2: Business: Disrupted Markets

Introduction

The annual Birmingham Economic Review is produced by the University of Birmingham’s City REDI and the Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce. It is an in depth exploration of the economy of England’s second city and a high quality resource for informing research, policy and investment decisions.

This year’s report provides comprehensive analysis and expert commentary on the state of the city’s economy as it emerges from disruption caused by the pandemic into a new period of high inflation and uncertainty. The Birmingham Economic Review assesses the resilience of the city, its businesses and its people to the set of challenges stemming from the UK’s vote to leave the EU, the coronavirus pandemic and now the energy crisis. It includes an update on the development of the region’s infrastructure and highlights opportunities for growth, building on existing strengths and assets.

The most recently available datasets as of 30th September 2022 have been used. In many circumstances there is a significant lag between available data and the current period. Contributions from experts in academia, business and policy have been included to provide timely insight into the status of the Greater Birmingham economy.

Report Geography

The report focuses on the ‘Greater Birmingham city region’ defined by the boundaries of the Greater Birmingham and Solihull Local Enterprise Partnership (GBS LEP). The GBS LEP area consists of the following local authorities: Birmingham, Solihull, Bromsgrove, Cannock Chase, East Staffordshire, Lichfield, Redditch, Tamworth, Wyre Forest.

References to the ‘West Midlands region’, or ‘West Midlands (ITL1)’, are to the large scale region at International Territorial Level 1 (ITL1). There are nine ITL1 regions in England: North East, North West, Yorkshire & The Humber, East Midlands, West Midlands, East of England, London, South East and South West in addition to Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. Note that ITL recently replaced the EU’s Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics (NUTS). Geographies of ITL and NUTS territories generally correspond except for minor differences at local authority level outside the Midlands.

References to the ‘West Midlands metropolitan area’ are to the West Midlands county comprising seven metropolitan districts (WM 7M): Birmingham, Solihull, Coventry and Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall, Wolverhampton.

References to the ‘West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) area’ are to that administered by the Combined Authority.

Note that figures may not always total exactly due to rounding differences. Figures in some tables may be undisclosed due to statistical or confidentiality reasons.

Foreword and Welcome

Chapter 1. Economy: Crises and Resilience

Chapter 2. Business: Disrupted Markets

Chapter 3. People: Challenging Times

Chapter 4. Place: Connecting Sustainable Communities

Chapter 5. Opportunity: Building on Strengths

Business: Disrupted Markets

Recent years have proven difficult for businesses across the region. The pandemic posed a greater challenge for many sectors than any time since the Second World War, although governmental support successfully staved off a wave of failures whilst digitalisation allowed many firms to operate remotely. Whilst the economy has largely recovered from the direct hit brought on by the pandemic, supply chain issues, staff shortages and inflation all continue to pose challenges. Not least the energy crisis which is placing many firms under strain and raising the threat of failure once again. Meanwhile, traders have been adjusting to new post Brexit trading arrangements with the European Union following the UK’s formal departure in 2020.

Businesses are the lifeblood of the regional economy and have a critical role to play in delivering regional growth and levelling up aims. They are essential drivers of growth, investment, jobs, productivity and innovation necessary for progress across economic, social and environmental domains. Future prosperity is intrinsically linked to the performance of the many small, medium and large businesses and entrepreneurs across the region. They are also a major source of tax revenues necessary to fund investment in better public services, infrastructure and the transition to net zero. Achievement of these objectives becomes much harder without a strong and dynamic business base.

This chapter provides an update on the state of the region’s business base, including trading conditions, financial distress, investment and innovation activity.

Business Demography

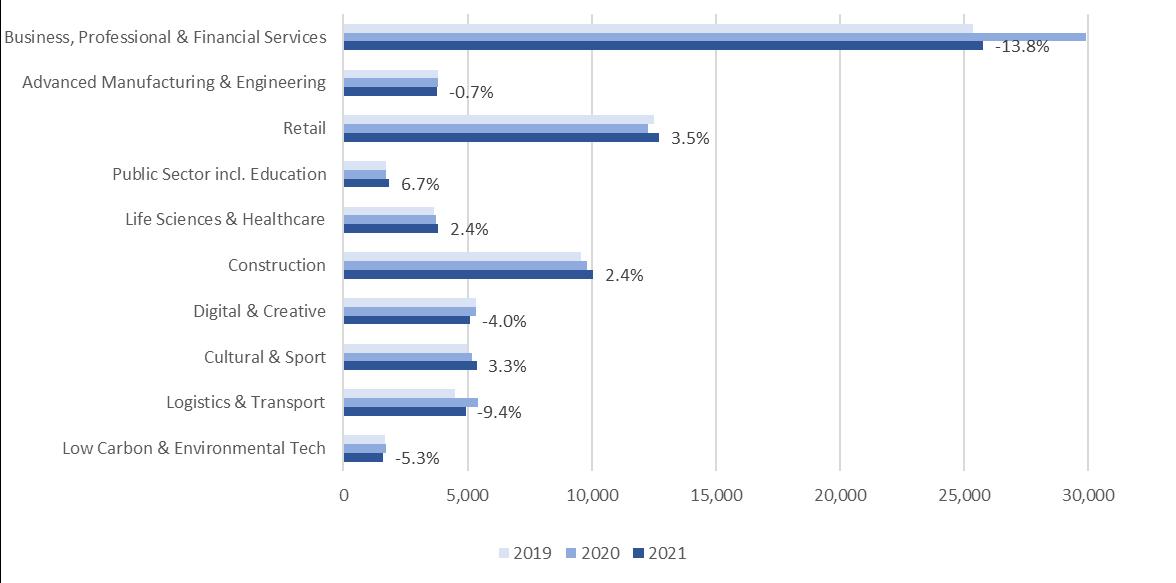

As of 2021 there were 75,005 enterprises registered in the Greater Birmingham region. More than a third (34%) were in the Business, Professional and Financial Services sector, with a further 17% in Retail and 13% in Construction.

The count fell by 5% from 2020 when there were 78,925 enterprises in the city region. The year over year change is entirely accounted for by an unexplained 13.8% fall in the number of enterprises in the Business, Professional and Financial Services sector. However, this looks to be an anomaly within the ONS data and the overall count remains 2.5% above that in 2019.

There were year over year increases in the number of enterprises in Public Sector and Education (+6.7%), Retail (+3.5%) which reversed the decline seen in 2020, Life Sciences & Healthcare (+2.4%), Construction (+2.4%) and Cultural & Sport (+3.3%). The latter is notable given the high impact of the pandemic on the sector. Logistics & Transport fell back by 9.4% as the pandemic related boom subsided, although was still 9.2% higher than in 2019. Discouragingly, the number of enterprises in the Low Carbon & Environmental Tech sector declined by 5.3% and is below that in 2019.

Number of enterprises by sector (GBSLEP)

Nine in ten private businesses in the city region are micro sized (0 9 employees). It is these businesses that saw the greatest fall in number between 2020 and 2021. Only 290 businesses (0.4% of the total) are large in size (250+ employees). The number of large businesses has continued to grow year on year since at least 2016, although the share of the overall number has changed very little.

Survival Rates

Following several years of decline, business survival rates notably improved in 2020 despite the challenges presented by the pandemic.

ONS figures show that out of 17,665 businesses born in 2019, 92% remained active in 2020. This is the highest one year survival rate since the cohort born in 2016. Two year survival rates improved for businesses born in 2018, with 66% still active in 2020. This was a markedly better rate than for those born in the previous year (51%).

The extensive range of Covid 19 related business support measures introduced in 2020 was instrumental in helping businesses through the health and economic crisis. Despite this, the long term trend for business survival rates remains downwards.

Business survival rates (GBSLEP)

Sector level detail is only available at the national level. It indicates that businesses in the Property and Finance and Insurance sectors may have struggled to survive during 2020 whilst those in Education and Health fared better.

Business lending

Rapid growth in lending to small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) occurred during 2020 and early 2021. Though the pace of lending has since declined, it remains at a higher level than prior to the pandemic. Lending to large businesses also increased at the start of the pandemic, however the rate of growth has since remained relatively on the whole.

Annual growth of lending to private non financial businesses (UK)

The Bank of England has reported that, despite worsening economic conditions, debt servicing remains affordable for most UK businesses and that major banks have considerable capacity to support lending. However, businesses in sectors more exposed to non essential household goods or volatile energy prices, such as Transport or Manufacturing, are at higher risk of distress.1

Financial Distress

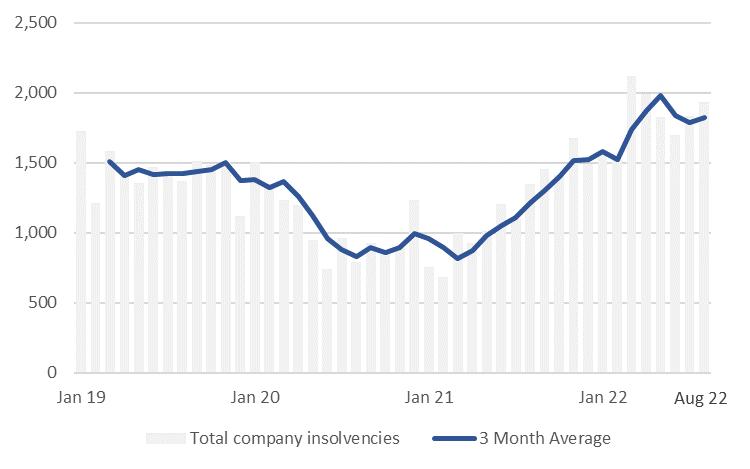

The number of company insolvencies across England and Wales remained relatively low during 2020 when Covid 19 loan schemes were introduced to support businesses through the pandemic. However, the number of insolvencies has steadily risen since Q1 2021, almost tripling between June 2020 (741) and March 2022 (2,119). There has been a slight decline in recent months but the number remained relatively high at 1,933 for the month of August 2022.

Company insolvencies (England & Wales)

The rise in insolvencies coincides with the unwinding of Covid 19 support schemes, including Bounce Back Loans and Business Interruption Loans, which closed in March 2021. Whilst they were replaced by the Recovery Loan Scheme, running between April 2021 and June 2022,

England, Financial

ongoing disruption in supply chains and customer markets combined with rising interest rates and energy prices has added to financial pressures.

Covid 19 support may also have allowed some businesses to continue trading that would otherwise have folded, under normal (i.e. non pandemic) trading conditions. These so called ‘zombie companies’, which are unable to pay down their debts, are vulnerable to collapse as the economy stutters and interest rates rise. Think tank Onward has estimated that one in five British businesses may be ‘zombies’. They also contribute to poor competitiveness and weak productivity.2

With the creation of a government department, on the back of the ‘levelling up’ election slogan, there has been the inevitable consequence for the delivery of local business support. In short, following the publication of the Levelling Up White Paper at the start of 2022 the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, in collaboration with the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial strategy, set out a framework for integrating Local Enterprise Partnerships into local democratic institutions. With the existence of the WMCA this means seeking to develop even closer relationships for the LEPs in the West Midlands.

What will this mean in practice for the West Midlands? Well, as might be expected, there will be a great deal of uncertainty while this integration process takes place as the important functions that LEPs have been responsible for in the last decade are integrated into the WMCA. These include, for example, Growth Hubs, International Trade and Local Digital Skills Partnerships and this uncertainty has led to challenges around funding and the continuation of ‘business as usual’ for the local economy. Budget allocations for 2022 23 have been pared back to an absolute minimum and this is hardly an environment for holding on to key delivery staff.

With the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF) now officially announced in April 2022, with investment plans submitted by early August 2022 for a three year funding period until March 2025, the WMCA has been awarded £88m with a clear emphasis on local business support as one of three key priorities. In anticipation of this funding package the WMCA had already instigated a review of business support in 2021 to try and get some strategic overview of the hundreds of individual initiatives and programmes currently running or winding down in the region, many of which are funded by the EU. The emphasis in that review, which involved all the LEPs in the region, was to develop a sense of what the priorities should be in terms of a group of intensive premium business support products to address the two themes of SME Competitiveness and Productivity and Research and Innovation. These premium products would sit alongside range of more self service mostly online generic ‘Core’ business support offerings for all businesses across the West Midlands region. So, with the framework outlined and the funding in place with the WMCA for business support it remains to be seen how the engagement with the private sector will develop given that it has been somewhat of a challenge in the last 12 years for a variety of reasons.

However, these ‘regional’ premium programmes must recognise the role of national schemes like Help to Grow: Management (H2GM) and Help to Grow: Digital, launched in 2021 and 2022 respectively, and then it remains to be seen how best UKSPF can operate as truly net additional business support funds. With local business schools delivering H2GM for BEIS and HMT it is important to ensure that these national schemes designed to deliver intensive support to thousands of SMEs in the West Midlands are integrated into any business support ecosystem developed locally.

If we are being optimistic, it will be well into 2023 before the LEP integration takes place and some sort of common strategy for the LEPs is driven by the WMCA and its Mayor. Meanwhile, the UKSPF investment plans gather momentum so this integration could not come at a worse time for the private sector and in particular SMEs across the region as they are confronted with a combination of the cost of doing business crisis, supply chain disruption, labour and skill shortages, downturn in international trade because of the Brexit deal, rampant inflation and a recession forecast for the end of 2022 and to last well into 2023. These businesses will need cash to survive these next 12 months and central government will once again be obliged to intervene as they did in March 2020 in response to the COVID 19 pandemic to deal with this national economic crisis.

In addition, in the wake of COP26, business was being urged to transition to green business models but many view these investments are seen as costly and not sitting well with their traditional business model and contradictory to business performance. Many are sympathetic but are unaware of the resources and tools to make it happen.

The last thing an SME business owner needs to be confronted with as they seek support to survive and grow is another round of re arranging the policy deckchairs in the context of a stagnating economy. As in Scotland and Northern Ireland, and to a lesser extent in Wales, over many decades, we need a highly visible and effective public policy framework of business support that is respected by the private sector. I am not sure we have ever had that in England and therein lies the problem as most SMEs are unaware of what business support organisations exist and the support that they offer. I am pessimistic that this will change anytime soon.

The UK economy is currently being buffeted by considerable economic headwinds caused principally by:

(1) the removal of government protections to business brought in during the pandemic and the threat of tax rises to pay for the increased government debt burden caused by it;

(2) inflationary pressures caused by supply chain disruption and rapid changes in consumer demand brought about by the pandemic;

(3) further inflationary pressures caused by energy price increases resulting from the ongoing war in Ukraine;

(4) these inflationary pressures in turn leading to increased interest rates and industrial disruption and the possibility of a wage price spiral.

The picture is further complicated by Brexit, the full consequences of which have yet to be mapped out.

This has led to negative predictions for the UK economy at least in the short term increasing the risk of corporate failure.

These trends are starting to be reflected in the insolvency figures. According to the monthly insolvency statistics produced by the Insolvency Service, the number of registered company insolvencies in June 2022 was 1,691, which was 40% higher than in June 2021 and 15% higher than the pre pandemic number in June 2019. This increase was principally made up of a very large increase in the number of creditors’ voluntary liquidations (“CVL”), which is a “funeral” process for a company instigated by its management. Indeed, the restructuring procedure numbers (where the company or at least its business survives) for June 2022 were still down on the pre pandemic numbers for June 2019 (though administrations were up as against June 2021 figures).

We would caution however reading too much into these figures as economic augurs: the sudden increase in CVLs is to be expected as formal insolvencies were kept artificially low during the pandemic through government intervention and the sudden increase may represent a transient post pandemic correction. Meanwhile the reduction in the number of companies using restructuring procedures may be caused by a multiplicity of factors including the expense of the administration procedure rendering it unattractive as against a CVL, HMRC’s becoming a preferential creditor, again rendering company voluntary arrangements less attractive, the prohibitive expense of the new restructuring plan procedure (albeit it has recently been used by the SME Houst) and the perceived defects of the new moratorium procedure.

Setting aside the raw statistics for the moment, it seems clear that the headwinds will result in an increase in the use of formal insolvency procedures in the short term. Furthermore, the headwinds described above could potentially have a greater impact in the Birmingham and wider West Midlands region than in other regions given that supply chain disruption and inflationary pressures (particularly from cost push factors such as energy price increases) may take their greatest toll on construction and manufacturing, key sectors in Birmingham and the West Midlands.

This is starting to be reflected in some of the data. Office for National Statistics data showed more than 137,000 British businesses closed in the first quarter of 2022, which was a 23% increase on the first quarter of 2021, but this data showed considerable regional disparity with West Midlands business closures being more than double those for London. Insolvency Service data in relation to formal insolvencies is more difficult to parse for regional differences since it is not broken down by region, however, and slightly against the view that the Midlands may be more affected by the current headwinds than other regions, is the fact that analysis of Gazette

notices conducted by Interpath Advisory shows that the trend in administrations in the Midlands is in fact slightly more positive than the UK as a whole, the Midlands showing an increase in administrations of 39% in the first half of 2022 as against a 44% increase for the UK as a whole. Again, this statistic needs to be treated with some caution as an augur of economic health: administration is a restructuring not funeral procedure and an increase in number does not necessarily connote to broader economic malaise.

Predicting macroeconomic trends is notoriously a dismal science but it appears clear that the short term will be rocky for many businesses, whether in Birmingham or the wider UK, and particularly for the construction and manufacturing sectors given their greater exposure to supply chain disruption and inflationary pressures.

Business Confidence

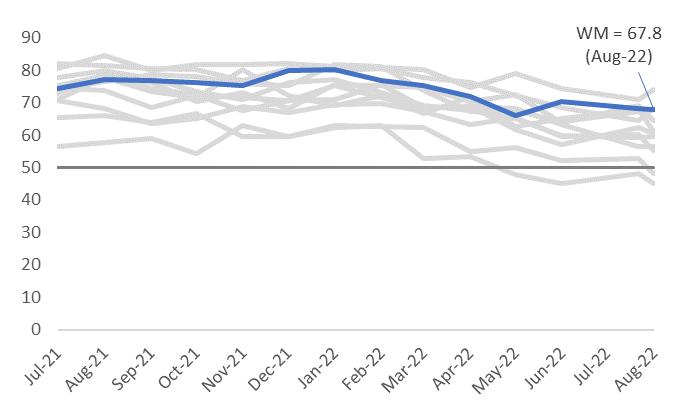

Despite strong headwinds, businesses in many regions remain optimistic about the future, although there has been a softening in outlook since the start of the year. Business leaders in the West Midlands are more optimistic than in most other regions. NatWest’s Future Activity Index posted a reading for 67.8 for the region in August, higher than all other regions except Yorkshire & Humber (74.0), South East (68.3) and London (68.0). The reading has fallen from a recent high of 80.3 at the start of the year.

West Midlands Future Activity Index

Source:Natwest,RegionalPMI FutureActivityIndexBusiness Investment

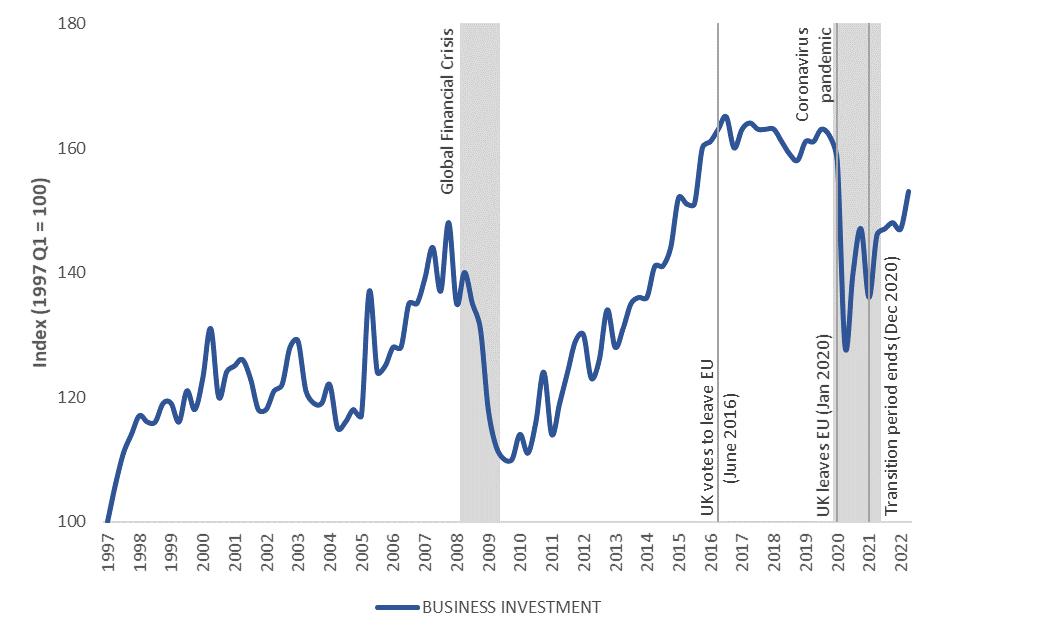

UK business investment has suffered considerably since the onset of the pandemic, with activity falling to levels last seen in 2011. Although recovery looks to be underway, investment in the Q2 2022 was still 6% below the final quarter of 2019.

Weak business investment, both in capital and research and development, is one of the major contributors to poor UK productivity. [Oliveira Cunha et al. Business time: How ready are UK firms for the decisive decade? (2021) Centre for Economic Performance & Resolution Foundation] There has been a notable lack of growth in business investment since Q3 2016, following the Brexit referendum.

Business investment (UK)

Innovation

Innovation, which is the development, commercialisation and adoption of new products, processes and services, is essential to address the UK’s productivity and wider societal challenges. It has garnered much attention in recent years through the Innovation Strategy, Levelling Up White Paper and stated intentions to make the UK a science superpower on the world stage.

As reported in last year’s Birmingham Economic Review, UK spending on R&D lags many other industrialised nations. The OECD average for total spending, including public and private sources, on R&D was 2.5% of GDP in 2019 having risen steadily throughout the course of the 21st Century. Some nations, including Germany and the USA, now spend more than 3% annually. In contrast, the UK spent just 1.7% of GDP on R&D in 2019, barely changed since the 1.6% spent in 2000.3 The government’s target is to increase total investment in R&D to 2.4% of GDP by 2027, although it is unconfirmed if this will remain under the new administration.

Much UK investment in R&D is spatially concentrated in the Greater South East (GSE) region4 which is home to world leading science and technology institutions and clusters situated in the ‘Golden Triangle’ between Oxford, Cambridge and London. The GSE received 54% of total R&D investment in 2019, including 61% of funding from public sources, but only accounts for just over a third of the UK population.

A concentration of R&D activity arguably contributes to spatial inequality since innovation is linked to higher rates of growth and wealth creation. The Levelling Up White Paper seeks to increase public investment in R&D by at least 40% outside the GSE by 2030 and leverage at least twice as much in private sector investment.

Gross expenditure on R&D

The West Midlands (ITL1) is an important region for innovation activity and attracts a relatively high share of R&D investment outside of the GSE.

West Midlands expenditure on R&D from all sources totalled £2.9bn in 2019, representing 8.5% of England’s total and more than Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland. Regional per capita spending was £492 compared to the England average of £606, although this falls to £402 per head excluding the GSE.

Regional R&D activity is undoubtedly driven by business, with the sector accounting for 81% of total R&D investment in 2019, far more than the average for England as a whole (69%) and unsurpassed by any other region. The region receives a relatively small share of government, UKRI, higher education and non profit R&D funding.

R&D expenditure by region (2019)

Source:ONS,Grossexpenditureonresearch&development,2019.

Business expenditure on R&D

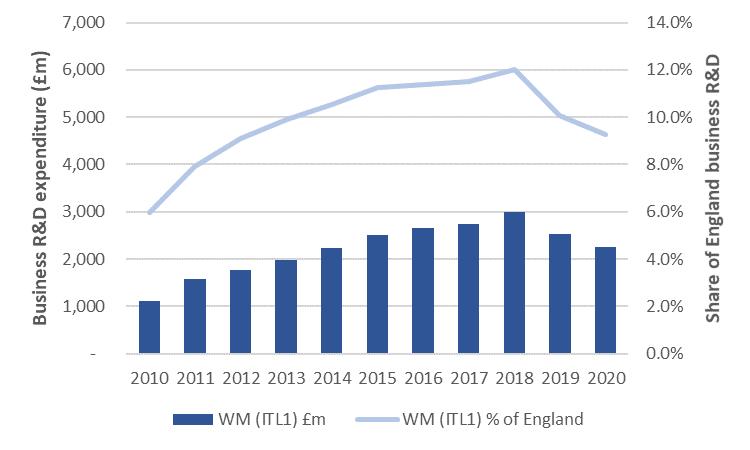

West Midlands business expenditure on R&D has increased over the past decade at a faster rate than nationally. It reached £3billion in 2018 (at 2020 prices) accounting for 12% of the England total, up from 6% in 2010. However, expenditure fell between 2018 and 2020 to £2.26bn, or 9.3% of England’s total.

Business R&D expenditure for West Midlands (ITL1) region

Source:ONS,Businessenterpriseresearchanddevelopment. BusinessR&Dexpenditureshownatconstantprices.

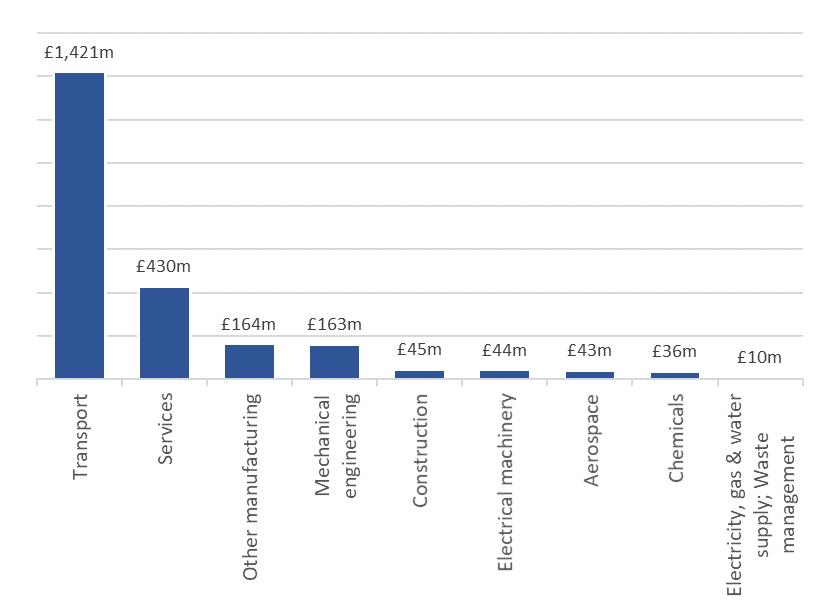

The most recent available figures for 2019 show that a very high proportion of regional business R&D investment is into transport and other manufacturing related areas. The impact of the pandemic on automotive, transport and manufacturing is likely a key contributor to the decline in business R&D in recent years.

West Midlands business expenditure on R&D by product group (2019)

Source:ONS,Businessenterpriseresearch&development.

The UK government has expressed a strong commitment to ‘levelling up’, including a focus on place based policy interventions and investments to drive more equal regional growth across the country. UKRI is the main funding agency responsible for promoting R&D and innovation, with an annual budget of £8 billion. This involves a balancing act to keep the UK at the forefront of key areas of R&D, science and technology while improving our capacity to leverage University based R&D for economic growth and social change. We have historically been better at the former than the latter, and the ‘valley of death’ between invention and innovation is still a feature of the UK economy.

The UKRI 2022 2027 delivery strategy features a central focus on the place agenda, with an aim to “…support thriving research and innovation clusters across the UK, creating diverse high value jobs and local economic growth.” A key objective is also to “…support the development of evidence to inform local, regional and national policies and interventions to address regional disparities and enhance place based livelihoods and economies.”, which is where City REDI plays a leading role.

Much of UKRI funding is channelled through Innovate UK. It has a specific remit ‘to support business led innovation in all sectors, technologies and UK regions, helping businesses grow through the development and commercialisation of new products, processes, and services.’

Increased funding for public private / university business collaborations, knowledge transfer partnerships, local innovation accelerators and other schemes to improve regional innovation ecosystems are planned. It is also committed to investing £100 million into ‘Innovation Accelerators’ as pilot projects in Birmingham, Glasgow and Manchester.

Analysis of past UKRI investments into R&D collaborations involving universities and businesses, shows significant variation in local sector ‘specialisation’ and interregional collaboration. The distribution and impact of past funding needs to be understood to guide the current government agenda, to catalyse better economic growth.

The Distribution of Innovate UK Funding

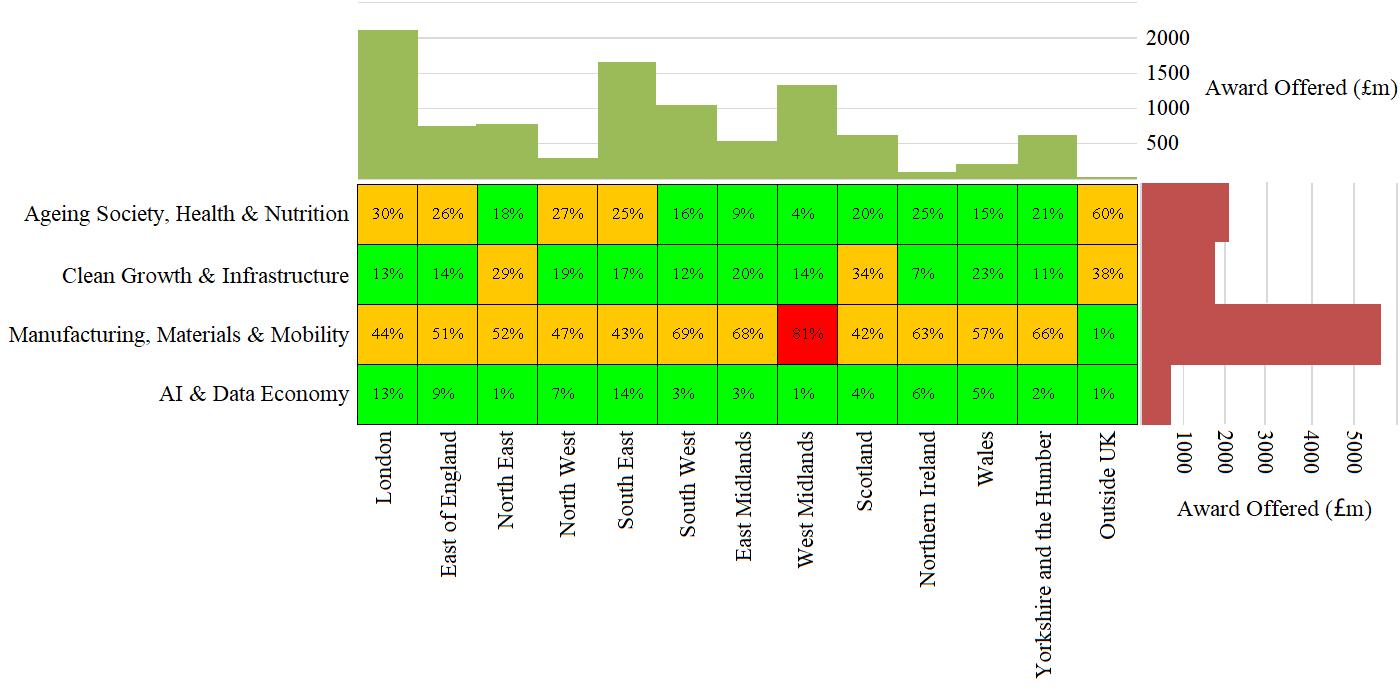

Figure 1 shows a breakdown of Innovate UK funding from 2004 to 2021, including the percentage of awards received by each of the 12 regions across its four main thematic areas: Ageing Society, Health & Nutrition (Health); Clean Growth & Infrastructure (Clean Growth); Manufacturing, Materials & Mobility (Manufacturing); AI & Data Economy (Data). Total funding for each region is denoted by the green columns at the top, with London and the South East, followed by the West Midlands receiving the dominant shares. The percentages relate to this overall figure, per region. The red bars along the rows show the total amount of funding dedicated to each key theme, with Manufacturing receiving the dominate share (almost three times the investment in Health).

This provides a portfolio view of each theme and each region, and it shows that the West Midlands has the most concentrated portfolio of all the regions. 81% of West Midlands funding is in the Manufacturing theme and less than 5% in two of the remaining three areas.

Figure 1: Innovate UK funding from 2004 to 2021, by region and theme

Like Scotland, the North West region, centred on Manchester, has a more evenly distributed funding portfolio, although the top category is Manufacturing with 47% followed by Health (27%) and Clean Growth (17%). Clearly there are trade offs between a more specialised and focused portfolio, like the West Midlands, following its automotive manufacturing legacy, and a broader range of capabilities across thematic areas, like the North West.

What kinds of collaborations between universities and businesses underlie these regional and thematic patterns of funding? Analysis of overall UKRI funding, including but beyond Innovate UK investments, reveals which regions work with each other shows how specialist networks have evolved to connect local clusters of activity The data shows that almost all collaborations involve firms, and 34% involve only firms and no other partners. More than half (59%) involve firms and universities working directly with each other and less than 7% of all collaborations funded by UKRI involve intermediaries such as research and technology organisations (RTOs) or catapults.

Focusing again on the West Midlands, data on public private collaborations in 2019 (Figure 2) show that London is the main location of partners on UKRI funded projects with West Midlands based participants. This pattern dominates over intra regional collaborations in the West Midlands, and relatively little collaboration takes place with other UK regions.

Figure 2: Collaboration between West Midlands based partners and those based in other UK regions via public private projects funded by UKRI.

These patterns of publicly funded R&D collaborations raise several questions in light of the government’s future agenda and UKRI’s delivery strategy. These investments appear to be reinforcing long term patterns of growth, focusing on past strengths, like automotive manufacturing in the West Midlands. They also seem to be maintaining the dominance of London.

Should these market interventions be more ‘mission led’ and target new areas growth, focusing on the future potential of regions? Should they also be stimulating collaborative networks across regions in outside of London, leveraging university based R&D to strengthen regional innovation ecosystems and enabling more balanced economic growth across the UK?

Innovation potential

The region is primed to deliver innovation led growth. It is host to several research intensive universities, including University of Birmingham and University of Warwick, and benefits from high levels of business investment in R&D. Government intentions to boost R&D outside the GSE present a huge opportunity for Birmingham and the West Midlands, especially if increased public funding follows business led R&D.5

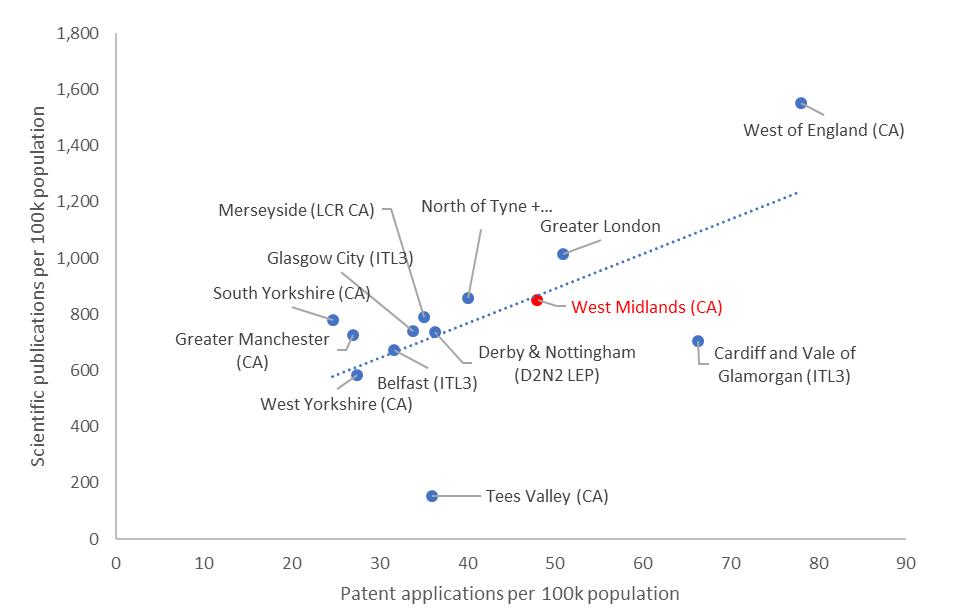

Analysis by City REDI found that the metropolitan (WMCA) area has a higher science and technology intensity than most other comparable UK metropolitan areas as measured using scientific publication and patenting data.6

Science & technology output excluding Oxford & Cambridge

Translating these innovation inputs into new products, services and processes is important for generating prosperity. Whilst the UK as a whole underperforms international comparators in this area, City REDI analysis suggests the West Midlands does relatively well in the national context since business led R&D is inherently more applied and translational.7

The region’s five universities could have a significant role in levelling up local communities through R&D activities. A study by London Economics has shown that research and knowledge exchange activities can account for half their total economic impact.8 Impact pathways include leveraging business investment in R&D, attracting higher value jobs, enhancing local firms’ competitiveness, effecting higher rates of student retention and entrepreneurship and contributing to agglomeration effects.9

The region is also home to several internationally leading centres of innovation, known as STEM assets, that help to bridge the ‘valley of death’ between basic research and commercialisation by bringing scientists and industry together. Regional STEM assets include the Warwick Manufacturing Group, the Manufacturing Technology Centre, Tyseley Energy Park, and the forthcoming Birmingham Health Innovation Campus due to open in 2023.10 The West Midlands

5 REDI Updates 3, Ioramashvili, Humphreys & Collinson, 2022, Less is More? Will the Levelling Up White Paper Rebalance the Regional Distribution of R&D Spending?

6 City REDI blog, Humphreys, Ioramashvili, Collinson, Read & Pan, 2022, How Does the Innovation Performance of the West Midlands Rank on the National and International Stage?

7 City REDI blog, Ioramashvili & Collinson, 2022, Regional Systems of Innovation How Does the West Midlands Compare With its European Counterparts?

8 London Economics, 2021, The economic impact of the University of Oxford

9 City REDI blog, Collinson, 2022, University R&D and Innovation Are Essential to Government Ambitions for Levelling Up

10 Refer to WMREDI research into university STEM assets

is also one of three areas set to receive a share of £100m investment into an innovation accelerator in the coming years.

Professor Simon Collinson, DPVC for Regional Engagement and Director of City REDI and WMREDI, Birmingham Business School, University of Birmingham and Dr. Carolin Ioramashvili, Research Fellow, City REDI, University of Birmingham.

The West Midlands has a long and proud manufacturing tradition, partly driven by a wide range of small and medium size enterprises (SMEs), from recent start ups to long established family firms. Many of these are suppliers to the larger automotive manufacturers, which are concentrated in the region. For these businesses, but also the region as a whole, pursuing innovation to drive competitiveness, grow sales and expand into new markets, is paramount.

But the region also has a significant productivity gap in comparison to the UK average and international counterparts. SMEs in the West Midlands with low skills and low levels of capital investment are a major contributor to this gap. They often face hurdles that are harder to overcome than for their larger rivals. Maintaining in house research and development capabilities may not be practical or feasible and management’s time is often focused on running the day to day business, rather than understanding and adapting to future market trends and opportunities. These firms are less innovative and less resilient as a result.

Enabling SMEs to improve their productivity and competitiveness has a wider range of potential regional impacts. Improving skills is key to both better firm level productivity and higher wages for employees. This in turn increases household incomes, and in many cases this helps reduce the vulnerability of low wage communities. SMEs become more resilient and less likely to fail (increasing unemployment), and the regional economy as a whole is stronger in the face of economic shocks.

University Partnerships Part of the Solution

University based R&D is at the cutting edge of the technological frontier and the West Midlands has a clear advantage, with excellent science and engineering departments based at the Universities of Birmingham and Warwick, amongst other institutions. But accessing the knowledge and capabilities available within universities is often challenging for SMEs. Lack of time and resources, alongside organisational and cultural differences make it difficult for the two to come together.

Two organisations located in the West Midlands have a central role to reduce these barriers and make academic research accessible to SMEs and other businesses, improving their ability to innovate. We have conducted case study interviews with representatives from Warwick Manufacturing Group (WMG) and the Manufacturing Technology Centre (MTC) as part of our research into regional innovation ecosystems. Both also act as High Value Manufacturing (HVM) Catapult Centres, funded by Innovate UK.

The Warwick Manufacturing Group (WMG)

WMG was formed in 1980 and is structured as a department at the University of Warwick but run as a hybrid organisation, with 50% of its staff from academia and 50% from industrial backgrounds. More recently, its manufacturing roots have expanded from the automotive industry to other sectors, including aerospace, energy, pharmaceuticals, cyber security and construction. Alongside its research, WMG also delivers education and training as part of its role within the university. WMG launched two Academies for 14 to 19 year old students who are exposed to industry from a young age before going on to apprenticeships and degree courses. At the post secondary level, WMG trains 800 degree apprentices annually who complete an industry based apprenticeship while studying towards a bachelor’s degree at the same time.

The WMG approach focuses not just on manufacturing, but also wider business processes, to improve their ability to adopt and exploit new technologies and practices to improve competitiveness. This cross fertilisation also happens through the co location of businesses on the Warwick campus, as well as through embedding SMEs within larger research consortia that WMG is involved with. However, challenges remain. An SME that is currently collaborating with WMG appreciates the ability to access talent and some distinctive processes and practices that they were not able to find among private sector consultancies, but laments the bureaucratic hurdles of working within university structures.

The Manufacturing Technology Centre (MTC)

MTC is an independent Research and Technology Organisation founded in 2010 by four institutions Loughborough University, the Universities of Birmingham and Nottingham, and TWI. It was established near WMG in Ansty Park, Coventry, and a further three locations have been added in Liverpool, Oxford, and the London Borough of Havering. Alongside this geographical expansion, its activities have broadened from R&D to encompass training, advanced manufacturing management as well as factory design. MTC operates as a private company limited by guarantee, whose guarantors are its three founding universities. Annual profits of three to six per cent are reinvested into the business.

MTC’s approach is focussed on first raising awareness within the SME community of new technologies that may be relevant to them, combined with a diagnostic service to clearly identify the challenges faced by a firm. New processes and technologies are then rolled out, often together with a bespoke training offer, recognising that most smaller businesses do not need to invest in R&D to reinvent the wheel, but can meaningfully drive their productivity and other goals by deploying off the shelf technologies that may even be a few years old. The research agenda at the technological frontier pursued by MTC is shaped by its industry members. However, these tend to be larger businesses, as this sort of engagement tends to be less valuable to smaller firms, as described by one long term collaborator SME of MTC.

Table 1: Case study scale and scope Warwick Manufacturing Group (WMG) Manufacturing Technology Centre (MTC)

1980 2011 Funding £60 million p.a. £83 million p.a.

Funding source 1/3 Catapult centre funding, 1/3 collaborative R&D, 1/3 contract research

25% Catapult centre funding, 35% collaborative R&D, 40% industry members

Legal form University department Company limited by guarantee, owned by 3 universities Employees 500 800

Locations Coventry Coventry, Liverpool, Abingdon (Oxfordshire), Rainham (London)

Both organisations work with industry to transfer new technologies to their existing processes and work collaboratively to develop new or improve existing processes, products and services. As part of their SME support, funded through the Catapult programme, both organisations offer a diagnostic and consultancy service, whereby a team of academics or engineers visits a firm’s site to inspect their processes, and identifies some areas of improvement or upgrading. Depending on the businesses’ needs, this may then result in a longer term collaboration.

As shown in Table 1, MTC has grown to be larger than WMG and slightly more diverse and less connected to the local university base. These differences and others reflect how both organisations have evolved along different pathways to serve distinctive functions as regional innovation accelerators. But they are both significant sources of new and applied knowledge and skills, processes and technologies, to speed up the innovation adoption process in local firms. This is critical in the context of the UK’s levelling up agenda.

Key funding agencies and government departments, including BEIS and UKRI, are focused on investments to promote innovation to drive local growth in places outside London and the Southeast. Precision interventions are needed, based on strong evidence about how innovation accelerators, alongside other policy interventions have different impacts on the real economy in different places. The long term outcomes must include more balanced, inclusive and sustainable growth across UK regions.

WMG and MTC show how a local offering is important in this respect. Significant local barriers to innovation can only be reduced meaningfully and sustainably through long term, embedded relationships and a deep understanding of businesses’ challenges and how to resolve these with new technologies, expertise and skills. Further research at City REDI is underway to understand more about the specific local and national impacts of these organisations, in the context of current (or the next wave of) government policies.

Clayton Christensen, the author and creator of disruption theory defines a disruptive innovation as:” a product or service designed for a new set of customers”. Further clarification is that technology disruption is the advent of a new or existing technology that is used and/or created in such a way that it renders the incumbent obsolete over years or decades. The Harvard business review often describes the business model rather than the technology itself disturbing the market or value network, creating new markets in its new wake. An example of this would be in the 1970’s when IBM developed the personal computer which disrupted the market for type writers and mainframe computers, by bringing computers to the general public. The personal computer has since been disrupted by the laptop and smartphones.

Birmingham city has been well known for its manufacturing sector for many years, in recent years its manufacturing sector has seen a decline due to many factors such as manufacturing businesses moving their business abroad for cheaper costs on supplies, production etc. However, in recent years Birmingham has become a hub for technology innovation, especially with the recent creation of an innovation hub at Tyseley Energy Park. Innovation is at the forefront of the Birmingham technology scene and can present plenty of opportunities for sectors, such as manufacturing to improve its productivity and efficiency, but whilst this kind of technological disruption can provide plenty of opportunities it can also present/highlights risks that can impact manufacturing negatively and hinder its performance.

With the advent of technological change impacting the manufacturing sector, there becomes some key risks with the adoption of technology in places where human hands have been producing goods for hundreds of years. In terms of automating industrial control systems in a 2016 survey 31% of manufacturing respondents admitted they had never performed a cyber risk assessment of their industrial control systems. While automation of these control systems does present some opportunities for growth in terms of increased output and a more efficient production line, enabling manufacturing firms to remain competitive in these difficult times. It also is worrying that a lot of manufacturing firms have not conducted a risk assessment as not doing this leaves security vulnerabilities unresolved and can actually increase the risk of hackers tampering with systems or even shutting down an entire production line until demands or payment are met. Meaning that if companies do not perform adequate risk assessments on their technology it could cause further issues down the line in that many firms may have to close down due to them being unable to compensate for losses incurred or time lost from having their production lines shut down.

Manufacturing of electric car batteries is being explored and developed to keep in line with the government’s 2030 target of only electric vehicles being sold and petrol ones will cease being sold. Electric car batteries are not a new concept but with the announcement of the government’s plans of only EV’s being sold, to keep in line with the UK target of being net zero by 2050 more and more larger companies such as Bentley motors and Jaguar are beginning to develop electric car batteries and smaller companies are beginning to do the same thing. In particular one company in Birmingham Petalite, has a developed the world’s fastest charging portable battery technology, there is opportunity in this as it would allow charging technology to become more efficient and could improve on electric car battery design. Significantly reducing the charging time of vehicles or other technologies that require a portable charger, and as such this would allow manufacturers to keep productions lines running. Thus, enabling increased outputs and can safeguard against issues such as power failure which would affect their production output and competitiveness.

VR technologies are being implemented into the manufacturing at an increased rate to enable more efficient business operations. A few opportunities that VR technology allows for Birmingham manufacturing sector in terms of the automotive sector where assembly lines are common, VR can be used to plan factory floors so manufacturers can see everything is placed correctly and connected and as such using VR can help save with costs and reduced the risk equipment damage or worker injury. An example of businesses doing this is Daden who

specialises in Virtual reality technology and if this type of disruptive technology could be further integrated in the manufacturing sector, it would allow the training of worker on hazardous or complex design processes to become more efficient and can save on training costs. Another example of the types opportunities VR technology can be demonstrated by Ford motor company who use an immersive vehicle environment VR tool that allows engineers to check a 3D new car models its less expensive to produce than a real car and easier to modify if the inspection finds any flaws, thus saving in costs and reducing the amount of materials are wasted.

Innovation challenges

Despite the relatively high degree of business led spending on R&D in the wider region, data indicates a less innovation activity taking place within the city region itself, particularly in comparison to other Local Enterprise Areas nationally.

The UK Innovation Survey 2021, covering 2018 2020, showed that the West Midlands (ITL1) region has a high proportion of businesses engaged in innovation activity (48.6%) versus the national average (45.7%). However, the Survey showed that only 36.4% of businesses are innovation active in Greater Birmingham. This is second lowest amongst the 38 LEP areas in England, above only Hull and East Yorkshire where only 22.9% of businesses are innovation active.

Local businesses and workers in the city region may still benefit if they are able to connect with innovation activity in the broader region as part of a connected innovation ecosystem, for example through financial or design services.

Whilst businesses in Greater Birmingham are more likely to engage in internal R&D (17.2%) than average, this is low relative to other LEP areas. For instance, almost a third of businesses in the Greater Cambridge and Oxfordshire areas invest in internal R&D, whilst the figure is almost one in four for businesses in Cheshire and Warrington, Leeds, Leicester and Leicestershire and the South East Midlands.

Businesses in the wider West Midlands also allocate a lower share of innovation expenditure to internal R&D (32%) than nationally (52.2%). In contrast, businesses in the East of England spend 62.9% and those in the North West spend 57.2% of innovation expenditure on internal R&D.