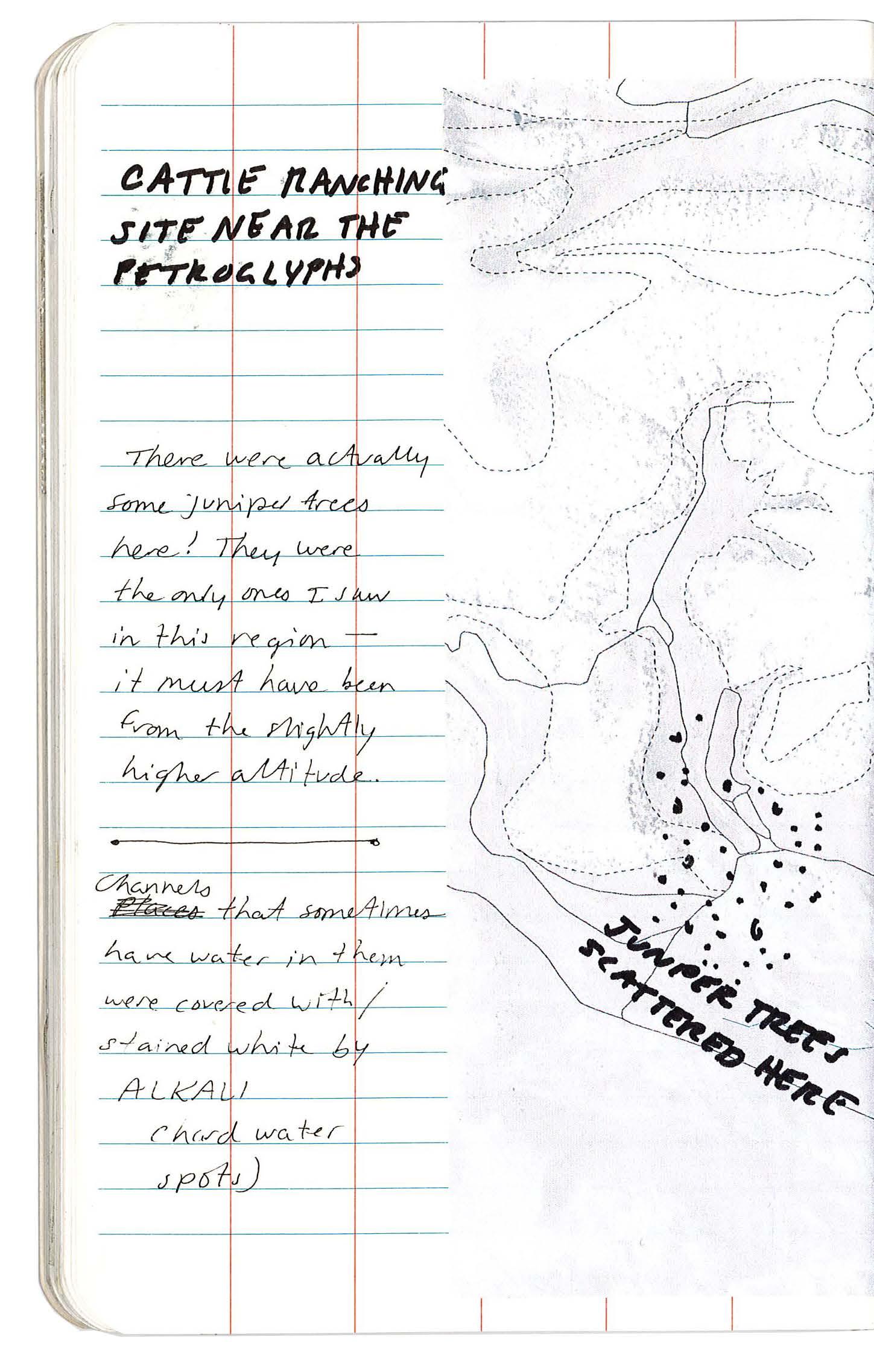

3: WRINKLE | CATTLE RANCHING

Land practices on Site 2 consist of cattle ranching, where typical herds reach 100 heads. Light-colored sandy cliffs with seasonal streams characterize the rangeland, where cattle ranchers fear that groundwater levels will drop due to the future mine. If this happens, the grassland ecosystem that the cows rely on for food will be parched.

Site 2 utilizes salt as salt licks for cattle, and Magnesium and Potassium for essential dietary nutrition.Like Site 1, ash can be used in the soil to improve water retention capabilities in soil as an anticipatory measure for future drought conditions exacerbated by the lithium mine.

161 IX-c Sites of Stewardship | WRINKLE

SITE

162

SURFICIAL ANALYSIS OF SITE 3

Surficial view onto Site 3 expressing cattle rangeland and possible flow of contaminants over sandy cliffs via seasonal alluvial channels.

163

IX-c Sites of Stewardship | WRINKLE

164

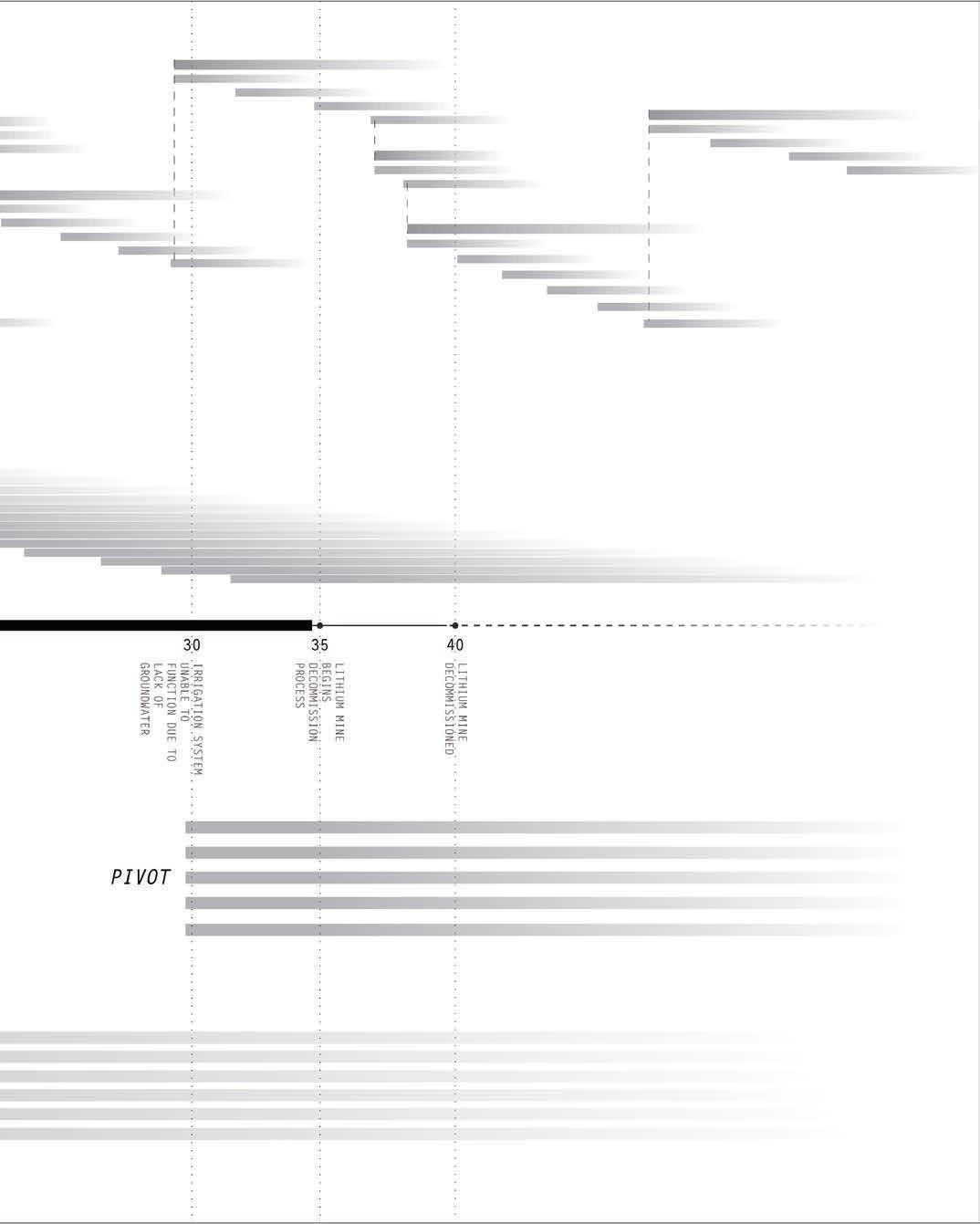

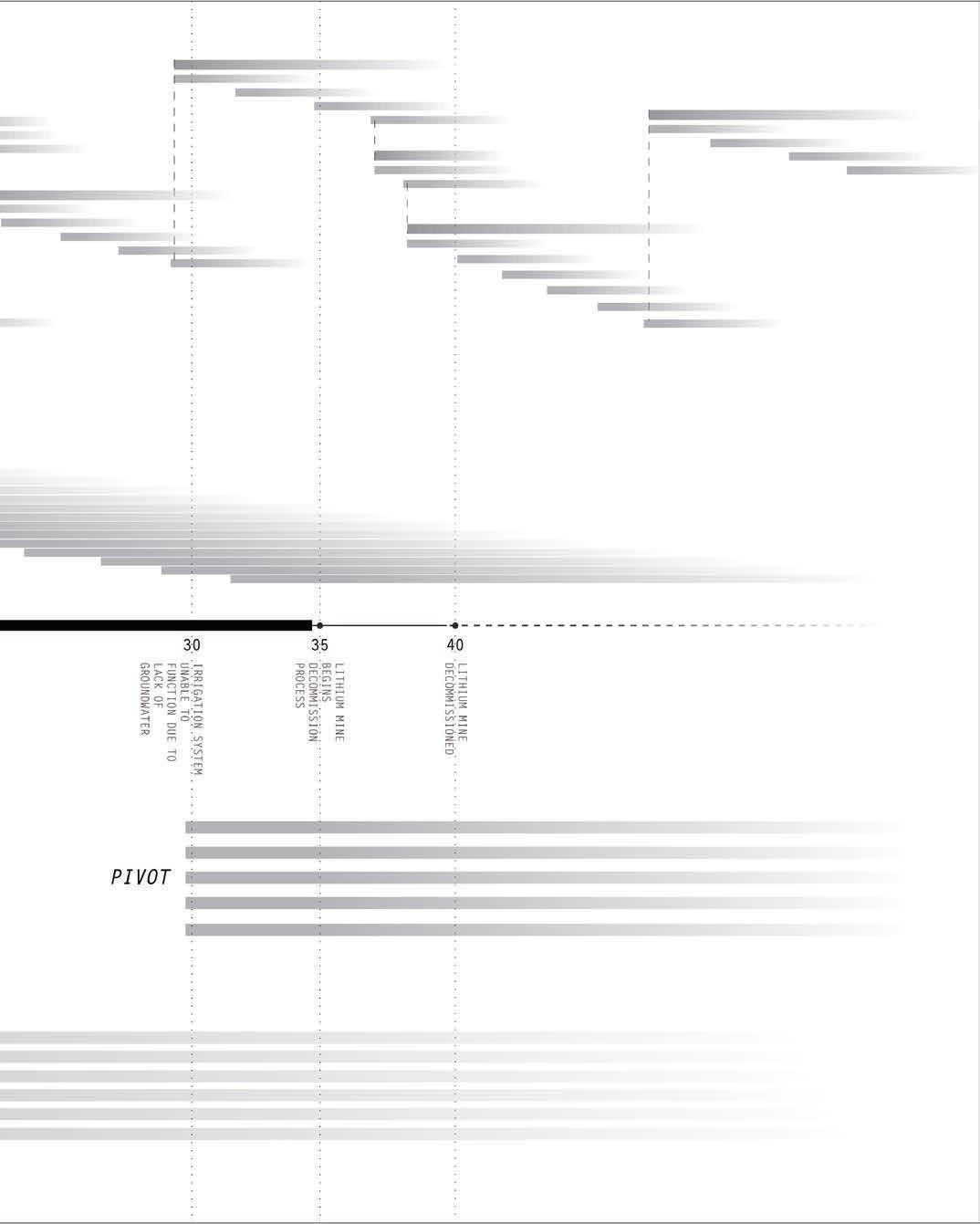

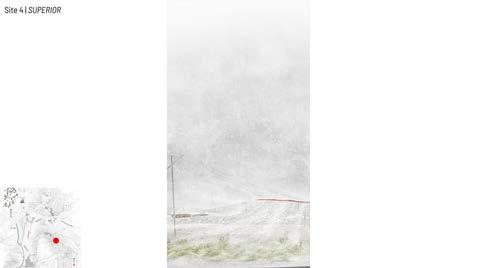

Surficial