39 minute read

ABDUCTED

the parthenon sculptures ABDUCTED

TEXT: DUNCAN HOWITT-MARSHALL

Advertisement

© SHUTTERSTOCK

TEMPLE OF ATHENA The Parthenon, visual centerpiece of the Athenian Acropolis, amid the scattered architectural remains of shrines and dedications that once adorned the Sacred Rock.

THE MARKET Neoclassical pediments adorn the facade of the where a sign reads “Neoclassical pediments adorn the facade of the where a sign reads “Central Food Arcade”. Central Food Arcade”.

CHARIOTS OF THE GODS Surviving sculptures from the east pediment of the Parthenon, portraying the heads of three horses from the chariot of Selene, goddess of the moon, descending through the bottom of the pediment.

ON A LATE AUTUMN DAY IN 438 BC, as the sun neared the glistening sea on the horizon, Pheidias gently ran his fingers along the thick neck of the horse. He slowly traced the vertical lines of its taut musculature up towards the curving head and, with squinted eyes, smiled in satisfaction. It was a masterpiece of high-relief sculpture, made from white crystalline marble quarried from nearby Mount Pentelicus, just north of the city. His skilled craftsmen, Alkamenes, Agorakritos and others, had done all of the initial work, carving out the relief and main features of the galloping animal and its young rider, but he, as the overseer (episkopos) and master sculptor, was there to add the finishing touches. Like all great artists, he was a stickler for detail. He wanted his craftsmen to create the impression that their sculptures could come alive at any given moment and step out of the frieze.

High up on the scaffolding on the western side of the cella, the inner chamber (naos) of the Parthenon temple, beams of soft light skipped over the deeply cut lines, curves and folds of the sculpted figures, catching the shadows and giving the impression of subtle movement. Renowned for his colossal bronze statue of the goddess Athena Promachos (the “Defender”) that guarded the entrance to the sacred rock of the Acropolis, Pheidias, now 43 years old, walked along the marble frieze, surveying the rank and file of carved horsemen. Divided into ten ranks, they represented the ten tribes of Attica. Almost all the riders were depicted as beardless youths, dashing cavalrymen in the prime of life: a conscious display of the power and vitality of the great state of Athens, and a memorial to the brave Athenian warriors who had fallen in the Battle of Marathon against the Persians 52 years earlier.

As the goat tallow torches flickered in the fading light, Pheidias and his craftsmen were busily finishing their Herculean task. Carved in situ around the four outer walls of the cella of the gigantic Parthenon, the largest and most impressive temple to Athena in the Greek world, the 160-meter-long sculpted frieze was close to completion. Consisting of 378 figures and 245 animals, it told the story of the Panathenaic Procession, a religious event that took place in the city every year to commemorate the birth of the goddess. The planned sculptural decorations for the other parts of the temple – the pediments and metopes – would represent the usual fare of Olympian gods and scenes from myth and legend, but the figures on the frieze were different, quite unlike anything that had been done before. Without a doubt, this was Pheidias’ masterstroke. He had overseen the creation of a unique artistic narrative that represented the Athenians themselves; not gods or heroes, but mortals, brave and audacious participants in the first great democracy.

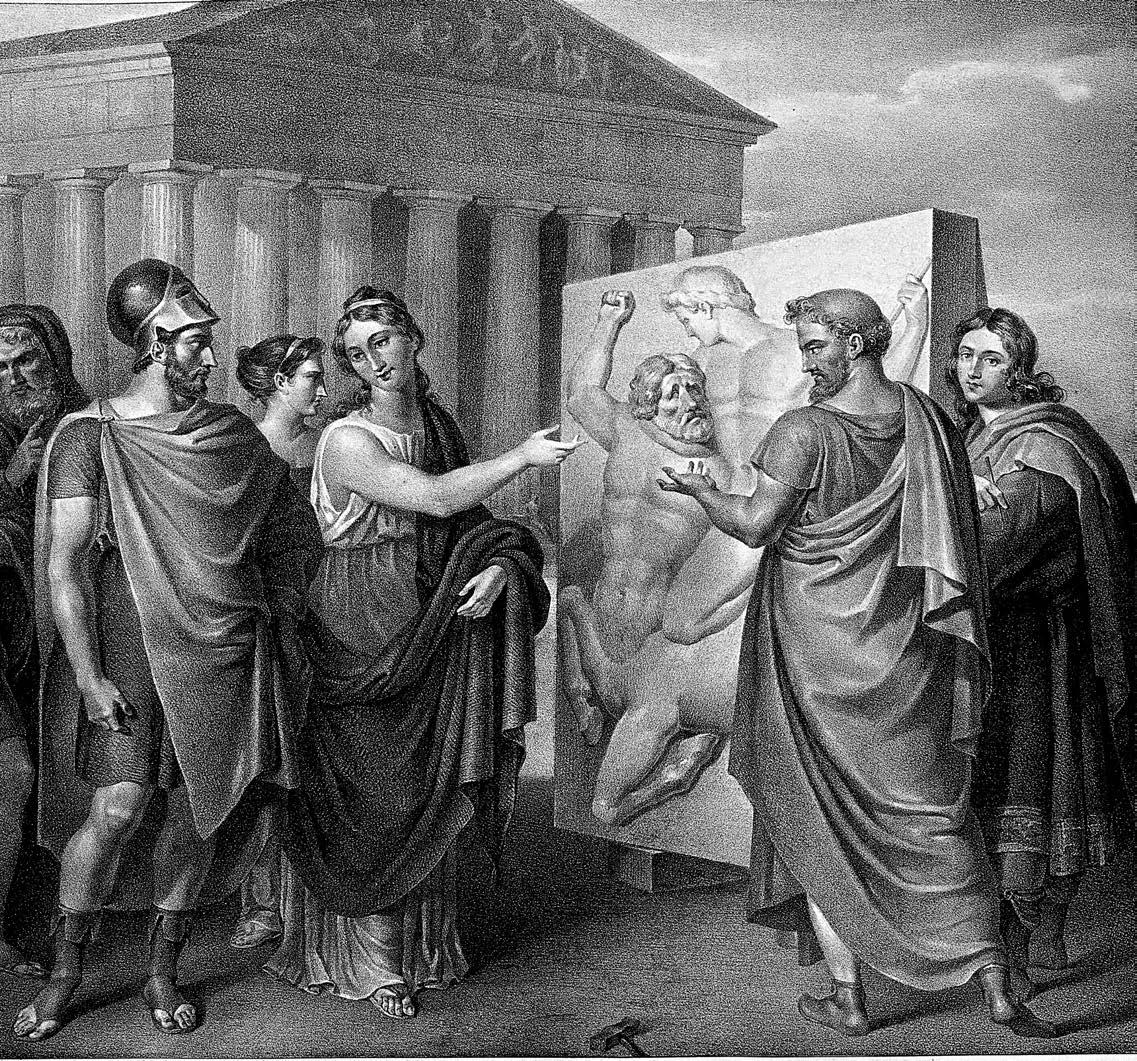

THE AGE OF PERICLES Athenian statesman and general, Pericles (c. 495-429 BC) and his companion Aspasia, directing Pheidias’ work on the Parthenon sculptures. Pericles launched the monumental building program on the Acropolis in the mid-5th century BC.

THE SCULPTURES

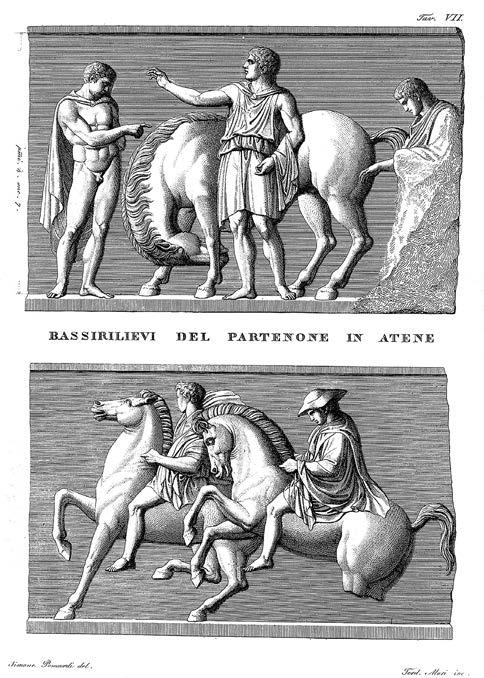

A CAVALCADE IN STONE Young cavalrymen taking part in the Panathenaic Procession, the annual celebration of the birthday of the goddess Athena. Marble relief (Block XLII) from the north frieze of the Parthenon, on display in the British Museum.

© THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

IN CONTEXT

TODAY, NEARLY 2,500 YEARS LATER, the Parthenon stands as one of the most magnificent and best-known monuments in the world, a lasting reminder of the artistic and cultural achievements of the ancient Greeks, and a universal symbol of Western civilization. Inscribed in 1987 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, along with the other monuments of the Acropolis, the building was originally adorned with hundreds of beautifully crafted sculptures, made entirely of locally sourced Pentelic marble. Conceived and sculpted between 447 and 432 BC under the watchful eye of Pheidias, the Parthenon sculptures were not intended as freestanding works of art. Instead, they functioned as an integral and highly symbolic part of the monument, depicting the founding stories of the city and people of ancient Athens. For his overarching theme, Pheidias chose the eternal struggle between order and chaos, a powerful metaphor for the recent wars between the civilized Greeks and the barbarian Persians; a lengthy conflict, including the seismic battles of Marathon (490 BC) and Salamis (480 BC), from which the Athenian-led Greek forces had, against all odds, emerged victorious.

Following the end of the Persian Wars in 479 BC, Athens was the most powerful city state in Greece. A year later, it became the self-appointed head of a large tribute-paying confederacy that defended the Aegean against further Persian aggression. The Delian League, as it was known, originally kept its treasury on the sacred island of Delos in the heart of the Cyclades, but, in 454 BC, the Athenian Assembly had it transferred to Athens itself, to be kept on the Acropolis. It was a bold move; one that signaled the beginning of the Athenian maritime empire. Pericles, a highly respected military leader and orator in the assembly, argued for revenue from the league’s treasury to be put aside for an immense building program on the Acropolis that would make the city the envy of the known world.

The still-standing monuments of the Athenian Acropolis, including the Propylaea (monumental entrance way), the Temple of Athena Nike, and the Erechtheion, all built in the second half of the 5th century BC, are a testament to his great vision. This 50year period, a golden age for ancient Athens, is commonly referred to as the Age of Pericles, and the Parthenon, with its richly carved sculptures, was its crowning glory.

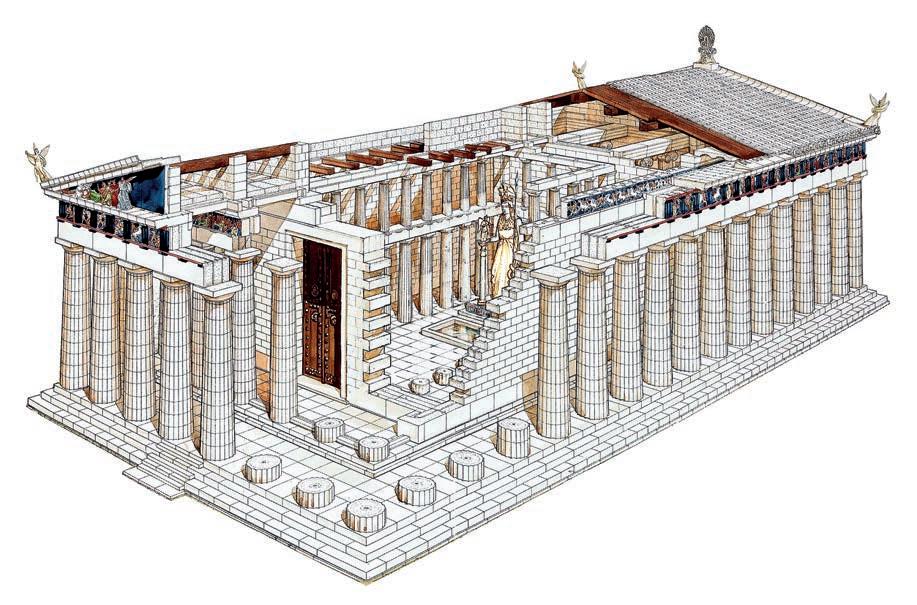

The Temple of Athena Parthenos (the “Virgin”) – the Parthenon – chief temple of the goddess Athena, is a masterpiece of architectural design and engineering. Built between 447 and 438 BC by the great architects Iktinos and Callicrates, it became the center of religious life in the city and a powerful and enduring symbol of Athenian democracy. It was the largest and most lavishly decorated temple that mainland Greece had ever seen.

Pheidias’ once brightly painted sculptures atop the Parthenon’s forest of columns represented a high point in Classical Greek art. The restless swirl of figures not only commemorated the history and mythological foundations of the city of Athens, they were a glorious manifestation of democracy itself, with every finely carved figure a tribute to the primacy of the individual in this bold, new system of government – the first of its kind in the ancient world.

STUDIES IN ANCIENT ART Detailed drawings of sculptures from the Parthenon’s west pediment by renowned archaeologist, painter and writer, Edward Dodwell (1767–1832).

THE PEDIMENTS For the large triangular pediments on the east and west façades of the temple, Pheidias and his sculptors rendered 50 over-life-sized figures in the round. Above the main entrance, the east pediment showed the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus. The west pediment depicted her famous contest with the sea god Poseidon for the patronship of the city.

THE METOPES Below were the metopes, each one measuring around 1.25 x 1.2 meters. Carved in high relief, they ran around the four sides of the peristyle, just above the columns: 32 on the long sides of the temple facing north and south, and 14 on each of the façades. The metopes depicted popular scenes from Greek mythology: the Gigantomachy, the Amazonomachy, the Centauromachy, and the Trojan War. THE FRIEZE The subject of the frieze was the most characteristic feature of the Parthenon's decorative art. Instead of focusing on mythology, Pheidias created a visual narrative of the Athenians themselves in the sacred act of worship - the Panathenaic Procession. Measuring 160 meters, the frieze ran around all four sides of the temple between the outer colonnade and the inner cella.

Scan here for more information on the art and architecture of this monument.

A TURBULENT HISTORY

THE PARTHENON STOOD as a place of worship of the goddess Athena for 900 years before its conversion in the 6th century AD to a Christian church dedicated to the Virgin Mary – the Church of Parthenos Maria. It served as a church for nearly 1,000 years, becoming the fourth most important pilgrimage destination in the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire after Constantinople, Ephesus and Thessaloniki. Since then, it has been a mosque, an armory, part of a fortified garrison and, now, a famous ruin. In a region that is so seismically active, it is a testament to the solid rock of the Acropolis and the material and quality of construction that the building itself remains standing after nearly two and a half millennia.

The present state of the monument is largely a consequence of human actions and interventions. In antiquity, while it was a still a place of cult worship for Athena, the most destructive event was the great fire of AD 267. The Heruli, a Germanic tribe from the north, sacked Athens and set the Parthenon ablaze, destroying the huge wooden beams of the roof and most of the inner facade of the cella. During its conversion to a church in the early Christian period, the entrance on the east side of the building was blocked and reworked into a semicircular apse, the main entranceway placed at the western end. Marble structures on the long sides of the building, including six blocks of the sculpted frieze, were removed to make way for windows. Christian inscriptions were carved into the columns, icons were painted on the walls of the cella, and other decorative sculptures were removed, deemed inappropriate subject matter by the ruling clergy. Under Latin rule, it became a Roman Catholic church of Our Lady, and a bell tower containing a spiral staircase was constructed in the southwest corner of the cella.

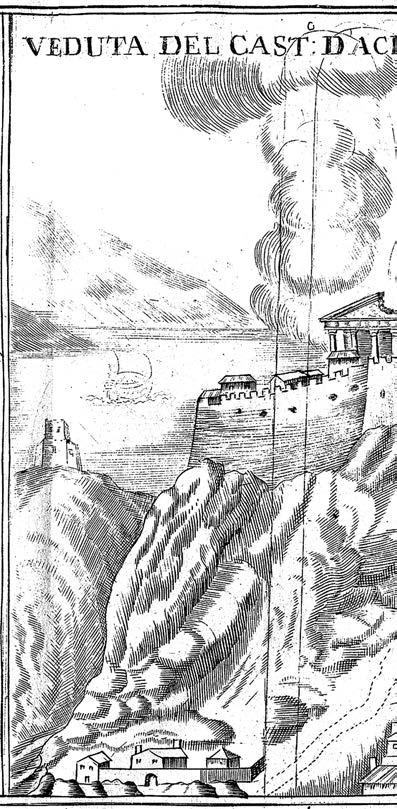

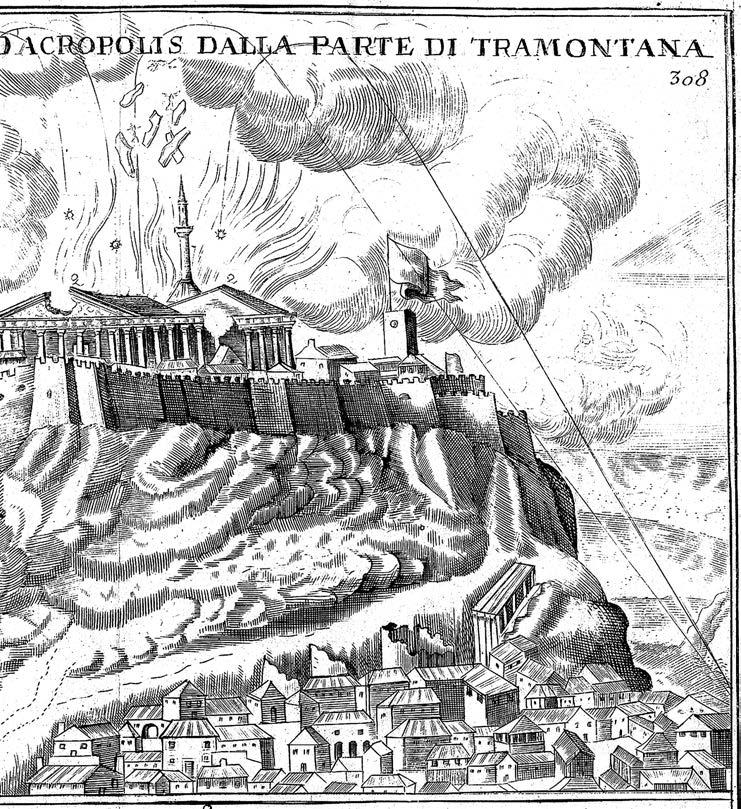

Sometime before the end of the 15th century, during the Ottoman period, the Parthenon was converted into a mosque on the orders of Sultan Mehmed II. The Catholic bell tower was extended upwards and turned into a minaret and the Christian altar was removed. Iconography of Christian saints and martyrs were whitewashed, but many of the surviving sculptures from the pediments, metopes and frieze were left alone. The Turkish explorer and travel writer Evliya Çelebi, visiting the site in 1667, was awestruck by the Parthenon’s beauty: “a work less of human hands than of heaven itself, it should remain standing for all time.” During this time, a number of important studies were made on the sculptures, including sketches by the French artist Jacques Carrey in 1674. Carrey’s detailed drawings provide the most comprehensive evidence of the sculptures prior to the disastrous events that were soon to follow.

By far the most extensive damage occurred on the night of September 26, 1687. During the Morean War (1684–1699), Venetian forces, under the command of Francesco Morosini, marched on Athens and besieged the Acropolis, then an Ottoman fortress. On that ill-fated night, a Venetian mortar shell fired from nearby Filopappos Hill struck the Parthenon and ignited the gunpowder that was being stored inside. The sheer force of the explosion split the ancient temple in two, destroying the roof and central part of the building, and reduced the large sections of the cella walls to rubble. Threefifths of the sculptures from the frieze

ATHENS ABLAZE The destruction of the Parthenon during the Venetian siege of Athens, September 1687. Contemporary Italian engraving.

© VISUALHELLAS.GR

and metopes crashed to the ground while 14 columns from the north and south peristyles collapsed. The explosion showered marble fragments over a wide area, destroying homes clustered around the slopes of the Acropolis, and killing nearly 300 people.

The building sustained more damage in those few catastrophic moments than in the previous 2,000 years. In the aftermath, when the Venetians had overrun the citadel, Morosini, who would later go on to become the doge of Venice, looted the site of its larger surviving sculptures. He even attempted to remove the statues of Poseidon and Athena’s horses from the west pediment, but both were destroyed when the pulley system his soldiers were using snapped. Within a year, Morosini and his forces withdrew from Athens with the ignominious honor of having ushered in the latest phase of the Parthenon’s history: that of a famous ruin.

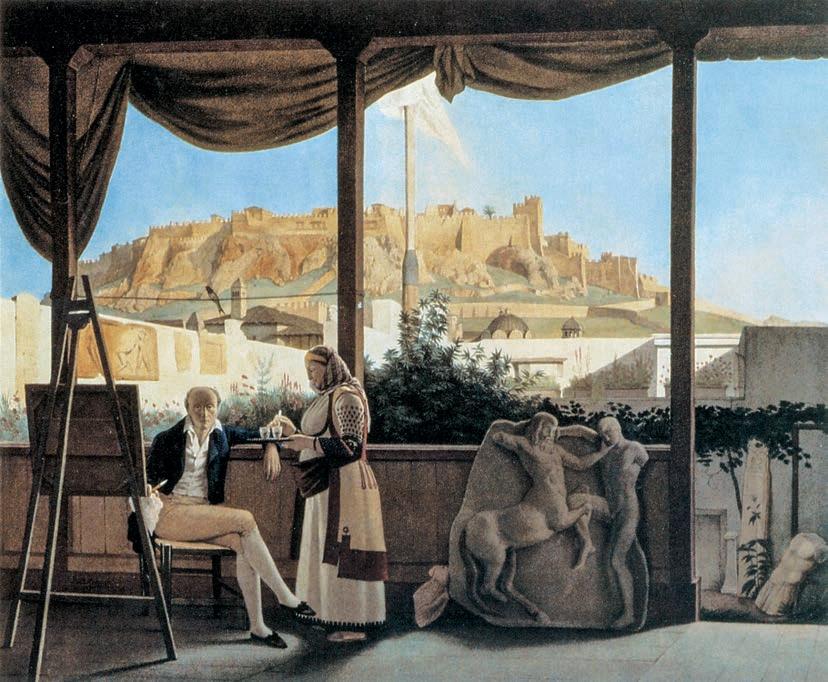

Over the following century, large marble fragments from the partially destroyed Parthenon were recycled as building material for the renovated Ottoman garrison. Surviving pieces of the decorative sculpture were illicitly sold to travelling Europeans, fascinated by the art and architecture of Classical Greece. This Classical centrism cultivated in the consciousness of Western Europeans during the late 17th and 18th centuries, especially in Britain and France, was a double-edged sword. Not only did both nations see themselves as modern-day inheritors of ancient Greece and Rome, but the popularity of Classical literature among the educated classes, paintings and drawings of ruins and the early publications of antiquities by the nobleman-scholars of the Society of Dilettanti also sparked a rise in philhellenism which, in turn, aroused much sympathy and support for Greek independence. Nevertheless, it opened up an insidious path to the wanton removal of antiquities to adorn personal collections and buildings at home, and the ruined Parthenon was the primary target.

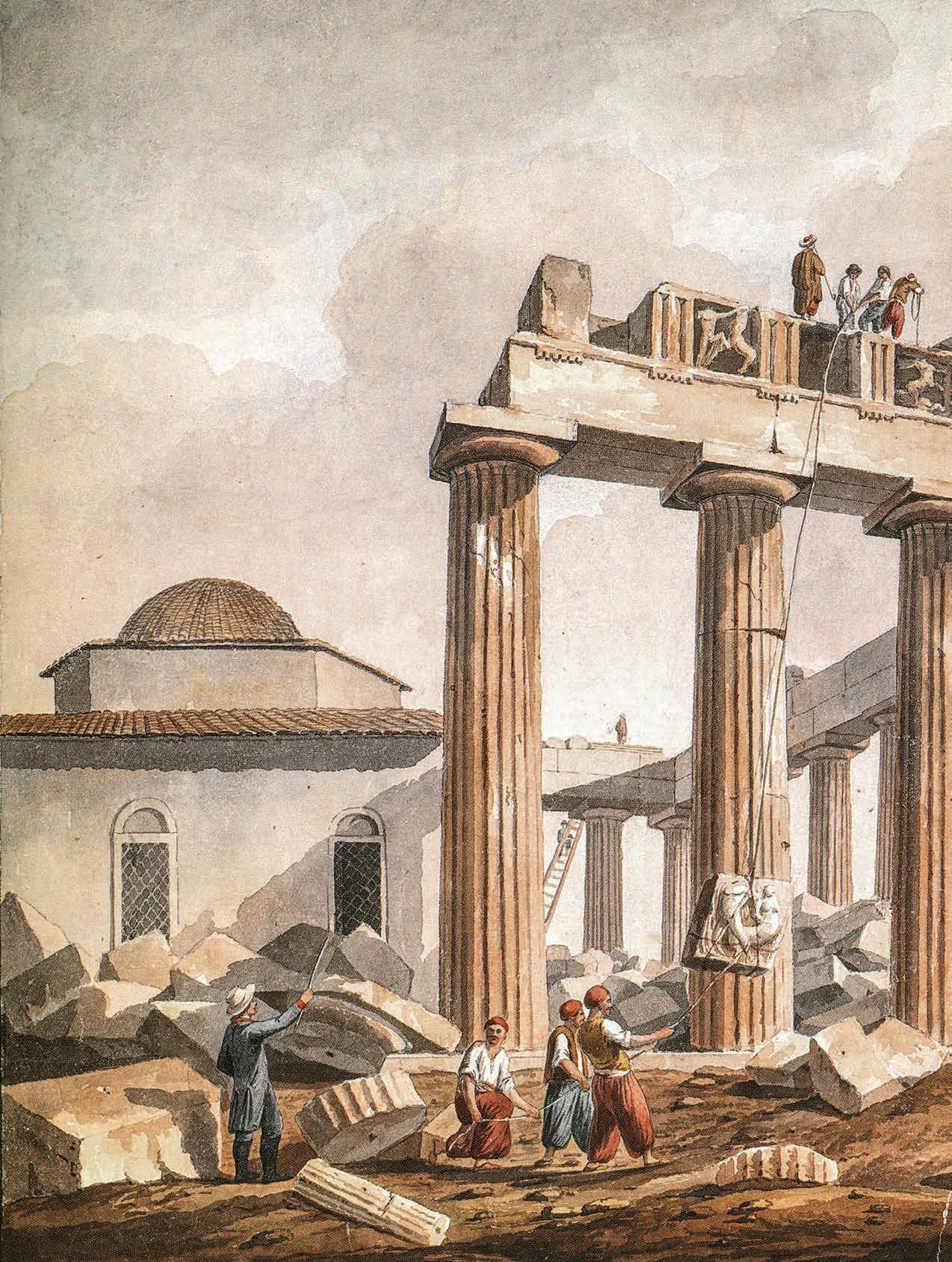

DISMEMBERING THE MONUMENT The removal of Parthenon sculptures by agents of the British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin. From the book “In Search of Greece,” catalogue of the Exhibit of Drawings at the British Museum by Edward Dodwell and Simone Pomardi, from the Collection of the Packard Humanities Institute, 2013.

Enter Lord Elgin

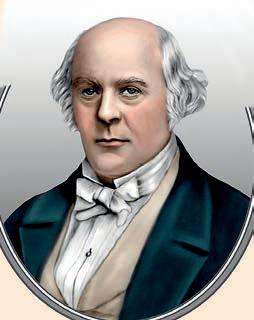

IN OTTOMAN-RULED Greece at the turn of the 19th century, the recently appointed British ambassador to the Sublime Porte of Constantinople (Istanbul) arrived in Athens with one thing on his mind: the Parthenon sculptures. That man was Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, a career diplomat with an insatiable appetite for Greek antiquities. In his entourage, often overlooked in discussions about the removal of the Parthenon sculptures, was Lord Elgin’s personal chaplain and private secretary, the Reverend Philip Hunt, a wily negotiator and, like Elgin, a keen antiquarian. The third man was the Neapolitan court painter, Giovanni Battista Lusieri, employed to make casts and drawings of the sculptures.

From 1801 to 1804, Elgin and his associates not only stripped the sculptures from the Parthenon, they helped themselves to one whole Caryatid (sculpted female figure serving as a column) from the veranda-like porch of the Erechtheion, four slabs from the parapet frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike, and other pieces from the Propylaea. In all, Elgin oversaw the removal of more than half of the surviving sculptures from the Acropolis monuments, either hacked off or simply sawn into smaller pieces for ease of shipping, causing irreparable damage in the process. What were his motives? And why dismember an already existing monument, albeit a ruin?

© GENNADIUS LIBRARY - AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS

CLASSICAL-CENTRIC WESTERN EUROPEANS The view of the Acropolis from the house of French consul M Fauvel. Oil on canvas painting by Louis Dupré, 1819.

Before taking up his post as ambassador to the seat of the Ottoman Empire, an appointment that he had enthusiastically lobbied for, Elgin approached British government officials about the acquisition of drawings and plaster casts of surviving sculptures from the Acropolis monuments; a request that was immediately turned down. At the time, he had been overseeing the redesign of Broomhall House, the family home of the Earls of Elgin in Dunfermline, Scotland. Chief architect on that project was Thomas Harrison, an admirer of Classical Greek architecture, who encouraged Elgin to use his elevated position in the diplomatic service to bring back drawings and casts to be used to influence the design and aesthetic of the country house.

Without official backing from the British government, Elgin decided to go it alone. When he arrived in Greece in 1800, Athens was a ramshackle city of some 10,000 souls, living in poorly built houses around the slopes of the Acropolis. His arrival ignited a great deal of excitement among the local population, hoping that he would create jobs and generate wealth in the impoverished city.

His initial aim was to draw and make casts of the 5th century BC sculptures, as requested by Harrison. At the time, the Athenian Acropolis was still an Ottoman stronghold under the control of the dizdar, the fortress commander. Alongside him was the voivode, the governor of the city and official representative of the sultan, Selim III. Both were well aware of the fascination and allure the monuments of

the Acropolis had on Western visitors, especially young gentlemen-scholars on the obligatory grand tour, and neither were opposed to selling the odd piece of sculpture to line their own pockets – an activity that was officially forbidden under Ottoman law. Nevertheless, the citadel was a heavily fortified military site, and Elgin’s first request to sketch the monuments was turned down. Apprehensive about Elgin’s intentions, the dizdar demanded he obtain formal permission from the top, a royal decree, or firman, from the sultan himself.

Leaping to the task, Elgin navigated the labyrinthine layers of Ottoman officialdom in Constantinople and lobbied the sultan for special permission to gain unfettered access to the Acropolis and its monuments. What happened next is crucial to our understanding of the legality of Elgin’s actions.

He claimed to have obtained the official firman in May of 1801, allowing him to erect scaffolding, draw and make molds of the sculptures, but was unable to produce the original document to the officials in Athens. In its place, he presented an English translation of an Italian copy made at the time, deemed insufficient by the dizdar and voivode. Elgin’s associate Reverend Hunt, a skillful negotiator, then requested a second firman, which he claimed was issued in July of the same year. An Italian transcript of this document still exists in the archives of the British Museum, but its authenticity as a copy of an official firman has been questioned by experts on the diplomatic language used by Ottoman authorities of the period. The wording of the document, not altogether clear, granted Elgin permission to “take away some [or ‘a few’] pieces of stone with old inscriptions or figures thereon, that no opposition be made thereto.”

A landmark 1967 study by British historian William St Clair, “Lord Elgin and the Marbles,” concluded that the sultan likely meant the removal of artefacts that had fallen to the ground and/or been found in excavations at the site, not the artworks still adorning the temples. Nevertheless, in Elgin’s view, it amounted to official permission to remove the sculptures from the Parthenon itself.

Presenting the alleged firman to the voivode in Athens, along with the customary bribe, Elgin and his associates immediately set to task erecting the scaffolding and removing the statues and reliefs from the Parthenon. In August of 1801, the British scholar and travel writer Edward Daniel Clarke was an eyewitness to the destructive removal of the metopes. In his “Travels Part II,” he wrote that the dizdar protested their removal but was bribed to allow it to continue:

“We saw this fine piece of sculpture raised from its station between the triglyphs: but while the workmen were endeavoring to give it a position adapted to the line of descent, a pair of adjoining masonry was loosened by the machinery; and down came the fine masses of Pentelican marble, scattering their white fragments with thundering noise among the ruins. The Disdar, seeing this, could no longer restrain his emotions; but actually took his pipe from his mouth, and, letting fall a tear, said in a most emphatic tone of voice ‘Telos!’ [‘Enough!’], positively declaring that nothing should induce him to consent to any further dilapidation of the building.”

In a recent interview, the Honorary Director General of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage in Greece, Elena Korka, an expert on the Parthenon sculptures, asserted that Elgin became increasingly avaricious and used whatever means possible to acquire the sculptures: “He circulated rumors that he had a ‘firman’ from the sultan, when in fact he had a letter from an official not authorized to give permission.” It's important to note that the original version of the document Elgin claimed was a firman, surrendered to Ottoman officials in Athens at the time, has never been found.

COVETOUS COLLECTOR Portrait of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, later in life.

Sale to the British Museum

THE EXCAVATION AND removal of the sculptures and their shipment to Britain was finally completed in 1812, at huge personal cost to Elgin. In total, he paid an estimated £75,000, equivalent to nearly £5 million in today’s money. He intended for the sculptures to adorn Broomhall, his home mansion in Scotland, but a costly divorce from his wife, Mary Nisbet, in 1808 forced him to seek buyers for the sculptures to settle his debts.

Elgin’s initial efforts to sell the collection to the British Museum were unsuccessful, and Britain’s Parliament, conscious of public criticism, showed little interest in stepping in to take them off his hands. His chief critic was the English poet and peer, Lord Byron, who denounced Elgin as a vandal and immortalized the heinous act in his vitriolic poems The Curse of Minerva and Childe Harold's Pilgrimage. Byron would later go on to become one of the greatest supporters of the Greek Revolution, taking an active role in the armed struggle before dying in Messolongi in 1824.

The subject of the removal of the Parthenon sculptures remained deeply controversial, with scholars, artists and poets taking opposing sides in the public debate. But with growing public interest in Classical Greek art and architecture, the British Parliament soon reconsidered its position. Following an investigation, a parliamentary hearing in 1816 exonerated Elgin’s actions and voted 82–30 in favor of purchasing them “for the British nation.” The debate concluded that Elgin was right to remove the sculptures as the Ottoman Turks viewed the monuments with apathy, and large quantities of marble had already been used to build the military

garrison. Even so, Member of Parliament Hugh Hammersley, who voted against the motion, proposed that “Great Britain holds these marbles only in trust till they are demanded by the present, or any future, possessors of the city of Athens; and upon such demand, engages, without question or negotiation, to restore them.”

Following their sale to the British government for the sum of £35,000, less than half of what it cost Elgin to procure them, the sculptures passed into the trusteeship of the British Museum, where they were put on display to the general public as the “Elgin Marbles,” soon drawing large crowds. They were moved to the specially constructed Elgin Saloon in 1832, where they later underwent several destructive attempts to clean the dust and soot from the deteriorating marble surfaces. In 1838, while art conservation was still in its infancy, scientist Michael Faraday applied carbonated and caustic alkalies to loosen the dirt, followed by a diluted solution of nitric acid. This not only discolored the marble but also left much of the grime embedded in its cellular surface.

More destructive cleaning was carried out a century later in 1937-1938 at the instruction of Lord Duveen, a controversial art dealer who was financing the construction of a new gallery at the museum to exhibit the sculptures. This was done under the false belief that the sculptures were originally a pure, brilliant white. Made from Pentelic marble, the surface would have gradually acquired a color similar to the soft hue of honey when exposed to air, referred to as its natural patina. Using metal scrapers, wire brushes, chisels and highly abrasive carborundum stones, a team of masons worked to remove the patina, scrapping away as much as 2.5 mm of the original surface. To make matters worse, it is known that the sculptures were originally painted with bright colours. As a result of the excessive cleaning, future scientific studies will no longer be able to determine their original color.

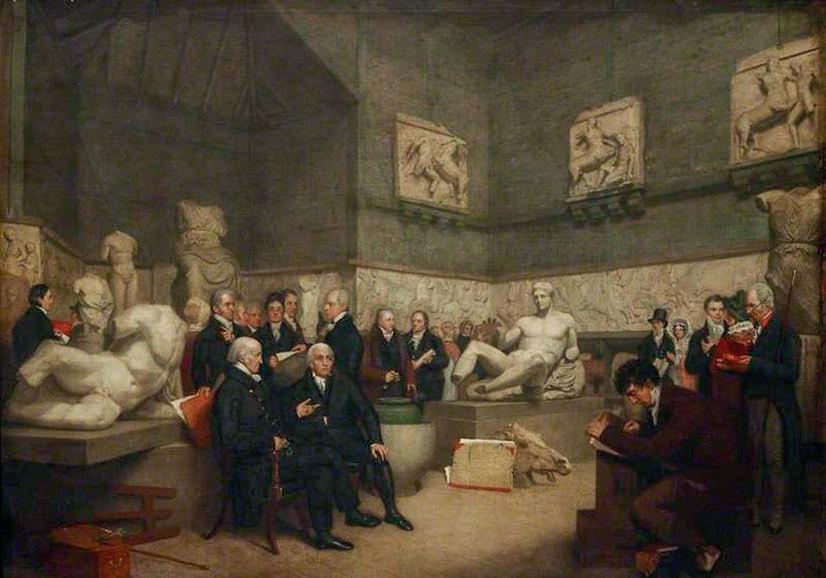

THE PARTHENON SCULPTURES IN LONDON The Temporary Elgin Room at the British Museum. Oil on canvas painting by Archibald Archer, 1819. Below: Statuary from the east pediment of the Parthenon, on display in the Duveen Gallery at the British Museum.

THE CAMPAIGN

UNDER THE BLUE SKY OF ATTICA The Parthenon Gallery on the third floor of the Acropolis Museum. Statuary from the west pediment in direct alignment with the Parthenon.

FOR THEIR RETURN

THE PARTHENON IS the ultimate symbol of Greek cultural heritage and identity, one that is important not only for the people of modern Greece, but for Europe and for all humanity. Two and a half millennia ago, the monument and its sculptures, taken as a whole, celebrated the victory of Athenian democracy over the forces of chaos and barbarism, a victory that sparked the development of the creative arts, philosophy and science as we know them today. As such, the Parthenon is a celebration of the achievements of a free and democratic people – the cornerstone of the Western cultural ideal.

Following independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1832, the newly formed Greek state embarked on a series of campaigns to restore historic monuments and retrieve looted antiquities. The spiritual revival of the Greek people following nearly four centuries of oppression by the Ottoman Turks became closely interconnected with the survival of ancestral relics, especially those from the golden age of Periclean Athens – an ideological orientation to the Classical Greek past. The Neoclassical Bavarian architects who worked for Greece’s first king, Otto, played a decisive role in the preservation of ancient Greek monuments, and appeals were made by successive Greek governments for the return of looted artworks. In the case of the Parthenon sculptures, the first such appeal was made in 1842.

Over the course of the 19th century, further requests were repeatedly turned down by the trustees of the British Museum, citing their legal “ownership” of the sculptures. The devastating world wars of the early and mid-20th century put everything on hold until, in the early 1980s, the Greek Minister of Culture, Melina Mercouri (19201994), brought the plight of the Parthenon sculptures to the attention of the international community.

Mercouri herself was an incredibly dynamic figure. A world-famous singer and Academy Award-nominated actress, she gained further prominence as a political activist during the dark years of the Greek dictatorship, from 1967 to 1974. In later life, she became increasingly involved in politics, and was appointed Minister of Culture from 1981 to 1989, and briefly again in 1993 to 1994. She was deeply passionate about the protection and enhancement of Greek cultural heritage and its promotion to the world, using her position to make an ardent plea for the return of the Parthenon sculptures at the UNESCO World Meeting of Ministers of Culture in Mexico in 1982.

In a speech to the assembled ministers, Mercouri made a powerful argument for their reunification in Athens, and announced the Greek government’s intention to formally request their return from the British Museum:

“The day may come when the world will conceive of other visions, other notions about ownership, cultural heritage and human creativity. And we fully appreciate that museums cannot be emptied. But I would like to remind you that in the case of the Acropolis Marbles we are not asking for the return of a painting or statue. We are asking for the restitution of part of a unique monument, the particular symbol of a civilization. And I believe that the time has comes for these Marbles to come home to the blue skies of Attica, to their rightful place, where they form a structural and functional part of a unique entity.”

Mercouri’s passionate rallying cry was heard around the world. Her campaign was no longer the struggle of the Greek people or government but of the global community, as scholars, heritage professionals and others joined the ever-growing chorus for the sculptures’ return. Since then, 21 national committees spanning 19 countries have been established, most recently Luxembourg in 2020, each one raising awareness of the long-standing issue in their respective nation, galvanizing popular support and applying pressure

"OUR SACRIFICES" Melina Mercouri on an official visit to the British Museum. The actress/political activist instigated the campaign for the return of the Parthenon sculptures in 1982 when serving as Greece’s Minister of Culture.

on the British Museum and UK government officials. Working under the collective umbrella of the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures (IARPS), the committees work closely with the Greek authorities, hosting regular conferences and meetings, and supporting the ongoing policy of cultural diplomacy. In the words of Professor Louis Godart, former chair of the International Association (2016-2019): “anyone who loves Greece and democracy must fight for the repatriation of Pheidias’ sculptures.”

© VISUALHELLAS.GR

The tireless work of IARPS, including the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, chaired by Dame Janet Suzman, appears to be having an overwhelmingly positive impact. Opinion polls in the UK in recent years suggest that significantly more British people support the sculptures’ return to Greece than oppose it. Indeed, a 2014 poll conducted by the Guardian found that 88 percent of respondents agreed that the Britain Museum should return the sculptures. There is clearly a groundswell of public opinion in favor of their return.

WHERE ARE THE PARTHENON SCULPTURES TODAY?

Today, only 50 percent of the original Parthenon sculptures survive. Of these, a small number remain in situ on the monument, silent survivors of its long and turbulent history, and just under a half are on display in the purposebuilt Acropolis Museum in Athens, which opened in 2009.

Outside of Greece, small fragments are in the collections of the Louvre in Paris, the National Museum of Denmark, and museums in the Vatican City, Vienna, and Würzburg,

Germany. The remaining half are on display in the British Museum, where they have been on permanent display since 1817. They consist of 17 figures from the statuary of the east and west pediments, 15 of the original 92 metopes, depicting the battle between the Centaurs and Lapiths, and 75 meters of the 160-meter-long frieze.

So, why the delay?

THE TRUSTEES OF the British Museum have continued to assert clear legal title to the Parthenon Sculptures since 1816, citing their legal acquisition by Lord Elgin under the laws pertaining at the time. Supporters of the British Museum’s position also argue that the sculptures receive six million visitors per year in London as opposed to one and a half million at the Acropolis Museum in Athens. In a statement on the British Museum’s website, the trustees make the following argument:

“The Acropolis Museum allows the Parthenon sculptures that are in Athens to be appreciated against the backdrop of ancient Greek and Athenian history. This display does not alter the Trustees’ view that the sculptures are part of everyone’s shared heritage and transcend cultural boundaries. The Trustees remain convinced that the current division allows different and complementary stories to be told about the surviving sculptures, highlighting their significance for world culture and affirming the universal legacy of ancient Greece.”

Nevertheless, many would argue the display of the Parthenon sculptures in the British Museum is inadequate. Their exhibition in the dimly lit Duveen Gallery gives the false impression that they form a contiguous whole, presenting an unbroken narrative of the mythological and religious scenes depicted in the pediments, metopes and frieze. In reality, they constitute a collection of disembodied, de-contextualized historical artifacts that portray the narrative in piecemeal. This is especially the case for the frieze, portraying the Panathenaic Procession. On the Parthenon, the slabs were originally conceived to run along the outside walls of the cella, but in the British Museum, where they are displayed on the inside of a wall, there is no indication where the missing slabs would have been positioned.

Since 2009, Athens has been home to a world-class, purpose-built museum for the display of cultural artifacts related to the monuments of the Acropolis and its environs. The Acropolis Museum, located on the south side of the Acropolis, has been equipped with state-of-the-art facilities for the conservation and preservation of exhibits, including advanced laser cleaning, and functions as one of the leading research museums in Greece for the study of Classical Antiquity. The specially designed Parthenon Gallery

NICHOLAS STAMPOLIDIS

Archaeologist, Director of the Acropolis Museum

“The Parthenon ... is a whole born into a particular time and place, under a certain light. And everyone in this light should visit the Parthenon and be ‘re-baptized’ in their roots. It’s not just the State and the museum that calls for the return [of the sculptures], it is the monument itself, the Parthenon, the body-symbol that demands its limbs back.”

GEORGE OSBORNE

Chairman of the British Museum, former UK Chancellor of the Exchequer

“There are those who demand the return of items that they believe we have no right to keep. ... Lord Byron thought that the ‘Elgin marbles’ should return to the Parthenon. ... We are open to lending our items wherever they can take care of them and ensure their safe return - something we do every year, inlcuding to Greece.”

DAME JANET SUZMAN

Actress, Chair of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles

“Recent polls suggest public opinion is growing in favor of return, due largely to a greater historical awareness of colonial misdemeanors and a questioning of a dead empire’s right to imagine itself unassailably in the right. The British Museum is behind the curve on this. It has a reputation to save and must go about saving it right now.”

on the top floor of the museum is in direct line of sight with the Parthenon monument itself on the Sacred Rock. With glass walls running from floor to ceiling, the modern gallery allows visitors to view the sculptures in the natural Mediterranean sunlight, configured in the same way as they would have been on the Parthenon. Contrary to their display at the British Museum, the gaps in the marble slabs and figures in the Parthenon Gallery have been deliberately left blank, patiently awaiting the return of their missing brothers and sisters from London.

It's important to remember that these sculptures were never intended to be viewed as freestanding works of art, but as parts of a symbolic whole. Issues of legal ownership aside, experienced in unity, the sculptures represent the highest form of Classical Greek art, and should be seen as an integral part of the Parthenon, their original place of conception and display. Detractors from this point of view fear the return of the Parthenon sculptures would open the floodgates for the repatriation of many more cultural items from the British Museum’s collections, setting a precedent that would empty the socalled “encyclopedic museums” of the Europe and North America.

While it is true that comparable claims have been made by governments around the world for the return of specific cultural items looted during colonial times, most notably in Africa, there is no hard evidence that global museums would be denuded. Instead, the Parthenon sculptures appear to represent a very special case. In a 2018 article in the London-based art and culture magazine “Frieze,” Cambridge classicist and historian Paul Cartledge made the following argument: “The Marbles are unique in that the building they adorned two and a half millennia ago still stands in full view on its mighty Acropolis rock – you see it from every street in the center of Athens.”

Furthermore, the British Museum would greatly benefit by returning the Parthenon sculptures, opening up a new chapter in cooperative partnership with Greece. Not only would it enhance scholarly collaboration between British and Greek archaeologists, conservators, curators and art historians, it would pave the way for exhibitions to be shared and other collections to be offered as long-term loans by Greek museums. It would also improve the British Museum’s somewhat tarnished image abroad, and, by extension, Britain’s global image.

STEPHEN FRY

Actor, writer and philhellene; author of “Mythos: A Retelling of the Myths of Ancient Greece” (2017)

“We are discussing a specific part of an existing building, which we now know can be properly and professionally curated and displayed … Greece made us. We owe them. They are ready for their return and have never needed such morale-boosting achievement more. And it would be so graceful, so apt, so right.”

NADINE

GORDIMER (1923-2014) Nobel Prize winner, writer and political activist

“The Parthenon Gallery in the new Acropolis Museum provides a sweep of contiguous space for the 160-metre-long Panathenaic Procession as it never could be seen anywhere else, facing the Parthenon itself high on the Sacred Rock. But there are gaps in their magnificent frieze, left blank. They are there to be filled by an honorable return of the missing parts from the British Museum.”

CHRISTOPHER

HITCHENS (1949-2011) Journalist, columnist and orator; author of “The Parthenon Marbles: The Case for Reunification” (1997)

“The ‘Elgin line,’ of sculptural partition and annexation, runs through a poem in stone that was carved as a unity and that tells a single story. It even cuts through figures and characters in that story. The body of the goddess Iris is now in London, while her head is in Athens. The front part of the torso of Poseidon is in London and the rear part is in Athens. This is grotesque.”

New momentum

THE BRITISH MUSEUM already has one of the best collections of ancient Greek artefacts on display anywhere in the world, and it is certainly not short of visitor attractions to draw in the crowds. The return of the Parthenon sculptures would in no way diminish that. Setting a good precedent was the return in 2006 of a sculptural fragment from Parthenon’s frieze held in the collection of the University of Heidelberg. The fragment came from the north frieze, depicting the lower foot of “Figure 28” (a thalophoros, a figure holding an olive branch) and part of the garment’s edge. This symbolic act of return constituted the first repatriation of any part of the architectural or sculptural decoration of the Parthenon from a museum outside of Greece. It was followed later that year by the return of an architectural fragment from the Erechtheion from the collection of the Museum for Mediterranean and Near Eastern Antiquities in Stockholm, Sweden. During a special repatriation ceremony in Athens, representatives of the Swedish museum expressed hope that the return of the fragment would send a clear signal to the British Museum.

Efforts for international mediation in the long-standing issue have been ongoing since 1983. Leading from the front, UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property (ICPRCP) has adopted at least 16 recommendations for bilateral negotiations on the Parthenon sculptures, which, among others, call on Greece and the UK to “intensify their efforts with a view to reaching a satisfactory settlement.” In 2013, following a meeting between the Greek Minister of Culture and Sport and UNESCO’s Director-General, UNESCO formally invited the UK Government and the British Museum to enter into mediation talks. The invitation was turned down, two years later, in 2015, citing the same old and tired arguments regarding the British Museum’s legal acquisition and ownership of the sculptures.

But there is hope. In September 2021, auspicious for being the bicentennial year of the start of the Greek Revolution that set Greece on the path to becoming a free and independent state, the Greek government and ICPRCP made a significant breakthrough. During the 22nd session of the ICPRCP in Paris, following intense talks, the committee for the first time acknowledged that the matter is an intergovernmental one, and not one between the Greek state and the trustees of the British Museum. Together with its recommendation, which referred to the poor conditions in which the sculptures are being kept in the Duveen Gallery, the ICPRCP, in full support of Greece’s legal and moral claims, voted unanimously to pass a decision urging the return of the Parthenon sculptures: “The decision of the 22nd session of the ICPRCP’s Commission expresses its strong dissatisfaction with the fact that the issue remains unresolved due to the United Kingdom’s stance. In addition, it urges the United Kingdom to reconsider its position and enter into a bona fide dialogue with Greece, emphasizing the intergovernmental nature of the dispute.”

© GETTY IMAGES/IDEAL IMAGE

OUT OF CONTEXT Statuary from the west pediment of the Parthenon, on display in the Duveen Gallery at the British Museum.

The latest developments and what British voters can do

IF YOU’RE REGISTERED to vote in the UK and you’d like to help the campaign for the reunification of the Parthenon sculptures, we urge you to write to your local Member of Parliament asking them to raise the issue in the House of Commons. It’s important that you stress the issue become an intergovernmental one – one between the Greek state and the UK. As it stands, the UK government blindly supports the position held by the trustees of the British Museum regarding their legal claims of ownership of the sculptures since 1816, and is keen for museum professionals in Greece and the UK to continue to have dialogue. The Greek government, on the other hand, now with the full and unequivocal support of the ICPRCP, continues to press the UK to upgrade the longstanding issue and enter into direct talks at an intergovernmental level.

To break the stalemate, UK voters must petition Parliament to debate and amend the British Museum Act of 1963, which outlines the composition and general powers of the British Museum trustees. The all-powerful trustees exist as a 25-person corporate body, one member appointed by the Queen, 15 by the Prime Minister, four by the Secretary of State and five appointed by the trustees of the Museum. Their role is the general management and control of the British Museum, including the keeping and inspection of collections, and the disposal of objects. A parliamentary debate would allow the House of Commons to carefully consider the issue of the Parthenon sculptures and further reflect on what responsibilities they wish to give to the trustees of the Museum.

Vesting the trustees with the right to voluntarily return the sculptures would affirm the British nation’s respect and admiration for the immense legacy of ancient Greece, promote the indivisibility of Classical Greek art, and enhance the reputation and esteem of the British Museum in the eyes of the world. As such, the repatriation of the sculptures would create a win-win situation. Seizing on present momentum, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis pressed his UK counterpart, Boris Johnson, on the case for reunification. True to form, Prime Minister Johnson’s response reiterated the UK government’s longstanding position that the sculptures were “legally acquired by Lord Elgin ...,” and that the issue is not an intergovernmental one.

In a swift riposte, the Greek premier appealed to Johnson’s self-proclaimed admiration for ancient Greece in an article for the UK's Mail on Sunday: “I believe that the classical scholar in Boris Johnson knows that he has a unique opportunity to seize the moment and make this generation the one that finally reunited the Parthenon Sculptures.” He added that the return of the sculptures would open the door for long term loans to the British Museum of other iconic Greek artifacts. In the immediate aftermath, there was a groundswell of support from media outlets in the UK and around the world in support of the Greek cause.

Despite the stubborn refusal of the UK government to enter into any meaningful dialogue with Greece, the ICPRCP’s potentially game-changing decision gives new hope to the nearly 40-year campaign, especially now that public opinion in Britain has shifted in clear favor of the return of the sculptures to their rightful home in Athens.

ONE FRAGMENT IN LONDON, THE OTHER IN ATHENS Fragments from Block XXVII of the Parthenon's north frieze, adjusted to a plaster cast of the upper part of the original block kept in the British Museum. The scene depicts an apobates race, an equestrian contest related to the mythical origins of Athens.