Self-expression and Cultural Identity found in Emancipation

By Faith Greene

EMANCIPATION Day means different things to many people. While some see the monumental holiday as an opportunity to promote their traditional culinary skill crafts, and jewellery, others recognise it as an opportunity to find a sense of identify and acknowledge their roots.

At this year’s Main Street Emancipation Exhibition, the Guyana Chronicle met a number of eager passersby and exhibitors displaying their wonderful work of art.

Ingrid Goodman, one of the many persons browsing through the exhibition, shared: “Emancipation is what we live by. We recognise our freedom, what our ancestors went through, and this is a way of life. It’s emancipation every day of the year, and this is one

celebration that we look forward to. It’s very sacred to us Africans here and our black people here in Guyana. This is about us,”

Echoing Ms. Goodman, Esther Gittens, another passerby, stated that she has been celebrating being her culture for more than 30 years. “I have used this emancipation season to help me to heighten what I have already been doing to emancipate myself,” a gleamy Gittens said.

The eager woman pointed out that she wears her African garb proudly everyday as a stamp of identity.

“I’ve been wearing my African clothes for 30 years, and I wear it every day. As soon as you see me, Africa comes to mind because I make sure I have that stamp on me. I’m black and I’m proud, I’m African and I’m

Continued on page 3

Emancipation on Main Street, Georgetown

Self-expression and Cultural Identity...

proud, every single day of the year.”

“Emancipation is not a seasonal thing, it’s every day. It’s a way of life. We shouldn’t only eat our foods, and wear our garments alone on the first of August, or around this time; we should do it every day,” she added.

According to Gittens, while August 1st is a good time to start, the celebration of freedom should continue all year round. She pointed out that Emancipation Day is about more than just the food and clothing, but about the spirituality, unity and collectiveness.

“We as African Descendants, wherever we find ourselves, especially in the closing of this decade, we

should be more mindful and appreciative of what our ancestors went through, the sacrifices they made, so that we could celebrate today, ” she expressed.

Meanwhile, Frankie Limerick, from Beterverwagting on the East Coast Demerara, was among the many exhibitors, displaying products from his business -- Frankie Limerick Seaglass and Shell Crafts. He remarked that for him, Emancipation Day means that he can express himself freely, and his culture.

Eon Waterton of Waterton Arts and Crafts, also from Beterverwagting, stated that Emancipation for him means a lot. He related that it feels good to be free. Additionally, from Nigeria, Nnaemeka Alexander

Njoku of N.N Collection, expressed deeply that he has been coming out on Main Street since 2021 to showcase a variety of African print outfits.

He said, “It’s always good for a short period of time and it makes me proud seeing people of diverse races putting on things we made back in Nigeria.”

According to Njoku: “Emancipation, for me, I won’t say it means freedom because I’m Nigerian natural. So, for me, Emancipation means expressing our cultural heritage. What it means to be an African, what it means to be Nigerian; on that day we are putting it out and display it, let the whole world see even if it’s just for one day.”

From page 2

Eon Waterton

Frankie Limerick

(From left) Esther Gittens and Ingrid Goodman Nnaemeka Alexander Njoku

Those who came before us A look back at the leaders who paved historic paths

FORCIBLY uprooted from their birth place, over three million Africans were shipped across the Atlantic Ocean in what was known as the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Stripped of their names, religions, cultures and identities, they were auctioned off and sold as slaves to British-owned colonies to work on plantations in the Caribbean.

By the 1760s, there were about 15,000 slaves toiling endlessly across the three colonies of the then-British Guiana – Essequibo, Demerara and Berbice. Eventually, the slaves had become exhausted of living a life of torture and captivity, and so, several of them banded together and began plotting and planning their escape. Several attempts were made, but the African slaves remained shackled to the inhumane treatment they received on the plantations. Moreover, their attempts to escape in the first place were heinously rewarded as some were flogged, while others suffered amputation or were killed.

CUFFY AND THE RIPPLE EFFECT

However, despite the British attempt to instill fear in the slaves, their determination and strength led to one of the Caribbean’s first and largest slave rebellions. Led by a house slave named Cuffy (or Kofi), the 1763 revolution is recorded as a pivotal move in the abolition of slavery.

Creating a ripple effect, Cuffy, with his two lieutenants -- Atta and Akara -- by his side, led 3,833 enslaved Africans to their freedom. Together, the Berbice slaves overran plantation Magdaleneburg, removing the colonial masters, and taking their freedom.

Cuffy had planned the revolt just as two shiploads of people from Africa had arrived at the docks, which significantly increased the number of Africans in the fight to overthrow the 346 colonial masters.

News of the rebellion spread like a forest fire on a hot day and soon enough uproars began at plantations across Guiana and in other Caribbean nations, such as Barbados and Jamaica.

Within one month, Africans were in full command of most of the plantations in Berbice. Cuffy then declared freedom for the enslaved Africans, and they managed the plantations for almost a year. Unfortunately, after the plantations were reconquered by the Dutch, Cuffy shot himself in the head, in a bid to never submit to his enslavers.

Although their freedom did not last due to Dutch re-inforcements arriving by ships with heavy machinery and artillery to recapture the slaves, Cuffy left a lasting legacy, one that inspired other slaves to fight for their freedom and to never give up until they were free.

The February 23, 1763 Cuffy-led revolution was recorded in European history as the first major revolution by Africans in the western hemisphere and influenced several other revolutions in the west, including the Haitian revolution led by Toussaint L’Ouverture.

Currently, a monumental

Damon led a protest which resulted in some 700 apprentices downing their tools in support of Damon’s cause. On August 3, 1838, they protested the apprenticeship scheme. The following morning, the freed slaves were more than surprised, and became angry when they were ordered by their former masters to return to work. However, the protests continued and by August 9, the labour situation had worsened with ex-slaves from Richmond to Devonshire Castle gathered in the Trinity Churchyard at La Belle Alliance to stand beside Damon. Governor Smyth addressed the workers at Plantation Richmond, telling them that the apprenticeship period was still in force and they should go back to work. He arrested the leaders of the peaceful demonstration.

This bronze monument of Damon is located next to the Anna Regina Town Hall, on the Essequibo Coast

DAMON AND THE FALL OF LA BELLE ALLIANCE

After Cuffy’s demise, the fight for freedom did not stop. Eventually, the African slaves gained the right to liberation on August 1, 1834. However, the road to freedom was not smooth sailing, because, despite having the Emancipation Act passed in 1833, the now freed Africans still had to fight to be treated fairly.

They were transitioned into a period of apprenticeship and continued to work with their former masters for miniscule wages. This did not sit well with the ex-slaves who had a different vision of what life would be like after freedom.

What started the fall of La Belle Alliance in Essequibo was a problematic move by the owner of Richmond Sugar Plantation, Charles Bean, who stirred up trouble by killing the pigs and cutting down the fruit trees that the former slaves had been rearing for their livelihoods. His excuse for this destruction of the exslaves’ properties was that their pigs were destroying the roots of his young canes.

In rebuttal to Bean’s destruction, an ex-slave named

Pinpointed as the “captain” and “ringleader” of the unrest, Damon was hung in front of Parliament Buildings at noon on October 13, 1834. Although his attempts then were futile, the fight for freedom did not end with his death. His resilience influenced many other ex-slaves and served as a warning to other plantation owners that the Africans were a strong and brave people. Also in monument form, the statue of Damon stands next to the Anna Regina Town Hall, on the Essequibo Coast. These heroes fought the greatest for us all to be able to experience the freedom and the Guyana that we have today.

1823

Cuffy and Damon were not the only ones who lead uprisings across the country; in fact, it is believed that about 12,000 enslaved Africans from 55 plantations were involved in one of the turning point in the fight against the British imperial plantation system and global chattel slavery more than 200 years ago.

This event, which is known as the 1823 slave rebellion, saw a display of incredible daring, courage, the effectiveness of group action and the capacity of the enslaved to shape their own fate by attacking the institutional and physical embodiment of their servitude.

They demanded their freedom but did so through non-violent means. The twoday rebellion was unsuccess-

Continued on page 5

statue of Cuffy adorns the Square of the Revolution, in the capital city of Georgetown.

The 1763 monument, also known as the Cuffy Monument

Those who came before ...

ful, with many killed after the colonial forces resorted to violence.

Historian, Viotti da Costa’s outstanding book ‘Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood’ recounted the tale of what is known in Guyana as the 1823 slave rebellion or the Demerara revolt.

“The rebellion started at Success and quickly spread to neighbouring plantations. Beginning around six in the evening, the sound of shell-horns

and drums, and continuing through the night, nine to twelve thousand slaves from about sixty East Coast plantations surrounded the main houses, put overseers and managers in the stocks, and seized their arms and ammunition. When they met resistance, they used force. Years of frustration and repression were suddenly released. For a short time, slaves turned the world upside down. Slaves became masters and masters slaves.”

Two leaders emerged

during the planning period: Jack Gladstone, a cooper on Plantation Success, and his father, Quamina, a senior deacon at a church led by English Protestant missionary, John Smith. Gladstone and others planned the uprising, but Quamina objected to any bloodshed and suggested instead that the enslaved should go on strike.

Quamina’s call to remain peaceful fell on deaf ears.

The uprising quickly became deadly as hundreds of rebels were hunted down and

killed, including two hundred who were beheaded as a warning to other enslaved people.

Gladstone was deported to St. Lucia while Quamina was hunted and killed as warning to others.

To date, an emblem of these men sit just mere feet away from the Atlantic, along the Seawall Road opposite the Guyana Defence Force’s Camp Ayanganna headquarters.

From page 4

Damon’s monument

The 1823 monument

Soiree

DANCE and music are common forms of expression in Guyana and many other parts of the world. In Guyana, dance and music are heavily influenced by the country’s multicultural society.

In Guyana, particularly, people of African descent, who are connected to the traditions of old, use dance and music to commemorate important social and religious events.

One of these many festivals is Soiree, a tradition held yearly in celebration of the Emancipation of enslaved Africans in Guyana.

Similar to ‘Queh Queh’, a pre-marital celebration, Soiree is the gathering of family and friends in celebration.

The joyous occasion is celebrated with drumming, chanting, and Shanto dancing, used to invoke the spirits of the African ancestors.

On the night of July 31st, or even on previous nights before August 1, soirees are held in predominantly Afro-Guyanese villages along Guyana’s eastern coast.

This cultural festivity has its roots in the 1800s, and is indigenous to villages along the coast and banks of the main rivers that Africans bought when they were liberated from slavery.

Villages that have embraced this tradition even now are Hopetown, Ithaca, and Belladrum in Berbice; and Buxton, Victoria, and Bagotville in Demerara.

The village of Hopetown was bought by former enslaved Africans in the 1840s, which is around the time the Soiree tradition emerged.

Today, drumming, marching and dancing would start around 18:00hrs on the eve of Emancipation in an area of the village called ‘Twenty-Two’.

The large crowd would disperse into groups to keep their separate libation ceremonies, while the main access road cutting through the villages is flooded with hundreds of Guyanese with their music sets, creating a party-like atmosphere.

Traditionally on July 31, there is a thanksgiving church service at the village’s traditional church. At 22:00hrs, the villagers then head to the village koker for the libation ceremony.

They dance and mimic the sounds of the drums and other musical instruments. Upon arriving at the koker, the participants sing as they “invite the ancestors to join the celebrations.”

When it is certain that the ancestors are “within their midst,” the celebrants move over to the community centre for a grand enjoyment.

At this time, the centre is filled with spectators, dancers, drummers and singers, as well as children. At about 06:00 hrs the following morning, the libation ends, but not the Emancipation celebrations! This continues throughout the day.

A packed programme, prepared weeks in advance, is started at about noon. The villagers gather at the centre of the village, once again, to witness the traditional concert.

This includes African dances and songs, skits, speeches, and, most importantly, storytelling.

(Photo sourced from True African Art)

Massive Emancipation celebrations expected in Macedonia Joppa, Berbice, this year

THE Macedonia Joppa Voluntary Committee (MJVC), a registered non-profitable organisation, East Corentyne, Berbice will celebrate 190 years of Emancipation to commemorate the abolition of slavery in Guyana, and the end of years of brutalisation, dehumanisation and the liberation of African people, today.

The holiday is significant, not just as a calendar event but as a new lease of life for the Guyanese nation as we know it. It is a day of remembrance, and an opportunity to reflect on the courageous efforts and sacrifices of enslaved men and women in the fight for their freedom.

The Macedonia Joppa Voluntary Committee (MJVC) will mark the occasion with the largest celebrations ever seen in Berbice.

During the last two years, Emancipation celebrations in Berbice were organised and sponsored by the MJVC group, and were well attended on both occasions by the residents from across the region and beyond. This year’s celebrations are expected to attract thousands of people in and out of the region from as far as West Coast Berbice to Molsen Creek on the Coren-

tyne and beyond. Like in previous years, this year’s Emancipation celebration is expected to be the largest and only celebration of its kind in East Corentyne. It will be an all-day gala family celebration, starting at 10:00hrs with a road march from Brighton Village to the Eversham Village Community Centre Pavilion, where there will be a day of fun for all, especially for the children who will participate in several cultural, social, and educational activities, including the recital of poems, singing of folk songs, playing of games, and dancing to a variety of songs, and an education quiz competition on slavery and Emancipation.

There will also be drumming and African dancing and African dishes to highlight Africa’s interesting tribal tradition.

During the last two years, Emancipation celebrations in Berbice were organised and sponsored by the MJVC group, and were well attended on both occasions by the residents from across the region and beyond. This year’s celebrations are expected to attract thousands of people in and out the region from as

far as West Coast Berbice to Molsen Creek on the Corentyne and beyond.

Like in previous years, this year’s Emancipation celebration is expected to be the largest and only cel-

ebration of its kind in East Corentyne. It will be an allday gala family celebration, starting at 10:00hrs with a road march from Brighton Village to the Eversham Village Community Centre

Pavilion, where there will be a day of fun for all, especially for the children who will participate in several cultural, social, and educational activities, including the recital of poems, singing of folk songs, playing of games, and dancing to a variety of songs, and an education quiz competition on slavery and Emancipation. (Dr. Asquith Rose, MJVC Chair).

Post-Emancipation strides and the militant women of Buxton/Friendship

DESPITE passage of the Emancipation Act in 1833, the new-found freedom that the ex-slaves had once craved was no paradise. There were more battles to be fought and the liberated Africans found themselves spearheading protest after protest to ensure that their civil rights were not trampled on.

Soon after slavery was officially abolished in 1838, the ex-slaves began what is known today as the Village Movement -- they pooled their resources and purchased plantations where they settled and started to build new lives for themselves. Villages were established, communities were built, and co-operative societies and village councils were developed. Today, many of these structures remain an integral part of Guyana’s local government body. One

of these communities is Buxton-Friendship, located on the East Coast of Demerara, once called Plantation Orange Nassau. The village became known for having the largest local authority in what was then the colony of Demerara. As the first village to be established in an organised manner, this local authority took a leadership role in dealing with the plantation owners and the central government, which really was one and the same. As far as the British were concerned, the liberated Africans were a threat, having had “too much independence.”

Seeing their successes and how they were smoothly running their own affairs, a major scheme was “cooked up” by the British to suppress the villages which had begun to thrive. In attempts to un-

dermine them, the legislature enacted a law in 1856 granting powers to the government to levy “improvement taxes” on the properties of villagers. This, however, did not sit well with the Africans, especially the Buxtonians.

Consequently, a group of proprietors of Friendship, led by James Jupiter, Blucher Dorsett and Hector John, was the most active and determined of the ex-slaves. They headed a list of 88 proprietors from Buxton who sent a petition to the governor of the colony, asking him to reconsider the tax levy.

Turning a blind eye to their plea, the governor refused to listen to the men. Instead, he branded the men as ringleaders and accused them of organising unrest. In response to the villagers, the government confiscated the properties of James Jupiter,

Dorsett, Hector John, Webster Ogle, Chance Bacchus, and James Rodney Sr.

To enforce his decree, the governor dispatched a contingent of policemen and a detachment of the 21st Regiment of Fusiliers. They took possession of the houses, throwing the occupants and their belongings into the streets.

The villagers made several attempts to meet with the governor to discuss their complaints, but he again refused to meet with them. They then turned to the Honourable Clementson, a member of the Court of Policy (legislature) for help, but this too failed.

To this end, the Africans felt they had no recourse but to initiate protests and unrest. This meant that those persons who had bought

the confiscated houses were unable to occupy them and live their lives in peace. In one instance, James Rodney mobilised a huge mob and forcibly took possession of his former property from the new owner. Attempts were also made to contact the Queen of England herself to express their disapproval; unsurprisingly, that too was in vain.

WOMEN ASSEMBLE

As a final straw, the Africans learnt that the governor was expected to travel by train through the village to inspect the newly extended railway farther up the coast. Deciding to confront him face to face, a group of women mobilised a delegation and forced the governor to listen to them and resolve the problem once and for all.

Standing their ground,

these militant women cornered the governor on the train tracks; they blocked the vehicle from going any farther and locked the wheels of the train with large chains and padlocks. This course of action left the governor no choice but to listen to the women. The men joined in moments later and, eventually, the governor listened and with immediate effect, all taxes were removed from properties in Buxton. While the train tracks have been covered by new infrastructure over the years, the foot prints of these women are still embedded in the soils of the village and is a constant reminder that the women of Buxton are descendants of bravery and resilience.

(This story was first published in 2021 and written by Naomi Parris).

Blucher

A Journey through history — The Caribbean’s slave trade and Emancipation

By Faith Greene

ON this day, 186 years ago, thousands of African people from Guyana and other Caribbean nations gained their freedom from the physical chains of slavery that had kept them bound for centuries.

They were finally free to determine what was suitable for them and what was not, all within certain limits of course.

The then-enslaved Africans were victims of what some historians described as one of the world’s largest crimes committed against a group of people.

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in a recent publication titled The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade (2022), labelled this crime as one of abduction and abuse that has altered the global landscape and created a legacy of suffering and bigotry, all of which still exist today.

The 1400s Trekking back to the tales of centuries ago, the Europeans, in search of wealth, sent several ships and armed militia to exploit new lands, many of which had already been occupied by Indigenous peoples. These lands or territories

were known then as ‘the Americas’ and the home to extraordinary natural resources which provided great opportunities to gain power and influence for Portugal, Spain, Great Britain, France, Italy, Germany, and Scandinavian nations.

History tells us that these lands produced an abundance of gold, sugar and tobacco, all of which were sought after by the Europeans to generate wealth.

They first attempted to enslave the Indigenous peoples and they were met with much resistance, but in their determination to extract wealth from these distant lands, they sought labour from Africa, launching a tragic period of kidnapping, abduction, and trafficking that resulted in the genocide and enslavement of millions of African people.

THE SOCIAL PYRAMID

According to the Guyana Chronicle’s archives, slave societies in the Americas were formed according to power, prestige, privilege, and colour. At the top were the Whites, which comprised government officials, plantation owners, managers, merchants, clergies, small shopkeepers, craftsmen, and indentured servants. At the middle were

Blacks and free Coloureds, who were classified as Mulatto, Quadroon, and Sambo. This was a sandwich group that served as a social lubricant between the highest and lowest layer of Guyana’s slave society.

And at the lowest layer were the enslaved Africans, who were further stratified into the fields, house, skilled and urban slaves.

Each layer of stratification was hierarchically organised along firm boundaries. The structure of slave society was shaped like a social pyramid.

David Lamberts ‘An Introduction to the Caribbean, Empire and Slavery’ published in 2017, states that the Europeans came to the Caribbean in search of wealth. The Spanish had started out looking for gold and silver, but there was little to be found. Instead, they tried growing different crops to be sold back home.

After several unsuccessful experiments with growing tobacco, the English colonists tried growing sugarcane in the Caribbean. This was not a local plant, however, it grew well after being introduced. According to Lambert, several people in Europe wanted the products of sugarcane, and as a result, those ‘planters’ who grew it became very wealthy.

Lambert, a Caribbean History Professor at the University of Warwick, in the United Kingdom, penned that the spread of sugar plantations in the Caribbean created a need for workers. Planters turned to buying enslaved men, women and children, brought from Africa.

It is believed that five million enslaved Africans were taken to the Caribbean.

“As planters became more reliant on enslaved workers, the populations of the Caribbean colonies changed, so that people born in Africa, or their descendants, came to form the majority. Their harsh and inhumane treatment was justified by the idea that they were part of an inferior ‘race’. Indeed, complicated ways of categorizing race emerged in the Caribbean colonies that placed ‘white’ people at the top, ‘black’ people at the bottom and different ‘mixed’ groups in between. Invented by white people, this was a way of trying to excuse the brutality of slavery.”

THE UPRISING OF REBELLIONS IN GUYANA

In Guyana, the Dutch European established the settlement, British Guiana in order to trade with the Indigenous people. However, due to the competition with other

European countries to gain territory, it soon became a commercialized base and by the 1660s, more than 2000 slaves had been brought to the Dutch territory to work on plantations.

According to the textbook, Social Studies Made Easy, they had lured Africans from several countries in Africa and brought them to then British Guiana to work on sugar plantation as slaves, much like what happened in several Caribbean Countries during that period.

By 1763, a slave revolt began on two plantations on the Canje River in Berbice by a West African slave named Cuffy. This was due to the harsh treatment of slaves by the Europeans which additionally caused many slaves to commit suicide, to run away, and eventually give rise to several rebellions.

Other persons involved in this rebellion were Akara, Atta, Accabre and Gousarri.

Unfortunately, this rebellion failed because of disunity among the Africans. Cuffy committed suicide, and the other leaders were defeated. Another rebellion arose on Plantation Le Ressouvenir in 1823.

According to the textbook, Quamina and his son, Jack Gladstone, were held responsible for this uprising, which proved to be unsuc -

cessful after the leaders had discouraged the Africans from being violent.

Quamina was shot, and Gladstone was sentenced to deportation and taken to St. Lucia where he was sold into slavery.

Rebellions continued across the Caribbean with uprisings in Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and other territories.

Emancipation, however, came years later on August 1, 1838, after people like Thomas Buxton, Thomas Clarkson, Granville Sharp, George Canning, James Ramsay and William Wilberforce campaigned to abolish slavery. While slavery was abolished in 1834, slaves still had to work on plantations, but were paid small wages for their labour.

Some Africans, like Damon, refused to work and in 1834, he started a protest which resulted in him being hanged.

After their Emancipation, the Africans began to buy plantations. The first plantation bought by the freed slaves was plantation Northbrook, which was later renamed Victoria. The Africans earned a living by practising peasant farming of crops such as rice, for example, and trade work (masonry, carpentry, plumbing and handcraft).

Making traditional African dishes the Guyanese way

FOOD and culture are interwoven. Traditional spices, recipes and food preparation techniques were passed down from generation to generation. This is true for cultures across the world.

The processes of preparing, serving and sharing certain foods and drink might appear simple, but could be complex when considering the social and cultural significance of these foods.

For Guyana, which is a melting pot of cultures, food plays a vital role in preserving culture across generations. The Africans, one of Guyana’s major ethnic groups, have made a big contribution to the the country’s culinary arts.

While attempts were made by colonising powers to strip the enslaved Africans of their sense of

identity during slavery, there was a spirit of resilience among Africans and African descendants

to preserve remnants of culture and tradition. The art and science of food preparation is one such

preserved remnant.

African cuisine, as we know it in the West Indies, is a combination of locally available fruits, cereal grains and vegetables, and milk and meat products. In some parts of the African continent, the traditional diet largely includes milk, curd and wheat products.

Africa is not, however, a single space nor a single culture. Comprised of more than 50 countries and many smaller ethnic groups, the continent’s diverse makeup is reflected in the many different eating and drinking habits, dishes, and preparation techniques.

In Central Africa, for example, the basic ingredients in most dishes are

plantain, cassava, chili, peppers and an array of vegetables and ground spices.

In Guyana, our understanding of African dishes incorporates all of these ingredients, with a modern twist and Caribbean flare, making use of fruits and vegetables that are readily available in the South American county.

These foods include Metemgee, which is a soup-like dish with ground provisions, coconut milk and large dumplings, eaten with fried fish or chicken; Conkie, a sweet cornmeal-based treat cooked by steaming the cornmeal in banana leaves; and pumpkin and ‘Foo Foo’,

Continued on page 11

Foo-Foo paired with a beef stew (Photo credit: Guyana Dining)

Making traditional African...

which is a dough made from boiled and mashed ground provision. These dishes have become a staple in African-descended households on Sundays, mostly, but especially during emancipation celebration.

RECIPE GUIDE: Metemgee (Metagee)

Ingredients:

• 1 dry coconut

• Three-quarter pound of mixed meat

• Approximately one pound of fried fish or salted fish

• One pound of cassava

• One pound of plantain (you can choose whether green, ripe or ‘turning’)

• One pound of eddoes, yams or dasheen

• One large onion — cut into rings

• A half-pound of ochro (okra)

• Dumplings (optional)

Preparation:

• Cover the mixed meat with water and boil for half an hour. Put salted fish to soak in water; if using fresh fish, this may be fried or placed on top of vegetables about 10 minutes before the end of the cooking time

• Grate the coconut, pour one pint of water over, squeeze well and strain to extract the coconut milk. Pour over the meat

• Peel the vegetables, then put the meat and vegetables to boil in the coconut milk. Cook until almost tender

• Put the salt fish, with the skin and bones removed, or fresh fish or fried fish on top of vegetables. Add the onion and ochro.

• Cook until the coconut milk is almost absorbed

• If dumplings are used, they should be added about eight minutes before the vegetables are ready

‘FOO FOO’

Ingredients:

• Two pounds of hard yams

• One pound of cassava

Preparation:

• Wash, peel and cook vegetables in boiling water

• When cooked, do not remove from boiling water or else vegetables will become cold and unmanageable

• Remove string from cassava; take cassava from water and pound first before adding yam to mortar

• Pound to a fine texture until thoroughly mixed

• Use some of the same warm water for dipping the mortar stick and for

adding to the ‘foo foo’ to bring to the right consistency

• Dip a metal spoon in clean warm water and remove ‘foo foo’ in balls from the mortar. Cover and keep warm. Serve.

CONKIE

Ingredients:

• One coconut

• One pound of pumpkin

• One pound of cornmeal

• One ounce of lard

• One ounce of margarine

• One teaspoon of salt

• Sugar to taste

• Four ounces of dried fruits

• One teaspoon of black pepper

• Banana leaves for wrapping

Preparation:

• Grate the coconut and pumpkin

• Add all other ingredients

• Stir in enough water to make a mixture of dropping consistency

• Wipe banana leaves and heat to make pliable

• Cut into pieces of approximately eight inches squared; wrap around filling and tie with twine

• Place in boiling water and boil for 20-30 minutes.

From page 10

Metemgee

Conkie

Local cultural groups receive grants for Emancipation festivities

SEVERAL cultural organisations representing Afro-Guyanese communities across the country, last Friday, received funding to support Emancipation festivities.

The cheques were handed over by Minister Kwame McCoy, Minister within the Office of the Prime Minister with responsibility for Public Affairs, during a simple ceremony held

at the Arthur Chung Conference Centre (ACCC).

During brief remarks, Minister McCoy emphasised the importance of celebrating African contributions and unity among Afro-Guyanese people.

The government, he noted, has always committed to inclusive growth, supporting Afro-Guyanese small businesses with targeted cash grants while

ensuring that a greater number of Afro Guyanese groups have access to essential financial support.

These commitments, he further explained, are in keeping with the $100 million allocation, designated funds for Afro-Guyanese causes as part of the United Nations Decade for People of African Descent.

“These initiatives transcend

mere financial support; they are about empowering Afro-Guyanese communities, to thrive and to excel in diverse fields such as education, agriculture, healthcare, sports, music, and the arts. Our government is committed to the holistic development of all Guyanese as evidenced by our policies designated to foster an environment where every

individual, regardless of their background, can prosper and contribute meaningfully to the development of our country,” the Minister said.

The Minister highlighted that while there have been divisive attempts to undermine this unity through race-baiting and exclusionary policies, the government will continue to work collectively to build a future where all people can realise their full potential.

“We have been in the forefront of the global calls and we’ll continue to call for reparative justice and frameworks to be enacted by the colonial legacy countries to help overcome generations of exclusion and discrimination, recognising the region’s history and the legacies of enslavement.”

“Our government has been consistent in working with the legislature, civil society, and representative community groups, national organisations, state parties, and international bodies to apply efforts to address racism, intolerance, bigotry, and hatred, wherever they exist, and in whatever form to advance the cause of global freedom and justice for all our people,” he added.

Minister McCoy highlighted the government’s support for Afro-Guyanese communities through inclusive policies and targeted initiatives, while calling for continued unity and collective action to ensure full potential realisation.

Meanwhile, in an invited comment to this newspaper, Archbishop Mark Hunt of a local Baptist church in Bagotstown, expressed gratitude for the timely funding.

According to him: “It’s really a motivation, especially for the African churches.”

The Archbishop explained that he has a grand church celebration planned for this year’s Emancipation and the monetary funding will support the church’s efforts in keeping the traditional and religious values of the community alive.

Another recipient, Lawrence Havron of the number 53 Village Emancipation group, noted that the funding will support his communities’ festivities.

According to Havron, the group had benefitted from a similar grant programme previously. He is hoping that even more support will be given this year.

“I appreciate what the government has done with this emancipation. Our group will put our best foot forward to get the activity at a level to satisfy our people. If the funding is to the way that we expect, it will do our planning good,” Havron said.

Rondz McLennan, another recipient, disclosed that she intends to use the funds to support festivities that will target youths.

“Our aim is to every year enlighten the younger generation as to the history of their ancestors and we feel this grant is going to be able to assist us in doing that.”

McLennan noted that her group has a two-day packed scheduled for the upcoming Emancipation Holiday.

“We have a two-day activity on the 31st of July. We are having a libation and a cook-out and the 1st of August we are having a sports day and the evening we are having a cultural exhibition.”

A recipient receiving her grant from Minister Kwame McCoy, minister within the Office of the Prime Minister with responsibility for Public Affairs

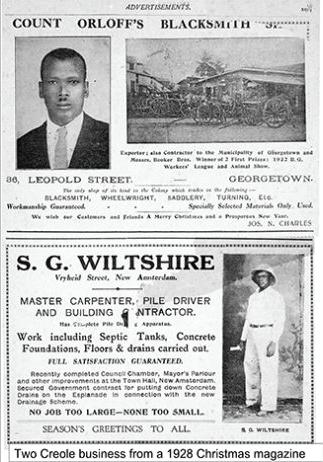

How they lived beyond Emancipation

EMANCIPATION came to the colonies from the throne of the colonies in favour of the Industrial Revolution. But to the plantation/ merchant hierarchies of the colonies, it was met with vexations that lasted beyond the turn of the next century. The manumitted populations did not conceive that their future would be subject to schemes to shackle their abolition, and circumvent their efforts by the local colonial government, the majority of whom were the plantation owners and merchants, their former enslavers.

To the Creole Africans, the concept of constructing of the villages and showing how they would proceed to develop was based on their own ancestral vision. “In many of the communal villages, the villagers established collective farms. As we have seen, this co-operative peasantry founded a great enterprise, developed it with marked business acumen, and forced into the colony what seemed to the colonists a perilous doctrine. It was the most revolutionary attempt, though small in scale in global terms, at rehabilitation after slavery. The Africans were thus immediately able to set up an economic system and a civilisation that rivalled capitalism. The plantation at once went into action against the co-operative village system. In the ‘London Times’, the co-operatives were seen as “Little bands of socialists living in communities.”

Under the combined attack of the plantation and the government from outside, and the church from inside, the collective economy collapsed” (See Scars of Bondage by Eusi and Tchaiko Kwayana; Free Press 2002). Thus, the liberation of the manumitted Creole slave was a historical feature that was met with severe malice by a race-hate-driven plantocracy towards the destruction of its economic liberation.

In the townships of Stabroek and New Amsterdam, repressive methods would be applied in diverse ways. The manumitted populations entered several occupations. Thus, licences had to be acquired to perform these enterprises of self-employ-

ment that listed outside of artisans and other skills perfected on the plantations; thus, the boatmen, owners of cabs, mule and donkey carts operated for hire, and, most importantly, the high costs for huckster and shop licences were a sinister application to repress the Creoles from engaging profitably in the lu-

crative retail business. It was the planters and the established European merchants as the majority in the combined court who fixed the colonial taxes. Taxation on articles of common consumption embodied the nefarious plan to artificially raise the cost of essential consumer products to impoverish the Creole

population, forcing them to return to plantation labour. One of the most contentious issues was taking the taxes paid by the villages to aid the planters to import immigrant labour, causing the predictable floods and loss of livestock and produce, and, more important, infant mortality. This conflict also

involved the manipulation of the eager Portuguese indentured labourer as ‘the enthusiastic fall guy’ to grab the ambitions of the Creole. This orchestrated plot led to social colony tensions that exploded between the Creole and the Immigrant Portuguese in the last half of the 19th century, with the implosion of the

‘Angel Gabriel Riots’ 1857, and the “Gil-bread Riots” of 1889.

Though records have shown shopkeepers attempted to further impoverish the Creole population through crooked scales and inflated prices, along with the boast to the Creoles that with the murder of any other citizen, the King of Portugal had commanded that they be abstained from capital punishment in the colony (The case of Antonio D’Agrella, see ‘The Portuguese of Guyana:’ Mary Noel Menezes, R.S.M.). But the Creole population did not sit and only pray; they protested and defended their rights with civil unrest, not only directing their anger to confronting the scapegoats before them.

But as Governor Lyght confirmed, “that the temper of labourers is soured, it is not at all uncommon for remarks not of the civilist kind being made by groups of Creoles on meeting carriages and horses of officials to the effect that they the people were taxed {for} such luxuries.” This admission accepted that discontent was rife, widespread and openly vented. The Creole population was pressed into a debilitating tax after the ‘Angel Gabriel Riots’ to re-imburse the stores affected. The architect of this was Governor Philip Wodehouse; on his way to the Stabroek wharf in July 1857, the population vented their anger by stoning him. This punitive tax was mercifully repealed by pressures from missionaries and other local pressure groups, as well as from the Anti-slavery Society in Britain. See-Part 2 ‘Themes in African-Guyanese History.’

With time, the Creole moved towards the public service, and dominated the stevedore areas of employment. These areas also had their extreme difficulties that led (mainly the stevedore wages) to the turn of the century 1900s-1905 disturbances that birthed the Union movement, and eventually the genesis of the significant local political movement.

(Barrington Braithwaite)

Emancipation Day Messages

PPP: Let the sacrifices, achievements of our Afro-Guyanese brothers, sisters serve as important lessons

THE People’s Progressive Party (PPP) wishes to extend the warmest greetings to all Guyanese, especially our Afro-Guyanese brothers and sisters, on the occasion of the 186th Anniversary of Emancipation.

Slavery remains the most cruel and inhumane system of subjugation and discrimination known in human history. The celebration of its ab-

olition is a duty for every human being. This occasion provides an opportunity to reflect on the tremendous sacrifices made by our Afro-Guyanese ancestors, who were brought inhumanely to this land in chains to provide free labour for the sugar plantations. They were stripped of their humanity and dignity, forced to toil long hours, and many were tortured and brutally

killed for simply standing up for their rights.

In their long and unyielding march for free-

dom, many battles were fought, including the Berbice Slave Rebellion, led by our nation’s

National Hero, Cuffy. When freedom finally came, the freed slaves and their descendants demonstrated exceptional industry, thrift, and financial acumen, acquiring large portions of land that today remain the foundation of our village movement.

Their contributions made to every facet of life in this nation are immeasurable.

As we celebrate this

important historic and national occasion, we urge every Guyanese to reflect upon the struggles, sacrifices, and remarkable achievements of the slaves and their descendants. Let these serve as a source of inspiration and guidance as we continue to work together to build a united and democratic nation.

AFC: Reflect upon the sacrifices made by our African ancestors in the making of a modern Guyana

On this August 1, as we celebrate Emancipation Day in Guyana, we commemorate a pivotal moment in our history when the chains of enslavement were broken, and our ancestors were given their freedom. This day in 1834 marked the end of a brutal era of chattel slavery in the West Indies. However, it was not until 1838, after a period of "apprenticeship" intended to transition enslaved Africans to free 'paid' labourers, that true freedom was realized.

Emancipation Day holds profound significance for Guyanese of African descent. It is a day of reflection, remembrance, and reverence for the immense sacrifices our forebears made. We honour their resilience and unwavering spirit, which found its first powerful expression in the Western Hemisphere's first successful slave rebellion in 1763. This monumental uprising, led by our national hero Cuffy, predated the American Revolution of 1774 and the Haitian Revolution of 1799, underscoring the indomitable will of

Africans to fight for their freedom.

The long and valiant history of the contributions by African ancestors to the making of modern Guyana can never be understated.

The struggles of the African people in Guyana, which began in the early 1600s and continue today, are a testament to their ongoing commitment to establishing a free, fair, just, and equitable Guyana. Emancipation Day holds profound significance for Guyanese of African descent. It is a day of reflection, remembrance, and reverence for the immense sacrifices our forebears made. As we commemorate this

momentous occasion, it is crucial to reflect upon the contribution made by African people in their continued rejection of all attempts to subjugate, denigrate, and humiliate them individually and as a people since their arrival. The 1763 uprising, which began at plantations Hollandia and Zeelandia, was the cornerstone of modern Guyana. However, as a nation, we have failed to properly honor the foundations of our nationhood by not erecting commemorative cornerstones at these locations to mark the commencement of the uprisings.

The Alliance for Change will seek to engage all willing

stakeholders to truly honour the forefathers of modern Guyana by erecting commemorative cornerstones at Zeelandia and Hollandia to mark the commencement of the 1763 uprising.

Furthermore, we urge that the history department of the University of Guyana be the beneficiary of a fully funded research fellowship dedicated to further academic research into the 1763 Uprising, and the repatriation and preservation of the historic records about the uprising, currently located overseas.

Let us draw strength and inspiration from our history, celebrate the rich cultural heritage, achievements, and contributions of Africans to Guyana and the world. The AFC urges all citizens to reflect upon the sacrifices made by our African ancestors in the making of a modern Guyana and enjoy a day of peaceful reflection on our history.

Happy Emancipation Day, Guyana. Let us remember, reflect, and continue the fight for true freedom.