9 minute read

Cincinnati, p. 10

BRIDGE TO THE FUTURE

In 1856, inventor John A. Roebling began work on an Ohio River crossing that he envisioned as both a work of art and a monument to engineering. That bridge, which now bears his name, connects the cities of Cincinnati and Covington, Kentucky, to this day.

By Vince Guerrieri

As the 19th century reached its midpoint, the idea of a bridge crossing the Ohio River from Cincinnati to Covington, Kentucky, seemed as fantastic as the idea a century later of rockets going to the moon.

The cost of such a structure would run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars — an almost incomprehensible sum at a time when $10 was the average monthly wage in Hamilton County. Also, the river was a major transportation route. Ferries crossed back and forth between Ohio and Kentucky regularly, and larger boats navigated down the Ohio River, carrying goods westward throughout the growing nation. How could a bridge of that length be built without multiple pylons, impeding those shipping lanes?

A Prussian immigrant had the answer.

John A. Roebling had come to the United States as a young man and distinguished himself as an engineer and inventor. He was at the forefront of a new type of construction. He received a patent for the assembly of metal cables in his factory outside Pittsburgh, and he’d secure those cables on a tower in the middle of the river. The cables would hang in a parabola, and the roadbed of the bridge would be suspended from them, with the cables’ tensile strength keeping the bridge in place. It was an ambitious plan, but if it worked, it would be more than an engineering triumph.

“As one of the great thoroughfares of the country, and spanning one of the great rivers of the West, this bridge, when constructed, will possess great claims as a national monument,” Roebling wrote in an 1846 report detailing his plan. “As a splendid work of art and as a remarkable specimen of modern engineering, it will stand unrivalled upon this continent. Its gigantic features will speak loudly in favor of the energy, enterprise and wealth of the community, which will boast of its possession.”

It would be another decade before Roebling could start work on the project — and then another decade beyond that before its completion, as the project was delayed by a financial crisis and then the Civil War. But ultimately, the bridge proved to be even more useful than Roebling could have imagined, and every bit the monument he claimed it would be.

JOHN ROEBLING WAS born June 12, 1806, in Thuringia, a region of Prussia, an independent kingdom that later became part of Germany. He was educated as an engineer in Berlin and came to the United States when he was 25 years old. He settled in Saxonburg, about 30 miles north of Pittsburgh, at the time still a frontier town formed at the confluence of three rivers. It was a natural site for him to develop his skills.

The fastest and most popular means of travel at the time was on water. The young country’s largest cities sprouted up near waterways, either along the coast of the Atlantic Ocean or the Gulf of Mexico, or on the rivers that crisscrossed the country. And where there were no waterways, canals were dug. Roebling’s first job was on the Sandy & Beaver Canal, an ambitious project that would go from Tuscarawas County in Ohio to Glasgow, Pennsylvania. When the canals were supplanted by railroads, Roebling started surveying routes for train tracks through the mountains of Pennsylvania.

While in Pennsylvania, Roebling watched the steam-powered funicular railways, with stout ropes pulling two counterbalanced cars, one going up as another went down, carrying people or goods. He realized metal wire could be bundled into cables and, in 1841, started a company to do just that. He received a patent for a machine to manufacture “wire ropes” the following year as Roebling’s cable was used in an inclined railway. It wasn’t long after that he found a new use for them.

In 1845, a new aqueduct crossed the Allegheny River in Pittsburgh, and the following year, a new bridge spanned the Monongahela River at Smithfield Street. Roebling also built suspension bridges in the Philadelphia area, as well as a span across the Niagara River that was strong enough to carry trains.

In 1846, the state of Kentucky chartered a company to build a bridge from Covington to Cincinnati. In 1849, the state of Ohio incorporated a similar company. But ferry operators held enough power to ensure that the bridge would not connect with any existing road on either side (an act not just of pettiness, but close to sabotage, since the street grids of Covington and Cincinnati lined up exactly). And as the nation inched toward a reckoning involving slavery, the bridge company’s charter decreed that no slave shall be allowed to pass over the bridge without their master or written permission, and that the bridge company would be responsible for any financial losses that could result from escaped slaves.

CONSTRUCTION STARTED IN 1856. Beams were encased in concrete and sunk into the riverbed. Soon, towers started to emerge from the water. But on Aug. 24, 1857, the New York branch of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Co. failed. Grain prices and consumer prices were already falling, and railroads had overextended. Transactions were suddenly scrutinized, and thanks to the new telegraph, word spread of financial problems, leading to the Panic of 1857. Credit dried up, and construction on the bridge halted.

War loomed, and finally, in 1861, it came. People on both sides of the river wondered if the bridge would be completed at all, or if Kentucky would follow the lead of other Southern states and attempt to secede. Ultimately, Kentucky stayed in the Union, and in 1862, Col. John Morgan led an incursion throughout the Bluegrass State. Covington prepared for defense, but Morgan ultimately fell back

to Tennessee. Later that summer, a Confederate army marched into Kentucky and took Lexington, with sights on not just Covington, but Cincinnati. Soon, reinforcements came to the Queen City, and a pontoon bridge was built into Covington for Union troops to fortify the city. Suddenly, the need for a bridge seemed more apparent than ever.

In 1863, construction resumed. Roebling was pleased to find that the towers remained as sturdy as ever, even five years after work had stopped. Shortly after the war ended in 1865, the first cable was strung between the two towers, and the bridge’s completion was all but assured.

The bridge was the longest span in the world when it opened to foot traffic on Dec. 1, 1866. The next day, it was estimated that at least 75,000 people — almost one-half of Cincinnati’s population in the 1860 census — crossed the bridge. Because the Ohio River froze, making it impassible by ferry, the bridge opened to other traffic ahead of schedule, a month later.

“It is scarcely deemed necessary to say to you that the bridge is a complete success,” Cincinnati and Covington Bridge Co. president Amos Shinkle wrote in his annual report in 1867.

The bridge from Cincinnati to Covington would not be Roebling’s most famous work, but it would be the last completed in his lifetime.

In 1867, the New York General Assembly chartered a company to build a bridge across the East River, linking New York City with Brooklyn (then a separate city — the third largest in the country, in fact; it would not become a borough of New York City until 1898). It would be longer than the Cincinnati-Covington Bridge, and more complicated. The East River is a tidal strait, with rising and falling tides. The currents were more powerful there than in the Ohio River and even changed the direction of the East River’s flow throughout the day. Of course, John Roebling was hired for the job.

ROEBLING STARTED SURVEYING the Brooklyn project in 1869. On June 28, he was taking measurements at the Fulton Ferry Landing, when a

Modern photo of the John A. Roebling Suspension Bridge, which reopened to vehicular traffic in 2022 after undergoing repairs

docking tugboat crushed his foot against the piling. He was taken home and seen by a doctor, but Roebling had no faith in medicine. He was back at work the next day.

“You are inviting certain death for yourself,” a doctor told him. Within three days, Roebling was unable to eat or speak. His wound had become infected, and lockjaw — a disease related to tetanus — had set in.

Even as he got worse, Roebling continued to give orders, writing them instead of speaking. But his handwriting got less legible as the bacterial infection progressed through his body, and his mental acuity started to fade. On July 22, 1869, Roebling died. His son Washington, also a trained engineer, took over the project, which took its toll on him as well. Spending too much time underground during construction, he fell ill. There was too much nitrogen in his blood, and he got what’s now known as decompression sickness (divers call it the bends). He survived but had to watch construction from his apartment.

The Brooklyn Bridge opened in 1883 to even greater fanfare than the Ohio River bridge, which it surpassed as the longest in the world. It was heralded as a testament to John and Washington Roebling, and cable suspension bridges became a hallmark of American construction, from the Verrazano Narrows in New York to the San Francisco Bay in California. And John Roebling was honored nationwide as the man who made it possible.

In 1908, a statue was dedicated to him in Trenton. Another statue was placed in Covington, Kentucky, in 1988, six years after the Covington-Cincinnati Bridge was renamed the John A. Roebling Suspension Bridge. The bridge closed in 2021 for a $4.5 million renovation, reopening to traffic in April 2022.

Historical markers commemorate Roebling in Cincinnati and Kentucky, as well as Saxonburg, Pennsylvania, and Trenton, New Jersey, where his cable factory was. In unveiling the Trenton statue, New Jersey Gov. Edward C. Stokes said the honors were superfluous.

“His works are his monuments,” Stokes said. “In the East the memorial of his genius links together the divided sections of the metropolis of our country and looks down upon the commerce of the world. In the North it spans Niagara’s mighty cataracts and makes a pathway between two nations. In the West, his early home, the waters of the Ohio and other streams are crossed by suspended highways fashioned by his talent and skill. So long as these shall stand or the principle of their construction be observed, his fame is secure.”

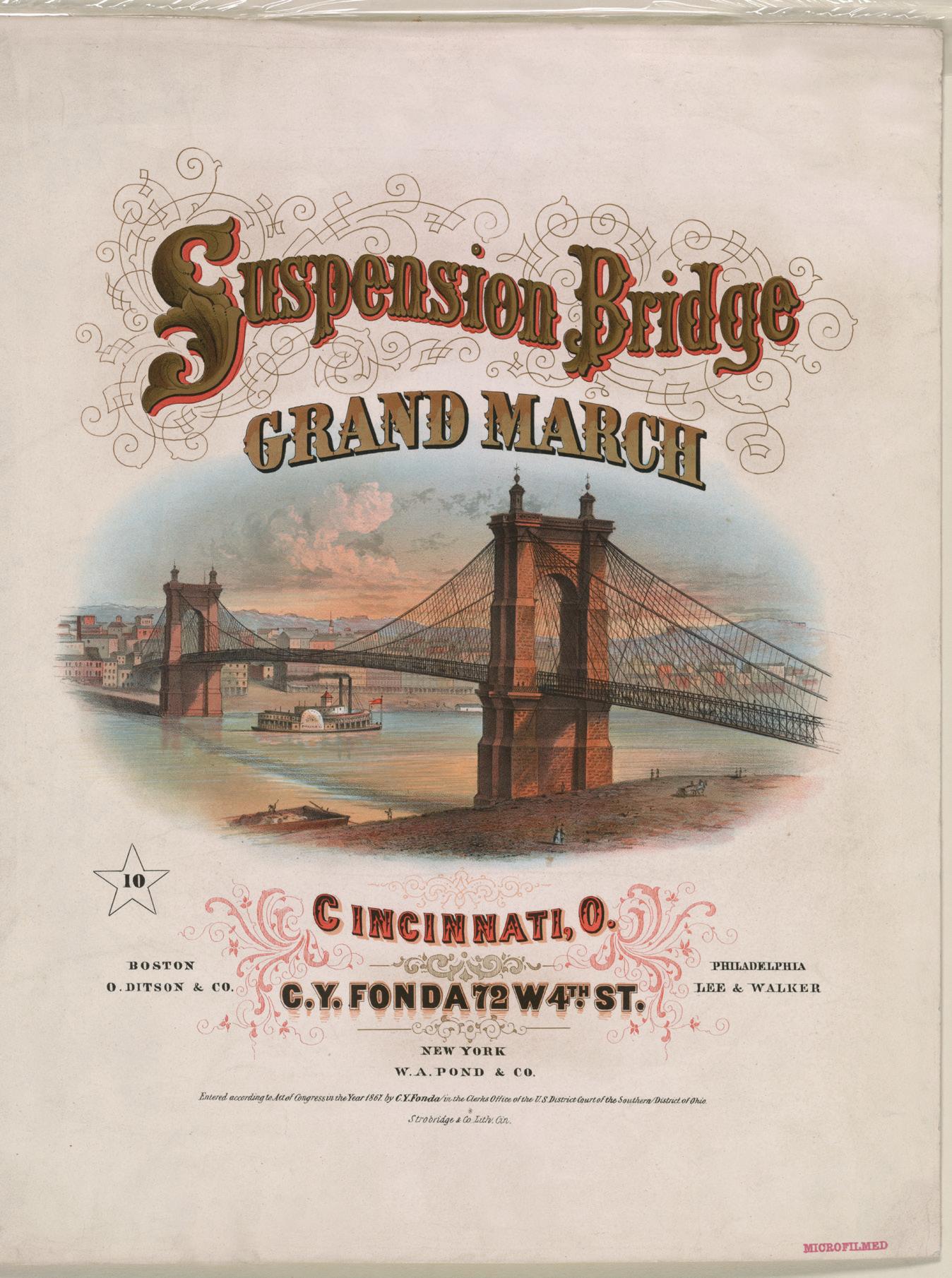

John A. Roebling (left); illustrated title page to sheet music for Henry Mayer’s “Suspension Bridge Grand March,” which celebrated the opening of the landmark (right)

SMALL-TOWN HOLIDAYS

From a volunteer effort that illuminates downtown Cambridge to a museum on Medina’s Public Square dedicated to Christmas memories, these places and events embody the spirit of the season.