18 minute read

REGULARS

Darralanganha Dhulubang (Restless Spirits) (100cm x 50cm) By Dylan Barnes

This artwork represents the vibrant spirits of my queer Indigenous community and the sharing of experiences and power through our connections. We as queer/trans people are able to create a sense of solidarity through our gender-nonconformity. I wanted my artwork to portray the importance of queer Indigenous communities and the feelings of liberation that come with the unification of our restless spirits.

Advertisement

REGULARS

F.R.I.E.N.D.S

I am just going to say it. I have never been a Friends fan. I know it is probably shocking to you and the rest of the modern world and trust me, I have received enough criticism to understand how deeply loved this show is. But alas, here I am making my distaste of Friends public.

My surface level issues are that I never understood the humour, and nothing about it really appealed to me. I was also raised on Seinfeld, which definitely has its own issues. I was always shocked at how many people scoffed at me or looked at me wide-eyed when I told them I don’t like Friends and that I have watched a grand total of 5 episodes. I started to think I was the one with the problem and I should give the show a chance.

So, I gave it a chance. I watched all of Friends. It was no easy task so I will hold for applause. Thank you, it was really hard for me and may I say, I’m glad I was never a fan.

If I were an impressionable youngster watching this show I would think that having a different body shape was unattractive, that toxic masculinity was a viable excuse for poor behaviour, having a parental figure be part of the LGBTIQ+ community is something to be ashamed of, and that the world around me consists of only white people (bar two side characters). But I am not an impressionable youngster and I am mature enough to understand the deeply problematic nature of Friends and pull it into question.

Let’s start with the rampant homophobia and transphobia present in the show shall we? Friends could have broken ground in being a positive LGBTIQ+ show that challenges the opinions of the day and been one of the first mainstream TV shows to accurately portray people from the queer community properly. Instead they resorted to cheap gay panic jokes and constantly having gay, lesbian and transgender people be the butt-end of comedy.

Throughout the show’s seasons, there is a consistent theme of homophobia mixing with toxic masculinity which we all know is a dangerous cocktail. Having Chandler’s father Charles be a beautiful drag queen could have allowed the show to embrace different gender identities and expressions. The writers instead chose to have other characters poke at the fact that Chandler’s father is a drag queen and is probably a gay or bisexual person. Chandler’s own internal homophobia radiates after learning about his father because he fears that people will now think he is gay, which makes absolutely no sense at all.

They also take cheap shots at Ross’ ex-wife who is lesbian while Ross is thrown into a head spin after seeing his son playing with a Barbie doll. The possibility of the fact that maybe Ben just wants to play with a Barbie doll is so abhorrent to Ross that he conjures the idea that it is the fault of his lesbian ex-wife and her partner, which again, makes no sense at all.

The problems don’t stop there but I really wish they did. On top of the explicit homophobia and transphobia, the cast is completely white. Like, not one of the main characters is of colour. In fact, there are only two notable non-white characters on the show, one being Ross’ girlfriend Julie and Dr Charlie. This is highly damaging as not only does it prevent non-white people from seeing themselves in the show, but it also perpetuates the notion that the world is white focused.

Saying that Friends was just a product of its time is incredibly problematic as most of our generation and the one above us religiously watched Friends and so these dominant themes and ideas are woven into the fabric of our already ignorant society. Having such a popular show be filled with so many insensitive and damaging themes and jokes is not going to cut it anymore. It is 2020, maybe it is time to leave Friends in 2004.

by Ky Stewart

Understanding Your Privilege

The word ‘privilege’ has become the buzzword of 2020 and so it should. It is a word that everyone, especially those in dominant groups, should come to properly understand. Privilege has been at play for centuries and has been systematically institutionalised in every aspect of our society. People should understand how the privilege they might have, whether they like it or not, has disadvantaged others.

I’m sure you have seen Instagram has turned into an online protesting platform. From the controversial black tile to the endless cycle of Instagram stories spreading awareness and links for various different causes relating to BLM or other humanitarian crises.

This movement is spreading desperately needed awareness of the constant injustices faced by disadvantaged groups. It is a way for our society to recognise what is happening and what has happened. It is a way to voice our anger and fight for a united end to racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, classism, ableism and everything else that has pushed people down.

What has emerged out of this movement is the discussion about privilege.

As a white passing Indigenous man, I exhibit a set of privileges my non-white Indigenous brothers and sisters do not get to have. This is something that I have had to realise and learn about. For example, I can talk about Indigenous issues freely and be given a platform and people will be more inclined to listen, but my friends cannot do the same just because they have a different colour skin.

As white people, it is easy to ignore the vast issues in societies or not completely understand why people are protesting for their human rights. This is probably one of the more dangerous privileges, because you are able to ignore something that is killing others simply because it doesn’t affect you.

I have had many discussions and heated arguments with people who have told me that they haven’t had it easy and that saying that all white people benefit from privilege is unfair because not everyone is racist. Which shows to me that they probably don’t understand what privilege is.

Having privilege doesn’t mean that you are racist. Having privilege doesn’t make you a bad person. It doesn’t mean you aren’t allowed to help fight against racism, it just means that you need to understand that there are systems in place that will ultimately benefit you and not others.

Reading a book doesn’t equate to an immediate understanding of racism and privilege, but it is a good place to start. Listen to the stories being told by non-white people about their experiences. Start researching and unlearning what has been told to you in your education that comes from a biased Anglo point of view. Get involved in politics and stop using the excuse that you are not interested, or you don’t understand. Because other people don’t get the choice to be disinterested in politics when it encroaches on their lives.

What we need is for people to stop and think about how they might be able to get an education, walk down the street without fear, or feel safe with police presence. Having privilege allows for you to support movements like BLM and use it to break racist systems.

In the end, please just be kind and love everyone. Fight in the face of injustice and wash your hands.

by Ky Stewart

Symbols in Aboriginal Art

I am a person of Wiradjuri descent from my mother’s side and have been taught artistic styles from my Aunties and Uncles who are both Elders and experienced artists. I also have cultural connections to the Ngardi people from East Arnhem Land and the Darkinjung people from the Central Coast.

These symbols that I am sharing with you are specific to my own cultural upbringing and understandings. Many of these symbols can be found within other language groups’ artistic styles, but they can have slight variations or meanings depending on their cultural histories and Dreaming stories. I ask that if you see similar symbols in other Aboriginal artist’s work, be mindful of their cultural connections and think about the contextual meaning of the artwork that may influence the visuals and meanings of certain symbols.

Sitting Person

A very common symbol for most Aboriginal language groups which depicts a bird’s-eye view of a person sitting down. This symbol can sometimes be seen with lines next to them which represent spears. In some language groups the amount of ‘spears’ depicts the sitting person’s gender (e.g. 1 = man, 2 = woman). It is also common to see body art on these symbols which are very specific to the artist’s cultural connections, and the meaning behind the painting.

Path / Flowing River

This symbol also has a different meaning and look depending on the artist’s connections and context. I personally use this symbol to represent ‘journey paths’ from ‘campfire’ to ‘campfire,’ and to express stories of travel, growth, and learning.

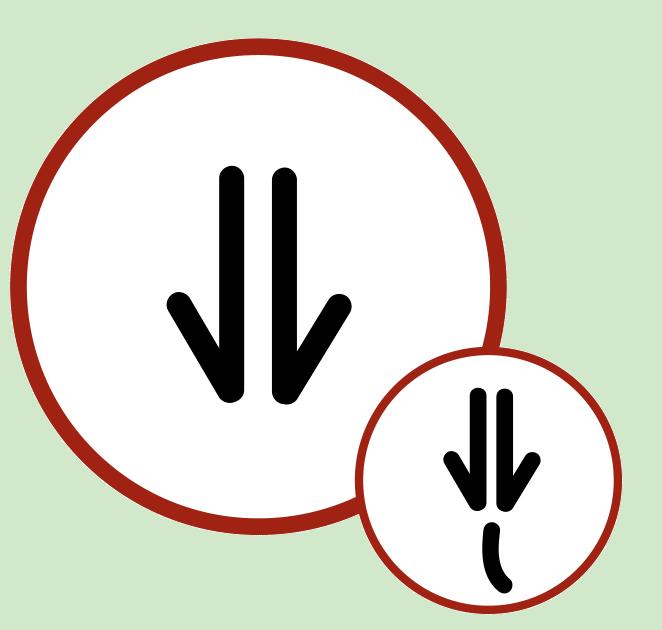

This symbol depicts the three-toed footprint of the Emu and is a fairly common symbol around Australia. Emus were a vital food source for Aboriginal peoples and their entire bodies would be utilised. Their bones were used for tools and weapons, their skin for leather, feathers for ceremonial practices, and fat for bush medicines.

Kangaroo Footprint

This symbol is also very common around Australia and can sometimes be seen with a line under the footprints to represent the Kangaroo’s tail. Kangaroos are a common food source due to their high meat and fat content, their bones and skin were used for tools, weapons, and carrying pouches.

Coolamon

The coolamon is a common tool for Aboriginal women that was used to hold and transport water, bushfoods, and sometimes to cradle babies. This symbol is mostly seen next to the ‘sitting person’ symbol to signify that the person is a woman.

Campfire / Waterhole

This symbol represents either a campfire or a waterhole, depending on the artist’s cultural connections, and the contextual meaning of the artwork. Many artists surround these symbols with ‘sitting people’ to represent community, family or people who are closely connected. I personally use this symbol to represent ‘community’ and the unification of peoples who are connected spiritually or emotionally.

Darug Country

Each issue Grapeshot uses the ‘You Are Here’ segment to shine a light on the quirks and foibles of a particular suburb. In this special First Nations’ edition of the magazine we wanted to learn more about the traditional custodians of the land on which Macquarie University is built.

Merrilee McNaught, a Darug Elder living in the Hornsby Shire, answers our questions.

In its Acknowledgement of Country, Macquarie University pays respects to the Wattamattagal clan of the Darug nation. What does it mean to you to hear an acknowledgement country?

It depends on the context. Sometimes it’s respectful, but sometimes it’s just tokenism, and tokenism doesn’t have any substance. The people who are saying it are doing it for show and have no idea of what they are actually acknowledging. But, when it’s done properly and with respect then I really appreciate it and it moves me greatly. Unfortunately, it’s now seen as something that has to be done, and it’s lost its value.

Do you identify as belonging to a specific clan or language group from the Darug nation?

Because I’m a part of the Stolen Generation, I was not brought up in Aboriginal tradition. I know I am Darug, I can trace my ancestry back to Maria, who was the original Elder, mentioned in Governor Macquarie’s letters and in a lot of the early teachings. She did some amazing things if you investigate Maria. She was my great- great-great-great-great-grandmother but I don’t identify as a particular clan because Darug nation was split into many-many-many parts in the Stolen Generation.

The Maria referred to here is Maria Lock, daughter of Yarramundi, known to Europeans as ‘Chief of the Richmond Tribes,’ he belonged to the Boonooberongal clan of the Darug people. Alongside her father and clan, Maria was present during the first meeting between Governor Macquarie and the Aboriginal peoples of the Cumberland Plain in Parramatta on December 28th 1814. She was the first student of the Native Institution, which Governor Macquarie established with the aim of educating, christianising, and assimilating Aboriginal children into colonial society. The foundation of this institute facilitated the first government policies that led to the Stolen Generations.

How do you stay connected to your Indigenous heritage?

Through Facebook mainly, and through research, and through keeping in contact with people who are of my family, the Lock-Webbs.

In Annette Salt’s book Still Standing you mention your desire to teach Aboriginal stories and songs to your children. Which stories and songs did you choose to pass on to them and why?

By the time Annette contacted me my children were both married and had their own children. So I never had the opportunity to do that but I always had Aboriginal stories in the bookcase and I still use Aboriginal tales when I’m teaching younger children at school and I teach them some of the songs in the Darug language that they relate to like ‘Kookaburra sits in the old gum tree,’ which has been translated into Darug and a few other folksongy things where they know the tune and we put it into Darug. I also have a couple of Pitjantjatjara songs that the kids like singing.

Growing up how did you discover these stories and songs?

Research. I’m an educator and I’m very good at research and sourcing out things—there was a book in the Penrith library which was written as The History of the Darug Nation and it’s still available in the Hornsby library and every library in the State. And the acknowledgement by the Department of Education of my clear Aboriginal heritage did help me in establishing the fact that I could talk to other Aboriginal teachers, plus I was in the (NSW) Teachers Federation as a councillor and I met a lot of Aboriginal people who were involved with the Federation.

In Salt’s interview, you mention that you were taught a historical narrative that excluded Aboriginal people, that you were brought up in a very “white world.” As an educator, and with the experiences of your children, do you see a shift in this depiction of history?

I have seen a distinct shift since the Aboriginal consultations in the late 1980s where Aboriginal teachers were brought together to talk to teachers about incorporating Aboriginal influences in their consultation, in their teaching with the older children, and with the younger children. We have to have an Aboriginal perspective in everything. It also made the other teachers aware that they could still learn something about their own heritage. Let’s face it, not many teachers are of Australian heritage. There are people from all over the world, thankfully, we have such a wide variety of ethnicities within the Department of Education and every one of them brings a unique perspective on their cultural heritage but most of them are really keen to learn about their new country, the origins of people in this new country, and people will ask questions, they really-really want to know. Teachers in particular want to know and they’ll come to me and say “how can I put an Aboriginal perspective into this?” There are a lot of materials put out by the Department of Education, and publishers now, which also give an Aboriginal perspective on many topics.

Were the experiences of you and your sister different due to your differing appearances? Were you treated differently?

She was very dark and she always claimed Italian heritage if anyone asked her. I was very fair, no one asked me about Aboriginal heritage. So I was given a lot more freedom I guess to be myself and to grow whereas she tended to be judged a little because of her dark colouring and dark hair.

Are there places that have a special significance to you in Darug country?

I know when I’m on Darug country. The land I walk on tells me and I can tell when I walk into another country and I don’t know how to explain that but the Darug land has a particular feel to it under your feet. It’s just Darug country. Most of the country that my people came from is the lower Blue Mountains, Penrith, St Marys. In fact, quite a few of my relatives live there still. There is a feeling, as an Aboriginal, you do know your own country. There’s no special place but when you’re not there you know you’re not home. It’s not a house, it’s not an area, it’s a feeling that: this is my country.

Do you speak the language (or alternatively languages) of the Darug nation?

They have managed to recapture a lot of the language but it’s very rarely spoken because most of my generation and the next two generations are the stolen people. My children had no interaction with other Darug children, not that I didn’t want to but that we were scattered so far and it’s very hard to get back together.

There is an interesting thing though, I’m acknowledged by other Aboriginal people without having to say “I’m Aboriginal.” I was on a train one day and these Aboriginal women were fighting. There were a couple of other people who said “come on, let’s get out of here,” and I just looked at them and said, “they’re not hurting anyone.” They turned around and said “thanks cuz.”

Aboriginals are not a unique tribe, they are people, who happen to have a particular heritage just like everybody else has a unique heritage that is unique to you... I think you need to acknowledge that Aboriginal heritage is unique. That we are blessed to be Aboriginal people. To live in a land that is so blessed and originally they talked about our country, our Australia, as if it was the Garden of Eden because it is such a blessed country—forget about bushfires and droughts, we won’t mention those— but you need to realise that we are normal people. There are high court judges who are Aboriginal, we have a lot of footballers, unfortunately, most of them my cousins, we have a lot of people who are lawyers, we have a lot of teachers… We are all just people who are still striving to achieve in a strange world. It’s not our land, it’s not our country but it’s where we belong and when you talk about Aboriginal people you need to acknowledge that we are unique, as you are unique, and that our heritage is of the country just as your original heritage is to the country of your ancestors and respect the fact that we do love our country probably a little bit more than you, just a little.

by Avni Bharadwaj and Jodie Ramodien

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

When I was little, my mum would send me into the kitchen to make her a cuppa. One tea bag, with milk, 5 sugars (shocking, I know). She loved the Chocolate Royal biscuits, and Cadbury Furry Friends. And sometimes on payday, she would let us get Maccas. Devon sandwiches were a regular on the menu, and her curried sausages were the best in the world.

Growing up, my mum taught me many things. She taught me to always be proud of being Aboriginal, something that she wasn’t always allowed to be. She taught me to be resilient, to stand up for myself, and stand up for others who may not always have a voice. She taught me how to navigate the world. She embodied a staunch warrior, who no one could ever stand over (even though she was barely 5 foot tall).

My mum was a storyteller. Growing up, she was always sharing stories. Sometimes happy stories, but many were overwhelmingly sad stories. She told us about how she used to steal lettuce leaves from the garden, and fill them with sugar and eat them with her brother. She told us about the swimming holes she got to spend the summer in, and how there was bush for miles around her home.

My mum was stolen from her family when she was eight-years-old, in 1966. She was taken around 500km away from her home, and eventually to Bidura girls home on Glebe Point Road. She was separated from her 5 siblings. This was the catalyst for a range of trauma in her life, all stemming from forced government removal. Despite the anguish, abuse and trauma she experienced from being stolen, she is the strongest person I’ve ever known. She raised 5 kids, all on Darug Country in Western Sydney. She never missed a school event, or a parent teacher night, and did her best to make sure we never went to bed hungry. She surrounded us with love in all that she did.

My mum passed away suddenly from complications relating to her emphysema in August 2018, aged only 60. She had smoked cigarettes since childhood. Some old people say we hold our trauma in our chests, and smoking can help ease the trauma we carry there. My mum is walking with the ancestors now. I carry her spirit in everything I do, and hope everything I do would make her proud.

by Tamika Worrell