14 minute read

Malaysian Borneo: Cultural Heritage of Indigenous

Malaysian Borneo Cultural Heritage of Indigenous Tribes

Will children of the forest be able to preserve their tribal culture?

Advertisement

Written and photographed by Cami Ismanova

One fine, rainy evening, I was walking down the street to visit the local Central Market in Kuala-Lumpur, Malaysia. I was excited to dive into the lively market life and get swirled into the storm of aromas. I knew for sure it was going to be a treat! I entered the market through a back gate and saw rows of fabrics, handmade soap, candles, local jewelry, traditional items of clothing, and souvenir shops. Relics of animism that belonged to the ancestors of the Iban people.

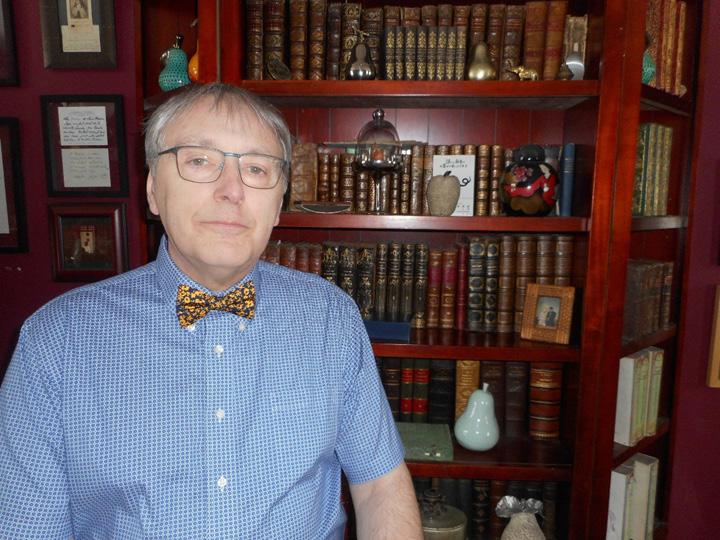

I found out that the Art House Gallery and Museum of Ethnic Arts focuses on the culture and art of the indigenous people of Southeast Asia. This mini museum is the one and only museum dedicated to tribal and ethnic art in the region. The owner, Leonard Yiu, has been collecting and dealing with items of art for 30 years. He offered me a tour around the museum and the gallery, patiently answering dozens of my questions.

I was walking from one shop to another when I stumbled into an art shop. I got curious, for I believe art is a major inspiration for someone who enjoys writing. I have no doubt I looked enchanted as I slowly absorbed every single painting I laid an eyes on. It was then that I saw the sign “Art House Gallery” up above the first floor. “It wouldn’t hurt to check it out,” I thought, and began my journey into the history of ethnic culture of Malaysian indigenous tribes. Every single time I stopped in front of some painting, tribal mask, or native clothing, he would share an interesting story about each of them. So, if you ever visit this place, you will surely get an amazing guide. As you can judge from its title, the Art House consists both of a gallery and a museum.

whatever you might like. The museum consists of several sections dedicated to the art and culture of the area’s different ethnic groups. In particular, the section on Borneo’s cultural heritage attracted me the most.

Borneo is a gigantic island shared by Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei. What makes Borneo so special? To name a few things, it has picturesque views, a biodiverse rainforest, and a rich culture. While I was listening to the stories that Leonardo kindly agreed to share, I saw so many authentic pieces of art from Borneo that it left me speechless.

Artwork carved out of wood and stone.

for they had hundreds of totems and worshipped several groups of beings, including a supreme god, holy spirits, ghost spirits, and the souls of the ancestors.

But nowadays, the majority of the Iban people are Christian. They were converted to Christianity after the mid-19th century arrival of British adventurer James Brooke. Only 13.6 percent of the Iban people still follow their original folk religion of animism, while the rest follow other religions like Islam, or do not have a religion at all. According to Leonard, even though some of the masks are extremely frightening, they were worn by “good guys” known as shamans who tried to heal sick children by practicing various tribal rituals. There is a strong belief that exorcism was a part of those practices.

How do the Iban people live now in the 21st century? Unfortunately, globalization and urbanization are not always welcomed by indigenous people. New construction, deforestation, and wildfires have not contributed to their wellbeing. It has been somewhat difficult for them to accept this modern era of technological advancement and mobility. Some of the Iban people have to move from place to place constantly because of the construction of new buildings in the areas they inhabit. They carry the roofs of their huts to build a new home every two to three months. This kind of life endangers the Iban’s tribal culture, and it is becoming increasingly difficult to preserve what is left.

Native hats, beaded necklaces, woven mats, bone plates, tun-tun sticks, Iban masks, armlets, medicine boxes, carving knives, and many more artifacts were on display. Native beaded hats and necklaces are rich in color and pattern. They reminded me of some Central Asian skullcaps. The woven mats are flamboyant and exquisite, depicting various scenes from the daily life of indigenous tribes. They look both simple and complicated at the same time. All those curved, zigzagged, and wavy lines intersecting and forming a scene certainly tells us a deep, yet easily explicable story.

One of those stories is related to the Iban tribe, a race of fearsome, indigenous warriors known for headhunting and piracy in the past. However, since Europeans came to their lands, the practice of headhunting gradually stopped, although a lot of traditions, tribal customs, and the Iban language are thriving. The Iban tribe mostly inhabits the Malaysian state of Sarawak, although they are found throughout the whole of Borneo. The reason why I remember the Iban tribal culture and art so well is due to the clear image of masks they wore. Iban shamans would wear these (to be honest, quite frightening) masks during tribal rituals. The ancestors of the Iban practiced animism,

Once fierce and tattooed warriors who dominated the forest, today they can hardly call their native lands home. It is easier said than done, but I believe that an adaptation to modern life in moderate amounts can save them and their culture from extinction.

I am incredibly happy to share their story and art with others. This world is a home for all of us and the rich, authentic cultures that we have helped to carry on for thousands of years.

Art House Gallery and Museum of Ethnic Arts

Level 3, The Annexe, Central Market, Jalan Hang Kasturi, 50050 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 10:30 a.m. – 7:00 p.m, Free entrance 012-388-6868

The Author Cami Ismanova is a student in Chonnam National University majoring at economics. She loves traveling around, reading clasics ,and listening to jazz. These days she is fond of art and architecture, in particular, art galleries and museums. Her favorite art gallery is “The National Gallery of Singapore.”

Written by Régis Olry

The Origins and Concept of Ghosts in Korea K orean gghost stories are firmly rooted in oral tradition and ancient literature. [1] In the Tales of the Extraordinary (Sui chŏn), a compilation of Korean Buddhist tales and popular fables initiated by Ch’oe Chi-wŏn (857–900) during the Unified Silla Period, we can read the following story: A poet lived through a one-night love affair with two young women near a grave. But both disappeared at dawn, and the poet understood they were the ghosts of the women who had been buried in this grave.

In a fifteenth century novel of Sŏng Hyŏn (1439–1504), a maid committed suicide in order to come back in the form of a ghost and meet up with the man she secretly married. Cho Su-sam (1762–1849), in a poem written in the 1810s, mentioned “the unappeased ghosts threatening the peace.” In 1913, the historian James Scarth Gale (1863–1937) made available an English compilation of Korean folk tales by scholars Bang Im (b. 1640) and Ryuk Yi (mid-15th century) (Fig. 1). [2]

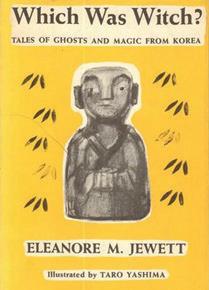

Forty years later, American writer Eleanore Myers Jewett (1890–1967) published another collection of Korean ghost stories wonderfully illustrated by Japanese artist Yashima Tarō (1908–1994) (Fig. 2). [3] Present-day literature is not outdone: Ghosts keep on lurking somewhere in many 21st century novels, such as Hwang Sok-yong’s 2008 Evening Star (Kaebapparagi pyôl) or Shin Kyung-sook’s 2011 Please Look After Mom (Ommarŭl putakhe), among many others.

The history of Korea over the centuries and the interactions with neighboring countries explain why some Korean ghost tales may obviously be derived from ancestral folklore, however, with some noteworthy differences – a nuance Shin Jee-young calls “hybridisation, not homogenisation.” [4] For example, the bronze bell of King Seongdeok is believed to have been successfully cast only after a monk had pushed a child into the molten metal. into the molten metal but threw herself into it to commit suicide. [5] In both tales, the victims became ghosts.

Korean Ghost Movies In Korea and all neighboring countries, ghosts are seen “as beings that co-exist with the world of the living.” [6] One can actually touch a ghost, talk with a ghost, eat with a ghost, and even fall in love with a ghost, as can be seen in Hwang In-ho’s 2011 Spellbound (Ossakhan Yeonae) and Oh In-chun’s 2014 Mourning Grave (Sonyeogoedam).

The very first Korean movie to portray a vengeful ghost is The Story of Jang-hwa and Hong-ryeon directed in 1924 by Park Jung-hyun. [7] Kim Jee-woon, among others, drew his inspiration from this story for his 2003 masterpiece A Tale of Two Sisters (Janghwa, Hongryeon).

Of course, Korean ghost movies have common features with other Asian ghost movies. The most evident is the iconic vengeful spirit called wonhon in Korean (Fig. 3), counterpart of the Japanese onryô: a female ghost in a white gown with long dishevelled black hair, [8] as can be seen in Ahn Sang-hoon’s 2006 Arang (Arang). Why dishevelled hair? Because they are known in Asian culture to express “vows of vengeance.” [9]

But they also have some specificities. Firstly, while ghost movies from other Southeast Asian countries lay a certain emphasis on technology (camera in Parkpoom Wongpoom and Banjong Pisanthanakun’s 2004 Shutter, videotape in Nakata Hideo’s 1998 Ringu, phone in Miike Takashi’s 2003 Chakushin-ari, internet in Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s 2001 Cairo), many Korean ghost movies are concerned with “adolescent sensibility,” what Choi Jinhee refers to as “A Cinema of Girlhood.” [10] The famous Whispering Corridors (Yeogo goedam) series is the best example. Secondly, shamanism remains very important in Korean culture; [11] it is therefore not surprising to see shamans involved in the fight against evil spirits, as in gripping Choi Do-hoon’s 2019 TV series Possessed (Bingui).

famous O sacrum convivium in Choi Ik-wan’s 2005 Voice (Moksori). Fourthly, the acting of the cast achieves a yet unequalled power and authenticity.

Is it still relevant to talk about ghosts in the 21st century? As pointed out by the Californian sociologist Avery F. Gordon: “Haunting is a constituent element of modern social life. It is neither premodern superstition nor individual psychosis; it is a generalizable social phenomenon of great import. To study social life one must confront the ghostly aspect of it.” [13]

Fig.1 Fig.2

Ghost Movies or Horror Movies? Should ghost movies be referred to as horror movies? Sometimes yes, but not always. Jeong Beom-sik’s 2018 Gonjiam: Haunted Asylum (Gonjiam) obviously aims to scare spectators (and it works!), which dovetails with the views of Michael Kleinod when he wrote that “the relationship between humans and spirits is less a question of belief than of fear.” [ 12] But Korean ghosts are much sadder and fuller of suffering than they are frightening and dangerous creatures: The best way to understand what a ghost feels is to watch Song Il-gon’s Spider Forest (Fig. 4), indisputably the most intelligent ghost movie of the 21st century.

The Author Régis Olry, M.D. (France), is professor of anatomy at the University of Quebec at Trois-Rivieres (Canada). In the early 1990s, he worked in Germany with Gunther von Hagens, the inventor of plastination and the BodyWorld exhibitions. He currently studies the concept of Asian ghosts in collaboration with his wife who is a painter (see www.gedupont.com).

Fig. 3. A typical wonhon (Korean Ghost Stories, Jeolseolui Gohyang, 2008). Fig. 4. Movie poster of Song Ilgon’s Spider Forest.

References

[1] Cho, D., & Bouchez, D. (2002). Histoire de la littérature coréenne des origines à 1919. Fayard, pp. 96, 201, 249. [2] Im, B., & Yi, R. (1913). Korean folk tales: Imps, ghosts, and fairies. [Trans. J. S. Gale]. E. P. Dutton. [3] Jewett, E. M. (1966). Which was witch? Tales of ghosts and magic from Korea. Illustrated by Taro Yashima. New York: The Viking Press. [4] Shin, Jee-young (2005). Globalization and New Korean Cinema. In: Shin Chi-yun and Julian Stringer (Eds.) New Korean Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University press, p. 57. [5] Goodman, Henry (1949). The selected writings of Lafcadio Hearn. New York: The Citadel Press, pp. 89-93. [6] Richards, A. (2010). Asian horror (p. 15). Kamera Books. [7] Peirse, A., & Martin, D. (2013). Introduction. In A. Peirse & D. Martin (Eds.), Korean horror cinema (p. 3). Edinburgh University Press. [8] Lee H. (2013). Family, death, and the wonhon in four films of the 1960s. In A. Peirse & D. Martin (Eds.), Korean horror cinema (pp. 25–34). Edinburgh University Press. [9] Olivelle, P. (1998). Hair and society: Social significance of hair in south Asian tradition. In A. Hiltebeitel & B. D. Miller (Eds.), Hair: Its power and meaning in Asian culture (pp. 11–49). State University of New York Press. [10] Choi, J. (2009). A cinema of girlhood: Sonyeo sensibility and the decorative impulse in the Korean horror cinema. In J. Choi & M. WadaMarciano (Eds.), Horror to the extreme: Changing boundaries in Asian cinema. (pp. 39–56). Hong Kong University Press. [11] Pettid, M. J. (2009). Shamans, ghosts, and hobgoblins amidst Korean folk customs. SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies, 6, 1–13. [12] Tappe O., Salverda T., Hollington A., Kloss S., & Schneider N. (2016). Global modernities and the (re-)emergence of hosts. Voices, 2, 3. (Global South Studies Center.) [13] Gordon Avery F. (2008) Ghostly matters. Haunting and the sociological imagination (p. 7). University of Minnesota Press.

Burying the Dead in Korea

Traveling along the expressway or the railway to Seoul, or anywhere in Korea, one is sure to see the hillsides dotted with pockets of grassy mounds – traditional burial sites. In his “The Korean Way” column in the Gwangju News, Prof. Shin Sang-soon (1922–2011) several times dealt with the subject of burying the dead in Korea. Here we compile three of Prof. Shin’s articles for a composite picture of the topic: “The Way of Burying the Dead” (February 2003), “Why Graves Are Moved from One Place to Another” (November 2004), and “Change of Mode of Burial” (September 2010). We would also like to note that his September 2010 article was Prof. Shin’s final contribution to his “The Korean Way” column before his passing months later. — Ed.

THE KOREAN FUNERAL I n a traditional Korean funeral ceremony, the body of the deceased will usually rest at home for at least three days after death, before being carried to the final resting place. Interment usually takes place on the 3rd, 5th, or 7th day after death depending on the situation. If any members of the bereaved family are far away from home and their presence at the funeral is considered necessary, the funeral rites are delayed, but customarily it is a three-day affair. A funeral manager, called hosang chaji (호상차지), is invited to take charge of the entire funeral ceremony. He is usually a friend of the deceased, who is supposed to be very familiar with the funeral process. A flowerdecked altar is prepared in the house, and a picture of the deceased draped in a black ribbon is placed in the center. To one side in front of the altar, the children of the deceased, now called sangje (상제, mourners), stand in the order of age, with the eldest being the closest to the altar to receive condolence callers.

When a death occurs in a family, of either a parent or a grandparent, the news is immediately dispatched to all family and relatives, who then come to the house to prepare a shroud for the deceased and funeral clothes for close relatives. If the house is an independent and separate building with a fairly large courtyard, a large tent may be set up to receive guests. Room space is not readily available for visitors because it is occupied by those preparing the funeral clothes and the food for the funeral, and by relatives from far and near.

The shrouding usually takes place on the second day, the ritual in which a hemp or silk shroud is placed around the body of the deceased from head to foot. Afterwards, the shroud is secured around the corpse in seven places with hemp rope and placed in the coffin. Direct and distant kin wear hemp funeral clothes.

The funeral procession to the gravesite starts with the removal of the coffin to the funeral bier, called sangyeo (상여). It starts on the third day after death if it is a three-day funeral. The bier is carried by 8, 12, or 16 male pallbearers, normally villagers or friends. Usually the male family mourners follow the bier to the burial site. If the deceased was a man of renown and virtue, dozens of funeral banners with laudatory phrases written on them follow the bier, donated by those attending the funeral. The gravesite is selected by a jigwan (지관, geomancer, or literally “earth diviner”) as a blessed site after studying the lay of the land and the surrounding area. At the burial site, an interment ritual is held before the coffin is lowered into the ground.