7 minute read

Seeing green on green: A new way to look at weed control

By Guillaume Jourdain, Bilberry

Advertisement

AT A GLANCE…

Green on green camera technology is now used on farms. This will lead to important financial and farm management benefits for growers. Growers need to not only understand the benefits – but also the limitations – of new technologies such as green on green weed detection.

Two optical camera systems to spray weeds have been on the market for several years – WEEDit and WeedSeeker. These systems are now commonly used in Australia for green on brown applications. A number of start-up companies (such as Bilberry), large corporations and universities are now developing systems with green on green capability – that is, being able to identify a weed in a growing crop and selectively spray the weed.

The technology used by the various companies in this green on green space is similar: Artificial intelligence with cameras – sometimes RGB/colour cameras and sometimes hyperspectral cameras.

Using artificial intelligence (AI) to detect weeds

Finding machine-based methods to recognise weeds within crops has interested high-tech companies and researchers for a very long time. The first patents on this topic date back to the 1990s.

The main approach was to differentiate weeds from crops thanks to their colour and shape. Through mathematical formulas, a range of colours and a range of shapes for each weed can be identified. In other words ‘conventional’ algorithms – which set out a process, or the rules to be followed by the machine – to identify the weed, can be created.

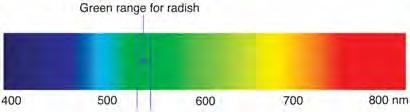

Figure 1 shows a very simplified example. Conventional algorithms can identify radish in the laboratory because the weed colour sits within a specific green range.

This is all very well in the laboratory under controlled conditions with constant light, no wind, all crops and weeds are from the same variety and are not stressed etc. But paddock conditions are completely different.

The sun can be high or low, in your back or in your eyes, there can be clouds, there can be shadows from the tractor/sprayer cabin or from the spraying boom, crops can be damp in the morning which creates sun reflections, the soils always have different colours and so on.

FIGURE 1: A simplified example using conventional algorithms to identify radish in the laboratory

GREEN ON GREEN TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPERS

Bilberry – a French AI based start-up that specialises in cameras for recognising weeds (subject of this article). Blue River Technology – acquired by John Deere in September 2017 for more than US$300m, developing a See and Spray technology. This involves a spraying tool with smart cameras, trailed by a tractor, that can spray weeds very accurately at about 10 km per hour. Ecorobotix – a Swiss based start-up developing an autonomous solar robot that kills weeds. Ecorobotix is also developing the camera technology. AgroIntelli – a Danish company developing an autonomous robot to replace tractors, that will also include camera technology spraying capacity. Bosch – a German company becoming more involved in agriculture and has a project called Bonirob, a weed-killing robot with smart cameras.

It’s clear that conventional algorithms cannot work in field conditions. Enter artificial intelligence as a game changer.

Artificial intelligence – and especially deep learning – is another way of working on images to recognise different objects. It is now the most widely used technology for computer vision when it comes to complex images such as recognising weeds within crops or on bare soil.

Deep learning is part of the ‘family’ of machine learning and is inspired by the way the human brain works. Deep learning often uses the architecture of deep neural networks.

The learning part can be either supervised or unsupervised.

Research on deep learning started in the 1990s. In the past few years deep learning applications have become much more widely used. And there are three main reasons for this. The recent advent of: • Plenty of data; • High computing power; and, • Powerful algorithms.

W ith these three ‘advances’ deep learning is now applicable in many situations and is especially relevant in agricultural applications.

Two of the most important steps with AI and deep learning in agricultural applications are data gathering and paddock testing. And these two steps largely happen in the field.

What is especially complex and important about data gathering is to be able to capture the diversity of in-field situations.

Research and results at Bilberry

Bilberry was founded in January 2016 by three French engineers with the idea to use artificial intelligence to help solve problems in agriculture. The main product from Bilberry is now embedded cameras on sprayers. These cameras scan the paddocks to recognise the weeds and then control the spraying in real time to spray only on the weeds and not the whole paddock.

Bilberry also develops cameras that recognise weeds along railway tracks. The technology is similar, with just a higher speed (60 km per hour) as well as day and night applications.

The biggest focus for us developing this product is now on Australia, with several sprayers already equipped with Bilberry cameras. One of the reasons for this focus is the huge interest among Australian growers and agronomists towards green on green spot

spraying.

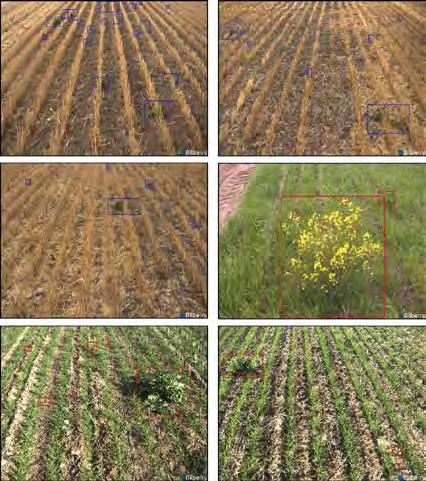

Weed detection on bare soil (three first pictures) and wild radish detection in wheat (three last pictures) – Images taken from Bilberry cameras – results in real time SECTION 10 SPRAY APPLICATION This section brought to you in association with

One camera every three metres is mounted on the spray boom along with computing modules (to process the data) and switches (to distribute power and data to each camera).

In the cabin, there is one screen to control the system.

Results to date

Three algorithms are now validated and can be used by growers in the field – two of these are particularly focused on Australian growers: • Weeds on bare soil detection (using AI, but same application as WEEDit or WeedSeeker); • Rumex (dock weed) in grasslands; and, • W ild radish in wheat (especially when weeds are flowering).

It is important to note that large chemical savings are made with the cameras, but it is also a very interesting tool to fight resistant weeds, potentially enabling the use of products that cannot be currently used in-crop due to either cost or crop impact.

The photographs taken by the Bilberry

Main features of the Bilberry camera

The cameras are used at up to 25 km per hour speed and can be used on wide booms – currently the widest boom used is 49 metres, but could be more if needed. This creates very high capacity. Theoretically the camera capacity can be calculated as: 25 km per hour x 48 metres = 120 ha/hour

In real spraying conditions, capacity is of course lower, as the speed is not always 25 km per hour and the sprayers need to be refilled.

Summer spraying in Australia (NSW example)

One Agrifac 48 metre boom is equipped with cameras on a farm in New South Wales. Before the cameras were used by the grower and his team, a comparative test was made with current camera sprayer technology. It was then decided to use Bilberry cameras as much as possible on the farm.

The cameras have been used since the beginning of the 2018-2019 summer spraying season. Table 1 below outlines the main ‘numbers’ over a three week spraying period.

TABLE 1: Figures from the 2018-2019 summer spraying season Total area Ha/day Ha/hour Chemical sprayed savings 6199 ha 413 ha 75 ha 93.5% The carrier volume used was generally set at 150 litres/ha.

It is very important to note that the chemical savings are directly linked to the extent of weed infestation in the paddocks. A paddock with high weed infestation will get little savings whereas a paddock with low weed infestation will get high savings.

Spraying dock weeds in grasslands (Netherlands)

In the Netherlands, a 36 metre Agrifac boom is equipped with Bilberry cameras and uses an algorithm to spray dock weeds on grasslands. A rigorous testing process earlier was used to ensure the algorithm was working properly.

Once the grower validated that the algorithm was working, it was used during the whole spraying season. About 500 hectares were sprayed during the season, and the average chemical savings were above 90 per cent. The cost of the chemical is about Є50 ($80) per hectare for this application which means Є45 ($72) per hectare in chemical savings with the use of cameras.