2022

Chapter 5: Opportunity: Building on Strengths

Connect. Support. Grow.

Birmingham Economic Review

Introduction

The annual Birmingham Economic Review is produced by the University of Birmingham’s City REDI and the Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce. It is an in depth exploration of the economy of England’s second city and a high quality resource for informing research, policy and investment decisions.

This year’s report provides comprehensive analysis and expert commentary on the state of the city’s economy as it emerges from disruption caused by the pandemic into a new period of high inflation and uncertainty. The Birmingham Economic Review assesses the resilience of the city, its businesses and its people to the set of challenges stemming from the UK’s vote to leave the EU, the coronavirus pandemic and now the energy crisis. It includes an update on the development of the region’s infrastructure and highlights opportunities for growth, building on existing strengths and assets.

The most recently available datasets as of 30th September 2022 have been used. In many circumstances there is a significant lag between available data and the current period. Contributions from experts in academia, business and policy have been included to provide timely insight into the status of the Greater Birmingham economy.

Report Geography

The report focuses on the ‘Greater Birmingham city region’ defined by the boundaries of the Greater Birmingham and Solihull Local Enterprise Partnership (GBS LEP). The GBS LEP area consists of the following local authorities: Birmingham, Solihull, Bromsgrove, Cannock Chase, East Staffordshire, Lichfield, Redditch, Tamworth, Wyre Forest.

References to the ‘West Midlands region’, or ‘West Midlands (ITL1)’, are to the large scale region at International Territorial Level 1 (ITL1). There are nine ITL1 regions in England: North East, North West, Yorkshire & The Humber, East Midlands, West Midlands, East of England, London, South East and South West in addition to Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. Note that ITL recently replaced the EU’s Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics (NUTS). Geographies of ITL and NUTS territories generally correspond except for minor differences at local authority level outside the Midlands.

References to the ‘West Midlands metropolitan area’ are to the West Midlands county comprising seven metropolitan districts (WM 7M): Birmingham, Solihull, Coventry and Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall, Wolverhampton.

References to the ‘West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) area’ are to that administered by the Combined Authority.

Note that figures may not always total exactly due to rounding differences. Figures in some tables may be undisclosed due to statistical or confidentiality reasons.

1

Foreword and Welcome

Chapter 1. Economy: Crises and Resilience

Chapter 2. Business: Disrupted Markets

Chapter 3. People: Challenging Times

Chapter 4. Place: Connecting Sustainable Communities

Chapter 5. Opportunity: Building on Strengths

2 Index

Opportunity: Building on Strengths

This year’s Birmingham Economic Review paints a challenging picture for businesses and residents in the context of crises affecting the regional, national and global scale. Yet, great things are happening in the city and region and the best days lie ahead, not least due to the Commonwealth Games which thrust Birmingham onto the international stage this summer showcasing the city’s diversity, creativity and ever changing skyline.

Birmingham’s future lies in its global reach and attractiveness as a destination to visit, do business and to study. Huge opportunity exists in growth sectors that benefit from regional clusters of internationally significant innovation and creative activity, including in the green economy. As highlighted in Chapter 4, the city is undergoing continued transformation of its transport network and urban environment connecting communities and challenging outdated perceptions.

This chapter takes a look at the opportunities facing the city region over the coming years.

Birmingham 2022

The hosting of the 2022 Commonwealth Games was a major moment for the city. As the largest sporting event since the 2012 Olympics, it was delivered successfully and in record time, an impressive feat given disruption caused by Covid 19 in the run up.

An early review of the Games published by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport highlights the immediate impact of the sporting event. It is estimated that almost half the UK watched or attended the 11 days of sport whilst hundreds of millions tuned in globally. A record 1.5 million tickets were sold and more than 5 million people came to the city centre, a 200% increase on the same period in 2021.1

The Games created over 40,000 jobs and skills opportunities, including 14,000 volunteer positions. Over 7,500 people were trained. A six month long cultural programme celebrated and showcased the region’s heritage and diversity whilst ‘tiny forests’ were planted and 22 miles of canals cleaned as part of sustainability measures.

Almost £800m of public investment is driving regeneration and investment in the city, including the provision of new sports facilities, refurbishment of the train station and development of up to 5,000 homes in Perry Barr.

Sustainment of the positive economic, social and environmental impacts is key to a lasting legacy. The Business and Tourism Programme (BATP) aims to do this by promoting the region’s reputation as a leading destination for tourism, trade and investment, for key sectors including future mobility, business, data driven healthcare, creative and digital technologies, and the sports economy. The programme was supported by UK House hosted at The Exchange in Birmingham’s Centenary Square during the event.

3

1

DCMS, Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games: the highlights [accessed September 2022]

Nicola Turner, Director of Cross Partner Legacy, Birmingham 2022.

The Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games gave us stellar moments of sport in stadia across Birmingham and the West Midlands. The incredible Opening Ceremony held audiences rapt, and there is no doubt that a revival of this city’s cultural heartbeat has been energised by the six month Birmingham 2022 Festival.

But the live audiences, city visitors and television viewers won’t have seen how the Games have impacted the city, how the region’s economy has been improved, how communities have come together, and how the Games is leaving an imprint on the lives of people.

Setting out to kickstart positive change in the West Midlands, the significant public investment of £778 million has accelerated regeneration and infrastructure improvements in places like Sandwell and Perry Barr, which are amongst the most deprived in the country. People’s livelihoods and health will be changed and enhanced by the regeneration of Perry Barr and Alexander Stadium, by increased connectivity and sustainable transport options. Learning from previous Games, Sandwell Aquatics Centre was designed for its local community and “loaned to the Games” for two weeks of world class sport. Investment in the Games also helped to unlock more than £85 million of additional investment into the Games’ legacy programmes2, aligned to ambitious levelling up plans for both city and region.

We will have to wait until 2023 to discover the true economic impact and for the first time we will also report on social impact. This will assess whether the benefits have reached people far beyond the athletics track, the swimming pool or on the pitches; whether our ambitions for sustainability, jobs and skills, disability inclusion, community cohesion have reached the people who wouldn’t usually take part; and whether Birmingham 2022 is attracting new trade and new visitors to our city, region and nation.

From venues to volunteers, we want people to take away a view that our region is an inclusive, youthful, and distinctive place, where people and especially young people matter. From sustainability to social value young people’s voices helped us to shape the Games as they urged us to tackle inequalities of all kinds, to advance inclusion and be bold with our goals for sustainability.

In our delivery we piloted new ways of working to include those who face the most challenges, listening and then creating pathways for them to join in through training, jobs, volunteering or being involved in the Queens Baton Relay and our ceremonies. It has surfaced stories like these:

Kieran is from South Birmingham and lost his job working in a local shop during the pandemic. Unemployed and low in confidence, his work coach at the Job Centre recommended security and stewarding training through the Commonwealth Jobs and Skills Academy. Kieran loved it. Post training, he went for an interview at a Games’ supplier, hoping to join the roster for the Games. The supplier was so impressed that they offered him a permanent job as a Vetting Officer. Kieran feels he is in this job because of the Games and he has set his sights on a long term dream to become a police officer.

The Gen22 programme is delivering 30,000 hours of social action across the region for young people aged 16 24, empowering them to gain experience, confidence and skills by helping their own communities. One of our Gen22 groups, comprised of young people with disabilities and Special Educational Needs, wanted to help refugees arriving from Afghanistan with few possessions. The group used their talents and skills to collect items needed by the young refugees. They went on to fill 100 boxes, personally delivering bespoke parcels and a warm welcome.

These are just two stories. There are thousands more. Thousands of individuals whose lives have been positively impacted by Birmingham 2022. Positivity that will go forward in the confidence, skills and optimism of local people who worked, volunteered, or felt part of this Games.

4

2 For more information on the Birmingham 2022 legacy see our updated legacy publication

There are signs that the Games has kickstarted something special in Birmingham, something that started with sport, but that is spreading out far beyond venues and stadiums and making a real difference to people’s lives and aspirations. And it doesn’t just stop. A number of our programmes are already confirmed to continue, and we intend to keep the positive impact flowing through the establishment of a legacy charity: United By 2022. United By 2022 is building a community fund that will continue to invest in the region after the Games and wants to empower people to solve challenges on their doorstep, champion fairness and inclusivity, and ensure communities gain full use of the Games’ venues and assets.

Birmingham 2022 has always been about so much more than sport and tickets. We have set the wheels in motion for a strong legacy and in step with Birmingham’s motto, ‘Forward’, we are moving now!

5

Dr Matt Lyons, Research Fellow, City REDI, University of Birmingham.

The Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games concluded in August after showcasing to the world the best the region has to offer. Spectators flocked the city and we saw busy transport hubs and full hotels. Now the buzz of the event has receded attention has turned (for economists at least) to the economic impact of the event and in the long term its legacy.

The Commonwealth Games received £778 million in public funding from a mix of central Government and Birmingham City Council resourcing. As ever with this level of public spending it is reasonable to ask: What does all the economic activity mean for the local economy?

In an early assessment of the impact of the games based this study uses historic data and assumptions to estimate the economic impact of the Birmingham Games with estimates to be refined as data becomes available improves.

Method

To provide an analysis of the regional economic impact we use the Socio Economic Impact Model for the UK (SEIM UK). The SEIM UK shows a complete picture of the flows of goods and services in the UK economy over one year (base year 2016). To estimate the spending of visitors we follow the analysis of Allan et al., 2017 and evaluate the spending of three groups, tourists (overnight visitors), excursionists (same day visitors), and athletes.

Table 1 shows the figures used to plug into the model with a base scenario (1) and two further scenarios assuming greater visitor numbers (20% and 50% respectively). We anticipate the figures on visitor numbers, expenditure behaviour to be refined with subsequent surveys.

6

Table 1: Commonwealth Games Tourist Spending Estimates Number of days Average daily expenditure* Number of visitors Scenario 1 Scenario 2 Scenario 3 Tourists (overnight visitors) 6.8 63.61 8,800 10,560 13,200 Excursionists (same day visitors) 2.6 139.49 205,000 246,000 307,500 Athletes 11 27.9 6,500 6,500 6,500 *Numbersadjustedforinflation Source:AdaptedfromTNSetal.,2014

Visitor spending is split across four sectors of the economy:

Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles

Transportation and storage

Accommodation and food service activities, Arts, entertainment and recreation

Once more this is a narrow view and should be clarified in time.

Results

We estimate that the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games will lead to an increase in output of £77 £106 million, an increase in GVA by £37 £51 million and create between 1,037 and 1,439 jobs (FTE).

It is important to note that these jobs are likely to be ephemeral and will not endure after the games have ended. It might be more accurate to describe them as “job years” that have been created.

Table 2 reports the output, value added and employment multipliers for the UK economy associated with scenario 1. The output multiplier can be read as for every £1 visitors spent on the games £1.75 was generated throughout the economy. The employment multiplier can be read as for every £1 million visitors spent 23.7 FTE jobs (or job years) are created.

Table 2: Scenario 1 Output, Value Added and Employment multipliers

Multiplier effect (per £)

Output multiplier (per £) 1.75

Value added multipliers (per £) 0.85

Employment multipliers (per million) 23.7

When we consider the economic impact at the regional level we can see that the impact is largely concentrated in the West Midlands (UKG3) with 90% of the change in GVA as a result of the games being contained in the region.

Conclusions

There is a degree of scepticism among economists about the economic benefits of hosting mega events like the commonwealth games. Mega events have often been the subject of economic appraisal and have been frequently found to not boost the local economy beyond the cost of the event itself through revenues raised during the event alone. There is also the question of opportunity cost. What other projects were discarded or postponed due to the public spending on the games.

Despite these concerns, there is significant potential for indirect impacts that are less easy to quantify. The games will likely have generated reputational effects that challenge negative perceptions of Birmingham. There might be young aspiring athletes inspired by seeing the games in person. The new infrastructure built for the events might have considerable impacts on local communities over time. Additionally, there are the impacts on civic pride derived from all the activities across the city not least watching Ozzy Osbourne shouting “Birmingham Forever”.

7

One area that has been of focus for Birmingham 2022 is the potential for the games to attract business investment and increase exports. There is considerable potential for this; Rose et al., (2011) show that hosting a mega event has a strong positive impact on national exports.

To help capitalise on this investment the Business and Tourism Programme (BATP) has been developed to coincide with the Commonwealth Games. The stated objectives of the BATP include softer impacts such as ‘increasing positive perceptions of the West Midlands and wider UK’. But also, goals for economic impact in terms of boosting economic benefits through ‘increased exports, ODI and FDI’.

A broader and more detailed appraisal of the economic impact of the games will follow as the data becomes available.

ThispieceisbasedonablogontheCityREDIwebsite.Thepiecepresentsanearlystageofa collaboration between CityREDI/WMREDI and The University of Strathclyde to assess the economic impact of the Commonwealth Games. Additional thanks to Saad Ehsan and Prof AndreCarrascalIncerafortheirinitialworkonthispiece.

8

Dr. Shushu Chen, Lecturer in Sport Policy and Management, University of Birmingham.

The argument that major sporting events create legacies such as city regeneration and economic growth has repeatedly been used politically to justify event bids3, and these types of legacies have been researched extensively4. By contrast, social legacies and impacts remain relatively understudied5

However, this does not mean that social legacies are unimportant.

Let’s first look at what social legacies entail. According to the systematic review of Mair et al. (2021), event legacy research has included social elements specifically concerning ‘inclusionanddiversity, ‘volunteering’, ‘social cohesion, civic pride, and social capital’, ‘business and government partnership’,‘disasterpreparedness’,‘sportparticipation,infrastructure,andhealth’,‘destination branding’,and‘accessibility’

Unlike economic and environmental legacies, which some might argue benefit only certain business sectors (e.g., tourism and trade) or certain locations within a host city (areas close to stadiums where major infrastructure tends to be focused), social legacies can, in theory, benefit all individuals and communities in a host region.

Social legacies are transboundary (in terms of ethnicity, gender, and other socio demographic categories) and perhaps more important than ever in the aftermath of the COVID outbreak, when people are actively seeking reasons and opportunities to celebrate and to socialise with family and friends.

So, what kinds of social legacies have the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games offered to Birmingham citizens and communities?

The Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games has five legacy missions6: (1) bring people together, (2) improve health and well being, (3) help the region to grow and succeed, (4) be a catalyst for change, and (5) put us on the global stage.

Translating those legacy missions into actual legacy programmes and activities, the pre games legacy evaluation report produced by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport7 outlined that two out of the five legacy missions (1 & 2) appear to have been strongly focused on social legacies anticipating outcomes for ‘physical activity and wellbeing’ , ‘community cohesion,inclusion,andpride’, ‘youthandlearning’ , and ‘creativeandculturalparticipation’ . And another three legacy missions (3, 4 & 5) encompassed social legacies (specifically ‘accessibility and equality’ , ‘social value’ , ‘skills’ , ‘volunteering’ , and ‘creative and cultural participation’), in addition to other different types of legacies (e.g., economic and environment legacies) that were targeted.

While the abovementioned various social legacy anticipations appear to be consistent with the promises of previous major sporting events and are evidence based (to various degrees), one type in particular sport participation legacies deserves discussion here. This is because, although research8 has suggested time and time again that the hosting of major sporting events does not create sustainable positive sport and physical activity legacies, the expectation persists that the Games will generate a legacy for physical activity and wellbeing to ‘inspireand offertargetedopportunitiesforthepeopleoftheWestMidlandstoimproveandsustainlevels ofphysicalactivity ’ (p. 26).

Cuskelly,

Mair, Chien, Kelly & Derrington,

DCMS,

2022 Commonwealth Games,

Fredline,

impacts of mega

Birmingham 2022 pre Games evaluation

Annear, Sato, Kidokoro & Shimizu, 2022, Can international sports mega events be considered physical activity interventions? A systematic review and quality assessment of large scale population

9

3 McGillivray & Turner, 2017, Event Bidding: Politics, Persuasion and Resistance 4 Thomson,

Toohey, Kennelly, Burton, &

2019, Sport event legacy: A systematic quantitative review of literature 5

2021, Social

events: a systematic narrative review and research agenda 6 Birmingham

2021, Legacy Plan. 7

2021,

framework and baseline report 8

studies

Watching the Games and the performance of elite athletes might inspire individuals and change their attitudes towards sport and physical activity, but it does not necessarily change behaviours as established in our study9 of long term sport participation legacies from the Beijing 2008 and London 2012 Olympics Games. When we examined the effects of other intrinsic and extrinsic factors (e.g., time, money, and sport confidence) on participation behaviour, we found the 'Olympic impact' to be one of the least influential factors affecting sport participation.

Our findings offer two key messages concerning policy learning: First, the findings serve as a warning that the legacy promises for major sporting events such as the Commonwealth Games must be realistic. Second, there is a need for proactive planning and concrete, sustainable mechanisms beyond the hosting of events and the building of stadiums that support sport and physical activity participation.

10

9 Chen, Liang, Hu & Xing, 2022, Long term sport participation impact of mega sporting events: Evidence from the Beijing 2008 Games and the London 2012 Games

Leveraging the economic potential of the Games

During the Commonwealth Games, Birmingham and the wider West Midlands shone on a global stage during a spectacular 11 day festival of sport. In addition to unprecedented ticket sales and Birmingham’s hotels seeing upwards of 85 per cent occupancy, it was impossible to ignore the buzz as people celebrated the region’s melting pot of cultures and communities. Residents and visitors alike soaked up the phenomenal atmosphere created not just by sporting achievements but also by the six month long Birmingham 2022 Festival the region’s biggest ever celebration of creativity and diversity.

However, despite the joy and excitement that the Games has brought us, it’s important to remember that many businesses are in financial crisis and urgent action is needed to reboot our economy. Three global economic shocks have created an impending cost of living crisis for those most in need in society. In addition to the supply chain and labour force impacts of the pandemic, the cost base of many companies is still being impacted by inflationary pressures resulting from the war in Ukraine and operational changes due to leaving the European Union.

It has never been more important to showcase our sector strengths and cement our reputation as a truly global region. The Business & Tourism Programme (BATP), led by WMGC in collaboration with the Department for International Trade and VisitBritain and the first programme of its kind to be a formal accredited part of the Games, is designed to boost the economic impact of the Commonwealth Games by:

Building on the West Midlands’ existing economic ties with Commonwealth markets, such as India, Singapore, Malaysia, Australia and Canada and develop new opportunities in Africa and beyond.

Securing a greater slice of the UK’s foreign direct investment (FDI) and attracting new investment in the region’s infrastructure and real estate offer.

Making the most of the region’s excellent facilities and event management experience to bid for other major international conferences and events.

Attracting a new generation of leisure tourists, including overseas and overnight visitors.

Delivering tangible impacts

We are tracking the impact of the BATP by tracing the ‘customer journey’ a potential investor, conference or event organiser or visitor typically takes for example:

Short term outputs seeing a piece of marketing collateral or media coverage, attending an event or visit, having an initial conversation about a potential investment or visit (i.e. a lead has been generated).

Medium term outcomes becoming more aware and informed about what Birmingham and the West Midlands has to offer, taking a more positive view of the proposition and actively considering a potential investment or visit. Having more specific discussions about requirements and the area’s business case (i.e. the initial lead has been converted into an opportunity).

Longer term impacts making a decision to invest or visit.

11

Andy Phillips, Head of Research, West Midlands Growth Company and Katie Trout, Director of Policy and Partnerships, West Midlands Growth Company

Operational outputs engaging with the market, creating interest and generating leads

Intermediate outcomes changing perceptions and converting leads into opportunities

Final impacts projects anddeals landed, jobs and GVA generated

Workstreams- inwardinvestment, capitalinvestment, MICE andsportingevents, leisuretourism, UKHouse, exports

Events, workshops, familiarisationvisitsandsalesmissionsorganised Attendeesattractedtoevents, workshops, familiarisationvisitsandsalesmissions Leadsgeneratedviaengagementwithattendees

Perceptionsshiftachievedintermsof:

Awarenessof theUKandWMoffer withinkey targetaudiences PositivesentimentinrelationtotheUKandWMoffer withinkey targetaudiences Likelihoodof recommendingtheUKandtheWMtoclientsor actively investingor visiting

Leadsconvertedintoopportunities- potentialinvestmentprojects, conferences or eventsor visitstotheUK or theWM, exportopportunitiesfor WMfirms

Opportunitieswon- investmentprojects, conferencesandeventslanded, exportdealscompleted

Valueof investmentprojects, exportdeals, visitor expenditure Jobscreatedby investmentprojects

GVAgeneratedby investmentprojects, conferencesandevents, domestic andoverseasvisitorsattracted, exportdeals

From

In the first half of 2022 we ran an ambitious programme of marketing campaigns, in person and virtual sales missions to Canada, India, Australia, Singapore, Malaysia, and Dubai, tracing the route of the Queen’s Baton Relay. Then more than 180 events, including sector showcases, business forums, workshops and familiarisation visits, were held in Birmingham and surrounding areas during the Commonwealth Games. So far, the BATP has already attracted:

23 inward investment projects which include the relocation of chocolate production from plants in Germany by US owned Mondelez, including the iconic Cadbury Dairy Milk bar, to the Bournville site in Birmingham, the relaunch of the UK operations of US owned airline Flybe at Birmingham Airport, fighting off stiff competition from Manchester and Exeter, the establishment of a new regional hub in Birmingham by US owned IT services firm Accenture and the arrival, and subsequent expansion of Indian owned business services firm Firstsource.

10 conferences and events including the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (BACPR) conference, the Creative Cities Convention, the International Ceramics Conference, and the World Congress on Rail Research, the IWG World Congress women in sport, British Kabaddi League and Global E sports Federation championships.

Building a lasting legacy

The 2022 Commonwealth Games served as the ultimate shop window for the West Midlands, shining a spotlight on our outstanding sporting, cultural and business credentials. We now need to ensure the eyes of the world remain firmly on our region as we seek to create a lasting legacy.

12 Figure 1: the BATP journey

Autumn 2021 From Summer 2022 2023-2027 Indicative timeline

Mediacampaignreachandmarketspread

Marketingcampaignaudiencereach- websiteandsocialmediatraffic

2 0 0 3 11 1 9 5 19 5 17 10 23 8 28 10 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Inward investment projects landed Sponsors secured Travel trade bookable products developed MICE/sporting events landed Headline impacts (culmulative) 31st December 2021 31st March 2022 30th June 2022 10th August 2022

We have demonstrated what can be achieved when we come together as a region and when we work closely in partnership with Government. We now want to build on this to attract a greater share of FDI and capital, and more visitors and events to the region, benefitting its businesses and communities. It is by doing this that we will revive our economy and regain our position as the fastest growing region outside of London and the South East

13

Birmingham is the third most visited city in Britain, after London and Manchester, for both day visits and overnight visits. An average of 25.9million day visits10 were made between 2017 2019 and there were 205,000 overnight visits in 202111. Prior to the pandemic, inbound international tourism to the West Midlands had been growing significantly faster than for the UK as a whole, especially for business and leisure. Tourism was the UK’s third largest exports industry and had been the fastest growing sector by employment since 2010.12

Growth in inbound international tourism 2010 2019 by purpose

Visits Spend

All Business Holiday All Business Holiday

West Midlands +56% +48% +89% +89% +97% +128% UK +34% +22% +44% +60% +34% +95%

Source:VisitBritain,QuarterlydatabyUKarea. StatisticstakenfromtheInternationalPassengerSurveywhichwassuspendedon16March 2020.

Although recent crises have had a major impact on tourism Visit Britain forecasts inbound visits to be at 65% of 2019 levels this year tourism remains a major opportunity. The sector accounted for £9.6bn of economic value in the Greater Birmingham area and 135,725 jobs in the WMCA area in 2018. Although most visitors were domestic or day trippers, just over half of international tourists to the city came for business and have a higher average spend.13

Increased awareness on the back of the Commonwealth Games is an opportunity to grow international tourism, also drawing on cultural brand such as Peaky Blinders, Shakespeare and the sports teams. India is a key growth market given strong regional family and business connections.

Green Economy

The UK is arguably a leader in clean growth having achieved a 44% reduction in territorial emissions between 1990 and 2019 whilst the economy grew 76%, and having been the first major economy to legislate for an 80% reduction by 2050. Yet, making the net zero transition successfully by this date still poses a huge challenge for business and society at large.

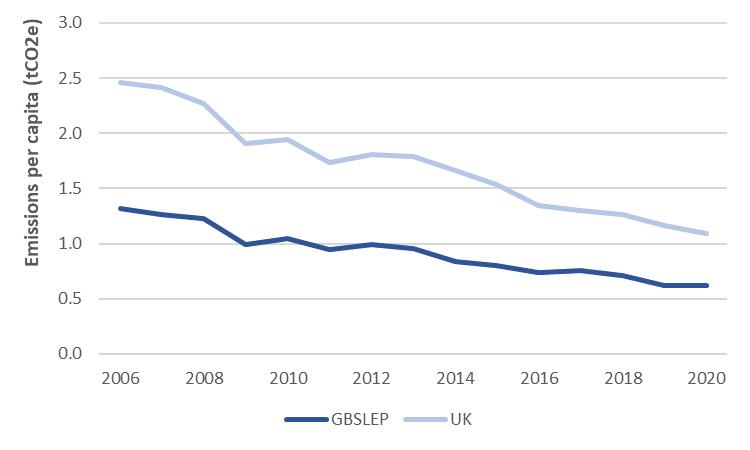

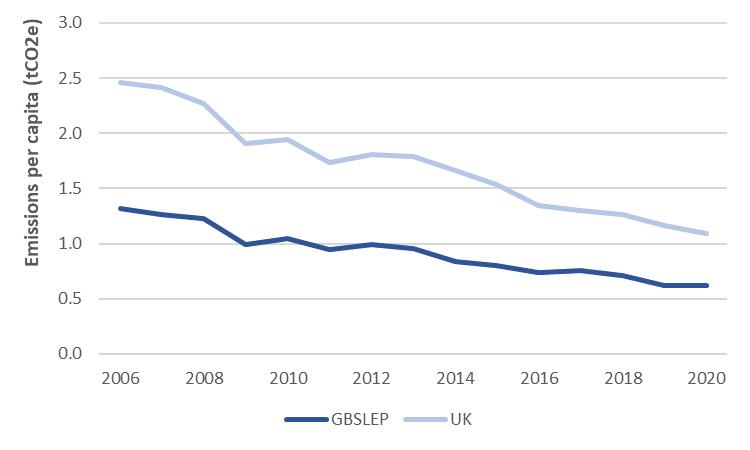

Businesses across the city region have been making good progress to decarbonise their own operations and supply chains but must go further. Despite being a major industrial region, overall per capita emissions (see Chapter 4) and industry specific per capita emissions are lower than average. Greater Birmingham’s industrial emissions have fallen by 57% since 2005 and account for 1.7% of all UK industrial emissions.14

14 Tourism

10 Kantar, The Great Britain Day Visitor 2019 Annual Report 11 ONS, Travel Trends: 2021 figure 7 [accessed September 2022] 12 Visit Britain, Our annual performance & reporting [accessed September 2022] 13 West Midlands Growth Company, Regional Tourism Strategy 2019 2029 14 BEIS, UK local authority and regional greenhouse gas emissions national statistics, 2005 to 2020 Table 1.1

According to Make UK, almost half of UK manufacturers are either implementing or developing a net zero strategy for their organisation, driven primarily by energy cost reductions, although a quarter also recognise the benefits of accessing higher value ‘green’ commercial opportunities.15

The transition to net zero represents a major opportunity for growth given the city’s industrial legacy, world class automotive cluster, leading business services and emerging strengths in clean tech and green energy.

The ONS estimates there are up to 104,000 business in the UK’s Low Carbon and Renewable Energy Economy (LCREE) accounting for between £38.6bn £43.9bn of turnover, 189,000 227,000 employees, and exports of over £6bn (figures for 2020). Although the LCREE sector was impacted by the coronavirus pandemic, it is expected to have now bounced back.

Segmenting turnover by LCREE group and sector reveals the importance of the manufacturing sector, which generates more than a third of LCREE turnover and is of particular importance for energy efficient products and low emission vehicles. Almost nine tenths of turnover from low emission vehicles comes from the manufacturing sector.

15 Industrial greenhouse gas emissions per capita

Source:BEIS,UKlocalauthorityandregionalgreenhousegasemissionsnationalstatistics, 20052020.

15 MakeUK, 2022, COP26: 6 Months on: Where are manufacturers with their net zero

journey?

Low carbon & renewable energy economy turnover by sector (UK, 2020)

Estimated Turnover UK, 2020

Agriculture, forestry and fishing

LCREE Group

Mining and quarrying

Manufacturing

and

gas,

waste

Water supply;

and

Wholesale and retail trade;

and

and

The UK’s automotive industry has become increasingly concentrated in the West Midlands (ITL1), with 32.6% of jobs located in the region as of 2018, more than double the next region. This was up from 29% in 2008 whilst the overall number of jobs grew by 19% over that period.16 As a leading region for the manufacture of motor vehicles, the transition to low emission models is both a risk and opportunity. The region’s leading brands have already announced plans for electrification of future models, including the reimagination of Jaguar Land Rover as an all electric luxury brand from 2025, annual launches of electric models from Bentley starting in 2025, and the launch of Aston Martin’s first battery electric vehicle in 2025. The supply chain will be supported by plans for a gigafactory located south of Coventry which is targeted for production from 2025.

Low carbon heat is a key growth area since domestic sector emissions, primarily driven by residential heating, account for 24% of total UK emissions.17 Although only accounting for £1.5m or 3.5% of LCREE turnover in 2020, low carbon heat is considered to be one of the most scalable interventions with strong potential for upskilling, job creation and emissions reduction. The opportunity is of significance to the construction sector but would also benefit the manufacturing sector further up the supply chain. Retrofit activity is already gathering pace across the region through Net Zero Neighbourhood Demonstrators and The 3 Cities initiative, both potentially supported by the National Centre for Decarbonisation of Heat which is the subject of a Levelling Up Fund bid.

Additionally, a number of low carbon and environmental goods and services clusters have been identified in Greater Birmingham by market intelligence consultancy kMatrix, including intelligent buildings, wind energy drive control componentry, and artificial intelligence for energy management.18

industry: 2008

[accessed

2022]

BEIS, UK local authority and regional GHG emissions, 2020 based on end user emissions Table 4.1c

kMatrix, 2021, Midland Energy Hub Growth Forecast / Regional Report

16

Source:ONS,Lowcarbonandrenewableenergyeconomyestimates. Sectorsaccountingfor25%ormoreofLCREEgroupturnoverarehighlighted.

16 ONS, The UK motor vehicle manufacturing

to 2018

September

17

18

(£bn) A:

B:

C:

D: Electricity,

steam

air conditioning supply E:

sewerage,

management

remediation F: Construction G:

repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles H: Transportation

storage J: Information

communication L: Real estate activities M: Professional, scientific and technical activities N: Administrative and support service activities P: Education S: Other activities All groups 41.2 0% 36% 30% 1% 19% 6% 0% 7% 0% 0% Low carbon electricity 12.6 1% 0% 8% 48% 0% 10% 0% 0% 0% 0% 4% 2% 0% 0% Low carbon heat 1.5 1% 0% 14% 0% 47% 0% 0% 0% 9% 0% Energy fromwaste and biomass 4.3 2% 0% 1% 56% 12% 2% 22% 0% 0% 0% 5% 0% 0% 0% Energy efficient products 15.2 0% 0% 48% 1% 0% 36% 6% 0% 1% 0% 2% 0% 0% Low carbon services 0.6 0% 5% 0% 0% 0% 0% 2% 82% 8% 3% Low emission vehicles 7.0 0% 0% 87% 1% 1% 2% 0% 0% 8% 1% 0%

Professor Martin Freer, Director, Birmingham Energy Institute, University of Birmingham

Across the West Midlands there is universal commitment to delivering net zero on a timescale which aligns with, and sometimes is vastly more ambitious than, the 2050 UK target. The West Midlands Combined Authority has set a target of 2041. The ambition has been backed up by a high level plan. This will require significant investment, with an estimated £4.7bn in the first five years and £15.4bn by 2041. A similar review by Leeds City Council estimates £2.6bn a year for 10 years is required for net zero. However, these plans are probably at the lower end of the regional investment required, focussing on local authority controlled assets, and a more accurate reflection of the cost of decarbonisation is revealed by the estimated cost of decarbonising London’s 4 million homes of £98 billion.

Indeed, decarbonisation of domestic heating lies at the more challenging end of the spectrum given that there is not a low cost option and that unlike decarbonisation of the electricity grid, where large wind farm investments are invisible to the consumer, heat requires a change to virtually every home. The UK has 24 million gas boilers that will need replacing, and for many of these homes the thermal efficiency needs enhancing in order to be optimal for heat pump installation.

As illustrated in HM Government’s Heat and Building Strategy, the West Midlands has the highest levels of fuel poverty in England at 17.5% compared to 7.5% in the South East and the lowest levels of energy efficiency of buildings of 35% again compared to London and South East of 45%. At the time of extreme energy prices, driven by the present high cost of gas, this means that the West Midlands is greatly exposed to the accelerated levels of fuel poverty and has homes which leak energy at the highest rates and hence cost more to run.

The bottom line is, that both from net zero and the cost of energy perspectives there is a need to prioritise investment into the domestic heating sector and in turn this would provide a much needed injection into the West Midlands Green Economy.

The need for local coordination around heat is clear. Be it heat pumps or district heating both require engagement with communities around the type of heating solution deployed, the infrastructure required and an aggregation of demand to a scale that there it is commercially attractive to deliver. It is unlikely that a pepper pot of solutions will work and that the optimal approach is street by street, community by community. It will also need to recognise existing energy assets which have hitherto not been exploited.

East Birmingham is a good example. It is an area of Birmingham in which there are communities at the extreme end of the energy crisis. The fuel poverty and unemployment rates are highest and the life expectancy of certain communities is 10 years less than elsewhere in the city. The traditional, pre 1900, housing is some of the worst performing in terms of the Energy Performance Certificate, EPC, ratings. In total there is around 110,000 homes for which a range of district heating and heat pump solutions are on the table.

East Birmingham has a number of energy assets, which include the large energy from waste, EfW, plant at Tyseley which incinerates the cities household waste, generates electricity, but wastes the heat. Similarly, there is the Minworth, Severn Trent, sewage works which produces, from the final effluent stream, an estimated 95 MW of thermal energy. These assets produce enough thermal energy that they could, in principle, serve the energy requirements of 50% of the homes in East Birmingham.

A recent policy commission led by Sir John Armitt makes the case that regions like East Birmingham could be part of a national pathfinder programme. This pathfinder would not only deliver lower carbon energy, higher energy efficiency and reduced fuel poverty, but generate jobs and skills for the communities which are part of the pathfinder a virtuous circle. The proposed 3 Cities programme, which focusses on 150,000+ homes of the cities of Birmingham, Coventry and Wolverhampton, would similarly accelerate the economic benefits of the low carbon transition.

17

The key to the Green Economy is making sure that the benefits to the growth in this sector flow through to the communities in the West Midlands and not to the South East, or worse, overseas. The discussions that the West Midlands Combined Authority are having with HM Government around devolution are going to be important to success.

18

Kelvin Humphreys, Policy and Data Analyst, City REDI, University of Birmingham

The latter half of the past decade has certainly thrown up some challenges which, although not unique to Birmingham, acutely affected the region more so than others. The effects of the pandemic and now energy crisis look set to remain for at least the short to medium term, whilst the implications of Brexit will continue into the long term.

Despite these challenges, the United Kingdom’s ‘second city’ holds great promise. At the heart of UK manufacturing, with a large business and professional services sector, growing tech, health and digital sectors, all supported by leading higher education institutions, the region is well positioned for future growth. Not least in industries that have potential to create high skilled, well paid and good quality jobs, but also that hold potential to tackle climate change and other pressing societal issues. All of this is underpinned by large scale investment into sustainable housing, transport and commercial development. Evidence of this can be seen across the city on a massive scale, from the Peddimore employment park in the north east to the regeneration of Longbridge in the south west, but also in the surrounding towns and cities.

Perhaps nowhere exemplifies the scale of potential better than the east of the city region which stands at the nexus of green growth through major investments into clean energy, vehicle electrification, mixed use development at Arden Cross and sustainable transport infrastructure, including HS2.

The east of the city region, comprising East Birmingham and North Solihull, has been long been home to Jaguar Land Rover, Birmingham Airport and the NEC. Over the past decade it has seen the emergence and growth of Tyseley Energy Park (TEP), located within the Tyseley Environmental Enterprise District (TEED), which is at the forefront of efforts to decarbonise the city and drive green growth. TEP is home to a cluster of waste, green energy, and low carbon vehicle systems innovation activity centred on the Birmingham Energy Innovation Centre (BEIC) led by the Birmingham Energy Institute. It is also the site of the UK’s first multi fuel, open access, low and zero carbon fuel refuelling station including hydrogen used to fuel buses in the West Midlands.

Although the area is already well served by road and rail, huge investment into transport infrastructure, including High Speed 2 rail, Sprint bus routes and future extension of the Metro network through East Birmingham to Solihull, will make it one of the best connected in the country. The HS2 Interchange Station, the first railway station in the world to achieve a BREEAM ‘Outstanding’ certification for sustainability, will open up high speed rail connectivity with London, Manchester and the north of the country bringing communities and opportunities closer together.

The massive scale of investment has opened up the possibility of developing a 140 hectare mixed use innovation and enterprise focused development, to be served by the future Interchange Station, at Arden Cross. The vision for the masterplanned site aims to create a highly sustainable and innovative, advanced economic hub for the Midlands, creating jobs, opportunities, technologies and skills needed for the future. The internationally significant development has potential to attract substantial inward investment and talent to the region.

By leveraging infrastructure, location and existing assets whilst maximising on opportunities for growth the east of Birmingham is setting the stage for future sustainable growth for the benefit of the city and beyond.

19

Kuran Singh, Policy Adviser, Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce

What is a Green Economy?

A Green Economy is a low carbon, resource efficient economy that drives growth in employment through investment into infrastructure and assets that enable reduced carbon emissions and pollution. A Green Economy is an economy that encompasses the principles of sustainability.

Analysis from Deloitte shows a shift towards a Green Economy in the UK will create a significant number of new jobs highlighting the potential of the Hydrogen sector in creating 8 10,000 new jobs by 2030 and potentially 100,000 jobs by 2050. The future of the economy lies in green jobs, something Deloitte recognise highlighting the fact that green jobs increased by 8% from 2021 2022 compared to total UK employment which only increased by 0.5%. This is significant as not only does it show a shift towards a Green Economy, but it also shows how the Green Economy has fuelled the post pandemic recovery.

Birmingham’s Green Economy

Birmingham is a region committed to being at the forefront of the Green Economy. The low carbon sector is continuing to grow within the region. Indeed, Greater Birmingham and Solihull LEP’s (GBSLEP) Low Carbon and Environmental Goods and Services (LCEGS) sector was worth £6.3bn to the GBSLEP’s economy in 2019/20, indicated by the value of sales in the sector. These sales were generated by over 2,800 businesses that employed 48,000 people in the sector in 2019/20 as highlighted by Sustainability West Midlands. Furthermore, employment across GBSLEP’s Low Carbon and Environmental Goods and Services sector in 2019/20 was 48,322, which increased from 41,408 in 2017/18. It’s clear that the Green Economy has significant value to Birmingham, with increasing levels of jobs, businesses and investment being seen across the region.

There are numerous practical examples of Birmingham and its commitment to the Green Economy. For example, Tyseley Energy Park (TEP) is at the centre of energy innovation in Birmingham and the West Midlands, stimulating and demonstrating new technologies and looking to turn them in to viable energy systems that will contribute to Birmingham’s commitments to reduce CO2 emissions by 2030.

Birmingham and its commitment to climate change

Birmingham’s commitment to climate change has been consistent in its actions. In June 2019 the council declared a climate emergency and committed to reduce the city’s emissions, limiting the impact of the crisis. Birmingham aims to become net zero carbon by 2030. This is the city’s ‘route to zero’ (R20). Not only is a strong and promising Green Economy emerging, but the Commonwealth Games are also expected to have been the most sustainable games yet with organisers anticipating that the games were carbon neutral. Furthermore, Birmingham introduced the Clean Air Zone which is in operation all year round the clean air zone targets an area where action was needed to improve air quality by penalising the use high polluting vehicles.

Not only is the city looking to become more carbon neutral, it’s important to note the efforts being made to make the region a greener place to live. The Smithfield redevelopment are planning to ensure a greener site with over 500 trees and a range of vegetation suited to the Birmingham climate. Ambitions for a greener city were also seen in the redevelopment of Perry Barr with plans to improve access to the natural environment and support engagement with nature, on top of the zero carbon and energy efficiency measures that were adopted in infrastructure development.

Climate change is a hugely important matter that cities across the world have to deal with. Birmingham is a city at the forefront of sustainability efforts with plans being built around

20

sustainability initiatives, and action being taken. Combined with a thriving green economy, it’s clear that the future of the city is green.

21

Higher Education

Birmingham’s global reach extends beyond tourism and culture. The city is home to five of the UK’s best teaching and research led universities, most of which are attended by significant numbers of overseas students. The UK has a world leading higher education sector which is a major exporter of services. UK revenue from education related exports and transnational education activities grew to £23.3billion in 2018 with higher education accounting for 69% of the total, representing an increasing share.19

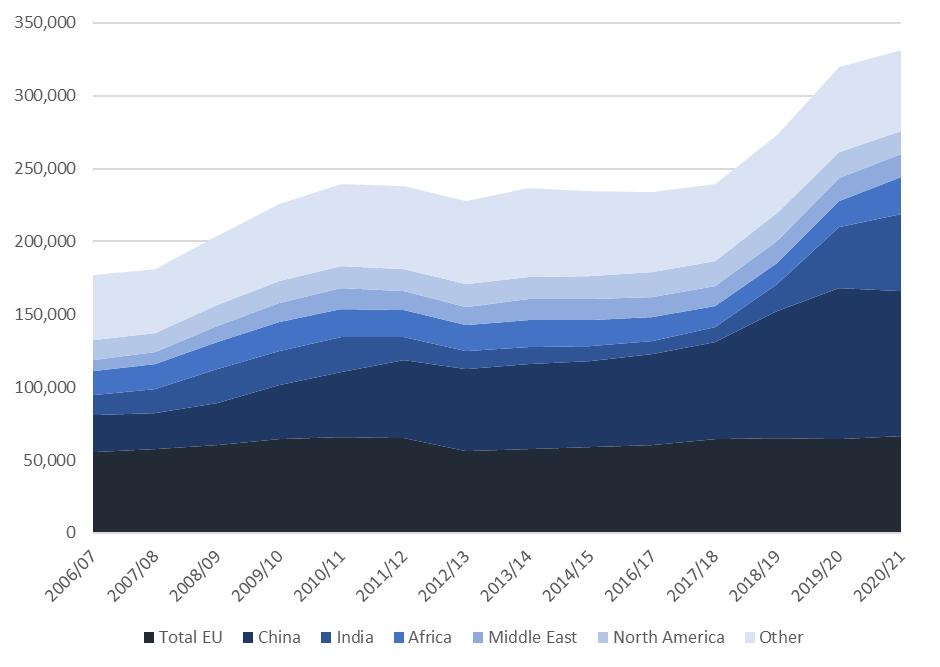

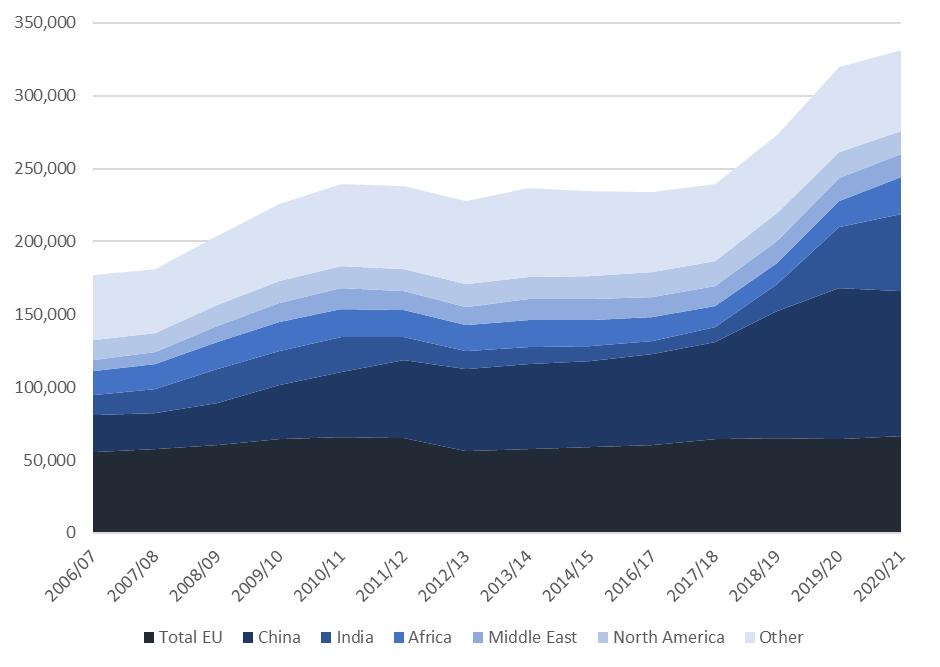

An increasing number of overseas students are choosing to study at UK universities. Whilst the number of students from EU countries is relatively stable, the number of students from China and India, and to a lesser extent the Middle East, has increased significantly in recent years. This partly follows a change to visa and immigration rules, announced in 2018/19 and coming into effect in July 2021, that allows international students two years to find work after graduation, or three years for PhD graduates.20 A memorandum of understanding was signed between the Indian and British governments in July 2022 introducing mutual recognition of academic qualifications. The move is expected to lead to further international student enrolment in UK universities.21

In 2017/18, almost 10,000 Indian first year students were studying in the UK. By 2020/21 that number had grown more than five times to 53,000. There was also a jump in the number of students from China over the same time period, although numbers had already been rising over the past decade, reaching more than 100,000 in 2019/20.

First year non UK domiciled students (UK)

The number of non EU international students enrolled at Birmingham’s five universities has increased by 30% since 2017/18, rising from 14% to 16% of the total student count. The share of EU students has declined slightly from 5% to 4%, although this is the same level as in 2015/16.

One in five students enrolled across the city are international, with three quarters of those from outside the EU. Enrolment from international students is highest at University College Birmingham, and these are predominantly from EU countries, and The University of Birmingham, where more than one in five are from non EU countries.

22

Source:HESA,Chart6:FirstyearnonUKdomiciledstudentsbydomicileandacademicyear.

19 DfE, 2021, UK revenue from education related exports and transnational education activity [accessed September 2022] 20 University World News article, available here 21 DIT, 2022, Memorandum of understanding on academic qualifications between India and the UK

Student numbers by domicile status (Birmingham, 2020/21)

Total UK EU Non EU

Aston University 16,795 84% 3% 13%

Birmingham City University 28,995 85% 2% 12%

Newman University 2,845 99% 1% 0%

The University of Birmingham 37,750 75% 4% 21%

University College Birmingham 5,270 72% 19% 9%

Total 91,655 80% 4% 16%

Source:HESA,Table1 HEstudentenrolmentsbyHEprovider. Includesstudentsofallyears,levelsandmodesofstudy.

Universities have an important contribution to make to the levelling up agenda and local economic development through their research, teaching and engagement activities.

23

Professor John Goddard OBE, Professor of Universities and Cities, City REDI, University of Birmingham.

Notwithstanding national political changes, the challenges of ‘levelling up’ different cities and regions of the country will not go away. In this universities can and do play a leading role as ‘anchor institutions’ throughout the country with a huge sunk capital and social investment contributing to place making in the round Universities played a key role during the pandemic which was an economic as well as health crisis. They are even more significant as we enter yet another period of economic turbulence with widening geographical disparities. They are here for the long haul!

More specifically, universities are major employers in their own right, local procurers of goods and services. The activities of their staff and students have a direct economic, social, and cultural impact. Through collaborative research with business, public authorities, and the community and voluntary sectors, universities can contribute to innovation in all manner of organisations, including helping them confront global challenges like climate change locally. They can use their independent status and analytical insights to bring all stakeholders together in the co creation of knowledge. Through education they contribute to the skills needed to link research to innovation and ensure that students from less advantaged areas have access to local employment opportunities so that they do not need to move away. Last but not least, they have global reach and can help attract and inward investment to their city and region.

Evidence of the scale of the contribution of the universities in Birmingham can be found in our data lab where users can access information both about all universities AND their localities across England. From this source it is clear that the University of Birmingham exhibits many of the characteristics of an anchor institution, acting withandfor the City and wider region. It’s investment in establishing City REDI and the appropriately named Exchange building in the City Centre bear witness to this.

From within the University, City REDI is providing evidence to guide and evaluate the impact policies and practises that can contribute to long term local economic and social development. A good example of this is work with the Chamber using Foresight methodologies to identify megatrends that can be used to transform future challenges into opportunities for Greater Birmingham.

But activities like this must be sustained by government policy. To this end we have been seeking to shape the national discourse about the contribution that universities can make to levelling up. In this respect the Levelling Up White Paper is strangely silent, no doubt because of silos within central government between those departments responsible for research, innovation, higher education, and local government. So, we will be responding to the challenge issued by Lord Kerslake in a recent Policy Forum that we hosted using it to help us write ‘the missing chapter’ in the White paper

As many national politicians have said, every area of the country can engage with the levelling up agenda, provided they can put forward viable projects and demonstrate effective partnership and accountability arrangements. The national network of civic universities has shown that universities can play a role through Civic University Agreements drawn up with local partners. Experience with the process of preparing such agreements suggest that localities that are best prepared and most agile will gain most. Key ingredients everywhere are joint leadership between universities, business and local government in the delivery of planned investment. And doing this in consultation with the wider public. The partnerships between Birmingham City Council, the University of Birmingham, the other universities, the West Midland Combined Authority and the Chamber of Commerce indicate that we are well placed to address the levelling up challenges, including those of so called ‘left behind’ communities in our region.

24

The skills composition of the labour force plays a vital role in a region’s productivity, economic growth and innovation capabilities. In this context, creating the conditions for retaining highly skilled university graduates in an area can improve its workforce skills base and contribute to regional convergence. This becomes more important considering that the Covid 19 pandemic has exacerbated economic and welfare inequalities across the UK, while, in parallel, there is an increased policy interest in levelling up UK places22. To understand better the mechanisms that drive the mobility behaviour of highly educated people, it is important to shed light on the characteristics of graduates who stay in their area of study for work relative to those who choose to migrate to other places.

The Graduate Outcomes Survey provides comprehensive information about the employment destinations of those graduates who responded to the Survey for the academic years 2017/18 and 2018/19. Of the total number of UK domiciled graduates (i.e. who lived in the UK before commencing their studies) of the five universities in Birmingham who were in employment 15 months after completing their course, 53.1% stayed in the West Midlands for work (see the graph below). The rest of Birmingham graduates (46.9%) moved to other UK regions (or outside the UK), predominantly to London (14.3%), the South East (7.2%) and the East Midlands (5.8%).

Distribution of new graduate workers by region of workplace and university attended (in a grouped form)

25

Dr Kostas Kollydas, Research Fellow, City REDI, University of Birmingham and Professor Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development, City REDI, University of Birmingham

Note:Thegraphpresentsthedistributionofhighereducationgraduatesinemployment15 monthsafterfinishingtheircourseacrossworkplaceregions.ThesamplecomprisesonlyUK domiciledpeople(i.e.,thosewholivedintheUKbeforecommencingtheirstudies).The “universitiesinBirmingham”aretheUniversityofBirmingham,BirminghamCityUniversity, AstonUniversity,UniversityCollegeBirmingham,andNewmanUniversity. Source:OwnelaborationusingpooleddatafromtheGraduateOutcomesSurvey(Higher EducationStatisticsAgency),2017/182018/19. 22 Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (2022). Levelling Up the United Kingdom 14.3 0.7 4.1 2.4 5.8 53.1 4.3 7.2 4.4 1.4 0.6 0.2 1.5 23.2 3.4 10.3 7.2 5.7 5.8 6.9 11.9 7.2 4.5 8.6 2.8 2.6 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Universities in Birmingham Other UK universities %

By focusing on the metropolitan West Midlands County (i.e. the 7 Met area), the corresponding graduate retention rate stands at 44% (on average for both academic years). Interestingly, the following table reveals that the average characteristics of graduates of the five universities in Birmingham who work in the 7 Met area differ markedly from those who left Birmingham to access jobs elsewhere in the UK or in other countries. More specifically, women are more likely than men to stay in the 7 Met area for work. In particular, females comprise 65.2% of the 7 Met area workforce sample compared to 58.6% of the Birmingham graduates who migrated to other areas for work. A key factor here could be unequal interregional occupation opportunities between genders, particularly at the beginning of graduates’ careers23

Moreover, the likelihood of staying locally for work is lower for younger graduates (aged 24 years and under), who account for 60.4% of the Birmingham graduates employed in the 7 Met area relative to nearly 70% of those who migrated elsewhere for work. Likewise, first degree holders exhibit a lower propensity to stay in the 7 Met area for employment than those with other qualification levels.

There are substantial ethnic differences between these two groups of graduates. For example, of the total number of Pakistani and Bangladeshi graduates who studied in Birmingham, 73% remained in the 7 Met area after finishing their course. As a corollary, they comprise 17.2% of the Birmingham graduates who work in the 7 Met area, which is 12.3 percentage points higher than the respective share of those who found a job in other areas (4.9%). Some likely explanations for this pattern relate to the concentration of specific ethnic minorities in the West Midlands, their lower average socio economic and educational background, and cultural attitudes to long distance moves. Indeed, graduates with parents in highly skilled employment (i.e., holding managerial/professional jobs) are more likely than others to be geographically mobile. In a similar vein, academic performance is negatively correlated with the probability of staying in the location of study, as Birmingham graduates with a first class or upper second class degree have a greater chance of relocating to other regions/countries for employment.

The probability of staying local is considerably higher for Birmingham graduates with a degree in Arts, Humanities, and Education than those with STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) and LEM (Law, Economics and Management) qualifications. Finally, the Public Admin, Education and Health sectors in the 7 Met area absorb a remarkably large number of Birmingham graduates (57.9%) relative to those who move to other locations (41.6%). The latter results are attributable to different occupation opportunities across subjects of study and sectors emanating from the industrial structure in the 7 Met area.

Increasing graduate retention in the West Midlands could be achieved by improving the opportunities in sectors with auspicious growth outlooks that are adaptive to future skills needs. In this context, investing in growing sectors (such as advanced manufacturing, life sciences, low carbon, high tech and digital industries) can create good jobs in the West Midlands, thus both helping to retain and attract university educated talent to the area.

26

23 See

a further discussion in Carrascal Incera, A., Green, A., Kollydas, K., Smith, A. & Taylor, A. (2021). Regional brain drain and gain in the UK: Regional patterns of graduate retention and attraction. WMREDI

Average characteristics of graduates of universities in Birmingham by area of employment (7 Met area versus other areas)

Variable Other areas (%) 7 Met area (%) Differen ce

Gender

Women 58.6 65.2 6.6

Men 41.4 34.8 6.6

Agegroup

Under 21 2.9 3.2 0.3 21 24 67.0 57.2 9.8 25 29 12.3 16.8 4.5 30 39 8.4 13.2 4.8 40 49 6.2 6.9 0.7 50 and over 3.2 2.7 0.5

Ethnicity

White 70.6 55.8 14.8

Black Caribbean 1.9 4.2 2.3

Black African 5.6 5.9 0.3

Other Black 0.3 0.4 0.1

Indian 9.0 8.5 0.5

Pakistani 3.7 13.1 9.4 Bangladeshi 1.2 4.1 2.9

Chinese 0.9 0.8 0.1

Other Asian 1.9 1.8 0.1

Mixed 4.1 4.2 0.1

Other ethnic group 0.7 1.2 0.5

Socioeconomic background (parental occupation)

Managerial/Professional occupation 62.0 44.9 17.1

Other (including long term unemployed) 38.0 55.1 17.1

Subjectareaofstudy

STEM 43.5 41.6 1.9

LEM 23.8 19.0 4.8

Other 20.0 28.4 8.4

Combined degree 12.7 11.1 1.6

Levelofqualification

Postgraduate (research) 3.1 3.2 0.1

Postgraduate (taught) 25.9 29.2 3.3

First degree 65.5 60.1 5.4 Other undergraduate 5.5 7.5 2.0

Classoffirstdegree

First class / Upper second class honours 88.0 80.0 8.0

Other degree class 12.0 20.0 8.0

Industrysector(groupedform)

Energy and water 1.6 0.5 1.1 Manufacturing 6.6 3.3 3.3 Construction 1.6 1.8 0.2

Distribution, hotels and restaurants 13.9 12.3 1.6

Transport and communication 9.4 4.6 4.8

Banking and finance 20.4 16.0 4.4

Public admin, education and health 41.6 57.9 16.3

Other services 4.8 3.6 1.2

Observations 9,370

Note: The parental occupation applies only to young graduates (i.e., those aged 20 or less at the time of entry to higher education). The figures for the “Agriculture, forestry and fishing” industry sectors are not reported because of their small sample size. STEM subjects comprise “Physical sciences”, “Mathematical sciences”, “Computer science”, “Biological sciences”, “Veterinary science”, “Engineering & technology”, “Agriculture & related subjects”, and “Architecture, building & planning”. LEM subjects refer to “Law”, “Business & administrative studies”, and “Social studies”. Other subjects include “Mass communications & documentation”, “Languages”,

27

7,360

“Historical & philosophical studies”, “Creative arts & design”, and “Education”. The “combined” subjects relate to joint degrees in more than one subject code (e.g., “BSc in Economics & Mathematics”).

Source: Own elaboration using pooled data from the Graduate Outcomes Survey (Higher Education Statistics Agency), 2017/18 2018/19.

28

Connect. Support. Grow. Contact Us: For queries related to the Birmingham Economic Review 2022 please contact: Emily Stubbs Senior Policy and Projects Manager Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce E.Stubbs@birmingham-chamber.com Kelvin Humphreys Policy and Data Analyst City-REDI, University of Birmingham K.Humphreys.1@bham.ac.uk Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce 75 Harborne Road Edgbaston Birmingham B15 3DH T: 0121 274 3262 E: policy@birmingham-chamber.com W: greaterbirminghamchambers.com