Fall Edition The Only Environmentalist Publication at the University of Illinois Fall Edition The Only Environmentalist Publication at the University of Illinois The Green Observer The Green Observer October 27, 2022 1

Table of Contents Considerations and Editors Note..........................3-4 Fall Animals Around Campus (Spainhour)..............5-6 Photography.........................................................7-8 Amazon Chernobyl (Gergeni)...............................9-10 Fall Crafts (Sweeney and Sampson)……………..11-12 Lifetime of Learning (Sampson)………………......13-14 Harvest Season (Beem)……………………………..15-16 Land Acknowledgement………………………..…17 Quote……..…………………………………………18 References………………………………………….19 2

Made Possible By: Students for Environmental Concerns

Students for Environmental Concerns is the oldest and largest environmental organization at the University of Illinois, dedicated to environmental activism and justice. This year, the Green Observer has joined SECS in their mission to maintain the stability, integrity, and beauty of the natural world, promote and participate in the sustainable food revolution, and pursue clean energy on and off campus.

SECS holds weekly meetings in the Channing Murray building ( 1209 W Oregon St) at 6:30pm every Wednesday

Photo by Eugenia Porechenskaya

3

Editor’s Note

Dear Green Observers,

I am delighted to present our first edition of the 2022-2023 school year. As we navigate through our partnership with Students for Environmental Concerns, we are pleased to welcome our new and returning members.

This issue focuses on the importance of local and global environmental concerns, autumnal fauna and foliage, and ways to incorporate sustainability into your lifestyle this fall. We certainly had fun composing this edition so we hope you enjoy reading it!

Sincerely, Maggie Sampson

4

Fall Animals around Campus

By Julia Spainhour Virginia Opossums

If you’re wandering about campus late at night, you may come face-to-face with a Virginia Opossum.

Though they’re not able to run, you’ll see them quickly walking away with their tail moving circularly for balance. Possums are the only marsupials living in North America, meaning they carry their young in a fur-lined pouch, similar to kangaroos. When they are afraid, they are known to show their teeth and hiss with their mouths open to appear more threatening. In other cases, they will ‘play dead’, and go into an involuntary catatonic state for up to several hours at a time. They lie down on their side, hang out their tongue, open their eyes, foam at the mouth, and release a bad odor.

As opportunists, possums will eat anything that comes their way—and this includes a lot of pests that bring diseases to humans, like rats and ticks. And while it’s probably a good idea to keep a safe distance, possums typically have a high resistance to rabies. If you see them, they’re probably just passing through!

Fun fact: Male possums are called jacks, and female possums are called jills

The Northern Cardinal

If you see a Northern Cardinal this fall, you won’t be able to miss it. Their distinctive red feathers, black mask, and crest make them one of the most identifiable birds in North America.

Fun fact: The Northern Cardinal is the state bird of Illinois.

The vibrant red feathers are only possessed by the male cardinals. They get the coloration from carotenoid pigments in red fruits they eat, and it’s used as a way to attract the olive-colored female mates. They court them by placing seeds into their mouths one at a time, and then the male brings materials to the female to make the nest and care for the young.

Many cardinal pairings are monogamous and stay together for life, traveling together and singing to communicate. Furthermore, male cardinals are very territorial, and have been known to fight their own reflection for hours at a time, thinking it is another cardinal trying to invade.

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC

5

Painted Lady Butterfly

Fun fact: While they are a chrysalis, their body turns to liquid in order to become the butterfly.

September and October are great times to see painted lady butterflies before they head down south to Mexico for the winter.

Their wings are able to carry them to speeds of up to 30 miles per hour, allowing them to reach their destination much quicker than other migrating butterflies. In fact, they’re the most widespread butterfly in the world, so they can be found on the continents of North America, South America, Africa, Asia, and Europe. As caterpillars, they build shelter for their chrysalis with silk, and hang upside down on a leaf while they wait for a week to become beautiful butterflies. They are relatively short-lived, however, and have a lifespan of 15-29 days. Pay close attention, and you may see them fluttering around campus.

Garter Snakes

Make sure to look where you’re walking, because you might stumble upon a plains garter snake. These snakes have a slender, dark gray body, with 3 yellow stripes running along it. They typically eat small prey, such as earthworms, toads, fishes, salamanders, small mammals, birds, and pretty much anything they are able to. They flick their tongues to sense prey in the area, then quickly ambush and subdue them, in order to eat them whole. If you see one, don’t be scared! Though they do use venom to subdue their prey, it carries no (or very little, in rare cases) effect on humans. If they do feel threatened, they will likely release a stench similar to that of a skunk, so approach with caution.

Fun fact: Scales on their underside allow them to swim.

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY 6

By Maggie Sampson

Photography 1. Research Park Champaign, IL 2. Research Park, Champaign, IL 3. Research Park, Champaign, IL 4. Martha’s Vineyard 5. Dallas, TX

7

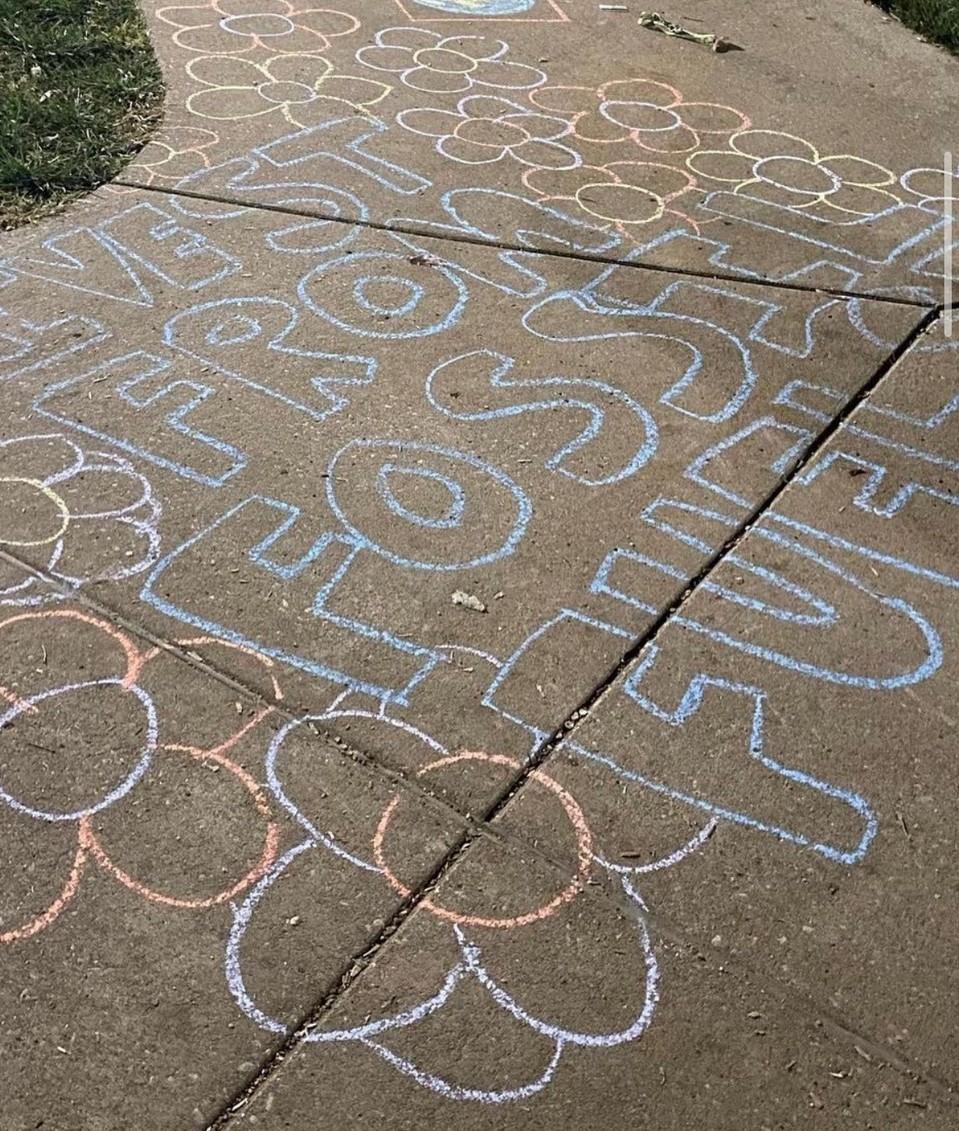

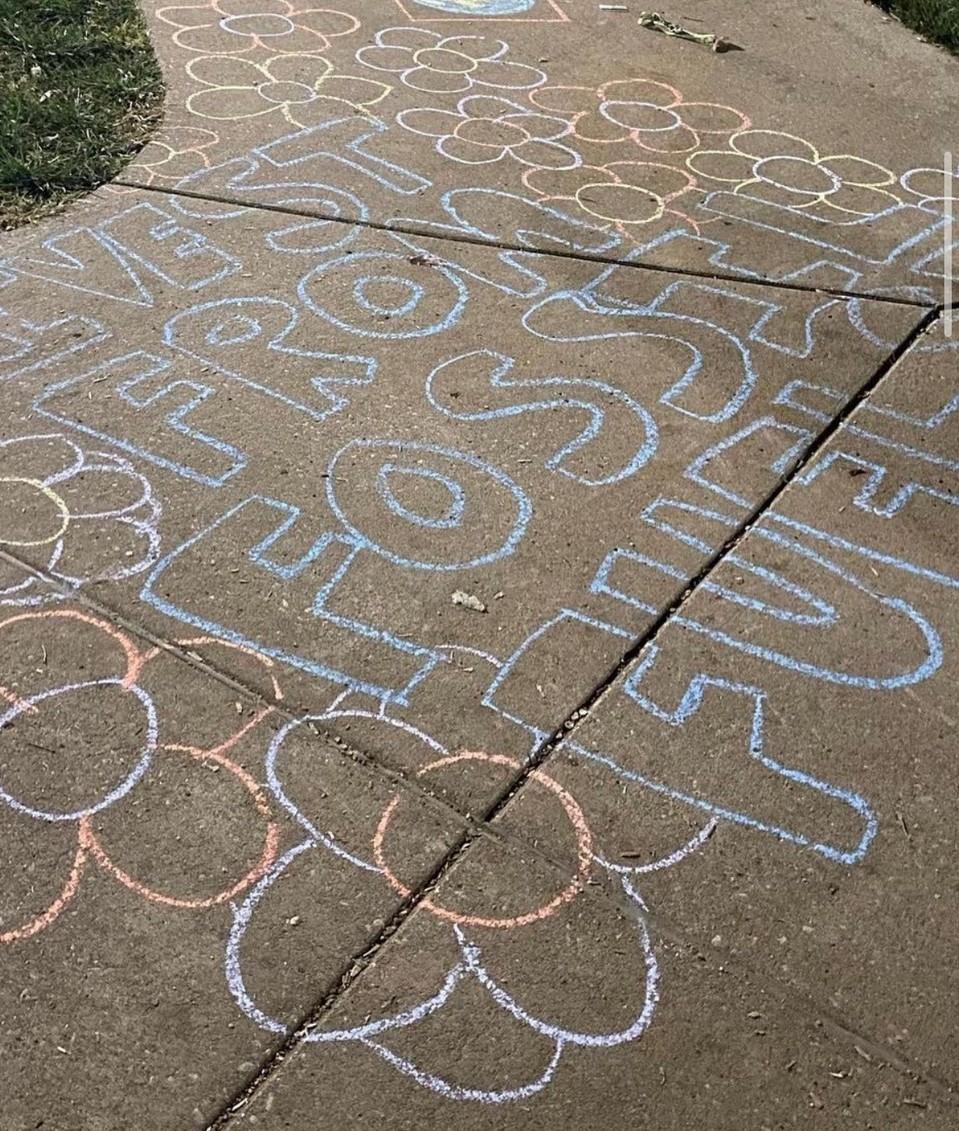

Photography @SECSUIUC 1. Climate Strike Prep 2. Quad Chalk 3. Climate Strike 4. Quad Chalk 8

A Look Into the “Amazon Chernobyl”

by: Michael Gergeni

Near Sucumbíos, in northern Ecuador, there is a region named Lago Agrio, containing an oil field. Within immediate proximity of the field, there are tens of thousands of indigenous Ecuadorians, many of whom lived there for hundreds of years, who depend on nearby rivers and water sources for their livelihood. In the 1960s, a company called Texaco, which we now know as Chevron, began drilling in the area.

Over a period of 20 years, they extracted 1.7 billion barrels of oil from the field and netted over 25 billion dollars (Feige, 2008). This was a large success for Texaco, but it had extreme environmental consequences for the surrounding populations. What Texaco neglected or, at the minimum grossly misunderstood, was that their oil drilling practices resulted in a massive spillage – 16.8 million barrels – of crude oil into the nearby water sources that the populations around it relied upon. In addition to the involuntary, Texaco would use crude oil – estimated to be around 650 thousand barrels – to clean the roads they built. The result of that were rivers flowing black with oil, water made viscous by oil; snakes, birds, fish, and many other animals writhing on the banks to attempt to wash the coating of oil off themselves.

The human cost was even worse –thousands of people were dispossessed, malnourished, many of them developing alcoholism (Kimerling, 1991). Two different groups of indigenous peoples were declared extinct, at least in part from Texaco’s oil disaster– the Teteté people some time after 1973, and the Tagaeri people in 2003 (Kimerling, 2006).

Environmental Catastrophe, Extinction of Two Native Cultures, A Decades-Long Coverup, and a Human Rights Lawyer Imprisoned for Almost 1,000 Days:

9 This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA

Steven Donziger is a human rights lawyer. In 1993, he visited Lago Agrio after hearing about pollution in the area. He expected a lot of pollution, but the actual amount shocked him. He reported “[seeing] things that were unbelievably horrid” in an interview with Vice. Quickly after his visit, he joined with a team of lawyers in a 30,000 person class action lawsuit against Texaco in New York courts. This first attempt was thrown out because, as Texaco argued, it was filed in an improper location. So, the lawsuit was filed again in Ecuador in 2003. The very first day of the trial, they immediately began challenging the jurisdiction again.

By this time, Texaco had been acquired by Chevron, but their efforts to suffocate these attempts at justice were continuing. As the trial began back in Ecuador, Chevron once again attempted to avoid culpability by claiming that the courts had no jurisdiction there either. The trial after that saw numerous unethical litigation tactics by Chevron – all of which would not fit within this article.

These attempts became even wilder after the Ecuadorian court awarded the indigenous populations the equivalent of $11.4 billion dollars in damages. Chevron filed separate actions, both with international courts and in US courts and eventually found judges that would reject the original Ecuadorian ruling. Then came the attacks on Donziger. In 2019, he was placed under house arrest because of the US ruling, because it placed charges on him of criminal contempt of court. He was sentenced to 6 months in jail in October 2021 (Malo, 2021). He spent a total of 993 days under house arrest and 45 days in jail.

Steven Donziger was released on April 25th , 2022, though his conviction was still confirmed in June. We are now left to question why this case flew under the radar. We have a great necessity to raise awareness about this series of catastrophes. It is not too late for us to raise our voices and rally for justice against the historical and continued environmental and cultural destruction taking place within the global South. Although this case has been settled, and Chevron has been successful in winning the legal battle, we can still fight against it. Today, this issue has not had much public perception. Tomorrow, who knows? Only those who take action can decide.

Photo by Sina

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY

10

Reduce, Reuse, and Spook!

By Audrey Sweeney and Maggie Sampson

Reduce, Reuse, and Spook!

It's time to transform your home into a festive Halloween town with easy, low budget, DIYs that will impress all the trick-or-treaters and make your environmentalist heart happy. Every wreath, pumpkin, and cute decor can already be found in your recycling bin. There is no need to waste money on convenience store spider webs when you can make your own reusable spiderwebs out of your trash! So, save that extra cash to buy the jumbosized candy bars and make these sustainable DIY fall crafts:

Egg Carton Wreath:

Materials: 1-2 empty egg cartons, paint, glue, miscellaneous cardboard

Steps:

1. Cut your cardboard into a circular wreath shape

Cut each individual egg holder from the carton and cut even slits on the sides (for flower petals)

Paint each “flower”

Arrange and glue “flowers” on carboard wreath

Sweater Pumpkin:

Materials: 1 sweater sleeve, newspaper ball (or really anything you can shape into a pumpkin), Hot glue, green ribbon

Steps:

1. Open the sleeve by making a cut down the length of the sleeve

Wrap the opened sleeve around the newspaper ball and shape into pumpkin

Close any gaps with hot glue

Apply embellishments with ribbon or anything else you’d like to use!

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

2.

3.

4.

2.

3.

4.

11

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under

CC

BY-NC-ND

Trash Bag Spider Webs Materials: 1 trash bag, Scissors, Tape/wall applicators Steps: 1. Decide on a spider web design 2. Cut open the trash bag so that it lies completely flat 3. Cut trash bag into a large square 4. Fold the trash bag in half 2-4 times over 5. Cut designs into the folded bag (think paper snowflakes) Fabric Ghost Statues Materials: Any sort of white fabric, scissors, tape, black marker, old newspaper/ anything that malleable Steps: 1. Cut white fabric into large squares 2. Form old newspaper into ghost body parts with tape and attach 3. Drape white fabric over newspaper mold 4. Draw eyes/add embellishments

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

12

A Lifetime of Learning

By Maggie Sampson

A young girl, about five or six, walks along a woodchipped path. Her mom is elsewhere, admiring the flowers—Queen Anne’s Lace is her favorite. It is the dead of summer and sun is beaming down directly onto child’s head. Feeling hot, she finds shelter under a large mulberry tree. She notices the way the fallen berries squish underneath her feet as she steps closer and closer to the trunk. Carefully, she looks around at all the branches. As she looks to her left, she notices something interesting —low-hanging branch hosting a small nest. So small that it is difficult to decipher the nest from the twigs and leaves connected to the tree. As she approaches the nest, she sees something even more fantastic. It contains four tiny eggs, each a baby blue and covered in little brown speckles. The only other eggs she had seen before had come from the grocery store. All of the sudden, as she peers over the edge of the nest, a small red streak swoops down from above, nearly hitting her in the face. Startled, the girl stumbles backward and trips over the root of a tree—staining her khaki shorts with mulberry juice. Frightened and wistful for a time when her shorts weren’t covered in red and purple spots, the little girl runs back to the patch of flowers to find her mother. Her mother holds her in her arms for a few moments and the little girl realizes something important—just like her mother will always protect her, the cardinal will always protect its babies.

She can still enjoy nature and witness the beauty of a vibrant red bird, so long as she does not interfere with its safety and the safety of its babies. While a seemingly obvious conclusion, certain natural relationships are learned concepts. These seemingly obvious ideas are learned from direct interaction with nature. Not only did the little girl’s experience teach her about maternal instinct, but it enforced existing ideas like gravity, coordination, and her responses to fear. According to “Childhood Development and Access to Nature: A New Direction for Environmental Inequality Research”, research indicates that learning in nature can deeply affect children’s cognitive abilities and development. Considering that wild animals learn their foundational concepts by observing the world around them, it makes sense that humans would not be exempt from these processes.

13

A few years after her experience with the cardinal nest, the little girl begins learning in a classroom setting. She learns all sorts of things like letters, numbers, shapes, and time—recognizing the importance of these fundamental concepts at a young age. One day, however, her teacher starts the day talking about birds. As the teacher drones on and on about nests, eggs, and feathers, she wonders why they are talking about something so small and insignificant (at least compared to the building blocks of the English language). As she begins to get bored, she looks out the window and notices a bright red bird perched on the branch of a nearby tree. Immediately, she recognizes it as an Illinois Cardinal. She watches the bird begin building a nest, finding small twigs and leaves, and slowly forming a home in the trees. She realizes that even the smallest and seemingly insignificant aspects of nature are worth observing. Much like her, the bird needs a home for itself and its family. She recognizes the reliance the cardinal has on its surroundings. It has experienced and learned from the environment to reap the full benefits. One day she will realize we share the same reliance on nature as the cardinal.

When the little girl eventually grows up and enters middle school, her classes become more detailed and difficult. There, she learns all sorts of new subjects like biology and math. She understands the obvious connection these subjects have to nature but, it is in her biology class that she learns about the healing power of plants. Before this point, she had always viewed medical treatments as some sort of magic, where the doctors were wizards and civilians were all mystified by the powers of modern medicine. However, after hearing about the origination of aspirin, she realizes the true importance of learning about our environment. Aspirin, she learns, is made from the salicylic acid found in willow bark. She had never grasped that something so widely used could be made from something as simple as tree bark. After that lesson, modern medicine lost its magic. It was merely a tangible effect of learning about the environment and manipulating natural resources to serve human needs.

We learn our most fundamental skills and concepts from observing the world around us. Therefore, everything we know about humanity is inherently tied to our environment. Humanity has been able to grow and be successful by passing on the knowledge we gain during our lives onto future generations. As we grow as a society, we must consciously educate ourselves on how to live with nature rather than in spite of it. In terms of the human approach to the natural world, we must understand that life on our planet relies on us too. We have evolved with Earth, not in spite of it. Through enforcing environmental education and teaching naturalist principles, we can better understand our existence as cohabitants on the vast planet of Earth and hopefully find solutions to human-made problems like climate change.

14

Harvest Season is Upon Us!

The Connection Between Agriculture, Biodiversity, and Cultural Depreciation

Sophia Beem

What is biodiversity? Biodiversity is the variety of life on Earth! Biodiversity and biodiversity loss can be measured by species richness, genetic diversity, and ecosystem diversity in a particular area.

What is biodiversity? Biodiversity is the variety of life on Earth! Biodiversity and biodiversity loss can be measured by species richness, genetic diversity, and ecosystem diversity in a particular area.

How Biodiversity Affects Agriculture

As we enjoy the season of corn mazes and pumpkin harvests, we should also pay attention to the way the environment plays a role in our farming.

Biodiversity has been fundamental to evolving farming systems thro ughout human history

. However, sustainable agriculture suffers as a result of biodiversity loss.

Biodiversity loss increases genetic uniformity, and this homogenizati on of species and farming systems causes vulnerability to pests and diseases that decrease productivity and nutrient value

. Concerns of genetic uniformity apply to other agricultural factors too, not just crops.

The loss of insect diversity ruins pollination processes, the loss of s oil diversity decreases fertility and productivity, and the loss of habit at diversity increases risk of contaminants and pests.

How Agriculture Affects Biodiversity

Agricultural practices, while harmed by biodiversity loss, also contribute to said loss.

Human inputs to agriculture such as pesticides and GMOs succeed in producing higher yields, but adversely pollute the air, water, and soil, which eradicates species

. Also, the rapid expansion of agriculture to previously wild areas eliminates ecosystems. This expansion contributes to greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel use, land clearing, metha ne emissions, and nitrous oxide emissions from fertilizer use.

Agriculture, biodiversity, and climate are all intricately connected. Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture generate climate change, which is detrimental to the environment as well as farming practices.

In addition, industrialized uniformity has overcome the agricultural landscape, eliminating diverse a gricultural systems such as traditional agroforestry and indigenous shifting cultivation systems. Th ese diverse systems were critical because they placed less pressure on the environment and supp orted water retention, nutrient cycling, and decomposition.

Photo by Connor Vaughan

15

Cultural Consequences

There are many consequences resulting from biodiversity loss via agriculture. Firstly, losing diverse farming systems in favor of monocultural models devalues local knowl edge and traditions concerning farming and plant resources

. Racial justice and environmental justice are connected, and the loss of traditional agricultural practice is one way that both racialized groups and biodiversity are harmed. While this relevant cultural intelligence depreciates, the global population continues to grow while food needs follow suit. Food insecurity has become a very prevalent issue.

Food demand increases the conversion of land to agriculture, instituting a vicious cycle: agri cultural expansion causes biodiversity loss, and biodiversity loss harms the crop output and decreases productivity, sustainability, and nutrient value in the food that is needed

.

\

Food insecurity primarily affects marginalized and impoverished groups of people, who are d isproportionately harmed by environmental issues such as this one.

What can we do?

The relationship between agriculture, environment, cultural assimilation, and food security creates a precarious tension. A multidisciplinary approach is required to work towards a solution for this issue. But what can everyday people do to help? Contacting local politicians, joining protests, signing petitions, and making donations or volunteering for environmental organizations are all ways to encourage actions taken towards positive change. Education is also key. Staying up to date on research advancements and encouraging others to stay informed on biodiversity conservation and agricultural systems is vital, as many do not understand this complex conflict.

Finally, buying from sustainable markets, supporting local traditional farming practices, and e ven encouraging wildlife in one’s garden by growing food, all directly contribute to promoting sustainable agricultural practices that increase biodiversity

. Next time you are out apple picking or picking out the perfect pumpkin for your jack-olantern, think about sustainable agriculture, and the ways it is interconnected with environmental and cultural preservation!

16

Land Acknowledgement

We would like to end this issue by acknowledging that at the University of Illinois we are on the lands of the Peoria, Kaskaski, Peankashaw, Wea, Miami, Mascoutin, Odawa, Sauk, Mesquaki, Kickapoo, Ojibwe, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, and Chickasha Nations.

The University of Illinois UrbanaChampaign lands were the traditional territory of these Native Nations prior to their forced removal: these lands continue to carry the stories of these nations and their struggles for survival and identity.

As an environmental magazine, it is necessary to acknowledge these Native Nations and work with them to promote indigenous rights, especially to land, water, and other natural resources.

17

“There is simply no issue more important. Conservation is the preservation of human life on earth, and that, above all else, is worth fighting for.”

―

Rob Stewart, Sharkwater: The Photographs

18

References

Sophia Beem

"Agriculture's Impacts on Biodiversity, the Environment, and Climate." National Academy of Sciences. The Challenge of Feeding the World Sustainably: Summary of the US-UK Scientific Forum on Sustainable Agriculture. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2021). https://doi.org/10.17226/2600.

Thrupp, Lori Anne. “Linking Agricultural Biodiversity and Food Security: the Valuable Role of Agrobiodiversity for Sustainable Agriculture.” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs), 76, no. 2 (2000): 265-81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2626366

Dinaversity. “Dinaversity Video Scribing #1: Agrobiodiversity.” November 18, 2019. Educational video, 2:19. https://youtu.be/NniDVPsjDoI.

Michael Gergeni

Aguinda v. Texaco, Inc., 303 F.3d 470 (2d Cir. 2002). Feige, David (2008). "Pursuin the polluters" Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2022-10-02.

Kimerling, Judith (1991). "Disregarding environmental law". Hastings International and Comparative Law Review. Retrieved 2022-09-30.

Kimerling, Judith (2006). "Indigenous Peoples and the Oil Frontier in Amazonia: The Case of Ecuador, Chevrontexaco, and Aguinda v. Texaco". CUNY School of Law. Retrieved 2022-0930.

Maggie Sampson

Strife, S., & Downey, L. (2009). Childhood Development and Access to Nature: A New Direction for Environmental Inequality Research. Organization & environment, 22(1), 99–122.

Tsevreni I. Towards an environmental education without scientific knowledge: An attempt to create an action model based on children's experiences, emotions and perceptions about their environment. Environmental Education Research. 2011;17(1):53 - 67.

Malo, Sebastien (2021). "Lawyer who sued Chevron sentenced to six months in contempt case". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021.Retrieved 2022-10-02. 19