2022

3: People: Challenging Times

Connect.

Birmingham Economic Review

Chapter

Support. Grow.

Introduction

The annual Birmingham Economic Review is produced by the University of Birmingham’s City REDI and the Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce. It is an in depth exploration of the economy of England’s second city and a high quality resource for informing research, policy and investment decisions.

This year’s report provides comprehensive analysis and expert commentary on the state of the city’s economy as it emerges from disruption caused by the pandemic into a new period of high inflation and uncertainty. The Birmingham Economic Review assesses the resilience of the city, its businesses and its people to the set of challenges stemming from the UK’s vote to leave the EU, the coronavirus pandemic and now the energy crisis. It includes an update on the development of the region’s infrastructure and highlights opportunities for growth, building on existing strengths and assets.

The most recently available datasets as of 30th September 2022 have been used. In many circumstances there is a significant lag between available data and the current period. Contributions from experts in academia, business and policy have been included to provide timely insight into the status of the Greater Birmingham economy.

Report Geography

The report focuses on the ‘Greater Birmingham city region’ defined by the boundaries of the Greater Birmingham and Solihull Local Enterprise Partnership (GBS LEP). The GBS LEP area consists of the following local authorities: Birmingham, Solihull, Bromsgrove, Cannock Chase, East Staffordshire, Lichfield, Redditch, Tamworth, Wyre Forest.

References to the ‘West Midlands region’, or ‘West Midlands (ITL1)’, are to the large scale region at International Territorial Level 1 (ITL1). There are nine ITL1 regions in England: North East, North West, Yorkshire & The Humber, East Midlands, West Midlands, East of England, London, South East and South West in addition to Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. Note that ITL recently replaced the EU’s Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics (NUTS). Geographies of ITL and NUTS territories generally correspond except for minor differences at local authority level outside the Midlands.

References to the ‘West Midlands metropolitan area’ are to the West Midlands county comprising seven metropolitan districts (WM 7M): Birmingham, Solihull, Coventry and Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall, Wolverhampton.

References to the ‘West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) area’ are to that administered by the Combined Authority.

Note that figures may not always total exactly due to rounding differences. Figures in some tables may be undisclosed due to statistical or confidentiality reasons.

1

Foreword and Welcome

Chapter 1. Economy: Crises and Resilience

Chapter 2. Business: Disrupted Markets

Chapter 3. People: Challenging Times

Chapter 4. Place: Connecting Sustainable Communities

Chapter 5. Opportunity: Building on Strengths

2 Index

People: Challenging Times

Recent years have proven challenging for residents and workers of the region. The pandemic poised a challenge to health and social wellbeing as well as economic activity. Brexit caused uncertainty and heightened tensions. Now the cost of living crisis is placing a squeeze on household incomes that threatens to tighten further. These challenges have more acutely affected the region and its most vulnerable inhabitants than many other places.

Although the region’s labour market has demonstrated remarkable resilience whilst rising skills and wage levels continue to close the gap on national averages, there are long standing and deep rooted challenges being made more difficult by the circumstances.

Greater Birmingham is a region of great diversity and talent. However, it is also one of relatively high levels of deprivation, poor health and worklessness. Economic forces, such as globalisation, technological change and de industrialisation, have not benefitted everywhere equally and have widened spatial inequalities within and between Greater Birmingham and other regions. The most vulnerable groups are less well equipped to cope with the challenges brought on by the pandemic and cost of living crisis, highlighting the need for levelling up with a focus on both place and people.

This chapter reviews the state of the region’s populace, including demography, health, employment, skills, pay and deprivation.

Demography

According to Census 2021, more than two million people, representing 3.6% of England’s population, live in Greater Birmingham. More than half of the city region’s residents live in Birmingham whilst 17% live in Solihull. Oxford Economics has forecasted the population to increase by 2.7% to more than 2.1m people by 2040.

The population is relatively young and diverse, especially in Birmingham where 21% of residents are aged between zero and 15 years and 66% are of working age (16 64 years) compared to 17% and 64% respectively for England. Almost one in two residents in Birmingham belong to an ethnic minority group compared to 16.2% nationally and more than one in four were born overseas compared to 15.9% across England. The city is home to over 180 different nationalities and is the youngest in Europe.

3

Population statistics (2021)

Birmingham Solihull GBSLEP England

Total population 1,144,900 341,900 2,058,400 56,489,800

Age 0 15 (% of total) 21% 18% 19% 17%

Age 16 64 (% of total) 66% 61% 64% 64%

Age 65+ (% of total) 13% 21% 17% 18%

Males (% of total) 49% 49% 49% 49%

Females (% of total) 51% 51% 51% 51%

White (%) 50.9% 86.1% 69.0% 83.8%

Ethnic minorities (%) 49.1% 13.9% 31.0% 16.2%

Born overseas (%) 25.9% 10.0% 18.2% 15.9%

Source:Population,ageandsextakenfromCensus2021. EthnicityandorigintakenfromNomis, Annualpopulationsurvey(2021).

4

Yetunde Dania, Chair, West Midlands Race Equalities Taskforce

The key to any business is understanding your market and addressing barriers to success. So why are we, in some areas falling short as a city, region and nation to do this when it comes to addressing inequality and discrimination in the labour market?

According to the 2011 census, around 30 percent of people living in the West Midlands are identified as being from an ethnic minority background and 1 in 3 are aged 25 years and below. These proportions are even greater for the city of Birmingham, where 40 percent are aged under 25 and just under half of the population are from ethnic minority backgrounds. The release of the 2021 census ethnicity data later this year will reveal a further different picture as it is highly anticipated Birmingham will officially become a ‘majority minority’ city.

We rightly recognise this youthful and diverse makeup as a huge source of economic potential and core to our identity as a vibrant, enterprising and dynamic place to live and worth of celebration. However, how do we tally this with the reality that access to opportunity is unequal, and what does that mean for businesses and leaders like you?

As Chair of the West Midlands Race Equalities Taskforce, I have a vision that across the region, race, ethnicity and heritage should never be obstacles to people having a fair start in life or the opportunity to reach their full potential and flourish. Unfortunately, this is not currently the case.

The data is clear. People from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to experience unemployment, deprivation and lower household income after bills.

The headline figure is an 11 percentage point difference between the employment rates for White people compared to those from all other ethnic groups (2019). While the overall race unemployment gap has reduced since 2004, there have been increases in unemployment rates for some communities, including Pakistani, Bangladeshi and White other groups.

Disparities were reflected by the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic. Young people were among the hardest hit and the reduction in employment rates was 4 times higher for Black young people than their white counterparts. This is the youthful and diverse population we hope to champion!

Race disparities in work cannot be explained away by context or qualifications.

Research from the Institute of Fiscal Studies (2021) has revealed that second generation men and women of Black Caribbean, Bangladeshi and Pakistani heritage are more likely to be more highly educated than their white counterparts, but less likely to be employed. Other studies point to the impact of discrimination in hiring processes, from bias in recruitment and selection to inequitable approaches to the advertising vacancies.

When talent does not guarantee opportunity, inequality in the labour market and working practices are not only damaging to society but carry a heavy opportunity cost for our regional economy.

To put a number on it, the 2015 McGregor Smith review of race in the workplace quantified that having full representation of ethnic minority workers would unlock £24 billion of benefit for the UK economy each year. Imagine what that could mean for the economy of Birmingham and the West Midlands!

At a regional scale, the Race Equalities Taskforce will work with a wide range of stakeholders to address disparities including within jobs and skills. We have already demonstrated that the ‘Levelling Up’ agenda is dependent on unlocking the potential of our minoritised communities who face additional barriers to success. The Taskforce has secured commitment from the West Midlands Combined Authority’s policy leads that opportunities created through further devolution will be used to advance equality and Inclusive Growth.

5

However, the opportunity cost of inequality in the labour market also impacts businesses directly as a barrier to recruiting, retaining and unleashing local talent.

As Partner and Head of the Birmingham Office at Trowers & Hamlins, I am incredibly proud of our commitment and the progress we are making in delivering our Race Action Plan. This is a ‘living’ strategy owned by the partnership and is embedded in our corporate policy, our recruitment practices, our progression opportunities, our learning and development, and data collection. It is a firmwide commitment that we continually challenge ourselves to make equity a reality across our business.

When the eyes of the world were focused on the Birmingham Commonwealth Games 2022, we celebrated the diversity of our City and region. We must ensure a legacy so that by the time we hopefully host the Olympic Games in 2033, the experience of our diverse communities is more inclusive in every way as this will unlock benefits for us all.

6

Karl George MBE, Partner and Head of Governance, RSM

“The time for talking is over, it’s time to act.” That was the McGregor Smith Review soundbite, when its final report considering the issues affecting black and minority ethnic groups in the workplace was published over 5 years ago. Note the following quote from the report: “For decades, successive governments and employers have professed their commitment to racial equality yet vast inequality continues to exist. This has to change now. With 14% of the working age population coming from a Black or Minority Ethnic (BME) background, employers have got to take control and start making the most of talent, whatever their background.”

This is a lost opportunity. Inequality or underrepresentation is lost opportunity, not engaging with such a significant part of the population is lost opportunity, missing out on the talent and contribution is lost opportunity.

Well, let’s pause and take a look at Birmingham in 2022. The city is one of the UK’s most diverse, soon to be a minority/majority city. It is presented with, yes, many deep rooted challenges, but also many great opportunities as it embraces its superdiversity. Consider some statistics

• Economic activity within ethnic minority groups (35.5%) is almost double that of white individuals (18.8%) and there is a much bigger gap between males and females. The picture differs amongst ethnic groups, with Pakistani and Bangladeshi individuals having the highest rate of inactivity 43.4% particularly for females 62.9%.

• We have a young and diverse population. 46% of the city’s residents are aged between 0 29 (UK average 36.2%) and 1 in 4 were born outside the UK (UK average 14.3%). The share of residents classed as ethnic minority (48.5%) is much higher than the nation as a whole (14.3%).

• The business, finance and professional services sector is the largest contributor to the Greater Birmingham economy with GVA of £17.2 bn (31% of the total) and 206,200 jobs (21% of the total); Birmingham and its immediate surroundings host several nationally and internationally significant companies. Yet only negligible % of senior leadership in the region is from a black and minority ethnic background.

We must tackle the stubborn lack of representation across the work force, particularly in the board and senior leadership team, if we are ever to benefit from the opportunities that we find.

This isn’t about the law Diversity 1.0 eliminating discrimination, advancing equality of opportunity and fostering good relations. The Equality Act 2010 legally protects people from discrimination in the workplace and wider society. We have moved on from compliance.

This isn’t about the fair, moral or nice thing to do Diversity 2.0. As a result of race awareness training and attention to corporate social responsibility there was an era of organisations aspiring to do the right thing. The Triple Bottom Line being the mantra: people, planet, prosperity. We have moved on from this, whether or not it ended up as the ‘greenwashing’ seen in other sectors.

Diversity 3.0 gives us the business case. Since McGregor Smith we have read the reports from McKinsey and Co and others demonstrating the correlation between ethnic and gender diversity and profitability. So, we have known about the business case for some time but there’s still something missing.

In order for the Birmingham economy to fully benefit from its superdiverse demography we must do three things which, taken together, I call Diversity 4.0.

1. Publish our ambitious but realistic targets on representation in board and leadership teams, ensuring that we match the higher of workforce or local demographic and create accountability for the achievement of those objectives.

2. Review the way things are done in our organisations. Where there is evidence that the culture and/or policies adopted have unwittingly led to bias, discrimination or unfairness

7

in in job advertisement, recruitment, promotion and progression and retention, changes must be made.

3. No Excuses if there are no reasons for a disparity to exist when we look deeper into the data, then a “no excuses” approach must be taken to addressing the inequality.

We are at a tipping point in history; the pandemic, “me too” and the Black Lives Matter movement created an awareness, empathy and momentum for us to collectively make a difference. A sustained and concerted effort from all of us to tackle the lack of representation of diverse communities will see a significant boost the Birmingham economy just some of which are proposed below.

• Maximisation of the innovation and creativity of younger generations.

• Varied perspectives from a more diverse workforce and its leaders.

• Less Group Think and Silo Thinking leading to better decision making.

• Companies attracting, supporting and retaining talent and getting better engagement from their workforce.

• Reputational capital by nurturing aspirations from a diverse group of talent not normally utilised.

If we get Diversity 4.0 right, Birmingham and the companies, organisations and individuals that call it home will be better equipped to problem solve and innovate, gaining deeper insights from a wider variety of stakeholders. The future is bright!

8

Deprivation

The city and region suffer from high levels of deprivation as measured using the 2019 English Indices of Multiple Deprivation. Of the 1,192 lower super output areas (LSOAs a geographic area used for statistical purposes) in the Greater Birmingham area, 298 (25%) are in the top 10% most deprived nationally. Most of these (264) are in Birmingham city meaning 41% of the city’s LSOAs are in the top 10% most deprived nationally.

Greater Birmingham scores poorly across all seven domains of deprivation, but particularly on income and employment where a disproportionately high number of LSOAs sit in the bottom decile nationally. The scores also indicate significant barriers to housing and services and poor living environments as over 50% of LSOAs score within the bottom 30% of all areas nationally. There are also many LSOAs in the least deprived deciles highlighting spatial inequalities across the city region.

The government’s Levelling Up White Paper acknowledges spatial inequalities and aims to close the gaps in economic, social and environmental conditions at local and national scales. Doing so will improve wellbeing whilst also increasing resilience and productivity of the region and nation as a whole.

Number of Greater Birmingham LSOAs by index of multiple deprivation decile

Source:MHCLG,Englishindicesofdeprivation,2019.

9

Simone Connolly, Chief Executive Officer, FareShare Midlands

FareShare Midlands is the region’s largest food redistribution charity, turning an environmental problem into a social solution. With 8.4m people in the UK struggling to afford to eat, and 131,000 children living in poverty in Birmingham alone, its core mission has never been more vital.

FareShare Midlands takes good quality surplus food from the food industry into one of six warehouses across the region, where a dedicated army of staff and volunteers sorts and records the food.

The teams then redistribute the food to Community Food Members (CFMs). CFMs are local charitable and community organisations who tackle hunger, poverty and the escalating effects of the cost of living crisis.

This has been another challenging year. The amount of food redistributed has grown to 7,185 tonnes reaching over 60,000 people every week. Last year this food helped over 550 frontline groups provide 16 million meals. A typical member of FareShare saves around £7,900 from their food budget each year, and 87% say the savings they have made by being a CFM has enabled them to reinvest into other support services for their community.

CFMs include community centres, pantries and community cafes, colleges and training centres, schools and childcare facilities, homeless and youth shelters, faith organisations, drop in centres and food banks:

• 30% of CFMs are dedicated food services

• 23% of CFMs operate as a community centre

• 15% of members are a school, college or after school/breakfast club.

These organisations are helping a vast range of people from diverse cultural, societal and economic upbringings including asylum seekers, migrants and refugees, children and adults with disabilities, domestic violence survivors, disabled and/or elderly people, and people struggling with mental health issues

The ways the food supplied by FareShare Midlands is used are varied, though the charity saw a sharp rise in food banks accessing the service during the height of the COVID19 Pandemic. The organisation is now seeing more CFMs return to cooking with the food and inviting their beneficiaries in to eat communally. These CFMs aren’t just feeding people in need; the vital support they provide to their local communities includes:

• activities, training and community support such as food preparation and cooking skills

• budgeting advice and initiatives to improve financial awareness and planning

• liaison with health visitors, medical organisations and family services

• mentoring young people

• baby banks, school uniform banks, clothing and household items

By 2019, vulnerable families and individuals were already unable to afford to put basic food on the table and the Pandemic only exacerbated this. By the start of 2022 people already living in poverty found themselves facing the challenges of the current cost of living crisis.

Furthermore, this crisis has resulted in an escalation in the needs of the CFMs. They are having more people coming into their services and they are increasingly turning to FareShare Midlands to ask for more food. New community organisations are opening and making enquiries about membership, in efforts to do more for local people in need. However, FareShare Midlands is struggling to meet all of these growing needs, with the food industry in turmoil caused by the impact of Brexit, COVID19 and the war in Ukraine.

This is not deterring FareShare Midlands and, where it can, the charity is investing in innovations to enable accepting more difficult to re distribute foods. The organisation recently launched innovations in meal production and food processing units.

10

To help FareShare Midlands respond to increases in demand, the charity needs urgent support more than ever. The organisation needs local people with spare time and a passion for food and the environment to take part in rich and rewarding volunteer opportunities. The charity desperately needs more food as its teams work harder than ever to encourage food companies to divert their surpluses to it.

Recent quotes from CFMs about the impact of the cost of living crisis: Jane, from Stokes Wood School “As the cost of living continues to soar, Stokes Wood predicts the need for our services will only increase. Our pastoral team are already lookingintohousingsupport,andmanyfamiliesareapplyingforschooluniformfunding”.

Millie, Love Your Neighbour “ThesurplusfoodwereceivefromFareShare Midlandsbenefits somanymembersofourlocalcommunity.Unfortunately,duetotherecentincreasesin the cost of living, we have seen more families the past few weeks and people who hadn’tbeenforalongtimearecomingback”.

Martin, E2 “We have families that we know would be struggling if they didn’t use our service.Theriseinthecostsofelectricityandgasarestartingtobitenow,andweexpect andarereadyforanexpansionofthefoodpantryservice.Weonlyrunitonedayaweek atthemoment,butwearepreparedtorunitonotherdays.Theexpectationisthatinthe short to mediumtermtheneedforthefoodpantrywillincreasesignificantly.”

Lucy, Brushstrokes “The project went from supporting around 27 households pre pandemic, to over 100 households a week during the height of COVID. In the last 6 months,thisfigurehaddroppeddowntoaround70,howeverrecentlythisfiguremoved backuptowards100again.Thisisbecausethecostoflivingisincreasingandthepeople theyaresupportingarefindingthingsharderoncemore”.

11

Fuel Poverty

The West Midlands (ITL1) region has the highest incidence of fuel poverty of all English regions at 17.8% compared to 13.2% of all households across England, based on the Government’s low income, low energy efficiency (LILEE) definition. In Greater Birmingham 18.2% of households live in fuel poverty, although they are not distributed evenly across the city region. More than one in five households in Birmingham city are fuel poor compared to 11.7% in Bromsgrove.1

Fuel poverty is not equally distributed across the city region. More than one in five households in Birmingham are fuel poor which is almost twice the proportion in Bromsgrove.2

Regional fuel poverty (2020)

Number of households

Households in fuel poverty Proportion in fuel poverty %

Birmingham 443,703 96,795 21.8%

Bromsgrove 41,313 4,841 11.7%

Cannock Chase 43,830 7,246 16.5%

East Staffordshire 50,944 8,333 16.4%

Lichfield 44,529 5,665 12.7%

Redditch 37,413 5,405 14.4%

Solihull 92,889 11,637 12.5%

Tamworth 34,163 4,910 14.4%

Wyre Forest 46,357 7,258 15.7%

GBSLEP Total 835,141 152,090 18.2%

WM (ITL1) 2,477,936 441,693 17.8%

Source:BEIS,Subregionalfuelpoverty,LowIncomeLowEnergyEfficiency,2020data.

Prior to the Energy Price Guarantee capping bills for a typical household at £2,500, it was feared that two thirds of UK households, equivalent to 45m people, would be trapped in fuel poverty this winter by escalating fuel costs. Whilst the cap will bring some relief and certainty to households for the next two years, energy bills are still expected to be double what they were just a year ago. The hike in energy prices will not have equal impacts for all households, with more vulnerable and already struggling households, including lone parents and pensioners, set to face more pressure.3 The £15bn Cost of Living Support package announced in May 2022 offered only partial help to vulnerable groups.

Fuel poverty in Birmingham is partly attributable to the poor energy efficiency of the housing stock. Birmingham has a low average Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) score of 63 compared to 66 across the whole of England. Only one in three properties in the city have an EPC Band of C or above compared to 42% nationally.4

BEIS, Fuel poverty detailed tables 2022 (2020 data)

BEIS, Sub regional fuel poverty data 2022 (2020 data)

The Guardian article, available here

ONS, Energy efficiency of Housing, England and Wales, country / local authority (November 2021)

12

1

2

3

4

Dr Sara Hassan, Research Fellow, City REDI, University of Birmingham

In October 2021, the UK Government lifted the energy cost cap which meant that the average usage household on a standard tariff would expect their annual bill to increase but even more so for people with pre payment meters. This came as a shock announcement in the context of the already increased cost of living and the overall rise of costs throughout the pandemic5. The households most affected by the rising energy cap are those who spend the highest proportion of their budgets on energy. Those particularly at risk are families with children, especially lone parents, and those in rented accommodation The rise in the energy price cap will

significantly impact households within the West Midlands, compared to other regions. This is due to a greater proportion of fuel poverty amongst its households compared to other regions: 17.8% of West Midlands households are considered to be fuel poor compared with 13.2% across England6 The energy crisis has a profound impact on business and societal impacts in the West Midlands.

The energy crisis further exacerbates economic inequality which is heavily present at individual and societal level with additional fuels injustice. For example, a July 2022 report7 found that low income families will hand over 26% of their income after housing costs in 2023/24 to pay for gas and electricity compared to just 12% two years previously. However, middle income families will only use 11% of their income meeting the same costs, a rise from 4%. In some cases, some households will need to spend two thirds of their income on energy bills next year. A single, childless, working age person on a low income can expect to pay 67% if they consume the same amount of energy as in 2021/22.

Further breakdown of these estimates, shows that low income families are already facing a “year of financial fear” as JRF states it. These household will be faced with an impossible choice of living in a cold home, going without something else essential, getting behind with bills or getting into debt. Moreover, households on the lowest incomes and those with people with a long term illness or disability that reduces their ability to work have seen their income drop by over £1000 per year, due to changes in Universal Credit. With inflation soaring at its highest rate in 40 years, benefits claimants’ income is being reduced every day. Over three quarters of the increase in inflation is due to the relentless surge in energy prices, which places the biggest burden on the shoulders of the poorest households. However, the UK Government has provided a package of support which seems to cover all the October increase for all recipients of means tested benefits, as well as approximately half of the April increase. While, the scale of the response is broadly in line with the scale of the problem for this winter. Analysts, however, estimate that bills could stay high beyond this winter. In September 2022, the government introduced the Energy Bills Support Scheme (EBSS) which is a more targeted approach to provide support for households, instead of relying on a series of “one off” measures. Households will see a discount of £66 applied to their energy bills in October and November, rising to £67 each month from December through to March 20238

However, with bills almost doubling the support scheme is not as progressive particularly for low income households. Other policy options are still needed to target the energy crisis and accompanied fuel poverty identified by a number of agencies and charities9. Firstly, exploring deeper price protection options or a new social tariff for low income energy customers. Such a tariff must be additional to existing schemes, mandatory for all suppliers, targeted at those most in need, reduce the costs of eligible households and use auto enrolment. This may need new Government legislation so that it can sit alongside the price cap. Secondly, quickly managing the

13

5 West Midlands Economic Impact Monitor, 2022, Inflation and cost of living 6 West Midlands Economic Impact Monitor, 2022, National and Regional issues 7 Joesph Rowntree Foundation, 2022, JRF analysis energy 8 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, 2022, Energy Bills Support Scheme 9 National Energy Action, 2022, Policy Brief

repayment of utility debts across the UK to provide financial support for households that have a debt repayment plan with their energy supplier. With Government matching every £1 paid by the customer by £1 of Treasury funding which would cost £500m per year. Thirdly, accelerating the improvement of energy efficiency in fuel poor homes. This can be achieved through passing legislation for ECO4, committing the remainder of funding promised to upgrade fuel poor homes and settling in regulatory minimum energy efficiency standards for rented properties. Other options include considering removing VAT or policy costs from energy bills.

While the issue of fuel poverty and current energy crisis can affect society as a whole, people's perception of the fuel poor is mainly governed by the media and mainly concentrates on individuals10. The effects of fuel poverty contribute to social isolation, mental and general health impacted by an insufficient heating of homes. This puts a strain on the welfare required to keep individuals and families out of the fuel poor bracket, increasing pressure on local and NHS services. People on fixed and low incomes will struggle to incorporate the increase in their utility bills of inefficient home. This further hurdles future regeneration and community engagement aspirations.

14

10 Community Action on

Fuel Poverty,

2019, Effects on Communities

Gross Disposable Household Income

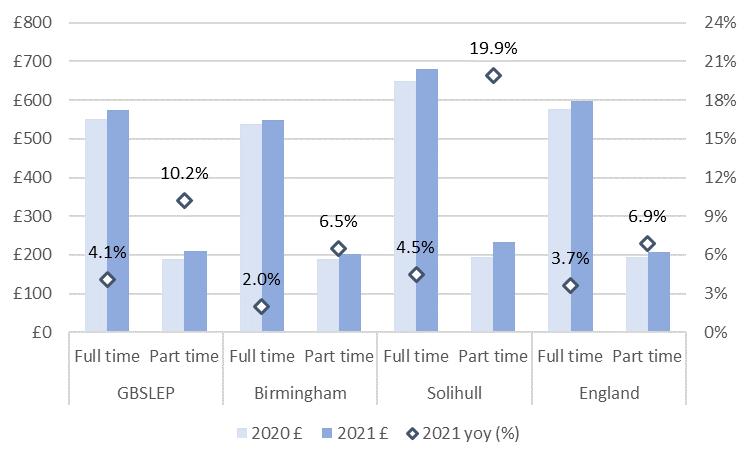

In 2019, Greater Birmingham had a gross disposable household income (GDHI) of £17,988 per head, lower than the average for England of £21,978. GDHI is defined as the amount of money that individuals in the household sector have available for spending or saving after both direct and indirect taxes and direct benefits, reflecting the ‘material welfare’ of the sector.

The GDHI of the city region has declined over the past decade relative to the UK average, whilst London’s has continued to increase. The South East region has remained relatively flat, although significantly above the UK average. Even after redistribution, incomes are falling relative to the more prosperous South East and London, highlighting the levelling up challenge.

GDHI indexed to the UK average (UK = 100)

Source:ONS,Regionalgrossdisposablehouseholdincome(GDHI):enterpriseregions.

Life Expectancy

Healthy life expectancy across the West Midlands metropolitan area is 60.8 years for males and 61.3 years for females, shorter than the national average by 2.3 years and 2.6 years respectively. Life expectancy varies across the region, with males in Birmingham living 8.2 fewer years in good health than those in Solihull, whilst females live 5.5 fewer years in good health. The Levelling Up White Paper seeks to shrink the gap between places with the highest and lowest health life expectancy by 2030.

Healthy life expectancy at birth

Males Females

Birmingham 59.2 years 60.2 years Solihull 67.4 years 65.7 years

West Midlands metropolitan area 60.8 years 61.3 years

England average 63.1 years 63.9 years

Source:ONS,Healthylifeexpectancy,allages,UK. Periodofmeasurement20182020.

15

Dr Justin Varney, Director of Public Health, Birmingham City Council

Birmingham has come through the pandemic better than many would have predicted. Our poverty, ill health and global diversity meant we were starting on the back foot. But as a city we have stood together and responded, across public, private, community, faith, and academic sectors, innovating and evolving our approach as our understanding of Covid grew and our connection with our neighbourhoods and communities strengthened. The first wave predictions for the pandemic ranged from 2,500 to 9,000 deaths due to Covid 19, so far, we have sadly lost just over 3,600, each one important, something I see as a sorrow laden success.

Looking back over the last 12 months, this partnership as a city, that is bold and brave, continues to be part of the way Birmingham does business. We have been challenged by new infections, in the form of Monkeypox and Avian flu outbreaks, navigated the global impacts rolling out from the Ukraine conflict through our food and fuel interdependencies and welcomed as a city hundreds of fleeing refugees. We have hosted the Commonwealth Games with a brilliantly diverse cultural festival and a truly grass roots approach to investment in sport and physical activity. We have been recognised nationally and internationally for our intentional approach to inclusion and deeper exploration of inequalities affecting different communities and our engagement approaches.

As we look towards the future with the ambition of a golden decade for Birmingham, rightfully taking the stage as England’s second city and the economic, cultural and innovation hub of England, we should be positive and hopeful. However, we also need to be honest and authentic about the challenges behind us and those ahead.

Life expectancy in Birmingham remains well below the England average, our citizens live fewer years of life in good health than in neighbouring Solihull, and too many of us live with long term chronic disease. The formation of the NHS Integrated Care System sets a clear vision to change the ways of working, to finally deliver the long standing commitments to joined up health and social care and seamless patient and citizen experiences, and there is clear energy and passion to do this. But it will take significant work to address the workforce challenges and make the commitments real and sustainable.

Improving health outcomes isn’t just about the NHS, only about 20% of health is down to healthcare, 40% is a result of lifestyle behaviours like smoking, inactivity and diet, and 40% is a result of employment and financial security, housing, environmental factors and social connection11. Addressing the health inequalities of our city isn’t just about writing a prescription and popping a pill, it requires consistent action across the whole system.

The health of the city is directly linked to the wealth of its citizens. Being in a good job is good for your health and being unemployed is bad for your health. But health can also be a barrier to employment, especially for those living with long term health issues, a disability or addiction. As employers we want to have the best people working with us and we want them to be productive and effective in work, this means being good inclusive employers because the current reality is that most of us will face health challenges in our lifetimes unless things radically change.

Although the average salary for jobs in Birmingham is higher than the regional and national average the average income for citizens who live here is lower, Birmingham’s high paid jobs aren’t yet putting money into the pockets of local people. So, we need to be more intentional about our commitment to social value as organisations and anchoring the city and its communities with our investment.

Many of our citizens will not just be paid a low wage they will also lack the economic resilience of a savings and a private or workplace pension and that makes them extremely vulnerable to economic shock. Recent modelling of poverty in Birmingham suggests that over 40% of

16

11 https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/time think differently/trends broader determinants health

children in the city and an estimated 300,000 citizens live in poverty and hardship12. For many of these families the reality of their lives will be difficult decisions to heat homes or eat well this winter, so as we look towards a bold and bright future for Birmingham, keep in mind these families and what you can bring to the table to ensure that our economic and social growth closes the inequalities in our city consciously and intentionally, rather than creating a bountiful table that few can afford to eat at.

17

12 JRF, Child poverty rates by local authority

Dr. Paul Vallance, Research Fellow, City REDI, University of Birmingham

Over the past ten years, there has been a growing recognition in both international organisations (e.g. the OECD, European Union) and national governments (including the UK) that a policy focus on economic growth (as measured by GDP) alone will not necessarily translate into widespread and sustainable improvements in people’s quality of life. An alternative way of thinking about economic development policies and metrics has come into focus around the concept of ‘wellbeing’.13 This refers to the physical and mental health of individuals, but also to a wider range of economic, social, and environmental factors that are recognised to influence this at the level of a place based community or population. Economic related dimensions here include those that relate to work and employment, income and personal finance, and education, skills, and training.14

This focus on wellbeing is arguably more relevant than ever in the wake of the COVID 19 pandemic. A Policy Commission being led by the University of Birmingham, as part of the European University for Wellbeing (EUniWell) network, is currently looking at the impact of the pandemic specifically on the wellbeing of young people (15 24 year olds). This is a demographic that may have been less at risk of serious illness from infection with COVID 19, but whose mental health was more likely to be negatively impacted than the UK population as a whole by the social restrictions introduced to limit the spread of the virus in 2020.15

The shock brought by the COVID 19 pandemic on the labour market also disproportionately affected young workers. At the outset of the crisis, full time employees under 25 years olds were 2.5 times more likely than those from older age groups to be employed in sectors (such as hospitality, non food retail, and air travel) that were effectively shut during lockdown periods.16

The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme introduced by the government went a long way to mitigating the projected impact of the pandemic on unemployment, but this furlough programme was less effective in providing ongoing job security to many younger (and older) workers in more precarious forms of employment.17 Other studies have shown that the fall in employment rate during the first year of the pandemic was not equal across the workforce, but affected young Black and Asian people around three to four times more than young White people.18

Nowhere are these issues more pressing than in Birmingham. The city has a combination of a very large (and diverse) population of young people (almost 40% of the population is under 25) and a level of youth unemployment that is higher than other major cities in the UK. This unemployment rate for 18 24 year olds rose significantly during the first year of the pandemic: from 6.3% in February 2020 to 11.6% in March 2021 (which rises to around 20% if people in this age range who are in full time education and not seeking work are discounted).19

The extent to which this situation will harm the wellbeing of these young people is a major concern. Evidence from previous economic downturns has shown that young people experiencing the ‘scarring’ effects of a period of unemployment or financial insecurity early in their working lives are more vulnerable to suffering from poorer employment prospects and health outcomes throughout their future lives.20 Young people leaving education with

European Council, 2019, Draft Council Conclusions on the Economy of Wellbeing

OECD, 2020, How's Life? 2020: Measuring Well being.

Pierce, Hope, Ford. et al. 2020, Mental health before and during the COVID 19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population.

Joyce and Xu, 2020, Sector shutdowns during the coronavirus crisis: which workers are most exposed?

Smith, Taylor and Kolbas, 2020, Exploring the Relationship Economic Security, Furlough, and Mental Distress.

Wilson and Papoutsaki, 2021, An Unequal Crisis: The Impact of the Pandemic on the Youth Labour Market.

Shori, Crofton, McIntosh, Coleman, Horsfall and Samuel, 2021, Breaking Down Barriers: Working Towards Birmingham’s Future

Banks, Karjalainen and Propper, 2020, Recessions and health: the long term health consequences of responses to the coronavirus

18

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

qualification below the university level will have found it especially difficult to find secure employment in the pandemic affected labour market.21

There is, therefore, a greater need than ever to support young people in Birmingham with this transition from education into employment. Given the unprecedented circumstances of the COVID 19 pandemic, this support should also as much as possible be applied retrospectively to the cohort of school leavers whose lives and career plans have been most disrupted over the past two and a half years. This is also linked to the effect that the pandemic will have had on the psychological wellbeing of young people. Making ongoing mental health support widely available through education providers, employers, and the health service will be an essential part of an inclusive post pandemic recovery. Even as the threat from COVID 19 fades into the background, the impending financial impact of the growing cost of living crisis on vulnerable young people means that a focus on wellbeing will remain a key feature of any effective levelling up programme.

19

21 Henehan, 2020, Class of 2020: Education Leavers in the Current Crisis

Redundancies

Despite the challenges facing the general economy, redundancy rates have remained low so far this year. Although redundancies in the West Midlands (ITL1) did rise during the pandemic, hitting a peak rate of 15.5 per thousand employees between July and September 2020, they subsequently fell back again in 2021. For the three months between May and July 2022, there were 2.0 redundancies per thousand across the region, in line with the national average. It is likely the rate will increase if the UK enters recession and interest rates continue to increase.

Redundancy rate per thousand employees

Source:ONS,RED02 Redundancybyage,industryandregion.

Claimants

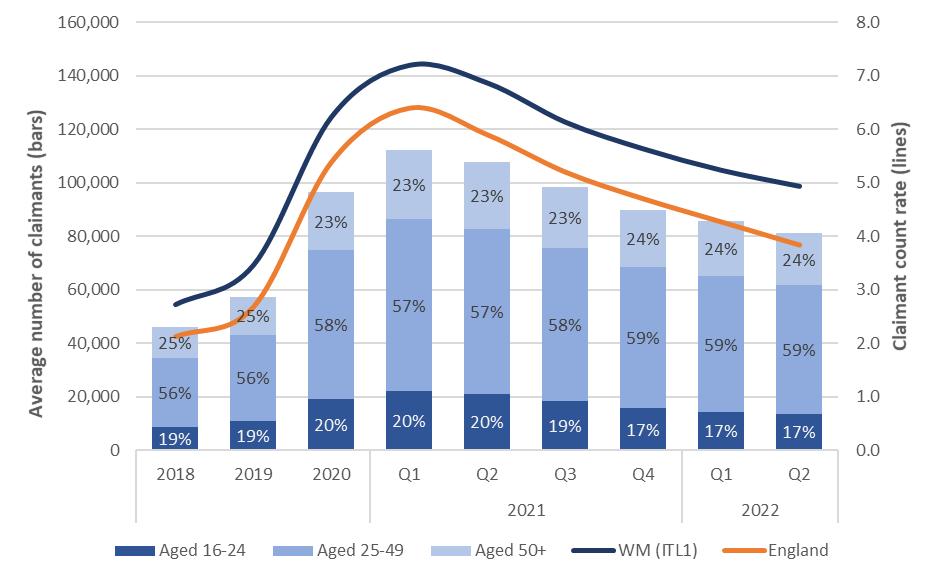

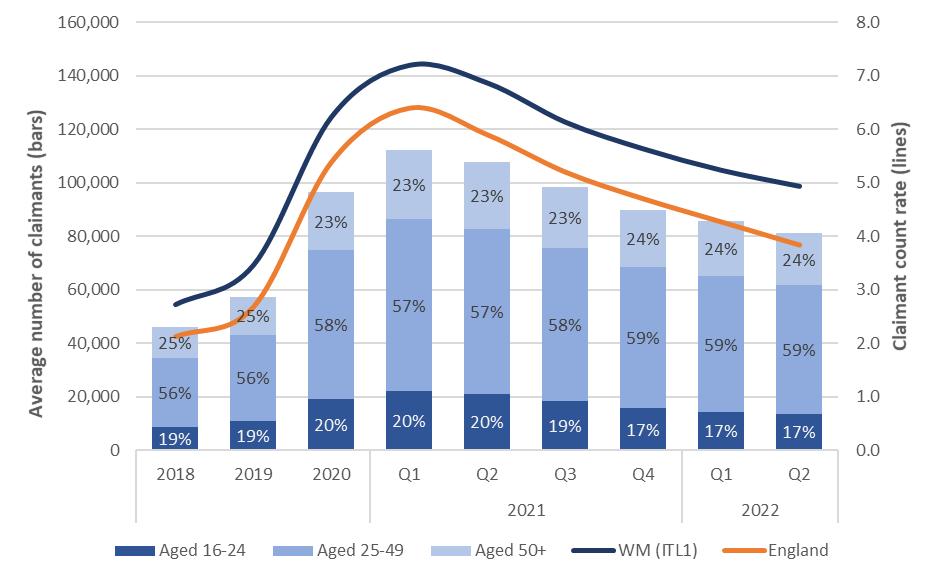

The number of claimants of unemployment support in Greater Birmingham rose dramatically during 2020 and Q1 2021, although had already been increasing prior to the pandemic. The number of claimants peaked at 113,850 in February 2021 before falling back to 80,270 by June 2022 although this figure remains significantly higher than pre pandemic level. The claimant count rate for the wider West Midlands (ITL1) was 4.9% in June 2022, significantly higher than the English average of 3.8%.

The pandemic disproportionately affected younger age groups, with 16 24 year olds comprising a fifth of overall claimants in 2020. During this time, the Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce worked with Birmingham City Council on a research project seeking to understand the impact of Covid 19 on young people and what needs to be done to prevent a ‘crisis cohort’ with diminished employment prospects and earning potential. This research contributed to the Birmingham City Council report, Breaking Down Barriers: Working Towards Birmingham’s FutureSupportingYoungerPeopleIntoEmployment

The proportion of overall claimants aged 16 24 years old fell to 17% as of June 2022, although the number of young claimants remained 13% higher than in February 2020.

20

Benefits claimants by age group (GBSLEP) and rate (West Midlands ITL1 & England)

Unemployment

Employment markets have proved remarkably resilient this year and national unemployment rates have fallen to historic lows. Job losses and unemployment was lower than widely anticipated over the course of the pandemic on account of the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) which closed on 30th September 2021 with around 5% of employments still on furlough at that date. Labour statistics indicate many of those workers were taken back into work by their original employers, and those that weren’t managed to find alternative employment.

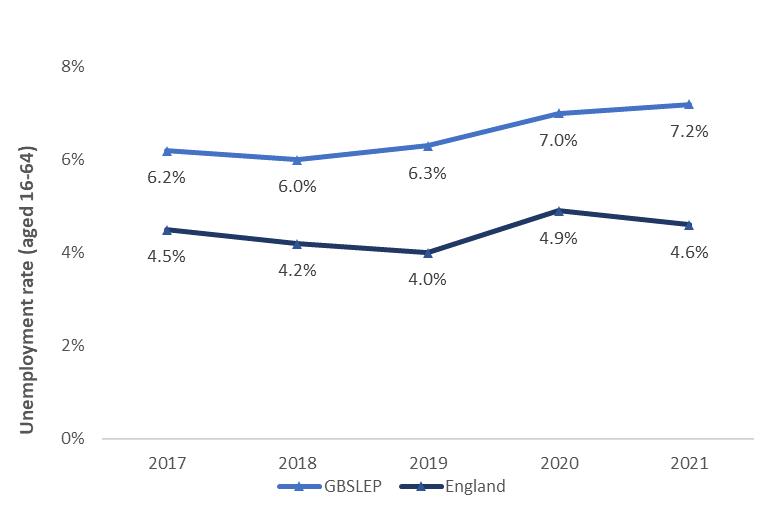

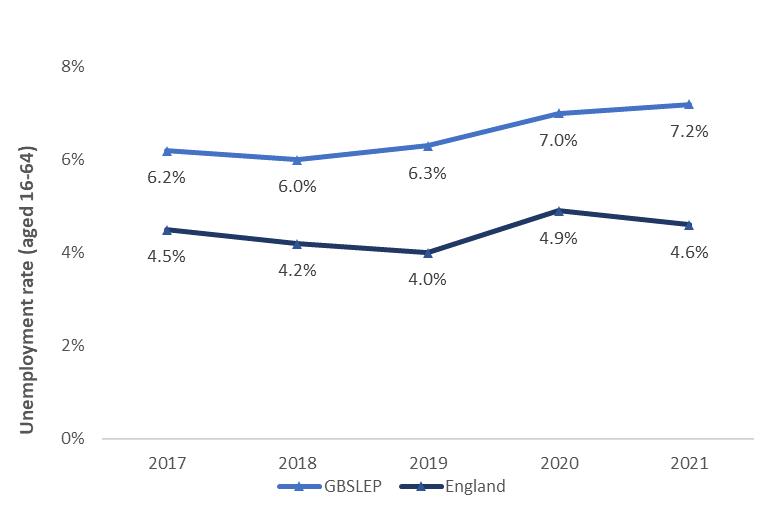

Quarterly ONS data shows that regional unemployment rates have trended downwards from their pandemic highs in late 2020. The unemployment rate for the three months to July 2022 was 4.7% for the West Midlands (ITL1) down from 6.5% in Q4 2020, although slightly up on Q1 2022 when the rate was 4.6%. The rate of unemployment across England was 3.8% for May to July, down from a Q4 2020 high of 5.5%.

Quarterly unemployment rate (aged 16 64)

Quarterly data is not available at the city region level. Annual data for Greater Birmingham shows that unemployment continued to rise from 6.3% in 2019 to 7.0% in 2020 and then to 7.2%

21

Source:Nomis,Claimantcount. IncludesthoseonJobSeekersAllowanceandUniversalCreditclaimantsrequiredtoseekwork.

Source:ONS,Regionallabourmarket:Headlinelabourforcesurveyindicatorsforallregions.

in 2021, a greater rise than nationally. Unemployment remained significantly above the England average at the end of 2021.

Annual unemployment rate (aged 16 64)

Source:Nomis,Annualpopulationsurvey.

Unemployment for males remains higher than for females at 7.6% and 6.8% respectively in 2021. The unemployment rate for ethnic minorities aged 16 and over remains very high at 13.9%, a 2.8% increase since 2019.

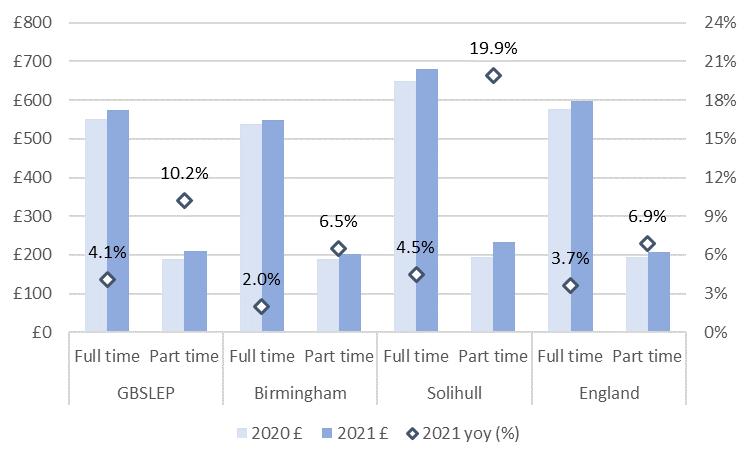

Persistent tightness of the labour market continues, with many sectors struggling to recruit suitable workers: indeed, 76% of firms reported experienced recruitment difficulties in the Q2 2022 Quarterly Business Report, the joint highest figure since Q3 2007 and the same as Q4 2021. A lack of suitable workers is one of the most pressing issues facing business leaders in the UK22 and is feeding into wage inflation as firms utilise bonuses to attract and retain skilled workers. However, the Bank of England has recently indicated that labour demand may be starting to weaken and recruitment difficulties moderating.23

22

22 Russell Reynolds Associates, 2022 Global Leadership Monitor [accessed September 2022] 23 Bank of England, Monetary Policy Summary, September 2022

Professor Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development, City REDI, University of Birmingham

The Covid 19 pandemic has caused severe disruption to the labour market since the first national lockdown in March 2020. Restrictions eased and tightened over subsequent months, with some local variations, with further national lockdowns in November 2020 and January 2021. Lockdowns entailed the closure of certain sectors, homeworking in several others and continued workplace attendance elsewhere. Digitalisation gathered pace, transforming working practices for many workers and contributing to changing business models. Concern for mental health and well being has become more prominent. Over the same period businesses have had to deal with the implications of EU exit, along with broader trends including the greening of the economy in the transition to Net Zero.

A key early development in the Covid 19 pandemic to counter job losses was the introduction of the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS), which applied from 1 March 2020 and ended on 30 September 2021. At the outset, the scheme provided grants to employers so they could retain and continue to pay staff during coronavirus related lockdowns, by furloughing employees at up to 80% of their wages. Furlough levels fluctuated with changing lockdown rules and revisions to the CJRS. Utilisation of furlough varied by sector, with occupations, age groups and locations differentially impacted.

As the economy has opened up former concerns around unemployment were superseded by a focus on labour and skills shortages. In some of the sectors hardest hit by the Covid 19 pandemic substantial numbers of workers have left, fuelling a rather different kind of jobs crisis. This is seen particularly graphically in summer 2022 at Birmingham Airport which, along with airports elsewhere in the UK and beyond, is struggling to find staff to meet the demand for an increase in air travel. For many workers, the Covid 19 pandemic has triggered a reassessment of working lives as everyday routines were interrupted, with some unwilling to return to the types of jobs undertaken formerly.

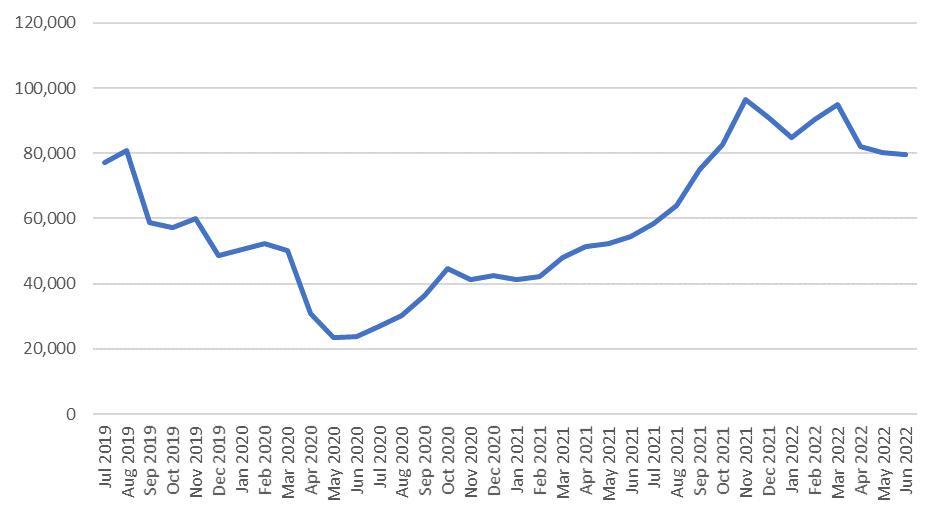

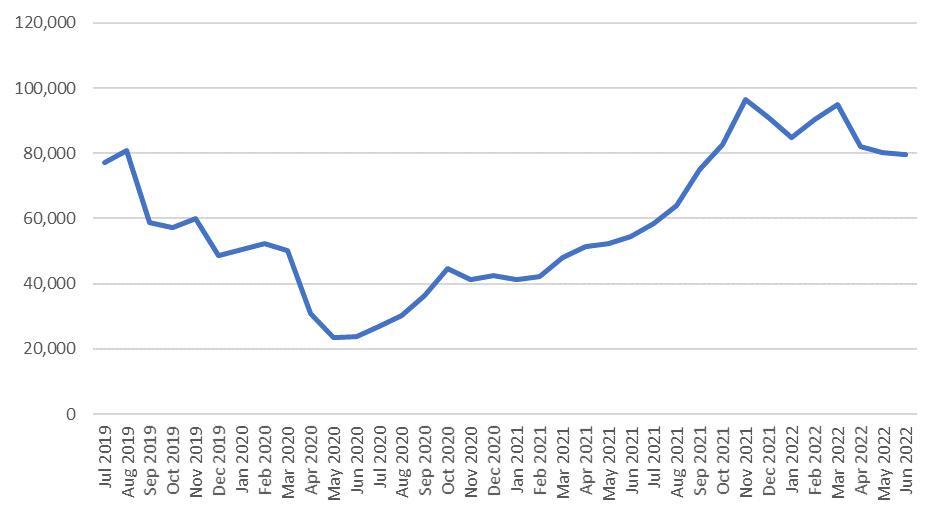

The scale of change in demand for labour is shown in Figure 1 which shows unique job postings in the GBSLEP area on a monthly basis over the three year period to June 2022. After falling to fewer than 24,000 unique job postings per month in May and June 2020, there was a rapid rise in trend in summer and autumn 2021 to a peak of over 96,000 in November 2021, since when the trend has stabilised at a relatively high monthly level and begun to reverse slowly. With high inflation and the cost of living crisis impacting on demands for higher wages and consumer confidence, and ongoing geopolitical and economic uncertainty, the future direction of vacancy trends is unclear.

23

Source : Lightcast. Note : Vacancies not advertised online are excluded.

So, why has labour supply been unable to meet demand over the last year? There are at least three reasons. First, the combined effects of the Covid 19 pandemic and post Brexit immigration policy have meant a reduction in international migration which some organisations had relied on, at least in part, to meet labour and skills needs. Secondly, economic inactivity has increased in some age groups, including the over 50s. Thirdly, there are skills mismatches.

Together, these factors point to a need for a focus on active labour market policies to encourage more of the economically inactive especially, but not solely, older people and those with health conditions, as well as marginalised young people into work. The onus is also on employers to reconsider their recruitment channels and selection criteria, and, where possible, to offer more flexible and hybrid working opportunities. Adaptability in the face of the Covid 19 pandemic has shown what is possible, with such working practices becoming more common across many sectors and occupations.

There is also a requirement to strengthen the supply of skills, among both new entrants to the labour market and the existing workforce, through careers advice and guidance, apprenticeships and (re)training. As noted by the Skills and Productivity Board, technological change and the emerging needs of the green economy require major responses from the skills system.

However, levelling up is not just about the supply of skills; it is also about the upgrading of job quality to make jobs more attractive and fulfilling, the demand for skills and the utilisation of skills. One potential avenue for better skills use is promoting high performance working practices such as employee reward programmes, more flexible working hours, mentoring and leadership development courses, and an organisational culture that promotes training and development. Robust local economic development policy, business support and innovation support will be key to success, alongside skills policy.

24 Figure 1: Unique job postings in GBSLEP area, July 2019 to June 2022

Economic Inactivity

A rise in economic inactivity over the course of the pandemic has been a primary contributor to tight labour markets. Economic inactivity was declining across the city region pre pandemic and hit a low of 23.3% in 2020 against the English average of 20.6%. It rose by 2.1 percentage points in 2021 and at a faster rate than nationally (0.7 percentage points).

Rising inactivity was particularly significant amongst 16 24 year olds, increasing from 40.7% in 2020 to 47.7% in 2021, coinciding with a significant increase inactive persons in education. A continued rise in inactivity amongst older working aged people (aged 50 64) from 24.5% in 2019 to 27.9% in 2021 has been partly driven by early retirement as household savings increased during the pandemic and partly by an increase in self reported ill health.24 25

Economic inactivity rate by age group (GBSLEP)

Source:Nomis,Annualpopulationsurvey.

Positively, economic inactivity amongst ethnic minorities has decreased in recent years: down from 37.6% in 2017 to 30.6% in 2021, significantly narrowing the gap between minorities and non monitories in the workforce. The share of females in the workforce has increased as women have entered or remained at work due to increased flexibility or to make up for a partner’s lost income. However, the percentage of inactive females remains higher than males with almost one in three females inactive in 2021 compared to one in five males.

25

24 Francis Devine, 2022, Will more economic inactivity be a legacy of the pandemic? 25 The Health Foundation, 2022, Is poor health driving a rise in economic inactivity?

Economic inactivity rate by group (GBSLEP)

Source:Nomis,Annualpopulationsurvey.

The primary reason for inactivity is education, accounting for 36.1% of inactive people in 2021 and notably higher than the proportion pre pandemic (33.4%). It is believed younger people have chosen to enter or remain in education in response to uncertain economic circumstances.

The proportion of inactive people due to retirement increased by 0.8 percentage points, whilst the proportion inactive due to long term sickness increased by 1.2 percentage points between 2019 and 2021. It is believed older workers leaving the workforce due to these reasons is one of the key contributing factors to skilled labour shortages.

The only notable decline has been in the proportion of people being out of the workforce due to looking after family or the home. As noted above, it is believed more women have entered or remained in the workforce over the past two years.

Economic inactivity by reason (GBSLEP)

Source:Nomis,Annualpopulationsurvey. *Otherisabalancingfigureto100percent.

The proportion of inactive people who want a job has declined over the past two years, particularly amongst males. In 2019 one in five economically inactive males wanted a job, that figure fell to almost one in eight in 2021. The proportion of inactive females that want a job, which has historically been lower than for males, also fell but less dramatically from 13.5% to 11.1%.

26

Percentage of inactive persons who want a job (GBSLEP)

Hiring Activity

Hiring activity returned to strength quickly in early 2021 and has remained elevated for the past 18 months. Adzuna data shows that the number of online job adverts in the West Midlands (ITL1) peaked in November 2021 at 53% above February 2020 levels. Data indicates the regional job market has been stronger than nationally, although the gap has shrunk in recent months as hiring activity has softened. Regional online job adverts were still 8% above the pre pandemic benchmark as of early September but were on a downward trend.

Online job adverts regional index (February 2020 = 100)

Analysis by category at the UK level indicates that demand for workers in Transport, Logistics and Warehousing, and Manufacturing remains strong although is softening. Online hiring activity in Construction/Trades has steadily declined back to levels seen in February 2020. Hiring for Wholesale and Retail remains strong.

27

Source:Nomis,Annualpopulationsurvey.

Source:ONS,Onlinejobadvertestimatesbyregion,deduplicted(originatesfromAdzuna).

28 Online job adverts UK category index (February 2020 = 100) Source:ONS,Onlinejobadvertestimatesbycategory,deduplicted(originatesfromAdzuna).

Paul Daniels, Employer Brand and Marketing Specialist Global, Deutsche Bank

Deutsche Bank has significant operations based within Birmingham’s Brindley Place, spanning many of the core functions of the bank. As a key delivery hub within our global network, the site delivers critical activities, including Know Your Client (KYC), Anti Financial Crime (AFC), Compliance, Human Resources, Technology and Regulatory Operations and employs a diverse range of skilled professionals.

The bank is highly focused on bringing in the best talent from across the West Midlands and surrounding areas and over the past decade has built a diverse workforce with a mix of backgrounds and experience. Roles are available from entry level through to team leaders and senior leaders.

High demand for skills within financial and professional services in 2022 (up by 58% from June 2020) has created critical shortages across the UK. Birmingham’s position as a major economic and cultural hub with rich talent pools across industry sectors means that the city has become a vital source of talent for the bank. Whilst many of our roles demand specific experience within a related sector, there are also many opportunities for those with transferable skills. Crucially, the talent market in the area is able to provide the blend of established expertise and future potential that we’re looking for.

We are equally focused on ensuring that our existing talent build long and successful careers with us.

Leveraging internal talent via internal mobility and providing access to new opportunities ensures their continued development and retains institutional knowledge and expertise within the business.

In a post Covid environment, we are entering a new era of the workplace and the bank is evolving continually to ensure that we invest in employee wellbeing and can meet the expectations of today’s workforce. We have introduced a successful hybrid working model which offers flexibility to our people whilst meeting the needs of clients and the bank.

This is supported by a competitive and flexible benefits and compensation package including 30 days’ holiday for all employees. Striking the right balance between work and home lives and providing an engaged, supportive environment in which colleagues can thrive is critical to the success of our business.

Equally important for us is creating an environment where all employees feel welcome and are empowered and equipped to achieve success. We continually evolve our processes in order to build teams with a broad range of skills, experiences and backgrounds generating new approaches and sparking innovation.

29

Skills Attainment

Skills attainment continues to improve, with the number of people at NVQ4+ increasing from 31.8% in 2017 to 39.7% in 2022. The number of people with no qualifications increased to 8.7%, but remains significantly lower than 2017 (10.3%). Despite the continued and positive improvement, the region still lags behind the national average of 43.1% of adults aged 16 64 having skills at NVQ4 or higher.

Skills attainment across Greater Birmingham (GBSLEP)

The Government announced new plans in its Levelling Up White Paper to devolve control over funding and policy relating to skills and education. In the West Midlands, this includes control over the allocation of the Shared Prosperity Fund intended to replace EU Structural Funds to improve education and training facilities across the region. The region’s digital and retrofit skills bootcamps will be extended, with additional bootcamps added in green skills, manufacturing, healthcare and professional services.26 Coventry and Warwickshire Chamber of Commerce, Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce and the Black Country Chamber of Commerce have also been selected by the Department for Education to lead on a Local Skills Improvement Plan (LSIP) for the West Midlands and Warwickshire. This work will seek to build a stronger, more dynamic partnership between employers and further education providers to ensure that skills provision can be as responsive as possible to local labour market needs.

30

Source:Nomis,Annualpopulationsurvey.

26 WMCA press release, Feb 2022, available here

AbigailTaylor,ResearchFellow,City REDI, University of Birmingham and Professor Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development, CityREDI,UniversityofBirmingham.

Skills are a key driver of economic disparities between people and places. In the Levelling Up White Paper one of the 12 Levelling Up Missions focuses on Skills: ‘By 2030, the number of people successfully completing high quality skills training will have significantly increased in every area of the UK. In England, this will lead to 200,000 more people successfully completing high quality skills training annually, driven by 80,000 more people completing courses in the lowest skilled areas.’

This ambition chimes with the policy direction set out in 2021 in Skills for Jobs: Lifelong Learning for Opportunities and Growth. This White Paper emphasised the need to raise educational standards, increase the level of high quality skills training available to learners and put employers at the heart of the further education and training system in order to align education and skills provision with the needs of the economy.

As noted by the Institute for Government, levelling up and skills policy needs to have a three fold focus. First, there is the need to improve skills for those entering the labour force. Secondly, given the length of working lives and changes in skills requirements, improving lifetime learning and retraining provision is essential. Thirdly, there needs to be an emphasis on skills utilisation, through improving the match between skills and jobs. The latter emphasises the importance of labour demand and the importance of breaking out of low skills traps. This requires looking beyond skills policy to broader economic development policy concerns with making Birmingham attractive to businesses and skilled workers.

Research conducted by WMREDI, indicates that within Birmingham and the wider West Midlands universities and colleges already contribute considerably to up skilling and reskilling through developing future sectoral skills, piloting new ways of learning, supporting graduate employability, addressing access to higher education (HE) barriers, developing pathways between further education (FE) and HE, introducing applied higher level skills development initiatives and working with regional governance stakeholders. Nonetheless, the research suggests that to effectively address the skills challenges that the West Midlands is facing and support levelling up, there is need to prioritise expanding partnerships and integration between HE institutes and FE institutes and other regional stakeholders. To maximise the effectiveness of partnerships, the broader role of universities in relation to skills and economic development should be recognised across regional stakeholders. Partnerships need to build on the strengths of FE and HE.

In terms of equipping residents and workers with the skills that businesses need, now and in the future, one important focus of policy attention is digital skills. There is a predicted national digital skills shortfall. This is concerning for Birmingham (and the West Midlands) given the recent rapid growth experienced by the tech sector, and the potential for future growth. Given the importance of digital skills in many roles and businesses, there is a need to ensure that all people acquire basic digital skills (i.e. are sufficiently digitally literate to participate in society and the economy). But digital skills for levelling up also requires digital skills for the general workforce, which vary by sector and occupation. To drive productivity and growth digital skills for ICT professionals that are essential to the development of new digital technologies and to new products and services are required too. Birmingham is active in promoting digital skills at all of these levels and has also led in investment in no code provision to provide people with skills which can help launch new services and products and underpin the creation of new enterprises.

Indeed, growing skills in the digital sector is one of the priorities in the West Midlands Combined Authority Regional Skills Plan. The West Midlands Plan for Growth also stresses the importance

31

of developing future skills pathways across the West Midlands primary clusters (which include healthtech and med tech, aerospace and modern and low carbon utilities) to support levelling up.

More broadly, the Skills and Productivity Board has emphasised that to fully realise the benefits of individual, firm or government investments in skills, there is a need for complementary investments in other types of capital (namely physical, intangible, financial, social and institutional) as set out in the Levelling Up White Paper. Longer term, for levelling up of skills to be fully effective there is need for broader investment across health, education, social services and public transport. Obtaining such investment will require strategic coordinated lobbying of national government by the West Midlands Combined Authority, the Chamber of Commerce and Birmingham City Council.

32

Professor Chris Millward, Professor of Practice in Education Policy, University of Birmingham

Last year’s Birmingham Economic Monitor pictured a city region managing a global pandemic and its profound effect on the normal conduct of work of all kinds. A year later, we are still managing the consequences of lockdowns, which continue in some of our major trading partners and have been compounded by the additional costs arising from Brexit and the war in Ukraine. It seems likely that rising costs and prices, coupled with labour shortages and their combined impact on industrial relations, will be the dominant concern for businesses and public services well into 2023.

This backdrop makes it challenging to set our sights on the skills and knowledge that the Birmingham city region will need to thrive beyond the next year, let alone the type of education and training system that could deliver this. Attempts to anticipate future skills needs are riven with uncertainties associated with factors such as the character of technological change in education and the workplace, levels of migration and the attitudes to work among an ageing population, the pace of progress towards the green and digital economies, and local, national and international politics.

A crucial lesson from the pandemic is the importance of adaptable vocational and professional skills together with strong relationships between local educational institutions, government agencies, businesses and public services for resilience in a rapidly evolving world. In order to help drive productivity and growth, universities and colleges need to engage in a continual dialogue with employers to help shape ways of working, not just respond to the identification of current skills gaps.

Birmingham is well positioned for this due to a distinctive pattern of skills infrastructure, which straddles education and the workplace in areas such as cyber, manufacturing, healthcare, digital, transport and sustainability. Through the Mayor, we are at the forefront of trailblazer negotiations for the next phase of devolution, with funding for skills training beyond adult education at the top of the list. Alongside this, the Skills and Post 16 Education Act will empower the city region’s employer representative bodies to establish a Local Skills Improvement Partnership, with which universities and colleges will have a legal duty to engage. This could become a platform for the dialogue that is needed to shape and address future skills.

At a time when advanced economies are concerned about ageing populations and labour shortages, Birmingham has one of the youngest and most diverse populations in Europe. We will only, though, be able to yield the benefits of this if we can bring the educational attainment of our young people up to the levels of our competitors. This itself requires us to understand the different pathways through education and work among communities living close together within the city region.

Birmingham is now close to the national average for the proportion of the population with level 4 qualifications or above, rising from 37% to 40% during the last year, but the proportion with no qualifications increased from 9.5% to 11%. Hall Green and Erdington have among the highest and lowest rates of progression to higher education in the country, whilst the city’s Pakistani and Bangladeshi students are among the most likely to study and work near to home.

Further devolution heralds the prospect for a more localised approach to improving education and skills, which will take more account of specific experiences and patterns such as these, and also align more closely with the city region’s economic strategy. This will be crucial to building the equilibrium between high levels of skills and knowledge, and productive and well paid jobs, which characterises the most prosperous cities around the world.

33

Dr. James Davies, Research Fellow, City REDI, University of Birmingham.

Creative Industries in the UK have been growing for the past two decades. In the pre period 2010 2016, the GVA of the creative industries grew by almost double the UK average. Within those industries, it is the IT software and computer services sector which is the biggest contributor (£34.7bn), with film and television (£15.3bn) next in line. The two major creative clusters in the West Midlands are that of television production in Digbeth, and the ‘Silicon Spa’ video game production cluster, around the market town of Leamington Spa in Warwickshire.

Pre pandemic, the creative industries were growing rapidly, showcasing a huge amount of potential. The region acknowledged this potential in the WMCA’s Creative Industry Sector Plan; the West Midlands’ creative industries in total contributed more than £4bn in regional GVA, and nearly 50,000 full time creative jobs. The pandemic had a profound impact on the creative sector, yet while television and film production came to almost complete standstill in 2020, video game consumption and demand caused some sub sectors of the creative economy to grow. As the country, and the Midlands region, look to recover from the impact of the pandemic, creative industries are well positioned to offer considerable growth.

Games form an important and growing component of the creative production sector: 10% of the UK games industry (£224 million) is situated in the Leamington Spa creative cluster, but also offers strong opportunities for collaboration with other adjacent industries, including digital manufacturing, VR and AR applications as well as next generation virtual production; a skillset that crosses the boundary between television production and video games. Similarly, the UK's television industry has entered a ‘golden age’ of high end drama production. The huge success of Peaky Blinders, presence of BBC Three and the BBC Academy in Digbeth as well as the BBC's decision to move the Asian Network and Newsbeat teams to the Midlands as part of the BBC's across the UK plan offers a similar opportunity for growth.

However, there are a variety of challenges that need to be addressed if the growth of the West Midlands creative industries is to be fully realised. As mentioned, despite sub sectoral differences, the impact of the pandemic cannot be ignored. Multiple lockdowns across 2020 and 2021 had a dual impact, stifling production while simultaneously massively increasing demand for content. The pandemic, a surge in games’ popularity and a lack of mutual recognitions of qualifications internationally post Brexit have exacerbated a labour shortage in the gaming industry, an industry which used to rely heavily on global, and particularly, EU talent. In a UKIE survey in 2020, 76% of participating UK video game companies reported difficulties in finding skilled staff, well above the EU average (40%). In demand skills include animation, design and writing skills, as well as programming, technical, art, leadership and management skills. A similar story is playing out in television, with editors, animators, production co ordinators and accounting staff in short supply, as Streaming Video on Demand services (SVoD) have ushered in an unprecedented demand for content.

There is an opportunity for talent from the region to fill these gaps. The region is well placed in terms of training provision. The East & West Midlands both rank in the top five UK regions for game related further education courses. Additionally, Birmingham City University and Coventry University have well regarded software and video game development courses. However, a high degree of variability in the reputation of courses suggests more attention is required to ensure skills shortages within the Midlands’ creative sectors are sufficiently addressed. It’s recommended that higher and further education institutions learn from those that are producing a higher proportion of students able to make the leap to professional developer. Concurrently, television and video games creative industries should feedback, offering time and manpower to academics, enabling them to understand how the industry currently works, and where skills fit into the pipeline of creative development. Finally, educators need an understanding not only of where skills shortages currently are, but also the ability to predict where they may emerge in future.

34

The scars of COVID 19 will continue to be felt across the screen sector, though in many ways the pandemic’s impact was in tugging at threads that were already loose, highlighting issues with job precarity, a lack of career development pathways and inadequate and mismatched training and skills provision. Though not the only challenge that the creative industries face in 2022, the issue of skills shortages should not be under estimated. As the perceived skills needs across the screen sector continue to coalesce under the umbrella term of ‘Createch’, increased communication and collaboration between industry and the educational ecosystem will ensure a higher proportion of graduates and those entering employment are sufficiently equipped to survive and thrive in both the Television production and video games sectors in the region.

35

Rebecca Waterfield, Director of Business Development, South and City College Birmingham

Further education colleges have a vital role to play in meeting skills gaps to ensure that our regions businesses have access to a workforce with the right skills to meet current and future demands as well the ability to upskill staff to enable them to progress. Further education colleges are unique in being able to be highly responsive to industry needs along with the ability to combine academic rigour with vocational expertise.

There is a common misunderstanding of the range of support and courses available in colleges and how employers can utilise their local college to create provision to meet skills gaps. In addition to traditional courses, which, run from September to June colleges also offer a plethora of training options that start throughout the year. A recent example of how colleges can work with employers to make significant impact on skills gaps is the partnership between South and City College Birmingham and National Express.

In 2018, the National Express Engineering Training Academy was created at the College’s Bordesley Green Campus. The focus was to create a workspace that encompassed all of the facilities needed to enable apprentices to have a realistic learning experience whilst in college that closely matched the workplace experience.

“

FromtheverybeginningoftheprojecttocreatetheNationalExpressandSouth&CityCollege EngineeringTrainingAcademy,weallknewthatwehadtheopportunitytocreatesomething veryspecialthatwouldtransformtheopportunitiesandlivesofpeopleinthelocalareawhilst addressing the skills shortage within the bus and coach industry.” Said Lee Sandford, Engineering Training Manager, National Express “Through true partnership working, that included innovative thinking, joinedup processes, and open communication, this initiative is makingafantasticpositiveimpact.”

This partnership has further developed with the 2022 launch of the electric vehicle training academy at our Bournville Campus and Longbridge. This academy has allowed local motor vehicle garages to up skill their employees to be able to work on electric vehicles, at no cost to them. This allows garages to ensure that they are future proofing their workforce and are able to meet the countries ambition for Net Zero.

All colleges have dedicated employer engagement teams who are tasked with working with industry to understand current and predicted skills needs. It is vital that employers work with those teams to influence curriculum design and delivery to ensure that our regions young people develop the right skills to be the workforce of the future and that skills interventions can be created to support existing employees to upskill to progress within the organisation.