10 minute read

BETTER WITH AGE

WARRIOR

Fearless nonconformists blazing new pathways and challenging industry norms.

The Experience Music Project (now the Museum of Pop Culture) in Seattle was founded by Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen and designed by Frank Gehry.

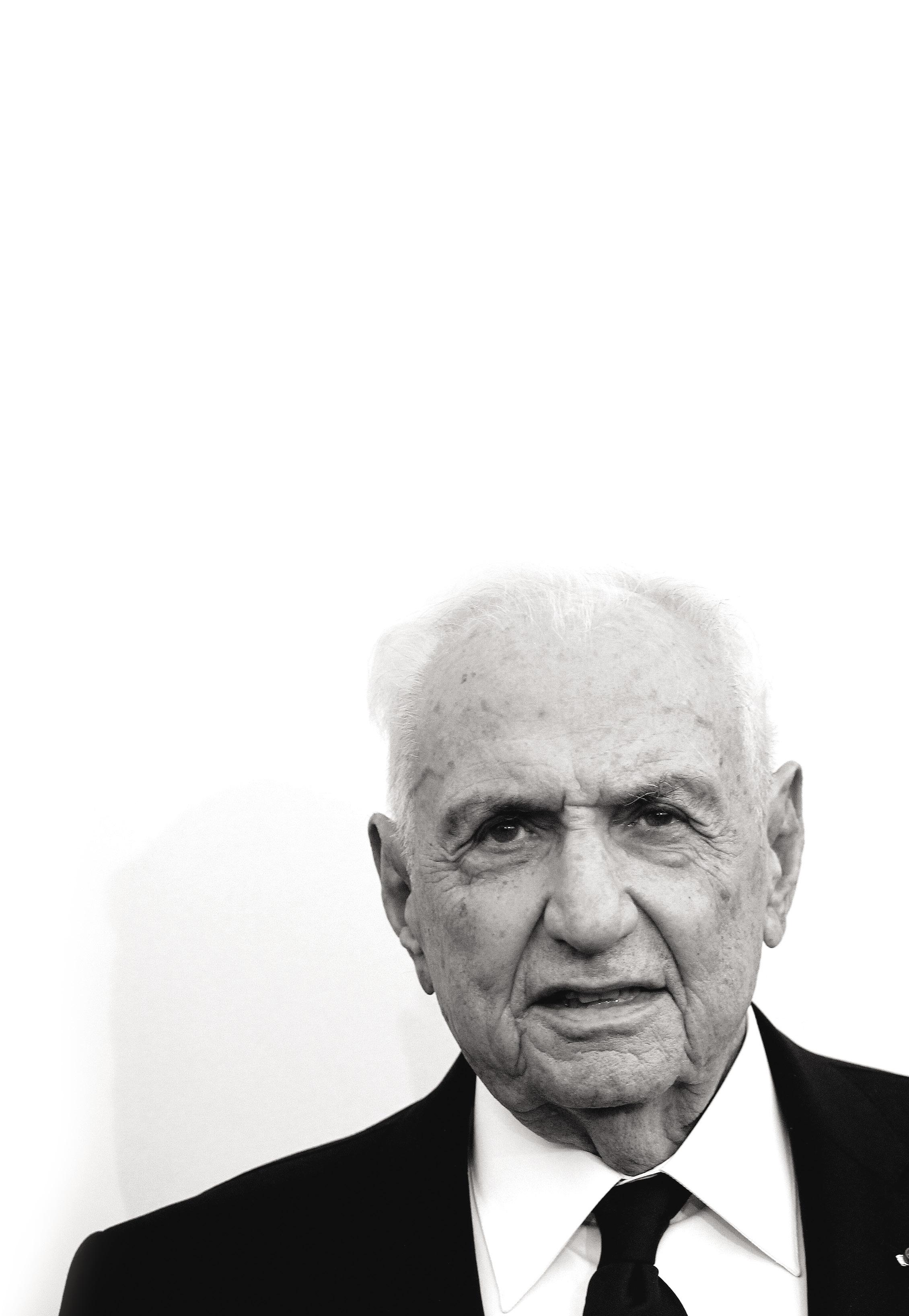

THIS PAGE: Designed to look like a smashed guitar, the Museum of Pop Culture (MoPOP) is one of Gehry’s most controversial buildings. OPPOSITE: Architect Frank Gehry in 2015.

BETTER WITH AGE

At 92, renegade architect Frank Gehry is turning to social-justice-focused projects and staying busier than ever.

By Rachel Gallaher

“FRANK IS AN UNSTOPPABLE MAN, A TRUE VISIONARY. THESE IDEAS THAT HE WAS TELLING ME, AND NOW I EXACTLY AS HE SAW IT IN HIS HEAD BACK THEN. THE

EVERY INCH OF THIS BUILDING.” —GUSTAVO DUDAMEL, LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC

WHEN WE FIRST CAME TO THE SPACE, HE HAD ALL STAND IN THE SPACE, AND I SEE THAT EVERYTHING IS GENIUS AND GENEROSITY OF FRANK RUNS THROUGH

One of Gehry’s most famous designs, the Walt Disney Concert Hall is home to the Los Angeles Philharmonic. The exterior comprises more than 12,000 steel panels, no two of which are exactly alike.

It’s a well-known bit of architecture lore: A young Frank Gehry sits on his grandparents’ kitchen floor, building complex cities out of wood scraps, with his grandmother Leah Caplan helping to organize and design the miniature infrastructure. Those irregularly shaped blocks—purchased by Caplan by the burlap sackful at a woodshop down the street from her

Toronto home—and encouragement from his family provided the original impetus for some of the world’s most beloved, and polarizing, buildings of the past 100 years. According to the 2015 biography Building Art: The

Life and Work of Frank Gehry, by

Paul Goldberger, when Gehry first considered a career in architecture, he often recalled those times on the kitchen floor, describing them as

“the most fun I ever had in my life.

I realized it was a license to play.”

In a sense, Frank Gehry is still playing with blocks. Though they are larger and more expensive these days, the joy of creation they provide hasn’t diminished over the past eight decades. At the end of June, a 27-acre multidisciplinary art and cultural campus commissioned by the LUMA Foundation (a nonprofit arts organization focused on independent, contemporary artists) opened at the Parc des Ateliers in

Arles, France. Rising from the center of the site is a twisting, geometric,

Gehry-designed tower finished with 11,000 stainless-steel panels that look like metallic LEGOs. The faceted exterior is punctuated by protruding windows, and, according to the architect, was inspired by

Vincent van Gogh’s famous Starry

Night painting (which he completed nearby in 1889), while the cylindrical glass base from which it rises takes its cue from Arles’ Roman Empire–era amphitheater. The structure is an architectural power move, and clashing opinions of it emerged online and via social media as soon as the renderings were released.

It’s a very Gehry creation, with its look-at-me façade, eye-popping angles, and use of art as inspiration. It’s easy to feel a sense of wonder when taking in the tower, which engages the imagination as it taps into a youthful spirit of creativity often lost as we age. This embrace of emotion and enthusiasm—the permission to have fun while designing, and to not take oneself, or the process, too seriously—imbues Gehry’s work with intangible qualities that create surprise and delight as they propel his designs into icon territory.

“The sense of play is inherent in all of us,” Gehry says. “It’s how you learn as a child, and it’s been proven that play is pivotal in the development of our brains. For me, that sense of play is about curiosity and about listening. I used to talk about it like the cat with the ball of twine— [the idea of] following the ball as it unravels without expectation of where it will take you. With design, I always start with the functional aspects of the building. I spend a lot of time making sure the areas are precise and the relationships of the rooms are functional and that we have respected the zoning codes and the client’s budget. Being rigorous in the early stages frees you up to play in the later stages. It’s an important balance between the two.”

Known for his visionary work (his design for the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in Bilbao, Spain, which opened in 1997, is credited with shifting the entire approach to the architecture of museums), the Pritzker Prize–winning Gehry, who credits art and artists as an overarching influence, has pushed the architectural canon more than any other living architect. His portfolio of hundreds of projects includes an innovative line of cardboard furniture, museums on nearly every continent, the exemplary Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, and »

“IT IS IMPORTANT FOR EVERYONE WHO HAS ACCESS AND INFLUENCE TO USE THEIR POSITION TO CREATE MORE OPPORTUNITY AND A BETTER SOCIETY FOR

ALL.” —FRANK GEHRY, GEHRY PARTNERS

Gehry’s design for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, was a groundbreaking achievement in modern architecture. The museum is an international draw for tourists, who come not just to view its art collections, but to see Gehry’s remarkable achievement.

FROM LEFT: A hidden stairwell along an exterior wall of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles; the undulating exterior of Seattle’s MoPOP; the Gehry-designed tower on the LUMA Foundation campus in Arles, France, is covered in 11,000 stainless-steel panels and punctuated by protruding windows. »

“WITH DESIGN, I ALWAYS START WITH THE FUNCTIONAL ASPECTS OF THE BUILDING. I SPEND A LOT OF TIME MAKING SURE THE AREAS ARE PRECISE AND THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE ROOMS ARE FUNCTIONAL AND THAT WE HAVE RESPECTED THE ZONING CODES AND THE CLIENT’S BUDGET. BEING RIGOROUS IN THE EARLY STAGES FREES YOU UP TO PLAY IN THE LATER STAGES.” —FRANK GEHRY, GEHRY PARTNERS

ABOVE: The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. BELOW: Gehry’s Der Neue Zollhof complex in Düsseldorf, Germany, comprises three buildings with punched window openings on the exterior façades.

his own Santa Monica residence, built in 1978 using an assemblage of glass, plywood, corrugated metal, and chain-link fencing to encase an old Dutch Colonial. It was an experiment in humble materials that started the early-career architect on his ascent to global acclaim.

Like many labeled “genius,” Gehry has seen his share of controversy. After he designed the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, a phenomenon dubbed “the Bilbao Effect” entered the design lexicon. The idea suggested that cultural investment coupled with radical architecture would help uplift cities both culturally and economically. Suddenly, the great race to hire Gehry and other “starchitects” to design institutions was on. But there’s a fine line between uplifting communities through infrastructure and gentrifying the areas in which vulnerable populations live. A New York Times article published in April 2021 notes public concern over Gehry’s involvement with the River Project— a current effort, funded by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works, to revitalize a 51-mile stretch of channel that was paved over in 1938 to prevent flooding— citing fears that a gentrifying effect could drive out the very people the project claims to serve.

Gehry has tried to assuage these fears, and his track record of nonprofit involvement, attention to social-justice projects, community engagement, and interest in youth arts programming contradicts notions of the architect as a heartless gentrifier or greedy developer. Earlier this year, Gehry joined the board of the Herbie Hancock Institute of Jazz (a nonprofit education organization that offers talented young musicians college-level training from acclaimed jazz masters), and he is currently designing housing for homeless veterans in LA. The Gehry-designed Children’s Institute, a center in LA’s Watts neighborhood

Gehry’s first project in Europe was the Vitra Design Museum and factory, completed in 1989.

that focuses on helping children and families who have experienced trauma, is slated to open in the near future. And six years ago, Gehry and activist Malissa Feruzzi Shriver founded Turnaround Arts: California, a branch of the national Turnaround Arts program started by former First Lady Michelle Obama in 2011. The nonprofit brings arts education to the state’s neediest schools.

“All of my architectural life, I have spent time in elementary schools that are suffering,” Gehry says. “I have volunteered over the years to go into classrooms to try to energize kids through art.”

One of Gehry’s latest undertakings, which aligns with his passion for encouraging the artistic pursuits of the next generation of creatives, is the Judith and Thomas L. Beckmen Youth Orchestra Los Angeles (YOLA) Center. Set to open on August 15, the adaptive-reuse project will house the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s youth-focused educational arm. Gehry was brought on to transform an existing 18,000-square-foot former bank building into a 25,000square-foot facility that will expand the existing YOLA program to serve up to an additional 500 students annually from the surrounding community. It was also an opportunity for him to collaborate with the LA Phil’s music and artistic director, Gustavo Dudamel, once again. The pair previously collaborated in 2012, when the architect designed the sets for the LA Phil’s production of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Don Giovanni opera, and Gehry considers Dudamel a close friend.

“It’s been a joy for me to work with Gustavo to create a place where young people can learn and express themselves through music,” Gehry says. “I know how important it is to create a place where students feel comfortable, secure, and welcomed. That was one of the keys to this project. The other was to design a center that gives young people a world-class instrument. We’ve made a space that has the same stage dimensions as the Walt Disney Concert Hall, because that’s what these kids deserve.” »

“This is the realization of a beautiful dream that started 12 years ago: to create this space for young people to have access to beauty,” Dudamel adds. “It came from an idea that was born many years before in Venezuela, when maestro José Antonio Abreu created [the music education program] El Sistema with the belief that music should be an essential tool for social change in society. To me, this is a place of inspiration, transformation, and beauty. This building is truly a physical manifestation of our mission to change young peoples’ lives through music.”

Though more subdued and straightforward than some of Gehry’s work (no sweeping curves or experimental forms), the space is no less inspired. And neither is Gehry, whose firm is currently at work on projects in LA, Paris, Toronto, Cabo San Lucas, Berlin, and Taichung, Taiwan. “I love my work and the clients that I am working with,” he says. “The most valuable lesson: Don’t give up.”

And as for those kids with big dreams and artistic drives? Gehry is passing along the mantle of compassion and creativity, optimistic that his interests and values will live on, and not just through the buildings he’s designed.

“I hope that [the next generation of architects and designers] puts themselves into their work passionately and does their best on every project, no matter the size,” he says. “I hope that they learn all aspects of the craft of architecture relentlessly and diligently before seeking publicity. I hope that they do not succumb to the forces trying to dumb down and minimize the profession. I hope that every day, they try to bring art back to the profession, and I hope that they use their talents to make the world a better place for more people, in whatever way they can.” h

The Judith and Thomas L. Beckmen YOLA Center, Inglewood, California.

© FRANK O. GEHRY; PHOTO: JOSHUA WHITE, COURTESY GAGOSIAN FRANK GEHRY, Fish on Fire (Los Angeles I), 2021. Copper, stainless-steel wire, and LED lights, 43 x 24 x 24 inches, 109.2 x 61 x 61 cm.