17 minute read

ARTS

A Place at the Diversity Table

Advertisement

Anti-Jewish bias is spreading in arts and culture | By Hilary Danailova

There is little doubt that antisemitism in America has intensified recently. In the world of arts and culture, it may be more subtle than a scrawled swastika or a torched synagogue, but anti-Jewish bias in that realm is nonetheless a growing phenomenon.

This bias plays out in multiple ways, according to those looking at culture through a Jewish lens. One of the most recognizable is the marginalization—even demonization—of Israel, with Israeli narratives and artists who perform in Israel targeted by cultural boycotts. At the same time, debate persists among academics and media industry professionals about the degree to which Jews and Jewish stories are excluded from current diversity conversations.

Controversies around Israel “happen every year,” observed Shayna Weiss, the associate director of Brandeis University’s Schusterman Center for Israel Studies and a scholar of Jews in popular culture. “I think we see it more now because it’s easier to find these things online.”

A prime example is the anti-Israel Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement (BDS), in whose name pro-Palestinian activists have bullied entertainers who perform in Israel for years. Yet today, we watch the backand-forth in real time on social media platforms that weren’t as popular, or weren’t around, back when the movement first emerged in the early 2000s. Announcements of a November concert in Israel by will.i.am of the Black Eyed Peas were met with instant boycott calls on Facebook and Twitter. And last July, singer/songwriter Billie Eilish’s Instagram account was targeted by antisemitic trolls after she promoted the launch in Israel of her album Happier Than Ever.

Social media has amplified other recent dustups, including popular Irish author Sally Rooney’s refusal to allow an Israeli publisher to translate her latest novel, Beautiful World, Where Are You, into Hebrew; comedian Sarah Silverman calling out “Jewface,” a neologism to describe non-Jewish actors playing Jewish roles, in a September podcast; and in spring 2021, the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators issuing, and then apologizing for, a statement that condemned antisemitism.

The entertainment community for the most part is very liberal. And on the left, unfortunately, if you support Israel, you’re being pushed out of those spaces,” said Ari Ingel, director of Creative Community for Peace, a nonprofit arts industry group that combats antisemitism, specifically the cultural boycott of Israel.

Ingel is among those who bemoan a progressive tendency to critique Israel’s complex, multicultural society in terms of America’s charged racial paradigm—“white oppressors, brown victims,” he said, with Israeli Jews cast as the oppressors. “It has been lumped into: If you’re a Zionist, that

BDS Targets The 2021 TLVFest (above) was the focus of anti-Israel activists; singer/songwriter Billie Eilish (opposite page, right) was attacked on social media after she announced the release in Israel of her new album; and there were boycott calls when Black Eyed Peas co-founder will.i.am, here with former bandmember Fergie in an earlier concert in Israel, announced a 2021 show in the country.

means you’re a colonizer. When you have Israel labeled a genocidal state and 90 percent of Jews in America support Israel, then all of a sudden Jews support genocide.” At a time when racial issues dominate American discourse, this perception has led to the increase in anti-Jewish sentiment.

“We’ve seen these views emanate online from influencers in the entertainment community,” Ingel added. In 2020, rapper Ice Cube tweeted antisemitic images of a mural with large-nosed men playing Monopoly on the backs of Black people. The same year, Nick Cannon, host of the reality competition show The Masked Singer, shared classic antisemitic conspiracy theories on his podcast, asking why “we give so much power to the ‘theys,’ and ‘theys’ turn into Illuminati, the Zionists, the Rothschilds.” In response, ViacomCBS canceled Cannon’s improv comedy television show, Wild N’ Out. The entertainer apologized and engaged in dialogue with the Jewish community. His show is now back on the air.

Ingel said his organization provides “balance” to what is often a strongly anti-Jewish discourse, supporting entertainers and sports figures who work in Israel. Last October, the group published an open letter protesting a boycott of TLVFest, the annual Tel Aviv International LGBTQ+ Film Festival. The 200 entertainment industry signatories included actors Neil Patrick Harris, Billy Porter and Helen Mirren (who, for her upcoming film role as Israeli prime minister Golda Meir, has been showered with antisemitic hate online). And nearly 50,000 artists have signed the group’s online petition against the cultural boycott of Israel since 2012, when Creative Community for Peace was founded by David Renzer, then CEO of Universal Music Publishing Group, and Steve Schnur, who heads the music division of Electronic Arts, the world’s largest video game company.

Such high-profile signatories “demonstrate to the public that there’s still broad-based support for understanding and dialogue,” Ingel noted. “Where politics can be so divisive, arts, sports and music can really bring people together.”

Some observers like Weiss, the Brandeis scholar, suggest that BDS and its offshoots may be louder than they are successful. “Israeli culture has unprecedented amounts of money and attention,” said Weiss, citing Israeli shows that have become international hits—Tehran, Fauda and Shtisel among them—as well as the many Israeli series optioned for American remakes. “Money talks, and there’s a lot of money to be made working with Israeli films and television.

“It’s easy to freak out about Sally Rooney, but that is one book versus thousands that are translated into Hebrew every year,” Weiss continued. “The internet loves outrage, but these things have to be taken in context.”

In a different sector of the arts world, anti-Israel sentiment sparked internet outrage last June when the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, one of the largest international children’s literature organizations, apologized to its Palestinian and Muslim members after they objected to a post declaring that Jews should have the “right to life, safety, and freedom from scapegoating and fear.” The original

statement was posted on Facebook in response to a surge in antisemitic violence in the United States; it asked readers to join “in speaking out against all forms of hate, including antisemitism,” and made no mention of Israel or its war with Hamas that same spring. Even so, pro-Palestinian members of the society complained that the “painful” lack of a parallel denunciation of Islamophobia amounted to taking sides in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—an argument that caught the attention of the children’s literature community on Twitter and Facebook.

Several weeks later, Lin Oliver, the society’s executive director, apologized on Facebook to everyone in the “Palestinian community who felt unrepresented, silenced, or marginalized.” (The society declined repeated requests for comment.) The controversy led to the resignation of the society’s chief equity and inclusion officer, April Powers, who is Black and Jewish. It also prompted many Jewish writers to voice discontent over their exclusion from industry diversity conversations and heightened their concerns about being targeted on social media.

Helen Estrin, a past president of the Association of Jewish Libraries, said this marginalization occurs because Jews, who are historically well represented in cultural industries, “are seen as having enough privilege and power that they don’t need support. It is unconscious— people aren’t walking around, for the most part, with swastikas—but I absolutely think it’s antisemitism.”

What Jewish authors notice in particular, Estrin said, is that they are excluded from minority grants and diversity programs, such as the ones run by the society, and that they are frequently harassed online. Authors also have complained that mainstream publishers reject Jewish- and Israel-themed books, a topic often discussed in the Jewish Kidlit Mavens Facebook group that Estrin administers with Susan Kusel.

“Frankly, we feel gaslit,” said Kusel, a member of the society whose most recent book is The Passover Guest. Jews are not being included

Continued on page 40

USING ANNE FRANK TO DISCUSS RACE

Could Anne Frank be the key

to educating Gen Z Americans about antisemitism—even if they’ve never met a Jew?

The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam is betting yes. In September, it launched a partner institution in the United States, the Anne Frank Center at the University of South Carolina. Although the new center, set in the heart of the American South, will likely have a largely Christian audience with little experience with Jewish culture, Doyle Stevick, the center’s executive director, thinks the Holocaust’s most famous diarist can educate modern youths about racism and discrimination through parallels to contemporary issues.

In many schools’ Holocaust curricula, Anne Frank is often “the only child you get to know in detail, and in her own voice,” at the University of Heidelberg. Hitler’s tirade against Wright, the exhibit explains, found echoes in the racist words that mass murderer Dylann Roof was reported to have said, about Black people “taking over the world,” as he attacked Black congregants

Stevick explained, noting the popularity of the diary on school reading lists. An associate professor at the university’s College of Education, Stevick, who is not Jewish, had been working with the Anne Frank House since 2013 and, with the university, has brought exhibits about Anne Frank to South Carolina schools. “Anne’s words help us appreciate how young people have the potential to bring out the best in one another,” he said.

To that end, student volunteers lead nearly every visitor through the center’s exhibition “Anne Frank: A History for Today.” Four rooms with photos, videos and original artifacts are divided between Holocaust history and its relevance to the American racial landscape—incorporating stories like that of economist Milton S.J. Wright, the only Black American known to have met Hitler. The two met in 1932 in Germany, when Wright was pursuing his doctorate at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston in 2015.

Like Anne and her fellow Jews, those worshipers were targeted primarily for their ethnicity, not their religion. Stevick said audiences are surprised to learn that that Nazis considered “Jewish” a racial rather than a religious category. “We use one example to address another,” he explained. “It’s all part of a common conversation.”

Her Voice The University of South Carolina’s new Anne Frank Center (inset); a view of the exhibit inside

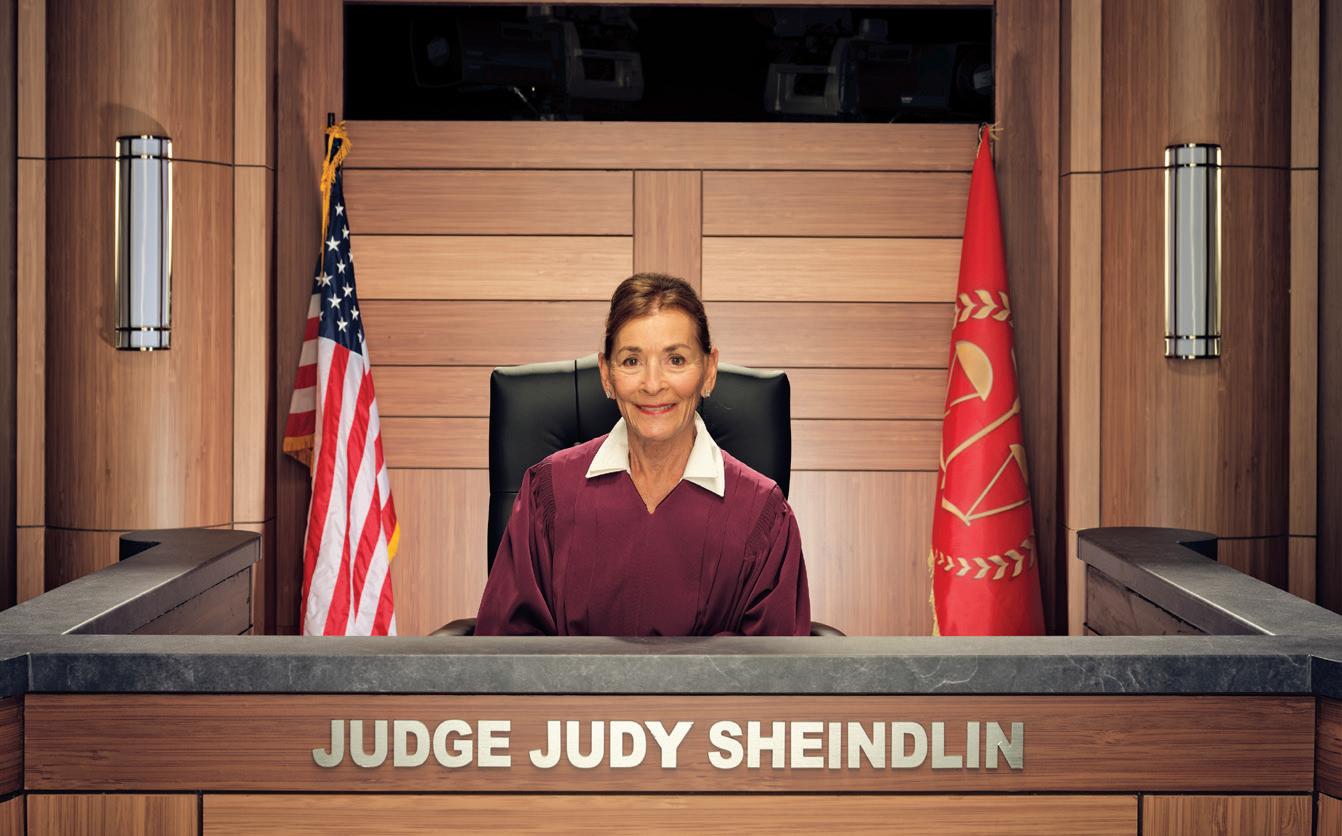

JUDY SHEINDLIN: FROM ‘JUDGE JUDY’ TO ‘JUDY JUSTICE’

By Curt Schleier

Judy Sheindlin rode her reputation as a

no-nonsense New York City prosecutor and judge to the top of the Nielsen ratings. For the last 25 years, she starred in Judge Judy, the CBS courtroom series that featured the jurist arbitrating real-life cases in what was often the highest-rated program on daytime television. She was awarded three Daytime Emmys and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and became among the highest-paid hosts on daytime television, earning $47 million per year.

After tensions with CBS over ownership of the show’s reruns, she renamed the program and moved it to IMDb TV, the free streaming arm of Amazon. Judy Justice debuted in November and features the same type of small-claims cases that made Judge Judy so popular, from landlord-tenant conflicts to sales disputes.

Sheindlin, 70, was born Judith Susan Blum in Brooklyn, N.Y., and received her graduate degree from New York Law School. Before taking her brassy personality to television, she was a prosecutor in family court and was later appointed by legendary Mayor Ed Koch as a judge in criminal court and a supervising judge in family court.

I started our interview by reminding Sheindlin about a comment she’d made to the Hollywood Reporter last May, that she was not ready to retire or to learn mah jongg. I told her if she changed her mind, my wife had a mah jongg opening on Thursdays. She laughed and we were off to the races. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

What was your Jewish life like growing up in Brooklyn?

My family was what I call community observant, which means that we went to temple on the High Holy Days. We did not keep a traditional kosher home, but our extended family got together on holidays. My grandmother cooked. We all lived at 226 Parkside Avenue, on two different sides of the same building.

My grandfather would spend Yom Kippur in temple. Our tradition was that my family would go to temple at the end of the day and walk home with him. My grandparents lived on the seventh floor, or maybe the ninth. The building had an elevator but my grandfather, who was in his 60s—the equivalent of being in your 90s today—would walk the stairs.

When I asked him why, he said it was to atone for his sins. That translated to me as, “If I don’t do anything bad all year, I could always take the elevator.”

How did your upbringing help form the person you are today?

My father and mother were very moral people, and the message I got from them was that you try to do the right thing all the time. That doesn’t mean you’ll have a perfect outcome all the time. But you can be pretty damn sure that if you do the wrong thing— take someone’s bike, scratch someone’s car— and not take responsibility, it may not come back at you that day, but eventually karma has a full circle.

I don’t think that’s particularly Jewish. I think this country is made of moral people who wouldn’t consider taking someone else’s property.

How do you account for Judge Judy’s tremendous popularity?

I’m a good storyteller. Also, the viewing audience has to love you or watch you because they hate what you do. I prefer that you like me, but as long as you watch, I don’t care. I think the vast majority of people in this country believe that rules are being blurred without consequences. For an hour a day, you see the rule of order, something people find a little comforting, a little nostalgic. Sometimes I’m not quite PC, but I’m always truthful. And if you don’t like it, change the channel.

One of my favorites cases on Judge Judy was when you ruled on the ownership of a dog. Your process was almost Solomonic. How did you come to your decision?

One man said his dog had been stolen from his yard. The woman said she’d bought the dog. As a dog owner, I know that when I come home after being away—although she loves the people who take care of her—my dog runs to me and doesn’t leave my side. So I had the clerk bring the dog into the courtroom, and the dog ran to the man. Clearly the dog favored him despite the fact that he’d been living with the woman for six months. I was just using common sense.

Curt Schleier, a freelance writer, teaches business writing to corporate executives.

in the diversity conversations, she believes, because their non-Jewish colleagues feel that “Jews do not need the boost. At the same time, we’re being persecuted as a minority.”

Even before her debut young adult novel, Once More with Chutzpah, was published, writer Haley Neil confronted a torrent of online hatred for her story of a girl grappling with Jewish identity on a trip through Israel, which she based on her experiences growing up Jewish in an interfaith home. “This book supports genocide” is typical of many antisemitic comments Neil found about her book on Goodreads, a major online book platform that features early reviews of upcoming titles. “I worried my book would never reach an audience, because people who haven’t read it made false accusations about its contents,” Neil said of the novel, due out this February.

“The increasing focus on diversity in the kidlit space is wonderful,” said Tzivia MacLeod, a Canadian-Israeli author who has won awards from PJ Library (which published two of her titles) and is a regional adviser for the Israeli chapter of the society. “But it has created questions and resentment for authors.” Jews, she said, “need to start demanding a place at the [diversity] table for our own unique and underrepresented background, whether from North Africa, the Middle East or Europe.”

Tensions around presence and visibility complicate issues like “Jewface,” according to Shaina Hammerman, associate director at Stanford University’s Taube Center for Jewish Studies. With its reference to the history of white entertainers putting on blackface, Jewface refers not only to non-Jews cast as Jewish characters, but also to particular mannerisms or references that are uncomfortably close to ethnic caricature—roles “where Jewishness is front and center,” the Jewish comedian Sarah Silverman said, addressing the topic in the much-debated September episode of The Sarah Silverman Podcast.

The Jewface complaint also highlights how frequently non-Jews are cast in high-profile Jewish roles—especially those involving conventionally attractive or refined characters, like Midge Maisel and her parents in the Amazon series The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, or historically important figures, like Helen Mirren as the titular character in an upcoming biopic of Golda Meir

But Are They Jewish? On her podcast,

Sarah Silverman (above) discussed issues around ‘Jewface,’ when non-Jews are cast as Jewish characters, such as Rachel Brosnahan as Midge Maisel and Tony Shalhoub and Marin Hinkle as Midge’s parents in ‘The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel’ (opposite page).

or Felicity Jones as Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in the film On the Basis of Sex.

In his recent book Jews Don’t Count: How Identity Politics Failed One Particular Identity, which discusses anti-Jewish bias in media and culture, British television personality David Baddiel calls the issues around Jewface a “passive” antisemitism. “Look for the absence: the absence, in this case, of concern” and outrage in the public discourse, he writes, when non-Jewish actors play Jewish characters.

Indeed, on her podcast, Silverman insisted she was not calling for change so much as pointing out an uncomfortable double standard: Authentic representation is now de rigueur for virtually every minority group but Jews. Unlike other minority groups, however, Jewish actors have found work playing a range of characters.

“It’s been really important to make sure that a Native American plays a Native American character, or that an Asian play an Asian, because otherwise, historically, they weren’t getting jobs,” Hammerman, of the Taube Center for Jewish Studies, noted. “But Jewish actors are cast all the time to play non-Jews.”

In Hammerman’s view, how a Jewish character is written—as “a rich and interesting human”—is more critical than who plays the role. The larger question, she added, is how to ensure that Jews and antisemitism remain part of American conversations around racism and ethnic discrimination.

For many in the arts world, “it’s hard to hold in your mind at the same time that many Jews in this country have power and access— and also, that antisemitism is real,” Hammerman reflected. “The more we can address this complexity, the better off everybody is.”

Hilary Danailova writes about travel, culture, politics and lifestyle for numerous publications.

LOOKING FOR MORE ARTS COVERAGE?

Go to hadassahmagazine.org/arts and read about the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene’s newest productions: The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, a new opera about an aristocratic Jewish-Italian family on the eve of World War II, and Harmony: A New Musical, created by Barry Manilow, based on the real-life story of a German harmony ensemble whose fame was cut short by Nazi racial laws.

A C H A I F L I C K S E X C L U S I V E