33 minute read

New Monday

ELEVATIONS

Advertisement

PROJECT: Sharp House ARCHITECT: Marc Thorpe Design LOCATION: Santa Fe

Size: 1,500 square feet Completion: Ongoing

pointing to other recent projects in which he’s designed for climates in Africa using similar ventilation processes and earth brick instead of concrete.

To further keep the Sharp House economical, the roof has been layered with solar panels and areas for water collection that supply a non-potable system. The self-sustaining systems in place are a safeguard in the face of the climate change crisis. Thorpe sys, “Water is a huge issue and will become a great issue as our civilization evolves. You need to be able to harvest water and power your house.”

The roof serves a secondary, much dreamier purpose, too—stargazing. Technically the roof offers access to maintain the solar and water systems. “But you can totally just hang out on the roof and watch the stars,” he says. The use of every surface of the house is an intentional move on Thorpe’s part. “There isn’t really a front or a back,” he says. “In the tradition of Frank Lloyd Wright, he designed his houses with no real entry. It was more a work of art where you’re forced to engage with the house on all sides and explore it like you would explore a piece of sculpture.”

With Sharp House, Thorpe makes an argument for slowing down and appreciating the phenom of interacting with a space. His favorite part of the house? The long ribbon windows. “Those are really unique moments that, through the transition of the day, allow light to cut through the space and create lines that define. It’s a very beautiful moment where you have time to stop and reflect. Why not embrace those moments?” g

The minimalist Sharp House design is for a New Mexico escape on five acres. The house was designed to be as economical as possible in construction, with exposed cast-in-place concrete and large glass exposures to the north and south to allow for solar gain and cross ventilation.

practice

AN ACOUSTICAL SYSTEM INSIDE THE LECTURE HALL IS BASED ON THE GEOMETRY OF WOODEN COMPONENTS, LIKE PIANO BARS, TO CREATE A 3D FRAMEWORK ON THE VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL SURFACES.

Lilian Asperin on Designing Higher Ed Spaces for All

Diversity and wellness are built in to WRNS Studio.

W

When Lilian Asperin, partner at WRNS Stu-

dio, thinks about where she is today, she gets emotional. She’s been doing this work for nearly 25 years, but still it’s sometimes hard to believe. Today she plays a pivotal role in the designing, developing, and decision-making that results in some of the most groundbreaking designs happening in higher education—including the new UC Merced Arts and Computational Sciences Building in Merced, California.

“I come from a biracial background, born and raised in Puerto Rico, so I’ve always wanted to be of greatest service to the greater community, knowing not all of us are the same,” she says. “As a Latinx person, I was part of the 1%. There were not too many of us women going through architecture.”

Asperin is also co-chair of the AIA’s Equity by Design Committee, a group that’s committed to thinking about how architects impact much more than the built environment. They

LILIAN ASPERIN IS PARTNER AT WRNS STUDIO AND COCHAIR OF THE AIA’S EQUITY BE DESIGN COMMITTEE. affect justice, too. “My practice has to do with paying it forward and connecting as many dots as I can—architecture-based education, wellness, opportunity. All of those things to me are synchronous.”

A key goal of the UC Merced project was to offer students an engaging, inclusive campus experience that supports evolving learning modalities with flexible, mixed-use spaces that blend student life with education. The work is part of a Public Private Partnership (P3) delivery model and included a Triple Zero Commitment—zero net energy consumption, zero waste production, and zero net greenhouse gas emissions by 2020. We talked to Asperin about this project and designing for wellness overall.

How does wellness and well-being fit into design?

Wellness, to me, is health. Being healthy, having opportunities, having an ability to see a future for yourself in a profession and a way for you and your family to have generational wealth and knowledge and wisdom is something that we should be all striving toward.

As architects we’re natural pattern-seekers and system-makers. All of these things really have to do with how we nurture ourselves as humans and as networks of communities across generations. And now, making sure there’s justice, that all of these things are working together to elevate gaps where folks have not had the same level of opportunity.

With education it’s the same idea. The more you can turn information into data, data becomes knowledge, then knowledge becomes the reason for your activism. I see them as connected. When I think about higher education I think about: How are people learning? But I also think about how the faculty is teaching. What are people learning? How are campuses coming together, and how is an experience on-campus really building on all those smaller scales of education, like wellness and growing and becoming part of this world?

How do you build that into the design process?

It starts with asking better questions at the beginning and then thinking, “Who else should we be asking?” Are we really engaging the broadest number of people to help us discover? Ask better questions and have a broader group of people to engage with. As architects we need to suspend thinking that we need to have the answer earlier. We need to train ourselves to listen longer and more attentively.

Yes, the physical space is the outcome, but do we have the right ingredients to reach that outcome? The process is a design opportunity. How are we getting to the components? How are we listening? How are we playing things back? That also has to do with equity and diversity and inclusion. We need to create spaces that welcome everyone.

Buildings have a great impact on the environment. I can’t not feel enormous responsibility for healing the planet and making better decisions and, frankly, not building more if we can adaptively reuse space. That’s a better answer—thinking about materials and carbon footprints, thinking about daylight. Do we need energy to turn on the light when you can plan the building in a way that it has more natural daylight?

That whole campus is the youngest campus in the University of California system. By definition, it’s out there—in a town called Merced, which is in the valley. The demographics in the valley are primarily Latinx, and a lot of the students are first-generation. So this building exists as part of a campus that is creating enormous opportunity for generations. It’s exciting.

Thinking about the valley, it’s very hot out there. How do you create a building where people want to hang out? When you hang out on campus you meet people and you learn and you create this whole learning experience. But how do you create a community that has nothing else around it? And how do you create a building that doesn’t harm the landscape and also make sure students and their families have a positive experience?

What about designing in a hot climate?

Because it’s super hot we designed exterior circulation. Our facade to the building envelope is called a brise-soleil, which is a shading device. We use the materials in the depth of the building to create a sheltered environment that’s outdoors. You’re not spending a lot of money conditioning the space, and you work with the natural environment and the winds to create a space where people feel comfortable hanging out in the shade. The brise-soleil is like a habitable space that creates shelter.

And every room has natural light?

Every single space in the building has access to natural daylight. That was really hard to do because there are deep, long spaces and spaces that are simply storage rooms. But if a human goes in there, we were considering a day in the life, so every single room has access to daylight and views, which is a huge commitment to wellness. Why should the professors in the corner office be the only ones who have a pleasant space?

Tell me about the lecture hall.

We designed an acoustical system inside the lecture hall that is based on the geometry of wooden components, sort of like piano bars that create a three-dimensional framework on the vertical and horizontal surfaces. We worked with the local community to find wood that was regional to the valley, and we designed the lecture hall around that species, which celebrates community. We used poplar, a regional FSC-certified wood species, so we can keep the contract and the economic benefits in the region.

How was color important to the UC Merced Arts and Computational Sciences Building?

We talked a lot about the quality of light in the selection of colors. Every color we considered we asked: Is it reflective of heat? The concrete itself is gray, and we left it natural because the lighter the color the more reflective it is, but also we didn’t want to spend any money on painting concrete. Concrete can be very beautiful.

The one color we picked was red; it’s in great contrast to the valley. It’s a very agrarian landscape. In some ways red to us was like the color of energy, like student life and the joy of learning and growing. This sort of celebrated life, and the red is really a good neighbor to green, or the agrarian landscape, and a simple alternative to the blue of the sky. The only dark elements you see are the shadows created by the light.

Talk to me more about your love of concrete.

We love concrete. It’s such an honest material. It’s very sculptural. It’s very tactile. We actually built models to study how we were going to sculpt the concrete. When you look at the project from the front, it’s kind of like a lattice work. And the depth of the lattice work has to do with how much we want to use that to mitigate the sun. The deeper it is, the more shadow it creates, so the shadow is much more comfortable to be under.

We also varied the angle of those columns from floor to floor. As you’re walking down the brise-soleil, it’s a shaded walkway. We have a physical model of it, we reviewed the shop drawings, we looked at the concrete itself to make sure it was the right mix. Sometimes you can get concrete and it could be quite harmful for the environment. We paid attention to what is this material doing? It doesn’t absorb a lot of heat or retain it. It’s a really good—a naturally occurring way of avoiding heat gains or heat loss.

A BRISE-SOLEIL, WITH ANGLED CAST-IN-PLACE CONCRETE COLUMNS, RUNS ALONG THE SOUTH SIDE OF THE BUILDING, OFFERING STUDENTS AN OUTDOOR, SHELTERED GATHERING SPACE AND COMFORTABLE TRANSITION FROM THE QUAD TO THE INTERIOR.

What is the future of design for higher ed spaces? What about indoor/outdoor space?

I’ll share a little from what’s in my head since a (SCUP, Society for College and University Planning) workshop I had this morning. We had a workshop with 60 people and 13 institutional leaders talking about what they’ve learned in the past year, what students need, and how are things changing after COVID. How are we thinking about campuses?

For me, I started thinking not just about indoor and outdoor space, but about designing through another lens. Of course we can design spaces, like a porch, or you can open doors or windows, but campuses are these incredible natural assets. Everybody remembers a beautiful tree they would go to after a class or a park where they used to talk to their professor. I think we should talk to the gardener and the groundskeeping crew. What do they know about the campus that we should be thinking about? Wouldn’t it be wonderful to have class under a tree that’s 100 years old?

If you’re a commuter student and you’re on campus for eight hours, and you have class for three hours, what are you going to do in between? Let’s think about the fact that you’re learning in between classes; you’re learning outside of the classroom. That’s wellness, too, right? Being outside lowers your stress. You’re breathing clean air.

Especially after COVID we love parks again. I think there’s going to be a renaissance. It’s another reason to build less—shouldn’t there be more open landscapes on campuses? I want us to have healthy campuses. Just imagine; maybe there’s a migratory bird path. You wouldn’t see that unless you were sitting out in the yard. And maybe that’s what you want to learn. g

Carol Ross Barney on Designing McDonald’s Flagship Restaurants

How Ross Barney Architects combined sustainability and urbanism for the fast-food giant

BY CAROL ROSS BARNEY

W

When McDonald’s came to Ross Barney

Architects to design their new Chicago Flagship restaurant, they really didn’t talk about sustainability at all—they just wanted a refresh of the building. We started doing the research for the design and found that one of their corporate values is sustainability, but centered more on their supply chain and not on buildings. Because of this corporate commitment we suggested that we design the most sustainable restaurant and achieved a LEED Platinum–certified restaurant.

Chicago Flagship

McDonald’s asked us to work with them on the new Chicago Flagship Restaurant because they were concerned about making an amenity for the city. The site is unusual—a full block in River North—and they were concerned about the public space that it would have and wanted to be a good citizen in their hometown. They also said that “sustainability was their everyday business and that notion was very attractive,” combining sustainability and urbanism.

The new Chicago Flagship celebrates the pure simplicity and enduring authenticity of McDonald’s, welcoming both residents and visitors to a sophisticated yet informal gathering place in the heart of the city.

Green Space

The site is just steps from Michigan Avenue, occupied since 1983 by the iconic “Rock ’n’ Roll McDonalds” that emphasized drive-through services. The new design rebalances car-pedestrian traffic, creating a city oasis where people can eat, drink, and meet. Green space is expanded by more than 400%, producing a new park-like amenity for a dense area of Chicago.

Surrounding the restaurant is a park with an outdoor dining space and permeable pavement, topped with a solar pergola to provide shade and feed energy back into the building and to the grid. We felt that the sustainable aspects of the building had to tell a story—that if it was instructive, people would be more aware of their environment and would want to preserve and protect it.

The green roofs are planted with harvestable trees and native plants. The rooftop orchard contains Honeycrisp and Gala apple trees ranging from 8 to 9 feet tall as well as edible plants, including arugula, broccoli, and carrots—all living within the orchard’s canopy. This food from the rooftop is harvested each fall.

Sustainability Mission in Design

McDonald’s corporate commitment to sustainability is at the core of the new restaurant design. The structural system cross-laminated timber (CLT) is the first commercial use in Chicago and has a lighter environmental footprint than concrete and steel. The solar pergola captures the sun’s energy, supplying part of the building’s consumption needs. Throughout the site, permeable paving is used to reduce stormwater runoff and the heat island effect. The building is designed to achieve LEED certification.

The customer experience upon entering to ordering and enjoying a meal is enhanced by sustainable design features all around, including an outside roof garden planted with ferns and white birch trees that is experienced inside a floating glass terrarium inside and above the dining room. This vantage provides guests an experience of viewing and feeling the landscape above and outside the restaurant.

Inside, tapestries of living plants improve indoor air quality and provide a backdrop of green. This 792-square-foot living tapestry is a functional visual amenity, improving indoor air quality, dampening noise, and increasing psychological comfort for employees and customers.

Resource-Efficient

McDonald’s aims to have the most resource-efficient restaurants possible, using the minimum amounts of energy and water and maximizing the use of renewable energy and resource-efficient features.

A generous solar pergola made up of 1,062 panels generates approximately 60% of the building’s electrical energy used in a year. This canopy visually unites the restaurant into a single volume, and beneath this “big roof” indoor dining areas, contained in a pure glass box, are seamlessly connected to outdoor spaces. The new kitchen reuses the footprint and structure of the previous store and comprises a second concrete clad box.

The carbon saved by using a CLT and Glulam structure instead of a non-wood structure is equal to removing more than 34,000 passenger vehicles from the road for one year.

While one-of-a-kind, the McDonald’s Chicago Flagship is generating valuable lessons that can be scaled, impacting communities around the world.

Walt Disney World Resort

When McDonald’s approached us again to help them design their new flagship at Florida’s Walt Disney World Resort, the challenge was to take an all-out sustainable approach and design a net zero energy building certified by the International Living Future Institute. The Disney Flagship aims to become the first net zero energy, quick-service restaurant and represents McDonald’s commitment to building a better future through “scale for good.” Incorporating visible and impactful symbols of change, the restaurant arranges architecture and technology to firmly place itself in the future. Like the Chicago project, we began with an assessment of the existing building and ended up reusing and incorporated as much as we could from the existing building.

Saving Energy

Quick-serve restaurants tend to be energy hogs—we needed to generate at least as much energy on-site from renewable sources as the building uses—so the team had to cut consumption significantly, which very much influenced the design. We designed the building to consume 35% less than baseline, or 666,454 kWh/year. We did this by optimizing kitchen equipment, which carries the biggest loads.

We designed a canopy with 18,700 square feet of standard photovoltaic solar panels and 5,000 square feet of BIPVs over an outdoor eating porch. The restaurant is a sustainable and healthy response to the Florida climate.

Taking advantage of the humid subtropical climate, the building is naturally ventilated for about 65% of the time. Jalousie windows operated by outdoor humidity and temperature sensors close automatically when air conditioning is required. An outdoor “porch” features wood louvered walls and fans to create an extension of the indoor dining room.

Green Design Strategies

Additional sustainable strategies include paving materials that reduce the urban heat island effect, previous surfaces that redirect rainwater, 1,766 square feet of living green wall that increases biodiversity, new LED lighting, and low-flow plumbing fixtures.

A robust education strategy was also a goal of the project. The architecture itself becomes a narrative tool in addition to interior graphics, interactive video content, and gaming that is unique to this location. The restaurant teaches visitors of all ages to be more dedicated environmental stewards.

With design, you are constantly asking for clients’ trust as you lead them into unfamiliar territory. That’s not always comfortable, especially if you’re in the role of safeguarding a global brand like McDonald’s. They have been our partner in design of these two new forward-looking, sustainable flagship restaurants that we think are champions of environmental stewardship. g DESIGN DETAIL

The new McDonald’s at Walt Disney World Resort in Florida was designed as a net zero energy building certified by the International Living Future Institute. Inside you’ll find 27-foot ceilings and sustainable building materials.

THE WALT DISNEY FLAGSHIP LOCATION HAS NEARLY 6,000 SQUARE FEET OF EXTERIOR PATIO.

Meet the Architect

Carol Ross Barney is the founder and design principal of Ross Barney Architects. She founded Ross Barney Architects in 1981 and has made significant contributions to the built environment, the profession, and architectural education. As an architect, urbanist, mentor, and educator, she has relentlessly advocated that excellent design is a right, not a privilege. Chicago is Ross Barney Architects’ home base.

Katelyn Chapin on Community and Equity in Architecture

This AIA Young Architect Award-winner is bringing inclusivity to the industry.

BY SOPHIA CONFORTI

A

At a recent visit to her parents’ home,

Katelyn Chapin unearthed a childhood travel journal from her early family getaways. Sprawled across its pages were not aimless doodles drawn in far-off places but floor plan sketches of the hotels they visited. “Growing up I don’t think I knew what the word architect meant,” Chapin says. “I can’t even recall seeing a floor plan. It was just how I expressed my ideas—through drawing.”

Chapin has always been a spatial thinker, going back to the first house footprints she ever made, drafted with LEGOs and wooden blocks. (They always included a driveway for her Barbies’ Corvette but were never quite built to the right scale.) Now an Associate at Svigals + Partners, Chapin is a 2021 recipient

KATELYN CHAPIN STARTED HER CAREER DURING THE LAST RECESSION AND NOW DEVOTES HER TIME TO HELPING YOUNG ARCHITECTS NAVIGATE A SIMILAR JOB MARKET TODAY. of the American Institute of Architects’ (AIA) Young Architects Award. It’s a testament to her design work, yes, but also her dedication to bettering the industry as a whole.

HOW SHE GOT HERE

When Chapin graduated from Roger Williams University in 2009, the US was in the midst of a recession. Landing a job in architecture was difficult, so she started work as a package engineering drafter before later joining Svigals + Partners, where she’s worked for the past 10 years. Moving from Massachusetts to Connecticut for the job, Chapin didn’t know anyone in the area—so she got involved.

“I didn’t have any contacts in Connecticut; I was moving here blindly,” she says. “I was looking for a network to be involved with like-minded people. I was active in the [AIA’s] Emerging Professional Committee early on in my career and eventually that moved into other roles.”

In 2018 Chapin became the Young Architect Regional Director for New England and last year was selected as the Young Architects Forum Community Director, on top of her roles serving in two other national committees—the AIA’s Equity and the Future of Architecture Committee and Association of General Contractors Joint Committee.

“I have my foot in a little bit of everywhere,” she says. “I’m finding that my drive is really community-based and ensuring that there is equity and inclusion in our profession, and, especially with the recent recession, ensuring that we retain females in our industry.” Much of Chapin’s advocacy work centers on giving a voice to architects and improving visibility, “making sure young architects see other architects that look like them” while also providing resources to advance their careers.

PROJECT PROCESS

These roles are an added bonus to Chapin’s architecture work itself, which focuses on higher education and K-12 spaces. The Bergami Center for Science, Technology, and Innovation on the University of New Haven campus is a career highlight and a 2019 LEED Gold project. Chapin recalls that the university needed a new academic building, but it wasn’t sure, exactly, what kind of building it really needed.

“We had a stakeholder group composed of the deans of each of the schools, professors, administration, the design team—a little bit of everyone from campus. We brainstormed what types of spaces would be required for their campus,” Chapin says. “Being a community-oriented person, this was my favorite part of the process.”

Those initial conversations were more of a space for faculty to air out their grievances about lack of storage. “Then we did a tour of campus, and what professors realized was, ‘Oh man, I was complaining about my storage, but this other department doesn’t have any storage, and I do.’ And so they started to sympathize with each other, and that helped define what the space was going to be.”

The result was a sustainable, interdisciplinary hub for students on campus. “It wasn’t meant to be just a spot where students went for class and then left,” Chapin says. “It was going to be an environment where students would come, go to class, grab a coffee, sit in the atrium space, hop to another class, go use the makerspace—it was really intended for a half-day or full-day experience as a student.”

GREEN BUILDING

The site itself was an old parking lot, which was removed and replaced with plentiful green space to reduce the heat island effect and improve

stormwater runoff. Bioswales were also added along the main road in front of the building to filter the water.

From an architectural standpoint, one of the building’s most noticeable elements is its golden exterior sunshades, meant to reduce solar heat gain. Indoors the team ensured there was copious daylight and views to the outside. “We prioritized products that were in a 500-mile radius and used low-emitting adhesives, sealants, paints, coatings, and flooring. In the end about 22% of our building materials were manufactured using recycled materials,” Chapin says.

The project also incorporates high-efficiency boilers and chillers, on-demand controlled ventilation, and low-flow fixtures that reduce water consumption by 40%. By the end of construction more than 93% of construction waste was recycled or went to a salvage center.

“Because it’s an innovation center, we wanted to pay attention to how sustainability was expressed and also use building as a learning tool,” Chapin says. In the lower levels of the building, which include much of the building’s makerspaces, Chapin and the design team left parts of the structure exposed so students could see how the steel and the other materials formed the building.

Although students may not be able to see every single sustainable strategy up close, the university is doing its part to educate the community through green campus tours. It’s a tool not unlike those in Chapin’s own work, where education is key in uplifting and pushing the industry forward. She recently started a book club within the Svigals + Partners office to further dig into architectural topics that may not come up in the firm’s day-to-day work but are important to the future of the architecture. “I feel like there has been a little bit of a pivot in the industry where 10 years ago we were talking about sustainable design strategies and how to implement them, but now that’s really just good design,” Chapin says. “Sustainability strategies and different types of materials—they are always evolving. There is always an opportunity to share the knowledge you have.” g

Project: Bergami Center for Science, Technology, and Innovation Location: West Haven, CT Completion: August 2020 Size: 45,500 square feet Cost: $35 million Architect: Svigals + Partners Structural Engineer: Michael Horton Associates MEP Engineer: BVH Integrated Services Civil Engineer: Westcott & Mapes Construction Manager: Consigli Construction Co. Landscape Architect: Richter & Cegan Interior Designer: Svigals + Partners Energy Analysis: Karpman Consulting

THE LEED GOLD BERGAMI CENTER WAS DESIGNED WITH COMMUNITY IN MIND, AS THE DESIGN TEAM SPOKE WITH STAKEHOLDERS ACROSS THE CAMPUS TO DEFINE THE FINAL PROJECT.

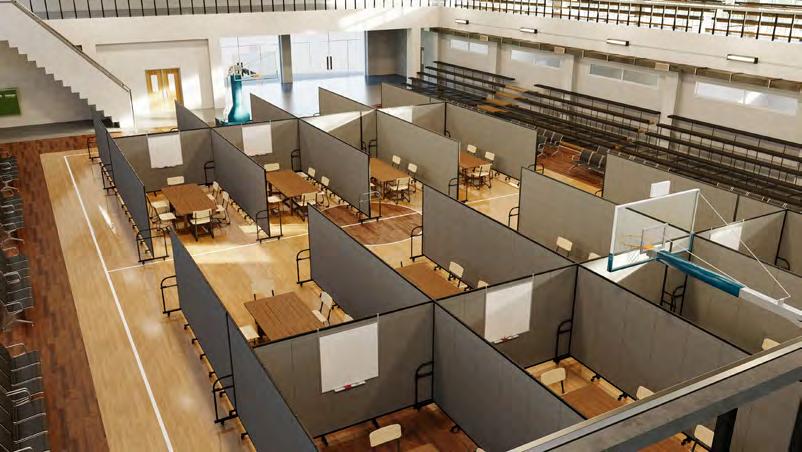

EASILY DIVIDE EDUCATIONAL SPACES AND DISPLAY SCHOOL PROJECTS WITH SCREENFLEX.

How do portable dividers make educators’ lives easier?

For more than 30 years, Screenflex has been leading the industry with innovative portable room dividers. Easily divide and manage any space with these flexible solutions that are lightweight, sturdy, easy to store, and even help you get work done with seemingly endless options like tackable panels and (even) dry erase panels. We recently sat down with Screenflex Vice President Rich Maas to find out more about the scope of options and how these dividers lend themselves to flexible learning environments.

SCREENFLEX PORTABLE DIVIDERS ARE QUICK AND EASY TO SET UP IN ANY DESIRED CONFIGURATION.

Administrators, teachers, and

students alike benefit from our accordion-style portable room dividers. You can easily divide a space into multiple rooms or make a mix of temporary walls with our dividers. Partitions form an “L,” “U,” cross, or curve shapes around desks, and you can connect two or more dividers to make complex configurations or long continuous lengths. Choose between vinyl or fabric-covered portable classroom dividers to match your room’s décor and even add a logo.

Listening to our customers’ needs is a big part of what we do. Take, for example, what we learned from our work with schools that happen to be in floodplains. While no floor is 100% level, those floors were the worst. Those experiences pushed us to develop our self-leveling casters and position control hinges to ensure our dividers stood straight even in unusual conditions. Our molded position control hinges help the divider remain in the desired configuration, and our full-length hinges continuously connect each panel to adjacent panels for added stability. As a result we offer the only patented stabilized portable room divider.

Our solutions won’t scratch up the floor, either. You can easily roll our products into a gymnasium, for example, breaking that large space into many spaces. Lock the dividers in place and rest easy, as the self-leveling casters are hard rubber, non-marking casters. The spring mechanism we invented helps our dividers stay stable on even the most uneven floors.

Educators love our dividers for their honeycomb core, which knocks down sound and gives our dividers a tackable surface to display school projects and artwork. Many also turn to us for space planning. If you’re a principal needing to configure extra rooms in a cafeteria or library for after-school programs, just give us your dimensions and we’ll sketch up a plan. Our products and services make managing facilities easier than ever. g

Steam heat is not a new thing, but providing effective and efficient control is. Heating with steam radiators has been around for more than a century. Despite its old school function and design, it isn’t going away any time soon. That’s why engineers at HVAC design and manufacturer Salus have developed tools to help owners and end users have more control over their steam-heated environments. Christopher S. Robertson, director of sales for Salus North America, has traveled the world, getting up close and personal with heating control strategies. In this column, he tells us how to tame wild steam so we no longer need to open the window to control comfort.

How do I tame wild steam in my building?

BY CHRISTOPHER S. ROBERTSON DIRECTOR SALUS NORTH AMERICA

Anyone who’s ever been in a steam-heated

building knows it can provide a great quality of heat but be challenging to control the temperature. The steam boiler, usually in a basement, pumps out steam at approximately 212 degrees. Steam travels through the building, sending temperatures in some spaces soaring while others stay low. For more than a century the only solution has been to open a window.

Steam heating systems were developed in the late 1800s. During the 1918 Spanish Flu opening the window to circulate air helped reduce illness transmission, similar to what we’ve done today. The goal was to have a heat source extreme enough to keep spaces warm even on the coldest days with the windows open. Nowadays, despite being in a pandemic, opening windows with the heat on is seen as wasteful— like throwing your dollars out.

Steam boilers may not be the most efficient way to heat a space, but they’re not going anywhere soon. They’re common in buildings built before 1950. The Greener, Greater Buildings Plan reports most buildings above 50,000 square feet (81.9% in New York City alone) use steambased heat. The cost to replace them would be astronomical. You’re better off demolishing the building and starting fresh. In recent years there have been a few solutions to help control radiator heat. Covers were invented to guide heat from one space to another. Yet few of these inventions meet today’s technology standards.

That’s why at Salus we’ve developed the technology to control steam heating systems, ultimately taming wild steam. Using thermostatic radiator valves and remote thermostats, our technology increases comfort and maximizes savings. Our wireless technology enables individual thermostat controls to be in each space. Occupants no longer need to worry about one space being 80 degrees and the other 60. It’s helping bring this older technology in line with modern times. g

SALUS’ TECHNOLOGY CAN INCREASE COMFORT WHILE MAXIMIZING EFFICIENCY. READ MORE IN THE NEXT ISSUE OF GB&D.

Now on the cusp of its 50th anniversary, Maxxon®, the creator of Gyp-Crete® and the gypsum underlayment industry, has continued to be North America’s premiere manufacturer of gypsum underlayments, sound control systems, and moisture mitigation solutions. Backed by robust research and development and manufactured using top-quality raw materials, the innovative and ever-expanding line of subfloor prep products can be found in commercial and multifamily structures nationwide. When it comes to underlayments, however, the solution depends on the project. Erik Holmgreen, Maxxon’s vice president of research and development, explains how it all works.

How do I choose underlayment?

BY ERIK HOLMGREEN, VICE PRESIDENT OF RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT

Our product line includes sever-

al solutions for different types of subfloors and construction. It’s never one size fits all. The eco-friendly Gyp-Crete® line is perfect for use over wood subfloors and is the industry standard in multifamily construction. Gyp-Crete products are available in several formulas to meet the cost and floor strength requirements of any job. While often used in wood frame construction, our high strength underlayments are also excellent for smoothing concrete slabs or precast planks in new and renovation projects. Our Gyp-Crete products are typically poured at one inch deep over our Acousti-Mat® line of sound control products. This system provides excellent sound control as well as fire resistance. Maxxon’s Gyp-Crete and Acousti-Mat system is listed in 140 UL fire rated designs and backed by hundreds of published sound tests. These solutions are the core of what Maxxon has done for decades, and we always continue to improve their performance and cost.

Beyond our GypCrete line we are particularly excited about our highstrength self-levelers. These commercially targeted products, like Level EZ™, have very high flow, high strength, and can be installed quite thin with little floor preparation. Rather than the one inch of gypsum underlayment in the multifamily space, we can install these products down to a quarter-inch or less to smooth out rough subfloors and create a level surface for floor coverings. These thin pours and very level surfaces can be ready for floor coverings in very little time.

These features are also useful in multifamily renovations, where old rough floors need repair and leveling with short turn around. The Maxxon® EZ Renovation System™ uses these levelers in conjunction with repair products such as Gyp-Fix EZ® patch and Maxxon Fortify™, a strengthening primer specifically developed for multifamily renovations.

And you can rest assured every product comes with Maxxon’s quality guarantee. With our constant innovation building on a half-century of success, some things never change. g

LEVEL EZ HAS VERY HIGH FLOW, HIGH STRENGTH, AND CAN BE INSTALLED QUITE THIN WITH LITTLE FLOOR PREPARATION. READ MORE WHEN MAXXON TACKLES SOUND IN THE NEXT ISSUE OF GB&D.

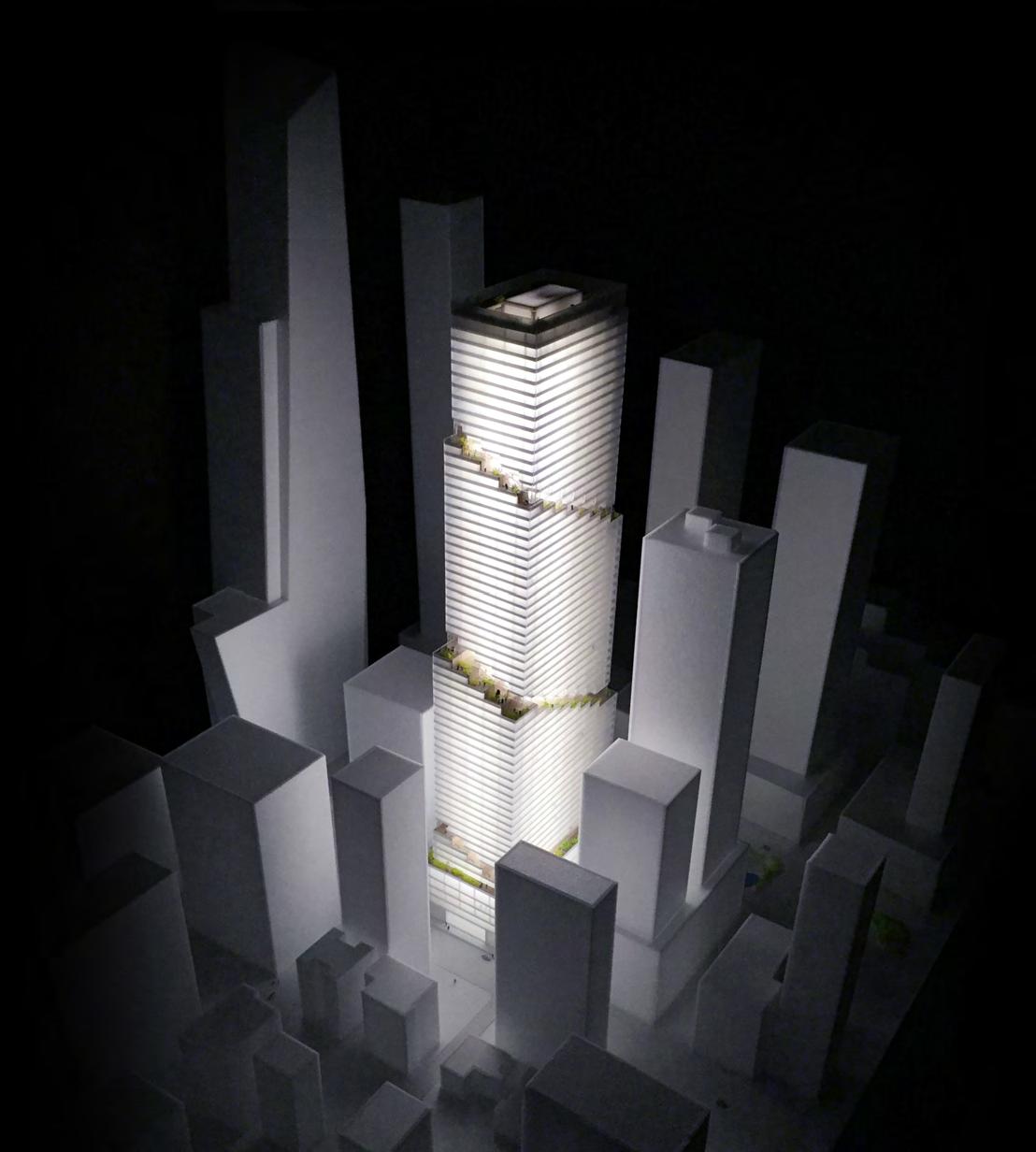

Skyscraper with a Twist

With impressive views and access to open-air terraces, the Spiral is a new skyscraper designed by Danish powerhouse Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) that is set to change the Manhattan skyline. Positioned at the end of New York City’s beloved High Line, the design features a dramatic series of cascading terraces that reaches every tower floor—bringing light, fresh air, and access to outdoor space to building occupants. Towering at a height of 1,005 feet, the Spiral includes a continuous green pathway that connects to offices on every level. Terraces open up to double-height atriums, providing even more opportunity for people to connect. The chain of amenity spaces and terraces originates at the Spiral’s main entrance on 34th street and Hudson Boulevard. The spiral wraps around the tower, which becomes gradually slimmer toward the top. The open-floor concept and sustainable design aims to change the way we think about interacting with our neighbors, all driving toward the goal of more people-centric design with flexible workspace in architecture.. —Sierra Joslin

FIND THE INFORMATION YOU NEED FOR LEED

L ook f o r t he leaf icon to fi nd more information on green p r o ducts

ARCAT provides thousands of reports from building product manufacturers on how their products can help you make the right choice.

With ARCATgreenTM reports, you can find out how much post consumer waste is used in creating products, to low- emitting materials and other LEED contributing credits. You can find this information and more with ARCATgreen reports.