9 minute read

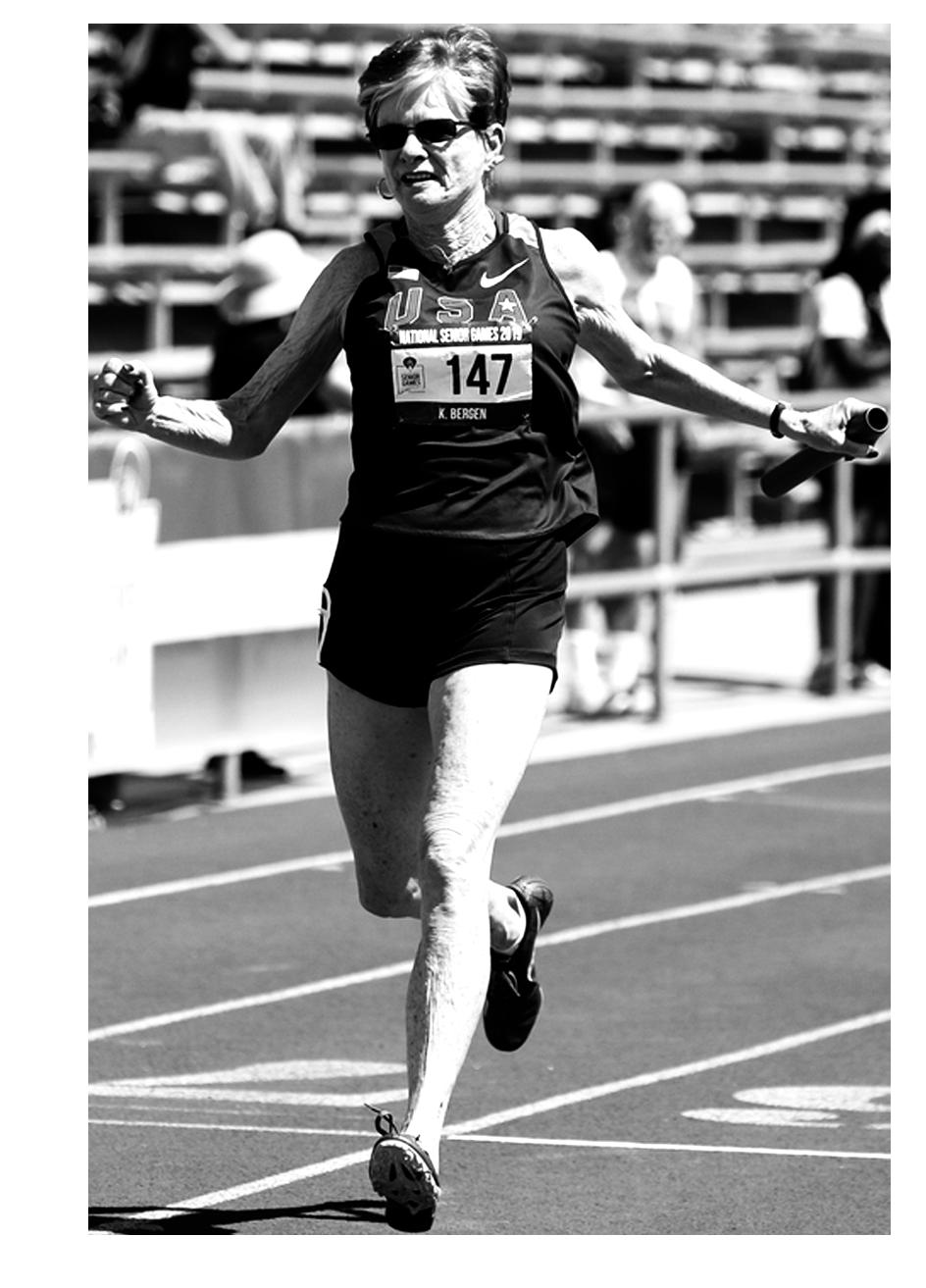

The Competitive Zeal Pushing Kathy Bergen to 23 World Records

Advertisement

Ray Glier

Kathy Bergen would rather kiss a hot iron, or stare at the sun, than lose in track & field. Her nemesis could be a 10-hour plane ride away, not 20 feet away celebrating a win, and Bergen wouldn’t feel any better about second place.

Rietje Dijkman of the Netherlands went 1.16 meters outdoors in the High Jump on September 18, which bested Bergen’s world record of 1.15 for the 80-84 year old division. Ask Bergen how that made her feel and you get this:

“Crappy,” she said.

Bergen is 81 and she is ready to throw down against you right now, this instant, if you walk out on the track with her with laced up shoes.

“I’m here to set world records,” she has said.

That competitiveness is one of the reasons why Bergen, who lives in La Canada, Calif., was named the USA Masters Track & Field Athlete of the Year. Accomplishments in 2020 and 2021 were combined to select the 2021 winner because most of the 2020 season was wiped out by Covid, but not before Bergen had her say in a couple of meets.

The hyper-competitive Bergen went head-to-head with Covid and won. Of course, she did.

She was 80 years old for the 2020 season and the youngest in a cohort is usually the one who gobbles up records for the age group. Bergen didn’t want to let that window close. So she and her husband, Bert, looked far and wide for races in the 80-84 division before Covid could take a grip on the country and interrupt things.

Not surprisingly, they found opportunity in Texas in early 2020. They flew to Houston and she set three indoor world records (60m,10.02, 200m 35.66, and high jump 1.20m).

They went to another meet, this time outdoors in Texas, and she set world records in the 100m (16.62) and high jump (1.15m). It was the high jump record that was eclipsed in September by Dijkman, by a scant centimeter.

That was 2020.

In 2021, Bergen was 81, a year older for the 80-84 cohort, at the USA Track & Field Masters National Championships in Ames, Iowa. Still, she took home medals with wins in the 100m (16.54), 200m (37.20), high jump (1.11m), and discus throw (17.89m).

Not only that, but Bergen ran the lead-off leg in the 4X100 relay in the 65-69 division and her team from the Southern California Striders Track Club set an American record.

The Bergens have been competing for 27 years. She has, at one time or another, set 23 world records, indoors and outdoors, and 33 American records. She has five world records still on the books. Bert is an accomplished high jumper in Masters Track with some national wins of his own.

You might be tempted to make the case that Kathy Bergen is setting world records because the competition is thinning out with age. That might be true, except, she was vanquishing opponents and getting her name in the record books two decades ago starting with the women’s 55-59 division.

It is a remarkable stretch of resiliency for a woman who showed up for her first Masters meet in 1994 in the byzantine footwear of “sneakers.”

Ask her if she saw any of this coming 27 years ago and Bergen says, “I had no idea.”

There is a takeaway here, a significant one, that helps explain her near-three decades run of medal taking.

Rest.

Bergen said she owes some of her durability to Eric Dixon, her track coach from 2010-2020. They mostly worked together remotely and Dixon preached rest over and over to Bergen. She was too enthusiastic about athletics and didn’t know how to switch off.

“I started with him when I was 70,” Bergen said. “I was trying to run every day, play tennis, go to the gym, and high jump. He said I was doing too much; I wasn’t allowing my body to rest.

“So now I do a track workout on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, and then go to the gym in the afternoon to do mostly weights and stretching, and the rest of the time I do less. But I do throw in some high jump workouts. I don’t wear myself out anymore like I used to.”

Here is another takeaway and this should stick with you.

Bergen, like many young girls in the 1950s, did not have an opportunity for track & field, not like the boys. There is no question Kathy could have been a high school competitor, perhaps even a college athlete, if she had come along 25 years later.

The upside of the discrimination is that Bergen does not have 65 years of beat-down on her bones and muscles or psyche. Imagine if, through 6 ½ decades, she had fed the track rage. High school meets, college meets, professional meets, Masters meets.

Women shunned because of their gender are smacking back in later years, catching up so to speak, and it is keeping them healthy and vibrant.

KATHY BERGEN

Kathy was built for the track. Damn straight she could have been a high school, or college star. She was a racehorse, even in grammar school in Brooklyn. She said she could beat all the boys in sprints and it infuriated them. The “Tomboy” taunts came at her, but did no good because, she said, after all, “I was a Tomboy.”

The grammar school and sandlot races against the boys was as far as she got in track. She went to college and studied Economics and had a career and five children.

Two things add up for Bergen and explain her success. She had the genetics and the love of track to become a successful senior athlete.

Bergen’s father, Jim McCaffrey, was a Geezer Jock in his time. He played on the company softball team for Bendix Corporation, a large American manufacturing and engineering company. He was in his 60s and mashing that potato with men 20-30 years younger.

It was Bergen’s mother, Marian, who got her enthralled with track & field.

Kathy was a school girl in the 1950s and her mom would take her to all the big meets in New York; The Millrose Games at Madison Square Garden, Knights of Columbus meets, and New York Athletic Club events. Track was a spectacle in those days, not just in an Olympic year, as it is now.

Track interested her, but Bergen’s family interested her more, so she never pursued the competition. She and Bert moved around the country before settling in southern California. It wasn’t until her youngest was a teen that they entered their first Masters competition at Occidental College in 1994 and were hooked.

Bergen has had her share of injuries, of course. “I’ve pulled everything from the neck down,” she says. But she keeps coming back, undaunted by soreness, or a few more wrinkles. And, she says, “I’ve had a great physical therapist I’ve been working with for 23 years.”

She is going into the offseason, but Bergen is not completely relaxing. Dixon had her varying the workouts so she wasn’t doing the same things over and over. Over the winter, she will run a 200, a 250, and three 200s. Bergen will come back with a 150 meter run, followed by three 300s.

This desire and consistency is how you set 22 world records. Over the next few months, she will work out three days a week around her volunteering in the area, which includes work in a hospital.

With her success, Bergen has a platform to try and convince other seniors to take up track & field. So far, her friends haven’t followed her and Bert out on to the track, Bergen said.

“We understand the challenges for us and our age and what we have to do to maintain a certain level of excellence,” she said. “My friends know the kind of work I put into track and field and they’re not interested. I play tennis with them.”

Their friends may not be converts, but the Bergens manage to spread the word to younger athletes. They help coach a track team at a local Catholic high school and they talk to Girl Scouts and local grammar schools, too.

“You show them that track is truly a lifetime sport,” Bergen said.

Older athletes can be stigmatized by the blather, “It’s just a game” as if their dutiful training is over-wrought. But why shouldn’t seniors, like Bergen, be as competitive as the younger generations? Who says the yearn to win has to switch off at a certain age?

Kathy Bergen would rather kiss a hot iron, or stare at the sun, than lose in track & field. Her nemesis could be a 10-hour plane ride away, not 20 feet away celebrating a win, and Bergen wouldn’t feel any better about second place.

Ray Glier has written for various media for over 40 years, as a contributor to national publications including The New York Times,Vice Sports, USA TODAY,The Miami Herald, The Boston Globe,Atlanta Journal-Constitution and The Washington Post. The author of five books, Glier has a passion for master sports and seniors athletes, and shares their stories of triumph and joy in his unique, inspiring, and always moving weekly newsletter, Geezer Jock. For more great masters sports content, subscribe to Ray’s FREE weekly email at geezerjocknewsletter.com.